Abstract

The heme-binding protein Shp of Group A Streptococcus rapidly transfers its heme to HtsA, the lipoprotein component of the HtsABC transporter, in a concerted two-step process with one kinetic phase. Heme axial residue-to-alanine replacement mutant proteins of Shp and HtsA (ShpM66A, ShpM153A, HtsAM79A, and HtsAH229A) were used to probe the axial displacement mechanism of this heme transfer reaction. Ferric ShpM66A at high pH and ShpM153A have a pentacoordinate heme iron complex with a methionine axial ligand. ApoHtsAM79A efficiently acquires heme from ferric Shp but alters the reaction mechanism to two kinetic phases from a single phase in the wild-type protein reactions. In contrast, apoHtsAH229A cannot assimilate heme from ferric Shp. The conversion of pentacoordinate holoShpM66A into pentacoordinate holoHtsAH229A involves an intermediate, whereas holoHtsAH229A is directly formed from pentacoordinate holoShpM153A. Conversely, apoHtsAM79A reacts with holoShpM66A and holoShpM153A in the mechanisms with one and two kinetic phases, respectively. These results imply that the Met79 and His229 residues of HtsA displace the Met66 and Met153 residues of Shp, respectively. Structural docking analysis supports this mechanism of the specific axial residue displacement. Furthermore, the rates of the cleavage of the axial bond in Shp in the presence of a replacing HtsA axial residue are greater than that in the absence of a replacing HtsA axial residue. These findings reveal a novel heme transfer mechanism of the specific displacement of the Shp axial residues with the HtsA axial residues and the involvement of the HtsA axial residues in the displacement.

In order to obtain the essential nutrient iron during infections, many bacterial pathogens acquire heme from their hosts using a combination of cell wall associated hemoreceptors and secreted hemphores (1–5). In many species of Gram positive bacteria captured heme is thought to be transferred across the cell wall via peptidoglycan hemorecptors, which deliver the heme to specific membrane associated ABC transporters (6, 7), that pump the heme into the cytoplasm (8). Significant advances have been made in understanding the heme acquisition pathways in a number of clinically important Gram positive bacteria (5, 9–11). Works have established the structural basis of heme binding for many hemoreceptors (12–18) and established that heme transfer occurs rapidly via protein-protein heme transfer complexes (19–21). However, how heme is transferred from one protein to another in these processes is not well understood.

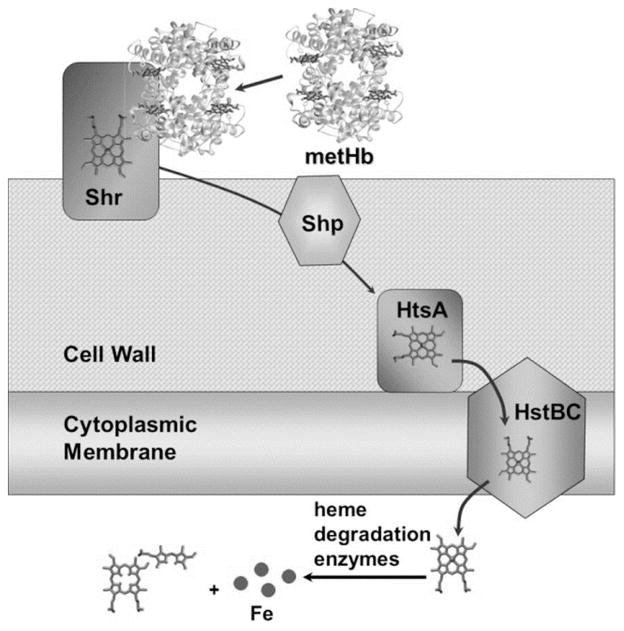

Our laboratory has been studying heme transfer from the surface heme-binding protein Shp to HtsA, the lipoprotein component of the ABC transporter HtsABC in Group A Streptococcus (GAS), as a model system to understand the mechanism of heme transfer among proteins (22). Shp and HtsABC are part of the heme acquisition machinery in GAS, which also includes the cell surface heme-binding protein Shr (23–26). Shr directly acquires heme from human methemoglobin and donates it to Shp (5). Heme can be directly transferred from Shp to HtsA (19), but Shr does not efficiently donate its heme to HtsA (26). These findings support a heme acquisition pathway by the Shr/Shp/HtsABC system in which Shr directly extracts heme from metHb and Shp relays it from Shr to HtsA (Fig. 1). Although the specific proteins vary, similar heme transfer processes occur in other important pathogens including S. aureus and B. anthracis (6, 9, 10, 27).

Figure 1.

A scheme for the proposed model of heme acquisition from metHb by the Group A Streptococcus heme acquisition system consisting of the surface proteins Shr and Shp, lipoprotein HtsA, permease HtsB, and ATPase HtsC. The model is based on the findings in Refs. 5, 7, 19, and 23–26. The model was modified from that in Ref. 9.

Because the Shp to HtsA heme transfer reaction has been well defined, it is an ideal model system to understand the process of heme transfer in Gram positive bacteria. Previously we have shown that Shp and HtsA use the Met66/Met153 and Met79/His229 residues as axial ligands to coordinate the central iron atom within bound heme, respectively (13, 20, 28). The heme complexes of each protein exhibit significantly different UV-Vis absorption spectra, which makes it convenient to spectrally monitor the heme transfer reaction. In our previous work, we demonstrated that Met66Ala and Met153Ala mutations in Shp alter the kinetic mechanism through which heme is transferred to HtsA (20). We also created HtsA axial ligand mutants and characterized how they coordinate heme iron (28). Our previous kinetic analysis led us to hypothesize that heme-bound Shp (HoloShp) first forms a complex with heme-free HtsA (apoHtsA) and subsequently transfers its heme to HtsA with one kinetic phase (19). Based on this kinetic mechanism we proposed that the axial residues of the Shp heme iron are directly displaced by the axial residues of apoHtsA during the heme transfer reaction. Here we present data that support this proposed heme transfer mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins

Recombinant wild-type, Met66Ala (ShpM66A) and Met153Ala (ShpM153A) mutant Shp proteins and wild-type, Met79Ala (HtsAM79A) and His229Ala (HtsAH229A) mutant HtsA proteins were prepared as previously described (20, 28). Purified wild-type and M79A HtsA proteins were a mixture of holo- and apo-forms. Homogeneous apoHtsA proteins were obtained by loading the mixtures on a DEAE column (2.5 × 6 cm) and eluting the column with a 100-ml linear gradient of 0.05–0.15 M NaCl in Tris-HCl, pH 8.0.

Heme Transfer

Heme transfer from ferric holoShp to apoHtsA was monitored by spectral changes associated with heme transfer. Ferric holoShp, holoShpM66A or holoShpM153A was mixed with wild-type, HtsAH229A, or HtsAM79A apoproteins at indicated concentrations in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, in a stopped-flow spectrophotometer equipped with a photodiode array detector (SX20; Applied Photophysics). Absorption spectra of each reaction mixture were recorded at different times after mixing.

Kinetic Analysis of Heme Transfer

Spectra of the heme transfer reactions were recorded with time using the stopped-flow spectrophotometer after mixing wild-type or mutant Shp with apoHtsA mutant protein at ≥ 5 X [holoShp protein] in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Spectral changes at the Soret peak and the charge transfer bands were fit to a single exponential or double exponential equation using the GraphPad Prism Software, yielding observed pseudo-first order rate constants.

