Abstract

Freshwater snails in the family Bithyniidae are the first intermediate host for Southeast Asian liver fluke (Opisthorchis viverrini), the causative agent of opisthorchiasis. Unfortunately, the subtle morphological characters that differentiate species in this group are not easily discerned by non-specialists. This is a serious matter because the identification of bithyniid species is a fundamental prerequisite for better understanding of the epidemiology of this disease. Because DNA barcoding, the analysis of sequence diversity in the 5’ region of the mitochondrial COI gene, has shown strong performance in other taxonomic groups, we decided to test its capacity to resolve 10 species/ subspecies of bithyniids from Thailand. Our analysis of 217 specimens indicated that COI sequences delivered species-level identification for 9 of 10 currently recognized species. The mean intraspecific divergence of COI was 2.3% (range 0-9.2 %), whereas sequence divergences between congeneric species averaged 8.7% (range 0-22.2 %). Although our results indicate that DNA barcoding can differentiate species of these medically-important snails, we also detected evidence for the presence of one overlooked species and one possible case of synonymy.

Introduction

Molecular taxonomic methods have been used extensively to complement morphological approaches for species identification, and for establishing phylogenetic relationships [1-10]. Particularly, species identification through DNA barcoding has seen rapid adoption over the past decade. Prior DNA barcode studies have clearly established their effectiveness in the delimitation of animal species, and also contributed several advantages [11-13]. The ability of DNA barcoding to identify all life stages has particular importance in medical parasitology, where it is not only important to identify the parasite and its final host, but also all its life stages and its intermediate hosts. Thus, a multidisciplinary method of classification that includes morphological, molecular and distributional data is an essential prerequisite for understanding the epidemiology of any parasite-induced disease [7].

Freshwater snails of the family Bithyniidae serve as intermediate hosts for the liver fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini, and related species common in the Greater Mekong subregion (Cambodia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Vietnam, and Thailand). The infection of this parasite has been associated with several hepatobiliary diseases, including opisthorchiasis, cholangitis, obstructive jaundice, hepatomegaly, cholecystitis, and biliary lithiasis [14-18]. Furthermore, both experimental and epidemiological evidence suggest that liver fluke infections can be an etiological factor of cholangiocarcinoma [19-25]. Three taxa of Bithynia are involved in the transmission of this parasite [26-28] with different species reported as intermediate hosts in different parts of Thailand. B. siamensis goniomphalos is a dominant host in the northeast, while B. funiculata and B. siamensis siamensis serve as hosts in the north and B. siamensis siamensis in the central region [26,29]. Taxonomic keys for differentiation to species in the family Bithyniidae utilized size, shape, color, and sculpture on the shell surface, operculum structure, and shape and arrangement patterns of radular teeth. Because these characters often demonstrate both geographic variation and phenotypic plasticity, morphological characters used to separate species are difficult to score and identifications require expert malacologists [30]. DNA barcoding has effectively identified snail species in other settings [31-34], therefore we decided to test its effectiveness on Bithyniidae.

The present study is the first to explore the application of DNA barcoding in species identification in the family Bithyniidae. We analyzed variation of the COI barcode region within 10 species/subspecies of Bithyniidae using pairwise sequence comparisons. We then examined the effectiveness of DNA barcoding in differentiating among these species.

Materials and Methods

Snail collections and preparation

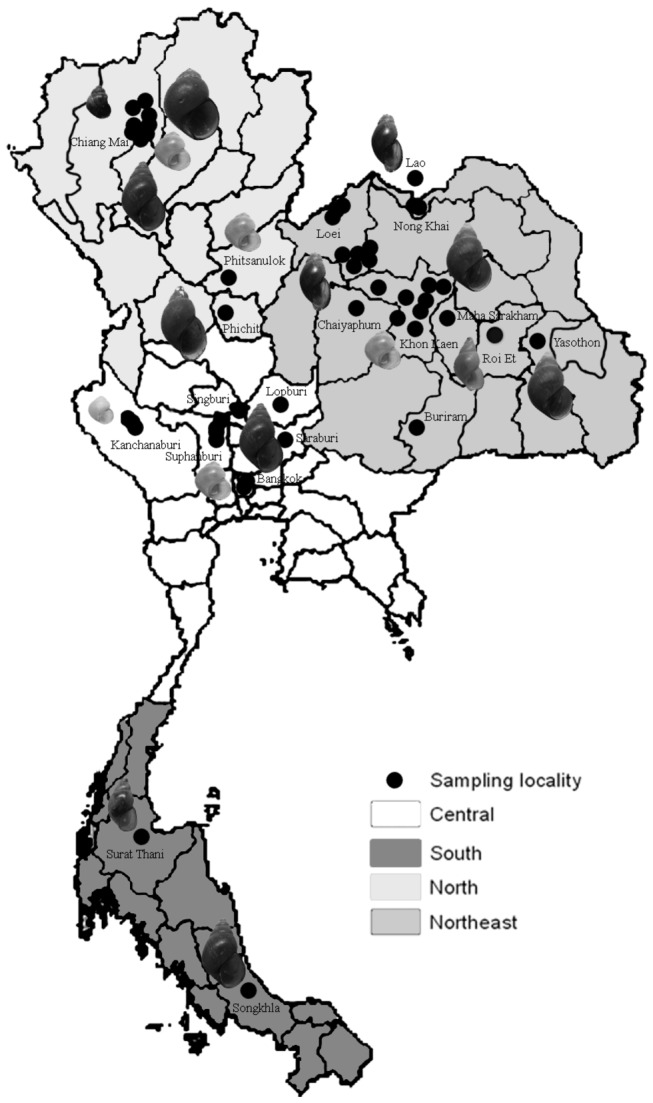

Adult snails of the family Bithyniidae (superfamily Rissoacea) were collected with wire-mesh scoops or by hand in 2009 and 2010 from four regions of Thailand: north, northeast, south, and central (Figure 1, Table 1). These regions were selected based on results from previous studies [26,28,35]. Each collection site was recorded and its GPS coordinates were determined using a Garmin®nuvi 203 (Garmin (Asia) Co.,Taiwan). The specimens for this study were collected mostly from public water reservoirs where no permits were required. Owners of the private localities (a rice paddy and a waterfall) were asked for their permission. The owners gave their verbal consent for samples to be collected. All species of those snails are not endangered or protected. The snails were sorted and identified following the protocols in Brandt [26], Chitramvong [36], and Upatham et al. [37]. In addition two subspecies (B. s. siamensis and B. s. goniomphalos) were categorized by geographic distribution.

