Abstract

Objective:

To describe the evolution, training, and results of an emerging allied health profession skilled in eliciting sustainable health-related behavior change and charged with improving patient engagement.

Methods:

Through techniques sourced from humanistic and positive psychology, solution-focused and mindfulness-based therapies, and leadership coaching, Integrative Health Coaching (IHC) provides a mechanism to empower patients through various stages of learning and change. IHC also provides a method for the creation and implementation of forward-focused personalized health plans.

Results:

Clinical studies employing Duke University Integrative Medicine's model of IHC have demonstrated improvements in measures of diabetes and diabetes risk, weight management, and risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke. By supporting and enabling individuals in making major lifestyle changes for the improvement of their health, IHC carries the potential to reduce rates and morbidity of chronic disease and impact myriad aspects of healthcare.

Conclusion:

As a model of educational and clinical innovation aimed at patient empowerment and lifestyle modification, IHC is aligned well with the tenets and goals of recently sanctioned federal healthcare reform, specifically the creation of the first National Prevention and Health Promotion Strategy.

Practice Implications:

IHC may allow greater patient-centricity while targeting the lifestyle-related chronic disease that lies at the heart of the current healthcare crisis.

Key Words: Health coaching, behavior change, chronic disease prevention, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

摘要

目标:介绍一种新兴协联健康职 业在引导患者可持续地改变健康 相关行为、主导改善患者参与程 度上的进展、培训和成效。

方法: 综合健康辅导 (IHC) 利 用源自于人本主义心理学和积极 心理学的技术、关注解决疗法和 正念疗法,并进行领导力辅导而 确定了一种机制,赋予患者能力 以完成不同阶段的学习和改 变。IHC 还提供了一种方法,用 以创建和执行具前瞻性的个性化 健康计划。

成效: 该等临床研究采用杜克 大学综合医学的 IHC 模式,证 明对糖尿病和糖尿病风险、体重 控制以及心血管疾病和中风风险 的测量方法均已获改进。通过支 持并赋能有关人士为改善其健康 状况而做出重大生活方式改 变,IHC 有可能降低慢性疾病的 患病几率和发病率,并且影响健 康护理的多个方面。

结论:作为一个旨在进行患者赋 能和生活方式修正的教育和临床 创新模式,IHC 非常符合最近批 准的联邦健康护理改革的原则和 目标,尤其是在创建首个全国预 防和健康促进战略 (National Prevention and Health Promotion Strategy) 上。

实践意义: IHC 在针对与生活 方式相关且处于当前健康护理 危机核心之慢性疾病的同时, 可能允许更加注重患者的中心 性作用。

SINOPSIS

Objetivo:

Describir la evolución, la formación y los resultados de una profesión sanitaria asociada emergente capaz de lograr un cambio sostenible en las conductas relacionadas con la salud y que se encarga de mejorar el compromiso de los pacientes.

Métodos:

A través de técnicas procedentes de la psicología humanista y positiva, de terapias centradas en las soluciones y en la atención plena, así como del entrenamiento en liderazgo, la formación sanitaria integral (IHC, por sus siglas en inglés) proporciona un mecanismo para capacitar a los pacientes a lo largo de diversas etapas de aprendizaje y de cambio. La IHC proporciona un método para la creación y la implantación de planes sanitarios personalizados orientados al futuro.

Resultados:

Diversos estudios clínicos que han adoptado el modelo IHC de medicina integral de la Universidad de Duke han revelado mejoras en las mediciones relacionadas con la diabetes y el riesgo de diabetes, el control del peso, y el riesgo de enfermedades cardiovasculares y de accidentes cerebrovasculares. Al apoyar y permitir a los individuos introducir cambios importantes en el estilo de vida para mejorar su salud, la IHC conlleva un potencial para reducir los índices y la morbilidad por enfermedades crónicas, además de afectar a numerosos aspectos de la atención sanitaria.

Conclusiones:

Como modelo de innovación educativa y clínica dirigido a la capacitación de los pacientes y a la modificación del estilo de vida, la IHC concuerda bien con los principios y los objetivos de la reforma sanitaria federal recientemente aprobada, en particular con la creación de la primera Estrategia Nacional de Prevención y Promoción de la Salud estadounidense.

Implicaciones para la práctica clínica:

La IHC puede permitir el centrarse más en el paciente a la vez que aborda las enfermedades crónicas relacionadas con el estilo de vida que constituyen el centro de la crisis sanitaria actual.

INTRODUCTION

Lifestyle-related chronic disease lies at the heart of the current healthcare crisis in the United States and with it, a large gap between healthcare provider recommendations and sustainable patient action. An allied health professional skilled in the art of eliciting sustainable health-related behavior change and charged with improving patient engagement and activation is urgently needed. Along with an emerging number of other professional training programs (described below), the Integrative Health Coach Professional Training (IHCPT) program at Duke University was developed for this purpose. As a model of educational and clinical innovation aimed at patient empowerment and lifestyle modification, integrative health coaching (IHC) is aligned well with the tenets and goals of recently sanctioned federal healthcare reform, specifically the creation of the first National Prevention and Health Promotion Strategy.

