Abstract

Background

Studies of hypertension and cognition variously report adverse, null and protective associations. We evaluated evidence supporting three potential explanations for this variation: an effect of hypertension duration, an effect of age at hypertension initiation, and selection bias due to dependent censoring.

Methods

The Normative Aging Study is a prospective cohort study of men in the greater Boston area. Participants completed study visits, including hypertension assessment, every 3-5 years starting in 1961. 758 of 1284 men eligible at baseline completed cognitive assessment between 1992 and 2005; we used the mean age-adjusted cognitive test z-score from their first assessment to quantify cognition. We estimated how becoming hypertensive and increasing age at onset and duration since hypertension initiation affect cognition. We used inverse probability of censoring weights to reduce and quantify selection bias.

Results

A history of hypertension diagnosis predicted lower cognition. Increasing duration since hypertension initiation predicted lower mean cognitive z-score (-0.02 standard units per year increase [95% confidence interval= -0.04 to -0.001]), independent of age at onset. Comparing participants with and without hypertension, we observed noteworthy differences in mean cognitive score only for those with a long duration since hypertension initiation, regardless of age at onset. Age at onset was not associated with cognition independent of duration. Analyses designed to quantify selection bias suggested upward bias.

Conclusions

Previous findings of null or protective associations between hypertension and cognition likely reflect the study of persons with short duration since hypertension initiation. Selection bias may also contribute to cross-study heterogeneity.

Despite a general opinion that elevated blood pressure is related to poor or declining cognition and dementia, epidemiologic evidence is mixed. Epidemiologic studies of blood pressure and cognitive function or dementia in older adults suggest that midlife hypertension (i.e. prior to age 65) is associated with lower cognitive test scores, greater cognitive decline, and increased risk of dementia in later years.1 The association between elevated blood pressure in late life (i.e. after age 65) and cognition or dementia is less consistent; studies of late-life hypertension and cognitive function report adverse or null associations and studies of late-life hypertension and dementia report adverse, null, or even protective associations.1-3 This pattern has also been replicated within a single study population. In an East Boston cohort, researchers report a suggestive adverse association between Alzheimer disease and elevated blood pressure measured ∼13 years prior to dementia assessment among a subset of the cohort, and protective associations between Alzheimer disease and elevated blood pressure measured approximately four years prior to dementia assessment in the full cohort.4 While some studies support an adverse causal effect of elevated blood pressure in midlife on cognition, the null or protective associations between elevated late-life blood pressure and cognitive test scores or dementia suggest that hypertension at older ages may be good for cognitive status. A better understanding of this issue is crucial, given the high prevalence of hypertension in the adult population5 and the potential for preventing or treating hypertension.

We evaluated three hypotheses that may account for the age-dependent pattern observed in the literature: (1) an effect of duration of hypertension, (2) an effect of age at initiation of hypertension, or (3) selection bias due to dependent censoring.

Duration of elevated blood pressure may be important. Studies that consider hypertensive status in midlife and evaluate cognition in later life require long follow-up, and people with a diagnosis of hypertension in midlife will have had the diagnosis (and by extension, the potential for elevated blood pressure) for decades prior to cognitive assessment. Conversely, follow-up is typically shorter for studies of late-life hypertension and cognition. As the incidence and prevalence of hypertension both increase with age,5,6 many of the participants in these studies who are classified as having hypertension in late life have only had the diagnosis for a few years (and therefore have the potential for only a few years of elevated blood pressure) at the time of cognitive assessment. If many years of elevated blood pressure are necessary to adversely affect cognition, this could explain the current pattern.

Second, there may be a true age-dependent effect of hypertension on cognition. Perhaps high blood pressure is necessary to ensure adequate brain perfusion in older, but not younger, persons. Those who experience elevated blood pressure only late in life (and who comprise a large proportion of those classified as hypertensive in studies of late-life hypertension on cognition) may experience a neutral or net benefit of hypertension even at longer durations, while adverse effects of elevated blood pressure at midlife may outweigh any benefits of late-life hypertension in those who develop the condition earlier.

Third, differences in the magnitude of selection bias due to dependent censoring across studies could induce a spurious age-dependent association across studies. Poor cognition and hypertension both predict disability and death.7-10 Inability to recruit persons with hypertension and poor or declining cognition or loss to follow-up of such persons would bias the results toward a protective association (eFigure 1, http://links.lww.com/EDE/A714). However, the degree of dependent censoring, and by extension the magnitude of bias, depends on the characteristics of the cohort. Such censoring may be expected to be greater in older cohorts, which could account for the age-dependent pattern.