Figure 1. Schematic map of Thailand showing collection localities.

Table 1. Collection sites for each species from Thailand.

| Species | Collection Date | Country | State/Province | Region* | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bithynia funiculata | 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | Mae Rim1 | 18.68280029 | 98.97660065 |

| (Walker, 1927) | 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | Mae Rim2 | 18.91769981 | 98.97409821 |

| 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | Saraphi3 | 18.68889999 | 98.9536972 | |

| 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | Mae Rim4 | 18.91139984 | 98.96800232 | |

| Bithynia siamensis | 13-Oct-2010 | Thailand | Nong Khai | Sangkhom5 | 18.09830093 | 102.2419968 |

| goniomphalos | 13-Oct-2010 | Thailand | Nong Khai | Tha Bo6 | 17.78840065 | 102.6009979 |

| (Morelet, 1866) | 04-Jun-2010 | Thailand | Roi Et | Muang Roi Et7 | 15.90060043 | 103.7320023 |

| 03-May-2008 | Thailand | Maha Sarakham | Barabue8 | 16.03829956 | 103.1190033 | |

| 11-May-2008 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Chum Phae9 | 16.54809952 | 102.0940018 | |

| 04-Apr-2008 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Ubolratana10 | 16.75279999 | 102.6330032 | |

| 10-May-2008 | Thailand | Nong Bua Lamphu | Non Sang11 | 16.86380005 | 102.5680008 | |

| 04-Apr-2008 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Ban Phai12 | 16.16609955 | 102.6829987 | |

| 04-Apr-2008 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Waeng Noi13 | 15.80589962 | 102.4110031 | |

| 09-Dec-2008 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Ubolratana14 | 16.75300026 | 102.6330032 | |

| 04-Apr-2008 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Ban Phai15 | 16.16609955 | 102.6829987 | |

| 10-May-2010 | Thailand | Buriram | Nong Ki16 | 14.66600037 | 102.5439987 | |

| 12-May-2008 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Muang Khon Kaen17 | 16.44829941 | 102.8499985 | |

| Bithynia siamensis siamensis | 26-Feb-2011 | Thailand | Songkhla | Hat Yai18 | 7.013070107 | 100.4520035 |

| (Morelet, 1866) | 10-Oct-2009 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Muang Khon Kaen19 | 16.44799995 | 102.8499985 |

| 10-May-2009 | Thailand | Bangkok | Kasertsat University20 | 13.85270023 | 100.5699997 | |

| 10-May-2009 | Thailand | Bangkok | Kasertsat University21 | 13.8494997 | 100.5680008 | |

| 08-May-2009 | Thailand | Phitsanulok | Bang Rakam22 | 16.67480087 | 100.1600037 | |

| 08-May-2009 | Thailand | Phichit | Bueng Na Rang23 | 16.17670059 | 100.1279984 | |

| 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | Muang Chiang Mai24 | 18.80529976 | 98.95020294 | |

| 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | Muang Chiang Mai25 | 18.79179955 | 98.94629669 | |

| 10-May-2009 | Thailand | Suphan Buri | Si Pranchan26 | 14.6697998 | 100.1159973 | |

| 10-Jun-2010 | Thailand | Lop Buri | Chai Badan27 | 15.20429993 | 101.137001 | |

| 26-Feb-2011 | Thailand | Songkhla | Hat Yai28 | 7.013070107 | 100.4520035 | |

| 10-May-2009 | Thailand | Sing Buri | Muang Sing Buri29 | 14.8604002 | 100.3939972 | |

| Species | Collection Date | Country | State/Province | Region* | Latitude | Longitude |

| Bithynia siamensis siamensis | 10-Jun-2010 | Thailand | Lop Buri | Patthana Nikhom30 | 14.85579967 | 100.9899979 |

| (Morelet, 1866) | ||||||

| Filopaludina | 10-Aug-2010 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Khon Kaen | 16.46800041 | 102.8310013 |

| martensi martensi | University31 | |||||

| Gabbia erawanensis | 11-May-2009 | Thailand | Kanchanaburi | Erawan32 | 14.36789989 | 99.14369965 |

| (Prayoonhong, Chitramvong& | 17-May-2009 | Thailand | Kanchanaburi | Erawan33 | 14.36800003 | 99.14399719 |

| Upatham 1990) | 11-May-2009 | Thailand | Kanchanaburi | Erawan34 | 14.3689003 | 99.145401 |

| Gabbia pygmaea | 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | Mae Rim35 | 18.91139984 | 98.96800232 |

| (Preston, 1908) | ||||||

| Gabbia wykoffi | 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | Saraphi36 | 18.68560028 | 99.04979706 |

| (Brandt 1968) | 04-Apr-2010 | Thailand | Loei | Chiang Khan37 | 17.90600014 | 101.6880035 |

| 04-Apr-2010 | Thailand | Loei | Chiang Khan38 | 17.89599991 | 101.6699982 | |

| 04-Apr-2010 | Thailand | Loei | Chiang Khan39 | 17.89489937 | 101.6709976 | |

| 12-Oct-2009 | Thailand | Saraburi | Muang Saraburi40 | 14.53129959 | 100.9260025 | |

| 10-May-2009 | Thailand | Suphan Buri | Muang Sing Buri41 | 14.85379982 | 100.3779984 | |

| 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | Saraphi42 | 18.68560028 | 99.04979706 | |

| 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | Hang Dong43 | 18.68889999 | 98.9536972 | |

| 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | Hang Dong44 | 18.68280029 | 98.97660065 | |