Nearly 50 years ago, a need for greater consumer access to high-quality medical care sparked the development of a new allied healthcare profession, the physician assistant (PA). The nation's first three PAs graduated in 1967 from the PA training program at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, which is now considered the birthplace of PA training.1 Today, more than 80 000 nationally certified PAs work interdependently with physicians as an integral part of the health-care team, adding efficiency and quality in a wide variety of healthcare settings.2 More than 150 accredited training programs have been established at medical centers, colleges, and universities across the United States. With the backing of the medical community, an innovative solution to a system-wide shortcoming transformed the delivery of healthcare.3

Today, a critical problem facing the nation's health-care system is the prevalence of lifestyle-related chronic diseases. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has deemed chronic disease “the public health challenge of the 21st century.”4 Again, there is a need for creative solutions to daunting challenges. To that end, the pioneering of a new allied healthcare profession is again underway. The past 10 years have witnessed the birth and rapid expansion of IHC, which is poised to fill a hole in our current healthcare system and address the need for skilled professionals trained in the science and art of health-related behavior change.

AN OPENING FOR CHANGE

Failure of the Disease-care System

The complex challenges facing our current health-care system are well documented.5–8 Rates of preventable chronic disease have increased significantly in the last 3 decades and are expected to affect approximately 170 million Americans—more than half the population—by 2030.9 Further, the number of Americans with comorbidities is also on the rise; the proportion of US adults with three or more chronic conditions nearly doubled between 1996 (7%) and 2005 (13%).10

The significant rise in chronic disease rates has contributed to rapidly increasing national healthcare costs. The United States currently spends over $2 trillion annually on healthcare.11 In addition, the yearly cost of lost productivity due to chronic illness-related absenteeism from work is approximately $1 trillion.12 Among patients insured privately, through Medicaid, or through Medicare, expenditures for treatment of individuals with chronic disease comprise 74%, 83%, and nearly 100% of total healthcare expenditures, respectively.9 Without significant changes in our approach to care, annual healthcare expenditures are forecasted to reach $4.6 trillion by 2020.11

Three Key Contributors to a Chronic Disease Epidemic

Several key factors contributing to the present epidemic of chronic diseases have been well described. First, the design of our current healthcare delivery system, including its reimbursement structure, is heavily weighted toward management of disease events over the use of foresight, planning, and disease prevention.6,7,13 Attempts to improve outcomes and reduce costs using innovative disease management programs have proven to be financially unsustainable within a system that rewards hospitalizations and invasive procedures while penalizing outpatient care, risk management, and patient support.14,15 Financial incentives should be inclusive of interventions and technologies that achieve desired outcomes at earlier stages before the need arises for costly, invasive treatments often required at advanced stages of disease.

Second, the medical community frequently fails to take full advantage of scientific discoveries, specifically, an ever-expanding body of research that attests to the central role of lifestyle in the development of most chronic diseases.7 Decades of research have linked a variety of lifestyle factors—such as inactivity, the Western diet, smoking, and sustained stress response— with increased risk for major illnesses and death.4,16 Further, the burgeoning field of epigenetics is increasingly able to provide molecular substantiation of the critical roles of environment and behavior toward risk of chronic disease.17–19 Lacking an appropriate emphasis on lifestyle modification, the current healthcare model is not aligned with these and other data confirming lifestyle-related issues as arguably the major determinant of health.

Last, patients often lack a sense of motivation and authority to participate in their own care at the level required for lasting health.7 This phenomenon is gaining the attention of researchers and clinicians and has been termed low patient engagement and activation. “Patient engagement” refers to actions individuals must take in order to benefit from the healthcare system.20 “Patient activation” has been defined as the cultivation of knowledge, skills, and confidence to manage one's own health.21 Low patient engagement and activation stem from a wide range of internal and external barriers, including low awareness of risk, limited perspectives on possible improvements, distrust of providers, values conflicts, competing commitments, social pressures, and/or environmental obstacles at home or work. Physicians and other clinicians typically lack the necessary time and expertise to explore issues related to behavior change with patients.13 As a result, the need for a mechanism for successful, sustained patient engagement and activation—a crucial component of chronic disease prevention—is not met in the current system.22

Integrative Health Coaching Fills a Critical Gap

The field of IHC and the model developed at Duke Integrative Medicine answer the need for a new health-care professional skilled at the facilitation of patient engagement and activation. Key functions of IHC present tenable solutions to the aforementioned three flaws in the current system: (1) cultivation of foresight for proactive health planning, (2) a focus on lifestyle, and (3) a high degree of personalization, clarifying each person's vision, values, and linked goals while addressing internal and external obstacles to success. As such, IHC represents a major shift from the current medical paradigm and a venue for much needed change.23