The current study was designed to investigate whether any or all of these hypothetical mechanisms contribute to the age-dependent pattern of association seen in the literature. We evaluated the effect of age at hypertension initiation and time between hypertension initiation and cognitive assessment, a proxy for duration of hypertension, on cognitive test performance in a cohort of men, while applying statistical methods to mitigate and quantify bias due to dependent censoring.

Methods

Study Sample

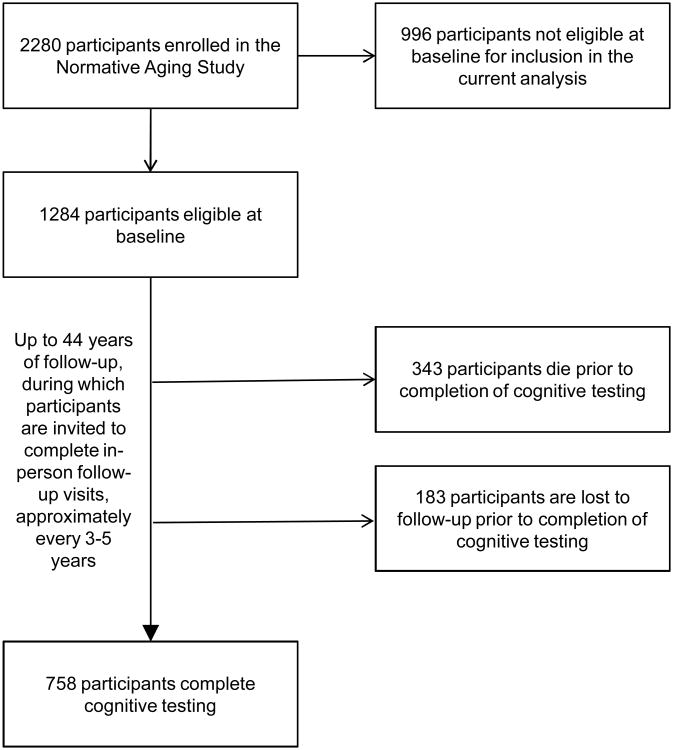

The Normative Aging Study is a longitudinal cohort study of community-dwelling men.11 2280 participants were recruited starting in 1961 and were invited to participate in in-person evaluation, including questionnaires, physical examination, and laboratory testing, every three to five years. Eligibility criteria for the current analyses required that participants self-reported white race/ethnicity, had complete data on education, and were under age 45 and free of hypertension (defined below) at enrollment (n=1284, Figure). Participants provided written informed consent, as approved by the VA Boston Healthcare System Institutional Review Board. This study was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee at Brigham and Women's Hospital.

Figure. Flow diagram of study sample selection and follow-up.

Cognitive Assessment

Between 1992 and 2005, our study participants completed an initial cognitive assessment at their regular study visit. We used data from seven cognitive tests given at this initial assessment: the Mini-Mental State Examination, a verbal fluency task (animal naming), digit span backwards, constructional praxis, immediate recall of a ten-word list, delayed recall of a ten-word list, and a pattern comparison task. All tests were from established batteries.12-15 Cognitive test scores were age-adjusted and z-transformed to yield scores in standard units, with higher scores indicating better function. Collectively, these tests assess several domains including executive function, learning, memory, attention, and visuospatial construction and perception, and provide a measure of total cognitive function. We used the mean age-adjusted cognitive test z-score for each participant as the outcome measure for this analysis.

Assessment of Hypertension

At each visit, systolic blood pressure and fifth-phase diastolic blood pressure were measured in each arm of seated participants using a standard sphygmomanometer; the average measurement across the two arms was used to characterize blood pressure. We considered participants to be hypertensive at a study visit if they reported use of anti-hypertensive medication, had a physician diagnosis of hypertension, or had a measured blood pressure above 140 mm Hg systolic or 90 mm Hg diastolic.7 Participants were considered to have a history of hypertension at the time of cognitive testing if they met the criteria for hypertension at any study visit prior to completion of cognitive testing. Age at onset of hypertension was defined as the age of the participant at the first study visit where they met criteria for hypertension. Time since hypertension initiation was calculated as the difference in age at cognitive assessment and age at onset of hypertension.

Statistical Analysis

We used marginal structural models to estimate the parameters of interest. Weighting, rather than adjustment, was used to mitigate bias due to confounding, including time-dependent confounding, and selection bias due to dependent censoring.16-18 These models analyze data only for participants who completed cognitive testing; however, data from all participants eligible at baseline were used to derive the weights (Figure). We chose marginal structural models for this analysis because our data suggest the presence of time-dependent confounding (eFigure 2, http://links.lww.com/EDE/A714).16 For example, hypertension history predicts future diabetes status, and diabetes status at a study visit predicts both future hypertension status and cognitive test scores at the end of follow-up independent of the history of diabetes, hypertension, and other covariates (data not shown).

