Background: Translocation of the H. pylori oncogenic protein CagA into host cells is dependent on CagF.

Results: CagF interacts with all five domains of CagA.

Conclusion: CagF protects CagA from degradation such that it can be recognized by the type IV secretion system.

Significance: The CagA-CagF interaction is distributed across their molecular surfaces to provide protection to the highly labile effector protein.

Keywords: Cancer, Helicobacter pylori, Protein Secretion, Protein Translocation, Protein-Protein Interactions, CagA, CagF, Type IV Secretion System

Abstract

CagA is a virulence factor that Helicobacter pylori inject into gastric epithelial cells through a type IV secretion system where it can cause gastric adenocarcinoma. Translocation is dependent on the presence of secretion signals found in both the N- and C-terminal domains of CagA and an interaction with the accessory protein CagF. However, the molecular basis of this essential protein-protein interaction is not fully understood. Herein we report, using isothermal titration calorimetry, that CagA forms a 1:1 complex with a monomer of CagF with nm affinity. Peptide arrays and isothermal titration calorimetry both show that CagF binds to all five domains of CagA, each with μm affinity. More specifically, a coiled coil domain and a C-terminal helix within CagF contacts domains II-III and domain IV of CagA, respectively. In vivo complementation assays of H. pylori with a double mutant, L36A/I39A, in the coiled coil region of CagF showed a severe weakening of the CagA-CagF interaction to such an extent that it was nearly undetectable. However, it had no apparent effect on CagA translocation. Deletion of the C-terminal helix of CagF also weakened the interaction with CagA but likewise had no effect on translocation. These results indicate that the CagA-CagF interface is distributed broadly across the molecular surfaces of these two proteins to provide maximal protection of the highly labile effector protein CagA.

Introduction

Type IV secretion systems (T4SS)3 are important virulence factor delivery systems that are used by several Gram-negative bacteria to inject effector molecules directly into host cells where they elicit changes in cell function, immune response, and therefore the local environment, that aid in colonization (1, 2). Helicobacter pylori reside within the human stomach. Most infected individuals remain asymptomatic for life, although in ∼20% of people, H. pylori can cause severe diseases such as peptic ulcers, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma (3–5). Specifically, H. pylori accounts for roughly 750,000 new cases of gastric cancer per year worldwide (6). The presence of a T4SS encoded by ∼30 genes of the cytotoxin-associated gene (cag) pathogenicity island within the H. pylori genome dramatically increases the risk of gastric cancer (4, 7). This system stimulates the expression of interleukin-8 (IL-8) by host cells and translocates the effector molecule CagA, a 120–150-kDa protein depending on the originating strain, into gastric epithelial cells (8, 9). Two structures of a 100-kDa N-terminal fragment of CagA show that this region comprises three domains (10, 11): domain I (residues 1–256), domain II (residues 256–639), and domain III (residues 639–885). The C terminus of CagA comprises two domains: domain IV (residues 885–1055), which encompasses tyrosine phosphorylation motifs (TPMs), and domain V (residues 1055–1247). The domain boundaries are shown in Fig. 1A. Within the host cell, CagA interacts with several proteins such as CSK, CRK, SHP-2, PAR-1, GRB-2, ASPP-2, and E-cadherin in both phosphorylation-dependent and -independent manners and, thus, parasitizes cytoskeletal organization, proliferation, motility, apoptosis, mitogenic gene expression, and cell-cell contact (12–18). This perturbation of cellular function facilitates the colonization of H. pylori within the stomach and indirectly promotes cancer by disruption of host cell signaling pathways.

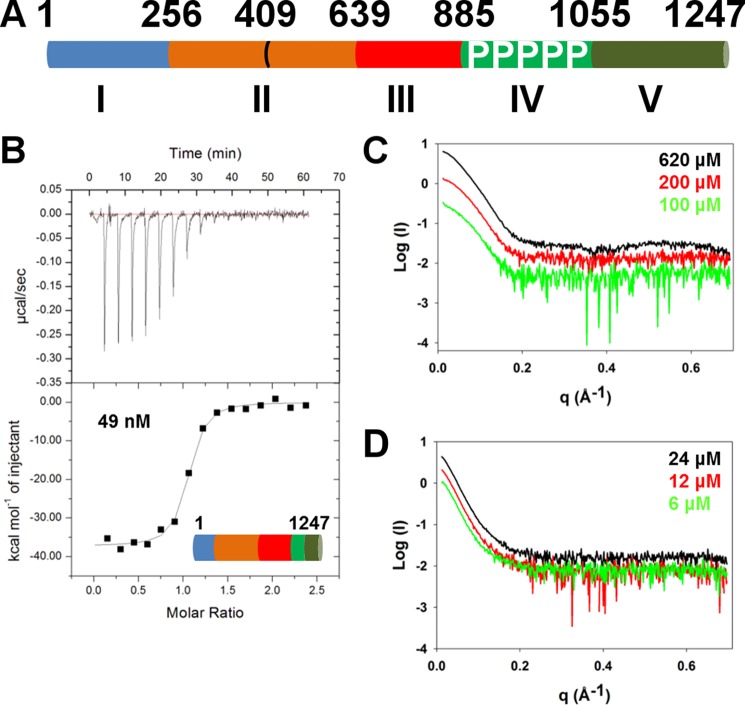

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of the CagA-CagF interaction. A, domain organization of CagA showing the five domains in blue, orange, red, light green, and dark green. Domain boundaries are based upon the structure of Hayashi et al. (10). Several truncations of CagA that form whole or partial domains were constructed. B, isothermal titration calorimetry binding curve of CagFWT titrated against CagAWT. X-ray scattering profiles of CagF (C) and CagA-CagF complex (D) at three different concentrations as indicated are shown.

The interaction with, recognition of, and mechanism for translocation of CagA into human gastric cells via the T4SS is poorly understood. Like other T4SS effector proteins, CagA contains a C-terminal secretion signal. Deletion of the 20 C-terminal residues makes it resistant to interaction, recognition, and translocation by the T4SS (19). Unlike most other T4SS effector molecules, however, CagA also contains a further secretion targeting signal contained within the N-terminal domain, specifically domains I-II (19). Of the 30 genes within the cag pathogenicity island, 18 genes are essential for the translocation of CagA with only 15 of these causing the production of IL-8 (9). CagF, a cytoplasmic protein, is one of only three proteins that is essential for CagA translocation but does not cause IL-8 secretion (20, 21). CagF is thought to act as a chaperone as other T4SSs and type III secretion systems use similar proteins to help stabilize effector protein fold and aid in the targeting of effector molecules to the secretion system (1, 20, 21). In addition, CagF appears to prevent degradation of CagA (20). Specifically, works by Couturier et al. (20) and Pattis et al. (21) both detected an interaction between CagA and CagF. However, CagF was shown to interact either with the stable 100-kDa N-terminal fragment encompassing domains I–III (20) or a region adjacent to the C-terminal secretion signal in domain V (21). Both studies indicated that CagF is not co-translocated with CagA into host cells and that CagF is removed prior to CagA injection.

Here we have comprehensively assessed the interaction of CagF with CagA using isothermal titration calorimetry, peptide array analysis, protein truncations, alanine scanning mutagenesis, small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS), and in vivo complementation assays. Together, these experiments indicate that CagF engages each of the five domains of CagA and that although the CagA-CagF interaction is essential for CagA translocation into host cells CagF interactions with individual CagA domains are dispensable for effector protein translocation. Such redundancy of protection of the highly labile CagA by CagF ensures that full-length CagA can be delivered through the T4SS into host cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification

Genomic DNA from strain 11637 of H. pylori (ATCC) was used as a template for cloning CagA and CagF variants. CagF was cloned with a tobacco etch virus protease site and inserted into the pGEX-5x-2 vector (GE Healthcare). Soluble GST-CagF fusion protein was expressed in BL21(DE3) cells for 18 h at 18 °C with induction using a final concentration of 1 mm IPTG once cells reached an A600 nm of ∼0.6. Cell pellets were disrupted by sonication, and the fusion protein was purified using glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare). Eluted protein was cleaved with tobacco etch virus protease for 16 h at room temperature before removal of cleaved GST using glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads. CagF was concentrated by anion exchange and purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Mono Q and Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare), respectively. All CagF mutants were purified in this fashion.

