Abstract

We have investigated intrachain contact dynamics in unfolded cytochrome cb562 by monitoring heme quenching of excited ruthenium photosensitizers covalently bound to residues along the polypeptide. Intrachain diffusion for chemically denatured proteins proceeds on the microsecond timescale with an upper limit of 0.1 μs. The rate constants exhibit a power-law dependence on the number of peptide bonds between the heme and Ru complex. The power-law exponent of −1.5 is consistent with theoretical models for freely jointed Gaussian chains, but its magnitude is smaller than that reported for several synthetic polypeptides. Contact formation within a stable loop was examined in a His63-heme ligated form of the protein under denaturing conditions. Loop formation accelerated contact kinetics for the Ru66 labeling site, owing to reduction in the length of the peptide separating redox sites. For other labeling sites within the stable loop, quenching rates were modestly reduced compared to the open chain polymer.

Keywords: intrachain diffusion, protein folding, contact quenching

INTRODUCTION

The structure and dynamics of the denatured state ensemble play a critical role in protein folding. As formation of tertiary contacts is a necessary step in folding, the speed limit is set by the conformational dynamics in the unfolded state.1-2 Theoretical polymer models are commonly used to describe the properties of unfolded proteins. The simplest model, a freely jointed chain, predicts that the probability distribution of distances between the ends of the polymer is Gaussian and that the mean squared end-to-end distance is proportional to the number of links in the chain.3 The energy landscape for this type of system would be relatively flat, since all conformations are equally probable. These models are helpful for predicting equilibrium properties of denatured proteins, although ideal Gaussian distance distributions are rarely observed.4,5

The conformational dynamics of random polymers are generally described by diffusional models. The approximate solution to the Smoluchowski equation developed by Szabo, Schulten, and Schulten (SSS) for Gaussian chains predicts that end-to-end contact times in polymers depend on the mean squared distance between the polymer ends and the intrachain diffusion coefficient.6,7 The model further predicts that contact rate constants will exhibit a power-law distance dependence on the number of peptide bonds between contacts (k ~ n−1.5). 6 A refinement that takes into account the loop size formation probability predicts a maximum rate at n = 10 with an n−3.2 dependence for larger loops and slower rates for small loops, owing to increased stiffness.7 Experimental studies of contact formation kinetics in unstructured polypeptides have found reasonable agreement with these theoretical models.8,9,10

Phototriggered electron transfer reactions are well suited to studies of contact dynamics in biopolymers. The steep distance dependence of electron transfer11 ensures that reactions occur at close contact between donor and acceptor within a precursor complex. Bimolecular electron transfer rate constants (kET) can be described by Eq. 1, where Keq is the equilibrium constant for

| (1) |

precursor complex formation, ket is the rate constant for electron transfer within the precursor complex, and kD+ is the rate constant for diffusive formation of the precursor complex.12 For driving-force optimized reactions, ket becomes very large and kD+ becomes rate limiting. At lower driving forces, kET contains contributions from both kD+ and Keqket.

In intrachain quenching experiments, kD+ depends on the mean squared distance between the redox sites and the diffusion coefficient, whereas Keqket depends only on the equilibrium probability of complex formation.12 In prior work, we employed electron transfer quenching to estimate kD+ in denatured cytochrome (cyt) c and α-synuclein.13,14,15 We have now extended our work on contact dynamics to include denatured cyt cb562, a variant of cyt b562 with a c-type heme linkage to the polypeptide.16 This protein belongs to an interesting family of four-helix bundle cytochromes that have nearly identical structures yet widely divergent folding pathways, creating an opportunity to probe the relationship between primary sequences and folding kinetics in proteins with similar topologies.4,16–22

In the present study, we have examined the kinetics of electron transfer reactions between photoexcited [Ru(bpy)2(IA-phen)]2+, covalently attached at various positions in the protein chain, and the ferriheme of denatured cyt cb562. Rates of intrachain diffusion in the denatured (guanidine hydrochloride, Gdn) protein were estimated from analysis of time-resolved luminescence measurements. We also have examined contact formation within a preformed loop of the denatured protein.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Protein Preparation

Seven variants of cyt cb562 were prepared, each with one solvent-exposed residue mutated to cysteine: K19C, K32C, K51C, D66C, K77C, K83C, and E92C. Plasmid construction, expression, and purification of cyt cb562 variants, described in detail in Supporting Information, were performed according to previously published procedures with minor alterations.

