Abstract

Alus, the short interspersed repeated sequences (SINEs), are retrotransposons that litter the human genomes and have long been considered junk DNA. However, recent findings that these mobile elements are transcribed, both as distinct RNA polymerase III transcripts and as a part of RNA polymerase II transcripts, suggest biological functions and refute the notion that Alus are biologically unimportant. Indeed, Alu RNAs have been shown to control mRNA processing at several levels, to have complex regulatory functions such as transcriptional repression and modulating alternative splicing and to cause a host of human genetic diseases. Alu RNAs embedded in Pol II transcripts can promote evolution and proteome diversity, which further indicates that these mobile retroelements are in fact genomic gems rather than genomic junks.

1. Introduction

Alu repeat elements are the most abundant interspersed repeats in the human genome. They are a family of short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) that use the reverse transcriptase and nuclease encoded by long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) to integrate into the host genome [1–3] and are found in the human genome in a number of ~1.100,000 copies, covering ~10% of its total length [4]. Functioning as transacting regulators of gene expression, pol III transcribed Alu and B1/2 (Alu-like elements in mouse) RNAs can interact with pol II and repress mRNA transcription [5–7]. Inverted Alu repeats are target for A-to-I editing by adenosine deaminases (ADARs) and can cause alternative splicing and drive proteome diversity [8]. Beside its role in human genomic evolution and diversity, Alu insertions and Alu-mediated unequal recombination contribute to a significant proportion of human genetic diseases [9]. Alu RNAs can also induce age-related macular degeneration following direct cytotoxicity to retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells [10].

In this brief paper, the author will describe the structure of human (Alu) and murine (B1, B2, ID, and B4) retroelements, a broad overview of the contribution of Alu retrotransposition to human diseases, and finally describe in depth a novel role of double-stranded Alu RNAs affecting the progression of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and Alu editing by ADARs.

2. Structure of Alu and Murine Mobile Elements

Alu typical sequences are ~300 nucleotides long and are classified into subfamilies according to their relative ages (for review see [11]). They have a dimeric structure and are composed of two similar but distinct monomers: left and right arms of 100 and 200 nucleotides long, respectively, held together by an A-rich linker and terminated by a short poly(A) tail (Figure 1(a)). Each of the Alu subunits originated from 5′ and 3′ terminal segments of 7 SL RNA [12–14]. Alu sequences contain internal Pol III promoter elements (Box A and Box B) and they are CG and CpG rich [11]. Alu subunits fold independently and conserve secondary structure motifs of their progenitor 7 SL RNA (Figure 1(b)). They were initially considered as selfish entities propagating in the host genome as “junk DNA” [15]. Now, it becomes more and more evident that the evolution of Alu subfamilies interacts in a complex way with other aspects of the whole genomic dynamics. Alu elements are specific to primates [11] and only one type of SINE in the human genome. The mouse genome contains four distinct SINE families: B1, B2, ID, and B4. B1 and B2 elements occupy approximately 5% of the mouse genome with about 550,000 and 350,000 copies, respectively [16]. Similar to Alu, B1 SINEs are also thought to be derived from 7SL RNA and transcribed by pol III into ~135 nucleotide B1 RNA, which approximates the left arm of Alu [17] (Figure 1(c)). B1 SINEs are monomers with an internal 29 nucleotide duplication [18]. Like the B1 element, B2 is transcribed by the polymerase III promoter sequence. Unlike B1, it shares significant homology at the 5′-end with tRNA, and they are believed to be derived from tRNA [19] and encode the ~200 nucleotide B2 RNA (Figure 1(c)) [20]. ID repeat elements are believed to be derived from a neuronally expressed BC1 gene, and they are 69 nucleotides long and are small in number about 42,200 copies; however, they have major presence in the rat genome [21]. The B4 repeat element appears to be a result of fusion of ID element at 5′-end and the B1 element at the 3′-end [22], and they are 147 nucleotides long and about 329,838 copies.

Figure 1.

Architecture of Alu, B1, and B2 repeat elements. (a) Alu elements are about 300 nucleotides long composed of two arms joined by a mid. A-stretch and terminated by a poly (A) stretch. They contain two boxes (A and B) of the RNA polymerase III internal promoter. (b) Alu RNA secondary structure (adapted from [23]) and (c) B1 and B2 RNA secondary structure (adapted from [24]).

3. Alu and Human Genomic Diversity

Alu mobile elements were identified originally 30 years ago in the human DNA [25] and were named for an internal AluI restriction enzyme recognition site [26]. The sequence and structure analysis indicated that Alu elements were ancestrally derived from the 7SL RNA gene which is a component of the ribosomal complex [13]. They were present at 500,000 copies [27], and they recently have arisen to a copy number in excess of one million within the human genome [28]. The amplification of Alu elements is thought to occur by the reverse transcription of an Alu-derived RNA polymerase III transcript in a process called retrotransposition [1]. A self-priming mechanism of reverse transcription by the Alu RNAs has also been proposed [29]. Because Alu elements have no open reading frames, they use for their amplification the machinery and the exogenous enzymatic function of long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) [2, 30–32]. In addition, the poly(A) tails of LINEs and Alu elements are thought to be the common structural features that are involved in the competition of these mobile elements for the same enzymatic machinery for mobilization [33]. Alu sequences within the human genome can be divided into subfamilies based upon diagnostic mutations shared by subfamily members, and they appear to be of different genetic ages [34–39]. The earliest Alu elements were the J subfamily, followed by S subfamilies that include Sx, Sq, Sp, and Sc, and followed by the more recent Y subfamilies including Ya5 and Yb8 the most dominant in humans [11, 40, 41]. The young Alu elements provide new information about the genomic fossils for the study of human genetic diversity. The rate of Alu amplification is estimated to be of the order of one new Alu insertion in every 20 births [42, 43]. Homologous recombination between dispersed Alu elements might result in various genetic exchanges, including duplications, deletions, and translocation which could be a mechanism for the creation of genetic diversity in the human genome. The fixation of specific mobile element insertion sites in a population can be used as a distinct character for phylogenetic analysis and could be useful markers for studies of human population diversity and origins [44–47]. It has been reported that there have been about 5,000 lineage-specific insertions fixed in the human genome since their divergence [48, 49]. However, Alu insertion could also have negative consequences and could induce damage to the human genome.

