Abstract

In this study, a polyphasic approach was used to study the ecology of fresh sausages and to characterize populations of lactic acid bacteria (LAB). The microbial profile of fresh sausages was monitored from the production day to the 10th day of storage at 4°C. Samples were collected on days 0, 3, 6, and 10, and culture-dependent and -independent methods of detection and identification were applied. Traditional plating and isolation of LAB strains, which were subsequently identified by molecular methods, and the application of PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) to DNA and RNA extracted directly from the fresh sausage samples allowed the study in detail of the changes in the bacterial and yeast populations during storage. Brochothrix thermosphacta and Lactobacillus sakei were the main populations present. In particular, B. thermosphacta was present throughout the process, as determined by both DNA and RNA analysis. Other bacterial species, mainly Staphylococcus xylosus, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, and L. curvatus, were detected by DGGE. Moreover, an uncultured bacterium and an uncultured Staphylococcus sp. were present, too. LAB strains isolated at day 0 were identified as Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis, L. casei, and Enterococcus casseliflavus, and on day 3 a strain of Leuconostoc mesenteroides was identified. The remaining strains isolated belonged to L. sakei. Concerning the yeast ecology, only Debaryomyces hansenii was established in the fresh sausages. Capronia mansonii was initially present, but it was not detected after the first 3 days. At last, L. sakei isolates were characterized by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA PCR and repetitive DNA element PCR. The results obtained underlined how different populations took over at different steps of the process. This is believed to be the result of the selection of the particular population, possibly due to the low storage temperature employed.

Fresh sausages are products made of pork, beef, or mixed meats, with the addition of salt, different aromas and spices, white wine, pepper, and garlic, depending on local preparation. The traditional Italian fresh sausage is produced only with the use of pork meat, pork fat, aromas, and salt. The meat and the fat are ground together in pieces that can have different dimensions based on the type of sausage to be produced. The different ingredients after mixing are used to fill natural casings from pigs or goats. The fresh sausages can be packaged in normal or modified atmosphere and stored at 4°C for a maximum period of 10 days.

Fresh sausages are highly perishable products with a pH value not lower than 5.5 and water activity (Aw) equal to or higher than 0.97. Since no fermentation process is taking place during the storage at 4°C, the hygienic quality of the raw materials is the main factor affecting the final value of the product.

The microbiological profile of the product is characterized by the presence of aerobes, facultative anaerobes, psychrotrophs, mesophiles, which are responsible for spoilage, and potentially pathogenic bacteria. In Italy, no addition of antimicrobial substances can be performed. For this reason, refrigeration at 4°C is the only available technology to preserve this product (40).

The main studies performed on fresh sausages focused on the evaluation of the hygienic quality (2, 8, 30), the color (6, 41), and the use of a combination of chitosan and carnocin for preservation (32). No investigation of the microbial ecology of this product during storage has been performed.

In this last decade, the profiling of bacterial populations became more and more accurate with the application of molecular methods to directly detect DNA and RNA in microbial ecosystems. The possibility to exploit the potential of PCR to amplify, theoretically, a single nucleic acid molecule allows the detection of low-number populations that may be lost when traditional methods, such as plating or selective enrichments, are used. These strategies eliminate the necessity for strain isolation, thereby negating the potential biases inherent to microbial enrichment. Moreover, studies that have employed such direct analysis have repeatedly demonstrated a tremendous variance between cultivated and naturally occurring species, thereby dramatically altering perceptions of the true microbial diversity present in various habitats (16, 18, 19, 29).

One culture-independent method for studying the diversity of microbial communities is analysis of PCR products, generated with primers homologous to relatively conserved regions in the genome, by using denaturant gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) or temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (24, 26). These approaches allow separation of DNA molecules that differ by single bases (27) and hence have the potential to provide information about variations in target genes in a bacterial population.

In this paper, we describe the application of a polyphasic approach, with the use of culture-dependent and -independent methods, to study the ecology of fresh sausages during the 10-day storage at 4°C. Samples were subjected to traditional microbiological analysis, direct DNA and RNA extraction, followed by PCR and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR with primers able to detect bacterial and yeast populations, and DGGE analysis on the amplified products. Moreover, strains of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were isolated, subsequently identified by molecular methods, and characterized by the use of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) PCR analysis (5) and PCR amplification of repetitive bacterial DNA elements (rep-PCR) (37).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial control strains.

The strains used in the study are reported in Table 1. They were grown in MRS broth (Oxoid, Milan, Italy) containing 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose at 30°C for 24 h.

TABLE 1.

LAB strains used in this study

| Species | Code | Sourcea |

|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus casei | 20011 | DSM |

| Lactobacillus curvatus | 20019 | DSM |

| Lactobacillus curvatus | G442 | Fermented sausage |

| Lactobacillus curvatus | 1432 | LHT |

| Lactobacillus paracasei | 335 | ATCC |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | 20174 | DSM |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | 1193 | NCDO |

| Lactobacillus sakei | 6333 | DSM |

| Lactobacillus mesenteroides | 20343 | DSM |

Abbreviations: ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va; DSM, Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany; NCDO, see NCFB, National Collection of Food Bacteria, Aberdeen, Scotland, United Kingdom; LHT, Institut für Lebensmitteltechnologie, Universität Hohenheim, Stuttgart, Germany.

Fresh sausage technology and sampling procedures.

Fresh sausages were prepared in a local meat factory by traditional techniques. Seventy kilograms of pork meat, 30 kg of pork lard, 3.5 kg of sodium chloride, 35 g of black pepper, and lemon zest were mixed and used to fill natural casings. No sugars were added to the mixtures. Sausages, which were about 10 cm long and 2 cm in diameter, were chilled immediately at 4°C and stored for a total period of 10 days. The meat mix before the filling and the fresh sausages at 3, 6, and 10 days were analyzed. Three samples at each step of sampling were collected and used for analysis.

pH measurements.

Potentiometric measurements of pH were made with a pin electrode of a pH meter (Radiometer Copenhagen pH M82, Cecchinato, Italy) inserted directly into the sample. Three independent measurements were made on each sample. Means and standard deviations were calculated.

Microbiological analysis.

The samples were subjected to microbiological analysis to monitor the dynamic changes during storage of the fresh sausages and their hygienic quality. In particular, 25 g of each sample was transferred to a sterile stomacher bag and 225 ml of saline-peptone water (8 g of NaCl/liter, 1 g of bacteriological peptone/liter; Oxoid) was added and mixed for 1.5 min in a stomacher machine (PBI, Milan, Italy). Further decimal dilutions were made, and the following analyses were carried out on duplicate agar plates: (i) total aerobic mesophilic flora on peptone agar (8 g of bacteriological peptone/liter, 15 g of bacteriological agar/liter; Oxoid) incubated for 48 to 72 h at 30°C; (ii) LAB on MRS agar (Oxoid) incubated with a double layer at 30°C for 48 h; (iii) Micrococcaceae on mannitol salt agar (Oxoid) incubated at 30°C for 48 h; (iv) total enterobacteria and Escherichia coli on Coli-ID medium (Bio-Merieux, Marcy d'Etoile, France) incubated with a double layer at 37°C for 24 to 48 h; (v) fecal enterococci on kanamycin esculin agar (Oxoid) incubated at 42°C for 24 h; (vi) Staphylococcus aureus on Baird Parker medium (Oxoid) with added egg yolk tellurite emulsion (Oxoid) incubated at 37°C for 24 to 48 h; (vii) yeasts and molds on malt extract agar (Oxoid) supplemented with tetracycline (1 mg/ml; Sigma, Milan, Italy) incubated at 25°C for 48 to 72 h. After counting, means and standard deviations were calculated. Twenty LAB strains from MRS plates at each sampling point were randomly selected, streaked on MRS agar, and stored at −20°C in MRS broth containing 30% glycerol before being subjected to molecular analysis.

