Abstract

The nucleosome, the fundamental packing unit of chromatin, has a distinct chirality: 147 bp of DNA are wrapped around the core histones in a left-handed, negative superhelix. It has been suggested that this chirality has functional significance, particularly in the context of the cellular processes that generate DNA supercoiling, such as transcription and replication. However, the impact of torsion on nucleosome structure and stability is largely unknown. Here we perform a detailed investigation of single nucleosome behavior on the high affinity 601 positioning sequence under tension and torque using the angular optical trapping technique. We find that torque has only a moderate effect on nucleosome unwrapping. In contrast, we observe a dramatic loss of H2A/H2B dimers upon nucleosome disruption under positive torque, while (H3/H4)2 tetramers are efficiently retained irrespective of torsion. These data indicate that torque could regulate histone exchange during transcription and replication.

The nucleosome, the fundamental unit of chromatin, consists of 147 bp of DNA wrapped around a complex of histone proteins – (H3/H4)2 tetramer and a pair of H2A/H2B dimers1. Nucleosomes are crucial for maintaining the genome in a compacted state, which is reflected in the high binding affinity of the histone octamer to DNA (on the order of 40 kBT2,3). On the other hand, nucleosomes need to provide controlled access to DNA during vital cellular processes such as transcription and replication4,5. This is accomplished via a plethora of mechanisms, including transient thermal fluctuations (breathing),nucleosome sliding, and histone loss and deposition6,7. Whole protein families, such as histone chaperones, chromatin remodelers, and transcription factors, have been implicated in facilitating these transactions7. Recent experimental advances have also brought attention to the role that mechanical effects can play in regulating nucleosome structure and stability2,8,9. However, the relative importance of these factors is not clear.

One of the most striking features of a nucleosome is the well-defined helical path of its DNA: approximately 1.65 turns are wrapped around the histone octamer in a left-handed (negative) superhelix10. This negative supercoiling, first discovered almost 40 years ago11, has been associated with nucleosome preference of negatively over positively supercoiled DNA during in vitro assembly12,13. It has also been suggested that positive supercoiling can promote nucleosome disassembly14,15. However, the physiological relevance of these observations was for a long time questioned due to the absence of evidence for unconstrained supercoiling in eukaryotes16. Only recently have in vivo studies convincingly demonstrated that unconstrained supercoiling is ubiquitous in eukaryotic cells, even in the presence of a full complement of topoisomerases17–19. This supercoiling was found to be transcription-dependent, in agreement with the “twin-supercoiled domain” model, which states that groove-tracking enzymes, such as RNA polymerase, will generate DNA supercoiling during elongation20. It is therefore established that cellular chromatin can experience transient torsional stress.

During RNA polymerase elongation through chromatin, nucleosomes are displaced downstream and reformed upstream; this process is often accompanied by a partial or total histone loss21–24. Due to the chiral nature of the nucleosome, transcription-generated supercoiling has been hypothesized to affect both the disruption process and the fate of histones12. However, the experimental evidence for such an effect has been lacking. Biochemical and single-molecule experiments have demonstrated the flexibility of nucleosomal structure under low level of torsion, but did not investigate nucleosome disruption25–28. Conversely, nucleosome ejection and reformation has been studied under the impact of force, but in the absence of torsion2,29–31. RNA polymerase is a powerful molecular motor, capable of exerting large forces32,33 and torques34,35. In order to understand the consequences of its impact on the nucleosome, it is imperative to fully characterize nucleosome behavior under mechanical stress.

A comprehensive investigation of the response of a single nucleosome to force and torque requires full experimental control of a nucleosome under torsion – specifying a desired degree of DNA supercoiling at will, direct measurements of torque in the DNA, and access to a large range of forces. Here we achieve these capabilities using an angular optical trap (AOT), a technique that we developed for single-molecule torsional studies36–39. By investigating nucleosome disruption under different levels of torque, we find that torque differentially affects the stability of the outer and inner turns of the nucleosome. We also observe that positive torque induced dramatic H2A/H2B dimer loss, suggesting that this could be a mechanism to regulate histone turnover during transcription.

Results

Unwrapping nucleosomes under tension and torque

In order to probe nucleosome stability under torsion, we twisted a nucleosomal DNA molecule at low force to generate a desired degree of supercoiling, and then stretched the DNA to disrupt the nucleosome (Fig.1a). The range of forces (1–30 pN) and torques (−10 to +40 pN·nm) used were chosen so as to maintain DNA in its native B-form conformation37–40 and are comparable to those measured or estimated for molecular motors, such as RNA polymerase32,33,35. In order to ensure precise and efficient nucleosome positioning, we have utilized the high affinity 601 nucleosome positioning element41.