4. Alu-Mediated Recombination and Insertional Mutagenesis Contribution to Human Diseases

Several genetic disorders can result from different types of mutations that arise following the insertion of an Alu retroelement. The human genome project hg18 identified 584 human reference-specific Alu insertions [43]. Alu insertion can influence the genome stability, and it accounts for 0.1% of all human genetic disorders [9] such as hereditary desmoid disease [50], cystic fibrosis [51], Dent's disease [52, 53], X-linked agammaglobulinemia [54–57], hemophilia A and B [58–60], autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome [61], Apert syndrome [62], neurofibromatosis type 1 [63], benign isolated glycerol kinase deficiency [64], hyper IgM with immunodeficiency syndrome [65], Menkes disease [66], Alstrom syndrome [67], retinitis pigmentosa [68], acholinesterasemia [69], autosomal dominant optic atrophy [70], hemolytic anemia [24], autosomal branchio-oto-renal syndrome [71], acute intermittent porphyria [72], mucolipidosis II [73], and several type of cancer [23, 74–77] to cite a few. There are several mechanisms by which Alu can alter genomic structure. In addition to the potential impact of Alu retroelement insertions in causing human diseases, their broad dispersion throughout the genome provides opportunity for unequal homologous recombination and cross-over. Recombination between Alu retroelements on the same chromosome results in either duplication or deletion of the sequences between the Alus. When the recombination occurs on different chromosomes, it leads to chromosomal translocations or rearrangements. Several human diseases have been reported to be associated with Alu recombination events such as Gaucher's disease [78], hypercholesterolemia [79–82], chronic granulomatous disease [83], α-thalassaemia [84, 85], diabetes [86], thrombophilia [87], hypobetalipoproteinemia [88], and spastic paraplegia type 11 [89].

The vast majority of Alu insertions that have led to human disease insert into coding exons, near the promoter/enhancer regions, or into introns relatively near an exon. Alu insertions contribute to disease by either altering the transcription of a gene by affecting its promoter (changing the methylation status or introducing an additional regulatory sequence) or disrupting a coding region, or disrupting the splicing of a gene. These mechanisms have been intensively discussed previously, and the reader is directed to several elegant reviews [11, 90–92]. Although Alu elements are broadly spread throughout the human genome, some genes, chromosomes, and regions seem to be more prone to disease-causing insertions than others.

5. Alu RNA Accumulation Induces Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)

Alu RNA expression and accumulation, rather than retrotransposition, insertion, or recombination per se, has been recently shown to be involved in the advanced “dry” age-related macular degeneration disease [10], the leading cause of blindness in elderly worldwide [10, 93]. This atrophic form, geographic atrophy (GA), involves alterations of pigment distribution, loss of RPE cells and photoreceptors and diminished retinal function due to an overall atrophy of the cells [94]. All studies confirm the strong age dependence of the disease, which likely arises from a complex interaction of metabolic, functional, genetic, and environmental factors [95–97]. Although the molecular mechanisms underpinning this disease are not completely understood, there is intriguing evidence that exogenous double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) can activate toll-like receptor-3- (TLR3-) mediated inflammatory and chemokine protein secretion and -induced RPE cell death [98–100]. TLR3 knockout mice are protected against RPE degeneration induced by exogenous dsRNAs [100]. The phenomenon observed in mouse model for AMD has led to the hypothesis that the activation of TLR3 by endogenous dsRNAs may cause AMD in humans. Kaneko and coworkers [10] detected abundant dsRNA immunoreactivity in the RPE from diseased but not normal human eyes. Sequence-independent amplification of these immunoprecipitated and isolated dsRNAs showed amplicons belongs to the Alu Sq subfamily (GenBank accession nos. HN176584 and HN176585). It has become clear that bidirectional transcription and dsRNA formation are more prevalent than had been previously thought [101–103]. Alus are capable of folding back to generate hairpin structures. Two close (<2 kb) Alu elements in opposite orientation might base pair leading to the formation of a long stable dsRNA and becoming a major target for adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADARs) A-to-I editing [104]. Although the precise role of RNA editing is still speculative, it might influence the stability of dsRNA and its nuclear retention [105–107]. Alu RNAs seem to be free and nonembedded polymerase III transcripts [10] and were accumulated mainly in the cytoplasm of RPE cells indicating that they might escape ADARs editing and nuclear retention. However, there are no available data, to the best of our knowledge, concerning ADARs and paraspeckle-associated complex activity in the RPE from GA compared to normal eye, and this area will undoubtedly need further investigations. Once in the cytoplasm, Alus should be cleaved by DICER1 since they have been shown to be substrates for DICER1. The RNase DICER1, micro RNA- (miRNA-) processing key enzyme, has been shown to be dramatically downregulated in the RPE from GA compared to normal eye which explains the accumulation of Alu RNAs [10]. Interestingly, DICER1 which is also expressed in the nucleus of RPE cells and its function (whether dicing Alu or not) as well as its nuclear expression levels in GA compared to normal eye are still unknown. In parallel experiment in mice, loss of Dicer1 induced B1/B2 (Alu-like elements) accumulation and RPE cell degeneration. Alternatively, this leads to additional biological questions such as in normal conditions where DICER1 is fully functional, what are the Alu- (or B1/B2-) cleaved products? How long are they? And what is (are) their biological function(s)?

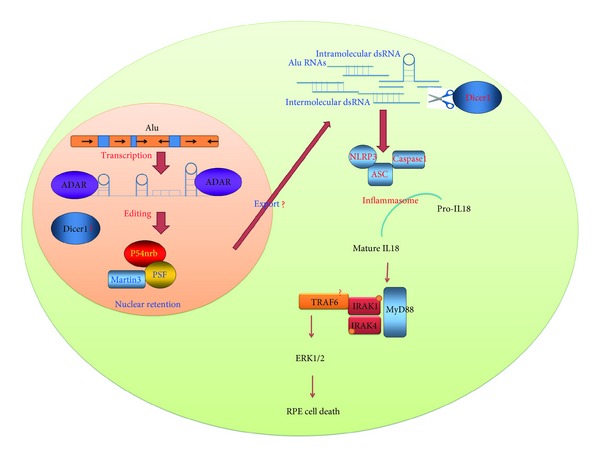

Unexpectedly and in contrast to exogenous dsRNAs, Alus induced RPE cell death independently of miRNA and TLR3 as well as a variety of other TLRs and RNA sensors [108]. In vivo and in vitro functional studies showed that Alus induced RPE cell death via innate immune sensing pathway and activated NLR family, pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome [108]. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome triggered activation of caspase-1 and induced maturation of interleukin-18 (IL-18) which in turn activated the myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) pathway (phosphorylation of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-1 and -4 (IRAK1 and IRAK4)) [108] (Figure 2). The effect of Alu RNA on RPE cell degeneration was mediated also via activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 MAPK [109]; however, the up- and downstream cascades are still unknown and further investigations are warranted. It is conceivable that ERK1/2 activation might be downstream of IL-18 and MyD88 [110–112], and several other potential Alu-mediated signaling pathways might be involved.