DUKE INTEGRATIVE MEDICINE'S MODEL OF INTEGRATIVE HEALTH COACHING

The Rise of Health Coach Training

In recent years, a number of institutions have begun to offer training in health and wellness coaching using widely varying entry requirements, formats, curricula, and concentration of study and practice.24 Corporations may train their own coaches in the promotion of their own health-related product or package.25 Private programs such as Wellcoaches (Wellesley, Massachusetts) and Real Balance Global Wellness Services (Fort Collins, Colorado) offer a range of training in health promotion and wellness coaching while other programs such as the Bark Coaching Institute (San Francisco, California) and the National Institute of Whole Health (Wellesley Center, Massachusetts) offer coach training based on similar holistic principles described in this article.24,25 The first academic institution to offer in-depth health coach training using a whole-person model was the University of Minnesota (UMN) in 2005. UMN currently offers substantive coach training for non–degree seekers through a post-baccalaureate certificate and as a component of master's-level or doctorate-level coursework.25 Other academic institutions also offer coach training embedded within programs of graduate study toward master's degrees. For example, the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco offers multidisciplinary training including coaching toward a master of arts (MA) degree in integrative health studies. Likewise, coaching coursework is incorporated into the MA in holistic health education curriculum at John F. Kennedy University (Pleasant Hill, California).24 (See the Health Coaching Education Roundtable at www.gahmj.com for a broader discussion of educational initiatives in health and wellness coaching.)

Terminology Considerations in a New Field

In the medical literature, the term health coaching has been applied to a broad range of interventions aimed at improving health outcomes, from digital automated messages on the minimal end to a program of sessions with rigorously trained professionals skilled in individualized, patient-centered strategies for sustainable behavior change on the intensive end. With no current consensus on the definition of health coaching and wide variations in training, methodology, and scope of practice, a rigorous evidence base is lacking, and medical literature that exists on the subject is vulnerable to misinterpretation.26 (See the articles by Wolever, Simmons, and Sforzo in this issue.)

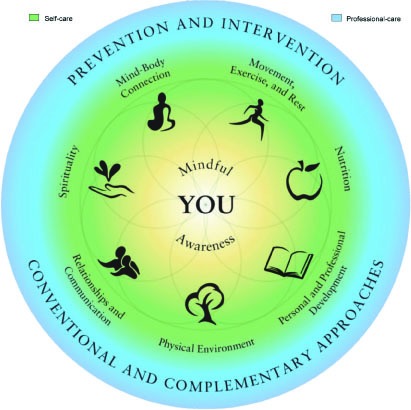

IHC, as conceived and operationalized at Duke Integrative Medicine, is taught through the IHCPT curriculum there. Distinct from some other forms of health coaching, the word integrative reflects its roots in integrative medicine (IM) and its alignment with IM values of whole-person care, patient-centeredness, mindfulness, and healthy lifestyle (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Duke Integrative Medicine Wheel of Health.

Copyright © 2010 by Duke University on behalf of Duke Integrative Medicine. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved. MCOC-8720

Origins of the Duke Integrative Health Coaching Training

The IHCPT trains professionals with various backgrounds in healthcare in an interpersonal coaching technique aimed at empowering patients to make and sustain healthy lifestyle choices. The program sprung from two fundamental observations. The first was that people often struggle to make and sustain health-related behavior changes, even when well informed and seemingly motivated. The second was that a clinical professional specifically educated and trained to partner with patients to affect behavior change is absent from the present system. To fill this gap, Duke began developing and testing IHC in 2002, and the foundation and certification programs were launched in 2008 and 2010, respectively.

IHC is a new field but draws on 8 decades of theory and research in developmental and humanistic psychology. Specifically, developmental psychology theory holds that individuals use goals and planning to create their futures through continued learning and through moving toward self-individuation by living “on purpose.”27–36 Humanistic psychology emphasizes this sense of purpose and interpersonal connectedness in understanding motivation.37 More recent work further articulates the underpinnings of IHC through self-determination theory and the subsequent self-concordance theory.38–41 These theories explain the motivational basis of goal selection and its relationship to an individual's core values. Taken together in a healthcare context, these theorists consider patients as lifelong learners whose individual values and sense of purpose facilitate their potential for change.

The field of coaching adds to this underlying framework specific techniques derived from 5 decades of outcomes data in psychotherapy and brief solution-focused therapies.42–45 These techniques focus not on pathology but on behavior change. IHC is thus built on the assertion that people have innate wisdom, strength, and creativity that, when skillfully recruited, will guide them to health more efficiently than will external advice.26

What Integrative Health Coaching Is Not

Duke-trained integrative health (IH) coaches are differentiated from a number of related professions by a distinct set of skills and practices. IH coaches do provide health education when requested by patients, but IH coaches have additional skill sets and hold a different stance than that of typical health educators. While coaches may have a wide knowledge base of medical issues and diverse healthcare resources, their area of expertise is not medicine—it is specifically in building motivation for behavior change. The main role of an IH coach is not to educate but to assist the patient in bringing about change that the patient holds as important. Often in collaboration with clinicians and educators who design and clarify treatment plans, IH coaches work with each patient's whole situation—from his or her spiritual beliefs to exercise aversions—to foster an environment where their plans can take hold.

