Abstract

Icosahedral viral capsids are obligated to perform a thermodynamic balancing act. Capsids must be stable enough to protect the genome until a suitable host cell is encountered yet be poised to bind receptor, initiate cell entry, navigate the cellular milieu, and release their genome in the appropriate replication compartment. In this study, serotypes of adeno-associated virus (AAV), AAV1, AAV2, AAV5, and AAV8, were compared with respect to the physical properties of their capsids that influence thermodynamic stability. Thermal stability measurements using differential scanning fluorimetry, differential scanning calorimetry, and electron microscopy showed that capsid melting temperatures differed by more than 20°C between the least and most stable serotypes, AAV2 and AAV5, respectively. Limited proteolysis and peptide mass mapping of intact particles were used to investigate capsid protein dynamics. Active hot spots mapped to the region surrounding the 3-fold axis of symmetry for all serotypes. Cleavages also mapped to the unique region of VP1 which contains a phospholipase domain, indicating transient exposure on the surface of the capsid. Data on the biophysical properties of the different AAV serotypes are important for understanding cellular trafficking and is critical to their production, storage, and use for gene therapy. The distinct differences reported here provide direction for future studies on entry and vector production.

INTRODUCTION

The capsids of icosahedral viruses display multifunctional attributes in the viral life cycle. Depending on the virus type, capsid viral protein (VP) functions include receptor binding, cell entry, intracellular trafficking, genome release, capsid assembly, and genome packaging. Additional selective pressure on VPs can also arise from the host immune response. Several small nonenveloped icosahedral viruses, including the single-stranded-DNA (ssDNA)-packaging viruses of the family Parvoviridae, have a capsid that is composed of essentially a single multifunctional VP (1). Adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes belong to the genus Dependovirus of the Parvoviridae. They efficiently replicate in the presence of a helper virus, such as Adenovirus or Herpesvirus (2, 3), and have distinct capsid-governed tissue specificities and strict host ranges (4, 5). Thirteen distinct human and nonhuman primate AAV serotypes (AAV1 to -12 and AAV[VR-942]) have been described to date, and more than 100 AAV genomes across species have been identified using PCR (5–7, 9, 100). These viruses have been classified into eight clades and clonal isolates (AAV1/AAV6, AAV2, AAV2/AAV3, AAV4, AAV5, AAV7, AAV8, and AAV9) based on VP sequence and antigenicity (5).

The AAVs have shown significant promise as vectors for gene delivery for the correction of monogenetic defects. They possess the following positive attributes: they do not cause disease, have a stable virus particle that can be purified by biomedically accepted methods used for recombinant protein products, can be produced void of viral coding genes, can transduce dividing and nondividing cells, and can induce long-term transgene expression in certain cell types (10, 11). The majority of gene therapy applications to date have used AAV2, including the treatment of blindness in patients with Leber's congenital amaurosis (11, 12). Interest in the use of other serotypes (AAV1, AAV5, AAV6, and AAV8, for example) is growing because of their different tissue specificities, cell transduction efficiencies, and antigenicities (5, 6, 11, 13, 14, 101). AAV2 has also received the most attention with respect to dissecting the mechanisms of cellular entry and trafficking. For this serotype, attachment to the host cell surface is mediated by heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) (15–18, 97), and several secondary receptors or coreceptors have been reported to mediate entry via dynamin-dependent clathrin-mediated endocytosis (19–22, 25). AAV2 may also enter cells via a dynamin- and clathrin-independent route (26). HSPG has been found to bind AAV3 strains B (27, 98) and H, while receptor binding of strain H extends to fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (28). Linkage-specific sialic acid binding is utilized by AAV1, AAV4, AAV5, and AAV6 (29–31). For AAV5, platelet-derived growth factor receptor has been identified as having a role in the binding of this serotype to a glycoprotein (32). A terminal glycan receptor has yet to be identified for AAV8, while it has been reported to utilize the 37/67-kilodalton laminin receptor for cellular transduction (19). AAV9 shares ∼85% sequence similarity with AAV8 and also utilizes the laminin receptor as well as N-linked glycans with terminal galactosyl residues (19, 33, 99). Lastly, AAV7, which shares ∼88% sequence similarity with AAV2 and AAV8, has yet to be associated with a specific receptor.

AAV capsids have T=1 icosahedral symmetry and are approximately 250 Å in diameter (Fig. 1). Their relatively small capsid size limits their genome to ∼4.7 kb, with two major open reading frames (ORFs), rep and cap. The rep ORF encodes four proteins required for genome replication and packaging. The cap ORF encodes three structural VPs, VP1, VP2, and VP3, made from alternately spliced mRNAs (10). The proteins overlap, with common C termini. VP3 is ∼61 kDa and constitutes ∼85% of the capsid's protein content. The less abundant capsid proteins, VP1 (∼87 kDa) and VP2 (∼73 kDa), containing unique N-terminal extensions (VP1u) containing a phospholipase A2 (PLA2) domain and nuclear localization signals (VP1/2 common region), respectively (34, 102). A total of 60 copies of the three VPs, in a ratio of 1:1:8 to 10 (for VP1:VP2:VP3, respectively) based on gel densitometry (35, 36), assemble the T=1 icosahedral particle (37). A third alternative ORF, in the VP2/VP3 mRNA, which encodes an assembly-activating protein reported to aid capsid assembly, was recently discovered (38). It is believed that during cellular entry by AAV capsids, exposure to acidic conditions in endosomes leads to a conformational change and exposure of the VP1u and VP1/2 common regions required for endosomal escape and nuclear entry (34). Interaction with cellular proteases and pH-activated autohydrolysis have also been implicated in the entry process (39). In vitro studies typically use a heat pulse as a surrogate for cellular triggers of VP1u and VP1/2 externalization, although characterization of capsids after heating has primarily been limited to antibody detection and electron microscopy (EM) studies (34, 40–42, 75).

Fig 1.

Structure and conservation of adeno-associated viruses. (A) Surface topology of AAV2, shown as a depth-cued model, with blue regions being further from the particle center and white closer. (B) Icosahedral grid overlaid on a structural model of AAV2. Four subunits are shown in different colors to emphasize interdigitation. Symbols indicate 2-fold (oval), 3-fold (triangle), and 5-fold (pentagon) axes. The capsid is in the same orientation as in panel A. (C) Superimposition of Cα positions of the VP3 monomers of AAV1, AAV2, AAV5, and AAV8. Amino acid sequence conservation is shown in the color scheme; purple is highest, and gold is lowest. The core of the subunit is highly conserved, with the sequence variability being primarily in loops I to IX. The N and C termini are also indicated. The triangle, pentagon, and oval indicate the positions of the 3-, 5- and 2-fold axes. (D) Sequence identity between serotypes. Data were obtained from multiple sequence alignment of AAV1, AAV2, AAV5, and AAV8 using ClustalW.

The capsid structures of the nine AAV serotypes that represent the clade and clonal isolates have been determined by cryo-electron microscopy and/or X-ray crystallography (27, 43–47, 103, 104). In all cases, only the VP3 common region is ordered. The VP subunit is formed by a conserved eight-stranded β-barrel (βB-I) and a single α-helix (αA), which forms the contiguous capsid core with loop regions inserted between the strands of the β-barrel (Fig. 1C). Structural studies and mutational analyses of AAVs have identified differences on the surface of capsids that localize to common variable regions (VRs) involved in receptor binding, host tropism, and antigenic determinants (reviewed in references 1, 3, and 4). Sequence differences can be minor, as in the case of AAV1 and AAV6, which differ by only 6 out of 736 amino acids (0.8%), yet lead to functional changes in receptor binding affinities and transduction rates (48). Larger differences also exist, such as those between AAV5 and AAV1, which share only 58% amino acid sequence identity (Fig. 1D). A commonality of all AAV structures determined to date is regions of protein/DNA interaction with a well-ordered nucleotide. These interactions are present in capsids packaging heterologous cellular DNA or specific viral sequences (27, 43, 44, 47).