First, we used a weighted linear model to estimate the difference in mean cognitive test score comparing those with and without a history of hypertension at cognitive testing (Equation 1, below). We used a second weighted linear model to estimate the effect of age at onset of hypertension and duration of time since hypertension initiation (Equation 2, below).

| (1) |

| (2) |

Where

k is the age at cognitive testing

I(a(k)=1) is an indicator for whether the participant has a history of hypertension at age k

cum(ā) is the number of years since hypertension initiation

k-cum(ā) is the age at initiation of hypertension

We chose to model age at onset and duration of time since hypertension initiation using linear terms, after evaluating the shape of the dose-response curve for each using penalized splines. We chose to omit an interaction term between age at onset and duration of time since hypertension initiation because two-dimensional smooth plots and Wald tests of the interaction term did not support the presence of an interaction. These models are consistent with analyses of treatment initiation. They provide estimates of the causal effects of having initiated hypertension, age at hypertension initiation, and duration since hypertension initiation, allowing for natural disease progression and treatment. In this context, the effect of age at initiation is readily interpretable. The effects of having a history of hypertension and increasing duration of time since hypertension initiation underestimate the effects we would have observed if all persons had continually elevated blood pressure after initial diagnosis, with bias toward the null increasing with the number of persons who achieve normotension during follow-up (assuming that a return to normotension confers a benefit).

We derived separate weights to control for confounding and selection bias, which were then combined (using standard formulas) to create a single weight for each participant.17 To estimate inverse probability of exposure weights, which control for confounding, we used a logistic regression model to predict the probability of being hypertensive at the next visit given the participant did not have a history of hypertension. We identified potential confounders based on expert knowledge. Covariates included in models used to derive inverse probability of exposure weights were assessed at each study visit, and include visit count (linear, squared), age (linear, squared, cubed), education (<12, 12 to <16, ≥16 years), smoking status (current, past, never, missing) and years of smoking (linear), diabetes history (yes/no), oral glucose tolerance test results (log-transformed), ≥2 alcoholic drinks/day (yes, no, missing), hypercholesterolemia (yes/no), body mass index (linear), and interactions of continuous age w visit count, oral glucose tolerance test results, ≥2 alcoholic drinks/day, and body mass index.

Two sets of inverse probability of censoring weights were derived to control for selection bias due to dependent censoring using separate logistic regression models. The first model predicted the probability of death prior to the next visit, and the second predicted the probability of non-death drop-out prior to the next visit, reflecting the two censoring mechanisms in our data.19 Given the large number of potential predictors of censoring available in our dataset, we used forward step-wise selection to choose variables for inclusion in these logistic regression models, setting the maximum number of variables chosen to the number of participants who died or dropped out divided by ten, while forcing in age, education, and blood pressure-related variables.

Characteristics updated at each study visit and included in the model to predict censoring due to death included visit count (linear), age (linear, squared, cubed), education (<12, 12 to 15, ≥16 years), history of hypertension (yes/no), current hypertension diagnosis (yes/no), elevated blood pressure (yes/no), age at hypertension initiation (linear), time since hypertension initiation (linear), systolic blood pressure (log-transformed), use of medication for hypertension (yes/no), hypercholesterolemia (yes/no), or cardiovascular disease (yes/no), current diagnosis of cancer (yes/no), ever diagnosis of myocardial infarction (yes/no) or cardiovascular disease (yes/no), age at first myocardial infarction (linear), years of employment at baseline (linear), smoking status (current, past, never, missing), years of smoking (linear), age began smoking (linear), serum hematocrit (normal/abnormal), white blood cell count (log-transformed), and cholesterol (linear, squared), height(linear), forced expiratory volume flow rate (25%-75%) in liters/minute (root-transformed, root-transformed and squared), abdominal circumference (linear, squared), and interactions between age (linear, squared) and education and between age (linear) and smoking. Characteristics updated at each study visit and chosen to predict non-death drop-out included visit count (linear), age (linear), education (<12, 12 to <16, ≥16 years), date of birth, history of hypertension (yes/no), current hypertension diagnosis (yes/no), elevated blood pressure (yes/no), age at hypertension initiation (linear), time since hypertension initiation (linear), diastolic blood pressure (linear, squared), pain medication use (yes/no), smoking status (current, past, never, missing), ≥2 alcoholic drinks/day (yes, no, missing), fasting glucose level (</≥ 100 mg/dL), serum hemoglobin (linear, squared), serum protein (linear, squared), hypercholesterolemia (yes/no), forced expiratory volume in one second in liters/minute (linear), body mass index (linear), abdominal circumference (linear), and an interaction between age and visit count.