Photosensitizers were attached covalently to cysteine thiols in labeling reactions. For electron-transfer measurements, variants were labeled with [Ru(bpy)2(IA-phen)]2+ (IA-phen = 5-iodoacetamido-1,10-phenanthroline), synthesized as previously described.23 For trFET measurements, variants were labeled with a dansyl fluorophore (5-((((2iodoacetyl)amino)ethyl)amino) naphthalene-1-sulfonic acid, Invitrogen). The disulfide-reduced protein with 20 mM DTT was exchanged into pH 8.0 buffer on a HiPrep 26-10 desalting column. Five-fold excess of the labeling reagent was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and stirred with the Ar-deoxygenated protein for 3–4 h in the dark. The reaction was quenched with DTT, and the buffer was exchanged with 15 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5) using a HiPrep 26-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare). Labeled protein was separated from unlabeled protein on a Mono-S 10/10 GL column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 15 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5) or a Mono-Q 10/10 GL column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 10 mM Tris-hydrochloride buffer (pH 8.0) using a sodium chloride gradient. As the photosensitizers are light-sensitive, all labeled samples were stored in the dark.

Protein Characterization

Purity was verified by SDS-PAGE on a Pharmacia PhastSystem (Amersham Biosciences). The molecular mass of the expressed protein was confirmed by electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy (Caltech Protein/Peptide Microanalytical Laboratory). The purity, concentration, and heme environment of cyt cb562 samples were assessed by UV-visible spectroscopy using an Agilent 8453 diode array spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The extinction coefficient for oxidized cyt cb562 is 0.148 μM−1cm−1 at the maximum Soret absorbance (415 nm).16 To confirm the purity of each sample, an absorbance ratio (415 nm: 280 nm) of 5 or greater was verified. Circular dichroism (CD) data were collected in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7 using an Aviv 62ADS spectropolarimeter (Aviv Associates, Lakewood, NJ).

trFET Measurements

trFET experiments were carried out with 1 μM cyt cb562 in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4–5) or 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7) with varying Gdn concentrations ([Gdn] determined by refractive index measurements24). Samples were deoxygenated by 30 pump-backfill cycles with Ar gas. The dansyl-labeled proteins were excited at 355 nm with the third harmonic (10 ps, 0.5 mJ) from a regeneratively amplified (Continuum), mode-locked picosecond Nd:YAG laser (Vanguard 2000-HM532; Spectra-Physics). Luminescence was collected using a picosecond streak camera (C5680; Hamamatsu Photonics) in the photon-counting mode. A long-pass cutoff filter (>430 nm) selected dansyl fluorescence. The decay data were collected on short (5 ns) and long (50 ns) time scales and spliced together. The combined traces were compressed logarithmically before fitting (70 points per decade). The trFET kinetics data were fit in MATLAB (Mathworks) with a Tikhonov regularization fitting algorithm, as previously described.25 The probability distributions of rate constants, P(k), were converted to probability distributions of distance, rDA, using the Förster equation.26 The Förster critical length, r0, for the Dns-heme pair is 39 Å under both native and denaturing conditions.5

Nanosecond Luminescence Measurements

Ru-labeled cyt cb562 (1.5–6 μM) was denatured with 6 M Gdn in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4–5) or 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7). For bimolecular measurements, Ru(bpy)3Cl2 (1 μM) was combined with cyt cb562 (0–175 μM) in 6 M Gdn, 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4). Samples were deoxygenated by 30 pump-backfill cycles with argon. Measurements were performed at ambient temperature (~20°C).

Samples were excited at 480 nm with 10 ns laser pulses from an optical parametric oscillator, pumped by the third harmonic of a Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (Spectra-Physics Quanta-Ray). A long-pass cutoff filter (>600 nm) and monochromator selected Ru luminescence (630 nm). Transmitted light was detected by a photomultiplier, and the signal was amplified then digitized. Luminescence decays comprised of three hundred averaged laser shots were collected on 2 μs or 10 μs timescales, as appropriate. Data were fit to exponential functions using the Curve Fitting Tool in MATLAB (Mathworks).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structural Characterization of Ru-Modified Variants

