Abstract

The aim of this review is to provide a general overview of the relationship between occupational stress and gastrointestinal alterations. The International Labour Organization suggests occupational health includes psychological aspects to achieve mental well-being. However, the definition of health risks for an occupation includes biological, chemical, physical and ergonomic factors but does not address psychological stress or other affective disorders. Nevertheless, multiple investigations have studied occupational stress and its physiological consequences, focusing on specific risk groups and occupations considered stressful. Among the physiological effects of stress, gastrointestinal tract (GIT) alterations are highly prevalent. The relationship between occupational stress and GIT diseases is evident in everyday clinical practice; however, the usual strategy is to attack the effects but not the root of the problem. That is, in clinics, occupational stress is recognized as a source of GIT problems, but employers do not ascribe it enough importance as a risk factor, in general, and for gastrointestinal health, in particular. The identification, stratification, measurement and evaluation of stress and its associated corrective strategies, particularly for occupational stress, are important topics to address in the near future to establish the basis for considering stress as an important risk factor in occupational health.

Keywords: Stress, Occupation, Gastric alterations, Gastrointestinal tract diseases, Health risks

Core tip: In workers, the combination of personality patterns (anxiety/depression), stress and negative emotions contribute to gastrointestinal tract (GIT) alterations. In particular, jobs that produce privation, fatigue, chronic mental anxiety and a long past history of tension, frustration, resentment, psychological disturbance or emotional conflict have been shown to produce gastric ulcers. Irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia also have significant co-morbidity with mood alterations. Workers with unipolar depression have been shown to be more prone to present irritable bowel syndrome-like symptoms. Moreover, three systems are known to participate in the GIT alterations of workers: sympathetic autonomic nervous system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and genetic factors.

INTRODUCTION

Stress is a term that is often used by the global population. This term was first described as a “syndrome produced by diverse nocuous agents” in the 1930s by Selye[1] and was later called General Adaptation Syndrome. Stress refers to the consequences of the failure of a living organism (i.e., human or animal) to respond appropriately to emotional or physical threats, whether actual or imagined[2]. Stress can be defined as any threat to an organism’s homeostasis[2,3]. The function of the stress response is to maintain homeostasis and may involve both physiological and behavioral adaptations[2]. Currently, stress is a condition that affects people daily. Environmental factors, such as work pressures, financial conditions, family situations and social issues, contribute to stress. Factors related to job stress include the need for counseling, lack of leisure time, daily shift work, dissatisfaction with the workplace, work absenteeism due to health problems and insufficient work incentives. All of these situations produce psychological stress that may affect different physiological functions in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT)[3], including gastric secretion, gut motility, mucosal permeability, mucosal barrier function, visceral sensitivity and mucosal blood flow[4]. There have been several studies on the effects of psychological stress on the GIT that debate if these effects constitute a physiological response of the body or if they can be considered a pathology[2-5]. In relation to occupations, it is difficult to define a psychological stress classification for determining stress levels, exposure duration, exposure limits to stressors, the sensitivity of the worker, etc.; therefore, as evidenced in most of the literature, the delimitation of the problem to be addressed is almost forced. In this review article, we consider general occupational stress as assessed using multiple approaches. Additionally, we focus on occupational stress associated with specific GIT problems in any worker group, but particularly in those groups working stressful jobs.

EFFECT OF PSYCHOLOGICAL STRESS AND EMOTIONS ON THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

The relationship between psychological stress and disease has already been recognized by the ancient Greeks, who hypothesized that moods affect the body. Hippocrates described how psychosomatic disorders produce abnormal physical reactions due to stressful emotions, and Galen supported the idea that emotions and pain are diseases of the soul. However, in 1637, Descartes changed the paradigm by proposing the separation of the thinking mind from the material body[5]. Currently, there are an increasing number of reports regarding cognitive and psychological declines related to stress, including occupational stress, in subjects without psychiatric pre-morbidities or major life trauma[6].

The relationship between emotions and gastric motility has been documented since the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century by Charles Cabanis and William Beaumont and thereafter by Ivan Pavlov, Walter Canon and Stewart Wolf, who were the pioneers in determining the gastric response after an emotional stimulus in animal models[7,8]. Based on these antecedents, researchers and clinicians were curious about the relationship between stress and gastric motility. For example, Muth et al[9] reported the case of a fistulated patient who displayed increased gastric motility when he was angry but decreased gastric motility when he was fearful. Nevertheless, in general, the role of occupational stress in gastric motility has not been closely examined. The main limitation, as far as we perceive, occurs because most of the techniques used for GIT evaluations are invasive[10].

The combination of personality patterns and emotional stress also has an important contribution to GIT alterations. In a review by Alp et al[11], studies were mentioned that suggested privation, fatigue and mental anxiety frequently coincided with the presence of gastric ulceration[12] and that a psychological disturbance or emotional conflict might be transformed into an organic disease, e.g., a peptic ulcer[13,14]. The same paper also mentioned that a significant correlation exists between the onset of peptic ulcer symptoms and domestic upset, financial stress or an extensive past history of tension[15]. Furthermore, anxiety, frustration, resentment and fatigue were suggested to be important aggravating factors in the symptomology of peptic ulceration[16]. Many of the emotional states previously described by these researchers are related to psychological stress.