Figure 2.

Model for the fate of Alu RNAs in the RPE from GA eye. Alus can form long duplex RNA structures and pose as targets for ADAR A-to-I RNA editing activity. The edited Alu RNAs may be bound by the paraspeckle that contains the nuclear proteins P54nrb, PSF and martin 3 and are expected to be retained on the nuclear matrix in normal eye. In diseased eye, DICER1 is dysregulated and Alu RNAs are exported and accumulated in the cytoplasm leading to the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and MyD88, which in turn may activate ERK1/2 and induce RPE cell degeneration.

6. ADAR Gene Family and Alu RNA Editing

The adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs) are proteins that bind to double-stranded RNA and cause the modification of adenosine to inosine via a hydrolytic deamination reaction [113]. Editing of RNA from A to I in the coding regions of specific genes can lead to functional alterations of the protein product [114, 115], whereas editing of the noncoding regions may affect splicing, stability, or the translational efficiency of these target mRNAs [116, 117]. The precise role of RNA editing is still speculative, and ADAR may act as an antiviral defense mechanism against dsRNA viruses [118], or antagonize dsRNA subjected to the RNAi-mediated gene silencing pathway [119, 120], and/or against dsRNA formed by Alu repeat elements or by sense and antisense transcripts.

Three ADAR family members have been identified [121–125], and they are conserved in their C-terminal deaminase region as well as in their double-stranded RNA-binding domains. Mammalian ADAR1 and ADAR2 are ubiquitously expressed in many tissues; however, ADAR3 is mainly expressed in the brain [126]. ADAR3 has been shown to contain both single- and double-stranded RNA-binding domains. The dsRBDs of ADARs resemble those of dsRNA-activated protein kinase PKR which is an interferon inducible involved in antiviral mechanisms [127, 128] as well as Drosha and Dicer, key enzymes involved in miRNA biogenesis [129]. The ADAR editing efficiency increases with longer dsRNA [130]. RNA secondary structural features consisting of hairpins containing mismatches, bulges, and loops are edited more selectively than completely base-paired duplex RNA. The editing efficiency depends also on the sequence context of nucleotides surrounding the adenosine moiety to be edited [131]. Intriguingly ADAR3 is not active on the other known substrates of ADAR1/2 or on long dsRNA in vitro. ADARs act as a dimer in mammals, and ADAR1 and 2 do not form heterodimers and must form homodimers to be active [132]; however, ADAR3 does not dimerize which explains its lack of activity. There are two isoforms of ADAR1, the longer ADAR1p150 which is expressed in the cytoplasm and the nucleus and the shorter ADAR1p110 which remains in the nucleus [133]. Both isoforms harbor a nuclear localization signal [134]. Both ADAR1 and ADAR2 are present in the nucleolar compartment and are translocated to the nucleoplasm upon the presence of an active editing substrate [135, 136]. They are upregulated by inflammation and in presence of mRNA rich in inosine [137]. The ADARs proteins as well as their dsRNA substrates that mediate the A-to-I editing are important, and both of them determine what will be the overall effect of RNA editing.

Alus are the major targets of ADAR A-to-I editing [104, 138–141] because they create long hairpin structures for which ADARs can deaminate. A computational analysis showed that 88% of the A-to-I editing events were found to be located in the Alus, even though they only comprise 20% of the total length of transcripts [140], and the editing was found to be the most prevalent in the brain compared to other tissues [139]. One may ask a question whether the Alu hairpin structures upon editing become more stable or unstable (reduced in its double strandness)? Previous studies are inconsistent; Levanon's and Blow's groups [139, 141] indicated that the effect of editing is aimed at destabilization of Alu dsRNA; however, Athanasiadis et al. [104] suggested that the overall effect is to stabilize the Alu dsRNA and this area need further investigations. The next question is what are the functional and biological consequences of Alu editing by ADARs? As the authors mentioned previously, Alu editing by ADARs may regulate the transcriptional activities of Alu during cellular stress or affect processing, stability (destability), nuclear retention, and export of Alu RNAs. While there is no direct biochemical evidence for RNAi-mediated chromatin silencing in higher eukaryotes, there is hypothesis that in mammalian cells nuclear dsRNA can induce transcriptional gene silencing associated with DNA methylation [142]. Furthermore, recent studies indicate a direct connection of the involvement of ADARs in the RNAi gene silencing pathway [143].

6.1. Other Cellular Mechanisms That May Deal with Alu dsRNAs

More than twenty proteins harboring dsRNA-binding domains (DRBPs) have been identified, and there are several distinct ways in which dsRNAs might be detected and resolved. The nuclear factors associated with dsRNA (NFAR) [144–147], nuclear members of the DRBPs, may interact with Alu dsRNA, although Alu dsRNAs induce RPE cell degeneration independently of PKR [108] and NFARs are physically associated with PKR, and they may function in PKR-mediated signaling events in the cell [147]. Alu dsRNA may also interact with spermatid perinuclear RNA-binding protein (SPNR) which is expressed in several tissues including testis, ovary, and brain. Although SPNR protein expression is limited to testis, neurological defects in mice lacking SPNR function indicate other roles for SPNR outside spermatogenesis [148]. Alu dsRNA might be degraded by dsRNA-specific nucleases [149] or unwound by dsRNA helicases [150, 151]. The RNA helicase A (RHA) has two DRBPs and binds to dsRNA as well as to ssRNA and ssDNA through a carboxyl-terminal RGG box [152, 153]. Other nuclear members of DRBPs such as the negative regulatory element binding protein (NREBP) [154, 155] and kanadaptin [156, 157] may interact with Alu dsRNA, although their role is still speculative. We have shown that Dicer dysregulation induced Alu accumulation and cytotoxicity in RPE cells, but we cannot rule out a potential involvement of other cytoplasmic members of DRBPs such as protein activator of PKR (PACT) [158] and staufen [159], and further studies are needed to determine whether Alu dsRNA binds to these nuclear and cytoplasmic DRBPs and their biological relevance in normal and diseased eye.

