Abstract

Adeno-associated virus 4 (AAV4) is one of the most divergent serotypes among known AAV isolates. Mucins or O-linked sialoglycans have been identified as the primary attachment receptors for AAV4 in vitro. However, little is known about the role(s) played by sialic acid interactions in determining AAV4 tissue tropism in vivo. In the current study, we first characterized two loss-of-function mutants obtained by screening a randomly mutated AAV4 capsid library. Both mutants harbored several amino acid residue changes localized to the 3-fold icosahedral symmetry axes on the AAV4 capsid and displayed low transduction efficiency in vitro. This defect was attributed to decreased cell surface binding as well as uptake of mutant virions. These results were further corroborated by low transgene expression and recovery of mutant viral genomes in cardiac and lung tissue following intravenous administration in mice. Pharmacokinetic analysis revealed rapid clearance of AAV4 mutants from the blood circulation in conjunction with low hemagglutination potential ex vivo. These results were recapitulated with mice pretreated intravenously with sialidase, directly confirming the role of sialic acids in determining AAV4 tissue tropism. Taken together, our results support the notion that blood-borne AAV4 particles interact sequentially with O-linked sialoglycans expressed abundantly on erythrocytes followed by cardiopulmonary tissues and subsequently for viral cell entry.

INTRODUCTION

Adeno-associated viruses (AAV) are small, nonenveloped, single-strand DNA viruses (1). Numerous AAV strains have been isolated from human and primate tissues, several of which have been developed into gene transfer vectors due to their diverse tissue tropisms in preclinical animal models (2). Among different AAV clades known thus far, AAV4 is particularly unique due to its divergent genome sequence and capsid antigenicity (3), capsid structure (4, 5), mucin receptor usage (6, 7), and atypical systemic (8) as well as central nervous system (CNS) tropism in mouse models (9). Specifically, the Cap gene product of AAV4 shares only a low homology with that of AAV2 (∼58%) and other prominent AAV serotypes. The core structure of the AAV4 VP monomer is a seven-stranded beta sheet interconnected by loop regions as seen with other parvoviruses (4). However, the surface topology constituted by the highly dynamic loops on the exterior of the AAV4 capsid is strikingly distinct compared to that of other AAV serotypes. This difference has been suggested to be the underlying cause for the diverse phenotypes displayed by AAV serotypes with regard to receptor usage, immunogenicity, and tissue tropism (10, 11).

The first step in the AAV life cycle involves recognition of cell surface glycans, which serve as primary receptors for infection (10). Currently known glycan receptors for different AAV serotypes include heparan sulfate (HS) for AAV2 (12), AAV3 (13, 14), and AAV6 (15, 16); galactose (Gal) for AAV9 (17, 18); N-linked sialic acids for AAV1 and AAV6 (19) as well as AAV5 (20); and O-linked sialic acids or mucin for AAV4 (6, 7). Despite this wealth of knowledge pertaining to AAV glycan receptor usage in vitro, the influence of tissue glycosylation patterns on AAV tropism is not well understood.

In the current study, we characterized the role(s) played by O-linked sialylated glycans or mucins in determining the systemic transduction profile of AAV4 in mice. We evaluated the functional implications of capsid-sialic acid interactions by using a two-pronged approach involving (i) a comprehensive evaluation of AAV4 mutants deficient in sialic acid binding in vitro and in vivo and (ii) enzymatic removal of tissue and cell surface sialic acids in mice prior to virus administration. Our data support the notion that O-linked sialoglycans play a multifaceted role that extends beyond cell surface attachment of AAV4 and help facilitate cellular uptake, prolonged blood circulation half-life, and the unique cardiopulmonary tropism of this divergent AAV serotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Random mutagenesis.

The AAV4 helper plasmid (pXR4) has been described earlier (14) and was obtained from the UNC Vector Core. Random mutations were introduced into the GH loop (amino acids 428 to 617 on AAV4 VP1; GenBank accession number U89790.1) by error-prone PCR using the GeneMorph II EZ clone domain mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) as described earlier (21). Briefly, 5′-AACCCTCTCATCGACCAGTAC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TCCATCGGTATGAGGAATCTT-3′ (IDT, Coralville, IA) were utilized to randomly mutate and amplify regions within the Cap4 gene that encode the GH loop region. The resulting randomized PCR product was subcloned into the original pXR4 backbone, and individual clones were sequenced by the UNC Genome Analysis Facility. Sequence analysis and alignments were carried out using VectorNTI software (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Molecular modeling.

The three-dimensional structure of AAV4 was displayed as a full icosahedral capsid or trimers using previously published coordinates (Protein Data Bank identification code [PDB ID], 2G8G) in PyMOL (4, 5). Homology models of the two mutants AAV4.18 and AAV4.41 were obtained using the SWISS-MODEL online server (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/) (22), with the crystal structure of AAV4 VP3 (PDB ID 2G8G) serving as a template. The 3-fold symmetry axes/VP3 trimers were generated using the oligomer generator utility in VIPERdb (http://viperdb.scripps.edu/oligomer_multi.php) (23) and visualized using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY). Mutated residues in different capsid variants are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of AAV4 mutants

| Strain | Point mutation(s) on AAV4 VP3 | Titera (VG/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| AAV4 | None | 7.9e11 |

| AAV4.7 | T454S | 3.4e11 |

| AAV4.15 | T496S, S515C, L564P, L588 M, R593G, M603V, I610T | 5.2e11 |

| AAV4.18 | K492E, K503E, N585S | 8.6e11 |

| AAV4.19 | K479N, L501F, A569P | 4.2e11 |

| AAV4.20 | T446A, S584G | 7.1e11 |

| AAV4.31 | L588Q | 6.6e11 |

| AAV4.38 | T463A, W514L, Q537L, G581C | 2.9e11 |

| AAV4.41 | M523I, G581D, Q583E | 4.3e11 |

| AAV4.49 | R593D | 6.3e11 |

Titers represent average vector genome copies (CBA-Luc) per ml obtained from 2 or 3 vector production runs.

Cell culture.

HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 2.5 μg/ml of amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). CV-1 cells (African green monkey kidney fibroblasts) were propagated in Eagle's minimum essential medium with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 2.5 μg/ml of amphotericin B. Cells were maintained in 5% CO2 at 37°C unless indicated otherwise.

Virus production and titers.