This study focused on the biophysical characterization of AAV capsids using virus-like particles (VLPs) and GFP Gene-containing virions of four serotypes, AAV1, AAV2, AAV5, and AAV8. These serotypes were selected because they are from four different clades and represent a range of sequence and structural diversity across the eight AAV antigenic clades and clonal isolate groups. Complementary thermal stability assays using differential scanning fluorescent dye binding (DSF), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and negative stain electron microscopy revealed that the temperature at which capsid degradation occurred differed among the serotypes. AAV5 was the most stable with a melting temperature (Tm) that was ∼5, ∼17, and ∼20°C higher than AAV1, AAV8, and AAV2, respectively. Protein dynamics, assessed by limited proteolysis, showed that each serotype has a specific proteolytic profile, yet the most dynamic region of the capsid in all cases clustered around the icosahedral 3-fold axes of symmetry reported to play a role in receptor attachment for AAV2 and AAV8 (15–17, 19, 47, 90, 97, 105). Proteolysis was also observed in the VP1u region that contains the PLA2 domain. The detection of protein dynamics in VP1u and the receptor binding region is consistent with models that have been developed for other icosahedral viruses in which functional VP domains are dynamic and that internal domains can be transiently exposed on the capsid surface.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus-like particle production and purification.

Recombinant baculovirus encoding VP1, VP2, and VP3 of AAV1, AAV2, AAV5, and AAV8 were generated using the Bac-to-Bac expression system (catalog no. 10359-016; Invitrogen). The virus-like particles (VLPs) of each virus were expressed in Sf9 cells and purified according to previously established protocols (51–54). AAV2 was purified using a step iodixanol gradient followed by anion-exchange chromatography (55, 56), and AAV1, AAV5, and AAV8 were purified on a sucrose cushion followed by a step sucrose gradient (51–54). The pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.2% Triton X-100), freeze-thawed three times in a dry ice-ethanol slurry and 37°C water bath with the addition of 1 μl of Benzonase (50-U/ml final concentration; catalog no. E1014; Sigma), and incubated at 37°C for 30 min after the second freeze-thaw cycle. The crude cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 12,100 × g at 4°C for 15 min. For AAV2, the clarified supernatant was loaded onto a discontinuous 15 to 60% iodixanol (Optiprep) step gradient (catalog no. 1114542; Nycomed) and centrifuged at 350,000 × g at 18°C for 1 h, and the gradient was fractionated. The 25% iodixanol gradient fraction, enriched with AAV2 VLPs, was further purified on a 5-ml HiTrap Q anion exchange column (catalog no. 17-5159-01; GE Healthcare). The sample was diluted with buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, 15 mM NaCl [pH 8.5]), loaded onto the column, washed with 50 ml of buffer A, and eluted with a gradient of 30 ml of buffer A and buffer B (20 mM Tris, 15 mM NaCl [pH 8.5]), and the peak fractions were collected. The cell lysates of AAV1, AAV5, and AAV8 were pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 149,000 × g at 4°C for 3 h through a 20% (wt/vol) sucrose cushion in TNET buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.06% Triton X-100). The pellets were resuspended in TNTM buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.06% Triton X-100) at 4°C overnight. The samples were loaded onto a 5-to-40% sucrose (wt/vol) gradient and ultracentrifuged at 151,000 × g at 4°C for 3 h. The visible blue band (under a white light) at the 20 to 25% sucrose layer was extracted and dialyzed into 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl. The purity and integrity of the VLPs were monitored using Coomassie stained SDS-PAGE and negative-stain electron microscopy (EM) on a JEOL JEM-100CX III microscope, respectively.

Recombinant AAV production and purification.

Recombinant AAV (rAAV) capsids packaging a green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene, rAAV1-GFP, rAAV2-GFP, rAAV5-GFP, and rAAV8-GFP, were produced via calcium phosphate-based cotransfection of plasmid DNA containing the respective AAV cap, AAV2 rep, and adenoviral helper (E2A, E4, and VA) genes and the GFP gene flanked by the AAV2 inverted terminal repeats (pTR-UF11) into HEK293 cells. Following transfection, the cells were incubated for 72 h, harvested, and lysed by three cycles of freeze-thawing, with the addition of magnesium and Benzonase (as described above) in the last cycle. The clarified cell lysate was loaded onto an iodixanol step gradient (15, 25, 40, and 60%) (Nycomed) and centrifuged at 350,000 × g at 18°C for 1 h. The 25% (empty capsid) and 40 to 60% (GFP gene-containing capsids) fractions were collected, diluted 1:1 with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 150 mM NaCl (the wash buffer), and loaded separately onto different HiTrap 5-ml Q columns. After a washing, the virus-containing fraction was eluted by increasing the NaCl concentration to 1 M. The eluted samples were buffer exchanged into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 20 mM Na2HPO4, 20 mM NaH2PO4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2).

Differential scanning fluorescence (DSF) stability assay.

AAV samples were diluted into PBS, pH 7.0, at 25°C. PBS was selected because the pH of the buffered solution has a low-temperature dependence. Experiments were also conducted with citrate-phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, and there were no significant differences in the observed melting temperatures (Tm). Tm was defined as the maximum value of the first derivative (dF/dT; change in fluorscence/change in temperature) from the raw signal. Assays were run with a final protein concentration of 0.1 to 0.24 mg/ml. To each sample, 2.5 μl of 1% Sypro-Orange dye (no. S6651; Invitrogen Inc.) was added to bring the final volume of each reaction to 25 μl. The assays were conducted in a quantitative PCR (qPCR) instrument (RG-3000; Corbett Research) with temperature ramping from 30 to 99°C, increasing 0.1 degree every 6 s. A control sample of lysozyme, at a concentration of 0.24 mg/ml, was included in each run as a positive control. The lysozyme Tm was calculated to be 67°C, with a maximum fluorescence at 74°C. To test for solute effects and intercapsid interaction, AAV2 and AAV5 were mixed at equal concentrations and incubated at 25°C for 2 h before analysis.

Differential scanning calorimetry.

AAV VLP samples were dialyzed into PBS at pH 7.3 as the final buffer, which also served as the reference. The AAV samples were run at 0.24 to 0.7 mg/ml. Triplicate assays were conducted in a VP-DSC instrument (MicroCal), with buffer and sample loaded in two different chambers, with temperature ramping from 10 to 100°C at a scan rate of 60°C/h. The thermal scans were plotted and analyzed using the Origin software suite (Origin Lab). The triplicate scans were averaged to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Averaged data were used to calculate standard deviations, which provided error values.

Electron microscopy.

AAV VLP samples were diluted to 0.1 mg/ml in PBS, pH 7.0. Ten microliters of each sample was heated to 37, 45, 55, 65, 75, 85, and 95°C for 3 min each using a thermal cycler. Five microliters of each sample, after cooling to room temperature, was applied to a carbon-coated copper grid, stained with 2% uranyl acetate, and viewed using a transmission electron microscope (a LEO 912 with a 2K-by-2K charge-coupled device [CCD] camera) at a ×31,000 magnification. Experiments were repeated three times using VLPs from different preparations.

Proteolysis and peptide mapping.

Proteinase K reactions to compare rates of proteolysis of the AAV VLPs were carried out in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, at a final concentration of 0.2 mg/ml and 0.07 mg/ml of VLP and enzyme, respectively. This equates to 43.5 nM VLP and 2.45 μM enzyme, or approximately a 1:1 molar ratio of VP to protease. Protein and enzyme were incubated at 37°C and aliquots were removed for analysis by SDS-PAGE, using gradient gels (4 to 20%) with a Tris buffer system (192 mM Tris base, 25 mM glycine, 3.4 mM SDS [pH 8.0]). Protease was inactivated by rapid heating in 2× standard gel loading buffer. Cleavage site mapping experiments were conducted using trypsin and thermolysin, which have high specificity. VLP and enzyme concentrations were 0.2 mg/ml and 0.01 mg/ml, respectively. Reactions were conducted at 25°C and were stopped by spotting onto a MALDI plate with alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid or sinapinic acid matrixes at 5, 10, and 20 min.

RESULTS

Stability of AAV capsids.

