Abstract

MAD2 inhibits the anaphase-promoting complex when chromosomes are unattached to the mitotic spindle. It acts as a tumor suppressor gene because MAD2+/–cells enter anaphase early and display chromosome instability, leading to the formation of lung tumors in mice. Complete MAD2 inactivation has not been identified in human tumors, although partial defects are prevalent. By employing RNA interference in human somatic cells, we found that severe reduction of MAD2 protein levels results in mitotic failure and extensive cell death arising from defective spindle formation, incomplete chromosome condensation, and premature mitotic exit leading to multinucleation. Cyclin B is degraded prematurely in the MAD2 short interfering RNA-treated cells but not in MAD2+/– cells, suggesting an explanation for the spindle failure and mitotic catastrophe in the MAD2 knockdown cells. Thus, anaphase-promoting complex substrates exhibit distinct sensitivities in the presence of different MAD2 doses, which in turn determine MAD2's role as either a tumor suppressor or an essential gene.

The spindle checkpoint monitors the integrity of spindle-kinetochore attachments at prometaphase (1, 2). The presence of a single misaligned chromosome is sufficient to induce a wait anaphase signal executed by the multiprotein mitotic checkpoint complex (3). During checkpoint activation, MAD2 and other checkpoint components form an inhibitory ternary complex with an E3 ligase, the anaphase-promoting complex (APC) and its substrate specific activator, cdc20 (4, 5). After bipolar attachment of all of the chromosomes to the mitotic spindle at metaphase, MAD2 is phosphorylated, and the multiprotein mitotic checkpoint complex-mediated inhibition of APCcdc20 is extinguished, resulting in the ubiquitinylation of multiple substrates such as securin and cyclin B (6). Degradation of these substrates is a requirement for the onset of anaphase.

MAD2 null yeast cells are viable but lose chromosomes at higher rates than wild-type cells due to chromosome missegregation (7). Similarly, Mad2 null mouse embryos missegregate their chromosomes but lose viability after day 6.5 postcoitus, likely due to the critical requirement for the maintenance of normal chromosome numbers during development (8). Notably, Mad2+/– mouse embryonic fibroblasts and the human colon carcinoma cell line, Hct-116, in which we have previously deleted one copy of MAD2 by homologous recombination (herein referred to as Hct-MAD2+/– cells), exhibit enhanced rates of chromosome gains and losses without a loss of viability. Consistent with the aneuploidy identified in Mad2+/– mouse embryonic fibroblasts, Mad2+/– mice are tumor prone (9). Examination of several human tumor types has revealed reduced levels of MAD2 protein expression, consistent with the role that partial reduction of MAD2 protein levels play in the genesis of aneuploidy and tumorigenesis (10–12). However, the existence of MAD2 null cancers has not been reported, raising the possibility that lower MAD2 protein levels might be lethal in human somatic cells, due to mitotic errors other than chromosome missegregation. To formally test this possibility, two short interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotides and a short hairpin targeting a total of three separate MAD2 coding sequences were used to severely reduce MAD2 protein levels (13, 14).

Materials and Methods

Oligonucleotides, Short Hairpins, Retroviral Infections, Plasmids, and Transfections. Oligonucleotides corresponding to the sequences in the MAD2 ORF 5′-AATACGGACTCACCTTGCTTG-3′ (M2.1) and 5′-AAAGTGGTGAGGTCCTGGAAA-3′ (M2.3) were generated by Dharmacon. Negative controls consisting of lamin and a scrambled sequence (5′-CAGTCGCGTTTGCGACTGG-3′) were also synthesized by Dharmacon. Transfections were carried out by using 10 μl of a 10-mmol RNA solution with Oligofectamine according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). The sequence for the short hairpin against MAD2 is 5′-GTGATCAGACAGATCACAGCTACGGTGAC-3′ and the protocol used for generation of the hairpin and infections is fully described elsewhere (15). The sequence 5′-GAGCGTAGACGGACTCCTCCACTACTGAT-3′ identical to murine MAD2 coding sequences not present in humans was used as a negative control. All sequences were subject to blast analysis to ensure no significant homology with other coding regions. For sequential knockdown and plasmid transfections, a D-box mutant of cyclin B was transfected in either plasmid pEF (as a GFP fusion, a gift of M. Brandeis, Hebrew University, Jerusalem) or untagged in plasmid pEFT7MCS (a gift of S. Geley, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria) by using Transmessenger Reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), 24 h after initiation of knockdown with siRNAs. Plasmid transfection efficiencies were ≈40% as monitored by GFP-positive cells.

