Abstract

Increases in ethnobotanical studies and knowledge in recent decades have led to a greater and more accurate interpretation of the overall patterns related to the use of medicinal plants, allowing for a clear identification of some ecological and cultural phenomena. “Hidden diversity” of medicinal plants refers in the present study to the existence of several species of medicinal plants known by the same vernacular name in a given region. Although this phenomenon has previously been observed in a localized and sporadic manner, its full dimensions have not yet been established. In the present study, we sought to assess the hidden diversity of medicinal plants in northeastern Brazil based on the ethnospecies catalogued by local studies. The results indicate that there are an average of at least 2.78 different species per cataloged ethnospecies in the region. Phylogenetic proximity and its attendant morphological similarity favor the interchangeable use of these species, resulting in serious ecological and sanitary implications as well as a wide range of options for conservation and bioprospecting.

1. Introduction

Medicinal plants are freely circulated in Brazil, particularly in informal trade settings where several types of plants are marketed for a wide range of illnesses (see [1]). Limited access to specialty medicine and an increasing interest in the so-called natural treatments account for the rapid increase of the trade in such products in Brazil [2].

The most important vendors of medicinal plants are located in urban centers, namely, in fairs and public markets, where consumers have easy access to a wide variety of medicinal plant species together with the corresponding therapeutic indications [3]. More specifically, the regional public markets act as spaces representative of the cultural production and biological diversity of a given area [1, 4] and as centers where the empirical knowledge retained in different areas and with different origins is aggregated, conserved, and spread. Thus, the regional public markets are the pillars of a complex, open, and dynamic system of knowledge [1].

Although promising for the biological prospecting of novel drugs and pharmaceutical products, actual research at such markets has some limitations, as the identity of the vast majority of the plant species traded there cannot be safely established by means of conventional methods [1, 5–7].

In contrast with community-based ethnobotanical surveys, where the investigated resources are directly accessible in loco [8–11], research at markets and fairs is much more complex, as a significant proportion of the plant products offered to the consumers are uncharacteristic or lack the elements required for accurate taxonomic identification (see [1, 5, 6]). As a rule, only parts of the plants are sold, to wit, the ones allegedly containing the active therapeutic components, such as barks, roots, seeds, flowers, and leaves, which are sometimes dehydrated, chopped, and/or ground. As a result, it becomes quite easy to mix or mistake a similar species with or for another.

Several authors have previously expressed such concerns and proposed some methodological solutions to the problem [1, 12]. Various palliative techniques have been suggested for cataloging all medicinal plants available to the consumers at public markets, some of which are quite specialized and expensive [13–15], whereas others are feasible but not always viable [16, 17].

In addition to morphological similarities between species, another factor that makes it difficult to interpret the ethnobotanical data collected at public markets is the fact that multiple plants species are frequently known by the same vernacular name. Such events of semantic correspondence in ethnobotanical studies were initially detected by several authors [18–21] and then properly systematized by Berlin [22] in a study that sought to determine the relationships between the biological and traditional classification systems, thus establishing the grounds of ethnotaxonomy.

Within that ethnotaxonomic approach, Berlin [22, 23] established the notion of underdifferentiation to define the semantic correspondence between different species that share a vernacular name, of which two types were described. Underdifferentiation type 1 occurs when the species involved belong to the same genus, and type 2 occurs when they belong to different genera. When only one species corresponds to a given ethnospecies, correspondence is defined as one-to-one or biunivocal [22, 23]. Several studies of local communities have employed these notions to identify similar patterns of semantic correspondence between different species [24–28]. The species subjected to underdifferentiation have been termed ethnohomonyms.

Although quite well adjusted to the local systems, such correspondences tend to overlap and become complex when different cultural origins become somehow intertwined [29, 30]. The overlapping of homonym ethnospecies makes the understanding of ethnobotanical data originating in environments where complex cultural networks are established even more difficult, as is the case with ethnobotanical studies at regional public markets (see [6]).

We define here the “hidden diversity” of medicinal plants as the set of different homonym ethnospecies “hidden” under the same vernacular name. We coined the term “hidden diversity” based on the analogy with the notion of a “hidden harvest,” which denotes the progressive and unofficially documented appropriation of the plant biodiversity in a given area [31, 32].

According to Krog et al. [6] the impossibility of distinguishing among homonym ethnospecies is one of the major limitations to the advancement of ethnobotanical research in public markets, particularly in the case of ethnopharmacological studies of plant conservation and bioprospection. Although that phenomenon has previously been detected in a localized and sporadic manner, its full dimensions have not yet been established.

It is safe to assume that in Brazil, as a function of the plant biodiversity, environmental diversity, and multicultural and ethnic composition of the country [33], the number of homonym ethnospecies and consequently also the phenomenon of hidden diversity of medicinal plants is much more comprehensive and significant than suggested from the few occurrences recorded in the scientific literature. In the present study, we sought (1) to measure the hidden diversity, that is, the number of medicinal plant species subsumed under the same common name in the Brazilian northeast region; (2) to establish the different types of underdifferentiation of homonym ethnospecies; and (3) to assess the influence of biological diversity on the number of homonym ethnospecies. Finally, we sought to indicate some of the possible implications for conservation and biological prospecting.

Assuming that the variety of homonym ethnospecies in a given region depends on the region's biodiversity, one might expect the following: (1) for the variation in the number of homonym ethnospecies to be directly proportional to the size of the sampled area, as larger areas theoretically include a wider variety of environments, and consequently, also greater biological diversity and (2) that a significant number of the homonym ethnospecies should be representative of the native flora compared to the group of species with one-to-one correspondence.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of the Study Area

The northeast region of Brazil includes nine federal units and represents a total area of 1,558,196 km2, which corresponds to 18% of the country's territory. It is located in an intertropical zone limited by the Atlantic Ocean to the east and north, the Amazonian rainforest to the northwest, and the Cerrado (Brazilian savannah) domain to the west and southwest [34]. The vegetation is mainly xerophytic, being the Caatinga (Brazilian xeric shrubland), a highly peculiar biome with a high degree of endemism [35–37]. Atlantic ombrophilous forest predominates in the coastal area. Currently, this forest is one of the most seriously threatened biomes in the world, and only 5% of its original area remains [38, 39]. Enclaves of Cerrado and rainforest are widely present as areas of disjunct vegetation [40–43], making the Brazilian northeast region a strategic area from the perspective of global richness and biological diversity [44, 45].

From the demographic point of view, the total population of the northeast region comprises approximately 49 million inhabitants, primarily distributed along the coastal area where most state capitals and major cities are located, which together host approximately 40% of the population [34]. The cultural diversity of the northeast region is high due to the ethnic miscegenation resulting from the colonization of Brazil [46, 47], and the population includes Europeans, mostly Portuguese and Dutch, black slaves from Africa, and the various indigenous peoples. In addition, it is worth observing that in the last ten years, the economic growth of the region was significantly higher than the national average [34].

2.2. Data Survey

Six of the nine northeastern states were included in the analysis based on the need to survey the widest possible diversity of cultural representations and environments and the need to take into account the logistics of access and permanence at the study sites. For the purposes of the present study, we assumed that the expression of the regional culture is more diversified at the state capitals because they exhibit the largest population density, including immigrants from other states and/or the inland cities.

The states and corresponding capitals sampled were as follows: Maranhão/São Luiz, Ceará/Fortaleza, Paraíba/João Pessoa, Pernambuco/Recife, Alagoas/Maceió, and Sergipe/Aracaju. The primary site of medicinal plant trade in each state capital was identified, and thus the following markets were selected: the Mercado Central (Central Market) in São Luiz/MA, Mercado de São Sebastião (St. Sebastian Market) in Fortaleza/CE, Mercado Central in João Pessoa/PB, Mercado São José (St. Joseph Market) in Recife/PE, Mercado da Produção (Production Market) in Maceió/AL, and Mercado Albano Franco (Albano Franco Market) in Aracaju/SE.

Following an initial exploratory visit, an appointment was made for data collection. The plant vendors at each selected market were informed as to the nature of the study and invited to participate. Some vendors refused immediately, and others initially agreed and then went back on their original agreement. As a result, a total of 22 respondents were interviewed and provided a representative sample of the vernacular names of the plants traded in the region. In the state of Pernambuco, the ethnobotanical studies in public markets are already more advanced. Albuquerque and colleagues [1] previously found a significant decrease in the availability of plant vendors in this state based on only two samples obtained over an eight-year period. The in situ observations and data collected for the present study suggest that this decrease in availability may represent a general trend that can be explained by several factors. For instance, the lack of regulation and control of the sector in regards to health and ecological aspects may generate mistrust and insecurity among vendors. The vendors may also experience a lack of return research or “benefits" that would otherwise entice them to be informants. In addition, the harsh economic conditions of the country have removed a significant number of vendors from the market, and unrelenting derogatory campaigns have undermined the informal trade markets in the media. Vendors in the informal trade markets also experience increasing competition with food stores, which are common in large urban centers and usually have better infrastructure, availability, and sanitary conditions. There is also a lack of interest in new generations to continue the family traditions of using and trading medicinal plants.

After the study was explained, the respondents freely signed an informed consent form. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Pernambuco (Universidade Federal de Pernambuco—UFPE) no. 0039.0.172.0000-10, FR (Folha de Rosto—Title Page) 3139660.

Although some authors [1] have reported that several terms are used to describe vendors of medicinal plants, eventually including hierarchical criteria, in the present study, we used the generic term “herbalist” (locally known as “erveiro”) to allude to any type of vendor of medicinal plants. The term ethnospecies is used in the present study to allude to the common or vernacular names given to the medicinal plants.

Using a field notebook, we made records of the catalogs of plants traded by the herbalists as mentioned in semistructured interviews [48]. For the purposes of the study, the plants available in stock at the time of the study as well as those traded in the previous 12 months were taken into consideration. The common names of the plants were recorded as spelled by the respondents.

2.3. Data Analysis

The ethnobotanical data supplied by the herbalists in the various studied northeastern states were transcribed and entered in digital spreadsheets using MS Excel 2003 software, thus creating a Market Relational Database (MRD). The MRD was used to map the geographical distributions of the ethnospecies across the Brazilian northeast region and identify the most frequently occurring ones.

In parallel, an Ethnobotanical Survey Database (ESD) was created and populated. For that purpose, 55 ethnobotanical surveys of the northeastern states were identified, and the listed species and ethnospecies were entered in the ESD. The plants not identified at the species level were not included. Only relevant studies were selected: most (45) were published in major scientific journals, seven were Master's dissertations, one was a doctoral thesis, one a book, and one the Development Plan of a major Brazilian university (Federal University of Bahia—Universidade Federal da Bahia, UFBA).

The data entered in both databases (MRD and ESD) were then crosschecked to produce a detailed list of the ethnospecies mentioned both in the ethnobotanical surveys and by the respondents in our study, with the corresponding species. This step allowed for the identification of the homonym species and their clustering around the corresponding ethnospecies.

We selected a sample corresponding to 40% of the ethnospecies included in both databases (MRD and ESD) based on their frequency in the ethnobotanical surveys. Thus, only the 165 most frequent ethnospecies out of a total of 406 listed in the ethnobotanical surveys were selected for analysis.

The sampling criteria used were based on two assumptions: (1) ethnobotanical research is still incipient in most of the northeast region, and thus, infrequent ethnospecies might suggest a merely temporary pattern of semantic correspondence, consequently masking the results, the number of one-to-one correspondences in particular and (2) the ethnospecies most frequently mentioned in the regional ethnobotanical surveys might represent the patterns of semantic correspondence in a more unequivocal and reliable manner.