To obtain information on AAV capsid stability, two thermal denaturation assays, DSF and DSC, were utilized. DSF uses a hydrophobic dye which increases in fluorescence intensity upon binding to hydrophobic pockets in proteins that become accessible during heating (57). Thermal denaturation curves recorded by DSF for each of the serotypes as VLPs and rAAV-GFP samples showed clear differences in the transition temperature. For the VLPs, AAV2 was the least thermally stable, followed by AAV8, AAV1, and AAV5 (Fig. 2A; Table 1). For each serotype, the transition occurred over a narrow temperature range, which is indicative of cooperative protein unfolding. Tm was also determined using the complementary approach of DSC (Fig. 2B). The Tm values were within 2°C for the two approaches utilized (Table 1). The only significant difference was a second transition in the DSC profile of AAV8. Analysis of rAAV-GFP samples by DSF produced results very similar to those from VLPs (Table 1). This observation indicates that in AAVs, protein-protein and nongenomic DNA-protein interactions may have similar contributions of overall capsid stability behavior to genome-protein specific interactions as has been observed for small icosahedral RNA viruses (61, 62).

Fig 2.

Temperature dependence of particle disassembly. (A) Measurements of fluorescence intensity during heating show that AAV serotypes denature at different temperatures. Increases in intensity are associated with binding of Sypro orange with hydrophobic pockets that become accessible as the protein unfolds. (B) Differential scanning calorimetry profiles. Data are the normalized averages from three temperature scan experiments. Data were collected at pH 7 for AAV1 (dotted line), -2 (solid line), -5 (dashed line), and -8 (dotted and dashed line).

Table 1.

Melting temperatures of AAV capsids

| Serotype |

Tm(°C) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| VLPs (DSF) | Genome-filled particles (DSF) | VLPs (DSC) | |

| AAV1 | 84.5 ± 0.8 | 84 ± 0.3 | 84.4 ± 0.2 |

| AAV2 | 69.6 ± 0.5 | 71.6 ± 0.2 | 67.8 ± 0.2 |

| AAV5 | 89.7 ± 0.7 | 90.5 ± 0.3 | 89.6 ± 0.1 |

| AAV8 | 72.5 ± 0.5 | 73 ± 0.3 | 74.7 ± 0.4, 79.1 ± 0.3a |

AAV8 showed two transitions. The first was the more pronounced.

It has been observed that AAV5 and AAV8 VLPs produced using the baculovirus/Sf9 expression system incorporate reduced levels of VP1 compared to capsids (with and without packaged DNA) produced in mammalian systems (52). To determine if VP ratio and specifically VP1 contribute to thermal stability, VLPs lacking VP1 were analyzed by DSF. No change in Tm was observed (data not shown). This suggests that the VP1u domain does not contribute significantly to the stability of the tested AAVs. An additional experiment was designed to check for copurifying solute molecules that could be responsible for lowering or raising the thermal stability of a given sample. To test this, the serotypes with the greatest difference in Tm, AAV2 and AAV5, were mixed together, equilibrated, and then analyzed by DSF. The Tm from the combined runs was identical to that of particles analyzed separately (Fig. 3), indicating that no unexpected solution conditions were responsible for the dramatic differences observed. Since temperature is often used to induce exposure of VP1u, the next step was to correlate Tm with particle integrity.

Fig 3.

DSF measurements of fluorescence intensity during heating of an AAV serotype mixture. AAV2 and AAV5 show distinct melting temperatures when analyzed as a mixture after coincubation for 2 h. Data are the normalized averages from three temperature scan experiments. The curve for expected results was calculated by linear addition of melting profiles of pure serotype reactions shown in Fig. 2.

Visualization by negative-stain EM is a suitable method for studying protein complexes and can be used to detect structural differences in viruses (63, 64). This approach was recently used to follow conformational changes in AAV particles upon heating and to assess particle integrity (65). A heat pulse of 3 min at different temperatures was used, because this is the standard treatment to externalize the VP1u and VP1/VP2 common region of AAV particles to characterize the phospholipase activity of VP1u and to detect these regions by antibodies (34, 66). From 37°C to 65°C there was no evidence of particle clumping or degradation for any of the serotypes (Fig. 4). For AAV2 and AAV8, the particles had denatured and were not observed by 75°C. For AAV1 and AAV5, the particles remained intact to 75 and 85°C, respectively. All the serotypes were denatured at 95°C. This experiment revealed a clear differential thermal stability of the AAV particles analyzed. The loss of capsid integrity observed in the postheating electron micrographs correlated with the Tm values determined by DSF and DSC (Table 1; Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

Thermal stability of AAV particles after heating. AAV capsids were heated at 37, 45, 65, 75, and 85°C for 3 min and then analyzed by negative-stain electron microscopy. Representative images at a magnification of ×31,000 show a serotype dependence on the temperature at which morphological changes, including complete disruption, occur. Heating experiments were repeated 3 times using particles from different virus preparations. Images were selected to show presence or absence of intact particles, not total number across grids.

The large differences observed in AAV thermal stability were not explained by DNA packaging, method of production, or the presence of copurifying solute molecules; therefore, we looked more closely at the capsid structural models for insight. Two factors that contribute to capsid stability, and in general to the stability of protein complexes, are subunit contact energies (67, 68) and free energy of subunit folding (69). To investigate the contribution of these factors to AAV capsid stability, subunit association energies and buried surface area for each of the AAVs analyzed were compared. Values for each unique icosahedral interface were obtained from the VIPER database (70), and from these, values for whole capsids were computed (Table 2). No correlation between Tm and buried surface area, association energy, or a combination of the two was evident. For example, AAV5 which had the highest Tm has lower values for both buried surface area and association energy than either AAV2 or AAV8. The lack of a correlation between solution phase properties and crystal structure contact data is consistent with studies looking at particle assembly and disassembly as reported for other nonenveloped virus capsids (68). One factor missing from this analysis was information about conformational plasticity. Protein structures determined by X-ray crystallography contain information on local dynamics as atomic displacement values or B factors, which reflect the fluctuations of atoms around their average positions. While direct comparisons of B factors between structural models derived from different solution conditions and crystal packings should be used with caution, a brief review shows that AAV2 (PDB ID: 1LP3) had much larger values overall than AAV1, -5, or -8 (PDB IDs: 3NG9, 3NTT, and 2QA0, respectively). This suggested that AAV2 may be a more flexible protein complex.

Table 2.

Subunit contact energy and area as calculated by VIPER (virus particle explorer)

| Virus | Association energy (kcal/mol) |

Buried surface area (nm2) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-fold axis | 3-fold axis | 5-fold axis | Total capsid | 2-fold axis | 3-fold axis | 5-fold axis | Total capsid | |

| AAV1 | −55 | −215 | −95 | −21,900 | 28 | 103 | 48 | 10,760 |

| AAV2 | −65 | −215 | −100 | −22,600 | 31 | 103 | 49 | 11,020 |

| AAV5 | −50 | −210 | −100 | −21,700 | 26 | 99 | 49 | 10,490 |

| AAV8 | −75 | −215 | −105 | −23,400 | 34 | 103 | 51 | 11,360 |

Capsid protein dynamics.

Inspired by the differences in the response of AAVs to temperature, limited-proteolysis experiments to characterize solution-phase dynamics of the capsids were initiated (71–73). Proteinase K, which has low sequence specificity, was used in the initial comparison of the AAV serotypes. Our interest was in the initial cleavage events, when the majority of capsid protein was intact. Time course reactions of each AAV serotype with protease were analyzed by SDS-PAGE after 10- and 60-min incubations with proteinase K (Fig. 5A). AAV1 and AAV2 produced a stable band at ∼55 kDa that was absent in AAV5 and AAV8, while AAV2 and AAV5 had a stable band at ∼33 kDa, and a slightly larger product (∼37 kDa) was seen with AAV8. A number of less prominent bands unique to each serotype appear as well, such as the band at approximately 40 kDa in AAV2. The different band patterns show that each serotype has a unique landscape of relative dynamics, which is consistent with a report that trypsin and chymotrypsin could distinguish AAV2 from AAV1 and AAV5 (40). A difference in capsid dynamics is also consistent with the predicted differences in intrinsic disorder between AAV5 and the other serotypes, as tested by Venkatakrishnan et al. (74). Densitometry of the intact VP3 in each lane of the gel from the proteinase K digestion of the AAV capsids confirmed the visual differences in the amount of protein remaining (Fig. 5B). VP3 of AAV1 and -2 was hydrolyzed most rapidly, with only ∼60% remaining after 60 min. AAV5 and -8 were hydrolyzed more slowly, with >80% remaining after exposure to the protease for 60 min. There was no straightforward relationship between thermal stability and susceptibility to proteolysis.

Fig 5.

