Abstract

We have designed ruthenium-modified Pseudomonas aeruginosa azurins that incorporate 3-nitrotyrosine (NO2YOH) between Ru(2,2′-bipyridine)2(imidazole)(histidine) and Cu redox centers in electron transfer (ET) pathways. We investigated the structures and reactivities of three different systems: RuH107NO2YOH109, RuH124NO2YOH122, and RuH126NO2YOH122. RuH107NO2YOH109, unlabeled H124NO2YOH122, and unlabeled H126NO2YOH122 were structurally characterized. The pKas of NO2YOH at positions 122 and 109 are 7.2 and 6.0, respectively. Reduction potentials of 3-nitrotyrosinate (NO2YO−)-modified azurins were estimated from cyclic and differential pulse voltammetry data: oxidation of NO2YO−122 occurs near 1.1 versus NHE; that for NO2YO−109 is near 1.2 V. Our analysis of transient optical spectroscopic experiments indicates that hopping via NO2YO− enhances CuI oxidation rates over single-step ET by factors of 32 (RuH107NO2YO−109), 46 (RuH126NO2YO−122), and 13 (RuH124NO2YO−122).

1. Introduction

Biological redox transformations rely on efficient electron/hole transport over long molecular distances (>10 Å). Key examples include water oxidation in photosystem II,1 O2 reduction in cytochrome c oxidase,2 deoxynucleoside production in ribonucleotide reductases (RNR),3 H+/H2 interconversion in hydrogenases,4 and N2 reduction in nitrogenases.5 Single-step electron transfer (ET) cannot deliver electron/holes in milliseconds or less to protein active sites over distances exceeding 20 Å, so many enzymes employ redox way stations to promote rapid multistep ET (hopping).6 Understanding and incorporating these natural design elements into artificial redox systems to promote rapid electron/hole separation and long-lived charge separated states is of great interest for use in solar energy capture and conversion.

Our work on ET in Ru-modified metalloproteins, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa azurin,7,8 has been informed by semiclassical ET theory9,10 (Eq 1, ss = single-step tunneling). Note that 1/τss = kss, which is the sum of the forward and reverse rate constants for a single-step

| (1) |

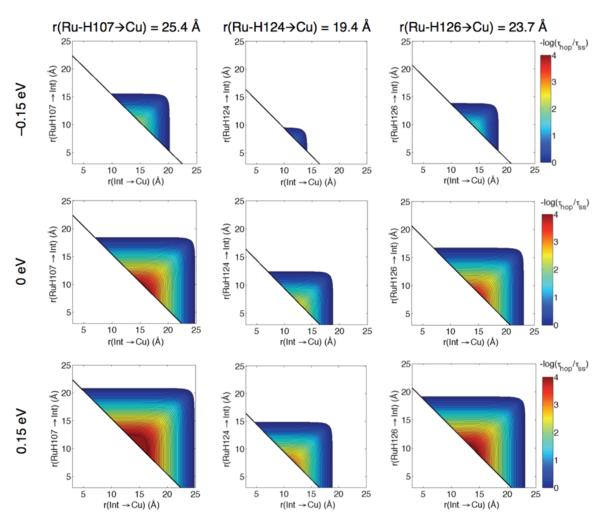

ET reaction. Set out in Figure 1 are modified hopping maps6,11 that show the predicted hopping advantage (with respect to single-step ET) for Ru-H107, Ru-H124, and Ru-H126 azurins with a generalized intermediate (Int) situated between a diimine-RuIII oxidant and CuI. The maps compare the total ET times for hopping from a donor (D) to an intermediate (I) to an acceptor (A) (τhop, Eq. 2, hop = hopping) versus single-step D to A tunneling (τss)12 (Eq. 1). As above, 1/τhop = khop, which is a function of all of the forward and reverse rate constants for ET between D, I, and A.6a

| (2) |

Maps were generated assuming a reorganization energy (λ) of 0.8 eV, an electronic coupling decay constant (β) of 1.1 Å−1, and HAB0 (r0 = 3 Å) of 186 cm−1 for each ET reaction.7 Note that the maps are not symmetric. In all cases, the greatest hopping advantage occurs in systems where the Int-RuIII distance is 0 to 5 Å shorter than the Int-CuI distance. The hopping advantage increases as systems orient nearer a “straight-line” between the donor and acceptor (the black diagonal), which is a result of minimizing intermediate tunneling distances. The smallest predicted hopping advantage area is in Ru-H124 azurin, which has the shortest Ru-Cu distance of the three proteins.

Figure 1.

Hopping advantage maps for a two-step ET system (CuI → Int → RuIII) in each of three azurins. In each map the overall driving force −ΔG°(CuI → RuIII) is 0.7 eV, the reorganization energy (λ) is 0.8 eV, T is 298 K, the distance decay constant (β) is 1.1 Å−1, and the close-contact coupling element (HAB0) is 186 cm−1. khop is the calculated hopping rate constant and kss is the calculated single-step rate constant. The first step driving forces (−ΔG°(Int → RuIII)) are indicated at the left. The contour lines are plotted at 0.1 log unit intervals.

The maps in Figure 1 illustrate how the hopping advantage at a fixed D-A distance changes as a function of driving force (−ΔG°). The hopping advantage is nearly lost as the driving force for the first step (RuIII → Int) falls below −0.15 eV. Isoergic initial steps provide a wide distribution of arrangements, where advantages as great as 104 are possible (for a fixed donor-acceptor distance of 23.7 or 25.4 Å). A slightly exergonic RuIII → Int step provides an even larger distribution of arrangements for productive hopping, which will be the case as long as the driving force for the first step is not more favorable than that for overall transfer.

