Abstract

Electrical excitation of peripheral somatosensory nerves is a first step in generation of most pain signals in mammalian nervous system. Such excitation is controlled by an intricate set of ion channels that are coordinated to produce a degree of excitation that is proportional to the strength of the external stimulation. However, in many disease states this coordination is disrupted resulting in deregulated peripheral excitability which, in turn, may underpin pathological pain states (i.e. migraine, neuralgia, neuropathic and inflammatory pains). One of the major groups of ion channels that are essential for controlling neuronal excitability is potassium channel family and, hereby, the focus of this review is on the K+ channels in peripheral pain pathways. The aim of the review is threefold. First, we will discuss current evidence for the expression and functional role of various K+ channels in peripheral nociceptive fibres. Second, we will consider a hypothesis suggesting that reduced functional activity of K+ channels within peripheral nociceptive pathways is a general feature of many types of pain. Third, we will evaluate the perspectives of pharmacological enhancement of K+ channels in nociceptive pathways as a strategy for new analgesic drug design.

Keywords: K+ channel, M channel, two-pore K+ channel, KATP channel, Dorsal root ganglion, Pain, Nociception.

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral somatosensory systems in mammals are formed by mechano-, temperature- and damage-sensing (nociceptive) neurons whose cell bodies reside in the peripheral ganglia (e.g. dorsal root ganglia, DRG, trigeminal ganglia, TG or nodose ganglia) while their long axons are spread throughout the body within sensory fibres. Distal ends of these axons form nerve endings in the skin, muscle, vasculature, viscera, etc. whereas proximal ends synapse in the spinal cord. Electrical excitation of peripheral terminals of sensory neurons is a primary event in somatosensation, including pain. Conversely, the origin of most pains is the excitation of peripheral sensory fibres. These peripheral ‘nociceptive’ signals may be amplified centrally to reach pain-inducing intensity but, nevertheless, the peripheral signal is almost invariably necessary to trigger pain (excluding rare instances of pain of purely central origin). The excitation of peripheral nociceptive terminal or fibre is brought about by the concerted action of its plasmalemmal ion channels. Accordingly, channelopathies often underlie pathological pain states [1] and many current and prospective analgesics target ion channels [2]. Acute, physiological pain is initiated by opening of sensory ion channels within nociceptive terminals in response to damaging (or potentially damaging) stimuli of sufficient strength. Thus, damaging cold activates TRPM8 channel [3], damaging heat activates TRPV1 [4] while strong mechanical stimulation activates mechanosensitive channels which can be Piezo2 [5]. Most of these sensory channels are non-selective cation channels which acutely depolarize nociceptive terminals causing action potential (AP) firing. These channels deactivate upon cessation of stimulation and many of them inactivate even in the presence of continuous stimulation. These mechanisms ensure that acute physiological pain is transient in nature. However, inflammation, nerve injury or degeneration often result in conditions where nociceptive signalling becomes persistent and pain – chronic. These chronic pain conditions are often characterized by persistent overexcitability of peripheral nociceptors brought about by medium to long-term changes in ion channel activity (i.e. post-translational modifications, changes in trafficking, transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of ion channel gene expression) [1, 2]. Treatment of chronic pain remains a challenge since most targets for current analgesics are within the CNS and, thus, are liable to various side-effects. Moreover, addiction, tolerance and limited efficacy further hinder successful chronic pain management. Therefore new ideas for analgesic drug design are urgently needed, especially given the number of recent high-profile failures with some prospective targets (i.e. the neurokinin receptor 1 antagonists [6]), which have caused many lead pharmaceutical companies to curb their R&D in this area.