Magnetic Circular Dichroism (MCD) Measurements

MCD spectra of oxidized and reduced holoShp proteins in 50 mM phosphate buffer at the indicated pH were recorded using JASCO J-710 spectropolarimeter equipped with an Alpha Scientific 3002-1 electromagnet under the following conditions: bandwidth, 1 nm; accumulation, 3 scans; scan rate, 100 nm/min; resolution, 0.5 nm; magnetic field, 12.9 kG (1.29 tesla); and temperature at 25°C. The spectra of the reduced proteins were taken in the presence of excess dithionite. Buffer blank-corrected CD spectra obtained without magnetic field were subtracted from corresponding buffer-corrected MCD spectra using the Jasco software. These processed MCD data were then used to calculate the final MCD data in units of ΔεM (M·cm·tesla)−1 based on protein concentration, light path, magnetic field, and molar ellipticity ΘM (deg·cm2· dmol−1· tesla−1) = 3300 ΔεM.

Binding of Imidazole to Shp Mutant Proteins

One ml of 7 μM ShpM66A or ShpM153A was mixed with imidazole at 5 to 500 μM and incubated at 20°C for at least 10 min, and the absorption and MCD spectra were recorded. The spectral change in the binding of imidazole to ShpM66A versus imidazole concentration was analyzed using the model of specific one-site binding.

Other Assays and Measurements

Protein concentrations were measured using a modified Lowry protein assay kit (Pierce) with bovine serum albumin as a standard according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Heme content of Shp and HtsA was determined using the pyridine hemochrome assay (29). A SPECTRAmax 384 Plus spectrophotometer was used for absorption measurements, unless otherwise specified.

Structure Modeling and Docking

Modeller version 9.9 (30, 31) was used to generate a three-dimensional (3-D) homology model of apo-HtsA. Initially, Modeller was used to search a library containing the primary sequences of proteins of known structure. The top six related sequences that aligned to HtsA with 24% or greater sequence identity were used as templates to build a model of the three dimensional structure of HtsA. The model of HtsA was then docked to holo-Shp (PDB ID: 2Q7A) using the online RosettaDock server (32). RosettaDock identifies low-energy conformations for the protein-protein complex by simultaneously optimizing side-chain conformations (packing algorithm) and through rigid body docking using a Monte Carlo minimization strategy.

RESULTS

Coordination of the Heme Iron in ShpM66A and ShpM153A

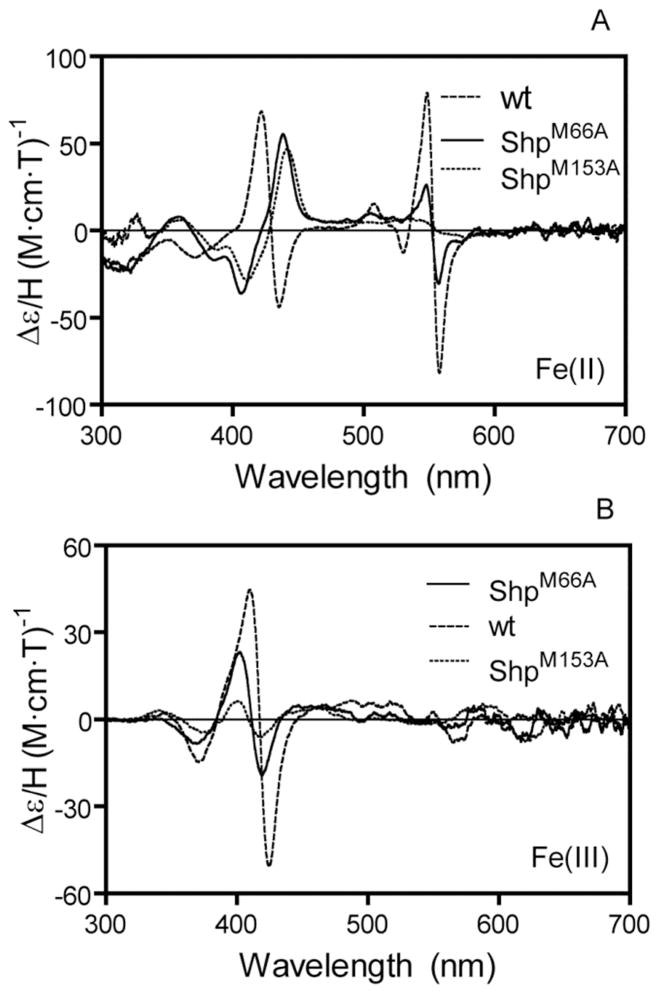

We hypothesize that transfer occurs when one of the axial ligands in Shp is displaced by a ligand from HtsA. We used HtsAM79A, HtsAH229A, ShpM153A and ShpM66A mutants to test the hypothesis as described later. Information on the coordination and axial ligand(s) of the heme iron in these axial HtsA and Shp mutants are critical for the interpretation of spectral and kinetic data of the heme transfer reactions. UV-vis, MCD, RR, and EPR analyses have revealed that ferric HtsAH229A has a high-spin, pentacoordinate heme iron with a methionine axial ligand and that ferrous HtsAH229A and HtsAM79A heme irons are pentacoordinate, whereas ferric HtsAM79A has a high-spin, hexacoordinate heme iron with axial histidine and water ligands (28). This left unresolved how potential heme coordinating ligand in axial Shp mutants interacted with iron. Thus, we examined the heme coordination in ShpM66A and ShpM153A. Resonance Raman analysis uses intense laser light for repeated excitation under which the wt Shp and axial mutant proteins form precipitates. Thus, we used MCD analysis to examine the heme coordination in the Shp mutant proteins. Ferrous wild-type Shp displays a typical low spin hexacoordinate heme iron in the Q band region (Fig. 2A); however, its Soret band has higher ellipticities and a red shift compared with the previously reported Soret band of HtsA with Met and His axial ligation (28). The distinct MCD spectrum of ferrous Shp in the Soret band region is apparently due to the axial ligation of the iron to two Met residues, which has been elucidated by a mutagenesis study (20) and confirmed by the X-ray structure of the heme-binding domain of Shp (13). Ferrous ShpM153A has an MCD profile (Fig. 2A) that is very similar to that of ferrous HtsAH229A, which has a pentacoordinate iron with an axial bond with Met79 (28). This result indicates that ferrous ShpM153A has a pentacoordinate iron that bonds with the axial Met66 residue. Ferric wild-type Shp shows a typical hexacoordinate low-spin MCD spectrum (Fig. 2B). The MCD spectrum of ferric ShpM153A is again very similar to that of ferric HtsAH229A (Fig. 2B). The published UV-Vis spectrum of ferrous and ferric ShpM153A (20) is similar to that of ferrous and ferric HtsAH229A (Table 1) (28). Thus, like HtsAH229A, ShpM153A has a pentacoordinate heme iron with a Met axial ligand (Met66).

Figure 2.

MCD Spectra of ferrous (A) and ferric (B) wild-type (wt), M66A, and M153A Shp in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The reduced spectra were recorded in the presence of excess dithionite.

Table 1.

