Abstract

Purpose

This study was intended to identify the disease causing genes in a large Chinese family with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa and macular degeneration.

Methods

A genome scan analysis was conducted in this family for disease gene preliminary mapping. Snapshot analysis of selected SNPs for two-point LOD score analysis for candidate gene filter. Candidate gene PRPF31 whole exons' sequencing was executed to identify mutations.

Results

A novel nonsense mutation caused by an insertion was found in PRPF31 gene. All the 19 RP patients in 1085 family are carrying this heterozygous nonsense mutation. The nonsense mutation is in PRPF31 gene exon9 at chr19:54629961-54629961, inserting nucleotide “A” that generates the coding protein frame shift from p.307 and early termination at p.322 in the snoRNA binding domain (NOP domain).

Conclusion

This report is the first to associate PRPF31 gene's nonsense mutation and adRP and JMD. Our findings revealed that PRPF31 can lead to different clinical phenotypes in the same family, resulting either in adRP or syndrome of adRP and JMD. We believe our identification of the novel “A” insertion mutation in exon9 at chr19:54629961-54629961 in PRPF31 can provide further genetic evidence for clinical test for adRP and JMD.

Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and macular degeneration (MD) are a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of retinal dystrophies characterized by the progressive degeneration of photoreceptors, eventually resulting in severe visual impairment or blindness [1]. RP and MD are typically characterized as types of rod-cone dystrophy that are caused by the cell death of rod and cone photoreceptors. RP is characterized by a loss of peripheral vision, whereas MD is characterized by a loss of central vision. RP can be divided into autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and X -linked hereditary types [2]. The global incidence of RP is about 1/3,500, and more than 100 million people are affected worldwide [3]. MD can have a dominant or recessive inheritance pattern. MD or age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a leading cause of vision loss in those over the age of 55 years. Juvenile macular degeneration (JMD) is a rare disease that causes central vision loss, often beginning in childhood or young adulthood. Forms of JMD include Best disease, Stargardt's disease, and juvenile retinoschisis [4]. Until now, there have been no effective measures for RP and MD prevention and treatment.

Autosomal dominant RP (adRP) is a common inheritance model of RP. Thus far, 19 loci, including 18 genes, have been identified as adRP-causing genes (RetNetweb site, https://sph.uth.edu/retnet/sum-dis.htm); they are BEST1 (11q12.3), CA4 (17q23.2), CRX (19q13.32), FSCN2 (17q25.3), GUCA1B (6p21.1), IMPDH1 (7q32.1), KLHL7 (7p15.3), NR2E3 (15q23), NRL (14q11.2), PRPF3 (1q21.2), PRPF6 (20q13.33), PRPF8 (17p13.3), PRPF31 (19q13.42), PRPH2 (6p21.1), RDH12 (14q24.1), RHO (3q22.1), ROM1 (11q12.3), RP1 (8q12.1), RP9 (7p14.3), RPE65 (1p31.2), SEMA4A (1q22), SNRNP200 (2q11.2), TOPORS (9p21.1) and RP63 (6q23, genesremain to be identified). Among these genes, RHO and PRPF31 are the genes in which mutations are most commonly found in the Chinese population. In the RetNet database, there are also 26 loci, including 23 genes have been identified as being involved in autosomal recessive RP: (arRP) (ABCA4, BEST1, C2ORF71, C8ORF37, CERKL, CLRN1, CNGA1, CNGB1, CRB1, DHDDS, EYS, FAM161A, IDH3B, IMPG2, LRAT, MAK, MERTK, NR2E3, NRL, PDE6A, PDE6B, PDE6G, PRCD, PROM1, RBP3, RGR, RHO, RLBP1, RP1, RPE65, SAG, SPATA7, TTC8, TULP1, USH2A, and ZNF513). Five loci, including three genes (OFD1, RP2, and RPGR), have been identified as being involved in X-linked RP.

There are eleven genes that have been identified as being involved in autosomal dominant MD (adMD) (RetNet website), including BEST1, C1QTNF5, EFEMP1, ELOVL4, FSCN2, GUCA1B, HMCN1, PROM1, PRPH2, RP1L1, and TIMP3. Two genes, ABCA4 and CFH, have been identified as being involved in autosomal recessive MD (arMD); RPGR have been identified as being involved in X-linked MD. In addition, genes ABCA4, ARMS2, C2, C3, CFB, CFH, ERCC6, FBLN5, HMCN1, HTRA1, RAX2, TLR3, and TLR4 are associated with AMD.

