Abstract

Objective

To review, categorize, and synthesize findings from the literature about the application of health information technologies in geriatrics and gerontology (GGHIT).

Materials and Methods

This mixed-method systematic review is based on a comprehensive search of Medline, Embase, PsychInfo and ABI/Inform Global. Study selection and coding were performed independently by two researchers and were followed by a narrative synthesis. To move beyond a simple description of the technologies, we employed and adapted the diffusion of innovation theory (DOI).

Results

112 papers were included. Analysis revealed five main types of GGHIT: (1) telecare technologies (representing half of the studies); (2) electronic health records; (3) decision support systems; (4) web-based packages for patients and/or family caregivers; and (5) assistive information technologies. On aggregate, the most consistent finding proves to be the positive outcomes of GGHIT in terms of clinical processes. Although less frequently studied, positive impacts were found on patients’ health, productivity, efficiency and costs, clinicians’ satisfaction, patients’ satisfaction and patients’ empowerment.

Discussion

Further efforts should focus on improving the characteristics of such technologies in terms of compatibility and simplicity. Implementation strategies also should be improved as trialability and observability are insufficient.

Conclusions

Our results will help organizations in making decisions regarding the choice, planning and diffusion of GGHIT implemented for the care of older adults.

Keywords: Health information technology, chronic disease, diffusion of innovation, geriatrics, gerontology

Background and significance

Health information technology (HIT) has the potential to improve the access, quality, safety and efficiency of patient care.1 2 The use of HIT may be particularly helpful in the care of older patients.3 Older patients often have multiple acute and chronic problems that require ongoing management by a variety of medical professionals in a variety of settings.4 Advanced age, the need for assistance with activities of daily living, and multiple active chronic illnesses place the older adult at greatest risk of poor-quality care and suboptimal transition between care settings.5 6 The large size and accelerating growth of the community-dwelling dependent population, together with growing expectations for patient-centered services, are creating a need for the development and use of new information technologies.4 7 8

A review of integrated/transitional care and hospital-at-home models reveals that many models of care for older adults have a HIT component.9 10 Studies have shown that HIT has certain well-known benefits such as improved quality and efficiency of care.1 However, there are also studies suggesting adverse results.11 12 Furthermore, the diffusion of HIT is occurring very slowly, adoption rates are low and there have been implementation failures.13 14

Many different approaches to developing and implementing health information technologies in geriatrics and gerontology (GGHIT) have been documented in the literature, but to our knowledge, there has been no attempt to synthesize the information in these published studies. Such a synthesis may provide guidance on strategies for the successful implementation of GGHIT. In this paper we present a mixed systematic review of GGHIT. The specific objectives of this review are: (1) to provide a typology of the different applications of GGHIT; (2) to determine both the positive and negative outcomes of various applications of GGHIT; and (3) to identify the factors that contribute to or hinder the successful implementation of specific GGHIT.

Methods

Design

A mixed method systematic review,15 in which evidence extracted from different sources is integrated to identify patterns and directions in the findings, was undertaken because it is particularly appropriate for understanding complex phenomena such as the adoption of innovations.16 17 This method, recognized by the Cochrane Collaboration for systematic reviews of intervention,18 can determine the effectiveness — or lack thereof — of different interventions and the conditions for their success or failure.17 18 The mixed review is presented according to PRISMA criteria:19 (1) eligibility criteria; (2) information source and search strategy; (3) study selection; (4) data collection process and synthesis of results; and (5) critical appraisal.

Eligibility criteria

The studies that met the inclusion criteria were those that reported on the assessment of GGHIT, and reported factors influencing the implementation of GGHIT. In the review, we considered all types of GGHIT, including HIT with low technical characteristics such as telephones. Articles were excluded if they were focused solely on describing the design or development of GGHIT or dealt with educational technologies.

Information sources and search strategy

The review is based on a systematic, comprehensive search of four databases: Medline, Embase, PsychInfo and ABI/Inform Global. Articles in English or French, published or in press between January 2000 and April 2010, were considered. The literature search was performed by a librarian and validated by a researcher. The following two sets of keywords and terms were searched in combination:

Information technology (Information Technology; Medical Informatics; Computers; Medical Records Systems; Medical Informatics; Hospital Information Systems; Internet; Local Area Networks; Telemedicine; Educational Technology; Information Systems; Automated Information Processing; Computer Applications; Computer Mediated Communication; Electronic Communication)

Geriatrics/Gerontology (Geriatrics; Geriatric Dentistry; Geriatric Nursing; Geriatric Psychiatry; Geriatric Assessment; Geriatric Patients; Older patients; Gerontology)

We hand-searched the reference lists of all the selected references. EndNote software was used to manage the references and eliminate duplications.

Study selection

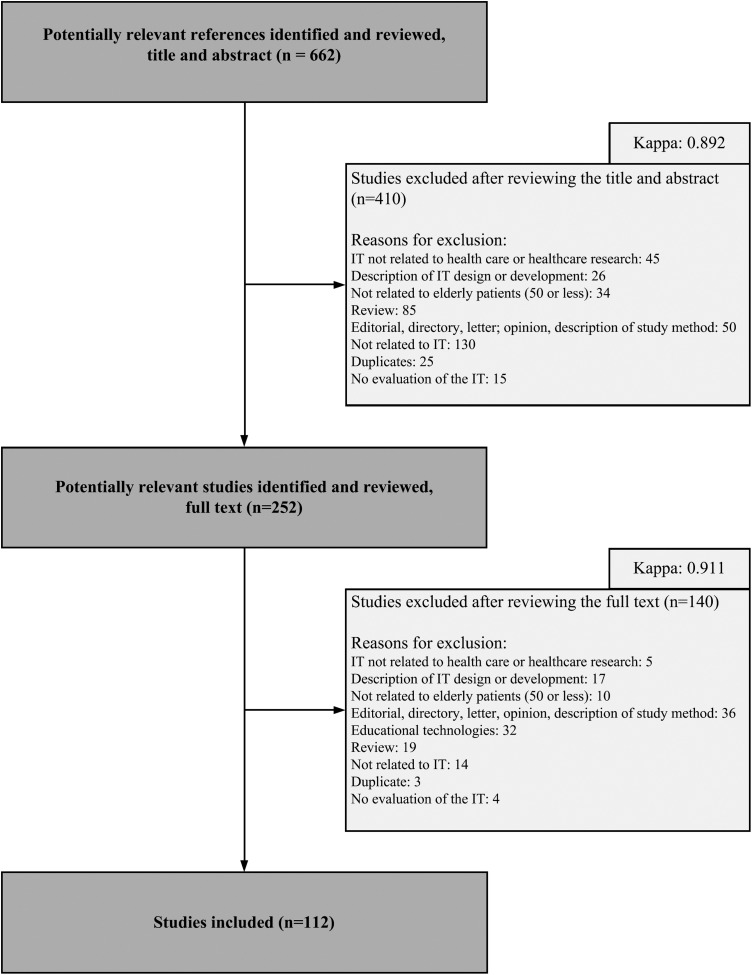

Study selection was performed independently by two researchers. First, references were selected based on title and abstract according to the review study's inclusion and exclusion criteria. When there was any doubt, the study was provisionally included for consideration on the basis of a reading of the full text. The second round of selection was based on the full text of the papers. Any disagreement was resolved through consensus by two other researchers. Kappa scores were calculated at each stage (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart.