IHC also is distinct from psychotherapy in that coaches guide patients toward goals using a forward focus, whereas therapists maintain a broader focus and also help patients heal psychological wounds from the past.23 Although IHC shares methodology with other forms of coaching such as life and executive coaching, it is distinct in its inclusivity of highly vulnerable patients with medical issues and in its focus on health and well-being.23

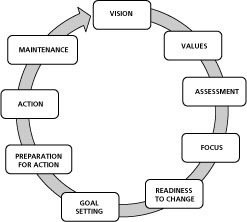

The Duke Integrative Health Coaching Process

The Duke IHC process model provides a structure for coaches to guide patients through various stages of preparation for change, action, and integration of learning, as well as a map for the creation of personalized health plans (Figure 2). The coaching process begins with exploration of an individual's overall vision for health and well-being and proceeds to explore core values, assess gaps between current and desired lifestyles, and move toward specific goals in small steps. IH coaches help patients fully explore their readiness and confidence with regard to change and support their orientation toward the new health behavior. In addition, coaches are trained to enhance the success of the goal-setting process by developing a specific plan with the patient for change that is customized to the patient's real life and resources. Coaches are trained to maintain forward momentum but work flexibly within the process, frequently referring back to a patient's deeply held values and overall sense of purpose.

Figure 2 Duke Integrative Health Coaching Process Model. Copyright © 2012. Reprinted with permission from Duke Integrative Medicine. All rights reserved.

IH coaches learn skills, including those taught in motivational interviewing, that can elicit insight into ambivalence and enhance motivation. They also learn to work with self-limiting perspectives patients may have about making change and help them develop a point of view that is more empowering for their own success.

A participant in a 10-month group education and individual coaching intervention who lost 60 lbs, lowered her blood pressure, and regained control of her diabetes summed up the process this way:

It's like the saying, “If you feed a man a fish he can eat for a day; teach him how to fish and he can eat for life.” My doctor pointed in the direction of the stream, my coach took me by the hand and walked me to it, taught me how to cast. Together we caught enough fish and made a gourmet meal and went back again and again to fish. (J. Wakefield, oral communication, March 2012.)

The Scope of Integrative Health Coaching Is the Whole Person

Like other training models of IHC, the Duke IHCPT emphasizes whole-person care, patient-centeredness, mindfulness, and lifestyle, expressed figuratively in the Wheel of Health. The four rings of the Wheel reflect the patient-centric nature of whole-person health. The center-most zone refers to the patient, around whom the healthcare process must always revolve. Through IHC, individuals are encouraged to recognize this and assume their rightful place at the center of their well-being.

Also similar to other IHC models, mindful awareness comprises the second ring and is a cornerstone of IHC in the Duke model. Mindful awareness refers to the ability to be fully present, without judgment, to what is happening at any given time, particularly internally in terms of thoughts, feelings, sensations, and behavioral urges.46 Enhanced mindfulness facilitates the ability to choose a response rather than react habitually.23,46 The third ring depicts seven categories of self-care: mind-body connection; movement, exercise, and rest; nutrition; relationships and communication; personal and professional development; physical environment; and spirituality. The outer ring encompasses professional care and includes prevention, intervention and conventional and complementary care.

The Duke Integrative Health Coach Professional Training Course of Study

Acceptance into the Duke foundation program requires a bachelor's or advanced degree or 3 to 5 years' experience in a medical or allied health field such as medicine, nursing, physical therapy, health education, exercise physiology, psychotherapy, or nutrition. The foundational program consists of 113 hours of onsite and distance education and training in coaching techniques. As part of this training, students participate in 36 to 42 hours of remote educational activities and practice sessions over approximately 4 months. Participants who complete the foundation program are eligible to enroll in the certification program.

Certification training provides an opportunity for further refinement of skills through ongoing study, practice, and supervision. At present, the Duke IHCPT is the only health coaching program that strongly encourages extensive experiential mindfulness training in the form of an 8-week mindfulness-based stress reduction course.46 Other certification requirements include a 6-month coaching skills development program, 100 documented hours of coaching, one-on-one supervision of recorded sessions, and written and oral examinations. The entire training program takes between 12 and 18 months to complete.