Proteolysis of AAV serotypes monitored using SDS-PAGE. (A) SDS-PAGE gel for the 4 serotypes, proteinase K (PK), and bovine serum albumin (BSA). Each serotype was subjected to proteinase K treatment at three time points (0, 10, and 60 min). Bands a, b, and c have molecular masses of 55 kDa, 37 kDa, and 33 kDa, respectively. (B) Graphical representation of the proteolytic trends of the 4 serotypes observed on the gels, with the x axis showing time and y axis the relative intensity. Error bars show ±1 standard deviation.

To identify the dynamic regions of the VPs, the limited-proteolysis experiment was repeated using trypsin and chymotrypsin. These proteases have higher specificity than proteinase K which greatly simplifies unequivocal identification of cleavage sites using mass spectrometry. Using the data from the trypsin experiment, the cleavage sites were mapped onto the full-length VP1 sequence (Table 4). As presented, residues in the same row in Table 4 are analogous across serotypes. The cleavage sites shown represent less than 25% of the possible positions for proteolysis, with lysine and arginine residues being distributed throughout the VP in each serotype (Fig. 6). A significant observation is that the majority of the sites in each serotype were common with at least one other serotype (Tables 3 and 4). Observed differences included the VP1u region of AAV2, which had fewer cleavage events than the other serotypes and the C-terminal end of AAV5 (residues 484 to 724) with no cleavage. The data from AAV2 is consistent with the one other study to map exogenous protease sites, with residues 566, 585, and 588 being among the very first sites to be cleaved (40).

Table 4.

Initial protease cleavage sites on AAV capsids

| Region | Position and residue inb: |

VR or motifc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAV1 | AAV2 | AAV5 | AAV8 | ||

| VP1u | 39, K | ||||

| 42, R | 1 | ||||

| 51, K | 51, K | 2 | |||

| 61, K | 60, R | 61, K | |||

| 77, K | |||||

| 84, K | |||||

| 92, R | 91, K | 92, R | 3 | ||

| 103, R | 102, K | 103, R | |||

| 116, R | 115, K | 116, R | |||

| 122, K | 121, K | ||||

| 123, K | |||||

| VP1/2 | 142, K | 143, R | 142, K | ||

| 153, K | 152, R | ||||

| 161, K | 4 | ||||

| VP3 | 235, R, | ||||

| 248, R | |||||

| 425, K | 435, R | ||||

| 437, R | |||||

| 450, R | |||||

| 451, K; 456, R | IV | ||||

| 459, R | IV | ||||

| 476, K | 475, R | 462, K | 478, K | IV | |

| 485, R | 471, R | ||||

| 483, R | |||||

| 490, R | V | ||||

| 491, K | V | ||||

| 507, K | 510, K | ||||

| 513, R | 516, R | ||||

| 532, K | 535, R | VI | |||

| 545, K | 544, K | 547, K | VII | ||

| 567, K | 566, R | ||||

| 576, R | |||||

| 585, R; 588, R | VIII | ||||

| 609, R | 612, R | ||||

| 621, K | 620, K | 623, K | |||

Sites are presented from the N terminus to the C terminus (top to bottom of the table). Sites in bold type are present in the structural models and are highlighted in Fig. 6; others are in the VP1 and VP2 N-terminal domains. Residues unique to one serotype are italicized.

R, arginine; K, lysine.

Motifs predicted by Popa-Wagner et al. (41) to be functionally important are labeled as follows: 1, sorting signal (dileucine motif); 2, sorting signal (YXXϕ); 3, SH2-binding domain; and 4, FHA-binding domain. Residues in VRs are indicated with roman numerals.

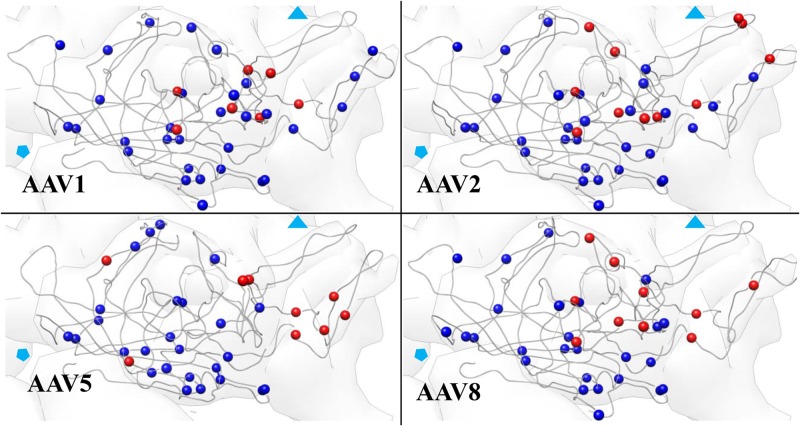

Fig 6.

Distribution of potential and observed protease sites in VP3. The position of potential trypsin cleavage sites in each AAV are shown in blue, and lysines and arginines at which cleavage occurs are shown in red. Solid symbols show the position of the 3- and 5-fold symmetry axes.

Table 3.

Numbers of cleavage sites shared between serotypes

| Region | No. of shared cleavages/no. of total cleavages |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAV1 | AAV2 | AAV5 | AAV8 | |

| VP1 | 5/8 | 1/2 | 5/6 | 4/5 |

| VP2 | 2/2 | 0 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| VP3 | 5/7 | 8/11 | 3/9 | 8/10 |

| Full protein | 12/17 | 9/13 | 10/17 | 14/17 |

To initiate a structure-function analysis of the dynamic regions of the VP identified with proteolysis, the location of the cleavage sites were mapped on to the available VP3 structural models. Figure 7A depicts the cleavage sites for AAV2 which had the same general pattern as those observed on the VP3 of the other serotypes analyzed (Fig. 6). Across the 4 serotypes, a number of the cleavage sites were located in the structurally variable regions (Table 4). A subset of residues was located below the surface loops. This included AAV1 476 and 567; AAV2 475, 566, 609, and 620; AAV5 235; and AAV8 435. Visual inspection suggested that the sites clustered around the protrusions that surround the icosahedral 3-fold axes (Fig. 7C; also, see Movie S1 in the supplemental material). Residues 585 and 588 in AAV2 are located on the side of the protrusion and are critical for heparan sulfate recognition (15–17, 97), transduction efficiency, and tissue tropism, suggesting a connection between protein dynamics and receptor binding. Distance measurements from the sites of cleavage to the icosahedral 2-, 3-, and 5-fold axes confirmed that the residues clustered near the 3-fold axes at an average distance of ∼25 Å (Fig. 7B). These observations establish the protrusions surrounding the 3-fold axis as a dynamic region and indicate that the protein motion within this capsid region is sufficient to translocate buried residues to the surface. Cleavage sites also were present in the VP1u and VP1/VP2 common regions which are not ordered in any of the crystal structures determined to date. These domains are believed to be internalized at least until the cellular entry process begins (34, 75). It is important to note that the cleavage locations shown in Fig. 6 and 7 represent the initial ∼10 to 20% of the cleavage reaction (80 to 90% of VP3 remained intact), which corresponds to less than 10 min for the reactions shown in Fig. 5. The particles remain intact based on size exclusion chromatography (data not shown), which is consistent with the report by Van Vliet et al. (40) and similar experiments conducted on canine parvovirus (59).

Fig 7.

Icosahedral locations of cleavage sites. (A) Top and side views of 3 subunits of AAV2 VP3. Proteolytic sites on each subunit are marked with a different color. The hollow black symbols indicate the approximate symmetry fold axes. (B) Average distance (Å) of the cleaved residues shown in panel A from each icosahedral symmetry axis. (C) Representative image of the icosahedral symmetry axes (f, fold; l, left; r, right; m, main) and the approximate distances of a representative residue (609 of AAV2) from each of these axes.