We used the c-statistic, Hosmer-Lemeshow test, and mean of the stabilized weight as checks on the appropriateness of models used to derive weights. Additional details, including formulas, are available in the eAppendix(http://links.lww.com/EDE/A714).

To illustrate the magnitude of selection bias due to dependent censoring, we additionally report analyses using a final set of weights that do not incorporate inverse probability of censoring weights.

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, as we did not know the exact date of hypertension initiation, we used an alternate derivation for age at onset (and therefore duration of time since initiation) of hypertension – the age halfway between the last non-hypertensive and the first hypertensive study visit – to evaluate whether use of the date of the study visit as the date of initiation influenced our findings. Second, we restricted our sample to those under age 35 at enrollment to further reduce the possibility of having a selected sample (with respect to hypertension and cognition) at recruitment. Third, we looked at the association of cognition with age at onset and with duration of time since hypertension initiation among those who became hypertensive at least four years prior to cognitive assessment in order to address concerns about reverse causation. Finally, we truncated our weights at the 1st and 99th percentiles to see whether our results were driven by participants with weights at the extremes of the distribution. We used sandwich variance estimates to produce 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values for all models. All analyses were completed using SAS, version 9.2 (Cary, NC) or R, version 2.13.0 (Vienna, Austria).

Results

Characteristics of the 1284 (of 2280) participants eligible at enrollment and the 758 (59%) eligible participants who completed cognitive testing are provided in Table 1. Of those who did not complete cognitive testing, 343 had died and 183 were lost to follow-up (Figure). There was considerable variation in duration of time between hypertension initiation and cognitive testing for a given age at onset of hypertension, and vice-versa (Table 2). The mean cognitive test z-score was -0.02 (standard deviation = 0.62) for participants with a history of hypertension at cognitive testing and 0.02 (0.57) for those without.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants who were eligible at enrollment and participants who complete cognitive testing.

| Participants eligible at enrollment (n=1284) | Participants who completed cognitive testing (n=758) | |

|---|---|---|

| No. Study Visits | ||

| No. | 7894 | 5751 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.1 (2.6) | 7.6 (1.7) |

| Calendar Years of Baseline Visit | 1961 to 1970 | 1961 to 1970 |

| Calendar Years of Cognitive Testing | NA | 1992 to 2005 |

| Follow-Up Time (Years) | ||

| No. | 30,188 | 22,255 |

| Mean (SD) | 23.5 (9.7) | 29.4 (2.7) |

| Range | 0 to 43.9 | 24.5 to 43.9 |

| Age at Baseline (Years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 36.9 (5.2) | 36.7 (5.1) |

| Range | 21.8 to 45.0 | 23.1 to 45.0 |

| Age at Cognitive Testing (Years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | NA | 66.1 (5.4) |

| Range | NA | 49.7 to 80.3 |

| Years of Education at Baseline; No. (%) | ||

| <12 | 153 (12) | 83 (11) |

| 12 to <16 | 596 (46) | 349 (46) |

| ≥16 | 535 (42) | 326 (43) |

| Smoking Status at Baseline; No. (%) | ||

| Current | 282 (22) | 192 (25) |

| Past | 777 (61) | 414 (55) |

| Never | 208 (16) | 144 (19) |

| Missing | 17 (1) | 8 (1) |

| ≥2 Alcoholic Drinks/Day at Baseline; No. (%) | ||

| Yes | 136 (11) | 76 (10) |

| No | 936 (73) | 547 (72) |

| Missing | 212 (17) | 135 (18) |

| Other Baseline Characteristics; Mean (SD) | ||

| Years of Smoking Among Smokers | 16.7 (6.8) | 16.1 (6.9) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 25.7 (2.8) | 25.6 (2.6) |

| Total Cholesterol, (mg/dL) | 201.4 (44.5) | 199.8 (42.5) |

| Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (mg/dL) | 104.4 (19.3) | 104.1 (19.0) |

| History of Diabetes at Baseline; No. (%) | 2 (0%) | 1 (0) |

| Developed a History of Hypertension Before Censoring; No. (%) | 703 (55) | 515 (68) |

NA indicates not applicable

Table 2. Number of participants with a history of hypertension at cognitive testing, by categories of age at onset and duration of hypertension prior to cognitive testing.

