Abstract

Objective(s):

To systematically review literature on brief screening tools used to detect and differentiate between normal cognition and neurocognitive impairment and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HANDs) in adult populations of persons with HIV.

Design:

A formal systematic review.

Methods:

We searched six electronic databases in 2011 and contacted experts to identify relevant studies published through May 2012. We selected empirical studies that focused on evaluating brief screening tools (<20 min) for neurocognitive impairment in persons with HIV. Two reviewers independently reviewed retrieved literature for potential relevance and methodological quality. Meta-analyses were completed on screening tools that had sufficient data.

Results:

Fifty-one studies met inclusion criteria; we focused on 31 studies that compared brief screening tools with reference tests. Within these 31 studies, 39 tools were evaluated and 67% used a comprehensive neuropsychological battery as a reference. The majority of these studies evaluated HIV-associated dementia (HAD). Meta-analyses demonstrated that the HIV Dementia Scale (HDS) has poor pooled sensitivity (0.48) and the International HIV Dementia Scale (IHDS) has moderate pooled sensitivity (0.62) in detecting a range of cognitive impairment. Five newer screening tools had relatively good sensitivities (>0.70); however, none of the tools differentiated HAND conditions well enough to suggest broader use. There were significant methodological shortcomings noted in most studies.

Conclusion:

HDS and IHDS perform well to screen for HAD but poorly for milder HAND conditions. Further investigation, with improved methodology, is required to understand the utility of newer screening tools for HAND; further tools may need to be developed for milder HAND conditions.

Keywords: diagnosis, HIV/AIDS, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder, neurocognitive impairment, screening tool

Introduction

Since the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), the incidence of severe forms of HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment has declined significantly, whereas the prevalence of the milder forms has increased [1,2]. The nomenclature originally developed by the American Academy of Neurology Task Force on AIDS in 1991 was recently updated in 2007 in response to the change in presentation and research available on the natural history of HIV-associated neurocognitive complications [3]. There are now three different HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) conditions. In order of increasing severity and related impact on everyday functioning, these are first, asymptomatic neurocognitive disorder (ANI) with a prevalence of 30–35% and characterized by at least mild neurocognitive impairment in two domains (at least 1.0 SD below the mean for age-education-appropriate norms) but with no evidence of difficulty with day-to-day functioning; second, mild neurocognitive disorder (MND) with a prevalence of 20–25% and characterized by at least mild neurocognitive impairment in two domains (at least 1.0 SD below the mean for age–education appropriate norms) and with mild interference with day-to-day functioning; and third, HIV-associated dementia (HAD) with a prevalence of 2–3% with generally moderate to severe impairments in neurocognitive functioning in multiple domains (2 SD or greater than demographically corrected means) and marked difficulties with everyday functioning [3]. Overall, the prevalence of HAND based on the new criteria is approximately 50–60% [1,4].

In the early years of the HIV epidemic, 20–30% of patients presented with severe cognitive impairment that was later classified as HIV-1-associated dementia complex [5]. The HIV Dementia Scale (HDS) was developed to screen for HAD [6] and later the International HDS (IHDS) [7] was developed for use in global settings. These instruments have had varying degrees of success in screening of those with the milder forms of HAND (i.e. ANI and MND). The clinical significance of identifying the milder forms of HAND is important, as they can have a significant impact on the lives of people living with HIV. They have been shown to interfere with medication adherence [8,9], workplace performance [10], driving [11] and ability to carry out tasks independently [12,13]. The consequences of these effects have been seen in decreased health-related quality of life [14] and increased mortality rates [2,15] in people with HAND.

To better assist in prevention, treatment and management of HAND, it is important that screening tools be developed and evaluated. Before widespread use for clinical treatment decision-making, these tools need to be shown to have adequate sensitivity and specificity with HAND; they need to be brief enough to be used in the clinic or health centre, and able to be administered by a trained individual with minimal equipment.

To determine which screening tools for HAND meet these criteria, we have undertaken the first systematic review of the literature with respect to the screening tools for HAND. Our objective is to systematically review the literature on brief screening tools that can detect neurocognitive impairment and are able to differentiate among the various forms of HAND in the adolescent and adult population of persons living with HIV and AIDS.

Materials and methods

We conducted literature searches in MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, LILACS and CINAHL in May 2011 for published, full-length research articles. An experienced librarian in systematic review methods assisted us in developing a search strategy (included in Appendix A). We did not apply date or language restrictions in the search strategy because we did not want to limit the investigation to tools administered only in English. We also contacted key experts in the field for recommendations and received articles for potential inclusion until the start of May 2012.

Inclusion criteria

Participants

Only studies reporting on participants who were adolescent or adult age were included (generally age >16 years). To be included in the review, individual studies needed to include participants who were HIV-positive and with some form of documented HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment, or be characterized/diagnosed with having any HAND [i.e. ANI, MND, minor cognitive motor disorder (MCMD), or HAD] [3,5]. The studies evaluated neurocognitive impairment in different ways, and this is a limitation of the current state of the literature.

Screening tools

We considered studies that focused on screening for ‘neurocognitive’ or ‘neuropsychological’ impairments or HAND [3,5]. The ways in which studies addressed screening tools included evaluating the utility of a specific screening tool, comparing different screening tools and validating screening tools. The focus of the review was then restricted to include only those articles that evaluated the utility of screening tool(s) against a separate reference or criterion. We defined screening tools to include pen and paper tests, algorithms and computerized tests and excluded biological tests (i.e. studies looking at biomarkers). In addition, we focused on ‘brief’ screening tools, and we defined this as those that took approximately 20 min or less to perform. This was done because the focus was screening tests that might be potentially useful in a clinic or healthcare setting to detect HAND.

Study designs

All studies needed to report findings from empirical research. We included primary studies and considered both cross-sectional and longitudinal investigations. We excluded primary studies that used qualitative methods or case study methods. We also considered systematic review articles.

Search and data extraction

Two reviewers independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the citations from the search according to the selection criteria. For the citations that met the criteria, data from full texts were extracted by one reviewer and checked independently for accuracy by a second reviewer. We contacted study authors to obtain any information that was missing. Any disagreements between reviewers on data extracted were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer.

Methodological quality

Two reviewers independently appraised the quality of the selected articles from the search using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) tool [16]. This 14-item tool was specifically designed to assess the quality of primary studies addressing diagnostic accuracy. Disagreements between the reviewers on the different QUADAS items were resolved by consensus.

Results

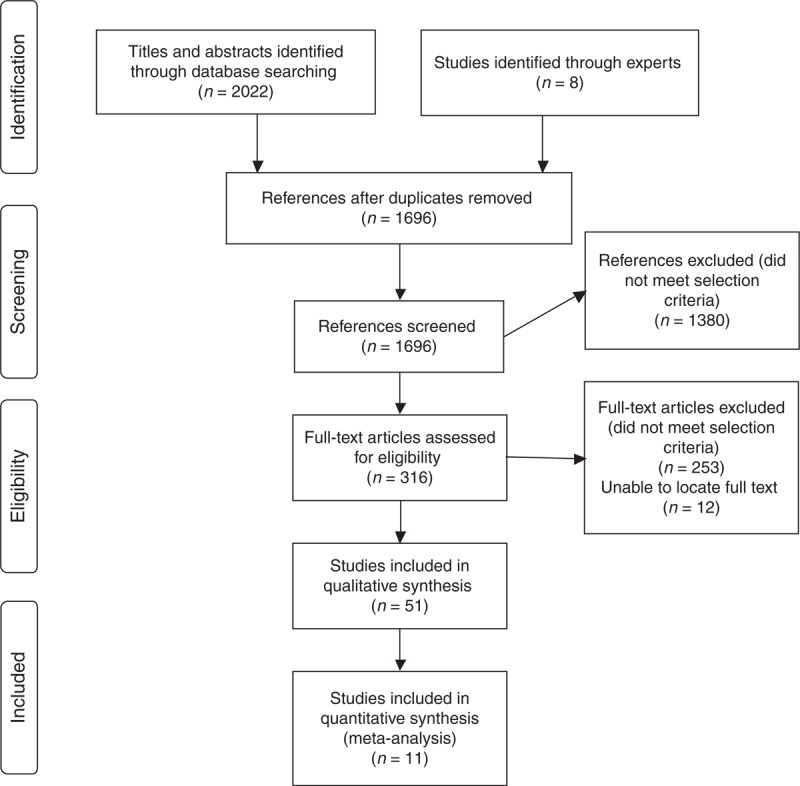

There were 2030 citations in the database searches and 334 of these were duplicates between databases. The review of titles and abstracts resulted in the identification of 316 articles for full assessment, with 1380 articles being excluded because they did not meet our inclusion criteria. We completed a full appraisal of 304 articles (we were unable to locate 12 full articles despite contacting the authors), and at this stage found that 253 of the 304 did not meet inclusion criteria resulting in 51 studies for inclusion. Articles that did not meet inclusion criteria were for the following reasons: six did not focus on people living with HIV; 185 did not evaluate screening tools; 28 did not include screening tools that are brief; eight did not report on empirical studies; and 26 articles did not include participants with HAND or impairment. [See Fig. 1 for Search strategy].

Fig. 1.

Search strategy.

