Abstract

Small variations in nucleic acid sequences can have far-reaching phenotypic consequences. Reliably distinguishing closely related sequences is therefore important for research and clinical applications. Here, we demonstrate that conditionally fluorescent DNA probes are capable of distinguishing variations of a single base in a stretch of target DNA. These probes use a novel programmable mechanism in which each single nucleotide polymorphism generates two thermodynamically destabilizing mismatch bubbles rather than the single mismatch formed during typical hybridization-based assays. Up to 12,000-fold excess of a target containing a single nucleotide polymorphism is required to generate the same fluorescence as one equivalent of the intended target, and detection works reliably over a wide range of conditions. Using these probes we detected point mutations in a 198 base pair subsequence of the E. Coli rpoB gene. Our probes are constructed from multiple oligonucleotide fragments, circumventing synthesis limitations and enabling long continuous DNA sequences to be probed.

Nucleic acids are the genetic signature molecules for all life; sequences and expression levels of biological nucleic acids provide information about the state of an individual cell or a whole organism. Often, small differences — even single base changes — between otherwise identical nucleic acid sequences can have important biological and biomedical implications: single base mutations such as insertions, deletions, and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) form the genetic basis for a variety of human diseases [1, 2] or can confer drug resistance to pathogenic bacteria or viruses [3, 4]. Consequently, the fast, simple, and accurate detection, analysis, and quantitation of nucleic acid sequences with single base resolution are important research goals with vast potential for biomedical applications.

Virtually all nucleic acid detection technologies utilize the specificity of Watson-Crick base pairing; single-stranded probe [5] or primer [6] molecules capture intended DNA or RNA target molecules of complementary sequence. However, cross-hybridization between closely related probe-target pairs can occur; such imperfect probe-target binding may be kinetically trapped (i.e. dissociate slowly) and practically prevent intended hybridization reactions. In order to achieve single-base specificity, many diagnostic assays exploit the sensitivity of enzymes [8–11] to the presence of mismatch bubbles within their DNA substrates. DNA-templated, nonenzymatic ligation reactions can also be highly sensitive to point mutations in the template [12, 13].

Alternatively, the complementary probe molecules themselves can be engineered to possess greater specificity to the intended target molecule. For example, incorporation of chemically modified bases [14, 15] can increase the affinity of a probe to a correct target. Consequently, disruption of correct base pairing results in a higher energetic penalty and better discrimination [16, 17]. Hairpins and other structural elements can be introduced into the probe molecule to make binding to both the correct and SNP target less energetically favorable such that small energetic differences can result in strong differences in the hybridization yield [18–20]. However, reaction conditions often need to be finely tuned for optimal performance, and it is difficult to assay long nucleic acid molecules for single base changes. A comprehensive review of SNP detection methods can be found in [2].

Here we present a class of conditionally fluorescent molecular probes that effectively discriminate single-base changes in primarily double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), work robustly for a wide range of conditions, and identify single base changes within long stretches of DNA. Our approach relies on a novel mechanism that we termed “double-stranded toehold exchange,” and uses a rationally designed double-stranded probe with forked single-stranded overhangs (Fig. 1a). We first demonstrated our probes on a set of synthetic dsDNA targets. The reaction of the probe with any SNP target – a molecule that differs from the intended target by a single base pair – exhibited negligibly low yield. Experimentally, up to a 12,000-fold excess of a target was needed to achieve the same fluorescence signal as a stoichiometric amount of the intended target, comparable to the best enzyme-based methods. Subsequently, we extended our approach to the detection of point mutations in the E. coli rpoB gene. Our probes correctly identified point mutations responsible for resistance to the antibiotic rifampicin [21, 22].