Heme Coordination and Spectral Features of Wild-type and Mutant HtsA Proteins

| Proteina | Known/proposed axial ligand(s) | Absorption Peaks

|

Major MCD Features

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soret (nm) | ε mM−1 cm−1 | Visible (nm) | Soret (nm) | Δε/H (M cm T)−1 | Visible (nm) | Δε/H (M cm T)−1 | ||

| Shp | Met/Met | 420 | 116 | 529 | 410 | 44.8 | 550 | 2.7 |

| 560 | 417 | 0 | 554 | 0 | ||||

| 424 | −50.9 | 564 | −7.8 | |||||

| ShpM66A (pH 9.0) | Met | 404 | 120 | 486 | 403 | 17.3 | 583 | 4.6 |

| 528 | 412 | 0 | 601 | 0 | ||||

| 604 | 418 | −12.3 | 618 | −9.2 | ||||

| ShpM66A (pH8.0) | Met and Met/H2Oa | 406 | 128 | 490 | 403 | 26.1 | 592 | 3.7 |

| 526 | 411 | 0 | 603 | 0 | ||||

| 601 | 419 | −18.6 | 620 | −6.7 | ||||

| ShpM66A (pH 6.0) | Met/H2O | 408 | 157 | 502 | 403 | 34.2 | 620 | −1.3 |

| 624 | 410 | 0 | 627 | −2.1 | ||||

| 417 | −26 | 632 | −3.5 | |||||

| ShpM153 | Met | 402 | 100 | 480b | 401 | 6.4 | 588 | 5.2 |

| 598 | 409 | 0 | 607 | 0 | ||||

| 418 | −6.3 | 624 | −7.4 | |||||

| c HtsA | Met/His | 412 | 123 | 532 | 407 | 38 | 557 | 1.9 |

| 562b | 416 | 0 | 564 | 0 | ||||

| 423 | −45 | 578 | −5.6 | |||||

| c HtsAM79A | His/H2O | 403 | 187 | 498 | 399 | 20 | 548 | −1.5 |

| 536b | 407 | 0 | 580 | −2 | ||||

| 630 | 414 | −16.5 | 643 | −3.3 | ||||

| c HtsAH229A | Met | 402 | 114 | 482 | 404 | 11 | 589 | 4.9 |

| 524 | 410 | 0 | 608 | 0 | ||||

| 600 | 419 | −7.5 | 624 | −7.2 | ||||

All spectra were measured at pH 8.0 unless specified.

Estimated from shoulders.

Data for HtsA proteins are from Ref. 28.

Ferrous ShpM66A and ShpM153A share similar MCD profiles in the region of 350–450 nm, but ShpM66A has a small derivative signal in the Q band that is similar to that of the wild-type Shp (Fig. 2A), suggesting that a small portion of ferrous ShpM66A might be in a hexacoordinate complex. The MCD profile of ferric ShpM66A is very similar with that of HtsAH229A and ShpM153A; however, the ellipticity of ferric ShpM66A at the Soret band at pH 8.0 is about three times as those of HtsAH229A and ShpM153A. According to the results of a pH titration described later, the higher ellipticities of ShpM66A at pH 8.0 appears to be partly due to the presence of a small portion of ShpM66A that has a hexacoordinate heme iron with a water molecule at the vacated coordination site.

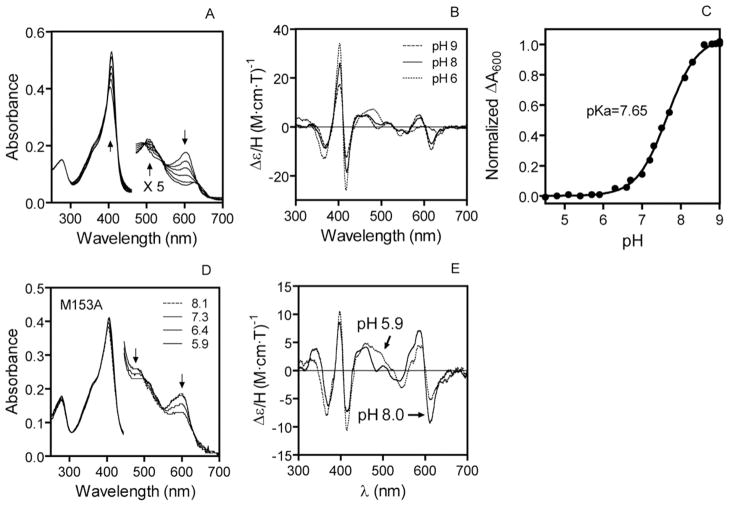

Effects of pH on the Coordination of the Heme Iron in ShpM66A

The UV-Vis spectrum of ferric ShpM66A varied from pH >8.6 to pH 6.0. At pH > 8.6 ferric ShpM66A displayed the absorption peaks at 404, 489, and 600 nm (Fig. 3A). This spectrum is similar to that of ShpM153A and HtsAH229A and, thus, represents a pentacoordinate heme iron complex with one axial bond with Met153. As the pH decreases from pH 8.6 to ≤ 6, the Soret absorption peak increases in intensity and is red shifted. The charge transfer bands in the visible region undergo dramatic changes as well, resulting in an absorption spectrum with peaks at 408, 502, 534, and 624 nm at pH 6 (Fig. 3A). This spectrum resembles that of a hexacoordinate, high spin heme iron with its sixth bond to an axial water molecule, suggesting that ShpM66A had a switch in the heme iron coordination from pentacoordination to hexacoordination due to the binding of a water molecule as the sixth coordination. MCD measurements support this interpretation. The MCD spectra of ferric ShpM66A at basic and acidic pH are similar to that of pentacoordinate HtsAH229A complex and hexacoordinate heme complex, respectively (Fig. 3B). The spectral changes of ferric ShpM66A with pH fit an equation describing the absorbance change with the titration of a single ionizable group with a pKa of 7.6 ± 0.1 (Fig. 3C), indicating that the conversion of the heme iron coordination in ShpM66A is associated with the protonation of a basic group. The UV-Vis spectrum of ferric ShpM153A did not change as dramatically as that of ferric ShpM66A (Fig. 3D). Consistent with this observation, the MCD spectrum of ShpM153A at pH 6.0 was still very similar to that of the protein at pH 8.0, indicating that the majority of the heme iron does not change the coordination when pH decreases from 8.0 to 6.0 (Fig. 3E).

FIGURE 3.

Effect of pH on optical and MCD spectra of ShpM66A and ShpM153A. A, the spectral shift of ShpM66A as a function of pH. pH values: 9.0, 8.1, 7.7, 7.3, 6.7, 5.9. B, MCD spectra of ShpM66A at the indicated pH. C, pH titration curve of A600 of ShpM66A. D and E, Optical and MCD spectra of ShpM153A at different pH the indicated pH. The arrows indicate the direction of the shift as pH decreased.

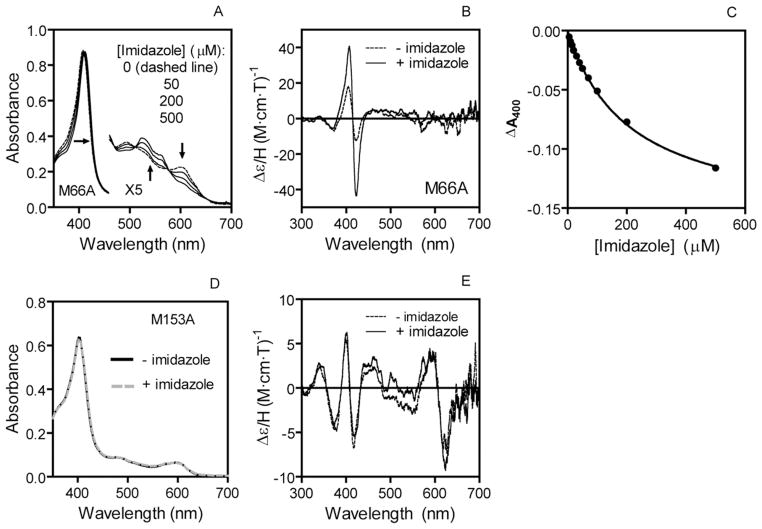

Binding of Imidazole to the Heme Iron in Axial Mutants of Shp

The pH titration results suggest that the empty coordination site in ShpM66A and ShpM153A have different accessibility to external ligands. The understanding of the accessibility would provide clues about the axial displacement process. To investigate this issue we tested the ability of ShpM66A and ShpM153A to interact with free imidazole, which was meant to act as a surrogate for HtsA. Addition of imidazole causes a dose-dependent shift of the ShpM66A absorption spectrum to one that is typical of a hexacoordinate low spin heme iron (Fig. 4A), and the MCD spectrum of ShpM66A in the presence of 0.5 mM imidazole is consistent with the imidazole binding (Fig. 4B). The spectral change as a function of imidazole concentration fit a model of specific one-site binding with a Kd of 210 ± 11 μM (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that imidazole ligates to the ShpM66A heme iron. In contrast, imidazole at 0.5 mM did not alter the absorption and MCD spectra of ShpM153A (Fig. 4C and 4D), indicating that imidazole cannot bind to ShpM153A under these conditions. These results suggest that imidazole can access the alanine 66 position of ShpM66A, but not the alanine 153 position of ShpM153A.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of imidazole on optical (A and D) and MCD (B and E) spectra of ShpM66A and ShpM153. The optical and MCD spectra of each Shp protein in 20 mM Tris-HCl (for optical spectra) or 50 mM potassium phosphate (for MCD), pH 8.0, at the indicated imidazole concentrations. The arrows in panel A indicate the directions of the spectral shifts as imidazole concentrations are shown. C, imidazole titration of ΔA400 of ShpM66A.