We have used nitrotyrosinate (NO2YO−) as a redox intermediate in three Ru-His labeled azurins to test the hopping advantage for net CuI → RuIII ET. The phenol pKa of 3-nitrotyrosine is 7.2,13 allowing us to work at near-neutral pH, rather than high pH (>10) required to study analogous reactions in tyrosine. Investigating ET via nitrotyrosinate also avoids the complexities associated with the kinetics of proton-coupled redox reactions of tyrosine.14 The NO2YOH model compound N-acetyl-3-nitrotyrosinamde has pKa similar to that of 3-nitrotyrosine and the NO2•/− reduction potential (E°’ ~ 1.02 V versus NHE) is similar to that15 of Trp•+/0 and Rudiimine photosensitizers.16 It follows that hole transfer via NO2YO− can be described using semiclassical ET theory, because it is not a proton-coupled redox reaction.14,17 We prepared three azurins with NO2YO− situated between the Ru and Cu sites: RuH107NO2YOH109; RuH124NO2YOH122; and RuH126NO2YOH122. The first two systems have cofactor placements that are close to optimal; the last system has a larger first-step distance, which is predicted to decrease the hopping advantage.

Results

2.1 Synthesis and Characterization

Site-directed mutants of P. aeruginosa azurin with surface-exposed Tyr residues were obtained using standard procedures18 and NO2YOH was produced by reaction with tetranitro-methane (TNM).19 Our modified azurin has additional mutations (W48F/Y72F/H83Q/Y108F) such that only a single Tyr residue was available for TNM modification (M109Y or K122Y) and a single His residue for Ru-labeling (Q107H, T124H or T126H). Nitration of YOH was confirmed by mass spectrometry and UV-vis spectroscopy (see Supporting Information). At basic pH, NO2YO− exhibits a visible absorption maximum at 420 nm,19 imparting a vivid green color to CuII proteins. Yields for TNM modification for each protein were ≥ 90% based on UV-vis quantification of protein following FPLC purification. The UV-vis spectra of all three of the NO2YOH- or NO2YO−-azurins were found to be the sum of the component spectra of azurin and free nitrotyrosine or nitrotyrosinate (see Supporting Information), thereby confirming that the NO2YO−, Ru-label, and azurin-Cu are very weakly coupled in the modified protein.

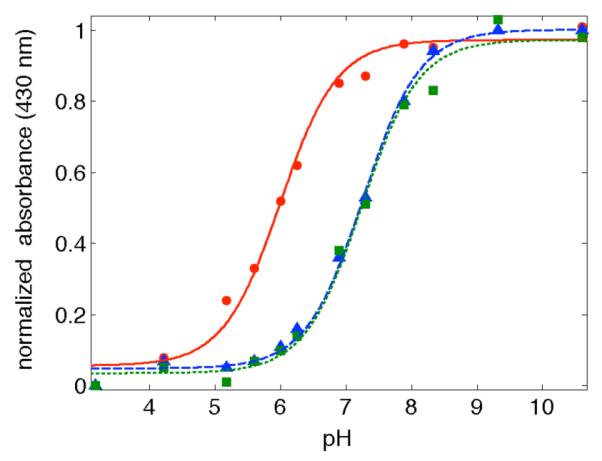

Spectrophotometric titration of CuII-NO2YOH azurins from pH 4 to 10 gave clean conversions to nitrotyrosinate (NO2YO−) (Figure 2). NO2YOH109 has pKa = 6.0 ± 0.05, over 1 pK unit lower than nitrotyrosine models (7.2).13,15 a NO2YOH122 (with His at either position 124 or 126) has pKa =7.2 ± 0.05. These pKas could be slightly shifted in the Ru-labeled proteins, but UV-vis spectra at pH > 8, as used in our time-resolved laser experiments, are consistent with complete conversion to NO2YO− (see Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Titration curves for: H107NO2YOH109 (red ●); H124NO2YOH122 (green ∎) and H126NO2YOH122 (blue ▴). The lines are fits as described in Methods.

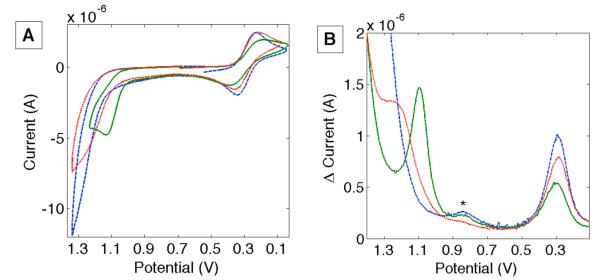

The NO2YO•/− reduction potentials were investigated using cyclic voltammetry (all reduction potentials are referenced to NHE). Measurements were problematic because the NO2YO•/− couple is near the solvent window (20 mV/s scan rate, 50 mM potassium phosphate + 50 mM KCl, pH 8.3, Figure 3). The azurin-CuII/I couple (E°’ = 0.30 ± 0.01 V20) remained constant in all variants, providing a convenient internal standard. NO2YO−122 azurins exhibited an anodic wave at 0.8 V versus the Cu anodic wave (Figure 3A), consistent with E° values for NO2YO− model compounds.15 Unfortunately, an analogous oxidative wave was not observed for NO2YO−109 azurin. A modest increase in anodic current above 1 V compared to “all Phe” azurin (where all Tyr/Trp residues are replaced with Phe) can be seen in the voltammogram of NO2YO−109 azurin.