Full-length CagA (residues 1–1247) was cloned into a modified pRSFDuet vector (EMD Millipore) to produce an N-terminal hexahistidine and C-terminal decahistidine fusion protein. It was co-expressed with GST-CagF in BL21(DE3) cells at 18 °C with induction using a final concentration of 1 mm IPTG once cells reached an A600 nm of ∼0.6 for 18 h. CagA was purified using glutathione-Sepharose 4B followed by nickel affinity chromatography (HisTrap, GE Healthcare). Nickel beads were washed with 1.5 liters of 20 mm Tris, 2 m urea, pH 7.5 to remove GST-CagF. The column was then equilibrated with 10 column volumes of 20 mm Tris, 500 mm sodium chloride, pH 7.5 (Buffer A) and washed with 5 column volumes of Buffer A + 200 mm imidazole (Buffer B) before elution with Buffer A + 400 mm imidazole (Buffer C).

Full-length CagA with an internal tobacco etch virus protease site at position 256 was expressed and purified as full-length CagA. Residues 1–255 were removed by the addition of tobacco etch virus protease and incubation at room temperature for 16 h before being reapplied to the HisTrap column, washing with 5 column volumes of Buffer B to remove residues 1–255, and elution of residues 256–1247 with Buffer C.

Residues 1–885 of CagA were cloned into the original pRSFDuet vector to produce an N-terminal hexahistidine fusion protein, co-expressed with GST-CagF in BL21(DE3) cells, and purified in a similar manner to full-length CagA except after equilibration with Buffer A CagA was eluted with Buffer C. Residues 1–409 and 1055–1247 of CagA were cloned into pRSFDuet to produce N-terminal hexahistidine-tagged proteins. Both were produced through co-expression with GST-CagF in BL21(DE3) at 37 °C for 4 h following induction using a final concentration of 1 mm IPTG once cells reached an A600 nm of ∼0.6. Both proteins were found in inclusion bodies. The inclusion bodies were dissolved in Buffer A + 8 m urea and captured on a HisTrap column. Proteins were refolded directly on the column through a gradient of Buffer A + 8 m urea to 0 m urea. Refolded proteins were eluted with Buffer C; dialyzed against 50 mm Tris, 150 mm sodium chloride, pH 7.5; and further purified by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 column.

Residues 256–885 and 409–885 of CagA were cloned into a pET-21-d vector (EMD Millipore) to produce C-terminal hexahistidine fusion proteins that were expressed in BL21(DE3) cells at 37 °C for 4 h with induction using a final concentration of 1 mm IPTG once cells reached an A600 nm of ∼0.6. The clarified cell extract was applied to a HisTrap column and washed with 5 column volumes of Buffer A + 60 mm imidazole, and protein was eluted with Buffer C and dialyzed overnight against 50 mm Tris, 500 mm sodium chloride, pH 7.5 before further purification by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 column.

Residues 886–1054 of CagA were cloned into a pRSFDuet vector to produce an N-terminal hexahistidine fusion protein that was expressed in C41(DE3) cells (Lucigen) at 37 °C for 4 h with induction using a final concentration of 1 mm IPTG once cells reached an A600 nm of ∼0.6. The protein was purified as described above for residues 256–885 of CagA.

Residues 1–1054 of CagA were clone into the modified pRSFDuet vector (described above) to produce an N-terminal hexahistidine and C-terminal decahistidine fusion protein. It was purified as full-length CagA.

Circular Dichroism

Purified CagA and CagF were dialyzed against 10 mm sodium phosphate, 100 mm sodium chloride, pH 7.5 extensively. Circular dichroism spectra of CagA (1 μm), CagF (3 μm), and CagA-CagF (1 and 3 μm, respectively) were recorded on an Aviv spectrometer Model 62A DS at 25 °C. Additional spectra of CagFWT and CagFS234Stop were recorded on a Jasco J-815 circular dichroism spectrometer. Three scans were recorded and averaged, and buffer contributions were subtracted. Secondary structure analysis was carried out using the SELCON3 (22), CONTIN (23), and CDSSTR (24) algorithms through the DichroWeb server (25).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

All proteins were dialyzed against 50 mm Tris, 200 mm sodium chloride, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.5. ITC experiments were performed using an iTC200 instrument (GE Healthcare). A typical experiment consisted of loading the syringe with CagF at a concentration at least 10-fold higher than CagA, which was placed in the cell. Titrations were performed at 25 °C with 11–17 injections of 2.49–3.49-μl aliquots with at least 210-s intervals between injections. Heats of dilutions were also measured and subtracted from each data set. All data were analyzed using Origin 7.0 software.

Peptide Arrays

Arrays of partially overlapping 15-residue peptides derived from CagA and CagF (CelluSpots) were prepared by INTAVIS Bioanalytical Instruments AG (Köln, Germany). The CagA and CagF arrays were first blocked through incubation for 4 h by immersing the arrays in 50 mm Tris, 150 mm sodium chloride, 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20, 2.5% (w/v) milk powder, pH 8.0 (Blocking Solution). The arrays were then washed three times, once with Blocking Solution and twice with 50 mm Tris, 150 mm sodium chloride, 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20, pH 8.0 (TBST). Purified full-length CagA and GST-CagF were diluted with Blocking Solution to a final concentration of 8 μm and incubated with the arrays overnight at 4 °C. Arrays were washed three times for 5 min with TBST. Binding interactions were identified by chemiluminescence. Full-length CagA was detected using an anti-His antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (EMD Millipore). GST-CagF was probed using a primary antibody against GST raised in mouse (BD Biosciences) and detected using a secondary anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Sigma). The arrays were also incubated with GST and probed with just the antibodies to identify possible nonspecific interactions of GST and the antibodies with the array.

SAXS

The CagA-CagF complex was prepared with CagF in a 2.5-fold excess of CagA and gel-filtered on an S200 size exclusion column equilibrated with 50 mm Tris, 200 mm sodium chloride, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.5. Purified CagF was also gel-filtered in the same buffer. Briefly, scattering signals were recorded on three concentrations of complex (4.1, 2.1, and 1.0 mg ml−1) and CagF (19.8, 6.4, and 3.2 mg ml−1) using a BioSAXS-1000 configured with an FR-E+ SuperbrightTM x-ray generator and PILATUS 100K hybrid pixel array detector (Rigaku). Duplicate scans of 15 or 30 min were collected at 4 °C for buffer and each concentration of the complex. Averaged buffer scans were subtracted from each concentration of averaged sample scans using SAXSLab (Rigaku).

In Vivo Complementation Assays

Gene fragments encoding full-length wild-type CagF or site-directed CagF variants (CagFL36A, CagFI39A, CagFL36AI39A, and CagFS234Stop) were cloned into the chromosomal integration vector pJP99 (21). Resulting plasmids were introduced by natural transformation into a cagF deletion mutant of H. pylori strain P12 (P12ΔcagF), and CagF production of transformants was verified by Western blot using the polyclonal CagF antiserum AK284 (22). Functionality of the complemented strains was assessed using standard AGS cell infection and tyrosine phosphorylation assays as described previously (9). Briefly, AGS cells were infected in 6-well plates with H. pylori strains at a multiplicity of infection of 60 for 4 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Subsequently, infected cells were washed twice with PBS and scraped into PBS, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1 mm PMSF, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin. Cells were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in SDS sample solution, and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitation of CagA from bacterial lysates was performed as described previously (22) with minor modifications. Bacteria (5 × 1010 cells) harvested from agar plates were resuspended in extraction buffer (10 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% (w/v) Nonidet P-40, 1 mm PMSF, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin), and cells were lysed by sonication. Protein bands were evaluated by densitometry using a ChemiDoc XRS+ imager and Image Lab 4.1 software (Bio-Rad).