Immunoblot Reagents and Antibodies. Protein was harvested with cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl/1% Nonidet P-40/10% glycerol/2 mM EDTA) with protease inhibitor mixture (Roche) and 15 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. After separation by SDS/PAGE and transfer to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, immunoblots were probed with polyclonal anti-Mad2 antibodies, anti-actin antibodies (Sigma), anti-securin antibodies (a gift of M. Kirschner, Harvard University, Boston), and Neomarkers (clone DCS-280) or anti-cyclin B antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Visualization was performed with ECL Plus (Amersham Biosciences).

Proliferation Assays, Cell-Cycle Analysis, and Cell Culture. For proliferation assay, cells were harvested, stained with Trypan blue (Sigma), plated in triplicate and counted at the indicated times. For fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis, cells were fixed in 70% ethanol and were stained with 5 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma) and DNase-free RNase (Roche). A total of 10,000 cells were acquired in the PI gate by using a FACSCalibur f low cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and cellquest software (Becton Dickinson) and were analyzed on multicycle software (Phoenix Flow Systems, San Diego). HeLa, HaCaT, and IMR90 cells were obtained from ATCC. The generation of Hct-MAD2+/– cells is described elsewhere (9). A double thymidine block was performed with sequential exposure to 2 mM thymidine, followed by release into 200 ng/ml nocodazole.

Immunofluorescence and Microscopy. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, were permeabilized with 0.5% Nonidet P-40, were blocked in PBG (PBS, 0.5% BSA, and 0.2% gelatin), and were stained with mouse monoclonal cyclin B1 antibody GNS1, mouse monoclonal anti-cdc20 (both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Nup358 anti-sera (a gift of G. Blobel, The Rockefeller University, New York), or β-tubulin antibody (Sigma). Secondary staining was performed by using goat anti-rabbit-conjugated Alexa 546 and goat anti-mouse Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes). DNA was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Confocal microscopy was performed by using a Zeiss LSM510 running lsm software version 3. Real-time and in situ microscopy used metamorph software on a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope and a Roper Scientific Micromax 1300YHS camera. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and at least 100 cells were analyzed from each group per experiment, except where noted.

Cytogenetic Analysis. Metaphase spreads were performed as described (9). At least 200 metaphases were studied from each group for all analyses except where indicated.

Results

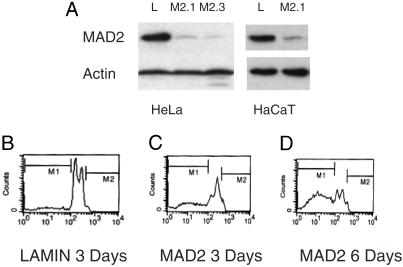

siRNA oligonucleotides were transfected into both HeLa human cervical carcinoma cells and HaCaT cells, an immortalized human keratinocyte cell line, yielding essentially identical results in both cell lines with either oligonucleotide. More than 90% of the protein was depleted in these cells, as judged by Western analysis on lysates harvested 48–72 h after transfection (Fig. 1A). Severe reduction of MAD2 protein induced rapid loss of proliferative capacity and nearly complete loss of viability by 7 days after transfection (Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). In both cell types, FACS analysis revealed the emergence of a population of cells with a sub-G1 DNA content and apoptotic bodies could be identified, consistent with apoptotic cell death, despite the presence of aberrant p53 signaling in these cells (Figs. 1 B–D and 8B and ref. 16).

Fig. 1.

Effect of MAD2 depletion on somatic human cell viability. (A) MAD2 protein depletion 48 h after transfection. (B) FACS profile of HeLa cells 3 days after lamin transfection. (C and D) FACS profiles of MAD2 knockdown HeLa cells 3 and 6 days after transfection, respectively. M1, the sub-G1 apoptotic DNA content is 15% in B, 42% in C, and 69% in D. The FACS profile of lamin at day 6 was identical to that at day 3.