SYNCHRONICITY BETWEEN INTEGRATIVE HEALTH COACHING AND HEALTHCARE REFORM

Prevention aims Within Us Healthcare Reform

The emergence of IHC coincides with recognition by the federal government of the need to actively address the problem of widespread chronic diseases within the United States. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, passed in 2010 and upheld by the US Supreme Court in June 2012, contains measures to fill critical gaps in health-care; improve availability, affordability, and quality of services; and assert a strong focus on prevention. Specifically, Title IV, Prevention of Chronic Disease and Improving Public Health, has called for cooperation between public and private sectors to create health promotion education and outreach programs, implement personalized prevention planning and annual wellness visits within Medicare, enact employer-based wellness programs, and other tactics.47

Title IV also called for the creation of the National Prevention, Health Promotion, and Public Health Council (NPC) chaired by the US Surgeon General and advised by a nonfederal advisory group of public health experts and integrative health practitioners with expertise in preventive medicine, health coaching, community services, and other fields.47 The role of the advisory board is to counsel the NPC regarding ways to improve prevention and management of lifestyle-based chronic diseases.47 The NPC describes its vision as “moving the nation from a focus on sickness and disease to one based on prevention and wellness.”12

The NPC published the first National Prevention and Health Promotion Strategy (NPS) in June 2011. It unveiled a new national agenda aimed at improving longevity, health, and productivity among all Americans and issued a call to action to government institutions, academic centers, private businesses, and other groups to implement disease prevention strategies.12 The overall goal of the NPS is “increasing the number of Americans who are healthy at every stage of life” (a rephrasing of its original, more measurable working goal of “increasing the number of Americans who are healthy at age 85”12,48). The four pillars, or strategic directions, of the NPS are healthy communities, preventive clinical and community efforts, empowered individuals, and elimination of health disparities. Further, seven designated imperatives, or priorities, are tobacco-free living, prevention of drug and alcohol abuse, healthy eating, active living, mental and emotional health, sexual and reproductive health, and public safety from injury and violence (Figure 3).

Figure 3 National Prevention Strategy wheel.12

Specific tactics for the implementation of these 11 categories are delineated and upon examination, reveal root themes of the NPS. First, as stated in its overarching goal, there is the theme of timing and foresight and the implication that effective prevention requires participation in the healthcare system at times of health, in addition to early and later stages of disease.12 Second, there is an emphasis on the importance of lifestyle, as exhibited by the seven priorities around diet, exercise, and other health-related habits. And third, themes of patient centricity and empowerment appear throughout the NPS in addition to being one of the four overall pillars.12 These themes are in full alignment with the underlying philosophy and mission of Duke's model of IHC.

Integrative Health Coaching Training Mirrors Our National Prevention Vision

Core principles of the national prevention agenda—including individual empowerment, collaborative care, and prevention education of healthcare providers—run parallel to IHC aims. This alignment underscores the timeliness of the emergence of the IHC profession to address unmet needs in the healthcare system.

Empowerment of Individuals to make Healthy Choices, the Importance of self-care, and Personalization of Health Planning.

A main pillar of the NPS involves empowerment of individuals. Specific aims include helping people recognize and make healthful food and beverage choices, avoid drug and alcohol abuse, and quit smoking.12 IHC was developed precisely for such aims. The primary role of IH coaches is to facilitate patient engagement and activation toward their health goals using the best available methodology.

Health as a Goal at Every stage of Life.

Increasing the proportion of healthy Americans at every age lies at the heart of the NPS agenda.12 Implementation of personalized health planning (PHP) offers a means for care coordination, patient centricity, patient engagement, disease prevention, and cost containment.49 PHP would ideally begin at or before birth and would involve a team approach inclusive of health coaching.

Importance of Relationships and Community in Fostering Health.

Another pillar of the NPS involves the creation of healthy and safe community environments.12 Further, the value of supportive relationships is highlighted as a factor in personal empowerment and emotional well-being.12 Relationships and communication comprise one of seven essential self-care domains in the IHC Wheel of Health (Figure 1). As such, IH coaches promote healthy, supportive relationships as a component of optimal health.

Integration Between allopathic and Complementary approaches.

The NPS is committed to enhancing coordination and integration of clinical, behavioral, and complementary approaches to health. It recognizes that evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) provides value by “individualizing treatments, treating the whole person, promoting self-care and self-healing, and recognizing the spiritual nature of each individual, according to individual preferences.”12 IHC professionals develop a working knowledge of diverse approaches to health including CAM and are supportive of the best of CAM toward these ends. As such, they serve as a resource for interested patients.

Educating and Reorienting Healthcare Professionals toward Prevention.

The NPS calls on health-care providers, communicators, and educators to participate in the transformation of the healthcare mind-set toward prevention.12 To date, approximately 450 professionals, including physicians, nurses, nutritionists, physical therapists, psychologists, social workers, and others from across the country have received IHC training at Duke, and more than 50 have become certified through this program.