Effects of Mutation of the HtsA Heme Axial Ligand Residues on Heme Transfer from Shp to HtsA and its Kinetic Mechanism

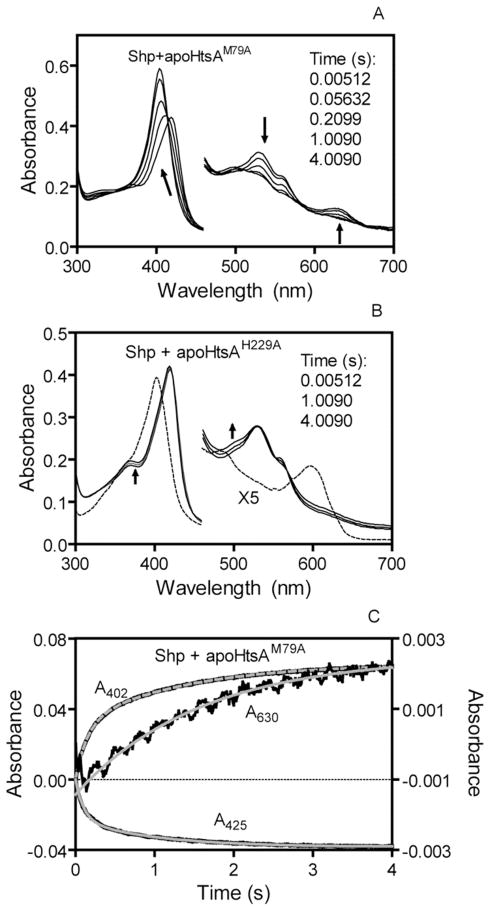

The purpose of this study is to probe the mechanism of heme transfer from Shp to HtsA by using Shp and HtsA heme axial residue mutants. With the information on the spectral features and coordination of the heme iron in the axial Shp and HtsA mutants, we could interpret the heme transfer according to spectral changes during the heme transfer reaction and determine the mechanism of heme transfer by monitoring the kinetics of the spectral changes associated with heme transfer. We first examined effects of the Ala replacements of the HtsA heme axial ligands on the efficiency and kinetic feature of the Shp-to-HtsA heme transfer. In the reaction of ferric Shp and apoHtsAM79A, the Soret peak shifts rapidly from 420 nm to 402 nm with a concurrent decrease of the charge transfer bands at 530 nm and 560 nm, and an additional peak at 630 nm showed up (Fig. 5A). The resulting spectrum has peaks at 402, 498, 536, and 630 nm. This spectrum is same as the reported spectrum of holoHtsAM79A (28). Thus, ferric Shp efficiently transfers its heme to HtsAM79A. However, there was no significant spectral shift after ferric Shp was mixed with excess apoHtsAH229A, and the final spectrum of the mixture was primarily that of holoShp but not holoHtsAH229A (Fig. 5B), indicating that most of the heme was still on Shp. Thus, elimination of the His229 ligand but not the Met79 residue considerably decreases the efficiency of heme transfer from ferric holoShp to apoHtsA.

FIGURE 5.

Spectral and kinetic analyses of heme transfer from ferric holoShp to apoHtsAM79A and apoHtsAH2299A. A, shifts of the absorption spectrum in the reaction of 3.5 μM ferric holoShp with 30 μM apoHtsAM79A in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, at room temperature after mixing in a stopped-flow spectrophotometer. The arrows indicate the directions of the spectral shifts with time. B, absorption spectra of the reaction mixture of 3.5 μM ferric holoShp with 30 μM apoHtsAH229A at the indicated time points after mixing. The spectrum of 3.5 μM holoHtsAH229A (gray line) is included for comparison. C, time course of ΔA402 and ΔA425 at the Soret peak and ΔA630 at the charge transfer bands in the holoShp/apoHtsAM79A reaction as in panel A. The black traces and gray curves represent the observed data and double (for ΔA402 and ΔA425) or single (for ΔA630) exponential fitting curves, respectively.

Next, we determined whether the HtsAM79A mutation changes the kinetic mechanism of the Shp/apoHtsA reaction. We monitored spectral changes of the Soret peak at A402 and A425 and the charge transfer band at A630. ΔA402 and ΔA425 increased and decreased with time, respectively, representing the formation of holoHtsAM79A and disappearance of holoShp, respectively. The time courses of both ΔA402 and ΔA425 fit to a two exponential equation (Fig. 5C), resulting in observed rate constants of 7.4 ± 0.10 s−1 and 0.65 ± 0.02 s−1 from the ΔA402 time course and 7.6 ± 0.12 and 0.70 ± 0.03 s−1 for the ΔA425 time course with 32 μM of apoHtsAM79A (Table 2). There was not much change in ΔA630 in the fast phase, and the ΔA630 time course in the time points for the slower phase fits a single exponential equation, yielding an observed rate constant of 0.63 ± 0.03 s−1. This observed rate was similar to the one for the second kinetic phase in the ΔA402 and ΔA425 time courses. The A630 peak is the absorption of holoHtsAM79A. Thus, the final product was completely formed during the second kinetic phase. Thus, like the M66A and M153A mutations of Shp, the M79A mutation of HtsA results in a change in the kinetic mechanism from one to two kinetic phases. It should be noted that the biphasic kinetics of the holoShp/apoHtsAM79A is more related to the cleavage of the axial bonds in the heme donor whereas the biphasic features of the Shp axial mutant/apoHtsA is more related to the formation of the axial bonds in the holoHtsA product.

Table 2.

Number of kinetic phase and rate constants in heme transfer from Shp proteins to HtsA proteins

| Donor | acceptor | No. of kinetic phase | kt (s−1) | kt1 (s−1) | kt2 (s−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shp | HtsA | 1 | 43 ± 3 | 19 | ||

| Shp | HtsAM79A | 2 | 7.4a | 0.8a | This work | |

| Shp | HtsAH229A | No transfer | This work | |||

| ShpM66A | HtsA | 2 | 8.7 ± 0.3 | 0.38 ± 0.08 | 20 | |

| ShpM66A | HtsAM79A | 1 | 8.6 ± 0.6b | This work | ||

| ShpM66A | HtsAH229A | 2 | 7.0 ± 1.0c | 1.4 ± 0.5c | This work | |

| ShpM153A | HtsA | 2 | 120 ± 30 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 20 | |

| ShpM153A | HtsAM79A | 2 | 8.1 ± 0.4b | 0.48 ± 0.06b | This work | |

| ShpM153A | HtsAH229A | 1 | 14.7 ± 0.3c | This work |

Apparent rate constant obtained at 32 μM apoHtsAM79A.

