Abstract

In the aftermath of a decade-long Maoist civil war in Nepal and the recent relocation of thousands of Bhutanese refugees from Nepal to Western countries, there has been rapid growth of mental health and psychosocial support programs, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment, for Nepalis and ethnic Nepali Bhutanese. This medical anthropology study describes the process of identifying Nepali idioms of distress and local ethnopsychology and ethnophysiology models that promote effective communication about psychological trauma in a manner that minimizes stigma for service users. Psychological trauma is shown to be a multi-faceted concept that has no single linguistic corollary in the Nepali study population. Respondents articulated different categories of psychological trauma idioms in relation to impact upon the heart-mind, brain-mind, body, spirit, and social status, with differences in perceived types of traumatic events, symptom sets, emotion clusters, and vulnerability. Trauma survivors felt blamed for experiencing negative events, which were seen as karma transmitting past life sins or family member sins into personal loss. Some families were reluctant to seek care for psychological trauma because of the stigma of revealing this bad karma. In addition, idioms related to brain-mind dysfunction contributed to stigma while heart-mind distress was a socially acceptable reason for seeking treatment. Different categories of trauma idioms support the need for multidisciplinary treatment with multiple points of service entry.

Keywords: Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), trauma, psychosocial, stigma, Nepal

Introduction

“PTSD does not exist in Nepal,” declared an expatriate humanitarian worker in Kathmandu. This statement can imply that the seventeen symptoms comprising the current diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) cannot be identified among Nepalis. Another interpretation is that a PTSD-like construct is not present in local languages and conceptualizations of suffering, emotions, behavior, and perception.

If the person were referring to the first interpretation—that one could not find the symptoms comprising PTSD among Nepalis—then he would have been wrong. Marsella and colleagues have commented, “We are not aware of any ethnocultural cohort in which PTSD could not be diagnosed, although prevalence rates have varied considerably from one setting to another” (Marsella, et al. 1996:531). Similarly, every study in Nepal that has looked for PTSD has found it: 53 percent prevalence among internally displaced persons (Thapa and Hauff 2005), 55 percent among child soldiers (Kohrt, et al. 2008), 60 percent among torture survivors (Tol, et al. 2007), and 14 percent among Bhutanese refugee survivors of torture (Shrestha, et al. 1998). However, the mere identification of PTSD symptoms in a population has questionable therapeutic utility. Observation of PTSD symptoms does not, in-and-of-itself, immediately reveal optimal clinical care or other intervention. Understanding personal or social meanings and experiences of distress associated with traumatic events also are necessary for effective treatment.

The second interpretation of the humanitarian workers’ statement has greater potential to be of value to those in the healing professions. The question of whether or not a local construct for PTSD or psychological trauma exists is crucial to identify persons who are locally recognized as needing support, employ existing healing practices, understand the social significance for persons labeled locally as having psychological trauma, and determine if persons with the label are stigmatized and deprived of care. All of these factors become important when considering how to alleviate suffering for survivors of traumatic events. Hinton and Lewis-Fernandez (in press) have identified seven forms of clinical relevance for idioms of distress: indicators of psychopathology, indicators of risk for destructive behavior, indicators of life distress, indicators of past exposure to trauma, indicators of psychosocial functioning, causes of distress, and targets for therapeutic intervention.

Compared to the number of epidemiological studies of PTSD, there is a dearth of studies of these local conceptual frameworks influencing diagnosis and treatment psychological trauma in non-Western settings (Lemelson, et al. 2007). Such studies are not trivial. When trauma-healing programs do not address local psychological frameworks, there is risk of unintended consequences such as degeneration of local support systems, pathologizing and stigmatizing already vulnerable individuals, and shifting resources from social and structural interventions (Argenti-Pillen 2003; Kleinman and Desjarlais 1995; Summerfield 1999; 2002). Proper identification and understanding of local concepts and idioms not only reduces risk of harm, it also enables improved treatment such as selection of culturally-appropriate therapeutic interventions (Hinton and Lewis-Fernandez in press).

Investigating the presence of local PTSD-like constructs within non-Western frameworks of emotions, behavior, and perception is additionally important because of the history of changing psychological trauma concepts within Western culture. Young’s (1995) description of the evolution of the category of PTSD in Western culture reveals that PTSD was not a universal and ever-present way of framing specific experiences and psychological consequences. Rather, PTSD is only the most recent incarnation of describing, identifying, and treating a manifestation of psychological suffering in Western ethnopsychiatry. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) diagnostic construct of PTSD, which only first appeared in 1980, is not simply the progression of scientific knowledge, but rather the confluence of political, economic, legal, and medical institutional forces.1 Furthermore, the release from military duties and compensation of those psychological affected by combat exposure have played a significant role in PTSD’s current place in Western psychiatric nosology (McNally 2003; Summerfield 2001; Young 1995).

Since the DSM codification of PTSD, trauma psychiatry has burgeoned and extended into work with non-Western populations. In the 1980s, mental health researchers began to use the PTSD label in their work with Southeast Asian refugees (Kinzie, et al. 1990; Mollica, et al. 1987; 1990). PTSD epidemiological studies now appear standard practice in settings of war and natural disasters as illustrated by the numerous Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) studies documenting widespread PTSD, depression, and other mental health problems in Bosnia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Burma, and Thailand (Lopes Cardozo, et al. 2000; 2003; 2004a; 2004b; Thienkrua, et al. 2006). And psychological trauma intervention programs are now commonplace ranging from targeted clinical interventions to psychosocial programs for large numbers of affected populations (Bass, et al. 2006; Bolton, et al. 2003; 2007; Jordans, et al. 2009; Layne, et al. 2000; Mohlen, et al. 2005; Neuner, et al. 2008; Tol, et al. 2008; Verdeli, et al. 2008).

One explanation for the global proliferation of PTSD as a way of framing suffering is that it is a useful lens in many settings to identify those in need of care and to select types of intervention goals. For example, Tol and colleagues (2007) have shown that PTSD has a direct relationship with severity of disability among torture survivors in Nepal. Another argument for the spread of the PTSD trope is legal advocacy for survivors of human rights violations. PTSD has been used as medical and scientific evidence of human rights violations (Physicians for Human Rights 1996; 2001; 2008); diagnoses of PTSD is evidence that an individuals rights have been infringed upon through torture and other forms of political violence. In the political asylum system, PTSD is nearly requisite as “evidence” of torture (Bracken, et al. 1995; Silove 2002; Smith Fawzi, et al. 1997; Summerfield 1999).

Drawing attention to the psychological suffering of specific groups also is used to mobilize funding for non-governmental and humanitarian organizations. Breslau (2004) in a special issue of Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry (Vol, 28, Iss 2) on the “Cultures of Trauma” critiques how researchers, humanitarian aid workers, and local political forces dictate the application of the PTSD label. He claims applying PTSD labels in non-Western settings reflects the politics of humanitarian aid and local political forces attending to the global resource procurement. Breslau argues, for example, that research into the prevalence of PTSD among Bhutanese refugees in Nepal (Shrestha, et al. 1998) is a political endeavor, which by highlighting torture misses the broader suffering in refugee camps. This all results from the nature of medical labels tied to privileged resources and spotlighted by the humanitarian community.2 Ultimately, what has been missing in many of these debates for or against the use of the PTSD label is the relation between the psychiatric category and local experience of distress. Without research on local idioms and frames of understanding trauma, one cannot effectively assess how importing or rejecting the PTSD label impacts well-being, treatment seeking, and stigma.

Idioms of distress, ethnopsychology, ethnophysiology, and stigma

Nichter (1981) defines idiom of distress as “an adaptive response or attempt to resolve a pathological situation in a culturally meaningful way.” These idioms can include somatic complaints, possession, and other culturally significant experiences. Idioms of distress typically necessitate culturally prescribed healing and resolution. Idioms of distress related to frightening experiences include susto in Latin America (Rubel, et al. 1984), kesambet in Bali (Wikan 1989), rus in Micronesia (Lutz 1988), rlung in Tibetan medicine (Clifford 1990), yardargaa in Mongolia (Kohrt, et al. 2004), and soul loss in many cultures. In Thailand, lom, wuup, and rook klua lai tai are idioms representing cultural conceptualization associated with panic (Udomratn and Hinton 2009). Hinton and Lewis-Fernandez (in press) describe a range of anxiety-related idioms of distress in Cambodian and Caribbean Latino cases. Bolton (2001), employing a constellation of methods, indentified a number of local idioms that clustered into a “mental trauma” syndrome comprising symptoms of PTSD, depression, and other local idioms in Rwanda.

The limitation of idioms of distress is they may easily become a vocabulary list without a cohesive framework detailing significance of these terms and how they fit into a broader understanding of suffering and wellbeing in a given cultural context. One solution to this is conducting rich ethnography as exemplified by Wikan’s (1989; 1990) work on the term kesambet, which positions the fright idiom within broader expectations of the self-expression, emotions, and social relations. Her ethnographic work thus places the idiom within an ethnopsychological framework of understanding life and well-being. White (1992) defines ethnopsychology as the study of how individuals within a cultural group conceptualize the self, emotions, human nature, motivation, personality, and the interpretation of experience. It is a local lay psychology used to understand experience.

