Abstract

Malaria is a major poverty-related human infectious disease of the world. Over a billion individuals are under threat and several million die from malaria every year. The nature of disease, especially fatal disease, has been the subject of many studies. The consensus is that parasite-induced cytoadherance of red blood cells precipitates capillary blockage and inflammatory responses in affected organs. Reduced deformability of infected erythrocytes may also contribute to disease. What is not very clear is why people with significant parasite burdens display large variations in disease outcomes. Technologies which allow a detailed description of the cytoadherance properties of infected erythrocytes in individual patients, and which allow a complete description of the flow capabilities of red blood cell populations in that patient, would be very useful. Here we review the recent introduction of microfluidic technology to study malaria pathogenesis, including the fabrication processes. The devices are cheap, versatile, portable and require very small patient samples. With greater use in research laboratories and field sites, we eventually expect microfluidic methods to play important roles in malaria diagnosis, as well as prognosis.

Malaria pathogenesis

Malaria is a devastating disease that sickens or kills enough people in some African countries to negatively impact not just the country’s public health status but also its economic and social development (Gallup and Sachs, 2001). The prime causal parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, is responsible for about 1–2 million deaths a year from severe forms of the disease, most often manifested as organ failure or malarial anaemia (Miller et al., 2002; Snow et al., 2005). The underlying causes of severe disease are complex and multifaceted, but it is clear that parasite-induced biophysical and biochemical changes in red blood cells (RBCs) play a major role. These changes include cytoadhesion of RBCs to host ligands, a reduction in RBC deformability and stimulation of host immune responses, all of which play a role in disease pathogenesis. Loss of RBC deformability may contribute to physical blockages of narrow capillaries (Cranston et al., 1984; Dondorp et al., 2004), and induce anaemia by promoting the destruction of infected and uninfected cells by the spleen (Dondorp et al., 1999; Price et al., 2001). Sequestration of infected RBCs (iRBCs) to host endothelium may activate endothelial cells, alter blood flow, affect blood vessel integrity and also play a role in capillary blockage, leading to organ failure (Turner et al., 1998; Dondorp et al., 2004). The presence of iRBCs may trigger localized inflammatory responses that have deleterious effects on an organ (Grau et al., 1989; Urquhart, 1994). Host immune responses like phagocytosis could be either beneficial or detrimental to the host. The reduction in parasite burden brought about by phagocytosis is one example of the beneficial effects, but their role in secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines may in fact be responsible for the more severe symptoms of the disease (Urquhart, 1994).

Previous methods

The recognition that changes in RBC deformability, cytoadhesion and host immune responses can lead to disease has led to many different technical approaches to study these phenomena. Ektacytometry, micropipette studies and optical tweezers were used to characterize rigidification of iRBCs (Cranston et al., 1984; Nash et al., 1989; Suresh et al., 2005). Static and flow adhesion systems have been used to study the sequestration of iRBCs to host receptors and cells. These experiments helped identify relevant host cells (Udeinya et al., 1981), host proteins and parasite proteins involved in cytoadherence (Roberts et al., 1985; Berendt et al., 1989; Oquendo et al., 1989; Baruch et al., 1996; Fried and Duffy, 1996). Flow chambers address shear stress-dependent adhesion, which is relevant for mimicking cytoadhesion in capillaries in vivo (Nash et al., 1992; Cooke et al., 1994; Yipp et al., 2000; Gray et al., 2003; Avril et al., 2004).

Current needs

Despite many advances in understanding parasite-induced changes in RBC deformability, cytoadhesion and host immune responses, many fundamental questions remain unanswered about how these factors actually contribute to severe malaria. It is still a mystery why some infected patients exhibit severe forms of the disease and often die, while others can harbour high parasitaemia and remain essentially symptom-free. Unique person-to-person variations in host–parasite interactions must account for such differences in disease outcome, as cytoadherence, loss of RBC deformability and immune reactions occur in all individuals. Clues to explain such complexity are slowly emerging: for example, genetic variations in patients can affect the display of adhesive parasite proteins on RBC surfaces and impair or promote cytoadherence (Cholera et al., 2008). However, further progress would clearly benefit from advanced technologies that allow detailed, high-throughput studies on a large numbers of patients and allow study of matched host–parasite samples. Below we detail limitations for studying each major aspect of severe malaria (cytoadhesion, deformability, immune responses).