Of the 51 studies that met criteria [6,7,17–65], we identified two main categories into which these studies could be divided: first, studies that evaluated screening tools by comparing them with a reference standard or criterion (n = 31 of 51 or 61% of studies evaluated) [6,7,17–44,64], and second, studies that evaluated screening tools by other methods (n = 20 of 51 or 39% of studies) [45–63,65]. For the purposes of the current article, we decided to focus our systematic review analyses on the first category of studies (n = 31), [see Table 1 for Characteristics of studies on brief screening tools for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders] as this is the most accepted method of evaluating a diagnostic tool (Results from the second category of studies can be found in Appendix B).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies on brief screening tools for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.

| Author; Location | Design | Recruitment method | Participants (mean age; mean years education; percentage male) | Tools examined |

| Becker et al. [17]; USA | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 51 (HIV+); 51 (HIV−); Education: 15 (HIV+); 15 (HIV−) Male: 96% (HIV+); 78% (HIV−) | The Computer Assessment of Mild Cognitive Impairment (CAMCI) |

| Bottiggi et al. [18]; Kentucky, USA | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 39; Education: 14; Male: 87% | HIV Dementia Scale |

| Carey et al. [19]; San Diego, USA | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 41; Education: 14; Male: 84% | Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised and Grooved Pegboard Test nondominant hand (PND) pair; Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised and WAIS-III Digit Symbol (DS) subtest pair; HIV Dementia Scale |

| Cysique et al. [20]; Sydney, Australia | Cross-sectional | Random sampling | Age: 47 (Advanced HIV); 48 (ADC); 49 (HIV−); Education: 14 (Advanced HIV); 14 (ADC); 15 (HIV−); Male: 98% (Advanced HIV); 100% (ADC); 100% (HIV−) | CogState |

| Cysique et al. [21]; Sydney, Australia | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 49 (HIV+); 47 (HIV−); Education: 14 (HIV+); 15 (HIV−); Male: 100% (HIV+); 100% (HIV−) | Screening Algorithm |

| Ellis et al. [22]; 15 sites, USA | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 44; Education: 14; Male: 86% | The NeuroScreen – Brief Neurocognitive Screen (BNCS) and Brief Peripheral Neuropathy Screen (BPNS) |

| Fogel [23]; USA | Cross-sectional | NR | Age: NR; Education: NR; Male: 92% | Brief Cognitive Screen (BCS) – memory subtest, verbal fluency items and conflicting stimulus test of the High Sensitivity Cognitive Screen (HSCS) |

| Ganasen et al. [24]; Western Cape, South Africa | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 34; Education: 10; Male: 26% | HIV Dementia Scale |

| Garvey et al. [25]; London, UK | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 48; Education: NR; Male: 84% | Prospective and Retrospective Memory Questionnaire (PRMQ) |

| Gonzalez et al. [26]; USA | Cross-sectional | Not reported | Age: 40; Education: 14; Male: 100% | California Computerized Assessment Package (CalCAP), mini-version |

| Jones et al. [27]; Baltimore, USA | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: NR; Education: 13; Male: 79% | Mental Alternation Test |

| Joska et al. [28]; Cape Town, South Africa | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 30 (HIV+); 25 (HIV−); Education: 10 (HIV+); 11 (HIV−); Male: 21% (HIV+); 38% (HIV−) | International HIV Dementia Scale |

| Knippels et al. [29]; the Netherlands and Flanders, Belgium | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 39; Education: NR; Male: 100% | Medical Outcomes Study HIV (MOS-HIV), four-item version in Dutch |

| Kwasa et al. [30]; Kisumu, Kenya | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 39; Education: NR; Male: 57% | HIV Dementia Diagnostic Tool |

| Lyon et al. [31]; Washington, DC; USA | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 17 (Dementia); 17 (No dementia); Education: NR; Male: 83% (Dementia); 45% (No dementia) | HIV Dementia Scale; Mini Mental State Examination |

| Maruff et al. [32]; Melbourne, Australia | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 46 (ADC); 47 (controls, AIDS but no ADC or MND); Education: 13 (ADC); 12 (controls, AIDS but no ADC or MND); Male: 89% (ADC); 91% (controls, AIDS but no ADC or MND) | CogState (brief battery) |

| Minor et al. [33]; USA | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 38; Education: 12; Male: 52% | Coin Rotation Test |

| Morgan et al. [34]; San Diego, USA | Cross-sectional | Random sampling | Age: 40 (HIV+); 37 (HIV−); Education: 13 (HIV+); 14 (HIV−); Male: 83% (HIV+); 68% (HIV−) | HIV Dementia Scale |

| Muniyandi et al. [64]; Thanjavur, India | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: NR; Education: NR; Male: 61% | Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE); Bender Gestalt Test (BGT); Wechsler Memory Scale; International HIV Dementia Scale (IHDS) |

| Overton et al. [35]; St. Louis, USA | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 40 (median); Education: NR; Male: 72% | CogState |

| Parsons et al. [36]; USA | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 24; Education: 13; Male: 66% | Motor battery (timed gait, grooved pegboard, finger-tapping) |

| Power et al. [6]; Baltimore, USA | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 42 (HIV−); 37 (Asymptomatic HIV+); 36 (nondemented AIDS); 39 (mildly demented AIDS); 39 (severely demented AIDS); Education: 15 (HIV−); 14 (Asymptomatic HIV+); 14 (Non-demented AIDS); 14 (mildly demented AIDS); 11 (severely demented AIDS); Male: 89% | HIV Dementia Scale; Mini Mental State Examination; Grooved Pegboard |

| Revicki et al. [37]; Baltimore-Washington, USA | Longitudinal | Convenience sampling | Age: 37; Education: NR; Male: 66% | 4-item Cognitive Function Scale (CF4) from HIV Health Survey and Complete 6-item Cognitive Function Scale (CF6) from Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) |

| Richardson et al. [38]; Boston Area, USA | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 41; Education: 12; Male: 65% | HIV Dementia Scale |

| Robertson et al. [39]; ACTG sites all over the world NYC, Chapel Hill and 42 sites around the world | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 38 (AIDS); 39 (SX); 35 (ASX); 35 (HIV−); Education: 14 (AIDS); 15 (SX); 15 (ASX); 16 (HIV−); Male: 87% (AIDS); 96% (SX); 91% (ASX); 56% (HIV−) | Timed Gait Test |

| Sacktor et al. [7]; Baltimore, USA and Uganda | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: US HIV+: 43 (no impairment); 44 (subclinical impairment); 47 (mild dementia); 44 (moderate dementia); 49 (severe dementia); Uganda: 37 (HIV+); 31 (HIV−); Education: US HIV+: 14 (no impairment); 13 (subclinical impairment); 13 (mild dementia); 12 (moderate dementia); 13 (severe dementia); Uganda: 9 (HIV+); 10 (HIV−); Male: NR | International HIV Dementia Scale |

| Simioni et al. [40]; Geneva, Switzerland | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: NR; Education: NR; Male: 72% | HIV Dementia Scale |

| Singh et al. [41]; Durban, South Africa | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 34 (median); Education: NR; Male: 40% | International HIV Dementia Scale |

| Smith et al. [42]; USA | Cross-sectional | Not reported | Age: 41 (NP normal); 41 (NP abnormal); Education: 14 (NP normal); 13 (NP abnormal); Male: NR | HIV Dementia Scale |

| Von Giesen et al. [43]; Dusseldorf, Germany | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 45 (mildly demented); 41 (not demented); Education: NR; Male: 100% (mildly demented); 100% (not demented) | HIV Dementia Scale |

| Wojna et al. [44]; Puerto Rico, USA | Cross-sectional | Convenience sampling | Age: 36 (HIV+); 34 (HIV−); Education: 12 (HIV+); 13 (HIV−); Male: 0% | HIV Dementia Scale, Spanish |

ADC, AIDS Dementia Complex; ASX, asymptomatic; MND, mild neurocognitive disorder; NR, not reported; SX, symptomatic.

Study characteristics (N = 31 studies)

Thirty-one studies are the focus of this subsequent analysis. Thirty of the 31 used a cross-sectional design [6,7,17–36,38–44,64] and one used a longitudinal design [37]. Eighteen of these studies (60% of all studies examined) were conducted in the USA [6,7,17–19,22,23,26,27,31,33–38,42,44]; three in Australia [20,21,32]; three in South Africa [24,28,41]; one each in the UK [25]; Germany [43]; Belgium and the Netherlands [29]; Switzerland [40]; Uganda [7]; Kenya [30]; India [64]; and one at sites across the world [39]. The participants in all of the studies combined totalled a sample of 5837 participants, and the individual study samples ranged from 20 [41] to 1549 [39] participants. Twenty-five studies used convenience sampling [6,7,17–19,22,24,25,27–33,35–41,43,44,64], and two used random sampling [20,34].

Neurocognitive screening tool evaluations

Types of screening tools evaluated

Within these 31 studies, 39 screening tool evaluations were conducted with 21 unique screening tools. Eleven studies evaluated the HDS (35%) [6,18,19,24,31,34,38,40,42–44]; four the IHDS (13%) [7,28,41,64]; three the CogState Computerized Battery (10%) [20,32,35]; three the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (10%) [6,31,64]; and other tools were evaluated in the remaining 16 studies [6,17,19,21–23,25–27,29,30,33,36,37,39,64]. Twenty-one (68%) [6,7,17–23,26,27,30,32,33,35–39,41,42] studies reported evaluating screening tools in English and eight (26% of studies overall) [7,24,28–30,41,43,44] in another language.