A complement of ethnopsychology is ethnophysiology. Hinton and Hinton (2002) describe ethnophysiology as “the culturally-guided apperception of the mind/body rather than actual biological differences,” and they provide examples of the hydraulic model of anger in Western culture and the pneumatic model of wind to explain panic in Cambodian culture. Thus, the way a cultural group interprets experience is related to how the group conceptualizes the body and its processes. Hinton and colleagues (2006) find that cultural concepts related to the mechanisms of mental and bodily events contribute to the types and experiences of anxiety disorders. Young’s (1976) work in Ethiopia describes the experience of depression as an overheating problem related to the heart’s control of jimat (cords) that move and motivate the body. Much of Tibetan, Mongolian, and Chinese concepts of mental health can be understood in terms of the humoral energies: rlung, khii, and qi, respectively (Clifford 1990; Janes 1999; Kohrt, et al. 2004).

Among the Mandinka, Fox (2003) identifies four post-trauma syndromes, two of which are disorders of the heart, one affects the mind, and the last affects the brain. These syndromes operate cumulatively with fear leading to disturbance of the heart. If the heart problems are severe, this leads to dysfunction in the mind and ultimately the brain. Ethnopsychology helps to reorient understandings of traumatic events. Kenny (1996) using the example of susto suggests that cultural conceptualization and understanding of the self determine which types of events are considered misfortune.

Ethnophysiological understandings have important implications for intervention as well. Hinton and colleagues (2009b) outline a framework for “concentric ontology security” explaining how interventions can engage different elements of the self depending on the presentation and primary complaints of the individuals, specifically in relation to nightmares.

Idioms of distress reflect and influence the stigma associated with illness. Stigma worsens the experience of an illness and often leads to lack of access to care, social isolation, and internalized feelings of shame, inferiority, and fatalism (Weiss, et al. 2006). For some conditions, the impact of stigma may be more devastating than the condition itself. Stigma is understudied in relation to PTSD in any cultural setting. For example, both HIV and PTSD are relatively new diagnostic entities introduced to medicine in the early 1980s. Both have approximately 13,000 journal publications (Medline search, 14 Feb 09). However, whereas there are 199 publications with ‘HIV’ and ‘stigma’ in the title, there is only one with ‘PTSD’ and ‘stigma’ in the title. Summerfield’s (2001) comment exemplifies this conception of PTSD not being stigmatized: “[it is] rare to find a psychiatric diagnosis that anyone liked to have but post-traumatic stress disorder was one.”

Despite a poverty of stigma literature related to PTSD in Western cultural settings, one cannot assume that psychological trauma is not stigmatized in non-Western contexts. In Cambodia, French (1994) describes the difficulty mobilizing support for amputees injured by landmines. The trauma resulting in amputation is seen as the result of poor karma, the sins of an individual in past lives. Similarly, Miller’s (2009) film Unholy Ground dramatically demonstrates how traumatic experiences are seen as an individual’s fate transmitted through karma. Therefore, one of the objectives of this study is to examine the meaning of trauma idioms and perceived causation in relation to assess the relationship of psychological trauma with stigma.

Psychological trauma in Nepal

The timing of research on local psychological trauma concepts is particularly important in Nepal. The country recently emerged from a decade-long civil war that resulted in the death of 14,000 people, thousands of disappearances, the displacement of over 150,000 people, the conscription of greater than 10,000 children into armed groups, and greater than 100,000 incidences of torture (Human Rights Watch 2007; INSEC 2008; Singh, et al. 2007; Tol, et al. 2010). In response to this, psychosocial programming has grown rapidly to address a putative burden of psychological trauma (Kohrt 2006). In addition, thousands of ethnic Nepali Bhutanese refugees, who are survivors of political violence, are emigrating from Nepal into the United States where they will encounter a medical system in which PTSD is a dominant clinical trope. A recent systematic multi-disciplinary review of psychosocial, mental health, and political violence literature in Nepal revealed that the dearth of social science understandings of trauma is a major impairment to epidemiological studies and intervention for Nepalis and ethnic Nepali Bhutanese refugees (Tol, et al. 2010).

Previously, research on idioms of distress in Nepal has shown that jham-jham (numbness and tingling) and gyastrik (dyspepsia) are common complaints associated with psychological distress particularly depression (Kohrt, et al. 2005; 2007); however, the idioms are not interchangeable with a specific psychiatric disorder. Sharma and van Ommeren (1998) have catalogued idioms of distress among ethnic Nepali Bhutanese refugees in Nepal by drawing upon clinical experiences and case note surveys. Their list includes dukha laagyo (sadness), dar laagyo (fear), jharko laagyo (irritation), metaphors in relation to being uprooted from one’s homeland, and somatic complaints such as jiu sukera gayo (drying of the body) and kat kat khanchha (tingling and burning sensations). All of these idioms overlap with psychological trauma, but none exemplifies one-to-one synonymy with PTSD.

Ethnopsychological/ethnophysiological models of the self have been outlined for Nepali frameworks of mind-body relations (Kohrt and Harper 2008). In Nepal, the self is considered an assemblage of the man (heart-mind), dimaag (brain-mind), jiu/saarir (corporeal body), saato/atma (spirit/soul), and ijjat (social status/honor), all of which are connected with samaaj (the social world). Within this ethnophysiological framework, afflictions of the brain-mind are highly stigmatized. To date, research has not examined the interplay of idioms, these ethnopsychological models, and psychological trauma.

This paper addresses this gap in the research through an exploration of local constructs of psychological trauma, Nepali idioms of distress, and vulnerability to suffering. Nepali ethnopsychology and ethnophysiology provide schemata on which to formulate employing idioms in intervention, with attention to stigma reduction and prevention. The findings are incorporated into recommendations for humanitarian psychosocial workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, and other professionals in the mental health and humanitarian fields.

Methods

This study was conducted in Nepal using semi-structured interviews, free-lists, comparison tasks, and observant participation to identify types of events considered traumatic, idioms of distress related to these traumatic events, emotions associated with psychological trauma, and perceptions of causation and vulnerability related to traumatic events. All participants were Nepalis. The first author and a Nepali research assistant conducted all interviews in Nepali. All participants completed an informed consent form. The study was approved by Emory University Institutional Review Board and the Nepal Health Research Council.

Free-list and emotion comparison tasks were conducted in 2005. The sample composition for the research tasks was limited to persons residing in Kathmandu because it was unfeasible to travel in rural areas during the time of the People’s War, which did not conclude until the end of 2006. Thirty-five individuals participated in the free-list and emotion questionnaire portion of the study. Thirty-three participants had complete data for emotion comprehension ranking, 32 for emotion-term similarity analysis, and 30 for free lists. The sample included nineteen women and sixteen men, including eighteen Newar, eight high-caste Hindu, four low-caste Hindu, and five from other ethnic groups (Gurung, Magar, Rai, Tamang). Twenty were married, and fifteen were single. Age ranged from 18 to 72 years, with a mean of 33 years. Education level ranged from 0–18 years, with a mean of 10 years (School Leaving Certificate (SLC)-pass). This sample was selected for heterogeneity of ethnicity, age, and level of education to allow for an assessment of terms and concepts that were mutually intelligible and salient across Nepali demographic groups. All participants completed the surveys in Nepali regardless of their ethno-linguistic group. For participants who spoke another ethnic language, such as Newar or Magar, we inquired about their proficiency in Nepali. All of these respondents said they had been educated in Nepali and that they were as proficient or more proficient in Nepali than in their ethnic language.

The survey comprising free lists and an emotion questionnaire were administered to the lay public participants to identity local concepts of psychological trauma. In free list tasks, participants were asked to list types of traumatic events, the effects of traumatic events on one’s life, terms used to describe suffering and traumatic events (idioms of distress), emotions associated with trauma, and gender differences in the impact of trauma. The emotion questionnaire, which included comprehension ranking and dyadic comparisons, was administered to produce a general model of similarity and understanding of terms identified in the free list tasks. This enabled us to identify commonalities of understanding to complement the idiosyncratic individualized responses provided in free-lists and semi-structured interviews. The emotion questionnaire includes a list of emotions derived from free lists. To identify how confidently people understood emotion terms, participants rated emotion terms on a scale of one to five: five signifying “I completely understand the emotion term,” and one signifying “I completely do not understand the term.” Intermediate numbers represent degrees of partial understanding.