RESULTS

Characterization of the Wild Type CagA-CagF Interaction

CagA translocation into gastric epithelial cells is dependent on the interaction with the chaperone CagF within the H. pylori cytoplasm that has been described previously (20, 21). To further investigate this interaction, full-length CagA and CagF from H. pylori strain 11637 were expressed and subjected to calorimetric analysis (Fig. 1B). The equilibrium dissociation constant was determined to be 49 nm at pH 7.5 and 25 °C (Table 1). The binding is enthalpically favorable with a ΔHbinding of ∼−38 kcal mol−1 and entropically unfavorable with a ΔSbinding of ∼−95 cal K−1 mol−1. This thermodynamic signature is typical of binding-induced folding, suggesting that regions of the proteins fold upon complexation. The stoichiometry was measured as 1:1, which conflicts with the previous value of one CagA molecule and two CagF molecules as measured by analytical gel filtration and is also complicated by the fact that CagF can dimerize (21). Our measured stoichiometry of 1:1 indicates that a single molecule of CagA could be bound to either one CagF monomer or one CagF dimer depending on the CagF dimerization constant. By conducting SAXS experiments at three different concentrations, we estimated the dimerization constant of CagF to be ∼200 μm. The molecular masses of the CagF species were determined through the programs AutoPOROD and SAXSMoW (26, 27). A molecular mass of 61 kDa was determined for the highest concentration of CagF (620 μm), suggesting that at this concentration CagF is predominately dimeric. At the lowest concentration (100 μm), a molecular mass of 41 kDa, which is close to that expected for a mixture of monomers and dimers in a 2:1 ratio, was observed. At 200 μm, a molecular mass of 53 kDa was measured; this approximates a mixture of monomers and dimers in 1:1 ratio, suggesting that the dimerization constant is on the order of 200 μm, which is 4000-fold weaker than the affinity of the CagA-CagF complex (KD = 49 nm). Our ITC experiments were conducted with CagF in the syringe at similar or higher concentrations; CagF was titrated to concentrations at least 5-fold below this, suggesting that the 1:1 stoichiometry represents one CagA to one CagF monomer. We performed several experiments in which CagF was titrated to 100-fold below the dimerization constant (data not shown) and produced an identical stoichiometry. Although these data show that the stoichiometry is 1:1, the ITC experiments cannot eliminate the possibility of a 2:2 complex in which a dimer of CagA interacts with a dimer of CagF. Thus, we estimated the molecular mass of the CagA-CagF complex using the scattering curves generated from SAXS using three different concentrations of CagA-CagF complex (Fig. 1D). AutoPOROD and SAXSMoW calculated molecular masses of the complex between 174 and 200 kDa in agreement with a stoichiometry of 1:1 (175 kDa) as opposed to 2:2 (350 kDa).

TABLE 1.

Thermodynamic parameters of binding between CagF and CagA variants

All values are means of duplicate runs.

| N | Kd | ΔH | ΔS | TΔS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | kcal mol−1 | cal K−1 mol−1 | kcal mol−1 | ||

| CagAWT | 0.98 ± 0.02 | 49 ± 1 | −38.4 ± 1.1 | −95.2 ± 3.7 | −28.4 |

| CagA1–408 | No binding | ||||

| CagA409–885 | 66,000 ± 2,000 | ||||

| CagA886–1054 | No binding | ||||

| CagA1055–1247 | 47,000 ± 6,000 | ||||

| CagA256–885 | 19,000 ± 2,000 | ||||

| CagA1–885 | 1.16 ± 0.03 | 16,000 ± 500 | −16.4 ± 0.7 | −33.0 ± 2.2 | −9.8 |

| CagA1–1054 | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 4,600 ± 430 | −7.3 ± 0.7 | +0.2 ± 2.4 | +0.1 |

| CagA256–1247 | 1.01 ± 0.00 | 261 ± 41 | −36.9 ± 0.1 | −93.7 ± 0.1 | −27.9 |

Mapping of the CagF Binding Site on CagA

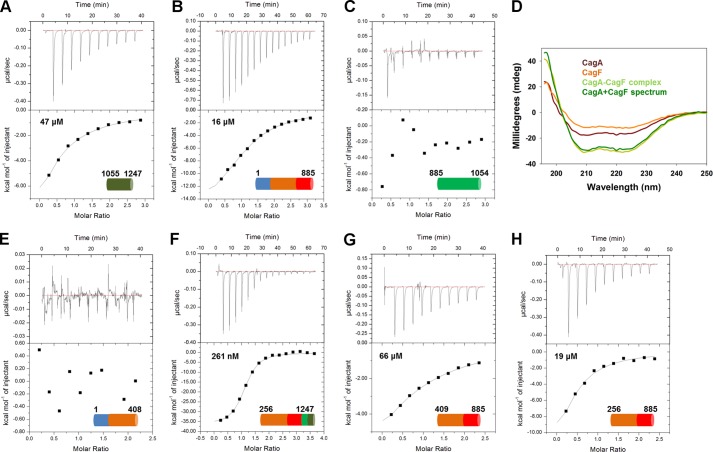

To establish whether CagF binds domains I–III or domain V (Fig. 1A), two CagA constructs were made, CagA1–885 and CagA1055–1247 (20, 21). We observed an interaction ∼1000-fold weaker compared with wild type (KD ∼ 47 μm) when CagF was titrated into CagA1055–1247 (Fig. 2A). CagA1–885, which encompasses domains I–III, also showed a weak interaction (KD ∼ 16 μm) ∼320-fold weaker than wild type (Fig. 2B). As the binding curve is more sigmoidal, the thermodynamic parameters are more accurate, allowing a comparison with full-length CagA. All thermodynamic data are shown in Table 1. This revealed that although the interaction is still enthalpically favorable and entropically unfavorable the lack of domains IV-V results in a smaller entropic penalty for binding, suggesting that the C terminus of CagA is disordered and may fold upon binding of CagF. The C-terminal domain of CagA is likely intrinsically disordered. (i) The 1H NMR spectrum of recombinant CagA C-terminal domain from strain 26995 shows a weak dispersion of peaks centered around 8 ppm, which is typical of intrinsically disordered proteins (10). (ii) A circular dichroism spectrum of this domain shows one that is typical of a disordered protein (10). (iii) Residues 885–1005, comprising just the TPMs of CagA, resolved only 14 residues of CagA when crystallized in complex with MARK2 (28). (iv) Several intrinsic disorder prediction software programs suggest that regions of the C terminus are disordered. Titration of CagF into domain IV of CagA (residues 885–1079; strain 11637 numbering) showed no observable binding except for CagF dilution (Fig. 2C). As CagF binds sites flanking the TPM domain, CagF may induce folding in the TPM domain through restriction. We used circular dichroism to observe any changes in secondary structure upon CagA-CagF interaction. CD spectra of 1 μm full-length CagA, 3 μm CagF, and 1 μm CagA in the presence of 3 μm CagF were recorded (Fig. 2D). The spectrum of the complex compared with that of the sum of the individual protein spectra shows very little change in secondary structure, suggesting that substantial binding-induced folding for a large proportion of CagA does not occur, although local folding events are still possible.

FIGURE 2.

CagF binds several domains of CagA. Isothermal titration calorimetry binding curves of CagFWT titrated against CagA1055–1247 (A), CagA1–885 (B), and CagA885–1054 (C) are shown. D, circular dichroism spectra of CagF (orange), CagA (brown), and CagA-CagF complex (light green) and the summation of the CagF and CagA spectra (dark green). Isothermal titration calorimetry binding curves of CagFWT titrated against CagA1–409 (E), CagA256–1247 (F), CagA409–885 (G), and CagA256–885 (H) are shown.

Several truncations of CagA were expressed to further characterize CagF binding to domains I–III of CagA (CagA1–409, CagA409–885, and CagA256–885) to identify which domain is responsible for binding. The boundaries of these CagA constructs (Fig. 1A) are based upon truncations identified from a CagA expression library screen as well as the domain boundaries from the two solved structures of CagA (10, 11, 29). CagA1–408, comprising domain I and part of domain II, did not bind when CagF was titrated into the cell (Fig. 2E). To eliminate the possibility of a weak interaction with domain I, we titrated CagF into CagA256–1247, which lacks domain I. We observed a ∼5-fold reduction in affinity (KD ∼260 nm) with thermodynamics nearly identical to full-length CagA (Fig. 2F), demonstrating that CagF does recognize domain I albeit very weakly. Titration of CagF into CagA409–885, which represents domain III and part of domain II, showed an interaction (KD ∼ 67 μm) ∼1300-fold weaker than full-length CagA (Fig. 2G). Extending this construct to include all of domain II (CagA256–885), we observed a 2.5-fold increase in affinity (KD ∼19 μm) when compared with CagA409–885 and only slightly weaker than CagA1–885 (Fig. 2H). These data demonstrate that CagF binds domain V of CagA as well as all domains I–III.