| 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Bangkok | Kasertsat University45 | 13.8494997 | 100.5680008 | |

| 20-Oct-2009 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Ubolratana46 | 16.75279999 | 102.6330032 | |

| 20-Oct-2009 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Muang Khon Kaen47 | 16.45019913 | 103.0270004 | |

| 10-Aug-2009 | Thailand | Chaiyaphum | Chatturat48 | 15.56820011 | 101.8430023 | |

| 10-May-2009 | Thailand | Bangkok | Kasertsat University49 | 13.8494997 | 100.5680008 | |

| 11-May-2009 | Thailand | Kanchanaburi | Erawan50 | 14.36789989 | 99.14369965 | |

| 20-Oct-2009 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Muang Khon Kaen51 | 16.45019913 | 103.0270004 | |

| 10-May-2010 | Thailand | Loei | Chiang Khan52 | 17.90600014 | 101.6880035 | |

| 10-May-2010 | Thailand | Loei | Chiang Khan53 | 17.8946991 | 101.6699982 | |

| 11-May-2008 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Ubolratana54 | 16.75279999 | 102.6330032 | |

| Species | Collection Date | Country | State/Province | Region* | Latitude | Longitude |

| Hydrobioides nassa | 18-Jan-2009 | Thailand | Sing Buri | Muang Sing Buri55 | 14.86400032 | 100.3960037 |

| (Theobald, 1865) | 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Lamphun | Muang Lamphun56 | 18.62989998 | 99.04989624 |

| 08-May-2009 | Thailand | Phichit | Bueng Na Rang57 | 16.17670059 | 100.1279984 | |

| 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | San Kamphaeng58 | 18.91139984 | 98.96800232 | |

| 10-May-2009 | Thailand | Sing Buri | Khai Bang Rachan59 | 14.80000019 | 100.3089981 | |

| 10-May-2009 | Thailand | Sing Buri | Muang Sing Buri60 | 14.91609955 | 100.3850021 | |

| 09-May-2009 | Thailand | Chiang Mai | San Kamphaeng61 | 18.76029968 | 99.07859802 | |

| Wattebledia baschi | 10-Oct-2010 | Thailand | Surat Thani | Phunphin62 | 9.11400032 | 99.23000336 |

| (Brandt 1968) | 10-Oct-2009 | Thailand | Surat Thani | Phunphin63 | 9.113780022 | 99.229599 |

| Wattebledia crosseana | 04-Apr-2010 | Thailand | Loei | Chiang Khan64 | 17.89599991 | 101.6699982 |

| (Wattebled 1886) | 04-Apr-2010 | Thailand | Loei | Chiang Khan65 | 17.89100075 | 101.6439972 |

| 04-Apr-2010 | Thailand | Loei | Pak Chom66 | 18.02479935 | 101.9000015 | |

| 10-May-2010 | Thailand | Loei | Chiang Khan67 | 18.08709908 | 101.9520035 | |

| 25-Dec-2008 | Thailand | Loei | Chiang Khan68 | 18.08699989 | 101.9520035 | |

| 11-May-2008 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Ubolratana69 | 16.75279999 | 102.6330032 | |

| 11-May-2008 | Thailand | Nong Bua Lamphu | Muang Nong Bua Lum | 17.24449921 | 102.5169983 | |

| Phu70 | ||||||

| 12-Feb-2009 | Laos | Vientiane | Pakse71 | 15.12049961 | 105.8130035 | |

| 04-Apr-2010 | Thailand | Loei | Chiang Khan72 | 17.89599991 | 101.6699982 | |

| 25-Dec-2008 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Ubolratana73 | 16.75279999 | 102.6330032 | |

| 10-May-2010 | Thailand | Nong Khai | Tha Bo74 | 17.78800011 | 102.6009979 | |

| Wattebledia siamensis | 20-Jan-2008 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Muang Khon | 16.4484005 | 102.8499985 |

| (Moellendorff, 1902) | Kaen75 | |||||

| 20-Jan-2008 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Ubolratana76 | 16.75279999 | 102.6330032 | |

| 20-Jan-2008 | Thailand | Khon Kaen | Muang Khon | 16.45319939 | 102.4530029 | |

| Kaen77 |

represent the collection sites in the map

Each snail was subsequently examined for trematode infections by testing for cercarial shedding twice within a week. Prior to cercarial shedding, the snails were cleaned with dechlorinated tap-water. Shedding was induced under 25 W electric light bulbs for 2 hours at room temperature during the day. For species that shed cercaria at night, black covers were used to achieve total darkness and snails were allowed to shed overnight. Uninfected snails were soaked in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing antibiotics (200 unit/ml of penicillin and 100 µg/ml of streptomycin) for 3 to 4 hours before extraction of DNA to ensure that bacterial contamination was minimized.

Each snail was dissected to remove its soft body parts, and kept at -20 °C until further analysis. Each specimen was labeled, databased and imaged. All specimen records are in the project ‘JUT- Mitochondrial DNA barcodes identification for snail in family Bithyniidae in Thailand’ on BOLD, the Barcode of Life Data Systems [38].

DNA extraction

Total genomic DNA was extracted from whole snail tissue using methods similar to those in Winnepenninckx et al. [39]. Snail tissue was first homogenized in lysis buffer (2% w/v Cetyltri-ammonium bromide; CTAB, 1.4 M NaCl, 0.2% v/v β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM EDTA, 100 mM TrisHCl pH 8, 0.2 mg/ml proteinase K), and then incubated at 55 °C for 6 hours. Subsequently, proteins were precipitated using phenol/chloroform (1:1) once, followed by phenol/ chloroform/ isoamylalcohol (25:24:1), centrifuged at 13,000 g for 10 min (4 °C) twice, and finally washed with chloroform (1:1). The upper aqueous layer was removed, and DNA was precipitated in isopropanol (2:3 v/v), mixed gently by inverting the tube a few times, put on ice for 15 min, and then spun in a microcentrifuge at 13,000 g for 5 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded; the DNA pellets were washed in 75% absolute ethanol, and centrifuged at 13,000 g for 5 min. After air-drying, the DNA pellet was re-suspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and stored at -20 °C until analysis. The DNA concentration and purity were estimated by spectrophotometer (NanoVue, GE Healthcare UK limited, Buckinghamshire, UK) at an absorbance of 260 and 280 nm wavelengths. The extracted genomic DNA was then diluted to a working concentration of 10 ng/µl.