Recombinant AAV4 and related mutants packaging reporter transgenes were generated using the triple plasmid transfection method described earlier (24). Briefly, the plasmids utilized were the AAV4 helper, pXR4 and related Cap mutants, pXX6-80 expressing adenoviral helper genes, and pTR-CBA-Luc containing the chicken beta-actin (CBA) promoter-driven firefly luciferase transgene flanked by AAV inverted terminal repeats derived from the AAV2 genome. Subsequent to viral purification by gradient ultracentrifugation, viral titers were obtained by quantitative PCR using a Roche Lightcycler 480 (Roche Applied Sciences, Pleasanton, CA). Quantitative PCR primers were designed to specifically recognize the luciferase transgene (forward, 5′-AAA AGC ACT CTG ATT GAC AAA TAC-3′, and reverse, 5′-CCT TCG CTT CAA AAA ATG GAA C-3′).

In vitro infectivity assays.

CV-1 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 1e5 cells/well 18 h prior to experimentation. The cells were prechilled at 4°C for 30 min, and then AAV4, AAV4.18, or AAV4.41 packaging the CBA-Luc transgene were incubated on CV-1 cell surface at 4°C for 1 h at 1,000 genome-containing viral particles (VG)/cell, followed by three washes with ice-cold 1× phosphate-buffered saline (1× PBS) to remove unbound virions. To quantitate the number of cell surface-bound virions, 200 μl of double-distilled water (ddH2O) was then added to each well and cells were subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles prior to extraction of total genomic DNA using a DNeasy kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Viral genome titers were then determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) as described above. For cellular-uptake studies following removal of unbound virions, CV-1 cells in freshly added DMEM plus 10% FBS were moved to a 37°C incubator to synchronize virus internalization. After an hour, cells were treated with 150 μl/well of 0.25% trypsin at 37°C for 5 min to release cell surface-associated virions. Trypsin was then quenched by adding 150 μl/well of DMEM with 10% FBS into each well, followed by three washes of the cell pellets with ice-cold PBS. Total genomic DNA was then extracted as described above, and VG copy numbers were determined by qPCR. For transduction assays, CV-1 cells in freshly added DMEM plus 10% FBS were moved to a 37°C incubator and cells lysed at 18 h posttransduction to quantitate luciferase transgene expression using a Victor2 luminometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Animal studies.

All animal experiments were carried out using 6- to 8-week-old female BALB/c mice purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were maintained and treated in accordance with NIH guidelines and as approved by the UNC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). To investigate the effect of sialylated glycans on AAV4 tropism in vivo, BALB/c mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) with either 400 mU/mouse of sialidase (type III, from Vibrio cholerae; Sigma) or 1× PBS at 3 h prior to administration of AAV4-CBA-Luc (1e11 VG/mouse) via the same route (tail vein). To track luciferase transgene expression patterns in mice at specific time points, animals were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane prior to intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of d-luciferin (120 mg/kg of body weight; Nanolight, Pinetop, AZ) and imaged using an Xenogen IVIS Lumina system (PerkinElmer/Caliper Life Sciences, Waltham, MA). Transduction profiles of AAV4 and related mutants were determined in a similar fashion at a dose of 5e10 VG/mouse for each viral strain injected intravenously.

To quantify luciferase expression, the same groups of mice as subjected to live-animal imaging were sacrificed and different tissues harvested for analysis. Tissue lysates were generated by adding 150 μl of 2× passive lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) prior to mechanical lysis using a Tissue Lyser II 352 system (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Tissue lysates were then pelleted to remove debris by centrifugation, and 50 μl of the supernatant from each lysate was subjected to luminometric analysis using a Victor2 luminometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). In addition, 2 μl of supernatant was used for the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) to determine the protein content in each sample.

For viral biodistribution analysis, a second group of BALB/c mice were injected with AAV4 and related mutants under different conditions and animals sacrificed at 3 days postadministration to harvest different organs. Approximately 50 mg of tissue from each organ was pretreated with proteinase K prior to being homogenized using a Tissue Lyser as described above. Total genomic DNA was then extracted from tissue lysates using a DNeasy kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD), and viral genome copy numbers were determined by qPCR. The number of cells in each sample was quantified using qPCR with primers specific to the mLamin housekeeping gene (forward, 5′-GGA CCC AAG GAC TAC CTC AAG GG-3′, and reverse, 5′-AGG GCA CCT CCA TCT CGG AAA C-3′).

For pharmacokinetic analysis, BALB/c mice were first pretreated with intravenous sialidase or PBS as described above. At 3 h postadministration, 1e11 VG copies of AAV4, AAV4.18, or AAV4.41-CBA-Luc were injected through the tail vein. Ten-microliter aliquots of whole blood were then collected by nicking the tail vein at the following time points postinjection: 5, 15, and 30 min and 1, 3, 6, 24, 48, and 72 h. Total DNA was then extracted from each blood sample using a DNeasy kit, and viral genome copy numbers were measured by qPCR.

HA assays.

BALB/c mice were anesthetized using 1.25% tribromoethanol (Avertin) i.p. prior to blood draws by cardiac puncture. Whole blood was mixed with two volumes of Alsever's solution (2.05% [wt/vol] glucose, 0.8% sodium citrate, 0.055% citric acid, 0.42% sodium chloride [pH 6.1]) to prevent coagulation. Erythrocytes were collected from whole blood by centrifugation at 2,500 × g for 5 min, washed three times in 1× PBS, and diluted 10-fold in Alsever's medium. Hemagglutination (HA) assays were carried out in V-bottomed 96-well clear plates in a cold room (maintained at 4°C). Briefly, AAV4, AAV4.18, or AAV4.41-CBA-Luc (1e11 VG each) were serially diluted in 2-fold increments with 1× PBS. A total of 50 μl of 10% murine erythrocytes was then added into each well and incubated with viral particles for 1 h. Hemagglutination titers are expressed as the lowest viable dilutions of virus stocks.

RESULTS

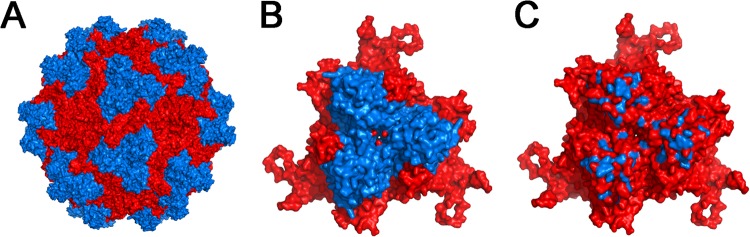

Construction of the randomized AAV4 capsid library.