| Duration of Time Between Hypertension Initiation and Cognitive Testing (Years) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤2.5 | 2.6–7.5 | 7.6–12.5 | 12.6–17.5 | 17.6–22.5 | 22.6–27.5 | >27.5 | Total | |

| Age at Onset of Hypertension (Years) | (n=104) | (n=125) | (n=101) | (n=77) | (n=62) | (n=37) | (n=9) | (n=515) |

| ≤37.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| 37.6 to 42.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 13 | 13 | 4 | 36 |

| 42.6 to 47.5 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 14 | 13 | 9 | 3 | 45 |

| 47.6 to 52.5 | 1 | 6 | 18 | 20 | 19 | 12 | 1 | 77 |

| 52.6 to 57.5 | 8 | 20 | 34 | 32 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 106 |

| 57.6 to 62.5 | 13 | 38 | 35 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 91 |

| 62.6 to 67.5 | 43 | 46 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98 |

| 67.6 to 72.5 | 28 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 |

| >72.5 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

C-statistics suggest that models used to derive inverse probability weights were reasonable (for hypertension, 0.79; death, 0.77; non-death drop-out, 0.75). Hosmer-Lemeshow tests did not suggest poor model fit, and the means of all stabilized weights were approximately 1.0. Additional characteristics of the weights are provided in eTable 1 (http://links.lww.com/EDE/A714).

Overall, participants who developed hypertension during follow-up had an age-adjusted mean cognitive test z-score that was 0.15 standard units lower than those who did not (95% CI= -0.26 to -0.03). In the model including terms representing both age at onset and duration of hypertension, each one year increase in duration of time since hypertension initiation was associated with a decrease in mean age-adjusted cognitive test z-score (standard unit difference per year increase = -0.02 [95%CI= -0.04 to -0.001]). Predicted differences in cognitive test scores for persons of the same age at cognitive testing between those with a given age at onset and duration of time since initiation of hypertension and those without a history of hypertension illustrate that long duration since hypertension initiation is necessary to observe noteworthy hypertension-related decrement in cognitive performance, regardless of age at onset of hypertension (Table 3). There was little evidence to support an effect of age at onset after accounting for duration of time since hypertension initiation (standard unit difference in mean age-adjusted cognitive test z-score per year increase= -0.01 [95%CI= -0.03 to 0.01]).

Table 3. Predicted difference in age-adjusted mean cognitive test z-score comparing those with hypertension withthose who never converted to hypertension by age at onset and duration of time since hypertension initiation within the range of the data.

| Duration of TimeBetween Hypertension Initiation and Cognitive Testing (Years) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Onset of Hypertension (Years) | 5 Difference (95% CI) | 10 Difference (95% CI) | 15 Difference (95% CI) | 20 Difference (95% CI) | 25 Difference (95% CI) |

| 40 | -- | -- | -0.06 (-0.28 to 0.16) | -0.16 (-0.33 to 0.00) | -0.26 (-0.42 to -0.11) |

| 45 | -- | 0.01 (-0.21 to 0.22) | -0.09 (-0.24 to 0.05) | -0.20 (-0.32 to -0.07) | -0.30 (-0.47 to -0.13) |

| 50 | 0.07 (-0.14 to 0.29) | -0.03 (-0.17 to 0.12) | -0.13 (-0.24 to -0.02) | -0.23 (-0.38 to -0.09) | -0.33 (-0.56 to -0.11) |

| 55 | 0.04 (-0.11 to 0.19) | -0.06 (-0.16 to 0.04) | -0.16 (-0.29 to -0.03) | -0.26 (-0.47 to -0.06) | -- |

| 60 | 0.01 (-0.10 to 0.12) | -0.10 (-0.22 to 0.03) | -0.20 (-0.40 to 0.00) | -- | -- |

| 65 | -0.03 (-0.16 to 0.11) | -0.13 (-0.33 to 0.07) | -- | -- | -- |

| 70 | -0.06 (-0.27 to 0.14) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

indicates outside range of the data.

In comparison with the fully weighted estimate for the effect of having a history of hypertension (-0.15 [95% CI= -0.26 to -0.03]), analyses omitting inverse probability of censoring weights resulted in an -0.11 standard unit difference in mean age-adjusted cognitive test z-score between those with and without a history of hypertension (95% CI= -0.22 to 0.003). The associations between duration of time since initiation or age at onset of hypertension and cognition in analyses omitting inverse probability of censoring weights were a -0.01 standard unit difference per year increase in time since initiation (95%CI= -0.03 to 0.006) and a -0.003 standard unit difference per year increase in age at onset (95% CI: -0.02 to 0.02), versus the previous, fully weighted estimates of -0.02 standard unit difference per year increase in duration of time since initiation (95%CI= -0.04 to -0.001) and -0.01 standard unit difference per year increase in age at onset (95%CI: -0.03 to 0.01).