7. Concluding Remarks

Repeat elements are landscape-determining components of our genome, and they are “hot spots” elements that can affect our health through at least two known different mechanisms: (1) self-propagation and retrotransposition and (2) accumulation and cytotoxicity. Still, several questions remain unresolved: why and how Alu RNAs accumulate in the RPE of GA patients? It is possible that chronic stress insults (oxidative stress, heat shock, viral infection, etc.) in combination with increasing age and senescence induce Alu RNA accumulation [160–163]. Another important question is: are Alu RNAs accumulated in other age-related neurodegenerative diseases? However, some studies have suggested that the central nervous system is a privileged environment for transposition. In addition, DICER1 and the fine tuning of the miRNA gene network have been shown to be crucial for neuronal integrity. Indeed, genetic ablation of DICER1 induces neurodegeneration via hyperphosphorylation of tau protein and activation of ERK1/2 [164, 165]. Furthermore, the NALP3 inflammasome has been shown to be involved in Alzheimer's disease (AD) [166]. Altered DICER1 and miRNA regulation have been shown to be involved in other neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington's [167] and Parkinson's diseases [168]; however, the Alu RNA profiling has not been reported yet.

The new sequencing technologies combined with rigorous functional analyses are available to study the mobilome, and they will certainly yield more valuable insights into both functional properties of the genomic gems and disease pathogenesis.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Whitfield R., Bennett B., and Albright J. for the discussions.

