Abstract

PYR1/PYL/RCAR family proteins (PYLs) are well-characterized abscisic acid (ABA) receptors. Among the 14 PYL members in Arabidopsis thaliana, PYL13 is ABA irresponsive and its function has remained elusive. Here, we show that PYL13 selectively inhibits the phosphatase activity of PP2CA independent of ABA. The crystal structure of PYL13-PP2CA complex, which was determined at 2.4 Å resolution, elucidates the molecular basis for the specific recognition between PP2CA and PYL13. In addition to the canonical interactions between PYLs and PP2Cs, an extra interface is identified involving an element in the vicinity of a previously uncharacterized CCCH zinc-finger (ZF) motif in PP2CA. Sequence blast identified another 56 ZF-containing PP2Cs, all of which are from plants. The structure also reveals the molecular determinants for the ABA irresponsiveness of PYL13. Finally, biochemical analysis suggests that PYL13 may hetero-oligomerize with PYL10. These two PYLs antagonize each other in their respective ABA-independent inhibitions of PP2Cs. The biochemical and structural studies provide important insights into the function of PYL13 in the stress response of plant and set up a foundation for future biotechnological applications of PYL13.

Keywords: PYL13, PP2CA, PYL10, zinc finger, abscisic acid, ABA signaling

Introduction

Abscisic acid (ABA) is an essential phytohormone that protects plants against biotic and abiotic stress1,2,3,4. Genetic and biochemical characterizations identified an ABA signaling pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana (A. thaliana) involving the ABA receptor PYR1/PYL/RCAR family of proteins (hereafter referred to as PYLs for simplicity), the negative regulator Clade A protein phosphatases type 2C (PP2Cs), the positive player Class III SNF1-related protein kinases 2 (SnRK2s), SnRK2.2/2.3/2.6, and the ABA-responsive element binding factors (ABFs) (Figure 1A)5,6,7,8. ABFs are activated through phosphorylation by auto-phosphorylated SnRK2s. The auto-activation and kinase activity of SnRK2s are inhibited by PP2Cs through both physical interactions and dephosphorylation of key residues9,10. PP2Cs are inhibited by PYLs in the presence of ABA. PYLs contain a ligand-binding pocket whose entrance is surrounded by four conserved loops, CL1-CL411. Upon ABA binding, PYLs, particularly the CL2 loop, undergo conformational rearrangements that lead to the formation of PYL-PP2C heterodimer and inhibition of the phosphatase activities of PP2Cs, thus relieving PP2C-mediated inhibition of SnRK2s11,12.

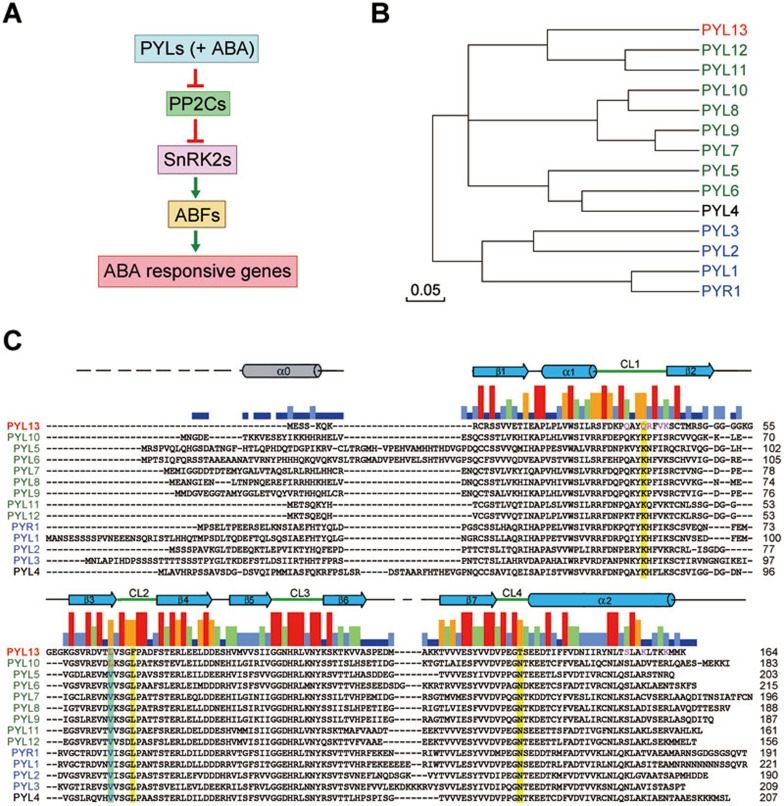

Figure 1.

PYL13 is the only PYL protein that is irresponsive to ABA in A. thaliana. (A) A simplified schematic diagram of PYL-mediated ABA signaling pathway. “PP2Cs” refers to Clade A PP2Cs and “SnRK2” for SnRK2.6/2.3/2.2. “ABFs” stands for ABA-responsive element (ABRE)-binding factors. A number of PYLs, exemplified by PYL10, may inhibit PP2Cs in the absence of ABA. Therefore “ABA” is bracketed. (B) Phylogenetic tree of the 14 PYLs in A. thaliana. The members colored green are able to inhibit PP2Cs in the absence of ABA. The ones colored blue are strictly ABA-dependent PP2C inhibitors. PYL4 exists as a monomer, but inhibits the tested PP2Cs only in the presence of ABA6,13. (C) Sequence alignment of the 14 PYLs in A. thaliana. The secondary elements are indicated above the sequences. Note that the N-terminal Helix α0 is missing in PYLs 11-13. The sequence consensus strength is represented by the colored bars between the secondary elements and sequences. The residues that mediate the interaction between PYL13 and PP2CA are colored magenta. The residues that are invariant in all the PYLs except PYL13 are shadowed yellow. The residues that are unique to PYL13 and PYL10 are shadowed cyan. The alignment was done with ClustalW.