Data collection and synthesis

Data extraction from the selected studies was performed independently by two researchers using a standardized form. To synthesize data, we first conducted a narrative synthesis of the heterogeneity of study characteristics.20 We used the validated methodological guide for narrative syntheses,20 which allowed us to first develop a typology of GGHIT by creating homogeneous subgroups.20 Our analysis goes beyond the denomination of these GGHIT used by the studies’ authors. First, it encompasses the technologies’ critical characteristics: functionalities, potential users (stakeholder clinicians or patients), and rationales in terms of the processes that the GGHIT are intended to support/improve. Second, we analyzed our results using the diffusion of innovation theory (DOI).21 This theory states that the DOI process is influenced by five characteristics of the innovation:21 relative advantage (the degree to which an innovation is perceived as better than the idea it supersedes), compatibility (the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being consistent with the existing values, past experiences and needs of potential adopters), simplicity (the degree to which an innovation is perceived as not difficult to understand and use), trialability (the degree to which an innovation may be experimented with on a limited basis) and observability (the degree to which the results of an innovation are understandable to individuals or known by the community). In order to move beyond a simple description of the technologies, we refined the DOI framework and created three categories that allowed us to differentiate between the technology per se, its implementation and its specific outcomes. In the data collection and synthesis phase, any disagreement was resolved through consensus.

Critical appraisal

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed independently by two researchers. As the methods of the included studies were disparate—qualitative, quantitative, or mixed—we used all nine criteria of a quality assessment tool developed for systematic reviews of disparate data.22 Once again, any discrepancies were resolved through consensus. No study was excluded on the basis of its quality, as our primary objective was to gain knowledge on the nature of GGHIT. However, we conducted a sensitivity analysis18 in order to assess whether the decision to include each study independent of its quality had a major effect on the results of the review.

Results

The primary search yielded 658 references (figure 1). Another four references were found by searching the reference lists of the retrieved articles (N=662). Applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 410 references were excluded on the basis of the title and abstract (κ 0.89) and 140 were excluded on the basis of the full text (κ 0.91). The final sample consisted of 112 articles.

Characteristics of the selected studies

Fifty-seven per cent of the studies were conducted in North America—USA (53%) and Canada (4%)—and one in South America (1%) (see supplementary appendix 1, available online only). The remaining studies were conducted in Europe (20%), Asia (13%) and Oceania (8%). Two studies were conducted in multiple countries (2%). Most of the study designs were quantitative (61%). Of these, only 13% were based on a randomized controlled trial. Other quantitative designs were quasi-experimental design (27%), observational study (14%) or survey (6%). The rest of the studies employed qualitative (32%) or mixed method designs (7%).

The settings were mainly patients’ homes (38%), long-term care facilities (22%), hospitals (21%), medical centers (5%), universities (1%) and multiple sites (10%). The subjects were only patients (68%), both patients and professionals (14%), or multiple healthcare professionals (10%).

Typology of GGHIT

The analysis of the literature revealed five types of GGHIT (described in table 1). While telecare technologies are the focus of exactly 50% of the selected articles,23–77 other GGHIT were less frequently studied: electronic health records (EHR) (12.5% of the selected articles),78–91 decision support systems (DSS) (13.4%),92–106 web-based packages for patients/family caregivers (11.6%),107–119 and assistive information technologies (12.5%).120–133

Table 1.

Typology of HIT used in gerontology and geriatrics

| Type of HIT N=112 |

Core functionalities | Rationale–goals–potential interest | Other denominations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telecare 56 articles (50%) |

Enables remote diagnoses, monitors patient health status, provides case management or rehabilitation | ▸ Shift in care from hospitals to ambulatory settings ▸ Response to the shortage of professionals ▸ Decreased impact of remoteness ▸ Availability of medical and specialized expertise ▸ Improved working conditions ▸ Avoidance of clinician travel time ▸ Optimal use of nurses’ time |

Teleconsultation, telemonitoring, remote case management, telerehabilitation |

| EHR 14 articles (12.5%) |

Provides a structured repository of patient medical information generated by one or more encounters—without a decision-support system | ▸ Access to patient information ▸ Collaboration and coordination among team members ▸ Access to patient information from multiple locations ▸ Database of structured and complete information ▸ Patient self-management |

EHR, electronic nursing record, computerized patient care record, electronic medical record, personal health records, electronic geriatric assessment tools, e-prescribing, computer generated reports/summaries, chronic disease registries without DSS |

| DSS 15 articles (13.4%) |

Guides healthcare professionals in their decision making | ▸ Better quality and safety of care (eg, avoiding adverse drug events) ▸ Avoidance of failures to apply evidence-based medicine ▸ Standardized care |

Electronic reminders/alerts, computerized order entry with DSS, computerized monitoring of drug levels, electronic guidelines, electronic care plan development, chronic disease registries with DSS (reminders, computerized clinical guidelines, ordering guidance, etc) |

| Web-based packages and social media for patients/family caregivers 13 articles (11.6%) |

Provides health information/support for patients/family caregivers by telephone, telecomputing, web-based information | ▸ Access to scientific information ▸ Patient self-management ▸ Increased coping strategies ▸ May break isolation ▸ Alleviate family burden and anxiety |

Web-based health information, health web sites, e-health web portals, caregiver support online |

| Assistive information technology 14 articles (12.5%) |

Helps an individual to perform a task safely | ▸ Independent living for elderly people ▸ Access to assistance for patients in the context of insufficiently available human/financial resources ▸ Improved safety ▸ Improved quality of life, well-being for patients |

Smart home, gerontechnology, domotics, robotic technology (service/assistant robots, robotic pets), automated pill dispensers, PDA |

DSS, decision support systems; EHR, electronic health records; HIT, health information technology; PDA, personal digital assistant.