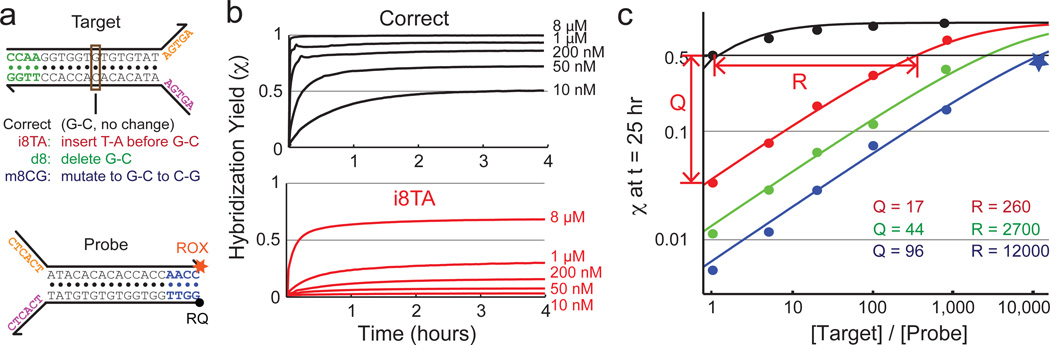

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the double-stranded toehold exchange mechanism (a) The reaction starts with the hybridization of the initiation toeholds (orange and purple), forming a four-stranded complex C0. Next, the four-stranded complex undergoes a series of single-base reconfiguration events known as branch migration [23]. The various states of branch migration (Ci) are roughly isoenergetic, and thus each branch migration step is reversible and unbiased. When the branch migration reaches state Cn where the four-stranded complex is held together only by the dissociation toeholds (blue and green), these dissociation toeholds can spontaneously dissociate to release the two product molecules. (b) A highly specific, conditionally fluorescent molecular probe based on four-stranded toehold exchange. The probe is functionalized at the balancing toeholds with a fluorophore and a quencher on separate strands; at the end of the reaction, the fluorophore is delocalized from the quencher and fluorescence increases. The lengths and sequences of the toeholds are designed so that the of reaction between the probe and the intended target is roughly 0. The reaction between the probe and the SNP target will result in two mismatch bubbles, and the reaction will be about 8 kcal/mol. (c) Plot of the analytic hybridization yield (χ) at equilibrium of the reaction against the reaction ΔG˚ (assuming that identical initial concentrations of A and B). Designing ensures a balance of high specificity and high yield.

Double-stranded toehold exchange

The double-stranded toehold exchange mechanism is shown in Fig. 1a. The reactants (A and B) are two primarily double-stranded nucleic acid molecules; each possesses single-stranded overhangs at the 5’ end of one strand and at the 3’ end of the other. These overhangs, shown in orange and purple, are termed initiation toeholds. Toeholds of matching color are complementary to each other, and hybridize to initiate the reaction. The initial four-stranded complex (C0) then undergoes a “branch migration” process through a series of isoenergetic four-stranded states (C1 through Cn) [23]. Finally, when the branch migration reaches the other terminus (Cn), the blue and green dissociation toeholds spontaneously fall apart to release two primarily double-stranded products (D and E).

The equilibrium concentrations of the various states depend on the length and base compositions of the toeholds, as well as the length of the homologous branch migration region (shown in black, see Text S1). In solutions with low divalent metal cation concentrations, the transition rates between different intermediate C states are high [26], and the reaction is rate limited by toehold association and dissociation processes. With proper selection of toehold strengths, both the forward and reverse kinetics are fast, and the reaction rapidly equilibrates from any initial state.

We here focus on the problem of constructing high specificity probes for SNP detection, we envision that the double-stranded toehold exchange can also be used for a variety of other applications, such as the modular construction of complex biomolecular circuits for the logical and temporal control of DNA [27–32] and other molecules [33–35].

Conditionally fluorescent dsDNA probe

To adapt the double-stranded toehold exchange mechanism into highly specific molecular probes for dsDNA (Fig. 1b), we designed the initiation and dissociation toeholds to be similar in length and sequence so that the reaction with the intended target has . The reaction with SNP targets will have that is about +8 kcal/mol [36], due to the formation of the two mismatch bubbles (Fig. 1b). The probes discriminate intended targets from SNP targets by taking advantage of the fact that small ΔG˚ changes near ΔG˚ = 0 have disproportionately large effects on the hybridization yield χ (Fig. 1c). Because is designed to be approximately 0, a favorable balance is achieved between the binding yield of the intended target (roughly 50%) and the specificity (within a constant factor of optimal, see Fig. 1c and Text S2). Thus, the probe is designed to bind specifically to one particular sequence; a spurious molecule that differs by even a single base pair from the intended target, regardless of position within the duplex, exhibits significantly lower binding at equilibrium.

We use fluorescence to directly measure hybridization yield. At the opposite end of the initiation toeholds, the probe is functionalized with a fluorophore on one strand and a quencher on the other strand; the close proximity of the fluorophore and quencher ensures that the probe is natively in a dark state. Upon completion of the double-stranded toehold exchange, the fluorophore and quencher are no longer colocalized on the same molecule, and fluorescence increases.

To implement the desired criterion, we designed the initiation toeholds (orange and purple) to form 5 base pairs (bp) each, and the dissociation toeholds (blue and green) to form 4 bp each (see Text S1 for discussion on toehold lengths). The dissociation toeholds are shorter than the initiation toeholds because the interaction between the fluorophore and quencher stabilizes the reactants [37].

Results

To test whether the fluorescent probe based on double-stranded toehold exchange functions as intended, we first designed an arbitrary 14 base pair dsDNA sequence. The initiation and dissociation toeholds (see Methods for sequence design) were then appended to the ends, resulting in an intended target molecule with 18 base pairs. To facilitate experimentation on the effects of reaction ΔG˚, we designed the probe to each possess 6 nt of initiation toehold, but the effective toehold is determined by the shorter of the toeholds for the probe and the target, and the latter was designed to be 5 nt for the experiments shown here in the main text. Fourteen SNP target molecules were designed that each differed from the intended target by one base pair (Fig. 2a). These base changes were distributed at three different positions along the testing region, and included insertions, deletions, and replacements.

FIG. 2.