Figure 3.

A) Cyclic voltammogram (20 mV/s) of H124NO2YO−122 azurin (green  ), H107NO2YO−109 (red •••) and all Phe azurin (blue

), H107NO2YO−109 (red •••) and all Phe azurin (blue  ). (B) Differential pulse voltammograms (DPVs) for H124NO2YO−122 azurin (green

). (B) Differential pulse voltammograms (DPVs) for H124NO2YO−122 azurin (green  ), H107NO2YO−109 (red •••) and all Phe azurin (blue

), H107NO2YO−109 (red •••) and all Phe azurin (blue  ). The asterisk indicates a background wave. Potentials are versus NHE.

). The asterisk indicates a background wave. Potentials are versus NHE.

We turned to differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) in an effort to better resolve the electrochemical response attributed to oxidation of nitrotyrosinate.21 DPVs of 1 mM NO2YOH-modified proteins in 50 mM potassium phosphate + 50 mM KCl exhibited am peak at 1.1 V for NO2YO−122 azurin and a shoulder at ~1.2 V for NO2YO−109 azurin. All Phe azurins exhibited a steeply increasing background signal, but no maxima or inflection points. As for CV experiments, E°’(CuII/I) exhibited a peak at 0.30 ± 0.01 V.

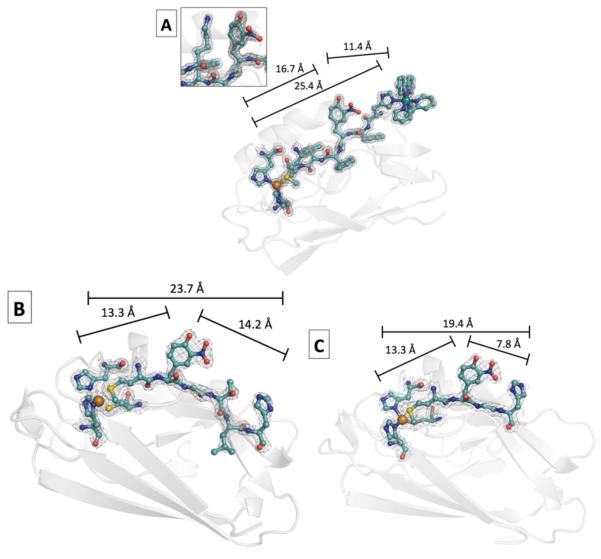

RuII(bpy)2(im) labeling (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine, im = imidazole) and purification of all three azurins were as described previously.8, 22 Successful labeling was confirmed by UV-vis spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. X-ray quality crystals of Ru-H107NO2YOH109-azurin were grown using sitting drop vapor diffusion.23 Crystals of NO2YOH122-azurin (without Ru at H124 or H126) also were obtained employing sitting drop vapor diffusion, however, the analogous Ru-labeled protein did not form crystals, even after several different crystallization experiments. Structures for each protein that highlight the linkage between the Ru-labeling site and azurin-Cu are shown in Figure 4. Crystallographic details are given in Table 1. The distances shown in Figure 4 are those between RuII and NO2YO−-C4; NO2YO−-C4 and CuII; and RuII and CuII (r1, r2 and rT, respectively). Justification of ET distances for mutants crystallized without Ru-labels is given in the Supporting Information.

Figure 4.

Structures of the electron transfer units of RuH107NO2YO−109 (PDB 4HHG, 1.6 Å) (A); H126NO2YOH122 (PDB 4HIP, 1.9 Å) (B), and H124NO2YOH122 (PDB 4HHW, 2.0 Å) (C) azurins. The peptide chain connecting the Ru-label, NO2YOH, and azurin-Cu is shown in cyan and the rest of the protein is shown as a gray ribbon. The distances between redox centers (see text) are shown above the black bars; the bars are not intended to show angles between cofactors. The inset in (A) shows Lys122. The Lys122(N) to NO2YO(Ophenolate) distance is 4.3 Å. Cu2+ is depicted as an orange sphere and Ru2+ in (A) is a turquoise sphere.

Table 1.

Crystallographic statistics.

| RuH107NO2YOH109 | H124NO2YOH122 | H126NO2YOH122 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB ID | 4HHG | 4HHW | 4HIP |

| Space group | I 2 2 2 | P 2 21 21 | P 2 21 21 |

| A,B,C | 49.762, 67.176, 81.385 | 49.669, 65.637, 72.561 | 49.546, 65.804, 73.005 |

| α,β,γ | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Observed reflections | 255277 | 71623 | 82347 |

| Unique reflections | 43899 | 16724 | 16630 |

| Completeness a | 98.92% (99.02%) | 98.42% (99.67%) | 98.99% (99.77%) |

| Rsym b | 12.3% | 4.3% | 4.2% |

| I/σI c | 5.1 | 21.6 | 22.6 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 1.60-51.81 | 2.0-49.67 | 1.90-49.55 |

| Rfree (e.s.u.) | 27.1% (0.112 Å) | 28.1% (0.237 Å) | 31.6% (0.203 Å) |

| Rworking set (e.s.u.) | 23.5 % (0.112 Å) | 22.4% (0.207 Å) | 25.0% (0.213 Å) |

| Mean B | 20.740 | 28.711 | 36.115 |

| RMS deviation: bond lengths | 0.022 | 0.021 | 0.015 |

| RMS deviation: bond angles | 2.439 | 1.913 | 1.862 |

Total (outer shell)

(SUM(ABS(I(h,i)-I(h))))/(SUM(I(h,i)))

mean of intensity/σI of unique reflections (after merging symmetry-related observations).