Presence and severity of neurocognitive impairment assessed

Of the 31 studies, 11 (35%) focused on detecting HAD [6,7,18,22,28,30,31,34,40,44,64], four also screened for MND [28,30,40,64] or MCMD [18,22,34,44], and five screened for ANI [28,30,34,40,64]. Seventeen studies (55%) focused on detecting neurocognitive impairments and/or deficits [17,18,20–23,25–27,29,33,35,36,38,41,42,66]. Eight studies (26%) [6,7,18,19,22,31,34,44] used 1991 criteria [5] and five studies (16%) [21,28,30,40,64] used the revised 2007 criteria [3] for diagnosing HAND. It is important to note that many of the studies were published prior to the establishment of the 2007 HAND criteria.

Assessment of functional status

Functional status was measured objectively in nine studies (29%) [20–22,30,34,38,39,44,64] (29%) and subjectively in seven studies (23%) [23,26,28,29,37,40,42]. It is worth noting that functional status was assessed differently across studies, and only three of the studies that objectively assessed functional status [20,29,63] used the recent 2007 Frascati criteria to classify participants.

Length of time of reference test/criterion

We were interested in determining whether the quality and rigour of the criterion or reference test used was related to the outcome of the screening tests. We examined and coded the length and comprehensiveness of the neuropsychological test battery into ‘short’, ‘medium’ and ‘long and comprehensive’ battery (See Table 2 for ‘short’, ‘medium’ and ‘long’ battery criteria). Nine studies (29%) used a ‘short’ [6,23–25,27,33,37,41,43], 11 (35%) used a ‘medium’ [7,22,28–30,32,35,38,40,42,44] and seven (23%) used a ‘long’ [17–21,26,36] battery. For the HDS and IHDS, there were sufficient data to evaluate the associations between sensitivity and specificity and battery size. There was a significant association for the HDS between sensitivity and size of battery (P < 0.05), with sensitivity decreasing with increasing battery size. There was a trend for increasing specificity with increasing battery size, but this association was not significant.

Table 2.

Study outcome in literature on screening tools for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.

| Study (Author; Location) | Sample size (total; by group) | Impairment evaluated (type(s); classification system) | Tool characteristics (person can administer; time to administer; materials needed) | Reference test | Reference test details (size of battery; objective assessment; domains assessed; language of administration) | Sensitivity; Specificity | Main findings |

| HIV Dementia Scale (HDS) | |||||||

| Bottiggi et al. [18]; Kentucky, USA | 46 | Types: MCMD, HAD, Neurocognitive Deficits or Impairment (memory, attention, psychomotor, and construction); Classification: 1991 | Person: NR; Time: NR; Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: long; Objective: NR; Domains: Intelligence, attention/concentration, memory, language, executive functioning, visuo-spatial, speed of processing, motor; Language: English | Cut-off ≤10: Sensitivity: 0.36; Specificity: 0.94; | HDS is not efficient in predicting the presence of subtle and mild HIV-dementia. |

| Carey et al. [19]; San Diego, USA | 190 | Type: NP impaired and unimpaired; Classification: DSM-IV 1994, AAN 1991, Grant and Atkinson 1995 | Person: NR; Time: 5 min; Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: long; Objective: NR; Domains: Intelligence, attention/concentration, memory, language, executive functioning. visuo-spatial, speed of processing, motor; Language: English | Cut-off <11: Sensitivity: 0.09; Specificity: 0.98; | HDS is less accurate than paired NP test combinations- Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised (HVLTR; Total Recall) and the Grooved Pegboard Test nondominant hand (PND) pair, and the HVLTR and WAIS-III Digit Symbol (DS) subtest pair in classifying HIV-positive participants as NP impaired or not. |

| Ganasen et al. [24], Western Cape, South Africa | 474 | Type: NP impaired and unimpaired; Classification: MMSE used as the gold standard | Person: NR; Time: NR; Materials: NR | Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | Size: short; Objective: NR; Domains: Attention/concentration, memory, motor; Language: Xhosa, Afrikaans | Cut-off ≤10: Sensitivity: 0.80; Specificity: 0.80; | HDS and MMSE were significantly correlated and showed significant agreement. Nonetheless, the HDS identified more participants who demonstrated cognitive impairment than the MMSE. HDS cut-off of ≤10 yielded a sensitivity of 80%, specificity of 80% and discriminated between the presence and absence of cognitive impairment 90% of the time. |

| Lyon et al. [31]; Washington, DC, USA | 71 | Type: HAD, HIV encephalopathy in adolescents; Classification: 1991 | Person: NR; Time: 10 min; Materials: NR | ANI 1991 Criteria | Size: NR; Objective: NR; Domains: Intelligence, attention/memory, language. Language: NR | Cut-off of ≤10: Sensitivity: 0.83; Specificity: 0.79; Cut-off of ≤9: Sensitivity: 0.88; Specificity: 0.83; | No statistically significant differences in sensitivity and specificity between the HDS and MMSE. Using standard cut-offs, HDS had 83% sensitivity and 79% specificity, although MMSE had 50% sensitivity and 92% specificity. The optimal cut-off score for the HDS, producing the highest sensitivity and specificity, was ≤9, providing 88% sensitivity and 83% specificity (87% correct classification). |

| Morgan et al. [34]; San Diego, California | 317; 135 (HIV+), 182 (HIV-) | Type: ANI, MCMD, HAD; Classification: 1991 | Person: NR; Time: 5–10 min; Materials: NR | Modified AAN 1991 Criteria and Grant and Atkinson 1995 Criteria | Size: long; Objective: Yes; Domains: NR; Language: NR | Demographically adjusted T-score <40: Sensitivity: 0.71; Specificity: 0.74; Raw cut-off score ≤10: Sensitivity: 0.17; Specificity: 0.94; | In comparison to the traditional HDS cut-off score (raw score total ≤10), use of the demographically adjusted normative standards significantly improved the sensitivity (from 17% to 71%) and overall classification accuracy (increasing the odds ratio from 3 to approximately 6). The application of demographically adjusted normative standards on the HDS improves the clinical applicability and accuracy. |

| Power et al. [6]; Baltimore, USA | 130 | Type: HAD; Classification: 1991 | Person: NR; Time: NR; Materials: NR | Memorial Sloan Kettering Dementia Evaluation; Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE); Grooved Pegboard (PB) | Size: short; Objective: NR; Domains: Attention/ concentration, memory, executive functioning, motor; Language: English | Cut-off ≤10: Sensitivity: 0.80; Specificity: 0.91; | HDS demonstrated greater efficiency in identifying HIV dementia than Grooved Pegboard and the Mini-Mental State Examination. |

| Richardson et al. [38]; Boston area, USA | 40 | Types: Neurocognitive Deficit or Impairment (impairment in attention and concentration, psychomotor functioning, behavioural inhibition, constructional praxis); Classification: Performance at least 2 standard deviation units below established norms on one or more independent NP measures in two or more domains of functioning | Person: NR; Time: 10 min; Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: Medium; Objective: Yes; Domains: Memory, executive functioning, motor; Language: English | Cut-off ≤10: Sensitivity: 0.55; Specificity: 0.75; | HDS prediction resulted in modest sensitivity and moderate specificity. In ROC curve analysis, area under the curve was only modestly better than chance (0.58). Optimal cut-off for the HDS is ≤10. |

| Simioni et al. [40], Geneva, Switzerland | 100 (50 with cognitive complaints, 50 without cognitive complaints) | Types: ANI, MND, HAD; Classification: 2007 | Person: NR; Time: NR; Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: Medium; Objective: No; Domains: Intelligence, attention/concentration, memory, language, executive functioning, speed of processing, motor; Language: NR | Cut-off 10: Sensitivity: 0.54; Specificity: 0.96; Cut-Off 14: Complaining: Sensitivity 0.83; Specificity: 0.63; Noncomplaining: Sensitivity: 0.88; Specificity: 0.67; | Prevalence of HAND is high even in long-standing aviremic HIV-positive patients. HAND without functional repercussion in daily life is most frequent. Cut-off of 14 points or less seemed to provide a useful tool to screen for HANDs. |

| Smith et al. [42]; USA | 90 | Type: Neurocognitive Deficit or Impairment (subtle HIV-related cognitive dysfunction); Classification: Cognitive ‘abnormality’ defined as performance that deviated at least 2 SD units below established norms on at least two independent NP measures | Person: NR; Time: NR (noted ‘brief’); Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: Medium; Objective: No; Domains: Intelligence, memory, executive functioning, visuo-spatial, speed of processing, motor; Language: English | Cut-off ≤10: Sensitivity: 0.39; Specificity: 0.85; | HDS lacks sufficient sensitivity to screen for NP abnormality beyond frank dementia. Intact performance (i.e. performance above established cut-off levels) contributes to a significant number of false-negative errors, suggesting need for NP battery for subtle neurocognitive deficits. |

| Von Giesen et al. [43]; Dusseldorf, Germany | 266; 55 (mildly demented), 211 (not demented) | Types: mild dementia, no dementia; Classification: Mild dementia (HDS score ≤10), No dementia (HDS score >10) | Person: NR; Time: NR (noted ‘brief’); Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: short; Objective: NR; Domains: Motor; Language: German | Sensitivity: NR; Specificity: NR; | Patients with mild dementia showed significant slowing of most rapid alternating movement (MRAM) and significantly prolonged contraction time compared to nondemented patients. Motor performance correlated significantly with time-dependent HDS subscores for psychomotor speed and construction. |

| Wojna et al. [44]; Puerto Rico, USA | 96; 60 (HIV+), 36 (HIV-) | Types: Asymptomatic cognitive impairment, and symptomatic impairment (MCMD, HAD); Classification: modified 1991 | Person: NR; Time: NR (noted ‘rapid’); Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: Medium; Objective: Yes; Domains: Intelligence, memory, executive functioning, speed of processing, motor. Language: Spanish | Cut-off ≤12: Sensitivity: 0.63; Specificity: 0.84; Cut-off ≤13: Sensitivity: 0.87; Specificity: 0.46; | HDS-Spanish total score and subscores for psychomotor speed and memory recall showed a significant difference between HIV-negative women and HIV-positive women with dementia and between HIV-positive women with normal cognition and with dementia. Optimal cut-off point was ≤13. |