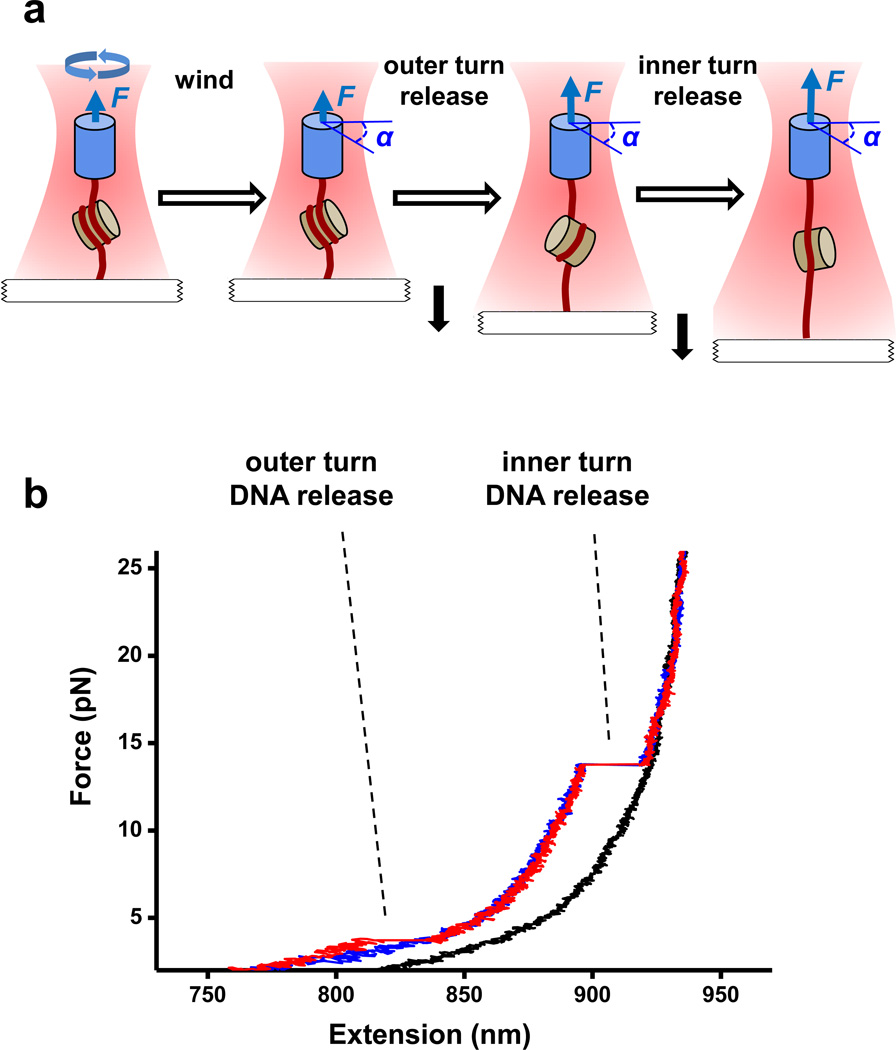

Fig. 1. Experimental configuration and representative traces.

(a) Configuration of the nucleosome stretching assay. DNA with a single nucleosome was torsionally constrained between a nanofabricated quartz cylinder and a coverglass, and was placed under desired torsion by adding twist via the cylinder. The angle of the cylinder, α, was then fixed, while the force, F, was increased at a rate of 2 pN/s to disrupt the nucleosome. This allowed the outer and inner turns of the nucleosomal DNA to be successively unwrapped. (b) Examples of individual force-extension curves of nucleosomes under approximately +19 pN·nm of torque. Red and blue curves correspond to traces with sudden or gradual outer turn DNA releases, respectively, and the black curve corresponds to a naked DNA trace.

Fig.1b shows examples of the resulting force-extension curves. We found that DNA was released in two stages during stretching: a sudden or gradual release at low force (< 6 pN); and a sudden release at high force (≥ 6 pN). These features resemble those of previous single molecule studies of torsionally unconstrained nucleosomes2,29–31 which interpreted these two stages as the unwrapping of the outer turn DNA (low force), followed by the inner turn DNA (high force). The unwrapping process of the outer turn reflects a delicate energy balance between weaker histone-DNA interactions8 and linker DNA bending30,42 and was previously observed to proceed in either a gradual2,30 or an abrupt30,43 manner, depending on the buffer conditions and type of histones used. The apparent gradual unwrapping of the outer turn might also be indicative of the possibility that the release of the two halves of the outer turn is non-cooperative. In contrast, inner turn unwrapping always manifests itself as a sudden high-force transition2,29–31.

Torque modulates outer and inner turn disruption forces

While qualitative features of nucleosome unwrapping under torque and force resembled those observed under force alone, we found significant torque-dependent quantitative differences. In order to characterize the effect of torque on nucleosome stability, we analyzed the following parameters of the unwrapping process: amount of DNA released during the sudden disruptions, force of the outer and inner turn disruptions, and the probability of sudden outer turn release.

Analysis of the sudden outer and inner turn DNA release of a nucleosome indicated that, independent of torque, approximately the same amount of DNA was released in both cases (Fig.2a). This indicates that, at the start of the stretching, ~140–150 bp were associated with a nucleosome on either relaxed or supercoiled DNA.

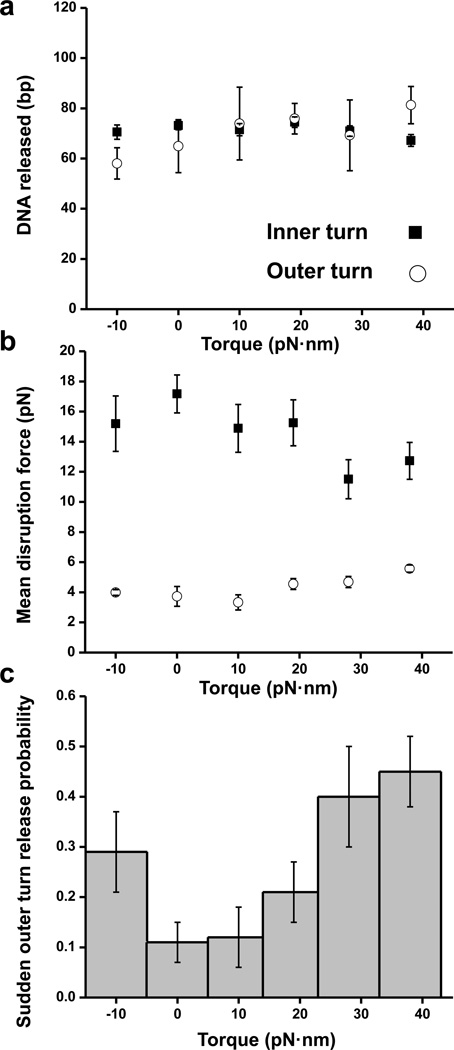

Fig. 2. Characterizing nucleosome disruption under force and torque.

(a) Sudden release of the inner (filled squares) and outer (open circles) turns of DNA in a nucleosome. Error bars are SEM. (b) Mean disruption forces of the inner (filled squares) and outer (open circles) turns of DNA in a nucleosome. Error bars are SEM. Between 25 and 64replicates have been obtained for each torque (Table 1).(c) Fraction of traces that displayed a sudden outer turn release as a function of torque. Error bars are standard errors of the binomial distribution (see Methods).

In contrast, the disruption forces were affected by torque. The trends observed were different for the outer and inner turns: torsion was found to stabilize the outer turn, but destabilize the inner turn (Fig.2b). The increased stability of the outer turn is consistent with the model of nucleosome under torsion proposed by Prunell and co-workers25,27,28, where both negative and positive torque promote tighter wrapping of the linker DNA around the histone core, thus resisting unwrapping. This tightening can disfavor DNA breathing and restrict the access of transcription factors to the nucleosomal DNA45. It is the inner turn interactions, however, that form the key impediment to the progression of transcription machinery through a nucleosome8,23. The decreased stability of the nucleosome inner turn observed under positive torque in our experiments suggests that torque is capable of assisting transcription. Interestingly, the magnitude of the destabilization was comparable to that of extensive histone tail acetylation29, known to be a hallmark of transcriptionally active chromatin46.