2.2 Electron Transfer Reactivity

Electron transfer kinetics were investigated using time-resolved laser spectroscopy, with excitation at 500 nm (where NO2YO− absorbance is negligible). In the absence of exogenous electron acceptors, *RuII(bpy)2(im)(HisX) (X=107, 124, 126) has a lifetime > 300 ns. Oxidation of CuI-azurin by *Ru was not observed, consistent with previous findings.7,8 RuIII(bpy)2(im)(HisX)CuI-azurin was generated using the flash-quench technique with 12 mM [Ru(NH3)6]Cl3 as oxidative quencher. A bleach of RuII(bpy)2(im)(HisX) absorption at 480 nm was consistent with production of RuIII(bpy)2(im)(HisX). Azurin-CuII could be quantitatively recovered upon addition of K3Fe(CN)6 after laser experiments.

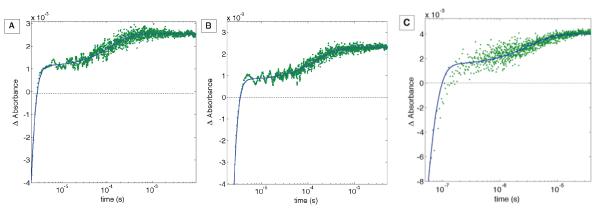

Oxidation of CuI to CuII in all three variants was monitored at 630 nm and the transients fit to a biphasic kinetics model; the first rate constant corresponds to decay of *RuII and the second to intramolecular oxidation of CuI by RuIII (Figure 5). Observed rate constants (khop) for CuI oxidation are set out in Table 2. The rate constants were independent of protein concentration between 18 and 60 μM in all cases. The state of the Ru complex was monitored at 480 nm: transient kinetics followed a double exponential function with the same rate constants found in the 630 nm traces. In all cases the fitting residuals were <5% of the total signal amplitude.

Figure 5.

Transient absorption traces (630 nm) for RuH107NO2YO−109 (A), RuH126NO2YO−122 (B) and RuH124NO2YO−122 (C) azurins. Kinetics traces are fit as described in the experimental section. The apparent bleach at very early times is due to residual luminescence from *Ru. The concentration of Ru(NH3)6Cl3 was 12 mM in each sample.

Table 2.

Electron transfer rate constants for nitrotyrosine-modified azurins.

3. Discussion

3.1. Structural and Thermodynamics Analyses

The X-ray structures of RuII(bpy)2(im)H107NO2YO−109, H124NO2YOH122 and H126NO2YOH122 azurins are similar to those of other modified and unmodified azurins.23,24 Electron density corresponding to the presence of NO2YOH was observed in all three variants. The H124NO2YOH122 and H126NO2YOH122 crystals are blue, indicating that the nitrotyrosine residues are protonated, although the crystallization experiment was performed at pH = pKa(NO2YOH122) where a 50/50 mixture of protonated and deprotonated species is expected. For RuII(bpy)2(imidazole)(H107)NO2YOH109 azurin, the pH of the crystallization experiment (7.2) would suggest that the nitrotyrosine in (pKa = 6.0) is largely deprotonated, but all Ru-labeled CuII-azurins are green, so the crystal color is not a reliable indicator of the nitrotyrosine protonation state. Inspection of the structure (Figure 4A) reveals that NO2YO−109 is in an environment that is distinct from that of NO2YOH122. First, NO2YO−109 is about 4.3 Å from Lys122 (ammonium-nitrogen to phenolate-oxygen distance). Second, an oxygen atom in the nitro group of NO2YO−109 is near (2.9 Å) the side chain oxygen of Thr124 (not shown in Figure 4A). Finally, the nitro group is rotated 38° out of the plane of the phenolate. In contrast to NO2YO−109, no substantial H-bonding or electrostatic interactions are apparent in the vicinity of NO2YOH122. The orientations of the NO2YOH122 aromatic ring and its nitro group are not affected by the presence of His at position 124 versus 126.

The H124NO2YOH122 and H126NO2YOH122 variants show an anodic voltammetric wave at ~1.1 V (pH 8.3) and pKa = 7.2; values that closely parallel those of related small molecules.15 Given the surface exposure and neutral electrostatic protein environment around NO2YOH122, the similarity to model complexes is reasonable. On the other hand, NO2YOH109 has a lower pKa (6.0) and anodically scanned differential pulse voltammograms exhibit a shoulder at ~1.2 V. Electrostatic interaction with Lys122, as well as the interaction of the nitro group with Thr124, could contribute to those apparent shifts. The influence of the nitro torsional angle on E° and pKa has not been reported. An internal H-bond between a nitro oxygen and the phenolic proton in 2-nitrophenol hinders rotation, 25 potentially explaining the difference in torsional angle in H107NO2YO−109 versus the other two NO2YOH-modified azurins. While pKa perturbation of NO2YOH residues is a useful tool for characterizing protein active sites,26 such perturbations arise from the interplay of many factors and do not provide any quantitative insight into the NO2YO•/−109 reduction potential.