The corresponding species were allocated to three groups: one comprised the species with one-to-one correspondences, the second, the homonym ethnospecies with type 1 underdifferentiation, and the third, the homonym ethnospecies with type 2 underdifferentiation, according to Berlin's [23] classification. The corresponding species were subjected to synonym analysis; the names that are currently valid were duly recorded based on the List of Species of the Brazilian Flora 2012 [49] and the database of the Missouri Botanical Garden [50], which were also used to establish the biogeographic status of each species to classify them as native or exotic.

To assess whether underdifferentiation (sensu Berlin [23]), expressed as the number of homonym ethnospecies, varies as a function of the biological diversity of a given area, we compared the results corresponding to the northeast region with a geographically narrower sample, based on the assumption that the larger the area, the wider the environmental variety, and thus, the more diversified the flora.

That narrower sample was represented by the state of Pernambuco, which is the northeastern state most thoroughly studied from an ethnobotanical perspective. The numbers of homonym ethnospecies and one-to-one correspondences of the northeast region were compared to those of Pernambuco. The frequency of species in the respective categories of semantic correspondence (i.e., one-to-one and underdifferentiation) was analyzed by means of G tests [51] as were the percentages of native and exotic species in each group.

3. Results

The ethnospecies (n = 165) sampled based on the data collected at the visited markets exhibited correspondence with 459 species, corresponding to 228 genera and 90 families (Table 1). The ratio of species to ethnospecies was 2.78. From the total number of analyzed ethnospecies, only 41 (25%) exhibited one-to-one correspondence, whereas 124 (75%) exhibited underdifferentiation and correspondence to 418 species. Approximately 62% of the homonym ethnospecies exhibited two or three corresponding species, although in some cases, a single ethnospecies included up to nine corresponding homonym species, as, for example, “quebra-pedra” (stonebreaker) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ethnospecies marketed in the Northeast Brazil and the corresponding species cataloged in the scientific literature.

| Vernacular name | Family | Scientific name in the original source | Valid scientific name | Origin | Literature | State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aroeira | Anacardiaceae | Myracrodruon urundeuva Allemão | Myracrodruon urundeuva Allemão | N | [1, 3, 9, 52–78] | PE, PB, SE, CE, PI, MA, RN, BA |

| Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi | Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi | N | [1, 11, 65, 79–84] | PE, RN, BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Cajá | Anacardiaceae |

Spondias mombin L. Spondias lutea L. |

Spondias mombin L. | N | [56, 57, 63, 67, 76, 82, 85–87] | PE, PB, PI, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Abre Caminho |

Fabaceae | Centrosema brasilianum (L.) Benth. | Centrosema brasilianum (L.) Benth. | N | [88] | PB |

| Schizaeaceae | Lygodium venustum Sw. | Lygodium venustum Sw. | N | [1, 65] | PE | |

| Lygodium volubile Sw. | Lygodium volubile Sw. | N | [1, 65] | PE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Açoita cavalo |

Tiliaceae | Luehea divaricata Mart. | Luehea divaricata Mart. | N | [66, 68] | MA |

| Luehea ochrophylla Mart. | Luehea ochrophylla Mart. | N | [89] | PB | ||

| Luehea grandiflora Mart. | Luehea grandiflora Mart. | N | [61, 68] | MA | ||

| Luehea speciosa Willd. | ||||||

| Luehea candicans Mart. | Luehea candicans Mart. | N | [57] | PI | ||

|

| ||||||

| Acônito | Amaranthaceae | Pfaffia glomerata (Spreng.) Pedersen | Pfaffia glomerata (Spreng.) Pedersen | N | [56, 65] | PE |

| Alternanthera brasiliana (L.) Kuntze | Alternanthera brasiliana (L.) Kuntze | N | [77] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Amburana | Fabaceae | Amburana cearensis (Allemão) A. C. Sm. | Amburana cearensis (Allemão) A. C. Sm. | N | [68–70, 78, 79] | PB, CE, MA, BA |

| Burseraceae | Commiphora leptophloeos (Mart.) J. B. Gillett | Commiphora leptophloeos (Mart.) J. B. Gillett | N | [1, 3, 62–64, 70, 71, 73, 76, 80, 88] | PE, PB, RN, BA | |

| Bursera leptophloeos Mart. | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Cumaru | Fabaceae | Amburana cearensis (Allemão) A. C. Sm. | Amburana cearensis (Allemão) A. C. Sm. | N | [3, 52, 53, 55, 59, 60, 62, 67, 70–72, 76, 77] | PE, PB, CE, RN |

| Torresea cearensis Allemão | ||||||

| Dipteryx odorata (Aubl.) Willd. | Dipteryx odorata (Aubl.) Willd. | N | [81] | RN | ||

|

| ||||||

| Angelica | Rubiaceae | Guettarda platypoda DC. | Guettarda platypoda DC. | N | [56, 89] | PE, PB |

| Guettarda angelica Mart. ex Mull. Arg. | Guettarda angelica Mart. ex Mull. Arg. | N | [90] | RN | ||

|

| ||||||

| Araticum | Annonaceae | Annona crassiflora Mart. | Annona crassiflora Mart. | N | [85] | PB |

| Annona coriacea Mart. | Annona coriacea Mart. | N | [78, 91] | PB, CE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Angico | Fabaceae | Anadenanthera colubrina (Vell.) Brenan | Anadenanthera colubrina (Vell.) Brenan | N | [3, 11, 52–54, 56, 59, 60, 62–64, 67, 69, 70, 72–74, 76–80, 85, 88, 92–94] | PE, PB, CE, PI, RN, BA |

| Anadenanthera macrocarpa (Vell.) Brenan | ||||||

| Piptadenia colubrina (Vell.) Benth. | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Assa-peixe | Asteraceae | Vernonia polyanthes (Spreng.) Less. | Vernonanthura phosphorica (Vell.) H. Rob. | N | [79] | BA |

| Vernonia scabra Pers. | Vernonanthura brasiliana (L.) H. Rob. | N | [60] | CE | ||

| Vernonia ferruginea Less. | Vernonanthura ferruginea (Less.) H. Rob. | N | [82] | BA | ||

| Gochnatia velutina (Bong.) Cabrera | Gochnatia velutina (Bong.) Cabrera | N | [79] | BA | ||

| Verbesina macrophylla (Mull.) S. F. Blake | Verbesina macrophylla (Mull.) S. F. Blake | N | [83] | BA | ||

| Euphorbiaceae | Acalypha multicaulis Mull. Arg. | Acalypha multicaulis Mull. Arg. | N | [95] | SE | |

|

| ||||||

| Balaio de veio |

Asteraceae | Conocliniopsis prasiifolia (DC.) R. M. King and H. Rob. | Conocliniopsis prasiifolia (DC.) R. M. King and H. Rob. | N | [58, 95, 96] | SE |

| Lourteigia ballotifolia (Kunth) R. M. King and H. Rob. | ||||||

| Centratherum punctatum Cass. | Centratherum punctatum Cass. | N | [82] | BA | ||

| Ageratum conyzoides L. | Ageratum conyzoides L. | N | [96] | SE | ||

| Chrysobalanaceae | Hirtella ciliata Mart. and Zucc. | Hirtella ciliata Mart. and Zucc. | N | [78] | CE | |

|

| ||||||

| Batata de Purga |

Convolvulaceae | Operculina alata Urb. | Operculina alata Urb. | N | [11, 56, 66, 92] | PE, CE, MA |

| Operculina convolvulus Silva Manso | Operculina macrocarpa (L.) Urb. | N | [9, 11, 57–59, 66, 94, 97] | PE, PB, SE, CE, PI, RN | ||

| Operculina macrocarpa (L.) Urb. | ||||||

| Ipomoea purga (Wender.) Hayne | Ipomoea dumosa (Benth.) L. O. Williams | E | [68] | MA | ||

| Operculina hamiltonii (G. Don) D. F. Austin and Staples | Operculina hamiltonii (G. Don) D. F. Austin and Staples | N | [72, 88] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Burdão de velho |

Fabaceae | Pithecellobium saman (Jacq.) Benth. | Samanea saman (Jacq.) Merr. | E | [56, 61] | PE, MA |

| Samanea tubulosa (Benth.) Barneby and J. W. Grimes | Samanea tubulosa (Benth.) Barneby and J. W. Grimes | N | [86] | PB | ||

| Albizia polycephala (Benth.) Killip | Albizia polycephala (Benth.) Killip | N | [85] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Canafístula | Fabaceae | Senna spectabilis (DC.) H. S. Irwin and Barneby | Senna spectabilis (DC.) H. S. Irwin and Barneby | N | [3, 60, 67, 70, 75, 77, 90] | PE, PB, CE, RN |

| Senna martiana (Benth.) H. S. Irwin and Barneby | Senna martiana (Benth.) H. S. Irwin and Barneby | N | [75] | PE | ||

| Albizia inundata (Mart.) Barneby and J. W. Grimes | Albizia inundata (Mart.) Barneby and J. W. Grimes | N | [73] | PE | ||

| Peltophorum dubium (Spreng.) Taub. | Peltophorum dubium (Spreng.) Taub. | N | [82] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Capeba | Begoniaceae | Begonia vitifolia Schott | Begonia reniformis Dryand. | N | [1, 11, 56, 65, 94] | PE |

| Begonia reniformis Dryand. | ||||||

| Begonia huberi C. DC. | ||||||

| Piperaceae | Pothomorphe peltata (L.) Miq. | Piper peltatum L. | N | [67] | BA | |

| Piper marginatum Jacq. | Piper marginatum Jacq. | N | [53] | PE | ||

| Piper umbellatum L. | Piper umbellatum L. | N | [84] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Murici | Malpighiaceae | Byrsonima sericea DC. | Byrsonima sericea DC. | N | [11, 56, 63, 82, 86, 87, 89, 98] | PE, PB, CE, PI, BA |

| Byrsonima verbascifolia (L.) DC. | Byrsonima verbascifolia (L.) DC. | N | [98] | CE | ||

| Byrsonima coccolobifolia Kunth | Byrsonima coccolobifolia Kunth | N | [98] | CE | ||

| Byrsonima gardneriana A. Juss. | Byrsonima gardneriana A. Juss. | N | [74, 85] | PB, PI | ||

| Byrsonima correifolia A. Juss. | Byrsonima correifolia A. Juss. | N | [57] | PI | ||

|

| ||||||

| Mulungu | Fabaceae | Erythrina velutina Willd. | Erythrina velutina Willd. | N | [1, 3, 56, 59, 60, 63, 67, 71–73, 75–77, 86, 88, 89, 93, 94, 97] | PE, PB, SE, CE, RN |

|

| ||||||

| Muçambê | Cleomaceae | Cleome hassleriana Chodat | Tarenaya hassleriana (Chodat) Iltis | N | [94] | PE |

| Cleome spinosa Jacq. | Tarenaya spinosa (Jacq.) Raf. | N | [3, 9, 56, 57, 59, 65, 71, 72, 75, 92, 93] | PE, PB, CE, PI, RN | ||

|

| ||||||

| Mororó | Fabaceae | Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. | Bauhinia cheilantha (Bong.) Steud. | N | [3, 58, 60, 62–64, 71–73, 75–78, 85, 90, 95, 99] | PE, PB, SE, CE, RN |

| Bauhinia forficata Link | Bauhinia forficata Link | N | [57, 68, 81, 93] | PE, MA, RN | ||

| Bauhinia subclavata Benth. | Bauhinia subclavata Benth. | N | [80] | BA | ||

| Bauhinia smilacifolia Burch. ex Benth. | Bauhinia smilacifolia Burch. ex Benth. | N | [90] | RN | ||

| Bauhinia outimouta Aubl. | Phanera outimouta (Aubl.) L. P. Queiroz | N | [78] | CE | ||

| Bauhinia acuruana Moric. | Bauhinia acuruana Moric. | N | [74] | PI | ||

| Bauhinia ungulata L. | Bauhinia ungulata L. | N | [55] | CE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Piqui | Caryocaraceae | Caryocar brasiliense Cambess. | Caryocar brasiliense Cambess. | N | [61, 66, 68] | MA |

| Caryocar coriaceum Wittm. | Caryocar coriaceum Wittm. | N | [78, 92, 98] | CE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Quebra pedra |