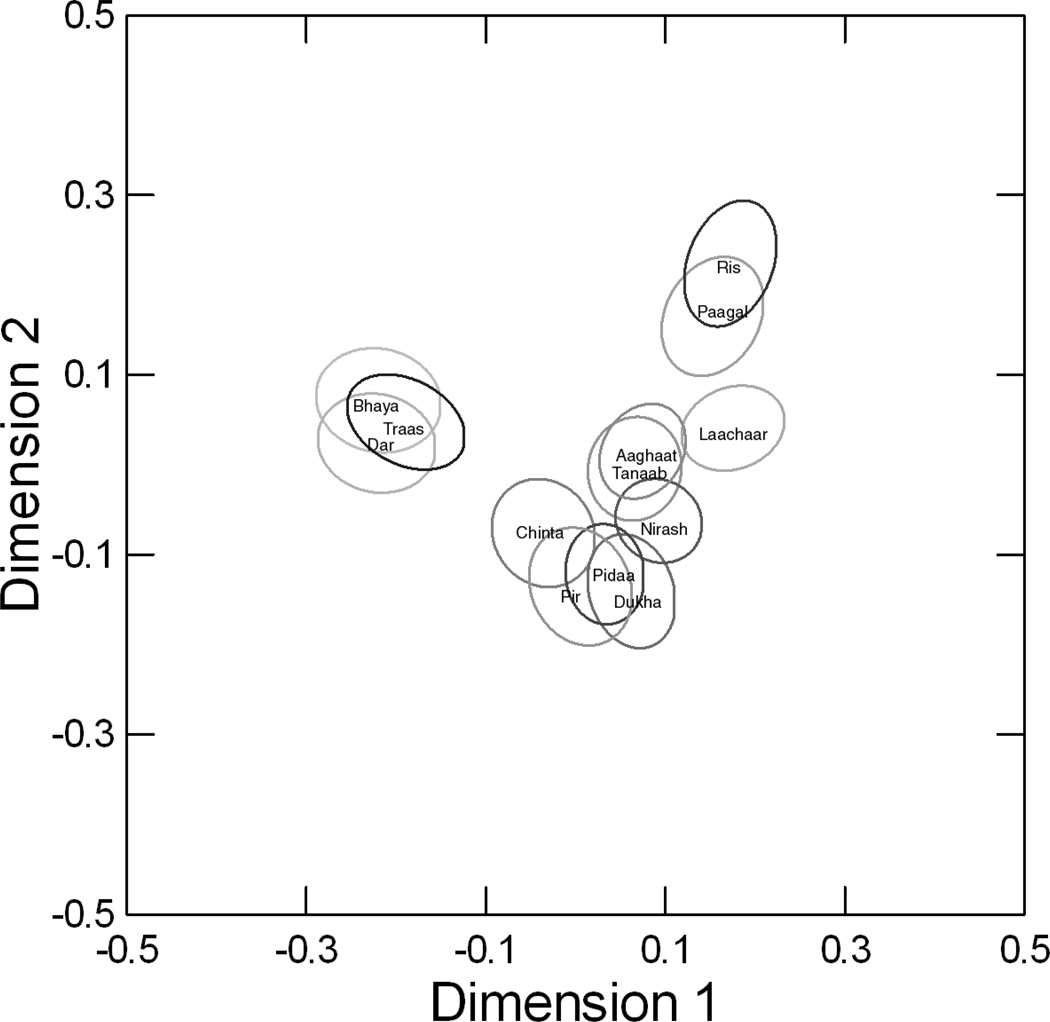

After rating their level of understanding of emotion terms, participants rated similarity among emotion term pairs to determine the conceptual similarity. To assess overall consensus on these ratings, we fit a cultural consensus model using an ordinal data type in UCINET 6 (Hruschka, et al. 2008). We used correspondence analysis to represent visually the conceptual similarity between trauma-related emotion terms in a two-dimensional space (Moore, et al. 1999; Romney, et al. 1997; 2000). In such a graph, those items that participants consistently rated as more similar are closer together in the graph. In the graph, 95% confidence ellipses reflect the certainty about each emotion term’s average location in the two-dimensional space (SYSTAT 2007).

Semi-structured interviews were conducted to gain more in-depth information on concepts of psychological trauma. This was done with practitioners to elicit narratives of care, the practitioners’ beliefs surrounding psychological trauma, and their perceptions of clients’ beliefs and attitudes. Semi-structured interviews with clients were used to understand the traumatic events, models of causation, psychological and social sequelae, and terminology used to describe the event and related emotions. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 32 individuals from 18 organizations involved in psychosocial programs. The organization participants included program administrators, counselors, other health professionals, and clients. Semi-structured interviews also were conducted with religious leaders regarding causality of traumatic events. Semi-structured interviews lasted approximately two hours. Semi-structured interviews were conducted in Kathmandu and rural areas of Western Nepal from 2005–2008. Observant participant was conducted in Nepali nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and clinical health settings in both Kathmandu and rural areas from 2006 through 2008. Observant participation was used to identify language of clinical discourse, which may not have been reported in individualized interviews and free list tasks. Observant participation also elucidated common presenting symptoms and referral patterns.

Findings

Traumatic Events

Participants were asked a range of questions to elicit categories of traumatic events such as (i) the worst events that happen in people’s lives, (ii) the worst events they have heard about through conversations with others, television, radio, news, and other media, and (iii) other events that dramatically alter a person’s life in negative ways. Probes included violence, accidents, natural and man-made disasters, and other threats to life.

Four general themes dominated the categories of events described. (i) Counselors, program administrators, and other health professionals focused on events involving a threat to one’s life or a family member's life. (ii) Clients placed more attention on chronic, ongoing events that impair livelihood, specifically failure or lack of success in specific domains of life. (iii) Spiritual and supernatural events were considered major traumatic events. (iv) Lastly, conflict-related events featured prominently; clients of one NGO felt that trauma only resulted from political violence.

Threat to life and limb

Mental health professionals endorsed a range of events related to loss of life and well-being including domestic violence, road accidents, marital rape, burns and fires, plane crashes, snake bites, falling from heights, animal attacks, witnessing accidents or violence, and death of a loved one. Physical illness, even without the threat of death, was related to psychological trauma. Physical wounds were thought to cause suffering and impairment in life. Major diseases like HIV/AIDS and cancer were thought to be traumatic. Respondents stated that drugs and alcohol can cause mental trauma, and traumatized people are more likely to drink alcohol.

Both male and female participants reported that the loss of a husband or son causes psychological trauma for women, but participants did not report the converse of losing a wife or daughter as traumatic for men. This gender difference was explained in part by the restrictions placed upon widows versus widowers (Bennett 1983; Kohrt and Worthman 2009). Widows cannot own property or remarry. Thus, they suffer significant livelihood instability. In contrast, widowers are able to maintain their wealth and property and free to remarry after losing their wives.

Failure to meet expectations

The majority of clients responded to inquiries about the worst experience in life as those events where “reality does not meet expectations.” Failed expectations in life domains included being unsuccessful in love, failing the School Leaving Certificate (SLC) exams at the end of 10th grade, major loss in business, unemployment, poverty, and generally not being satisfied in one’s desires. Too much ambition or too high expectations caused suffering in one’s life. If someone works too hard, he/she will suffer. For those suffering from failure in some area of life, it was recommended to not think about it or “forget it.” For women, central issues are producing male children and maintaining good relations among household members. For men, being unsuccessful in professional life or having one’s social status damaged are examples of the most negative experiences in life.

Men returning from work in Persian Gulf countries reported that they did return at the level of success and prosperity for which they had hoped; they identified this as the worst experience of their lives. These migrant workers had intended to return home as wealthy businessmen. However, they often found that they had been deceived by international manpower agencies, and they returned even more impoverished than when they left. Furthermore, homecoming is a very important process for most Nepali groups. Individuals are welcomed back from journeys with ceremonies that may include animal sacrifices, public festivals, and other activities (Kohrt forthcoming). The lack of a proper return and reintegration into the community has also been identified as a major source of distress for returning child soldiers in Nepal (Kohrt and Koenig 2009; Kohrt, et al. 2010). Similar distress arising from negative homecoming experiences was observed for returning U.S. military from Viet Nam (Fontana, et al. 1997; Johnson, et al. 1997).

Spiritual causes

A man working as a psychosocial counselor at an NGO explained that spiritual events, such as cursing, possessions, and ‘evil eye’, are thought to play a dominant role in some forms of trauma (e.g. bigar, naag, devtaa, tunamuna, and aakhaa laagyo). Boksi and bhut laagyo (struck by witches or ghosts) can cause trauma. Food and water can cause suffering if it is cursed (tunamuna).

Conflict related trauma

Conflict events included having family members ‘disappeared’, being detained, witnessing the brutal killing of a family member, bomb explosions, watching one’s house and land being burnt, destruction of livestock, loss of money and savings, being kidnapped or witnessing relatives being kidnapped, being forced to join armed groups, being forced to leave one’s children, having one’s family dispersed across the country, lacking food and shelter, lacking access to healthcare or education, being forced to move repeatedly, and having constant feelings of insecurity. One NGO worker said that war is the only true cause of psychological trauma, thus demonstrating a tight linkage of the trauma narrative and political violence for some humanitarian workers.