In this study, we reported on a disease-causing gene in a large Chinese family 1085. In this family, 19 patients showed typical clinical symptoms of RP. Among these, five subjects showed RP syndrome and mild MD.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

This project was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital of Sichuan Academy of Medical Sciences and Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital, Chengdu, Sichuan, China. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and family members involved in this study. A written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Patient Recruitment

The 1085 family members with adRP were collected from Sichuan province. Family members were clinically diagnosed at the Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital. Peripheral blood samples of index cases and their family members were collected in EDTA tubes. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood by using the standard genomic DNA extraction method.

Genetic Analysis

Linkage analysis

Genome-wide screening was conducted using Linkage analysis chip01 (illumina) according to the protocol. All 1085 family samples were screened. Data set was analyzed using LINKAGE package.

Snapshot analysis

Seven SNPs around gene PRPF31 were selected for Snapshot analysis for fine chromosomal localization. The procedure of Snapshot analysis was carried out according to ABI PRISMSNaPshot™MultiplexKit protocol, and the processed samples were analyzed via an ABI 3130XL genetic analyzer.

Sanger sequencing analysis

To find mutations in the disease candidate gene, we used sanger sequencing analysis. The procedure was carried out according to the ABI BigDye sequencing protocol, and the processed samples were sequenced via an ABI3130XL genetic analyzer.

Clinical diagnosis

Ophthalmic examinations were executed, including of visual acuity, intraocular pressure, ocular motility, pupillary reaction, slit-lamp examination, dilated fundus examination and visual electrophysiological testing. SD-OCT was examined using SPECTRALIS® platform (Heidelberg engineering, Germany). mfERG was detected using RetIscan (Roland instruments, Germany).