While the PYL members in A. thaliana play a redundant role in ABA perception6, they also exhibit distinct properties in the oligomerization status as well as ABA sensitivity. PYR1 and PYLs 1-3 are obligatory ABA-dependent inhibitors of PP2Cs, among which PYR1, PYL1 and PYL2 are constitutive dimers, whereas PYL3 may be at a faster equilibrium between dimer and monomer13. A number of PYLs, exemplified by PYL10, exist in monomeric form and inhibit the phosphatase activity of PP2Cs, even in the absence of ABA. Nevertheless, they are still subject to regulation by ABA, because the complete inhibition of PP2Cs can be achieved by these PYLs at much lower concentrations when ABA is added13 (Figure 1B).

Among the 14 PYLs in A. thaliana, PYL13 is unique. It is the only one that is irresponsive to ABA. Sequence analysis reveals that a conserved Lys residue that is essential for ABA coordination in ABA-responsive PYLs is replaced by Gln in PYL13 (Figure 1C). Corroborating this analysis, mutation of the corresponding Lys to Gln in PYL2 completely abolished its affinity with ABA11. Ever since the discovery of PYLs being ABA receptors, extensive studies have been committed to the mechanistic elucidation of various PYL members11,12,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23; however, the function of PYL13 has remained elusive. In this report, we combine structural biology and biochemical approaches to systematically investigate the function and mechanism of PYL13.

Results

PYL13 selectively inhibits PP2CA independent of ABA

A serious technical obstacle to the in vitro characterizations of PYL13 came from the poor solution behavior of the recombinant protein overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Despite a reasonable expression level, the protein was found almost entirely in precipitant. More than 20 PYL13 constructs with various boundaries were generated, but none exhibited improved stability. Sequence comparison shows that PYL13 lacks the N-terminal segment corresponding to Helix α0 in other PYLs (Figure 1C). Speculating that the absence of the N-terminal helix might underlie the instability of recombinant PYL13 proteins, we engineered a number of chimeric PYL13; each containing an extra N-terminal sequence adopted from PYR1, PYL1, PYL2 and PYL10. None of these chimeras gave rise to proteins that are suitable for biochemical or structural characterizations. We also tested a variety of buffer conditions including a systematic screening for pH, ionic strength and additives such as glycerol and non-ionic detergents, under different temperatures. Unfortunately, PYL13 defied all kinds of maneuver.

The breakthrough was finally made when the C-terminal 6×His-tagged full-length (FL) PYL13 was co-expressed with Clade A PP2Cs. Soluble PYL13 was obtained in the presence of PP2Cs and the complex survived purification through Ni-NTA affinity resin. However, depending on the PP2Cs used for co-expression, the protein complexes exhibited distinct stabilities. In the presence of ABI1, HAB1, or HAB2, proteins gradually precipitated after purification through Ni-NTA resin, both at 22 °C and 4 °C. SDS-PAGE analysis confirmed that PYL13 was the major precipitant. Nevertheless, when the supernatants were applied to size exclusion chromatography (SEC), PYL13 co-migrated with these PP2Cs despite a disproportional stoichiometry between PYL13 and different PP2Cs (Figure 2A, top 3 rows). In contrast, the complex between PYL13 and PP2CA showed excellent behavior. The protein complex remains soluble throughout the purification procedure including affinity column, ion exchange chromatography, and SEC. The elution position of PYL13-PP2CA complex is similar to that of the reported PYL-PP2C complexes whose structures were obtained (Figure 2A, bottom row)11,13. These observations suggest that PYL13 may form a more stable complex with PP2CA than with the other PP2Cs.

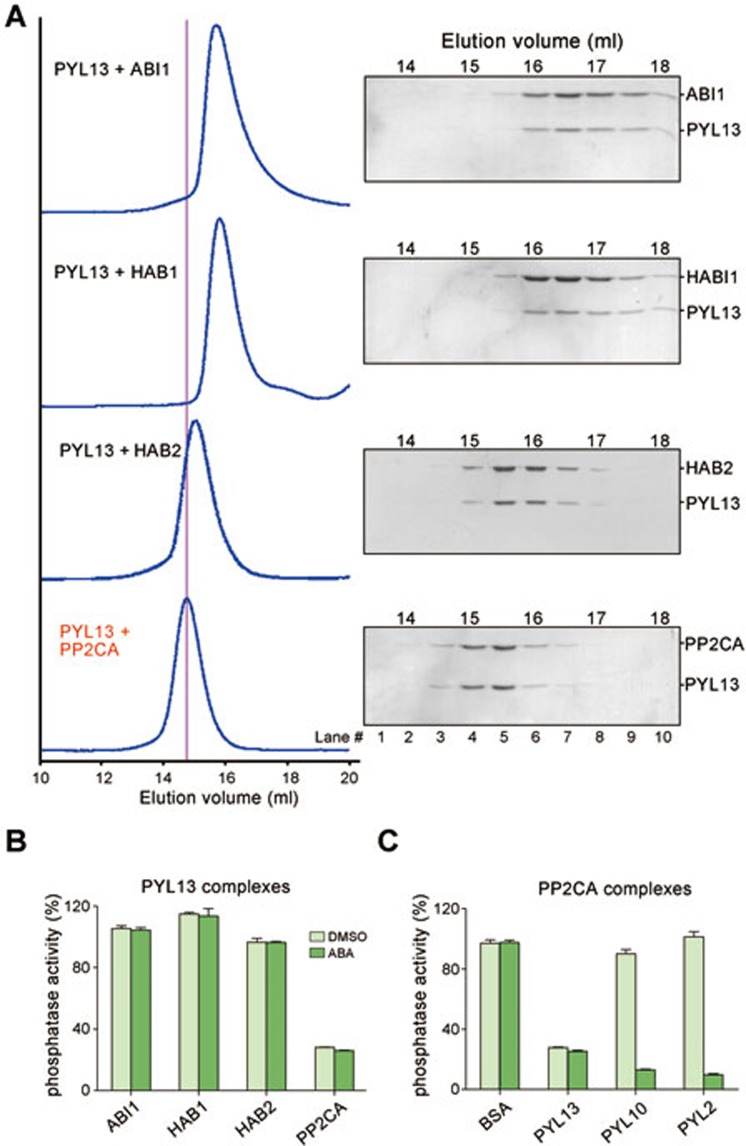

Figure 2.