Trauma Idioms of Distress

Free list responses from laypersons, NGO workers, and mental health professionals revealed a range of terminology and idioms of distress. Table 1 includes the idioms participants most commonly reported as responses to traumatic events. Idioms included fear responses, sadness, suffering, and worrying. Idioms associated with supernatural phenomenon were saato gayo (soul loss) and aitin laagyo (spirit induced sleep paralysis). NGO and mental health professionals used the English terms ‘depression’, ‘trauma’, and ‘PTSD’ as responses to these events. No lay participants mentioned these English terms.

Table 1.

Nepali idioms related to psychological trauma

| Nepali idiom (transliteration) | English translation |

|---|---|

| Aatincchu | Startled |

| Aitin laagyo | Sleep paralysis, spirit induced attack with sleeping |

| Bejjat (also naak khatne, ijjat gayo) | Loss of social status; social shame |

| Birsane nasakne darghaatana | Accident/event that cannot be forgotten |

| Dar laagyo (also bhaya, traas) | Struck by fear |

| Dukha laagyo | Struck with sadness |

| Jhajhalko aauchha | Flashbacks, flashing memories |

| Maanasik aaghaat | Mental shock |

| Maanasik tanaab | Mental tension |

| Maanasik yatana | Mental torture |

| Manko gaau | Wound/sore/scar on the heart-mind |

| Manmaa asar parchha | Effects on the heart-mind |

| Manmaa kuraa khelne | Words/thoughts playing in the heart-mind; worrying |

| Paagal, baulaahaa | Crazy, mad, psychotic |

| PiDaa | Suffering, anguish, torment |

| Saato jaanchha | Soul/spirit loss |

Participants explained that these idioms differed by phenomenology and triggers. Fear-related idioms ranged from terror to anxiety:

Dar is fear of something specific that lasts only briefly such as upon seeing a snake or ghost. Traas is terror. It is feeling insecure about something that is there all time, but you cannot do anything about it. It is something that cannot be controlled. Bhaya is also a fear, but it can be addressed by working hard or preparing, such as for a test. (24-year-old female NGO worker)

Pir is constant, generalized fear, whereas chinta refers to something specific, such as fear of leaving the house to go to work. Chinta is momentary, brief, and related to something specific. (40-year-old female Nepali language instructor)

With regard to depression and sadness, the 24-year-old female NGO worker added,

Dukha is considered sorrow, but ‘depression’ (stated in English) is a state where one cannot do anything. They are unable to get motivated to do work. Riis (anger) is something that comes from small things, but traas (terror) and aaghaat (shock/trauma) come from big things.

NGO workers and mental health professionals routinely employed the term aaghaat, which refers to shock, impact, or clash. Some qualified the term as maanasik aaghaat (mental/psychological shock) to distinguish mental shocks from physical shocks (aaghaat). However, counselors explained that clients and the public often are not familiar with the term aaghaat, especially in the psychological context. Counselors felt more comfortable employing piDaa (pain, anguish, agony, torment, suffering) or maanasik piDaa (mental anguish) and other idioms when speaking with clients and the public. A client at a center for Maoist victims stated,

We have the most piDaa (suffering) and the most maanasik samasyaa (mental problems) of anyone in the entire world.

Some participants, both lay and professional, reported that dramatic negative life events could lead to symptoms of madness, psychosis, and mental illness. These events could make someone paagal or baulaahaa (mad, psychotic, crazy). Some participants added that it is not the event per se that is the problem but rather individuals who “think too much” about the events and bad life experiences who are most likely to become paagal or baulaahaa. Health professionals employed the term maanasik rog (mental illness) rather than paagal. Maanasik rog was distinguished from maanasik piDaa. A woman working as a psychosocial counselor for an NGO explained,

For maanasik rog (mental illness), these individuals can disclose things to counselors. They often have difficulty sleeping, their appetite is decreased, and they have problems studying. For maanasik aaghaat (mental shock) or piDaa (suffering, torment), individuals do not trust counselors. They do not get relief after two or three sessions. They do not want to talk. They act like statues. They act as if they are not in the real/physical world.

In contrast, a psychiatrist at a mental hospital explained that maanasik piDaa could present as psychosis:

People with piDaa (trauma/suffering) are paagal (mad). If a loved one dies, then their relatives may go mad. People believe that others should avoid utensils and water they have touched or else they will contract the madness.

A client at one of the treatment centers recounted an anecdote of a neighbor who became crazy:

This woman had a husband who was always unfaithful. She began to have strange behavior. She spoke to herself without stopping but would not speak when spoken to. She did not eat. She was pura baulaahaa (totally crazy). She ran away and was naked in a village. Her hair was unkempt. This lasted eight or nine years. One day she was startled by the loud noise of a jeep driving nearby. She suddenly realized how in disarray she was and that she was naked and so she became embarrassed. She then returned to her normal behavior.

Although this woman recovered, it was generally felt that madness from psychological trauma was permanent. A psychiatrist at the mental hospital explained,

Maanasik aaghaat has a long period of effect, often life-long and permanent. He/she will be abnormal for the rest of his/her life after the traumatic event.

Counselors reported that clients had symptoms of uncontrollable irritation and angered easily at small things. Counselors thought that those with maanasik aaghaat (mental shock) could do anything in anger; they can kill others or kill themselves.

Memory is a central feature of presentation. Birsane nasakne darghaatnaa (unforgettable events) and manko ghaau (wound/sore/scar on the heart-mind) both refer to inability to forget such events. Manko ghaau refers to a scar/sore/wound on the heart-mind. A 24-year-old NGO worker explained how hearing stories of rape left such a scar on her heart-mind:

I was ‘depressed’ [‘depressed’ stated in English] after hearing [the stories of rape survivors]. I could not sleep. Things kept racing in my mind, and I could hear our conversation over and over again. It left manko gaau (a scar on my heart-mind) that will never heal.

In this instance, a distressing experience scars the heart-mind, which is the organ of memory, just as the body becomes physically scarred through physical trauma. This scar in the heart-mind then prevents the individual from forgetting about the event, as a physical scar is a reminder of other types of trauma. The analogy extends even further: just as severe physical trauma can lead to not only a scar but also impaired functioning of an arm or leg, severe psychological trauma damages the heart-mind leaving a scar that prevents normal functioning of the organ of memory. Thus, when one tries to use heart-mind to recall other events, they only come up with remembering the traumatic event. An 18-year-old girl from rural Nepal whose family was attacked by Maoists explains that the event is constantly replaying itself in her heart-mind:

I can’t believe that it happened. The incident manmaa raakhiraakhne (is always on my heart-mind). I can’t forget; I remember it all the time.

Similarly, other survivors of trauma reported manmaa kura khelne (having worries playing in their heart-minds) that caused insomnia. Some clients ruminated about killings they had witnessed. Caregivers and psychological trauma survivors all endorsed insomnia and nightmares. A few trauma survivors describe jhajhalko aauchha (flashbacks, flashing/flickering memories), feelings of the event happening again. One psychosocial counselor for torture victims finds that none of his clients reports the PTSD symptom of “difficulty remembering parts of the event.” Most survivors have no problem remembering the event, on the contrary, they report being unable to forget the event.

An Ayurvedic doctor described how his patients would think of the past event then subsequently “go into a panic condition.” One young man who had been beaten along with his family by Maoists described intrusive memories of his traumatic event:

I worship and pray and while I am doing those activities, I do not think about the incident. Nevertheless, as soon as I go out into the street with office work if I see an accident, the exact scene of my beating repeats itself over and over again. I cannot concentrate on the work that I have to do and what is going on in front of me. I do not want to remember my tragedy but seeing bad scenes forces me to remember.

Memories of the event impair recall of other issues and decrease concentration. One NGO program administrator described a teacher who would forget what he was teaching in the middle of lessons; he stated, “Psychological trauma causes people to lose memory power.”

Somatic complaints were common. Health professionals identified somatic complaints as the primary presentation of psychological trauma: headaches, back pain, gastric problems, painful urination, visual disturbances, palpitations, high blood pressure, and fainting attacks. An Ayurvedic doctor commented that persons with psychological trauma have, “a poor immune system, weak nervous system, runny nose, and low blood pressure.” One psychosocial counselor described a connection with psychological trauma causing physical problems; “maanasik tanaab (mental tension) has an effect on the body. One is more susceptible to illness.” Counselors reported that clients appear comfortable discussing physical health problems. However, they do not typically self-disclose about traumatic events until it is uncovered through the medical history. Other common symptoms included not having enough energy to work.

A last category of idioms referred to loss of social status through traumatic events. Participants explained that social honor is lost, ijjat gayo, or that social shame is incurred bejjat. The idiom naak khatne refers one’s nose being cut as a metaphor for social shame. Participants explained that social status could be lost from traumatic events to oneself or one’s family because it demonstrated poor karma—and thus was the person’s or family’s fault—or was related to loss of honor such as through being victim of rape or assault. The role of karma will be discussed further below.

Trauma and Emotions

The second phase of the research examined people’s conceptions of emotion terms related to suffering from trauma, specifically their comprehension of terms and how they viewed the relationships of these terms. The comprehension results of the 22 emotion terms are presented in Table 2. Terms such as dukha, chinta, dar, riis, and pir are well understood by the general population. PiDaa is also relatively well understood. Aaghaat, however, was the least intelligible emotion term for the general public sample. The general population also poorly understood two English terms used by Nepali health professionals, ‘depression’ and ‘trauma’.