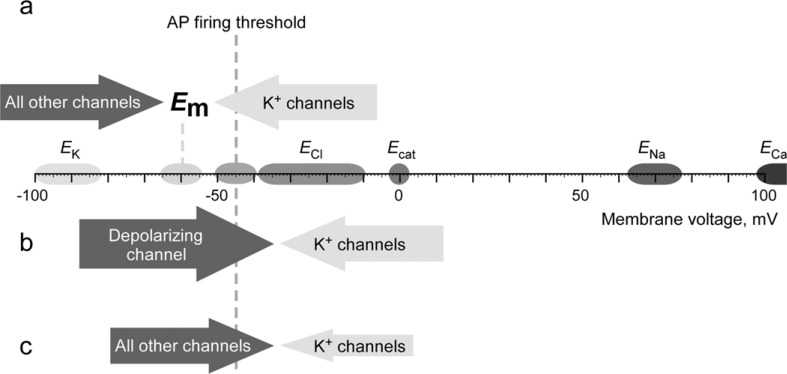

Let us consider plasma membrane of a mammalian nociceptive nerve ending at rest (Fig. 1a; the figure is based on the data available for the cell body of a DRG neuron; while ionic gradients in the terminals can differ somewhat, we believe that the overall superposition is correct). The resting membrane potential (Em) of small-diameter dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neuron has been measured to be in the range of -55 – -65 mV [7-9]. Since adult sensory neurons have high intracellular Cl- concentration with ECl around -40 - -30 mV [10-13] (and this value can get even higher in inflammation [14]), the only ion channels that can drive Em towards –65 mV are K+ channels. Therefore, depolarization of plasma membrane sufficient to trigger AP can be induced by either i) activation of any of the non-K+ channels of the plasma membrane (Fig. 1b) or ii) inhibition of K+ channels that are open at Em (Fig. 1c). The overwhelming majority of known mechanisms of acute excitation of nociceptors belong to the group i) of the above example (however a depolarization through a K+ channel inhibition as a mechanism of burning sensation produced by the Szechuan pepper has been suggested [15], see below). Many ionic mechanisms underlying chronic pain conditions also belong to this group (that is, these are mediated by the upregulation or enhancement of depolarizing ion channels; see [16, 17] for review). This is why the majority of current research in the field is focused on these depolarizing ion channels (i.e. TRP, P2X, various Na+ and Ca2+ channels) while studies into the role of K+ channels in pain are less abundant. Nevertheless, the role of K+ channels in the control of resting membrane potential, AP firing threshold, AP shape and frequency is pivotal. Indeed, early studies indicated that K+ channel inhibition with broad-spectrum K+ channel blockers induces spontaneous activity in peripheral fibres [18, 19]. Virtually in every case where this was tested (see below), peripheral hyperexcitability in chronic pain states coincided with downregulation of K+ channel/conductance in sensory nerves. Importantly, downregulation of a K+ channel activity can potentially maintain overexcitable state of the membrane indefinitely as there is no issue with desensitization or inactivation as in the case where overexcitable state of the membrane is maintained by the activation of a depolarizing ion channel. Thus, suppression of K+ conductance may indeed represent a general condition of a ‘painful’ nerve. In support to this hypothesis, in a recent screening conducted by the Mayo Clinic, among 319 patients with autoantibodies against voltage-gated K+ channels found in serum, chronic pain was reported in 159 (50%), which is 5 times more frequent than in patients with any other neurological autoantibodies [20]. Twenty-eight per cent of these patients had chronic pain as a sole symptom. Importantly, often the only obvious neuropathology in these patients was the abnormalities in cutaneous nociceptive fibres [20] suggesting that the pain produced by K+ channel autoantibodies is largely of a peripheral origin. This study further demonstrates that when K+ channel activity or abundance in nociceptors is suppressed (whatever the mechanism is), pain is a likely outcome. In agreement with this generalisation, pharmacological augmentation of peripheral K+ channel activity consistently alleviated pain in laboratory tests (see below). The main hypothesis of this review therefore is that downregulation of K+ channel activity can represent a general mechanism for chronic peripheral nerve overexcitability while pharmacological K+ channel enhancers (or ‘openers’) may indeed soothe overexcitable nerves.

Fig. (1).

Diagram depicting influence of various ion channels on the resting membrane potential of a nociceptive neuron. a, Neuron at a resting state. b, Depolarization of nociceptive neuron is caused by activation of depolarizing ion channel, i.e. a non-selective cation channel like TRPV1 or a sodium-selective channels like ASICs or a Cl--selective channel like TMEM16A. c, Depolarization is produced by closure of K+ channels while activity of other channels remains unchanged. It is important to point out that while inhibition of K+ channels generally results in depolarization and increased excitability, the latter effect is not the only possible outcome. Thus, prolonged depolarization can cause inactivation of voltage gated Na+ channels thus reducing AP firing. In some instances, inhibition of voltage-gated K+ channels can slow down AP repolarization and, thus, reduce the AP frequency. However, in the majority of cases K+ channel inhibition is indeed excitatory.

Mammalian Potassium Channels

The K+ channel nomenclature and structural classification can be found in many recent publications (e.g. in [21]). Briefly, mammalian K+ channels are subdivided into several large groups. i) Voltage-gated K+ channels (Kv); pore-forming (a) subunits of Kv channels have 6 transmenbrane domains (TMD) S1-S6, a voltage sensor domain (S1-S4) and a pore which is formed by a re-entrant loop between S5 and S6. The functional channels are formed by homo- or heteromeric complexes of four Kv subunits. There are 12 families of Kv channels, Kv1 – Kv12. ii) Ca2+-activated K+ channels (KCa) have 6-TMD architecture that is similar to Kv although some subunits of the family have one extra TMD (S0). KCa channels have extended carboxy termini harbouring regulatory domains. iii) Two-pore K+ channels (K2P); these channels are substantially different from 6-TMD channels; they are formed by dimers of 4-TMD subunits, each of which has two independent pore-forming loops. K2P do not have a well-defined voltage sensor; there are 15 K2P channels in mammals. iv) Inwardly-rectifying K+ channels (Kir); these channels have two TMDs and one pore; they do not have a defined voltage sensor domain. In mammals there are 15 Kir channel subunits subdivided into 7 families, Kir1 – Kir7. Members of all four major groups of K+ channels are expressed in nociceptive neurons and the next section will summarize current literature on this subject.

Expression of K+ Channels in Nociceptive Sensory Neurons

When attempting to compose a generalised picture of the K+ channels of nociceptive neurons one has to bear in mind certain difficulties intrinsic to the peripheral somatosensory system. Sensory neurons of peripheral ganglia represent a very heterogeneous population of sensors with various modalities and nociceptive neurons represent only one group of sensory neurons. Moreover, nociceptors themselves are rather heterogeneous group. Two major classes of nociceptors are distinguished: i) medium-diameter, thinly myelinated Aδ afferents (mediate ‘fast’ pain) and ii) small-diameter, unmyelinated C-type afferents (mediate delayed or ‘slow’ pain). These can be further subdivided into various sub-modalities (see [17] for review). Briefly, Aδ afferents can be categorised into type I (high-threshold mechanical nociceptors) and type II (high threshold for mechanical stimuli but low threshold for heat activation). C fibres can, in turn, be divided into heat- and mechano-sensitive neurons, heat sensitive but mechanically insensitive neurons, itch-sensitive neurons etc [17]. Alternatively, nociceptors can be classified by expression of certain markers. Thus, ‘peptidergic’ nociceptors express calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P while ‘non-peptidergic’ nociceptors bind the plant lectin IB4. Subpopulations of nociceptors also differ in the expression of specific ion channels such as TRPV1, TRPA1, TRPM8, Nav1.8, Nav1.9 etc. Such heterogeneity creates obvious problems for generalization of the properties of nociceptors: their different sensory modalities are underpinned by differentially attuned excitability and, therefore, different patterns of ion channel expression. This difficulty is further aggravated by the limits in scientist’s ability to classify sensory neurons experimentally. Thus, in electrophysiological recordings neurons are usually classified solely by size or membrane capacitance (in addition, one can combine this with the responsiveness to certain stimulation, i.e. response to capsaicin would identify a TRPV1-positive nociceptor). In immunohistochemical experiments neurons are also classified by size (which can be sometimes problematic in tissue sections) and co-staining with a limited number of markers (however there is no way to evaluate functional properties of neurons). Biochemical and molecular biological studies performed on lysates of entire sensory ganglia are even less specific as these not only average the characteristics of heterogenous neurons but also introduce contribution of various non-neuronal cell types that are present in sensory ganglia (satellite glia, vasculature, connective tissue etc). Finally, since sensory neuron cell bodies are the most experimentally amenable element of the afferent, the majority of data indeed reports the expression and function of ion channels in the nociceptive neuron cell bodies. However, the majority of sensory events are localised to nerve terminals and fibres; therefore, since neuron is a highly specialized cell, the ‘channelome’ of the cell body will not necessarily match that of the axon or the nerve endings.