PYL13 specifically binds to and inhibits PP2CA independent of ABA. (A) Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) analyses of the complexes between PYL13 and ABI1, HAB1, HAB2, and PP2CA. The indicated fractions of SEC eluents were applied to SDS-PAGE followed by coomassie-blue staining. The peak position of the PYL13-PP2CA complex is indicated by the magenta line. (B) PYL13 specifically inhibits PP2CA independent of ABA. The details of the experiments are described in Materials and Methods. The readout of the reactions without phosphatase was set as the baseline. The phosphatase activity of the indicated PYL13-PP2C complex is normalized against that of the corresponding PP2C at the same molar concentration. The concentrations of all the PYL13-PP2C complexes are adjusted to 0.2 μM for assays. ABA was added with a final concentration of 2 μM. All the experiments are independently performed for at least three times. The error bars represent SD. (C) PP2CA is specifically inhibited by PYL13 in the absence of ABA. PYL2 and PYL10 rely on ABA to inhibit PP2CA. Notably, PYL10 is a potent ABA-independent inhibitor of ABI1, HAB1, and HAB2, but not PP2CA13.

We then tested the inhibitory effect of PYL13 on several PP2Cs (Figure 2B). A titration of PYL13 concentration was impractical because PYL13 cannot be isolated on its own. Instead, the phosphatase activities of the PYL13-PP2C complexes were compared to those of the corresponding PP2Cs with all the protein concentrations adjusted to approximately 0.2 μM. The phosphatase activities of PYL13-PP2C complexes were normalized against those of the corresponding PP2Cs in the presence of 0.2 μM BSA. Although PYL13 can form complex with ABI1, HAB1, and HAB2, it showed little or no inhibition to these three PP2Cs. In contrast, more than 70% of the phosphatase activity of PP2CA was inhibited by PYL13 at a stoichiometric ratio of 1:1. As expected, ABA had no effect on PYL13 (Figure 2B).

The observation that PYL13 is an efficient, ABA-independent inhibitor for PP2CA is interesting, because the previous biochemical examinations suggested that PP2CA is fairly resistant to ABA-independent inhibitions by PYLs13. Indeed, when added at a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio, PYL13 effectively inhibits PP2CA, whereas PYL10 and PYL2 showed little or no inhibition in the absence of ABA (Figure 2C). These observations indicate that PYL13 is a specific ABA-independent inhibitor of PP2CA.

Crystal structure of PYL13-PP2CA complex

We next sought to determine the crystal structure of PYL13-PP2CA complex to reveal the molecular basis underlying their specific recognition. Crystals of the complex between FL PYL13 and PP2CA (residues 71-399) were obtained in the space group P3. The structure was solved with a molecular replacement using the structure of PYL10-HAB1 (PDB accession code 3RT0)13 as a search model and was refined to a 2.4 Å resolution (Figure 3A and Supplementary information, Table S1). The overall structure of the PYL13-PP2CA complex resembles those of the previously reported PYL-PP2C complexes. The two canonical interfaces between PYLs and PP2Cs are conserved in PYL13-PP2CA complex, one involving the CL2 loop of PYL13 and the catalytic site of PP2CA, and the other consisting of a hydrophobic pocket formed by the CL3 and CL4 loops of PYL13 and an invariant Trp in PP2Cs (Trp280 of PP2CA) (Figure 3A)11,12,14.

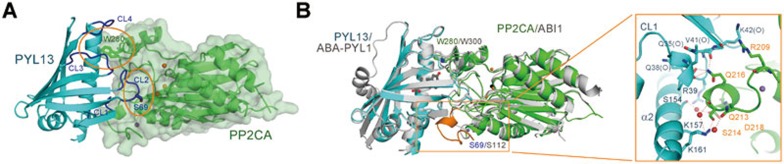

Figure 3.

Crystal structure of the PYL13-PP2CA complex. (A) Overall structure of the complex at 2.4 Å resolution. The canonical PYL-PP2C interfaces are highlighted with orange circles. The conserved loops CL1-CL4 of PYL13 are colored dark blue. The three metal ions at the active site of PP2CA are shown as orange spheres. (B) Structural comparison between the complexes of PYL13-PP2CA (cyan for PYL13 and green for PP2CA) and ABA-PYL1-ABI1 (grey) revealed an extra interface involving a unique structural element (orange) in PP2CA. Inset: The extra interface between PYL13 and PP2CA is mediated through direct and water-mediated H-bonds. The structural element colored orange in the left panel is now shown in green, with the key residues labeled orange. The water molecules are shown as red spheres. The H-bonds are represented by red dashes. All structure figures were prepared with PyMol35

Despite the reminiscence to the reported PYL-PP2C complex structures, an extra interface is observed between PYL13 and PP2CA, which involves CL1 and Helix α2 of PYL13 and a new motif of PP2CA (Figure 3B). This new interface is mainly mediated through direct and water-mediated hydrogen bonds (Figure 3B, inset). The PP2CA-unique motif comprises of a short helix and an extended loop. Notably, the sequence corresponding to this motif is missing in ABI1 and ABI2, and varies in HAB1 and HAB2. In addition, none of the residues that are involved in PYL13 binding, Arg209, Gln213, Ser214, Gln216 and Asp218, are conserved in ABI1/2 or HAB1/2 (Supplementary information, Figure S1). The PYL13 residues whose side groups participate in the new interface, Arg39, Lys157 and Lys161, are not conserved in the PYL family either (Figures 1C and 3B).

A CCCH zinc-finger motif revealed by the PP2CA structure

The PP2CA motif that mediates the new interface between PP2CA and PYL13 was uncharacterized in other PP2Cs24 (Figure 4A and Supplementary information, Figure S1). We further scrutinized this unique element. After structural refinement, extra electron density was found at a position surrounded by the loop of the motif. The electron density appears to be contiguous with four adjacent amino acids: Cys146, His148, Cys208, and Cys210. This structural feature represents a canonical zinc-finger (ZF) motif. Therefore, the extra electron density is likely of a zinc ion (Figure 4A, inset), whose presence is verified by inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) analysis (Supplementary information, Table S2). Point mutations of the Cys residues of the ZF resulted in compromised protein stability and significantly compromised phosphatase activity of PP2CA, indicating a critical role of the ZF for the structural integrity and function of PP2CA (Figure 4B).