Apparent rate constant obtained at 10 μM apoHtsAM79A.

Apparent rate constant obtained at 13 μM apoHtsAH229A.

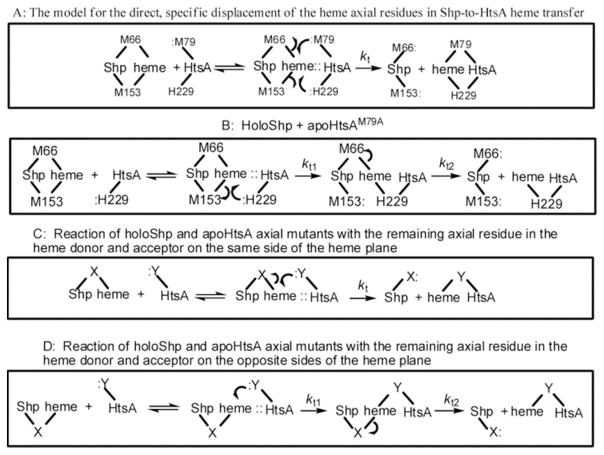

A Model for Axial Ligand Replacement Mechanism in the Shp-to-HtsA Heme Transfer Reaction

The heme transfer reaction involves the cleavage of the two axial bonds of the Shp heme and the formation of the two new axial bonds of the heme in the holoHtsA product. The single kinetic phase of this transfer reaction indicates that the cleavage of the Shp heme axial bonds and the formation of the HtsA heme axial bonds occur at about the same time. We propose that the axial residues of apoHtsA approach the axial bonds along the two sides of the heme in Shp to facilitate the cleavage of the axial bonds and eventually displace the Shp axial residues at about same time (Fig. 6A). The evidence for the specific displacements of the Shp M66 and M153 axial ligands with HtsA M79 and His229, respectively, in this model is presented below. The kinetic mechanism of the Shp/apoHtsAM79A reaction is consistent with and, thus, supports the reaction model in Fig. 6A. The fast phase in the Shp/apoHtsAM79A reaction represents the displacement of the Shp M153-heme iron bond with the HtsA H229 residue, and the slower phase is the cleavage of the Shp M66-heme iron bond because of the lack of the HtsA M79 residue (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Proposed schemes for the reactions among the wild-type and axial mutant proteins of holoShp and apoHtsA. M66/M153 and M79/H229 are the axial ligand residues in Shp and HtsA, respectively, and are also represented by X and Y when their identity and relative locations cannot be specified. The short lines to heme represent the axial bonds to the heme iron. A, the model for the Shp-to-HtsA heme transfer in which the Met66 and M153 axial residues of holoShp are specifically displaced by the Met79 and His229 residues of apoHtsA, respectively. B, reaction scheme for the kinetically biphasic ferric holoShp/apoHtsAM79A reaction. C & D, kinetically single-phase (c) and biphasic (D) reactions of ferric holoShp axial mutants with apoHtsA axial mutants.

Test on the Axial Ligand Displacement Model for the Heme transfer from Shp to HtsA

The axial displacement model in Fig. 6A can be tested by examining heme transfer from ShpM66A and ShpM153A to apoHtsAM79A and apoHtsAH229A. If the remaining axial residue in the HtsA mutants displaces the remaining axial residue in the Shp mutants, the transfer process should have one kinetic phase (Fig. 6C). Otherwise, the reaction should be kinetically biphasic (Fig. 6D). In particular, there should be a hexacoordinate intermediate in the transfer reaction in Fig. 6D.

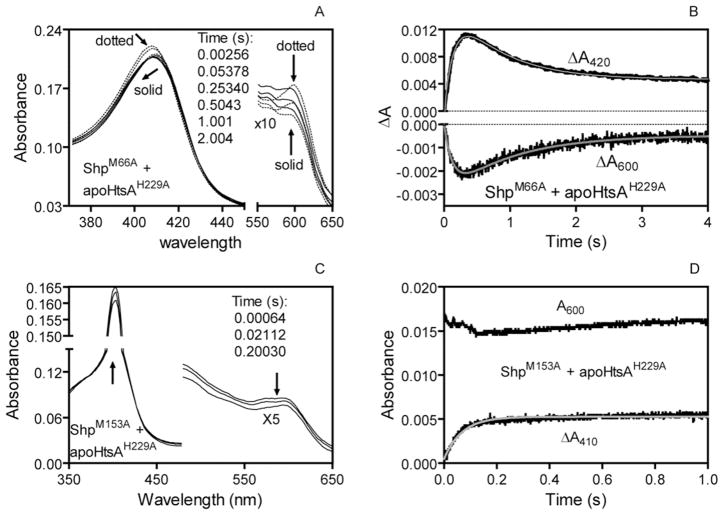

In the reactions of apoHtsAH229A with holoShpM66A and holoShpM153A, the donors and product all have a pentacoordinate heme iron with a Met axial ligand and have a charge transfer absorption peak at about 600 nm. During the reaction of holoShpM66A with apoHtsAH229A, the Soret peak first has a red shift and then a blue shift (Fig. 7A), and the A600 peak first decreases (the black curves) and then increases (the colored curves) (Fig. 7A). ΔA420 that represents the spectral shift in the Soret peak first increases and then decreases whereas ΔA600 that shows the spectral shift in the charge transfer band first decreases and then increases (Fig. 7B). The time course of both ΔA420 and ΔA600 at 13 μM of apoHtsAH229A fit to a two exponential equation, yielding two observed rate constants of 7.0 ± 1.0 s−1 and 1.4 ± 0.5 s−1. Clearly, the holoShpM66A/apoHtsAH229A reaction has an intermediate. The Soret peak of this intermediate is at a longer wavelength than holoShpM66A and holoHtsAH229A, and the intermediate lacks the A600 peak. These features suggest that the intermediate in the holoShpM66A/apoHtsAH229A reaction is a hexacoordinate heme iron complex. These results suggest that the holoShpM66A/apoHtsAH229A reaction follows the reaction scheme shown in Fig. 5D, in which the Met79 residue of apoHtsAH229A first forms an axial bond with the heme iron prior to the cleavage of the Met153-Fe bond during the reaction.

Figure 7.

Transfer intermediate in ferric holoShpM66A/apoHtsAH229A reaction but not in holoShpM153A/apoHtsAH229A reaction. HoloShp mutant was mixed with apoHtsA mutant in 20 mM Tris-HCl in a stopped-flow spectrophotometer. The arrows indicate the direction of the spectral shift with time. A, spectral shift in the reaction of 1.2 μM holoShpM66A with 13 μM apoHtsAH2299A. The black and colored curves are in the initial fast and subsequent slow phases, respectively. B, time course of ΔA420 and ΔA600 for the reaction in panel A. The black traces and gray curves represent the observed data and double exponential fitting curves, respectively. C, spectral shift in the reaction of 0.9 μM holoShpM153A with 13 μM apoHtsAH2299A. D, time course of ΔA410 and ΔA600 for the reaction in panel C. The black traces represent the observed data, and the gray curve of ΔA410 is the single exponential fitting curve.

In contrast, there is no significant change in A600 during the reaction of holoShpM153A with apoHtsAH229A (Fig. 7C & 7D), and the Soret peak increased with time (Fig. 7C). The time course of ΔA410 fits to a single exponential equation (Fig. 4D), yielding an observed rate constant of 14.7 ± 0.3 s−1 at 13 μM apoHtsAH229A. Thus, the holoShpM153A/apoHtsAH229A reaction has one kinetic phase, indicating that there is no spectrally detectable intermediate in this reaction. This spectral and kinetic data can be interpreted by the scheme shown in Fig. 6C, in which the HtsA M79 residue displaces the Shp M66 residue. The results in the reactions of apoHtsAH229A with ShpM66A and ShpM153A support a mechanism of the specific axial residue displacement shown in Fig. 6A in which the Met66 and Met153 residues of Shp are specifically displaced by the Met79 and His229 residues of apoHtsA, respectively, during the reaction.