Methodological quality of the studies

The critical appraisal of the studies selected in our review reveals that the robustness of the research methods used in gerontology and geriatrics for studying health informatics varies across studies (table 2). Indeed, weaknesses were observed in the descriptions of methods, particularly a lack of detailed information on the sampling methods used (assessed as fair, poor or not reported in 67% of the studies) and on the data analysis (assessed as fair, poor or not reported in 60% of the studies). Furthermore, the studies rarely report on ethical aspects and risks of bias. The research findings and results and the implications and usefulness of the studies were rated as good or fair in 94% and 88% of the studies, respectively.

Table 2.

Critical appraisal of the studies N (%)

| Good | Fair | Poor | Very poor | NA | NR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abstract | 84 (75) | 28 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Introduction and aims | 64 (57) | 48 (43) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Method and data | 56 (50) | 45 (40) | 9 (8) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Sampling | 35 (31) | 41 (37) | 24 (21) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 10 (9) |

| Data analysis | 45 (40) | 48 (43) | 11 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (7) |

| Ethics and bias | 34 (30) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 75 (67) |

| Findings/results | 44 (39) | 61 (55) | 7 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Transferability/generalizability | 32 (29) | 65 (58) | 15 (13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Implications and usefulness | 33 (30) | 65 (58) | 14 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

NA, not applicable; NR, not reported.

We also performed the critical appraisal for each type of GGHIT (see supplementary appendix 2, available online only). The results show that the quality of the studies is similar from one type of GGHIT to another, except that method/data and sampling were rated as ‘good’ in studies involving DSS slightly more often than studies involving other types of GGHIT.

In addition, a sensitivity analysis19 was conducted to determine whether the decision to include all the studies, independent of their overall quality, had any effect on the results of the review. Even when we excluded the articles with at least one bad quality indicator (eg, rated as very poor or not reported with regard to methods and data, sampling, data analysis), the findings of this review remained consistent.

Outcomes, technology and implementation of GGHIT

Global results

As the study results in table 3 show, on aggregate, GGHIT translate into positive outcomes. Impact on clinical processes was the outcome most frequently studied and almost all of the 65 studies that looked at it had positive results (94%). Only 25 studies examined impacts on patients’ health outcomes, of those 96% reported a positive outcome. Similarly, 27 out of 33 studies (82%) that looked at patients’ satisfaction had positive results. Although examined even less frequently, impacts were mainly positive in terms of productivity, efficiency and costs (14/16 studies; 88%), clinicians’ satisfaction (11/13; 85%), and patients’ empowerment (12/15; 80%).

Table 3.

Summary of the results (N=112 studies; N (%))

| Dimensions | Not reported | N* | + | − | +/− | Ø |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Clinical processes | 47 | 65 (100) | 61 (94) | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Patients’ health outcomes | 87 | 25 (100) | 24 (96) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Productivity, efficiency, costs | 96 | 16 (100) | 14 (88) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Clinicians’ satisfaction | 99 | 13 (100) | 11 (85) | 2 (15) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Patients’ satisfaction | 79 | 33 (100) | 27 (82) | 5 (15) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Patients’ empowerment | 97 | 15 (100) | 12 (80) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 2 (13) |

| Technology | ||||||

| Compatibility | 70 | 42 (100) | 26 (62) | 14 (33) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Simplicity | 72 | 40 (100) | 22 (55) | 10 (25) | 8 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Implementation | ||||||

| Trialability | 90 | 22 (100) | 17 (77) | 3 (14) | 2 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Observability | 107 | 5 (100) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

N*, Number of studies for which the dimension was evaluated; +, positive evaluation; −, negative evaluation; +/−, evaluation that was both positive and negative; Ø, no influence.

Despite these positive impacts, there is still room for improvement regarding the characteristics of technology: GGHIT are not always compatible with the values, professional practices, and needs of patients and clinicians (positive compatibility in 62% of the 42 studies), and only 55% of the studies (22/40) found that GGHIT are considered simple to use.

Furthermore, in terms of implementation, the results demonstrate that while 17 out of 22 studies that looked at this issue found positive results (77%), trialability (often reflected as technical support, training and adaptation) is still insufficient. It is also the case for observability (positive for 3/5 studies—60%), which has rarely been studied. The following subsections provide a closer examination of these results for each of the five types of GGHIT identified earlier. Tables 4–8 provide finer-grained information for each dimension.

Table 4.

| N* | + | − | +/− | Ø | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Clinical processes23 30 32–45 47 50 52 56 57 60–62 64–66 71–74 77 | 32 (100) | 31 (97) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Increased quality of care, continuity, timely access; improved uptake of preventive care, assessment and monitoring; decreased errors − Failure to take into account complex cases |

| Patients’ health outcomes,25–29 41 42 55 56 59 63 66 68 73 107 | 15 (100) | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Improved blood test results, functional/cognitive autonomy, quality of life; decreased mortality |

| Productivity, efficiency, costs30 33 36 37 45 52 56 62 63 69 71 76 | 12 (100) | 11 (92) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | + Decreased emergency department visits and hospitalization; cost savings; decreased physician time; increased number of patients cared for |

| Clinicians’ satisfaction39 46 52 55 63 71 76 | 7 (100) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + The clinicians are highly satisfied; viewed favorably and highly acceptable |

| Patients’ satisfaction24 28 31 33 35 36 39 41 46–49 51–55 60 66 70 76 | 21 (100) | 16 (76) | 5 (24) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Increased sense of personal safety and security; increased user satisfaction; patients preferred a remote interview close to their homes to an in-person interview at a distance; patients perceived the system as a valuable resource that offered great potential − Obtrusiveness; lack of user friendliness; inaccurate measurement; threat as a replacement for visits; interference with daily activities; privacy concerns |

| Patients’ empowerment26 28 41 67 77 107 | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Self-confidence; self-efficacy |

| Technology | ||||||

| Compatibility24 35 38 41 42 46–48 51 54 55 60 66 68 70 71 73–77 | 21 (100) | 16 (76) | 4 (19) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | + Compatible with the existing relationships between patients and clinicians; adapt well to the context; feasible; acceptable − Poor fit with the patient's preference for face-to-face contact; not well suited to physically impaired persons; privacy issues |

| Simplicity24 30 31 33 35 40 42 46–48 50 53 55 60 66 67 71 75 77 | 19 (100) | 9 (47) | 7 (37) | 3 (16) | 0 (0) | + Easy to use − Technical difficulties and lack of user-friendliness; information overload |

| Implementation | ||||||

| Trialability46 47 53 60 73 76 77 | 7 (100) | 7 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + The more that participants use it, the more comfortable they feel with it |

| Observability35 70 | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Observability is evaluated as positive − Nurses’ negative perception of the technology's aesthetics |

N*, Number of studies for which the dimension was evaluated; +, positive evaluation; −, negative evaluation; +/−, evaluation that was both positive and negative; Ø, no influence.

Table 5.

