Abstract

The thermally induced conformational switching of a stacked dialkxoynaphthalene- naphthalenetetracarboxylic diimide (DAN-NDI) amphiphilic foldamer to an NDI-NDI fibril aggregate is described. The aggregated fibril structures were explored by UV-Vis, CD, AFM and TEM. Our findings indicate that the aromatic DAN-NDI interactions of the original foldamer undergoes transformation to a fibrillar assembly with aromatic NDI-NDI stacked interactions. These structural insights could help inform new molecular designs and increase our understanding of the fibrillar assembly and aggregation process in aqueous solution.

Keywords: Pi interactions, Aggregate, Supramolecular chemistry, Self assembly, Synthetic Biology

Introduction

The development of well-defined architectures using non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, van der Waals interactions and desolvation remains a frontier area of chemistry. An important aspect of the self-assembly of organic molecules can be the energetics and geometry of interacting aromatic units. Typical geometries include the herringbone arrangement favoured by smaller aromatics, off-set parallel stacking and even face-centered parallel stacking in certain situations. A predictive understanding of stacking geometry put forth by Hunter and Sanders in the 1990s was based upon the overall polarization of the aromatic pi cloud.[1] These considerations rationalized why some highly polarized aromatics might exhibit off-set stacking geometries while electron-rich and electron-deficient aromatics tended toward alternating face-centered stacks. More recently, Waters[2] and especially Wheeler and Houk[3] and now Wheeler,[4] have refined these ideas to include a focus on direct through-space interactions between polarized groups on the periphery of aromatic rings. Our own work has emphasised the important role that desolvation effects in strongly interacting solvents, especially water, can play in the energetics of aromatic stacking.[5]

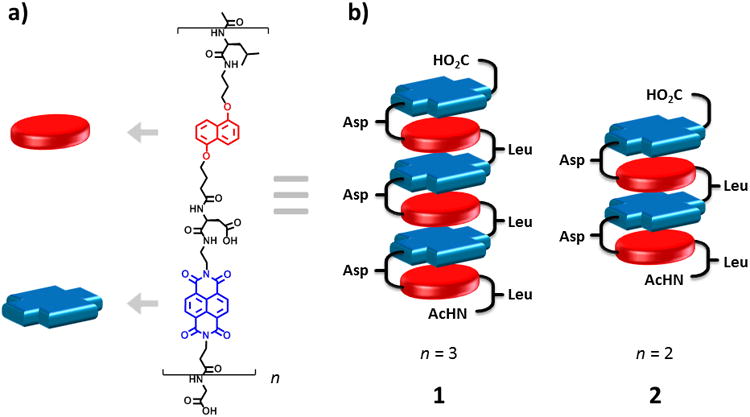

Previous work in our group detailed the ability of amphiphilic foldamer 1 (commonly referred to as an aromatic electron donor-acceptor foldamer, or aedamer), composed of covalently linked alternating relatively electron-rich 1,5-dialkoxynaphthalene (DAN) and relatively electron-deficient 1,4,5,8-naphthalenetetracarboxylic diimide (NDI), (Figure 1) to undergo a non-covalent, irreversible conformational change into a more highly ordered aggregate after heating.[6] The process was shown to be nucleation-dependent[7] and could be described as analogous to the amyloid formation process. To our knowledge, these attributes make it the only abiotic molecule to exhibit such behaviour.

Figure 1.

a) Structure of amphiphilic foldamers and b) cartoon representation of hexamer (1) and tetramer (2) in the pleated structure (Asp = aspartic acid, Leu = leucine).