Current technologies to study host–parasite cytoadhesion, as helpful as they have been, have limitations. They do not accurately represent the cellular complexity or the micron-scale dimensions of the microvasculature where many of these interactions occur. For example, flow chambers for cytoadhesion studies have dimensions that are much larger than typical capillaries where adhered parasitized cells are found, and therefore the peculiarities of blood flow in narrow capillaries are not accurately mimicked. Flow chambers also are bulky, difficult to transport and require large sample volumes, making it difficult to study cytoadhesion in the field. Most chambers are also made of rigid materials like glass or plastic, which do not display the elastic properties of blood vessels. Furthermore, glass and plastic are not gas-permeable, which makes it difficult to study live host cells and iRBCs for an extended time under fluid flow. Finally, flow chambers with fixed shapes and sizes cannot model the complex network of capillaries found in the microvasculature, where changes in shear stresses due to blood flow in complex patterns could be critical in precipitating cytoadhesion or capillary occlusions.

Similar problems exist with current techniques to study RBC deformability. It is difficult to understand how changes in RBC deformability measured in the laboratory relate to specific in vivo outcomes in malaria patients. Techniques like ektacytometry provide only a bulk measurement of the deformability of a large population of RBCs, thus specific parasite factors that contribute to increased RBC rigidity cannot be identified. Micropipette aspiration and optical traps can give information on single cells, but these are hugely labour-intensive techniques and are unsuited for high-throughput measurements on large numbers of samples. Most studies that measure changes in RBC deformability are unable to distinguish between the underlying structural factors that contribute to these changes. Cell deformability is primarily determined by three factors: the geometry of the cell, which is given by its surface area to volume ratio, the membrane viscoelasticity and the cytoplasmic viscosity (Nash et al., 1989). Few studies to date have identified which of these factors is most important in contributing to loss of RBC deformability, and more important, which one is most relevant for causing disease symptoms, like blocked capillaries or splenic clearance.

Understanding immune responses like phagocytosis using current tools has its own limitations. For instance, most phagocytosis assays are currently performed under static conditions, which do not accurately simulate the low-shear-stress environment of the spleen. Static assays also cannot capture the in vivo situation in which circulating monocytes may either attach to or become trapped in regions of the microvasculature where iRBCs accumulate, causing localized areas of inflammation that could contribute to disease. Furthermore, the effect of physical distortions forced upon iRBCs by narrow apertures in vivo that may lead to ‘pitting’ of the parasite from the RBC cannot be studied using traditional equipment (Chotivanich et al., 2002).

Microfluidic devices

Microfluidics is a general term describing the manipulation of fluids in micron-sized channels. In many respects, the technology is highly advanced, and devices can be fabricated for many useful applications such as microanalysis of samples, chemical synthesis, single-molecule or single-cell studies and high-throughput screening of drugs (Whitesides, 2006). However, despite its vast potential, the technology is particularly underutilized in the study of parasitic infectious diseases. This picture is changing, particularly in the diagnostic field, as microfluidics is increasingly seen as an attractive low-cost option to detect multiple diseases relevant to developing economies (Yager et al., 2008).