DNA extraction from pure cultures.

Four milliliters of a 24-h culture were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to pellet the cells, which were subjected to DNA extraction as suggested by Andrigetto et al. (3) and modified by using only lysozyme (50 mg/ml; Sigma) for bacterial cell wall digestion.

Identification of LAB isolates.

Gram staining and catalase testing were used to screen the isolates and identify the strains belonging to the LAB group. LAB were then identified by molecular methods by PCR-DGGE, as described by Cocolin et al. (10). Strains with the same DGGE profiles were grouped, and representatives of each group were amplified with primers P1 and P4, as described by Klijn et al. (20), targeting 700 bp of the V1-V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene (rDNA). After purification, products were sent to a commercial facility for sequencing (MWG Biotech, Edersberg, Germany). Sequences were aligned with those in GenBank with the Blast program (1) to determine the closest known relatives of the partial 16S rDNA sequence obtained.

Direct extraction of nucleic acids from sausages.

From each sampling point, 10-g samples, in triplicate, were homogenized in a stomacher bag with 20 ml of saline-peptone water for 1 min. Big debris was allowed to deposit for 1 min, and 2 ml of supernatant was split into two 1-ml aliquots in screw-cap tubes containing 0.3 g of glass beads, one for DNA and one for RNA extraction. They were subjected to centrifugation at 4°C for 10 min at 14,000 × g to pellet the cells, which were resuspended in 150 μl of proteinase K buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM EDTA [pH 7.5], 0.5% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate). Twenty-five microliters of proteinase K (25 mg/ml; Sigma) was added, and a 65°C treatment was performed for 1.5 h. After this step, 150 μl of 2× breaking buffer (4% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 2% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate, 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris [pH 8], 2 mM EDTA [pH 8]) was mixed in the tubes. Three hundred microliters of phenol-chloroform (5:1, pH 4.7; Sigma) for RNA extraction and 300 μl of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, pH 6.7; Sigma) for DNA extraction were added to the tubes. Then, three 30-s treatments at the maximum speed, with an interval of 10 s each, were performed in a bead beater (Fast Prep; Bio 101, Vista, Calif.). The tubes were then centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, and the aqueous phase was precipitated with 1 ml of ice-cold absolute ethanol. The DNA and RNA were collected at 14,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, and the pellets were dried under a vacuum at room temperature. Fifty microliters of sterile water was added, and a 30-min period at 45°C was used to facilitate the nucleic acid solubilization. One microliter of DNase-free RNase (Roche Diagnostics, Milan, Italy) and 1 μl of RNase-free DNase (Roche Diagnostics) were added to digest, respectively, RNA and DNA by incubation at 37°C for 1 h. The RNA solution was checked for the presence of residual amounts of DNA by performing PCR amplification. When positive signals were detected, the DNase treatment was repeated to eliminate the DNA.

PCR and RT-PCR protocol.

Bacterial DNA was amplified with primers P1, 5′-GCG GCG TGC CTA ATA CAT GC-3′, and P2, 5′-TTC CCC ACG CGT TAC TCA CC-3′ (20), in a reaction mixture containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 1.25 U of Taq polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Milan, Italy) and 0.2 μM concentrations of each primer. Two microliters (50 ng total) of template DNA was added to the mixture. Amplifications were carried out in a Minicycler (Genenco, Florence, Italy) in a final volume of 50 μl by using an amplification cycle characterized by an initial touchdown step in which the annealing temperature was lowered from 60 to 52°C in intervals of 2°C every two cycles, and 20 additional cycles were done with annealing at 50°C. A denaturation of 95°C for 1 min was used, and extension was performed at 72°C for 1.5 min. A final extension of 72°C for 5 min ended the amplification cycle. For yeast DNA amplification, primers NL1, 5′-GCC ATA TCA ATA AGC GGA GGA AAA G-3′, and LS2, 5′-ATT CCC AAA CAA CTC GAC TC-3′ (9), were used. PCR was performed in a final volume of 50 μl containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1.25 U of Taq polymerase (Applied Biosystems), and 0.2 μM concentrations of each primer. Two microliters (50 ng total) of template DNA was added to the mixture. Reactions were run for 30 cycles: denaturation was at 95°C for 60 s, annealing was at 52°C for 45 s, and extension was at 72°C for 60 s. An initial denaturation at 95°C and a final 7-min extension at 72°C were used. Five microliters of each PCR product was analyzed by electrophoresis in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) agarose gel. A GC clamp (5′-CGC CCG CCG CGC CCC GCG CCC GTC CCG CCG CCC CCG CCC G-3′) was added to primers P1 and NL1 when used for DGGE analysis (34). RT-PCR was performed with the Tth DNA polymerase (Roche Diagnostics). One microgram of total RNA was mixed with 450 nM concentrations of each primer (P1-P2 for bacteria and NL1-LS2 for yeasts), and the volume was brought to 25 μl with DNase- and RNase-free sterile water. After a denaturation step at 70°C for 5 min, the tubes were placed immediately on ice and 25 μl of a mixture containing 25 mM bicine-KOH (pH 8.2), 57.5 mM potassium acetate, 4% (vol/vol) glycerol, 2.5 mM manganese acetate, and 5 U of Tth DNA polymerase was added. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 60°C, and after a 95°C for 2 min step, the amplification cycle described above (for bacteria and yeasts, accordingly) was carried out. Agarose gel electrophoresis in 0.5× TBE was used to assess the presence of the PCR product.

DGGE analysis.

The Dcode universal mutation detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) was used for DGGE analysis. For PCR products obtained with the primers P1-P2, electrophoresis was performed in a 0.8-mm-thick polyacrylamide gel (8% [wt/vol] acrylamide-bisacrylamide [37.5:1]) with a denaturant gradient from 40 to 60% (100% corresponded to 7 M urea and 40% [wt/vol] formamide) increasing in the direction of the electrophoretic run. Amplicons obtained with the primers NL1-LS2 were analyzed in denaturant gradient from 30 to 60%. Gels were subjected to a constant voltage of 120 V for 4 h at 60°C, and after the electrophoresis, they were stained for 20 min in 1.25× Tris-acetate-EDTA containing 1× SYBR Green (final concentration; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.). They were visualized under UV, digitally captured, and analyzed by using the GeneGenius BioImaging System (SynGene, Cambridge, United Kingdom) for the recognition of the bands present.