With all the above limitations in mind we will nevertheless try to recapitulate the available literature on the functional expression of K+ channels in nociceptors. Due to the considerations of space and focus, we will not attempt to comprehensively cover the expression of K+ channel auxiliary and regulatory subunits. As summarized in Table 1, nociceptors express representative subunits from all major groups of mammalian K+ channels.

Table 1.

K+ Channel Expression in Peripheral Somatosensory System

| K+ Channel Family | a-subunit | Species | Assay | Commentary | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kv1 | Kv1.1 - 1.6 | Rat | RNase protection assay, RT-PCR | Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 mRNAs were highly abundant while Kv1.3 - 1.6 mRNAs were detected at lower levels in L4-L5 DRGs | [28, 32] |

| Kv1.1, Kv1.2, Kv1.4 | Rat | IHC, electrophys. | Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 were predominantly found in large DRG neurons; small-diameter DRG neurons predominantly (but not exclusively) expressed Kv1.4. IB4-positive neurons expressed mostly Kv1.4 | [31, 33] | |

| Kv2 | Kv2.1, Kv2.2 | Rat | RT-PCR, IHC, electrophys. | mRNA products were found in the whole ganglion lysates and immunoreactivity found in cultured small neurons | [32, 35] |

| Kv2.1, Kv2.2 | Rat | IHC, in situ hybridization | Kv2.1 and Kv2.2 immunoreactivity and mRNA products were detected in DRG neurons of all sizes | [36] | |

| Kv3 | Kv3.1, Kv3.2, Kv3.5 | Rat | RT-PCR | mRNA products were found in the whole ganglion lysates | [32] |

| Kv3.4 | Rat | IHC | Kv3.4 expression was found mainly in C fibres (including axons, cell bodies and central terminals) | [38] | |

| Kv4 | Kv4.1, Kv4.2, Kv4.3 | Rat | RT-PCR | mRNA products were found in the whole ganglion lysates | [32] |

| Kv4.1, Kv4.3 | Rat | RT-PCR, IHC, electrophys. | mRNA and immunoreactivity of Kv4.1 and 4.3 (but not Kv4.2) was detected in small DRG neurons | [39] | |

| Kv4.1, Kv4.3 | Rat | In situ hybridization, IHC | mRNA products and immunoreactivity of Kv4.1 and 4.3 (but not Kv4.2) were detected. Kv4.3 was found mostly in small neurons while Kv4.1 in neurons of all sizes | [40] | |

| Kv4.3 | Rat | IHC | Kv4.3 expression was found mainly in non-peptidergic nociceptors | [38] | |

| Kv7 | Kv7.2, Kv7.3, Kv7.5 | Rat | RT-PCR, IHC, Electrophys. |

Detection of mRNA and immunoreactivity of Kv7.2, Kv7.3 and Kv7.5 in cultured DRG neurons of all sizes. M-like currents were recorded from small DRG neurons | [44] |

| Kv7.2 | Rat | RT-PCR, IHC, electrophys. | Kv7.2 was found to be predominantly expressed in small nociceptive neurons and unmyelinated fibres. M-like currents were recorded from acute DRG slices from adult rats | [45] | |

| Kv7.2 | Rat | IHC, electrophys. | Kv7.2 immunoreactivity was reported in skin terminals and afferents of Ad and C fibres. M current activity in the fibres was confirmed electrophysiologically | [48] | |

| Kv7.2 | Rat | IHC | Kv7.2 immunoreactivity was enriched in the nodes of Ranvier of myelinated fibres | [49, 50] | |

| Kv7.2, Kv7.3, Kv7.5 | Rat, mouse | IHC | Kv7.2 was found predominantly expressed in large DRG neurons and in the nodes of Ranvier of myelinated fibres; Kv7.3 was found in the nodes as well. Kv7.5 immunoreactivity was found predominantly in small neurons | [46] | |

| Kv7.2, Kv7.3, Kv7.5 | Rat | IHC, electrophys. | Expression of Kv7.2, Kv7.3 and Kv7.5 was found in the peripheral terminals of the aortic depressor nerve (nodose ganglion neurons). Kv7.2 was found in un-myelinated C fibres | [57] | |

| Silent Kvs | Kv8.1, Kv9.1, Kv9.3 | Rat | RT-PCR, IHC, electrophys. | mRNA products were found in the whole ganglion lysates and immunoreactivity for Kv9.1 and 9.3 was found in cultured small neurons | [35] |

| Kv9.1 | Rat | IHC, in situ hybridization | Kv9.1 immunoreactivity was detected in predominantly large, myelinated DRG neurons | [36] | |

| K2P | TASK-1, TASK-3, TREK-1, TRAAK, TWIK-1 | Rat | In situ hybridization | mRNA products were found in various subpopulations of DRG neurons. TWIK-1 was more abundant in large neurons | [63] |

| K2P | TRESK, TRAAK, TREK-2, TWIK-2, TREK-1, THIK-2, TASK-1, TASK-2, THIK-1, TASK-3 | Rat | RT-PCR | Whole DRG lysates were analysed for K2P expression, the mRNA abundances were found to follow the order of TRESK > TRAAK > TREK-2 = TWIK-2 > TREK-1=THIK-2 >TASK-1>TASK-2 > THIK-1 = TASK-3 | [64] |

| TREK-2, TRESK, TREK-1, TREK-2, TRAAK |

Rat | Correlative single-channel analysis, RT-PCR | TREK-2 and TRESK were found to underlie the majority of background K+ conductance in small- and medium-size DRG in culture | [65] | |