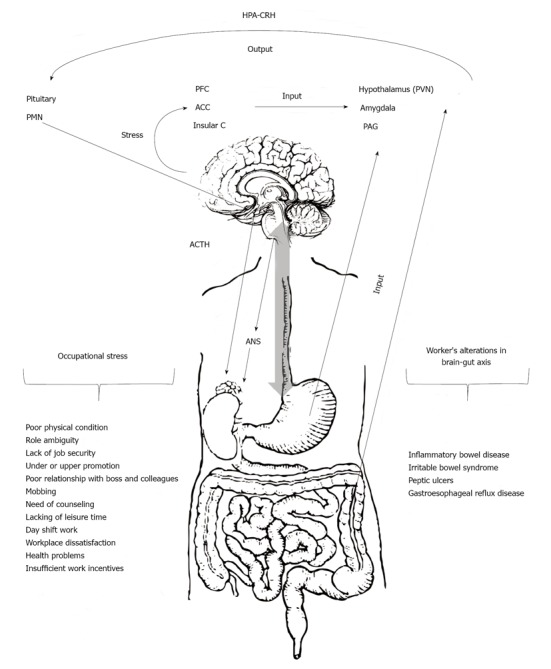

In relation to other GIT alterations, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional dyspepsia, a significant co-morbidity reportedly exists between mood alterations (e.g., anxiety and depression) and functional gastrointestinal syndromes[17]. However, the exact pathophysiological link between emotions and the gut is not yet well established (see below). A model of an emotional motor system (EMS) that reacts to interoceptive and exteroceptive stress was proposed by Karling et al[18]. These investigators found that recurrent unipolar depression patients who were experiencing remission did not have a greater number of IBS-like symptoms than the controls, indicating that GIT dysfunctions may resolve when depression is treated to remission. Apparently, there is a relationship between mood alterations (e.g., anxiety and depression) and IBS-like symptoms in patients with unipolar depression, in patients with IBS and in a sample of the normal population. In addition, the investigators suggested that, during the regulation of the emotional-motor system, there is a participation of the following three systems (the interrelationships of which are presented schematically in Figure 1): (1) the sympathetic autonomic nervous system (ANS), which explains symptoms that occur when patients change their body position; (2) the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which explains the symptoms of diarrhea and early satiety by the stimulation of Corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptors and (3) the val158met COMT polymorphism (single nucleotide polymorphism in the COMT gene that encodes Catechol-O-methyl-transferase), which is associated with IBS-like symptoms. IBS patients tend to have a lower frequency of the heterozygous val/met genotype, and this genotype may be protective against IBS/IBS-like symptoms. Moreover, a higher frequency of the val/val genotype is associated with diarrhea symptoms[19].

Figure 1.

Representation of the hypothetical mechanism by which occupational stress produces gastrointestinal tract alterations in workers. Stress during job development (see occupational stress) generates a response of the network integrated by the hypothalamus (paraventricular nucleus), amygdala and periaqueductal grey. These brain regions receive input from visceral and somatic afferents and from the medial prefrontal cortex (PFC) and the anterior cingulated (ACC) and insular cortices (Insular C). In turn, output from this integrated network to the pituitary and ponto-medullary nuclei (PMN) mediates the neuroendocrine and autonomic responses in the body. The final output of this central stress circuitry is called the emotional motor system and includes the autonomic neurotransmitters norepinephrine and epinephrine and neuroendocrine (hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, HPA) and pain modulatory systems. PVN: Paraventricular nucleus; PAG: Periaqueductal grey; GIT: Gastrointestinal tract; ACTH: Adrenocorticotropic hormone; CRH: Corticotrophin-releasing hormone; ANS: Autonomic nervous system.

JOB, OCCUPATION AND PSYCHOLOGICAL STRESS

A job is defined in the OECD Glossary of statistical terms[20] as a set of tasks and duties executed, or meant to be executed, by one person. Based on this description, an occupation is defined as a set of jobs whose main tasks and duties are characterized by a high degree of similarity. An occupational classification is a tool for organizing all jobs in an establishment, an industry or a country into a clearly defined set of groups according to the tasks and duties undertaken in the job. The occupation classification is generally not based on health risk factors. However, the concept of occupational health has been well-defined since 1950, when the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) created a common definition through the ILO/WHO Committee on Occupational Health. The definition reads as follows: “Occupational health should aim at the promotion and maintenance of the highest degree of physical, mental and social well-being of workers in all occupations…the placing and maintenance of the worker in an occupational environment adapted to his (her) physiological and psychological capabilities...”[21]. In this definition, the mental well-being and the psychological capabilities are mentioned; moreover, the main focus of occupational health describes the promotion of a “positive social climate”. The term health, in relation to work, indicates not merely the absence of disease or infirmity but also includes the physical and mental elements affecting health, which are directly related to safety and hygiene at work[22].

In 2001, the ILO published the ILO-OSH 2001 document titled “Guidelines on Occupational Safety and Health Management Systems” to assist organizations introducing OSH management systems[23]. Usually, occupational health hazards are considered as physical, chemical, biological and/or ergonomic factors; almost everywhere, psychological factors, such as stress[24], are not even mentioned. We consider that one of the main reasons for minimizing psycho-social factors is because the principles of occupational hygiene are the “recognition and/or identification” of occupational health hazards, the “measurement” of the level or concentration of such factors, the “evaluation” of the likelihood and severity of harm and the “control strategies” available to reduce or eliminate risks. Usually, recognition and identification implies the obvious correlation between cause and effect, with the effect being associated with physical illness or injury. In our case, psychological stress has been recognized and correlated with physical effects in many studies[25]. Furthermore, the control strategies (although a subjective topic) appear to be well known by professionals and therefore are well-established[26]. The measurement of levels or concentrations and the evaluation of the likelihood and severity of the stress factors are the most complicated factors to be studied quantitatively, and we consider these factors to be poorly established aspects of the problem.

Despite the discussion above, stress, particularly occupational stress, has become one of the most serious health issues in the modern world[27]. The concept of occupational stress can be observed as a natural extension of the classical concept of stress introduced by Selye[1] to a specific form of human activity, namely work. Steers[28] indicated that occupational stress has become an important topic study of organizational behavior for several reasons: (1) stress has harmful psychological and physiological effects on employees; (2) stress is a major cause of employee turnover and absenteeism; (3) stress experienced by one employee can affect the safety of other employees and (4) by controlling dysfunctional stress, individuals and organizations can be managed more effectively. More recently, Beheshtifar and Modaber[29] described five types of sources of occupational stress: (1) causes intrinsic to the job, including factors such as poor physical working conditions, work overload or time pressures; (2) the role in the organization, including role ambiguity and role conflict; (3) career development, including lack of job security and under/over promotion; (4) relationships at work, including poor relationships with the boss or colleagues, an extreme component of which is mobbing in the workplace; and (5) the organizational structure and climate, including the experience of having little involvement in decision-making and office politics.