We also examined the probability of observing a sudden outer turn transition as a function of torque (Fig.2c). The probability exhibited a strong torque-dependence which agreed with the trends in outer turn disruption force (Fig.2b). While only ~10% of traces exhibited a sudden low force transition for unconstrained nucleosomal DNA, this number went up to 30% for DNA under −10 pN·nm and to almost 50% under +38 pN·nm of torque. This provides further support to our conclusion that torque (both positive and negative) tightens the outer turn of the nucleosomal DNA.

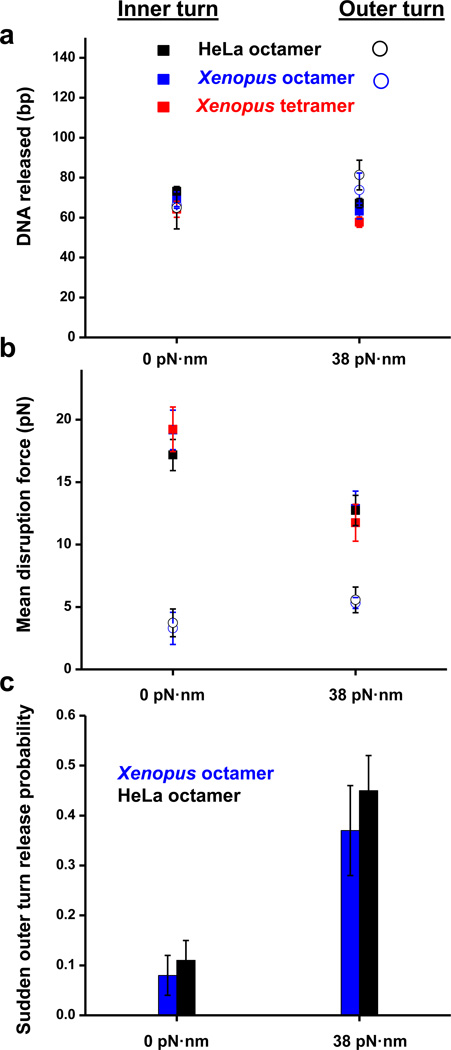

Tetrasomes do not display outer turn disruption

Which histone-DNA interactions are correlated with the outer turn unwrapping? Examination of the crystal structure indicates that while H2A/H2B-DNA contacts form the bulk of those interactions, the terminus of the nucleosomal DNA superhelix is bound to the αN helix of the histone H31. To examine the relative significance of these two contributions, we performed stretching experiments at several values of torque on tetrasomes – particles containing only an (H3/H4)2 tetramer (Fig.3). We have compared the behavior of recombinant Xenopus tetramers with that of the recombinant Xenopus octamers, as well as HeLa octamers (Fig.4). Even at +38 pN·nm of torque, no sudden outer turn disruption was observed for tetrasomes (Fig.4c), which leads us to conclude that the presence of H2A/H2B dimers is indeed required for this transition in the nucleosome and that the αN helix in histone H3 probably does not organize the last turn of DNA in the absence of H2A-H2B dimer. Notably, the high force transition for tetramers exhibited characteristics similar to that of the octamers, indicating that this transition is predominantly governed by H3/H4-DNA interactions under our experimental conditions (Fig.4a and 4b).

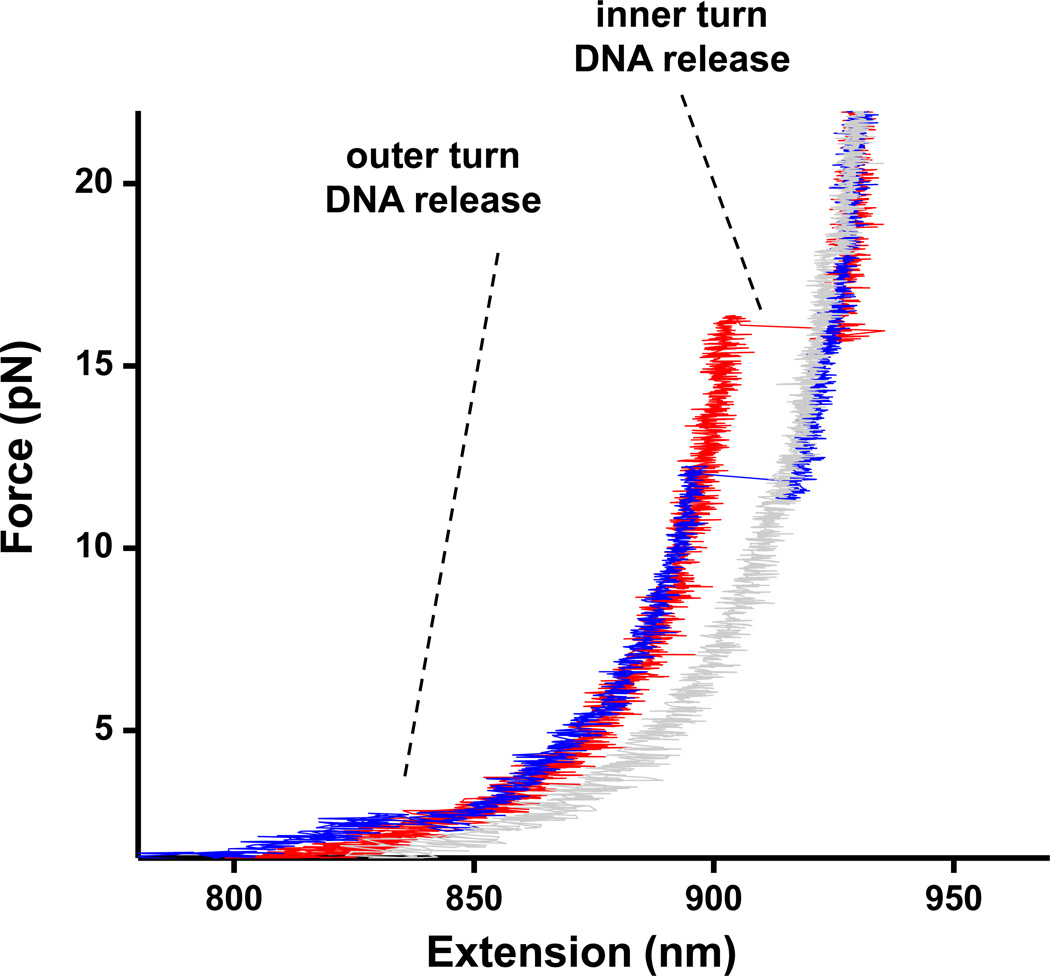

Fig. 3. Tetrasome force-extension curves.