| International HIV Dementia Scale | |||||||

| Joska et al. [28]; Cape Town, South Africa | 190; 96 (HIV+); 94 (HIV-) | Types: ANI, MND, HAD; Classification: 2007 | Person: NR; Time: NR; Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: Medium; Objective: No; Domains: Attention/concentration, memory, executive function, visuo-spatial, motor; Language: isiXhosa, Afrikaans | Cut-off of 10: Sensitivity = 0.45; Specificity = 0.79; | In ART-naive sample, HIV-positive individuals displayed greater impairment than HIV-negative individuals on IHDS and range of NP tests. With ROC analysis, the area under curve was 0.64. These data suggest that the IHDS may have limitations as a tool to screen for HAD in South Africa. |

| Muniyandi et al. [64]; Thanjavur, India | 33 | Type: ANI, MND, HAD; Classification: 2007 | Person: NR; Time: NR; Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: NR; Objective: Yes; Domains: NR; Language: NR | NR | Tests that assess cognitive and motor speed may be more helpful than clinical psychiatric interview to spot the AIDS patients who have cognitive impairment. The International HIV Dementia Scale was the most sensitive instrument. |

| Sacktor et al. [7]; Uganda/ Baltimore, USA | 247; 66 (HIV+ USA), 81 (HIV+ Uganda), 100 (HIV- control, Uganda) | Type: HAD; Classification: 1991 | Person: Non-Neurologist; Time: 2–3 min; Materials: Watch with a second hand | Memorial Sloan Kettering Dementia Staging; NP battery | Size: Medium; Objective: Yes; Domains: Attention/concentration, memory, language, executive functioning, speed of processing, motor; Language: English, Luganda | Cut-off ≤10: USA: Sensitivity: 0.80; Specificity: 0.57; Uganda: Sensitivity: 0.80; Specificity: 0.55; | IHDS may be a useful screening test to identify individuals at a risk for HIV dementia in both industrialized and developing world. Full NP testing should be performed to confirm diagnosis of HIV dementia. |

| Singh et al. [41]; Durban, South Africa | 20 | Type: Neurocognitive Deficit or Impairment (moderate and severe); Classification: Moderate – Beyond the norms on at least 2 tests; Severe – three or more tests abnormal | Person: Nonspecialist; Time: 2–3 min; Materials: None | NP battery | Size: short; Objective: NR; Domains: Attention, memory, executive functioning, motor; Language: English, isiZulu | Cut-off of 10: Specificity = 0.88; Sensitivity = 0.50; | Low specificity may limit clinical utility of IHDS. Research needed to verify the high burden on neurocognitive impairment among people with low CD4+ cell count. Larger study needed to validate IHDS in South Africa. |

| CogState | |||||||

| Cysique et al. [20]; Sydney, Australia | 81 | Types: ADC; Neurocognitive Deficits or Impairments (psychomotor speed, working memory, attention, learning); Classification System: ≤−2 SD in 2 of 14 neuropsychological measures (Cysique 2004) | Person: NR; Time: 10–15 min; Materials: Desktop computer | NP battery | Size: long; Objective: Yes; Domains: Intelligence, attention/concentration, memory, language, executive functioning, visuo-spatial, motor; Language: English | Sensitivity: 0.81; Specificity: 0.70; | Study supports utility of brief computerized battery in detection of HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment. Good agreement between standard neuropsychological tests and the CogState indices in identifying neurocognitive impairment. |

| Maruff, 2009; Melbourne, Australia | 293; 20 (ADC), 20 (ADC controls); 253 healthy adults | Type: ADC; Definition: Price and Brew, 1988 | Person: NR; Time: 8–10 min; Materials: Personal computer | NP battery | Size: Medium; Objective: NR; Domains: Memory, visuo-spatial processing, motor; Language: English | Sensitivity: NR; Specificity: NR; | Brief CogState battery has adequate construct validity and is sensitive to subtle cognitive impairment in ADC. Recommends that assessment of attention, processing speed, memory and working memory based only on CogState can support solely on broad conclusions. |

| Overton et al. [35]; St. Louis, USA | 46 | Type: Neurocognitive Deficit or Impairment (mild to moderate impairment); Classification: Carey 2004 | Person: NR; Time: 12–15 min: Materials: Computer and computer program | NP battery | Size: Medium; Objective: NR; Domains: Attention/concentration, memory, language, executive functioning, motor; Language: English | GDS ≥0.5: Sensitivity: NR; Specificity: NR; | Measures of both simple detection tests and identification task correlated with GDS and had the highest level of correlation with tests in CHARTER battery. Other tests correlated poorly with NP testing. Composite score of five tests (significant in ROC analyses) correctly classified 90% of individuals according to impairment. |

| Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | |||||||

| Lyon et al. [31]; Washington, DC, USA | 71 | Type: HIV-Encephalopathy in adolescents; Classification: 1991 | Person: NR; Time: 10 min; Materials: NR | ANI 1991 Criteria | Size: NR; Objective: NR; Domains: NR; Language: NR | Cut-off <24; Sensitivity: 0.50; Specificity: 0.92; | MMSE identified 3 of 6 cases of encephalopathy. HDS appeared to be more clinically useful. |

| Muniyandi et al. [64]; Thanjavur, India | 33 | Type: ANI, MND, HAD; Classification: 2007 | Person: NR; Time: NR; Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: NR; Objective: Yes; Domains: NR; Language: NR | NR | Tests that assess cognitive and motor speed may be more helpful than clinical psychiatric interview to spot the AIDS patients who have cognitive impairment. The International HIV Dementia Scale was the most sensitive instrument. |

| Power et al. [6]; Baltimore, USA | 130 | Type: HAD; Classification: 1991 | Person: NR; Time: NR; Materials: NR | Memorial Sloan Kettering Dementia Evaluation; HIV Dementia Scale (HDS); Grooved Pegboard (PB) | Size: short; Objective: NR; Domains: Attention/ concentration, memory, executive functioning, motor; Language: English | Cut-off ≤28: Sensitivity: 0.50; Specificity: 0.88; | MMSE was less efficient at identifying HIV Dementia than the HDS and the Grooved Pegboard. |

| Brief Neurocognitive Screen (Component Neuroscreen) | |||||||

| Ellis et al. [22]; 15 sites, USA | 301 | Type: MCMD, HAD, Neurocognitive Deficits or Impairment (speed of information processing, mental flexibility, working memory); Classification: 1991 Classification | Person: Non-neurologist; Time: 12–15 min; Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: Medium; Objective: Yes; Domains: Attention/concentration, memory, language, speed of processing, motor; Language: English | Sensitivity: 0.65; Specificity: 0.72; | Designed to estimate the frequency of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. In ROC, when compared with NP battery, the area under the curve was 0.74. Yields (Neuroscreen as a whole) a substantial number of false positives and negatives so more useful for tracking prevalence in large cohorts rather than individual patients. |

| Bender Gestalt Test (BGT) | |||||||

| Muniyandi et al. [64]; Thanjavur, India | 33 | Type: ANI, MND, HAD; Classification: 2007 | Person: NR; Time: NR; Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: NR; Objective: Yes; Domains: NR; Language: NR | NR | Tests that assess cognitive and motor speed may be more helpful than clinical psychiatric interview to spot the AIDS patients who have cognitive impairment. The International HIV Dementia Scale was the most sensitive instrument. |

| California Computerized Assessment Package (CalCAP) Mini Battery | |||||||

| Gonzalez et al. [26]; California, USA | 82 | Type: Neurocognitive Deficits (normal, mild, mild-moderate, moderate, moderate-severe, severe) or Impairments (attention and speed of information processing, abstraction, learning); Heaton 1995 | Person: NR; Time: 10 min; Materials: Computer | NP battery | Size: long; Objective: No; Domains: Attention/concentration, memory, executive functioning, visuo-spatial, speed of processing, motor; Language: English | Cut-off D-score of ≥0.5: Sensitivity: 0.68; Specificity: 0.77; | Traditional NP batteries and computerized reaction time tests do not measure the same thing. They are not interchangeable in examining HIV-related NP impairment. |

| Coin Rotation Test | |||||||

| Minor et al. [33]; Louisiana, USA | 204 | Type: Neurocognitive Deficits or Impairment (psychomotor performance); Classification: NR | Person: not specified; Time: 1 min; Materials: NR (infer coin and timer) | Psychomotor speed subscale of the modified HIV Dementia Scale (MHDS-PS). | Size: short; Objective: NR; Domains: Memory, executive functioning, motor; Language: English | Cut-off of 20 Rotations: Sensitivity: 0.72; Specificity: 0.61; | Good convergent validity between Coin Rotation Test and Modified HDS. Gender did not significantly affect CRT performance but did affect modified HDS performance. CRT performance was less affected by education than MHDS performance. |

| The Computer Assessment of Mild Cognitive Impairment | |||||||

| Becker et al. [17]; USA | 59; 29 (HIV+), 30 (HIV-) | Type: Neurocognitive Deficits or Impairment (normal, borderline, impaired); Classification: Global Impairment Rating (Woods, 2004) | Person: Health Professionals; Time: 20 min; Materials: Tablet with touch screen | NP battery | Size: long; Objective: NR; Domains: Memory, language, executive functioning, visuo-spatial, speed of processing, motor; Language: English | Sensitivity: 0.72; Specificity: 0.97; | Detected mild impairment and median stability over 12 and 24 weeks of follow-up was 0.32 and 0.46 (did not differ as a function of serostatus). Discriminate functional analysis (6 CAMCI scores) correctly classified 90% of subjects. |