The large diversity of stress factors, the complexity of labour activities and the large number of worker health-status levels make it very difficult to complete an exhaustive review of the relationships among GIT alterations, stress and occupational activity. Nevertheless, many delimited investigations have been performed around these topics, mainly for specific activities, delimited work places and/or specific groups of people. For example, in a controlled study of lorry drivers, de Croon et al [30] investigated the result of specific job demands on job stress (fatigue and job dissatisfaction), thereby identifying the risk factors associated with the psychosocial work environment to begin building an effective stress-reducing strategy. Another study of telemarketers directly addressed occupational stress by reporting the prevalence of stressors affecting job performance[31]. In a non-specific occupational study of migrants in Spain, Ronda et al[32] reported the occupational health-risk differences between local and foreign-born workers. These investigators listed what they called psychosocial factors, of which most were identified with stressful work conditions. Based on the self-reported exposure, this study revealed a larger difference in females in non-service jobs; although no specific attention was paid to psychosocial factors, the prevalence of exposure to occupational risk factors appeared to be, on average, higher for migrants. The same research group in Spain searched for risk factors during pregnancy using self-reports, which are the predominant method to report psychosocial risks. The results of these investigations revealed that the prevalence of the psychosocial risks was, on average, higher than any other chemical, physical or biological factors[33].

Several researchers studied the psychological stress in a specific pathology, for example, in diabetes. Golmohammadi et al[34] investigated the occupational stress in diabetic workers from Iran and found that the type of occupation was not an important factor in psychological stress, although a difference was evident in the patients compared with the control group. The researchers concluded that occupational stress may be a risk factor in the development of diabetes. Specific studies addressing jobs identified as stressful have been conducted. Examples of this type of work are the study of stress-factor risks in nurses from England[35] or in psychiatric nurses (i.e., a job with more exposure to psychological risks) in Japan[36]. Other stressful jobs are those related to the army and security services. Martins et al[37] studied the military hierarchy in peace times in the Brazilian Army, finding correlations with common mental disorders. Berg et al[38] studied security service workers, focusing on personality, anxiety and depression. Another type of occupation considered stressful is the mental health profession[39,40]. These professionals, similar to other workers exposed to long-term occupational stress, often experience the stage known as burnout. According to Selye’s definition, if stress is associated with adaptation, then occupational stress should be identified conceptually with a temporary adaptation to work that is associated with psychological and physical symptoms. The long-term process of adaptation to certain jobs yields chronic physical and psychological symptoms. The final stage in a breakdown during this adaptation is known as burnout and is caused by prolonged occupational stress[39,40]. In 1982, Belcastro[41] stated that several somatic complaints have been suggested to be associated with burnout, including gastrointestinal disturbances, nausea and loss of weight, which are some of the most common symptoms. The author suggested that specific illnesses appear to be associated with burnout, including colitis, gastrointestinal problems and drug and alcohol addiction, among others. Developed countries face different challenges than do non-developed countries, specifically, economic[42] and cultural differences, which have been considered in stress research[43]. Nonetheless, it is difficult to describe the occupational psychological-stress classifications, levels, exposure durations, exposure limits, sensitivity, etc. Therefore, in most of the literature, the delimitation of the problem to be addressed is almost forced. In this review article, we focus on occupational stress in general, assessed in any manner. Additionally, we focus on specific GIT problems in any worker group, but mainly in those groups dedicated to some jobs well-identified as stressful.

TYPE OF JOB, STRESS AND GIT ALTERATIONS

Currently, gastric ulcers are identified as an extremely common chronic disease in working-age adults. The first description of an association between stress and peptic ulcer disease was in men with supervisory jobs; these individuals had a higher ulcer prevalence than executives or artisans. Cobb and Rose[44] found that air traffic controllers, particularly those individuals with higher stress levels in their workplace, were almost twice as likely to have ulcers than the civilian copilots. Hui et al[45] noted that the numbers of positive and negative life events were similar in both subjects with dyspepsia and control subjects, but the former had a higher negative perception of major life events and daily stresses. Police officers’ work-stress reactions have been classified as physiological, emotional and behavioral reactions[46]. Physiological reactions have been termed as having a higher-than-normal probability of death from certain illnesses; after cardiovascular problems, stomach problems are the most frequent. Changing work shifts has also been associated with changes in the digestive system, circadian rhythm and other bodily reactions. Angolla[46] studied 229 police officers (163 males and 66 females) who answered a questionnaire consisting of five parts: demographics, external and internal work environments, coping mechanisms and symptoms. This investigator found that police work is highly stressful, and the highest rated symptoms were as follows: feeling a lack of energy, loss of personal enjoyment, increased appetite, feeling depressed, trouble concentrating, feeling restless, nervousness and indigestion. Satija et al[47] evaluated 150 professional workers (100 males and 50 females) who self-completed the Emotional Intelligence and Occupational Stress Scale. The authors’ findings demonstrated a negative correlation between emotional intelligence and occupational stress; those professionals with a high score in overall emotional intelligence suffered less stress. Shigemi et al[48] evaluated 585 employees (296 males and 289 females), all of whom were working at a middle-sized company in Japan. A self-administered questionnaire about smoking habits and perceived job stress was administered, and the patients were followed for two years. In addition, previous or current gastric or duodenal ulcers were evaluated. The researchers found 32 incidences of peptic ulcers over the two years, and the risk ratio (RR) was 2.13 (95%CI: 1.09-4.16) between job stress and peptic ulcers. Susheela et al[49] evaluated 462 smelter workers, 60 supervisors working in the smelter unit and 62 non-smelter workers (control group). The participants’ state of health and gastrointestinal complaints were recorded and included the following symptoms: nausea/loss of appetite, gas formation, pain in the stomach, constipation, diarrhea (intermittent) and headaches. The researchers found that the total number of complaints reported by the study groups was significantly higher than in the control group. The prevalence of gastrointestinal complaints in the smelter workers was significantly higher (P < 0.001) than in the non-smelter workers (control group). In 2006, Nakadaira et al[50] investigated the effects of tanshin funin (i.e., working far from one’s hometown and therefore far from one’s family) on the health of married male workers. A prospective study using the pair-matched method was performed in 129 married male tanshin funin workers who were 40-50 years of age. Matched workers living with their families also participated. These researchers demonstrated that fewer tanshin funin workers ate breakfast every day. Moreover, these workers more frequently suffered from stress due to daily chores and from stress-related health problems, namely, headache and gastric/duodenal ulcers (21% and 2.4%, respectively). The levels of gamma-glutamyl-transpeptidase in workers reluctant to work under tanshin funin conditions and in workers who spent less than two years in tanshin funin conditions increased significantly, although the corresponding levels in the matched regular workers did not exhibit significant changes. The investigators concluded that abrupt changes in lifestyle and elevated mental stress were thus important effects of tanshin funin.