The largest group of protein misfolding diseases involves amyloid fibrils and is associated with numerous neurodegenerative diseases, most famously Alzheimer's disease.[8] Amyloid fibril formation follows the irreversible conformational change of globular proteins into self-assembled, highly ordered β-sheet-rich fibrillar structures and generally proceeds via a nucleation-dependent mechanism.[9] Two classes of molecules are able to exhibit amyloid formation: globular proteins that exist as folded or partially folded species and then undergo a transformation into fibrillar structures, and polypeptides without globular structure which then aggregate into ordered fibrils. For both classes, the initial monomeric state overcomes an entropic barrier that transforms a kinetically soluble, stable molecule into an insoluble, more thermodynamically stable fibril aggregate. Both classes are initially monomeric in solution, but as the initial structures reorder and nucleation-dependent self-assembly commences, “one-dimensional crystallization” occurs.[9b] It has been proposed that attractive interactions between hydrophobic surfaces on protofilament strands are responsible for the merging of protofilament strands into multistranded fibril precursors which then go on to form mature fibril aggregates.[10] A model proposed by Petkova et al. used hydrophobic interactions to show the merging of two Aβ1-40 cross β-strand units wherein the C-terminal hydrophobic residues are sequestered on the interior of a dimer unit juxtaposing the more hydrophilic N-terminal residues on the exterior.[11]

Alternating DAN-NDI foldamers exhibited an alternating face-centered stacked aromatic core geometry in aqueous solution, based on detailed NMR and full spectroscopic characterization.[5,12] However, for systems composed solely of NDI, off-set parallel stacking has been observed by several groups. For example, Parquette et al. have reported several systems displaying NDI-NDI off-set parallel stacking in the formation of one-dimensional (1D) nanofibrils[13] and 1D nanotubes.[14] Ghosh et al. have reported NDI-NDI off-set parallel stacking in the design of 2D vesicles[15] and fibers[16] while Govindaraju et al. have reported the formation of 1D fibers, spheres, sheets[17] and 1D nanobelts.[18] In 2005, Matile and coworkers designed, synthesized and characterized a synthetic ion channel using aromatic electron donor-acceptor interactions.[19] Their design utilized a rigid-rod NDI-NDI off-set architecture that underwent a conformational change and opened to form a barrel-stave ion channel in response to intercalation of DAN monomer between the NDI-NDI units. Here, we explore the structure of hexamer (1) and tetramer (2) amphiphilic foldamers (Figure 1) after heating to an aggregated state. SEM, TEM and AFM revealed a twisted-ribbon fibrillar morphology. We propose a structural model based on circular dichroism (CD) spectra, in which the foldamer aromatic core undergoes an irreversible thermally induced conformation transition from face-centered DAN-NDI stacking to fibril assembly based on NDI-NDI off-set parallel stacking.