Microfluidic devices fabricated specifically to study malaria pathogenesis have tremendous potential to overcome many of the limitations posed by more traditional methods to measure cytoadhesion and deformability (Antia et al., 2007; T. Herricks, M. Antia and P.K. Rathod, in preparation). The fabrication techniques have been specifically developed to engineer devices of diverse shapes with micron-sized dimensions (McDonald et al., 2000). Thus microfluidics allows for experiments in channels that have the same dimensions as capillaries in the microvasculature, or the narrow interendothelial slits in the spleen where iRBCs may get trapped. In one versatile approach, microfluidic channels can be cast from an elastomeric polymer called polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). It has an elastic modulus similar to many blood vessels found in vivo, more accurately mimicking the in vivo environment than devices made from glass or plastic. PDMS is also gas-permeable and thus readily accommodates long-term cell growth in a channel, allowing for the observation of long-term cell–cell interactions in a simulated capillary. These types of long-term interactions are critical not only for understanding cytoadhesion, but also for observing responses of host cells to parasite infections that only happen over several hours. Examples of such interactions could include phagocytosis of iRBCs or the release of inflammatory cytokines by either endothelial cells or macrophages.

One of the biggest advantages of using microfluidic systems is their portability and their ability to make numerous measurements using mere microlitre volumes of sample. The devices can be mounted on a microscope and data on large populations of single cells can be collected as still photos or as movies on a personal computer for further detailed analysis at a subsequent time. These features make the devices ideal for use at field sites, using matched patient samples, such as parasitized blood, serum, platelets, antibodies, phagocytic cells and possibly biopsied host samples. In addition to field sites, the devices have also proven to be useful in standard research laboratories where access to more traditional equipment is either unavailable or impractical due to the large volumes of sample needed. Indeed, the most valuable insights into the causes of severe malaria are likely to arise either from detailed studies of laboratory strains of genetic knockouts that are available in different laboratories throughout the world or, more important, from studies of variations in human and parasite samples at field sites. The microfabrication techniques used to assemble these devices can allow multiple types of different measurements, like cytoadhesion, deformability or interactions with host immune cells, in an integrated fashion on the same compact, portable chip.

Fabrication

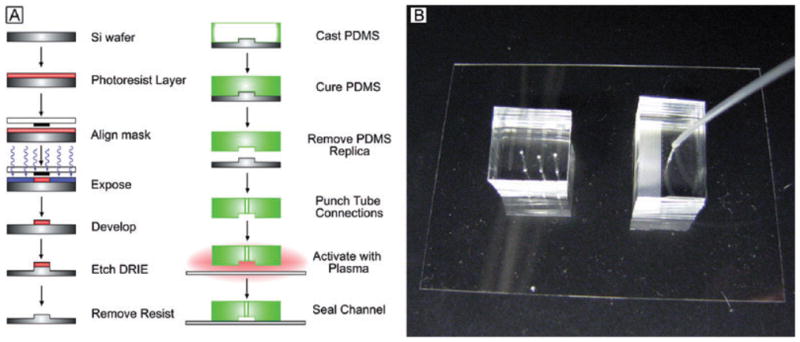

Generating PDMS microfluidic systems channels with micron-sized dimensions, and with complex shapes and patterns, initially requires the fabrication of a hard template on a silicon wafer (Fig. 1A). To get this, first, CAD software is used to generate a quartz-chrome photo mask. Using standard photolithography techniques, the pattern on the mask is transferred to a photosensitive coating on a silicon wafer. The Bosch deep reactive ion etch process then creates a negative replica of the eventual microfluidic device on the silicon wafer. Up to this point, the process requires an experienced engineer and a specialized clean room facility. The cost to generate a silicon replica increases as the feature size of the pattern is reduced. Generating replicas with feature sizes of 1 μm may cost $3000 while fabricating molds with 50–100 μm features may cost less than $500. The actual PDMS device is made by pouring the liquid elastomer over the relief pattern of the silicon replica, curing at 70°C over-night, peeling the cured PDMS off the replica and then sealing it to a glass coverslip by exposing both the PDMS and the glass to an oxygen plasma. The negative space in the PDMS formed by the relief pattern in the silicon replica becomes the microfluidic channel. A single silicon replica may produce hundreds of microfluidic devices. The channels themselves have a very long shelf life. In some cases channels have been stored for up to a year before use without loss of performance. After the initial investment, the subsequent technology for production of dozens of PDMS devices from a common silicon replica is inexpensive, and relatively easy to transfer to different laboratories or even the field.