Naked DNA (grey), recombinant tetrasome (red), recombinant nucleosome with a sudden lower force disruption (blue), all stretched under no torsion.

Fig. 4. Characterizing tetrasome disruption under force and torque.

(a) Sudden release of the inner (filled squares) and outer (open circles) turns of DNA in a tetrasome and a nucleosome. Error bars are SEM. (b) Mean disruption forces of the inner (filled squares) and outer (open circles) turns of DNA in a tetrasome and a nucleosome. Error bars are SEM. Between 15 and 37replicates have been obtained for each torque (Table 1).(c) Fraction of traces that displayed a sudden outer turn release as a function of torque. Red color refers to Xenopus recombinant tetrasome, blue - Xenopus recombinant nucleosome, black – HeLa purified nucleosome. Error bars are standard errors of the binomial distribution (see Methods).

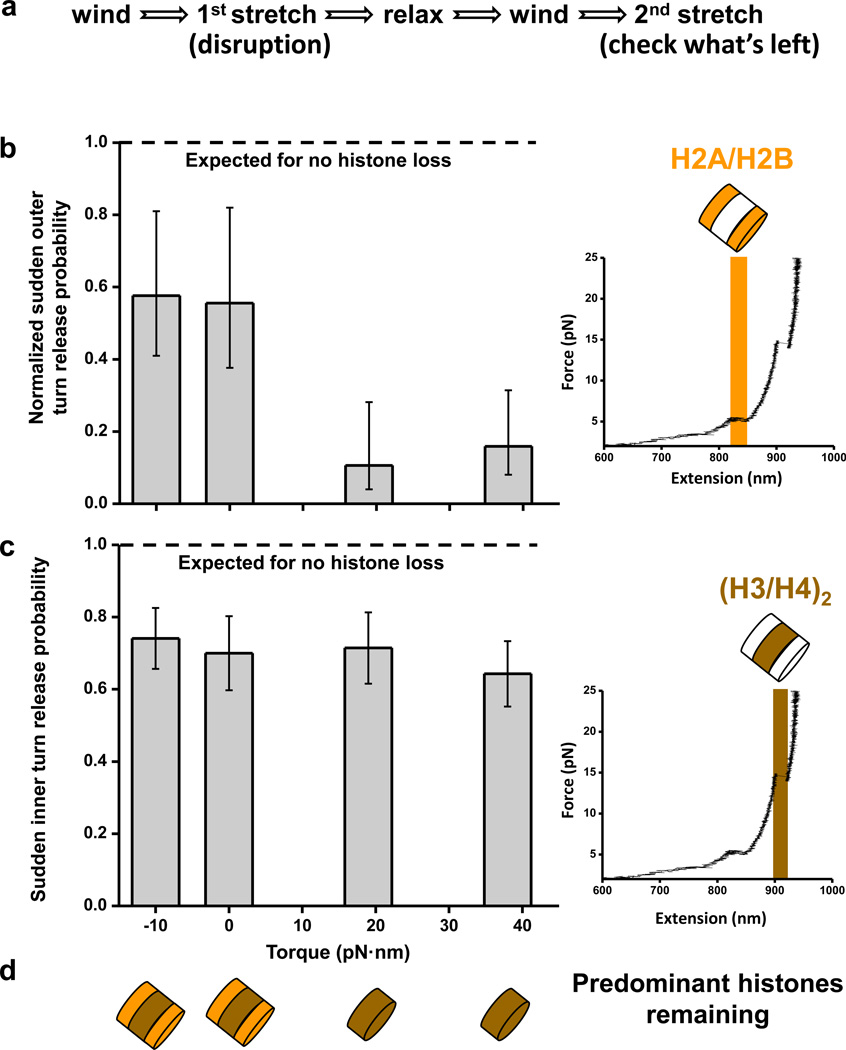

Positive torque promotes H2A/H2B dimer loss

Having established that outer turn unwrapping serves as an indicator of the H2A/H2B presence, we employed this observation to study the fate of histones upon nucleosome disruption. In the experiment, designed to mimic effects of transcription through chromatin under torque, we first stretched the DNA under a certain torque, then relaxed the molecule, wound it to reach +38 pN·nm of torque and stretched again (Fig.5a). The second stretch was designed to see which histones remained bound to the DNA and was based on the following two observations. First, the occurrence of the sudden low-force outer turn disruption requires the presence of a full octamer with both a (H3/H4)2 tetramer and H2A/H2B dimers (Fig.4c). This sudden disruption occurs at a well-defined probability for a given torque value (Fig.2c) and is always followed by a high-force sudden disruption of the inner turn DNA. Second, the occurrence of a sudden high-force disruption requires the presence of only the (H3/H4)2 tetramer (Fig.4), and represents the sudden unwrapping of the inner-turn DNA for a nucleosome or the sudden unwrapping of a single turn of a tetrasome. This always occurs as long as a (H3/H4)2 tetramer is present. The torque for the control stretch (+38 pN·nm) was chosen because it had the largest chance of observing a sudden low force transition (Fig.2c).

Fig. 5. Histone fate upon disruption under torque.

(a) Experimental strategy to examine the nucleosome stability under torque. A nucleosomal DNA molecule was supercoiled to a desired torsion, stretched at 2 pN/s from 1 pNup to 30 pNof force to disrupt the nucleosome before being relaxed over 1 s to 0.7 pN. It was then wound to +38 pN·nmand stretched again to determine which histones remained on the DNA. The time between relaxation and the second stretching was always kept at 30 s. (b) The probability of observing a sudden disruption at low force during the second stretch (right inset) was normalized to the corresponding value of the control stretch at +38 pN·nm of torque. Normalized probability of observing a sudden low force disruption is equivalent to the probability of retaining H2A/H2B after the initial stretch. Between 21 and 28replicates have been obtained for each torque value (Table 1). Error bars are standard errors of the ratio of two binomial distributions (see Methods).(c) The probability of observing a sudden high force disruption (right inset) signifies the probability of retaining (H3/H4)2 after the initial stretch. Between 21 and 28replicates have been obtained for each torque (Table 1) Insets show a representative trace of the force-extension curve resulting from a second stretch. Error bars are standard errors of the binomial distribution (see Methods).(d) Cartoons of predominant histones remaining on the DNA after disruption.