Synthesis of the results for EHR (14 studies;78–91 N(%))

| N* | + | − | +/− | Ø | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Clinical processes79 81–91 | 12 (100) | 11 (92) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Improved communication; increased accuracy of records; better detection and assessment; improved quality of care; decreased medication use − Low timeliness of data reporting; lack of sensitivity to health status change |

| Patients’ health outcomes80 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Quality of life |

| Productivity, efficiency, costs80 88 | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Efficiency of resources use; cost saving |

| Clinicians’ satisfaction78 79 84 88 | 4 (100) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Employee satisfaction; satisfaction regarding informational functionality of software − Fax was the most preferred method for communication of discharge summaries; limited ability to comply with suggestions |

| Technology | ||||||

| Compatibility84 88 90 91 | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | − Poor ergonomics; loss of human contact; privacy issues |

| Simplicity78 79 81 82 85 88 | 6 (100) | 3 (50) | 1 (17) | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | + Easy to use − Difficulties may arise when using EHR; not user friendly; and technical problems; confusing |

| Implementation | ||||||

| Trialability78 79 85 87 88 91 | 6 (100) | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Suitable technical support − Insufficient or inadequate training; insufficient support |

| Observability78 88 91 | 3 (100) | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Good observability − Lack of awareness about EHR |

N*, Number of studies for which the dimension was evaluated; +, positive evaluation; −, negative evaluation; +/−, evaluation that was both positive and negative; Ø, no influence.

EHR, electronic health records.

Table 6.

Synthesis of the results for DSS (15 studies;92–106 N(%))

| N* | + | − | +/− | Ø | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Clinical processes92–95 98 99 101–106 | 12 (100) | 11 (92) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Improved quality of care; decreased errors and adverse drug events; improved assessment and detection; improved communication − Information content of the reminders |

| Patients’ health outcomes100 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Decreased mortality |

| Productivity, efficiency, costs92 100 | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Decreased hospital use; cost savings − Increased time spent by physicians |

| Clinicians’ satisfaction92 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Satisfaction score with regard to clinical value |

| Patients’ satisfaction95–97 | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Easy to understand and use; enjoyable to use |

| Technology | ||||||

| Compatibility92 95 96 98 104 | 5 (100) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Fits with current workflow − Decreased clinical autonomy; time needed to read the reminders |

| Simplicity92 95 96 98 101 | 5 (100) | 3 (60) | 1 (20) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | + Easy to use − Difficult to use; too many reminders; information content is complex |

| Implementation | ||||||

| Trialability98 101 | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Special modifications can be made to the software in response to the uniqueness of the setting |

N*, Number of studies for which the dimension was evaluated; +, positive evaluation; −, negative evaluation; +/−, evaluation that was both positive and negative; Ø, no influence.

DSS, decision support systems.

Table 7.

Synthesis of the results for web-based packages (13 studies;108–120 N(%))

| N* | + | − | +/− | Ø | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Clinical processes113 114 116 | 3 (100) | 2 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | + Improved relationship with careers, families |

| Patients’ health outcomes109 111 120 | 3 (100) | 2 (67) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Decrease mental health problems − Increase physical and mental health problems |

| Patients’ satisfaction112 113 120 | 3 (100) | 2 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | + High interest in on-line health information |

| Patients’ empowerment108 110–112 114 115 117–119 | 9 (100) | 6 (67) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | + Confidence; self-efficacy; self-control − Knowledge of how to search for information |

| Technology | ||||||

| Compatibility108 112 115 119 | 4 (100) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Compatibility is assessed positively − Not compatible with patients’ disabilities |

| Simplicity115 119 120 | 3 (100) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | + Easy to use − Problems finding information; absence of a user's guide; language barriers |

| Implementation | ||||||

| Trialability108 111 115 119 | 4 (100) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | 0 (0) | + Focus on new learner needs; access to an instructor; peer training assistants; support by a technical worker − Insufficient time for exploration |

N*, Number of studies for which the dimension was evaluated; +, positive evaluation; −, negative evaluation; +/−, evaluation that was both positive and negative; Ø, no influence.

Table 8.

Synthesis of the results for assistive information technologies (14 studies;121–134 N(%))

| N* | + | − | +/− | Ø | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Clinical processes121 122 124 125 127 130 | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Improved assistance, detection of falls, monitoring of health parameters; increased communication; improved dietary intake |

| Patients’ health outcomes122 129 131 133 134 | 5 (100) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Decreased agitation, depression; increased communication; decreased pain |

| Clinicians’ satisfaction128 | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Useful to manage patients’ health conditions |

| Patients’ satisfaction121 126 127 129 131 132 | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Patients enjoyed using PDA; non-obtrusiveness of technology; positive attitude towards system |

| Technology | ||||||

| Compatibility122–127 129 130 | 8 (100) | 5 (63) | 3 (38) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Acceptable; appropriate − Privacy issues; bulky nature of the devices |

| Simplicity121–124 127–129 | 7 (100) | 6 (86) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | + Easy to use − Problems using the devices |

| Implementation | ||||||

| Trialability123 127 128 | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | + Training and adaptability of assistive technologies; the more that participants use the technology, the more comfortable they feel with it |

PDA, personal digital assistant.

Telecare technologies

A vast majority of studies evaluated the outcomes of telecare technologies (table 4) as positive in terms of clinical processes (31/32; 97%), patients’ health outcomes (15/15; 100%), productivity, efficiency and costs (11/12; 92%), clinicians’ satisfaction (7/7; 100%), patients’ satisfaction (16/21; 76%) and patients’ empowerment (6/6; 100%).23–77 107 In terms of the technology, compatibility was positive in 76% of the studies (16/21). However, telecare technologies were perceived as easy to use in less than half of the studies (9/19; 47%). Regarding implementation, all the seven studies that evaluated trialability had positive results. Results for observability were mixed (1/2 was positive).

Electronic health records

In terms of outcomes, the synthesis of the selected studies (table 5) shows that EHR use led to positive impacts on clinical processes (11/12; 92%).78–91 Other outcomes were studied less frequently but results were positive overall except for clinicians’ satisfaction. Concerning the technology, EHR were found not to be compatible with current values, professional practices and needs of patients and clinicians in a majority of the studies (3/4; 75%). EHR were considered simple to use in only half of the studies (3/6; 50%). With regard to implementation, half of the studies gave a negative evaluation of trialability (3/6; 50%). Two out of three studies found observability to be positive (67%).

Decision support systems

The majority of the studies (table 6) found that DSS led to positive outcomes regarding impacts on clinical processes (92% of the 12 studies for which this dimension was evaluated).92–106 Other outcomes were studied less frequently but were generally positive except for productivity (1/2; 50%). Regarding the technology, most of the studies reported compatibility (3/5; 60%) and simplicity (3/5; 60%) for DSS. With regard to implementation, both studies that considered trialability were positive (100%). None of the studies evaluated the observability of DSS.