Amplification and sequencing

PCR protocols followed those used by the Canadian Centre for DNA Barcoding [40], with slight modifications. The PCR reaction was performed on a GeneAmp® PCR System 9700 Thermo Cycler (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA). The partial mitochondrial COI gene was amplified using the primers shown in Table 2 [41,42] in a total reaction volume of 50 µl. The amplification reaction consisted of 10xPCR buffer for 5 µl, 10 mM dNTP for 0.25 µl, 50 mM MgCl2 for 2.5 µl, forward primer for 0.5 µl, reverse primer for 0.5 µl, Platinum Taq polymerase for 0.24 µl, H2O for 36.01 µl and template for 5 µl. Standard conditions for COI gene amplification included initial denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, five cycles of 94 °C for 30 sec, annealing at 45-50 °C for 40 sec, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, following by 30 to 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 sec, 51 to 54 °C for 40 sec, and 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min, followed by an indefinite hold at 4 °C [43-45]. PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel and the specific band was cut and its DNA purified and then sequenced in the Biochemistry Department, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University; Pacific Science Co. LTD (Bangkok, Thailand) and at the Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, Canada.

Table 2. Primers used for PCR amplification and sequencing [41,42].

| Primer name | Sequence | Forward or Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| LCO1490 | 5′ GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG 3′ | Forward |

| HCO2198 | 5′ TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA 3′ | Reverse |

| GasF1_t1 | 5′ TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTTTCAACAAACCATAARGATATTGG 3′ | Forward |

| GasF2_t1 | 5′ TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTATTCTACAAACCACAAAGACATCGG 3′ | Forward |

| GasF3_t1 | 5′ TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTTTCWACWAATCATAAAGATATTGG 3′ | Forward |

| GasR1_t1 | 5′ CAGGAAACAGCTATGACACTTCWGGRTGHCCRAARAATCARAA 3′ | Reverse |

| MGasF1_t1 | 5′ TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTATAAGATTTCCTCGWWTRAATAATA 3′ | Forward |

| MGasR1_t1 | 5′ CAGGAAACAGCTATGACTCCTGTWCCWRCWCCWCCTTC 3′ | Reverse |

Remark Degenerate base; R = A or G, W = A or T, H = C or A or T

Data analysis

Forward and reverse DNA sequences were assembled, and edited using Chromas version 2.23 [46], BioEdit v. 5.0.6 [47] and CodonCode v.3.01 (CodonCode Corporation, Dedham, MA). Alignment and homology analysis were performed using CLUSTAL X v. 1.8 [48] and MEGA 4 [49] with pairwise nucleotide sequence divergences calculated using the Kimura 2-parameter (K2P) model [50]. Base composition and distance summaries were obtained using the tools provided on the BOLD workbench (www.boldsystems.org) [38], but only sequences ≥ 350 bp were included in the analysis. A neighbour-joining (NJ) tree was also created using BOLD to provide a preliminary display of the sequence divergences.

Results and Discussion

Ten species/subspecies of Bithyniidae were collected from sites across Thailand (Figure 1 and Figure 2). A total of 217 individuals of these species/subspecies were analyzed for COI, and Neotricula aperta gamma strain (family Hydrobiidae, superfamily Rissoacea) from GenBank (Accession: AF AF188222.1 GI: 11493624 and AF188220.1 GI: 11493620) was used as outgroup. All 217 specimens were identified using morphological characteristics of the adult shells, radular patterns, geographic distribution [35-37], and confirmed by a malacologist. From 1-6 individuals of each species/subspecies from each of the five regions were analyzed, as shown in the neighbour-joining tree (Figure S1). The sequences, and trace files, are available on BOLD (project: JUT).

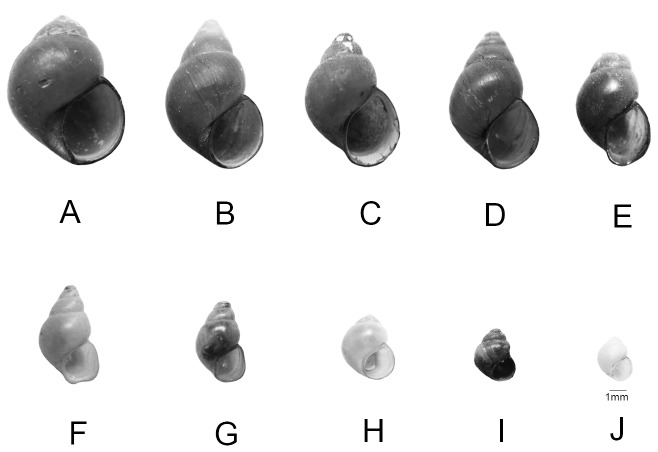

Figure 2. The shell morphology of bithyniid snails (A) B. funiculata; (B) B. siamensis goniomphalos; (C) B. siamensis siamensis; (D) H. nassa ; (E) W. crosseana; (F) W. siamensis; (G) W. baschi; (H) G. wykoffi; (I) G. pygmaea; (J) G. erawanensis.

Scale bars: A-J = 1 mm.