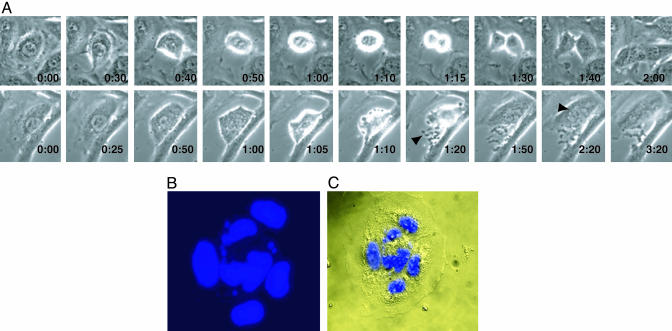

To gain insight into the basis for the loss of viability caused by MAD2 protein depletion, the morphology and distribution of mitotic cells were analyzed in situ by microscopy after DAPI staining. A 70% decrease in the percentage of observable metaphases was noted in mitotic MAD2 knockdown HeLa cells relative to control cells (data not shown). Surprisingly, chromosome missegregation and anaphase bridges, which were observed in Mad2 null embryos and occurred in MAD2+/– cells were not commonly seen in MAD2-depleted somatic cells (data not shown and refs. 8 and 9). In many cells, the DNA was either caught in the cleavage furrow or one daughter cell did not receive any genetic material, because the cell was attempting to complete division (Fig. 8 C and D). Further analysis by time lapse photography revealed that whereas the duration of mitosis in lamin transfected HeLa cells was 100 ± 9 min on average (n = 8), 8 of 11 cells studied from MAD2 knockdown cultures proceeded through mitoses in 60 ± 5 min on average (P < 0.005), and six of these cells became multinucleated, compared with none of the lamin-transfected controls (Fig. 2A). Similarly, 11% of MAD2 knockdown HaCaT cells became multinucleated, compared with <1% of transfected controls within 72 h of transfection (n = 200; Fig. 2 B and C).

Fig. 2.

Mitotic abnormalities in the absence of MAD2. (A) Time-lapse photography of lamin and MAD2 knockdown HeLa cells (×40). (Upper) A lamin-transfected cell entering mitosis at 30 min and completing cytokinesis at 2 h. (Lower) The MAD2 knockdown cell enters mitosis at 50 min, sheds cellular debris caused by the abnormal mitosis (arrow, 1:20 min), and exits at 1 h and 50 min as a multinucleated cell (best seen at arrow, 2:20 min). (B and C). Nomarsky differential interference contrast microscopy images of a multinucleated MAD2 knockdown HaCaT cell stained with DAPI (×63).

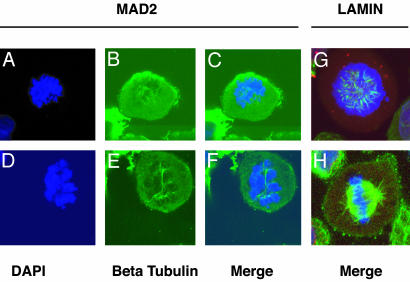

Multinucleation has been observed in the combined knockdown of Hec1 and MAD2, but has not previously been reported in cells in which MAD2 alone is depleted (17). Hct-MAD2+/– cells become multinucleated after treatment with spindle depolymerizing agents (9), suggesting that the observed phenotype in MAD2 knockdown cells may be the result of a spontaneous defect in spindle assembly. Therefore, the integrity of the spindle apparatus was examined in MAD2 knockdown cells by laser scanning confocal microscopy and indirect immunofluorescence. By using monoclonal antibodies against β-tubulin, an almost complete absence of normal spindle formation was noted. Spindles were either incompletely or asymmetrically formed with a dramatic reduction in the density of microtubule polymerization compared with wild-type cells. In some cells, sparse or no microtubule polymerization was observed (Fig. 3 A–H).

Fig. 3.

Abnormal spindle formation in the absence of MAD2 as seen by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy (×100). Shown are various degrees of abnormal or incomplete spindle formation in MAD2 knockdown HaCaT cells (A–C) and HeLa cells (D–F). (G and H) Normal spindle formation in prometaphase and metaphase lamin HeLa knockdown cells. DNA is marked by DAPI in blue, β-tubulin is in green, and the nuclear envelope (Nup 358) is stained red but is normally dissolved at these phases of mitosis.