Table 2.

Emotion Term Comprehension (ranked in decreasing order of comprehension)

| Nepali Word | Mean | Std. Dev. | English corollaries* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mayaa | 4.61 | 0.97 | Love, liking, affection, compassion |

| Dukha | 4.45 | 0.94 | Trouble, grief, sorrow, misfortune, hardship |

| Chinta | 4.42 | 0.97 | Anxiety, worry, trouble |

| Dar | 4.39 | 1.06 | Fear, dread, awe, terror |

| Riis | 4.33 | 1.05 | Anger, wrath, ill-temper, resentment |

| Pir | 4.21 | 1.27 | Trouble, anxiety, sorrow, anguish |

| Niraashaa | 4.18 | 1.04 | Disappointment, despair frustration, sadness |

| Sukha | 4.15 | 1.06 | Happiness, joy, pleasure, comfort, tranquil |

| PiDaa | 4.09 | 1.26 | Pain, anguish, suffering, agony, torture, pang |

| Laaj | 4.09 | 1.35 | Shyness |

| Eklopan | 3.91 | 1.47 | Loneliness |

| GhriNaa | 3.88 | 1.45 | Disgust |

| Paagal | 3.82 | 1.38 | Madness, insanity, derangement |

| Hadad | 3.79 | 1.43 | Hasty, impetuous, rash |

| Bhaya | 3.73 | 1.46 | Fear, awe, fright, dread, trepidation |

| Aatanka | 3.52 | 1.62 | Terror |

| Traas | 3.48 | 1.48 | Fright, terror, fear, alarm |

| Tanaab | 3.27 | 1.72 | (Mental) tension |

| Laachaar | 3.18 | 1.70 | Helpless, having no means, forlorn, destitute |

| SurTaa | 3.00 | 1.71 | Sorrow |

| Hataas | 2.91 | 1.59 | Despair, loss of hope |

| ‘Depression’ | 2.52 | 1.50 | English term administered |

| Aaghaat | 2.30 | 1.42 | Trauma, shock, impact |

| ‘Trauma’ | 1.61 | 1.20 | English term administered |

English translations adapted from Nepali-English dictionaries (Gautam 2001; Schmidt 2000; Singh and Singh 1991).

A cultural consensus model fit the judged similarities between common emotion terms (eigenvalue ratio = 13.1, mean first factor loading = 0.61 (SD = 0.15), all factor loadings > 0). Figure 1 represents the first two dimensions of a correspondence analysis of similarity ratings. Emotion terms related to fear and fright form a distinct cluster (bhaya, dar, and traas). Riis (anger) and paagal (madness) form a distinct and moderately overlapping cluster. A third cluster encapsulates negative emotional states related to suffering: chinta (worry), pir (anxiety/sorrow), piDaa (anguish/suffering), dukha (sorrow/hardship). The final four terms lie somewhere between the anxiety/suffering cluster and the madness/anger cluster. These are laachar (helplessness), aaghaat (trauma), tanaab (mental tension) and niraashaa (despair).

Figure 1.

Correspondence analysis of trauma-related emotion terms with 95% confidence ellipses around each term (Dimensions 1 & 2).

Notably, the common clinical term, aaghaat, lies somewhere between its presumed synonym for trauma, piDaa, and the more stigmatized term, paagal (madness). Indeed, the judged similarity between paagal and aaghaat is significantly greater than the judged similarity between paagal and piDaa (mean similarity = 3.44 vs. 2.59, Wilcoxon matched pairs signed-rank test, p < 0.05). This suggests that the term (maanasik aaghaat) identified by mental health professional and NGO workers as synonymous with psychological trauma (maanasik piDaa) is viewed by the general public as having some similarity to madness/psychosis (paagal).

Vulnerability to Traumatic Events

Mental health professionals and clients discussed vulnerability at two levels: vulnerability to negative life experiences and vulnerability to express emotional and psychological symptoms after experiencing negative events. Previously, Sharma and van Ommeren (1998) found that many Bhutanese refugees explained their suffering in terms of karma ko phal, the fruit of sins in prior lives. Respondents in our study explained that karma dictates vulnerability to negative life events. Karma is the concept of good or bad deeds determining prosperity or suffering. Karma thus dictates who does and who does not suffer from traumatic events. A 56-year-old male Hindu priest in central Nepal explained the relationship of karma with traumatic events:

Ghatanaa bhaeko chha, yo karma ko phal ho. [An accident has happened; it is the result/fruit of karma.]

Naraamro nagarnu hai, paap ko phal dekhalaa hai.[Do not do bad things; you will see the consequences/fruit of your sins.]

Karma is related to the experience of traumatic in two ways. First, an individual may have committed sins in a prior life and suffer the consequences as traumatic events in this life. When asked specifically whether sins committed in this current life can lead to traumatic events in this same lifetime, multiple Hindu priests explained that this did not happen. Instead, the sins committed in this life lead to traumatic events in future lives or in the lives of family members.

Second, sins committed by one’s family members in this life and sins committed by one’s deceased ancestors can also result in the experience of traumatic events for other family members (pariwaarko karma, the family’s karma). One Hindu priest explained that sins of the mother or father lead to the family’s suffering. For example, a sinful parent will have children who are mute, deaf, experience accidents, and die at an early age. The Hindu priest explained,

Mero purkhaa ko paap maile bhogdaichhu. [I must bear the sins of my ancestors.]

Therefore, the experience of traumatic events can be highly stigmatizing because people think that the trauma survivor must have been a bad person in a prior life or that his/her family members and ancestors were bad people. Not surprisingly, traumatic events are often covered up within the family because the events reflect badly upon them as well as the individual who experienced the event.

Women are considered to have been less pious than men were in their previous lives, and consequently they are born female and at greater risk of traumatic events. Similarly, persons from low castes are considered to have poorer karma, and thus they are fated to experiences more negative events during their lifetime.

Regarding vulnerability to expression of psychological distress after negative life events, an Ayurvedic doctor referred to constitutional differences:

Individuals are most susceptible to effects of trauma during the third trimester of pregnancy. If the mother is traumatized during this time, the child will be affected for his or her lifetime. To avoid this, pregnant women should only pay attention to the fetus, and ignore what is happening around them. Mothers who are strong and dedicated will not have traumatized children. Mothers with naasaa kaamjor (dry or weak nerves) are at risk of having children with psychological trauma. If trauma occurs after birth, it has much less effect on a person’s life. However, if the trauma is severe, such as torture, then the person will have psychological difficulties for their lives that cannot be cured. Trauma from graha (unseen/astrological causes) can have lasting effects. Emotional, artistic, and mentally active people are most at risk of psychological trauma because they are of ‘nerve-type’ and get frustrated easily.

Participants also described susceptibility based on how strongly one’s saato (spirit or soul) is attached to the corporeal body. Souls are seen as less securely attached among children. Children lose their saato from frightening events, and this causes behavior changes, such as piDaa and nightmares. The loss of soul makes them more susceptible to illnesses ranging from diarrhea to respiratory infections. Traditional healers can treat saato loss. It is thought that adults lose their souls less easily than children do, and thus typically do not suffer from saato loss. Among adults, women are considered more vulnerable than men are to saato loss. One adult woman described an incident when she suffered saato loss.

I was walking along a street. Then I saw men driving on motorcycles. They were driving around a man and beating him. I saw blood everywhere. Then saato gayo (my soul left). I do not know how I got back to where I was going. I could not do work that afternoon. My saato returned later that evening, but I had problems sleeping for more than a week.