References

- 1.Rogers J. Retroposons defined. Nature. 1983;301(5900, article 460) doi: 10.1038/301460e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathias SL, Scott AF, Kazazian HH, Jr., Boeke JD, Gabriel A. Reverse transcriptase encoded by a human transposable element. Science. 1991;254(5039):1808–1810. doi: 10.1126/science.1722352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dewannieux M, Esnault C, Heidmann T. LINE-mediated retrotransposition of marked Alu sequences. Nature Genetics. 2003;35(1):41–48. doi: 10.1038/ng1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmid CW, Jelinek WR. The Alu family of dispersed repetitive sequences. Science. 1982;216(4550):1065–1070. doi: 10.1126/science.6281889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen TA, von Kaenel S, Goodrich JA, Kugel JF. The SINE-encoded mouse B2 RNA represses mRNA transcription in response to heat shock. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2004;11(9):816–821. doi: 10.1038/nsmb813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espinoza CA, Allen TA, Hieb AR, Kugel JF, Goodrich JA. B2 RNA binds directly to RNA polymerase II to repress transcript synthesis. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2004;11(9):822–829. doi: 10.1038/nsmb812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mariner PD, Walters RD, Espinoza CA, et al. Human Alu RNA is a modular transacting repressor of mRNA transcription during heat shock. Molecular Cell. 2008;29(4):499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lev-Maor G, Sorek R, Shomron N, Ast G. The birth of an alternatively spliced exon: 3' Splice-site selection in Alu exons. Science. 2003;300(5623):1288–1291. doi: 10.1126/science.1082588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deininger PL, Batzer MA. Alu repeats and human disease. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 1999;67(3):183–193. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaneko H, Dridi S, Tarallo V, et al. DICER1 deficit induces Alu RNA toxicity in age-related macular degeneration. Nature. 2011;471:325–330. doi: 10.1038/nature09830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batzer MA, Deininger PL. Alu repeats and human genomic diversity. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2002;3(5):370–379. doi: 10.1038/nrg798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gundelfinger ED, di Carlo M, Zopf D, Melli M. Structure and evolution of the 7SL RNA component of the signal recognition particle. The EMBO Journal. 1984;3(10):2325–2332. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ullu E, Tschudi C. Alu sequences are processed 7SL RNA genes. Nature. 1984;312(5990):171–172. doi: 10.1038/312171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegel V, Walter P. Removal of the Alu structural domain from signal recognition particle leaves its protein translocation activity intact. Nature. 1986;320(6057):81–84. doi: 10.1038/320081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmid CW. Alu: a parasite’s parasite? Nature Genetics. 2003;35(1):15–16. doi: 10.1038/ng0903-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waterston RH, Lindblad-Toh K, Birney E, et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420:520–562. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quentin Y. A master sequence related to a free left Alu monomer (FLAM) at the origin of the B1 family in rodent genomes. Nucleic Acids Research. 1994;22(12):2222–2227. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.12.2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labuda D, Sinnett D, Richer C, Deragon JM, Striker G. Evolution of mouse B1 repeats: 7SL RNA folding pattern conserved. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1991;32(5):405–414. doi: 10.1007/BF02101280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krayev AS, Markusheva TV, Kramerov DA, et al. Ubiquitous transposon-like repeats B1 and B2 of the mouse genome: B2 sequencing. Nucleic Acids Research. 1982;10(23):7461–7475. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.23.7461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daniels GR, Deininger PL. Repeat sequence families derived from mammalian tRNA genes. Nature. 1985;317(6040):819–822. doi: 10.1038/317819a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Deininger PL. Recent amplification of rat ID sequences. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1996;261(3):322–327. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serdobova IM, Kramerov DA. Short retroposons of the B2 superfamily: evolution and application for the study of rodent phylogeny. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1998;46(2):202–214. doi: 10.1007/pl00006295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin CS, Goldthwait DA, Samols D. Identification of Alu transposition in human lung carcinoma cells. Cell. 1988;54(2):153–159. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90547-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manco L, Relvas L, Pinto CS, Pereira J, Almeida AB, Ribeiro ML. Molecular characterization of five Portuguese patients with pyrimidine 5'-nucleotidase deficient hemolytic anemia showing three new P5’N-I mutations. Haematologica. 2006;91(2):266–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt CW, Deininger PL. Sequence organization of the human genome. Cell. 1975;6(3):345–358. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Houck CM, Rinehart FP, Schmid CW. A ubiquitous family of repeated DNA sequences in the human genome. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1979;132(3):289–306. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin CM, Houck CM, Deininger PL. Partial nucleotide sequence of the 300-nucleotide interspersed repeated human DNA sequences. Nature. 1980;284(5754):372–374. doi: 10.1038/284372a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen MR, Brosius J, Deininger PL. BC1 RNA, the transcript from a master gene for ID element amplification, is able to prime its own reverse transcription. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25(8):1641–1648. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.8.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng Q, Moran JV, Kazazian HH, Boeke JD. Human L1 retrotransposon encodes a conserved endonuclease required for retrotransposition. Cell. 1996;87(5):905–916. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81997-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moran JV, Holmes SE, Naas TP, DeBerardinis RJ, Boeke JD, Kazazian HH., Jr. High frequency retrotransposition in cultured mammalian cells. Cell. 1996;87(5):917–927. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81998-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jurka J. Sequence patterns indicate an enzymatic involvement in integration of mammalian retroposons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(5):1872–1877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boeke JD. LINEs and Alus—the polyA connection. Nature Genetics. 1997;16(1):6–7. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slagel V, Flemington E, Traina-Dorge V. Clustering and subfamily relationships of the Alu family in the human genome. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1987;4(1):19–29. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deininger PL, Slagel VK. Recently amplified Alu family members share a common parental Alu sequence. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1988;8(10):4566–4569. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.10.4566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jurka J, Smith T. A fundamental division in the Alu family of repeated sequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85(13):4775–4778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hutchinson GB, Andrew SE, McDonald H, et al. An Alu element retroposition in two families with Huntington disease defines a new active Alu subfamily. Nucleic Acids Research. 1993;21(15):3379–3383. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.15.3379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jurka J. A new subfamily of recently retroposed human Alu repeats. Nucleic Acids Research. 1993;21(9):p. 2252. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.9.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Batzer MA, Deininger PL, Hellmann-Blumberg U, et al. Standardized nomenclature for Alu repeats. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1996;42(1):3–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00163204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen MR, Batzer MA, Deininger PL. Evolution of the master Alu gene(s) Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1991;33(4):311–320. doi: 10.1007/BF02102862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deininger PL, Batzer MA, Hutchison CA, Edgell MH. Master genes in mammalian repetitive DNA amplification. Trends in Genetics. 1992;8(9):307–311. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roy AM, Carroll ML, Kass DH, et al. Recently integrated human Alu repeats: finding needles in the haystack. Genetica. 1999;107(1–3):149–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xing J, Zhang Y, Han K, et al. Mobile elements create structural variation: analysis of a complete human genome. Genome Research. 2009;19(9):1516–1526. doi: 10.1101/gr.091827.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Batzer MA, Stoneking M, Alegria-Hartman M, et al. African origin of human-specific polymorphic Alu insertions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(25):12288–12292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stoneking M, Fontius JJ, Clifford SL, et al. Alu insertion polymorphisms and human evolution: evidence for a larger population size in Africa. Genome Research. 1997;7(11):1061–1071. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.11.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watkins WS, Ricker CE, Bamshad MJ, et al. Patterns of ancestral human diversity: an analysis of Alu-insertion and restriction-site polymorphisms. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2001;68(3):738–752. doi: 10.1086/318793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Medstrand P, van de Lagemaat LN, Mager DL. Retroelement distributions in the human genome: variations associated with age and proximity to genes. Genome Research. 