Results

Clinical Manifestations of Members of the Pedigree

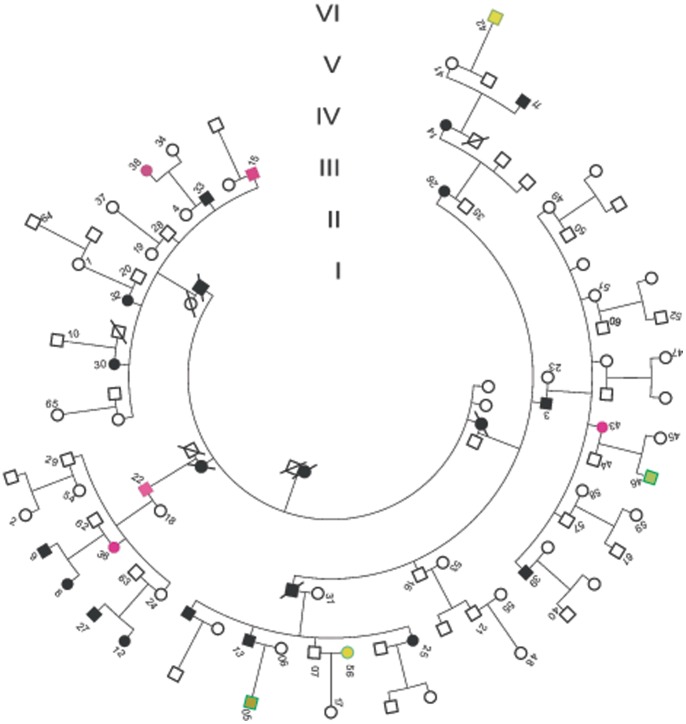

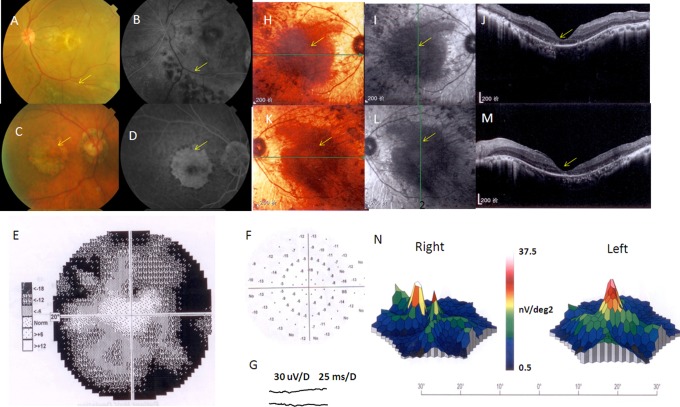

In this six-generation pedigree 1085, 65 members consented to participate in this study (Fig. 1). Nineteen individuals of the 1085 family were considered to be affected by RP, and 46 individuals were considered to be unaffected. A fundus examination of the patients showed typical RP features, including peripheral vision loss, night blindness, optic disk atrophy, retinal vascular stenosis, pigmentation, and the severe reduction or extinguishing of ERG. For example, typical pigmentation can be seen on the retina of subject 13, who experienced RP onset during his childhood (Fig. 2 A, B). An exception was subject 22, who experienced RP onset at the age of 48. The other patients experienced RP onset during their childhoods. Furthermore, patient 38 exhibited features of macular degeneration in her childhood or young adulthood (Fig. 2 C–G). Similar fovea centralisareflexia phenotype can be found in patients 15, 22, 36 and 43. For example, patient 15, both his right eye and left eye in macaia showed attenuation by SD-OCT examination (Fig. 2 H–M) and he has very low light stimulus reaction by mfERG examination (Fig. 2 N), especially in his right eye. Patients with fovea centralisareflexia are highlighted in red in Fig. 1. In addition to JMD, subjects 3, 14, 15, 25, 26, and 32 showed bilateral cataractvia by slit lamp examination. The detailed information on the affected patients is shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. The pedigree of the family 1085, with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa.

Normal individuals are shown as clear circles (female) or squares (male), and affected individuals are shown as solid symbols. Patients with fovea centralisareflexia are highlighted in red. This family contains six generations in total (shown in Roman numerals). Individuals with the PFPR31 gene mutation in the form of incomplete penetranceare are shown in green (samples 5, 42, 46, and 56).

Figure 2. Images of subjects 13, 38 and 35 from the family 1085. A and B are color fundus photographs and black-and-white fluorescein angiograms (FA) of subject 13.

Clinical changes were essentially identical for both eyes. Only the left eyes are shown here. The arrows point to abundant pigmentation. C and D are color fundus photographs and FA of subject 38, who was affected by RP syndrome and JDM. Clinical changes were identical for both eyes. Only the right eyes are shown here. In this case, the pigmentation revealed macularatrophy. The arrows point to pigmentation around the macular and macular atrophy. E and F are the visual fields of subject 38. G is the ERG response of subject 38; no A or B waves could be detected. H and I, right eye macular fundus figures of subject 15. J, OCT of subject 15′s right eye. The arrows directed for the macular pathology. K and L, the left eye macular fundus colored and black-and-white figures of subject 15. M, OCT of subject 15′s left eye. N, right and left eyes' mfERG pictures of subject 15.

Table 1. Features of the 1085 pegigree patients.

| Subject | Gender | Age | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | On-set of RP | Present VA | clinical symptoms |

| 1085-03 | Male | 82 | 173 | 65 | child | <<0.1 | RP, bilateral cataract |

| 1085-08 | female | 13 | 139 | 26 | child | <<0.1 | RP |

| 1085-09 | Male | 15 | 144 | 32 | child | <<0.1 | RP |

| 1085-11 | Male | 19 | 170 | 55 | child | 0.2/0.3 | RP |

| 1085-12 | female | 19 | 163 | 50 | child | <<0.1 | RP |

| 1085-13 | Male | 41 | 174 | 81 | child | <<0.1 | RP |

| 1058-14 | female | 43 | 160 | 57 | child | 0.3/0.3 | RP, bilateral cataract |

| 1085-15 | Male | 51 | 174 | 50 | child | 0.4/0.6 | RP, fovea centralis areflexia, bilateral cataract |