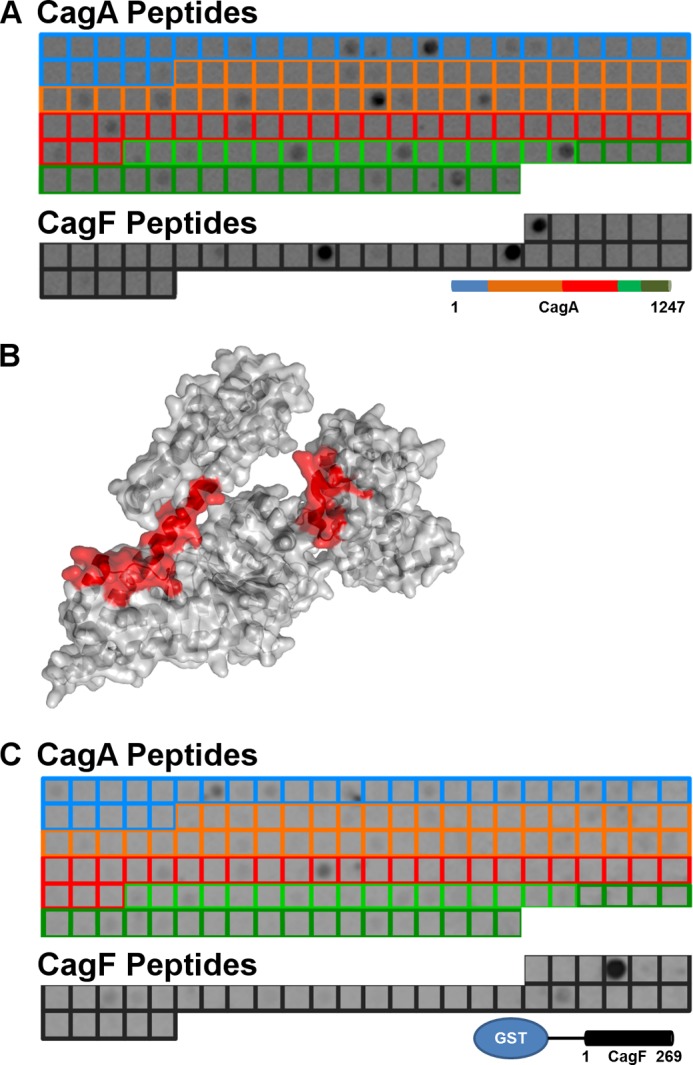

Identification of CagA and CagF Binding Regions

An array consisting of partly overlapping peptides derived from CagA and CagF was designed to identify smaller regions of CagA and CagF that mediate the interaction between the proteins. Screening of the array was initially performed using the GST-CagF fusion protein (Fig. 3A and supplemental File 1). Several strongly binding peptides were identified. Three peptides from domains I–III (127–141, 541–555, and 667–681) were mapped onto the solved structure of domains I–III of CagA to reveal that all three peptides are surface-exposed and are on one face of the protein (Fig. 3B), forming a possible binding interface. Two other strongly binding peptides were also identified: one from domain V (residues 1214–1228) and one from domain IV (residues 1034–1048). Nine more weakly binding peptides encompassing CagA were also identified. Interestingly, one of these CagA peptides, residues 1117–1131 (strain 11637 numbering), is located within the previously identified CagF binding site residues 1080–1184 (strain 11637 numbering). CagF-derived peptides were also found to interact with GST-CagF, specifically residues 1–15, 116–130, and 163–177. These peptides potentially form the CagF dimerization site.

FIGURE 3.

Interaction of recombinant CagA and CagF on CagA and CagF 15-mer peptide arrays. A, a peptide array consisting of CagA (blue, orange, red, light green, and dark green boxes denoting domains I, II, III, IV, and V respectively) and CagF (black boxes) peptides was probed for binding with GST-CagF and developed with GST antibody and HRP-anti-mouse IgG conjugate. B, the three most intense CagA peptides that bind GST-CagF (red) are mapped onto the structure of domains I–III of CagA (Protein Data Bank code 4DVZ). C, a peptide array consisting of CagA and CagF (same color schemes as described in A) was probed for binding with full-length CagA and developed with HRP-anti-His conjugate.

Identification of CagA binding sites on CagF has not been conducted previously. Screening the array with full-length CagA showed that it interacts with several peptides of CagF (Fig. 3C and supplemental File 1). Specifically, we observed a strong interaction with residues 26–40 and weaker interactions with residues 73–87 and 181–195 (Fig. 3C and supplemental File 1). The interaction of CagA with residues 26–40 of CagF was investigated further.

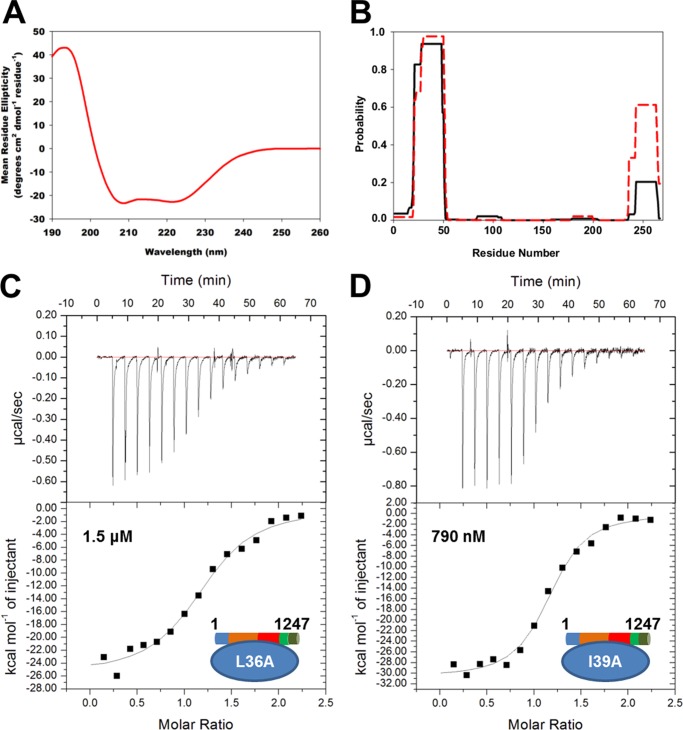

CagF Contains a Coiled Coil Region That Is Important for CagA Binding

Secondary structure and disorder estimation programs predict CagF to be predominately α-helical, containing a small amount of β-strands and no large regions of disorder. Indeed, CagF was found to be approximately ∼55% α-helical, ∼5% β-sheet, and 40% turns and unordered as determined by circular dichroism (Fig. 4A). COILS, a program that predicts coiled coil conformations, predicted the presence of two coiled coil domains (30): residues 21–51 and 243–263 (Fig. 4B). However, as CagF is an acidic protein (theoretical pI ∼4.5), a 2.5-fold weighting of positions a and d of the helix was applied, revealing that the second coiled coil is most likely a highly charged false positive. Alanine scanning mutagenesis of the CagF coiled coil (residues 30–40) was conducted as this region was shown to bind CagA by our peptide array to identify possible binding residues to CagA through isothermal titration calorimetry (Fig. 4, C and D, and Table 2). We found that only F30A displays thermodynamics parameters nearly identical to wild type CagF. The remaining alanine mutants each fall into two categories: 1) the affinity is similar to wild type, but the thermodynamics differ (E31A, L32A, K33A, E34A, E35A, D37A, and F38A), or 2) the affinity is substantially weaker (L36A, I39A, and E40A). The CagA binding is localized at the end of the region that was mutated. Therefore, we extended our mutagenesis study to cover residues 41–44 and to represent another turn of the coiled coil. These mutants were found to show affinities similar to wild type CagF although with only slightly different thermodynamic signatures (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

CagF uses a coiled coil domain to interact with CagA. A, circular dichroism spectrum of CagF. B, graphical representation of the output from COILS using the sequence of CagF and a 21-residue window with (black line) or without (red line) a 2.5-fold weighting on the a and d positions of the coiled coil. Isothermal titration calorimetry binding curves of the CagAWT-CagFL36A (C) and CagAWT-CagFI39A (D) interactions are shown.

TABLE 2.