| Four-item scale from Health Survey; Six-item scale from MOS | |||||||

| Revicki et al. [37]; Baltimore, USA | 162 (baseline); 131 follow-up | Type: Mild, Severe impairment; Classification: TMT manual (Reitan, 1992) | Person: NR; Time: less than 2 min; Materials: NR | Trail-Making Test (TMT) | Size: short; Objective: No; Domains: Executive functioning, speed of processing, motor; Language: English | Sensitivity: NR; Specificity: NR; | Logistic regression analysis showed both four-item version (CF4) included in the HIV Health Survey and the complete six-item scale (CF6) from the Medical Outcomes Study - MOS predicted mild cognitive impairment based on TMT scores (P = 0.046–0.008) and severe cognitive impairment based on TMT scores (P = 0.0012–0.0003). Baseline significant differences in mean CF6 and CF4 scores for mildly impaired compared with less than mildly impaired and severely impaired and less than severely impaired. |

| Grooved Pegboard | |||||||

| Power et al. [6]; Baltimore, USA | 130 | Type: HAD; Classification: 1991 | Person: NR; Time: NR; Materials: NR | Memorial Sloan Kettering Dementia Evaluation; HIV-Dementia Scale (HDS); Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE); | Size: short; Objective: NR; Domains: Attention/concentration, memory, executive functioning, motor; Language: English | Cut-off ≥90 s: Sensitivity: 0.91; Specificity: 0.82; | Was efficient in detecting HAD (86%) compared with the HDS (84%) and MMSE (72%). |

| Brief Cognitive Screen (BCS) – memory subtest, verbal fluency items and conflicting stimulus test of the High Sensitivity Cognitive Screen (HSCS) | |||||||

| Fogel [23]; 3 locations, USA | 156 | Type: Neurocognitive Deficits or Impairment (memory, verbal fluency, conflicting stimulus); Classification: Abnormality on the Brief Dementia Screen | Person: NR; Time: NR; Materials: NR | Standardized Dementia Screen (registration and delayed memory for three simple words, months in reverse, five serial sevens, and orientation to month and year) | Size: short; Objective: No; Domains: Memory, language, orientation; Language: English | Sensitivity: NR; Specificity: NR; | Patients with abnormal scores on the Brief Cognitive Screen showed greater symptoms and functional impairment. |

| HIV Dementia Diagnostic Test | |||||||

| Kwasa et al. [30]; Kisumu, Kenya | 26; 14 (ANI, MND), 6 (HAD) | Type: ANI, MDN,HAD; Classification: 2007 | Person: Nonphysician health-care worker; Time: NR; Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: Medium; Objective: Yes; Domains: Attention/concentration, memory, language, executive functioning, speed of processing, motor; Language: English, Dhulou | Cut-off ≤22: Sensitivity: 0.63; Specificity: 0.67; | Moderate sensitivity and specificity for HAD. Reliability was poor, suggesting that substantial training and formal evaluations of training adequacy will be critical. |

| Hopkins verbal test –revised – and Grooved Pegboard Test Nondominant Hand | |||||||

| Carey et al. [19]; San Diego, USA | 190 | Type: Neurocognitive Deficits or Impairment (NP impaired or unimpaired) Classification: DSM-IV 1994, AAN 1991, Grant and Atkinson 1995 | Person: Trained psychometrist; Time: 5 min; Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: long; Objective: NR; Domains: Intelligence, attention/concentration, memory, language, executive functioning, visuo-spatial, speed of processing, motor; Language: English | Sensitivity: 0.78; Specificity: 0.85; | The combination of Hopkins Verbal Test-Revised and Grooved Pegboard Test Nondominant Hand was more accurate than the HIV Dementia Scale (HDS) in classifying HIV-positive participants as NP impaired or unimpaired. |

| Hopkins Verbal Learning Test/WAIS-III Digit Symbol | |||||||

| Carey et al. [19]; San Diego, USA | 190 | Type: Neurocognitive Deficits or Impairment (NP impaired and unimpaired) Classification: DSM-IV 1994, AAN 1991, Grant and Atkinson 1995 | Person: Trained Psychometrist; Time: 5 min; Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: long; Objective: NR; Domains: Intelligence, attention/concentration, memory, language, executive functioning, visuo-spatial, speed of processing, motor; Language: English | Sensitivity: 0.75; Specificity: 0.92; | The combination of Hopkins Verbal Test-Revised and WAIS-III Digit Symbol (DS) subtest was more accurate than the HIV Dementia Scale (HDS) in classifying HIV-positive participants as NP impaired or unimpaired. |

| Medical Outcome Study HIV (MOS-HIV) Health Survey | |||||||

| Knippels et al. [29]; the Netherlands and Flanders, Belgium | 82 | Type: Neurocognitive Deficits or Impairment (neuropsychological impairment); Classification: NR | Person: Completed at home; Time: NR; Materials: Questionnaire | NP battery | Size: Medium; Objective: No; Domains: Attention/concentration, memory, language, executive functioning, visuo-spatial, motor; Language: Dutch | Sensitivity: NR; Specificity: NR; | Showed significant associations with NP test performance overall and, specifically, with the domains of abstraction, language, visuo-spatial abilities (controlling for CD4+ cell count and CDC disease stage). Trend towards significance in memory domain. Seems particularly sensitive to changes in NP test performance in early HIV infection. |

| Mental Alternation Test | |||||||

| Jones et al. [27]; Baltimore, USA | 62 | Type: Neurocognitive Deficits or Impairment (orientation, memory, concentration, language, praxis, psycho or speed, sequencing ability); Classification: abnormal performance on MMSE and Trailmaking (Crum 1993, Nornstein, 1985) | Person: NR; Time: 60 s; Materials: NR; | Mini-Mental State Examination; Trailmaking Part A and B | Size: short; Objective: NR; Domains: Intelligence, attention/concentration, memory, language, executive functioning, speed of processing; Language: English | With MMSE: Sensitivity: 0.95; Specificity: 0.79; With Trailmaking: Sensitivity: 0.78; Specificity: 0.93; | Scores correlated significantly with MMSE and Trailmaking Test Part B scores when controlled for confounders. ROC curve showed cut-off of 15 yielded best results for detection of abnormal performance on MMSE and Trailmaking Test Part B. |

| Motor Battery (Timed Gait, Grooved Pegboard, Finger-tapping) | |||||||

| Parsons et al. [36]; USA | 361 | Type: Neurocognitive Deficits or Impairment (attention, executive, figural memory, verbal memory, language); Classification: NR | Person: NR; Time: NR (noted ‘brief’); Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: long; Objective: NR; Domains: Attention/concentration, memory, language, executive functioning, visuo-spatial, speed of processing, motor; Language: English | Cut-off of −0.42: Sensitivity: 0.79; Specificity: 0.76; | Significant correlation with comprehensive battery (52% variance). Increased variance to 73% when Digit Symbol and Trailmaking added. Motor battery may have broader utility to diagnose and monitor HIV-related neurocognitive disorder in international settings. |

| Prospective and Retrospective Memory Questionnaire (PRMQ) | |||||||

| Garvey et al. [25]; London, UK | 45 | Types: Neurocognitive Deficits or Impairment (asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment aNCI, memory); Classification: aNCI- performance score more than 1 SD below the normative mean in at least 2 domains of CogState. | Person: NR; Time: 10 min; Materials: questionnaire, writing utensil | CogState | Size: short; Objective: NR; Domains: Attention/concentration, memory, executive functioning, motor, learning; Language: English | Sensitivity: NR; Specificity: NR; | No statistically significant associations between PRMQ and CogState; questionnaire should not be used as a screening tool. Association between PRMQ and set-shifting task of CogState; questionnaire able to capture part of the executive function deterioration in HIV-associated NCI. |

| Screening Algorithm | |||||||

| Cysique et al. [21]; Sydney, Australia | 127; 97 (HIV+), 30 (HIV-) | Types: Neurocognitive Deficits or Impairment (HAND); Classification: 2007 | Person: Clinical Individual; Time: 3 min; Materials: patient's clinical characteristics | NP battery | Size: long; Objective: Yes; Domains: Intelligence, attention/concentration, memory, language, speed of processing, motor, reasoning; Language: English | Sensitivity: 0.78; Specificity: 0.70; | Good overall prediction accuracy and specificity. Proved useful to identify HIV-infected patients with advanced disease at a high risk of HAND who require more formal assessment. Recommended for HIV-infected white men with advanced disease. |

| Timed Gait Test | |||||||

| Robertson et al. [39]; ACTG sites all over the world | 1549; 1122 (AIDS), 113 (symptomatic), 165 (asymptomatic), 87 (HIV-) | Type: ADC; Classification: Neurologic History (Robertson, 1997) | Person: NR; Time: NR; Materials: Stopwatch, recording sheet | ADC Staging; NP battery | Size: NR; Objective: Yes; Domains: Memory, language, executive functioning, visuo-spatial processing, motor; Language: English | Sensitivity: 0.83; Specificity: 0.59; | Good sensitivity and moderate specificity for detection of ADC. Abnormal Timed Gait scores were also significantly correlated with abnormal scores on neurological and neuropsychological evaluations. Cutting scores on the Timed Gait procedure resulted in reasonably good classification rates of ADC staging, especially for use as a screening tool. |

| Wechster Memory Scale | |||||||

| Muniyandi et al. [64]; Thanjavur, India | 33 | Type: ANI, MND, HAD; Classification: 2007 | Person: NR; Time: NR; Materials: NR | NP battery | Size: NR; Objective: Yes; Domains: NR; Language: NR | NR | Tests that assess cognitive and motor speed may be more helpful than clinical psychiatric interview to spot the AIDS patients who have cognitive impairment. The International HIV Dementia Scale was the most sensitive instrument. |

Criteria for Battery Size: ‘short’ battery – criterion was defined by testing that took <30 min to administer; ‘medium’ battery – criterion was defined by testing that took 30–90 min to administer; and ‘long and comprehensive’ battery – criterion was defined by testing that took >90 min to administer. ADC, AIDS Dementia Complex; aNCI, asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment; ANI, asymptomatic neurocognitive disorder; HAD, HIV-associated dementia; MCMD, minor cognitive-motor disorder; MND, mild neurocognitive disorder; NP, neuropsychological; NR, not reported.

