Leptin is an adipocyte-derived circulating hormone that provides information to the brain about energy stores (1). The brain’s response to leptin involves changes in energy expenditure and food intake. Leptin-deficient mammals, including humans, are markedly hyperphagic, and leptin replacement reverses this. However, there is little information about how higher brain centers integrate homeostatic signals such as leptin with the rewarding properties of food. We studied a 14-year-old boy (subject 1) and a 19-year-old girl (subject 2) with the very rare condition of congenital leptin deficiency, before and after 7 days of treatment with recombinant human leptin (2). Although no changes in body weight were seen over this time, leptin treatment had a major effect on food intake. Ad libitum energy intake at a test meal was reduced from 152 to 64 kJ/kg of lean mass and from 169 to 98 kJ/kg of lean mass in subjects 1 and 2, respectively [normal ad libitum intake was 54 ± 12 kJ/kg of lean mass (± SD) in age-related controls (3)]. We used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure differential brain activation by visual images of food compared with images of nonfood in the leptin-deficient and leptin-treated states. We used 10-cm visual analog scores to rate hunger, satiety, and the “liking” of food images (2). To examine the interaction with eating, we studied participants in fasted and fed states (2).

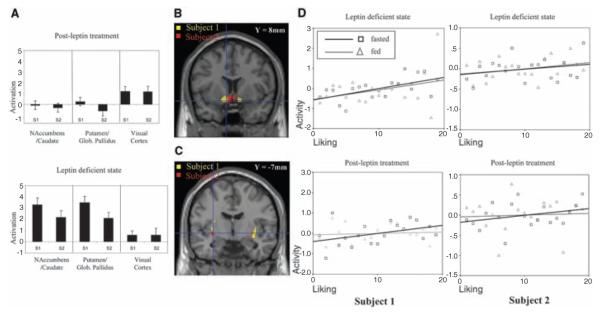

After leptin treatment, hunger ratings in the fasted state decreased, and satiety following a meal increased (2). Whereas visual images of food elicited no differential activation of mesolimbic areas in the leptin-replaced state, the leptin-deficient state was associated with marked activation in the anteromedial ventral striatum (nucleus accumbens and caudate nucleus) and posterolateral ventral striatum (putamen and globus pallidus) (Fig. 1, A to C).

Fig. 1.

Leptin regulates brain responses to food images. (A). Leptin reduces activation in the nucleus accumbens-caudate and putamen–globus pallidus regions in subject 1 (S1) and subject 2 (S2) (linear regression coefficients; mean ± SE). Visual cortex showed no response to leptin. (B) Nucleus accumbens-caudate and (C) putamen–globus pallidus are activated by food stimuli (threshold P < 0.05; corrected for multiple comparisons). (D) A three-way interaction between stimulus (food versus nonfood images), fasted or fed state, and leptin localized to nucleus accumbens-caudate (fig. S1A). Mean corrected activity from this region (y axis) is plotted against the ranked liking for foods. Each block comprised five foods; mean liking ratings for each block were ranked and plotted against nucleus accumbens-caudate activity for that block in the fasted (black) and fed (gray) states, pre- and postleptin. Before leptin treatment, activation in nucleus accumbens-caudate correlated positively with liking in both fasted (P < 0.05) and fed (P < 0.05) states. After leptin treatment, activation correlated with liking ratings only in the fasted state (P < 0.05).

When asked to rate how much they liked each of the food images, leptin-deficient subjects in the fed state gave high ratings to all food images (mean = 8.9 ± 0.5). After leptin, the liking ratings were reduced (mean = 5.9 ± 0.4). These behavioral responses were accompanied by a region-specific change in the evoked neural response after leptin treatment. The ventral striatum (localized to nucleus accumbens-caudate nucleus) was identified as the site of an interaction between stimulus type, fasting state, and leptin (Fig. 1D and fig. S1A).

In the leptin-deficient state, accumbens-caudate activation correlated positively with liking ratings in fasted (P < 0.05) and fed (P < 0.05) states (Fig. 1D). In the leptin-treated state, accumbens-caudate activation correlated positively with liking ratings only in the fasted state (P < 0.05), an effect that was also seen in normal weight controls studied using the same paradigm (fig. S1B).

We have shown that leptin markedly affects neural responses to visual food stimuli. In patients with congenital leptin deficiency, leptin administration results in an increased ability to discriminate between the rewarding properties of food and, at the neuronal level, in the modulation of activation in the ventral striatum. This interaction suggests that leptin modulates feeding-related mesolimbic sensitivity to visual food stimuli. Our findings are consistent with the view that activation in the ventral striatal region does not directly encode the “liking” but rather the motivational salience or “wanting” of food (4). In the leptin-deficient state, images of well-liked foods engender a greater wanting response, even when the subject has just been fed. After leptin treatment, well-liked food images engender this response only in the fasted state, an effect consistent with the response in control subjects. Thus, wanting of food appears to drive the correlation between ventral striatal activation and liking.

Our data support the notion that leptin acts on neural circuits governing food intake to diminish perception of food reward while enhancing the response to satiety signals generated during food consumption. These experiments thus provide functional neuroanatomical insights into the mechanisms by which leptin, the key peripherally derived signal encoding nutritional state, can interact with stimuli related to the visual appearance and the recent ingestion of food to modulate spontaneous eating behavior in humans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Wellcome Trust, the Medical Research Council, and the Woco Foundation. We thank G. Johnson and G. Murray for help with these studies.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1144599/DC1 Materials and Methods, Figs. S1 and S2, References

References and Notes

- 1.Morton GJ, Cummings DE, Baskin DG, Barsh GS, Schwartz MW. Nature. 2006;443:289. doi: 10.1038/nature05026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Materials and methods are available on Science Online.

- 3.Farooqi IS, et al. New Engl. J. Med. 1999;341:879. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909163411204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berridge KC, Robinson TE. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:507. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.