Web-based packages for patients or family caregivers

The synthesis of the selected studies (table 7) shows that web packages for patients and/or family caregivers led to positive outcomes particularly with regard to patients’ empowerment (6/9; 67%), which was most frequently studied.108–120 The other outcomes were studied less frequently but were generally positive. In terms of the technology, compatibility received a positive evaluation in half of the four studies that looked into this issue (50%). The web packages were evaluated as easy to use in only one out of three studies (33%). In terms of implementation, trialability was found to be positive in two out of four studies (50%). None of the studies evaluated the observability of web packages.

Assistive information technologies

A few studies for which outcomes were evaluated show that assistive information technologies (table 8) led to positive impacts on clinical processes (6/6; 100%), patients’ health outcomes (5/5; 100%), clinicians’ satisfaction (1/1; 100%) and patients’ satisfaction (6/6; 100%).121–133 In terms of the technology, the compatibility of assistive technologies received positive evaluation in most of the cases (5/8; 63%). Almost all the seven studies confirm that assistive devices are easy to use (6/7; 86%). In terms of implementation, three studies positively evaluated trialability (100%). None of the studies evaluated the observability of assistive information technologies.

Discussion

Our study identifies five major types of GGHIT, highlights their respective impacts as described in the literature, and offers a conceptual framework to understand better how these technologies are currently used and diffused. We believe that our use and adaptation of a sound theoretical foundation, the DOI theory increases the relevance and generalizability of our results in addition to facilitating the accumulation of knowledge over time.135 We adapted DOI to frame our results into three categories. First, we identified the main outcomes of GGHIT in terms of their relative advantage. We further identified a subset of specific outcomes: impacts on clinical processes, patients’ health outcomes, productivity, efficiency and costs, clinicians’ satisfaction, patients’ satisfaction and empowerment, which is responsive to researchers who ‘have criticized the rather general nature of relative advantage as being an aggregate of benefits, claiming that this makes the construct too vague to measure effectively’.136 Second, we highlighted the principal characteristics of these GGHIT in terms of their compatibility with existing values and practices and their simplicity. Third, we identified the role of trialability and observability in facilitating the implementation process.137

Our systematic review reveals on the one hand that, when looking at relative advantage, the use of GGHIT translates into positive outcomes mostly with regard to clinical processes. For instance, EHR have been shown to improve the quality of care83 with fewer total medications per patient,79 improved patient histories and physical examination assessments,81 and better documentation of patient health status.91 92 Despite the fact that the following outcomes have not been extensively looked at, our study also reveals a positive, yet relatively less consistent, impact of GGHIT on patients’ health outcomes, productivity, efficiency and costs, clinicians’ satisfaction, patients’ satisfaction and empowerment. For example, telecare technologies have been shown to improve health outcomes (health status or functional health)27 28 41 63 66 and help in disease control,59 and DSS have been found to increase clinicians’ awareness of patient safety risks.101 Overall, our systematic review indicates that GGHIT may play a critical role in ensuring appropriate care for older patients.

On the other hand, our research results confirm that there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution. Healthcare clinicians and managers need to select carefully the type of GGHIT that will be the most appropriate based on the needs of their organizations and clienteles.138 The acquisition of dependable hardware and software appears an absolute necessity. Equally important, the choice of technology should also take into account its compatibility with the overall organizational system.2 35 139 Indeed, extant research shows that compatibility is often negatively evaluated by HIT users,90 92 93 in particular due to a loss of human contact and privacy issues90 or because of a perception of decreased clinical autonomy.94 100 In addition, among the most important challenges faced in age-related care is the issue of simplicity, which includes the development of systems that are truly user friendly and user oriented.140 If GGHIT are difficult to use, for example, when there are too many reminders or when the information content is complex,94 it may become a barrier to adoption and use.

Our results also indicate that to maximize the implementation success of GGHIT, it is essential to identify the best methods of integrating the use of HIT into clinicians’ routine workflow. Our study highlights the role of observability and trialability in the implementation dynamic. In this perspective, repetitive testing seems to improve initial system use.141 The education and training of users are also crucial.140 More specifically, results suggest that it is important to ensure timely user support, to document system problems and provide prompt feedback.142

Our review has some limitations. As explained in the critical appraisal section, the quality of the studies included varies considerably. Nevertheless, a sensitivity analysis did not reveal that inclusion of poor quality studies was skewing the results. Our review may also suffer from publication bias as studies reporting positive outcomes are more frequently published than studies with negative outcomes.18

Conclusion

The typology we propose in this paper can contribute to more informed system selection decisions by healthcare managers and caregivers. The findings of this study can be used by organizations to guide the specific implementation strategies that provide the best chances of success for each type of GGHIT. As it identifies the nature of different GGHIT, as well as many of the benefits and challenges associated with their use, it could be used by organizations to tailor their policies regarding the choice, planning, diffusion, and monitoring of HIT implemented for the care of older adults. Finally, given that the majority of the studies conducted to date deal with telecare technologies, an avenue for future research would be to focus on other types of GGHIT such as EHR, DSS, web packages, etc.

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published Online First. The second author has added an additional affiliation.

Acknowledgements: Muriel Gueriton, librarian, provided support with the literature search. The authors are most grateful to the editors and the reviewers for the guidance provided on their work.

Contributors: IVe: concept and design, data acquisition and analysis, drafting of the manuscript, revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final version. SA: data acquisition and analysis, revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final version. IVa: data acquisition and analysis, revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final version. HB: concept and design, revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final version. LL: concept and design, data acquisition and analysis, drafting of the manuscript, revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final version. IVe and LL are responsible for the overall content as guarantors. The guarantor accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: This study received financial support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR - KRS 250478) and the McGill University Dr Joseph Kaufmann Chair in Geriatric Medicine. The sponsors played no role in the study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lau F, Lau F, Kuziemsky C, et al. A review on systematic reviews of health information system studies. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2010;17:637–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaspers M, Smeulers M, Vermeulen H, et al. Effects of clinical decision-support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a synthesis of high-quality systematic review findings. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:327–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiner M, Callahan C, Tierney W, et al. Using information technology to improve the health care of older adults. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:430–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman E. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:549–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman E, Boult C. Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:556–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norris S, High K, Gill T, et al. Health care for older Americans with multiple chronic conditions: a research agenda. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:149–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane R. Clinical challenges in the care of frail older persons. Aging Clin Exp Res 2002;14:300–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nebeker J, Hurdle J, Bair B. Future history: medical informatics in geriatrics. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003;58:M820–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golden A, Tewary S, Dang S, et al. Care management's challenges and opportunities to reduce the rapid rehospitalization of frail community-dwelling older adults. Gerontologist 2010;50:451–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leff B, Montalto M. Hospital at home: potential in geriatric healthcare and future challenges to dissemination. Aging Health 2006;5:701–3 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koppel R, Metlay J, Cohen A, et al. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA 2005;293:1197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ash J, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004;11:104–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lapointe L, Rivard S. Getting physicians to accept new information technology: insights from case studies. CMAJ 2006;174:1573–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hendy J, Reeves B, Fulop N, et al. Challenges to implementing the national programme for information technology (NPfIT): a qualitative study. BMJ 2005;331:331–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(Suppl. 1):6–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pope C, Mays N, Popay J. Synthesizing qualitative and quantitative health evidence: a guide to methods. Maidenhead, England: Open University Press, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popay J. Moving beyond effectiveness in evidence synthesis: Methodological issues in the synthesis of diverse sources of evidence. NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence) 2006. http://www.nice.org.uk/niceMedia/docs/Moving_beyond_effectiveness_in_evidence_synthesis2.pdf (accessed 22 Feb 2012).