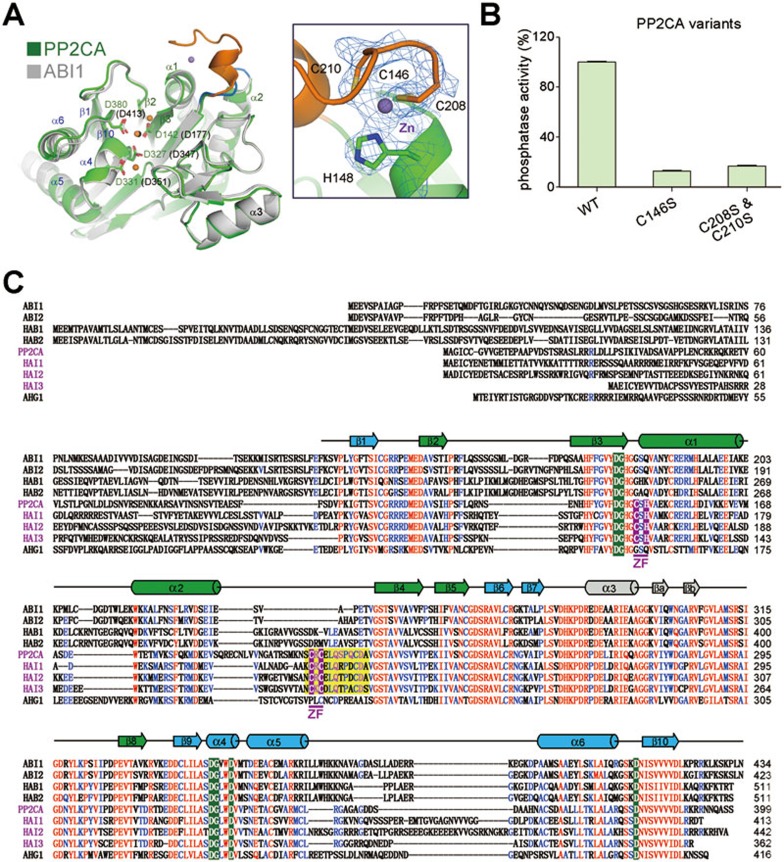

Figure 4.

The structure of PP2CA revealed an uncharacterized CCCH zinc-finger motif. (A) The extra motif in PP2CA is a CCCH zinc-finger motif. Left panel: Structure comparison between PP2CA and ABI1 reveals a new motif in PP2CA. Three metal ions (orange) are observed at the active site of PP2CA, but only one (black) is seen in the PYL1-bound ABI1 (PDB code: 3KDJ). The extra structural motif in PP2CA is highlighted in orange. Right panel: the 2Fo-Fc electron density (blue mesh) of the metal and the surrounding four residues is contoured at 1.5 σ. The zinc ion is coordinated by three Cys and one His residues. (B) Point mutations of the zinc coordinating residues lead to significantly crippled phosphatase activities. The details for the phosphatase assay are described in Materials and Methods. (C) Sequence alignment of the nine members of Clade A PP2Cs in A. thaliana revealed the zinc-finger motif (shaded in purple) conserved in HAI1/2/3 in addition to PP2CA. Invariant and conserved residues are colored red and blue, respectively. The active site residues are shaded green. The secondary elements of the core structure of PP2Cs are shown above the sequences.

Notably, the ZF is missing in ABI1, ABI2, HAB1, HAB2, and AHG1, but conserved in the recently characterized Clade A PP2Cs HAI1, HAI2, and HAI3 (Highly ABA-induced) (Figure 4C and Supplementary information, Figure S2). ZF has never been reported in any protein phosphatase. We thus attempted to search for more ZF-containing PP2Cs through sequence analysis. BLAST against the sequenced genomes using the sequence of PP2CA as query object identified another 56 PP2Cs that contain the ZF (Supplementary information, Figure S3). Interestingly, all of these PP2Cs, mostly uncharacterized, are from plants.

Molecular basis for the ABA irresponsiveness of PYL13

The structure of PYL13-PP2CA provides a good opportunity to examine the molecular basis for the ABA irresponsiveness of PYL13 when it is difficult to obtain the crystal structure of PYL13 alone. The answer becomes immediately evident when the structure of PYL13 was superimposed to that of the ABA-bound PYL1 (Figure 5A). Binding of ABA requires a conserved Lys that is located on CL1 and buried in the pocket of PYLs to anchor the carboxylate group of ABA (Figure 5A, lower panel). In PYL13, Lys is replaced by Gln at the corresponding position (Gln38), hence losing the essential anchorage point for ABA. Intriguingly, the ABA response cannot be completely restored when Gln38 of PYL13 is changed to a Lys residue (Supplementary information, Figure S4), suggesting the existence of extra element(s) that prevents PYL13 from responding to ABA.