Euphorbiaceae | Phyllanthus niruri L. | Phyllanthus niruri L. | N | [1, 11, 57, 59, 61, 62, 65, 66, 68, 71, 75, 84, 90, 99] | PE, PB, PI, MA, RN, BA |

| Phyllanthus amarus Schumach. and Thonn. | Phyllanthus amarus Schumach. and Thonn. | N | [9, 52, 53, 55, 56, 63, 72, 76, 92–94] | PE, PB, CE | ||

| Phyllanthus tenellus Roxb. | Phyllanthus tenellus Roxb. | N | [79, 83] | BA | ||

| Phyllanthus corcovadensis Mull. Arg. | ||||||

| Euphorbia hyssopifolia L. | Euphorbia hyssopifolia L. | N | [75, 95] | PE, SE | ||

| Chamaesyce hyssopifolia (L.) Small | ||||||

| Euphorbia thymifolia L. | Euphorbia thymifolia L. | N | [56] | PE | ||

| Euphorbia prostrata Aiton | Euphorbia prostrata Aiton | N | [75] | PE | ||

| Phyllanthus flaviflorus (K. Schum. and Lauterb.) Airy Shaw | Phyllanthus flaviflorus (K. Schum. and Lauterb.) Airy Shaw | E | [69] | BA | ||

| Phyllanthus urinaria L. | Phyllanthus urinaria L. | E | [78] | CE | ||

| Oxalidaceae | Oxalis divaricata Mart. ex Zucc. | Oxalis divaricata Mart. ex Zucc. | N | [58] | SE | |

|

| ||||||

| Sabugueiro | Adoxaceae | Sambucus australis Cham. and Schltdl. | Sambucus australis Cham. and Schltdl. | N | [9, 11, 56, 78, 81, 83, 84, 93, 94, 100] | PE, PB, CE, RN, BA |

| Sambucus racemosa L. | Sambucus racemosa L. | E | [69] | BA | ||

| Sambucus nigra L. | Sambucus nigra L. | E | [1, 11, 65, 67, 76, 79, 92, 99] | PE, CE, RN, BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Fedegoso | Boraginaceae | Heliotropium indicum L. | Heliotropium indicum L. | N | [1, 11, 52, 55, 56, 62, 63, 71, 75, 76, 85, 88–90, 92, 94] | PE, PB, CE, RN |

| Heliotropium elongatum Hoffm. ex Roem. and Schult. | Heliotropium elongatum Hoffm. ex Roem. and Schult. | N | [3, 53, 59, 72] | PE, PB, RN | ||

| Heliotropium procumbens Mill. | Heliotropium procumbens Mill. | E | [60] | CE | ||

| Fabaceae | Senna occidentalis (L.) Link | Senna occidentalis (L.) Link | N | [57, 67, 69, 80, 83, 84, 88, 95] | PB, SE, PI, BA | |

| Senna uniflora (Mill.) H. S. Irwin and Barneby | Senna uniflora (Mill.) H. S. Irwin and Barneby | N | [66] | MA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Favela | Euphorbiaceae | Cnidoscolus quercifolius Pohl | Cnidoscolus quercifolius Pohl | N | [3, 9, 58–60, 62, 70, 71, 74, 77, 88] | PB, SE, CE, PI, RN |

| Cnidoscolus phyllacanthus (Mull. Arg.) Pax and L. Hoffm. | [9, 60, 71, 74, 88] | PB, CE, PI | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Velame | Euphorbiaceae | Croton rhamnifolius Willd. | Croton heliotropiifolius Kunth | N | [3, 57, 59, 62–64, 70, 73, 75, 76, 80, 85, 94, 95] | PE, PB, SE, PI, RN, BA |

| Croton heliotropiifolius Kunth | ||||||

| Croton moritibensis Baill. | ||||||

| Croton sonderianus Mull. Arg. | Croton sonderianus Mull. Arg. | N | [61, 93] | PE, MA | ||

| Croton campestris A. St.-Hil. | Croton campestris A. St.-Hil. | N | [69, 71, 74, 78, 92] | PB, CE, PI, BA | ||

| Croton tenuifolius Pax and K. Hoffm. | Croton betaceus Baill. | N | [57] | PI | ||

|

| ||||||

| Acansu | Fabaceae | Periandra dulcis Mart. ex Benth. | Periandra mediterranea (Vell.) Taub. | N | [53, 80, 89] | PE, PB, BA |

| Periandra mediterranea (Vell.) Taub. | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Chanana | Turneraceae | Turnera ulmifolia L. | Turnera ulmifolia L. | E | [1, 9, 11, 56, 57, 60, 61, 65, 66, 68, 71, 89] | PE, PB, CE, PI, MA |

| Turnera subulata Sm. | Turnera subulata Sm. | N | [55, 59, 62, 78, 88, 89, 95] | PB, SE, CE, RN | ||

| Turnera chamaedrifolia Cambess. | Turnera chamaedrifolia Cambess. | N | [77] | PB | ||

| Turnera guianensis Aubl. | Turnera guianensis Aubl. | N | [68] | MA | ||

|

| ||||||

| João Mole | Nyctaginaceae | Guapira opposita (Vell.) Reitz | Guapira opposita (Vell.) Reitz | N | [85, 86] | PB |

| Guapira noxia (Netto) Lundell | Guapira noxia (Netto) Lundell | N | [95] | SE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Unha de gato |

Lycopodiaceae | Lycopodiella cernua (L.) Pic. Serm. | Lycopodiella cernua (L.) Pic. Serm. | N | [56] | PE |

| Alismataceae | Echinochloa colona (L.) Link | Echinochloa colona (L.) Link | E | [75] | PE | |

| Rubiaceae | Uncaria tomentosa (Willd.) DC. | Uncaria tomentosa (Willd.) DC. | N | [11, 54, 68, 72] | PE, PB, MA | |

| Fabaceae | Acacia paniculata Willd. | Senegalia tenuifolia (L.) Britton and Rose | N | [9, 52, 60, 63, 64, 73, 76] | PE, CE | |

| Mimosa somnians Humb. and Bonpl. ex Willd. | Mimosa somnians Humb. and Bonpl. ex Willd. | N | [95] | SE | ||

| Mimosa sensitiva L. | Mimosa sensitiva L. | N | [58] | SE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Lingua de Vaca |

Asteraceae | Elephantopus mollis Kunth | Elephantopus mollis Kunth | E | [66] | MA |

| Portulacaceae | Talinum portulacifolium (Forssk.) Asch. ex Schweinf. | Talinum portulacifolium (Forssk.) Asch. ex Schweinf. | E | [58] | SE | |

| Fabaceae | Centrosema brasilianum (L.) Benth. | Centrosema brasilianum (L.) Benth. | N | [90] | RN | |

| Sapotaceae | Chrysophyllum splendens Spreng. | Chrysophyllum splendens Spreng. | N | [82] | BA | |

| Alismataceae | Echinodorus subalatus (Mart.) Griseb. | Echinodorus subalatus (Mart.) Griseb. | N | [59] | RN | |

|

| ||||||

| Lacre | Clusiaceae | Vismia guianensis (Aubl.) Pers. | Vismia guianensis (Aubl.) Pers. | N | [1, 11, 53, 56, 65, 78, 86, 89, 94] | PE, PB, CE |

| Vismia brasiliensis Choisy | Vismia brasiliensis Choisy | N | [87] | PI | ||

|

| ||||||

| Jurubeba | Solanaceae | Solanum paniculatum L. | Solanum paniculatum L. | N | [1, 11, 52, 53, 56, 63, 67, 74–77, 80, 86, 88, 93, 94] | PE, PB, PI, BA |

| Solanum paludosum Moric. | Solanum paludosum Moric. | N | [58, 89, 90] | PB, SE, RN | ||

| Solanum absconditum Agra | Solanum absconditum Agra | N | [85] | PB | ||

| Solanum auriculatum Aiton | Solanum mauritianum Scop. | N | [97] | SE | ||

| Solanum erianthum D. Don | Solanum granuloso-leprosum Dunal | N | [78] | CE | ||

| Solanum polytrichum Moric. | Solanum polyrtrichum Moric. | N | [82] | BA | ||

| Solanum albidum Dunal | Solanum albidum Dunal | E | [55] | CE | ||

| Solanum tabacifolium Vell. | Solanum scuticum M. Nee | N | [79] | BA | ||

| Solanum lycocarpum A. St.-Hil. | Solanum lycocarpum A. St.-Hil. | N | [66] | MA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Cedro | Meliaceae | Cedrela fissilis Vell. | Cedrela fissilis Vell. | N | [80, 86, 93] | PE, PB, BA |

| Cedrela odorata L. | Cedrela odorata L. | N | [1, 11, 52, 53, 56, 63, 72, 73, 76, 84, 85] | PE, PB, BA | ||

| Tiliaceae | Luehea grandiflora Mart. | Luehea grandiflora Mart. | N | [69] | BA | |

|

| ||||||

| Crista de galo |

Amaranthaceae | Celosia cristata L. | Celosia argentea L. | E | [61, 63, 94] | PE, MA |

| Plumbaginaceae | Plumbago scandens L. | Plumbago scandens L. | N | [95] | SE | |

| Boraginaceae | Heliotropium indicum L. | Heliotropium indicum L. | N | [58, 78, 83, 88] | PB, SE, CE, BA | |

| Heliotropium angiospermum Murray | Heliotropium angiospermum Murray | N | [11] | PE | ||

| Heliotropium tiaridioides Cham. | Heliotropium transalpinum Vell. | N | [74] | PI | ||

|

| ||||||

| Manjerona | Lamiaceae | Ocimum americanum L. | Ocimum americanum L. | E | [1, 56, 65] | PE |

| Origanum majorana L. | Origanum majorana L. | E | [66, 84, 99, 100] | PB, MA, RN, BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Angelim | Fabaceae | Andira nitida Mart. ex Benth. | Andira nitida Mart. ex Benth. | N | [56] | PE |

| Piptadenia obliqua (Pers.) J. F. Macbr. | Pityrocarpa obliqua subsp. brasiliensis (G. P. Lewis) Luckow and R. W. Jobson | N | [60] | CE | ||

| Andira vermifuga Mart. ex Benth. | Andira vermifuga Mart. ex Benth. | N | [74] | PI | ||