Type of reference test / criterion and sensitivity performance

Twenty-six of the 39 tool evaluations (67%) used a detailed neuropsychological battery as the reference standard [18–22,26,28–30,32,35,36,38,40–44,64]. Fifteen tool evaluations (38%) reported adequate sensitivities (≥0.75). Adequate sensitivities (≥0.75) were reported for the HDS [6,24,31,40,44], IHDS [7,41], CogState [20], Grooved Pegboard [6], Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised/Grooved Pegboard Test Non-Dominant Hand [19], Hopkins Verbal Learning Test/WAIS-III Digit Symbol [19], Mental Alternation Test [27], Motor Battery [36], the Screening Algorithm [21] and the Timed Gait Test [39].

Meta-analysis findings

The HDS and IHDS have been sufficiently studied to perform a meta-analysis for each tool. For inclusion in the meta-analysis, the articles we reviewed were required to use a neuropsychological battery as the reference test; use the neuropsychological battery to classify the participants as ‘impaired’; and report the incidence of impairment, sensitivity and specificity of the tools. Seven studies on the HDS [6,19,34,38,40,42,44] and three studies on the IHDS met these criteria [7,28,41]. One study on the IHDS looked at this tool in two different participant pools [7], and as such, the results from each of the participant pools were included in the meta-analysis.

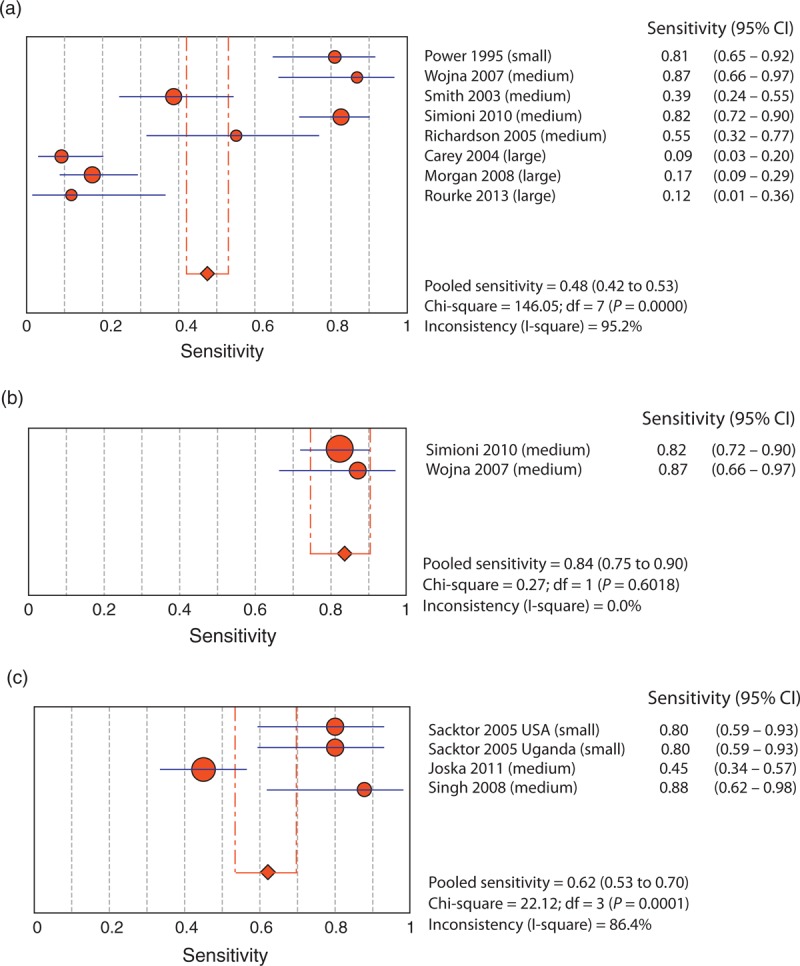

Meta-analysis and qualitative results with the HIV Dementia Scale

The Forest Plot of the meta-analysis of the HDS (Fig. 2a) shows a large range in the sensitivities for the HDS across studies; four studies [19,34,38,42] reported poor sensitivity (i.e. ≤0.55) and three studies [6,40,44] reported good sensitivity (i.e. >0.80). Overall, the pooled sensitivity of these studies (i.e. 0.48) would suggest that the HDS (without any corrections for demographics) is not useful for detecting a range of HAND conditions.

Fig. 2.

Forest plots.

(a) Utility of the HIV Dementia Scale in detecting HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. (b) Utility of the HIV Dementia Scale with cut-off of 13 or 14. (c) Utility of the International HIV Dementia Scale in detecting HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. CI, confidence interval.

The studies that report adequate sensitivities for the HDS fall into three main groups. The first group, the study by Power et al.[6] (sensitivity 0.81), utilized the HDS to detect frank dementia. The second group, studies by Simioni et al.[40] and Wojna et al.[44] (sensitivity 0.82 and 0.87), used a high cut-off score (13 or 14). We meta-analysed these two studies together (Fig. 2b) and determined that the pooled sensitivity increased greatly when only evaluations with higher cut-offs were used (0.84). Finally, Morgan et al.[34] used demographic corrections for age and education (T-scores) and increased the sensitivity from 0.17 with a cut-off of 10 or less to 0.71. These results suggest that the utility of the HDS can be improved by increasing the cut-off score, or by using demographically adjusted T-scores, but only for the detection of dementia.

The two studies with the lowest and comparable sensitivities [i.e. 0.09 and 0.17; Preliminary results from our CIHR Screening study (n = 20) also produced similar results with a sensitivity of 0.12 using a ‘long and comprehensive’ battery (personal communication, S.B.R., 13 March 2013)] both used a ‘long and comprehensive’ reference battery [19,34], whereas those that used a ‘medium’ reference battery [38,40,42,44] had not only higher sensitivities but also a larger range of sensitivities (0.39–0.87). These discrepancies in results using ‘medium’ versus ‘long’ reference batteries suggest that the rigour and comprehensiveness of the battery may be important determinants to consider when evaluting the overall test performance of screening tests for HAND.

Meta-analysis with the International HIV Dementia Scale

The meta-analysis of the IHDS (Fig. 2c) demonstrated more consistency than the HDS, although these studies employed only ‘small’ and ‘medium’ length reference batteries. One [28] study reported a poor sensitivity for the IHDS (0.45) and the other three [7,41] studies reported good sensitivities (≥0.80). Overall, the pooled sensitivity of these studies (0.62) demonstrates that the IHDS may be moderately useful in detecting HAND.

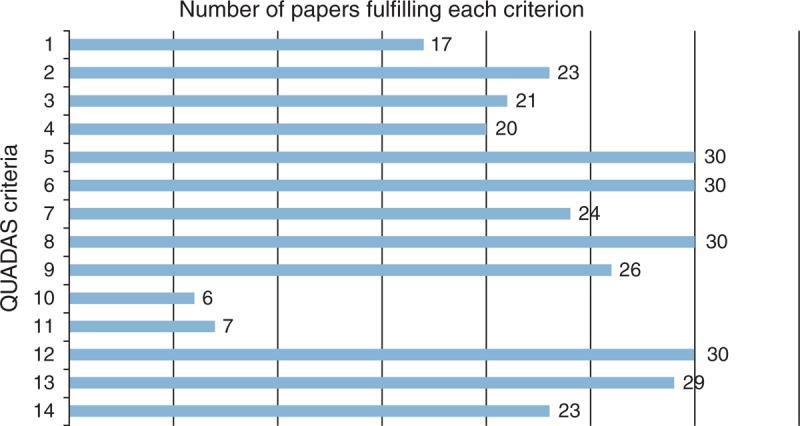

Quality appraisal

The quality assessment demonstrated that there are specific areas in which the studies tend to have methodological shortcomings (Fig. 3). Very few studies fulfilled criteria 10 and 11: 10, ‘Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard?’ (6/31, 19%) [19,22,30,31,41,44] and 11, ‘Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test?’ (7/31, 23%) [19,22,30,31,39,41,44]. This low level suggests that there may be some introduction of bias in the data interpretation, which may result in an overestimation of sensitivity.

Fig. 3.

Number of papers fulfilling the QUADAS criteria (1–14).

Only about half the studies fulfilled criterion 1, ‘Was the spectrum of patients representative of the patients who will receive the test in practice?’ (17/31, 54%) [6,7,17,19,21,22,24,25,27,28,31,32,34,36,37,39,41]. This suggests that there are a good number of studies that may have limited applicability to real-life clinical settings.