| 1085-22 | Male | 65 | 178 | 58 | 48 | <<0.1 | RP, fovea centralis areflexia |

| 1085-25 | female | 43 | 152 | 67 | child | <<0.1 | RP, bilateral cataract |

| 1085-26 | female | 68 | 159 | 50 | child | <<0.1 | RP, bilateral cataract |

| 1085-27 | Male | 17 | 165 | 45 | child | <<0.1 | RP |

| 1085-30 | female | 53 | 158 | 65 | child | 0.2/0.3 | RP |

| 1085-32 | female | 55 | 160 | 43 | child | 0.1/0.1 | RP, bilateral cataract |

| 1085-33 | Male | 46 | 177 | 74 | child | 0.5/0.5 | RP |

| 1085-36 | Female | 39 | 165 | 51 | child | <<0.1 | RP, fovea centralis areflexia |

| 1085-38 | Female | 21 | 170 | 55 | child | <<0.1 | RP, fovea centralis areflexia, JMD |

| 1085-39 | Male | 35 | 180 | 90 | 8 to 9 | N | RP |

| 1085-43 | Female | 37 | 160 | 60 | child | N | RP, fovea centralis areflexia |

Mutation Screening and SNP Genotyping Results

First, via genome-wide scan and Linkage analysis, rs9788, rs8109631, rs465169, rs36633, and rs8111838 in 19q13.42 were shown to be associated with RP in the 1085 family. In this locus, only the PRPF31gene is reported to be an adRPdisease-causing gene. Then, we selected seven SNPs around the PRPF31 gene, including rs4806711, rs56220912, rs10424816, rs254271, rs8109631, rs465169, and rs36633, for Snapshot analysis, using all 1085 family samples (primers designed for SNaPshot analysis are shown in Table 2). Via Snapshot and Linkage analysis, the maximum two-point LOD score is 2.64 at θ = 0.1 at rs10424816 (Table 3). This result suggested that the PRPF31 gene might be the disease-causing gene for the 1085 family. We next sequenced the complete exons and the flanking regions of the PRPF31 gene.

Table 2. Primers used for Snapshot analysis.

| SNP | Primer | Size | |

| rs4806711 | F | ACGTGAGTCCCTTTCCTCCT | 506bp |

| R | GGGGAAACCCCGTCTCTACT | ||

| Snapshot primer | AGGAGAGGTGAGTGTGATGG | ||

| rs56220912 | F | GCCAACCAGCAGAGTCTACC | 504bp |

| R | CCTCTCCAGCTCTCTGCACT | ||

| Snapshot primer | GCTCACTCTCGGACCCCCTC CCAGAGGCCT | ||

| rs10424816 | F | GGGCGTCTTTTCCTCTGG | 423bp |

| R | GTTCACTGCAACCTCCGTCT | ||

| Snapshot primer | CTAGGTCTGC TGTTGGAAGGTAGCATGAACCTACTGGCTT | ||

| rs254271 | F | GGCTGAAGTCAGGGTGTCAT | 407bp |

| R | ACAGATCCTGGTGTGGAAGG | ||

| Snapshot primer | TGCTTCTGTCTTCATATCTC | ||

| rs8109631 | F | CCCAGATTTGGAGTCAGCAT | 428bp |

| R | AGGGCTTCTCCCCAGTATGA | ||

| Snapshot primer | CAATCAGATGATCATCAATTATGTCAAAAG | ||

| rs465169 | F | ACCCAACCTCACCCTACCTC | 500bp |

| R | GCTGTGTTCTTGAGCCTTCC | ||

| Snapshot primer | GCTCCCTCCGCTCCGGTCTTCTACCCCAGGGCTGGTCTTT | ||

| rs36633 | F | AAGAGACCAGCCCCAGTTCT | 523bp |

| R | TTGGTGGTTTGAGTCCCTTC | ||

| Snapshot primer | CAGTCATGCTGCACACAGCTGATGACTGGGATGGAGGCATTAGCCCTGGA | ||

Table 3. Two-point LOD scores around disease causing gene PRPF31.