- 18.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane book series. Chichester, England: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodgers M, Sowden A, Petticrew M, et al. Testing methodological guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: effectiveness of interventions to promote smoke alarm ownership and function. Evaluation 2009;15:49–73 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers E. Diffusion of innovation. 5th edn. New York, NY: Free Press, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, et al. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 2002;12:1284–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harari D, Iliffe S, Kharicha K, et al. Promotion of health in older people: a randomised controlled trial of health risk appraisal in British general practice. Age Ageing 2008;37:565–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai A, Kaufman D, Starren J, et al. Evaluation of a remote training approach for teaching seniors to use a telehealth system. Int J Med Inform 2009;78:732–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ackerman SE, Bednarczyk KR, Roncolato K, et al. The use of computer technology with older adult clients: a pilot study of occupational therapists. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr 2001;20:49–57 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguilar J, Cantos J, Exposito G, et al. Tele-assistance services to improve the quality of life for elderly patients and their relatives: the tele-care approach. J Inf Technol Healthc 2004;2:109–17 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alkema G, Wilber K, Shannon G, et al. Reduced mortality: the unexpected impact of a telephone-based care management intervention for older adults in managed care. Health Serv Res 2007;42:1632–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnaert A, Delesie L. Effectiveness of video-telephone nursing care for the homebound elderly. Can J Nurs Res 2007;39:20–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bendixen R, Horn K, Levy C. Using telerehabilitation to support elders with chronic illness in their homes. Top Geriatr Rehabil 2007;23:47–51 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan W, Woo J, Hui E, et al. The role of telenursing in the provision of geriatric outreach services to residential homes in Hong Kong. J Telemed Telecare 2001;7:38–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Courtney K, Demiris G, Hensel B. Obtrusiveness of information-based assistive technologies as perceived by older adults in residential care facilities: a secondary analysis. Med Inform Internet Med 2007;32:241–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Debray M, Couturier P, Greuillet F, et al. A preliminary study of the feasibility of wound telecare for the elderly. J Telemed Telecare 2001;7:353–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duke C. The frail elderly community-based case management project. Geriatr Nurs 2005;26:122–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grob P, Weintraub D, Sayles D, et al. Psychiatric assessment of a nursing home population using audiovisual telecommunication. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2001;14:63–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horton K. The use of telecare for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: implications for management. J Nurs Manag 2008;16:173–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hui E, Woo J, Hjelm M, et al. Telemedicine: a pilot study in nursing home residents. Gerontology 2001;47:82–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnston D, Jones BN., III Telepsychiatry consultations to a rural nursing facility: a 2-year experience. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2001;14:72–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones BN, III, Johnston D, Reboussin B, et al. Reliability of telepsychiatry assessments: subjective versus observational ratings. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2001;14:66–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kobb R, Hilsen P, Ryan P. Assessing technology needs for the elderly: finding the perfect match for home. Home Healthc Nurse 2003;21:666–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laflamme M, Wilcox D, Sullivan J, et al. A pilot study of usefulness of clinician–patient videoconferencing for making routine medical decisions in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1380–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lai J, Woo J, Hui E, et al. Telerehabilitation—a new model for community-based stroke rehabilitation. J Telemed Telecare 2004;10:199–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lamothe L, Fortin J, Labbé F, et al. Impacts of telehomecare on patients, providers, and organizations. Telemed J E Health 2006;12:363–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loh P, Ramesh P, Maher S, et al. Can patients with dementia be assessed at a distance? The use of Telehealth and standardised assessments. Intern Med J 2004;34:239–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loh P, Donaldson M, Flicker L, et al. Development of a telemedicine protocol for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. J Telemed Telecare 2007;13:90–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lyketsos C, Roques C, Hovanec L, et al. Telemedicine use and the reduction of psychiatric admissions from a long-term care facility. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2001;14:76–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macduff C, West B, Harvey S. Telemedicine in rural care. Part 1: developing and evaluating a nurse-led initiative. Nurs Stand 2001;15:33–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melkas H. Network collaboration within safety telephone services for ageing people in Finland. Gerontechnology 2003;2:306–23 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Menon AS, Kondapavalru P, Krishna P, et al. Evaluation of a portable low cost videophone system in the assessment of depressive symptoms and cognitive function in elderly medically ill veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis 2001;189:399–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mol M, De Groot R, Hoogenhout E, et al. An evaluation of the use of a website and telephonic information service as public education about forgetfulness. Telemed J E Health 2007;13:433–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ojel-Jaramillo JM, Canas JJ. Enhancing the usability of telecare devices. Hum Technol 2006;2:103–18 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Onor M, Trevisiol M, Urciuoli O, et al. Effectiveness of telecare in elderly populations—a comparison of three settings. Telemed J E Health 2008;14:164–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pallawala P, Lun K. EMR-based TeleGeriatric system. Int J Med Inform 2001;61:849–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palmas W, Teresi J, Morin P, et al. Recruitment and enrollment of rural and urban medically underserved elderly into a randomized trial of telemedicine case management for diabetes care. Telemed J E Health 2006;12:601–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Percival J, Hanson J. Big brother or brave new world? Telecare and its implications for older people's independence and social inclusion. Crit Soc Policy 2006;26:888–909 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poon P, Hui E, Dai D, et al. Cognitive intervention for community-dwelling older persons with memory problems: telemedicine versus face-to-face treatment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:285–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quinn C. Low-technology heart failure care in home health: improving patient outcomes. Home Healthc Nurse 2006;24:533–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sävenstedt S, Bucht G, Norberg L, et al. Nurse–doctor interaction in teleconsultations between a hospital and a geriatric nursing home. J Telemed Telecare 2002;8:11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schonfeld L, Larsen RG, Stiles PG. Behavioral health services utilization among older adults identified within a state abuse hotline database. Gerontologist 2006;46:193–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shea S, Weinstock RS, Teresi JA, et al. A randomized trial comparing telemedicine case management with usual care in older, ethnically diverse, medically underserved patients with diabetes mellitus: 5 year results of the IDEATel study. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:446–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shores MM, Ryan-Dykes P, Williams RM, et al. Identifying undiagnosed dementia in residential care veterans: comparing telemedicine to in-person clinical examination. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2004;19:101–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Banerjee S, Steenkeste F, Couturier P, et al. Telesurveillance of elderly patients by use of passive infra-red sensors in a ‘smart’ room. J Telemed Telecare 2003;9:23–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tang WK, Chiu H, Woo J, et al. Telepsychiatry in psychogeriatric service: a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:88–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tousignant M, Boissy P, Corriveau H, et al. In home telerehabilitation for older adults after discharge from an acute hospital or rehabilitation unit: a proof-of-concept study and costs estimation. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2006;1:209–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vestal L, Smith-Olinde L, Hicks G, et al. Efficacy of language assessment in Alzheimer's disease: comparing in-person examination and telemedicine. Clin Interv Aging 2006;1:467–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whitson HE, Hastings SN, McConnell ES, et al. Inter-disciplinary focus groups on telephone medicine: a quality improvement initiative. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2006;7:407–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu G, Keyes LM. Group tele-exercise for improving balance in elders. Telemed J E Health 2006;12:561–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xavier A, Sales M, Ramos L, et al. Cognition, interaction and ageing: an Internet workshops exploratory study. Stud Health Technol Inform 2004;103:289–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Belfor N, et al. Computer-based cognitive training for mild cognitive impairment: results from a pilot randomized, controlled trial. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23:205–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bendixen RM, Levy CE, Olive ES, et al. Cost effectiveness of a telerehabilitation program to support chronically ill and disabled elders in their homes. Telemed J E Health 2009;15:31–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Demiris G, Oliver DP, Giger J, et al. Older adults’ privacy considerations for vision based recognition methods of eldercare applications. Technol Health Care 2009;17:41–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mahoney DM, Mutschler PH, Tarlow B, et al. Real world implementation lessons and outcomes from the Worker Interactive Networking (WIN) project: workplace-based online caregiver support and remote monitoring of elders at home. Telemed J E Health 2008;14:224–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ogawa H, Yonezawa Y, Maki H, et al. A safety support system for patient location. Biomed Sci Instrum 2008;44:513–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rajasekaran MP, Radhakrishnan S, Subbaraj P. Elderly patient monitoring system using a wireless sensor network. Telemed J E Health 2009;15:73–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roberts C, Mort M. Reshaping what counts as care: older people, work and new technologies. ALTER—Eur J Disability Res/ Revue Européenne de Recherche sur le Handicap 2009;3:138–58 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scandurra I, Mostrom D, Hagglund M. Introducing a mobile ICT system in homecare: evaluation of a socio-technical implementation process. J Info Technol Healthc 2008;6:356–66 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith AC, Gray LC. Telemedicine across the ages. Med J Aust 2009;190:15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Trief PM, Sandberg J, Izquierdo R, et al. Diabetes management assisted by telemedicine: patient perspectives. Telemed J E Health 2008;14:647–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alexander GL, Rantz M, Flesner M, et al. Clinical information systems in nursing homes: an evaluation of initial implementation strategies. Comput Info Nurs 2007;25:189–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bollen C, Warren J, Whenan G. Introduction of electronic prescribing in an aged care facility. Aust Fam Physician 2005;34:283–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boyd C, Boult C, Shadmi E. Guided care for multimorbid older adults. Gerontologist 2007;47:697–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fung C. Computerized condition-specific templates for improving care of geriatric syndromes in a primary care setting. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:989–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lapane K, Dubé C, Schneider K, et al. Patient perceptions regarding electronic prescriptions: is the geriatric patient ready? J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1254–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shever L, Titler M, Dochterman J, et al. Patterns of nursing intervention use across 6 days of acute care hospitalization for three older patient populations. Int J Nurs Terminol Classif 2007;18:18–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen Y, Brennan N, Magrabi F. Is email an effective method for hospital discharge communication? A randomized controlled trial to examine delivery of computer-generated discharge summaries by email, fax, post and patient hand delivery. Int J Med Inform 2010;79:167–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.de Jager C, Schrijnemaekers A, Honey T, et al. Detection of MCI in the clinic: evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of a computerised test battery, the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test and the MMSE. Age Ageing 2009;38:455–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gunningberg L, Dahm M, Ehrenberg A. Accuracy in the recording of pressure ulcers and prevention after implementing an electronic health record in hospital care. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:281–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim E, Stolyar A, Lober W, et al. Challenges to using an electronic personal health record by a low-income elderly population. J Med Internet Res 2009;11:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Loh P, Flicker L, Horner B. Attitudes toward information and communication technology (ICT) in residential aged care in Western Australia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2009;10:408–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oasi C, Maman S, Baghéri H, et al. Validation of GABI: a simplified computerized assessment of functional decline in geriatrics. Presse Med 2008;37:1195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tsuboi K, Harada T, Ishii T, et al. Evaluation of correlations between a simple touch-panel method and conventional methods for dementia screening in the elderly. Int Med J 2009;16:175–9 [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wells J, Egan M, Byrne K, et al. Uses of the National Rehabilitation Reporting System: perspectives of geriatric rehabilitation clinicians. Can J Occup Ther 2009;76:294–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Agostini J, Concato J, Inouye S. Improving sedative-hypnotic prescribing in older hospitalized patients: provider-perceived benefits and barriers of a computer-based reminder. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23(Suppl. 1):32–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Boustani M, Munger S, Beck R, et al. A gero-informatics tool to enhance the care of hospitalized older adults with cognitive impairment. Clin Interv Aging 2007;2:247–53 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hesse K, Siebens H. Clinical information systems for primary care: more than just an electronic medical record. Top Stroke Rehabil 2002;9:39–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hornick T, Higgins P, Stollings C, et al. Initial evaluation of a computer-based medication management tool in a Geriatric Clinic. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2006;4:62–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Iliffe S, Kharicha K, Harari D, et al. Health risk appraisal for older people in general practice using an expert system: a pilot study. Health Soc Care Community 2005;13:21–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Merrick P, Secker D, Fright R, et al. The ECO computerized cognitive battery: collection of normative data using elderly New Zealanders. Int Psychogeriatr 2004;16:93–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rochon P, Field T, Bates D, et al. Computerized physician order entry with clinical decision support in the long-term care setting: insights from the Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1780–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Agostini J, Zhang Y, Inouye S. Use of a computer-based reminder to improve sedative-hypnotic prescribing in older hospitalized patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:43–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dorr D, Wilcox A, Brunker C, et al. The effect of technology-supported, multidisease care management on the mortality and hospitalization of seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:2195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fillit H, Simon E, Doniger G, et al. Practicality of a computerized system for cognitive assessment in the elderly. Alzheimers Dement 2008;4:14–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Galliher J, Stewart T, Pathak P, et al. Data collection outcomes comparing paper forms with PDA forms in an office-based patient survey. Ann Fam Med 2008;6:154–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gouin-Thibault I, Levy C, Pautas E, et al. Improving anticoagulation control in hospitalized elderly patients on Warfarin. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:242–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jette A, Haley S, Ni P, et al. Creating a computer adaptive test version of the late-life function and disability instrument. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008;63:1246–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Malone M, Vollbrecht M, Stephenson J, et al. Acute care for elders (ACE) tracker and e-geriatrician: methods to disseminate ACE concepts to hospitals with no geriatricians on staff. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:161–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Meurer W, Smith B, Losman E, et al. Real-time identification of serious infection in geriatric patients using clinical information system surveillance. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:40–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Trief PM, Teresi JA, Eimicke JP, et al. Improvement in diabetes self-efficacy and glycaemic control using telemedicine in a sample of older, ethnically diverse individuals who have diabetes: the IDEATel project. Age Ageing 2009;38:219–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bertera EM, Bertera RL, Russell M, et al. Training older adults to access health information. Educ Gerontol 2007;33:483–500 [Google Scholar]