Discrimination of SNPs by the dsDNA probe. (a) Sequence of the intended target and the positions/identities of base pair changes that lead to the 14 SNP targets. Circled 1, 2, and 3 denote the positions of the mismatch. Mismatches, insertions, and deletions are respectively shown in blue, red, and green. (b) Hybridization yield, as inferred from fluorescence kinetics (see Fig. S1 and Methods). The probe is present in solution initially, and the intended or SNP target is introduced at t ≈ 0. Experiments were run at 25 °C in 1 M Na+. The trace for intended target is shown in black, and traces for SNP targets are shown in the colors described above (see Fig. S2 for zoom-in of SNP reactions). (c) Reactions equilibration appears to be complete after 4 hours; to ensure equilibration, however, the reactions were allowed to proceed until t = 25 hr. The hybridization yields at t = 25 hr are taken to be the equilibrium values, and discrimination factors are calculated for each SNP target. Observed Q values range between 17 and 99 (median = 43). Error bars show standard deviations calculated from three repetitions of each experiment.

Fig. 2b shows the inferred hybridization yield , where D is the fluorescent product and [B]0 is the initial concentration of probe (for all experiments, [A] ≥ [B]). See Methods and Fig. S1 for details on derivation of χ from raw fluorescence values. The discrimination factor quantifies the single-base specificity of the probe as the ratio of the hybridization yields (fluorescence) generated by equal concentrations of the intended and SNP targets; Q at t = 25 hr is plotted in Fig. 2c, and ranged between 17 and 99, with a median of 43. Operation of the probe is robust to the concentration of the probe; at lower probe concentrations, kinetics are slower, but discrimination at equilibrium is preserved (Fig. S3).

For spurious targets that differ from the intended target by more than one base pair, analysis predicts that the discrimination factor will be roughly exponential in the number of base pair changes (e.g. a spurious target with 2 base pair changes would yield a discrimination factor of roughly Q ≈ 432 ≈ 1800). However, the sensitivity of our equipment precludes the accurate measurement of hybridization yields lower than about 0.002; consequently, spurious targets that differ by two or more base pairs were not tested.

It is important to note that, like molecular beacons and other nucleic acid hybridization probes, our double-stranded probe does not in itself employ molecular or fluorescence amplification. For our E. Coli experiments, the colony PCR step provided the amplification to generate enough target for fluorescence analysis. Without amplification, the sensitivity of our probes is limited by the sensitivity of the fluorescence readout. For a typical fluorimeter, the sensitivity limit is around 100 pM of unquenched fluorophores (Fig. S4).

Concentration equivalence

The concentration equivalence R denotes the excess of SNP target needed to yield the same level of fluorescence (50% of maximum) as that of the intended target at equal concentration to the probe. An R-fold excess of the SNP target yields a false positive, so R determines the specificity of a diagnostic assay based on this technology. For typical hybridization probes, R ≈ Q; however, for our double-stranded probes, the value of R is approximately Q2 (see Text S3 for mathematical details). The quadratic relation between R and Q is due to the fact that there are two products whose concentrations will increase to compensate for an increase in target concentration to maintain equilibrium: for the same value of , both [D] and [E] increase to balance out an increase in [A]. An increase in the amount of SNP targets will thus only have a square root effect on the observed fluorescence (rather than a linear effect); consequently, high stoichiometric ratios of SNP targets have a much smaller effect on the double-stranded probes than on standard hybridization probes.

Fig. 3b shows the response of the probe to various concentrations of the intended target and one particular SNP target “i8TA.” Whereas 10 nM of the intended target results in approximately 50% hybridization yield at equilibrium (χ∞ = 0.5), between 1 and 8 µM of the SNP target is needed to generate the same yield (fluorescence), indicating that the R for “i8TA” is between 100 and 800. Similar experiments were performed for two additional SNP targets, “d8” and “m8CG, ” and the hybridization yields χ of these reactions at t = 25 hr are plotted against the concentrations of the SNP targets in Fig. 3c. The solid lines in Fig. 3c show the analytic dependence of equilibrium χ on the concentrations of the intended and SNP targets using best-fit reaction ΔG˚ (Text S2). Listed R values show the horizontal distance between black curve for the intended target and the colored curves for the SNP targets. The listed Q values are determined from the hybridization yields at 1:1 stoichiometry of target to probe after 25 hours of reaction. Thus, experiments verify that R varies roughly as the square of Q.

FIG. 3.

Analysis and measurement of the concentration of SNP target needed to generate the same hybridization yield as a stoichiometric (relative to probe) amount of intended target (concentration equivalence R). (a) Sequences of intended and SNP targets used for experiments in this figure. (b) Hybridization yields (χ) of various concentrations of intended and “i8TA” SNP target. In all traces, initial probe concentration [B]0 = 10 nM. (c) Hybridization yields plotted against the stoichiometric ratio of the target. As with previous experiments, the hybridization yield was inferred from fluorescence value at t = 25 hr. Experimentally determined values are shown as dots and star, and solid lines show the analytic model prediction based on best-fit ΔG˚ values (Text S1). All experiments other than the star data point were performed with 10 nM probe; the star data point reaction was performed with 2 nM probe to conserve reagents. Concentration equivalence R values are calculated based on best-fit models at 5% hybridization yield, and ranges between 260 and 12,000. Analysis shows and experiments verify that R ≈ Q2, with being the discrimination factor.