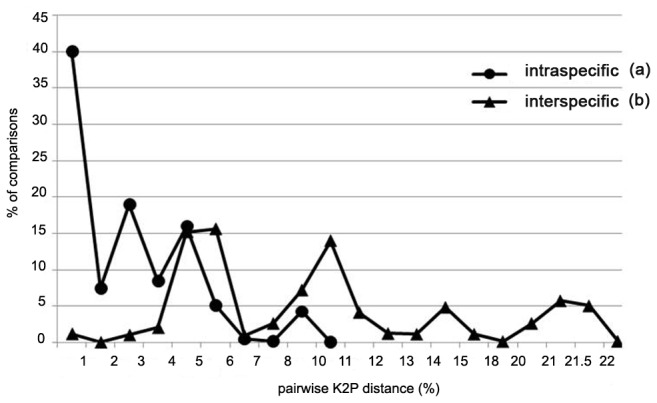

The pairwise sequence divergences were different among species/subspecies (Table S1). Intraspecific K2P distances averaged 2.3±0.001% (range 0-9.2 %), 4-fold less than the mean congeneric sequence divergence of 8.7±0.002% (range 0-22.2 %). The highest mean intraspecific sequence divergence for an individual species was 4.93±0.22% (range 0-9.2%) for Wattebledia crosseana reflecting the fact that members of this species fell into two distinct sequence clusters (Table 3). The mean sequence divergence across the family was also high, averaging 17.1% (range 13.0-21.3%).The distributions of intraspecific and interspecific divergences showed limited overlap (Figure 3), because most (65.4%) intraspecific sequences showed less than 2% divergence while 83.4% of the interspecific sequences possessed more than 3% divergence. As a result, sequence divergences for these snails are similar to those in previous barcoding reports on other organisms [2,12]. Hebert et al. [12] reported that COI sequence divergences among animal species from interspecific COI divergences within the phylum Mollusca averaged 11.1±5.1%.

Table 3. Species with nearest neighbour and intraspecific and interspecific divergence.

| Species | Nearest Neighbor (NN) | Intraspecific | Intraspecific | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Number of specimens) | ||||||||||||

| Nearest Neighbor | Distance to | Count | Mean | SE | Max | Min | Count | Mean | SE | Max | Min | |

| NN% | Comparisons | Comparisons | ||||||||||

| Bithynia funiculata (13) | B. siamensis siamensis | 7.11 | 78 | 1.08 | 0.10 | 2.17 | 0 | |||||

| B. siamensis goniomphalos (30) | B. siamensis siamensis | 1.49 | 435 | 2.39 | 0.04 | 3.95 | 0 | |||||

| B. siamensis siamensis (40) | B. siamensis goniomphalos | 1.49 | 780 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 1.81 | 0 | 2110 | 2.27 | 0.13 | 10.77 | 0 |

| Wattebledia crosseana (26) | W. baschi | 6.00 | 330 | 4.93 | 0.22 | 9.11 | 0 | |||||

| W. siamensis (8) | W. baschi | 11.39 | 28 | 0.32 | 0.44 | 0.82 | 0 | |||||

| W. baschi (7) | W. crosseana | 6.00 | 28 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0 | 446 | 6.02 | 0.32 | 14.19 | 6.33 |

| Gabbia wykoffi (59) | G. pygmaea | 0 | 1761 | 3.14 | 0.05 | 6.69 | 0 | |||||

| G. pygmaea (3) | G. wykoffi | 0 | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | |||||

| G. erawanensis (8) | B. siamensis goniomphalos | 15.73 | 28 | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.82 | 0 | 673 | 6.62 | 0.29 | 22.16 | 0 |

| Hydrobioides nassa (23) | W. crosseana | 14.13 | 253 | 0.47 | 0.03 | 2.20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total (217) | 63.34 | 3724 | 13.30 | 1.81 | 27.91 | 0 | 3229 | 14.91 | 0.74 | 47.12 | 0 |

Figure 3. Pairwise distances (K2P) for COI sequences from snail species in the family Bithyniidae separated into two categories: (a) intraspecific; (b) interspecific.

The high intraspecific divergences in W. crosseana and G. wykoffi could indicate the presence of previously unrecognized cryptic species. DNA barcoding has proven invaluable at detecting cryptic species, which in many cases, are subsequently corroborated by life history, morphological or other character sets [51-54]. For these two snail species, the clusters represent allopatric populations with no apparent morphological differences, so it is currently unclear if they represent merely isolated populations or separate entities with differences yet to be revealed. Conversely, the sharing of identical barcode sequence in G. pygmaea and one northern Thailand population of G. wykoffi may be indicative of introgressive hybridization, incomplete lineage sorting, misidentification, or a previously unrecognized synonymy. Further investigations into these groups are necessary to untangle and confirm these predictions and the use of more holistic approaches to delimit species boundaries will be beneficial.

An important finding in the present study is that the three first intermediate hosts (B. s. siamensis, B. s. goniomphalos and B. funiculata) of Southeast Asian liver fluke can all be distinguished by COI barcodes. All three taxa of Bithynia sp. form monophyletic clusters, with 1.5% divergence between the two subspecies of B. siamensis and both subspecies had 7.1% divergence from B. funiculata (Table 3). Because the two subspecies of B. siamensis are morphologically indistinguishable, the capacity of DNA barcoding to discriminate them is significant. Moreover, morphological similarity has created taxonomic confusion and difficulties in the accurate identification of B. s. siamensis and B. s. goniomphalos which are currently believed to be distributed in the north, central, south and northeast of Thailand [26,29,36-38]. As well, the capacity to rapidly diagnose all stages of the host’s life cycle is essential for better understanding of the epidemiology of this parasite-induced disease.