Interestingly, we found that torsion differentially affected the stability of the (H3/H4)2 tetramer and the H2A/H2B dimers within a nucleosome. High-force unwrapping upon the second stretch was observed in ~70 ± 10% of the traces, irrespective of torsion. This signifies that the (H3/H4)2 tetramer was efficiently retained on both relaxed and supercoiled DNA (Fig.5c). This lack of torque dependence can be explained by the flexible chirality of the tetramer, which can readily flip between left- and right-handed conformations47. For a nucleosome on relaxed or negatively supercoiled DNA, the sudden low force disruption upon the second stretch was observed at ~60 ± 15% of that expected for a full complement of histones. This indicates that, under these conditions, a full nucleosome is retained on the DNA with ~60% probability. In contrast, the disruption of a nucleosome under positive torque caused a significant loss of H2A/H2B dimers, so that only 10–15% of the nucleosomes retained a full complement of histones (Fig.5b). This observation suggests that transcription-generated positive supercoiling may result in preferential expulsion of H2A/H2B dimers (Fig.5d).

Discussion

In this work we present the first comprehensive investigation of single nucleosome response to torsion, examining its impact on both nucleosome stability and histone fate. We find that nucleosomes under torque and force behave qualitatively similar to nucleosomes under force alone. However, important quantitative differences suggest ways in which torque can act as an in vivo regulatory mechanism. First, torque was found to stabilize the outer turn of the nucleosome. It is known that DNA at the nucleosome entry/exit sites is prone to spontaneous unwrapping45,48, which may facilitate transcription factor binding7. In this scenario, torque appears to play a repressing role. The effect is expected to be subtle, and careful in vivo studies are required to evaluate its significance. On the other hand, the destabilizing effect of torque (especially positive torque) on the highly stable interactions of the nucleosome inner turn should favor transcription elongation through chromatin. We found that moderate positive torque of 10–20 pN·nm, the range accessible to RNA polymerase35, destabilized the inner turn interactions by over 10%, an effect comparable to that of histone tail acetylation29.

One can roughly estimate the destabilizing effect of torque on the unwrapping force of the inner-turn DNA, by assuming a one-to-one correspondence between force and torque F · Δx = τ · Δθ Given the DNA release of Δx = 25 nm and corresponding angle change of Δθ = 0.65·2π rad (assuming a left-handed tetramer is remaining on the DNA47, one expects +38 pN·nm of torque to reduce the disruption force by ~6 pN, which agrees with our measurements within their uncertainty. However, one should keep in mind that this estimate is very approximate, and does not take into account the DNA geometry, the non-equilibrium nature of the process, and potential histone rearrangements. Further theoretical work is needed to address this issue in a more rigorous fashion.

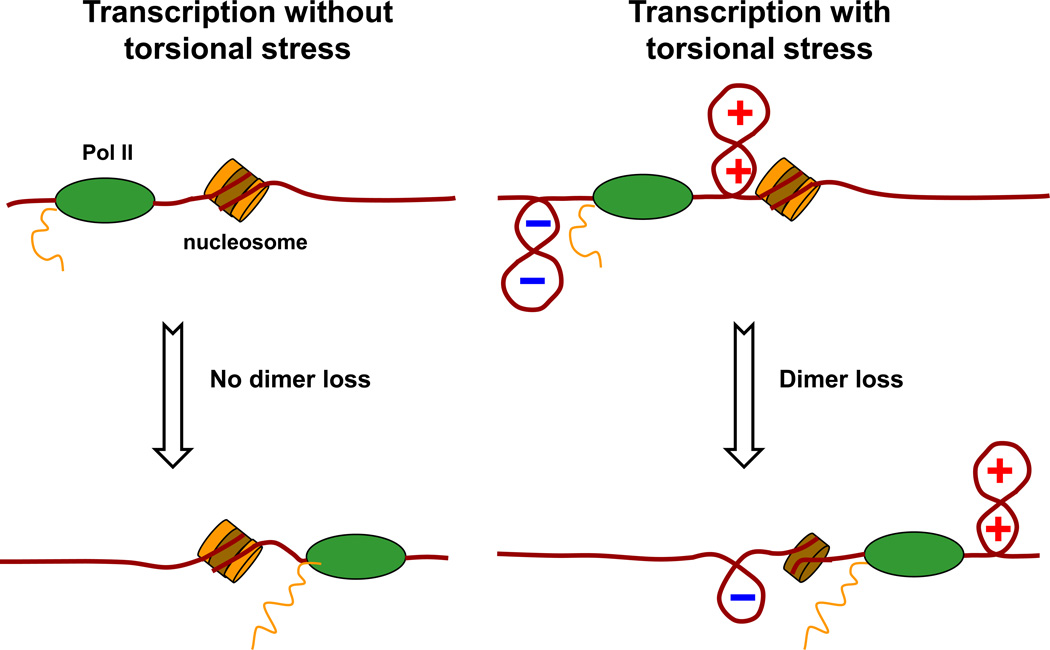

While the effect of torque on nucleosome disruption is relatively modest, its impact on the fate of histones upon nucleosome disruption is profound. We discovered that torsion differentially influences tetramer and dimer reformation. In our experiments, the (H3/H4)2 tetramer was efficiently retained on the DNA irrespective of torsion (~70% of the time), and the H2A/H2B dimers displayed a similar retention rate for relaxed and negatively supercoiled DNA. In contrast, moderate and high positive torsion led to almost complete (~80%) dimer loss. The moderate torque used in our experiments is within the range accessible to RNA polymerase and is therefore physiologically relevant. The dramatic dimer loss observed in our study thus suggests that torsion can provide an efficient mechanism for dimer eviction during transcription (Figure 6). Importantly, previous in vitro transcription studies on unconstrained DNA showed dimer loss only under a very high salt concentration (300 mM NaCl)21,49 or during rapid elongation24. Thus the high positive torsion employed in our study seems to induce a similar effect as that of the high salt concentration or rapid elongation in destabilizing a nucleosome and inducing dimer loss upon transcription.

Fig. 6.