| TREK-1 | Mouse | IHC | TREK-1 immunoreactivity was abundant in DRG sections, small- and medium-sized neurons were stained predominantly | [68] | |

| TASK-1, TASK-2, TASK-3 | Rat | IHC | Expression of three TASK subunits in subpopulations of small- and medium-diameter DRG neurons have been characterized | [160] | |

| KATP | Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1, SUR2 | Rat | RT-PCR, IHC, western blot | Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1 and SUR2 mRNA products were found in whole DRG lysates; protein expression for all but Kir6.1 was confirmed by western blot and immunohistochemistry in subpopulation of neurons of various sizes | [74] |

| Slo | Slo1, rb2 | Rat | RT-PCR, electrophys. | Presence of Slo1/rb2 channels in small-diameter DRG neurons has been verified by correlative patch clamp analysis; rb2 expression was confirmed by RT-PCR from whole ganglion lysates | [78] |

| Slo2.1, Slo2.2 | Rat | RT-PCR, electrophys. | KNa currents were recorded in medium-size DRG neurons, presence of Slo2.1, Slo2.2 mRNA was confirmed by RT-PCR from whole ganglion lysates | [81] | |

| Slo2.2 | Rat | IHC, electrophys. | Slo2.2 immunoreactivity and KNa currents were found in DRG neurons of all sizes (≈90% of all neurons) | [80] |

IHC, immunohistochemistry.

Voltage-gated K+ Channels

Early electrophysiological characterization of DRG neurons revealed two types of voltage-gated K+ currents: transient (inactivating) A current (IKA) and a sustained, delayed-rectifier current (IKDR) [22-28]. Within both types of currents further biophysically and/or pharmacologically distinct components can be identified and these differ somewhat between the sensory neuron types. Thus, two or three types of IKA can be distinguished by their different inactivation kinetics and sensitivity to tetraethylammonium (TEA) [23, 24, 26, 28-30]. The IKA with slower inactivation kinetics is predominantly found in small-diameter nociceptors which also express TTX-insensitive Na+ channels and TRPV1 [26, 27]. IKDR is also not homogenous and different fractional delayed rectifier currents were identified [26]. Table 1 summarizes data on the expression of a-subunits of voltage-gated K+ channels in sensory neurons.

Among the Kv1 channel family the most abundantly expressed in DRG neurons are Kv1.1, Kv1.2 and Kv1.4 [28, 31-33] (although expression of other Kv1 channels can also be detected by RT-PCR from the whole ganglion lysates [28]). Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 are predominantly found in non-nociceptive, large neurons where these contribute to the 4-aminopiridine (4-AP) and a-dendrotoxin (a-DTX) sensitive IKDR and slower IKA [28, 31-33]. In contrast, in small nociceptive DRG neurons the predominant Kv1 a-subunit is Kv1.4 [31, 33], a rapidly inactivating K+ channel contributing to IKA [34].

A significant contribution to IKDR and slower IKA in nociceptors is reportedly provided by Kv2 channels (Kv2.1 and Kv2.2) either alone or as multimeric channels formed by Kv2 channels and silent Kv channel subunits such as Kv9.1 or Kv9.3 [35, 36]. These channels have high (~ –20 mV) activation threshold [34] and therefore are unlikely to be important for resting membrane potential maintenance but instead are likely to influence AP repolarisation kinetics.

Kv3 is another family of high-threshold Kv channels containing rapidly inactivating (Kv3.3 and Kv3.4) or slowly inactivating (Kv3.1 and Kv3.2) subunits [34, 37]. Expression of multiple Kv3 subunits was detected in DRG with RT-PCR [32] and immunohistochemistry [38] and these can contribute to IKA. Nociceptive C fibres predominantly express Kv3.4 [38]. However, there is no direct evidence as of yet for the functional activity of Kv3 in nociceptors.

Kv4 channels have relatively low activation threshold (-50 to -60 mV) and inactivate rapidly [34, 37]; they are likely to underlie a fraction of IKA in nociceptive neurons. Kv4.1 and Kv4.3 were found in DRG [32, 38-40]; Kv4.3 was consistently found predominantly in nociceptors [38-40] while Kv4.1 is more ubiquitously expressed among DRG neurons of all sizes [40]. Importantly, IKA in small nociceptors was significantly suppressed by overexpression of dominant-negative Kv4 subunit [39] thus confirming expression of functional Kv4 channels in nociceptors and their contribution to the A current. An important feature of Kv4 channels is their rapid recovery from inactivation [34, 39] which, in combination with low activation threshold, results in rapid ‘re-priming’ of Kv4 channels after transient depolarization, thus, allowing them to play significant role in regulating intrinsic excitability of neurons.