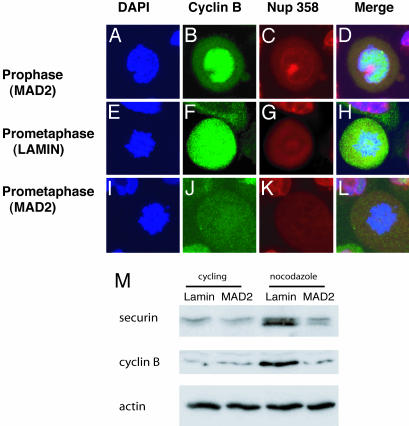

The APC ubiquitinylates several molecules implicated in normal spindle function, including cyclin B, the regulatory partner of cdc2 (18, 19). When coexpressed with cyclin B, cdc2 can induce microtubule nucleation in mammalian cells and may phosphorylate multiple substrates involved in spindle assembly (20, 21). The failure to nucleate a normal spindle in MAD2 knockdown cells motivated the analysis of the temporal pattern of cyclin B destruction during mitosis in the absence of MAD2. Cyclin B was consistently identified in prophase in MAD2 knockdown cells by immunofluorescence microscopy. The fact that cyclin B is nuclear, whereas the APC is cytoplasmic during prophase, would likely render the absence of MAD2 less critical at this phase of mitosis with regards to cyclin B stability (refs. 22 and Fig. 4 A–D). In >75% of knockdown cells, however, cyclin B was degraded prematurely by prometaphase rather than normally at anaphase as observed in lamin-transfected controls (Fig. 4 E–L and data not shown). Similarly, after activating the mitotic checkpoint by treatment of cells with nocodazole for 16 h, MAD2-transfected cells were found by Western blot analysis to contain reduced protein levels of cyclin B as well as securin, compared with lamin knockdown cells (Fig. 4M).

Fig. 4.

Premature cyclin B degradation in MAD2 knockdown HaCaT cells. Immunofluorescence microscopy showing nuclei (blue), cyclin B (green), nuclear envelope-Nup 358 (red), and merged images (×100). (A–D) MAD2 knockdown cells show high levels staining of nuclear cyclin B during prophase, during which the nuclear envelope is still visible similar to lamin controls (data not shown). (E–H) Lamin knockdown control cells stain intensely for cyclin B during prometaphase, and the nuclear envelope is dissolved at this stage of mitosis. (I–L) MAD2 knockdown cells with prometaphase morphology lacking cyclin B. (M) Immunoblot analysis of securin and cyclin B protein levels after 16 h of exposure to nocodazole comparing lamin and MAD2 knockdown HeLa cells.