| Andira paniculata Benth. | Andira paniculata Benth. | N | [87] | PI | ||

| Luetzelburgia auriculata (Allemão) Ducke | Luetzelburgia auriculata (Allemão) Ducke | N | [87] | PI | ||

|

| ||||||

| Arrozinho | Polygalaceae | Polygala gracilis Kunth | Polygala gracilis Kunth | N | [88] | PB |

| Polygala paniculata L. | Polygala paniculata L. | N | [88] | PB | ||

| Fabaceae | Zornia latifolia Sm. | Zornia latifolia Sm. | N | [67] | BA | |

|

| ||||||

| Anil estrelado | Schisandraceae | Illicium verum Hook. f. | Illicium verum Hook. f. | E | [1, 11, 53] | PE |

|

| ||||||

| Cavalinha | Equisetaceae | Equisetum hyemale L. | Equisetum hyemale L. | E | [54] | PB |

| Equisetum giganteum L. | Equisetum giganteum L. | N | [93] | PE | ||

| Equisetum arvense L. | Equisetum arvense L. | E | [84] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Chumbinho | Verbenaceae | Lantana camara L. | Lantana camara L. | N | [11, 53, 56, 58, 63, 64, 67, 73, 76, 82, 86, 88–90, 95, 96, 98] | PE, PB, SE, CE, RN, BA |

| Oxalidaceae | Oxalis insipida A. St.-Hill. | Oxalis psoraleoides Kunth | N | [73] | PE | |

| Sapindaceae | Cardiospermum corindum L. | Cardiospermum corindum L. | N | [74] | PI | |

| Cardiospermum halicacabum L. | Cardiospermum halicacabum L. | N | [74] | PI | ||

|

| ||||||

| Camará | Verbenaceae | Lantana camara L. | Lantana camara L. | N | [60, 67, 71, 74, 88] | PB, CE, PI, BA |

| Lantana canescens Kunth | Lantana canescens Kunth | N | [58] | SE | ||

| Asteraceae | Wedelia scaberrima Benth. | Wedelia calycina Rich. | N | [90] | RN | |

| Verbesina diversifolia DC. | Verbesina diversifolia DC. | N | [86] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Canela de velho |

Melastomataceae | Miconia albicans (Sw.) Steud. | Miconia albicans (Sw.) Steud. | N | [67] | BA |

| Fabaceae | Cenostigma Gardnerianum Tul. | Cenostigma macrophyllum Tul. | N | [74] | PI | |

| Primulaceae | Cybianthus detergens Mart. | Cybianthus detergens Mart. | N | [78] | CE | |

|

| ||||||

| Catuaba | Bignoniaceae | Anemopaegma arvense (Vell.) Stellfeld and J. F. Souza | Anemopaegma arvense (Vell.) Stellfeld and J. F. Souza | N | [68] | MA |

| Erythroxylaceae | Erythroxylum amplifolium (Mart.) O. E. Schulz | Erythroxylum amplifolium (Mart.) O. E. Schulz | N | [78] | CE | |

| Erythroxylum vacciniifolium Mart. | Erythroxylum vacciniifolium Mart. | N | [66, 69] | MA, BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Japecanga | Smilacaceae | Smilax campestris Griseb. | Smilax campestris Griseb. | N | [78] | CE |

| Smilax japecanga Griseb. | Smilax japecanga Griseb. | N | [98] | CE | ||

| Smilax cissoides Mart. ex Griseb. | Smilax cissoides Mart. ex Griseb. | N | [85] | PB | ||

| Smilax rotundifolia L. | Smilax rotundifolia L. | N | [11] | PE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Vassourinha | Plantaginaceae | Scoparia dulcis L. | Scoparia dulcis L. | N | [9, 59, 61, 66, 67, 71, 74, 78, 80, 83, 88] | PB, CE, PI, MA, RN, BA |

| Asteraceae | Emilia sonchifolia (L.) DC. | Emilia sonchifolia (L.) DC. | N | [93] | PE | |

| Brassicaceae | Nasturtium officinale W. T. Aiton | Nasturtium officinale W. T. Aiton | E | [93] | PE | |

| Scrophulariaceae | Capraria biflora L. | Capraria biflora L. | N | [60] | CE | |

| Polygalaceae | Polygala paniculata L. | Polygala paniculata L. | N | [67] | BA | |

| Rubiaceae | Borreria scabiosoides Cham. and Schldl. | Borreria scabiosoides Cham. and Schldl. | N | [89] | PB | |

| Spermacoce verticillata L. | Borreria verticillata (L.) G. Mey. | N | [57] | PI | ||

|

| ||||||

| Transagem | Plantaginaceae | Plantago major L. | Plantago major L. | E | [53, 54, 67, 69, 72, 79, 83, 84, 94] | PE, PB, BA |

| Alismataceae | Echinodorus grandiflorus (Cham. and Schltd L.) Micheli | Echinodorus grandiflorus (Cham. and Schltd L.) Micheli | N | [76, 93] | PE | |

|

| ||||||

| Alcachofra | Asteraceae | Vernonia condensata Baker | Gymnanthemum amygdalinum (Delile) Sch. Bip. ex Walp. | N | [1, 53, 56, 63, 67, 76, 94] | PE |

| Cynara scolymus L. | Cynara cardunculus L. | E | [52, 63, 84] | PE, BA | ||

| Gymnanthemum amygdalinum (Delile) Sch. Bip. ex Walp. | Gymnanthemum amygdalinum (Delile) Sch. Bip. ex Walp. | N | [11] | PE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Açafrão | Zingiberaceae | Curcuma longa L. | Curcuma longa L. | E | [72, 84] | PB, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Alfavaca | Lamiaceae | Ocimum basilicum L. | Ocimum basilicum L. | E | [68, 81] | MA, RN |

| Ocimum campechianum Mill. | Ocimum campechianum Mill. | N | [9, 53, 60, 83] | PE, CE, BA | ||

| Ocimum gratissimum L. | Ocimum gratissimum L. | E | [1, 55, 56, 61, 78] | PE, CE, MA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Catolé | Arecaceae | Syagrus oleracea (Mart.) Becc. | Syagrus oleracea (Mart.) Becc. | N | [85] | PB |

| Syagrus picrophylla Barb. Rodr. | Syagrus picrophylla Barb. Rodr. | N | [55] | CE | ||

| Syagrus cearensis Noblick | Syagrus cearensis Noblick | N | [78] | CE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Mentrasto | Asteraceae | Ageratum conyzoides L. | Ageratum conyzoides L. | N | [58–60, 69, 78, 83, 94, 99] | PE, SE, CE, RN, BA |

| Stilpnopappus scaposus DC. | Stilpnopappus scaposus DC. | N | [96] | SE | ||

| Blainvillea rhomboidea Cass. | Blainvillea acmella (L.) Philipson | N | [96] | SE | ||

| Prolobus nitidulus (Baker) R. M. King and H. Rob. | Prolobus nitidulus (Baker) R. M. King and H. Rob. | N | [96] | SE | ||

| Polygalaceae | Polygala violacea Aubl. | Polygala violacea Aubl. | N | [95] | SE | |

|

| ||||||

| Catingueira | Fabaceae | Caesalpinia pyramidalis Tul. | Poincianella pyramidalis (Tul.) L. P. Queiroz | N | [3, 9, 11, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 62, 63, 67, 70, 71, 75–77, 88, 90, 95, 99] | PE, PB, SE, CE, RN |

| Poincianella pyramidalis (Tul.) L. P. Queiroz | ||||||

| Caesalpinia bracteosa Tul. | Poincianella bracteosa (Tul.) L. P. Queiroz | N | [57, 60] | CE, PI | ||

| Poincianella microphylla (Mart. ex G. Don) L. P. Queiroz | Poincianella microphylla (Mart. ex G. Don) L. P. Queiroz | N | [80] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Marmeleiro | Euphorbiaceae | Croton blanchetianus Baill. | Croton blanchetianus Baill. | N | [3, 52, 59, 63, 64, 70, 73, 76, 78, 80, 95] | PE, PB, SE, CE, RN, BA |

| Croton sonderianus Mull. Arg. | Croton sonderianus Mull. Arg. | N | [55, 62, 71, 72, 74, 75, 81, 90] | PE, PB, CE, PI, RN | ||

| Croton rhamnifolius Willd. | Croton heliotropiifolius Kunth | N | [98] | CE | ||

| Croton urticifolius Lam. | Croton urticifolius Lam. | N | [86] | PB | ||

| Croton argyrophylloides Mull. Arg. | Croton argyrophylloides Mull. Arg. | N | [76] | PE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Oiticica | Chrysobalanaceae | Licania rigida Benth. | Licania rigida Benth. | N | [9, 55, 59, 60, 70–72, 77, 85, 99] | PB, CE, RN |

|

| ||||||

| Picão | Asteraceae | Bidens pilosa L. | Bidens pilosa L. | E | [61, 67] | MA, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Barriguda | Malvaceae | Ceiba glaziovii (Kuntze) K. Schum. | Ceiba glaziovii (Kuntze) K. Schum. | N | [9, 77, 85, 88] | PB, CE |

| Bombacaceae | Chorisia glaziovii (Kuntze) E. Santos | Chorisia glaziovii (Kuntze) E. Santos | N | [63, 64, 73, 75] | PE | |

| Lamiaceae | Hypenia salzmannii (Benth.) Harley | Hypenia salzmannii (Benth.) Harley | N | [57] | PI | |

|

| ||||||

| Vique | Polygalaceae | Polygala paniculata L. | Polygala paniculata L. | N | [67, 90] | RN, BA |

| Polygala bryoides A. St.-Hil. and Moq. | Polygala bryoides A.St.-Hil. and Moq. | N | [90] | RN | ||

| Lamiaceae | Mentha spicata L. | Mentha spicata L. | E | [66, 68] | MA | |

| Mentha pulegium L. | Mentha pulegium L. | E | [56] | PE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Agrião | Brassicaceae | Nasturtium officinale W. T. Aiton | Nasturtium officinale W. T. Aiton | E | [9, 53, 56, 69, 81, 93, 94, 99] | PE, CE, RN, BA |

| Rorippa pumila (Camb.) A. Lima | Rorippa pumila (Camb.) A. Lima | E | [65] | PE | ||

| Asteraceae | Acmella ciliata (Kunth) Cass. | Acmella ciliata (Kunth) Cass. | N | [57] | PI | |

| Acmella oleracea (L.) R. K. Jansen | Acmella oleracea (L.) R. K. Jansen | N | [72] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Algodão | Malvaceae | Gossypium hirsutum L. | Gossypium hirsutum L. | E | [57, 78, 93] | PE, CE, PI |

| Gossypium barbadense L. | Gossypium barbadense L. | E | [56, 67, 78] | PE, CE, BA | ||

| Gossypium herbaceum L. | Gossypium herbaceum L. | E | [66, 68, 69, 75, 83, 84] | PE, MA, BA | ||

| Gossypium arboreum L. | Gossypium arboreum L. | E | [61] | MA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Ameixa | Olacaceae | Ximenia americana L. | Ximenia americana L. | N | [3, 9, 11, 53, 55, 57–60, 62, 70, 74, 78, 90, 97] | PE, PB, SE, CE, PI, RN |

| Sapotaceae | Chrysophyllum arenarium Allemão | Chrysophyllum arenarium Allemão | N | [98] | CE | |

| Myrtaceae | Eugenia cumini (L.) Druce | Syzygium cumini (L.) Skeels | E | [68] | MA | |