Thermodynamic parameters of binding between CagAWT and CagF variants

All values are means of duplicate runs.

| CagF mutation | N | Kd | ΔH | ΔS | TΔS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | kcal mol−1 | cal K−1 mol−1 | kcal mol−1 | ||

| WT | 0.98 ± 0.02 | 49 ± 1 | −38.4 ± 1.1 | −95.2 ± 3.7 | −28.4 |

| F30A | 0.92 ± 0.02 | 35 ± 4 | −37.4 ± 0.6 | −91.2 ± 1.5 | −27.2 |

| E31A | 1.11 ± 0.01 | 43 ± 12 | −28.1 ± 1.5 | −60.5 ± 5.7 | −18.0 |

| L32A | 1.11 ± 0.02 | 105 ± 12 | −32.6 ± 0.3 | −77.2 ± 0.5 | −23.0 |

| K33A | 1.10 ± 0.01 | 61 ± 1 | −33.2 ± 0.1 | −78.4 ± 0.3 | −23.4 |

| E34A | 1.09 ± 0.00 | 61 ± 4 | −32.6 ± 1.4 | −76.4 ± 4.9 | −22.8 |

| E35A | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 92 ± 30 | −34.0 ± 1.4 | −81.5 ± 5.2 | −24.3 |

| L36A | 1.22 ± 0.03 | 1500 ± 16 | −25.0 ± 0.6 | −57.3 ± 2.1 | −17.1 |

| D37A | 0.98 ± 0.02 | 136 ± 20 | −34.0 ± 1.6 | −82.6 ± 5.7 | −24.6 |

| F38A | 0.95 ± 0.00 | 107 ± 18 | −30.5 ± 0.4 | −70.3 ± 1.6 | −21.0 |

| I39A | 1.16 ± 0.02 | 793 ± 84 | −31.0 ± 0.2 | −75.7 ± 0.7 | −22.6 |

| E40A | 1.05 ± 0.04 | 384 + 21 | −31.1 ± 0.4 | −74.9 ± 1.1 | −22.3 |

The Coiled Coil Region of CagF Binds Domains II-III of CagA

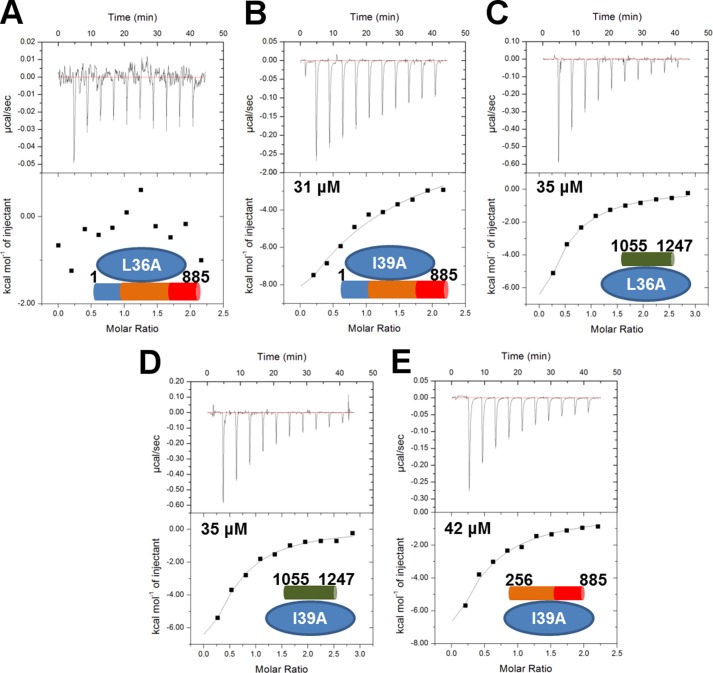

CagA binds to the coiled coil region of CagF, specifically through CagF residues Leu-36, Ile-39, and Glu-40. However, it is unknown which residues or domains they contact on CagA. The two mutants of CagF that produced the largest change in affinity, L36A and I39A, were used to identify whether the coiled coil domain of CagF binds CagA1–885 (domains I–III) or CagA1055–1247 (domain V) through isothermal titration calorimetry and comparison with wild type CagF. Titrating CagFL36A and CagFI39A into CagA1–885 showed no binding and a 2-fold weaker affinity compared with CagFWT (KD ∼31 μm), respectively (Fig. 5, A and B). Titrations of the two mutants into CagA1055–1247 revealed affinities of ∼35 μm, similar to the wild type CagF interaction (Fig. 5, C and D), indicating that the coiled coil of CagF interacts with the domains I–III of CagA and not domain V at the C terminus. We titrated CagFI39A against CagA256–885 to determine whether this region contacted domain I of CagA. We found that CagFI39A binds with an affinity of ∼42 μm, which is again weaker than the wild type interaction of 19 μm, showing that the coiled coil interacts with domains II-III of CagA (Fig. 5E).

FIGURE 5.

The coiled coil domain of CagF interacts with domains II-III of CagA. Isothermal titration calorimetry binding curves of the CagA1–885-CagFL36A (A), CagA1–885-CagFI39A (B), CagA1055–1247-CagFL36A (C), CagA1055–1247-CagFI39A (D), and CagA256–885-CagFI39A (E) interactions are shown.

The Coiled Coil of CagF Is Not Required for CagA Translocation

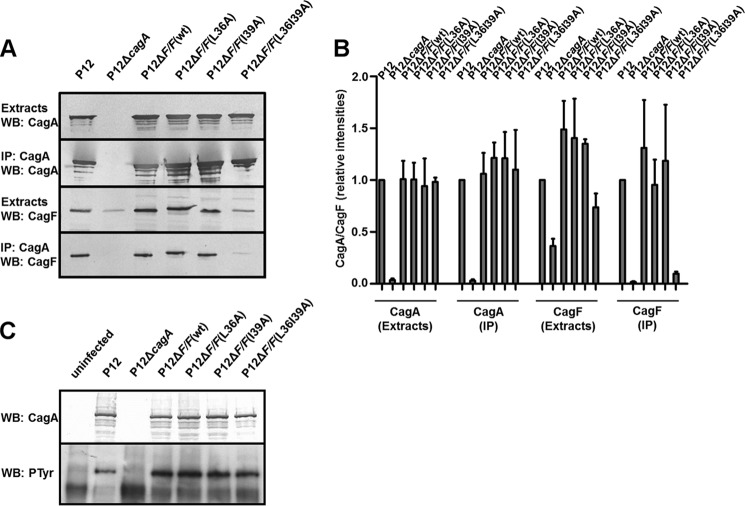

The translocation signal regions of CagA are located within the N-terminal 351 residues (domain I and part of domain II) and in the C-terminal 20 residues of CagA in domain V. The latter lies close to one of the identified CagF binding sites on CagA (residues 1080–1184; strain 11637 numbering). Without CagF, these signals are not sufficient for translocation; the formation of the CagA-CagF complex contributes to the translocation signal and allows secretion of CagA. We have determined that the CagF coiled coil domain does not interact with either domain containing a secretion signal but instead with domains II-III of CagA. It is not known, however, whether this new CagF binding site on CagA that is distal from both translocation signal regions contributes to secretion. We investigated this through complementation of a ΔcagF H. pylori strain P12 with constructs expressing CagF, CagFL36A, CagFI39A, or CagFL36AI39A (Fig. 6A). Immunoprecipitation (IP) of CagA from H. pylori cell extracts and Western blotting of CagF showed that the L36A and I39A mutants were still immunoprecipitated with CagA. As the ITC experiments described above showed that the affinity is tighter than 2 μm, the observation that these mutants still interacted with CagA is not surprising. Although the double CagF mutant CagFL36AI39A was expressed at levels ∼25% lower compared with wild type and the individual mutations, densitometric quantification of the Western blotting for CagF of CagA immunoprecipitates showed that the double mutant interacts very weakly with CagA in the range of ∼10% of the wild type interaction (Fig. 6B). We were unable to characterize this interaction by ITC as the recombinant protein was not expressed. CagA translocation was followed for these mutants through Western blotting for phosphorylated CagA, which only occurs after translocation into host cells. None of the CagF mutants were found to be defective for CagA translocation (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Functional characterization of coiled coil CagF variants. A, whole-cell lysates of the indicated H. pylori strains were subjected to CagA immunoprecipitation. Extracts and IP fractions were analyzed by Western blot for CagA and CagF. B, densitometric quantification of CagA and CagF in IP experiments. Data are shown as means ± S.D. (error bars) for immunoblots obtained from at least three independent IP experiments. C, AGS cells were infected for 4 h with the indicated strains or left uninfected. Infection lysates were analyzed by Western blot (WB) with CagA- and phosphotyrosine (PTyr)-specific antibodies.