Research in Integrative Health Coaching

Duke IM has conducted four prospective trials using IHC that have demonstrated improvements in measures of diabetes and diabetes risk, weight management, and risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke.50–53 Additionally, a prospective trial described in this issue of Global Advances in Health and Medicine reports on the findings from an insurance industry-based coaching program that used UMN-trained coaches.54 In the first Duke randomized, controlled trial (RCT) that included IHC, an integrated intervention incorporating personalized health planning, group education, and IHC outperformed a usual-care control, showing significant reductions in 10-year prospective Framingham Risk for cardiovascular disease in a secondary prevention sample.50 The coaching intervention included 22 individual telephonic biweekly sessions lasting 20 to 30 minutes that served to clarify priorities, set goals, maintain motivation, assist with identification of resources, and reinforce lifestyle and mind-body skills developed in the 27 group sessions.50 In a second RCT, patients with type II diabetes were randomized to receive IHC alone or a wait-list usual care control. Those in IHC demonstrated significantly increased medication adherence and physical exercise, as well as multiple psychosocial improvements. In addition, IHC participants with elevated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) at baseline significantly reduced HbA1c while those in the control group did not.51 The third study that included IHC was a prospective observational trial of an integrated intervention that began with a 3-day immersion program and personalized health planning followed by IHC. This trial demonstrated that the intervention lowered 5-year prospective risk for diabetes and for stroke in a highly heterogeneous convenience sample.52 Finally, an RCT conducted collaboratively with Duke and University of Pennsylvania revealed that participants randomized into a mindfulness-based weight loss maintenance program that incorporated IHC maintained significant weight loss 16 months post-baseline as well as participants of a standardized, state-of-the-art weight-loss maintenance program did.53 Research has also uncovered psychosocial, quality-of-life, and cost benefits associated with IHC.51,52,55 Finally, a prospective study followed high-risk health plan enrollees who self-selected to participate in an integrative health coaching intervention led by coaches trained through a customized and modified version of the UMN IHC program. Study participants completed pre- and post-measures on patient activation and health inventories, and improvements were documented in patient activation levels, readiness to change, and self-reported health outcomes.54 Additional IHC research in cardiovascular disease prevention and diabetes risk, obesity prevention, and management of intractable tinnitus is ongoing at Duke IM.56–60

Integrative Health Coaching Models in the US Department of Veterans Affairs

An example of educational and clinical innovation involving IHC is taking place at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation, created in 2011 and directed by former executive director of Duke Integrative Medicine, Tracy Gaudet, MD, has launched several pilot programs aimed at providing personalized, proactive, patient-driven care for US veterans using components of the methodology of Duke IHC.61,62 One program that is underway uses a traditional clinical framework and involves identification of individuals who might benefit from coaching. These individual are then referred for a series of one-on-one sessions with a designated on-staff coach. A second approach involves training VA clinicians and staff in core competencies of IHC in order to inform the way they provide care in the context of their usual roles.

At the suggestion of VA leaders committed to innovation and long-term objectives of patient-centered care, individual VA-employed practitioners from a range of arenas including medicine, nursing, and fitness have completed the foundational IHC training at Duke.61 Recently, 35 staff members at the VA Medical Center in Fayetteville, North Carolina, with backgrounds in mental health, social work, and supportive housing, completed foundational training as a group. Attendees reported that learning and practicing IHC techniques did more than improve their patient care and communication skills. The participants also derived a greater sense of personal empowerment and purpose, which in turn boosted camaraderie within their teams and confidence in their ability to handle on-the-job challenges (J Vertrees, oral communication, March 2012).

Future Plans for National Accreditation and Certification for Health Coaches

A joint volunteer effort is underway to develop a national standard for training and certification of health and wellness coaches in the United States. During an inaugural meeting in September 2010, the National Consortium for the Credentialing of Health and Wellness Coaches (NCCHWC) endeavored to bring sharper definition to roles and requisite core competencies of coaches within healthcare.62 The NCCHWC is comprised of health, wellness, and coaching representatives from Duke Integrative Medicine, University of Minnesota, Harvard Medical School, Vanderbilt Medical School, and other academic institutions as well as representatives from government, healthcare advocacy, and industry (including disease management, insurance, and pharmaceutical companies). Better definitions of coaching interventions and standardized health coach credentialing will create new possibilities to shape policy, succeed in our clinical and educational missions, and perform collaborative clinical research.26

Practice Implications

IHC is a rapidly emerging brand of health coaching with solid preliminary evidence that suggests its utility in combating lifestyle-related conditions. Given the current challenges within healthcare and the fact that IHC aligns well with published national prevention aims, broader use of IHC could augment momentum toward empowering individuals to improve their own health. The potential to reduce rates of chronic conditions— and lessen related morbidity, mortality, psychosocial, and cost burdens—would benefit stakeholders across all areas of public and private healthcare sectors.

Acknowledgments

The studies described were funded by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Duke University Health System, GlaxoSmithKline and the National Institutes of Health (National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine grants AT-001-4158 and AT-001-4159).