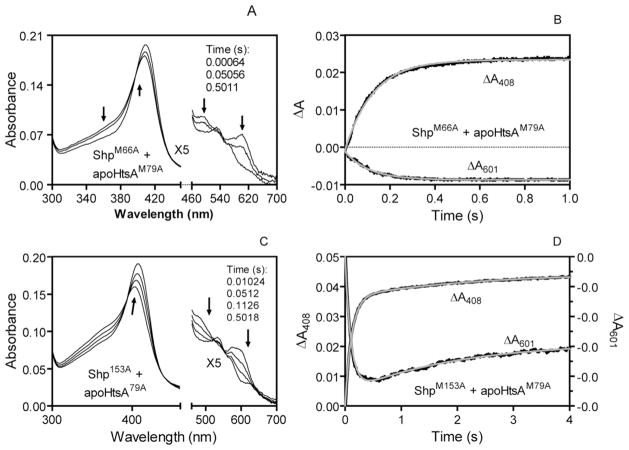

This axial displacement model was further tested in the reactions of apoHtsAM79A with holo-ShpM66A and holo-ShpM153A. If this model is correct, the holoShpM66A/apoHtsAM79A reaction should follow the scheme shown in Fig. 6C and have one kinetic phase whereas the ShpM153A/apoHtsAM79A reactions should have follow the scheme shown in Fig. 6D and have two kinetic phases. In both reactions, the spectra shifted to that of holoHtsAM79A (Fig. 8A & 8C). The spectral change in the holoShpM66A/apoHtsAM79A reaction indeed fits to a single exponential equation with an observed rate constant of 8.6 ± 0.6 s−1 with 10 μM apoHtsAM79A (Fig. 8B), indicating one kinetic phase of the reaction, whereas the spectral change in the holoShpM153A/apoHtsAM79A reaction fits to a two exponential equation with observed rate constants of 8.1 ± 0.4 s−1 and 0.48 ± 0.06 s−1 with 10 μM of apoHtsAM79A. These results further support the specific displacement of the axial ligands of the heme iron during the Shp-to-HtsA heme transfer reaction as proposed in Fig. 5A.

FIGURE 8.

Different kinetic phases of the heme transfer reactions of apoHtsAM79A with ferric holoShpM66A and holoShpM153A. HoloShp mutant (0.9 μM) was mixed with 10 μM apoHtsA mutant in 20 mM Tris-HCl in a stopped-flow spectrophotometer. The arrows indicate the orientation of the spectral shift with time. A, spectral shift in the reaction of holoShpM66A with apoHtsAM79A. B, single-phase time course of ΔA418 and ΔA600 for the reaction in panel A. The black traces and gray curves represent the observed data and single exponential fitting curves, respectively. C, spectral shift in the reaction of holoShpM153A with apoHtsAM79A. D, kinetically biphasic time course of ΔA408 and ΔA601 for the reaction in panel C. The black traces and gray curves represent the observed data and double exponential fitting curves, respectively.

Juxtaposition of the Shp and HtsA Heme-Binding Sites in Structural Modeling and Docking

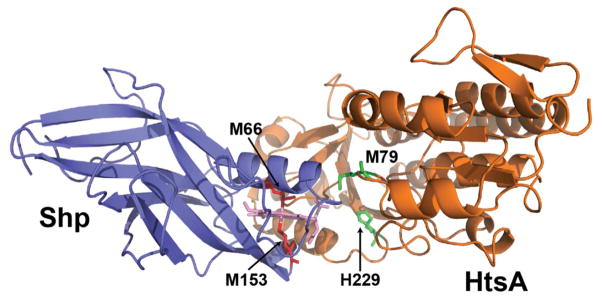

To further examine the mechanism of the specific axial displacement in the Shp/HtsA reaction shown in Fig. 6A, we used structural modeling and docking to examine whether the heme-binding pocket in Shp and HtsA can be juxtaposed in a way that is consistent with the model in Fig. 6A. The X-ray crystal structure of the heme-binding domain of Shp is available (13) but the structure of HtsA is not. We first generated a 3-D homology model of apo-HtsA using the Modeller program (30, 31), which is very similar to the structure of IsdE (33), a homologue of HtsA. The apoHtsA model was then docked to the structure of the heme-binding domain of Shp (PDBID: 2Q7A) using the online RosettaDock server (32). Although many possible protein orientations were obtained from the docking exercise, in many of the low-energy complexes the proteins were orientated as shown in Fig. 9. Thus, the docking analysis results are compatible with axial displacement heme transfer mechanism we have formulated in which HtsA His229-for-Shp M153 and HtsA M79-for-Shp M66 displacements occur.

FIGURE 9.

A docking complex with the juxtaposed heme pockets of Shp and lowest energy. Structure elements: Blue, Shp protein; orange, HtsA protein; light pink, heme; red, the M66 and M153 axial residues in Shp; and green, the M79 and H229 axial residues.

DISCUSSION

This study presents evidence for a novel mechanism of heme transfer from one protein to another. We first characterized the coordination and external ligand accessibility of the heme iron in the axial mutants of Shp for the interpretation of the spectral change and kinetics of heme transfer from the Shp axial ligand mutants to HtsA axial ligand mutants. We then revealed the roles of the axial residues of the HtsA heme iron in the efficiency and kinetic mechanism of the Shp-to-HtsA heme transfer. The H229 and M79 residues of HtsA are essential for the efficiency and single kinetic phase mechanism of the heme transfer from ferric Shp to HtsA, respectively. Finally, this study elucidated the mechanism of the specific displacement of the axial residues in the Shp/HtsA heme transfer reaction. The axial residues M66 and M153 of Shp are displaced by the axial residues M79 and H229 of HtsA, respectively, during the holoShp/apoHtsA reaction. These findings provide novel insight into the mechanism of direct heme transfer from one protein to another.

A novel advancement of this study is the elucidation of the specific displacement of the axial residues of Shp and HtsA during their reaction, that is, the Met66 and Met153 residues of Shp are specifically displaced by the Met79 and His229 residues of apoHtsA, respectively, during the heme transfer reaction. The spectral characterization on the coordination of the ShpM66A and ShpM153A heme iron together with that of HtsAM79A and HtsAH229A provide critical information for the interpretation of the heme transfer data using the Shp and HtsA mutants. The pentacoordinate heme iron of HtsAH229A has an absorption peak at ~ 600 nm (28), which is also observed in a H102M mutant of cytochrome b562 with an axial Met ligand (34). ShpM66A at basic pH and ShpM153 shows similar optical and MCD spectra with HtsAH229A, indicating the pentacoordination of the heme iron with the axial Met ligation in these mutants. Bonding to a water molecule at the empty sixth coordination site of ShpM66A abolishes the A600 peak. The A600 peak-related spectral changes in the holoShpM66A/apoHtsAH229A and holoShpM153A/apoHtsAH229A reactions are consistent with the interpretation that the Met79 residue of apoHtsAH229A forms the axial bond on the axial bond-lacking side of the pentacoordinate ShpM66A heme, resulting in a hexacoordinate complex in the holoShpM66A/apoHtsAH229A reaction and that the Met79 residue of apoHtsAH229A directly replaces the Met66 residue in the holoShpM153A/apoHtsAH229A reaction, lacking a hexacoordinate heme transfer intermediate. Thus, the HtsA Met79 residue replaces the Shp Met66 residue. The kinetic analysis of the heme transfer in the holoShpM66A/apoHtsAH229A and holoShpM153A/apoHtsAH229A reactions confirms this conclusion. Furthermore, the kinetic mechanisms of the reactions of apoHtsAM79A with holoShpM66A and holoShpM153A indicate that the His229 residue of HtsA forms the axial bond on the Met153 side of the Shp heme. The docking analysis supports the specific axial ligand displacement mechanism. These new data add more details to the “plug-in” model of the Shp/HtsA reaction, which was proposed to interpret the single kinetic phase of the Shp-to-HtsA heme transfer reaction (19). The updated model can be described in Fig. 6A in which the empty heme pocket of apoHtsA slides in along the two sides of the bound heme in Shp in the way so that the Met79 and His229 residues in apoHtsA are in close proximity of the Met66- and Met153-iron bonds in Shp, respectively, to displace the axial residues of Shp at about same time and pull it into the heme binding pocket of HtsA.