Sequencing of DGGE bands and sequence analysis.

Blocks of polyacrylamide gels containing selected DGGE bands were punched by sterile pipette tips. The blocks were then transferred in 50 μl of sterile water, and the DNA of the bands was left to diffuse overnight at 4°C. Two microliters of the eluted DNA was used for the reamplification, and the PCR products, generated with the GC clamped primer, were checked by DGGE with amplified sausage DNA or RNA as a control. Only products migrating as a single band and at the same position with respect to the control were amplified with the primer without the GC clamp, purified, and sent for sequencing to MWG Biotech. Searches in GenBank with the Blast program (1) were performed as described above.

RAPD analysis.

One hundred nanograms of the DNA extracted from isolated LAB strains was subjected to RAPD-PCR with primer M13 (5′-GAG GGT GGC GGT TCT-3′) as previously reported (3). Reactions were carried out in a final volume of 50 μl containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM (each) dNTPs, 1 μM primer, and 1.25 U of Taq polymerase (Applied Biosystems). The amplification cycle was as follows: 35 repetitions of 94°C for 1 min, 38°C for 1 min, ramp to 72°C at 0.6°C/s, and 72°C for 2 min. An initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min were carried out, too. RAPD-PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gels in 0.5× TBE at 120 V for 4 h. Gels were stained in 0.5× TBE buffer containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide (Sigma)/ml for 20 to 30 min. Pictures of the gels were digitally captured by the GeneGenius BioImaging System (SynGene), and Gel Compare, version 4.1 (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium) was used for pattern analysis. The calculation of similarities in the profiles of bands was based on the Pearson product moment correlation coefficient. Dendrograms were obtained by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages clustering algorithm (36). LAB isolates were subjected to RAPD-PCR analysis at least twice.

rep-PCR analysis.

The rep-PCR DNA fingerprinting kit (Bacterial BARCodes, Inc., Houston, Tex.) was used to carry out rep-PCR on the isolated LAB strains. Twenty-five-microliter reaction mixtures contained 2.5 μl of 5× buffer, 1.25 mM (each) dNTPs, 0.16 μg of bovine serum albumin, 10% dimethyl sulfoxide, 12 ng of primer Dt (Bacterial BARCodes), and 2 U of Taq polymerase (Applied Biosystems). After the addition of the DNA (100 ng, extracted as previously described), the tubes were placed in a MJ Minicylcer (Genenco) and amplified for 31 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 3 s followed by a step at 92°C for 30 s, annealing at 40°C for 1 min, and extension at 65°C for 8 min. The initial denaturation was at 95°C for 2 min, and the final extension was at 65°C for 8 min. Amplicons were separated in a 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gel in 0.5× TBE at 120 V for 6 h. After the run, gels were stained in TBE buffer with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml; Sigma) for 20 to 30 min. Pictures of the gels were analyzed with the pattern analysis software package Gel Compare, version 4.1 (Applied Maths). The Pearson product moment correlation coefficient was used to calculate the similarities in the patterns, and dendrograms were obtained by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages. Duplicate analyses were performed for the LAB strains isolated at the different points of sampling.

RESULTS

Traditional plating and pH measurements.

The results obtained by the traditional enumeration of microorganisms and the pH values of the fresh sausages during the 10 days of storage at 4°C are shown in Table 2. At day 0, the mix for the sausage preparation presented a total bacterial count, Micrococcaceae, and LAB population of about 104 CFU/g, and fecal enterococci, enterobacteria (excluding E. coli), and E. coli showed counts between 50 and 102 CFU/g. Numbers of yeasts and molds were less than 102 CFU/g. The main changes in the populations during the first 3 days involved the increase of total bacterial count and LAB count to 107 CFU/g and of Micrococcaceae and yeast counts to 106 and 105 CFU/g, respectively. Also fecal enterococci, enterobacteria, and E. coli showed an increase reaching 103, 104, and 102 CFU/g, respectively. The ecology of the fresh sausages remained almost unmodified at 6 days of storage; only yeasts grew to 106 CFU/g. At 10 days, the total bacterial count and LAB count remained constant at 107 CFU/g, and the Micrococcaceae count decreased to 105 CFU/ml. Fecal enterococci and enterobacteria reached values of about 105 CFU/ml, and yeasts and E. coli counts were almost similar to those at 6 days. S. aureus and mold counts were less than 102 CFU/g throughout the storage period. The pH showed an initial value of 5.61 ± 0.07, and it did not change significantly during the experimentation. The pH was 5.70 ± 0.04 at 3 days, 5.63 ± 0.01 at 6 days, and 5.60 ± 0.07 at 10 days (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Microbial counts, determined by plating, during storage of fresh sausagesa

| Organism(s) | Count (log10 CFU/g) on day of storageb:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0

|

3

|

6

|

10

|

|||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Total bacteria | 4.00 | 0.00 | 6.91 | 0.33 | 6.78 | 0.01 | 7.21 | 0.21 |

| LAB | 3.68 | 0.17 | 5.11 | 0.37 | 6.44 | 0.31 | 7.41 | 0.10 |

| Micrococcaceae | 3.22 | 0.10 | 6.74 | 0.14 | 6.19 | 0.47 | 5.09 | 0.70 |

| Yeasts | <100 | NA | 5.11 | 0.20 | 5.96 | 0.10 | 5.86 | 0.08 |

| Molds | <100 | NA | <100 | NA | <100 | NA | <100 | NA |

| Fecal enterococci | 2.00 | 0.00 | 2.45 | 0.08 | 2.10 | 0.61 | 5.53 | 0.31 |

| Total enterobacteria (without E. coli) | 0.77 | 0.68 | 3.52 | 0.18 | 4.27 | 0.24 | 5.06 | 0.44 |

| E. coli | 1.23 | 0.40 | 1.48 | 0.44 | 1.25 | 0.07 | 1.80 | 0.34 |

| S. aureus | 2.26 | 0.24 | <100 | NA | <100 | NA | <100 | NA |

pH values were as follows (standard deviations are given in parentheses): day 0, 5.61 (0.07); day 3, 5.70 (0.04); day 6, 5.63 (0.02); day 10, 5.60 (0.08).

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Identification of LAB isolates.

At each sampling point, about 20 to 30 strains of LAB were isolated and identified. A total of 80 isolates showed gram-positive staining and were catalase negative. Primary differentiation and grouping of the strains was performed by PCR-DGGE analysis of the V1 region of the 16S rDNA. Sixty-nine strains showed the same DGGE mobility, and the remaining 11 were different (data not shown). Subsequently, with sequencing and alignment of the 16S rDNA PCR product generated with primer pair P1-P4 (20), the 11 strains with different DGGE profiles were identified as follows: 1 Leuconostoc mesenteroides strain isolated on day 3 and 1 Enterococcus casseliflavus strain, 3 Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis strains, and 6 Lactobacillus casei strains isolated on day 0. From the 69 strains with identical DGGE patterns, 10 were sent for sequencing and all had 100% homology with Lactobacillus sakei 16S rDNA. On the basis of these results, all 69 isolates were identified as L. sakei.