Disclosures The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest, and Dr Simmons disclosed a grant from the Center for Personalized Medicine and the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/NIH Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to Duke Integrative Medicine. Ms Smith disclosed receipt of payment for lectures including service on speakers bureaus from the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Drs Perlman, Wolever, and Wroth reported no relevant financial interests.

Contributor Information

Linda L. Smith, Duke Integrative Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, United States.

Noelle H. Lake, Noelle Lake Coaching (private practice), Brooklyn, New York, United States.

Leigh Ann Simmons, Duke Integrative Medicine, Duke University Health System and School of Nursing and Center for Research on Prospective Health Care, United States.

Adam Perlman, Duke Integrative Medicine and Department of Medicine, Duke School of Medicine, United States.

Shelley Wroth, Duke Integrative Medicine and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Duke School of Medicine, United States.

Ruth Q. Wolever, Duke Integrative Medicine and Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, Duke School of Medicine, United States.

REFERENCES

- 1.Duke University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program. http://paprogram.mc.duke.edu/PA-Program/ Accessed March 17, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Physician Assistant Census Report: Results from the 2010 AAPA Census. American Academy of Physician Assistants; 2010. http://www.aapa.org/uploadedFiles/content/Common/Files/2010_Census_Report_Final.pdf Accessed April 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quick Facts. American Academy of Physicians Assistants; http://www.aapa.org/the_pa_profession/quick_facts.aspx Accessed May 23, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Power of Prevention Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/pdf/2009-power-of-prevention.pdf Accessed April 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yach D, Hawkes C, Gould C, Hofman KJ. The global burden of chronic diseases overcoming impediments to prevention and control. J Amer Med Assoc. 2004;291(21):2616–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snyderman R. The AAP and the transformation of medicine. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(8):1169–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snyderman R, Dinan MA. Improving health by taking it personally. J Amer Med Assoc. 2010;303(4):363–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis K, Guterman S, Collins SR, Stremikis K, Rustgi S, Nuzum R. Starting on the path to a high performance health system: analysis of health system reform provisions of reform bills in the House of Representatives and Senate. 2009. The Commonwealth Fund; http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Reports/2009/Nov/Starting-on-the-Path-to-a-High-Performance-Health-System.aspx?page=allAccessed April 13, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson G, Herbert R, Zeffiro T, Johnson N. Chronic conditions: making the case for ongoing care. Partnership for Solutions (Johns Hopkins and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation) 2004. http://www.policyarchive.org/handle/10207/21756 Accessed April 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paez KA, Zhao L, Hwang W. Rising out-of-pocket spending for chronic conditions: a ten-year trend. Health Affairs. 2009;28(1):15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Health Expenditure Projections 2010-2020: Forecast Summary. https://www.cms.gov/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/proj2010.pdf Accessed March 17, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Prevention Council, National Prevention Strategy Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, 2011. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/initiatives/prevention/strategy/index.html Accessed April 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization Primary care: putting people first. In: The World Health Report 2008. Primary health care—now more than ever. http://www.who.int/whr/2008/whr08_en.pdf Accessed April 12, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whellan DJ, Gaulden L, Gattis WA, et al. The benefit of implementing a heart failure disease management program. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(18):2223–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams RS, Willard HF, Snyderman R. Personalized health planning. Science. 2003;300(5619):549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toda N, Nakanishi-Toda M. How mental stress affects endothelial function. Pflugers Arch. 2011;462:779–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrès R, Yan J, Egan B, et al. Acute exercise remodels promoter methylation in human skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2012;15(3):405–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathers JC, Strathdee G, Relton CL. Induction of epigenetic alterations by dietary and other environmental factors. Adv Genet. 2010;71:3–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alegria-Torres JA, Baccarelli A, Bollati V. Epigenetics and lifestyle. Epigenomics. 2011;3(3):267–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gruman J, Rovner MH, French ME, et al. From patient education to patient engagement: Implications for the field of patient education. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(3):350–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hibbard JH. Moving toward a more patient-centered health care delivery system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Suppl variation:VAR133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mezzich JE. Building person-centered medicine through dialogue and partnerships: perspective from the International Network for Person-centered Medicine. International J Person Centered Med. 2011;1:10–13 http://www.ijpcm.org/index.php/IJPCM/article/view/13/8 Accessed April 16, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolever RQ, Caldwell KL, Wakefield JP, et al. IH coaching: an organizational case study. Explore. 2011;7(1):30–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Health and Wellness Coach Training Options. http://www.instituteofcoaching.org/images/ARticles/Heath%20and%20Wellness%20CoachTrainingPrograms-July-2011.pdf Accessed April 5, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreitzer MJ, Sierpina VS, Lawson K. Health coaching: innovative education and clinical programs emerging. Explore. 2008;4(2):154–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolever RQ, Eisenberg DM. What is health coaching anyway? Standards needed to enable rigorous research. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(22):2017–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudson FM. The handbook of coaching. Hoboken, New Jersey: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams P, Davis DC. Therapist as life coach: Transforming your practice. New York: WW Norton & Company; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adler A. In HL Ansbacher and RR Ansbacher. The individual psychology of Alfred Adler: A systematic presentation in selections from his writings. New York: Harper Perennial; 1956 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adler A. Understanding human nature. Brett C, translator. Center City, Minnesota: Hazelden; 1927 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jung CG. The Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Adler G, Fordham M, Read H, McGuire W, editors. New Jersey: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung C. The Portable Jung. Hull R, translator. London and New York: Penguin Viking; 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jung CG. Dream analysis and its practical applications. Modern man in search of a soul. New York: Harcourt Brace & Co; 1933 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maslow AH. Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Brothers; 1954 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maslow AH. Toward a psychology of being. New York: Van Nostrand; 1968 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frankl VE. Man's search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. New York: Washington Square Press; 1969 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers CR. Client-centered therapy. Boston, Massachusetts: 1951 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory: When mind mediates behavior. J Mind Behav. 1980;1:33–43 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheldon KM, Elliot AJ. Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76(3):482–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheldon KM, Deci EL, Ryan RM, editors. The self-concordance model of healthy goal striving: When personal goals correctly represent the person. Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, New York: University of Rochester Press; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheldon KM, Elliot AJ. Not All Personal Goals Are Personal: Comparing Autonomous and Controlled Reasons for Goals as Predictors of Effort and Attainment. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1998;24(5):546–57 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hubble MA, Duncan BL, Miller SD, editors. The heart and soul of change: What works in therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Hanlon B, Beadle S. Guide to possibility land: Fifty-one respectful methods for doing brief therapy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Hanlon B. Do one thing different: And other uncommonly sensible solutions to life's persistent problems. New York: William Morrow & Company; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Shazer S. Keys to solution in brief therapy. New York: Norton; 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Prac. 2003;10:144–56 [Google Scholar]