| Rosaceae | Prunus domestica L. | Prunus domestica L. | E | [81] | RN | |

|

| ||||||

| Anador | Lamiaceae | Plectranthus barbatus Andrews | Plectranthus barbatus Andrews | E | [68] | MA |

| Ocimum selloi Benth. |

Ocimum carnosum (Spreng.) Link and Otto ex Benth. |

N | [67] | BA | ||

| Acanthaceae | Justicia gendarussa Burm. f. | Justicia gendarussa Burm. f. | E | [53] | PE | |

| Justicia pectoralis Jacq. | Justicia pectoralis Jacq. | N | [52, 55, 63, 94] | PE, CE | ||

| Amaranthaceae | Alternanthera brasiliana (L.) Kuntze | Alternanthera brasiliana (L.) Kuntze | N | [67, 69] | BA | |

| Pfaffia glomerata (Spreng.) Pedersen | Pfaffia glomerata (Spreng.) Pedersen | N | [67, 79] | BA | ||

| Asteraceae | Artemisia vulgaris L. | Artemisia vulgaris L. | E | [72, 78] | PB, CE | |

| Iodina rhombifolia Hook. and Arn. | Jodina rhombifolia (Hook. and Arn) Reissek | N | [100] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Arruda | Rutaceae | Ruta graveolens L. | Ruta graveolens L. | E | [1, 9, 11, 52–57, 63, 65, 67–69, 72, 75, 76, 78, 79, 81, 83, 84, 93, 94, 99–101] | PE, PB, SE, CE, PI, MA, RN, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Artemísia | Asteraceae | Artemisia vulgaris L. | Artemisia vulgaris L. | E | [54, 69, 83, 84, 94] | PE, PB, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Bambu | Poaceae | Dendrocalamus giganteus Wall. ex Munro | Dendrocalamus giganteus Wall. ex Munro | E | [11, 56] | PE |

| Bambusa arundinacea (Retz.) Willd. | Bambusa bambos (L.) Voss | E | [69] | BA | ||

| Bambusa vulgaris Schrad. ex J. C. Wendl. | Bambusa vulgaris Schrad. ex J. C. Wendl. | E | [84] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Janauba | Apocynacaee | Himatanthus bracteatus (A. DC.) Woodson | Himatanthus bracteatus (A. DC.) Woodson | N | [82] | BA |

| Himatanthus sucuuba (Spruce ex Mull. Arg.) Woodson | Himatanthus sucuuba (Spruce ex Mull. Arg.) Woodson | N | [66] | MA | ||

| Himatanthus drasticus (Mart.) Plumel | Himatanthus drasticus (Mart.) Plumel | N | [78, 98] | CE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Barbatimão | Fabaceae | Stryphnodendron adstringens (Mart.) Coville | Stryphnodendron adstringens (Mart.) Coville | N | [1, 79, 92, 94, 99] | PE, CE, RN, BA |

| Stryphnodendron barbatimam Mart. | ||||||

| Abarema cochliacarpos (Gomes) Barneby and J. W. | Abarema cochliacarpos (Gomes) Barneby and J. W. | N | [11, 53, 56, 69] | PE, BA | ||

| Pithecellobium cochliacarpum (Gomes) J. F. Macbr. | ||||||

| Stryphnodendron coriaceum Benth. | Stryphnodendron coriaceum Benth. | N | [54, 71, 78, 87, 98] | PB, CE, PI | ||

|

| ||||||

| Bom nome | Celastraceae | Maytenus rigida Mart. | Maytenus rigida Mart. | N | [1, 3, 9, 52–54, 56, 58, 60, 63, 67, 71, 73, 75–77, 88, 95–97] | PE, PB, SE, CE |

| Maytenus distichophylla Mart. | Maytenus distichophylla Mart. | N | [78] | CE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Caju | Anacardiaceae | Anacardium occidentale L. | Anacardium occidentale L. | N | [9, 11, 54, 56–58, 61, 63, 66–68, 71, 75, 78, 79, 81–84, 86, 87, 89, 92–94, 99] | PE, PB, SE, CE, PI, MA, RN, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Cardo santo | Papaveraceae | Argemone mexicana L. | Argemone subfusiformis G. B. Ownbey | E | [1, 11, 53, 60, 71, 75, 77, 79, 83, 88, 93] | PE, PB, CE, BA |

| Argemone subfusiformis G. B. Ownbey | ||||||

| Asteraceae | Carduus benedictus Gaert. | Carduus benedictus Gaert. | E | [84] | BA | |

|

| ||||||

| Candeia | Fabaceae | Plathymenia reticulata Benth. | Plathymenia reticulata Benth. | N | [61, 74] | PI, MA |

| Asteraceae | Gochnatia oligocephala (Gardner) Cabrera | Gochnatia oligocephala (Gardner) Cabrera | N | [80] | BA | |

|

| ||||||

| Canela | Lamiaceae | Cinnamomum zeylanicum Blume | Cinnamomum verum J. Presl | E | [11, 53, 63, 69, 76, 81, 83, 84, 93] | PE, RN, BA |

| Lauraceae | Nectandra cuspidata Nees and Mart. | Nectandra cuspidata Nees and Mart. | N | [56] | PE | |

| Nectandra leucantha Nees and Mart. | Nectandra leucantha Nees and Mart. | N | [94] | PE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Mandacaru | Cactaceae | Cereus jamacaru DC. | Cereus jamacaru DC. | N | [1, 9, 52, 53, 56, 58–60, 63, 71, 75, 76, 78, 80, 88, 93–95] | PE, PB, SE, CE, RN, BA |

| Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. | Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. | E | [66] | MA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Carqueja | Asteraceae | Baccharis trimera (Less.) DC. | Baccharis crispa Spreng. | N | [1, 68, 79, 83, 99] | PE, MA, RN, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Cidreira | Verbenaceae | Lippia alba (Mill.) N. E. Br. ex Britton and P. Wilson | Lippia alba (Mill.) N. E. Br. ex Britton and P. Wilson | N | [1, 3, 9, 11, 52, 53, 55, 57, 58, 61–63, 67–69, 72, 75, 76, 78, 79, 83, 93–95, 99, 100] | PE, PB, SE, CE, PI, MA, RN, BA |

| Lippia citriodora Kunth | Aloysia citriodora Palau | E | [97] | SE | ||

| Lamiaceae | Melissa officinalis L. | Melissa officinalis L. | E | [66, 81, 84, 92, 93] | PE, CE, MA, RN, BA | |

|

| ||||||

| Pra tudo | Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe brasiliensis Cambess. | Kalanchoe crenata (Andrews) Haw. | E | [75] | PE |

| Sapindaceae | Cardiospermum halicacabum L. | Cardiospermum halicacabum L. | N | [77] | PB | |

| Rutaceae | Zanthoxylum hamadryadicum Pirani | Zanthoxylum hamadryadicum Pirani | N | [74] | PI | |

| Fabaceae | Acosmium dasycarpum (Vogel) Yakovlev | Leptolobium dasycarpum Vogel | N | [78] | CE | |

|

| ||||||

| Copaiba | Fabaceae | Copaifera langsdorffii Desf. | Copaifera langsdorffii Desf. | N | [61, 66] | MA |

| Copaifera coriacea Mart. | Copaifera coriacea Mart. | N | [87] | PI | ||

| Copaifera reticulata Ducke | Copaifera reticulata Ducke | N | [68] | MA | ||

| Copaifera officinalis (Jacq.) L. | Copaifera officinalis (Jacq.) L. | N | [84] | BA | ||

| Copaifera lucens Dwyer | Copaifera lucens Dwyer | N | [69] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Courama | Malvaceae | Malvaviscus arboreus Cav. | Malvaviscus arboreus Cav. | E | [81] | RN |

| Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe brasiliensis Cambess. | Kalanchoe crenata (Andrews) Haw. | E | [53, 55, 56, 65] | PE, CE | |

| Kalanchoe blossfeldiana Poelln. | Kalanchoe blossfeldiana Poelln. | E | [94] | PE | ||

| Bryophyllum pinnatum (Lam.) Oken | Kalanchoe pinnata (Lam.) Pers. | E | [1, 65, 72, 84, 99] | PE, PB, RN, BA | ||

| Bryophyllum calycinum Salisb. | ||||||

| Kalanchoe pinnata (Lam.) Pers. | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Cordão de São Francisco |

Lamiaceae | Leonotis nepetifolia (L.) R. Br. | Leonotis nepetifolia (L.) R. Br.a | E | [9, 57, 60, 67, 68, 71] | PB, CE, PI, MA, BA |

| Leucas martinicensis (Jacq.) R. Br. | Leucas martinicensis (Jacq.) R. Br. | E | [77] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Embaúba | Urticaceae | Cecropia palmata Willd. | Cecropia palmata Willd. | N | [86] | PB |

| Cecropia pachystachya Trécul | Cecropia pachystachya Trécul | N | [61, 67, 82, 85] | PB, MA, BA | ||

| Cecropia peltata L. | Cecropia peltata L. | N | [74] | PI | ||

|

| ||||||

| Imbiriba | Annonaceae | Guatteria australis A. St.-Hil. | Guatteria australis A. St.-Hil. | N | [9] | CE |

| Lecythidaceae | Eschweilera ovata (Cambess.) Miers | Eschweilera ovata (Cambess.) Miers | N | [56, 85, 86, 89] | PE, PB | |

|

| ||||||

| Espinheira santa |

Fabaceae | Zollernia ilicifolia (Brongn.) Vogel | Zollernia ilicifolia (Brongn.) Vogel | N | [53] | PE |

| Celastraceae | Maytenus ilicifolia Mart. ex Reissek | Maytenus ilicifolia Mart. ex Reissek | N | [68, 72, 79] | PB, MA, BA | |

|

| ||||||

| Gengibre | Zingiberaceae | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | Zingiber officinale Roscoe | E | [53, 57, 66, 68, 72, 84, 93, 94] | PE, PB, PI, MA, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Graviola | Annonaceae | Annona muricata L. | Annona muricata L. | E | [3, 9, 11, 56, 63, 69, 75, 83, 93, 94, 99] | PE, PB, CE, RN, BA |

| Rollinia sericea (R. E. Fr.) R. E. Fr. | Annona neosericea H. Rainer | N | [67] | BA | ||

| Annona cherimola Mill. | Annona cherimola Mill. | E | [84] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Jaboticaba | Myrtaceae | Myrciaria cauliflora (Mart.) O. Berg | Plinia cauliflora (Mart.) Kausel | N | [52, 63, 69, 76] | PE, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Juá | Rhamnaceae | Ziziphus joazeiro Mart. | Ziziphus joazeiro Mart. | N | [3, 9, 56, 57, 59, 60, 62–64, 67, 68, 70–72, 74–76, 78, 80, 81, 85, 86, 88, 89, 92, 93, 95] | PE, PB, SE, CE, PI, MA, RN, BA |

| Ziziphus cotinifolia Reissek | Ziziphus cotinifolia Reissek | N | [77, 88] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Louro | Lauraceae | Laurus nobilis L. | Laurus nobilis L. | E | [81, 84, 93] | PE, RN, BA |

| Ocotea glomerata (Nees) Mez | Ocotea glomerata (Nees) Mez | N | [56] | PE | ||

| Ocimum gratisssimum L. | Ocimum gratisssimum L. | E | [52, 63, 76, 94] | PE | ||