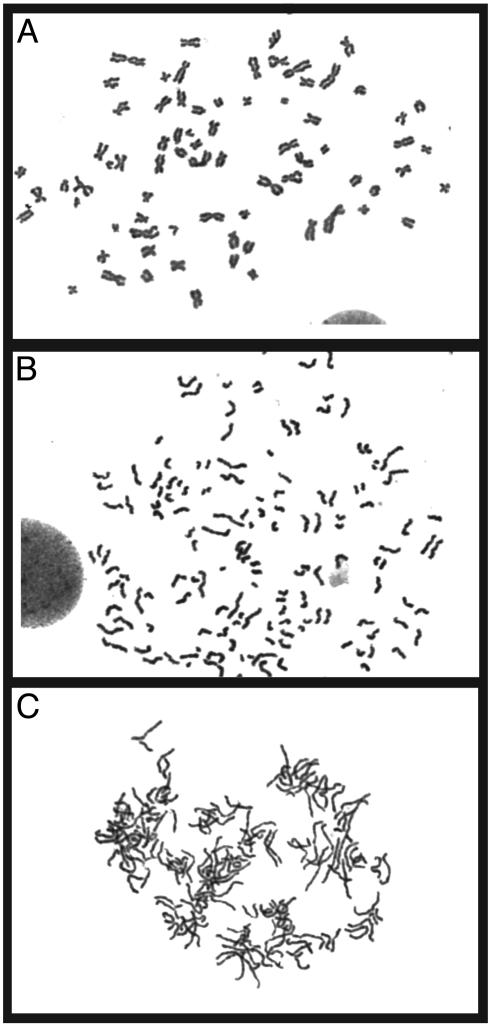

Chromosome condensation, which starts at prophase and continues through metaphase, is also induced by cyclin B-dependent cdc2 kinase activity, and therefore evidence of perturbations in this process were examined (20). An analysis of metaphase spreads from both MAD2 knockdown HeLa and HaCaT cells revealed that ≈50% of cells display premature sister chromatid separation, a phenotype previously observed in MAD2+/– mouse and human cells (9). However, unlike MAD2+/– cells, which exhibit normal chromosome condensation, nearly 100% of HeLa and 40% of HaCaT knockdown cells exhibiting premature sister chromatid separation were found to have incompletely condensed chromosomes (Fig. 5). The ability of MAD2 knockdown cells to partially condense their chromosomes is consistent with the observation that cyclin B is degraded only after prophase in these cells, permitting some degree of condensation. We did not rule out the possibility that the sister chromatids never paired properly during interphase in these cells. Reintroduction into MAD2 knockdown HeLa cells of a nondegradable cyclin B-Gfp encoding expression plasmid containing a D-box mutation specifically restored normal chromosome condensation in a subset of metaphases (P < 0.005 by Fisher's exact test) without altering the incidence of premature anaphase, underscoring the importance of loss of cyclin B protein in the generation of this phenotype (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, and ref. 23). We were unable to restore normal spindle assembly in these transfections, possibly due the difficulty of coordinating the correct timing or localization of cyclin B by ectopic expression. Alternatively, other APC substrates known to be involved in spindle assembly may be the critical targets mediating aberrant spindle formation in the absence of MAD2, rendering restoration of cyclin B insufficient (18, 19).

Fig. 5.

Altered chromosome morphology from severe MAD2 depletion. Shown are normal metaphase spread from a lamin-transfected cell (A) and a MAD2 knockdown HaCaT cell showing premature sister chromatid separation with normal condensation (B). (C) Metaphase spread from a MAD2 knockdown HaCaT cell displaying both premature sister chromatid separation and incompletely condensed chromosomes.

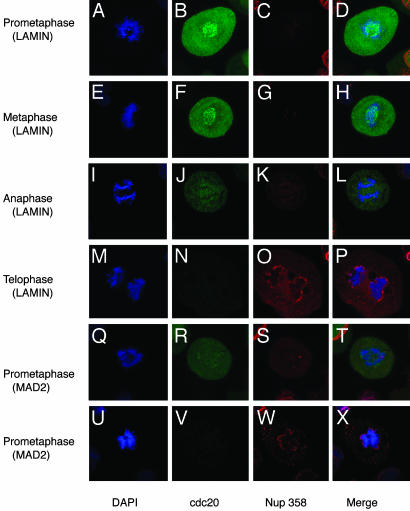

Cyclin B-associated cdc2 kinase activity prevents activation of APCCdh1, which requires dephosphorylation of Cdh1 by the phosphatase Cdc14 (24). APCCdh1 activity begins to rise during anaphase, thereby initiating mitotic exit (25, 26). Premature degradation of cyclin B would therefore be expected to result in early APCCdh1 activation. To address this possibility, we analyzed the timing of cdc20 destruction, a known APCCdh1 substrate (27). Wild-type cells exhibited both kinetochore and diffuse high-level staining of cdc20 during prometaphase and metaphase (Fig. 6 A–H). During anaphase, the kinetochore staining was lost and a lower level of cdc20 was observed, which is consistent with activation of APCCdh1 at anaphase (Fig. 6 I–L). Complete elimination of detectable protein coincided with nuclear envelope reformation during early telophase (Fig. 6 M–P). In contrast, in MAD2 knockdown cells that were in prometaphase as assessed by DNA morphology, two distinct patterns of abnormal staining were prominent. Intermediate levels of cdc20 without evidence of kinetochore staining such as is seen in wild-type anaphase cells could be identified, as well as cells that, while morphologically in prometaphase, demonstrated no detectable cdc20 staining and were attempting to reform a nuclear envelope (Fig. 6 Q–X). Interestingly, precocious nuclear envelope reformation due to premature mitotic exit resulting in the encasement of the spindle microtubules may also contribute to mitotic failure that occurs in the absence of MAD2 (Fig. 10, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 6.

Early cdc20 degradation in the absence of MAD2. Coimmunofluorescence images (×100) of DNA stained with DAPI (blue), cdc20 (green), and Nup 358 nuclear envelope protein (red), or merged images. Lamin-transfected HeLa cells showing kinetochore and diffuse staining in either prometaphase (A–D) or metaphase (E–H). Complete loss of kinetochore staining and partial loss of diffuse cdc20 staining during anaphase in lamin-transfected cell (I–L), and complete loss of cdc20 at telophase, coinciding with nuclear envelope reformation (M–P). (Q–T) Premature complete loss of kinetochore staining and partial loss of diffuse cdc20 staining in a MAD2 knockdown prometaphase HeLa cell. (U–X) Complete loss of cdc20 staining coincident with premature nuclear envelope reformation in a prometaphase knockdown cell.