Fig. 1.

A. A schematic diagram to illustrate the individual steps for fabrication of PDMS-based microfluidic devices for malaria pathogenesis (left).

B. Actual photographs of sample PDMS devices with flow tubings attached.

In physical appearance, the PDMS devices are small and compact – approximately 3 cm in length 1 or 2 cm in width and from 0.5 to 1 cm in height (Fig. 1B). For field studies or for experiments in other laboratories, dozens can be made at one source and easily transported to the site of the experiment. The ends of the channel are perforated with plastic tubing to allow fluid flow into and out of the channels. A syringe is connected to the outlet tubing to generate negative pressure across the channel and a digital manometer is attached through a T-junction to measure this pressure. This configuration requires no external pumps, is easy to transport and can be mounted on practically any inverted microscope for flow measurements, which once again is advantageous for transport to remote sites. As the PDMS is irreversibly sealed to the glass substrate, the channels can withstand very high pressures – greater than 8 kPa across the channels –without any leakage. Thus pressures comparable with those in small blood capillaries can be maintained by using PDMS devices.

After the channel has been fabricated, a number of published approaches can be used to coat the walls of the channels with purified protein ligands known to be important in cytoadherance (Cooke et al., 2002). These procedures may vary slightly depending on the protein, but for the most part involve chemical modification of the channel to increase its hydrophobicity to facilitate protein adsorption. For example, ICAM-1 or CD36 are easily absorbed after pre-treatment of the channels with liquid silane. Functionalization of channels with mammalian cells expressing such cytoadhesion ligands or with phagocytic cells usually requires priming the channels with proteins to promote cell adhesion, maintaining an adequate supply of fresh growth medium to the cells, as well as maintaining the correct temperature and CO2 levels in the channel (Tourovskaia et al., 2005). The ease of this procedure depends on the cell line – CHO cells for instance will attach quite readily if the channel is primed with their own growth media, but endothelial cells or BeWo cells require further pre-treatment with poly L-lysine. As the devices are small and gas-permeable, temperature and CO2 control is relatively easy to achieve during data collection, using commercially available chambers that can be mounted on microscopes.

Cytoadhesion in micron-sized channels

Microfluidic channels have been successfully used to measure cytoadhesion to numerous protein ligands and cell types that are known to play a role in sequestering iRBCs in vivo (Antia et al., 2007; Fig. 2A). Examples include purified ICAM-1, CD36 and CSA, as well as CHO cells expressing ICAM-1 (CHO-ICAM) or CD36 (CHO-CD36), Bewo cells that model cytoadhesion in the placenta (Viebig et al., 2006) and macrophages. Using microfluidic systems, rather than traditional flow chambers, allowed for novel experiments that required long-term interactions between host cells and iRBCs, and revealed novel characteristics of adhesive iRBCs in tight spaces over shorter time periods.

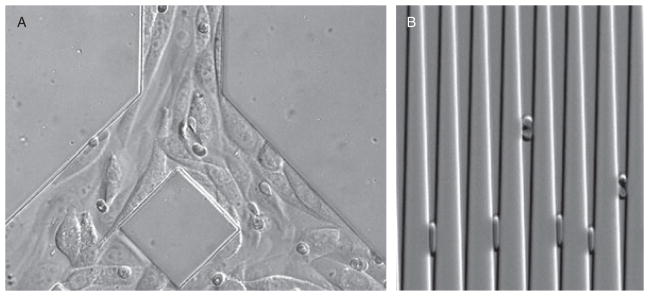

Fig. 2. Illustration of two very different applications.

A. Cytoadherance of infected erythrocytes in bifurcated channels, pre-seeded with CHO cells expressing CD-36 ligands. The cytoadhering infected RBCs were less than 5% of the total RBCs. The non-binding RBCs are moving with fluid flow at rates too fast to be captured by the camera.