The C-terminal Helix of CagF Is Also Not Required for CagA Translocation

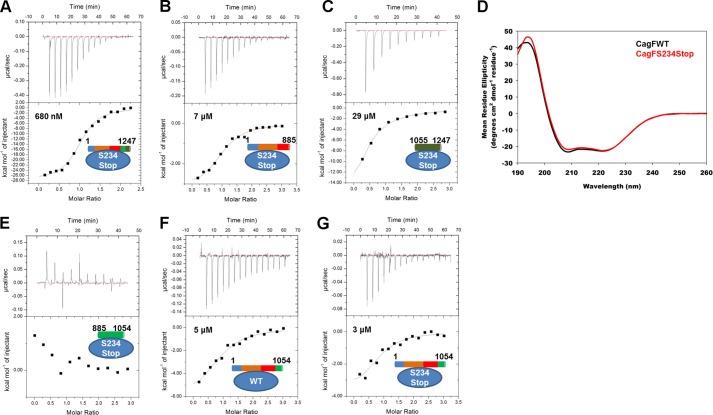

The 30 C-terminal residues of CagF are predicted to form an α-helix. This region shows a high sequence similarity to the secretion peptide of CagA and several other T4SS effector proteins from other organisms (19). Indeed, it was shown that the CagA secretion peptide could be swapped with secretion peptides of other effector proteins although not with that of the putative secretion peptide of CagF (19). Our peptide array data indicated that this region is also not important for CagA binding. However, we speculated that the helix swapping experiment failed because of the lack of two unique secretion signals, one from CagF and one from CagA. To this end, a stop codon was introduced (CagFS234Stop) to remove this helix, and binding to full-length CagA was evaluated by ITC. We observed a 14-fold decrease in affinity (680 nm) when compared with wild type CagF (Fig. 7A) and that the thermodynamic signature is still enthalpically favorable (−27 kcal mol−1) and entropically unfavorable (−63 cal K−1 mol−1). We attempted to identify whether this helix bound CagA1–885 or CagA1055–1247 through ITC. We observed that CagFS234Stop interacted with a 2-fold increase in affinity with both fragments of CagA (Fig. 7, B and C, and Table 3). Although the interaction is weak between CagFS234Stop and CagA1055–1247, as seen with wild type CagF, the exact value of the change in enthalpy could not be determined. However, we observed that it is more entropically favorable with CagFS234Stop than with CagFWT. The loss of the CagF C-terminal helix results in an interaction with CagA1–885 that is now both enthalpically and entropically favorable (Table 3). These data suggest that this helix is disordered in the unbound state and that it folds upon binding to CagA. We analyzed the circular dichroism spectra of CagFWT and CagFS234Stop for secondary structure using the DichroWeb server (25). We observed a decrease in the percentage of turns and disorder and an increase in the percentage of helices when the last 35 residues of CagF were deleted (Fig. 7D), strongly suggesting that this helix is in fact disordered in the unbound state. The reason this helix causes CagFWT to bind full-length CagA with higher affinity than CagFS234Stop but with weaker affinity when binding individual domains of CagA could be that only the folded helix interacts with domain IV of CagA. We first tested the interaction of domain IV of CagA directly with CagFS234Stop, which like CagFWT does not interact and only shows heats due to dilution (Fig. 7E). We then tested binding of both CagFWT and CagFS234Stop to CagA1–1054, which includes domain IV. We observed that CagFWT binds CagA1–1054 ∼3.5-fold more tightly compared with CagA1–885 (Fig. 7F). The thermodynamic signature remains enthalpically favorable, although the interaction is now entropically neutral. We found that when CagFS234Stop was titrated into CagA1–1054 the interaction was of slightly higher affinity when compared with CagA1–885 with the increase in affinity originating from a small increase in enthalpy (Fig. 7G). These data show that binding of CagF to domains I–III of CagA results in folding of the CagF C-terminal helix, which then interacts with domain IV of CagA.

FIGURE 7.

The C-terminal helix of CagF folds upon binding CagA and subsequently interacts with domain IV of CagA. Isothermal titration calorimetry binding curves of the CagAWT-CagFS234Stop (A), CagA1–885-CagFS234Stop (B), and CagA1055–1247-CagFS234Stop (C) interactions are shown. D, comparison of the circular dichroism spectra of CagFWT (black line) and CagFS234Stop (red line) showing the latter to be more helical. Isothermal titration calorimetry binding curves of the CagA885–1054-CagFS234Stop (E), CagA1–1054-CagFWT (F), and CagA1–1054-CagFS234Stop (G) interactions are shown.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the thermodynamic parameters of binding between CagF and CagFS234Stop and CagA variants

All values are means of duplicate runs.

| N | Kd | ΔH | ΔS | TΔS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | kcal mol−1 | cal K−1 mol−1 | kcal mol−1 | ||

| CagAWT-CagFWT | 0.98 ± 0.02 | 49 ± 1 | −38.4 ± 1.1 | −95.2 ± 3.7 | −28.4 |

| CagAWT-CagFS234Stop | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 684 ± 51 | −27.0 ± 0.7 | −62.5 ± 2.5 | −18.6 |

| CagA1–885-CagFWT | 1.16 ± 0.03 | 16,000 ± 500 | −16.4 ± 0.7 | −33.0 ± 2.2 | −10.5 |

| CagA1–885-CagFS234Stop | 0.99 ± 0.02 | 7,000 ± 1,600 | −3.5 ± 0.2 | +12.4 ± 0.7 | +3.7 |

| CagA1–1054-CagFWT | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 4,600 ± 430 | −7.3 ± 0.7 | +0.2 ± 2.4 | +0.1 |

| CagA1–1054-CagFS234Stop | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 2,900 ± 340 | −3.9 ± 0.1 | +12.3 ± 0.1 | +3.7 |

| CagA1055–1247-CagFWT | 47,000 ± 6,000 | ||||

| CagA1055–1247-CagFS234Stop | 25,000 ± 3,600 |

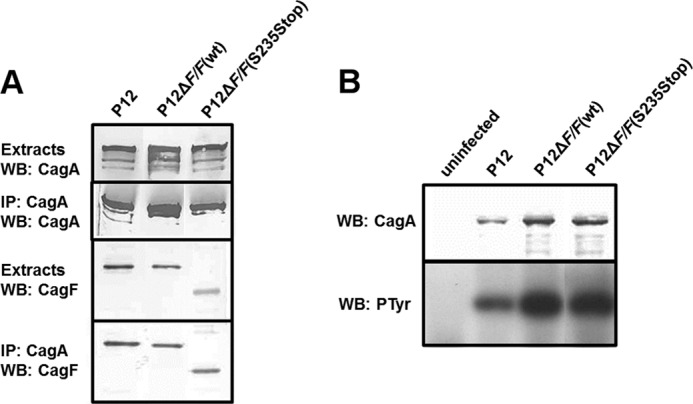

The importance of this helix was assessed in vivo through complementation of a ΔcagF H. pylori strain P12 with constructs expressing CagF or CagFS234Stop (Fig. 8A). Immunoprecipitation of CagA and Western blotting of CagF confirmed our the result from ITC experiments that this helix is dispensable for CagA binding. We also observed that deletion of this helix likewise had no effect on CagA translocation (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Functional characterization of the C-terminal helix deletion of CagF. A, whole-cell lysates of the indicated H. pylori strains were subjected to CagA immunoprecipitation. Extracts and IP fractions were analyzed by Western blot for CagA and CagF. B, AGS cells were infected for 4 h with the indicated strains or left uninfected. Infection lysates were analyzed by Western blot (WB) with CagA- and phosphotyrosine (PTyr)-specific antibodies.

DISCUSSION

In diverse bacteria, T4SSs are not only used for translocation of effector molecules but also for conjugation and DNA release (1, 2). Most substrates are translocated through the system by signal sequences carried either by the effector proteins themselves or by relaxase proteins used in DNA transfer (1, 31). These secretion signals are located near the C termini and composed predominantly of positively charged and/or hydrophobic residues. Several of these systems require in addition to the secretion signal an accessory protein (32). Such accessory proteins mainly act as chaperones to help stabilize the fold and prevent aggregation. They may also serve to inhibit premature activation of the effector protein. For instance, VirE1, an accessory protein of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens T4SS, is a small (7-kDa), acidic, α-helical protein similar to most accessory proteins within both the type III and IV secretion systems (33). VirE1 interacts with the effector protein VirE2 to prevent it from prematurely binding single-stranded DNA within the cytoplasm of A. tumefaciens (33). VirE1 is also hypothesized to stop oligomerization of the termini of VirE2 and to present the C-terminal secretion peptide of VirE2 to the T4SS (34, 35).