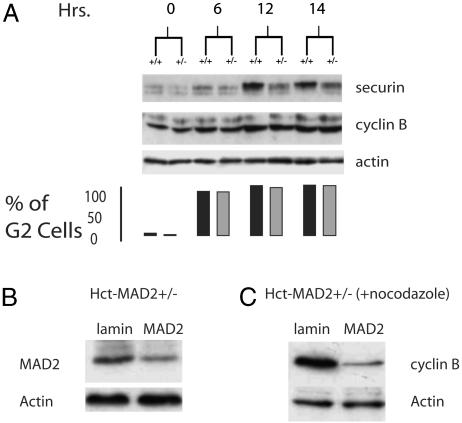

MAD2+/– cells cycle normally, form intact spindles, and do not degrade cyclin B prematurely (data not shown). They do degrade securin prematurely in the presence of nocodazole and the fact that metaphase spreads from these cells exhibit premature sister chromatid separation with completely condensed chromosomes suggests that securin and cyclin B degradation are uncoupled in the presence of one copy of MAD2 (9). Uncoupling of Pds1 (securin) and clb2 destruction has been identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, as evidenced by the observation that clb2, the regulatory partner of cdc28, undergoes two phases of destruction during mitosis. The first phase that is APCcdc20-dependent lowers but does not eliminate clb2 levels and clb2-cdc28 activity but completely destroys Pds1. The latter phase requires the lowered clb2-cdc28 kinase activity to allow APCCdh1 activation, which then destroys the remaining clb2 in late mitosis and facilitates mitotic exit (28, 29). Although the biochemical basis of the differential sensitivity of securin and cyclin B to APCcdc20 has yet to be elucidated in yeast, should a similar relationship also exist in mammalian cells, this result might become apparent when they experience the limited APC activity that is released after the loss of one copy of MAD2. Indeed, when Hct-MAD2+/– cells are synchronized by a double thymidine block at the G1/S boundary and released into nocodazole, as early as 12 h after release, securin is almost completely destroyed, whereas no obvious change in cyclin B is apparent (Fig. 7A). By siRNA treatment of Hct-MAD2+/– cells, further reduction of MAD2 protein levels resulted in the degradation of cyclin B in these cells after nocodazole treatment, supporting the notion of a dose-dependent effect of MAD2 on cyclin B degradation (Fig. 7 B and C). An analysis of chromosomes revealed decondensed chromosomes only in MAD2 knockdown cells, which is consistent with the loss of cyclin B (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

(A) Uncoupling of securin and cyclin B degradation in Hct-MAD2+/– cells after G1/S synchronization and release into nocodazole. Immunoblot analysis of securin, cyclin B, and actin reveals almost complete securin degradation with no significant loss of cyclin B protein levels in Hct-MAD2+/– cells. The bar graph shows the percentage of cells with a 4N DNA content for the corresponding time points after release from the thymidine block. Black bars, MAD2+/+ cells; gray bars, MAD2+/– cells. (B) Immunoblot analysis of MAD2 protein levels 3 days after further MAD2 depletion by siRNA in Hct-MAD2+/– cells. (C) Cyclin B protein levels after 16 h of exposure to nocodazole added 72 h after the start of transfection.

We were also able to significantly diminish MAD2 protein levels in Hct-MAD2+/– cells by retroviral transduction of short hairpins targeting a third distinct segment of the MAD2-coding sequence. Loss of MAD2 protein by this method recapitulated all aspects of the knockdown phenotype present in the HeLa and HaCaT cells (Fig. 11, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Infections with an empty vector or a sequence against murine MAD2 not found in the human genome did not produce the lethality, multinucleation, spindle defects, or premature cyclin B degradation and mitotic exit seen in MAD2 infections.

By using the short hairpins, we were further able to address whether mitotic checkpoint signaling is essential in primary human cells. IMR90 primary human fetal fibroblasts infected with the MAD2 short hairpins suffered a rapid loss of viability associated with multinucleation that was not observed in control populations (Fig. 11 M–P). We were unable to recover sufficient numbers of mitotic cells from these infections to analyze the effects of loss of MAD2 protein on mitosis, which was likely due to the sensitivity of these cells to MAD2 depletion. However, the emergence of multinucleated cells suggests similar defects to the other three cell lines tested.