B. Capture of iRBCs and uninfected RBCs in wedge-shaped channels. Lesser ‘deformability’ of iRBCs prevents them from approaching the bottom of the wedge. Thousands of RBCs can be analysed from less than a μl of blood sample.

Phagocytic interactions between macrophages in the spleen and infected erythrocytes are critical factors in both clearing malaria infections from naïve individuals and precipitating anaemia (Abdalla et al., 1980; Weiss, 1990). Previous such in vitro experiments were conducted under static conditions (McGilvray et al., 2000), despite the fact that low shear stresses are present in the spleen. Micro-fluidic devices were used, for the first time, to show the adhesion of iRBCs to macrophages under flow condition and the phagocytosis of the attached erythrocytes over time periods of up to 20 h (Antia et al., 2007). Phagocytosis of infected erythrocytes under shear flow allowed macrophages to ingest parasites together with the intact RBC membrane, but in many cases the parasites were internalized without any detectable accompanying RBC membrane. This was reminiscent of in vivo observations of parasite ‘pitting’ by macrophages (Schnitzer et al., 1972). There was also evidence of phagocytosis of un-infected cells and haemozoin, in agreement with human autopsy data (Pongponratn et al., 1989). The phagocytosis experiments again illustrate the advantages of using gas-permeable PDMS devices for longer-term observations of parasites with host cells.

Microfluidic systems also revealed qualitative differences in adhesion to cell-free ICAM-1 ligand compared with adhesion on CHO cells expressing ICAM-1 (CHO-ICAM; Fig. 2A). On the purified ligand, virtually all attached iRBCs exhibited rolling behaviour, almost never detached from the surface (rolling for several millimetres in distance), and in a jerky stepwise manner with regular periodic changes in velocity (Antia et al., 2007). In contrast, on CHO-ICAM, the majority of iRBC exhibited stationary adhesion rather than rolling adhesion. Those iRBCs that did roll on CHO-ICAM displayed sporadic behaviour: iRBCs showed large variations in their instantaneous rolling velocities, sometimes coming to a complete halt for several seconds, and sometimes detaching from the surface. These differences were not previously noticed in bulk flow chambers, and are most probably due to the presence of micron-sized cells in a micron-sized channel, which can greatly alter the flow microenvironment (Sugihara-Seki, 2000).

Microfluidic devices with controlled fluid flow allowed direct demonstration of stabilization of rolling velocities at high shear stresses (Antia et al., 2007). These ligands appear to support steady rolling adhesion even at extremely high values of shear stress. In the absence of a compensating mechanism, most cells that roll on substrates would be expected to increase their rolling velocities in response to increasing shear stresses and eventually detach from the surface (Chen et al., 1997). On CD36, iRBCs showed no significant increases in the mean rolling velocities with increases in shear stress. Behaviour on ICAM-1 was more complex, although a population of iRBCs appeared to stabilize adhesion and did not show proportional changes in velocity with increasing pressure, a fraction of iRBCs did indeed increase rolling velocities with increasing pressures.

As branching capillaries are natural sites in the circulatory system where changes in blood flow patterns can lead to alterations in wall shear stress, microfluidic technology was used to mimic such bifurcations to determine whether iRBCs rolling on ICAM-1 at such sites could reveal what may happen in the microcirculation in vivo (Antia et al., 2007). iRBCs displayed continued rolling behaviour upon encountering a fork and followed the path dictated by the bulk fluid flow. Velocities of rolling erythrocytes upon reaching the branches, however, varied from cell to cell and displayed one of two patterns. Some cells did not change rolling velocities as they moved from the bifurcating branch into the main artery of the channel, despite the increase in wall shear stress. Other cells, however, displayed significant increases in rolling velocity. Branched channels were also used to determine whether the accumulation of stably adhering iRBCs were dependent on the shear stress in a simulated capillary network. In a channel functionalized with CD36, at pressures where primarily static adhesion is observed, there was increased accumulation of iRBCs in the branches of a model capillary network relative to the main artery.