The 3-fold symmetry axes on AAV capsids have been associated with glycan receptor recognition in the cases of AAV2, AAV3b, AAV6, and AAV9 (25–31). The surface protrusions and spikes surrounding the 3-fold axes are predominantly composed of the highly dynamic GH loop connecting the βG and βH strands within the capsid protein subunit (10, 11). We have previously utilized this approach to dissect key residues that determine AAV9 tropism (21). To identify whether key residues within the GH loop of the AAV4 VP3 subunit were identified in sialic acid recognition, we generated a library of AAV4 variants by introducing random mutations within this loop region. After triaging of nonviable mutant AAV4 Cap gene constructs (containing stop codons, deletions, or frameshift mutations), 48 clones were arbitrarily chosen for further structural modeling and comparative analysis with the original AAV4 capsid template. Subsequently, several AAV4 mutants were selected on the basis of the predominance of mutations at surface-exposed sites for further characterization (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The mutations represented by this collection of AAV4 variants are clustered around the surface of the capsid region surrounding the 3-fold symmetry axes (highlighted in blue in Fig. 1). Variation in vector genome titers for different mutants was found to be within 3-fold or less compared to that of parental AAV4 vectors, indicating that the different mutations within this subset did not affect capsid stability or genome packaging efficiency (Table 1). A detailed characterization of two loss-of-function mutants, AAV4.18 (K492E, K503E, and N585S) and AAV4.41 (M523I, G581D, and Q583E), is described herein.

Fig 1.

Three-dimensional models of the AAV4 capsid library and capsid subunit trimers. Three-dimensional structural models of an intact AAV4 capsid in red (A) with the capsid subunit trimer/3-fold symmetry axis region comprised of the loop regions connecting G and H beta-strands (VP1 numbering, 428 to 617) highlighted in blue (B) are shown. (C) A collection of AAV4 mutations represented within the randomized capsid library with surface-exposed residues highlighted in blue on the AAV4 trimer. Specific residues and point mutations are listed in Table 1. Structural models were visualized and generated using PyMOL.

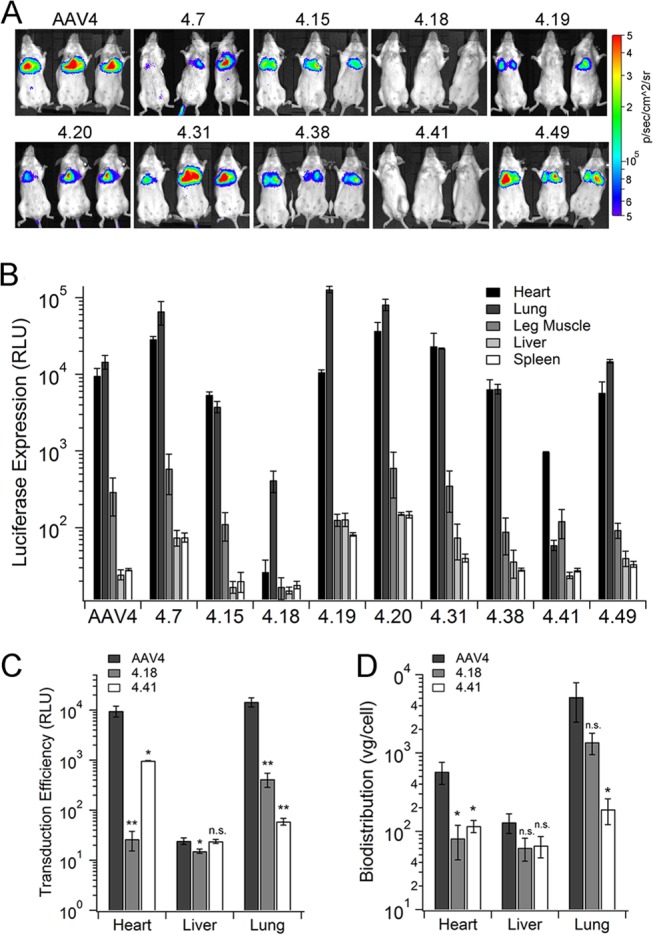

Mutant AAV4 strains are transduction-deficient in mice following systemic administration.

Intravenous (i.v.) administration of AAV4 vectors in mice results in selective cardiopulmonary transgene expression (8). Screening of different mutant AAV4 strains following i.v. injection in mice was carried out by bioluminescent imaging and monitoring of luciferase transgene expression (Fig. 2A and B). At 1 month postadministration (Fig. 2A), AAV4 mutants display two types of tissue transduction profiles in comparison with that of the parental AAV4. While the majority of the mutants demonstrate transduction efficiency similar to that of AAV4, both AAV4.18 and AAV4.41 exhibit decreased luciferase activity in the upper thoracic region. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 2C, in the case of AAV4.18, cardiac transduction decreased by more than 2 orders of magnitude, while transgene expression levels in the lung were decreased by >1 log unit compared to those of AAV4. In case of AAV4.41, a more dramatic loss in transduction efficiency was observed in lung tissue (>2 log units) compared to cardiac tissue (∼1 log unit). These results were further corroborated by decreased accumulation of mutant virions in cardiac and lung tissue compared to that of AAV4 particles (Fig. 2D). Specifically, AAV4.18 and AAV4.41 displayed ∼5- to 10-fold decreases in viral genome copy numbers in these tissues, consistent with decreased cardiopulmonary transduction observed earlier. The transduction efficiency and sequestration of mutant AAV4 strains within the liver remained largely unaffected.

Fig 2.

Transduction profiles of AAV4 mutants in vivo. (A) Parental AAV4 and different AAV4 mutants packaging the CBA-Luc transgene were injected intravenously into BALB/c mice (5e10 VG/mouse). At 1 month postinjection, live-animal bioluminescent images were obtained using a Xenogen IVIS Lumina system (n = 3). Scales represents relative light units (RLU) as photons per second per cm2 per steradian. (B) Mice were sacrificed at 1 month postadministration to harvest different organs, and luciferase expression in different tissues was quantified using a Victor 2 bioluminescence plate reader. Data (RLU) are shown as means ± SEMs (n = 4). (C) Detailed analysis of luciferase transgene expression of AAV4, AAV4.18, and AAV4.41 in mice at 1 month postadministration. (D) Vector genome biodistribution of AAV4, AAV4.18, and AAV4.41 in BALB/c mice at 3 days postadministration. Viral genome copy numbers were obtained using qPCR and normalized to mouse lamin genes (host genomic DNA) copy numbers. Data are plotted as means ± SEMs (n = 4). Statistical significance was analyzed using the one-tailed Student t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant).