| SNP | Location (chr19) | θ = 0 | θ = 0.1 |

| rs4806711 | 54619191 | −2.24939 | 0.537837 |

| rs56220912 | 54626055 | 1.750628 | 1.44181 |

| rs10424816 | 54630208 | 1.69589 | 2.641756 |

| rs254271 | 54630757 | −0.78082 | 1.591041 |

| rs8109631 | 54080144 | 1.190325 | 2.612824 |

| rs465169 | 54526970 | 0.598506 | 2.773549 |

| rs36633 | 54646288 | 1.531824 | 1.285244 |

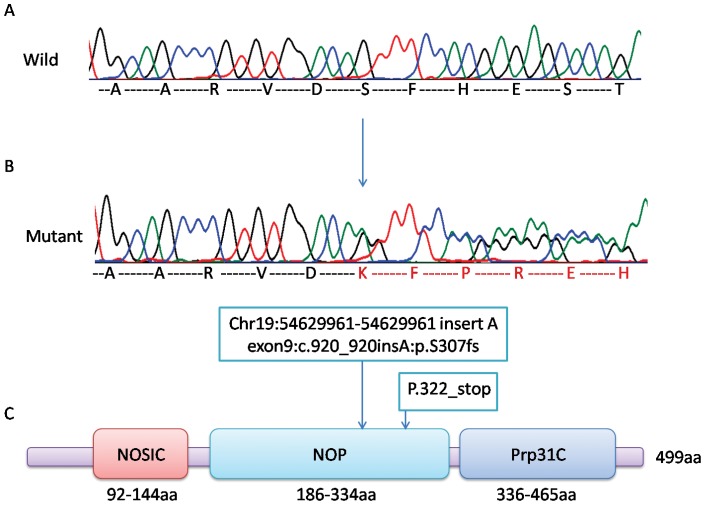

We sequenced the exons of PRPF31 gene, using all members of 1085 family. Primers designed to amplify all 14 exons and flanking regions of PRPF31 from the genomic DNA are shown in Table 4. We found that a novel heterozygous insertion in exon9 at chr19:54629961-54629961 (UCSC:feb.2009 (GRCH37/HG190)) that inserted an “A” nucleotide was co-segregated between patients and normal members (Figure 3AB). Mutations can be detected in all the affected samples. However, this mutation can also be detected in normal samples 5, 42, 46, and 56, showing partial penetrance (Figure 1 in green). This nonsense mutation leads to a protein frame shift from p.307andearly termination at p.322 in the snoRNA binding domain (NOP domain) (Figure 3C).

Table 4. Primers used for PRPF31 gene whole exons sequcencing.

| Exon | Primer | Size | |

| Exon1 | F | AGTTTCCTGTTTCCGGCTTC | 437bp |

| R | TAAAGACCCGCCTTTTTCCT | ||

| Exon2 | F | TTTGTCGGGGCAAGTTTTTA | 300bp |

| R | AAGCCTGTATCACCCCCTTC | ||

| Exon3 | F | TAGCAGGGGGCTCTAGACAG | 203bp |

| R | GCAGGAGAGACAGGAGATGG | ||

| Exon4 | F | CGAGAGGGGGTAGGGATTTA | 214bp |

| R | GAAAGGCCAGTGGGGAAG | ||

| Exon5 | F | AAAGGAAGAAGGGGACATGG | 214bp |

| R | AGAAGCACCCCACCTTCTCT | ||

| Exon6 | F | AGGAGGTGCTGAGCAAGAGA | 250bp |

| R | CGTGTGTAGCTCCAGCCTAA | ||

| Exon7 | F | CAGGTGTACACACGCACACA | 432bp |

| R | GCTGACCTCTGTGATGTCCA | ||

| Exon8 | F | TACTCACCCCCACCTCTCTG | 299bp |

| R | GTGGCTGCTCAGGCTGTC | ||

| Exon9 | F | CGGTTGCTTTGCTGTTACCT | 209bp |

| R | CAGGCCCAGAGGAAAAGAC | ||

| Exon10 | F | TTTAACTAAGGCACGTGGATACTC | 267bp |

| R | CATGACCCCCATGCCTAC | ||

| Exon11 | F | GGTAGGCATGGGGGTCAT | 250bp |

| R | GCCACAGGACGAGAGGAG | ||

| Exon12 | F | TAGATCGAGGAGGACGCCTA | 207bp |

| R | ACAGGGAGGCTGCGATCT | ||

| Exon13 | F | ACCGAGGGACACAAGGTG | 244bp |

| R | CTCATCCTGGCCTTCTTCAC | ||

| Exon14 | F | GGCTCTGATGGGTCACAGTT | 514bp |

| R | CCGGCTGTTTGAAAAATGAT | ||

Figure 3. Detected mutation in the PRPF31 gene.

