Abstract

Protein C inhibitor (PCI) is a nonspecific, heparin-binding serpin (serine protease inhibitor) that inactivates many plasmatic and extravascular serine proteases by forming stable 1:1 complexes. Proteases inhibited by PCI include the anticoagulant activated protein C, the plasminogen activator urokinase, and the sperm protease acrosin. In humans PCI circulates as a plasma protein but is also present at high concentrations in organs of the male reproductive tract. The biological role of PCI has not been defined so far. However, the colocalization of high concentrations of PCI together with several of its target proteases in the male reproductive tract suggests a role of PCI in reproduction. We generated mice lacking PCI by homologous recombination. Here we show that PCI–/– mice are apparently healthy but that males of this genotype are infertile. Infertility was apparently caused by abnormal spermatogenesis due to destruction of the Sertoli cell barrier, perhaps due to unopposed proteolytic activity. The resulting sperm are malformed and are morphologically similar to abnormal sperm seen in some cases of human male infertility. This animal model might therefore be useful for analyzing the molecular bases of these human conditions.

Introduction

Protein C inhibitor (PCI) was originally described in plasma as an inhibitor of the anticoagulant serine protease activated protein C (1, 2). Since then, we and others have shown that PCI inhibits not only activated protein C but also a variety of other intra- and extravascular proteases. Proteases inhibited by PCI include clotting factors such as thrombin (3), factor Xa (3), factor XIa (3, 4), plasma kallikrein (3, 4), and thrombin-thrombomodulin complex (5); fibrinolytic proteases such as urokinase (3, 6) and tissue plasminogen activator (3); the sperm protease acrosin (7, 8); tissue kallikrein (9); and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) (10). PCI belongs to the subgroup of heparin-binding serpins (serine protease inhibitors), and heparin and other glycosaminoglycans can modulate the activity and target enzyme specificity of PCI (11–14). PCI is present not only in plasma, but also in urine (12) and in many other body fluids and secretions (15). The highest PCI concentrations have been described in seminal plasma (∼200 μg/ml) (15, 16). Laurell and colleagues (15) have furthermore demonstrated the presence of PCI in Graaf follicular fluid, amniotic fluid, saliva, milk, tears, cerebrospinal fluid, and synovial fluid. We have observed PCI also in intestinal fluid and in sweat (unpublished observations). PCI synthesis has been shown in many organs and tissues, including the liver (15), organs of the male and female reproductive tracts (8, 15), tubular cells of the kidney (17), platelets and megakaryocytes (18, 19), and keratinocytes in the epidermis (20). In general, PCI therefore seems to be synthesized in most epithelia lining inner or outer surfaces, and PCI protein is contained in many inner and outer secretions. The function(s) of PCI in these environments, however, is completely unknown at the moment.

We have previously cloned and sequenced the mouse PCI (mPCI) gene (21) and have shown that the deduced amino acid sequence is highly homologous to that of human PCI (22, 23), especially as far as functionally important domains are concerned. The mPCI gene — like the human counterpart — is composed of five exons and four introns with highly conserved exon/intron boundaries. The mPCI gene encodes a prepolypeptide of 405 amino acids, which shares the highest degree of homology (63% identity) with human PCI. The putative reactive site is identical to that of human PCI from P5 to P3′, strongly suggesting a similar protease specificity. Also the putative heparin-binding sites and the “hinge” region are highly homologous in mouse and human PCI.

In order to further validate a possible mouse model we have previously also analyzed the function of mouse PCI and its tissue-specific expression. Using recombinant mouse PCI expressed in Escherichia coli we could show that the mouse protein, like its human counterpart, is also a protease inhibitor, which inactivates urokinase with rate constants similar to those of human PCI (24). Using Northern blotting we could also show that, in mice, high concentrations of PCI mRNA are present in organs of the reproductive tract (25); however, we were not able to detect PCI mRNA in other mouse organs, including the liver.

We have now generated PCI-deficient mice by targeted disruption of the PCI gene. We demonstrate that in male mice the presence of PCI is in fact an absolute requirement for reproduction, since homozygous PCI–/– males are infertile.

Methods

mPCI gene targeting using embryonic stem cells, and generation of mPCI-deficient mice.

A 129S/v mouse genomic library in the Lambda FIX II vector (Stratagene, Vienna, Austria) was screened with mPCI cDNA, and four positive clones were isolated. One of these clones was extensively characterized and used for making the targeting vector to disrupt the PCI gene. A homologous sequence of 9.2 kb in total was introduced into parental pPNT vector, which contains a neomycin phosphotransferase (neo) and a Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase expression cassette (26), yielding targeting vector pPNT.PCI. Briefly, in the first step, a 5.7-kb NcoI-NcoI mPCI fragment encompassing the promoter region, untranslated exon I, intron 1, and part of exon II encoding the first 15 amino acids of PCI was cloned into the NcoI site of pAS2-1 vector. From this vector, a shorter, 4.8-kb EcoRI partially digested fragment (downstream EcoRI derived from the multiple cloning site of pAS2-1 vector) was ligated into the EcoRI site of pPNT, yielding pPNT.PCI1 (12.1 kb). Subsequently, a 4.4-kb EcoRI-NotI fragment (NotI site originates from the Lambda FIX II vector) encoding the last 25 amino acids of exon V, stop codon, and the 3′ flanking region was ligated into EcoRI-NotI–restricted pBluescript II KS+. From this vector it was excised with XhoI and NotI (XhoI originates from the multiple cloning site of pBluescript II KS+) and ligated into XhoI-NotI–digested pPNT.PCI1, yielding pPNT.PCI (16.5 kb). The NotI linearized targeting vector was used for the transfection, by electroporation, of R1 embryonic stem (ES) cells derived from the 129S/v mouse strain (obtained from A. Nagy, Samuel Lunenfeld Institute, Toronto, Canada). Three hundred fifty G418/Ganciclovir-double-resistant clones were screened by comprehensive Southern blotting of the isolated genomic DNA, and five correctly targeted clones were obtained. They were used for aggregation with Swiss morula embryos. Out of seven chimeric mice obtained, only one chimeric male transmitted the genetic information derived from ES cells to the offspring when bred with Swiss females. F1 heterozygous PCI+/– mice derived from different mothers were further intercrossed to produce F2 homozygous PCI–/– mutant mice, heterozygous PCI+/–, and wild-type PCI+/+ mice, which were subsequently used for the analysis. Wild-type and heterozygous control mice used in these studies were littermates of the corresponding knockouts. The overall genetic background of all F1 and F2 animals was 50% 129S/v : 50% Swiss. Genotyping was done by Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA isolated from tail biopsies.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Molecular Research Center Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio, USA) and subjected to reverse transcription and subsequent polymerase chain amplification to show the presence of mouse PCI mRNA in analyzed tissues. Reverse transcription reaction on one microgram of total RNA was made using a 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Vienna, Austria) at 42°C for 60 minutes. The following components were included: an antisense mPCI-specific primer 5′-GGT CAG TAA TGC CAG ACA AGT CAG C-3′ at a final concentration of 0.2 μM, 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 9.0, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate, 50 U of RNase inhibitor, and 20 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase. Subsequently, a sense mouse PCI sequence-specific primer 5′-ACT ATG TAG CCA AGC AGA CCA AGG G-3′ and other components were added to 10 μl of the reaction mixture, which then contained 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 9.0, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate, 0.2 μM of each primer, and 1.0 U of DNA polymerase (Dynazyme EXT; Finnzymes Oy, Espoo, Finland) in a total volume of 25 μl. The mixture was predenatured for 2 minutes at 94°C and then subjected to 35 step cycles of 94°C (35 seconds), 58°C (30 seconds), and 72°C (20 seconds). Amplified DNA fragments exhibited the expected size of 495 bp as judged by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Immunological methods.