Robustness

Diagnostic assays of DNA samples benefit from solution robustness because biological samples or PCR products can be directly analyzed without separate purification and/or buffer exchange procedures. The primarily double-stranded nature of the targets and probes confers a high degree of robustness to non-cognate single-stranded nucleic acids in solution. Fig. 4a shows that discrimination is robust in up to 30 µM of a 50 nucleotide polyN sequence mixture (in which every position has roughly equal probability of being G, C, A, or T). In contrast, probes and reactions based on single-stranded oligonucleotides are significantly affected by 1 µM of polyN sequence mixture [31].

FIG. 4.

Characterization of the background, temperature, salinity, and time robustness of the probe. The probe operates robustly to discriminate SNPs (a) in the presence of high concentrations of 50 nt polyN strands, (b) in different salinity buffers, and (c) at different temperatures (see also Fig. S5 and S6). (d) The discrimination factor Q approaches its final value after about 10 minutes of reaction, and maintains high discrimination indefinitely. The initial rise and bumpiness in Q can be attributed to fluorescence signal instability directly following addition of target to solution (see Fig. S2).

Likewise, temperature robust diagnostic assays would be desirable in point-of-care and/or resource-limited settings, where precise temperature control equipment may not be available. At different salinities or temperatures, the ΔG˚ ≈ 0 property required for high specificity is preserved because changes to the thermodynamic favorability of base pairing affects both the reactants and products equally; consequently, probes should be highly specific at equilibrium across a wide range of temperatures and salinities. Experimentally, the probes showed high discrimination at equilibrium between the intended target and the SNP target in 1× PBS, 10× PBS, 12.5 mM Mg2+, and 125 mM Mg2+ (at 25 °C, Fig. 4b) and at 10 °C, 25 °C, 37 °C, and 50 °C (in 1 M Na+, Fig. 4c).

We next asked how quickly our probes could distinguish an SNP target from an intended target. For this, we calculated the hybridization yields for the data in Fig. 2b as a function of time; that is, we divided the fluorescence values for an SNP target by the fluorescence value for the intended target at each time point (Fig. 4d). We found that Q > 10 for all SNP targets less than 20 minutes after the initiation of the reaction; thus a reliable result is obtained long before the detection reaction reaches equilibrium, and this high Q is maintained indefinitely (Fig. 4d). In contrast, previous double-stranded DNA probes that utilize four-way branch migration [26, 38–41] do not use the dissociation toeholds and discriminate SNPs using kinetics; consequently, at equilibrium, both intended and SNP targets will be nearly 100% bound to probe and discrimination is only possible at early time points in the reaction, increasing the likelihood of false positive results (Fig. S7 and S8).

Finally, we performed a number of experiments comparing the SNP discrimination performance of our dsDNA probes to molecular beacons (Fig. S9 and S10). In all cases, dsDNA probes showed significantly higher discrimination factors; this was particularly true for experiments targeting a subsequence of the E. Coli rpoB gene, as the target had significant secondary structure. Our dsDNA probes were not affected by secondary structure, and furthermore could reliably distinguish 1 nucleotide change within 198 nt, whereas molecular beacons were limited to detection of 1 nucleotide change within 15 nt.

Biologically-derived samples

Single base mutations in bacterial genomes can confer resistances to antibiotics. For example, the rpoB gene encodes the β subunit of bacterial RNA polymerase; many mutations in rpoB preserve polymerase function but confer rifampicin-resistance in E. coli, M. tuberculosis, and other bacteria [21, 22]. To prevent widespread antibiotic resistance, it is desirable to treat non-rifampicin resistant infectious bacteria with rifampicin, and resort to less widespread drugs only when necessary. To facilitate such tactical use of antibiotics, fast, accurate, and low-cost drug resistance assays are needed.

As a proof-of-concept demonstration that double-stranded toehold exchange probes can be used for drug resistance assays, we designed and tested three probes targeting subsequences of the rpoB gene (Fig. 5a). The two shorter probes tested nucleotides 1531–1599 and 1684–1728 (corresponding to codons 511–533 and 562–576). The probes were functionalized with spectrally distinct fluorophores (ROX and Tye563), and operated simultaneously in solution. The longer probe tested the entire 198 base pair subsequence from 1531–1728 (codons 511–576). The target DNA was generated from E. coli colonies via a two-step process: colony PCR was first used to pre-amplify the rpoB subsequence, and unbalanced PCR was used to generate each of the two strands that comprise the target (Fig. 5b).

FIG. 5.