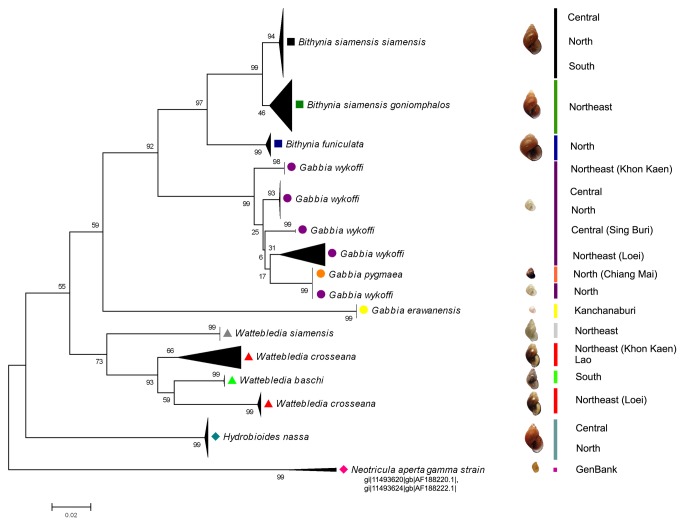

The barcoding success for the Bithyniid species examined in this project was 80%, with nearly all taxa forming discrete monophyletic clusters (Figure 4). The two exceptions are G. pygmaea and one population of G. wykoffi, which share an identical COI sequence (see above). These two taxa might possibly be cryptic species. However, the adult size of G. wykoffi is double that of G. pygmaea. Distinct paraphyly was found in W. crosseana. The results indicated that W. crosseana samples from different localities may well represent cryptic species because they are morphologically similar but genetically distinct. Cryptic species of W. crosseana might be resulted from some factors such as different localities which would develop to different genotype. G. wykoffi was separated into more than one geographically-restricted cluster respectively comprising collection localities from the central, north or northeast regions of Thailand. These clusters might be cryptic species according to this analysis as same as W. crosseana. However, more comprehensive analyses of the systematics of these taxa using more specimens, representing their known geographic distribution, as well as more evidence from independent biological investigations, are required before this hypothesis can be verified.

Figure 4. Neighbour- joining tree (K2P) for 10 species/subspecies of snails in the family Bithyniidae.

The number of individuals for each branch is given in parentheses. A detailed version of this tree, including locality information, is provided in Figure S1.

Similar studies which have also been reported in other organisms [52-59], yet over all DNA barcoding has proven reliable in identifying species in more than 90% of the organisms investigated [60]. The neighbour-joining tree and ME analysis also revealed that in general, individuals tended to cluster in accordance with collection localities (Supporting Information, Figure S1, S2). The results from ME analysis were very similar to the neighbor-joining analysis so the latter was used to generate diagrams.

The genera Wattebledia and Bithynia formed monophyletic clusters as well, but Gabbia did not. The selection of Neotricula aperta gamma strain (in the same superfamily) from GenBank as the outgroup appeared legitimate as it clustered separately from other snails in family Bithyniidae. Increased taxon, geographic, and gene sampling would be worthwhile to further explore the two ‘barcode outliers’ and the ability of COI to infer geographic provenance and phylogenetic affinities in this group.

In summary, the present study has studied genetic-variation in ten species/subspecies of Bithyniidae from Thailand using COI. Sequence divergences were lower for intraspecific than congeneric comparison. Using COI, 80% of the studied snail taxa could accurately identified. In comparison with other methods for identifying snails in this family, DNA barcoding is quicker, easier and more applicable, it is suitable for young snail identification which will be beneficial for understanding the epidemiology of opisthorchiasis transmission.

Supporting Information

Genetic distances for all specimens in family Bithyniidae.

(XLS)

Neighbour-joining tree (Distance model: Kimura-2-Parameter) of profile and test taxa; includes a list of BOLD with Process ID, taxa names, length of sequence and locality.

(JPG)

Minimum Evolution tree (ME) of 218 COI sequences of 10 species/subspecies of snails in the family Bithyniidae. The number of individuals for each branch is given in parentheses.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank the staffs of the Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada, especially Mr. Sean Prosser for providing technical advice. Dr. Jeff Webb aided with data analysis, while Dr. Jeremy R. deWaard provided valuable comments on the manuscript. We also thank Assistant Professor Dr. Pairat Tarbsripair, the Malacologist who confirmed our identification species of the specimens. Fieldwork that provided the basis for this work would not have been completed without the gracious support from Dr. Pairat Tarbsripair, Dr. Supawadee Piratae, Dr. Panita Khampoosa, Chalermlap Donthaisong, Patpicha Arunsan, Dr. Apiporn Suwannatrai, and Kulwadee Suwannatrai.