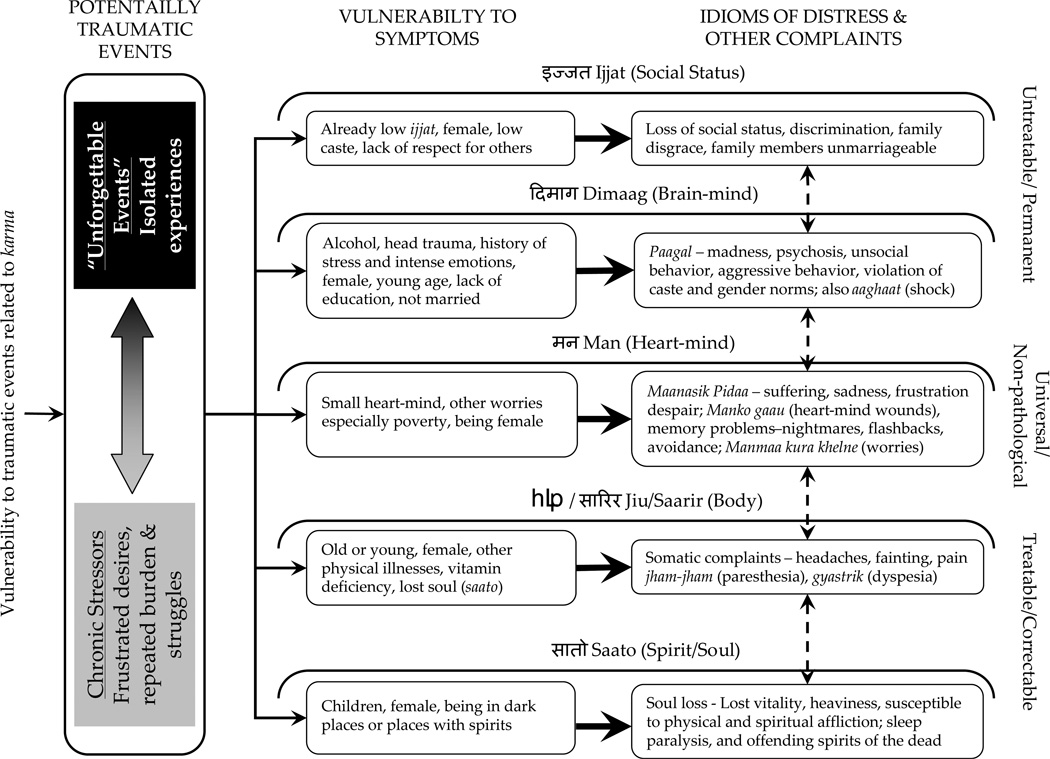

Model for Ethnopsychology of Trauma, Idioms of Distress, and Therapeutic Implications

Figure 2 is a schematic attempting to represent psychological trauma within the context of this Nepali sample and other ethnographic work in different communities throughout Nepal (Kohrt and Harper 2008). At the left of the schematic is vulnerability to negative life experiences. Psychological trauma is rooted in concepts of vulnerability wherein individuals with poor karma who did not fulfill their religious path in prior lives or have sinful ancestors are more likely to suffer from traumatic events in this life. This vulnerability is important to keep in mind when considering therapeutic interactions because karma attributes a degree of culpability to people with negative life experiences.

Figure 2.

Ethnopsychological model with idioms of distress for psychological trauma

Traumatic experiences occur along a continuum. At one end of the continuum are chronic stressors and repeated burdens such as poverty, lack of education, and failure to achieve ones’ goals. At the other end of the spectrum are specific acute events that an individual may describe as “unforgettable.” We find that the term birsane nasakne dargatana (unforgettable accidents/events) captures individualized experiences that produce psychological distress. In an epidemiological study, Thapa and Huff (2005) also found that the role of lasting memory was central in eliciting traumatic experiences; they reported that nearly all persons with high PTSD symptomatology endorsed the phrase dukha lagne ghatanako gahiro chap baseko (having deep and long-lasting impression of the terrifying event). However, they did not report what percentage of people endorsed the phrase but did not have high PTSD symptom severity. In the model, individuals who suffer either chronic stressors or acute unforgettable events have differential susceptibility to psychological symptoms. Because children have saato (spirit/soul) that are attached weakly, they are more likely to have soul loss and fright. Women are more susceptible than men are because of being considered constitutionally weaker. Lastly, individuals with small or weak man (heart-minds) are also more likely to suffer psychological distress (McHugh 1989).

The emotional and psychological consequences of negative life experiences, both chronic and distinct, can be mapped on the ethnopsychological framework of man (heart-mind), dimaag (brain-mind), jiu/saarir (physical body), saato (spirit/soul), and ijjat (social status/social face). Referring back to the emotion model in Figure 1, the three clusters map onto these different elements of the self. The anxiety/suffering cluster (chinta, pir, piDaa, and dukha) reflects disturbance of the man (heart-mind). The fright cluster (dar, bhaya, and traas) are strong sudden emotions that disrupt the saato’s attachment to the body. The cluster of madness and anger (paagal and riis) reflect disturbance of the dimaag (brain-mind).

There are two categories of symptoms related to heart-mind disturbance. One category is the general emotions of suffering, sadness, and worry. The other category is memory related phenomenon because the heart-mind is the organ of memory. As reported above, memory symptoms are described through the ethnophysiology of scars on the heart-mind. This scarring of the organ of memory leads to flashbacks, rumination, and other intrusive recollections of the event. Desjarlais describes this among the Yolmo ethnic group of central Nepal:

Among the Yolmo [people] significant events, hurtful ones especially, can leave a mark, a trace, at times a maja or ‘scar’… within a person’s sem [heart-mind], much as words can be carved into stone or sounds engraved within a phonographic record. (Desjarlais 2003, p. 148)

In urban and rural clinical settings, patients often focused on the inability “to forget” certain life experiences as one of their main complaints. The constant remembering of specific events in the heart-mind (i.e. intrusive memories) caused physical and psychological distress. Common to these complaints was a sense that one could not control when these memories would intrude and that once the thoughts started, individuals could not stop thinking about them nor prevent or abate physical and psychological sequelae. Patients consistently expressed the desire “to forget” these events. One patient stated, “my goal is not to remember the suffering.” A male patient beaten by Maoists recounts,

When I saw it all happening, I did not think it was real. I did not think this was happening to me. Even now, I cannot believe that it happened to me. All I want to do is forget that it happened. But, I cannot forget.

Pettigrew and Adhikari (2009) describe this phenomenon among the Tamu-mai (Gurung) ethnic group in western Nepal:

[Forgetting fear] should also be described as ‘not remembering’ or more specifically, no longer having intrusive memories. Since the end of the insurgency people have talked a lot more about forgetting fear. While people sometimes talked about past fears, fear was not a currently experienced emotion in the sense that it was during the insurgency. “Forgetting fear” was also a coping strategy that allowed villagers to put the past behind them. (Pettigrew and Adhikari 2009: 420)

Disturbances of the dimaag (brain-mind) represent a more severe tier of problems. Brain-mind disturbance symptoms include madness, psychosis, aggression, and unsocial behavior. The association of madness and anger is common in Nepal, with the inability to control one’s anger seen as a symptom of madness and mental illness (Kohrt and Harper 2008). The community stigmatizes brain-mind problems more than heart-mind problems because of a fear of contagion and consideration of these brain-mind problems as permanent, whereas heart-mind disturbances may be transient.

One of the key findings from the cultural consensus analysis and the semi-structured interviews was the interpretation of aaghaat. Whereas NGO and health professionals used this term to describe trauma as mental shock, the public often did not understand the term. More importantly, laypersons identified aaghaat in the paagal and riis (madness and anger) cluster of brain-mind disturbance. Thus, aaghaat when used by health professional has a potentially negative effect for those seeking care and their families because the term is associated with highly stigmatized conditions.

To summarize, a Nepali ethnopsychology and ethnophysiology of trauma comprises vulnerability to traumatic events, with blame placed upon sins in past lives and sins of family members for the experience of these events. Events that cause suffering cover a range of experiences from chronic inability to meet ones needs to discrete 'unforgettable' events. The events produce suffering based on different elements of the self. Events that disturb the heart-mind cause sadness, despair, anguish, and worry. Moreover, disturbances of the heart-mind lead to intrusive memories of the event. Events can disturb the brain-mind causing anger and/or madness. The frightening component of the event leads to rupture of the soul from the body with the concomitant effects of soul loss such as vulnerability to physical illness. The physical body may be damaged by a traumatic event leading to headaches, body pain, gastrointestinal problems, vision changes, and other somatic complaints. The experience of these events threatens one’s social self or social honor. Because traumatic events typically imply poor karma, experiencing traumatic events is associated with a loss of social status.

Idioms of distress and ethnopsychology/ethnophysiology can be incorporated into care for psychological trauma in a number of ways. Mental healthcare professionals, psychosocial workers, and other care providers will encounter survivors of trauma in a variety of settings. The framework described below fosters a multi-disciplinary approach in which individuals address needs at the point of service entry and make referrals to other sources of care. First, when trying to elucidate exposure to traumatic events, one of the most effective pathways may be focusing on the inability to forget certain events. In clinical settings, the phrases tapaaiko kunai birsane nasakne dargatana bhaeko chha? (have you had any events/accidents that you cannot forget?) and dukha lagne ghatanako gahiro chap baseko (having deep and long-lasting impression of the terrifying event) are effective for eliciting traumatic experiences.