Results of our sensitivity analyses were consistent with results of the primary analyses. Use of an alternate derivation for age at onset produced similar, but stronger, adverse associations for both duration of time since hypertension initiation and age at onset. Results of analyses restricted to those under age 35 at enrollment, incorporating a four-year prodromal period, or using truncated weights concur with those of our primary analyses (eTable 2, http://links.lww.com/EDE/A714).

Discussion

In line with many previous studies of hypertension and cognition, we found an adverse association between having a history of hypertension and cognitive performance. While it is difficult to quantify the magnitude of this effect in clinical terms, it appears to be of substantive importance. Although an imperfect comparator, our -0.15 standard unit difference in age-adjusted cognitive test score comparing those with and without a history of hypertension at the time of cognitive testing is roughly similar to the difference in cognitive test scores prior to age adjustment between people 5 years different in age in our data. To provide additional context, in a cohort of female nurses that used a cognitive battery including several of the same tests, the difference in baseline mean cognitive test z-score comparing APOE e3/e3 to e3/e4 carriers was 0.09, or about two-thirds the difference we found for hypertension.20

Our analyses support the hypothesis that there is an adverse effect of increasing time since hypertension initiation – and therefore of increasing duration of elevated blood pressure – on cognition. Furthermore, we were able to predict poor cognitive test performance relative to persons without a history of hypertension only among those with a long time between hypertension initiation and cognitive testing. These findings suggest that studies of persons with short duration since hypertension initiation at cognitive assessment may fail to detect an adverse association because the majority of persons classified as hypertensive have not had sufficient duration of elevated blood pressure to produce measureable cognitive decline. As many studies of late-life hypertension fit this description while studies of midlife hypertension generally do not, this may account in part for the divergence of findings between studies of late-life and midlife hypertension on cognition.

Our results do not support our second hypothesis, that later-onset hypertension or hypertension at later ages is protective. We conclude that differences in the distribution of age at onset of hypertension across studies, independent of the associated difference in duration of hypertension prior to cognitive assessment, are unlikely to contribute to heterogeneity of past findings.

Finally, our analyses designed to quantify the magnitude and direction of bias due to dependent censoring suggest a bias towards a protective association. However, given the wide and overlapping confidence intervals for each set of effect estimates, we cannot exclude the possibility that the observed difference between analyses with and without inverse probability of censoring weights may be due to chance. If the true magnitude of bias is similar to the difference in our point estimates, then selection bias has the potential to change study conclusions. Therefore, differences in the degree of selection bias across studies may also contribute to the inconsistencies observed across prior epidemiologic studies of blood pressure and cognition.

We recognize the limitations of our study. Our analysis does not directly quantify the effect of blood pressure elevation on cognition. However, such effects would be expected to be stronger than our effect estimates. We were also unable to consider alternate characterizations of blood pressure. We used a standard clinical definition of hypertension in order to be consistent with other reported analyses, and because additional data beyond the scope of this study would be required to create reliable measures of association with continuous exposure metrics. Likewise, we were unable to quantify the impact of anti-hypertensive medication use, level of blood pressure control, or blood pressure trajectory. Such analyses would be of interest but were beyond the scope of this study. While we were able to consider many potential confounders, we did not have longitudinal information on diet or physical activity, and so our estimates may be subject to residual confounding if these factors play an important role in the advent of cognitive change independent of promotion of hypertension or diabetes. Misclassification of the timing of emergence of hypertension is likely; however, our results were consistent in sensitivity analyses designed to address this limitation. Misclassification of cognitive status is also likely, but it is addressed in part by use of a summary measure of cognition; such misclassification would make detection of a true effect more difficult, but would not bias results. While our outcome was cognitive test performance, we believe our conclusions apply broadly to the literature on hypertension and cognition, including studies considering dementia as the outcome. We used a summary measure of cognition to allow comparison to studies of both cognitive function and dementia, and note that dementia diagnosis is closely tied to cognitive performance, as it is based on a decline in cognitive function from previous levels that interferes with activities of daily living.21 While our study included only men, we have no reason to expect that our results are not generalizable to women. Finally, our findings are valid only within the ranges of age at onset and of time since hypertension initiation found in our data.

Our study also has several strengths. We had 25 to 44 years of follow-up with study visits planned every three to five years, allowing us to determine age at onset and time since hypertension initiation. We also had considerable variation in age at onset and time since hypertension initiation, allowing effect estimates despite high correlation between these variables. We were able to restrict our sample to participants under age 45 at enrollment, thus decreasing the likelihood that we began with a selected sample with respect to hypertension and cognition, as the rate of cardiovascular-related mortality is low prior to this age.22 Finally, we have information about censored participants, allowing us to address selection bias due to dependent censoring.