Finally, there is another family of voltage-gated K+ channels expressed in nociceptors, Kv7 (KCNQ or M channels). M channels are increasingly recognised as being among the most important regulators of resting membrane potential and AP firing threshold in nociceptors. M channels (Kv7.1 – Kv7.5) conduct very slow (activation and deactivation time constants are in the range of 100-200 ms), non-inactivating K+ currents with a threshold for activation well below -60 mV (can be as low as -80 mV [41]). These properties allow some M channels to remain open at the resting membrane potential of a nociceptor (resting Em in the range of -60 mV [7-9]). This fact, in combination with outwardly-rectifying voltage-dependence of M channels allows them to function as an ‘intrinsic voltage-clamp’ mechanism that controls the resting membrane potential, threshold for AP firing and accommodation within trains of AP (reviewed in [42, 43]). M channels are expressed in DRG cell bodies where they contribute to slow IKDR [44-47]. Functional expression of M channels is also confirmed in peripheral sensory fibres [45, 46, 48-50], dorsal roots/central terminals [51] and nociceptive nerve endings [48]. M channel activity strongly contributes to afferent fibre excitability in vivo [52-56]. Intraplantar injection of the M channel blocker XE991 into the hind paw of rats induces moderate pain [10, 52] while peripheral injections of M channel enhancers (or ‘openers’) such as retigabine and flupirtine produces analgesic effect [10, 45]. There is a debate as to which M channel subunits express in nociceptors most abundantly. Initial report by Passmore and colleagues reported expression of Kv7.2, Kv7.3 and Kv7.5 in nociceptive and non-nociceptive DRG neurons with Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 being predominant subunits. Rose and colleagues later found abundant Kv7.2 expression in small-diameter DRG neurons and non-myelinated fibres [45]. Recent study by Passmore and colleagues found expression of Kv7.2 in nociceptive Aδ and C fibres and their skin terminals [48]. However study [46] found that Kv7.2 is expressed at higher levels in larger, presumably non-nociceptive neurons (and particularly within nodes of Ranvier of myelinated fibres) while small-diameter DRG neuron cell bodies and C fibres to express predominantly Kv7.5. Yet in another study Wladyka and colleagues found that in the nodose afferents (aortic depression nerve) Kv7.5 was expressed in large, myelinated fibres while Kv7.2 was more abundant in C fibres [57]. The reasons for this controversy is yet to be identified however the pharmacological profile of M currents recorded from nociceptive DRG neurons speaks against strong contribution of Kv7.5. In contrast to Kv7.2, Kv7.5 has poor sensitivity to TEA and XE991 but native M currents in DRG neurons display reasonable sensitivity to these blockers, comparable to that expected for Kv7.2, Kv7.3 and their multimers [8, 44, 45, 48, 52]. This however does not exclude Kv7.5 contribution entirely. Regardless of the exact subunit composition, it is clear that nociceptive neurons do express functional M channels which contribute strongly to the control of excitability of these neurons.

Two-pore-domain K+ Channels (K2P, Background K+ Channels)

The expression and functional role of K2P channels in nociceptors has been recently summarized in the inclusive review by Leigh Plant [58] therefore here we only briefly summarize some key findings. K2P channel family (15 KCNK genes in humans) encompasses 4-TMD K+ channel subunits; functional channels are made by the a-subunit dimers [59, 60]. In contrast to Kv channels, K2P gating generally does not display strong voltage-dependence (although their conductance obviously does depend on voltage in accordance to Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz formalism); nevertheless many K2P channels do display variable degree of rectification and time-dependent gating (see [61] for review). Many K2P channels are constitutively open thus generating background ‘leak’ current in neurons which is largely responsible for the maintenance of negative neuronal resting membrane potential (as was suggested by the original theory of neuronal firing, i.e. [62]). Expression of several K2P subunits in DRG have been detected with RT-PCR and immunohistochemical methods; these include TASK-1-3, TREK-1-2, TRAAK, TWIK-1-2 and TRESK [63, 64]. However, which of those are the most functionally active in nociceptors is not entirely clear. One study used single channel patch clamp analysis of the background K+ current in DRG and concluded that TREK-2 and TRESK are most likely to underlie the majority of the background K+ conductance in nociceptors [65].

The unique feature of the K2P channels is that they may serve a double function in sensory neurons. i) Their background activity helps to set negative resting membrane potential. ii) Many K2P channels can respond to temperature, mechanical and chemical stimuli and, thus, they may play a role of primary sensory receptors in peripheral terminals of afferent fibres (reviewed in [58, 61]). Thus, TREK-1 and -2 and TRAAK have been suggested to respond to mechanical and thermal stimuli [61, 66-69]; TASK-1 and -3 are sensitive to acidification [59, 70, 71]. In addition, TASK-1, -3 and TRESK were reported to respond to pungent compound of Szechuan peppers, hydroxyl-α-sanshool [15]. In contrast to other sensory ion channels (such as TRP, P2X and ASICs), K2P channels are inhibited but not activated by the appropriate stimulation. Such inhibition, in turn, results in depolarization of sensory terminal’s membrane potential and can trigger AP firing and generation of a sensory signal.

Other K+ Channels

ATP-sensitive K+ channels (KATP) are heteromeric K+ channels assembled from Kir6.1 or Kir6.2 members of inward-rectifier channel family and regulatory sulfonylurea receptor subunits SUR1 or SUR2 [72]. These channels are inhibited by intracellular ATP thus serving as cellular metabolic sensors. KATP channels were suggested to play a protective role in neurons under pathological conditions (i.e. ischemia) [73]. Expression of Kir6.2, SUR1 and SUR2 in subpopulation of DRG neurons of various sizes has been reported [74]. Moreover, KATP channel enhancers (diazoxide and pinacidil) were shown to hyperpolarize nociceptive neurons and reduce bradykinin-induced pain [75].

Several members of Slo channel family (a name derived from the gene encoding drosophila orthologue of mammalian channel genes) were reported to express in mammalian sensory neurons, particularly nociceptors. Slo channel family in mammals encompasses the Slo1, Slo2.1, Slo2.2 and Slo3. Slo1 is a ubiquitous Ca2+-activated K+ channel also known as BK or Maxi-K channel. Slo2.1 and Slo2.2 are Na+-activated K+ channels while Slo3 is a pH-sensitive large-conductance K+ channel. Slo channels are structurally similar to Kv channels but with two important modifications: i) Slo1 and 3 channels have one additional transmembrane domain (S0) and extracellular N-terminus; ii) their extended C termini host additional regulatory domains, i.e. two RCK domains (regulators of conductance of K+) which form an intracellular gating ring and mediate channel gating by intracellular ligands (reviewed in [76]). Correlative patch-clamp analysis and RT-PCR suggested expression of BK channels consisting of Slo1 and probably b2 auxiliary subunit in many DRG neurons, including small, nociceptive neurons [77]. The major function of BK channels in DRG neurons appears to be shortening of the AP duration, acceleration of repolarisation and contribution to fast after-hyperpolarization [77, 78], effects which limit sensory neuron excitability. Slo2.1 and 2.2 (also called Slack and Slick) mRNA and proteins were found predominantly in small- and medium-diameter DRG neurons and single KNa channels have been recorded in membrane patches excised from those [79-81]. It was suggested that KNa channels in DRG contribute to AP accommodation due to their increasing activation by Na+ influx through the voltage-gated sodium channels during AP firing. It was further hypothesized that PKA-induced internalisation of Slo2.2 channels in DRG neurons contributes to the increased excitability and loss of firing accommodation in hyperalgesia [82].