2002;12(10):1483–1495. doi: 10.1101/gr.388902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hedges DJ, Callinan PA, Cordaux R, Xing J, Barnes E, Batzer MA. Differential Alu mobilization and polymorphism among the human and chimpanzee lineages. Genome Research. 2004;14(6):1068–1075. doi: 10.1101/gr.2530404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mills RE, Bennett EA, Iskow RC, et al. Recently mobilized transposons in the human and chimpanzee genomes. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2006;78(4):671–679. doi: 10.1086/501028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Halling KC, Lazzaro CR, Honchel R, et al. Hereditary desmoid disease in a family with a germline Alu I repeat mutation of the APC gene. Human Heredity. 1999;49(2):97–102. doi: 10.1159/000022852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen JM, Masson E, Macek M, et al. Detection of two Alu insertions in the CFTR gene. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 2008;7(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Claverie-Martin F, González-Acosta H, Flores C, Antón-Gamero M, García-Nieto V. De novo insertion of an Alu sequence in the coding region of the CLCN5 gene results in Dent’s disease. Human Genetics. 2003;113(6):480–485. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0991-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Claverie-Martín F, Flores C, Antón-Gamero M, González-Acosta H, García-Nieto V. The Alu insertion in the CLCN5 gene of a patient with Dent’s disease leads to exon 11 skipping. Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;50(7):370–374. doi: 10.1007/s10038-005-0265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rohrer J, Minegishi Y, Richter D, Eguiguren J, Conley ME. Unusual mutations in Btk: an insertion, a duplication, an inversion, and four large deletions. Clinical Immunology. 1999;90(1):28–37. doi: 10.1006/clim.1998.4629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jo EK, Wang Y, Kanegane H, et al. Identification of mutations in the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase gene, including a novel genomic rearrangements resulting in large deletion, in Korean X-linked agammaglobulinemia patients. Journal of Human Genetics. 2003;48(6):322–326. doi: 10.1007/s10038-003-0032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kristufek D, Aspalter RM, Eibl MM, Wolf HM. Characterization of novel Bruton’s tyrosine kinase gene mutations in Central European patients with agammaglobulinemia. Molecular Immunology. 2007;44(7):1639–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arai T, Zhao M, Kanegane H, et al. Genetic analysis of contiguous X-chromosome deletion syndrome encompassing the BTK and TIMM8A genes. Journal of Human Genetics. 2011;56:577–582. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vidaud D, Vidaud M, Bahnak BR, et al. Haemophilia B due to a de novo insertion of a human-specific Alu subfamily member within the coding region of the factor IX gene. European Journal of Human Genetics. 1993;1(1):30–36. doi: 10.1159/000472385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sukarova E, Dimovski AJ, Tchacarova P, Petkov GH, Efremov GD. An Alu insert as the cause of a severe form of hemophilia A. Acta Haematologica. 2001;106(3):126–129. doi: 10.1159/000046602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ganguly A, Dunbar T, Chen P, Godmilow L, Ganguly T. Exon skipping caused by an intronic insertion of a young Alu Yb9 element leads to severe hemophilia A. Human Genetics. 2003;113(4):348–352. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0986-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tighe PJ, Stevens SE, Dempsey S, le Deist F, Rieux-Laucat F, Edgar JD. Inactivation of the Fas gene by Alu insertion: retrotransposition in an intron causing splicing variation and autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Genes and Immunity. 2002;3(Supplement 1):S66–S70. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oldridge M, Zackai EH, McDonald-McGinn DM, et al. De novo Alu-element insertions in FGFR2 identify a distinct pathological basis for Apert syndrome. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1999;64(2):446–461. doi: 10.1086/302245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wallace MR, Andersen LB, Saulino AM, Gregory PE, Glover TW, Collins FS. A de novo Alu insertion results in neurofibromatosis type 1. Nature. 1991;353(6347):864–866. doi: 10.1038/353864a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang Y, Dipple KM, Vilain E, et al. AluY insertion (IVS4-52ins316Alu) in the glycerol kinase gene from an individual with benign glycerol kinase deficiency. Human Mutation. 2000;15:316–323. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200004)15:4<316::AID-HUMU3>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Apoil PA, Kuhlein E, Robert A, Rubie H, Blancher A. HIGM syndrome caused by insertion of an AluYb8 element in exon 1 of the CD40LG gene. Immunogenetics. 2007;59(1):17–23. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gu Y, Kodama H, Watanabe S, et al. The first reported case of Menkes disease caused by an Alu insertion mutation. Brain and Development. 2007;29(2):105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taskesen M, Collin GB, Evsikov AV, et al. Novel Alu retrotransposon insertion leading to Alstrom syndrome. Human Genetics. 2012;131:407–413. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1083-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tucker BA, Scheetz TE, Mullins RF, et al. Exome sequencing and analysis of induced pluripotent stem cells identify the cilia-related gene male germ cell-associated kinase (MAK) as a cause of retinitis pigmentosa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencesof the USA. 2011;108:E569–E576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108918108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Muratani K, Hada T, Yamamoto Y, et al. Inactivation of the cholinesterase gene by Alu insertion: possible mechanism for human gene transposition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88(24):11315–11319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gallus GN, Cardaioli E, Rufa A, et al. Alu-element insertion in an OPA1 intron sequence associated with autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Molecular Vision. 2010;16:178–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abdelhak S, Kalatzis V, Heilig R, et al. Clustering of mutations responsible for branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome in the eyes absent homologous region (eyaHR) of EYA1. Human Molecular Genetics. 1997;6(13):2247–2255. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.13.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mustajoki S, Ahola H, Mustajoki P, Kauppinen R. Insertion of Alu element responsible for acute intermittent porphyria. Human Mutation. 1999;13:431–438. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:6<431::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tappino B, Regis S, Corsolini F, Filocamo M. An Alu insertion in compound heterozygosity with a microduplication in GNPTAB gene underlies Mucolipidosis II. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2008;93(2):129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rowe SM, Coughlan SJ, McKenna NJ, et al. Ovarian carcinoma-associated TaqI restriction fragment length polymorphism in intron G of the progesterone receptor gene is due to an Alu sequence insertion. Cancer Research. 1995;55(13):2743–2745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Miki Y, Katagiri T, Kasumi F, Yoshimoto T, Nakamura Y. Mutation analysis in the BRCA2 gene in primary breast cancers. Nature Genetics. 1996;13(2):245–247. doi: 10.1038/ng0696-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang T, Lerer I, Gueta Z, et al. A deletion/insertion mutation in the BRCA2 gene in a breast cancer family: a possible role of the Alu-polyA tail in the evolution of the deletion. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2001;31(1):91–95. doi: 10.1002/gcc.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Amit M, Sela N, Keren H, et al. Biased exonization of transposed elements in duplicated genes: a lesson from the TIF-IA gene. BMC Molecular Biology. 2007;8, article 109 doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-8-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cozar M, Bembi B, Dominissini S, et al. Molecular characterization of a new deletion of the GBA1 gene due to an inter Alu recombination event. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2011;102(2):226–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lehrman MA, Schneider WJ, Sudhof TC. Mutation in LDL receptor: Alu-Alu recombination deletes exons encoding transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. Science. 1985;227(4683):140–146. doi: 10.1126/science.3155573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lehrman MA, Goldstein JL, Russell DW, Brown MS. Duplication of seven exons in LDL receptor gene caused by Alu-Alu recombination in a subject with familial hypercholesterolemia. Cell. 1987;48(5):827–835. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chae JJ, Park YB, Kim SH, et al. Two partial deletion mutations involving the same Alu sequence within intron 8 of the LDL receptor gene in Korean patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. Human Genetics. 1997;99(2):155–163. doi: 10.1007/s004390050331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goldmann R, Tichy L, Freiberger T, et al. Genomic characterization of large rearrangements of the LDLR gene in Czech patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. BMC Medical Genetics. 2010;11, article 115 doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gentsch M, Kaczmarczyk A, Van Leeuwen K, et al. Alu-repeat-induced deletions within the NCF2 gene causing p67-phox-deficient chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) Human Mutation. 2010;31(2):151–158. doi: 10.1002/humu.21156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nicholls RD, Fischel-Ghodsian N, Higgs DR. Recombination at the human α-globin gene cluster: sequence features and topological constraints. Cell. 1987;49(3):369–378. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Harteveld KL, Losekoot M, Fodde R, Giordano PC, Bernini LF. The involvement of Alu repeats in recombination events at the α-globin gene cluster: characterization of two α(o)-thalassaemia deletion breakpoints. Human Genetics. 