| Ocotea duckei Vattimo | Ocotea duckei Vattimo | N | [89] | PB | ||

| Laurus azorica (Seub.) Franco | Laurus azorica (Seub.) Franco | E | [100] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Erva doce | Apiaceae | Pimpinella anisum L. | Pimpinella anisum L. | E | [1, 3, 11, 52, 56, 63, 68, 76, 78, 79, 81, 83, 92, 93, 100] | PE, PB, CE, MA, RN, BA |

| Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | E | [53, 67, 69, 84, 94] | PE, BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Endro | Apiaceae | Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | E | [1, 3, 11, 52, 63, 78] | PE, PB, CE |

| Anethum graveolens L. | Anethum graveolens L. | E | [53, 54, 57, 72, 93, 100] | PE, PB, PI | ||

|

| ||||||

| Alecrim | Lamiaceae | Rosmarinus officinalis L. | Rosmarinus officinalis L. | E | [3, 11, 52, 53, 56, 63, 65, 68, 69, 72, 75, 76, 78, 79, 84, 92, 93, 99, 100] | PE, PB, CE, MA, RN, BA |

| Fabaceae | Calliandra depauperata Benth. | Calliandra depauperata Benth. | N | [60] | CE | |

| Verbenaceae | Lippia thymoides Mart. and Schauer | Lippia thymoides Mart. and Schauer | N | [80] | BA | |

|

| ||||||

| Abacate | Lauraceae | Persea americana Mill. | Persea americana Mill. | E | [11, 63, 66, 67, 67–69, 76, 78, 79, 83, 84, 89, 94, 99] | PE, PB, CE, MA, RN, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Alfazema | Lamiaceae | Lavandula spica Cav. | Lavandula spica Cav. | E | [1, 93] | PE |

| Hyptis suaveolens (L.) Poit. | Hyptis suaveolens (L.) Poit. | N | [60] | CE | ||

| Lavandula officinalis Chaix | Lavandula officinalis Chaix | E | [99] | RN | ||

| Hyptis pectinata (L.) Poit. | Hyptis pectinata (L.) Poit. | N | [52] | PE | ||

| Verbenaceae | Aloysia lycioides Cham. | Aloysia lycioides Cham. | N | [69] | BA | |

|

| ||||||

| Alumã | Asteraceae |

Vernonia condensata Baker Vernonia bahiensis Toledo |

Gymnanthemum amygdalinum (Delile) Sch.Bip. ex Walp. |

N | [67, 79, 83, 84, 101] | SE, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Babosa | Xanthorrhoeaceae |

Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. Aloe barbadensis Mill. |

Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. | E | [1, 3, 9, 11, 52, 53, 55–57, 66–69, 76, 78, 79, 81, 92–94, 99, 101] | PE, PB, SE, CE, PI, MA, RN, BA |

| Aloe socotrina Schult. and Schult. f. | Aloe socotrina Schult. and Schult. f. | E | [83] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Boldo | Monimiaceae | Peumus boldus Molina | Peumus boldus Molina | E | [1, 3, 52, 53, 63, 76, 81, 99, 100] | PE, PB, RN |

| Lamiaceae | Plectranthus barbatus Andrews | Plectranthus barbatus Andrews | E | [57, 66, 69, 79] | PI, MA, BA | |

| Coleus barbatus (Andrews) Benth. | [79] | BA | ||||

| Plectranthus neochilus Schltr. | Plectranthus neochilus Schltr. | E | [67, 83] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Cabacinha | Cucurbitaceae | Luffa operculata (L.) Cogn. | Luffa operculata (L.) Cogn. | N | [1, 3, 11, 53, 59, 62, 66, 68, 76, 77, 84, 88, 93] | PE, PB, MA, RN, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Camomila | Asteraceae | Matricaria chamomila L. | Matricaria chamomila L. | E | [3, 9, 11, 53, 67–69, 81, 84, 93] | PE, PB, CE, MA, RN, BA |

| Coreopsis grandiflora Hogg ex Sweet | Coreopsis grandiflora Hogg ex Sweet | E | [94] | PE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Cana de macaco | Costaceae | Costus spicatus (Jacq.) Sw. | Costus spicatus (Jacq.) Sw. | N | [1, 78] | PE, CE |

| Costus spiralis (Jacq.) Roscoe | Costus spiralis (Jacq.) Roscoe | N | [67, 94] | PE, BA | ||

| Costus arabicus L. | Costus arabicus L. | N | [93] | PE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Canapum | Solanaceae | Physalis angulata L. | Physalis angulata L. | E | [57, 66, 68, 74] | PI, MA |

| Passifloraceae | Passiflora foetida L. | Passiflora foetida L. | N | [70, 77] | PB | |

|

| ||||||

| Caninana | Rubiaceae | Chiococca alba (L.) Hitchc. | Chiococca alba (L.) Hitchc. | N | [9, 82, 89] | PB, CE, BA |

| Polygalaceae | Polygala paniculata L. | Polygala paniculata L. | N | [78] | CE | |

|

| ||||||

| Capim santo | Poaceae | Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf | Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf | E | [1, 3, 9, 11, 52, 53, 55, 56, 63, 67, 69, 72, 75, 76, 78, 79, 83, 93, 94, 99–101] | PE, PB, SE, CE, RN, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Carambola | Oxalidaceae | Averrhoa carambola L. | Averrhoa carambola L. | E | [1, 11, 56, 57, 66, 79, 93, 94, 99] | PE, PI, MA, RN, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Carrapateira | Euphorbiaceae | Ricinus communis L. | Ricinus communis L. | E | [11, 56, 63, 71, 89, 93] | PE, PB |

|

| ||||||

| Cebola branca |

Liliaceae | Allium cepa L. | Allium cepa L. | E | [3, 9, 92] | PB, CE |

| Allium ascalonicum L. | Allium ascalonicum L. | E | [53, 55, 69, 76] | PE, CE, BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Chambá | Acanthaceae | Justicia pectoralis Jacq. | Justicia pectoralis Jacq. | N | [53, 56, 65, 94] | PE |

|

| ||||||

| Colônia | Zingiberaceae |

Alpinia speciosa (Blume) D. Dietr. Alpinia zerumbet (Pers.) B. L. Burtt and R. M. Sm. |

Alpinia speciosa (Blume) D. Dietr. | E | [9, 53, 65, 76, 78, 84, 93, 94, 100] | PE, PB, CE, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Confrei | Boraginaceae | Symphytum officinale L. | Symphytum officinale L. | E | [53, 67, 69, 83, 84, 93, 94] | PE, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Cravo branco | Caryophyllaceae | Dianthus caryophyllus L. | Dianthus caryophyllus L. | E | [1, 11, 52, 53, 63, 65] | PE |

| Asteraceae | Tagetes erecta L. | Tagetes erecta L. | E | [67, 72, 76, 93] | PE, PB | |

|

| ||||||

| Erva moura | Solanaceae | Solanum americanum Mill. | Solanum americanum Mill. | E | [1, 11, 52, 53, 56, 57, 60, 76, 88] | PE, PB, CE, PI |

|

| ||||||

| Espinho de cigano |

Asteraceae | Acanthospermum hispidum DC. | Acanthospermum hispidum DC. | E | [1, 3, 11, 52, 56, 63, 72, 75, 76, 88, 94, 100] | PE, PB |

|

| ||||||

| Eucalipto | Myrtaceae | Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | E | [9, 57, 63, 67, 69, 71, 72, 79, 81, 84, 92] | PE, PB, CE, PI, RN, BA |

| Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. | Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. | E | [11, 55, 56, 94] | PE, CE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Pinha | Annonaceae | Annona squamosa L. | Annona squamosa L. | E | [11, 56, 63, 75, 76, 84, 93, 99] | PE, RN, BA |

| Annona coriacea Mart. | Annona coriacea Mart. | N | [98] | CE | ||

| Annona tomentosa R. E. Fr. | Annona tomentosa R. E. Fr. | N | [98] | CE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Mamoeiro | Caricaceae | Carica papaya L. | Carica papaya L. | E | [3, 55, 68, 83, 92, 94] | PE, PB, CE, MA, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Gergelim | Pedaliaceae | Sesamum orientale L. | Sesamum orientale L. | E | [3, 9, 11, 53, 67, 81, 92] | PE, PB, CE, RN |

| Sesamum indicum L. | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Girassol | Asteraceae | Helianthus annuus L. | Helianthus annuus L. | E | [9, 11, 53, 56, 63, 68, 69, 72, 92, 93] | PE, PB, CE, MA, BA |

| Tithonia diversifolia (Hemsl.) A. Gray | Tithonia diversifolia (Hemsl.) A. Gray | E | [76] | PE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Imbira | Annonaceae | Xylopia frutescens Aubl. | Xylopia frutescens Aubl. | N | [53, 86] | PE, PB |

| Xylopia laevigata (Mart.) R. E. Fr. | Xylopia laevigata (Mart.) R. E. Fr. | N | [89] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Ipe | Bignoniaceae | Tabebuia aurea (Silva Manso) Benth. and Hook. f. ex S. Moore | Tabebuia aurea (Silva Manso) Benth. and Hook. f. ex S. Moore | N | [82] | BA |

| Tabebuia avellanedae Lorentz ex Griseb. | Handroanthus impetiginosus (Mart. ex DC.) Mattos | N | [82] | BA | ||

| Tabebuia chrysotricha (Mart. ex A. DC.) Standl. | Handroanthus chrysotrichus (Mart. ex DC.) Mattos | N | [82] | BA | ||

| Tabebuia roseo-alba (Ridl.) Sandwith | Tabebuia roseoalba (Ridl.) Sandwith | N | [82] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Pau d'arco roxo | Bignoniaceae |

Tabebuia avellanedae

Lorentz ex Griseb. Tabebuia impetiginosa (Mart. ex DC.) Standl. |

Handroanthus impetiginosus (Mart. ex DC.) Mattos | N | [3, 9, 11, 54, 56, 58, 60, 65, 69, 70, 74, 85, 89, 100] | PE, PB, SE, CE, PI, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Pau d'arco | Bignoniaceae | Tabebuia avellanedae Lorentz ex Griseb. | Handroanthus impetiginosus (Mart. ex DC.) Mattos | N | [53, 62, 80] | PE, RN, BA |

| Tabebuia impetiginosa (Mart. ex DC.) Standl. | ||||||

| Tabebuia ochracea (Cham.) Standl. | Handroanthus ochraceus (Cham.) Mattos | N | [93] | PE | ||

| Tabebuia serratifolia (Vahl) G. Nicholson | Handroanthus serratifolius (A.H.Gentry) S. Grose | N | [74, 86] | PB, PI | ||

| Tabebuia spongiosa Rizzini | Handroanthus spongiosus (Rizzini) S.Grose | N | [74] | PI | ||

| Tabebuia aurea (Silva Manso) Benth. and Hook. f. ex S. Moore | Tabebuia aurea (Silva Manso) Benth. and Hook. f. ex S. Moore | N | [63, 92] | PE, CE | ||

| Tabebuia caraiba (Mart.) Bureau | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Pepaconha | Violaceae |