Direct analysis by DGGE.

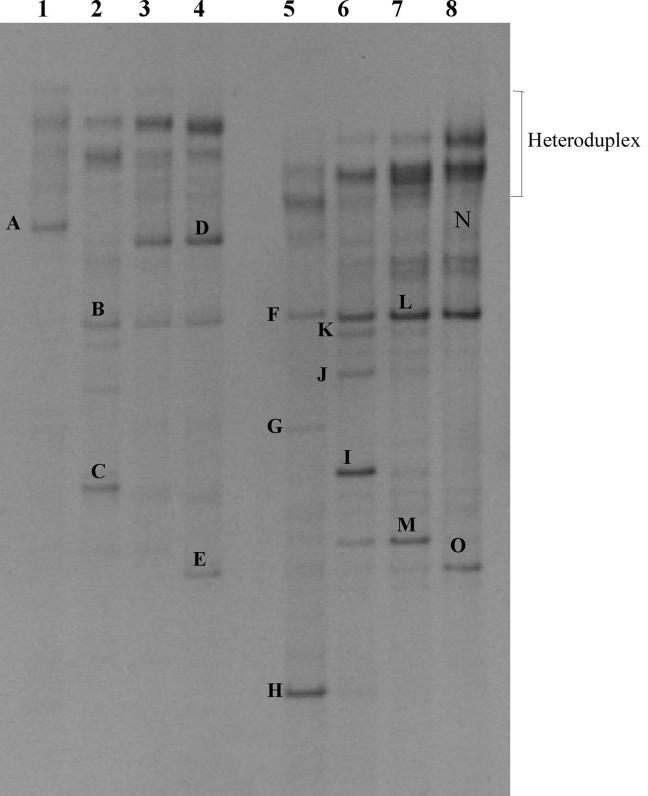

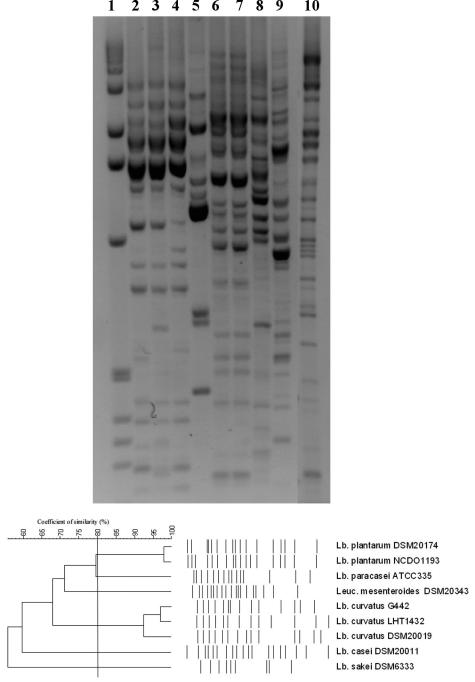

The results obtained from the direct analysis of the fresh sausage ecology by DGGE are reported in Fig. 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows the patterns of the PCR products obtained with the primer pair P1-P2 for the amplification of bacterial DNA and RNA, whereas Fig. 2 reports the DGGE profiles of yeast DNA and RNA amplified with primer pair NL1-LS2. Bands marked with letters in Fig. 1 and 2 were sequenced after reamplification, and the relative identification obtained by alignment in GenBank is reported in Table 3.

FIG. 1.

Bacterial DGGE profiles of DNA (lanes 1 to 4) and RNA (lanes 5 to 8) extracted directly from fresh sausage. Lanes 1 and 5, day 0; lanes 2 and 6, day 3 of storage; lanes 3 and 7, day 6 of storage; lanes 4 and 8, day 10 of storage. Bands indicated by letters were excised and, after reamplification, subjected to sequencing.

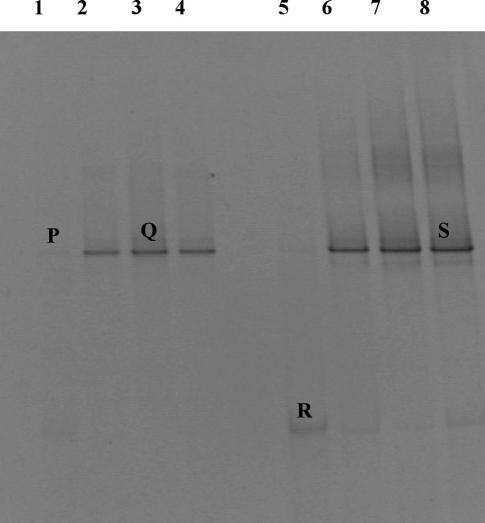

FIG. 2.

Yeast DGGE profiles of DNA (lanes 1 to 4) and RNA (lanes 5 to 8) extracted directly from fresh sausage. Lanes 1 and 5, day 0; lanes 2 and 6, day 3 of storage; lanes 3 and 7, day 6 of storage; lanes 4 and 8, day 10 of storage. Bands indicated by letters were excised and, after reamplification, subjected to sequencing.

TABLE 3.

Sequencing results of bands cut from DGGE gels

| Banda | Size (bp) | Closest relative | % Identity | Sourceb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 113 | L. curvatus | 100 | AY204894 |

| B | 93 | B. thermosphacta | 99 | M58798 |

| C | 93 | S. xylosus | 99 | AY227262 |

| D | 115 | L. sakei | 100 | AY204898 |

| E | 94 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | AF323676 |

| F | 93 | B. thermospacta | 99 | M58798 |

| G | 93 | Bacillus sp. | 99 | AY159884 |

| H | 78 | Uncultured bacterium | 99 | AF392785 |

| K | 93 | Uncultured Staphylococcus sp. | 99 | AF467428 |

| J | 93 | Uncultured Staphylococcus sp. | 99 | AF467428 |

| I | 93 | S. xylosus | 99 | AY227262 |

| L | 93 | B. thermosphacta | 99 | M58798 |

| M | 93 | Uncultured Staphylococcus sp. | 99 | AF467428 |

| N | 115 | L. sakei | 100 | AY204898 |

| O | 94 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides | 99 | AF323676 |