DISCUSSION

Structural virology has been a cornerstone for understanding virus particle assembly, receptor binding, and cell entry ever since the model for quasi-equivalence was put forth (77). Slowly, it became evident that in addition to structure, dynamics is an integral part of VP function (16, 40, 71, 72, 75, 78–82). This study focused on characterizing the solution phase properties of four AAV serotypes for which high-resolution structures are available. A premise behind this work was that structural differences and sequence variations between the serotypes could impart differences to the solution phase properties of the particles. Our experiments revealed that broad similarities were punctuated by specific differences between serotypes. For example, the surface protrusions surrounding the 3-fold axes of symmetry were dynamic in all of the serotypes, while the VP1u domain of AAV2 appeared to have less surface exposure than in the other serotypes. Capsid melting temperatures showed Tm variation of >20°C. We believe that the observed differences in capsid VP stability and dynamics may have implications for the activation of lipase activity and genome release during cell entry, both of which could influence cell type and tissue specificity. In addition to highlighting biological differences, biophysical studies can direct the use and development of serotypes with optimal stability to improve production of AAV for therapeutic uses, extend the shelf life of vectors, and enhance transduction efficiency.

Thermal denaturation of assembled capsids monitored by DSF, DSC, and EM showed that the Tms of the least and most stable AAV serotype tested differed by >20°C. We are unaware of similar data for other viruses that are naturally occurring variants in a population. The differences cannot be accounted for by simply looking at protein sequence similarity, as AAV5 is equally different from AAV1, AAV2, and AAV8. Thermal disassembly of a virus particle or any protein complex can be separated into at least two distinct events, disruption of subunit contacts and protein unfolding. Formation of a multimeric complex can add thermodynamic and thermal stability to proteins (83), and the stabilization provided by subunit-subunit contacts can raise the Tm of the complex significantly above the point where a monomeric subunit is stable. Hence, thermal denaturation curves for complexes may show only a single sharp transition, because once disassembly begins, unfolding of the monomers is rapid because they are well above their Tm. The DSF curves for each serotype have a sharp transition in which the fluorescence increases to maximum in only a few degrees, suggesting cooperative two-state behavior (Fig. 2). Similar transitions are observed in the DSC measurements as well, except for AAV8, which shows a doublet. This could be an indication that for AAV8, particle disassembly and subunit unfolding can be separated, that thermodynamically distinct particles were present, or that a second transition occurs which does not expose buried hydrophobic patches, so that it is not detectable in the DSF assay. Together, the DSF and DSC data are highly consistent. The application of DSF to the study of virus particles is relatively new (84, 85). The results presented here together with the small sample volume and parallel nature of the assay suggest that it is an efficient method for the characterization of capsid thermal stability. EM images served as a third approach for following particle denaturation, with the transition temperatures observed by DSF and DSC being consistent with visual loss of particle integrity from negative stain EM imaging.

Two forms of each AAV serotype were investigated by DSF. The VLPs contain heterologous cellular DNA, whereas the rAAV have the GFP genome packaged so that transduction efficiency can be monitored. Our DSF data show that for AAV1, AAV2, AAV5, and AAV8, VLPs and recombinant capsid behave similarly. Structural studies of AAV8 VLPs and rAAV vectors have shown interactions between ordered nucleotides and the capsid protein on the inner surface of the capsid and that specific conformational changes related to pH and endocytosis occur (86). Together, the data from structural and DSF analysis suggest that capsid protein-nucleic acid interaction in AAVs may not depend on viral genome sequence with respect to capsid stability. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that sequence-dependent DNA-protein interactions occur as pH drops. Our observations make the analysis of VLPs relevant to those of DNA-containing virions.

Conformational changes are also part of the normal solution-phase behavior for each of the AAVs we investigated. This was shown by the limited-proteolysis experiments conducted at 25°C. Serotype-dependent patterns of cleavage and susceptibility were evident upon proteinase K treatment (Fig. 5). This extends previous work that showed that it was possible to distinguish AAV1, -2, and -5 based on banding patterns using trypsin and chymotrypsin (40). When it is used in limited-proteolysis experiments, the relatively low sequence specificity of proteinase K minimizes sequence bias, emphasizing differences in the dynamic landscape of proteins. The different banding patterns in Fig. 5 show that subtle differences in the dynamic regions exist between capsids. AAV1 and AAV2 are more rapidly digested, based on the rate of VP3 hydrolysis, indicating that they may be more dynamic than AAV5 and AAV8 (72, 73). While it is perhaps intuitive that there should be a correlation between thermal stability and limited conformational freedom, this is not required by thermodynamics or kinetics. As observed for the AAV serotypes, the different rank order in thermal versus proteolytic stability indicates a separation of local conformational fluctuations from global stability. Consistent with this possibility, AAV8 has been reported to uncoat its capsid faster than AAV2 while our data indicate that the latter virus is less thermally stable (106).

Shifting to a highly sequence-specific protease allowed the kinetically favored cleavage sites to be precisely mapped onto the protein sequence. The first sites of cleavage in VP3 by trypsin cluster around the 3-fold axes of symmetry (Fig. 6). In this region, AAV5 differs from the other serotypes by the lack of observable cleavage (Table 4). AAV5 is also different with respect to the 3-fold protrusion, which is less pronounced than in the other serotypes (45, 104), and it is predicted to have a strong propensity for disorder across VR5 to -8 based on PONDR (74). Data from mutagenesis and structural studies localize the known primary receptor binding sites to the region surrounding the 3-fold axis (15–17, 19, 88, 97). Protein flexibility plays an important role in receptor binding for a wide range of viruses (78, 89), and the data presented here are consistent with what is known about AAV capsid-receptor interactions. Structural studies of AAV2 show that the binding of heparin induces a conformation change at the 3-fold and also distally at the 5-fold axes (16). Structural studies of AAV1 and AAV2 with neutralizing antibodies also map antigenic epitopes to the 3-fold region (105). Our proteolytic map also overlies a recent cryo-EM reconstruction of AAV8 in complex with a neutralizing antibody, which highlights the 3-fold region as an important antigenic determinant as well (90). Residues on the 3-fold protrusions of AAV8 also determine receptor binding and transduction efficiency (19, 90, 91). Cleavage sites near the 5-fold axis did not show up in our maps, indicating that this region is not highly dynamic under the conditions use this region is dynamic under certain conditions, because conformational diversity is present in structural models (1, 3). The 5-fold axis has been implicated in externalization of the VP1u PLA2 domain and genome release, both of which would require substantial remodeling of the 5-fold axis (75, 87, 92). This suggests that the heparin-induced conformational changes at the AAV2 5-fold axis must be triggered. Such a model is consistent with the idea that mature icosahedral capsids are metastable complexes poised to initiate the entry process in response to an external trigger (63, 93).

Cleavages also mapped to the VP1u and VP1/2 common regions. In these domains AAV2 is different from the other AAV serotypes in having only two cleavage sites compared to the seven or more in the other viruses. The identification of cleavages on these regions even though the particles have not undergone heat treatment has three possible explanations: (i) the VP1 N terminus is transiently exposed on the capsid surface, (ii) a small population of broken particles are present, or (iii) proteolysis leads to externalization of the VP1 N terminus. Transient externalization of capsid protein domains that are buried in structural models is well documented in icosahedral viruses, is consistently linked with protein domains involved with cell entry (71, 72, 79, 94), and is specifically relevant to parvoviruses due to the requirement of this transition for successful cellular infection (59, 94). This could explain the presence of cleavages in the VP1u region but is contrary to immunoblotting data obtained with monoclonal antibody A1, which indicates that the AAV2 VP1u cannot be detected unless particles have been heated or disrupted (34, 40, 75). It is possible that the “native” orientation of externalized VP1u conceals the A1 epitope until heat treatment. With respect to option 2, aggregated or broken particles were not detected by size exclusion analysis of purified AAVs, and because VP1 makes up less than 10% of the total protein, a significant percentage of capsids would need to be damaged for VP1u cleavages to be detectable in comparison to VP3. The third option is supported by data showing that cathepsins are important uncoating factors for AAV2 and AAV8. AAV2 VP3 cleavage by the endosomal proteases cathepsin B and L can occur in vivo and in vitro (76). Consistent with our data, particles remain intact after cathepsin proteolysis, and the products are serotype specific. The bands generated by exposure of AAV2 and AAV8 to cathepsin L closely match the major products of proteinase K treatment at 33 and 37 kDa for AAV2 and AAV8, respectively, after 10 and 60 min (Fig. 5). The study by Akache et al. also showed that AAV5 does not interact with cathepsin B or L but likely relies on a different cellular protease. However, a band very similar in size to the proteinase K product of AAV2 was also present in AAV5. In the experiments by Van Vliet et al. (40), trypsin and chymotrypsin failed to generate a stable band close in molecular weight to that generated by cathepsin or proteinase K (40). It is tempting to speculate that proteinase K cleavage mimics host-mediated processing during endocytosis. An additional factor that must be considered is autohydrolysis of AAV VPs. This was recently described for nine of the AAV serotypes (39). Bands originating from the degradation of VPs increase with time on SDS-PAGE gels. Similar behavior has been reported for canine parvovirus as well (59). In AAV, the VPs take an active role in the proteolysis, adding an interesting twist to the findings reported here. Two of the primary sites of autohydrolysis are at the 5-fold axis (219 in AAV1 and 657 in AAV9 numbering). Our data suggest that at neutral pH, this region is not highly dynamic, raising the possibility that the role of autohydrolysis is to increase dynamics around the 5-fold axis during trafficking. Our results support the hypothesis that proteolysis is a trigger for externalization of VP1u, as was also recently suggested based on the identification of a protease function in AAV2 (39).