A cartoon illustrating RNA polymerase II elongation through chromatin. During transcription under low torsion, nucleosomes remain largely intact after transcription. In contrast, during transcription under high torsion, significant dimer loss occurs in nucleosome after transcription. (H3/H4)2 tetramer is shown in brown, and H2A/H2B dimer in orange.

In this work we have used nucleosomes assembled on the high affinity 601 positioning element. It has been previously shown that the enhanced stability of this sequence is primarily due to the histone-DNA interactions at the dyad50. It is therefore expected that varying the sequence will have a primary effect on the unwrapping behavior of the nucleosome inner turn. Indeed, stretching experiments by Gemmen et al.51 have demonstrated increased variability in the inner turn unwrapping force for nucleosomes assembled on heterogeneous DNA. However, the qualitative trends in the torque-dependence of the unwrapping force observed here should hold for any sequence. Moreover, since the stability of the outer turn is not significantly enhanced by the 601 sequence50, we believe that our observations of H2A/H2B loss are likely to be generalizable to other sequences.

Our experiments are aimed at mimicking the processes of transcription and replication, which require the complete unwrapping of the nucleosomal DNA. It is conceivable that in other instances nucleosomes can be subjected to lower stress, sufficient only to disrupt the outer turn interactions. It would be of interest in future studies to explore the effect of torque on the dimer loss in those cases.

Previous in vivo studies found that H2A/H2B dimers are quickly exchanged at sites of active transcription52. This may have functional significance for the deposition of histone variants (such as H2A.Z) that are known to regulate transcription53. While many histone chaperones and remodelers, such as Nap-1, FACT, RSC and others, have been implicated in assisting H2A/H2B disassembly53, our study suggests that transcription-generated supercoiling alone can lead to efficient dimer removal. The plausibility of such a mechanism is supported by recent observations of association between active transcription and DNA supercoiling in vivo17,18. Importantly, the observed stability of tetramers in our study is also in agreement with in vivo observations of the slow exchange of H3/H4 histones52.

In summary, we propose that, on the level of individual nucleosomes, torque primarily acts as a regulator of histone exchange. Specifically, positive torsion encourages H2A/H2B dimer eviction. More work is needed to investigate the relationship between transcription-generated dynamic supercoiling and histone loss and replacement in vivo.

Methods

DNA construct

The DNA construct used for all experiments consisted of four pieces: two middle segments and two linker segments. Linkers were made by performing PCR on the pLB601 plasmid38 with a mix of 0.2 mM unmodified dNTPs (Roche Applied Science) and 0.08 mM biotin-16-dCTP (Chemcyte Inc.) or 0.04 mM digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Roche Applied Science). For biotin-modified linkers the primers used were 5’-TCC AGC CAA GAG ACC AGC CGG AAG CAT AAA and 5’- CGA AGG GAG AAA GGC GGA CAG; for dig-modified linkers: 5’- TCC ACG GTA GAG ACC AGC CGG AAG CAT AAA and 5’- CGA AGG GAG AAA GGC GGA CAG. Resulting 535 bp DNA fragments with multiple tags were digested with BsaI(New England Biolabs) to create single 4-bp overhangs and purified (PureLink Quick PCR Purification Kit, Invitrogen). Middle segments (1058 and 1720 bp) were created by PCR from thepLB601 and pBR322 (New England Biolabs) plasmids, respectively, then digested with BsaI to create two 4-bp overhangs and purified. The following primers were used: 5'-ATG GGC GAA ATC TGA CGA GAC CCA GAC AAC G and 5'-CCG CCA TTT GGC CGA GAC CAC GGA TAC for the 1 kb segment; 5'-CAA TGA TAC CGC GAG ACC CAC GCT C and 5'-GCT CTG CCT CAG CGA GAC CTA CGA GTT GC for the 1.7 kb segment. The shorter (1 kb) segment contained the 601 positioning element54 in the middle and was used for nucleosome assembly. All the BsaI cut sites were introduced via PCR primers.

Nucleosome assembly

We used purified HeLa histones, which were assembled into nucleosomes using a well-established salt-dialysis method55. Briefly, core histones were first mixed with the DNA segment containing 601 positioning element in the assembly buffer (final concentration 2M NaCl, 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, 0.1 g/l acBSA). For each reconstitution several histone-DNA ratios were used, so that the most efficiently reconstituted template could be selected. The solution was then transferred into custom-made dialysis chambers. The latter were placed into high salt buffer (2M NaCl, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 g/l sodium azide). This solution was dialyzed against low salt buffer (200 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 g/l sodium azide) at 1 ml/min for ~24 hrs. Afterwards the samples were transferred to zero salt buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) to equilibrate. Nucleosomes were stored at 4 °C for several weeks. For tetrasome experiments, recombinant Xenopus laevis(H3/H4)2 tetramers were used. To control for potential differences between different types of histones we also assembled nucleosomes using recombinant Xenopus laevis octamers with the same protocols, and performed experiments using these nucleosomes.

Single-molecule experiments

On the day of the experiment, the four DNA pieces (including 1 kb fragment with a single assembled nucleosome or tetrasome) were mixed in equal ratios at 5–10 nM concentration (25 nM for tetrasome experiments) and ligated at 16°C for 1 hour. Experiments were conducted in a climate-controlled room at a temperature of 23±1°C in a nucleosome buffer containing 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.02% Tween and 2 mg/ml acBSA. Casein from bovine milk (Sigma) at 4 mg/ml was used to passivate the surface.

In order to verify that all histones were present under our buffer conditions, we have performed unzipping experiments8,56,57. The DNA construct for these experiments consisted of two separate segments. An ~1.1 kbp anchoring segment was prepared by PCR from the plasmid pRL574 using a digoxigenin-labeled primer (5'-GTT GTA AAA CGA CGG CCA GTG AAT) and a reverse primer (5’-CCG TGA TCC AGA TCG TTG GTG AAC) and then digested with BstXI (NEB) to produce a ligatable overhang. The unzipping segment was prepared by PCR from the plasmid p601 by using a biotin-labeled primer (5’-ATG ATT CCA CCG ATC TGG CTT/iBiodT/AC ACT TTA TGC) and a reverse primer (5’- AGC GGG TGT TGG CGG GTG TC) and then digested with BstXI and dephosphorylated using CIP (NEB) to introduce a nick into the final DNA template. Nucleosomes were assembled onto the unzipping fragment by the salt dialysis method as described above. The two segments were joined by ligation immediately prior to use. An optical trapping setup was used to unzip single DNA molecules by moving the microscope coverslip horizontally away from the optical trap. As barriers to fork progression were encountered, a computer-controlled feedback loop increased the applied load linearly with time (15 pN/s) as necessary to overcome those barriers. Canonical nucleosome signatures were observed, confirming the stability of single nucleosomes under our experimental conditions.