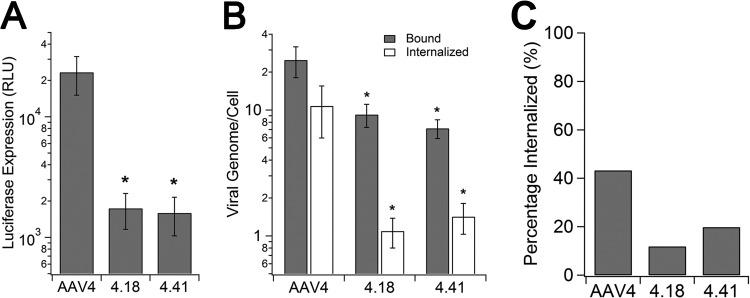

Mutants AAV4.18 and AAV4.41 are deficient in cell surface binding and uptake in vitro.

Consistent with the in vivo characterization, AAV4.18 and AAV4.41 also showed a transduction-deficient phenotype in African green monkey kidney fibroblasts (CV-1). As seen in Fig. 3A, luciferase transgene expression levels mediated by the two mutants are >1 log unit lower than that of parental AAV4 in CV-1 cells. Viral binding and internalization assays revealed that both AAV4.18 and AAV4.41 display 25 to 50% lower binding on CV-1 cells (Fig. 3B, gray bars). Further, cellular uptake of the two mutant strains appears to be significantly impaired (∼10-fold lower) compared to that of AAV4 (Fig. 3B, white bars). While nearly 40% of surface-bound AAV4 particles appear to be internalized after 1 h of incubation, only 10 to 20% of mutant virions are internalized (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results suggest that the transduction-deficient phenotype displayed by mutants AAV4.18 and AAV4.41 is likely due to decreased cell surface binding as well as defective uptake in vitro. In corroboration with in vivo analysis, this decreased cell surface binding further results in loss of function in transducing the cardiopulmonary system in animals.

Fig 3.

Infectivity, binding, and internalization assays of AAV4, AAV4.18, and AAV4.41 on CV-1 cells. (A) Infectivity of AAV4, AAV4.18, and AAV4.41 on CV-1 cells. AAV4, AAV4.18, and AAV4.41-CBA-Luc (MOI = 1,000 VG/cell) were incubated on prechilled CV-1 cells for 1 h prior to three washes with 1× PBS to remove unbound viral particles. Cells were lysed 18 h postinfection to quantify luciferase transgene expression using a bioluminescence plate reader. Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 4). (B) Binding (gray bars) and internalization (white bars) of AAV4, AAV4.18, and AAV4.41 on CV-1 cells. Cells were infected as described above and lysed after the wash step to quantify numbers of bound virions using qPCR or moved to a 37°C incubator to allow cellular uptake. At 1 h after incubation at 37°C, surface-bound virions were removed by trypsin and trypsin-resistant viral particles associated with CV-1 cells were quantified using qPCR. Data are shown as means ± SEMs (n = 4). (C) Percentage of internalization of AAV4, AAV4.18, and AAV4.41. The amount of internalized virions was normalized to the amount of bound virions for AAV4 and mutants to quantify their internalization efficiency in CV-1 cells. Statistical significance was analyzed using the one-tailed Student t test (*, P < 0.05).

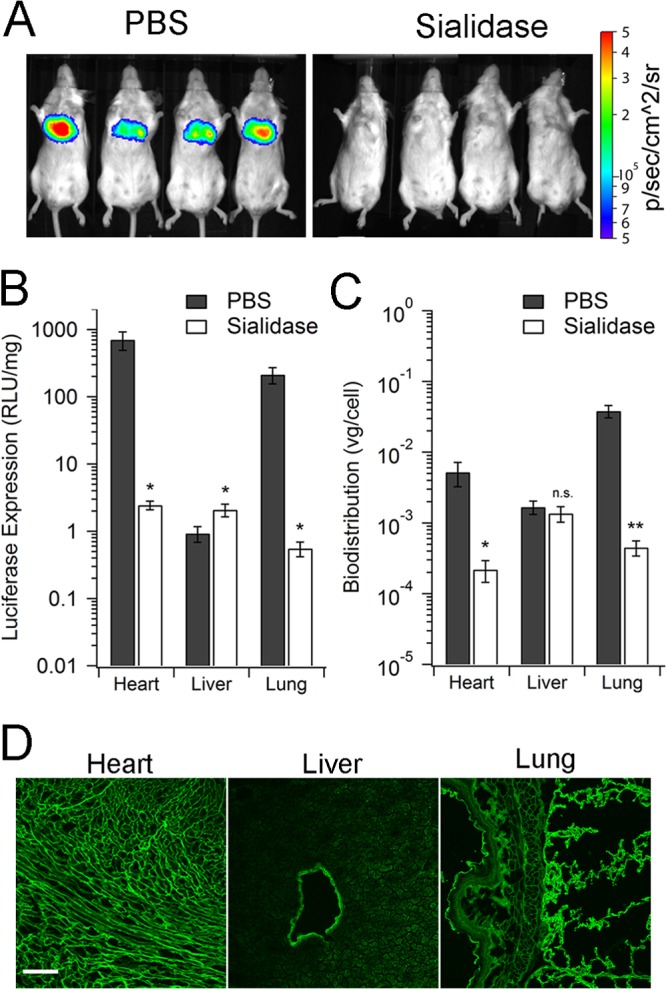

Intravenous sialidase treatment abrogates cardiopulmonary transduction by AAV4.