Detection of SNPs in E. coli-derived samples. (a) Rifampicin resistance is typically confered by mutations in one of two regions in the rpoB gene, nucleotides 1531–1599 and 1684–1728, corresponding to amino acid residues 511–533 and 562–576. Here, we generated three distinct probes, one to test each region, and one to test both simultaneously. See Fig. S17 for sequences of probes and targets. (b) DNA from ten rifampicin-resistant colonies were extracted and individually amplified by colony PCR. Subsequently, unbalanced PCR using an excess of one primer with an overhang is used to generate the initiation toeholds. These DNA samples were allowed to react with our fluorescent probes. The probes were constructed by annealing four separate oligonucleotides, and possessed non-overlapping nicks that do not interfere with probe function. (c) The left side of each column shows the approximate position of the mutations, as determined by sequencing. The right side of each column shows the fluorescence response of the rpoB subsequences to the two fluorescent probes. A mutation in the green (blue) region would result in no increase in the fluorescence for Probe 1 (Probe 2), as shown in the green (blue) trace. The experimental results agree with the sequencing results in all experiments. The fluorescence data shown for the left experimental panels represents the behavior over 3 hours of reaction; the right panels show 10 hours of reaction. See Fig. S11–S15 for zoomed-in view of data.

Probes used here were discontinuous and were assembled from 4 complementary overlapping sequences, rather than just 2 (Fig. 5b). This design changes was necessary because fluorophore- or quencher-functionalized oligonucleotides of more than 50 nt cannot be efficiently synthesized. Our experiments revealed that the probe effectively discriminates SNPs despite nicks in the branch migration region.

Experimentally, DNA from all ten rifampicin-resistant colonies exhibited mismatch behavior in either the 1531–1599 region or the 1684–1728 region; in contrast, the wild-type DNA induced increase in fluorescence for probes targeting both regions (Fig. 5c, Fig. S11–S15). Sequencing confirmed the presence of one or more mutations in these two regions for all ten colonies.

The probes for the 1531–1599 region and for the 1684–1738 region utilized different toehold sequences; the difference in toehold strengths may have contributed to the different kinetics observed for the blue and green traces in Fig. 5c. Kinetics are highly sensitive to toehold thermodynamics (e.g. 0.4 kcal/mol change results in 2-fold difference in kinetics). However, equilibrium-based probes, such as the double-stranded toehold exchange probes present here, are robust to these kinetic differences.

We also demonstrated that similar probes and targets with only one initiation toehold and one dissociation toehold function to reliably discriminate single-base changes, albeit with slower kinetics than probes using forked toeholds (Fig. S16). Target and probe molecules with only a single overhang are more easily prepared from biological samples, e.g. using a restriction enzyme or PCR with a modified primer.

Discussion

Using the mechanism of double-stranded toehold exchange, we developed a novel technology for the reliable detection of individual base pair changes in double-stranded DNA. Our discrimination method worked reliably for a wide range of mutations at different positions within a duplex, with a median discrimination factor Q = 43. Detection was robust to changes in temperature and salinity, and even to up to 30 µM of a mixture of non-cognate single-stranded DNA (representing a 3000-fold excess over probe and target concentrations). Depending on the type of base change, a 260- to 12,000-fold excess of the SNP target was tolerated before the signal due to the mutated target became comparable to that of a correct target.

The high specificity of our probes derives from a combination of two factors: First, we rationally designed the probes to react with the intended target with ΔG˚ = 0, where slight thermodynamic changes due to a single-base mismatch have a disproportionately large effect on the hybridization yield. Specificity is reduced when ΔG˚ < 0, for example when initiation toeholds are significantly longer than dissociation toeholds (Fig. S18). Second, our assay has the advantage that a base pair change in the target leads to the formation of two mismatch bubbles in the reaction products. Assays that probe single-stranded targets yield only one mismatch bubble per base change, and the smaller ΔG˚ change between correct and SNP target cannot be distinguished as easily based on thermodynamics.

We further showed that correct and mutated targets can already be clearly distinguished during the approach to equilibrium. Under conditions where reaction equilibration occurs on the time scale of hours, we were able to identify all mutated targets within the first 20 minutes of the reaction, and fluorescence discrimination was maintained for the remainder of the 25 hours in which we observed the reactions.

The ability to identify single point mutations is critical for diagnosing antibiotic resistance in TB and other diseases [43, 44], because most drug resistances can be traced to individual point mutations in narrowly defined regions within a few genes (see e.g. Ref. [4]). Our probes can be used to screen extended genetic regions (potentially containing multiple SNPs in different positions) and can be multiplexed to screen mutations occurring in different genes, making this a promising technology for developing rapid and reliable infectious disease diagnostics. As a first step in this direction, we used our method for the detection of mutations that confer rifampicin resistance to E. coli. Probes were constructed to test two highly variable regions of the rpoB gene and also a 198 base pair domain encompassing both regions. DNA from wild-type E. coli and 10 different resistant colonies were reacted with probes, and sequencing confirmed that probes correctly detected the presence of single base pair changes in all cases. Furthermore, we demonstrated multiplexing — two probes labeled with different fluorophores functioned simultaneously in the same detection reaction. This could allow the use of an internal control probing a conserved sequence to compensate for sample-to-sample variability.