Hybanthus ipecacuanha (L.) Baill. Hybanthus calceolaria (L.) Oken |

Hybanthus calceolaria (L.) Oken | N | [9, 53, 55, 56, 59, 71, 75, 77, 88, 90, 93, 94] | PE, PB, CE, RN |

| Rubiaceae |

Psychotria ipecacuanha (Brot.) Stokes Cephaelis ipecacuanha (Brot.) A. Rich. |

Carapichea ipecacuanha (Brot.) L. Andersson | N | [1, 11, 81] | PE, RN | |

|

| ||||||

| Losna | Asteraceae | Artemisia absinthium L. | Artemisia absinthium L. | E | [9, 54, 93] | PE, PB, CE |

| Artemisia vulgaris L. | Artemisia vulgaris L. | E | [1, 65] | PE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Macassa | Lamiaceae | Aeollanthus suaveolens Mart. ex Spreng. | Aeollanthus suaveolens Mart. ex Spreng. | E | [53, 56, 63, 65, 76, 84] | PE, PB, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Jatobá | Fabaceae | Hymenaea courbaril L. | Hymenaea courbaril L. | N | [9, 53, 55, 61, 63, 66, 68, 71, 75, 76, 80, 85–87, 89, 92, 93, 100] | PE, PB, CE, PI, MA, BA |

| Hymenaea martiana Hayne | Hymenaea martiana Hayne | N | [56] | PE | ||

| Hymenaea stigonocarpa Mart. ex Hayne | Hymenaea stigonocarpa Mart. ex Hayne | N | [69, 98] | CE, BA | ||

| Hymenaea aurea Y. T. Lee and Langenh. | Hymenaea aurea Y. T. Lee and Langenh. | N | [74] | PI | ||

|

| ||||||

| Jerimum | Cucurbitaceae | Cucurbita pepo L. | Cucurbita pepo L. | E | [11, 56, 68, 76, 93, 100] | PE, PB, MA |

| Cucurbita argyrosperma Hort. ex L. H. Bailey | Cucurbita argyrosperma Hort. ex L. H. Bailey | E | [78] | CE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Hortelã miuda |

Lamiaceae | Coleus forskohlii (Willd.) Briq. | Coleus forskohlii (Willd.) Briq. | E | [67] | PE |

| Mentha piperita L. | Mentha piperita L. | E | [3] | PB | ||

| Mentha viridis (L.) L. | Mentha spicata L. | E | [69] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Hortelã grauda |

Lamiaceae | Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) Spreng. | Plectranthus unguentarius Codd | E | [3, 53, 56, 69] | PE, PB, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Limão | Rutaceae | Citrus aurantiifolia (Christm.) Swingle | Citrus aurantium L. | E | [9] | CE |

| Citrus limonia (L.) Osbeck | Citrus medica L. | E | [56, 66, 69, 78, 79, 81, 84, 92, 99] | PE, CE, MA, RN, BA | ||

| Citrus limon (L.) Osbeck | ||||||

| Citrus limonum Risso | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Macela | Arecaceae | Egletes viscosa (L.) Less. | Egletes viscosa (L.) Less. | E | [1, 3, 9, 11, 53, 59, 60, 67, 72, 75, 78, 84, 88, 101] | PE, PB, SE, CE, RN, BA |

| Asteraceae | Achyrocline satureioides (Lam.) DC. | Achyrocline satureioides (Lam.) DC. | N | [81, 99] | RN | |

| Lamiaceae | Hyptis martiusii Benth. | Hyptis martiusii Benth. | N | [80] | BA | |

|

| ||||||

| Malicia | Fabaceae | Mimosa invisa Mart. ex Colla | Mimosa invisa Mart. ex Colla | N | [56] | PE |

| Schrankia leptocarpa DC. | Mimosa candollei R. Grether | N | [56] | PE | ||

| Mimosa misera Benth. | Mimosa misera Benth. | N | [90] | RN | ||

| Mimosa somnians Humb. and Bonpl. ex Willd. | Mimosa somnians Humb. and Bonpl. ex Willd. | N | [85] | PB | ||

| Mimosa pudica L. | Mimosa pudica L. | N | [78] | CE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Malva | Sterculiaceae | Piriqueta racemosa (Jacq.) Sweet | Piriqueta racemosa (Jacq.) Sweet | N | [95] | SE |

| Melochia tomentosa L. | Melochia tomentosa L. | N | [75] | PE | ||

| Waltheria indica L. | Waltheria americana L. | N | [78] | CE | ||

| Piriqueta guianensis N. E. Br. | Piriqueta guianensis N. E. Br. | N | [95] | SE | ||

| Lamiaceae | Plectranthus barbatus Andrews | Plectranthus barbatus Andrews | E | [55] | CE | |

| Malvaceae | Malva sylvestris L. | Malva erecta J. Presl and C. Presl | E | [81, 99] | RN | |

| Sida linifolia Cav. | Sida linifolia Cav. | N | [89] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Manga espada |

Anacardiaceae | Mangifera indica L. | Mangifera indica L. | E | [52, 69, 76] | PE |

|

| ||||||

| Capitãozinho | Gomphrenaceae | Gomphrena demissa Mart. | Gomphrena demissa Mart. | N | [54, 59, 62, 71, 77] | PB, RN |

|

| ||||||

| Malva rosa |

Sterculiaceae | Melochia tomentosa L. | Melochia tomentosa L. | N | [3] | PB |

| Geraniaceae | Geranium erodifolium L. | Geranium erodifolium L. | E | [53] | PE | |

| Malvaceae | Alcea rosea L. | Althaea rosea (L.) Cav. | E | [100] | PB | |

| Urena lobata L. | Urena lobata L. | N | [1, 11, 93] | PE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Malva branca |

Sterculiaceae | Waltheria rotundifolia Schrank | Waltheria rotundifolia Schrank | N | [3] | PB |

| Malvaceae | Sida cordifolia L. | Sida cordifolia L. | N | [1, 57, 60, 67, 69, 88] | PE, PB, CE, PI, BA | |

| Sida galheirensis Ulbr. | Sida galheirensis Ulbr. | N | [77] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Manjericão | Lamiaceae | Ocimum basilicum L. | Ocimum basilicum L. | E | [3, 53, 55, 65, 67, 69, 72, 76, 78, 79, 81, 94, 101] | PE, PB, SE, CE, RN, BA |

| Ociumum americanum L. | Ocumum americanum L. | E | [57, 78, 83, 93] | PE, CE, PI, BA | ||

| Ocimum minimum L. | Ocimum minimum L. | E | [68] | MA | ||

| Ocimum sanctum L. | Ocimum tenuiflorum L. | E | [84] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Mastruz | Chenopodiaceae | Chenopodium ambrosioides L. | Chenopodium ambrosioides L. | E | [1, 3, 9, 11, 52, 53, 55–57, 59, 61–63, 66–69, 72, 75, 76, 79–81, 83, 92–94, 100] | PE, PB, CE, PI, MA, RN, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Melão de São Caetano | Cucurbitaceae | Momordica charantia L. | Momordica charantia L. | E | [53, 55–57, 60, 66, 72, 75, 76, 79, 83–85, 90, 92, 94, 99] | PE, PB, CE, PI, MA, RN, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Mufumbo | Combretaceae | Combretum fruticosum (Loefl.) Stuntz | Combretum fruticosum (Loefl.) Stuntz | N | [57, 70] | PB, PI |

| Combretum leprosum Mart. | Combretum leprosum Mart. | N | [62, 71, 90] | PB, RN | ||

| Combretum mellifluum Eichler | Combretum mellifluum Eichler | N | [61] | MA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Mutamba | Sterculiaceae | Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. | Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. | N | [1, 11, 54, 56, 66, 69, 82, 85, 86, 94] | PE, PB, MA, BA |

| Ulmaceae | Trema micrantha (L.) Blume | Trema micrantha (L.) Blume | N | [74] | PI | |

|

| ||||||

| Pereiro | Apocynaccae | Aspidosperma parvifolium A. DC. | Aspidosperma parvifolium A. DC. | N | [94] | PE |

| Aspidosperma pyrifolium Mart. | Aspidosperma pyrifolium Mart. | N | [3, 52, 53, 58, 59, 62, 63, 70, 73–77, 80, 88, 95] | PE, PB, SE, PI, RN, BA | ||

| Tiliaceae | Luehea ochrophylla Mart. | Luehea ochrophylla Mart. | N | [56] | PE | |

|

| ||||||

| Pega pinto | Nyctaginaceae | Boerhavia diffusa L. | Boerhavia diffusa L. | E | [1, 3, 9, 11, 52, 53, 57, 59, 61, 63, 75, 76, 78, 90, 93–95] | PE, PB, SE, CE, PI, MA, RN |

| Boerhavia coccinea Mill. | Boerhavia coccinea Mill. | E | [55, 60, 69] | CE, BA | ||

| Boerhavia hirsuta Jacq. | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Pitanga | Myrtaceae | Eugenia uniflora L. | Eugenia uniflora L. | N | [11, 52, 56, 63, 67, 69, 75, 76, 78, 79, 83, 93, 94] | PE, CE, BA |

| Eugenia pitanga (O. Berg) Kiaersk. | Eugenia pluriflora DC. | N | [84] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Pinhão roxo | Euphorbiaceae | Jatropha gossypiifolia L. | Jatropha gossypiifolia L. | N | [56, 57, 69, 71, 75, 76, 78, 99] | PE, PB, CE, PI, RN, BA |

| Jatropha ribifolia (Pohl) Baill. | Jatropha ribifolia (Pohl) Baill. | N | [80] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Poejo | Lamiaceae | Mentha pulegium L. | Mentha pulegium L. | E | [53, 67, 83, 93] | PE, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Quebra faca | Euphorbiaceae | Croton conduplicatus Kunth | Croton conduplicatus Kunth | N | [9] | CE |

| Croton rhamnifolius Willd. | Croton heliotropiifolius Kunth | N | [53] | PE | ||

| Croton cordiifolius Baill. | Croton cordiifolius Baill. | N | [60] | CE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Quiabo | Malvaceae | Hibiscus esculentus L. | Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench | E | [53, 55, 56, 66, 67, 76, 78, 84] | PE, CE, MA, BA |

| Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Quina | Rubiaceae | Coutarea hexandra (Jacq.) K. Schum. | Coutarea hexandra (Jacq.) K. Schum. | N | [9, 53, 58, 69, 71, 76, 86, 94] | PE, PB, SE, CE, BA |

| Cinchona calisaya Wedd. | Cinchona officinalis L. | N | [66] | MA | ||

| Simaroubaceae | Quassia amara L. | Quassia amara L. | N | [68] | MA | |

| Rubiaceae | Chiococca brachiata Ruiz and Pav. | Chiococca alba (L.) Hitchc. | N | [80] | BA | |

|

| ||||||

| Romã | Punicaceae | Punica granatum L. | Punica granatum L. | E | [3, 9, 53–55, 57, 61, 63, 65, 68, 69, 72, 76, 78, 79, 81, 83, 93, 99, 100] | PE, PB, CE, PI, MA, RN, BA |

| Brassicaceae | Armoracia rusticana G. Gaertn., B. Mey., and Scherb. | Armoracia rusticana G. Gaertn., B. Mey., and Scherb. | E | [84] | BA | |

|

| ||||||

| Saião | Crassulaceae | Kalanchoe brasiliensis Cambess. | Kalanchoe brasiliensis Cambess. | E | [3, 53, 72] | PE, PB |

|

| ||||||

| Salsa | Convolvulaceae | Ipomoea asarifolia (Desr.) Roem. and Schult. | Ipomoea asarifolia (Desr.) Roem. and Schult. | N | [11, 56, 57, 59, 60, 65, 78, 85, 89] | PE, PB, CE, PI, RN |