The quality assessment did highlight some successful methodologies that should be continued in further evaluations. First, the majority of studies administered the same reference test and screening test to all study participants [criterion 5, ‘Did the whole sample or a random selection of the sample receive verification using a reference standard of diagnosis?’ (30/31, 97%) [6,7,17–28,30–44,64] and criterion 6, ‘Did patients receive the same reference standard regardless of the index test result?’ (30/31, 97%) [6,7,17–33,35–44,64]]. This allowed for proper and comprehensive calculation of sensitivity and specificity. Second, the majority of studies described their procedures with sufficient detail for replication of criterion 8 - ‘Was the executive of the index test described in sufficient detail to permit replication of the test?’ (30/31, 97%) [6,7,17–22,24–44,64], enabling future comparison of newer screening tools to already evaluated tools.

Discussion

With the prevalence of milder forms of HAND increasing, and limited resources available for formal neuropsychological examinations, there is a critical need to be able to screen and identity people with HAND. Our current systematic review identified 51 peer-reviewed articles that focused on screening for neurocognitive impairments associated with HIV/AIDS. Of these, about two-thirds (31/51) used a criterion or reference to characterize the performance of 21 unique screening instruments. About half of the 31 studies examined the performance of the HDS or the IHDS as screening tests. Fifty-five percent of studies focused on detecting neurocognitive impairments, 35% on HAD and 15% in identifying MND or ANI. Only 16% of studies employed the latest 2007 HAND criteria [3].

The results of this systematic review suggest that the HDS and IHDS are not ideal tools for identifying a range of neurocognitive impairment. From the meta-analysis on the HDS and IHDS, we were able to determine that these tools have generally poor (0.48) and moderate (0.62) pooled sensitivities, respectively, in identifying a range of neurocognitive impairment. We also identified a potential relationship between the reference test and criterion with the range of sensitivities on the HDS and the IHDS, that is those studies using the most comprehensive neuropsychological test battery as the ‘gold standard’ criterion had the lowest (and similar) sensitivity values, whereas those that were considered ‘short’ or ‘medium’ in time (and comprehensiveness) resulted in much larger ranges of sensitivities. The association between lower sensitivity (ability to identify true positives) and large reference battery was significant for the HDS (P < 0.05). These findings suggest that a longer, more comprehensive neuropsychological battery may be a more stringent and appropriate reference test. Future studies evaluating sensitivity may want to consider using a large neuropsychological battery as a reference test to classify participants in a more discerning way. Studies using the HDS to identify a range of neurocognitive impairment reported higher sensitivities when higher cut-offs were used [40,44] or demographically adjusted T-scores were used [34].

The review identified 10 other screening tools with adequate sensitivities (≥0.75). Of these, four tools or combinations of tests were used to detect HAND conditions and overall neurocognitive impairment (as opposed to impairment in specific domains) and they used a ‘gold-standard’ neuropsychological battery as the reference test or criterion. These four tools include the CogState [20], the Screening Algorithm [21], the paired Hopkins Verbal Learning Test and WAIS-III Digit Symbol combination and the paired Hopkins Verbal Learning Test and Grooved Pegboard Non-Dominant Hand combination [19]. It is important to note that the other studies defined neurocognitive impairment in different ways and evaluated these conditions using different criteria; thus, the comparison of efficacy across all studies needs to be carried out with caution given these limitations. In addition to these four tests, Becker et al. [17] reported a slightly lower sensitivity (0.72) for the Computer Assessment of Mild Cognitive Impairment (CAMCI) against a comprehensive neuropsychological battery. These are the five tools identified by our review that show some promise to be used to identify HAND in a clinical setting, although they warrant further study and validation.

In the 20 studies that met review criteria and are reported in Appendix B, one other potentially useful tool, The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [48], was highlighted. This tool is worth note because of its rising popularity in clinical settings, although the reliability and validity to detect HAND remains to be determined.

The review also highlighted key methodological issues in this body of literature. First, in order to properly determine whether a screening tool can detect the target condition, it is imperative that the reference test properly classifies the condition [16]. Only 19 studies of the 31 (61%) [18–22,26,28–30,32,35,36,38,40–44,64] used the ‘gold-standard’ neuropsychological battery as the reference test. Furthermore, only seven (23%) studies [17–21,26,36] used more comprehensive reference tests (>90 min) and functional status was measured objectively in only nine studies [20–22,30,34,38,39,44,64] (29%). In addition, only five studies [21,28,30,40,64] used the most recent 2007 criteria to classify HAND [3]. The QUADAS assessment reported that only 17 of the 31 (54%) [6,7,17,21,22,24,25,27,28,31,32,34,36,37,39,41] were using representative samples, noting a severe limitation in the applicability of the studies. For cognitive screening tools to be properly evaluated, and for these evaluations to inform clinical practice, more stringent methodological procedures are needed.

The results of this systematic review provide insights into the performance of the current screening instruments available for HAND and identify key methodological issues that need to be addressed in future studies. In this current context of mild cognitive impairment associated with HIV, it is clear that improved screening tools could go a long way in improving the care, quality of life and study of treatment interventions for individuals living with HIV and AIDS.

Acknowledgements

A.R.Z. contributed to development of systematic review project; reviewed articles for inclusion; extracted data; appraised quality of articles; created figures/tables; analysed data; and wrote the manuscript.

D.G. reviewed articles for inclusion; extracted data; appraised quality of articles; and edited the manuscript.

S.R. contributed to development of systematic review project; edited manuscript; and reviewed articles that were in Spanish.

J.B. contributed to development of systematic review project; and edited the manuscript. A.C. edited the manuscript. J.A.M. contributed to development of systematic review project; and edited the manuscript. M.J.G. contributed to development of systematic review project; and edited the manuscript. A.R. edited the manuscript. R.R. edited the manuscript. G.A. edited the manuscript. T.M. contributed to development of systematic review project; and edited the manuscript. S.B.R. developed systematic review project; organized systematic review team; lead systematic review project; and edited the manuscript.

Funding for this study was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) AIDS Bureau. The findings, opinions and conclusions are those of the authors and no endorsement of these by CIHR or MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Correspondence to Dr Sean B. Rourke, Centre for Research on Inner City Health, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael's Hospital, 30 Bond Street, Toronto, ON M5B 1W8, Canada. Tel: +1 416 864 6060 ext 6482; fax: +1 416 864 5135; e-mail: Sean.rourke@utoronto.ca