As it is obvious from the above discussion (and Table 1), nociceptors express a robust and versatile K+ channel ‘toolbox’ which include voltage-gated K+ channels with various kinetic properties, background K+ channels and K+ channels that are operated by various agonists. All this variety is required for setting and controlling parameters of nociceptive neuron’s excitability such as resting membrane potential, AP firing threshold (membrane voltage at which AP is generated) and rheobase (membrane current that is necessary to reach firing threshold), AP kinetics and firing frequency. All these, in turn, define strength and fidelity of peripheral nociceptive signal arriving at the spinal cord. In the next sections we will consider how acute and chronic changes in K+ channel abundance and activity in afferent fibres affect pain transmission and what are the perspectives of therapeutic targeting of peripheral K+ channels for pain relief.

K+ Channels and Neuropathic Pain

Pain is a distressful sensation generated in the brain in response to actual or potential tissue damage. In most (but not all) cases pain originates from the peripheral nociceptive signals, however, such signals not always are produced by noxious stimulation. Indeed, many pathological pains result from injury- or disease-associated changes in nociceptive circuitry which exaggerate or even ‘falsify’ responses to noxious stimuli. Neuropathic pain is defined as “pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system” [83]; it can be caused by injury or degeneration within both peripheral and central pain pathways. Neuropathic pain is characterized by spontaneous and evoked (hyperalgesia and allodynia) pains that often persist over long periods of time (mechanisms of neuropathic pain are reviewed in [84]). Such pains are also hardest to treat as these often respond very poorly to currently available medication [85]. While it is clear that both peripheral and central mechanisms contribute to the development of chronic pain states, sustained pathological overexcitability of nociceptive afferents (also called “peripheral sensitisation”) is often considered to be a trigger. Chronic pain developing after nerve injury or degeneration is known to be associated with prominent morphological and epigenetic changes within the afferent fibres. When peripheral axons are severed by trauma, the proximal nerve stump forms a terminal swelling or endbulb which then sprouts numerous fine processes which may re-connect severed nerve endings. If regeneration is obstructed, endbulb, aborted sprouts and surrounding glia become a bulky tissue formation called a neuroma [86, 87]. Both the neuroma [88, 89] and cell bodies [89-91] of damaged nerves generate anomalous ectopic firing (that is, firing originated proximally to nerve endings) which may cause pain. The mechanisms responsible for this ectopic firing can vary depending on the nature of the disorder and are still under intense investigation. The known processes contributing to peripheral sensitization include inflammatory mechanisms [92], sympathetic sprouting [93, 94] and changes in expression and/or activity of various proteins related to neuronal excitability [84, 95]. Among these later mechanisms, one consistently observed feature is a general downregulation of the K+ channel pool in injured fibres (see Table 2). Early studies reported reduction of both A-type and delayed-rectifier K+ current in DRG of animals after spinal nerve ligation [96, 97]. In subsequent studies it has been widely confirmed that downregulation of expression and activity of various K+ channels is one of the characteristic features of the neuropathic remodelling within the injured/degenerating peripheral nociceptive (and sometimes in non-nociceptive) afferents (Table 2). This ‘negative drive’ affects representative subunits of all major K+ channel families that are expressed in peripheral somatosensory system and, thus, is likely to represent a general phenomenon. Although it is highly likely that this superficially uniform suppression of K+ channels/currents is in fact driven by several distinct mechanisms, what is clear is that this suppression is one of the major causative factors underlying peripheral sensitization of afferent nociceptive fibres and, thus, one of the major factors of persistent pain. As already mentioned, the Mayo Clinic study on the prevalence of pain in patients with potassium channel autoantibodies [20] strongly supports this generalisation.

Table 2.

Downregulation of K+ Channel Expression and Function in Peripheral Somatosensory System in Models of Chronic Pain

| K+ Channel Family |

Chronic Pain Model | Time after Injury | Species | Commentary | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kv1 | Sciatic Nerve Transection | 2 weeks | Rat | Downregulation of Kv1.1, Kv1.2, Kv1.3 and Kv1.4 mRNA in whole DRG | [28] |

| Spinal Nerve Ligation | 7-9 days | Rat | Downregulation of Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 immunoreactivity was observed in large DRG neurons while in small DRG neurons Kv1.4 was downregulated (all by 50-60%) | [31] | |

| Chronic Constriction Injury | 3-7 days | Rat | Downregulation of mRNA levels of Kv1.1, 1.2 and 1.4 in whole DRG | [32] | |

| Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Neuropathy | 3 weeks | Rat | Downregulation of Kv1.4 (but not Kv1.1 or Kv1.2) mRNA level in whole DRG | [107] | |

| Bone Cancer Pain | 2-3 weeks | Rat | Increase in Kv1.4 immunoreactivity and IKA amplitude in DRG neurons | [170] | |

| Kv2 | Chronic Constriction Injury | 3-7 days | Rat | Downregulation of mRNA level of Kv2.2 in whole DRG | [32] |

| Kv3 | Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Neuropathy | 3 weeks | Rat | Downregulation of Kv3.4 mRNA level in whole DRG | [107] |

| Spinal Nerve Ligation | 7 days | Rat | Decrease in Kv3.4 immunoreactivity in small-diameter DRG neurons | [38] | |

| Bone Cancer Pain | 2-3 weeks | Rat | Decrease in Kv3.4 immunoreactivity in DRG neurons | [170] | |

| Kv4 | Partial Sciatic Nerve Ligation | 7-14 days | Mouse | Downregulation of Kv4.3 mRNA in whole DRG | [106] |

| Chronic Constriction Injury | 3-7 days | Rat | Downregulation of mRNA level of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 in whole DRG | [32] | |

| Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Neuropathy | 3 weeks | Rat | Downregulation of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 mRNA level in whole DRG | [107] | |

| Spinal Nerve Ligation | 7 days | Rat | Decrease in Kv4.3 immunoreactivity in small-diameter DRG neurons | [38] | |

| Acetic Acid-induced Chronic Visceral Hyperalgesia | 3-6 weeks | Rat | Downregulation of Kv4.3 protein in DRG containing colon afferents was detected by western blot | [108] | |

| Bone Cancer Pain | 2-3 weeks | Rat | Increase in Kv4.3 immunoreactivity and IKA amplitude in DRG neurons | [170] | |

| Kv7 (M channels) |

Partial Sciatic Nerve Ligation | 2-4 weeks | Rat | Kcnq2 transcript level in whole DRG and Kv7.2 immunofluorescence in DRG cell bodies (predominantly small neurons) were downregulated | [45] |

| Sciatic Nerve Transection | 4 days | Rat | Sharp decrease in Kv7.5 immunoreactivity in the sciatic nerve C fibres |