Although jobs and occupations are considered a risk factor for stress and morbidity for gastric and duodenal ulcers[9,11,48], there are studies that report discrepancies. For example, Westerling et al[51] evaluated the socioeconomic differences in avoidable mortality in a Swedish population from 1986 to 1990. Using the population of 21- to 64-year-old individuals, the researchers performed analyses for different socioeconomic groups [blue-collar workers (BCWs), white-collar workers (WCWs) and the self-employed] and for individuals outside the labor market. The researchers demonstrated that the largest differences were found in ulcers of the stomach and duodenum, in addition to other symptoms. For these causes of death, the risk of dying was between 3.1 and 7.5 times greater in the non-working population than in the workforce. The differences in avoidable mortality between BCWs and WCWs and the self-employed were much smaller. However, the death rate for ulcers of the stomach and duodenum in BCWs was 2.8 times higher than for other work categories. The GIT and mortality problems reported by Wesrterling et al[51] used standardized mortality ratios for the occupied population. The ratios for malignant neoplasms of the large intestine, except for the rectum, were 95 in BCWs and 104 in WCWs and for malignant neoplasms in the rectum and rectum-sigmoid junction were 103 and 100 for BCWs and WCWs, respectively. However, for gastric and duodenal ulcers, the investigators reported ratios of 163 and 59 for these BCWs and WCWs, respectively. Moreover, the causes for mortality reported for abdominal hernia, cholelithiasis and cholecystitis were 127 and 86 for BCWs and WCWs, respectively. However, the researchers suggested that, as in most other studies, the follow-up period was short and that the exposure data from earlier censuses would be advantageous.

In Table 1, we summarize the international literature regarding the GIT disorders most frequently reported by workers experiencing job-related psychological stress and other alterations in their affective states. In a cross-sectional study with a population of 2237 subjects from San Marino, Italy, Gasbarrini et al[52] demonstrated that the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) was 51%; this prevalence increased with age from 23% (20-29 years) to 68% (> 70 years) and was higher among manual workers. In San Marino, there was a higher incidence of clinically relevant gastroduodenal diseases, such as peptic ulcer and gastric cancer (25 of 10000 and 8 of 10000 in 1990, respectively). With respect to Italy and other European countries, Gasbarrini et al[52] demonstrated that H. pylori infections tended to be more frequent among BCWs (P < 0.001), especially those doing manual work (miners 78%, road sweepers 65%, plumbers/painters 61%, housekeepers 60% and cooks 58%) compared with WCWs (physicians 15%, clerks 21%, secretaries 37%, nurses 38%, general managers and lawyers 38%, teachers 39% and shop workers 50%). A high prevalence of infection was also noted among social workers (74%). The researchers concluded that social workers with a high educational standard had a higher rate of seropositivity to H. pylori (74%) than did subjects with a similar socioeconomic status but a different type of job, thereby emphasizing the relevance of direct person-to-person spread of the infection. This result was also recently demonstrated in nurses and in cohabiting children. These findings suggest that poor hygienic standards and a low socioeconomic status (which frequently reflects the former) are important factors for acquiring H. pylori during the first years of life, thereby confirming previous findings regarding the differences between developed and developing countries and the importance of overcrowding and close person-to-person contact during childhood.

Table 1.

Summary of the international literature on the gastrointestinal tract disorders most frequently reported by workers experiencing job-related psychological stress and other alterations in their affective states

| GIT alteration | Ref. | Study/procedure | Conclusions |

| Generalized GIT disturbances/IBS | Konturek et al[4] | Impact of stress on the GIT. The study addresses the role of stress in the pathophysiology of the most common GIT diseases. | The exposure to stress is the major risk factor in the pathogenesis of various GIT diseases. |

| Bhatia et al[5] | Association between stress and various GIT pathologies. | The mind directly influences the gut. The enteric nervous system is connected bidirectionally to the brain by the parasympathetic and sympathetic pathways, forming the brain-gut axis. | |

| Karling et al[18] | Pre- and post-dexamethasone morning serum cortisol levels were analyzed in 124 subjects with symptoms of IBS. | There is a relationship between mood alterations (anxiety/depression) and IBS-like symptoms in patients with unipolar depression, in patients with IBS and in a sample of the normal population. | |

| Karling et al[19] | In total, 867 subjects representative of the general population and 70 patients with IBS were genotyped for the val158met polymorphism. The IBS patients completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale questionnaire. | There is an association between the val/val genotype of the val158met COMT gene and IBS and with the specific IBS-related bowel pattern in IBS patients. | |

| Belcastro et al[41] | Estimation of the relationship between teachers’ somatic complaints and illnesses and their self-reported job-related stresses. Stress group: teachers | Several somatic complaints have been suggested to be associated with burnout. | |

| Hui et al[45] | Perception of life events and the role of daily "hassles" (stressful events) in 33 dyspeptic patients vs 33 controls of comparable sex, age and social class. | Patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia have a higher negative perception of major life events than controls. Psychological factors may play a role in the pathogenesis of non-ulcer dyspepsia. | |

| Angolla et al[46] | Empirical study of police-work stress, symptoms and coping strategies among police service workers in Botswana measured by a questionnaire. Sample size n = 229 (163 males and 66 females). Stress group: the Botswana Police Service. | Police duties are highly stressful. The highest rated symptoms were as follows: feeling a lack of energy, loss of personal enjoyment, increased appetite, feeling depressed, trouble concentrating, feeling restless, nervousness and indigestion. | |