Through a series of complementary approaches, we discovered that the thermal stability and capsid protein dynamics of AAVs are serotype specific. The biological force(s) responsible for driving the biophysical divergence between serotypes is unclear at this time. What is known is that sequence differences in the VRs contribute to phenotypic differences, including receptor attachment, transduction efficiency, and antigenic reactivity (1, 3, 4, 88, 90, 91, 95, 96, 105). We hypothesize that the observed biophysical differences between serotypes are connected to the specific biology of each serotype. These results are also a starting point for the characterization of particle integrity, thermal and thermodynamic stability, and conformational dynamics under conditions encountered during infection which together are the basis for establishing protocols that can be used to compare AAV serotypes, assess factors that affect particle integrity, and determine suitability of products for use in gene therapy. Our findings raise important questions about the relationship of structure to function beyond AAVs and emphatically point out the functional complexity of virus capsids.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

B.B., M.A.M., and R.M. receive support from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI081961-01A1) and the Center for Bio-Inspired Nanomaterials (Office of Naval Research grant N00014-06-01-1016). The AAV1 and AAV5 structure determinations were supported by NIH R01 NIH R01 GM082946 to M.A.M. and R.M. We thank the Murdock Charitable Trust and acknowledge NIH grants P20 RR-020185 and 1P20RR024237 from the COBRE Program of the National Center For Research Resources for support of the MSU mass spectrometry facility. S.K. received support from the Montana NIH InBRE program for undergraduate scholars.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 September 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01415-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Halder S, Ng R, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2012. Parvoviruses: structure and infection. Future Virol. 7:253–278 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muzyczka N, Berns KI. 2001. Parvoviridae: the viruses and their replication, p 2327–2360 In Knipe DM, Howley PM. (ed), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agbandje-McKenna M, Kleinschmidt J. 2011. AAV capsid structure and cell interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 807:47–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agbandje-McKenna M, Chapman MS. 2006. Correlating structure with function in the viral capsid, p 125–139 In Kerr JR, Cotmore SF, Bloom ME, Linden R, Parrish CR. (ed), Parvoviruses. Hodder Arnold Publication, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao G, Vandenberghe LH, Alvira MR, Lu Y, Calcedo R, Zhou X, Wilson JM. 2004. Clades of adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J. Virol. 78:6381–6388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao G-P, Alvira MR, Wang L, Calcedo R, Johnston J, Wilson JM. 2002. Novel adeno-associated viruses from rhesus monkeys as vectors for human gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:11854–11859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mori S, Wang L, Takeuchi T, Kanda T. 2004. Two novel adeno-associated viruses from cynomolgus monkey: pseudotyping characterization of capsid protein. Virology 330:375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reference deleted.

- 9.Schmidt M, Voutetakis A, Afione S, Zheng C, Mandikian D, Chiorini JA. 2008. Adeno-associated virus type 12 (AAV12): a novel AAV serotype with sialic acid- and heparan sulfate proteoglycan-independent transduction activity. J. Virol. 82:1399–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Vliet KM, Blouin V, Brument N, Agbandje-McKenna M, Snyder RO. 2008. The role of the adeno-associated virus capsid in gene transfer. Methods Mol. Biol. 437:51–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mingozzi F, High KA. 2011. Therapeutic in vivo gene transfer for genetic disease using AAV: progress and challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12:341–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maguire AM, Simonelli F, Pierce EA, Pugh EN, Mingozzi F, Bennicelli J, Banfi S, Marshall KA, Testa F, Surace EM, Rossi S, Lyubarsky A, Arruda VR, Konkle B, Stone E, Sun J, Jacobs J, Dell'Osso L, Hertle R, Ma J, Redmond TM, Zhu X, Hauck B, Zelenaia O, Shindler KS, Maguire MG, Wright JF, Volpe NJ, McDonnell JW, Auricchio A, High KA, Bennett J. 2008. Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber's congenital amaurosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 358:2240–2248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chao H, Liu Y, Rabinowitz J, Li C, Samulski RJ, Walsh CE. 2000. Several log increase in therapeutic transgene delivery by distinct adeno-associated viral serotype vectors. Mol. Ther. 2:619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson BL, Stein CS, Heth JA, Kotin RM, Derksen TA, Zabner J, Ghodsi A, Chiorini JA. 2000. Recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2, 4, and 5 vectors: transduction of variant cell types and regions in the mammalian central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:3428–3432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kern A, Schmidt K, Leder C, Muller OJ, Wobus CE, Bettinger K, Von der Lieth CW, King JA, Kleinschmidt JA. 2003. Identification of a heparin-binding motif on adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids. J. Virol. 77:11072–11081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy HC, Bowman VD, Govindasamy L, McKenna R, Nash K, Warrington K, Chen W, Muzyczka N, Yan X, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2009. Heparin binding induces conformational changes in adeno-associated virus serotype 2. J. Struct. Biol. 165:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Opie SR, Warrington JKH, Agbandje-McKenna M, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N. 2003. Identification of amino acid residues in the capsid proteins of adeno-associated virus type 2 that contribute to heparan sulfate proteoglycan binding. J. Virol. 77:6995–7006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Summerford C, Samulski RJ. 1998. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J. Virol. 72:1438–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akache B, Grimm D, Pandey K, Yant SR, Xu H, Kay MA. 2006. The 37/67-kilodalton laminin receptor is a receptor for adeno-associated virus serotypes 8, 2, 3, and 9. J. Virol. 80:9831–9836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asokan A, Hamra JB, Govindasamy L, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. 2006. Adeno-associated virus type 2 contains an integrin α5β1 binding domain essential for viral cell entry. J. Virol. 80:8961–8969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kashiwakura Y, Tamayose K, Iwabuchi K, Hirai Y, Shimada T, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Watanabe M, Oshimi K, Daida H. 2005. Hepatocyte growth factor receptor is a coreceptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. J. Virol. 79:609–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qing K, Mah C, Hansen J, Zhou S, Dwarki V, Srivastava A. 1999. Human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is a co-receptor for infection by adeno-associated virus 2. Nat. Med. 5:71–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reference deleted.

- 24. Reference deleted.