[46] | |

| Bone Cancer Pain | 2-4 weeks | Rat | Sharp decrease in Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 immunoreactivity, decrease in M current amplitude in DRG neurons | [47] | |

| Saphenous Nerve Transection | 4 weeks | Mouse | Accumulation of Kv7.2 immunoreactivity in the nodes of Ranvier of myelinated fibres within the neuroma | [50] | |

| Kv9 | Spinal Nerve Transection | Detectable at 24 hrs, complete at 3 days | Rat | Rapid downregulation of Kv9.1 mRNA and immunoreactivity in cell bodies of large, myelinated DRG neurons | [36] |

| K2P | Plantar CFA injection | 1-4 days | Rat | Mostly bilateral decrease in the TRESK, TASK-1-3, THIK-2 transcript levels in whole DRG; decrease of the TASK-2 immunoreactivity in ipsilateral DRG | [64] |

| Sciatic Nerve Transection | 3 weeks | Rat | Downregulation of TRESK mRNA in whole DRG | [218] | |

| Ca2+-activated K+ channels | Spinal Nerve Ligation | 2-3 weeks | Rat | Downregulation of K(Ca) currents in acutely-dissociated medium- and small-diameter DRG neurons. Total K(Ca) as well as BK, SK and IK current fractions were reduced in axotomized neuron somata | [219] |

| KATP | Spinal Nerve Ligation | 17-28 days | Rat | Suppressed KATP channel activity in large, acutely dissociated DRG neurons | [220] |

| Spinal Nerve Ligation | 17-28 days | Rat | Downregulation of SUR1 immunoreactivity in predominantly large, myelinated DRG neurons | [74] |

The literature documenting studies on K+ channel suppression in various animal models of neuropathic pain (and some other chronic pain models) is summarized in Table 2. Due to the space considerations we will not discuss each of these studies at length but will consider some examples instead.

Kv7, Kv4 and Transcriptional Suppression by REST

Among the voltage-gated K+ channels, Kv7s or M channels have probably the most negative threshold for activation (below – 60 mV, and as low as -80 in some circumstances [41]; see Table 4 in [34] to compare Kv channel activation thresholds). Thus, for a neuron with resting Em near -60 mV, such a nociceptive neuron, M current should arguably be the most abundant voltage-gated K+ current fraction present at resting conditions. Indeed, in small DRG neurons voltage-clamped at -60 mV a small outward current is observed and this current is almost completely blocked by M channel blocker XE991 and strongly augmented by M channel openers, retigabine and flupirtine [8]. In contrast to K2P ‘leak’ channels, M channels have strong voltage dependence and in contrast to Kv channels underlying IKA, M channels do not inactivate. These features make M current a strong candidate for being one of the main regulators of the resting membrane potential of nociceptors. Therefore, downregulation of M channel expression or suppression of its activity in nociceptive fibres is expected to produce long-lasting overexcitability. Indeed, acute inhibition of M channels in nociceptors does produce nocifensive behaviour [10, 52] and thermal hyperalgesia [48] in rats (see below). Rose and colleagues have recently reported strong down-regulation of Kv7.2 expression (both mRNA and protein) in ipsilateral DRG of rats after the partial sciatic nerve ligation (PSNL) [45] (for more information on animal models of neuropathic pain refer to [84, 98]). Similarly, a significant loss of Kv7.5 immunoreactivity was reported in DRG of rats after the sciatic nerve transection [46]. In accord with previous findings suggesting that augmentation of M current in sensory fibres has an antinociceptive effect [53, 55, 56, 99], Rose and colleagues demonstrated that thermal hyperalgesia produced by neuropathic injury is alleviated by injection of the M channel opener flupirtine directly into the neuroma site in injured rats; the effect was completely prevented by the M channel blocker XE991 [45]. Interestingly, peri-sciatic nerve injection of flupirtine did not significantly affect thermal withdrawal latencies in un-injured rats. The reasons behind this phenomenon are not entirely clear but one possible explanation is that although downregulated elsewhere within the fibres, remaining M channels may actually be pooled at the neuroma nerve stubs as a compensatory mechanism for dampening ectopic firing generated at the neuroma. Indeed, Roza and colleagues reported such accumulation of Kv7.2 at the nerve-end neuroma produced by complete transection of saphenous nerve in mice [50].