Nucleosomal DNA stretching experiments were performed with the constraint of a fixed degree of supercoiling σ (number of turns added/intrinsic twist): −0.019, 0, +0.015, +0.028, +0.041, +0.056. At the beginning of stretching under σ = +0.041 and +0.056,plectonemes were present in the DNA, but all the disruption events were observed outside of the plectonemic region. While DNA torsional modulus is force-dependent, at high forces (>2 pN) relevant in our experiments this force-dependence is negligible58, so that stretching process can be approximated as occurring under nearly constant torques:−10, 0, +10, +19, +28, +38 pN·nm.

All stretching experiments were performed using a loading rate clamp of 2 pN/s. Tethers were stretched to 30 pN and held for 1 s at this force. When a second stretch was desired, the force was dropped to 0.7 pN in 2–3 s. The DNA was then wound to +14.8 turns at 1 Hz and then held at a constant force (so that the total time spent at 0.7 pN was always 30 s). Subsequently stretching was performed as described above. The number of molecules used for each experimental condition is recorded in Table 1.

Table 1. Number of experimental traces.

Total number of traces used to obtain the quantitative data presented in Figures 2, 4 and 5. Each trace represents a unique nucleosomal DNA molecule.

Data analysis

Data were anti-alias filtered at 1 kHz, acquired at 2 kHz, and decimated with averaging to 200 Hz. All data were acquired and analyzed using custom written LabView software. Detection of sudden nucleosomal DNA releases was performed by cross-correlating a step function with the extension time series. Cross-correlation time series exhibited a sharp peak at the sudden DNA release point. The force at this time point was called the disruption force. Basepair release was quantified by calculating extension difference right after and right before the release and then converting it to number of basepairs using WLC model of torsionally constrained DNA40,59.

Normalized sudden outer turn release probability was calculated as the ratio , where p1 is the probability of observing a sudden outer turn release during the second (control) stretch in the histone fate experiments (always performed at +38 pN·nm), and p2 is the default probability of observing a sudden transition under this torque (rightmost bar in Figure 2c). Since the experimental conditions are identical for these two experiments, we interpret the ratio being less than 1 as evidence for H2A/H2B dimer loss.

Error bar σ for the probability of outer turn release p was calculated as the standard error of a binomial distribution:

| (1) |

where n is the number of trials. Error bar for the normalized sudden outer turn release probability upon second stretch was calculated by defining the 66% confidence interval of the ratio of two proportions:

| (2) |

where p1 is the sudden outer turn release probability upon second stretch at +38 pN·nm, p2 is the sudden outer turn release probability upon control stretch +38 pN·nm, n1 and n2 are the respective number of trials, and x1 and x2 are the respective number of sudden outer turn releases60. The distribution of the disruption force and DNA release data suggested the presence of small day-to-day variations; we therefore conservatively estimated the error of the data by using the number of days when measurements were taken as the sample size. When necessary, this standard error was further corrected using the t-statistic to account for small number of observations (N<10).

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Wang lab for critical reading of the manuscript. We especially thank Dr. R.M. Fulbright for purification of the He La histones, P. Dyer and M. Scherman for Xenopus tetramers, Dr. C. Deufel for nanofabrication of quartz cylinders, Drs. S. Forth, J. Ma, R. Forties, and M. Hall, and J.T. Inman for assistance with single molecule assays, data acquisition, and data analysis, and Dr. James Sethna for helpful discussions. We wish to acknowledge support from NIH grants (GM059849 to M.D.W; GM088409 to K.L.) and an NSF grant (MCB-0820293 to M.D.W).

Footnotes

Author Contributions Statement

M.Y.S. and M.D.W. designed the project. M.Y.S performed all the experiments presented in the main text and analyzed all the data. M.L. performed control experiments for Figures 3 and 4. M.S. contributed to the fabrication of the quartz cylinders. K.L. contributed recombinant histone protein complexes. M.D.W. and M.Y.S. wrote the paper, with contributions from M.L. and K.L.