3.2 Electron Transfer Reactivity

Detailed analysis of electron flow in the three NO2YO−-modified azurins requires reasonable estimates of reduction potentials, distances between cofactors, reorganization energies, and electronic couplings. The RuIII/II(bpy)2(im)2 reduction potential is assumed to be the same as that in the labeled proteins without NO2YOH residues (E° ~ 1.0 V16). We take E°(azurin-CuII/I) = 0.3 V,20 and use our CV/DPV data to estimate E°(NO2YO•/−122) = 1.10 ± 0.05 V, and E°(NO2YO•/−109) = 1.2 ± 0.1 V (Figure 3). We assume that Ru-photosensitizers do not dramatically alter the nitrotyrosine redox properties, which is reasonable because the sites are very weakly coupled (based on the close agreement between observed and the linear combination of component UV-vis spectra (see Supporting Information).

The Ru-Cu and Ru-NO2YOH distances for the H107NO2YOH109 protein were taken directly from the X-ray coordinates (Figure 4A). We used structures of related rhenium-labeled azurins24 to estimate the Ru-Cu distances in the RuH124NO2YOH and RuH126NO2YOH proteins (see Supporting Information). We use a center-to-center distance formulation in the preceding analysis, but the corresponding analysis for edge-to-edge distances also is given in the Supporting Information. This distance formulation does not affect the main conclusions.

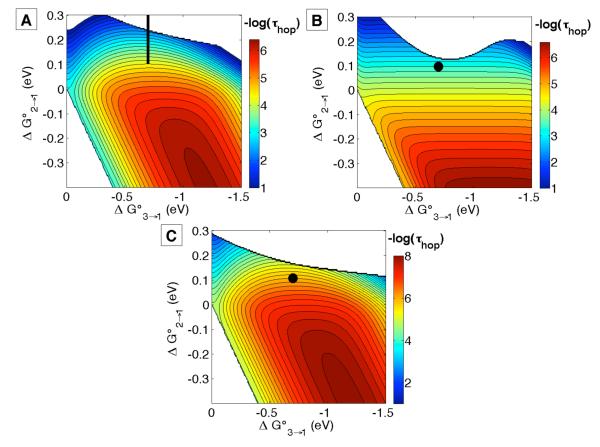

The maps in Figure 6 are calculated with HAB0 = 186 cm−1, β = 1.1 Å−1, and λ = 0.8 eV, the same as for our investigation of single-step ET in closely related azurins.8 As in those models, the Ru-label, NO2YO− residue, and a Cu-ligating residue (Cys112 or Met121) also are oriented on a single β strand (Figure 4). The sites are probably coupled similarly in the single step and hopping systems, so β = 1.1 Å−1 is a reasonable starting point for our analysis. Likewise, the value for λ was validated for single-step ET in Ru-modified wild-type azurins.7,8 A λ near 0.8 eV is able to account for the rate of bimolecular phenoxyl/phenolate electron self-exchange in basic water,27 as well as other similarly sized organic molecules,28 so use of our empirical λ is reasonable here. Additional hopping maps are presented in the Supporting Information that illustrate how subtle changes in ET distances, β, and λ can affect the shape of hopping maps and the predicted tunneling times.

Figure 6.

Hopping maps for NO2YO−-substituted azurins: (A) RuH107NO2YO−109 with r1 = 11.4, r2 = 16.7, rT = 25.4 Å; (B) RuH126NO2YO−122 with r1 = 14.2, r2 = 13.3, rT = 23.7 Å; and (C) RuH124NO2YO−122 with r1 = 7.8, r2 = 13.3, rT = 19.4 Å (Figure 4). In all maps λ = 0.8 eV, β = 1.1 Å−1, T = 298 K and HAB0 = 186 cm−1. The subscripts 1, 2, and 3 refer to RuIII, NO2YO− and CuI respectively. The contour lines are plotted at 0.2 log unit intervals. The black dots (or black bar in (A)) are at the driving forces given in the text. The calculated rate constants are set out in Table 2.

Specific rates of CuI oxidation (Table 2) are more than 10 times greater than those of single-step ET in the corresponding azurins lacking NO2YOH (107 or 122), confirming that NO2YO− accelerates long-range ET. We have shown that hopping maps can be used to estimate reaction times for generation of a product state in a three-site ET chain.6 Using the above reduction potentials and structural data, we constructed hopping maps to gain insight into NO2YO−-meditated intraprotein ET (Figure 6). In this case the proposed reaction sequence is [RuIII-NO2YO−-CuII] → [RuII-NO2YO•-CuI] → [RuII-NO2YO−-CuII], although the nitrotyrosyl radical intermediate was not detected by transient spectroscopy in any of the proteins investigated. Note that two-step hopping is a biphasic process, but the observed kinetics will appear single exponential under certain limiting conditions.29

The hopping maps predict electron transport times that are in good agreement with the experimentally determined rate constants (Table 2). Small fluctuations in driving forces, reorganization energies, and/or electronic couplings can affect the rate constants in hopping maps (see Supporting Information), but the predictions are still in accord with our experimental results. The experimental results also are consistent with the maps in Figure 1 (with −ΔG° = −0.1 eV for the intermediate step) as expected given that the maps are a product of semiclassical theory. Overall, we find that a 100-200 meV endergonic intermediate redox step with NO2YO− accelerates long-range ET by more than 10-fold.