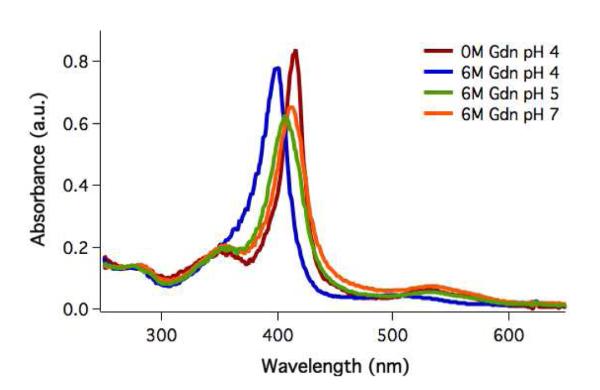

The heme environment of cyt cb562 was investigated using UV-visible spectroscopy (Figure 1). When the protein is folded, the heme is axially ligated to the sidechains of Met7 and His102 and has a Soret maximum of 415 nm. The ferric state of cyt cb562 is unfolded by Gdn with a denaturation midpoint of 4.2 M Gdn. When unfolded at pH 4, the Soret maximum blue shifts to 400 nm as the heme transitions from low spin to high spin, suggesting that the Met7 sulfur ligation is replaced by a water molecule.16 As the pH of the unfolded protein is increased, the Soret peak red shifts (λmax = 412 nm). The shift and pH range are consistent with heme ligation by a histidine imidazole. This observation suggests that in denatured cyt cb562, the nonnative histidine ligand (His63) coordinates to the heme at pH ≥ 5.

Figure 1.

UV-visible spectra of cyt cb562 K32C folded at pH 4 (λmax = 415 nm) and unfolded in 6 M Gdn at pH 4 (λmax = 400 nm), pH 5 (λmax = 406 nm), and pH 7 (λmax = 412 nm).

The heme Soret and CD (SI Figure 1) spectra of labeled proteins are virtually identical with those of the unlabeled wild-type, confirming that the mutations and Ru labeling do not disrupt the heme environment or protein secondary structure.

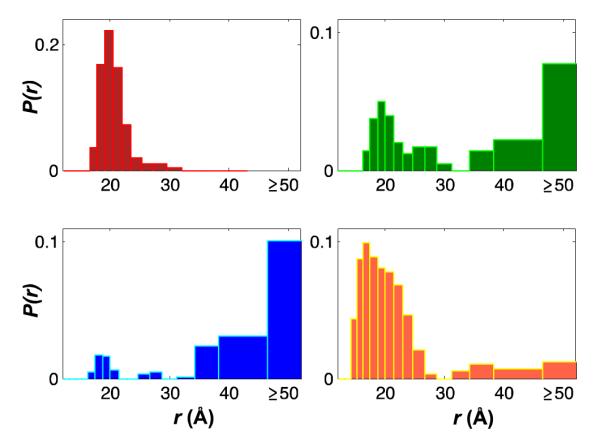

Conformational populations of cyt cb562 were determined by trFET measurements at variable Gdn concentrations and pH (SI Figure 2). Dansyl fluorophores (Dns) were attached at cysteine residues in place of Ru labels. Representative donor-acceptor distance distributions (rDA) for dansyl at D66C (Dns66) are shown in Figure 2. At 0 M Gdn, the dansyl-heme distances are consistent with those in the crystal structure of the folded wild-type protein (PDB 2BC5).16 The mean Dns66-heme distances extracted from the fluorescence decays are several angstroms longer than the Cγ-Fe distances in the crystal structure, likely owing to the length of the flexible linker between the Dns fluorophore and the Cγ atom.

Figure 2.

Conformational populations of cyt cb562 measured by trFET for a dansyl fluorophore donor at D66C and the heme acceptor: folded at pH 4 (red) and unfolded in 6 M Gdn at pH 4 (blue), pH 5 (green), and pH 7 (orange).

Extended conformations with >50-Å distances comprise a significant population of denatured Dns66 cyt cb562 (6 M Gdn). At pH 4, there are few compact states. With increasing pH, however, the proportion of the compact population increases, consistent with a decrease in the configurational freedom and the number of states available to the unfolded protein upon formation of a 36-residue loop by His63 ligation to the heme (Figure 6a).

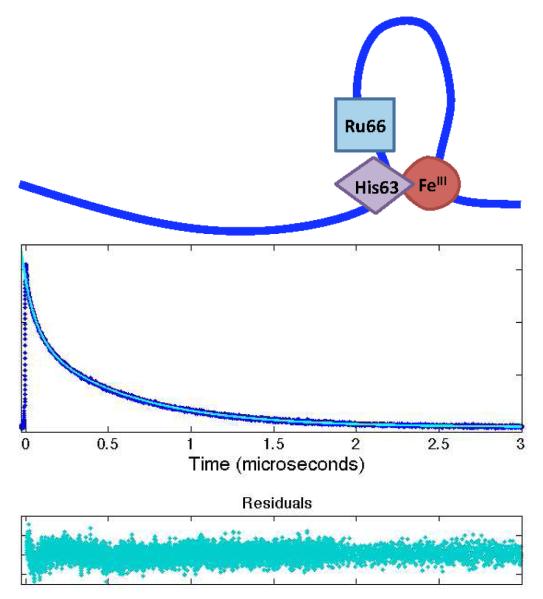

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic of long-lived loop formed by ferriheme misligation with deprotonated His63 at pH > 4. (b) Luminescence decay of Ru66 at pH 5. At pH 5, biexponential quenching by two distinct populations, the random coil and misligated forms, is observed.