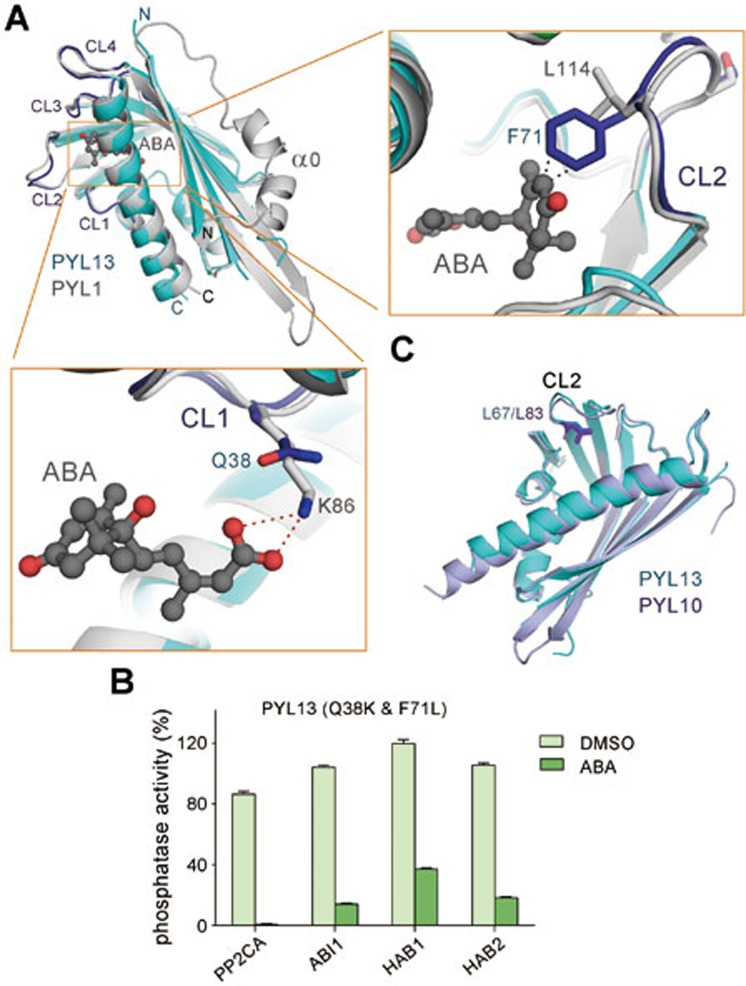

Figure 5.

Molecular basis underlying the ABA irresponsiveness of PYL13. (A) ABA cannot fit into the pocket of PYL13. The structure of PP2CA-bound PYL13 is superimposed to that of ABA-bound PYL1 (PDB code: 3KDJ). Lower panel: PYL13 lacks the Lys residue that is essential for ABA-responsive PYLs in the coordination of the carboxylate group of ABA. Right panel: Phe71, which corresponds to a Leu in all the other 13 PYLs, would collide with ABA if an ABA molecule was placed into the pocket of PYL13. (B) Double mutation, Q38K/Phe71L, converted PYL13 into an ABA-responsive receptor. The experiments were performed with the identical protocol as in Figure 2B. (C) A structural feature shared by PYL10 and PYL13 that may underlie the ABA-independent inhibition of PP2Cs. The starting residue of CL2 is Leu in PYL10 and PYL13, but Val in all the other PYLs (Figure 1C). This feature was previously shown to be one structural determinant underlying ABA-independent inhibition of PP2Cs13.

Further examination of the structural superimposition showed that an invariant Leu residue that is located on the CL2 loop in all the other thirteen PYLs is replaced by a Phe residue in PYL13 (Phe71) (Figures 1C and 5A). There would be a steric clash between the aromatic ring of Phe71 and the hydrophobic moiety of ABA if an ABA molecule was placed into the PYL pocket (Figure 5A, right panel). While the PYL13 mutant containing F71L showed little change in the ABA response (Supplementary information, Figure S4), the double point mutation, Q38K/F71L, converted PYL13 into an ABA-dependent inhibitor to all the tested PP2Cs, including PP2CA, ABI1, HAB1, and HAB2 (Figure 5B and Supplementary information, Figure S4). Therefore, the lack of the positively charged Lys within the pocket and the replacement of a CL2 residue Leu to Phe account for the ABA irresponsiveness of PYL13.

PYL13 and PYL10 antagonize each other in the ABA-independent inhibition of PP2Cs

It is noteworthy that PYL13 inhibits more than 70% of the phosphatase activity of PP2CA in the absence of ABA when the stoichiometric ratio of the two proteins is approximately 1:1, an effect similar to PYL10-mediated inhibition of ABI1 and HAB1, and much better than the other ABA-independent PYLs13. Our previous studies identified two molecular determinants for PYLs to be ABA-independent inhibitor of PP2Cs, being a monomer and having a bulky hydrophobic residue at a position that demarcates CL2 and the preceding β-strand13. Notably, PYL13 and PYL10 are the only two PYLs that contain a Leu instead of a Val as the starting residue of CL2 (Figures 1C and 5C). This structural feature may in part facilitate the closure of CL2 loop, which is required for the complex formation between PYLs and PP2Cs.

It is impractical to study the oligomerization state of PYL13 because of its poor solution behavior. We reasoned that PYL13 may be able to hetero-dimerize with other monomeric PYLs if it is a monomer. To test this speculation, we co-expressed PYL13 with PYL10 to examine whether nickel-NTA resin might be able to pull down the untagged PYL10 through the 6×His-tagged PYL13. Unfortunately, PYL13 remained insoluble. Nevertheless, a chimeric protein, PYL13*, which has the N-terminal Helix α0 of PYL10 (residues 1-24) fused to the FL PYL13 was successfully co-eluted with PYL10. Intriguingly, the PYL13*-PYL10 complex was co-eluted on SEC at a position corresponding to an oligomer of molecular weight much larger than a dimer (Supplementary information, Figure S5). Helix α0 is not involved in the dimeric interface of PYLs, therefore the introduction of the extra N-terminal fragment to PYL13 should not affect the interface between PYL13 and PYL10. Corroborating this notion, another chimeric protein with the N-terminal fragment of PYL2 (residues 1-26) fused to PYL13 gave rise to identical results.