Together these cytoadhesion studies demonstrate that microfluidic devices can be fabricated to identify and possibly select for cell types that are most likely to stabilize rolling upon encountering lower shear stresses. They also show how changing shear stresses due to the shape of a capillary in vivo may be critical in determining where cytoadhesion is likely to occur. Clearly, sequestration of infected erythrocytes may depend on the location of host cells with adhesive ligands in the microvasculature, as well as the type and quantity of expressed ligands, and the nature of the individual iRBCs.

Deformability studies

The surface area to volume ratio of an erythrocyte plays an important role in determining its deformability (Gifford et al., 2003). In the past, micropipette aspiration has been used to measure surface area and volume of infected erythrocytes but this technique has several limitations, as it is labour-intensive and tedious and thus cannot be used to gain data on the large populations of cells that would be needed to understand variations in malaria infections in patients (Nash et al., 1989). Recently, we have adapted a microfluidic technique previously used on uninfected RBCs to accurately measure the cell’s surface area and volume (Herricks et al. unpubl. data; Fig. 2B). Furthermore, using the surface area and volume measurement, this allows us to calculate the minimum cylindrical diameter (MCD) to describe the smallest-diameter tube a cell may pass without increasing its surface area or rupturing (Canham and Burton, 1968). Measuring the MCD of an erythrocyte rather than its deformability has several advantages. For a given cell, the MCD describes a criterion that determines whether an infected erythrocyte may be trapped by the spleen, or obstructs small capillaries in the microcirculation. Microfluidic channel arrays with precisely engineered dimensions should furthermore be used to experimentally test predictions on the filterability of a population of erythrocytes. Thus microfluidic technology applied to the problem of RBC deformability in malaria should represent a big advance over previous techniques that measured the deformability of infected erythrocytes. The technology will be used not only to obtain quantitative information on thousands of cells at a time, but it will also provide a way to associate the deformability measurement with a physiologically important consequence (capillary blockage or filtration by the spleen).

Flowing through small, ligand-coated constrictions

The ability to integrate various parameters contributing to malaria pathogenesis allows microfluidics to stand above other technical options. In perhaps the most dramatic illustration, the flow iRBCs in ligand-coated channels with varying dimensions revealed that passage of trophozoite-stage iRBCs in microfluidic arrays, with constrictions greater than the MCD (5 μm), was not hindered by the presence of the adhesive protein ICAM-1. As the rolling iRBCs entered the constriction, they briefly ceased rolling and actually accelerated through the pore (Antia et al., 2007). This was recorded as a jump in the distance travelled over the length of the constriction and a corresponding spike in the iRBC velocity. Upon exiting the 5 μm constriction, the iRBCs efficiently reattached on the other end and continued rolling at a velocity similar to that before entering the constriction. Experiments like these, which are able to study the combined effects of RBC deformability, cytoadhesion and capillary constriction, are particularly powerful demonstrations of how microfluidic devices can be used to study malaria pathogenesis in unprecedented ways.

Future directions

The laboratory-based demonstrations of the potential utility of microfluidic devices to study malaria have been useful for highlighting important questions and mapping future applications. The devices can be readily used in most research laboratory settings that possess adequate microscopy facilities. Their adaptation for field use could be more challenging, but within reach. Simple applications to measure cytoadherence or RBC deformability will be possible in field research laboratories equipped with appropriate microscopy and computation facilities, as the devices themselves can be manufactured in advance and transported to site. The next series of advances will occur in devices that are more sophisticated and custom-designed to include modifications for specific applications, either in the field or in other laboratories. Such modifications may include internal pressure reporters, fluid control gates, internal pumps and online integration with cell sorting and functional genomic tools. There is even the possibility of integrating detection systems on the microfluidic chip, which may eventually eliminate the need for external microscopy and computing equipment for field application. We predict that microfluidic devices will play a critical role in dissecting patient to patient variation in disease outcomes. If this is true, future diagnostic devices may also include prognosis capabilities based on cellular properties of infected erythrocytes from individual patients.