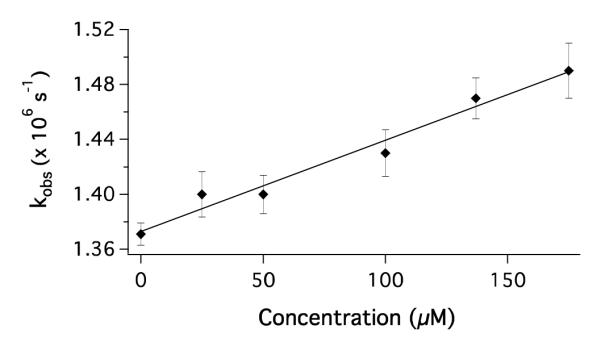

Contact Quenching

A ferriheme is expected to quench protein-bound *[Ru(bpy)2(IA-phen)]2+ via electron transfer (Scheme 1). We first examined bimolecular quenching of *Ru(bpy)32+ by varying the concentration of denatured cyt cb562 (6 M Gdn, Figure 3). The luminescence decay rate constants varied linearly with protein concentration, consistent with a second-order rate constant (kQ) of 6.6(±0.5) × 108 M−1s−1. Correcting for the viscosity of 6 M Gdn27 gives kQ = 1.2 × 109 M−1s−1, consistent with a reaction approaching diffusion control.

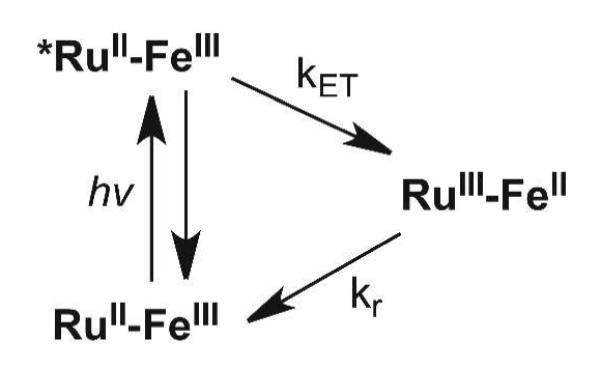

Scheme 1.

Luminescence of photoexcited RuII (*RuII) is quenched by electron transfer to the ferriheme.

Figure 3.

Stern-Volmer plot for the quenching of photoexcited Ru(bpy)32+ by cyt cb562 (Fe3+) in 6 M Gdn at pH 4. The solid line corresponds to a second-order rate constant kQ = 6.6(±0.5) × 108 M−1s−1.

Contact Formation Kinetics

We probed the formation of transient loops in the polypeptide chain of cyt cb562 by monitoring electron transfer between the heme and *[Ru(bpy)2(IA-phen)]2+ complexes attached at various positions on the polypeptide chain. The vinyl groups of the heme are covalently attached to the protein backbone of this 106-residue protein via two mutant cysteine residues, R98C and Y101C, in a CXXCH cyt c-type motif.16 Data were collected at pH 4 to inhibit His63 ligation of the heme and allow the denatured proteins a full range of motion. Following photoexcitation, *[Ru(bpy)2(IA-phen)]2+ luminesces with an unquenched lifetime of ~1 μs (klabel = 1.10(±0.04) × 106 s−1 at pH 4–7, [Gdn] = 6-8 M). Contact rate constants greater than ~105 s−1 are expected to produce measurable quenching. As the bimolecular quenching reaction is nearly diffusion-limited, we assume that the rate constants for contact formation are approximately equal to the electron-transfer rate constants in the labeled proteins (i.e., kD+ ≈ kET = kobs – klabel).