A critical issue that follows the transduction-defective phenotype of AAV4.18 and AAV4.41 mutants described above is whether this phenotype can be attributed to deficient sialoglycan interactions in vivo. In order to address this question, we preadministered recombinant sialidase intravenously to remove surface-exposed sialic acid moieties from major organs. Our laboratory has demonstrated previously that exposure of terminal galactose in different tissues is significantly increased upon such enzymatic removal of sialic acids (32). As seen in Fig. 4A, the characteristic bioluminescent signal observed due to AAV4-mediated luciferase transgene expression in the upper thoracic region is markedly decreased in sialidase-pretreated mice. This observation was corroborated by quantitation of luciferase expression in the heart and lung, which show nearly 300- to 600-fold-lower transgene expression levels in the sialidase-treated group versus the PBS-treated control (Fig. 4B). Transgene expression within the liver is marginally increased upon enzymatic removal of sialic acid. Quantitative analysis of viral genome copy numbers in heart, lung, and liver revealed a biodistribution profile consistent with transduction. Specifically, an approximately 250- to 400-fold decrease in viral genome copy number within cardiac and pulmonary tissues is observed in sialidase-treated mice, while no significant changes were noted in hepatic tissue (Fig. 4C). These results revealed a functional role for sialic acids in determining AAV4 transduction in vivo and further help clarify the defective phenotype displayed by AAV4 mutants.

Fig 4.

Cardiopulmonary tropism of AAV4 is dependent on sialic acid expression. (A) Live-animal images of AAV4-mediated luciferase transgene expression in BALB/c mice. Mice (n = 4) were injected with PBS or sialidase from Vibrio cholerae (400 mU/mouse) through the tail vein 3 h prior to AAV4-CBA-Luc (1e11 VG/mouse) injection via the same route. At 7 days postinfection, live-animal bioluminescence images were recorded with a Xenogen IVIS Lumina imaging system. Scale indicates relative light units (RLU) as photons per s per cm2 per steradian. (B) Luciferase transgene expression in tissue lysates at 7 days postadministration. At 3 h prior to AAV4-CBA-Luc injection, PBS or sialidase was injected intravenously into BALB/c mice (n = 4). At 7 days postinfection, different organs were harvested. Luciferase transgene expression in each tissue lysate was measured using a bioluminescence plate reader. Values are expressed in RLU normalized to amount of protein in each lysate sample. Data are shown as means ± SEMs (n = 4). (C) Biodistribution of AAV4 viral genomes in BALB/c mice. Vector and host genomic DNA in tissue lysates was isolated and subjected to quantitative PCR analysis, as described in Materials and Methods. Viral genome copies were normalized to copy numbers of the mouse lamin gene. Data are shown as means ± SEMs (n = 4). Statistical significance was analyzed using the one-tailed Student t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant). (D) Lung, heart, and liver tissues harvested from BALB/c mice were stained with FITC-jacalin, a lectin specific to O-linked polysaccharides. Confocal micrographs were obtained using a Zeiss 710 confocal laser scanning microscope with a 20× objective at zoom 0.6. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Cardiopulmonary tropism of AAV4 correlates with tissue expression of O-linked sialoglycans.

To specifically establish the role of O-linked sialic acids in determining the unique cardiopulmonary tropism displayed by AAV4, we carried out lectin immunostaining to determine expression of O-linked sialic acids within the murine heart, lung, and liver. Briefly, sections of heart, lung, and liver from mice underwent immunostaining using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled jacalin, a lectin isolated from jackfruit (Artocarpus integrifolia) (33) that specifically recognizes O-linked oligosaccharides, i.e., mucins. As shown in Fig. 4D, FITC-jacalin shows a markedly higher staining in the ciliated mouse airway epithelial lining and alveoli. Robust staining is also observed in cross sections of the murine heart. In contrast, robust FITC-jacalin is noted primarily in the endothelial wall lining blood vessels within hepatic tissue. Taken together with the transduction and biodistribution profile of blood-borne AAV4, these data strongly support a critical role for O-linked sialic acids in determining the selective cardiopulmonary tropism of AAV4.

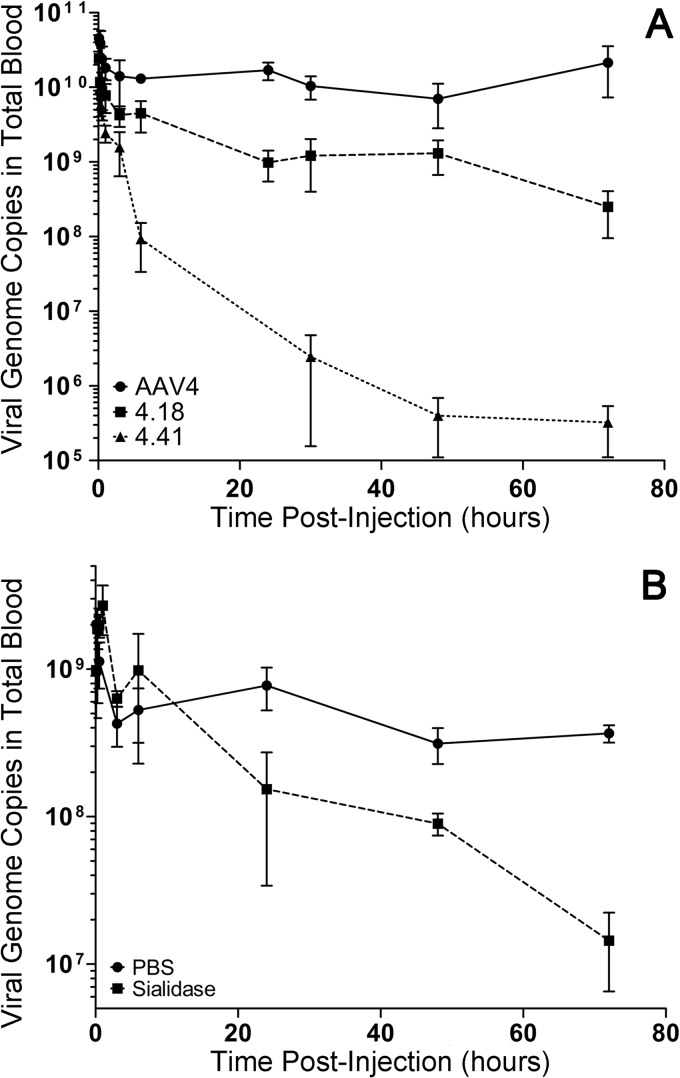

Mutant AAV4 virions and sialidase pretreatment are subject to faster blood clearance in mice.