| P | 248 | D. hansenii | 100 | AF485980 |

| Q | 248 | D. hansenii | 100 | AF485980 |

| R | 276 | C. mansonii | 100 | AY004338 |

| S | 248 | D. hansenii | 100 | AF485980 |

As shown in Fig. 1, the DGGE profiles obtained from the RNA were richer in bands than the ones obtained from the DNA. In this last case, the main populations detected were represented by three species of LAB, Brochothrix thermosphacta and Staphylococcus xylosus. At day 0 only one band, referred to Lactobacillus curvatus (Fig. 1, lane 1) was visible. It was not present at day 3, when other bands were detected. Band B was present throughout the rest of the period, and band C was visible only at day 3. Bands B and C (Fig. 1, lane 2) were identified as B. thermosphacta and S. xylosus, respectively. After 6 days of storage at 4°C, a new strong band was detected in the gel, band D (Fig. 1, lane 3). It remained constant for the rest of the monitoring period with the same intensity and was identified as L. sakei. At day 10, Leuconostoc mesenteroides also showed up as band E (Fig. 1, lane 4). The overall picture of the fresh sausage ecology was respected when RNA was analyzed. As already mentioned, the profiles became richer as new bands were detected at the different sampling points. B. thermosphacta (Fig. 1, lanes 5 and 7, bands F and L) was the only species present throughout the whole monitoring period. No L. curvatus band was detected at day 0, and L. sakei was detected as a very faint band from the beginning of the storage (Fig. 1, lane 8, band N). Band I (Fig. 1, lane 6) and band O (Fig. 1, lane 8) corresponded to bands C and E, respectively, and they were identified, as mentioned already, as S. xylosus and Leuconostoc mesenteroides. Band G (Fig. 1, lane 5) was identified as Bacillus sp., and it was present only at day 0. Bands K, J, and M (Fig. 1, lanes 6 and 7) were characterized by an intense signal only when the RNA was processed. At day 3, faint K and J bands were present at the DNA level (Fig. 1, lane 2), but they were strong only when the RNA was amplified. All three of these bands referred to an uncultured Staphylococcus sp. At last, band H (Fig. 1, lane 5), present only at day 0, was identified as an uncultured bacterium. The heteroduplex signals were identified by reamplification of the cut bands and DGGE analysis.

In Fig. 2, the profiles of the yeast populations present in the fresh sausages are reported. As shown, only two bands, of which only one was present at day 0 in the RNA profiles, were present. Bands P, Q, and S (Fig. 2, lanes 1, 3, and 8) were identified as Debaryomyces hansenii, and band R (Fig. 2, lane 5) was identified as Capronia mansonii. D. hansenii was the yeast species that characterized the whole monitoring period. Only at day 0 did it show very faint bands hardly visible in the gel, for both DNA and RNA (Fig. 2, lanes 1 and 5).

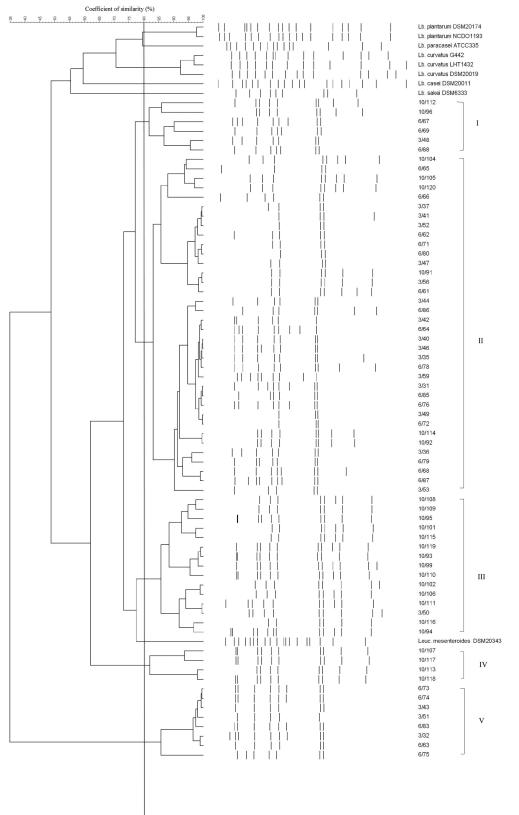

Molecular characterization of L. sakei populations.

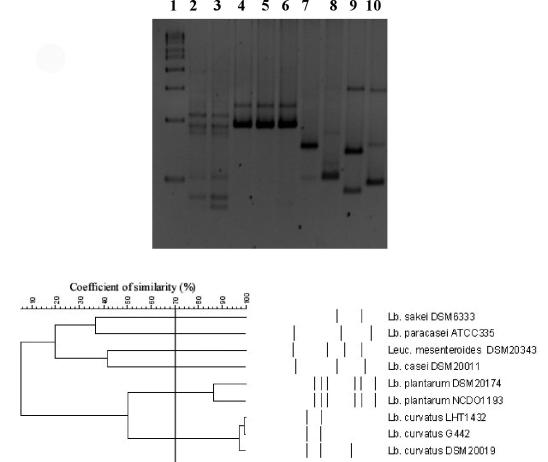

The strains belonging to L. sakei, isolated during the storage of the fresh sausages, were subjected to RAPD-PCR and rep-PCR. To choose the similarity coefficient to use for the discrimination in the cluster analysis, the control strains reported in Table 1 were amplified and the profiles were analyzed.

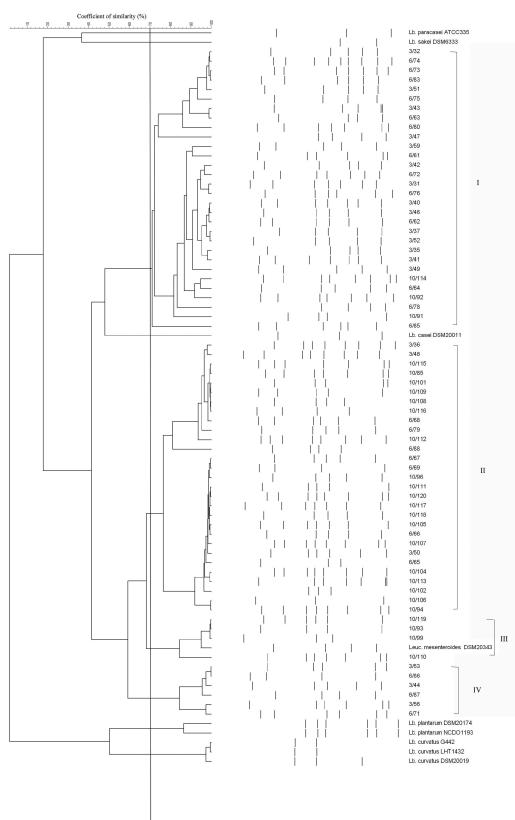

The RAPD-PCR profiles and the cluster analysis of the control strains are reported in Fig. 3. As shown, a similarity coefficient of 70% was chosen because it allowed discrimination of clusters of strains or single strains belonging to different species. When this similarity coefficient was applied to the cluster analysis obtained from the 69 L. sakei isolates, 4 groups of strains were identified (Fig. 4). Two major clusters, marked I and II, contained almost all of the strains (30 isolates in cluster I and 29 isolates in cluster II). Two more clusters, III and IV, were obtained by grouping 4 and 6 strains, respectively. Clusters I and IV were formed by strains isolated from day 3 and day 6, whereas cluster II grouped 19 strains isolated at day 10, 7 strains isolated at day 6, and 3 strains isolated at day 3. Four strains isolated at day 10 were grouped in cluster III together with Leuconostoc mesenteroides DSM20343.

FIG. 3.

RAPD-PCR profiles and relative cluster analysis of the control LAB species used in the study. Lane 1, 1-kb molecular ladder (Sigma); lane 2, L. plantarum DSM20174; lane 3, L. plantarum NCDO1193; lane 4, L. curvatus DSM20019; lane 5, L. curvatus LHT1432; lane 6, L. curvatus G442; lane 7, L. sakei DSM6333; lane 8, Leuconostoc mesenteroides DSM20343; lane 9, L. casei DSM20011; lane 10, L. paracasei ATCC 335. A similarity coefficient of 70% was chosen to guarantee species identification. Abbreviations: Lb., Lactobacillus; Leuc., Leuconostoc.