Importantly, these experiments on biologically-derived target DNA utilized discontinuous probes that contain non-overlapping nicks. With this approach, we were able to significantly increase the read length of molecular probes, which traditionally has been 50 nt or fewer due to synthesis limitations and also due to reduced specificity of long oligonucleotide hybridization. We demonstrated the ability to detect a single base change in a continuous region of DNA 198 base pairs long, and we envision that this technology can be extended to enable SNP detection in significantly longer DNA, potentially even probing lengths necessary to solve the haplotype phasing problem [42]. Furthermore, by using our discontinuous dsDNA probes, we enable a highly accurate “sequence comparison” mechanism that could function as a complement to next generation sequencing technologies (current sequencing reads are limited to less than 500 nt).

Finally, our probes can even be useful for the detection of single-stranded targets that are first converted to dsDNA with forked toeholds using PCR-based methods. Single-stranded nucleic acids often have considerable secondary structure at or near room temperature. Such self-interactions within a target or a single-stranded probe can interfere with the detection reaction, both at a kinetic level [50, 51] or at a equilibrium thermodynamics level [31, 52]. The double-stranded nature of our probe and target discourages undesirable pathways that lead to either kinetic traps or spurious interactions. Such a procedure would not necessarily increase the complexity of the detection process, since most existing nucleic acid detection technologies require a PCR-based pre-amplification step.

Methods

Probe design

We designed pairs of forked toeholds with self-similar sequences to avoid secondary structure (e.g. for target in Fig. 2, orange toehold is 5’-AGTGA-3’ and purple toehold is 3’-AGTGA-5’); this is true for both initiation toeholds and dissociation toeholds. This allows accurate prediction of probe binding thermodynamics and kinetics.

DNA oligonucleotides

All DNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technology (IDT). Fluorophore- and quencher-labeled oligonucleotides were HPLC purified; non-labeled oligonucleotides used in Fig. 5 were purchased as Ultramers; primers for PCR were unpurified; all remaining oligonucleotides were PAGE purified. Individual DNA oligonucleotides were resuspended to 100 µM and stored in EB buffer (10 mM Tris · HCl, pH 8.5; Qiagen).

IDT provided Electrospray Ionization mass spectrometry data sheets as quality control; Fig. S19 shows one representative ESI spectrum and Table S3 shows a summary of all ESI results (all 47 oligonucleotides showed over 75% purity, and 45 oligonucleotides were over 90% pure).

Probe preparation

Probe molecules consist of either two distinct strands (Fig. 2 through 4) or four distinct strands (Fig. 5). The strands are mixed stoichiometrically and then thermally annealed (Biorad T100), cooling uniformly from 98 °C to 25 °C over the course of 73 minutes. Two-stranded probe molecules were then gel purified to ensure stoichiometry using a 10% polyacrylamide gel; four-stranded probe molecules were not purified.

Gel solutions were prepared from 40% 19:1 acrylamide:bisacrylamide stock (J.T. Baker Analytical) in 1× tris-acetate-EDTA buffer (TAE)/Mg2+ solution, and cast between 20 cm by 20 cm glass plates with 1.5 mm spacers. Samples were loaded with 80% glycerol to achieve 10% glycerol concentration by volume. The gel was run at room temperature using Hoefer SE600 chamber at 140 Volts for 4 hours. Gel bands were visualized using Entela UL3101 UV light, using a fluorescent backplate (Whatman UV254 Polyester 4410222), and then cut out and eluted into 1 mL buffer.

Target preparation

Target molecules used in Fig. 2 through 4 were prepared similarly to two-stranded probes, via annealing and purification as described above. E. coli-derived targets used for Fig. 5 were constructed in a multistep process. 10 µL of competent cells were cultured in 5 mL LB at 37 °C for 48 hours, and then split into 1 mL aliquots. Each aliquot was centrifuged for 10 minutes, after which supernatant was decanted. Precipitate was resuspended in 200 µL LB and plated on a LB plate with either 0 µg/mL (wild-type) or 300 µg/mL rifampicin (Sigma R3501). Colonies were allowed to form overnight at 37 °C.

Ten rifampicin-resistant colonies were picked from the plates, and each was amplified with colony PCR (13 minutes at 98 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 98 °C (15 s), 50 °C (20 s), and 72 °C (40 s), followed by 5 minutes at 72 °C; Biorad T100) with 500 nM of each primer. Subsequently, colony PCR amplification products were used as templates for unbalanced PCR (with 500 nM of one primer and 5 nM of the other, 40 cycles). Both primers had a designed toehold at the 5’ end that would serve as initiation or dissociation toehold experiments. The two strands of the target were constructed using unbalanced PCR separately, and annealed afterwards.