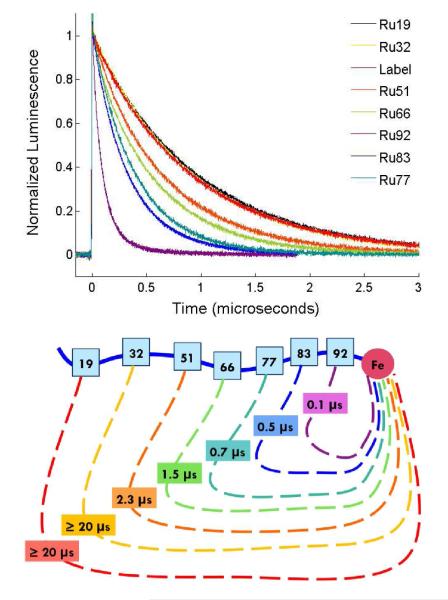

Luminescence decays for Ru-variants in 6 M Gdn and the corresponding kET−1 values are shown in Figure 4. The degree of quenching correlates with the efficiency of the electron-transfer reaction. The luminescence decays exhibit single-exponential kinetics, consistent with interconversion among protein conformations that is rapid compared to luminescence decay. Luminescence decay rate constants (kobs) for the variants range from 1.53(±0.03) × 106 s−1 for Ru51 to 9.4(±0.6) × 106 s−1 for Ru92 (SI Table 1). Luminescence from Ru19 and Ru32, the labeling sites with the greatest Ru-heme distances, is not measurably quenched. For these variants, electron transfer is not competitive with excited state deactivation, indicative of a contact time greater than 20 μs (the standard deviation for kET−1).

Figure 4.

(a) Luminescence decays of *RuII in the Ru-labeled protein variants and the unquenched free label at pH 4 in 6 M Gdn. (b) Schematic of the corresponding contact formation time constants, which show a distance dependence.

We find that electron-transfer rate constants (kET) depend on [Gdn], likely due to changes in viscosity as expected for a diffusion-limited process. For example, kET for Ru77 is 1.37(±0.07) × 106 s−1 at 6 M Gdn and 9.1(±0.5) × 105 s−1 at 8 M Gdn. A viscosity dependence also has been reported for intrachain diffusion in denatured cyt c and in Gly-Ser-repeat polypeptides.13,10 Prior work on end-to-end contact kinetics in Gly-Ser-repeat polypeptides found a linear dependence of ln(k) on [Gdn].28 If we assume similar behavior in cyt cb562, then our two data points are consistent with a slope of −Δln(k)/Δ[Gdn] = 0.2 M−1, comparable to the values extracted from Gly-Ser-repeat polypeptides (0.19–0.23 M−1).28 Extrapolating to 0 M Gdn solution suggests that the Ru77-heme contact rate constant would be 5 × 106 s−1 in buffer solution without Gdn. Applying the same extrapolation to our largest measured rate constant (Ru92, 107 s−1 in 6 M Gdn) leads to an estimated contact time of ~30 ns for the Ru92-labeled protein in buffer solution.

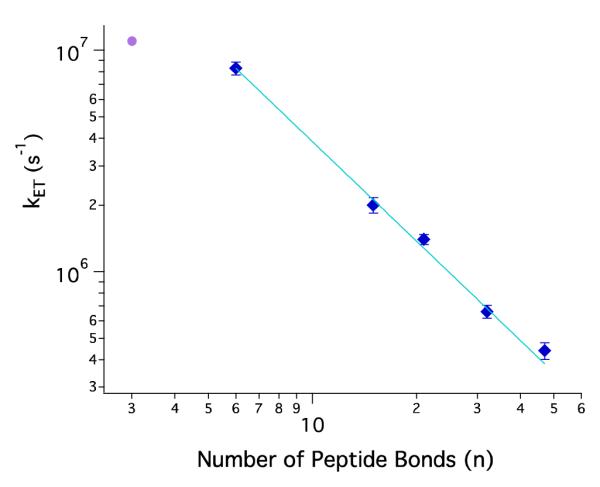

The quenching rate constants display a power-law dependence on n, the number of peptide bonds between the Ru label and the heme (Figure 5). A fit to the function kET = kony gives the following parameters: ko = 1.2(± 0.1) × 108 s−1 and y = −1.49 ± 0.04. This result is consistent with the SSS approximate solution of the Smoluchowski equation for end-to-end contact rate constants in Gaussian chains: kcontact ~ n−1.5.6 Contact formation in Cys-(Ala-Gly-Gln)J-Trp peptides exhibited a similar power-law dependence for n >10.9 In the presence of denaturant, the adherence to the power-law formula persisted for loops of just 4 peptide bonds, although with a somewhat steeper decay for the diffusion-limited rate (~n−2).12 End-to-end contact measurements with Gly-Ser-repeat polypeptides of variable length in water and 8 M Gdn exhibit power-law exponents of −1.7 and −1.8, respectively, consistent with models that take excluded-volume effects into account.10 Both the Cys-(Ala-Gly-Gln)J-Trp in buffer and Gly-Ser-repeat polypeptides in buffer and denaturant exhibited leveling of contact rate constants for small loops (n < 10). Interestingly, the power-law function describes the cyt cb562 quenching results for loop sizes as small as 7 peptide bonds.