Results and Discussion

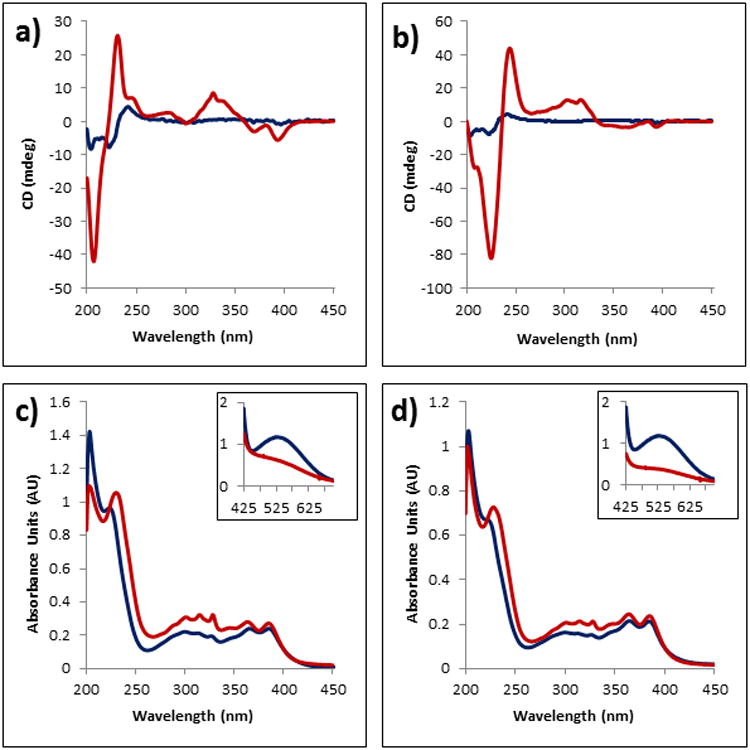

Investigation of foldamers 1 and 2 by CD showed minimal signal in the near UV and none in the far UV prior to heating (Figure 2a,b). Both foldamer solutions were then heated to 80 °C for 90 min to facilitate the aggregation process. After heating, strong bisignate couplet signals appeared for 1 and 2, with the null occurring at 215 and 235 nm, respectively, indicative of exciton Cotton effects along the NDI y-polarized (short) transition axis.[20] Moderate signals at 325, 360, and 390 nm also appeared for 1, while 2 gave moderate signals at 310, 353, and 390 nm. Both of these correspond to electronic transitions along the NDI z-polarized (long) transition axis. The bisignate Cotton effect in the near-UV is typical of molecular systems composed of off-set stacked NDI-NDI molecules.[13,14b,20a,21]

Figure 2.

CD, UV and Visible spectra of foldamers 1 and 2 before (blue) and after (red) heating at 80 °C for 90 min. a) Foldamer 1 CD spectrum; b) Foldamer 2 CD spectrum; c) Foldamer 1 UV spectrum; d) Foldamer 2 UV spectrum. Inset of c) and d) show the visible region of foldamers 1 and 2, respectively, with loss of the CT band after heating. Foldamer concentrations are 0.2 mM, 15 μM, 2.0 mM in a 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer for CD, UV and Visible spectroscopy, respectively.

UV-Vis spectra of 1 prior to heating showed a broad charge transfer (CT) band in the visible region (λmax 526 nm) and several peaks in the UV region indicative of electronic transitions across the NDI long axis (300, 360, 380 nm) (Figure 2c, inset). Disappearance of the CT band after heating occurs along with a slight decrease in hypochromism in the far-UV region. Foldamer 2 showed a similar UV-Vis spectrum prior to heating, with peaks at 300, 359 and 380 nm in the far-UV and a broad CT band (λmax 526 nm) in the visible region (Figure 2d, inset). Heating of 2 also resulted in loss of the CT band, with a slight decrease in hypochromism in the far-UV. The appearance of a new peak, formerly a shoulder, after heating at 219 (1) and 223 nm (2) is thought to correspond to electronic transitions across the NDI short axis. A similar trend was observed when a DAN monomer was titrated into a solution of NDI monomer (see the Supporting Information, Figure S1). A peak corresponding to electronic transitions across the NDI short axis at 232 nm was overtaken by a peak at 222 nm corresponding to DAN electronic transitions. When the UV spectra are compared to the CD spectra, the newly emerged peak in the aggregated state of foldamers 1 and 2 nearly intercept the null of the bisignate Cotton effects, indicative of NDI self-assembly (see the Supporting Information, Figures S2 and S3).[20,21]