Polyclonal antibodies against recombinant mPCI (24) were raised in rabbits according to standard protocols. The IgG fraction was purified by ammonium sulfate precipitation and chromatography on Sephadex DEAE A-50 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) (8).

For preparation of mouse testis extracts, freshly obtained samples were placed in ice-cold solubilization buffer (4 ml/g of testis) containing 200 mM Tris-maleate, pH 6.5, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 100 kallikrein inhibitory units per milliliter aprotinin, and 1% Triton X-100, and then homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer. The extraction mixture was kept on ice for 15 minutes and then centrifuged at 1,500 g for 40 minutes at 4°C. Protein concentrations in the supernatant were determined by the Coomassie Protein Assay (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Illinois, USA).

Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions and transferred to PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore Corp., Bedford, Massachusetts, USA). After the protein transfer, the membranes were blocked with 1.5% nonfat dried milk dissolved in 0.02 M Tris and 0.5 M NaCl and incubated for 1 hour with rabbit anti–mouse PCI IgG (30 μg/ml) in blocking buffer. Control blots were incubated with rabbit preimmune serum.

Thereafter membranes were incubated for 1 hour with horseradish peroxidase–linked anti-rabbit IgG and (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) at a 1:10,000 dilution in the blocking buffer. Peroxidase was visualized with the ECL Plus detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

PCI antigen was measured in serum and testis extracts of PCI+/+ and PCI–/– mice using ELISA as described previously (19). Rabbit anti–mouse PCI IgG, acidified in 0.05 M glycine-HCL, pH 2.5, for 1 hour, was used as a recognition antibody (40 μg/ml). Subsequently, a horseradish peroxidase–labeled anti–mouse PCI IgG (50 μg/ml) isolated from a different rabbit was used for the detection. Purified recombinant mPCI was used to establish a calibration curve.

In vivo fertilization test.

To investigate fertility of female mice, superovulation was induced in PCI+/+ and PCI–/– females (13–14 weeks old, 9 mice in each group), by intraperitoneal injections of 10 U pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (Sigma-Aldrich, Vienna, Austria) followed by 10 U human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG; Sigma-Aldrich) 48 hours later, after which they were mated with wild-type males. Females were checked for the presence of vaginal plugs, and fertilized eggs at the one-cell stage were harvested in M2 medium and were further cultivated in M16 medium up to the blastocyst stage.

To examine fertility of PCI+/+, PCI+/–, and PCI–/– male mice, three sexually mature males (15–17 weeks old) of each genotype were mated in three separate experiments with wild-type females, in which superovulation had been induced as above. In two experiments, oocytes from the females with copulatory plugs were removed from oviducts 20 hours after hCG injection at the one-cell stage. They were treated with M2 medium containing 0.1% hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich) to remove the cumulus cells. Thereafter they were washed in M2 medium and subsequently maintained in M16 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C, 5% CO2, for 2–6 hours for assessment of the presence of male and female pronuclei and of the second polar body. The oocytes were then cultured up to the blastocyst stage. In the third experiment, the eggs from the females with copulatory plugs were removed from the uterus 77 hours after hCG using M2 medium.

In vitro fertilization test and sperm-egg binding assay.

Superovulation was induced in wild-type females as described above. Oocytes collected 13–14 hours after hCG application were used. These oocytes were either surrounded by cumulus cells, cumulus cell–free (removed by treatment with 0.1% hyaluronidase), or zona pellucida–free (removed by treatment with 0.1% proteinase K; Sigma-Aldrich). Enzymatically treated oocytes were washed with preincubated fertilization medium (FertiCult; FertiPro NV, Beernem, Belgium). Three males of each genotype, 15–17 weeks old, were used for the experiments. Sperm were collected from the cauda epididymis of males that had not been mated for at least 3 days but no longer than 7 days. Sperm number and motility (of at least 200 sperm) were determined by light microscopy. Aliquots of 105 capacitated sperm (2 hours, 37°C, 5% CO2) were added to the oocytes surrounded by cumulus cells, cumulus cell–free oocytes, and zona pellucida–free oocytes in 200-μl drops of fertilization medium. Then the aliquots were incubated for 1–4 hours (binding assay) and for 6–18 hours up to the pronuclei stage (in vitro fertilization) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Using a large-bore micropipette, the eggs were washed in M2 medium and photographed and then cultured in M16 medium up to the blastocyst stage.