Time course fluorescence studies

Kinetic fluorescence measurements were performed using a Horiba Fluoromax 3 spectrofluorimeter and Hellma Semi-Micro 114F spectrofluorimeter cuvettes. Probes targeting the 562–576 codon region of the rpoB gene in Fig. 5 used the TYE563 fluorophore (excitation 549 nm; emission 563 nm). For all other experiments, probes used the ROX fluorophore (excitation 584 nm, emission 603 nm). Slit sizes were set at 5 nm for all monochromators. An external temperature bath maintained a designated reaction temperature (25±1 °C unless explicitly stated in Fig. 4).

A four-sample changer was used, so that time-based fluorescence experiments were performed in groups of 4. For simultaneous detection experiments in Fig. 5, each data point represents the integrated fluorescence over 10 seconds per two minutes of reaction. For all other experiments, each data point represents the integrated fluorescence over 10 seconds per minute of reaction.

Fluorescence normalization and hybridization yield inference

All fluorescence values were normalized and converted into hybridization yields χ via the following formula:

where F is observed fluorescence, Fb is background fluorescence observed due to the addition of only buffer, and Fs is the saturated fluorescence observed after addition of a 40-fold excess of correctly-matched target. See Fig. S1 for details.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Eric Klavins for insightful discussion and helpful manuscript preparation suggestions. This work was funded by NIH Award 1K99EB015331 to D. Y. Z., by NSF CAREER Award 0954566 to G. S, and by a DARPA Young Faculty Award to G. S.

Footnotes

Author contributions. S. X. C., D. Y. Z., and G. S. conceived the project and designed the experiments. S. X. C. conducted the experiments. S. X. C., D. Y. Z., and G. S. analyzed the data and co-wrote the paper.

There is a patent pending on the methods described in this work.