FIG. 4.

RAPD-PCR cluster analysis of profiles obtained from L. sakei strains isolated from fresh sausages during storage. The first number on the strain code represents the day of isolation, and the second number represents the progressive number of isolation. Control strains used in the study are included as well. Identified clusters are indicated by roman numerals. Abbreviations: Lb., Lactobacillus; Leuc., Leuconostoc.

The rep-PCR patterns and the cluster analysis of the control strains are reported in Fig. 5. A similarity coefficient of 80%, higher than the one used for RAPD-PCR analysis, was selected to guarantee the discrimination of the species considered in the study. The application of this similarity coefficient to the cluster analysis of the isolated strains led to the identification of 5 clusters (Fig. 6). Clusters I, II, and V were characterized by strains isolated throughout the monitoring period, and cluster III contained mainly isolates from the 10th day (14 of 15 strains). All the remaining strains from the 10th day were grouped in cluster IV.

FIG. 5.

rep-PCR profiles and relative cluster analysis of the control LAB species used in the study. Lane 1, 1-kb molecular ladder (Sigma); lane 2, L. curvatus G442; lane 3, L. curvatus LHT1432; lane 4, L. curvatus DSM20019; lane 5, L. sakei DSM6333; lane 6, L. plantarum DSM20174; lane 7, L. plantarum NCDO1193; lane 8, L. casei DSM20011; lane 9, L. paracasei ATCC 335; lane 10, Leuconostoc mesenteroides DSM20343. A similarity coefficient of 80% was chosen to guarantee species identification. Abbreviations: Lb., Lactobacillus; Leuc., Leuconostoc.

FIG. 6.

rep-PCR cluster analysis of profiles obtained from L. sakei strains isolated from fresh sausages during storage. The first number on the strain code represents the day of isolation, and the second number represents the progressive number of isolation. Identified clusters are indicated by roman numerals. Control strains used in the study are included as well. Abbreviations: Lb., Lactobacillus; Leuc., Leuconostoc.

DISCUSSION

Fresh sausages are a highly perishable product because of their characteristics in pH and Aw. They have a shelf life of 10 days when stored at 4°C, and they are cooked prior to consumption. The microbiology of fresh sausage has been studied only marginally, and the information available underlines how this traditional product is characterized by the presence of mesophilic and psychrotrophic microorganisms, and in case of low hygienic conditions, of pathogens, which can create outbreaks in the case of consumption of sausages that are not well cooked (40). Since no more detailed studies focusing on the ecology of fresh sausages are available, a polyphasic approach, with culture-dependent and -independent methods, was chosen to investigate the population dynamics of this product. Traditional plating and isolation of LAB strains and direct extraction of DNA and RNA, followed by amplification and DGGE analysis, were performed to profile the main populations able to develop during the 10 days of shelf life of the product studied.

The ecology study was performed by DGGE analysis of the PCR products obtained from the V1 region of the 16S rDNA for bacteria and the D1-D2 loop of the 26S rDNA for yeasts. The approach used has been previously applied to study the ecology of sea sediments (25), hot springs (13, 39), wastewater treatment plants (15), and more recently, gastrointestinal contents (17, 38, 42). In the last few years, an increasing interest in this method has been manifested by researchers in the field of food microbiology to study the dynamic changes occurring during food fermentations or to profile microbial pathogens in food samples. Studies of Mexican pozol (4), artisanal Sicilian cheese (31), sourdough fermentation (21), malt whisky fermentation (35), wine fermentation (23), Mozzarella cheese (12), and fermented sausages (10) exploiting the potential of PCR-DGGE method are already available. Moreover, the application of this method to identify Listeria spp. and Listeria monocytogenes directly in food samples has been recently published (11).

In this study, fresh sausages were prepared in a local laboratory by traditional procedures, immediately chilled at 4°C, and stored for a total period of 10 days. Samples at days 0, 3, 6, and 10 day were collected and subjected to traditional and molecular analysis. Moreover, LAB strains were isolated at each sampling point and, after DNA extraction, characterized by RAPD-PCR and rep-PCR.

The traditional plating results underlined very clearly the microbiological situation of the product during storage (Table 2). It was mainly characterized by an initial increase in total bacterial count, LAB population, and Micrococcaceae count. After the third day of storage, the spoilage microorganisms, such as enterobacteria and fecal enterococci, increased in number, reaching a final count of about 105 CFU/g and 106 CFU/g, respectively. During the 10 days of monitoring, another significant change in the microbial flora was related to the growth of yeasts. From a value of less than 102 CFU/g at day 0, they reached about 106 CFU/g at the end of the experimentation. The counts obtained at 10 days should be considered typical of a spoiled product. The pH values remained stable throughout the period, although LAB, able to produce organic acids, reached values of 107 CFU/ml. This evidence could be explained by a reduced capability of LAB to acidify due to the low storage temperature used and by a potential buffering capability of the end products of the metabolism of enterobacteria and fecal enterococci, such as ammonia, as well as free amino acids produced from proteolytic activity of yeast species present in the fresh sausages (33).

Eighty LAB strains were isolated at different points of sampling, and after Gram staining and catalase testing, they were subjected to molecular identification and characterization. The PCR-DGGE profiles underlined how only 11 isolates moved differently in the gel compared to the remaining 69 strains. From these 11 strains, 10 were isolated at day 0 and were Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis, L. casei, and E. casseliflavus and 1 strain isolated at day 3 was Leuconostoc mesenteroides. The rest of the isolates, from the 3rd, 6th, and 10th days of storage, were all determined, by PCR-DGGE analysis and sequencing of 10 representative strains, to be L. sakei.

An interesting picture of the fresh sausage ecology was obtained when molecular methods were applied to DNA and RNA extracted directly from the sample. Two sets of primers, one for the amplification of bacterial DNA and RNA and a second for the amplification of yeast nucleic acids, were used to profile the main populations present in the product during storage. Bacterial DGGE profiles were characterized, for both DNA and RNA, by the presence of a constant band throughout the process that was B. thermosphacta, whereas Lactobacillus spp., visible at the DNA level, were only marginally present at the RNA level (Fig. 1). An L. curvatus signal was detected in the gels at day 0, but it was not present at the RNA level. In addition, no isolates belonged to this species. This evidence could lead to the conclusion that dead cells, present in the meat, generated a band from DNA not completely degraded. Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis, L. casei, and E. casseliflavus, isolated at day 0, did not give a specific band at either the DNA or RNA level, meaning that the relative populations were below the detection limit of 104 CFU/g, as described previously (10). The same assumption can be used to explain the isolation of Leuconostoc mesenteroides at day 3 while no specific band was present in the DGGE gels. Only at day 10 did a signal at both the DNA and RNA levels become visible, underlining an increase in the Leuconostoc mesenteroides population. Beginning on the sixth day, a clear band became visible in the DNA DGGE gels which remained stable. It was L. sakei, which was the main LAB isolated by traditional methods. While the DNA signal was pretty strong, the RNA band belonging to this species was very faint from the very beginning of the monitoring period. This fact could be explained by the masking effects of L. sakei RNA during RT-PCR by B. thermosphacta populations. On the fresh mix, other bacteria were identified. A Bacillus sp. strain was identified at the RNA level only, and a strong band, migrating at the bottom of the gel, was defined as an uncultured bacterium by direct sequencing. Staphylococcus spp., responsible for lipolysis during the fermentation of sausages, were detected also during storage of the fresh sausages studied. An S. xylosus band was recognized at day 3 at the DNA and RNA levels, whereas three Staphylococcus sp. bands, defined as uncultured Staphylococcus sp. after sequencing, were mainly visible at the RNA level.