Histological analysis of mouse tissues.

Male and female mice (20–22 weeks old) were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and testes, epididymes, and seminal vesicles or ovaries were excised and immediately fixed. Samples were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS (1 hour on ice) and processed for standard paraffin embedding. Histological sections (8 μm thick) were made from the paraffin blocs, deparaffinated with xylene, and either stained with hematoxilin and eosin or, in the case of male organs, used for determination of apoptosis by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay. Additionally, samples from male organs were prepared for electron microscopy, in which another batch of samples was fixed with 4% formaldehyde, 0.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 1 hour on ice. After intensive washes in phosphate buffer, the tissue samples were post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 hour, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, and embedded in Epon resin via propylene oxide intermediate steps. Semithin sections (0.5 μm) were produced from the specimen embedded in Epon and stained with toluidine blue. Additionally, 80-nm ultra-thin sections were cut, mounted onto nickel grids, and stained with 4% methanolic uranyl acetate. The TUNEL assay was performed as described by Gavrieli et al. (27), with slight modifications. Shortly, deparaffinated sections were treated with 1% pepsin for 20 minutes. After washes in PBS, pH 7.4, the TUNEL reaction was carried out for 10 minutes at 37°C using digoxigenin-labeled dUTP. A sheep anti-digoxigenin antibody labeled with rhodamine was used to detect incorporated nucleotides. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI and mounted with Citifluor (Agar, Canterbury, United Kingdom).

Determination of the proteolytic activity of testis and ovarian extracts.

Both testes from 10- to 14-week-old mice (6 mice of each genotype) or both ovaries from 16- to 20-week-old mice (six mice of each genotype) were collected in one tube and immediately homogenized in 1.4 ml of 10-mM Tris-buffer, pH 7.4, incubated at 37°C for 1 hour, and subsequently centrifuged twice for 15 minutes at 20,000 g. Aliquots of the supernatants obtained from testes of separate mice were normalized with respect to protein concentration (A280 nm = 0.1) and analyzed for amidolytic activity on H-D-Ile-Pro-Arg-pNA (S-2288®), Glu-Gly-Arg-pNA (S-2444®), H-D-Val-Leu-Arg-pNA (S-2266®), and H-D-Val-Leu-Lys-pNA (S-2251®), essentially as suggested by the manufacturer (Chromogenix, Mölndal, Sweden) and as described previously (9, 12). Experiments were performed in the absence and presence of recombinant mPCI (2 μg/ml final concentration) or amiloride (10 μM final concentration). In the case of S-2251 the assay was run with and without addition of plasminogen (50 μg/ml).

Results

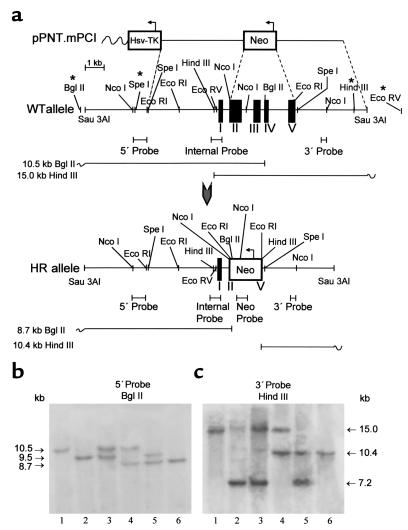

The strategy for mPCI gene inactivation using ES cell technology and for mice genotyping is shown in Figure 1a. Five out of 350 G418/Ganciclovir-double-resistant clones underwent the desired homologous recombination, as confirmed by comprehensive Southern blotting of the isolated genomic DNA from R1 ES cell clones (129S/v genetic background) (data not shown). Chimeric mice (F0), obtained by morula aggregation of the targeted ES cell clones, were test-bred for germline transmission with Swiss mice. One chimeric male transmitted the disrupted PCI allele to its offspring (50% 129S/v : 50% Swiss genetic background), yielding heterozygous PCI-deficient (PCI+/–) mice as identified by Southern blot analysis of tail tip DNA (Figure 1, b and c). Genotyping of wild-type Swiss mice had revealed polymorphism within the 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR of the PCI locus (asterisks in Figure 1a), and transmission of the polymorphic PCI allele, derived from the wild-type Swiss females in F0, through the F1 and F2 generation is illustrated in Figure 1, b and c. Since the closest polymorphic site was about 4 kb upstream from exon I or about 3 kb downstream from the last PCI-coding exon, and since we never experienced any polymorphism within the adjacent 5′ and 3′ UTRs and the coding sequences, we neither sequenced these regions nor further investigated the nature of this polymorphism. Intercrossing of PCI+/– progeny yielded homozygous PCI-deficient (PCI–/–) mice for analysis.

Figure 1.

Disruption of the PCI gene. (a) Genomic organization of the PCI allele in 129S/v mouse strain. Polymorphic restriction sites, present in the majority (more than 90%) of analyzed Swiss mice, are indicated by asterisks. Black boxes in the genomic structure represent exon sequences. Upon homologous recombination, the neo gene replaces a 3.6-kb genomic fragment consisting of a major part of exon II, exons III and IV, and a major part of exon V, leading to complete disruption of the PCI gene. WT, wild type; HR, homologously recombined. (b) Southern blot analysis of mouse genomic DNA digested with BglII and hybridized to a 5′ flanking probe. The appearance of a novel 8.7-kb band indicates correct targeting at the 5′ end of the gene. (c) DNA digested with HindIII and hybridized to a 3′ semi-internal probe C. The appearance of a novel 10.4-kb band indicates correct targeting at the 3′ end of the gene. In b and c, the presence of two fragments differing in size in wild-type mice reflects polymorphism of the PCI allele occurring in the Swiss mice population. Lane 1, PCI+/+ mice with nonpolymorphic wild-type PCI alleles; lane 2, PCI+/+ homozygous mice with polymorphic wild-type PCI alleles; lane 3, PCI+/+ mice with polymorphic and nonpolymorphic wild-type PCI allele; lane 4, PCI+/– mice with nonpolymorphic wild-type PCI allele; lane 5, PCI+/– mice with polymorphic wild-type PCI allele; lane 6, PCI–/– with targeted PCI alleles. Correct targeting of the clones was further checked with additional digests using internal and neo-specific probes (not shown), confirming correct targeting and excluding additional random integration of the targeting vector at other loci.