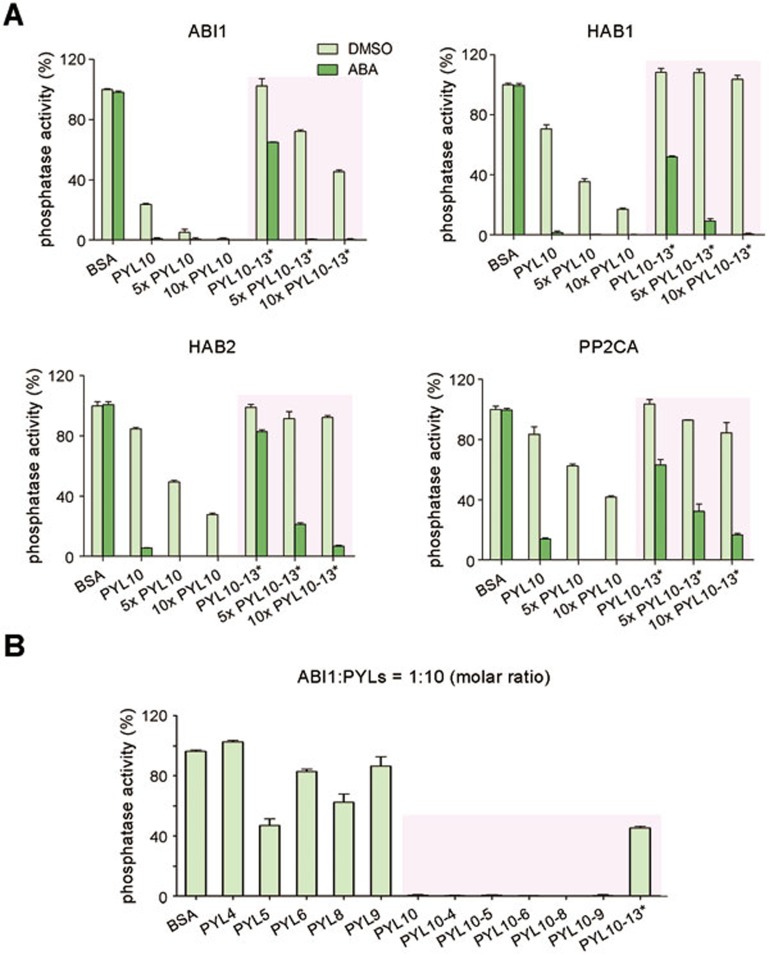

It is also noteworthy that PYL10 failed to form complex with PYLs 4-9 (except the untested PYL7), indicating a specific interaction between PYL10 and PYL13. We then set out to inspect the functional consequence of the hetero-oligomerization of PYL10 and PYL13 by measuring their inhibition of the phosphatase activities of PP2Cs both in the presence and absence of ABA. The ABA-independent inhibition of PP2CA by PYL13* was seriously compromised in the presence of PYL10 (Figure 6A). On the other hand, whereas PYL10 can inhibit ABI1, HAB1, and HAB2, and to a lesser extent, PP2CA, the PYL10-PYL13* complex lost the ABA-independent inhibition of these PP2Cs (Figure 6A). Notably, none of the other monomeric PYLs was able to antagonize PYL10 on its ABA-independent inhibition of ABI1 (Figure 6B). Therefore, PYL10 and PYL13 specifically antagonize each other on their respective ABA-independent inhibitions of PP2Cs. It is also noteworthy that this antagonism is subject to the regulation by ABA, as addition of ABA restored the inhibition of PP2Cs by PYL10 (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

PYL10 and PYL13 antagonize each other on the ABA-independent inhibition of PP2Cs. (A) The PYL10-PYL13 complex is almost unable to inhibit PP2Cs in the absence of ABA. The phosphatase activities of 0.2 μM PP2Cs were examined in the presence of PYL10 or PYL10-PYL13 at concentrations of 0.2, 1 and 2 μM, respectively. The conditions in which both PYL10 and PYL13 were added are highlighted with pink shade. (B) Only PYL13*, but not the other monomeric PYLs, can antagonize PYL10 on its ABA-independent inhibition of ABI1. PYL13* refers to the chimeric protein with the N-terminal fragment of PYL10 (residues 1-24) fused to PYL13. PYLs 4-9 (except PYL7) were purified to homogeneity and incubated with PYL10 at a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio before the assays. PYL13 was co-purified with PYL10 (Supplementary information, Figure S5). The phosphatase activities of 0.2 μM ABI1 were examined in the presence of 2 μM PYL proteins, as indicated.

Discussion

There are 14 PYL members in A. thaliana. Despite their seemingly redundant actions, increasing studies revealed the divergence of these proteins in ABA signaling6,7,13,17,18. For example, PYR1, PYL1, and PYL3, but not PYL2 and PYL4, are sensitive to an ABA agonist pyrabactin6,17,18,25. Structural comparisons revealed the determining effect of a single amino acid variation on the pyrabactin perception by PYLs17,18. Several studies suggested that some of the PYLs, exemplified by PYL10, are able to inhibit PP2Cs in the absence of ABA6,7,13,15. Nevertheless, all these PYLs are able to respond to the ABA. In contrast, PYL13 is the only member that is completely irresponsive to ABA. The structural and biochemical analyses presented here reveal the function and molecular mechanism of PYL13 and may help to further delineate the PYL family proteins.

Our previous biochemical examinations uncovered a subclass of PYLs, consisting of PYLs 4-10 (excluding the uncharacterized PYL7), that exist as a monomer in solution13. These PYLs, exemplified by PYL10, exhibit the ability of ABA-independent PP2C inhibition. It was shown that the dimeric formation of PYLs is a negative factor for ABA perception because it competes with the subsequent heterodimeric formation with PP2Cs13,15,25. The existence of monomeric PYLs naturally leads to the question of whether they can heterodimerize and thereby antagonize each other. Our preliminary biochemical analysis showed that PYL10 and PYL13, the two most potent ABA-independent inhibitors of PP2Cs, can antagonize each other. Given that the other monomeric PYLs only have weak inhibition of PP2Cs in the absence of ABA13, the antagonism of PYL10 and PYL13 may be particularly important. The mutual antagonism of PYL10 and PYL13 is subject to regulation by ABA. Therefore, the distinct binding affinities of PYL homo- or hetero-oligomers and of the PYL-PP2C complexes may constitute a fine-tuned, quantitative, and dynamic regulatory system that ensures the normal growth, development, and stress response in the absence of ABA signal.