A is the wild type sequence peak chart of the PRPF31 gene. B is the mutant type sequence peak chart of the PRPF31 gene: the heterozygous mutation that results in a single “A” nucleotide's insertion at chr19:54629961-54629961 (exon9, c.920_920insA). This insertion leads to the coding protein's frame shift at p.307 and early termination at p.322. C is the predicted PRPF31 protein's domains, showing that the mutation is in the functional domain NOP, whichis essential for U4/U6-U5 tri-snRNP formation.

Discussion

In our pedigree, we found one novel PRPF31mutation in a large adRP family. In this family, subject 38 showed adRP and JMD. Subjects 15, 22, 36, and 43 showed both adRP and fovea centralisareflexia. According to our findings, we propose that the PRPF31 gene is the gene that causes adRP and MD. Although six subjects showed bilateral cataracts, it is difficult to diagnose the genetic factors of cataracts for RP patients over 40 years of age. RP and MD are the most common degenerative diseases of the retina. To date, about eight genes have been identified as disease-causing genes for patients with RP and/or MD. For example, mutations in ABCA4, the photoreceptor ABC transporter, are associated with Stargardt macular degeneration [5] and arRP [6]–[7]. Mutations in BEST1 can cause multifocal Best vitelliform MD (Best disease) [8] and adRP [9]. Mutations in FSCN2 [10]–[11] and PRPH2 (peripherin/RDS) [12]–[13] can cause adMDand adRP. Mutations in PROM1 [14]–[15], RP1 [16], RPE65 [17]–[19], and RPGR [20]–[21] can also cause MD and/or RP.

The PRPF31gene codes for the splicing factor hPRP31. Mutations in PRPF31 have been repeatedly found to be associated with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (adRP). In 1994, an adRP locus on 19q13.4 (RP11) was first localized via Linkage analysis in a large British family [22]. Then, within this region, mutations in the PRPF31 gene were identified in other families and sporadic cases [23]. Mutations in PRPF31 are inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, accounting for about 5% of cases of adRP [1]. Additionally, genomic rearrangements of the PRPF31 gene account for about 2.5% of adRP cases [24]–[25]. Various mutations have been identified in the PRPF31 gene that are associated with adRP, including 769–770insA [26], the in-frame deletion of four amino acids 111–114 [27], splice site mutation (IVS8+1G>C) [28], A194E, A216P [29], and c. 1142 del G [30].

PRPF31 is one of the three pre-mRNA splicing factors that encode components of thespliceosomeU4/U6*U5 tri-snRNP [31], which has been identified as causing adRP (the other two genes are PRPF3 and PRPF8) [26]. This complex can excise introns from RNA transcripts. The disease mechanism for RP11 is caused by mutations in the splicing factor gene PRPF31 because its' splicing function is incomplete [32]. These spliceosome proteins are highly conserved in eukaryotes ranging from mammals to yeast.

The underlying mechanism via which PRPF31 causes adRP and MD is still unknown. The inheritance pattern of PRPF31 mutation is atypical of dominant inheritance [33], which suggests partial penetrance: a dominant mutation appears to “skip” generations. A significant difference in wild-type and mutant PRPF31 mRNA levels was observed between symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals; this can partially explain the incomplete penetrance phenotype of adRP caused by PRPF31 mutation [34]. However, there are probably more subtle molecular mechanisms underlying this disease [35]. In zebrafish, it was suggested that distinct mutations in PRPF31 can lead to photoreceptor degeneration via different mechanisms, such as haplo-insufficiency or dominant-negative effects [36].

The PRPF31gene codes for 499 amino acids (55 kD). The PRPF31 protein contains three domains: NOSIC (NOSIC NUC001 domain, from 92aa to 144aa), NOP (snoRNA binding domain, from 186aa to 334aa), and Prp31C (terminal domain, from 336aa to 465aa). Previously, yeast two-hybrid analysis result had shown that the NOP domain is a genuine RNP-binding module, exhibiting RNA- and protein-binding surfaces [37]. In this study, we found a frame shift insertion mutation in the NOP domain area. This mutation causes the protein frame shift at p.307 and early termination at p.322 after coding for 15 missense amino acids. This nonsense protein suggested aberrant hPrp31-hPrp6 interaction that blocks U4/U6-U5 tri-snRNP formation, which may be the reason that the 1085 family was affected by adRP and MD.