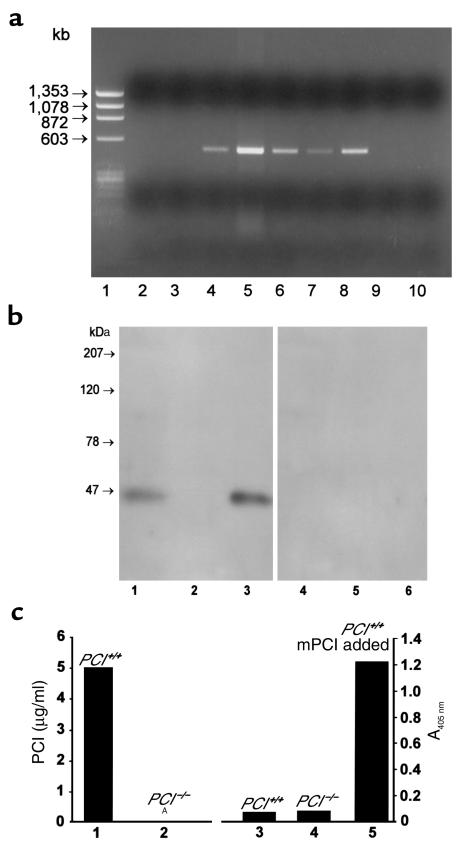

To provide further evidence of the deletion of the PCI allele in the knockout mice at the RNA level, and to refine the analysis of the tissue-specific expression of PCI in wild-type mice, we studied PCI gene expression by RT-PCR (Figure 2a). In wild-type mice we detected PCI in organs of the reproductive tract, which is consistent with previous findings (25, 28) and with findings in humans (15). The highest levels of PCI mRNA were found in the testis, followed by the epididymis, the seminal vesicles, and the prostate. In females, PCI mRNA was detected in ovaries. Only occasionally, trace amounts of PCI mRNA were detected also in the liver (three of seven), kidney (one of five), lung (one of five), adipose tissue (two of five), and brain (one of five) (data not shown). Similar results for mouse livers were reported by van Vuuren et al. (29). No mRNA was detected in the testes and ovaries of PCI–/– mice (Figure 2a, lanes 2 and 3), confirming the correct inactivation of the gene.

Figure 2.

(a) Tissue distribution of PCI mRNA determined by RT-PCR using 1 μg of RNA as template. Lane 1, PhiX 174/HaeIII marker; lane 2, testes of PCI–/– males; lane 3, ovaries of PCI–/– females; lane 4, seminal vesicles of PCI+/+ males; lane 5, testes of PCI+/+ males; lane 6, epididymides of PCI+/+ males; lane 7, prostates of PCI+/+ males; lane 8, ovaries of PCI+/+ females; lane 9, uteri of PCI+/+ females; lane 10, negative control. (b) Western blots. Crude Triton X-100 testis extracts (100 μg protein/lane) of PCI+/+ (lane 1) and PCI–/– (lane 2) mice are shown. Lane 3, recombinant mPCI (50 ng/lane). The samples in lanes 4–6 correspond to the samples in lanes 1–3, but they were incubated with preimmune serum only. (c) ELISA. PCI antigen concentration in crude Triton X-100 testis extracts (10 mg of total protein/ml) of PCI+/+ (lane 1) and of PCI–/– (lane 2) mice. ANo measurable antigen. Lane 3, A405 nm of 50% serum from PCI+/+ mice; lane 4, A405 nm of 50% serum from PCI–/– mice; lane 5, A405 nm of 50% serum from PCI+/+ mice with addition of 200 ng/ml recombinant mPCI (obtained value correlated with standard curve of the assay; not shown).

The absence of PCI antigen was further shown in the testes of PCI–/– mice using Western blotting (Figure 2b, lane 2) and ELISA (Figure 2c, lane 2). Additionally, using ELISA we were able to show the absence of PCI not only in the serum of PCI–/– mice (Figure 2c, lane 4), but also in the serum of PCI+/+ mice (Figure 2c, lane 3). Addition of recombinant mPCI into serum of PCI+/+ mice (Figure 2c, lane 5) resulted in the complete recovery of the measured signal corresponding to the values of the pure mPCI, thus proving the sensitivity of the assay.

Heterozygous PCI+/– mice were apparently normal, and intercrossing yielded litters of normal size (9.2 ± 1.7, mean ± SD) with a mendelian genetic distribution of approximately 25:50:25 (%). Altogether the representation of the PCI– allele in 282 analyzed mice was 52%. Both male and female homozygous PCI–/– mice were born and displayed normal growth and survival, demonstrating the absence of obvious detrimental effects of PCI deficiency on development and growth. Female PCI–/– mice were fertile and yielded litter sizes comparable to those of wild-type females. They also responded normally to an ovulation-inducing hormonal treatment. Their oocytes were fertilized normally in vivo and developed to normal blastocysts in vitro. Consistently, histological analyses of mouse ovaries demonstrated that the overall morphology in PCI–/– mice was normal. Moreover they confirmed that the cycle progressed normally, and the presence of the corpus luteum indicated that at least one ovulation took place (data not shown).