CagF, the accessory protein of the H. pylori T4SS, is markedly different from other T4SS accessory proteins. CagF is much larger (32 kDa) than the average accessory protein (5–15 kDa). Although the protein is acidic (theoretical pI ∼4.5), CagF has an unusual amino acid composition: it is severely depleted in alanine and glycine residues with only ∼3% of the protein being composed of them. It is also unusual in that ∼13% of the protein consists of phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan, making it highly hydrophobic, although the protein remains soluble and well behaved in solution. As negative surface charges strongly correlate with solubility (36), the low pI of CagF may help keep this hydrophobic protein soluble. Several of these accessory proteins have been shown to serve as chaperones, helping to fold the effector molecules. The high percentage of hydrophobic residues could aid in the folding of CagA (20, 21). Indeed, our ITC experiments do show a large entropic penalty, suggesting binding-induced folding. It is unlikely that CagF functions as a classical chaperone to extensively fold its target protein for the following reasons. 1) Comparison of the circular dichroism spectra of the individual proteins and the complex shows little or no change in the secondary structure. 2) Full-length CagA and individual domains including the C-terminal domain can be expressed recombinantly without CagF (10, 11, 28, 29). 3) Other chaperone accessory proteins do not display these extremes in amino acid compositions. We speculate that the function of CagF is 2-fold: it (i) prevents degradation of CagA and (ii) keeps the secretion peptide free.

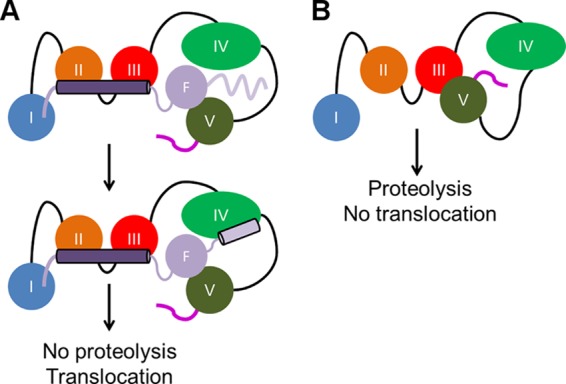

CagF is not translocated with CagA into the host cell. Once translocated, CagA has a relatively short half-life (∼3 h) and is degraded to a 100-kDa N-terminal fragment and a 35-kDa C-terminal fragment (37–39). These same species are also detected when CagA is overexpressed in Escherichia coli (20). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-mass spectrometry of H. pylori tryptic peptides reveals that these species are also observed although in much lower amounts due to the presence of CagF (37). Indeed, we found that by co-expressing CagA in the presence of CagF the yield of full-length CagA is increased, whereas the 100- and 35-kDa breakdown products are suppressed (data not shown). All experiments conducted with full-length CagA were performed shortly after separating CagF from CagA as it was observed to break down to these fragments quite readily. Our ITC and peptide array data show that CagF contacts all five domains of CagA. We identified that CagF contains a coiled coil domain in the N terminus. Coiled coils are elongated structural motifs that can oligomerize. CagF itself can dimerize, suggesting that this region could form the basis of dimerization, although our peptide array data show no interaction of GST-CagF with any peptides corresponding to the coiled coil. We determined that the coiled coil of CagF interacts with domains II-III of CagA through alanine scanning mutagenesis. CagA itself contains several coiled coils as shown through the COILS server and the two crystal structures within domain III. A peptide of CagA residues 667–681 that forms one of the coiled coils was shown to interact with GST-CagF in our peptide arrays. We therefore assume that CagF associates with CagA through heterodimerization of the coiled coils. This would position CagF such that the 25 N-terminal residues preceding the coiled coil could potentially interact with domain I of CagA. The 210 C-terminal residues following the coiled coil would be projected toward domains IV and V. Our ITC and CD data show that the binding of CagF to CagA1–885 induces folding of the last 35 residues of CagF, which then interacts with domain IV of CagA. Overall the interaction between CagFWT and CagA1–1054 is entropically neutral, clearly showing that the large entropic penalty associated with the CagA-CagF interaction arises from binding domain V of CagA through CagF residues located in between the coiled coil and the C-terminal helix. Thus, through CagF binding to all domains of CagA, it stabilizes and protects CagA from proteolysis and degradation (Fig. 9A).

FIGURE 9.

Mechanism by which CagF causes CagA translocation. A, CagF (F) uses the coiled coil (dark purple cylinder) to bind domains II-III and makes further contacts to domains I and V of CagA. Binding triggers folding of the CagF C-terminal helix (light purple line and cylinder), which contacts domain IV. B, in the absence of CagF, domain V self-associates with domain III, burying the C-terminal secretion peptide (magenta line), leading to no translocation of CagA into host gastric epithelial cells and extensive proteolysis. Overall, CagF prevents self-association of domain V to domain III, exposing the C-terminal secretion peptide.

Deletion of the 20 C-terminal residues renders CagA translocation-incompetent, identical to effector proteins of other T4SS (1, 19). Deletion of N-terminal residues, specifically Δ351, also causes translocation of CagA to fail (19), which is unique for T4SS effector proteins. However, as translocation is monitored by tyrosine phosphorylation of CagA, which only occurs within the host cell, it does not reveal where CagA translocation stalls within the T4SS. Deletion of the N-terminal 351 residues of CagA may cause translocation to fail at the plasma membrane barrier of the host cell as the binding site for β1 integrin is located within these residues (11). Residues 998–1038 of CagA (strain 2695 numbering) have been shown to specifically interact with residues 782–820 of its N terminus (10, 40) through hydrophobic interactions. This intramolecular interaction is important as once inside the host cell it potentiates the effect of the C-terminal domain. However, inside the cytoplasm of H. pylori, this interaction could prevent CagA translocation if the secretion peptide is inaccessible. Indeed, as CagF contacts all domains of CagA, it is tempting to speculate that CagF disrupts the intramolecular interaction of CagA through its high percentage of hydrophobic residues, freeing the secretion peptide to engage with the T4SS. This is similar to the function of VirE1 where it prevents oligomerization and aggregation of the effector protein and keeps the secretion peptide exposed, although in this case, it is to prevent the C terminus from contacting the N terminus.

Through our peptide array and ITC data, we identified the coiled coil domain and the C-terminal helix of CagF to be important for interacting with domains II-III and the TPMs of CagA, respectively. By alanine scanning mutagenesis of the coiled coil, which identified two mutations (L36A and I39A), and deletion of the C-terminal helix, we showed a ∼15–30-fold weakening of the affinity compared with wild type. When we introduced these CagF mutations individually in H. pylori, we found that they still bound CagA but had no effect on translocation. Furthermore, we found that the double mutation of the coiled coil (L36A/I39A) results in a CagA-CagF interaction that is nearly undetectable in H. pylori but overall still had no significant effect on translocation. However, we cannot rule out that these mutations affect the efficiency of translocation through the T4SS by monitoring CagA phosphorylation. We hypothesize that the reason why mutation of the coiled coil or deletion of the C terminus had no effect on translocation is that CagF is still able to interact with CagA albeit weakly and disrupt the intramolecular interaction, thus keeping the secretion peptide free for it to be recognized by the T4SS and translocate CagA. We present a model in which without CagF the C terminus of CagA (domain V) associates with its N terminus (domain III), blocking translocation through restriction of the secretion peptide and thereby promoting proteolysis (Fig. 9B). The coiled coil of CagF binds domains II-III of CagA, triggering folding of the C-terminal helix, which binds domain IV, whereas the rest of CagF binds domain V of CagA, disrupting the self-association between domains III and V. This exposes the secretion peptide and protects CagA from degradation (Fig. 9A).

Acknowledgments

We thank Pierre Le Magueres and Angela Criswell from the Life Sciences Department at Rigaku Americas Corp. for collecting and analyzing the SAXS data and Maura O'Neill from the School of Pharmacy, University of Maryland, for help with CD acquisition.

This work was supported in part by an Alexander von Humboldt Foundation experienced researcher fellowship (to E. J. S.) as well as a Fulbright scholarship and International Sephardic Education Foundation fellowship (to T. H. R.).

This article contains supplemental File 1.