References

- 1.Gunderson KL, Steemers FJ, Lee G, Mendoza LG, Chee MS. A genome-wide scalable SNP genotyping assay using microarray technology. Nature Biotechnology. 2005;37:549–554. doi: 10.1038/ng1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim S, Misra A. SNP genotyping: technologies and biomedical applications. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2007;9:289–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.152037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold C, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphism-based differentiation and drug resistance detection in Mycobacterium tuberculosis from isolates or directly from sputum. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2005;11:122–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bang H, et al. Improved rapid molecular diagnosis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis using a new reverse hybridization assay, REBA MTB-MDR. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2011;60:1447–1454. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.032292-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schena M, Shalon D, Davis RW, Brown PO. Quantitative Monitoring of Gene Expression Patterns with a Complementary DNA Microarray. Science. 1995;270:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saiki RK, Gelfand DH, Stoffel S, Scharf SJ, Higuchi R, Horn GT, Mullis KB, Erlich HA. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shendure J, et al. Accurate Multiplex Polony Sequencing of an Evolved Bacterial Genome. Science. 2005;309:1728–1732. doi: 10.1126/science.1117389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landegren U, Kaiser R, Sanders J, Hood L. A ligase-mediated gene detection technique. Science. 1988;241:1077–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.3413476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong AK, Li Z, Jones GS, Russo JJ, Ju J. Combinato-rial fluorescence energy transfer tags for multiplex biological assays. Nature biotechnology. 2001;19:756–759. doi: 10.1038/90810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Botstein D, White RL, Skolnick M, Davis RW. Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. American journal of human genetics. 1980;32:314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall JG, Eis PS, Law SM, Reynaldo LP, Prudent JR, Marshall DJ, Allawi HT, et al. Sensitive detection of DNA polymorphisms by the serial invasive signal amplification reaction. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:8272–8277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140225597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Y, Karalkar NB, Kool ET. Nonenzymatic autoligation in direct three-color detection of RNA and DNA point mutations. Nature biotechnology. 2001;19:148–152. doi: 10.1038/84414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossmann TN, Seitz O. Nucleic acid templated reactions: consequences of probe reactivity and readout strategy for amplified signaling and sequence selectivity. Chemistry-A European Journal. 2009;15:6723–6730. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh SK, Koshkin AA, Wengel J, Nielsen P. LNA (locked nucleic acids): synthesis and high-affinity nucleic acid recognition. Chemical communications. 1998;4:455–456. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egholm M, Buchardt O, Nielsen PE, Berg RH. Peptide nucleic acids (PNA). Oligonucleotide analogs with an achiral peptide backbone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:1895–1897. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simeonov A, Nikiforov TT. Single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping using short, fluorescently labeled locked nucleic acid (LNA) probes and fluorescence polarization detection. Nucleic acids research. 2002;30:e91–e91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Komiyama M, Ye S, Liang X, Yamamoto Y, Tomita T, Zhou J-M, Aburatani H. PNA for one-base differentiating protection of DNA from nuclease and its use for SNPs detection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:3758–3762. doi: 10.1021/ja0295220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tyagi S, Kramer FR. Molecular beacons: probes that fluoresce upon hybridization. Nature Biotechnology. 1996;14:303–308. doi: 10.1038/nbt0396-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang DY, Chen SX, Yin P. Optimizing the specificity of nucleic acid hybridization. Nature Chemistry. 2012;4:208–214. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo Z, Liu Q, Smith LM. Enhanced discrimination of single nucleotide polymorphisms by artificial mismatch hybridization. Nature biotechnology. 1997;15:331–335. doi: 10.1038/nbt0497-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Severinov K, Soushko M, Goldfarb A, Nikiforov V. rifampicin Region Revisited. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:14820–14825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Telenti A, et al. Detection of rifampicin-resistance mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lancet. 1993;341:648–650. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90417-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson BJ, Camien MN, Warner RC. Kinetics of branch migration in double-stranded DNA. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 1976;73:2299–2303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.7.2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panyutin IG, Hsieh P. The kinetics of spontaneous DNA branch migration. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 1994;91:2021–2025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang DY, Winfree E. Control of DNA Strand Displacement Kinetics Using Toehold Exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17303–17314. doi: 10.1021/ja906987s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panyutin IG, Hsieh P. Formation of a single base mismatch impedes spontaenous DNA branch migration. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;230:413–424. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang DY, Seelig G. Dynamic DNA nanotechnology using strand displacement reactions. Nature Chemistry. 2011;3:103–114. doi: 10.1038/nchem.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seelig G, Soloveichik D, Zhang DY, Winfree E. Enzyme-free nucleic acid logic circuits. Science. 2006;314:1585–1588. doi: 10.1126/science.1132493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang DY, Turberfield AJ, Yurke B, Winfree E. Engineering entropy-driven reactions and networks catalyzed by DNA. Science. 2007;318:1121–1125. doi: 10.1126/science.1148532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soloveichik D, Seelig G, Winfree E. DNA as a universal substrate for chemical kinetics. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2010;107:5393–5398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909380107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang DY, Winfree E. Robustness and modularity properties of a non-covalent DNA catalytic reaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4182–4197. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qian L, Winfree E. Scaling up digital circuit computation with DNA strand displacement cascades. Science. 2011;332:1196–1201. doi: 10.1126/science.1200520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nandagopal N, Elowitz MB. Synthetic biology: integrated gene circuits. Science. 2011;333:1244–1248. doi: 10.1126/science.1207084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Purnick PEM, Weiss R. The second wave of synthetic biology: from modules to systems. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:410–422. doi: 10.1038/nrm2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bunka DHJ, Platonova O, Stockley PG. Development of aptamer therapeutics. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2010;10:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.SantaLucia J, Hicks D. The Thermodynamics of DNA Structural Motifs. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 2004;33:415–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.141800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marras SA, Kramer FR, Tyagi S. Efficiencies of fluorescence resonance energy transfer and contact-mediated quenching in oligonucleotide probes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30:e122. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnf121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biswas I, Yamamoto A, Hsieh P. Branch migration through DNA sequence heterology. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;279:795–806. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lishanski A. Screening for single-nucleotide polymorphisms using branch migration inhibition in PCR-amplified DNA. Clinical Chemistry. 2000;46:1464–1470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang Q, et al. Allele-specific Holliday junction formation: a new mechanism of allelic discrimination for SNP scoring. Genome Research. 2003;13:1754–1764. doi: 10.1101/gr.997703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu YP, Behr MA, Small PM, Kurn N. Genotypic determination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis antibiotic resistance using a novel mutation detection method, the branch migration inhibition M. tuberculosis antibiotic resistance test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000;38:3656–3662. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.10.3656-3662.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Browning SR, Browning BL. Haplotype phasing: existing methods and new developments. Nat. Rev. Genetics. 2011;12:703–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McNerney R, Daley P. Towards a point-of-care test for active tuberculosis: obstacles and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:204–213. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niemz A, Ferguson TM, Boyle DS. Point-of-care nucleic acid testing for infectious diseases. Trends in biotechnology. 2011;29:240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Piatek AS, et al. Molecular beacon sequence analysis for detecting drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:359–363. doi: 10.1038/nbt0498-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boehme CC, et al. Rapid Molecular Detection of Tuberculosis and rifampin Resistance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiao Y, Plakos KJI, Lou X, White RJ, Qian J, Plaxco KW, Soh HT. Fluorescence detection of single-nucleotide polymorphisms with a single, self-complementary, triple-stem DNA probe. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2009;48:4354–4358. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tyagi S. Imaging intracellular RNA distribution and dynamics in living cells. Nature Methods. 2009;6:331–338. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manganelli R, Tyagi S, Smith I. Real-time PCR using molecular beacons. Methods Mol. Med. 2001;54:295–310. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-147-7:295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seelig G, Yurke B, Winfree E. Catalyzed relaxation of a metastable DNA fuel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12211–12220. doi: 10.1021/ja0635635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao Y, Wolf LK, Georgiadis RM. Secondary structure effects on DNA hybridization kinetics: a solution versus surface comparison. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:3370–3377. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J, Finney RP, Clifford RJ, Derr LK, Buetow KH. Genomics. 2005;85:297308. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.