To understand the impact of AAV4-sialic acid interactions on pharmacokinetics, we first quantitated the number of circulating mutant and parental AAV4 strains following a single intravenous bolus injection using quantitative PCR. As shown in Fig. 5A, over a 72-h period, we observed striking differences in the blood circulation profiles of parental and mutant AAV4 virions. Both AAV4.18 and AAV4.41 mutants were adversely affected and displayed rapid elimination from the blood as early as 6 h postadministration. Further, we recovered low blood levels of the AAV4.18 and AAV4.41 mutants at 24, 48, and 72 h postinjection. The AAV4.41 mutant was more profoundly deficient and displayed accelerated blood clearance compared to the AAV4.18 mutant. In contrast, the parental AAV4 strain appears to persist longer in the blood circulation, with detectable genomes over a 72-h period. The defective phenotype of AAV4 mutants was further corroborated by intravenous pretreatment with recombinant sialidase, which accelerated the clearance of parental AAV4 particles between the 24- and 72-h intervals (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these results support the notion that interactions between the AAV4 capsid and sialoglycans influence not only cellular uptake, tissue tropism, and transduction efficiency but also the prolonged blood residence time of systemically administered viral particles.

Fig 5.

Sialic acid determines the blood circulation profile of AAV4. (A) Parental AAV4 and mutants AAV4.18 and AAV4.41 (1e11 VG/mouse) were administered into BALB/c mice via intravenous injections. Approximately 10 μl of blood was collected through tail vein nicks at following times postinjection: 5 min, 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h. Viral genome copy numbers in each blood sample were quantified using qPCR with primers against the luciferase transgene. Data are shown as means ± SEMs (n = 4). (B) Kinetics of AAV4 clearance from blood was determined over 72 h postadministration with or without sialidase pretreatment. At 3 h prior to AAV4 vector administration, recombinant sialidase from Vibrio cholerae (400 mU/mouse) or PBS (control) was intravenously injected into BALB/c mice (n = 4). Approximately 10 μl of blood was collected from tail vein nicks at intervals similar to those for panel A. Viral genome copies in blood samples were quantified using qPCR, and data are shown as means ± SEMs (n = 4).

Mutant AAV4 virions are deficient in hemagglutination.

Lastly, we carried out hemagglutination assays with mutant and parental strains to determine whether direct AAV4 capsid-erythrocyte interactions might influence blood clearance rates. Consistent with earlier observations (6), AAV4 has a high HA titer (>128), indicating a high binding affinity toward sialoglycans on the surface of murine erythrocytes. However, as shown in Table 2, both AAV4.18 and AAV4.41 display low HA titers (>4) similar to those of PBS and AAV2 vectors, which were included as controls and do not hemagglutinate murine erythrocytes. These results confirm the notion that the AAV4 mutants described in this report are defective in sialoglycan interactions.

Table 2.

Hemagglutination of murine erythrocytes by different AAV strains

| Virus | Hemagglutination titer |

|---|---|

| None (PBS) | <2 |

| AAV2 | <2 |

| AAV4 | <128 |

| AAV4.18 | <4 |

| AAV4.41 | <4 |

DISCUSSION

Sialylated glycans function as cellular attachment receptors for several viruses, including influenza virus, rotaviruses, coxsackieviruses, etc. (34, 35). For instance, pathogenic respiratory viruses, such as influenza viruses and rhinoviruses, recognize specialized forms of sialic acids on upper airway epithelial cells to infect their corresponding hosts (36, 37). Hepatitis B, C, and E viruses employ heparan sulfates, which are abundant on hepatocytes, to infect human liver (38–40). In the Dependovirus genus of the Parvoviridae family, AAV4 is the only serotype known thus far to bind O-linked sialic acids. Previous studies have demonstrated that apical transduction of well-differentiated human airway epithelial cells by AAV4 is effectively inhibited by secreted mucins and O-linked sialoglycans (7). In contrast, AAV4 efficiently transduces airway epithelia from the basolateral side in a sialic acid-dependent fashion. Given these strong interactions with mucins in vitro and the selective cardiopulmonary tropism of systemically administered AAV4 in vivo (8), we explored the role of O-linked sialoglycans in determining the tissue tropism of this divergent serotype.

First, we successfully demonstrated the applicability of a previously established, random library approach developed in our laboratory (21) to discover new loss-of-function AAV4 mutants that are presumably defective in sialic acid recognition. For instance, key basic residues (R484, R487, K532, R585, and R588) involved in heparan sulfate recognition have now been located on 3-fold protrusions of the AAV2 capsid (25, 27, 29, 41). Similarly, heparan sulfate recognition by AAV3B and AAV6 capsids is now well established (26, 28, 31). In the case of AAV9, the residues D271, N272, N470, Y446, and W503 are required for Gal binding (30). Unlike heparan sulfate or galactose, the binding site(s) or key residues involved in sialic acid recognition are yet to be identified for the corresponding AAV strains. Our results support the notion that several amino acids (K492, K503, M523, G581, Q583, and N585) located on the surfaces of AAV4.18 and AAV4.41 mutant capsids might represent a subset of key residues that might directly or indirectly influence sialic acid recognition by AAV4 capsids. It is interesting that two of these residues, K492 and K503, lie within the hypervariable region (HVR) IV, while three others, G581, Q583, and N585, lie within HVR VIII. Both of these surface loops have been implicated in the formation of the 3-fold peaks on the AAV capsid and contain key amino acids implicated in glycan binding for other serotypes (4). As mentioned earlier, W503 in HVR IV is a key residue in the Gal binding pocket of the AAV9 capsid, while R585 and R588 in HVR VIII have been implicated in heparan sulfate binding by AAV2 capsids. While the exact structural contribution of these residues remains to be determined, these loss-of-function mutants confirm that the sialic acid binding footprint on AAV4 capsids likely lies within the surface loops surrounding the 3-fold symmetry axes. Although the current study highlights a critical role for the above-listed residues in cell surface binding and uptake, it should be noted that these residues might also influence other postentry steps, such as capsid uncoating. However, these aspects of the AAV4 infectious pathway were outside the scope of the current study.

A key observation is that sialic acids not only are involved in cell surface attachment but also are essential for cellular uptake of AAV4 capsids in CV-1 cells in vitro. This scenario is unique and does not appear to be the case for other AAV serotypes that recognize N-linked sialic acid. For instance, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) have been identified as coreceptors for AAV5 and AAV6, respectively (42, 43). However, a putative coreceptor involved in the cellular uptake of AAV4 has yet to be determined. It is also interesting that the conserved integrin binding motif (NGR) reported for several AAV serotypes is mutated (DGR) on AAV4 capsids (44). In light of these observations, it is tempting to speculate that O-sialylated glycans might be directly involved in the cellular uptake of AAV4 particles, unlike for other AAV serotypes.