Our finding that having a history of hypertension predicts relatively poor cognitive performance is consistent with several prior studies of hypertension diagnosis and cognitive performance,23,24 cognitive decline,25-27 and cognitive impairment or dementia.28-31 However, we believe that this study is the first to consider support for hypotheses involving age at onset and duration simultaneously. Previous studies of blood pressure and cognition have generally considered one or the other. For example, prior studies have evaluated differences in association by age at baseline/assessment of blood pressure. In the Rotterdam and Leiden 85-plus Study, despite 11 years of follow-up in each group, researchers found no association between blood pressure and cognitive function in those ages 55-64 at baseline, an adverse association in those ages 65-74 at baseline, and a protective association in those over 75 at baseline.3 Similarly, data from the Adult Changes in Thought Study suggested an adverse association between elevated blood pressure and dementia only in those under age 75 at baseline.32 While these studies seemingly support an association between cognition and age at onset of hypertension, their results may also be accounted for by shorter duration of hypertension and increased selection bias due to dependent censoring in older age groups. Similarly, several studies have considered duration of hypertension without considering age at onset. For example, increasing duration of anti-hypertensive drug use predicted reduced risk of cognitive decline or dementia in hypertensive men from the Honolulu Asia Aging Study33 and in a medical-record based cohort in California34; higher average blood pressure and a greater proportion of study visits where participants were hypertensive predicted worse cognitive function in the Framingham Heart Study among those not taking anti-hypertensive medications two years prior to cognitive assessment35; and participants from the Epidemiology of Vascular Aging Study who had consistently elevated blood pressure at study visits two years apart were more likely to exhibit demonstrable cognitive decline than those who returned to normotension at the second visit.26

Our analyses support the hypothesis that cumulative hypertension-related insult leads to cognitive impairment, and are consistent with reports of slow, cumulative accumulation of amyloid-beta starting approximately 20 years prior to dementia diagnosis.36 Our results do not support the idea that hypertension at later ages is protective. High blood pressure can cause cerebral atherosclerosis or ischemic white matter lesions and silent infarcts, which adversely affect brain function37 and may promote formation of neuritic plaques.38 Future research must address whether anti-hypertensive medication use or blood pressure control successfully reduce risk in those with long duration of hypertension and whether hypotension (including timing of hypotension) also has adverse consequences for cognition.39

Our findings have implications for how we conduct and interpret epidemiologic studies of age-related disorders. While expensive and time-consuming, long-term, prospective cohort studies are needed to obtain the necessary data to address selection bias. Even short-term follow-up of older populations with little loss to follow-up may produce biased results due to selected enrollment. We must also think carefully about how an exposure is likely to be causally related to the outcome under study, especially in terms of timing and duration of exposure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Allan Just and John Ji for comments on an early version of the eAppendix.

Sources of Funding: The Normative Aging Study is supported by the Cooperative Studies Program/ERIC of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and is a component of the Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center (MAVERIC). MCP is funded by an NIA F31 Predoctoral Training Grant (F31 AG038233) and this work was supported by NIH R01ES005257. Dr. Sparrow is the recipient of a Research Career Scientist award from the VA Clinical Science Research & Development Service. The researchers are independent of the study funders. The funding sources had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

SDC Supplemental digital content is available through direct URL citations in the HTML and PDF versions of this article (www.epidem.com). This content is not peer-reviewed or copy-edited; it is the sole responsibility of the author