In summary, we have, for the first time, identified a heterozygous insertion in exon9 at chr19:54629961-54629961 (UCSC:feb.2009 (GRCH37/HG190)), inserting an “A” nucleotide mutation in the PRPF31 gene, causing typical adRP and JMD. Our study provides evidence that a mutation in the PRPF31 gene is related, at least partially, to the pathogeneses of both adRP and JMD.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participating patients and their families of 1085 family.

Funding Statement

The authors acknowledge the following grants support: National natural science foundation of China (No.81070761 and 81241001 to FL; No.81025006 to ZY; No.81271048 to JY) and youth science & technology foundation of Sichuan province (to FL and to ZY). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP (2006) Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet 368: 1795–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hamel C (2006) Retinitis pigmentosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis 1: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Golovleva I, Kohn L, Burstedt M, Daiger S, Sandgren O (2010) Mutation spectra in autosomal dominant and recessive retinitis pigmentosa in northern Sweden. Adv Exp Med Biol 664: 255–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Francois J (1979) Juvenile macula degeneration. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 175: 715–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rossi S, Testa F, Attanasio M, Orrico A, de Benedictis A, et al. (2012) Subretinal Fibrosis in Stargardt's Disease with Fundus Flavimaculatus and ABCA4 Gene Mutation. Case Report Ophthalmol 3: 410–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mullins RF, Kuehn MH, Radu RA, Enriquez GS, East JS, et al. (2012) Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa due to ABCA4 mutations: clinical, pathologic, and molecular characterization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53: 1883–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rudolph G, Kalpadakis P, Haritoglou C, Rivera A, Weber BH (2002) Mutations in the ABCA4 gene in a family with Stargardt's disease and retinitis pigmentosa (STGD1/RP19). Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 219: 590–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maia-Lopes S, Castelo-Branco M, Silva E, Villaverde C, Aguirre J, et al. (2008) Gene symbol: BEST1. Disease: Best macular dystrophy. Hum Genet 123: 110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davidson AE, Millar ID, Urquhart JE, Burgess-Mullan R, Shweikh Y, et al. (2009) Missense mutations in a retinal pigment epithelium protein, bestrophin-1, cause retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet 85: 581–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wada Y, Abe T, Itabashi T, Sato H, Kawamura M, et al. (2003) Autosomal dominant macular degeneration associated with 208delG mutation in the FSCN2 gene. Arch Ophthalmol 121: 1613–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gamundi MJ, Hernan I, Maseras M, Baiget M, Ayuso C, et al. (2005) Sequence variations in the retinal fascin FSCN2 gene in a Spanish population with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa or macular degeneration. Mol Vis 11: 922–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khani SC, Karoukis AJ, Young JE, Ambasudhan R, Burch T, et al. (2003) Late-onset autosomal dominant macular dystrophy with choroidal neovascularization and nonexudative maculopathy associated with mutation in the RDS gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44: 3570–3577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lim KP, Yip SP, Cheung SC, Leung KW, Lam ST, et al. (2009) Novel PRPF31 and PRPH2 mutations and co-occurrence of PRPF31 and RHO mutations in Chinese patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol 127: 784–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Permanyer J, Navarro R, Friedman J, Pomares E, Castro-Navarro J, et al. (2010) Autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa with early macular affectation caused by premature truncation in PROM1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51: 2656–2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Michaelides M, Gaillard MC, Escher P, Tiab L, Bedell M, et al. (2010) The PROM1 mutation p. R373C causes an autosomal dominant bull's eye maculopathy associated with rod, rod-cone, and macular dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51: 4771–4780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen LJ, Lai TY, Tam PO, Chiang SW, Zhang X, et al. (2010) Compound heterozygosity of two novel truncation mutations in RP1 causing autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51: 2236–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morimura H, Fishman GA, Grover SA, Fulton AB, Berson EL, et al. (1998) Mutations in the RPE65 gene in patients with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa or leber congenital amaurosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95: 3088–3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gollapalli DR, Rando