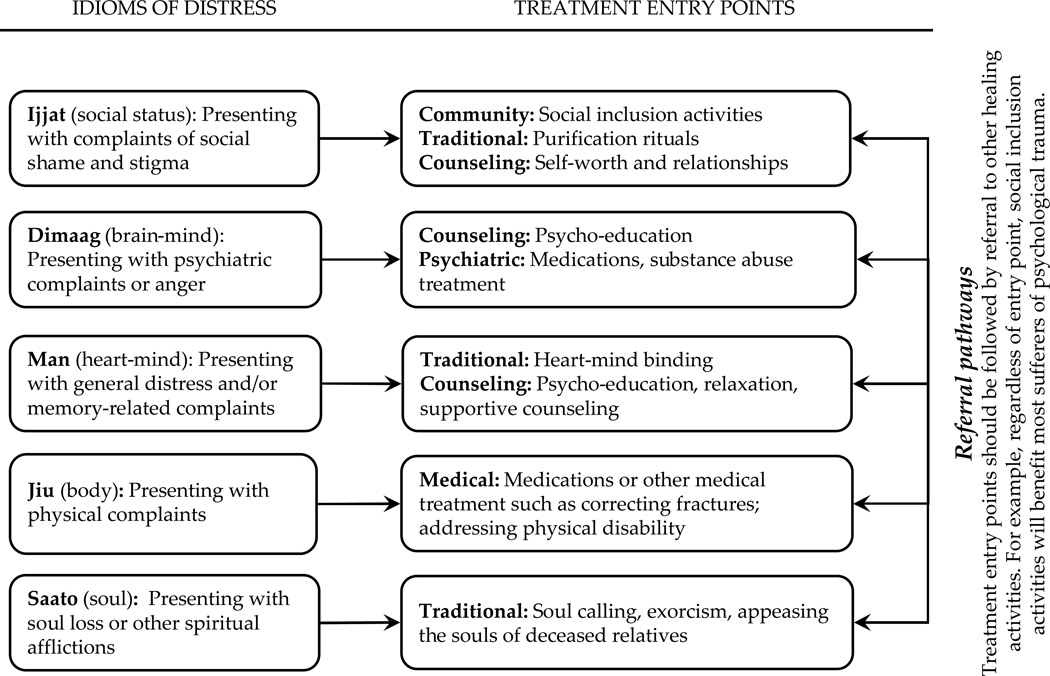

The type of symptoms most distressing to the individual should dictate initial treatment and referrals. Figure 3 presents treatment entry points for psychological trauma based on presenting idioms of distress. For example, if an individual or his/her family is most concerned about physical problems such as headaches, vision changes, or other somatic complaints, they are likely to first present to a health post worker or physician. In these cases, it would be beneficial to adequately address the possibility of underlying physical pathology as well as identify acceptable referrals for additional support. One of the dangers is ignoring possible treatable physical illnesses that are underlying or comorbid with psychological distress (Kohrt, et al. 2005).

Figure 3.

Treatment entry points for psychological trauma based on presenting idioms of distress.

If a person presents with psychotic complaints or signs of mental illness, it would be more appropriate to highlight a combination of psychiatric care and counseling for treatment. If a survivor of trauma has a substance abuse problem, as was described by counselors in this study, then psychiatric inpatient substance abuse treatment may be necessary. Among Cambodians, anger may be a better indicator of trauma exposure than PTSD (Hinton, et al. 2009a), and therefore screening for anger may be an effective approach to begin considering intervention to alleviate trauma-related distress. In this Nepali sample, anger was the most proximal emotion to psychotic behavior. Thus, anger, should similarly be a potential screen for trauma, especially among those presenting to psychiatrists.

In contrast, disturbances of the heart-mind are not seen as physical or mental pathology but rather a form of natural distress in response to certain types of events. Therefore, heart-mind problems may best be served by encouraging support from friends and family, supporting traditional healing if desired, and provision of psychosocial counseling. One form of traditional healing done by dhami-jhankri (shamans) in Nepal is man badne, which means to bind the heart-mind. This is seen as a way to control the distressing processes or bad memories, and has been reported as a form of healing sought out by former child soldiers (Kohrt forthcoming). Counseling in Nepal has been developed around the construct of the heart-mind, rather than a treatment for mental illness related to brain-mind dysfunction (Kohrt and Harper 2008). The literal translation of the Nepali term commonly used by psychosocial NGOs for ‘counselor’ is manobimarshakarta (person who advises on matters of the heart–mind).

If the main complaint after a traumatic event is soul loss, it may be appropriate to recommend a traditional healing ceremony. Because the soul brings vitality to the body, the return of the soul is necessary before one’s body, heart-mind, or brain-mind can begin to heal. Traditional healing for return of the soul can be done alongside medical treatment to heal the body (Kohrt and Harper 2008). Traditional healing for many forms of suffering, not only fright or traumatic events, has been described in many ethnic groups in Nepal (Desjarlais 1992; Maskarinec 1995; McHugh 2001; Nicoletti 2004; Peters 1981).

If a primary concern is loss of social status related to experiencing traumatic events, this could be remedied through a number of mechanisms. One option is traditional or religious healing. Religious healing can be seen as a way to account for poor karma. Performing offerings or rituals for sins in a past life may prevent the experiences of future traumatic events in one’s current life. These rituals also improve social perception and increase social support of sufferers (Desjarlais 1992; Maskarinec 1992; Peters 1981). Often if a child is identified as having bad karma or having been born in unfavorable astrological context, rituals can be performed to prevent a life of repeated traumatic events. Loss of social status also can be addressed through community-based social inclusion activities. Many sufferers of traumatic events are afraid they will be excluded from interactions with other. If social inclusion activities can be facilitated for trauma survivors, this could help ameliorate fear of exclusion. Thirdly, counseling can focus on the feelings of low self-worth and perceived interpersonal disruptions. Counselors, through supportive listening, can present a stable social connection for trauma survivors, as well as provide psycho-education and problem solving skills (Jordans, et al. 2007; Tol, et al. 2005).

Ultimately, regardless of whether a trauma survivor presents to a psychosocial counselor, physician, traditional healer, or psychiatrist, it will be beneficial to support pluralistic healing for psychological trauma. Individuals may present with somatic complaints, but treating these uncovers evidence of heart-mind disturbances or soul loss. As Figure 3 illustrates, the practitioner can refer the individual and their family to other types of healers, in accordance with their religious, spiritual, and health-behavior beliefs. Likely, the individual and his/her family already will be seeking multiple forms of support.

One of the crucial aspects of care is reducing and preventing stigma. Psychosocial nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Nepal and elsewhere have cautioned against employing terminology that may stigmatize program participants (IASC 2007). In Nepali, the term kalanka refers to a physical blemish or spot, but also to slander, vilify, or misrepresent to harm another person (Turner 1931). In Nepal, mental health problems historically have been associated with kalanka. This is particularly true for psychological problems perceived to be the result of brain-mind dysfunction (Kohrt and Harper 2008). Thus, it is crucial to consider how interventions inadvertently may exacerbate stigma and lead to barriers to care. One specific conclusion that can be drawn from this research is the problematic use of the idiom maanasik aaghaat (mental shock/trauma). While healthcare providers perceived this as a possible linguistic corollary for psychological trauma, the lay public did not always understand the term, and when they did, it was perceived as referring to the highly stigmatized condition of brain-mind dysfunctions such as madness and uncontrolled anger. If a healthcare professional or NGO worker was to label someone as having maanasik aaghaat, the individual and his/her family may perceive this as an incurable condition. Therefore, we would recommend language such as maanasik piDaa, which is more informative and less pathologizing than aaghaat.

Another aspect of stigma is the cultural model of trauma causality in Nepal, which may differ from Western conceptions. Hinton and Lewis-Fernandez (in press) point out that effective evaluation and treatment of disorders necessitates understanding the stigma linked with idioms of distress. Summerfield (2001) and others have suggested that PTSD is a desirable label because it removes culpability from the individual and often is associated with receipt of monetary or other support through government policies or lawsuits. In contrast, traumatic events in Nepal can be perceived as the result of personal infractions in past lives and sins of one’s family and ancestors, which are transmitted through karma into this life. Thus, people may be ashamed to report experiencing traumatic events. In addition, families may be reluctant to acknowledge or seek help for traumatized family members because it reflects badly on the family’s and ancestors’ religious piety. In addition, the experience of a traumatic event may differentially stigmatize certain family members. We found that mothers often blamed themselves or were blamed by others for traumatic events occurring to family members. Dahal’s (2008) work among war widows in Nepal finds that families and communities often blame and ostracize widows for the deaths of their husbands. The issue should be considered in both public health approaches and individualized care.

Despite claims of PTSD’s desirability in Western context, most mental health workers in Western settings likely will have seen clients who also blame themselves for traumatic events without having to invoke the concept of karma. Western therapeutic approaches for these clients may be a worth considering for Nepali survivors of trauma as well. As mental healthcare and psychosocial support resources grow in Nepal, it will be important to address stigma hand-in-hand with development of care systems. If stigma is not a major focus of the mission to make mental healthcare and psychosocial services available to trauma survivors, there is a risk that newly established services will go unused or that interventions could make trauma survivors more vulnerable through stigmatization.

Conclusion

This research revealed that psychological trauma is not a unitary construct in Nepal. Rather, psychological sequelae of negative life events are expressed through an array of idioms of distress. The Nepali ethnopsychology/ethnophysiology both overlaps and diverges from DSM psychiatric classification of PTSD. In Nepal, the response to negative life events includes multiple possible manifestation such as general distress and inability to control memory reflected as a disturbance in the heart-mind, behavioral manifestations of anger and madness reflecting dysfunction of the brain-mind, a fright response resulting in loss of the soul, physical impairments with damage to bodily systems, and a threat to personal and familial social status.