References

- 1.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology 2010; 75:2087–2096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vivithanaporn P, Heo G, Gamble J, Krentz HB, Hoke A, Gill MJ, et al. Neurologic disease burden in treated HIV/AIDS predicts survival: a population-based study. Neurology 2010; 75:1150–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology 2007; 69:1789–1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rourke SB, Gill J, Rachlis A, Carvalhal A, Collins E, Arbess G, et al. The Centre for Brain Health in HIV/AIDS HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) in men and women on cART and suppressed plasma viral load: prospective results from the OHTN cohort study. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2013; 24:12A.Canadian Association for HIV Research (CAHR) Conference; 2013; Vancouver, BC. 11–14 April 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen RS, Cornblath DR, Epstein LG, Foa RP. Nomenclature and research case definitions for neurologic manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Report of a Working Group of the American Academy of Neurology AIDS Task Force. Neurology 1991; 41:773–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Power C, Selnes OA, Grim JA, McArthur JC. HIV Dementia Scale: a rapid screening test. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1995; 8:273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sacktor NC, Wong M, Nakasujja N, Skolasky RL, Selnes OA, Musisi S, et al. The International HIV Dementia Scale: a new rapid screening test for HIV dementia. AIDS 2005; 19:1367–1374 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albert SM, Weber CM, Todak G, Polanco C, Coulse R, McElhiney M, et al. An observed performance test of medication management ability in HIV: relation to neuropsychological status and medication adherence outcomes. AIDS Behav 1999; 3:121–128 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Durvasula RS, Hardy DJ, Lam MN, Mason KI, et al. Medication adherence among HIV+ adults: effects of cognitive dysfunction and regimen complexity. Neurology 2002; 59:1944–1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heaton RK, Velin RA, McCutchan JA, Gulevich SJ, Atkinson JH, Wallace MR, et al. Neuropsychological impairment in human immunodeficiency virus-infection: implications for employment. HNRC Group. HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. Psychosom Med 1994; 56:8–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcotte TD, Wolfson T, Rosenthal TJ, Heaton RK, Gonzalez R, Ellis RJ, et al. A multimodal assessment of driving performance in HIV infection. Neurology 2004; 63:1417–1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woods SP, Iudicello JE, Moran LM, Carey CL, Dawson MS, Grant I. HIV-associated prospective memory impairment increases risk of dependence in everyday functioning. Neuropsychology 2008; 22:110–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Mindt MR, Sadek J, Moore DJ, Bentley H, et al. The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2004; 10:317–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trepanier LL, Rourke SB, Bayoumi AM, Halman MH, Krzyzanowski S, Power C. The impact of neuropsychological impairment and depression on health-related quality of life in HIV-infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2005; 27:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marder K, Albert SM, McDermott M. Prospective study of neurocognitive impairment in HIV (DANA cohort): dementia and mortality outcomes. J Neurovirol 1998; 4 Suppl:358 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003; 3:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becker JT, Dew MA, Aizenstein HJ, Lopez OL, Morrow L, Saxton J. Concurrent validity of a computer-based cognitive screening tool for use in adults with HIV disease. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2011; 25:351–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bottiggi KA, Chang JJ, Schmitt FA, Avison MJ, Mootoor Y, Nath A, et al. The HIV Dementia Scale: predictive power in mild dementia and HAART. J Neurol Sci 2007; 260:11–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carey CL, Woods SP, Rippeth JD, Gonzalez R, Moore DJ, Marcotte TD, et al. Initial validation of a screening battery for the detection of HIV-associated cognitive impairment. Clin Neuropsychol 2004; 18:234–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cysique LA, Maruff P, Darby D, Brew BJ. The assessment of cognitive function in advanced HIV-1 infection and AIDS dementia complex using a new computerised cognitive test battery. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2006; 21:185–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cysique LA, Murray JM, Dunbar M, Jeyakumar V, Brew BJ. A screening algorithm for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. HIV Med 2010; 11:642–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellis RJ, Evans SR, Clifford DB, Moo LR, McArthur JC, Collier AC, et al. Clinical validation of the NeuroScreen. J Neurovirol 2005; 11:503–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fogel BS. The high sensitivity cognitive screen. Int Psychogeriatr 1991; 3:273–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganasen KA, Fincham D, Smit J, Seedat S, Stein D. Utility of the HIV Dementia Scale (HDS) in identifying HIV dementia in a South African sample. J Neurol Sci 2008; 269:62–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garvey LJ, Yerrakalva D, Winston A. Correlations between computerized battery testing and a memory questionnaire for identification of neurocognitive impairment in HIV type 1-infected subjects on stable antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2009; 25:765–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez R, Heaton RK, Moore DJ, Letendre S, Ellis RJ, Wolfson T, et al. Computerized reaction time battery versus a traditional neuropsychological battery: detecting HIV-related impairments. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2003; 9:64–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones BN, Teng EL, Folstein MF, Harrison KS. A new bedside test of cognition for patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119:1001–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joska JA, Westgarth-Taylor J, Hoare J, Thomas KGF, Paul R, Myer L, et al. Validity of the International HIV Dementia Scale in South Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2011; 25:95–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knippels HMA, Goodkin K, Weiss JJ, Wilkie FL, Antoni MH. The importance of cognitive self-report in early HIV-1 infection: validation of a cognitive functional status subscale. AIDS 2002; 16:259–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwasa J, Cettomai D, Lwanya E, Osiemo D, Oyaro P, Birbeck GL, et al. Lessons learned developing a diagnostic tool for HIV-associated dementia feasible to implement in resource-limited settings: pilot testing in Kenya. PLoS One 2012; 7:e32898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lyon ME, McCarter R, D’Angelo LJ. Detecting HIV associated neurocognitive disorders in adolescents: what is the best screening tool?. J Adolesc Health 2009; 44:133–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maruff P, Thomas E, Cysique L, Brew B, Collie A, Snyder P, et al. Validity of the CogState brief battery: relationship to standardized tests and sensitivity to cognitive impairment in mild traumatic brain injury, schizophrenia, and AIDS dementia complex. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2009; 24:165–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minor KS, Jones GN, Stewart DW, Hill BD, Kulesza M. Comparing two measures of psychomotor performance in patients with HIV: the Coin Rotation Test and the Modified HIV Dementia Screen. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 55:225–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgan EE, Woods SP, Scott JC, Childers M, Beck JM, Ellis RJ, et al. Predictive validity of demographically adjusted normative standards for the HIV Dementia Scale. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2008; 30:83–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Overton E, Kauwe J, Paul R, Tashima K, Tate D, Patel P, et al. Performances on the CogState and standard neuropsychological batteries among HIV patients without dementia. AIDS Behav 2011; 15:1902–1909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parsons TD, Rogers S, Hall C, Robertson K. Motor based assessment of neurocognitive functioning in resource-limited international settings. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2007; 29:59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Revicki DA, Chan K, Gevirtz F. Discriminant validity of the Medical Outcomes Study cognitive function scale in HIV disease patients. Qual Life Res 1998; 7:551–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richardson MA, Morgan EE, Vielhauer MJ, Cuevas CA, Buondonno LM, Keane TM. Utility of the HIV dementia scale in assessing risk for significant HIV-related cognitive-motor deficits in a high-risk urban adult sample. AIDS Care 2005; 17:1013–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robertson K, Wong M, Musisi S, Ronald A, Katabira E, Robertson KR, et al. Timed Gait test: normative data for the assessment of the AIDS dementia complex. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2006; 28:1053–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, Rimbault Abraham A, Bourquin I, Schiffer V, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. AIDS 2010; 24:1243–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh D, Sunpath H, John S, Eastham L, Gouden R. The utility of a rapid screening tool for depression and HIV dementia amongst patients with low CD4 counts: a preliminary report. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg) 2008; 11:282–286 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith CA, van Gorp WG, Ryan ER, Ferrando SJ, Rabkin J. Screening subtle HIV-related cognitive dysfunction: the clinical utility of the HIV dementia scale. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003; 33:116–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Von Giesen HJ, Haslinger BA, Rohe S, Koller H, Arendt G. HIV dementia scale and psychomotor slowing: the best methods in screening for neuro-AIDS. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005; 17:185–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wojna V, Skolasky RL, McArthur JC, Maldonado E, Hechavarria R, Mayo R, et al. Spanish validation of the HIV Dementia Scale in women. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2007; 21:930–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diehr MC, Cherner M, Wolfson TJ, Miller SW, Grant I, Heaton RK. The 50 and 100-item short forms of the paced auditory serial addition task (PASAT): demographically corrected norms and comparisons with the full PASAT in normal and clinical samples. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2003; 25:571–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dunlop O, Bjoklund R, Abdelnoor M, Myrvang B. Total reaction time: a new approach in early HIV encephalopathy?. Acta Neurol Scand 1993; 88:344–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunlop O, Bjorklund RA, Abdelnoor M, Myrvang B. Five different tests of reaction time evaluated in HIV seropositive men. Acta Neurol Scand 1992; 86:260–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koski L, Brouillette MJ, Lalonde R, Hello B, Wong E, Tsuchida A, et al. Computerized testing augments pencil-and-paper tasks in measuring HIV-associated mild cognitive impairment. HIV Med 2011; 12:472–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kovner R, Lazar JW, Lesser M, Perecman E. Use of the Dementia Rating Scale as a test for neuropsychological dysfunction in HIV-positive iv drug abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat 1992; 9:133–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kvalsund MP, Haworth A, Murman DL, Velie E, Birbeck GL. Closing gaps in antiretroviral therapy access: human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia screening instruments for nonphysician healthcare workers. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009; 80:1054–1059 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maj M, D’Elia L, Satz P, Janssen RS, Zaudig M, Uchiyama C, et al. Evaluation of two new neuropsychological tests designed to minimize cultural bias in the assessment of HIV-1 seropositive persons: a WHO study. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 1993; 8:123–135 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martin EM, Pitrak DL, Pursell KJ, Mullane KM, Novak RM. Delayed recognition memory span in HIV-1 infection. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1995; 1:575–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McManis SE, Brown GR, Zachary R, Rundell JR. A screening test for subtle cognitive impairment early in the course of HIV infection. Psychosomatics 1993; 34:424–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Messinis L, Kosmidis MH, Tsakona I, Georgiou V, Aretouli E, Papathanasopoulos P. Ruff 2 and 7 Selective Attention Test: normative data, discriminant validity and test-retest reliability in Greek adults. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2007; 22:773–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Njamnshi AK, de Paul Djientcheu V, Fonsah JY, Yepnjio FN, Njamnshi DM, Muna WF. The International HIV Dementia Scale is a useful screening tool for HIV-associated dementia/cognitive impairment in HIV-infected adults in Yaounde-Cameroon. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 49:393–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nokes KM, Nwakeze PC. Assessing cognitive capacity for participation in a research study. Clin Nurs Res 2007; 16:336–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ogunrin OA, Eze EU, Alika F. Usefulness of the HIV Dementia Scale in Nigerian patients with HIV/AIDS. South Afr J HIV Med 2009; 10:38–43 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parker ES, Eaton EM, Whipple SC, Heseltine PNR, Bridge TP. University of Southern California repeatable episodic memory test. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1995; 17:926–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Riedel D, Ghate M, Nene M, Paranjape R, Mehendale S, Bollinger R, et al. Screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) dementia in an HIV clade C-infected population in India. J Neurovirol 2006; 12:34–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Skinner S, Adewale AJ, Deblock L, Gill MJ, Power C. Neurocognitive screening tools in HIV/AIDS: comparative performance among patients exposed to antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med 2009; 10:246–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Waldrop-Valverde D, Nehra R, Sharma S, Malik A, Jones D, Kumar AM, et al. Education effects on the international HIV dementia scale. J Neurovirol 2010; 16:265–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woods SP, Scott JC, Dawson MS, Morgan EE, Carey CL, Heaton RK, et al. Construct validity of Hopkins Verbal Learning Test: revised component process measures in an HIV-1 sample. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2005; 20:1061–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Worth JL, Savage CR, Baer L, Esty EK. Computer-based neuropsychological screening for AIDS dementia complex. AIDS 1993; 7:677–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Muniyandi K, Venkatesan J, Arutselvi T, Jayaseelan V. Study to assess the prevalence, nature and extent of cognitive impairment in people living with AIDS. Indian J Psychiatry 2012; 54:149–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Berghuis JP, Uldall KK, Lalonde B. Validity of two scales in identifying HIV-associated dementia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999; 21:134–140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carey CL, Woods SP, Gonzalez R, Conover E, Marcotte TD, Grant I, et al. Predictive validity of global deficit scores in detecting neuropsychological impairment in HIV infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2004; 26:307–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.