We disrupted AAV4-sialic acid interactions in vivo using two complementary strategies, i.e., loss-of-function mutants and intravenous sialidase pretreatment of mice. Both strategies profoundly impact AAV4 tropism by abrogating the native cardiopulmonary transduction profile observed in mice following systemic administration. Further, we observed marked changes in the pharmacokinetic profile under these conditions. Based on these results, we propose a sequential interaction between systemically administered AAV4 particles with circulating erythrocytes followed by the cardiopulmonary system, both of which abundantly express O-sialoglycans. A similar paradigm has been postulated for adenoviruses recognizing sialic acids and the cell adhesion molecule CAR on erythrocytes (45). Specifically, in the study reported in reference 45, adenoviral binding to CAR on erythrocytes was demonstrated to prolong the circulation half-life and reduce liver tropism. Further, our laboratory and others have recently demonstrated that the systemic tropism displayed by AAV9 is associated with prolonged blood circulation and glycan binding avidity (32, 46).

Our study raises several important questions pertinent to dissecting the cellular, tissue-selective, and host-specific tropism(s) of AAV serotype 4. For instance, a disproportionate decrease in viral genome copy number was observed for AAV4.18 in cardiac tissue compared to that for wild-type AAV4 (Fig. 2C and D). This is an interesting observation, since in vitro data suggest that deficiencies in binding and cellular uptake sufficiently explain the transduction defect for this mutant. One possible explanation is that AAV4 particles associated with serum proteins are bound, internalized, or cleared from the circulation by vascular endothelium through nonspecific uptake pathways that do not result in productive transduction. Another possible explanation is the likelihood that the kinetics of binding and tissue uptake in vivo differ from those observed in vitro. It is likely that a time course study of viral genome accumulation in different organs might yield a better correlation between vector genome copy number and transduction efficiency in different organs. Lastly, it is also likely that the capsid mutations could affect postentry trafficking events such as capsid uncoating.

Another intriguing question is whether the loss-of-function mutations reported in the current study alter the cellular tropism of AAV4 within peripheral tissues lacking erythrocytes, such as the eye and the brain. Another critical question is whether the host-specific tropism of recombinant AAV4 vectors is likely to vary with O-linked sialylation patterns observed in different species. In this regard, screening of AAV vectors in multiple preclinical animal models and mapping the glycosylation patterns of different host tissues might be critical to interpreting or predicting clinical outcomes. In summary, our study provides new insights into the biology of AAV serotype 4. The results described are likely to help us better understand virus-glycan interactions in general as well as guide the selection of appropriate preclinical models for studying virus-host interactions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NIH grants awarded to A.A. (R01HL089221 and P01HL112761).