Discussion

The data presented here suggest that the kinetics of APCcdc20-dependent degradation of securin and cyclin B are distinct, and provide an explanation as to why partial MAD2 inactivation results in a viable cell whose primary mitotic defect (premature anaphase) results from securin loss. By contrast, in more severely MAD2-depleted cells, the predicted increased APCcdc20 activity would be capable of degrading cyclin B (and possibly other substrates) to a low enough level that permits premature APC-Cdh1 activation and the initiation of mitotic exit during prometaphase. The degradation of cyclin B and cdc20 and nuclear envelope reformation by prometaphase that we observed in severely MAD2-depleted cells are consistent with this possibility. Differential sensitivity of APCcdc20 substrates based on the substrates' affinity for the APCcdc20 has previously been proposed to explain enhanced proteolysis of cyclin A relative to securin and cyclin B during mitotic checkpoint activation (23). Applying this model, should securin possess a higher affinity constant for APCcdc20 than cyclin B and should longer ubiquitin chains allow for more efficient delivery to the proteasome as suggested, preferential degradation of securin rather than cyclin Bin MAD2+/– cells such as we observed would occur. Another possible explanation for our results is that higher levels of securin degradation in the MAD2 knockdown cells compared with MAD2+/– cells might lead to higher levels of separase liberation earlier in mitosis. These putative affects on separase, a component of the Cdc14 early anaphase release network, could also lead to premature Cdh1-dependent cyclin B degradation and subsequent mitotic exit (30–32).

These results also highlight aspects of the mitotic checkpoint in mammalian somatic cells that are unexpected, based on previous models of MAD2 function. Yeast cells in which mad2 has been deleted are viable despite enhanced chromosome loss rates, and abnormalities in spindle formation and premature mitotic exit have not been reported (7). Differences in sensitivity between yeast and mammalian somatic cells may be due to the fact that the yeast spindle pole body is embedded in the nucleus and forms nuclear microtubules by late G1 (33). Furthermore, microtubule–kinetochore interactions in yeast may be present throughout the cell cycle (34). In contrast, the centrosome, the vertebrate spindle pole body equivalent, begins to nucleate the spindle microtubules only after entry into mitosis, potentially rendering normal spindle dynamics more vulnerable to check-point dysfunction (35). Importantly, mitotic failure was not reported in Mad2 null embryos, which missegregate their chromosomes similar to MAD2+/– cells, nor was it observed in MAD2 antibody microinjection studies (8, 36). Indeed, maternal Mad2 stores present in embryos may cause a genetically Mad2 null embryo to resemble a hypomorphic MAD2+/– cell during the decay of MAD2 protein, killing the embryo from chromosome missegregation before more severe protein depletion. MAD2 antibody microinjection may also fail to completely inactivate MAD2 function. Notably, whereas multinucleation arising from simultaneous depletion of Hec1 and MAD2 suggested that MAD2 loss is synthetic lethal with other mitotic perturbations such as are generated with loss of Hec1, the results of loss of MAD2 alone were not reported to support this conclusion (17).

Our observations also reveal an additional paradigm for tumor suppressor gene inactivation and suggest a therapeutic approach for the treatment of cancer. Models of haploinsufficiency normally reveal a more severe cancer causing phenotype when reduction to homozygosity occurs (37). However, the data presented here demonstrate that another outcome is possible, namely that whereas loss of one copy of a gene can promote tumor formation as we have previously shown for MAD2, inactivation of the second copy of the tumor suppressor gene can lead to cell death (9). To our knowledge, this is the first example of a tumor suppressor gene that is also required for somatic cell viability. MAD2 loss effectively inactivates the checkpoint while inducing a checkpoint stress owing to defective microtubule formation, resulting in high-efficiency tumor cell killing, which appears to be independent of p53. Given the preexisting low level of checkpoint activity in many tumor cells and the broad clinical utility of spindle inhibitors in cancer treatment, the mitotic checkpoint would appear to represent a rational target for anticancer drug design.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Manova and the staff of the Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center Molecular Cytology Core Facility for providing expertise and microscopy advice; Michael Brandeis and Stephan Geley for plasmids; Gunter Blobel and Marc Kirschner for antibodies; and Scott Lowe (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY) for sharing short hairpin reagents and expertise. This work was supported by Clinical Investigator Research Development Awards 5K08CA085731-03 (to L.M.) and 5R01GM054601-06 (to R.B.). E.D.-R. is supported by a Fellowship from the Ministerio de Educacion, Cultura y Deporte of Spain.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: APC, anaphase-promoting complex; siRNA, short interfering RNA; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