- 25.Summerford C, Bartlett JS, Samulski RJ. 1999. αVβ5 integrin: a co-receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. Nat. Med. 5:78–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nonnenmacher M, Weber T. 2011. Adeno-associated virus 2 infection requires endocytosis through the CLIC/GEEC pathway. Cell Host Microbe 10:563–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lerch TF, Xie Q, Chapman MS. 2010. The structure of adeno-associated virus serotype 3B (AAV-3B): insights into receptor binding and immune evasion. Virology 403:26–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blackburn SD, Steadman RA, Johnson FB. 2006. Attachment of adeno-associated virus type 3H to fibroblast growth factor receptor 1. Arch. Virol. 151:617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaludov N, Brown KE, Walters RW, Zabner J, Chiorini JA. 2001. Adeno-associated virus serotype 4 (AAV4) and AAV5 both require sialic acid binding for hemagglutination and efficient transduction but differ in sialic acid linkage specificity. J. Virol. 75:6884–6893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Z, Miller E, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. 2006. Alpha2,3 and alpha2,6 N-linked sialic acids facilitate efficient binding and transduction by adeno-associated virus types 1 and 6. J. Virol. 80:9093–9103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walters RW, Yi SMP, Keshavjee S, Brown KE, Welsh MJ, Chiorini JA, Zabner J. 2001. Binding of adeno-associated virus type 5 to 2,3-linked sialic acid is required for gene transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20610–20616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Pasquale G, Davidson BL, Stein CS, Martins I, Scudiero D, Monks A, Chiorini JA. 2003. Identification of PDGFR as a receptor for AAV-5 transduction. Nat. Med. 9:1306–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen S, Bryant KD, Brown SM, Randell SH, Asokan A. 2011. Terminal N-linked galactose is the primary receptor for adeno-associated virus 9. J. Biol. Chem. 286:13532–13540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sonntag F, Bleker S, Leuchs B, Fischer R, Kleinschmidt AJ. 2006. Adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids with externalized VP1/VP2 trafficking domains are generated prior to passage through the cytoplasm and are maintained until uncoating occurs in the nucleus. J. Virol. 80:11040–11054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buller RM, Rose JA. 1978. Characterization of adenovirus-associated virus-induced polypeptides in KB cells. J. Virol. 25:331–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rose JA, Maizel JV, Inman JK, Shatkin AJ. 1971. Structural proteins of adenovirus-associated viruses. J. Virol. 8:766–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chapman MS, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2006. Atomic structure of viral particles, p 107–123 In Kerr JR, Cotmore SF, Bloom ME, Linden R, Parrish CR. (ed), Parvoviruses. Edward Arnold Ltd., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naumer M, Sonntag F, Schmidt K, Nieto K, Panke C, Davey NE, Popa-Wagner R, Kleinschmidt JA. 2012. Properties of the AAV assembly-activating protein AAP. J. Virol. 86:13038–13048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salganik M, Venkatakrishnan B, Bennett A, Lins B, Yarbrough J, Muzyczka N, Agbandje-McKenna M, McKenna R. 2012. Evidence for pH-dependent protease activity in the adeno-associated virus capsid. J. Virol. 86:11877–11885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Vliet K, Blouin V, Agbandje-McKenna M, Snyder RO. 2006. Proteolytic mapping of the adeno-associated virus capsid. Mol. Ther. 14:809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Popa-Wagner R, Porwal M, Kann M, Reuss M, Weimer M, Florin L, Kleinschmidt JA. 2012. Impact of VP1-specific protein sequence motifs on adeno-associated virus type 2 intracellular trafficking and nuclear entry. J. Virol. 86:9163–9174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bleker S, Pawlita M, Kleinschmidt JA, Kleinschmidt A. 2006. Impact of capsid conformation and Rep-capsid interactions on adeno-associated virus type 2 genome packaging. J. Virol. 80:810–820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Govindasamy L, Padron E, McKenna R, Muzyczka N, Kaludov N, Chiorini JA, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2006. Structurally mapping the diverse phenotype of adeno-associated virus serotype 4. J. Virol. 80:11556–11570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ng R, Govindasamy L, Gurda BL, McKenna R, Kozyreva OG, Samulski RJ, Parent KN, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2010. Structural characterization of the dual glycan binding adeno-associated virus serotype 6. J. Virol. 84:12945–12957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walters RW, Agbandje-McKenna M, Bowman VD, Moninger TO, Olson NH, Seiler M, Chiorini JA, Baker TS, Zabner J. 2004. Structure of adeno-associated virus serotype 5. J. Virol. 78:3361–3371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xie Q, Bu W, Bhatia S, Hare J, Somasundaram T, Azzi A, Chapman MS. 2002. The atomic structure of adeno-associated virus (AAV-2), a vector for human gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:10405–10410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nam H-J, Lane MD, Padron E, Gurda B, McKenna R, Kohlbrenner E, Aslanidi G, Byrne B, Muzyczka N, Zolotukhin S, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2007. Structure of adeno-associated virus serotype 8, a gene therapy vector. J. Virol. 81:12260–12271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu Z, Asokan A, Grieger JC, Govindasamy L, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. 2006. Single amino acid changes can influence titer, heparin binding, and tissue tropism in different adeno-associated virus serotypes. J. Virol. 80:11393–11397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Reference deleted.

- 50. Reference deleted.

- 51.DiMattia M, Govindasamy L, Levy HC, Gurda-Whitaker B, Kalina A, Kohlbrenner E, Chiorini JA, McKenna R, Muzyczka N, Zolotukhin S, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2005. Production, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray structural studies of adeno-associated virus serotype 5. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F 61:917–921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kohlbrenner E, Aslanidi G, Nash K, Shklyaev S, Campbell-Thompson M, Byrne BJ, Snyder RO, Muzyczka N, Warrington KH, Zolotukhin S. 2005. Successful production of pseudotyped rAAV vectors using a modified baculovirus expression system. Mol. Ther. 12:1217–1225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lane MD, Nam H-J, Padron E, Gurda-Whitaker B, Kohlbrenner E, Aslanidi G, Byrne B, McKenna R, Muzyczka N, Zolotukhin S, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2005. Production, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of adeno-associated virus serotype 8. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F 61:558–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller EB, Gurda-Whitaker B, Govindasamy L, McKenna R, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2006. Production, purification and preliminary X-ray crystallographic studies of adeno-associated virus serotype 1. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F 62:1271–1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mah C, Fraites JTJ, Zolotukhin I, Song S, Flotte TR, Dobson J, Batich C, Byrne BJ. 2002. Improved method of recombinant AAV2 delivery for systemic targeted gene therapy. Mol. Ther. 6:106–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zolotukhin S, Potter M, Zolotukhin I, Sakai Y, Loiler S, Fraites TJ, Chiodo VA, Phillipsberg T, Muzyczka N, Hauswirth WW, Flotte TR, Byrne BJ, Snyder RO. 2002. Production and purification of serotype 1, 2, and 5 recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Methods 28:158–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yeh AP, McMillan A, Stowell MHB. 2006. Rapid and simple protein-stability screens: application to membrane proteins. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62:451–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Reference deleted.

- 59.Nelson CDS, Minkkinen E, Bergkvist M, Hoelzer K, Fisher M, Bothner B, Parrish CR. 2008. Detecting small changes and additional peptides in the canine parvovirus capsid structure. J. Virol. 82:10397–10407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Reference deleted.