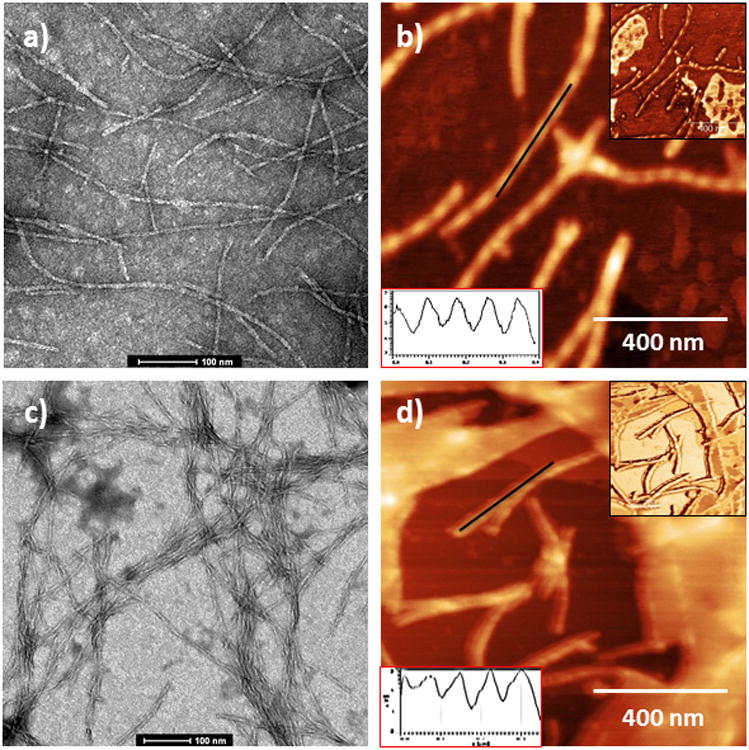

To our surprise, 1D fibrils were observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) after heating solutions of 1 and 2 to the aggregated state and staining with 2% uranyl acetate (Figure 3a,c). Fibril formation was also observed in samples used for CD analysis. As shown in Figure 3, negatively stained aggregated samples revealed fibrils with uniform widths up to a micrometer in length for 1 and 2. While TEM images of 1 showed fibrils with a diameter of 10.5 ± 1 nm, 2 revealed fibrils of 7.5 ± 1 nm in diameter. As shown by TEM, the fibrils tend to “stick to” and “wrap around” each other, indicating some extent of inter-fibril interaction (see the Supporting Information, Figure S4). The presence of 1D fibrils indicates the requirement for 1D growth in the aggregated foldamer structure.

Figure 3.

TEM and AFM images of foldamers 1 and 2 (TEM, 2% uranyl acetate staining on carbon/Formvar grid; AFM, freshly cleaved mica). a) TEM of foldamer 1; b) AFM of foldamer 1; c) TEM of foldamer 2; d) AFM of foldamer 2. Red inset for b,d) represents the height profile along black line. Black inset for b,d) shows the phase image corresponding to shown topography.

In order to gain additional insight into the fibril morphology, tapping-mode atomic force microscopy (AFM) was utilized. Deposition of the foldamer aggregates onto freshly cleaved mica revealed 1D fibrils similar to those observed by TEM for 1 and 2 (Figure 3b,d). Both foldamer aggregates showed fibrils with regular helicity with a pitch of ∼170 nm for 1 and ∼150 nm for 2. While 1 had a height profile of 5.5 ± 1 nm, 2 showed a height profile of 4 ± 1 nm, both approximately one-half of the fibril width observed by respective TEM images. AFM phase images of each foldamer detailing the helical twist are shown in the inset. Differences in fibril width between TEM and AFM may be attributed to compression of the aggregate sample by the AFM tip or due to AFM tip and/or cantilever geometry.[14b,22] Attempts to investigate the aggregates further by X-ray diffraction and solid state NMR yielded ambiguous results.

The fibril twisting observed by AFM is consistent with helical, off-set parallel-displaced NDI-NDI interactions seen in previous work with NDI monomers.[13] Importantly, the measured fibril widths of 11 nm and 7.5 nm are each in agreement with the calculated extended lengths of 1 and 2, respectively. Coincidentally, the twisted-ribbon fibril morphology of the foldamer aggregate is similar to that of a twisted-ribbon structure often found in aggregated amyloid proteins.[22,23] Off-set parallel displaced NDI-NDI interactions leading to highly ordered aggregates have been shown in numerous studies with CD of NDI monomers.[13-19] It has been suggested that the order and directionality of aromatic stacking interactions in amyloidogenic peptides and de novo designed peptides can act as a thermodynamic driving force for the formation of amyloid and amyloid-like fibril assembly.[24] Also interesting is the requirement for amphiphilicity in the formation of one-dimensional fibril-containing structures as seen in both abiotic and biotic systems.[25] Based on this information, we believe that while aromatic NDI-NDI interactions facilitate 1D fibril growth in the aggregated structure, the amphiphilic nature of the molecule contributes to the thermodynamic driving force for fibril formation.