PP2CA (also known as AHG3 for ABA-Hypersensitive Germination3) is a negative regulator of ABA signaling during germination26. It was also shown that PP2CA inactivates CIPK (CBL-interacting protein kinases)-dependent AKT1 (Arabidopsis K+ transporter 1)27. Sequence comparison of the Clade A PP2Cs from Arabidopsis suggested that PP2CA is closely related to HAI1/2/3 (Figure 4C and Supplementary information, Figures S1 and S2). As the ZF of PP2CA is involved in the extra interface with PYL13, we speculated that PYL13 may also target HAI1/2/3. However, all the 3 proteins failed recombinant expression, hence hindering the potential in vitro biochemical characterizations. It was recently reported that the HAI2/3 interact with PYLs 7-10 in the absence of ABA, while HAI1 shows little affinity with PYLs28. It is possible that HAI2/3 may be subject to inhibition by PYL13 independent of ABA.

Zinc finger is a common motif that has been found in proteins associated with a variety of functions, exemplified by the DNA-binding proteins. In plants, Tandem CCCH ZF proteins are involved in growth and stress response29. However, it is for the first time that a ZF is ever identified in protein phosphatases. Therefore, the structure of PP2CA reported here provides an important clue to the further characterization of ZF-containing PP2Cs.

In sum, we combine structural biology and biochemical characterizations to investigate the function and mechanism of PYL13. We discovered that PYL13, independent of ABA, selectively inhibits PP2CA. The crystal structure of the PYL13-PP2CA complex determined at 2.4 Å resolution reveals a unique interface in addition to the canonical PYL-PP2CA interactions. Interestingly, examination of the new interface reveals a previously uncharacterized CCCH ZF motif in PP2CA. Furthermore, structural examination of PYL13 elucidates the molecular basis underlying its irresponsiveness to ABA. Structure-guided mutations successfully converted PYL13 to an ABA-responsive receptor. We also showed that PYL13 and PYL10 antagonize each other on the ABA-independent inhibition of PP2Cs. The studies reported here extend our understanding of the delicately and dynamically regulated ABA signaling pathway through PYLs and PP2Cs, and may facilitate the biotechnological applications of PYL13.

Materials and Methods

Protein preparation

All PYR/PYLs homologs, ABI1 (AT4G26080), HAB1 (AT1G72770), HAB2 (AT1G17550), and PP2CA (AT3G11410) were subcloned from the A. thaliana cDNA library using standard PCR-based protocol. All mutants of PYLs were generated with two-step PCR and verified by plasmid sequencing. All the proteins were purified according to the protocol described previously11. To obtain individual proteins for activity assays or crystallization, PYLs and PP2Cs were subcloned into pET-15b and overexpressed in E.coli strain BL21(DE3). Protein expression was induced with Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 22 °C for 12 h. The proteins were purified with Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen), followed by anion exchange chromatography (Source-15Q, GE Healthcare) and size exclusion chromatography (SEC, Superdex-200, GE Healthcare). To obtain the complexes of PYL13 with PP2Cs, PYL13 subcloned into vector pET15b and PP2Cs in pBB75, were co-expressed in E.coli strain BL21(DE3) and purified according to the protocol described above.

Crystallization

Prior to crystallization, the 6×His-tag preceding PYL13 was removed by protease digestion. Crystals of the binary complex of FL PYL13 and PP2CA (residues 71-399) were grown at 18 °C using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. The crystals of the complex appeared in the well-buffer containing 100 mM MES pH 6.5, 25% PEG600, 150 mM CaCl2 and 2.7% 2, 5-Hexanediol.

Data collection, structure determination and refinement

The diffraction data were collected at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), integrated and scaled with HKL2000 package30. Further data processing was carried out using programs from the CCP4 suite31.

To determine the complex structure of PYL13-PP2CA, PYL10 and HAB1 extracted from the PYL10-HAB1 complex (PDB code: 3RT0) were selected as the molecular replacement model. The molecular replacements were performed with program PHASER32 and manually model rebuilding and refinement were iteratively performed with COOT33 and PHENIX34. Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Supplementary information, Table S1.

Phosphatase activity assay

The proteins were purified by nickel-NTA affinity resin followed by buffer change through desalting column. To prevent protein precipitation, the assays were performed immediately after the proteins were quantified by both BioRad assay (BIO-RAD) and coomassie-blue staining following SDS-PAGE. The phosphatase activity was measured by the Ser/Thr phosphatase assay system (Promega). The protocol of phosphatase activity assay was described previously with some modifications11. Each reaction was performed in a 50 μl reaction volume. The concentrations of the phosphatases were adjusted so that the readout is within the linear range of the absorbance measurement. The concentrations of PYL proteins were adjusted so as to match the molar ratios indicated in the manuscript. ABA was added at the indicated concentration, if required. After incubation and equilibration in reaction buffer at 30 °C for 18 min (50 mM imidazole, pH 7.2, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA and 0.1 mg/ml BSA), peptide substrate (supplied with the Promega kit) was added and allowed to react for 22 min, the reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl molybdate dye. The reactions were allowed for 15 min at room temperature before the absorbance at 630 nm was measured. The readout of the negative control, i.e., the reaction without phosphatase, was set as the baseline and the value was subtracted from all the assays. The positive controls, i.e., the reactions with addition of BSA at the same molecular concentration as the indicated PYLs, were set as 100%. All the assay data, subtracted with the baseline value, were normalized against the positive controls at the corresponding concentrations. Unless otherwise indicated, the concentrations of the proteins were adjusted to 0.2 μM for the assays. All the data are means ± SD from at least three independent experiments.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC)

The SEC analyses were performed with a SD200 (Superdex-200 HR10/30, GE Healthcare) in the buffer containing 25 mM Tris, pH 8.0 and 150 mM NaCl. To examine the interactions between the indicated proteins, 400 μl proteins or protein mixtures were applied to SD200. In the test requiring ABA, 0.4 mM ligand was incubated with the proteins before injection.

ICP-AES

ICP-AES (VARIAN ICP 710) was employed to measure the metal contents in PP2CA-PYL13 complex and PYL5. The protein samples were prepared in the buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl. The concentrations of Zn, Mg, and Mn were quantified, respectively.

Accession number

The atomic coordinates of PYL13-PP2CA complex are deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession number 4N0G.