Funding Statement

The study was supported by the Higher Education Research Promotion and National Research University Project (NRU) of Thailand, and the Office of the Higher Education Commission, Ministry of Education of Thailand and through the Health Cluster (SHeP-GMS), Khon Kaen University, Thailand. Jutharat Kulsantiwong thanks the Office of the Higher Education Commission for supporting her PhD program (CHE) in the Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Thammasat University, and UdonThani Rajabhat University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Thomas W, Davis GM, Chen CE, Zhou XN, Zeng PX et al. (2000) Oncomelania hupensis (Gastropoda: Rissooidea) in eastern China: molecular phylogeny, population structure, and ecology. Acta Trop 77: 215-227. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(00)00143-1. PubMed: 11080513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carvalho OS, Caldeira RL, Simpson AJG, THDA Vidigal (2001) Genetic variability and molecular identification of Brazilian Biomphalaria species (Mollusca: Planorbidae). Parasitology 123: S197-S209. PubMed: 11769284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jones CS, Rollinson D, Mimpfoundi R, Ouma J, Kariuki HC et al. (2001) Molecular evolution of freshwater snail intermediate hosts within the Bulinus forskalii group. Parasitology 7: 277-292. PubMed: 11769290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davis GM, Wilke T, Spolsky CM, Qiu CP, Qiu DC et al. (1998) Cytochrome oxidase I-based phylogenetic relationships among the Pomatiopsidae, Hydrobiidae, Rissoidae and Truncatellidae (Gastropoda: Caenogastropoda: Rissoacea). Malacologia 40: 251-266. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Delicado D, Ramos MA (2012) Morphological and molecular evidence for cryptic species of springsnails [genus Pseudamnicola ( Corrosella) (Mollusca, Caenogastropoda, Hydrobiidae)]. Zookeys 190: 55-79. PubMed: 22639531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kodcharin P (2006) Genetic variation of Bithyniasiamensisgoniomphalos, first intermediate host of Opisthorchisviverrini in the basin of Mun and Chi River, Thailand by RAPD. M.Sc. Thesis: The Graduate School, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand.. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duangprompo W (2007) Genetic variation of snails in the family Bithyniidae in Thailand and identification of Bithyniasiamensisgoniomphalos by PCR. M.Sc. Thesis: The Graduate School, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand.. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jorgensen A, Kristensen TK, Stothard JR (2007) Phylogeny and biogeography of African Biomphalaria (Gastropoda: Planorbidae), with emphasis on endemic species of the Great East African lakes. Zool J Linn Soc 151: 337-349. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00330.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caldeira RL, Jannotti-Passos LK, Carvalho OS (2009) Molecular epidemiology of Brazilian Biomphalaria: A review of the identification of species and the detection of infected snails. Acta_Trop 111: 1-6. PubMed: 19426656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kiatsopit N, Sithithaworn P, Boonmars T, Tesana S, Chanawong A et al. (2011) Genetic markers for studies on the systematics and population genetics of snails, Bithynia spp., the first intermediate hosts of Opisthorchis viverrini in Thailand. Acta Trop 118: 136-141. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.02.002. PubMed: 21352793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hebert PDN, Cywinska A, Ball SL, deWaard JR (2003) Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc R Soc Lond B 270: 313-321. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hebert PDN, Ratnasingham S, deWaard JR (2003) Barcoding animal life: cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 divergences among closely related species. Proc R Soc Lond B 270: 96-99. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0025. PubMed: 12952648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferri E, Barbuto M, Bain O, Galimberti A, Uni S et al. (2009) Integrated taxonomy: traditional approach and DNA barcoding for the identification of filarioid worms and related parasites (Nematoda). Front Zool 6: 1-12. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-6-1. PubMed: 19128479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harinasuta T, Riganti M, Bunnag D (1984) Opisthorchis viverrini infection: pathogenesis and clinical features. Arzneimittel Forschung 34: 1167-1169. PubMed: 6542384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Osman M, Lausten SB, El-Sefi T, Boghdadi I, Rashed MY et al. (1998) Biliary parasites. Dig Surg 15: 287-296. doi: 10.1159/000018640. PubMed: 9845601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mairiang E, Mairiang P (2003) Clinical manifestation of opisthorchiasis and treatment. Acta Trop 88: 221-227. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.03.001. PubMed: 14611876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sripa B, Leungwattanawanit S, Nitta T, Wongkham C, Bhudhisawasdi V et al. (2005) Establishment and characterization of an opisthorchiasis-associated cholangiocarcinoma cell line (KKU-100). World J Gastroenterol 11: 3392-3397. PubMed: 15948244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sripa B, Kaewkes S, Sithithaworn P, Mairiang E, Laha T et al. (2007) Liver fluke induces cholangiocarcinoma. PLOS Med 7: 1148-1155. PubMed: 17622191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thamavit W, Bhamarapravati N, Sahaphong S, Vajrasthira S, Angsubhakom S (1978) Effects of dimethylnitrosamine on induction of cholangiocarcinoma in Opisthorchis viverrini infected Syrian golden hamsters. Cancer Res 38: 4634-4639. PubMed: 214229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haswell-Elkins MR, Sithithaworn P, Elkins D (1992) Opisthorchis viverrini and cholangiocarcinoma in Northeast Thailand. Parasitol Today 8: 86-89. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(92)90241-S. PubMed: 15463578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. IARC (1994) Infection with liver flukes (Opisthorchis viverrini, Opisthorchis felineus and Clonorchis sinensis). IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 61: 121-175. PubMed: 7715069. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sithithaworn P, Haswell-Elkins MR, Mairiang P, Satarug S, Mairiang E et al. (1994) Parasite-associated morbidity: liver fluke infection and bile duct cancer in northeast Thailand. Int J Parasitol 24: 833-843. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(94)90009-4. PubMed: 7982745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vatanasapt V, Parkin DM, Sriamporn S (2000) Epidemiology of liver cancer in Thailand. In: Vatanasapt V, Sripa B. Liver cancer in Thailand: Epidemiology, diagnosis and control. Khon Kaen, Thailand: Siriphan Press; pp. 3-6. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Watanapa P, Watanapa WB (2002) Liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg 89: 962-970. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02143.x. PubMed: 12153620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Honjo S, Srivatanakul P, Sriplung H, Kikukawa H, Hanai S et al. (2005) Genetic and environmental determinants of risk for cholangiocarcinoma via Opisthorchis viverrini in a densely infested area in Nakhon Phanom, northeast Thailand. Int J Cancer 117: 854-860. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21146. PubMed: 15957169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brandt RAM (1974) The non-marine aquatic Mollusca of Thailand. Archiv Mollusken 105: 1-423. [Google Scholar]