3.3 Multistep Electron Transfer

The azurin-based hopping models described here provide structural data and thermodynamics estimates that can be used to analyze the design criteria taken from semiclassical ET theory (Figure 1). The driving forces do not vary widely, but the structural variations among model systems allow for analysis of the spatial factors that are central to functional hopping. Further, these model hopping systems employ a well characterized ground state oxidant, in contrast to previous investigations where electronically excited ReI was used as the electron acceptor.24 These reactions, involving ground or electronically excited electron acceptors, are models for biological hopping: the Ru-NO2YO− systems mimic ground state hopping in enzymes such as RNR (though ET there is proton-coupled3a), while the electronically excited Re systems mimic phototriggered hopping in proteins such as PS II.1

Although Trp-promoted CuI oxidation in Re-azurin was enhanced 100-fold,24a rates in the three NO2YO−-modified Ru-proteins increased by factors of just 10-50. This finding is attributable to differences in the driving force for the first step: for the Re-azurins it is near zero; for the Ru-proteins it is ≤ −0.1 eV. We predict that rate enhancements of up to 104 are possible with the appropriate driving forces and arrangement of redox sites (Figures 1 and 6). The first step becomes rate limiting when distance between the donor and intermediate is large, giving the hopping map a “ladder” appearance, and a parabolic boundary where single-step ET is favored at −ΔG31° ~ λ and ΔG21° > 0.1 eV (Figure 6).

The basic shape of each hopping map is unique (Figure 6), although each of these shapes could change with variations in ET parameters (see Supporting Information). The driving force ranges where hopping is predicted to be favored over single-step tunneling depend strongly on the distances between cofactors and the reorganization energies. The arrangement of cofactors that gives the widest range is that in which the redox intermediate is (spatially) closer to the start of the ET chain (e.g., RuH107NO2YO−109 and RuH124NO2YO−122). All else being equal, such systems are predicted to have the greatest hopping advantages (Figure 1). When the intermediate is closer to the ultimate electron/hole acceptor, the driving force associated with the first step effectively limits the ET rates. Native biological electron transport systems rarely employ the latter arrangement; the ones we have analyzed6 appear to have evolved cofactor arrangements that efficiently control electron or hole delivery as required for function.

Interestingly, RuH126NO2YO− azurin exhibits the greatest hopping advantage, with nonoptimal arrangement in which the first ET step occurs over a longer distance than the second. Modeling suggests that hopping is possible in such systems, but the energetic landscape is much different (Figures 1 and 6). We can rationalize the reactivity of RuH126NO2YO− azurin by distinguishing between the hopping advantage and the absolute hopping rate constant. Figure 1 illustrates that the maximum predicted hopping advantage increases as the total donor-acceptor distance increases (Figure 1, top row, 101 for 19.4 Å versus 102.5 for 25.7 Å). This finding is a result of the exponential distance dependence of ET reactions: breaking up a longer distance into shorter two steps has a greater impact than breaking up a shorter distance. Conversely, hopping systems with the shortest overall distances (e.g., 19.4 Å for RuH124NO2YO−122 azurin) cannot attain high hopping advantages, but produce the largest absolute rate constants by dividing a shorter ET distance into two steps of less than 10 Å. RuH107NO2YO−109 azurin has a hopping advantage slightly smaller than that for RuH126NO2YO−122 azurin, contradicting the predictions in Figure 1, but advantages gained by favorable cofactor arrangement can be offset by small changes in driving force, reorganization and/or electronic coupling pathways (see Supporting Information). Semiclassical theory provides important guidelines for designing hopping systems, but hopping advantages must be determined by experiment.

4. Conclusions

Efficient multistep electron transport requires careful redox cofactor arrangement and finely tuned reaction driving forces. We have shown that multistep ET between azurin-CuI and RuIII is enhanced over single-step reactions in three Ru-labeled azurins, providing an experimental demonstration of the interplay between driving force and cofactor arrangement in defining the hopping advantage. Semiclassical ET theory provides the insights needed to design systems that rapidly separate electrons and holes, and, importantly, maintain that separation on long time scales.

5. Materials and methods

Buffer salts were obtained from J. T. Baker. Tetranitromethane and imidazole were from Sigma-Aldrich. Terrific broth was from BD Biosciences. Solutions were prepared using 18 MΩ-cm water, unless otherwise noted. Ru(2,2′-bipyridine)2Cl2 and [Ru(NH3)6]Cl3 were from Strem Chemicals. Ru(NH3)6Cl3 was recrystallized prior to use.30 Mass spectrometry was performed in the Caltech Protein/Peptide MicroAnalytical Laboratory (PPMAL).31 UV-visible spectra were recorded on an Agilent 8453 diode array spectrophotometer. All data were collected atambient temperature (~293 K).

Plasmids encoding for mutant azurins were generated using the Stratagene Quikchange protocol. Proteins were expressed18 and tyrosine residues were nitrated19 using known protocols. Purity was assessed using UV-vis and mass spectrometry.

The pKas of nitrotyrosine residues were determined by adding aliquots of a concentrated azurin solution (in water, pH 7) to 100 mM phosphate-citrate buffer (pH 3-10) and measuring the optical spectra of the resulting solutions. Data at 430 nm were fit using Eqn. 1. Extinction coefficients (ε430) for NO2YO(H) were determined by comparison to the known values for azurin ( ε630 = 5700 M−1 cm−1).32 The ε430 were close to those for model complexes (4300 M−1 cm−1).15 The pKa values were independent of protein concentration between 10 and 60 μM. Clean isosbestic points in the UV-vis spectra for each titration are consistent with the mass balance assumption implicit in Eqn. 3.

| (3) |

Electrochemistry was carried out using a standard three-electrode setup: homemade basal-plane graphite (www.graphitestore.com) working electrode;33 Ag/AgCl reference electrode; Pt wire counter electrode. The working electrode was gently abraded with 600 grit wet/dry sandpaper and polished with 1 μM alumina power on a microcloth polishing pad for 30 seconds between each scan. For all voltammetry experiments, protein solutions were 1 mM in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.3) + 50 mM KCl. CVs were collected at a scan rate of 20 mV/s. DPVs were collected with the following parameters: pulse amplitude = 30 mv; pulse width = 100 ms; pulse period = 200 ms; sample width = 15 ms, increment = 2 mV. The potential of the observed waves was independent of concentration between 0.4 and 1 mM for each protein. Potentials were converted to NHE by adding 0.193 V.