| Ulcers | Alp et al[11] | Comparative study using a neuroticism-scale questionnaire administered to 181 patients with previously diagnosed gastric ulcers and 181 controls without any previous history of gastric ulcers. | People with a past history of chronic gastric ulcers have an increased incidence of domestic and financial stress compared with age- and sex-matched individuals with no previous history of gastric ulcers. |

| Cobb et al[44] | Review of aeromedical certification examinations of 4325 traffic controllers and 8435 second-class aviators. Stress group: air traffic controllers. | Air traffic controllers were almost twice as likely to have stomach ulcers as civilian copilots . | |

| Shigemi et al[48] | Two-year study to examine the role of perceived job stress on the relationship between smoking and peptic ulcers. | These results suggest that specific and perceived job stress is an effect modifier in the relationship between the history of peptic ulcers and smoking. | |

| Nakadaira et al[50] | Effects of working far from family on the health of 129 married male workers (40-50 yr of age) compared with the control group. | The tanshin funin workers had higher rates of missing breakfast, stress due to daily chores and stress-related health problems (e.g., headache, gastric/duodenal ulcers and common colds/bronchitis). | |

| Westerling et al[51] | 1985 study of the Swedish population (21-64 yr of age). Analyses of standardized mortality ratios (avoidable mortality) of blue-collar workers, white-collar workers, self-employed workers, and individuals outside the labor market. Stress group: Unemployed individuals | The death rates for the non-workers were higher than for the workers. The largest differences were found for stomach and duodenal ulcers. | |

| Lin et al[53] | 289 call center workers in Taiwan, 19 to 54 yr of age. Health complaints, perceived level of job stress and major job stressors were considered. Stress group: call center workers. | Workers who perceived higher job stress had significantly increased risks of multiple health problems, including hoarse or sore throat, irritable stomach and peptic ulcers. | |

| Gastric motility alterations | Mawdsley et al[2] | Review of recent advances in the understanding of the pathogenic role of psychological stress in IBD, with an emphasis on the necessity of investigating the therapeutic potential of stress reduction. | The living-organism (human or animal) responds to emotional or physical threats. Psychological stress contributes to the risk of IBD relapse. |

| Huerta-Franco et al[3] | Bioimpedance technique. In this study, 57 healthy women (40-60 yr of age) were analyzed. | Assessment of the changes in gastric motility induced by acute psychological stress. | |

| Mai et al[7] | Description or tracking of 238 experiments conducted over more than 10 yr on a young man (Beaumont) with digestive disorders. | Emotions can cause bile reflux into the stomach and may delay gastric emptying. | |

| Wolf et al[8] | Description of the work of the French physiologist Cabanis. | Inhibitory and excitatory effects of gastric secretory and motor function were described. | |

| Muth et al[9] | Electrogastrograms were recorded, and the inter-beat intervals were obtained from electrocardiographic recordings from 20 subjects during baseline and in response to a shock avoidance task (shock stimulus) and forehead cooling (dive stimulus). | Acute stress can evoke arousal and dysrhythmic gastric myoelectrical activity. These acute changes, which occur in healthy individuals, may provide insight into functional gastrointestinal disorders. |

GIT: Gastrointestinal tract; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome; COMT: catechol-O-methyltransferase.

In 2009, Lin et al[53] investigated 289 call-center workers (mean age of 33.6 years) to investigate how these workers perceived their job stress and health status and the relationships among inbound (incoming calls) versus outbound (outgoing calls) workers in a Taiwanese bank. Data were obtained on individual factors, health complaints, perceived job stress levels and major job stressors (using the 22-item Job Content Questionnaire, C-JCQ). For inbound services, operators handled approximately 120 to 150 calls during each 8 h per day. Outbound operators were primarily responsible for sales and handled approximately 120 calls daily. The subjects completed the self-administered questionnaires during their leisure time (taking between 15 and 20 min). The results demonstrated that 33.5% of outbound service-call center workers and 27.1% of inbound service-call center workers were classified as suffering from high stress, which was considerably higher than figures from a wider survey of the working population in Taiwan (7.6%). The researchers demonstrated a relationship between the perceived job stress and health complaints, indicating that workers who perceived a higher job stress had a significantly increased risk of multiple health problems (OR ranging from 2.13 to 8.24), including an irritable stomach and peptic ulcers [42% and 57% for inbound and outbound operators, respectively (P < 0.05)]. For example, the OR of irritable stomach and peptic ulcers when the stress was moderate (i.e., sometimes feeling extremely stressed at work) was 3.03 (95%CI: 1.40-6.55) and when the stress was high (i.e., often or always feeling extremely stressed at work) was 8.24 (95%CI: 3.56-19.09). The researchers concluded that there is an association between the perceived job stress and health complaints, as workers who perceived a high level of job stress had significantly increased risks of irritable stomach and peptic ulcers.

In 2011, Nabavizadeh[54] demonstrated that physical and psychological stress increase gastric acid and pepsin secretions possibly by raising the gastric tissue nitric oxide level. In return, the increased gastric acid and pepsin secretions cause necrotic and inflammatory changes in the gastric and duodenal tissue.