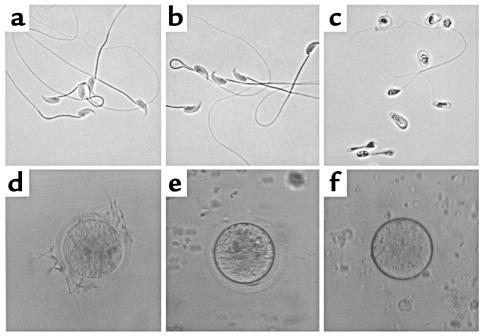

In contrast, male PCI–/– mice were infertile. Breeding four PCI–/– male mice with PCI–/– females during a period of 3 months did not result in any pregnancy, nor did breeding of the same PCI–/– male mice for an additional period of 3 months with wild-type females that had been previously shown to be fertile in mating with wild-type males. Sexual activity of PCI–/– males was normal as revealed by the number of copulation plugs. This strongly indicated a severe defect in the fertilizing capacity of the semen of PCI–/– mice. We performed spermiograms, which revealed that more than 95% of sperm obtained from the epididymis of PCI–/– mice were morphologically abnormal; most lacked tails and were degenerated, and some also had malformed heads. Sperm from PCI+/+ mice and PCI+/– mice appeared morphologically normal (Figure 3, a–c). Similarly, the percentage of motile sperm from PCI–/– males (12.5%) was reduced as compared with PCI+/– (50.5%) and PCI+/+ males (51.5%). In in vivo fertilization experiments, only two oocytes out of the 416 (0.5%) recovered from wild-type females mated with PCI–/– males were fertilized and developed into the blastocyst stage. In the case of females mated with PCI+/+ or PCI+/– males, the percentage of recovered oocytes in the blastocyst stage was 92% (n = 415) and 94% (n = 420), respectively. This indicates almost complete inability of sperm from PCI–/– males to fertilize oocytes of PCI+/+ females.

Figure 3.

Spermiograms and in vitro fertilization assays. Spermiograms from PCI+/+ (a) and from PCI+/– (b) were normal, whereas in spermiograms from PCI–/– mice (c) immature and malformed cells were prevalent. (d) In in vitro fertilization assays, sperm obtained from PCI+/– mice were able to bind and subsequently fertilize PCI+/+ oocytes. Sperm obtained from PCI–/– males failed to fertilize zona pellucida–containing (e) or zona pellucida–free (f) oocytes.

Similarly, in in vitro fertilization experiments sperm obtained from PCI+/+ (not shown) or PCI+/– (Figure 3d) mice were able to bind and to fertilize oocytes from PCI+/+ females, which subsequently developed to the morula/blastocyst stage. No sperm-egg binding or in vitro fertilization was found when sperm obtained from PCI–/– males were incubated with oocytes from PCI+/+ females (n = 90), either surrounded by cumulus cells, cumulus cell–free (Figure 3e), or zona pellucida–free (Figure 3f). In summary, these results indicate that sperm from PCI–/– mice are incapable of fertilization.

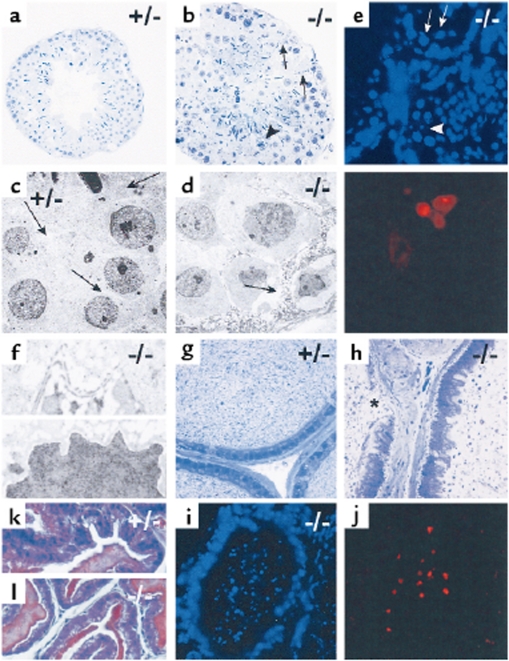

In order to identify the cause of infertility and malformation of sperm, organs of the reproductive tracts of PCI–/– mice were analyzed. Macroscopically, the reproductive organs of PCI–/– mice appeared normal, but histological analysis, including electron microscopy and histochemistry (Figure 4), showed dramatic changes in testes of PCI–/– mice (Figure 4, b, d–f). The lumina of the seminiferous tubules were filled with cells in different stages of spermatogenesis, some of them being apoptotic. The cytoplasm of Sertoli cells contained vacuoles and appeared necrotic. The Sertoli cell barrier appeared disrupted. As demonstrated by the morphology and a TUNEL assay, Sertoli cells did not show characteristic features of apoptosis. Leydig cells appeared normal. In the lumen of the epididymal duct of PCI–/– mice (Figure 4, h and i), malformed, immature, and degenerated cells were prevalent, some of them also apoptotic. In the epididymal duct the cells of the lining epithelium were of irregular shape and the epithelium was missing at some sites. The underlying layer of connective tissue appeared thickened. The morphology of the seminal vesicle appeared normal both in PCI+/– (Figure 4k) and PCI–/– (Figure 4, part l) mice. These data indicate that in PCI–/– mice sperm development is disturbed, likely due to a destruction of Sertoli cells. This malfunction or lack of function of Sertoli cells would lead to partially apoptotic spermatocytes, which in turn would lead to malformed sperm accumulating in the seminiferous tubules and in the epididymal duct.

Figure 4.

Histological analysis of male reproductive organs of PCI+/– and PCI–/– mice. (a–f) Testes of PCI+/– (a, c) and PCI–/– (b, d–f) mice are shown. (a, b) Semithin sections of seminiferous tubules. (c, d) Electron micrographs of seminiferous tubules. Whereas the seminiferous tubule of the PCI+/– mouse shows normal morphology (a), the seminiferous tubule of the PCI–/– mouse (b) has several unusual characteristics. The lumen is filled with immature spermatogenetic cells. The cytoplasm of Sertoli cells appears degenerated (arrows in b and d). Necrotic cells are found in the tubule wall (arrowhead in b) and in the tubule lumen. In c and d, arrows mark the cytoplasm of Sertoli cells. TUNEL assay (e) reveals spermatogenic cells that are positive for apoptosis (arrows), whereas Sertoli cells are devoid of such a signal (arrowhead). Electron micrograph of Sertoli cells of PCI–/– mice (f) shows disrupted Sertoli cell barrier of (upper panel). The nucleus lacks characteristic morphologic features of apoptosis (lower panel). (g–i) Cauda epididymis of PCI+/– (g) and of PCI–/– mice (h and i). In h, the lumen is filled with immature and malformed cells and with cell fragments. The lining cells appear irregular and are occasionally absent (asterisk). TUNEL assay (i) shows many apoptotic cells in the lumen but not in the lining epithelium. The seminal vesicles of both PCI+/– mice (k) and PCI–/– mice (l) appear normal.