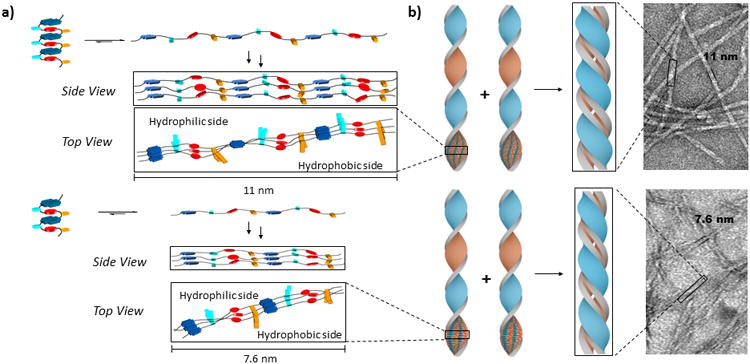

A proposed model for the foldamer aggregated structure and formation based on the bisignate CD signal, the 1D fibrils observed by TEM and the fibril twisted-ribbon shape by AFM is proposed in Figure 4. Upon heating, unfolding of the foldamer DAN-NDI pleated aromatic structure occurs, as evidenced by disappearance of the CT band. Reorganization of the core aromatics in the aggregated structure into a stable fibril is believed to be initiated by NDI-NDI off-set parallel-displaced stacking the between NDI units of the two oligomers. More unfolded oligomers assemble as the nucleation process continues, so that a relatively stable ribbon is formed. Assembly continues in one-dimension, leading to an amphiphilic ribbon structure in which all hydrophobic leucines organize on one surface and the hydrophilic aspartates are arranged on the other (Figure 4a). We propose that dimerization of the sheets occurs to sequester the hydrophobic leucine surfaces on the interior of a pseudo bilayer assembly, juxtaposing the hydrophilic aspartates on the exterior (Figure 4b). The assembled duplex ribbon grows in length until it becomes the fully assembled fibril observed in the TEM and AFM studies. We are not yet sure of the spatial organization of the DAN units in the fibril structure because we have no direct spectroscopic data that defines their relative orientations.

Figure 4.

Proposed model describing how the pleated amphiphilic foldamer undergoes a conformational change to self-assembled one-dimensional fibrils. a) Upon heating, unfolding of the pleated DAN-NDI structure (light blue and orange rectangles represent aspartate and leucine side chains, respectively) occurs to form a new structure that self-assembles around offset NDI-NDI stacking. The resulting ribbon has a hydrophilic side and a hydrophobic side; b) Dimerization of the amphiphilic ribbons is proposed to sequester the hydrophobic leucine face on the interior and juxtaposes the hydrophilic aspartate face on the exterior of the fibril.

It appears that at least three features are required for an abioitic molecule to exhibit the kind of conformational switching, reminiscent of amyloid fibril formation, observed here. First, there must be a kinetically stable initial folded structure that is based largely on intramolecular interactions. In the case of amphiphilic foldamer 1, the kinetically folded structure is based on intramolecular alternating DAN-NDI stacks. Second, there must be an alternative aggregated state possible that involves an unfolded conformation. For foldamer 1, we have now shown that this alternative mode of aggregation between unfolded chains involves NDI-NDI interactions. Third, we believe that there must be amphiphilicity present so that this alternative mode of interchain aggregation leads to formation of both a hydrophobic face and a hydrophilic face in the growing aggregate.

Stabilization of the fibril comes when two of the hydrophobic faces interact to create a fully desolvated hydrophobic interior and hydrophilic outer faces in a pseudo bilayer arrangement. One could propose that it is the desolvation of the considerable hydrophobic interior of the growing fibrillar assembly that provides the ultimate driving force for the thermodynamic stability of the fibril. Note there is likely a length dependence to this stability that explains why nucleation kinetics (i.e. a lag in fibril formation upon heating) is a hallmark of this process. During the lag (nucleation) phase, intermediates form and disassemble until the critical length is achieved, after which the fibril forms by quickly adding unfolded chains to each end of the now thermodynamically stable structure.