X-ray quality crystals of NO2YOH-modifed azurin-CuII azurin were obtained as described previously.23 Azurin (~20 mg/mL in 40 mM imidazole + 2 mM NaCl, pH 7.2) was mixed with an equivalent volume of well solution containing 26-34% of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) 4000, 100 mM lithium nitrate, 6.25 mM copper sulfate and 100 mM imidazole, pH 7.2. The drops were equilibrated versus 1 mL of well solution. All experiments were incubated at room temperature and crystals were observed after 3 days. Diffraction data were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) beamline 12-2. The structures were solved by molecular replacement and then refined to the resolution limit from scaling/merging statistics. The coordinates of the structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (Table 1).

All transient spectroscopic measurements were conducted in the Beckman Institute Laser Resource Center at Caltech. Excitation (500 nm) was provided by an optical parametric oscillator (Spectra-Physics, Quanta-Ray MOPO-700) pumped by the third-harmonic of a Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (Spectra-Physics, Quanta-Ray PRO-Series, 8 ns pulse width), as described elsewhere.34 Note that the signal amplifier used in Figure 4A,B (ms timescales) is different from that in Figure 4C (μs timescales). Kinetics traces were collected at 630 and 480 nm for each protein sample. Protein samples were reduced using sodium ascorbate and desalted using PD-10 columns into 50 mM sodium phosphate + 50 mM NaCl (pH 8.0). The samples were deoxygenated by repeated pump-backfill cycles and left under an argon atmosphere for data collection. Data were fit using a function that takes into consideration signal from residual luminescence, as well as absorbance changes corresponding to the ET reaction of interest (Eqn. 4). The first rate constant corresponds to decay of electronically excited RuII and the second corresponds to intramolecular electron transfer from CuI to RuIII.

| (4) |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Our work was supported by NIH (DK019038 to HBG and JRW; GM095037 to JJW), an NSF Center for Chemical Innovation (Powering the Planet, CHE-0947829), and the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation. We also acknowledge the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Sanofi-Aventis Bioengineering Research Program for their support of the Molecular Observatory facilities at the California Institute of Technology. X-ray crystallography data was collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), a Directorate of the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Molecular Biology Program and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program (P41RR001209), and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Supporting Information. Detailed protocols for tyrosine modification and ruthenium labeling reactions, mass spec and UV-vis characterization, electron transfer distance determination in unlabeled proteins, additional hopping maps with variable λ and β parameters.

References

- 1 (a).Rappaport F, Diner BA. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008;252:259–272. [Google Scholar]; (b) McEvoy JP, Brudvig GW. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:4455–4483. doi: 10.1021/cr0204294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Siegbahn PEM. Dalton Trans. 2009;45:10063–10068. doi: 10.1039/b909470a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2 (a).Kaila VRI, Verkhovsky MI, Wikström M. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:7062–7081. doi: 10.1021/cr1002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brzezinski P, Aedelroth P. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006;16:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hosler JP, Ferguson-Miller S, Mills DA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:165–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.062003.101730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3 (a).Stubbe J, Nocera DG, Yee CS, Chang MCY. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2167–2201. doi: 10.1021/cr020421u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiang W, Saleh L, Barr EW, Xie J, Gardner MM, Krebs C, Bollinger JM. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8477–8484. doi: 10.1021/bi800881m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yokoyama K, Smith AA, Corzilius B, Griffin RG, Stubbe J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18420–18432. doi: 10.1021/ja207455k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4 (a).Mulder DW, Shepard EM, Meuser JE, Joshi N, King PW, Posewitz MC, Broderick JB, Peters JW. Structure. 2011;19:1038–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fontecilla-Camps JC, Volbeda A, Cavazza C, Nicolet Y. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:4273–4303. doi: 10.1021/cr050195z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5 (a).Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM, Dean DR. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012;16:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Danyal K, Mayweather D, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:6894–6895. doi: 10.1021/ja101737f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6 (a).Warren JJ, Ener ME, Vlček A, Jr., Winkler JR, Gray HB. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012;256:2478–2487. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Warren JJ, Winkler JR, Gray HB. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013;257:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7 (a).Gray HB, Winkler JRQ. Rev. Biophys. 2003;36:341–372. doi: 10.1017/s0033583503003913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gray HB, Winkler JR. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1797:1563–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gray HB, Winkler JR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:3534–3539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408029102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8 (a).Regan JJ, Di B,AJ, Langen R, Skov LK, Winkler JR, Gray HB, Onuchic JN. Chem. Biol. 1995;2:489–496. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90266-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Langen R, Chang I-J, Germanas JP, Richards JH, Winkler JR, Gray HB. Science. 1995;268:1733–1735. doi: 10.1126/science.7792598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Langen R. Ph.D. Thesis. California Institute of Technology; Pasadena, CA: 1995. Electron Transfer in Proteins: Theory and Experiment. [Google Scholar]