When yeast DNA and RNA were processed by PCR-DGGE and RT-PCR-DGGE, the patterns obtained were much more simple than the bacterial DGGE profiles (Fig. 2). One main population recognized as D. hansenii was present as a very faint band at day 0 but then established itself during storage. The D. hansenii-specific band remained stable at both the DNA and RNA levels. Only at day 0 was a lower band visible in the RT-PCR-DGGE, which was C. mansonii, but it was not detected yet at day 3. In previous studies, D. hansenii has shown good potential for the hydrolysis of sarcoplasmic proteins and the generation of several polar and nonpolar peptides and free amino acids (33). Here, it can be recognized as an agent responsible for the absence of pH drop observed during the storage.

The study of fresh sausages by a multiphasic approach with culture-dependent and -independent methods allowed us to obtain a complete picture of the ecology of the product. Moreover, differences in the microbial populations more present, and those that were more metabolically active were observed. Counts on agar plates underlined how LAB were the main bacteria present in the sausages, showing a relevant increase between the third and sixth days of storage. They were characterized by a count of 108 CFU/g at the end of the monitoring period. Also, Micrococcaceae organisms showed a fast increase in the counts in the first days of storage, but after 3 days they started to decrease constantly. More precise ecology information was obtained when the results of the culture-independent methods were considered. DNA DGGE analysis highlighted the presence of L. curvatus, L. sakei, and Leuconostoc mesenteroides as LAB representatives, S. xylosus as member of the Micrococcaceae family, and B. thermosphacta, which was detected on day 3 of storage and remained stable until the end of the monitoring period. Its presence assumes even more importance when the results of the RNA DGGE are taken into consideration. A B. thermosphacta-specific band was detected in the gel at day 0 as a faint band, but its intensity increased during the storage, pointing out that the B. thermosphacta population was one of the most active populations in the product considered in the study. LAB activity was only marginally detected, and it referred to strains of L. sakei and Leuconostoc mesenteroides. An important aspect of the ecology of the fresh sausages, acquired by RNA DGGE analysis, was the presence of active populations of Staphylococcus spp. on day 3 of storage. S. xylosus and an uncultured Staphylococcus sp. were detected in the gels, representing the most active populations at day 3 together with B. thermosphacta. The specific DGGE signals for the uncultured Staphylococcus sp. were not present at the DNA level, and this can be explained by considering the masking effects of DNA extracted from more abundant populations during the amplification step. Considering the yeast populations, the results of the plate counts correlated well with the profiles obtained by DNA and RNA DGGE. Only at day 0, when the yeast counts were below 100 CFU/g, no signal was detected for the DNA and a very faint band was visible at the RNA level. From the third day of storage, when yeast concentrations increased to 105 CFU/g, one clear band was visible in the gels. DNA DGGE profiles were identical to RNA profiles, indicating that D. hansenii was not only the main yeast population present but also the main one active.

Lastly, the 69 strains of L. sakei isolated during the monitoring period were studied to detect different populations that eventually developed on different days of storage. RAPD-PCR and rep-PCR were used for the genetic characterization of the isolates. RAPD-PCR is a well-established method for strain characterization (3, 7), but since the resulting band patterns often exhibit a poor reproducibility (22, 28), rep-PCR, recently used for Lactobacillus species identification (14), was also used. Prior to the analysis, reference strains belonging to different species of Lactobacillus (Table 1) were subjected to the PCR amplifications and patterns were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis. After digitalization of the pictures and analysis of the profiles with dedicated software, a 70% similarity coefficient for RAPD-PCR and an 80% similarity coefficient for rep-PCR were chosen as suitable to discriminate all Lactobacillus spp. that were used as controls. When the methods described were applied to the isolates, different clusters of strains were defined. Using RAPD-PCR, 4 clusters were generated (Fig. 4), and using rep-PCR, 5 clusters were created (Fig. 6). Surprisingly, in the RAPD-PCR analysis, cluster III grouped together the control strain Leuconostoc mesenteroides DSM20343 and 4 strains isolated at day 10. To eliminate any doubt related to mistakes in the identification of strains by PCR-DGGE analysis, strains 10/93, 10/99, 10/110, and 10/119 were subjected to PCR with primer pair P1-P4 and sent for sequencing. They all showed high homology (<99%) to the 16S rDNA of L. sakei (data not shown). The results obtained from the cluster analysis led to the conclusion that L. sakei strains belonged to different populations, since strains isolated at 10 days created, in both PCR analyses, separate clusters. It is possible that during storage a selection due to the low temperature occurred, and only strains more resistant grew and dominated in the product. This is an important factor to take into consideration in developing LAB as starters for fresh sausages. Since the storage temperature of the fresh sausages is 4°C or below, strains added should be able to immediately produce acids to preserve the product, avoiding outgrowth of the spoilage microflora and controlling, at the same time, food-borne pathogens eventually present, such as Listeria monocytogenes, possibly coming from in the raw materials.