References

- 1.Gillett, E. S. & Sorger, P. K. (2001) Dev. Cell 1, 162–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wassmann, K. & Benezra, R. (2001) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11, 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rieder, C. L., Cole, R. W., Khodjakov, A. & Sluder, G. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 130, 941–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang, G., Yu, H. & Kirschner, M. W. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 1871–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wassmann, K. & Benezra, R. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 11193–11198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wassmann, K., Liberal, V. & Benezra, R. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 797–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li, R. & Murray, A. W. (1991) Cell 66, 519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dobles, M., Liberal, V., Scott, M. L., Benezra, R. & Sorger, P. K. (2000) Cell 101, 635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michel, L. S., Liberal, V., Chatterjee, A., Kirchwegger, R., Pasche, B., Gerald, W., Dobles, M., Sorger, P. K., Murty, V. V. & Benezra, R. (2001) Nature 409, 355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li, Y. & Benezra, R. (1996) Science 274, 246–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang, X., Jin, D. Y., Wong, Y. C., Cheung, A. L., Chun, A. C., Lo, A. K., Liu, Y. & Tsao, S. W. (2000) Carcinogenesis 21, 2293–2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang, X., Jin, D. Y., Ng, R. W., Feng, H., Wong, Y. C., Cheung, A. L. & Tsao, S. W. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 1662–1668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paddison, P. J., Caudy, A. A., Bernstein, E., Hannon, G. J. & Conklin, D. S. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 948–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elbashir, S. M., Lendeckel, W. & Tuschl, T. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 188–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemann, M. T., Fridman, J. S., Zilfou, J. T., Hernando, E., Paddison, P. J., Cordon-Cardo, C., Hannon, G. J. & Lowe, S. W. (2003) Nat. Genet. 33, 396–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henseleit, U., Zhang, J., Wanner, R., Haase, I., Kolde, G. & Rosenbach, T. (1997) J. Invest. Dermatol. 109, 722–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin-Lluesma, S., Stucke, V. M. & Nigg, E. A. (2002) Science 297, 2267–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juang, Y. L., Huang, J., Peters, J. M., McLaughlin, M. E., Tai, C. Y. & Pellman, D. (1997) Science 275, 1311–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon, D. M. & Roof, D. M. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12515–12520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Draviam, V. M., Orrechia, S., Lowe, M., Pardi, R. & Pines, J. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 152, 945–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blangy, A., Lane, H. A., d'Herin, P., Harper, M., Kress, M. & Nigg, E. A. (1995) Cell 83, 1159–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tugendreich, S., Tomkiel, J., Earnshaw, W. & Hieter, P. (1995) Cell 81, 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geley, S., Kramer, E., Gieffers, C., Gannon, J., Peters, J. M. & Hunt, T. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 153, 137–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaspersen, S. L., Charles, J. F. & Morgan, D. O. (1999) Curr. Biol. 9, 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zachariae, W., Schwab, M., Nasmyth, K. & Seufert, W. (1998) Science 282, 1721–1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters, J. M. (2002) Mol. Cell 9, 931–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfleger, C. M. & Kirschner, M. W. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 655–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeong, F. M., Lim, H. H., Padmashree, C. G. & Surana, U. (2000) Mol. Cell 5, 501–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wasch, R. & Cross, F. R. (2002) Nature 418, 556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tinker-Kulberg, R. L. & Morgan, D. O. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1936–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stegmeier, F., Visintin, R. & Amon, A. (2002) Cell 108, 207–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Visintin, R., Craig, K., Hwang, E. S., Prinz, S., Tyers, M. & Amon, A. (1998) Mol. Cell 2, 709–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson, J. B. & Ris, H. (1976) J. Cell Sci. 22, 219–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winey, M. & O'Toole, E. T. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, E23–E27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karsenti, E. & Vernos, I. (2001) Science 294, 543–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gorbsky, G. J., Chen, R. H. & Murray, A. W. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 141, 1193–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwabi-Addo, B., Giri, D., Schmidt, K., Podsypanina, K., Parsons, R., Greenberg, N. & Ittmann, M. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 11563–11568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.