- T4SS

- type IV secretion system

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- TPM

- tyrosine phosphorylation motif

- SAXS

- small angle x-ray scattering

- IPTG

- isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside

- IP

- immunoprecipitation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alvarez-Martinez C. E., Christie P. J. (2009) Biological diversity of prokaryotic type IV secretion systems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73, 775–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Voth D. E., Broederdorf L. J., Graham J. G. (2012) Bacterial type IV secretion systems: versatile virulence machines. Future Microbiol. 7, 241–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blaser M. J., Perez-Perez G. I., Kleanthous H., Cover T. L., Peek R. M., Chyou P. H., Stemmermann G. N., Nomura A. (1995) Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res. 55, 2111–2115 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parsonnet J., Friedman G. D., Orentreich N., Vogelman H. (1997) Risk for gastric cancer in people with CagA positive or CagA negative Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut 40, 297–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Israel D. A., Salama N., Arnold C. N., Moss S. F., Ando T., Wirth H. P., Tham K. T., Camorlinga M., Blaser M. J., Falkow S., Peek R. M., Jr. (2001) Helicobacter pylori strain-specific differences in genetic content, identified by microarray, influence host inflammatory responses. J. Clin. Investig. 107, 611–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jemal A., Bray F., Center M. M., Ferlay J., Ward E., Forman D. (2011) Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 61, 69–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Censini S., Lange C., Xiang Z., Crabtree J. E., Ghiara P., Borodovsky M., Rappuoli R., Covacci A. (1996) cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 14648–14653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Odenbreit S., Püls J., Sedlmaier B., Gerland E., Fischer W., Haas R. (2000) Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science 287, 1497–1500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fischer W., Püls J., Buhrdorf R., Gebert B., Odenbreit S., Haas R. (2001) Systematic mutagenesis of the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island: essential genes for CagA translocation in host cells and induction of interleukin-8. Mol. Microbiol. 42, 1337–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hayashi T., Senda M., Morohashi H., Higashi H., Horio M., Kashiba Y., Nagase L., Sasaya D., Shimizu T., Venugopalan N., Kumeta H., Noda N. N., Inagaki F., Senda T., Hatakeyama M. (2012) Tertiary structure-function analysis reveals the pathogenic signaling potentiation mechanism of Helicobacter pylori oncogenic effector CagA. Cell Host Microbe 12, 20–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaplan-Türköz B., Jiménez-Soto L. F., Dian C., Ertl C., Remaut H., Louche A., Tosi T., Haas R., Terradot L. (2012) Structural insights into Helicobacter pylori oncoprotein CagA interaction with β1 integrin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 14640–14645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tegtmeyer N., Wessler S., Backert S. (2011) Role of the cag-pathogenicity island encoded type IV secretion system in Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis. FEBS J. 278, 1190–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Murata-Kamiya N., Kurashima Y., Teishikata Y., Yamahashi Y., Saito Y., Higashi H., Aburatani H., Akiyama T., Peek R. M., Jr., Azuma T., Hatakeyama M. (2007) Helicobacter pylori CagA interacts with E-cadherin and deregulates the β-catenin signal that promotes intestinal transdifferentiation in gastric epithelial cells. Oncogene 26, 4617–4626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Segal E. D., Cha J., Lo J., Falkow S., Tompkins L. S. (1999) Altered states: involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 14559–14564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tsutsumi R., Higashi H., Higuchi M., Okada M., Hatakeyama M. (2003) Attenuation of Helicobacter pylori CagA·SHP-2 signaling by interaction between CagA and C-terminal Src kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 3664–3670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lu H. S., Saito Y., Umeda M., Murata-Kamiya N., Zhang H. M., Higashi H., Hatakeyama M. (2008) Structural and functional diversity in the PAR1b/MARK2-binding region of Helicobacter pylori CagA. Cancer Sci. 99, 2004–2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mimuro H., Suzuki T., Tanaka J., Asahi M., Haas R., Sasakawa C. (2002) Grb2 is a key mediator of Helicobacter pylori CagA protein activities. Mol. Cell 10, 745–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buti L., Spooner E., Van der Veen A. G., Rappuoli R., Covacci A., Ploegh H. L. (2011) Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) subverts the apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53 (ASPP2) tumor suppressor pathway of the host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 9238–9243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hohlfeld S., Pattis I., Püls J., Plano G. V., Haas R., Fischer W. (2006) A C-terminal translocation signal is necessary, but not sufficient for type IV secretion of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Mol. Microbiol. 59, 1624–1637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Couturier M. R., Tasca E., Montecucco C., Stein M. (2006) Interaction with CagF is required for translocation of CagA into the host via the Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion system. Infect. Immun. 74, 273–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pattis I., Weiss E., Laugks R., Haas R., Fischer W. (2007) The Helicobacter pylori CagF protein is a type IV secretion chaperone-like molecule that binds close to the C-terminal secretion signal of the CagA effector protein. Microbiology 153, 2896–2909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sreerama N., Venyaminov S. Y., Woody R. W. (1999) Estimation of the number of α-helical and β-strand segments in proteins using circular dichroism spectroscopy. Protein Sci. 8, 370–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Stokkum I. H., Spoelder H. J., Bloemendal M., van Grondelle R., Groen F. C. (1990) Estimation of protein secondary structure and error analysis from circular dichroism spectra. Anal. Biochem. 191, 110–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sreerama N., Woody R. W. (2000) Estimation of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra: comparison of CONTIN, SELCON, and CDSSTR methods with an expanded reference set. Anal. Biochem. 287, 252–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Whitmore L., Wallace B. A. (2008) Protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopy: methods and reference databases. Biopolymers 89, 392–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fischer H., de Oliveira Neto M., Napolitano H. B., Polikarpov I., Craievich A. F. (2010) Determination of the molecular weight of proteins in solution from a single small-angle x-ray scattering measurement on a relative scale. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 43, 101–109 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Petoukhov M. V., Konarev P. V., Kikhney A. G., Svergun D. I. (2007) ATSAS 2.1—towards automated and web-supported small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, s223–s228 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nesić D., Miller M. C., Quinkert Z. T., Stein M., Chait B. T., Stebbins C. E. (2010) Helicobacter pylori CagA inhibits PAR1-MARK family kinases by mimicking host substrates. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 130–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Angelini A., Tosi T., Mas P., Acajjaoui S., Zanotti G., Terradot L., Hart D. J. (2009) Expression of Helicobacter pylori CagA domains by library-based construct screening. FEBS J. 276, 816–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lupas A., Van Dyke M., Stock J. (1991) Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 252, 1162–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vergunst A. C., van Lier M. C., den Dulk-Ras A., Stüve T. A., Ouwehand A., Hooykaas P. J. (2005) Positive charge is an important feature of the C-terminal transport signal of the VirB/D4-translocated proteins of Agrobacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 832–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fattori J., Prando A., Martins A. M., Rodrigues F. H., Tasic L. (2011) Bacterial secretion chaperones. Protein Pept. Lett. 18, 158–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sundberg C., Meek L., Carroll K., Das A., Ream W. (1996) VirE1 protein mediates export of the single-stranded DNA-binding protein VirE2 from Agrobacterium tumefaciens into plant cells. J. Bacteriol. 178, 1207–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abu-Arish A., Frenkiel-Krispin D., Fricke T., Tzfira T., Citovsky V., Wolf S. G., Elbaum M. (2004) Three-dimensional reconstruction of Agrobacterium VirE2 protein with single-stranded DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25359–25363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Frenkiel-Krispin D., Wolf S. G., Albeck S., Unger T., Peleg Y., Jacobovitch J., Michael Y., Daube S., Sharon M., Robinson C. V., Svergun D. I., Fass D., Tzfira T., Elbaum M. (2007) Plant transformation by Agrobacterium tumefaciens: modulation of single-stranded DNA-VirE2 complex assembly by VirE1. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3458–3464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kramer R. M., Shende V. R., Motl N., Pace C. N., Scholtz J. M. (2012) Toward a molecular understanding of protein solubility: increased negative surface charge correlates with increased solubility. Biophys. J. 102, 1907–1915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Backert S., Müller E. C., Jungblut P. R., Meyer T. F. (2001) Tyrosine phosphorylation patterns and size modification of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein after translocation into gastric epithelial cells. Proteomics 1, 608–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moese S., Selbach M., Zimny-Arndt U., Jungblut P. R., Meyer T. F., Backert S. (2001) Identification of a tyrosine-phosphorylated 35 kDa carboxy-terminal fragment (p35CagA) of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein in phagocytic cells: processing or breakage? Proteomics 1, 618–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ishikawa S., Ohta T., Hatakeyama M. (2009) Stability of Helicobacter pylori CagA oncoprotein in human gastric epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 583, 2414–2418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bagnoli F., Buti L., Tompkins L., Covacci A., Amieva M. R. (2005) Helicobacter pylori CagA induces a transition from polarized to invasive phenotypes in MDCK cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 16339–16344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]