The information collected underlines once more the importance of the use of a polyphasic approach to study the ecology of a specific ecosystem. Here, the application of traditional methods and the identification and characterization of the LAB isolates led to the understanding that between the same species, different populations took over during the monitoring period, selected on the basis of their resistance to temperature. Moreover, the direct analysis of DNA and RNA highlighted that LAB were not the main population present, since B. thermosphacta was detected throughout the period for both DNA and RNA analysis. Interestingly, at the RNA level, an uncultured bacterium and uncultured Staphylococcus sp. were identified as well. This evidence lead to the conclusion that fresh sausage may contain as-yet-unidentified bacterial species.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ministry of University, Rome, Italy, action PRIN (ex 40%).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Shaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, L. 1997. Bioprotective cultures for fresh sausages. Fleischwirtschaft 77:635-637. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrigetto, C., L. Zampese, and A. Lombardi. 2001. RAPD-PCR characterization of lactobacilli isolated from artisanal meat plants and traditional fermented sausages of Veneto region (Italy). Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 33:26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ben Omar, N., and F. Ampe. 2000. Microbial community dynamics during production of the Mexican fermented maize dough pozol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3664-3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berthier, F., and S. D. Ehrlich. 1999. Genetic diversity within Lactobacillus sakei and Lactobacillus curvatus and design of PCR primers for its detection using randomly amplified polymorphic DNA. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:997-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boles, J. A., V. L. Mikkelsen, and J. E. Swan. 1998. Effects of chopping time, meat source and storage temperatures on the colour of New Zealand type fresh beef sausages. Meat Sci. 49:79-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouton, Y., P. Guyot, E. Beuvier, P. Tailliez, and R. Grappin. 2002. Use of PCR-based methods and PFGE for typing and monitoring homofermentative lactobacilli during Comté cheese ripening. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 76:27-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casalinuovo, F., A. Cacia, A. Scognamiglio, and L. Bontempo. 2001. Microbiological aspects and main causes of contamination of some typical meat products. Ind. Aliment. XL:159-162. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cocolin, L., L. F. Bisson, and D. A. Mills. 2000. Direct profiling of the yeast dynamics in wine fermentations. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 189:81-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cocolin, L., M. Manzano, C. Cantoni, and G. Comi. 2001. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of the 16S rRNA gene V1 region to monitor dynamic changes in the bacterial population during fermentation of Italian sausages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5113-5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cocolin, L., K. Rantsiou, L. Iacumin, C. Cantoni, and G. Comi. 2002. Direct identification in food samples of Listeria spp. and Listeria monocytogenes by molecular methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:6273-6282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coppola, S., G. Blaiotta, D. Ercolini, and G. Moschetti. 2001. Molecular evaluation of microbial diversity occuring in different types of Mozzarella cheese. J. Appl. Microbiol. 90:414-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferris, S. Y., G. Muyzer, and D. M. Ward. 1996. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis profiles of 16S rRNA defined populations inhabiting hot spring microbial mat community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:340-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gevers, D., G. Huys, and J. Swings. 2001. Applicability of rep-PCR fingerprinting for identification of Lactobacillus species. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 205:31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godon, J. J., E. Zumstein, P. Dabert, F. Habouzit, and R. Moletta. 1997. Molecular microbial diversity of an anaerobic digestor as determined by small-subunit rDNA sequence analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2802-2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Head, I. M., J. R. Saunders, and R. W. Pickup. 1998. Microbial evolution, diversity and ecology: a decade of ribosomal RNA analysis of uncultivated microorganisms. Microb. Ecol. 35:1-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heilig, H. G. H. J., E. G. Zoetendal, E. E. Vaughand, P. Marteau, A. D. L. Akkermans, and W. M. de Vos. 2002. Molecular diversity of Lactobacillus spp. and other lactic acid bacteria in the human intestine as determined by specific amplification of 16S ribosomal DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:114-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hugenholtz, P., B. M. Goebel, and N. R. Pace. 1998. Impact of culture-independent studies on the emerging phylogenetic view of bacterial diversity. J. Bacteriol. 180:4765-4774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hugenholtz, P., and N. R. Pace. 1996. Identifying microbial diversity in the natural environment: a molecular phylogenetic approach. Trends Biotechnol. 14:90-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klijn, N., A. H. Weerkamp, and W. M. deVos. 1991. Identification of mesophilic lactic acid bacteria by using polymerase chain reaction-amplified variable regions of 16S rRNA and specific DNA probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:3390-3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meroth, C. B., J. Walter, C. Hertel, J. Brandt, and W. P. Hammes. 2003. Monitoring the bacterial population dynamics in sourdough fermentation process by using PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:475-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meunier, J. R., and P. A. D. Grimont. 1993. Factors affecting reproducibility of random amplified polymorphic DNA-fingerprinting. Res. Microbiol. 144:373-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mills, D. A., E. A. Johannsen, and L. Cocolin. 2002. Yeast diversity and persistance in botrytis-affected wine fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:4884-4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muyzer, G. 1999. DGGE/TGGE a method for identifying genes from natural ecosystems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:317-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muyzer, G., E. D. De Waal, and A. G. Uitterlinden. 1993. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:695-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muyzer, G., and K. Smalla. 1998. Application of denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TGGE) in microbial ecology. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 73:127-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers, R. M., T. Maniatis, and L. S. Lerman. 1987. Detection and localization of single base change by denaturing gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 155:501-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olive, D. M., and P. Bean. 1999. Principles and application of methods for DNA based typing of microbial organisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1661-1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pace, N. R. 1997. A molecular view of microbial diversity and the biosphere. Science 276:734-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pezzotti, G., R. Mioni, M. Grimaldi, and A. Ponzoni. 2001. Valutazione microbiologica di carni macinate e preparazioni di carne. Ingegneria Aliment. 16:18-26. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Randazzo, C. L., S. Torriani, D. L. Akkermans, W. M. deVos, and E. E. Vaughan. 2002. Diversity, dynamics, and activity of bacterial communities during production of an artisanal Sicilian cheese as evaluated by 16S rRNA analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1882-1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roller, S., S. Sagoo, R. Board, T. O'Mahony, E. Caplice, G. Fitzgerald, M. Fogden, M. Owen, and H. Fletcher. 2002. Novel combination of chitosan, carnocin and sulphite for the preservation of chilled pork sausages. Meat Sci. 62:165-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santos, N. N., R. C. Santos-Mendosa, Y. Sanz, T. Bolumar, M.-C. Aristoy, and F. Toldrà. 2001. Hydrolysis of pork muscle sarcoplasmatic proteins by Debaryomyces hansenii. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 68:199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheffield, V. C., D. R. Cox, L. S. Lerman, and R. M. Myers. 1989. Attachment of a 40-base pairs G+C rich sequence (GC clamp) to genomic DNA fragments by the polymerase chain reaction results in improved detection of single-base changes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:297-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Beek, S., and F. G. Priest. 2002. Evolution of the lactic acid bacterial community during malt whisky fermentation: a polyphasic study. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:297-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vauterin, L., and P. Vauterin. 1992. Computer-aided objective comparison of electrophoretic patterns for grouping and identification of microorganisms. Eur. Microbiol. 1:37-41. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Versalovic, J., M. Schneider, F. J. De Bruijn, and J. R. Lupski. 1994. Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence-based polymerase chain reaction. Methods Mol. Cell. Biol. 5:25-40. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walter, J., C. Hertel, G. W. Tannock, C. M. Lis, K. Munro, and W. P. Hammes. 2001. Detection of Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Leuconostoc, and Weissella species in human feces by using group-specific PCR primers and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2578-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ward, D. M., M. J. Ferris, S. C. Nold, and M. M. Bateson. 1998. A natural view of microbial biodiversity within hot spring cyanobacterial mat communities. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1353-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zambonelli, C., F. Papa, P. Romano, G. Suzzi, and L. Grazia. 1992. Microbiologia dei salumi. Edagricole, Bologna, Italy.

- 41.Zanardi, E., E. Novelli, G. P. Ghiretti, V. Dorigoni, and R. Chizzolini. 1999. Colour stability and vitamin E content of fresh and processed pork. Food Chem. 67:163-171. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zoetendal, E. G., A. D. L. Akkermans, and W. M. de Vos. 1998. Temperature gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of 16S rRNA from human fecal samples reveals stable and host-specific communities of active bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3854-3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]