Figure 5.

Log-log plot of contact formation rate constants versus number of peptide bonds between contacting residues (SI Table 1). Ru-variants are denatured in 6 M Gdn at pH 4 (blue diamonds). The solid line describes a power-law function with an exponent of −1.49 ± 0.04. Luminescence decay for Ru66 in 6 M Gdn at pH 7 fits to a biexponential function with an additional fast-reaction rate constant (purple circle).

The contact rate power-law exponent of −1.5 arises from the prediction that the mean squared distance between ends of a Gaussian chain polymer varies linearly with n.6,7 Chemically denatured proteins, however, are not necessarily described by this simple polymer model. Deviations from the power-law function would be expected for regions in which intrachain interactions slowed or impeded diffusion. Time-resolved fluorescence energy transfer studies indicate that a Gaussian chain model does a poor job of describing the distributions of donor-acceptor distances in chemically denatured cyt c.5 Moreover, freely jointed chain models of Trp-to-heme energy transfer in cyt c’, a protein in the same family as cyt cb562, require different persistence lengths for two sites in the protein.4 These observations suggest that neither denatured protein would be expected to exhibit a simple power-law dependence of contact rates.

Frustration in the protein folding energy landscape is an important determinant of folding kinetics.29,30 A smooth landscape with few kinetic traps leads to fast folding; a rough landscape with large energy barriers can slow folding and cause deviations from simple two-state behavior. The ruggedness of the energy landscape is reflected in the intrachain diffusion coefficient. Hagen, Hofrichter, and Eaton determined a value of 4–7 × 10−7 cm2 s−1 for this parameter in denatured cytochrome c (5.6 M Gdn).31 Using a similar analysis of our contact quenching data (Supporting Information),6,31 we estimate an average intrachain diffusion coefficient of 1.0(±0.1) × 10−6 cm2 s−1 for cyt cb562 in 6 M Gdn, a value that is smaller than expected for a free amino acid in water (~10−5 cm2 s−1) and marginally greater than that determined for cyt c.31 Contact rate constants10 and the corresponding diffusion coefficients for Gly-Ser-repeat polypeptides are substantially larger than for denatured cyt cb562. Contact formation for Ru77 (n=21) in 8 M Gdn is five times slower than for the repeat polypeptides in 8 M Gdn;10 these differences can be accounted for by the larger intrachain diffusion coefficients for the Gly-Ser repeat polypeptides (5.8 × 10−6 cm2 s−1 in 8 M Gdn).32,33

Dynamical drag34 introduced by segments of the polypeptide chain exterior to the loop also may contribute to the slower contact rates in the 106-residue protein.35 In synthetic polypeptides, interior-to-end contact rates decrease by as much as 2.5-fold compared to end-to-end contacts.36 In proteins, interior contact dynamics would be more affected by drag from the external protein chain than contacts toward the ends of the chain. This drag could contribute to the differences in the power-law dependence for interior loop formation in cyt cb562 (y = −1.5) compared to that found for end-to-end contact formation (y = −1.8) in synthetic peptides.

Dynamics within a Constrained Loop

At pH > 4, Ru66 quenching kinetics probe contact formation within a 36-residue loop formed by His63 misligation to the heme (Figure 6a). The UV-visible spectrum of cyt cb562 suggests that there is an increase in the degree of His63 heme misligation from pH 5 to 7 as the Soret band further red shifts (Figure 1), concurrent with an increase in the compact conformational population observed in Dns66 trFET measurements (Figure 2). As the pH is increased from 4 to 5, Ru66 cyt cb562 develops biexponential luminescence decay kinetics (Figure 6b), consistent with two populations that are not exchanging on the microsecond timescale (Table 1). It is likely, therefore, that the additional compact population is attributable to heme-misligated structures. The luminescence decay kinetics of labels at positions Ru77, Ru83, and Ru92 exhibit less significant changes as a consequence of stable loop formation (Table 1).