Conclusions

The face-centered geometry observed in the amphiphilic foldamer prior to heating is correctly predicted by the work of Wheeler when one considers the maximization of complementary interactions between the relatively electron-rich DAN oxygen atoms and relatively electron-deficient NDI carbonyl carbon atoms in the stacked structure. The same considerations also predict strong complementary interactions between the highly polarized carbonyls of two off-set stacked NDI molecules, i.e. the carbonyl oxygen of one NDI carbonyl interacting with the carbonyl carbon of the adjacent NDI.

This unique proposed conformational switching process - from an aromatic DAN-NDI foldamer to an aromatic NDI-NDI fibril-forming aggregate - illustrates a new model of self-assembly behaviour. Nevertheless, this proposed desolvation model can be seen as analogous to the proposed dimerization of Aβ1-40 cross stand β-sheets described earlier:[11] for our aggregated amphiphilic foldamer structure and for proteins and polypeptides in the amyloid state, there exists a strong requirement to shield the more hydrophobic residues on the interior of a two-strand dimer while juxtaposing the more hydrophilic residues in the solvent-exposed exterior. In this light, our material bridges the gap between biotic proteins and polypeptides that form amyloid and synthetically derived, abiotic molecules that form highly ordered 1D fibril aggregates.

Experimental Section

General methods

Foldamers 1 and 2 were synthesized and purified according to a previously reported protocol (more details available in the supporting information).[6] All commercially available chemicals were purchased from Aldrich, Fisher Scientific or Novabiochem/EMD/Merck unless otherwise indicated. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were taken on a Varian Unity Plus 400 spectrometer at 400 MHz in CDCl3 or d6-DMSO. All amphiphilic foldamer purification was done on a Waters HPLC system equipped with a 2996 photodiode array detector and Grace-Vydac C18 peptide semi-preparatory reverse phase column.

UV-Vis spectroscopy

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy was performed on a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 35 spectrophotometer. Foldamer solutions (50 uM for UV; 0.2 mM for Vis) were observed in a 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer with 100 mM NaCl added and pH adjusted to 7.0. A 1 cm cuvette was used and initial spectra were observed at room temperature (27 °C). Samples were then heated in a 80 °C oil bath for 2 hrs, cooled at room temperature for 30 min and then final spectra were recorded. All samples were filtered using a 0.45 μm nylon filter prior to recording spectra.

Circular dichroism

Circular dichroism (CD) experiments were performed on a Jasco J-815 circular spectropolarimeter and all spectra were collected using a 1 mm quartz cell. Samples (0.2m) were dissolved in a 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer with 100 mM NaCl, pH adjusted to 7.0 and initial spectra were recorded at 27 °C. Samples were then heated to 80 °C for 90 min using a Jasco-equipped Peltier temperature controller and final spectra were recorded after allowing the samples to cool to room temperature for 30 min. All samples were filtered using a 0.45 μm nylon filter prior to recording spectra.

Atomic force microscopy

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was performed on a Dimension 3100 atomic force microscope with silicon tips (NSC14/AIBS, MicroMasch) in tapping mode. Samples were prepared by allowing a drop of the foldamer aggregated solution to dry on mica plates overnight.

Transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained using a FEI Tecnai microscope operating at 80 kV. Samples were prepared by placing a drop of the aggregated foldamer solution onto 400 mesh carbon coated copper Formvar grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Inc.) for 5 min. Removal of the remaining solution after 5 min was followed by addition of a 2% uranyl acetate solution for negative staining. After allowing the stain to sit for 2 min it was removed and the sample was allowed to dry before analysis.