Acknowledgments

We thank J He and S Huang at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) for assistance. This work was supported by funds from the Ministry of Science and Technology (2011CB910501), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31125009 and 91017011), and Tsinghua University. The research of Nieng Yan was supported in part by an International Early Career Scientist grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Sequence comparison of five Clade A PP2Cs from Arabidopsis thaliana.

Sequence comparison of PP2CA with HAI1/2/3.

Evolutionary relationships of ZF (zinc-finger motif)-containing PP2Cs.

Structure-guided point mutations converted PYL13 into an ABA receptor.

PYL13 and PYL10 form hetero-complex.

Statistics of data collection and refinement

ICP-AES (Inductively Coupled Plasma-Atomic Emission Spectrometry) analysis of the metal contents in PP2CA-PYL13 complex and PYL5

References

- Fedoroff NV. Cross-talk in abscisic acid signaling. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:re10. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.140.re10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein R, Reeves W, Ariizumi T, Steber C. Molecular aspects of seed dormancy. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:387–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JI, Nambara E. A quick release mechanism for abscisic acid. Cell. 2006;126:1023–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53:247–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.091401.143329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Szostkiewicz I, Korte A, et al. Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science. 2009;324:1064–1068. doi: 10.1126/science.1172408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Fung P, Nishimura N, et al. Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science. 2009;324:1068–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.1173041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H, Chinnusamy V, Rodrigues A. In vitro reconstitution of an abscisic acid signaling pathway. Nature. 2009;462:660–664. doi: 10.1038/nature08599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago J, Rodrigues A, Saez A, et al. Modulation of drought resistance by the abscisic acid receptor PYL5 through inhibition of clade A PP2Cs. Plant J. 2009;60:575–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie T, Ren R, Zhang YY, et al. Molecular mechanism for inhibition of a critical component in the Arabidopsis thaliana abscisic acid signal transduction pathways, SnRK2.6, by protein phosphatase ABI1. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:794–802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.313106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soon FF, Ng LM, Zhou XE, et al. Molecular mimicry regulates ABA signaling by SnRK2 kinases and PP2C phosphatases. Science. 2012;335:85–88. doi: 10.1126/science.1215106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin P, Fan H, Hao Q, et al. Structural insights into the mechanism of abscisic acid signaling by PYL proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1230–1236. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher K, Ng LM, Zhou XE, et al. A gate-latch-lock mechanism for hormone signaling by abscisic acid receptors. Nature. 2009;462:602–608. doi: 10.1038/nature08613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Q, Yin P, Li W, et al. The molecular basis of ABA-independent inhibition of PP2Cs by a subclass of PYL proteins. Mol Cell. 2011;42:662–672. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, Miyakawa T, Sawano Y, et al. Structural basis of abscisic acid signaling. Nature. 2009;462:609–614. doi: 10.1038/nature08583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosquna A, Peterson FC, Park SY, Lozano-Juste J, Volkman BF, Cutler SR. Potent and selective activation of abscisic acid receptors in vivo by mutational stabilization of their agonist-bound conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20838–20843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112838108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimovaara-Dijkstra S, Testerink C, Wang M. Mitogen-activated protein kinase and abscisic acid signal transduction. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2000;27:131–144. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-49166-8_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan XQ, Yin P, Hao Q, Yan CY, Wang JW, Yan NE. Single amino acid alteration between valine and isoleucine determines the distinct pyrabactin selectivity by PYL1 and PYL2. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28953–28958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher K, Xu Y, Ng LM, et al. Identification and mechanism of ABA receptor antagonism. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1102–1108. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SR, Rodriguez PL, Finkelstein RR, Abrams SR. Abscisic acid: emergence of a core signaling network. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:651–679. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher K, Zhou XE, Xu HE. Thirsty plants and beyond: structural mechanisms of abscisic acid perception and signaling. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:722–729. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakawa T, Fujita Y, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Tanokura M. Structure and function of abscisic acid receptors. Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guzman M, Pizzio GA, Antoni R, et al. Arabidopsis PYR/PYL/RCAR receptors play a major role in quantitative regulation of stomatal aperture and transcriptional response to abscisic acid. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2483–2496. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.098574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Wang H, Wu M, Zang J, Wu F, Tian C. Crystal structures of the Arabidopsis thaliana abscisic acid receptor PYL10 and its complex with abscisic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;418:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. Serine/threonine phosphatases: mechanism through structure. Cell. 2009;139:468–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Q, Yin P, Yan C, et al. Functional mechanism of the ABA agonist pyrabactin. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28946–28952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.149005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Nishimura N, Kitahata N, et al. ABA-hypersensitive germination3 encodes a protein phosphatase 2C (AtPP2CA) that strongly regulates abscisic acid signaling during germination among Arabidopsis protein phosphatase 2Cs. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:115–126. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.070128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan WZ, Lee SC, Che YF, Jiang YQ, Luan S. Mechanistic analysis of AKT1 regulation by the CBL-IPK-P2CA interactions. Mol Plant. 2011;4:527–536. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskara GB, Nguyen TT, Verslues PE. Unique drought resistance functions of the highly ABA-induced clade A protein phosphatase 2Cs. Plant Physiol. 2012;160:379–395. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.202408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomeranz M, Finer J, Jang JC. Putative molecular mechanisms underlying tandem CCCH zinc finger protein mediated plant growth, stress, and gene expression responses. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6:647–651. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.5.15105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project N. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography Acta Crystallogr 1994D50760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, et al. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics SystemAvailable at: : http://wwwpymolorg2002 .

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sequence comparison of five Clade A PP2Cs from Arabidopsis thaliana.

Sequence comparison of PP2CA with HAI1/2/3.

Evolutionary relationships of ZF (zinc-finger motif)-containing PP2Cs.

Structure-guided point mutations converted PYL13 into an ABA receptor.

PYL13 and PYL10 form hetero-complex.

Statistics of data collection and refinement

ICP-AES (Inductively Coupled Plasma-Atomic Emission Spectrometry) analysis of the metal contents in PP2CA-PYL13 complex and PYL5