- 9 (a).Marcus RA, Sutin N. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;811:265–322. [Google Scholar]; (b) Barbara PF, Meyer TJ, Ratner MA. J. Phys. Chem. 1996;100:13148–13168. [Google Scholar]

- 10 (a).Curry WB, Grabe MD, Kurnikov IV, Skourtis SS, Beratan DN, Regan JJ, Aquino AJA, Beroza P, Onuchic JN. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1995;27:285–293. doi: 10.1007/BF02110098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Beratan DN, Skourtis SS, Balabin IA, Balaeff A, Keinan S, Venkatramani R, Xiao D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:1669–1678. doi: 10.1021/ar900123t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The maps in Figure 1 are derived in the same way as in Ref. 6a (variable driving forces and fixed distances), but here we fixed the driving forces and varied the distances between cofactors. MATLAB scripts for creating hopping maps. are available at: http://www.bilrc.caltech.edu/webpage/47.

- 12.The detailed derivation of Eqs. 4 and 5 is given in Ref. 6a.

- 13 (a).Sokolovsky M, Riordan JF, Vallee BL. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1967;27:20–25. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(67)80033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Riordan JF, Sokolovsky M, Vallee BL. Biochemistry. 1967;6:358–361. doi: 10.1021/bi00853a053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14 (a).Song N, Stanbury DM. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:11458–11460. doi: 10.1021/ic8015595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Costentin C, Louault C, Robert M, Savéant J-M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:18143–18148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910065106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Schrauben JN, Cattaneo M, Day TC, Tenderholt AL, Mayer JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:16635–16645. doi: 10.1021/ja305668h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15 (a).Yee CS, Seyedsayamdost MR, Chang MCY, Nocera DG, Stubbe J. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14541–14552. doi: 10.1021/bi0352365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) DeFelippis MR, Murthy CP, Broitman F, Weinraub D, Faraggi M, Klapper MH. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:3416–3419. [Google Scholar]

- 16 (a).Di Bilio AJ, Hill MG, Bonander N, Karlsson BG, Villahermosa RM, Malmström BG, Winkler JR, Gray HB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:9921–9922. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mines GA, Bjerrum MJ, Hill MG, Casimiro DR, Chang I-J, Winkler JR, Gray HB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:1961–1965. [Google Scholar]

- 17 (a).Warren JJ, Tronic TA, Mayer JM. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:6961–7001. doi: 10.1021/cr100085k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Warren JJ, Winkler JR, Gray HB. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang TK, Iverson SA, Rodrigues CG, Kiser CN, Lew AY, Germanas JP, Richards JH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:1325–1329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JC, Langen R, Hummel PA, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:16466–16471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407307101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gray HB, Malmström BG, Williams RJP. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2000;5:551–559. doi: 10.1007/s007750000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21 (a).Martínez-Rivera MC, Berry BW, Valentine KG, Westerlund K, Hay S, Tommos C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:17786–17795. doi: 10.1021/ja206876h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Berry BW, Martínez-Rivera MC, Tommos C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:9739–9743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112057109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang IJ, Gray HB, Winkler JR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:7056–7057. [Google Scholar]

- 23 (a).Crane BR, Di Bilio AJ, Winkler JR, Gray HB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11623–11631. doi: 10.1021/ja0115870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Faham S, Day MW, Connick WB, Crane BR, Di B, Angel J, Schaefer WP, Rees DC, Gray HB. Acta Crystallographica Section D Acta Cryst. D. 1999;55:379–385. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998010464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24 (a).Shih C, Museth AK, Abrahamsson M, Blanco-Rodriguez AM, Di B., Angel J., Sudhamsu J, Crane BR, Ronayne KL, Towrie M, Vlcek A, Jr., Richards JH, Winkler JR, Gray HB. Science. 2008;320:1760–1762. doi: 10.1126/science.1158241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Blanco-Rodríguez AM, Busby M, Ronayne K, Towrie M, Gradinaru C, Sudhamsu J, Sykora J, Hof M, Zalis S, Bilio AJD, Crane BR, Gray HB, Vlcek A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11788–11800. doi: 10.1021/ja902744s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hargittai I, Borisenko KB. J. Mol. Struct. 1996;382:171–176. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yokoyama K, Uhlin U. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8385–8397. doi: 10.1021/ja101097p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuler RH, Neta P, Zemel H, Fessenden RW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:3825–3831. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Analyses of ET reactions of several small organic molecules indicate reorganization energies less than 1 eV. See: Eberson L. Adv. Phys. Org. Chem. 1982:79–185.

- 29.Here, the total tunneling times can be roughly approximated by calculating the ET rates between RuIII and NO2YO− using semiclassical theory (Eq. 1) and the ET parameters set out in Figure 6. Driving force optimized forward ET (CuI to NO2YO•) is approximately 100 times faster than the first ET step from NO2YO− to RuIII. This also is consistent with our inability to observe NO2YO• intermediates.

- 30.Meyer TJ, Taube H. Inorg. Chem. 1968;7:2369–2379. [Google Scholar]

- 31. http://www.its.caltech.edu/~ppmal/

- 32.Rosen P, Pecht I. Biochemistry. 1976;15:775–786. doi: 10.1021/bi00649a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blakemore JD, Schley ND, Balcells D, Hull JF, Olack GW, Incarvito CD, Eisenstein O, Brudvig GW, Crabtree RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:16017–16029. doi: 10.1021/ja104775j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dempsey JL, Winkler JR, Gray HB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;132:1060–1065. doi: 10.1021/ja9080259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.