1997;99(4):528–534. doi: 10.1007/s004390050401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shimada F, Taira M, Suzuki Y, et al. Insulin-resistant diabetes associated with partial deletion of insulin-receptor gene. The Lancet. 1990;335(8699):1179–1181. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92695-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rouyer F, Simmler MC, Page DC, Weissenbach J. A sex chromosome rearrangement in a human XX male caused by Alu-Alu recombination. Cell. 1987;51(3):417–425. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90637-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Huang LS, Ripps ME, Korman SH, Deckelbaum RJ, Breslow JL. Hypobetalipoproteinemia due to an apolipoprotein B gene exon 21 deletion derived by Alu-Alu recombination. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264(19):11394–11400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pereira MC, Loureiro JL, Pinto-Basto J, et al. Alu elements mediate large SPG11 gene rearrangements: further spatacsin mutations. Genetics in Medicine. 2012;14:143–151. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Häsler J, Strub K. Alu elements as regulators of gene expression. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34(19):5491–5497. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Walters RD, Kugel JF, Goodrich JA. InvAluable junk: the cellular impact and function of Alu and B2 RNAs. IUBMB Life. 2009;61(8):831–837. doi: 10.1002/iub.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Burns KH, Boeke JD. Human transposon tectonics. Cell. 2012;149:740–752. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Friedman DS, O’Colmain BJ, Muñoz B, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2004;122(4):564–572. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ambati J, Ambati BK, Yoo SH, Ianchulev S, Adamis AP. Age-related macular degeneration: etiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic strategies. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2003;48(3):257–293. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(03)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ambati J, Fowler BJ. Mechanisms of age-related macular degeneration. Neuron. 2012;75:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Khandhadia S, Cherry J, Lotery AJ. Age-related macular degeneration. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2012;724:15–36. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0653-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lim LS, Mitchell P, Seddon JM, Holz FG, Wong TY. Age-related macular degeneration. The Lancet. 2012;379:1728–1738. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shiose S, Chen Y, Okano K, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 is required for development of retinopathy caused by impaired all-trans-retinal clearance in mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(17):15543–15555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.228551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wornle M, Merkle M, Wolf A, et al. Inhibition of TLR3-mediated proinflammatory effects by Alkylphosphocholines in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2011;52:6536–6544. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kleinman ME, Kaneko H, Cho WG, et al. Short-interfering RNAs induce retinal degeneration via TLR3 and IRF3. Molecular Therapy. 2012;20:101–108. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lehner B, Williams G, Campbell RD, Sanderson CM. Antisense transcripts in the human genome. Trends in Genetics. 2002;18(2):63–65. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02598-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yelin R, Dahary D, Sorek R, et al. Widespread occurrence of antisense transcription in the human genome. Nature Biotechnology. 2003;21(4):379–386. doi: 10.1038/nbt808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chen J, Sun M, Kent WJ, et al. Over 20% of human transcripts might form sense-antisense pairs. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32(16):4812–4820. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Athanasiadis A, Rich A, Maas S. Widespread A-to-I RNA editing of Alu-containing mRNAs in the human transcriptome. PLoS Biology. 2004;2(12, article e391) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhang Z, Carmichael GG. The fate of dsRNA in the Nucleus: a p54nrb-containing complex mediates the nuclear retention of promiscuously A-to-I edited RNAs. Cell. 2001;106(4):465–475. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00466-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.DeCerbo J, Carmichael GG. Retention and repression: fates of hyperedited RNAs in the nucleus. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2005;17(3):302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chen LL, Carmichael GG. Altered nuclear retention of mRNAs containing inverted repeats in human embryonic stem cells: functional role of a nuclear noncoding RNA. Molecular Cell. 2009;35(4):467–478. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tarallo V, Hirano Y, Gelfand BD, et al. DICER1 loss and Alu RNA induce age-related macular degeneration via the NLRP3 inflammasome and MyD88. Cell. 2012;149:847–859. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dridi S, Hirano Y, Tarallo V, et al. ERK1/2 activation is a therapeutic target in age-related macular degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2012;109:13781–13786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206494109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kalina U, Kauschat D, Koyama N, et al. IL-18 activates STAT3 in the natural killer cell line 92, augments cytotoxic activity, and mediates IFN-γ production by the stress kinase p38 and by the extracellular regulated kinases p44(erk-1) and p42(erk-21) Journal of Immunology. 2000;165(3):1307–1313. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yang H, Wang H, Czura CJ, Tracey KJ. The cytokine activity of HMGB1. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2005;78(1):1–8. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1104648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.McNamara N, Gallup M, Sucher A, Maltseva I, McKemy D, Basbaum C. AsialoGM1 and TLR5 cooperate in flagellin-induced nucleotide signaling to activate Erk1/2. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2006;34(6):653–660. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0441OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wagner RW, Smith JE, Cooperman BS, Nishikura K. A double-stranded RNA unwinding activity introduces structural alterations by means of adenosine to inosine conversions in mammalian cells and Xenopus eggs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86(8):2647–2651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Seeburg PH. A-to-I editing: new and old sites, functions and speculations. Neuron. 2002;35(1):17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00760-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hoopengardner B, Bhalla T, Staber C, Reenan R. Nervous system targets of RNA editing identified by comparative genomics. Science. 2003;301(5634):832–836. doi: 10.1126/science.1086763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rueter SM, Dawson TR, Emeson RB. Regulation of alternative splicing by RNA editing. Nature. 1999;399(6731):75–80. doi: 10.1038/19992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Morse DP, Aruscavage PJ, Bass BL. RNA hairpins in noncoding regions of human brain and Caenorhabditis elegans mRNA are edited by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(12):7906–7911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112704299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Scadden ADJ, Smith CWJ. Specific cleavage of hyper-edited dsRNAs. The EMBO Journal. 2001;20(15):4243–4252. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Knight SW, Bass BL. The role of RNA editing by ADARs in RNAi. Molecular Cell. 2002;10(4):809–817. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00649-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Luciano DJ, Mirsky H, Vendetti NJ, Maas S. RNA editing of a miRNA precursor. RNA. 2004;10(8):1174–1177. doi: 10.1261/rna.7350304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kim U, Wang Y, Sanford T, Zeng Y, Nishikura K. Molecular cloning of cDNA for double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminase, a candidate enzyme for nuclear RNA editing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(24):11457–11461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.O’Connell MA, Krause S, Higuchi M, et al. Cloning of cDNAs encoding mammalian double-stranded RNA-specific adenosine deaminase. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1995;15(3):1389–1397. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Melcher T, Maas S, Herb A, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH, Higuchi M. A mammalian RNA editing enzyme. Nature. 1996;379(6564):460–464. doi: 10.1038/379460a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lai F, Chen CX, Carter KC, Nishikura K. Editing of glutamate receptor B subunit ion channel RNAs by four alternatively spliced DRADA2 double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminases. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1997;17(5):2413–2424. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Chen CX, Cho DSC, Wang Q, Lai F, Carter KC, Nishikura K. A third member of the RNA-specific adenosine deaminase gene family, ADAR3, contains both single- and double-stranded RNA binding domains. RNA. 2000;6(5):755–767. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Melcher T, Maas S, Herb A, Sprengel R, Higuchi M, Seeburg PH. RED2, a brain-specific member of the RNA-specific adenosine deaminase family. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(50):31795–31798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Proud CG. PKR: a new name and new roles. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1995;20(6):241–246. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Clemens MJ. PKR—a protein kinase regulated by double-stranded RNA. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 1997;29(7):945–949. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Saunders LR, Barber GN. The dsRNA binding protein family: critical roles, diverse cellular functions. The FASEB Journal. 