- 27. TROPMED Technical Group (1986) Snails of medical importance in Southeast Asia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 17: 282-322. PubMed: 3787310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sri-Aroon P, Butraporn P, Limsomboon J, Kerdpuech Y, Kaewpoolsri M et al. (2005) Freshwater mollusks of medical importance in Kalasin Province, Northeast Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 36: 653-657. PubMed: 16124433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wykoff DE, Harinasuta C, Juttijudata P, Winn MM (1965) Opisthorchis viverrini in Thailand- the life cycle and comparison with O. felineus . J Parasitol 51: 207-214. doi: 10.2307/3276083. PubMed: 14275209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rollinson D, Stothard JR, Jones CS, Lockyer AE, de Souza CP et al. (1998) Molecular characterization of intermediate snail hosts and the search for resistance genes. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 93: 111-116. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761998000100020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miller KB, Alarie Y, Wolfe GW, Whiting MF (2005) Association of insect life stages using DNA sequences: the larvae of Philodyte sumbrinus (Motschulsky) (Coleoptera: Dytiscidae). Syst Entomol 30: 499-509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3113.2005.00320.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rojo S, Stahls G, Perez-Banon C (2006) Testing molecular barcodes: invariant mitochondrial DNA sequences vs. the larval and adult morphology of West Palaearctic Pandasyopthalmus species (Diptera: Syrphidae: Paragini). Eur J Entomol 103: 443-458. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Puillandre N, Strong EE, Bouchet P, Boisselier MC, Couloux A et al. (2009) Identifying gastropod spawn from DNA barcodes: possible but not yet practicable. Mol Ecol Resour 9: 1311-1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2009.02576.x. PubMed: 21564902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shufran KA, Puterka GJ (2011) DNA barcoding to identify all life stages of holocycliccereal aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on wheat and other Poaceae. Ann Entomol Soc Am 104: 39-42. doi: 10.1603/AN10129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chitramvong YP, Upatham ES (1989) A new species of freshwater snail for Thailand (Prosobranchia: Bithyniidae). Walkerana 3: 179-186. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chitramvong YP (1991) The Bithyniidae (Gastropoda: Prosobanchia) of Thailand: comparative internal anatomy. Walkerana 5: 161-206. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chitramvong YP (1992) The Bithyniidae (Gastropoda: Prosobranchia) of Thailand: comparative external morphology. Malacol Rev 25: 21-38. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sri-Aroon P, Butraporn P, Limsoomboon J, Kaewpoolsri M, Chusongsang Y et al. (2007) Freshwater mollusks at designated areas in eleven provinces of Thailand according to the water resource development projects. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 38: 294-301. PubMed: 17539279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Upatham ES, Sornmani S, Kitikoon V, Lohachit C, Burch JB (1983) Identification key for the fresh-and brackish-water snails of Thailand. Malacol Rev 16: 107-132. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ratnasingham S, Hebert PDN (2007) BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System. Retrieved onpublished at whilst December year 1111 from www.barcodinglife.org. Mol Ecol Notes 7: 355-364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41. Winnepenninckx B, Backeljau T, De Wachter R (1993) Extraction of high molecular weight DNA from mollusks. Trends Genet 9: 407. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90102-N. PubMed: 8122306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Canadian Centre for DNA Barcoding (CCDB) (2008) Advancing species identification and discovery. Available: http://www.ccdb.ca/. Accessed 12 October 2008.

- 43. Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R (1994) DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol 3: 294-299. PubMed: 7881515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ivanova NV, Zemlak TS, Hanner RH, Hebert PDN (2007) Universal primer cocktails for fish DNA barcoding. Mol Ecol Notes 7: 544–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01748.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ivanova NV, deWaard JR, Hajibabaei M, Hebert PDN (2005) Protocols for high volume DNA barcoding. Available: http://www.dnabarcoding.ca/. Accessed 5 November 2008.

- 46. Ivanova N, Grainger C (2006) Pre-made frozen PCR and sequencing plates. CCDB Advances, Methods Release No. 4. Available: http://www.ccdb .ca/pa/ge/research/protocols/ccdb-advances. Accessed 30 Nov 2008

- 47. Ivanova N, Grainger C, Hajibabaei M (2006) Increased DNA barcode recovery using Platinum ® Taq. CCDB Advances, Methods Release. Retrieved onpublished at whilst December year 1111 from No.2Available:http//www.ccdb.ca. Retrieved onpublished at whilst December year 1111 from /pa/ge/research/protocols/ccdb-advances. Accessed 30 Nov 2008

- 48. McCarthy C (2008) Chromas. Available: http://technelysium.com.au/. Accessed 3 November 2009.

- 49. Hall T (2008) BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor for Windows 95/98/NT/XP. Available: http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/bioedit/bioedit.html. Accessed 3 Oct 2009

- 50. Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA et al. (2007) Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23: 2947-2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. PubMed: 17846036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S (2007) MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 24: 1596-1599. Available: http://www.megasoftware.net/. Accessed 3 November 2009. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. PubMed: 17488738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kimura M (1980) A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol 16: 111-120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. PubMed: 7463489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hebert PDN, Penton EH, Burns JM, Janzen DH, Hallwachs W (2004) Ten species in one: DNA barcoding reveals cryptic species in the neotropical skipper butterfly Astraptes fulgerator . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 14812-14817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406166101. PubMed: 15465915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Smith MA, Rodriguez JJ, Whitfield JB, Deans AR, Janzen DH et al. (2008) Extreme diversity of tropical parasitoid wasps exposed by iterative integration of natural history, DNA barcoding, morphology, and collections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 12359-12364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805319105. PubMed: 18716001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gibbs J (2009) Integrative taxonomy identifies new (and old) species in the Lasioglossum (Dialictus) tegulare (Robertson) species group (Hymenoptera, Halictidae). Zootaxa 2032: 1-38. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Locke SA, McLaughlin JD, Dayanandan S, Marcogliese DJ (2010) Diversity and specificity in Diplostomum spp. metacercariae in freshwater fishes revealed by cytochrome c oxidase I and internal transcriber spacer sequences. Int J Parasitol 40: 333-343. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.08.012. PubMed: 19737570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Meyer CP, Paulay G (2005) DNA barcoding: error rates based on comprehensive sampling. PLOS Biol 3: e422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030422. PubMed: 16336051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Meier R, Shiyang K, Vaidya G, Ng PKL (2006) DNA barcoding and taxonomy in Diptera: a tale of high intraspecific variability and low identification success. Syst Biol 55: 715-728. doi: 10.1080/10635150600969864. PubMed: 17060194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Whitworth TL, Dawson RD, Magalon H, Baudry E (2007) DNA barcoding cannot reliably identify species of the blowfly genus Protocalliphora (Diptera : Calliphoridae). Proc R Soc Lond B 274: 1731-1739. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Linares MC, Soto-Calderón ID, Lees DC, Anthony NM (2009) High mitochondrial diversity in geographically widespread butterflies of Madagascar: A test of the DNA barcoding approach. Mol Phylogenet Evol 50: 485-495. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.11.008. PubMed: 19056502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Genetic distances for all specimens in family Bithyniidae.

(XLS)

Neighbour-joining tree (Distance model: Kimura-2-Parameter) of profile and test taxa; includes a list of BOLD with Process ID, taxa names, length of sequence and locality.

(JPG)

Minimum Evolution tree (ME) of 218 COI sequences of 10 species/subspecies of snails in the family Bithyniidae. The number of individuals for each branch is given in parentheses.

(TIF)