- 109.Campbell R, Nolfi D. Teaching elderly adults to use the internet to access health care information: before-after study. J Med Internet Res 2005;7:e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Flynn K, Smith M, Freese J. When do older adults turn to the internet for health information? Findings from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:1295–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hanson E, Magnusson L, Oscarsson T, et al. Case study: benefits of IT for older people and their carers. Br J Nurs 2002;11:867–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nahm E, Preece J, Resnick B, et al. Usability of health Web sites for older adults: a preliminary study. Comput Info Nurs 2004;22:326–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Noel J, Epstein J. Social support and health among senior internet users: results of an online survey. J Technol Hum Serv 2003;21:33–54 [Google Scholar]

- 114.Shapira N, Barak A, Gal I. Promoting older adults’ well-being through Internet training and use. Aging Ment Health 2007;11:477–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chu A, Huber J, Mastel-Smith B, et al. “Partnering with seniors for better health”: computer use and internet health information retrieval among older adults in a low socioeconomic community. J Med Libr Assoc 2009;97:12–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lam L, Lam M. The use of information technology and mental health among older care-givers in Australia. Aging Ment Health 2009;13:557–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.McMillan S, Macias W. Strengthening the safety net for online seniors: factors influencing differences in health information seeking among older internet users. J Health Commun 2008;13:778–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tian Y, Robinson J. Incidental health information use and media complementarity: a comparison of senior and non-senior cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns 2008;73:340–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tse M, Choi K, Leung R. E-health for older people: the use of technology in health promotion. Cyberpsychol Behav 2008;11:475–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ybarra M, Suman M. Reasons, assessments and actions taken: sex and age differences in uses of Internet health information. Health Educ Res 2008;23:512–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Atienza AA, King AC, Oliveira BM, et al. Using hand-held computer technologies to improve dietary intake. Am J Prev Med 2008;34:514–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Berman RL, Iris MA, Bode R, et al. The effectiveness of an online mind–body intervention for older adults with chronic pain. J Pain 2009;10:68–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bickmore TW, Caruso L, Clough-Gorr K, et al. ‘It's just like you talk to a friend’ relational agents for older adults. Interact Comput 2005;17:711–35 [Google Scholar]

- 124.Henkemans OA Blanson, Rogers WA, Fisk AD, et al. Usability of an adaptive computer assistant that improves self-care and health literacy of older adults. Methods Info Med 2008;47:82–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Boissy P, Corriveau H, Michaud F, et al. A qualitative study of in-home robotic telepresence for home care of community-living elderly subjects. J Telemed Telecare 2007;13:79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Courtney KL. Privacy and senior willingness to adopt smart home information technology in residential care facilities. Methods Info Med 2008;47:76–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Demiris G, Rantz M, Aud M, et al. Older adults’ attitudes towards and perceptions of “smart home” technologies: a pilot study. Med Info Internet Med 2004;29:87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Joshi A, Arora M, Zhang D, et al. A prototype evaluation of a computer-assisted physical therapy system for osteoarthritis. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2008;31:71–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.King AC, Ahn DK, Oliveira BM, et al. Promoting physical activity through hand-held computer technology. Am J Prev Med 2008;34:138–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kolt GS, Oliver M, Schofield GM, et al. An overview and process evaluation of TeleWalk: a telephone-based counseling intervention to encourage walking in older adults. Health Promot Int 2006;21:201–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Libin A, Cohen-Mansfield J. Therapeutic robocat for nursing home residents with dementia: preliminary inquiry. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2004;19:111–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Shibata T, Wada K, Saito T, et al. Robotic therapy at an elderly institution using a therapeutic robot. Ann Rev CyberTher Telemed 2004;2:1125–35 [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wada K, Shibata T, Saito T, et al. A progress report of long-term robot assisted activity at a health service facility for the aged. Ann Rev CyberTher Telemed 2005;3:179–83 [Google Scholar]

- 134.Tamura T, Yonemitsu S, Itoh A, et al. Is an entertainment robot useful in the care of elderly people with severe dementia? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004;59:83–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, et al. Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:107–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Van Slyke C, Johnson RD, Hightower R, et al. Implications of researcher assumptions about perceived relative advantage and compatibility. The DATA BASE Adv Inform Syst 2008;39:50–65 [Google Scholar]

- 137.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 2004;82:581–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Gooch P, Roudsari A. Computerization of workflows, guidelines, and care pathways: a review of implementation challenges for process-oriented health information systems. J Am Med Info Assoc 2011;18:738–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Chocholik JK, Bouchard SE, Tan JK, et al. The determination of relevant goals and criteria used to select an automated patient care information system: a Delphi approach. J Am Med Info Assoc 1999;6:219–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Subramanian S, Hoover S, Gilman B, et al. Computerized physician order entry with clinical decision support in long-term care facilities: costs and benefits to stakeholders. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1451–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Saleem JJ, Patterson ES, Militello L, et al. Exploring barriers and facilitators to the use of computerized clinical reminders. J Am Med Info Assoc 2005;12:438–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Soar J, Seo Y. Health and aged care enabled by information technology. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007;1114:154–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]