| Ipomoea pes-caprae (L.) R. Br. | Ipomoea pes-caprae (L.) R. Br. | N | [95] | SE | ||

| Apiaceae | Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss | Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss | E | [67] | BA | |

| Petroselinum sativum Hoffm. | Petroselinum sativum Hoffm. | E | [84] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Sambacaitá | Lamiaceae | Hyptis pectinata (L.) Poit. | Hyptis pectinata (L.) Poit. | N | [58, 80, 93] | PE, SE, BA |

| Hyptis suaveolens (L.) Poit. | Hyptis suaveolens (L.) Poit. | N | [94] | PE | ||

| Hyptis mutabilis (Rich.) Briq. | Hyptis mutabilis (Rich.) Briq. | N | [76] | PE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Sena | Fabaceae | Senna acutifolia Link | Senna alexandrina Mill. | N | [53] | PE |

| Senna corymbosa (Lam.) H. S. Irwin and Barneby | Senna corymbosa (Lam.) H. S. Irwin and Barneby | N | [94] | PE | ||

| Senna martiana (Benth.) H. S. Irwin and Barneby | Senna martiana (Benth.) H. S. Irwin and Barneby | N | [77] | PB | ||

| Tephrosia purpurea (L.) Pers. | Tephrosia purpurea (L.) Pers. | N | [69] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Sucupira | Fabaceae | Bowdichia virgilioides Kunth | Bowdichia virgilioides Kunth | N | [1, 11, 56, 76, 86, 89, 98] | PE, PB, CE |

| Bowdichia nitida Spruce ex Benth. | Bowdichia nitida Spruce ex Benth. | N | [68] | MA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Tamarino | Fabaceae | Tamarindus indica L. | Tamarindus indica L. | E | [9, 11, 56, 57, 61, 63, 72, 83, 84, 92, 93] | PE, PB, CE, PI, MA, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Guiné | Phytolacacceae | Petiveria alliacea L. | Petiveria alliacea L. | N | [53, 72, 84] | PE, PB, BA |

| Petiveria tetrandra B. A. Gomes | Petiveria tetrandra B. A. Gomes | N | [79] | BA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Urucum | Bixaceae | Bixa orellana L. | Bixa orellana L. | N | [9, 55, 56, 61, 66, 69, 78, 81, 83, 84, 92] | PE, CE, MA, RN, BA |

|

| ||||||

| Tiririca | Cyperaceae | Cyperus ligularis L. | Cyperus ligularis L. | N | [95] | SE |

| Cyperus surinamensis Rottb. | Cyperus surinamensis Rottb. | N | [95] | SE | ||

| Fimbristylis dichotoma (L.) Vahl | Fimbristylis dichotoma (L.) Vahl | N | [95] | SE | ||

| Fimbristylis littoralis Gaudich. | Fimbristylis miliacea (L.) Vahl | N | [95] | SE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Junco | Cyperaceae | Eleocharis interstincta (Vahl) Roem. and Schult. | Eleocharis interstincta (Vahl) Roem. and Schult. | N | [56] | PE |

| Eleocharis elegans (Kunth) Roem. and Schult. | Eleocharis elegans (Kunth) Roem. and Schult. | N | [60] | CE | ||

| Cyperus articulatus L. | Cyperus articulatus L. | N | [59] | RN | ||

| Cyperus esculentus L. | Cyperus esculentus L. | N | [54] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Tomate | Solanaceae | Lycopersicon esculentum MilL. | Solanum lycopersicum L. | E | [56, 57, 67, 93, 99] | PE, PI, RN |

| Physalis ixocarpa Brot. ex Hornem. | Physalis philadelphica Lam. | E | [68] | MA | ||

|

| ||||||

| Trapiá | Capparidaceae | Crataeva tapia L. | Crataeva tapia L. | E | [53, 57, 63, 66, 70, 73, 75] | PE, PB, PI, MA |

|

| ||||||

| Urtiga branca | Euphorbiaceae | Cnidoscolus urens (L.) Arthur | Cnidoscolus urens (L.) Arthur | N | [1, 11, 53, 56, 59, 71] | PE, PB, RN |

| Cnidoscolus phyllacanthus (Mull. Arg.) Pax and L. Hoffm. | Cnidoscolus phyllacanthus (Mull. Arg.) Pax and L. Hoffm. | N | [76] | PE | ||

| Cnidoscolus infestus Pax and K. Hoffm. | Cnidoscolus infestus Pax and K. Hoffm. | N | [77] | PB | ||

| Lamiaceae | Lamium album L. | Lamium album L. | E | [100] | PB | |

| Loasaceae | Aosa rupestris (Gardner) Weigend | Aosa rupestris (Gardner) Weigend | N | [77] | PB | |

| Urticaceae | Urtica urens L. | Urtica urens L. | E | [54] | PB | |

|

| ||||||

| Jurema branca | Fabaceae | Piptadenia stipulacea (Benth.) Ducke | Piptadenia stipulacea (Benth.) Ducke | N | [3, 11, 60, 90] | PE, PB, CE, RN |

| Senegalia piauhiensis (Benth.) Seigler and Ebinger | Senegalia piauhiensis (Benth.) Seigler and Ebinger | N | [58] | SE | ||

| Calliandra spinosa Ducke | Calliandra spinosa Ducke | N | [90] | RN | ||

| Mimosa ophthalmocentra Mart. ex Benth. | Mimosa ophthalmocentra Mart. ex Benth. | N | [85] | PB | ||

| Mimosa tenuiflora (Willd.) Poir. | Mimosa tenuiflora (Willd.) Poir. | N | [95] | SE | ||

| Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. | Vachellia farnesiana (L.) Wight and Arn. | N | [63, 73] | PE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Jurema preta |

Fabaceae | Mimosa tenuiflora (Willd.) Poir. | Mimosa tenuiflora (Willd.) Poir. | N | [1, 3, 9, 11, 52, 53, 58–60, 63, 70–73, 75, 79–81, 85, 93, 95] | PE, PB, SE, CE, RN, BA |

| Mimosa acutistipula (Mart.) Benth. | Mimosa acutistipula (Mart.) Benth. | N | [54] | PB | ||

|

| ||||||

| Jurubeba branca |

Solanaceae | Solanum rhytidoandrum Sendtn. | Solanum rhytidoandrum Sendtn. | N | [58, 77, 88] | PB, SE |

| Solanum polytrichum Moric. | Solanum polytrichum Moric. | N | [82] | BA | ||

| Solanum stipulaceum Roem. and Schult. | Solanum stipulaceum Roem. and Schult. | N | [60] | CE | ||

| Solanum albidum Dunal | Solanum albidum Dunal | E | [55] | CE | ||

|

| ||||||

| Imburana de cheiro | Fabaceae | Amburana cearensis (Allemão) A. C. Sm. | Amburana cearensis (Allemão) A. C. Sm. | N | [1, 52, 57, 60, 63, 67, 72, 76, 77, 92] | PE, PB, CE, PI |

| Anacardiaceae | Myracrodruon urundeuva Allemão | Myracrodruon urundeuva Allemão | N | [53] | PE | |

PE: Pernambuco, PB: Paraiba. SE: Sergipe, CE: Ceará. RN: Rio Grande do Norte, BA: Bahia, MA: Maranhão, PI: Piauí.

Analysis of the data corresponding to the state of Pernambuco alone identified 138 out of the 165 ethnospecies found in the northeast region, which exhibited correspondence with 203 species. The ratio of species to ethnospecies was 1.46. The pattern of correspondence included 89 (64%) instances of one-to-one correspondence and 49 (36%) of underdifferentiation; the homonym ethnospecies represented a total of 114 species.

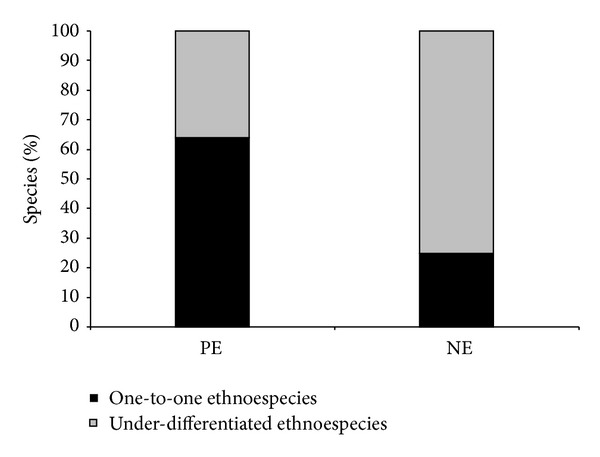

Comparison of the data from the state of Pernambuco and the northeast region showed variation in the number of one-to-one correspondences that was inversely proportional to the size of the sampled area, whereas the number of homonym ethnospecies varied in proportion to the size of the sampled area, as shown in Figure 1. Consequently, the homonym ethnospecies predominated in the northeast (NE) sample (G = 48.41; df = 1; P < 0.00001).

Figure 1.

Percentages of ethnospecies that exhibited one-to-one correspondence and underdifferentiation marketing in the northeast region and the state of Pernambuco, Brazil.

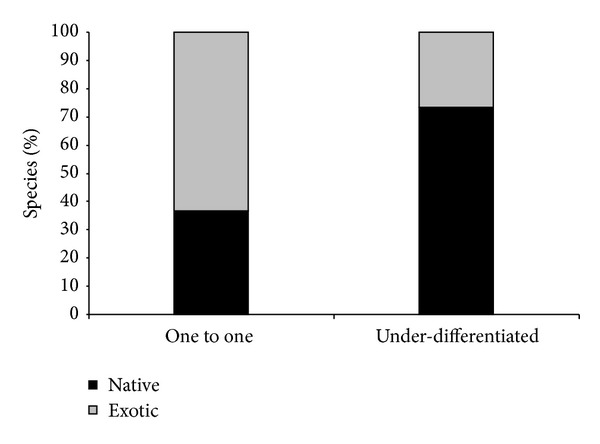

In the group of homonym ethnospecies, 309 (74%) were representative of the native flora, and 109 (26%) were exotic species. In the group of ethnospecies with one-to-one correspondence, 15 (37%) were representative of the native flora and 26 (63%) were exotic species (Figure 2). The proportion of native species relative to the proportion of exotic species was therefore significantly greater for the under-differentiated ethnospecies compared to the one-to-one ethnospecies (G = 22.52; df = 1; P < 0.00001).

Figure 2.

Percentages of native and exotic species in the group of ethnospecies that exhibited one-to-one correspondence and underdifferentiation marketing in the northeast region and the state of Pernambuco, Brazil.

Among the 418 homonym ethnospecies, 256 (61.3%) were congeneric (type 1 underdifferentiation), and 77 (18.4%) exhibited correspondence at the genus level only (type 2 underdifferentiation). That is to say, 61% of the species bear correspondence to at least one other species of the same genus with the same vernacular name, whereas 18.4% of the homonym ethnospecies exhibited correspondence with one or more species belonging to other genera in the same family. In some cases (20.3%), the homonym ethnospecies belonged to different families, such as the ethnospecies “fedegoso” (coffee senna) and “capeba” (cow-foot leaf) (Table 1).

4. Discussion

4.1. Hidden Diversity in Regional Markets

Knowledge of the hidden diversity of medicinal plant species represents an important tool because it might point to the possible patterns of substitution of homonym ethnospecies in a given area. In the case of northeast Brazil, 75% of the plants traded in regional public markets exhibit correspondence with more than one plant species.