According to this specific displacement of the axial ligands of the Shp heme iron by the axial ligands of heme in HtsA, the rate constants for the cleavage rates of the Shp Met66-Fe bond in the reactions of apoHtsAM79A with holoShp and holoShpM153A were only about 5% of the cleavage of the Met66-Fe bond in the presence of the Met79 residue in the holoShpM153A/apoHtsAH229A reaction. The rate constant of the cleavage of the Met153-Fe bond in the presence of the His229 residue in the ShpM66A/apoHtsAM79A reaction was four times as that of the Met153-Fe bond cleavage in the absence of the His229 residue in the holoShpM66A/apoHtsAH229A reaction. Thus, the axial ligand residues of the heme acceptor apoHtsA facilitate the cleavage of the axial bonds in holoShp. The two kinetic phases of the holoShp/apoHtsAM79A further support the role of the axial residues of the HtsA heme iron in the cleavage of the axial bonds of heme in Shp. In this reaction, the cleavage of the Met153-Fe bond in Shp is facilitated by the HtsA His229 residue, whereas the cleavage of the other axial bond in Shp is slower because Met79 is absent. Thus, the axial residues of HtsA are actively involved in the specific displacement of the axial residues of the Shp heme iron. This work may help explain how the other NEAT-containing protein-to-lipoprotein transfer reactions occur as well.

How heme is transferred from one protein to another is not fully understood. Structural studies reveal a transient IsdA/IsdC (35), IsdC/IsdE (36), and stable HasA/HasR (37) complex, and the heme pockets of the donor and acceptor in both the reactions are juxtaposed. A docking analysis of the HasA/HasR interaction suggests that the interaction causes one of the 2 axial heme coordinations of HasA to break, and a subsequent steric displacement of heme by a receptor residue ruptures the other axial coordination (37). Kinetic analyses of the Shp/HtsA and IsdA/IsdC reactions indicate the existence of an activated donor-acceptor complex (19, 21). These studies support a direct heme transfer mechanism. Pilpa et al. proposed a release and capture mechanism for heme transfer from metHb to IsdH or IsdB in which donor/acceptor interaction enhances heme release from the donor and released heme is then scavenged by the acceptor (17). This release/capture mechanism may be true for the metHb/IsdH reaction (38). Our work provides further insight into the heme transfer mechanisms. First, the two axial ligands in the heme acceptor specifically displace the axial ligands in the donor. Second, the accepting axial ligands play a role in facilitating the cleavage of the axial bond in the donor. This specific displacement of axial ligands may occur in other heme acquisition systems. The heme iron in both IsdA and IsdC has a pentacoordination with a Tyr ligation, and the IsdA-to-IsdC heme transfer displays a single kinetic phase (21), suggesting that the axial Tyr residue in IsdC displaces the axial Tyr residue in IsdA.

It is known that the axial ligands of the heme iron in HasA, HasR, ShuA, and Porphyromonas gingivalis heme receptor HmuR are critical for heme transfer and acquisition (1, 2, 39–42). However, it is unclear why these axial ligands are required for heme acquisition. The earlier discussion suggests an active role of the axial residues in heme acceptor in reaction of the heme transfer. The inability of HtsAH229A to acquire heme from ferric Shp indicates another role of the axial ligands of heme recipient in driving the reaction equilibrium to the formation of the transfer product. The H229A replacement of HtsA reduced the affinity of HtsA for heme (28). The reduction in the heme affinity of HtsAH229A mutant could be a primary reason why HtsAH229A cannot efficiently acquire heme from ferric Shp. This interpretation is supported by the observations that the M79A replacement did not dramatically affect the heme affinity of HtsA (28) and that HtsAM79A can efficiently take up heme from ferric Shp. Thus, the axial ligand of heme acceptor can drive the equilibrium of the transfer reaction by enhancing the heme affinity of acceptor.

It is interesting that only one axial ligand is critical for the affinity of HtsA for heme. This phenomenon is not limited to HtsA. The axial ligand residue of Shp, Met153, is critical for the high affinity of Shp for heme, whereas the other axial ligand residue, Met66, destabilizes heme binding (20). These observations are consistent with the fact that S. aureus IsdA, IsdC, and IsdH and B. anthracis IsdX2 contain a pentacoordinate heme with tyrosine as the only axial ligand (12, 14, 15, 16, 43). Therefore, it appears that only one axial ligand of the heme iron is critical for high affinity of hemoproteins for heme.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH Grants AI095704 (BL), AI097703 (BL) and AI52217 (RTC) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and GM103500-09 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, USDA formula fund, and the Montana State University Agricultural Experimental Station.

Abbreviations

- Shp

surface heme-binding protein

- HtsA

lipoprotein component of the heme-specific ATP-binding cassette transporter

- ShpM66A and ShpM153A

Shp mutants carrying alanine replacement of the axial Met66 and Met153 residues, respectively

- HtsAM79A and HtsAH229A

HtsA mutants carrying alanine replacement of the axial Met79 and His229 residues, respectively