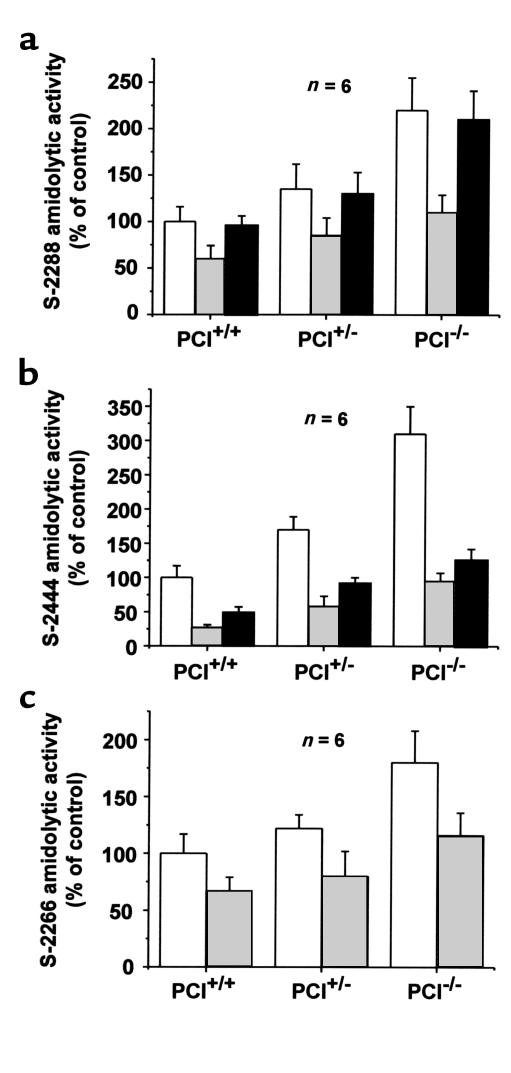

One of the causes of the destruction of the Sertoli cells and of the blood-testis barrier in PCI–/– males might be excessive proteolytic activity in the absence of PCI. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed testis extracts of PCI+/+, PCI+/–, and PCI–/– mice using amidolytic chromogenic substrates. Indeed, significantly higher amidolytic activities (P < 0.05) were found in PCI–/– mice when compared with PCI+/– or PCI+/+ mice in the case of the nonspecific substrate S-2288, the urokinase-specific substrate S-2444, and the tissue kallikrein–specific substrate S-2266, as well as when plasminogen activator activity was determined using the plasmin-specific substrate S-2251 in the presence of human plasminogen. Activity revealed by the nonspecific substrate S-2288 was higher in the testes of PCI–/– mice than in those of PCI+/+ and PCI+/– mice (2.2-fold and 1.6-fold, respectively) (Figure 5a). Using S-2444, a 3.1-fold and 1.8-fold higher amidolytic activity was seen in testis extracts of PCI–/– mice as compared with those of PCI+/+ and PCI+/– mice, respectively (Figure 5b). The tissue kallikrein–like activity, determined by S-2266, of testis extracts of PCI–/– mice compared with that of PCI+/+ or PCI+/– mice was 1.8 and 1.5 times higher, respectively. Concerning the differences in amidolytic activity between PCI+/– and PCI+/+ mice, statistically higher values (P < 0.05) in extracts from PCI+/– mice compared with the PCI+/+ mice were observed only in the case of the S-2444 substrate; however, in this case the differences between the PCI–/– and PCI+/– mice were the highest among all substrates used. With all substrates used, addition of 2 μg/ml recombinant mPCI to the testis extracts caused statistically significant quenching of the amidolytic activity (P < 0.05) to a similar level in all genotypes (Figure 5, a–c). The addition of 10 μM amiloride, a specific inhibitor of urokinase, caused statistically significant quenching of amidolytic activity on the urokinase-specific substrate S-2444 (P < 0.05; Figure 5b). However, it did not cause any significant changes in the amidolytic activity on S-2288; this indicates the presence of an additional protease(s) in mouse testis extracts (Figure 5a). The presence of plasminogen activator activity in mouse testis extracts was confirmed using the plasmin-specific substrate S-2251. In tissue extracts from PCI–/–, PCI+/–, and PCI+/+ male mice, there was no detectable plasmin activity; however, addition of the 50 μg/ml of plasminogen caused rapid plasmin formation, which was highest in tissue extracts of PCI–/– mice, followed by the PCI+/– and PCI+/+ mice (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Amidolytic activities of testis extracts. Extracts were prepared from testes of PCI+/+, PCI+/–, and PCI–/– mice. These extracts were analyzed for amidolytic activity using the nonspecific substrate S-2288 (a), the urokinase-specific substrate S-2444 (b), and the tissue kallikrein–specific substrate S-2266 (c) in the absence of additional components (open bars) or in the presence of 2 μg/ml recombinant mPCI (gray-filled bars) or 10 μM amiloride (filled bars). Data are presented as means ± SEM.

In mouse ovaries the amidolytic activities determined by the nonspecific substrate S-2288 and by the tissue kallikrein–specific substrate S-2266 and normalized to protein concentration were several times lower when compared with proteolytic activities in mouse testes (data not shown). In the case of the S-2288 substrate, the amidolytic activity of ovarian extracts from PCI–/– mice was 2.0 times higher than in those from PCI+/+ mice. In all genotypes the amidolytic activity could be quenched by the addition of 2 μg/ml recombinant mPCI (approximately 25% inhibition). No statistically significant differences (P > 0.05) were found between the PCI+/+, PCI+/–, and PCI–/– mice in the case of the S-2266 substrate, and addition of 2 μg/ml recombinant mPCI to the ovarian extracts did not cause statistically significant quenching of these amidolytic activities. Using the urokinase-specific substrate S-2444, no detectable amidolytic activity was found in the ovaries. The addition of 10 μM amiloride, a specific inhibitor of urokinase, did not cause statistically significant quenching of the amidolytic activities with any of the above substrates used.