- 61.Bothner B, Schneemann A, Marshall D, Reddy V, Johnson JE, Siuzdak G. 1999. Crystallographically identical virus capsids display different properties in solution. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 6:114–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rayaprolu V, Manning BM, Douglas T, Bothner B. 2010. Virus particles as active nanomaterials that can rapidly change their viscoelastic properties in response to dilute solutions. Soft Matter 6:5286–5288 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Belnap DM, Filman DJ, Trus BL, Cheng N, Booy FP, Conway JF, Curry S, Hiremath CN, Tsang SK, Steven AC, Hogle JM. 2000. Molecular tectonic model of virus structural transitions: the putative cell entry states of poliovirus. J. Virol. 74:1342–1354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gan L, Speir JA, Conway JF, Lander G, Cheng N, Firek BA, Hendrix RW, Duda RL, Liljas L, Johnson JE. 2006. Capsid conformational sampling in HK97 maturation visualized by X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM. Structure 14:1655–1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Horowitz ED, Rahman KS, Bower BD, Dismuke DJ, Falvo MCR, Griffith JD, Harvey SC, Asokan A. 2013. Biophysical and ultrastructural characterization of adeno-associated virus capsid uncoating and genome release. J. Virol. 87:2994–3002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu P, Xiao WW, Conlon T, Hughes J, Agbandje-McKenna M, Ferkol T, Flotte T, Muzyczka N. 2000. Mutational analysis of the adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) capsid gene and construction of AAV2 vectors with altered tropism. J. Virol. 74:8635–8647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Endres D, Zlotnick A. 2002. Model-based analysis of assembly kinetics for virus capsids or other spherical polymers. Biophys. J. 83:1217–1230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zlotnick A. 2003. Are weak protein-protein interactions the general rule in capsid assembly? Virology 315:269–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ausar SF, Foubert TR, Hudson MH, Vedvick TS, Middaugh CR. 2006. Conformational stability and disassembly of Norwalk virus-like particles. J. Biol. Chem. 281:19478–19488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carrillo-Tripp M, Shepherd CM, Borelli IA, Venkataraman S, Lander G, Natarajan P, Johnson JE, Brooks CL, Reddy VS. 2009. VIPERdb2: an enhanced and web API enabled relational database for structural virology. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D436–D442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bothner B, Dong XF, Bibbs L, Johnson JE, Siuzdak G. 1998. Evidence of viral capsid dynamics using limited proteolysis and mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 273:673–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hilmer JK, Zlotnick A, Bothner B. 2008. Conformational equilibria and rates of localized motion within hepatitis B virus capsids. J. Mol. Biol. 375:581–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Park C, Marqusee S. 2004. Probing the high energy states in proteins by proteolysis. J. Mol. Biol. 343:1467–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Venkatakrishnan B, Yarbrough J, Domsic J, Bennett A, Bothner B, Kozyreva OG, Samulski RJ, Muzyczka N, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2013. Structure and dynamics of adeno-associated virus serotype 1 VP1-unique N-terminal domain and its role in capsid trafficking. J. Virol. 87:4974–4984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kronenberg S, Bottcher B, von der Lieth CW, Bleker S, Kleinschmidt JA. 2005. A conformational change in the adeno-associated virus type 2 capsid leads to the exposure of hidden VP1 N termini. J. Virol. 79:5296–5303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Akache B, Grimm D, Shen X, Fuess S, Yant SR, Glazer DS, Park J, Kay MA. 2007. A two-hybrid screen identifies cathepsins B and L as uncoating factors for adeno-associated virus 2 and 8. Mol. Ther. 15:330–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Caspar DL, Klug A. 1962. Physical principles in the construction of regular viruses. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 27:1–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fricks CE, Hogle JM. 1990. Cell-induced conformational change in poliovirus: externalization of the amino terminus of VP1 is responsible for liposome binding. J. Virol. 64:1934–1945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fricks CE, Icenogle JP, Hogle JM. 1985. Trypsin sensitivity of the Sabin strain of type 1 poliovirus: cleavage sites in virions and related particles. J. Virol. 54:856–859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Golden JS, Harrison SC. 1982. Proteolytic dissection of turnip crinkle virus subunit in solution. Biochemistry 21:3862–3866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Johnson JE. 2003. Virus particle dynamics. Adv. Protein Chem. 64:197–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kowalski H, Maurer-Fogy I, Vriend G, Casari G, Beyer A, Blaas D. 1989. Trypsin sensitivity of several human rhinovirus serotypes in their low pH-induced conformation. Virology 171:611–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Horton N, Lewis M. 1992. Calculation of the free energy of association for protein complexes. Protein Sci. 1:169–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vedadi M, Niesen FH, Allali-Hassani A, Fedorov OY, Finerty PJ, Wasney GA, Yeung R, Arrowsmith C, Ball LJ, Berglund H, Hui R, Marsden BD, Nordlund P, Sundstrom M, Weigelt J, Edwards AM. 2006. Chemical screening methods to identify ligands that promote protein stability, protein crystallization, and structure determination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:15835–15840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yi G, Vaughan RC, Yarbrough I, Dharmaiah S, Kao CC. 2009. RNA binding by the brome mosaic virus capsid protein and the regulation of viral RNA accumulation. J. Mol. Biol. 391:314–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nam H-J, Gurda BL, McKenna R, Potter M, Byrne B, Salganik M, Muzyczka N, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2011. Structural studies of adeno-associated virus serotype 8 capsid transitions associated with endosomal trafficking. J. Virol. 85:11791–11799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bleker S, Sonntag F, Kleinschmidt JA, Kleinschmidt A. 2005. Mutational analysis of narrow pores at the fivefold symmetry axes of adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids reveals a dual role in genome packaging and activation of phospholipase A2 Activity. J. Virol. 79:2528–2540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lochrie MA, Tatsuno GP, Christie B, McDonnell JW, Zhou S, Surosky R, Pierce GF, Colosi P. 2006. Mutations on the external surfaces of adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids that affect transduction and neutralization. J. Virol. 80:821–834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Skehel JJ, Bayley PM, Brown EB, Martin SR, Waterfield MD, White JM, Wilson IA, Wiley DC. 1982. Changes in the conformation of influenza virus hemagglutinin at the pH optimum of virus-mediated membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 79:968–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gurda BL, Raupp C, Popa-Wagner R, Naumer M, Olson NH, Ng R, McKenna R, Baker TS, Kleinschmidt JA, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2012. Mapping a neutralizing epitope onto the capsid of adeno-associated virus serotype 8. J. Virol. 86:7739–7751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Raupp C, Naumer M, Müller OJ, Gurda BL, Agbandje-McKenna M, Kleinschmidt JA. 2012. The threefold protrusions of AAV8 are involved in cell surface targeting as well as post attachment processing. J. Virol. 86:9396–9408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Farr GA, Tattersall P. 2004. A conserved leucine that constricts the pore through the capsid fivefold cylinder plays a central role in parvoviral infection. Virology 323:243–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bothner B, Taylor D, Jun B, Lee KK, Siuzdak G, Schlutz CP, Johnson JE. 2005. Maturation of a tetravirus capsid alters the dynamic properties and creates a metastable complex. Virology 334:17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zádori Z, Szelei J, Lacoste M-CC, Li Y, Gariépy S, Raymond P, Allaire M, Nabi IR, Tijssen P. 2001. A viral phospholipase A2 is required for parvovirus infectivity. Dev. Cell 1:291–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wu Z, Asokan A, Samulski RJ. 2006. Adeno-associated virus serotypes: vector toolkit for human gene therapy. Mol. Ther. 14:316–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hauck B, Xiao W. 2003. Characterization of tissue tropism determinants of adeno-associated virus type 1. J. Virol. 77:2768–2774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.O'Donnell J, Taylor KA, Chapman MS. 2009. Adeno-associated virus-2 and its primary cellular receptor–cryo-EM structure of a heparin complex. Virology. 385:434–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rabinowitz JE, Rolling F, Li C, Conrath H, Xiao W, Xiao X, Samulski RJ. 2002. Cross-packaging of a single adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 vector genome into multiple AAV serotypes enables transduction with broad specificity. J. Virol. 76:791–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bell CL, Vandenberghe LH, Bell P, Limberis MP, Gao GP, Van Vliet K, Agbandje-McKenna M, Wilson JM. 2011. The AAV9 receptor and its modification to improve in vivo lung gene transfer in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121:2427–2435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schmidt M, Govindasamy L, Afione S, Kaludov N, Agbandje-McKenna M, Chiorini JA. 2008. Molecular characterization of the heparin-dependent transduction domain on the capsid of a novel adeno-associated virus isolate, AAV(VR-942). J. Virol. 82:8911–8916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zincarelli C, Soltys S, Rengo G, Koch WJ, Rabinowitz JE. 2010. Comparative cardiac gene delivery of adeno-associated virus serotypes 1-9 reveals that AAV6 mediates the most efficient transduction in mouse heart. Clin. Transl. Sci. 3:81–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Grieger JC, Snowdy S, Samulski RJ. 2006. Separate basic region motifs within the adeno-associated virus capsid proteins are essential for infectivity and assembly. J. Virol. 80:5199–5210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.DiMattia MA, Nam HJ, Van Vliet K, Mitchell M, Bennett A, Gurda BL, McKenna R, Olson NH, Sinkovits RS, Potter M, Byrne BJ, Aslanidi G, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2012. Structural insight into the unique properties of adeno-associated virus serotype 9. J. Virol. 86:6947–6958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Govindasamy L, Dimattia MA, Gurda BL, Halder S, McKenna R, Chiorini JA, Muzyczka N, Zolotukhin S, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2013. Structural insights into adeno-associated virus serotype 5. J. Virol. 87:11187–11199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gurda BL, DiMattia MA, Miller EB, Bennett A, McKenna R, Weichert WS, Nelson CD, Chen WJ, Muzyczka N, Olson NH, Sinkovits RS, Chiorini JA, Zolotutkhin S, Kozyreva OG, Samulski RJ, Baker TS, Parrish CR, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2013. Capsid antibodies to different adeno-associated virus serotypes bind common regions. J. Virol. 87:9111–9124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Thomas CE, Storm TA, Huang Z, Kay MA. 2004. Rapid uncoating of vector genomes is the key to efficient liver transduction with pseudotyped adeno-associated virus vectors. J. Virol. 78:3110–3122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.