Supporting Information

Included in the supporting information are details on the synthesis of foldamers 1 and 2, additional TEM and AFM images and figures showing the overlap of the CD and UV spectra.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Robert A. Welch Foundation grant (F1188) and the National Institute of Health (GM-069647). The authors would like to thank The Welch Foundation in support of the facilities used in this work. The authors gratefully acknowledge D. Romanovicz and Dr. J. Collier for their assistance in TEM image collection.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chemeurj.org/ or from the author.

References

- 1.Hunter CA, Sanders JKM. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:5525–5534. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rashkin MJ, Waters ML. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1860–1861. doi: 10.1021/ja016508z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wheeler SE, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10854–10855. doi: 10.1021/ja802849j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wheeler SE. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:10262–10274. doi: 10.1021/ja202932e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Cubberley M, Iverson BL. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7560–7563. doi: 10.1021/ja015817m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lokey RS, Iverson BL. Nature. 1995;375:303–305. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford VJ, Iverson BL. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1517–1524. doi: 10.1021/ja0780840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen JQ, Iverson BL. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:2639–2640. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiti F, Dobson CM. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:333–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Kumar S, Udgaonkar JB. Current Science. 2010;98:639–656. [Google Scholar]; b) Jarrett JT, Lansbury PT. Cell. 1993;73:1055–1058. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aggeli A, Nyrkova IA, Bell M, Harding M, Carrick L, McLeish TCB, Semenov A, Boden N. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:11857–11862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191250198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petkova AT, Ishii Y, Balbach JJ, Antzutkin ON, Leapman RD, Delaglio F, Tycko RA. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:16742–16747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262663499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zych A, Iverson BL. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:8898–8909. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Shao H, Nguyen T, Romano NC, Modarelli DA, Parquette JR. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16374–16376. doi: 10.1021/ja906377q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shao H, Parquette JR. Chem Commun. 2010;46:4285–4287. doi: 10.1039/c0cc00701c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Shao H, Gao M, Kim SH, Jaroniec CP, Parquette JR. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:12882–12885. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shao H, Seifert J, Romano NC, Gao M, Helmus JJ, Jaroniec CP, Modarelli DA, Parquette JR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:7688–7691. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molla MR, Ghosh S. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:9849–9859. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Kar H, Molla MR, Ghosh S. Chem Commun. 2013;49:4220–4222. doi: 10.1039/c2cc36536g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Das A, Molla MR, Ghosh S. Chem Sci. 2011;123:963–973. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avinash MB, Govindaraju T. Nanoscale. 2011;3:2536–2543. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00766h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandeeswar M, Avinash MB, Govindaraju T. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:4818–4822. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Talukdar P, Bollot G, Mareda J, Sakai N, Matile S. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6528–6529. doi: 10.1021/ja051260p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Talukdar P, Bollot G, Mareda J, Sakai N, Matile S. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:6525–6532. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Gawroński M, Brzostowska M, Kacprzak K, Kolbon H, Skowronek P. Chirality. 2000;12:263–268. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(2000)12:4<263::AID-CHIR12>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sakai N, Talukdar P, Matile S. Chirality. 2006;18:91–94. doi: 10.1002/chir.20221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhosale S, Matile S. Chirality. 2006;18:849–856. doi: 10.1002/chir.20326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adamcik J, Mezzenga R. Macromolecules. 2012;45:1137–1150. [Google Scholar]

- 23.a) Jiménez JL, Nettleton EJ, Bouchard M, Robinson CV, Dobson CM, Saibil HR. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:9196–9201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142459399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rubin N, Perugia E, Goldschmidt M, Fridkin M, Addadi L. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4602–4603. doi: 10.1021/ja800328y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.a) Gazit E. Prion. 2007;1:32–35. doi: 10.4161/pri.1.1.4095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gazit E. FASEB. 2002;16:77–83. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0442hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Tartaglia GG, Cavalli A, Pellarin R, Caflisch A. Protein Science. 2004;13:1939–1941. doi: 10.1110/ps.04663504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shao H, Parquette JR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:2525–2528. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.