Our findings suggest that exploring a range of idioms of distress incorporated into a broad understanding of local ethnopsychologies and ethophysiologies can foster effective communication with clients. This is more helpful than trying to identify single terms to approximate the concept of psychological trauma. Similarly, others also have advocated that trauma treatment across cultural settings should comprise strong holistic interventions that keep PTSD in mind but also intersect more broadly with issues of guilt, somatic complaints, and other manifestations of distress (McKenzie, et al. 2004).

A primary limitation of this study was the presentation of only one ethnopsychological/ethnophysiological model. Ethnic composition likely influences ethnopsychological models significantly. The analysis of emotions presented here is based on interviews primarily with a sample representative of the ethnic heterogeneity of the capital Kathmandu. Therefore, the model produced illustrates how psychological trauma is communicated within this specific demographic. It is not representative of rural, low caste, or non-Newar ethnic minority (Janajati) groups who more commonly reside outside the capital. Therefore, the model does not speak to all ways of viewing psychological trauma in Nepal. Pettigrew (2009) provides a description of the understanding of fear among Tamu-mai (Gurungs) in western Nepal that sheds light upon possible ethnic diversity in traumatic experience. Ultimately, there is not one single totalizing ethnopsychology of trauma in Nepal because of the range of ethnic, linguistic, and socioeconomic groups. Rather than relying solely on the model provided here, we offer this study as a framework for practitioners working with trauma survivors in Nepal and elsewhere. We suggest that they develop their own ethnopsychological models when caring for specific populations.

Another limitation is the rapidity of change and trends in the health and development fields. In both Western and other settings, the terminology for psychological trauma is shifting continuously. For example, Dwyer and Santikarma (2007) have written about the labeling transition from ‘crisis clinics’ to ‘trauma clinics’ in Indonesia. Public mental health campaigns should address the public interpretation of the evolving terminology for psychological trauma. The public interpretation of terminology may have unforeseen consequences in a world of rapidly changing vocabulary for distress. We found that clinicians’ attempts to employ a linguistic corollary for PTSD led to use of a relatively unfamiliar term (aaghaat) that the public found stigmatizing. Rapidly shifting idioms, both within lay and professional language, further necessitate grounding within ethnopsychology/ethnophysiology, which likely follows transformations that are more gradual. From an intervention and clinical standpoint, the alleviation of suffering starts with local frameworks, needs, concerns, and processes of identification. Ultimately, healing begins with understanding and understanding begins with listening to local models as expressed through idioms of distress.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to all of the participants and organizations who participated in the study. Srijana Nakarmi was the lead research assistant for the study. Thanks to the individuals who contributed to discussions in preparing the manuscript: Nanda Raj Acharya, Ganesh Bhatta and his family, Peter Brown, Christina Chan, Tulasi Ghimirey, Ian Harper, Mark Jordans, Suraj Koirala, Geeta Manandhar, Mahendra Nepal, Judith Pettigrew, V.D. Sharma, Damber Timsina, Wietse Tol, Lotje van Leeuwen, and Carol Worthman. Special thanks to Devon Hinton and Roberto Lewis-Fernandez for their insight and thoughtful suggestions in revising the manuscript. The first author was funded by an NIMH National Research Service Award, the Wenner-Gren Foundation, and Emory University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

Footnotes

Young (1995) argues that the psychiatric lens of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) originally was developed primarily to understand the mental health problems and frame treatment of returning American veterans from Vietnam For example, Young ties the growing interest in psychological trauma during the 1860s to increasing use of railway transport and British Parliament’s passing in 1864 of legislation to financially compensate victims of railway injury. In addition, Summerfield (2001) correlates the growing interest in psychological trauma with changes in personhood related to entitlement, expected success, and absence of suffering. PTSD legitimizes victimhood, moral exculpation, and disability pension. Bremner (2002) also suggests that personality has changed from a warrior class where life was filled with violence and people endured severe hardship with great courage and strength to a “post-warrior” class where trauma overwhelms individual resources. From automobile collisions to overhearing sexual jokes in the workplace, identifying with the psychological trauma discourse provides the foundation for compensation Summerfield (2001) views PTSD as the product of compensation pursued on the basis of individual rights: “An individualistic rights conscious culture can foster a sense of personal injury and grievances and thus a need for restitution in encounters in daily life that were formerly appraised more dispassionately.”

Argenti-Pillen (2003) describes the how the new breed of “fearless women” in Sri Lanka who engage in trauma intervention programs are also the women who traveled throughout the country pursuing claims for disappeared husbands and sons, also an example of specific political context in which the construct becomes employed. An outspoken critic of the trauma and violence literature, Summerfield (1999) states that (1) trauma is not necessarily widespread in conflict settings, and (2) war is a social experience requiring healing through social means, not Western mental health intervention. Summerfield refers to the work of Somasundaram (1996) in Sri Lanka, which states “none of the subjects considered themselves psychiatrically ill, and just saw their symptoms as an inevitable part of the war.”

Contributor Information

Brandon A. Kohrt, Department of Anthropology, Department of Psychiatry, Emory University, 1557 Dickey Drive, Atlanta, GA 30322, Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal, brandonkohrt@gmail.com, 404-895-1643

Daniel J. Hruschka, School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, SHESC 233, P.O. Box 872402, Tempe, AZ 85287-2402, dhrusch@gmail.com

References

- Argenti-Pillen Alex. Masking terror: how women contain violence in southern Sri Lanka. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bass J, Neugebauer R, Clougherty KF, Verdeli H, Wickramaratne P, Ndogoni L, Speelman L, Weissman M, Bolton P. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda:6-month outcomes: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2006;188:567–573. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.6.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett Lynn. Dangerous wives and sacred sisters: social and symbolic roles of high-caste women in Nepal. New York: Columbia University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Bass J, Neugebauer R, Verdeli H, Clougherty KF, Wickramaratne P, Speelman L, Ndogoni L, Weissman M. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3117–3124. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton Paul. Local perceptions of the mental health effects of the Rwandan genocide. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2001;189(4):243–248. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200104000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton Paul, Bass Judith, Betancourt Theresa, Speelman Liesbeth, Onyango Grace, Clougherty Kathleen F, Neugebauer Richard, Murray Laura, Verdeli Helen. Interventions for depression symptoms among adolescent survivors of war and displacement in Northern Uganda: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;298(5):519–527. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken PJ, Giller JE, Summerfield D. Psychological responses to war and atrocity: the limitations of current concepts. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;40(8):1073–1082. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00181-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau Joshua. Cultures of trauma: anthropological views of posttraumatic stress disorder in international health. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 2004;28(2):113–26. doi: 10.1023/b:medi.0000034421.07612.c8. discussion 211–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford Terry. Tibetan Buddhist Medicine and Psychiatry. York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dahal Kapil Babu. Medical anthropology in Nepal. The Innovia Foundation Newsletter. 2008;(6):7–9. [ www.innoviafoundation.org] [Google Scholar]

- Desjarlais Robert R. Body and emotion : the aesthetics of illness and healing in the Nepal Himalayas. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Desjarlais Robert R. Sensory biographies : lives and deaths among Nepal's Yolmo Buddhists. Volume 2. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer Leslie, Santikarma Degung. Posttraumatic politics: Violence, memory, and biomedical discourse in Bali. In: Lemelson R, Kirmayer L, Tobin A, editors. Inscribing trauma: Cultural, psychological, and biological perspectives on terror and its aftermath. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A, Schwartz LS, Rosenheck R. Posttraumatic stress disorder among female Vietnam veterans: a causal model of etiology. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(2):169–175. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox Steven H. The Mandinka nosological system in the context of post-trauma syndromes. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2003;40(4):488–506. doi: 10.1177/1363461503404002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French Lindsay. The political economy of injury and compassion: amputees of the Thai-Cambodia border. In: Csordas TJ, editor. Embodiment and Experience: The Existential Ground of Culture and Self. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. pp. 69–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam Choodamani. Gautam's Up-To-Date Nepali-English Dictionary. Biratnagar, Nepal: Gautam Prakashan; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton Devon, Hinton Susan. Panic disorder, somatization, and the new cross-cultural psychiatry: The seven bodies of a medical anthropology of panic. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry. 2002;26(2):155–178. doi: 10.1023/a:1016374801153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton Devon E, Pich Vuth, Safren Steven A, Pollack Mark H, McNally Richard J. Anxiety sensitivity among Cambodian refugees with panic disorder: A factor analytic investigation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20(3):281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton Devon E, Rasmussen Andrew, Nou Leakhena, Pollack Mark H, Del Vecchio Good Mary-Jo. Anger, PTSD, and the nuclear family: a study of Cambodian refugees. Social Science & Medicine. 2009a doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.018. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton Devon E, Lewis-Fernandez Roberto. Anxiety disorders and culturally specific complaints (idioms of distress): an analysis of their clinical importance. In: Simpson HB, Neria Y, Lewis-Fernandez R, Schneier F, editors. Understanding anxiety: clinical and research perspectives from the Columbia University Department of Psychiatry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]