STRESS IN THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF GASTROINTESTINAL ALTERATIONS

Currently, many adults die from diseases caused by the relationship between stress, moods and vital organs; among these diseases, GIT has become a major clinical problem. Stress is an acute threat to the homeostasis of an organism, either physically or psychologically. A number of studies have shown that stress can delay gastric emptying, impair gastro-duodenal motility[3], modify gastric secretions[55] and pancreatic output and alter intestinal transit and colonic motility. Owing to its considerable effects on physiological and pathophysiological processes of gastrointestinal (GI) motility, stress is thought to play an important role in the development, maintenance and exacerbation of symptoms related to functional GI disorders. To analyze the effects of occupational stress on GIT function, it is important to have an understanding of the physiology of GIT motility and emptying. Similar to almost every other system, the physiological processes that occur in the GIT are wide-ranging; the major function of the GIT includes swallowing, motility, emptying (of every section), assimilation and elimination. Motility enables swallowing, transit, emptying and elimination, and all these functions are essential for proper assimilation[56]. Beginning with swallowing and ending with elimination, motility is required for GIT function[57,58]. Two variables related to GIT motility are particularly important: (1) peristalsis, which is a function of the frequency and magnitude of the gastric contractions that are generated by the pacemaker area and (2) gastric emptying, which is a measure of the average time the stomach takes to empty half of its luminal content. The ANS regulates GIT motility, controlling peristaltic activity through the myenteric system[59,60] (Figure 1). In fact, alterations in GIT motility are frequently viewed as signs of neuropathy of the myenteric plexus or other pathologies of neuropathic origin. Abnormal gastric emptying is considered a clinical marker for a gastric or intestinal motility disorder[61,62]. Quigley and other researchers have found a relationship between stress and delayed gastric emptying or other motor disturbances[63-65]. This factor is understood by analyzing how the human body reacts defensively when threatened by the environment and when attempting to achieve both physical and psychological balance. However, activation of these adaptive or allostatic systems can become maladaptive because of frequent, chronic or excessive stress and can cause a predisposition to disease[5]. This explanation leads to the concept of brain-gut interaction described by Mawdsley and Rampton[2]. These authors mentioned that, to maintain homeostasis, a living organism must constantly adapt to environmental alterations at a molecular, cellular, physiological and behavioral level. As presented in Figure 1, these investigators hypothesized that exposure to psychological stress causes alterations of the brain-gut interactions (brain-gut axis), ultimately leading to the development of a broad array of GIT disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, other functional GIT diseases, food antigen-related adverse responses, peptic ulcers and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD)[16,19]. For instance, IBS is presumed to be a disorder of the brain-gut link associated with an exaggerated response to stress[66].

More recently, relative importance has been ascribed to the hypothesis that emotional and environmental states in females play an important role in the genesis of IBS[2]. This hypothesis has been proved by demonstrating that, worldwide, women present the highest prevalence of physical and psychological symptoms compared with males[67]. Men may be more apt to experience stress due to unfamiliar house chores than women, and women are more likely to experience occupational stress than men[50]. The emotions and stress experienced by workers (Figure 1) play an important role in exaggerated gut responses. Stress affects the relationship between the brain and gut, leading these systems to act defensively to real or imaginary threats.

In Figure 1, we present the pathophysiological mechanism by which stress has been proposed to produce GIT alterations in workers. The workers’ responses to stress are generated by a network comprising integrated brain structures, particularly sub-regions of the hypothalamus (paraventricular nucleus), amygdala and periaqueductal grey. These brain regions receive input from visceral and somatic afferents and from cortical regions, including the medial prefrontal cortex and sub-regions of the anterior cingulated and insular cortices. In turn, output from this integrated network to the pituitary and ponto-medullary nuclei mediates the neuroendocrine and autonomic responses in the body[4,18,19]. The final output of this central stress circuitry is called the emotionalmotorsystem and includes the autonomic neurotransmitters norepinephrine and epinephrine, the neuroendocrine HPA axis and the pain modulatory systems. This circuit is under feedback control by serotonergic neurons from the raphe nuclei and noradrenergic neurons from the locus coeruleus[5].

The neuroendocrine response to stress is mediated by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). In the brain-gut-axis, CRH is considered a major mediator of the stress response. Particularly, the stress-related activation of CRH receptors has been reported to produce alterations in GIT function. Physical and psychological stress delays gastric emptying, accelerates colonic transit and evokes colonic motility in rats. Accelerated colonic motor function can be produced by the central or peripheral administration of CRH and is blocked by treatment with a variety of CRH antagonists. In a clinical trial, Sagami et al[68] administrated a non-selective CRH antagonist (10 ug/kg of αhCRH) to 10 IBS patients and 10 healthy controls. The researchers demonstrated that the peripheral administration of αhCRH improved GIT motility, visceral perception and negative moods in response to gut stimulation, without affecting the HPA axis in IBS patients. This response was significantly suppressed in IBS patients but not in controls after the administration of αhCRH[68]. IBS is considered a disorder of the brain-gut-link. Psychological stress induces colonic segmental contractions, which are exaggerated in IBS patients. Similarly, the peripheral administration of CRH affects colonic motility, induces abdominal symptoms and stimulates adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion, all of which are also exaggerated in IBS patients[69]. Two CRH receptor subtypes, R1 and R2, have been suggested to mediate increased colonic motor activity and slowed gastric emptying, respectively, in response to stress[5].

The genesis of gastric ulcers by stress was demonstrated in the study of Saxena et al[70], who investigated the gastro-protective effect of citalopram (an antidepressant drug) both as a single dose pre-treatment and 14-d repeated pre-treatment for animals exposed to cold restraint stress (CRS). The results revealed that the plasma corticosterone level significantly increased in the stress group compared with the control group. Furthermore, mucosal ulceration, epithelial cell loss and a ruptured gastric mucosal layer at the ulcer site were observed in the gastric mucosa of rats exposed to CRS. Repeated citalopram pretreatment decreased the CRS-induced enhancement in the corticosterone level. The researchers also demonstrated that citalopram at doses of 5, 10 and 20 mg/kg significantly attenuated the CRS-induced gastric mucosal lesions.

In summary, gastric ulcers are identified as an extremely common chronic disease in working-age adults. In workers, the combination of personality patterns (e.g., anxiety and depression), stress and negative emotions significantly contribute to GIT alterations. Particular jobs that produce privation, fatigue or chronic mental anxiety and a long past history of tension, frustration, resentment, psychological disturbance or emotional conflict lead to gastric ulcers (e.g., in traffic controllers, police officers, smelter workers, tanshin funin workers, health professionals and manual workers). Irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia also exhibit significant co-morbidities between mood alterations in workers (i.e., anxiety and depression). Workers with unipolar depression were shown to be more prone to present IBS-like symptoms. Moreover, three systems are known to participate in the mechanism of GIT alterations in workers: (1) the sympathetic ANS, (2) the HPA axis and (3) genetic factors.