Table 1.

pH dependence of contact formation rate constants (s−1) for Ru-variants in 6 M Gdn.

| pH 4 | pH 5 | pH 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ru66 | 6.6 × 105 | 6 × 105 (60 %) 1 × 107 (40 %) |

3 × 105 (20 %) 1 × 107 (80 %) |

| Ru77 | 1.4 × 106 | Not measured | 1.4 × 106 |

| Ru83 | 2.0 × 106 | Not measured | 8.4 × 105 |

| Ru92 | 8.3 × 106 | 9 × 106 (60 %) 3 × 106 (40 %) |

5 × 106 (20%) 8 × 105 (80 %) |

For labeling sites within the 36-residue loop formed by misligation of His63 to the heme, Ru66- and Ru77-labeled proteins have smaller values of n (compared to their open-chain values), whereas the values for Ru83 and Ru92 remain unchanged. Ru66 contacts the heme more rapidly for misligated populations (kET ~ 107 s−1) than in the random coil (kET ~ 105.8 s−1), consistent with the reduction in n. Yet, the misligated Ru66 contact rate constant is smaller than expected for a loop comprised of three peptide bonds (Figure 5). In Ru77 cyt cb562, heme misligation should reduce n by about 8 peptide bonds, yet the expected increase in contact rate did not materialize. For Ru83 and Ru92, contact rates decrease somewhat from values obtained at pH 4.

Overall, contact rate constants for Ru labels in the interior of the static loop are smaller than expected when compared to the pH 4 data (Table 1). This reduction could be due to a stiffer polypeptide in the preformed loop and/or slower electron transfer, owing to a lower Fe3+/2+ formal potential in the bis-imidazole ligated heme. Steric effects may also be a factor; contact formation may be slowed due to decreased access to the heme when ligated by a histidine side chain instead of a water molecule.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The upper limit for the kinetics of a protein folding reaction will be governed by the rate at which intrachain contacts are formed.1,37 We measure a limiting time constant of 0.1 μs for cyt cb562 in 6 M Gdn, extrapolated to an estimated 30 ns in water. We observe a power-law dependence of contact formation rate constants on n, the length of the polypeptide chain between the contacts. Adherence of our data to a slope of −1.5 is consistent with predictions for a freely jointed Gaussian chain,6 but is a more gradual distance dependence than has been reported for several synthetic peptides.8–10 Formation of a stable loop via misligation of His63 to the heme substantially reduces n for Ru66, leading to a dramatic increase in contact rate. Overall, however, contact rates for residues within the stable loop are slower than for contacts in the open polypeptide chain at comparable values of n.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Lionel Cheruzel, Jeffrey Warren, Maraia Ener, and Katja Luxem for experimental assistance and helpful discussions. Our work was supported by NIH (Grants DK019038 and GM068461) and the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation.