RR (2004) The specific binding of retinoic acid to RPE65 and approaches to the treatment of macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 10030–10035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moiseyev G, Nikolaeva O, Chen Y, Farjo K, Takahashi Y, et al. (2010) Inhibition of the visual cycle by A2E through direct interaction with RPE65 and implications in Stargardt disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 17551–17556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ayyagari R, Demirci FY, Liu J, Bingham EL, Stringham H, et al. (2002) X-linked recessive atrophic macular degeneration from RPGR mutation. Genomics 80: 166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fujita R, Swaroop A (1996) RPGR: part one of the X-linked retinitis pigmentosa story. Mol Vis 2: 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. al-Maghtheh M, Inglehearn CF, Keen TJ, Evans K, Moore AT, et al. (1994) Identification of a sixth locus for autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa on chromosome 19. Hum Mol Genet 3: 351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Al-Maghtheh M, Vithana E, Tarttelin E, Jay M, Evans K, et al. (1996) Evidence for a major retinitis pigmentosa locus on 19q13.4 (RP11) and association with a unique bimodal expressivity phenotype. Am J Hum Genet 59: 864–871. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abu-Safieh L, Vithana EN, Mantel I, Holder GE, Pelosini L, et al. (2006) A large deletion in the adRP gene PRPF31: evidence that haploinsufficiency is the cause of disease. Mol Vis 12: 384–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sullivan LS, Bowne SJ, Seaman CR, Blanton SH, Lewis RA, et al. (2006) Genomic rearrangements of the PRPF31 gene account for 2.5% of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 4579–4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martinez-Gimeno M, Gamundi MJ, Hernan I, Maseras M, Milla E, et al. (2003) Mutations in the pre-mRNA splicing-factor genes PRPF3, PRPF8, and PRPF31 in Spanish families with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44: 2171–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang L, Ribaudo M, Zhao K, Yu N, Chen Q, et al. (2003) Novel deletion in the pre-mRNA splicing gene PRPF31 causes autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa in a large Chinese family. Am J Med Genet A 121A: 235–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu SS, Zhao C, Cui Y, Li ND, Zhang XM, et al. (2005) [Novel splice-site mutation in the pre-mRNA splicing gene PRPF31 in a Chinese family with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa]. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi 41: 305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilkie SE, Morris KJ, Bhattacharya SS, Warren MJ, Hunt DM (2006) A study of the nuclear trafficking of the splicing factor protein PRPF31 linked to autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (ADRP). Biochim Biophys Acta 1762: 304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Taira K, Nakazawa M, Sato M (2007) Mutation c. 1142 del G in the PRPF31 gene in a family with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (RP11) and its implications. Jpn J Ophthalmol 51: 45–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Makarova OV, Makarov EM, Liu S, Vornlocher HP, Luhrmann R (2002) Protein 61K, encoded by a gene (PRPF31) linked to autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa, is required for U4/U6*U5 tri-snRNP formation and pre-mRNA splicing. EMBO J 21: 1148–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deery EC, Vithana EN, Newbold RJ, Gallon VA, Bhattacharya SS, et al. (2002) Disease mechanism for retinitis pigmentosa (RP11) caused by mutations in the splicing factor gene PRPF31. Hum Mol Genet 11: 3209–3219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Talmud PJ, Converse C, Krul E, Huq L, McIlwaine GG, et al. (1992) A novel truncated apolipoprotein B (apo B55) in a patient with familial hypobetalipoproteinemia and atypical retinitis pigmentosa. Clin Genet 42: 62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vithana EN, Abu-Safieh L, Pelosini L, Winchester E, Hornan D, et al. (2003) Expression of PRPF31 mRNA in patients with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa: a molecular clue for incomplete penetrance? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44: 4204–4209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tanackovic G, Rivolta C (2009) PRPF31 alternative splicing and expression in human retina. Ophthalmic Genet 30: 76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yin J, Brocher J, Fischer U, Winkler C (2011) Mutant Prpf31 causes pre-mRNA splicing defects and rod photoreceptor cell degeneration in a zebrafish model for Retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Neurodegener 6: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu S, Li P, Dybkov O, Nottrott S, Hartmuth K, et al. (2007) Binding of the human Prp31 Nop domain to a composite RNA-protein platform in U4 snRNP. Science 316: 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]