Discussion

The biological role of the nonspecific serpin PCI has not been defined so far. PCI is expressed in many human tissues and organs, especially in epithelia lining inner and outer surfaces (15–20), suggesting that PCI might play a role not only for the regulation of the hemostatic system, but also for the regulation of extravascular protease systems. In humans the male reproductive tract contains the highest concentrations of PCI (15, 16). It is therefore not unlikely that PCI is involved in processes related to reproduction, especially since the organs of the reproductive tract also contain many target proteases of PCI (10, 16, 30, 31). In fact, in seminal plasma PCI has been found in complexes with tissue kallikrein (32) and with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) (10, 16). However, the physiological significance of the inhibition of these proteases by PCI remains unknown, especially since the concentration of PCI in semen is lower than that of PSA (16). On the other hand, it has also been suggested that PCI bound to seminal coagula might control their liquefaction by inhibiting proteolytic degradation of semenogelin I and II by PSA (33). Others (7, 34) and we (35) have shown that PCI interferes with sperm-egg binding and with in vitro fertilization, possibly due to its ability to inhibit the sperm protease acrosin (7, 8). However, here too the in vivo relevance of these in vitro findings is questionable, since homozygous male mice with targeted disruption of the acrosin gene are fertile (36). Recently, He et al. (37) have presented clinical evidence that inactive PCI in seminal plasma may be associated with human infertility. Taken together, these findings suggest that PCI might be involved in processes related to reproduction; however, so far it is unclear by which mode of action.

Therefore, in order to clarify a possible mechanism for PCI in the regulation of reproduction, we have established a mouse model with the intention to analyze the consequences of homozygous PCI deficiency. We think that such a mouse model is valid because mouse PCI not only is highly homologous to human PCI (21) but is also a protease inhibitor with similar protease specificity (24). Furthermore, not only in humans but also in mice PCI is highly expressed in the male reproductive tract (25).

In the present study we show that male PCI–/– mice are infertile and that this infertility is caused by abnormal spermatogenesis as shown by spermiograms performed with epididymal sperm and by morphological analysis of the testes. The most striking histological finding in testes from PCI–/– mice was the disruption of the Sertoli cell barrier in the seminiferous tubules with concomitant premature release and degeneration of developing germ cells. Testis extracts of PCI–/– mice exhibited higher amidolytic activity as compared with those of wild-type or heterozygous animals. This amidolytic activity could be quenched by exogenous recombinant mouse PCI and could in part be attributed to the plasminogen activator urokinase. Therefore, increased, unopposed proteolytic activity might directly or indirectly be responsible for the destruction of the Sertoli cell barrier, although at the present stage we cannot exclude other or additional mechanisms. In vitro fertilization experiments performed with epididymal sperm revealed that the disturbances of spermatogenesis in PCI–/– animals are sufficient to explain the observed infertility, even without possible additional effects caused by the absence of PCI from the secretions of the sexual glands.

Female PCI–/– mice reproduced normally and exhibited morphologically normal ovaries. The differences in the effects of disruption of the PCI gene between male and female mice might be due to the differences between the processes of spermatogenesis and oogenesis. While the former is continuous, the latter is completed essentially at birth. The continuous spermatogenesis might result in continuous generation of proteolytic activity that, unopposed by PCI, might result in proteolytic damage of the Sertoli cells and of the blood-testis barrier and in turn abnormal spermatogenesis in PCI–/– males.

Male and female PCI–/– mice did not show any other apparent abnormalities. This is not unexpected, since in mice PCI is almost exclusively expressed in the reproductive tract. Only occasionally and only using RT-PCR, trace amounts of PCI mRNA are found in other organs. Consistently, we were also able to show that in mice PCI is not a plasma protein (Figure 2c). Therefore we did not expect, and indeed we did not observe, any abnormalities of hemostasis in PCI–/– mice. Interestingly, in situ hybridization data recently presented (38) suggest expression of PCI during mouse embryogenesis not only in a variety of epithelia, but also in other tissues, such as skeletal and smooth muscle cells and bony structures. Nevertheless, PCI–/– mice were normal when born, indicating that the absence of PCI has no detrimental effect during development.

In conclusion, unopposed proteolytic activity in male mice lacking PCI might cause distraction of the Sertoli cell barrier and, in turn, failure of sperm development, resulting in infertility. In addition to the clinical findings of He and coworkers (37), malformed sperm — similar to those seen in PCI–/– mice — are a frequent cause of infertility in men (for review see ref. 39). We therefore think that this animal model could be relevant to the analysis of human disease on a molecular level, especially since also in humans the highest expression of PCI is found in the testes.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Nardelli for artwork contributions, M. Sibilia for her help during initial phases of the project, and E. Gils, T. Vancoetsem, K. Bijnens, M. Almeder, J. Zaujec, and I. Jerabek for technical assistance. This work was supported by Austrian Science Foundation grants P13452-BIO and P14067-GEN.