- 47.The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. Pub L No. 111-148, 124 Stat 119. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf Accessed March 17, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meeting of the Advisory Group on Prevention, Health Promotion, and Integrative and Public Health [summary]. April12-13, 2011. Washington, DC: Available at: http://www.healthcare.gov/prevention/nphpphc/advisorygrp/a-g-meeting-summary-april-12-13.pdf Accessed March 18, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dinan MA, Simmons LA, Snyderman R. Personalized health planning and the patient protection and affordable care act: An opportunity for academic medicine to lead health care reform. Acad Med. 2010;85:1665–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edelman D, Oddone EZ, Liebowitz RS, et al. A multidimensional integrative medicine intervention to improve cardiovascular risk. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:728–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolever RQ, Dreusicke M, Fikkan J, et al. Integrative health coaching for patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:629–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolever RQ, Webber DM, Meunier JP, Greeson JM, Lausier ER, Gaudet TW. Modifiable disease risk, readiness to change, and psychosocial functioning improve with integrative medicine immersion model. Altern Ther Health Med. 2011;17:38–47 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolever RQ, Caldwell K, Fikkan J, et al. Enhancing mindfulness for the prevention of weight regain: the impact of the EMPOWER program. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine; March, 2012; New Orleans, La [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lawson KL, Jonk Y, O'Connor H, Sundgaard Riise K, Eisenberg DM, Kreitzer MJ. The impact of telephonic health coaching on health outcomes in a high-risk population. Global Adv Health Med. 2013;2(3):26–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hignite K. Segmenting Risk [Strategy]. NACUBO HR Horizons. 2008. Available at: http://hrhorizons.nacubo.org/x169.xml Accessed on March 21, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Study funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute entitled: Mindfulness-based Personalized Health Planning for Reducing Risk Factors of Heart Disease and Diabetes (AWARENESS) to PI Edward Suarez. Clinical Trials Identifier NCT01430221. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Study funded by the Duke Center for Personalized Medicine entitled GENErating Change to co-PIs Ruth Wolever and Allison Vorderstrasse. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vorderstrasse AA, Ginsburg GS, Kraus WE, Maldonado CJ, Wolever RQ. Health coaching and genomics: potential avenues to elicit behavior change in those at risk for chronic disease: protocol for personalized medicine effectiveness study in Air Force primary care. Global Adv Health Med. 2013;2(3):12–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang NY, Wroth S, Parham P, Strait M, Simmons LA. Personalized health planning with Integrative Health Coaching to reduce obesity risk among women gaining excess weight during pregnancy: pilot study and case report. Global Adv Health Med. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Study Funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders entitled New Therapy for Patients with Severe Tinnitus to co-PIs Debara Tucci and Ruth Wolever. Clinical Trials Identifier NCT01480193. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horrigan B. Tracy Gaudet to lead new VA office [Matters of Note]. Explore. 2011;7:141 [Google Scholar]

- 62.National Consortium for Credentialing Health and Wellness Coaches. http://ncchwc.org/our-vision-mission-plan/a-call-to-action/ Accessed March 22, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]