References

- Abdalla S, Weatherall DJ, Wickramasinghe SN, Hughes M. The anaemia of P. falciparum malaria. Br J Haematol. 1980;46:171–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1980.tb05956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antia M, Herricks T, Rathod PK. Microfluidic modeling of cell–cell interactions in malaria pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e99. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avril M, Traore B, Costa FT, Lepolard C, Gysin J. Placenta cryosections for study of the adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to chondroitin sulfate A in flow conditions. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruch DI, Gormely JA, Ma C, Howard RJ, Pasloske BL. Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 is a parasitized erythrocyte receptor for adherence to CD36, thrombospondin, and intercellular adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3497–3502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendt AR, Simmons DL, Tansey J, Newbold CI, Marsh K. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 is an endothelial cell adhesion receptor for Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 1989;341:57–59. doi: 10.1038/341057a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canham PB, Burton AC. Distribution of size and shape in populations of normal human red cells. Circ Res. 1968;22:405–422. doi: 10.1161/01.res.22.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Alon R, Fuhlbrigge RC, Springer TA. Rolling and transient tethering of leukocytes on antibodies reveal specializations of selectins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3172–3177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholera R, Brittain NJ, Gillrie MR, Lopera-Mesa TM, Diakite SA, Arie T, et al. Impaired cytoadherence of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes containing sickle hemoglobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:991–996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711401105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chotivanich K, Udomsangpetch R, McGready R, Proux S, Newton P, Pukrittayakamee S, et al. Central role of the spleen in malaria parasite clearance. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1538–1541. doi: 10.1086/340213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke BM, Berendt AR, Craig AG, MacGregor J, Newbold CI, Nash GB. Rolling and stationary cytoadhesion of red blood cells parasitized by Plasmodium falciparum: separate roles for ICAM-1, CD36 and thrombospondin. Br J Haematol. 1994;87:162–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb04887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke BM, Coppel RL, Nash GB. Preparation of adhesive targets for flow-based cytoadhesion assays. Methods Mol Med. 2002;72:571–579. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-271-6:571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranston HA, Boylan CW, Carroll GL, Sutera SP, Williamson JR, Gluzman IY, Krogstad DJ. Plasmodium falciparum maturation abolishes physiologic red cell deformability. Science. 1984;223:400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.6362007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondorp AM, Angus BJ, Chotivanich K, Silamut K, Ruangveerayuth R, Hardeman MR, et al. Red blood cell deformability as a predictor of anemia in severe falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:733–737. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondorp AM, Pongponratn E, White NJ. Reduced microcirculatory flow in severe falciparum malaria: pathophysiology and electron-microscopic pathology. Acta Trop. 2004;89:309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried M, Duffy PE. Adherence of Plasmodium falciparum to chondroitin sulfate A in the human placenta. Science. 1996;272:1502–1504. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup JL, Sachs JD. The economic burden of malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:85–96. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford SC, Frank MG, Derganc J, Gabel C, Austin RH, Yoshida T, Bitensky MW. Parallel microchannel-based measurements of individual erythrocyte areas and Volumes. Biophys J. 2003;84:623–633. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74882-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau GE, Taylor TE, Molyneux ME, Wirima JJ, Vassalli P, Hommel M, Lambert PH. Tumor necrosis factor and disease severity in children with falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1586–1591. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906153202404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray C, McCormick C, Turner G, Craig A. ICAM-1 can play a major role in mediating P. falciparum adhesion to endothelium under flow. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;128:187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(03)00075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JC, Duffy DC, Anderson JR, Chiu DT, Wu H, Schueller OJ, Whitesides GM. Fabrication of microfluidic systems in poly (dimethylsiloxane) Electrophoresis. 