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Qiu C, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. The age-dependent relation of blood pressure to cognitive function and dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2005 Aug;4(8):487–499. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Power MC, Weuve J, Gagne JJ, McQueen M, Viswanathan A, Blacker D. The association between blood pressure and incident Alzheimer disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2011 Sep;22(5):646–659. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31822708b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Euser SM, van Bemmel T, Schram MT, et al. The effect of age on the association between blood pressure and cognitive function later in life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009 Jul;57(7):1232–1237. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris MC, Scherr PA, Hebert LE, Glynn RJ, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Association of incident Alzheimer disease and blood pressure measured from 13 years before to 2 years after diagnosis in a large community study. Arch Neurol. 2001 Oct;58(10):1640–1646. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.10.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ong KL, Cheung BMY, Man YB, Lau CP, Lam KSL. Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension Among United States Adults 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2007;49(1):69–75. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252676.46043.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dannenberg AL, Garrison RJ, Kannel WB. Incidence of hypertension in the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health. 1988 Jun;78(6):676–679. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.6.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003 May 21;289(19):2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002 Dec 14;360(9349):1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Euser SM, Schram MT, Hofman A, Westendorp RG, Breteler MM. Measuring cognitive function with age: the influence of selection by health and survival. Epidemiology. 2008 May;19(3):440–447. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816a1d31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bassuk SS, Wypij D, Berkman LF. Cognitive impairment and mortality in the community-dwelling elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2000 Apr 1;151(7):676–688. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell B, Rose CL, Damon A. The Normative Aging Study: An interdisciplinary and longitudinal study of health and aging. Aging and Human Development. 1972;3:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1989 Sep;39(9):1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R) San Antonio, Texas: The Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Letz R. NES2 User's Manual (version 4.4) Winchester, MA: Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beery KE, Buktenica NA. Developmental Test of Visual Motor Integration. Modern Curriculum Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robins JM, Hernán MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000 Sep;11(5):550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernán MA, Brumback B, Robins JM. Marginal structural models to estimate the causal effect of zidovudine on the survival of HIV-positive men. Epidemiology. 2000 Sep;11(5):561–570. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi HK, Hernán MA, Seeger JD, Robins JM, Wolfe F. Methotrexate and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. The Lancet. 2002;359(9313):1173–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08213-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weuve J, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Glymour MM, et al. Accounting for bias due to selective attrition: the example of smoking and cognitive decline. Epidemiology. 2012 Jan;23(1):119–128. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318230e861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang JH, Logroscino G, De Vivo I, Hunter D, Grodstein F. Apolipoprotein E, cardiovascular disease and cognitive function in aging women. Neurobiol Aging. 2005 Apr;26(4):475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Center for Disease Control National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System. LCWK1. [Accessed 3/6/2011];Deaths, percent of total deaths, and death rates for the 15 leading causes of death in 5-year age groups, by race and sex: United States, 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/LCWK1_2007.pdf.

- 23.Elias MF, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Cobb J, White LR. Untreated Blood Pressure Level Is Inversely Related to Cognitive Functioning: The Framingham Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1993 Sep 15;138(6):353–364. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elias MF, Elias PK, Sullivan LM, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB. Lower cognitive function in the presence of obesity and hypertension: the Framingham heart study. International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders. 2003;27(2):260. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.802225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knopman D, Boland LL, Mosley T, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline in middle-aged adults. Neurology. 2001 Jan 9;56(1):42–48. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tzourio C, Dufouil C, Ducimetiere P, Alperovitch A. Cognitive decline in individuals with high blood pressure: a longitudinal study in the elderly. EVA Study Group. Epidemiology of Vascular Aging. Neurology. 1999 Dec 10;53(9):1948–1952. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piguet O, Grayson DA, Creasey H, et al. Vascular risk factors, cognition and dementia incidence over 6 years in the Sydney Older Persons Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2003 May-Jun;22(3):165–171. doi: 10.1159/000069886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart R, Richards M, Brayute C, Mann A. Vascular Risk and Cognitive Impairment in an Older, British, African-Caribbean Population. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49(3):263–269. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4930263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Launer LJ, Ross GW, Petrovitch H, et al. Midlife blood pressure and dementia: the Honolulu-Asia aging study. Neurobiol Aging. 2000 Jan-Feb;21(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu C, Zhou D, Wen C, Zhang L, Como P, Qiao Y. Relationship between blood pressure and Alzheimer's disease in Linxian County, China. Life Sci. 2003 Jan 24;72(10):1125–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitmer RA, Sidney S, Selby J, Johnston SC, Yaffe K. Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and risk of dementia in late life. Neurology. 2005 Jan 25;64(2):277–281. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149519.47454.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li G, Rhew IC, Shofer JB, et al. Age-varying association between blood pressure and risk of dementia in those aged 65 and older: a community-based prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007 Aug;55(8):1161–1167. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peila R, White LR, Masaki K, Petrovitch H, Launer LJ. Reducing the risk of dementia: efficacy of long-term treatment of hypertension. Stroke. 2006 May;37(5):1165–1170. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217653.01615.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haag MD, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM, Stricker BH. Duration of antihypertensive drug use and risk of dementia: A prospective cohort study. Neurology. 2009 May 19;72(20):1727–1734. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000345062.86148.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farmer ME, Kittner SJ, Abbott RD, Wolz MM, Wolf PA, White LR. Longitudinally measured blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, and cognitive performance: the Framingham Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(5):475–480. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90136-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, et al. Amyloid beta deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer's disease: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Neurology. 2013;12(4):357–367. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skoog I, Gustafson D. Update on hypertension and Alzheimer's disease. Neurol Res. 2006 Sep;28(6):605–611. doi: 10.1179/016164106X130506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iadecola C, Gorelick PB. Converging pathogenic mechanisms in vascular and neurodegenerative dementia. Stroke. 2003 Feb;34(2):335–337. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000054050.51530.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Birns J, Markus H, Kalra L. Blood pressure reduction for vascular risk: is there a price to be paid? Stroke. 2005 Jun;36(6):1308–1313. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000165901.38039.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.