Competing Financial Interests Statement. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brower-Toland BD, et al. Mechanical disruption of individual nucleosomes reveals a reversible multistage release of DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1960–1965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022638399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ranjith P, Yan J, Marko JF. Nucleosome hopping and sliding kinetics determined from dynamics of single chromatin fibers in Xenopus egg extracts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13649–13654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701459104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alabert C, Groth A. Chromatin replication and epigenome maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:153–167. doi: 10.1038/nrm3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrews AJ, Luger K. Nucleosome structure(s) and stability: variations on a theme. Annu Rev Biophys. 2011;40:99–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell O, Tiwari VK, Thoma NH, Schubeler D. Determinants and dynamics of genome accessibility. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:554–564. doi: 10.1038/nrg3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall MA, et al. High-resolution dynamic mapping of histone-DNA interactions in a nucleosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:124–129. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavelle C. Forces and torques in the nucleus: chromatin under mechanical constraints. Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;87:307–322. doi: 10.1139/O08-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richmond TJ, Davey CA. The structure of DNA in the nucleosome core. Nature. 2003;423:145–150. doi: 10.1038/nature01595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Germond JE, Hirt B, Oudet P, Gross-Bellark M, Chambon P. Folding of the DNA double helix in chromatin-like structures from simian virus 40. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:1843–1847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark DJ, Felsenfeld G. Formation of nucleosomes on positively supercoiled DNA. EMBO J. 1991;10:387–395. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07960.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pfaffle P, Jackson V. Studies on rates of nucleosome formation with DNA under stress. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16821–16829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfaffle P, Gerlach V, Bunzel L, Jackson V. In vitro evidence that transcription-induced stress causes nucleosome dissolution and regeneration. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16830–16840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levchenko V, Jackson B, Jackson V. Histone release during transcription: displacement of the two H2A-H2B dimers in the nucleosome is dependent on different levels of transcription-induced positive stress. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5357–5372. doi: 10.1021/bi047786o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinden RR, Carlson JO, Pettijohn DE. Torsional tension in the DNA double helix measured with trimethylpsoralen in living E. coli cells: analogous measurements in insect and human cells. Cell. 1980;21:773–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsumoto K, Hirose S. Visualization of unconstrained negative supercoils of DNA on polytene chromosomes of Drosophila. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3797–3805. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kouzine F, et al. Transcription-dependent dynamic supercoiling is a short-range genomic force. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:396–403. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kouzine F, Sanford S, Elisha-Feil Z, Levens D. The functional response of upstream DNA to dynamic supercoiling in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:146–154. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu LF, Wang JC. Supercoiling of the DNA template during transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:7024–7027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kireeva ML, et al. Nucleosome remodeling induced by RNA polymerase II: loss of the H2A/H2B dimer during transcription. Mol Cell. 2002;9:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00472-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulaeva O, et al. Mechanism of chromatin remodeling and recovery during passage of RNA polymerase II. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1272–1278. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodges C, Bintu L, Lubkowska L, Kashlev M, Bustamante C. Nucleosomal fluctuations govern the transcription dynamics of RNA polymerase II. Science. 2009;325:626–628. doi: 10.1126/science.1172926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bintu L, et al. The elongation rate of RNA polymerase determines the fate of transcribed nucleosomes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;18:1394–1399. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bancaud A, et al. Structural plasticity of single chromatin fibers revealed by torsional manipulation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:444–450. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bancaud A, et al. Nucleosome chiral transition under positive torsional stress in single chromatin fibers. Mol Cell. 2007;27:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Lucia F, Alilat M, Sivolob A, Prunell A. Nucleosome dynamics. III. Histone tail-dependent fluctuation of nucleosomes between open and closed DNA conformations. Implications for chromatin dynamics and the linking number paradox. A relaxation study of mononucleosomes on DNA minicircles. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:1101–1119. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sivolob A, Prunell A. Nucleosome conformational flexibility and implications for chromatin dynamics. Philos Transact A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2004;362:1519–1547. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2004.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brower-Toland B, et al. Specific contributions of histone tails and their acetylation to the mechanical stability of nucleosomes. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mihardja S, Spakowitz AJ, Zhang Y, Bustamante C. Effect of force on mononucleosomal dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15871–15876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607526103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simon M, et al. Histone fold modifications control nucleosome unwrapping and disassembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12711–12716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106264108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang MD, et al. Force and velocity measured for single molecules of RNA polymerase. Science. 1998;282:902–907. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galburt EA, et al. Backtracking determines the force sensitivity of RNAP II in a factor-dependent manner. Nature. 2007;446:820–823. doi: 10.1038/nature05701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harada Y, et al. Direct observation of DNA rotation during transcription by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Nature. 2001;409:113–115. doi: 10.1038/35051126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma J, Bai L, Wang MD. Transcription under torsion. Science. 2013;340:1580–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.1235441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.La Porta A, Wang MD. Optical torque wrench: angular trapping, rotation, and torque detection of quartz microparticles. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;92:190801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.190801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deufel C, Forth S, Simmons CR, Dejgosha S, Wang MD. Nanofabricated quartz cylinders for angular trapping: DNA supercoiling torque detection. Nat Methods. 2007;4:223–225. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forth S, et al. Abrupt buckling transition observed during the plectoneme formation of individual DNA molecules. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;100:148301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.148301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheinin MY, Forth S, Marko JF, Wang MD. Underwound DNA under tension: structure, elasticity, and sequence-dependent behaviors. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;107:108102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.108102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marko JF. Torque and dynamics of linking number relaxation in stretched supercoiled DNA. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2007;76:021926. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.76.021926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lowary PT, Widom J. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1998;276:19–42. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sudhanshu B, et al. Tension-dependent structural deformation alters single-molecule transition kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1885–1890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010047108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kruithof M, van Noort J. Hidden Markov analysis of nucleosome unwrapping under force. Biophys J. 2009;96:3708–3715. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bondarenko VA, et al. Nucleosomes can form a polar barrier to transcript elongation by RNA polymerase II. Molecular Cell. 2006;24:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li G, Widom J. Nucleosomes facilitate their own invasion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:763–769. doi: 10.1038/nsmb801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campos EI, Reinberg D. Histones: annotating chromatin. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:559–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.032608.103928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamiche A, et al. Interaction of the histone (H3-H4)2 tetramer of the nucleosome with positively supercoiled DNA minicircles: Potential flipping of the protein from a left- to a right-handed superhelical form. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7588–7593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li G, Levitus M, Bustamante C, Widom J. Rapid spontaneous accessibility of nucleosomal DNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:46–53. doi: 10.1038/nsmb869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kulaeva OI, Hsieh FK, Studitsky VM. RNA polymerase complexes cooperate to relieve the nucleosomal barrier and evict histones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11325–11330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001148107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chua EYD, Vasudevan D, Davey GE, Wu B, Davey CA. The mechanics behind DNA sequence-dependent properties of the nucleosome. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40:6338–6352. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gemmen GJ, et al. Forced unraveling of nucleosomes assembled on heterogeneous DNA using core, histones, NAP-1, and ACF. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2005;351:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kimura H, Cook PR. Kinetics of core histones in living human cells: little exchange of H3 and H4 and some rapid exchange of H2B. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1341–1353. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.7.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petesch SJ, Lis JT. Overcoming the nucleosome barrier during transcript elongation. Trends Genet. 2012;28:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lowary PT, Widom J. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J Mol Biol. 1998;276:19–42. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dyer PN, et al. Reconstitution of nucleosome core particles from recombinant histones and DNA. Methods Enzymol. 2004;375:23–44. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)75002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dechassa ML, et al. Structure and Scm3-mediated assembly of budding yeast centromeric nucleosomes. Nat Commun. 2011;2 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li M, Wang MD. Unzipping Single DNA Molecules to Study Nucleosome Structure and Dynamics. Method Enzymol. 2012;513:29–58. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-391938-0.00002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moroz JD, Nelson P. Torsional directed walks, entropic elasticity, and DNA twist stiffness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14418–14422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marko JF. DNA under high tension: Overstretching, undertwisting, and relaxation dynamics. Physical Review E. 1998;57:2134–2149. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Koopman PAR. Confidence-Intervals for the Ratio of 2 Binomial Proportions. Biometrics. 1984;40:513–517. [Google Scholar]