2000;21:27–40. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(20000101)21:1<27::AID-ELPS27>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGilvray ID, Serghides L, Kapus A, Rotstein OD, Kain KC. Nonopsonic monocyte/macrophage phagocytosis of Plasmodium falciparum-parasitized erythrocytes: a role for CD36 in malarial clearance. Blood. 2000;96:3231–3240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LH, Baruch DI, Marsh K, Doumbo OK. The pathogenic basis of malaria. Nature. 2002;415:673–679. doi: 10.1038/415673a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash GB, O’Brien E, Gordon-Smith EC, Dormandy JA. Abnormalities in the mechanical properties of red blood cells caused by Plasmodium falciparum. Blood. 1989;74:855–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash GB, Cooke BM, Marsh K, Berendt A, Newbold C, Stuart J. Rheological analysis of the adhesive interactions of red blood cells parasitized by Plasmodium falciparum. Blood. 1992;79:798–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo P, Hundt E, Lawler J, Seed B. CD36 directly mediates cytoadherence of Plasmodium falciparum parasitized erythrocytes. Cell. 1989;58:95–101. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90406-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongponratn E, Riganti M, Harinasuta T, Bunnag D. Electron microscopic study of phagocytosis in human spleen in falciparum malaria. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1989;20:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RN, Simpson JA, Nosten F, Luxemburger C, Hkirjaroen L, ter Kuile F, et al. Factors contributing to anemia after uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:614–622. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DD, Sherwood JA, Spitalnik SL, Panton LJ, Howard RJ, Dixit VM, et al. Thrombospondin binds falciparum malaria parasitized erythrocytes and may mediate cytoadherence. Nature. 1985;318:64–66. doi: 10.1038/318064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzer B, Sodeman T, Mead ML, Contacos PG. Pitting function of the spleen in malaria: ultrastructural observations. Science. 1972;177:175–177. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4044.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow RW, Guerra CA, Noor AM, Myint HY, Hay SI. The global distribution of clinical episodes of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2005;434:214–217. doi: 10.1038/nature03342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara-Seki M. Flow around cells adhered to a microvessel wall. I. Fluid stresses and forces acting on the cells. Biorheology. 2000;37:341–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh S, Spatz J, Mills JP, Micoulet A, Dao M, Lim CT, et al. Connections between single-cell biomechanics and human disease states: gastrointestinal cancer and malaria. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourovskaia A, Figueroa-Masot X, Folch A. Differentiation-on-a-chip: a microfluidic platform for long-term cell culture studies. Lab Chip. 2005;5:14–19. doi: 10.1039/b405719h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner GD, Ly VC, Nguyen TH, Tran TH, Nguyen HP, Bethell D, et al. Systemic endothelial activation occurs in both mild and severe malaria. Correlating dermal microvascular endothelial cell phenotype and soluble cell adhesion molecules with disease severity. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1477–1487. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udeinya IJ, Schmidt JA, Aikawa M, Miller LH, Green I. Falciparum malaria-infected erythrocytes specifically bind to cultured human endothelial cells. Science. 1981;213:555–557. doi: 10.1126/science.7017935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart AD. Putative pathophysiological interactions of cytokines and phagocytic cells in severe human falciparum malaria. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:117–131. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viebig NK, Nunes MC, Scherf A, Gamain B. The human placental derived BeWo cell line: a useful model for selecting Plasmodium falciparum CSA-binding parasites. Exp Parasitol. 2006;112:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss L. The spleen in malaria: the role of barrier cells. Immunol Lett. 1990;25:165–172. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(90)90109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesides GM. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature. 2006;442:368–373. doi: 10.1038/nature05058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager P, Domingo GJ, Gerdes J. Point-of-care diagnostics for global health. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2008;10:107–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.10.061807.160524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yipp BG, Anand S, Schollaardt T, Patel KD, Looareesuwan S, Ho M. Synergism of multiple adhesion molecules in mediating cytoadherence of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to microvascular endothelial cells under flow. Blood. 2000;96:2292–2298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]