2003;17(9):961–983. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0958rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Herbert A, Rich A. The role of binding domains for dsRNA and Z-DNA in the in vivo editing of minimal substrates by ADAR1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(21):12132–12137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211419898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Dawson TR, Sansam CL, Emeson RB. Structure and sequence determinants required for the RNA editing of ADAR2 substrates. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(6):4941–4951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Cho DSC, Yang W, Lee JT, Shiekhattar R, Murray JM, Nishikura K. Requirement of dimerization for RNA editing activity of adenosine deaminases acting on RNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(19):17093–17102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213127200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Patterson JB, Samuel CE. Expression and regulation by interferon of a double-stranded-RNA-specific adenosine deaminase from human cells: evidence for two forms of the deaminase. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1995;15(10):5376–5388. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Eckmann CR, Neunteufl A, Pfaffstetter L, Jantsch MF. The human but not the Xenopus RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1 has an atypical nuclear localization signal and displays the characteristics of a shuttling protein. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2001;12(7):1911–1924. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.7.1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Desterro JMP, Keegan LP, Lafarga M, Berciano MT, O’Connell M, Carmo-Fonseca M. Dynamic association of RNA-editing enzymes with the nucleolus. Journal of Cell Science. 2003;116(9):1805–1818. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sansam CL, Wells KS, Emeson RB. Modulation of RNA editing by functional nucleolar sequestration of ADAR2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(2):14018–14023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336131100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Yang JH, Luo X, Nie Y, et al. Widespread inosine-containing mRNA in lymphocytes regulated by ADAR1 in response to inflammation. Immunology. 2003;109(1):15–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kikuno R, Nagase T, Waki M, Ohara O. HUGE: a database for human large proteins identified in the Kazusa cDNA sequencing project. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30(1):166–168. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Blow M, Futreal AP, Wooster R, Stratton MR. A survey of RNA editing in human brain. Genome Research. 2004;14(12):2379–2387. doi: 10.1101/gr.2951204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kim DDY, Kim TTY, Walsh T, et al. Widespread RNA editing of embedded Alu elements in the human transcriptome. Genome Research. 2004;14(9):1719–1725. doi: 10.1101/gr.2855504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Levanon EY, Eisenberg E, Yelin R, et al. Systematic identification of abundant A-to-I editing sites in the human transcriptome. Nature Biotechnology. 2004;22(8):1001–1005. doi: 10.1038/nbt996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Tufarelli C, Sloane Stanley JA, Garrick D, et al. Transcription of antisense RNA leading to gene silencing and methylation as a novel cause of human genetic disease. Nature Genetics. 2003;34(2):157–165. doi: 10.1038/ng1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Yang W, Wang Q, Howell KL, et al. ADAR1 RNA deaminase limits short interfering RNA efficacy in mammalian cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(5):3946–3953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407876200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Liao HJ, Kobayashi R, Mathews MB. Activities of adenovirus virus-associated RNAs: purification and characterization of RNA binding proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(15):8514–8519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Langland JO, Kao PN, Jacobs BL. Nuclear factor-90 of activated T-cells: a double-stranded RNA-binding protein and substrate for the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase, PKR. Biochemistry. 1999;38(19):6361–6368. doi: 10.1021/bi982410u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Patel RC, Vestal DJ, Xu Z, et al. DRBP76, a double-stranded RNA-binding nuclear protein, is phosphorylated by the interferon-induced protein kinase, PKR. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(29):20432–20437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Saunders LR, Perkins DJ, Balachandran S, et al. Characterization of two evolutionarily conserved, alternatively spliced nuclear phosphoproteins, NFAR-1 and -2, that function in mRNA processing and interact with the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(34):32300–32312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Pires-daSilva A, Nayernia K, Engel W, et al. Mice deficient for spermatid perinuclear RNA-binding protein show neurologic, spermatogenic, and sperm morphological abnormalities. Developmental Biology. 2001;233(2):319–328. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Wu H, MacLeod AR, Lima WF, Crooke ST. Identification and partial purification of human double strand RNase activity. A novel terminating mechanism for oligoribonucleotide antisense drugs. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(5):2532–2542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Wassarman DA, Steitz JA. Alive with DEAD proteins. Nature. 1991;349(6309):463–464. doi: 10.1038/349463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Staley JP, Guthrie C. Mechanical devices of the spliceosome: motors, clocks, springs, and things. Cell. 1998;92(3):315–326. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80925-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Zhang S, Herrmann C, Grosse F. Pre-mRNA and mRNA binding of human nuclear DNA helicase II (RNA helicase A) Journal of Cell Science. 1999;112:1055–1064. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.7.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Aratani S, Fujii R, Oishi T, et al. Dual roles of RNA helicase a in CREB-dependent transcription. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2001;21(14):4460–4469. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4460-4469.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bairoch A, et al. The InterPro database, an integrated documentation resource for protein families, domains and functional sites. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29(1):37–40. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Sun CT, Lo WY, Wang IH, et al. Transcription repression of human hepatitis B virus genes by negative regulatory element-binding protein/SON. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(26):24059–24067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101330200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Chen J, Vijayakumar S, Li X, Al-Awqati Q. Kanadaptin is a protein that interacts with the kidney but not the erythroid form of band 3. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(2):1038–1043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Hübner S, Jans DA, Xiao CY, John AP, Drenckhahn D. Signal- and importin-dependent nuclear targeting of the kidney anion exchanger 1-binding protein kanadaptin. Biochemical Journal. 2002;361(2):287–296. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3610287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Patel CV, Handy I, Goldsmith T, Patel RC. PACT, a stress-modulated cellular activator of interferon-induced double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase, PKR. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(48):37993–37998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Micklem DR, Adams J, Grünert S, St Johnston D. Distinct roles of two conserved Staufen domains in oskar mRNA localization and translation. The EMBO Journal. 2000;19(6):1366–1377. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Li TH, Schmid CW. Differential stress induction of individual Alu loci: implications for transcription and retrotransposition. Gene. 2001;276(1-2):135–141. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00637-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Rudin CM, Thompson CB. Transcriptional activation of short interspersed elements by DNA-damaging agents. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2001;30:64–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Hagan CR, Sheffield RF, Rudin CM. Human Alu element retrotransposition induced by genotoxic stress. Nature Genetics. 2003;35(3):219–220. doi: 10.1038/ng1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Pandey R, Mandal AK, Jha V, Mukerji M. Heat shock factor binding in Alu repeats expands its involvement in stress through an antisense mechanism. Genome Biology. 2011;12, article R117 doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-11-r117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Hébert SS, Papadopoulou AS, Smith P, et al. Genetic ablation of dicer in adult forebrain neurons results in abnormal tau hyperphosphorylation and neurodegeneration. Human Molecular Genetics. 2010;19(20):3959–3969. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Hebert SS, Sergeant N, Buee L. MicroRNAs and the regulation of Tau metabolism. International Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2012;2012:6 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/406561.406561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Halle A, Hornung V, Petzold GC, et al. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-β . Nature Immunology. 2008;9(8):857–865. doi: 10.1038/ni.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Lee ST, Chu K, Im WS, et al. Altered microRNA regulation in Huntington’s disease models. Experimental Neurology. 2011;227(1):172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Bhadra U, Santosh S, Arora N, Sarma P, Pal-Bhadra M. Interaction map and selection of microRNA targets in Parkinson’s disease-related genes. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2009;2009:11 pages. doi: 10.1155/2009/363145.363145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]