ABBREVIATIONS

- Cyt

cytochrome

- trFET

time-resolved fluorescence energy transfer

- Gdn

guanidine hydrochloride

- CD

circular dichroism

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Detailed cyt cb562 protein expression and purification procedures, circular dichroism spectra, fluorescence decays from trFET measurements, rate constants for Ru-variants at pH 4, and diffusion coefficient calculations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Hagen SJ, Hofrichter J, Szabo A, Eaton WA. Diffusion-Limited Contact Formation in Unfolded Cytochrome c: Estimating the Maximum Rate of Protein Folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:11615–11617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Lapidus LJ. Exploring the Top of the Protein Folding Funnel by Experiment. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013;23:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Grosberg AY, Khokhlov AR. Statistical Physics of Macromolecules. AIP Press; Woodbury, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kimura T, Lee JC, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Site-Specific Collapse Dynamics Guide the Formation of the Cytochrome c’ Four-Helix Bundle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:117–122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609413103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Pletneva EV, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Many Faces of the Unfolded State: Conformational Heterogeneity in Denatured Yeast Cytochrome c. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;345:855–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Szabo A, Schulten K, Schulten Z. First Passage Time Approach to Diffusion Controlled Reactions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980;72:4350–4357. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Thirumalai D. Time Scales for the Formation of the Most Probable Tertiary Contacts in Proteins with Applications to Cytochrome c. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999;103:608–610. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lapidus LJ, Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. Measuring the Rate of Intramolecular Contact Formation in Polypeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:7220–7225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lapidus LJ, Steinbach PJ, Eaton WA, Szabo A, Hofrichter J. Effects of Chain Stiffness on the Dynamics of Loop Formation in Polypeptides. Appendix: Testing a 1-Dimensional Diffusion Model for Peptide Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2002;106:11628–11640. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Krieger F, Fierz B, Bieri O, Drewello M, Kiefhaber T. Dynamics of Unfolded Polypeptide Chains as Model for the Earliest Steps in Protein Folding. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;332:265–274. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00892-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Gray HB, Winkler JR. Long-Range Electron Transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:3534–3539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408029102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Buscaglia M, Lapidus LJ, Eaton WA, Hofrichter J. Effects of Denaturants on the Dynamics of Loop Formation in Polypeptides. Biophys. J. 2006;91:276–288. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.071167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Chang IJ, Lee JC, Winkler JR, Gray HB. The Protein/Folding Speed Limit: Intrachain Diffusion Times Set by Electron-Transfer Rates in Denatured Ru(NH3)5(His-33)-Zn-Cytochrome c. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:3838–3840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0637283100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Lee JC, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Tertiary Contact Formation in Alpha-Synuclein Probed by Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:16388–16389. doi: 10.1021/ja0561901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Lee JC, Lai BT, Kozak JJ, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Alpha-Synuclein Tertiary Contact Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:2107–2112. doi: 10.1021/jp068604y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Faraone-Mennella J, Tezcan FA, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Stability and Folding Kinetics of Structurally Characterized Cytochrome c-b562. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10504–10511. doi: 10.1021/bi060242x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wittung-Stafshede P, Lee JC, Winkler JR, Gray HB. Cytochrome b562 Folding Triggered by Electron Transfer: Approaching the Speed Limit for Formation of a Four-Helix-Bundle Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:6587–6590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lee JC, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Cytochrome c’ Folding Triggered by Electron Transfer: Fast and Slow Formation of Four-Helix Bundles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:7760–7764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141235198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lee JC, Engman KC, Tezcan FA, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Structural Features of Cytochrome c’ Folding Intermediates Revealed by Fluorescence Energy-Transfer Kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:14778–14782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192574099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Faraone-Mennella J, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Early Events in the Folding of Four-Helix-Bundle Heme Proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6315–6319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502301102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Pletneva EV, Zhao Z, Kimura T, Petrova KV, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Probing the Cytochrome c’ Folding Landscape. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2007;101:1768–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Kimura T, Lee JC, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Folding Energy Landscape of Cytochrome cb562. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:7834–7839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902562106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ener ME, Lee Y-T, Winkler JR, Gray HB, Cheruzel L. Photooxidation of Cytochrome P450-BM3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:18783–18786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012381107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Nozaki Y. The Preparation of Guanidine Hydrochloride. Methods Enzymol. 1972;26:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(72)26005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Yamada S, Bouley Ford ND, Keller GE, Ford WC, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Snapshots of a Protein Folding Intermediate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:1606–1610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221832110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Wu P, Brand L. Resonance Energy Transfer: Methods and Applications. Anal. Biochem. 1994;218:1–13. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Perl D, Jacob M, Bánó M, Stupák M, Antalik M, Schmid FX. Thermodynamics of a Diffusional Protein Folding Reaction. Biophys. Chem. 2002;96:173–190. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Möglich A, Krieger F, Kiefhaber T. Molecular Basis for the Effect of Urea and Guanidinium Chloride on the Dynamics of Unfolded Polypeptide Chains. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;345:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Bryngelson JD, Wolynes PG. Spin Glasses and the Statistical Mechanics of Protein Folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:7524–7528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Onuchic JN, Luthey-Schulten Z, Wolynes PG. Theory of Protein Folding: The Energy Landscape Perspective. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1997;48:545–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.48.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Hagen SJ, Hofrichter J, Eaton WA. Rate of Intrachain Diffusion of Unfolded Cytochrome c. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1997;101:2352–2365. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Möglich A, Joder K, Kiefhaber T. End-to-End Distance Distributions and Intrachain Diffusion Constants in Unfolded Polypeptide Chains Indicate Intramolecular Hydrogen Bond Formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12394–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604748103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Möglich A, Joder K, Kiefhaber T. Correction for Möglich et al., End-to-End Distance Distributions and Intrachain Diffusion Constants in Unfolded Polypeptide Chains Indicate Intramolecular Hydrogen Bond Formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604748103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Urie KG, Angulo D, Lee JC, Kozak JJ, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Synchronous vs Asynchronous Chain Motion in Alpha-Synuclein Contact Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:522–530. doi: 10.1021/jp806727e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Hyeon C, Thirumalai D. Kinetics of Interior Loop Formation in Semiflexible Chains. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;124:104905. doi: 10.1063/1.2178805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Fierz B, Kiefhaber T. End-to-End vs Interior Loop Formation Kinetics in Unfolded Polypeptide Chains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:672–679. doi: 10.1021/ja0666396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Kubelka J, Hofrichter J, Eaton WA. The Protein Folding “Speed Limit”. Curr. Opinion Struct. Biol. 2004;14:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.