Subjective evaluations of stress (mainly self-reported) are extremely common in the clinic and in research. However, much work must first be done to quantitatively identify the psychological stress (i.e., the occupational stress level in this case), considering the particularity of each worker (i.e., the general health, the social and physical adaptation capacity and the physical and psychological vulnerability). The unique demands of each occupation require unique profiles of each worker. It is essential to train workers not only in specific skills but also in human and social aspects that include stress control strategies. Although the word “stress” has been included in our everyday language (even in research), the term continues to be a vague concept, even with the clear definition coined in 1936 by Selye.

Footnotes

Supported by Dirección de Apoyo a la Investigación y al Posgrado (DAIP); University of Guanajuato (2012-2013); and Programa Integral de Fortalecimiento Institucional (PIFI-SEP) 2012

P- Reviewer: Acuna-Castroviejo D S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Selye H. A syndrome produced by diverse nocuous agents. 1936. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;10:230–231. doi: 10.1176/jnp.10.2.230a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mawdsley JE, Rampton DS. Psychological stress in IBD: new insights into pathogenic and therapeutic implications. Gut. 2005;54:1481–1491. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.064261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huerta-Franco MR, Vargas-Luna M, Montes-Frausto JB, Morales-Mata I, Ramirez-Padilla L. Effect of psychological stress on gastric motility assessed by electrical bio-impedance. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5027–5033. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i36.5027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konturek PC, Brzozowski T, Konturek SJ. Stress and the gut: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, diagnostic approach and treatment options. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;62:591–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatia V, Tandon RK. Stress and the gastrointestinal tract. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:332–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blix E, Perski A, Berglund H, Savic I. Long-term occupational stress is associated with regional reductions in brain tissue volumes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mai FM. Beaumont’s contribution to gastric psychophysiology: a reappraisal. Can J Psychiatry. 1988;33:650–653. doi: 10.1177/070674378803300715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolf S. The stomach’s link to the brain. Fed Proc. 1985;44:2889–2893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muth ER, Koch KL, Stern RM, Thayer JF. Effect of autonomic nervous system manipulations on gastric myoelectrical activity and emotional responses in healthy human subjects. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:297–303. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huerta-Franco MR, Vargas-Luna M, Montes-Frausto JB, Flores-Hernández C, Morales-Mata I. Electrical bioimpedance and other techniques for gastric emptying and motility evaluation. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2012;3:10–18. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v3.i1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alp MH, Court JH, Grant AK. Personality pattern and emotional stress in the genesis of gastric ulcer. Gut. 1970;11:773–777. doi: 10.1136/gut.11.9.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brinton W. Lectures on the Diseases of the Stomach. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard; 1865. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander F. Psychosomatic medicine: its principles and applications. New York: Norton; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Højer-Pedersen W. On the significance of psychic factors in the development of peptic ulcer; a comparative personality investigation in male duodenal ulcer-patients and controls. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand Suppl. 1958;119:1–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies DT, Wilson ATM. Observations of the life history of chronic peptic ulcer. The Lancet. 1937;230:1353–1360. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones FA. Clinical and social problems of peptic ulcer. Br Med J. 1957;1:719–723; contd. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5021.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Malley D, Quigley EM, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Do interactions between stress and immune responses lead to symptom exacerbations in irritable bowel syndrome? Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:1333–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karling P, Norrback KF, Adolfsson R, Danielsson A. Gastrointestinal symptoms are associated with hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression in healthy individuals. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:1294–1301. doi: 10.1080/00365520701395945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karling P, Danielsson Å, Wikgren M, Söderström I, Del-Favero J, Adolfsson R, Norrback KF. The relationship between the val158met catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) polymorphism and irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Labour Office. Structure, group definitions and correspondence tables. In: International standard classification of occupations: ISCO-08., editor. Geneva: International Labour Office; 2012. pp. 1–420. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee PCB. Going beyond career plateau: Using professional plateau to account for work outcomes. JMD. 2003;22:538–551. [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Labour Organization. Occupational safety and health convention: C155. 1981. Cited 2013-02-15. Available from: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID: 312300#A1.