S.S. and A.A. designed the overall study and wrote the manuscript. S.S. and N.P. carried out cloning, vector production, and in vitro studies. S.S. and A.N.T. conducted systemic studies with mice.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 September 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Berns K, Parrish CR. 2007. Parvoviridae, p 2437–2477 In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE. (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed, vol II Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asokan A, Schaffer DV, Jude Samulski R. 2012. The AAV vector toolkit: poised at the clinical crossroads. Mol. Ther. 20:699–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiorini JA, Yang L, Liu Y, Safer B, Kotin RM. 1997. Cloning of adeno-associated virus type 4 (AAV4) and generation of recombinant AAV4 particles. J. Virol. 71:6823–6833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Govindasamy L, Padron E, McKenna R, Muzyczka N, Kaludov N, Chiorini JA, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2006. Structurally mapping the diverse phenotype of adeno-associated virus serotype 4. J. Virol. 80:11556–11570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padron E, Bowman V, Kaludov N, Govindasamy L, Levy H, Nick P, McKenna R, Muzyczka N, Chiorini JA, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2005. Structure of adeno-associated virus type 4. J. Virol. 79:5047–5058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaludov N, Brown KE, Walters RW, Zabner J, Chiorini JA. 2001. Adeno-associated virus serotype 4 (AAV4) and AAV5 both require sialic acid binding for hemagglutination and efficient transduction but differ in sialic acid linkage specificity. J. Virol. 75:6884–6893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walters RW, Pilewski JM, Chiorini JA, Zabner J. 2002. Secreted and transmembrane mucins inhibit gene transfer with AAV4 more efficiently than AAV5. J. Biol. Chem. 277:23709–23713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zincarelli C, Soltys S, Rengo G, Rabinowitz JE. 2008. Analysis of AAV serotypes 1–9 mediated gene expression and tropism in mice after systemic injection. Mol. Ther. 16:1073–1080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davidson BL, Stein CS, Heth JA, Martins I, Kotin RM, Derksen TA, Zabner J, Ghodsi A, Chiorini JA. 2000. Recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2, 4, and 5 vectors: transduction of variant cell types and regions in the mammalian central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:3428–3432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agbandje-McKenna M, Kleinschmidt J. 2011. AAV capsid structure and cell interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 807:47–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapman MS, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2006. Atomic structure of viral particles, p 107–123 In Kerr JR, Cotmore SF, Bloom ME, Linden RM, Parrish CR. (ed), Parvoviruses. Edward Arnold Ltd, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 12.Summerford C, Samulski RJ. 1998. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J. Virol. 72:1438–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Handa A, Muramatsu S, Qiu J, Mizukami H, Brown KE. 2000. Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-3-based vectors transduce haematopoietic cells not susceptible to transduction with AAV-2-based vectors. J. Gen. Virol. 81:2077–2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabinowitz JE, Rolling F, Li C, Conrath H, Xiao W, Xiao X, Samulski RJ. 2002. Cross-packaging of a single adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 vector genome into multiple AAV serotypes enables transduction with broad specificity. J. Virol. 76:791–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halbert CL, Allen JM, Miller AD. 2001. Adeno-associated virus type 6 (AAV6) vectors mediate efficient transduction of airway epithelial cells in mouse lungs compared to that of AAV2 vectors. J. Virol. 75:6615–6624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Z, Asokan A, Grieger JC, Govindasamy L, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. 2006. Single amino acid changes can influence titer, heparin binding, and tissue tropism in different adeno-associated virus serotypes. J. Virol. 80:11393–11397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen S, Bryant KD, Brown SM, Randell SH, Asokan A. 2011. Terminal N-linked galactose is the primary receptor for adeno-associated virus 9. J. Biol. Chem. 286:13532–13540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell CL, Vandenberghe LH, Bell P, Limberis MP, Gao GP, Van Vliet K, Agbandje-McKenna M, Wilson JM. 2011. The AAV9 receptor and its modification to improve in vivo lung gene transfer in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121:2427–2435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Z, Miller E, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. 2006. Alpha2,3 and alpha2,6 N-linked sialic acids facilitate efficient binding and transduction by adeno-associated virus types 1 and 6. J. Virol. 80:9093–9103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walters RW, Yi SM, Keshavjee S, Brown KE, Welsh MJ, Chiorini JA, Zabner J. 2001. Binding of adeno-associated virus type 5 to 2,3-linked sialic acid is required for gene transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20610–20616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pulicherla N, Shen S, Yadav S, Debbink K, Govindasamy L, Agbandje-McKenna M, Asokan A. 2011. Engineering liver-detargeted AAV9 vectors for cardiac and musculoskeletal gene transfer. Mol. Ther. 19:1070–1078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. 2006. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22:195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrillo-Tripp M, Shepherd CM, Borelli IA, Venkataraman S, Lander G, Natarajan P, Johnson JE, Brooks CL, III, Reddy VS. 2009. VIPERdb2: an enhanced and web API enabled relational database for structural virology. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D436–D442. 10.1093/nar/gkn840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grieger JC, Choi VW, Samulski RJ. 2006. Production and characterization of adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat. Protoc. 1:1412–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Opie SR, Warrington KH, Jr, Agbandje-McKenna M, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N. 2003. Identification of amino acid residues in the capsid proteins of adeno-associated virus type 2 that contribute to heparan sulfate proteoglycan binding. J. Virol. 77:6995–7006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng R, Govindasamy L, Gurda BL, McKenna R, Kozyreva OG, Samulski RJ, Parent KN, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2010. Structural characterization of the dual glycan binding adeno-associated virus serotype 6. J. Virol. 84:12945–12957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Donnell J, Taylor KA, Chapman MS. 2009. Adeno-associated virus-2 and its primary cellular receptor—cryo-EM structure of a heparin complex. Virology 385:434–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lerch TF, Chapman MS. 2012. Identification of the heparin binding site on adeno-associated virus serotype 3B (AAV-3B). Virology 423:6–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy HC, Bowman VD, Govindasamy L, McKenna R, Nash K, Warrington K, Chen W, Muzyczka N, Yan X, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M. 2009. Heparin binding induces conformational changes in adeno-associated virus serotype 2. J. Struct. Biol. 165:146–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bell CL, Gurda BL, Van Vliet K, Agbandje-McKenna M, Wilson JM. 2012. Identification of the galactose binding domain of the AAV9 capsid. J. Virol. 86:7326–7333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie Q, Lerch TF, Meyer NL, Chapman MS. 2011. Structure-function analysis of receptor-binding in adeno-associated virus serotype 6 (AAV-6). Virology 420:10–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen S, Bryant K, Sun J, Brown S, Troupes A, Pulicherla N, Asokan A. 2012. Glycan binding avidity determines the systemic fate of adeno-associated virus 9. J. Virol. 86:10408–10417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bunn-Moreno MM, Campos-Neto A. 1981. Lectin(s) extracted from seeds of Artocarpus integrifolia (jackfruit): potent and selective stimulator(s) of distinct human T and B cell functions. J. Immunol. 127:427–429 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olofsson S, Bergstrom T. 2005. Glycoconjugate glycans as viral receptors. Ann. Med. 37:154–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neu U, Bauer J, Stehle T. 2011. Viruses and sialic acids: rules of engagement. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 21:610–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chandrasekaran A, Srinivasan A, Raman R, Viswanathan K, Raguram S, Tumpey TM, Sasisekharan V, Sasisekharan R. 2008. Glycan topology determines human adaptation of avian H5N1 virus hemagglutinin. Nat. Biotechnol. 26:107–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomassini JE, Maxson TR, Colonno RJ. 1989. Biochemical characterization of a glycoprotein required for rhinovirus attachment. J. Biol. Chem. 264:1656–1662 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang J, Cun W, Wu X, Shi Q, Tang H, Luo G. 2012. Hepatitis C virus attachment mediated by apolipoprotein E binding to cell surface heparan sulfate. J. Virol. 86:7256–7267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalia M, Chandra V, Rahman SA, Sehgal D, Jameel S. 2009. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans are required for cellular binding of the hepatitis E virus ORF2 capsid protein and for viral infection. J. Virol. 83:12714–12724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vanlandschoot P, Van Houtte F, Serruys B, Leroux-Roels G. 2005. The arginine-rich carboxy-terminal domain of the hepatitis B virus core protein mediates attachment of nucleocapsids to cell-surface-expressed heparan sulfate. J. Gen. Virol. 86:75–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kern A, Schmidt K, Leder C, Muller OJ, Wobus CE, Bettinger K, Von der Lieth CW, King JA, Kleinschmidt JA. 2003. Identification of a heparin-binding motif on adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids. J. Virol. 77:11072–11081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Di Pasquale G, Davidson BL, Stein CS, Martins I, Scudiero D, Monks A, Chiorini JA. 2003. Identification of PDGFR as a receptor for AAV-5 transduction. Nat. Med. 9:1306–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weller ML, Amornphimoltham P, Schmidt M, Wilson PA, Gutkind JS, Chiorini JA. 2010. Epidermal growth factor receptor is a co-receptor for adeno-associated virus serotype 6. Nat. Med. 16:662–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asokan A, Hamra JB, Govindasamy L, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. 2006. Adeno-associated virus type 2 contains an integrin alpha5beta1 binding domain essential for viral cell entry. J. Virol. 80:8961–8969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seiradake E, Henaff D, Wodrich H, Billet O, Perreau M, Hippert C, Mennechet F, Schoehn G, Lortat-Jacob H, Dreja H, Ibanes S, Kalatzis V, Wang JP, Finberg RW, Cusack S, Kremer EJ. 2009. The cell adhesion molecule “CAR” and sialic acid on human erythrocytes influence adenovirus in vivo biodistribution. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000277. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kotchey NM, Adachi K, Zahid M, Inagaki K, Charan R, Parker RS, Nakai H. 2011. A potential role of distinctively delayed blood clearance of recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 9 in robust cardiac transduction. Mol. Ther. 19:1079–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]