References

- 1.Izadi-Pruneyre N, Huche F, Lukat-Rodgers GS, Lecroisey A, Gilli R, Rodgers KR, Wandersman C, Delepelaire P. The heme transfer from the soluble HasA hemophore to its membrane-bound receptor HasR is driven by protein-protein interaction from a high to a lower affinity binding site. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25541–25550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603698200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burkhard KA, Wilks A. Characterization of the outer membrane receptor ShuA from the heme uptake system of Shigella dysenteriae. Substrate specificity and identification of the heme protein ligands. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15126–15136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabian M, Solomaha E, Olson JS, Maresso AW. Heme transfer to the bacterial cell envelope occurs via a secreted hemophore in the Gram-positive pathogen Bacillus anthracis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32138–32146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres VJ, Pishchany G, Humayun M, Schneewind O, Skaar EP. Staphylococcus aureus IsdB is a hemoglobin receptor required for heme iron utilization. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:8421–8429. doi: 10.1128/JB.01335-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu C, Xie G, Liu M, Zhu H, Lei B. Direct heme transfer reactions in the Group A Streptococcus heme acquisition pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazmanian SK, Skaar EP, Gaspar AH, Humayun M, Gornicki P, Jelenska J, Joachmiak A, Missiakas DM, Schneewind O. Passage of heme-iron across the envelope of Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 2003;299:906–909. doi: 10.1126/science.1081147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu M, Lei B. Heme transfer from streptococcal cell surface protein Shp to HtsA of transporter HtsABC. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5086–5092. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.5086-5092.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drazek ES, Hammack CA, Schmitt MP. Corynebacterium diphtheriae genes required for acquisition of iron from haemin and haemoglobin are homologous to ABC haemin transporters. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:68–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu H, Xie G, Liu M, Olson JS, Fabian M, Dooley DM, Lei B. Pathway for heme uptake from human methemoglobin by the iron-regulated surface determinants system of Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18450–18460. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801466200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muryoi N, Tiedemann MT, Pluym M, Cheung J, Heinrichs DE, Stillman MJ. Demonstration of the iron-regulated surface determinant (Isd) heme transfer pathway in Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28125–28136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802171200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiedemann MT, Heinrichs DE, Stillman MJ. Multiprotein heme shuttle pathway in Staphylococcus aureus: iron-regulated surface determinant cog-wheel kinetics. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:16578–16585. doi: 10.1021/ja305115y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muryoi N, Tiedemann MT, Pluym M, Cheung J, Heinrichs DE, Stillman MJ. Crystal structure of the heme-IsdC complex, the central conduit of the Isd iron/heme uptake system in Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28125–28136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802171200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aranda R, IV, Worley CE, Liu M, Bitto E, Cates MS, Olson JS, Lei B, Phillips GN., Jr Bis-methionyl coordination in the crystal structure of the heme-binding domain of the streptococcal cell surface protein Shp. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:374–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilpa RM, Fadeev EA, Villareal VA, Wong ML, Phillips M, Clubb RT. Solution structure of the NEAT (NEAr Transporter) domain from IsdH/HarA: the human hemoglobin receptor in Staphylococcus aureus. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:435–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grigg JC, Vermeiren CL, Heinrichs DE, Murphy ME. Haem recognition by a Staphylococcus aureus NEAT domain. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:139–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharp KH, Schneider S, Cockayne A, Paoli M. Crystal structure of the heme-IsdC complex, the central conduit of the Isd iron/heme uptake system in Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10625–10631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pilpa RM, Robson SA, Villareal VA, Wong ML, Phillips M, Clubb RT. Functionally distinct NEAT (NEAr Transporter) domains within the Staphylococcus aureus IsdH/HarA protein extract heme from methemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1166–1176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806007200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villareal VA, Pilpa RM, Robson SA, Fadeev EA, Clubb RT. The IsdC protein from Staphylococcus aureus uses a flexible binding pocket to capture heme. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31591–31600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801126200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nygaard TK, Blouin GC, Liu M, Fukumura M, Olson JS, Fabian M, Dooley DM, Lei B. The mechanism of direct heme transfer from the streptococcal cell surface protein Shp to HtsA of the HtsABC transporter. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20761–20771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601832200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ran Y, Zhu H, Liu M, Fabian M, Olson JS, Aranda R, Phillips GN, Jr, Dooley DM, Lei B. Bis-methionine ligation to heme iron in the streptococcal cell surface protein Shp facilitates rapid hemin transfer to HtsA of the HtsABC transporter. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31380–31388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705967200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu M, Tanaka WN, Zhu H, Xie G, Dooley DM, Lei B. Direct hemin transfer from IsdA to IsdC in the iron-regulated surface determinant (Isd) heme acquisition system of Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6668–6676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708372200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lei B. Benfang Lei’s research on heme acquisition in Gram-positive pathogens and bacterial pathogenesis. World J Biol Chem. 2010;1:286–290. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v1.i9.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lei B, Smoot LM, Menning HM, Voyich JM, Kala SV, Deleo FR, Reid SD, Musser JM. Identification and characterization of a novel heme-associated cell surface protein made by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4494–4500. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4494-4500.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lei B, Liu M, Voyich JM, Prater CI, Kala SV, DeLeo FR, Musser JM. Identification and characterization of HtsA, a second heme-binding protein made by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5962–5969. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5962-5969.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bates CS, Montanez GE, Woods CR, Vincent RM, Eichenbaum Z. Identification and characterization of a Streptococcus pyogenes operon involved in binding of hemoproteins and acquisition of iron. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1042–1055. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1042-1055.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu H, Liu M, Lei B. The surface protein Shr of Streptococcus pyogenes binds heme and transfers it to the streptococcal heme-binding protein Shp. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fabian M, Solomaha E, Olson JS, Maresso AW. Heme transfer to the bacterial cell envelope occurs via a secreted hemophore in the Gram-positive pathogen Bacillus anthracis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32138–32146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ran Y, Liu M, Zhu H, Nygaard TK, Brown DE, Fabian M, Dooley DM, Lei B. Spectroscopic identification of heme axial ligands in HtsA that are involved in heme acquisition by Streptococcus pyogenes. Biochemistry. 2010;49:2834–2842. doi: 10.1021/bi901987h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuhrhop JH, Smith KM. In: Porphyrins and Metalloporphyrins. Smith KM, editor. Elsevier Publishing; New York: 1975. pp. 804–807. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eswar N, Eramian D, Webb B, Shen MY, Sali A. Protein structure modeling with MODELLER. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;426:145–159. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eswar N, Webb B, Marti-Renom MA, Madhusudhan MS, Eramian D, Shen MY, Pieper U, Sali A. Comparative Protein Structure Modeling Using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2007;50:2.9.1–2.9.31. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps0209s50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyskov S, Gray JJ. The RosettaDock server for local protein-protein docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(suppl 2):W233–W238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grigg JC, Vermeiren CL, Heinrichs DE, Murphy ME. Heme coordination by Staphylococcus aureus IsdE. J Biol Chem 2007. 2007;282:28815–28822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704602200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barker PD, Nerou EP, Cheesman MR, Thomson AJ, de Oliveira P, Hill HA. Bis-methionine ligation to heme iron in mutants of cytochrome b562.1 Spectroscopic and electrochemical characterization of the electronic properties. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13618–13626. doi: 10.1021/bi961127x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villareal VA, Spirig T, Robson SA, Liu M, Lei B, Clubb RT. Transient weak protein-protein complexes transfer heme across the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:14176–14179. doi: 10.1021/ja203805b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abe R, Caaveiro JM, Kozuka-Hata H, Oyama M, Tsumoto K. Mapping ultra-weak protein-protein interactions between heme transporters of Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:16477–16487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.346700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krieg S, Huche F, Diederichs K, Izadi-Pruneyre N, Lecroisey A, Wandersman C, Delepelaire P, Welte W. Heme uptake across the outer membrane as revealed by crystal structures of the receptor–hemophore complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1045–1050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809406106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spirig T, Malmirchegini GR, Zhang J, Robson SA, Sjodt M, Liu M, Krishna Kumar K, Dickson CF, Gell DA, Lei B, Loo JA, Clubb RT. Staphylococcus aureus uses a novel multidomain receptor to break apart human hemoglobin and steal its heme. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:1065–1078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.419119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cobessi D, Meksem A, Brillet K. Structure of the heme/hemoglobin outer membrane receptor ShuA from Shigella dysenteriae: heme binding by an induced fit mechanism. Proteins. 2010;78:286–294. doi: 10.1002/prot.22539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olczak T. Analysis of conserved glutamate residues in Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane receptor HmuR: toward a further understanding of heme uptake. Arch Microbiol. 2006;186:393–402. doi: 10.1007/s00203-006-0151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X, Olczak T, Guo HC, Dixon DW, Genco CA. Identification of amino acid residues involved in heme binding and hemoprotein utilization in the Porphyromonas gingivalis heme receptor HmuR. Infect Immun. 2006;74:1222–1232. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1222-1232.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caillet-Saguy C, Piccioli M, Turano P, Izadi-Pruneyre N, Delepierre M, Bertini I, Lecroisey A. Mapping the interaction between the hemophore HasA and its outer membrane receptor HasR using CRINEPT-TROSY NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1736–1744. doi: 10.1021/ja804783x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Honsa ES, Owens CP, Goulding CW, Maresso AW. The near-iron transporter (NEAT) domains of the anthrax hemophore IsdX2 require a critical glutamine to extract heme from methemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:8479–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.430009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]