References

- 1.Marlar RA, Griffin JH. Deficiency of protein C inhibitor in combined factor V/VIII deficiency disease. J Clin Invest. 1980;66:1186–1189. doi: 10.1172/JCI109952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suzuki K, Nishioka J, Hashimoto S. Protein C inhibitor. Purification from human plasma and characterization. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.España F, Berrettini M, Griffin JH. Purification and characterization of plasma protein C inhibitor. Thromb Res. 1989;55:369–384. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(89)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meijers JCM, et al. Inactivation of human plasma kallikrein and factor XIa by protein C inhibitor. Biochemistry. 1988;27:4231–4237. doi: 10.1021/bi00412a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rezaie AR, Cooper ST, Church FC, Esmon CT. Protein C inhibitor is a potent inhibitor of the thrombin-thrombomodulin complex. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25336–25339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geiger M, et al. Complex formation between urokinase and plasma protein C inhibitor in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 1989;74:722–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hermans JM, Jones R, Stone SR. Rapid inhibition of the sperm protease acrosin by protein C inhibitor. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5440–5444. doi: 10.1021/bi00184a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng X, et al. Inhibition of acrosin by protein C inhibitor and localization of protein C inhibitor to spermatozoa. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:C466–C472. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.2.C466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ecke S, et al. Inhibition of tissue kallikrein by protein C inhibitor. Evidence for identity of protein C inhibitor with the kallikrein binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7048–7052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensson A, Lilja H. Complex formation between protein C inhibitor and prostate specific antigen in vitro and in human semen. Eur J Biochem. 1994;220:45–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhn LA, et al. Elucidating the structural chemistry of glycosaminoglycan recognition by protein C inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8506–8510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geiger M, Priglinger U, Griffin JH, Binder BR. Urinary protein C inhibitor. Glycosaminoglycans synthesized by the epithelial kidney cell line TCL-598 enhance its interaction with urokinase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11851–11857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pratt CW, Church FC. Heparin binding to protein C inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:8789–8794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ecke S, Geiger M, Binder BR. Heparin binding of protein-C inhibitor. Analysis of the effect of heparin on the interaction of protein C inhibitor with tissue kallikrein. Eur J Biochem. 1997;248:475–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laurell M, Christensson PA, Abrahamsson PA, Stenflo J, Lilja H. Protein C inhibitor in human body fluids. Seminal plasma is rich in inhibitor antigen deriving from cells throughout the male reproductive system. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1094–1101. doi: 10.1172/JCI115689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.España F, et al. Functionally active protein C inhibitor/plasminogen activator inhibitor-3 (PCI/PAI-3) is secreted in seminal vesicles, occurs at high concentrations in human seminal plasma and complexes with prostate specific antigen. Thromb Res. 1991;64:309–320. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(91)90002-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radtke KP, et al. Protein C inhibitor is expressed in tubular cells of human kidney. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2117–2124. doi: 10.1172/JCI117566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishioka J, Ning M, Hayashi T, Suzuki K. Protein C inhibitor secreted from activated platelets efficiently inhibits activated protein C on phosphatidylethanolamine of platelet membranes and microvesicles. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11281–11287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prendes MJ, et al. Synthesis and ultrastructural localization of protein C inhibitor in human platelets and megakaryocytes. Blood. 1999;94:1300–1312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krebs M, et al. Protein C inhibitor is expressed in keratinocytes of human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:32–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zechmeister-Machhart M, et al. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the mouse protein C inhibitor gene. Gene. 1997;186:61–66. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00681-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki K, et al. Characterization of a cDNA for human protein C inhibitor. A new member of the plasma serine protease inhibitor superfamily. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:611–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meijers JCM, Chung DW. Organization of the gene coding for human protein C inhibitor (plasminogen activator inhibitor-3). Assignment of the gene to chromosome 14. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15028–15034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zechmeister-Machhart M, Uhrin P, Malleier J, Binder BR, Geiger M. Mouse and human PCI: two serpins with similar protease activity but different tissue distribution. FASEB J. 2000;14:A54. (Abstr. 79.7.). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zechmeister-Machhart M, et al. Molecular cloning and tissue distribution of the mouse protein C inhibitor (PCI) Immunopharmacology. 1996;32:96–98. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(95)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tybulewicz VL, Crawford CE, Jackson PK, Bronson RT, Mulligan RC. Neonatal lethality and lymphopenia in mice with a homozygous disruption of the c-abl proto-oncogene. Cell. 1991;65:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90011-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gavrieli Y, Sherman Y, Ben-Sasson SA. Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:493–501. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagenaar GTM, et al. Characterization of transgenic mice that secrete functional human protein C inhibitor into the circulation. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Vuuren, A.J.H., Kwast, L., Hofhuis, F.M., Girma, M., and Meijers, J.C.M. 1997. Expression of human protein C inhibitor (PCI) in transgenic mice. Thromb. Haemost. (Suppl.):347. (Abstr. PS-1421.)

- 30.Vihko KK, Kristensen P, Dano K, Parvinen M. Immunohistochemical localization of urokinase-type plasminogen activator in Sertoli cells and tissue-type plasminogen activator in spermatogenic cells in the rat seminiferous epithelium. Dev Biol. 1988;126:150–155. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.España F, et al. Evidence for the regulation of urokinase and tissue type plasminogen activators by the serpin, protein C inhibitor, in semen and blood plasma. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70:989–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.España F, et al. Complexes of tissue kallikrein with protein C inhibitor in human semen and urine. Eur J Biochem. 1995;234:641–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.641_b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kise H, Nishioka J, Kawamura J, Suzuki K. Characterization of semenogelin II and its molecular interaction with prostate-specific antigen and protein C inhibitor. Eur J Biochem. 1996;238:88–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0088q.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elisen MG, et al. Protein C inhibitor may modulate human sperm-oocyte interactions. Biol Reprod. 1998;58:670–677. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.3.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng X, et al. Effect of protein C inhibitor (PCI) on in vitro fertilization. Immunopharmacology. 1996;33:140–142. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(96)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baba T, Azuma S, Kashiwabara S, Toyoda Y. Sperm from mice carrying a targeted mutation of the acrosin gene can penetrate the oocyte zona pellucida and effect fertilization. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:31845–31849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He S, Lin YL, Liu YX. Functionally inactive protein C inhibitor in seminal plasma may be associated with infertility. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5:513–519. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.6.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagenaar, G.T.M., et al. 1999. Towards the role of protein C inhibitor in vivo: developmental expression, and generation and characterization of genetically modified mice. 2nd International Symposium on the Structure and Biology of Serpins. June 27–July 1, 1999. Cambridge, United Kingdom. Abstr. PM69.

- 39.Diemer T, Desjardins C. Developmental and genetic disorders in spermatogenesis. Hum Reprod Update. 1999;5:120–140. doi: 10.1093/humupd/5.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]