- 23.International Labour Office. Guidelines on occupational safety and health management systems: ILO-OSH 2001. Geneva: International Labour Office; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang D, Zhang J, Liu M. Application of a health risk classification method to assessing occupational hazard in China. Jun 11-13; Bejing. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering; 2009. pp. ICBBE, 2009: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rostamkhani F, Zardooz H, Zahediasl S, Farrokhi B. Comparison of the effects of acute and chronic psychological stress on metabolic features in rats. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2012;13:904–912. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1100383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereira MA, Barbosa MA. Teaching strategies for coping with stress--the perceptions of medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee PCB. Going beyond career plateau: using professional plateau to account for work outcomes. J Manag Dev. 2003;22:538–551. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steers RM. Introduction to organizational behavior. Glenview: Scott Foresman Publishing; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beheshtifar M, Modaber H. The investigation of relation between occupational stress and career plateau. Interdisciplinary J Contemp Res Bus. 2013;4:650–660. [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Croon EM, Blonk RW, de Zwart BC, Frings-Dresen MH, Broersen JP. Job stress, fatigue, and job dissatisfaction in Dutch lorry drivers: towards an occupation specific model of job demands and control. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59:356–361. doi: 10.1136/oem.59.6.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santos AC, Vianna MI. Prevalence of stress reaction among telemarketers and psychological aspects related to occupation. Epidemiol Comm Health. 2011;65:A416. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ronda E, Agudelo-Suárez AA, García AM, López-Jacob MJ, Ruiz-Frutos C, Benavides FG. Differences in exposure to occupational health risks in Spanish and foreign-born workers in Spain (ITSAL Project) J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15:164–171. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9664-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.García AM, González-Galarzo MC, Ronda E, Ballester F, Estarlich M, Guxens M, Lertxundia A, Martinez-Argüelles B, Santa Marina L, Tardón A, et al. Prevalence of exposure to occupational risks during pregnancy in Spain. Int J Public Health. 2012;57:817–826. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Golmohammadi R, Abdulrahman B. Relationship between occupational stress and non-insulin-dependent diabetes in different occupation in Hamadan (West of Iran) J Med Sci. 2006;6:241–244. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mark G, Smith AP. Occupational stress, job characteristics, coping, and the mental health of nurses. Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17:505–521. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leka S, Hassard J, Yanagida A. Investigating the impact of psychosocial risks and occupational stress on psychiatric hospital nurses’ mental well-being in Japan. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2012;19:123–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martins LC, Lopes CS. Military hierarchy, job stress and mental health in peacetime. Occup Med (Lond) 2012;62:182–187. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqs006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berg AM, Hem E, Lau B, Ekeberg Ø. An exploration of job stress and health in the Norwegian police service: a cross sectional study. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2006;1:26. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-1-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lasalvia A, Tansella M. Occupational stress and job burnout in mental health. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2011;20:279–285. doi: 10.1017/s2045796011000576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rössler W. Stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction in mental health workers. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262 Suppl 2:S65–S69. doi: 10.1007/s00406-012-0353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belcastro PA. Burnout and its relationship to teachers’ somatic complaints and illnesses. Psychol Rep. 1982;50:1045–1046. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1982.50.3c.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haq Z, Iqbal Z, Rahman A. Job stress among community health workers: a multi-method study from Pakistan. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2008;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor SE, Welch WT, Kim HS, Sherman DK. Cultural differences in the impact of social support on psychological and biological stress responses. Psychol Sci. 2007;18:831–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cobb S, Rose RM. Hypertension, peptic ulcer, and diabetes in air traffic controllers. JAMA. 1973;224:489–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hui WM, Shiu LP, Lam SK. The perception of life events and daily stress in nonulcer dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:292–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Angolla EJ. Occupational Stress among police officers: the case of Botswana Police Service. J Bus Manag. 2009;3:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Satija S, Khan W. Emotional intelligence as predictor of occupational Stress among working Professionals. Prin. LN Welingkar Institute of Management Development & Research. 2013;15:79–97. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shigemi J, Mino Y, Tsuda T. The role of perceived job stress in the relationship between smoking and the development of peptic ulcers. J Epidemiol. 1999;9:320–326. doi: 10.2188/jea.9.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Susheela AK, Mondal NK, Singh A. Exposure to fluoride in smelter workers in a primary aluminum industry in India. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2013;4:61–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakadaira H, Yamamoto M, Matsubara T. Mental and physical effects of Tanshin funin, posting without family, on married male workers in Japan. J Occup Health. 2006;48:113–123. doi: 10.1539/joh.48.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Westerling R, Gullberg A, Rosén M. Socioeconomic differences in ‘avoidable’ mortality in Sweden 1986-1990. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:560–567. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gasbarrini G, Pretolani S, Bonvicini F, Gatto MR, Tonelli E, Mégraud F, Mayo K, Ghironzi G, Giulianelli G, Grassi M. A population based study of Helicobacter pylori infection in a European country: the San Marino Study. Relations with gastrointestinal diseases. Gut. 1995;36:838–844. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.6.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin YH, Chen CY, Hong WH, Lin YC. Perceived job stress and health complaints at a bank call center: comparison between inbound and outbound services. Ind Health. 2010;48:349–356. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.48.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nabavizadeh F, Vahedian M, Sahraei H, Adeli S, Salimi E. Physical and psychological stress have similar effects on gastric acid and pepsin secretions in rat. J Stress Physiology Biochem. 2011;7:164–174. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huerta-Franco R, Vargas-Luna M, Hernandez E, Capaccione K, Cordova T. Use of short-term bio-impedance for gastric motility assessment. Med Eng Phys. 2009;31:770–774. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wenger MA, Engel BT, Clemens TL, Cullen TD. Stomach motility in man as recorded by the magnetometer method. Gastroenterology. 1961;41:479–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doglietto F, Prevedello DM, Jane JA, Han J, Laws ER. Brief history of endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery--from Philipp Bozzini to the First World Congress of Endoscopic Skull Base Surgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19:E3. doi: 10.3171/foc.2005.19.6.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Janssen P, Vanden Berghe P, Verschueren S, Lehmann A, Depoortere I, Tack J. Review article: the role of gastric motility in the control of food intake. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:880–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sobreira LF, Zucoloto S, Garcia SB, Troncon LE. Effects of myenteric denervation on gastric epithelial cells and gastric emptying. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2493–2499. doi: 10.1023/a:1020508009213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Quintana E, Hernández C, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Esplugues JV, Barrachina MD. Synthesis of nitric oxide in postganglionic myenteric neurons during endotoxemia: implications for gastric motor function in rats. FASEB J. 2004;18:531–533. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0596fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quigley EMM. Gastric motor and sensory function and motor disorders of the stomach. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Sleisenger MH, editors. Gastrointestinal and liver disease. 7th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2002. pp. 691–713. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Giouvanoudi A, Amaee WB, Sutton JA, Horton P, Morton R, Hall W, Morgan L, Freedman MR, Spyrou NM. Physiological interpretation of electrical impedance epigastrography measurements. Physiol Meas. 2003;24:45–55. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/24/1/304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quigley EM. Review article: gastric emptying in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 7:56–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stanghellini V, Malagelada JR, Zinsmeister AR, Go VL, Kao PC. Stress-induced gastroduodenal motor disturbances in humans: possible humoral mechanisms. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:83–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Paternico A, Barbara G, Morselli-Labate AM, Monetti N, Marengo M, Corinaldesi R. Risk indicators of delayed gastric emptying of solids in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1036–1042. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8612991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Delvaux M. Role of visceral sensitivity in the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2002;51 Suppl 1:i67–i71. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.suppl_1.i67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huerta R, Brizuela-Gamiño OL. Interaction of pubertal status, mood and self-esteem in adolescent girls. J Reprod Med. 2002;47:217–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sagami Y, Shimada Y, Tayama J, Nomura T, Satake M, Endo Y, Shoji T, Karahashi K, Hongo M, Fukudo S. Effect of a corticotropin releasing hormone receptor antagonist on colonic sensory and motor function in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2004;53:958–964. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.018911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sagami Y, Hongo M. [The gastrointestinal motor function in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)] Nihon Rinsho. 2006;64:1441–1445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saxena B, Singh S. Investigations on gastroprotective effect of citalopram, an antidepressant drug against stress and pyloric ligation induced ulcers. Pharmacol Rep. 2011;63:1413–1426. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70705-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]