Kcnq genes encoding Kv7 subunits have functional repressor element 1 (RE1, NRSE) binding sites which are able to recruit repressor element 1-silencing transcription factor (REST, NRSF) leading to the inhibition of trans-cription of Kcnq2, Kcnq3, Kcnq5 [100] and Kcnq4 [101]. Overexpression of REST in DRG neurons robustly suppressed M current density and increased tonic excitability of these neurons [100]. Baseline REST expression in neurons is low but it was shown to increase greatly following inflammation [100] or after the neuropathic injury [45, 102]. Thus, it appears plausible to suggest that M channel downregulation upon neuropathic injury is mediated by the transcriptional suppression by REST. Indeed, the increase of REST immunoreactivity and transcript level after PSNL mirrored the reciprocal decrease in the immunoreactivity and mRNA level of Kv7.2 [45]. Of note is the fact that both Kv7.2, downregulation and REST upregulation in the latter study only reached statistical significance 4 weeks after the injury while neuropathic pain was evident much earlier. Thus, it appears that in this case Kv7.2, downregulation is likely to contribute to the maintenance rather than the onset of neuropathic pain. According to this hypothesis, REST expression in sensory neurons is induced by trauma and/or inflammation (as suggested in [100]) on or soon after the onset of neuropathic injury. The efficiency of transcriptional suppression of target genes by REST depends on the REST affinity of the individual RE1 sites within these genes and on REST concentration [103]. Therefore the gradual increase of REST expression after nerve injury can cause a successive knock-down of its target genes in accordance with the REST affinity of their RE1 site. Another transcriptional mechanism for regulation of Kcnq expression has been recently identified by Zhang and Shapiro [104]. In this study it has been demonstrated that Kcnq2 and Kcnq3 are positively regulated by nuclear factor of activated T cell (NFAT) in an activity-dependent manner. NFAT expression has been shown to increase in DRG neurons following nerve injury [105], therefore, transcriptional regulation of Kcnq genes during neuropathic remodelling of peripheral fibres may exhibit a complex pattern as there is a basis for both negative (by REST) and positive (by NFAT) regulation. It should be noted however that positive regulation of Kcnq genes has been reported for NFATc1/NFATc2 isoforms [104] while it is NFATc4 which displayed sustained upregulation in DRG after the nerve injury [105]. Therefore, the relevance of the NFAT pathway for Kcnq gene regulation in neuropathic pain is yet to be established.

Neuropathic pain-associated suppression by REST was also suggested as a mechanism for downregulation of another prominent Kv subunit expressed in nociceptors, Kv4.3 [106]. Similarly to Kv7 channels, Kv4.3 also contains a REST binding site and Kv4.3 downregulation correlated well with the increase in REST following the PSNL injury [102, 106]. In these studies the effect developed faster than that reported in [45] as Kv4.3 expression reached its minimum at 7 days after injury. The downregulation of Kv4 channels in various models of chronic pain is very well documented [32, 38, 106-108] and it is likely to underscore

decreased A current density in nociceptors following nerve injury. It is tempting to suggest that REST may indeed orchestrate (or at least contribute to) the neuropathic remodelling of somatosensory neurons as there are many other genes that are subject to regulation by this transcriptional suppressor (see [103] for review). Thus, downregulation of Nav1.8 voltage-gated Na+ channels and µ-opioid receptors by REST following neuropathic injury has also been reported [102]. Although the downregulation of Nav1.8 is not excitatory on its own, it may contribute to overall phenotypic switch within the somatosensory fibres in neuropathy.

Kv2 and Silent Kv Subunits

A fraction of high-threshold delayed-rectifier current in sensory neurons is mediated by Kv2.1 and Kv2.2 channels, either on their own or in complexes with silent Kv subunits 9.1 and 9.3 [35, 36]. Some downregulation of Kv2.1 [109] and Kv2.2 [32] following axotomy has been reported, however more robust effect has been found for the case of Kv9.1 [36]. This Kv subunit (often together with Kv2.1 and Kv2.2) was found mostly in myelinated fibres (Aδ and Aβ) and their cell bodies. Strikingly, Kv9.1 mRNA and protein were rapidly downregulated following spinal nerve transection in rats; the downregulation was already prominent 24 hrs after injury and was complete within 7 days. This rapid onset of the effect correlates well with the development of neuropathic hyperalgesia in this model of pain [91] suggesting that, in contrast to the case of Kv7 and Kv4 channels described above, downregulation of Kv9.1 may contribute to the onset of neuropathic pain. In support for the role of Kv9.1 in the development of neuropathic pain, in vivo knock-down of Kv9.1 by intrathecal siRNA induced mechanical hyperalgesia similar to that produced by injury. It was suggested that the hyperexcitability of both Aδ (mostly nociceptive) and Aβ (mostly non-nociceptive) fibres mediated by the Kv9.1 downregulation can contribute to the peripheral sensitization as indeed ectopic activity following nerve injury is consistently observed in A fibres [110, 111]. What remains unresolved though is the exact mechanism by which downregulation of Kv9.1 excites somatosensory fibres. Kv9.x are silent subunits that conduct no K+ current when expressed on their own but are able to multimerize with several other Kv subunits modulating their gating [112]. However, coexpression of Kv2.1 with Kv9.1 in Xenopus oocytes resulted in more than 70% reduction in current amplitude and facilitation of inactivation of Kv2.1 current [113]. Thus, if Kv9.1 is indeed multimerizes with Kv2.1 in sensory fibres as suggested [36], then Kv9.1 downregulation would be expected to enhance Kv2.1 current, not inhibit it. While there are certain biophysical conditions upon which K+ channel inhibition actually reduces excitability (i.e. by producing depolarization that inactivates voltage-gated Na+ channels or by slowing down AP repolarization thus reducing the firing rate), clearly further research is needed to fully elucidate the role of Kv9.1 in somatosensory neuron excitability.

K+ Channels and Inflammatory Pain

Inflammatory pain is usually pictured as a group of mechanisms placed between the acute, physiological pain (a healthy reaction of the body to harm) and chronic/neuropathic pain (a pathological pain state) and it has a significant overlap with the both [86]. Inflammation is a complex immune response that occurs in reaction to tissue damage (i.e. wound or infection), which is aimed at removing the harmful stimuli (e.g. eliminating infectious bacteria) and promoting tissue regeneration. Immunological mechanisms underlying the inflammatory responses are robust and versatile but these are outside the scope of this review. A common feature of inflammatory responses though is that these are coordinated by a wide range of chemical factors, which are released into the extracellular space by damaged tissue, recruited immune cells and even by the afferent sensory fibres innervating the inflamed tissue (the later phenomenon is known as ‘neurogenic inflammation’). These factors are often called ‘inflammatory mediators’ and these are key triggers of the inflammation ‘side effect’ – inflammatory pain. The inflammatory mediators are incredibly diverse: prostaglandins, leukotriens, interleukins (and numerous other cytokines and chemokines), bradykinin, substance P, ATP, growth factors, proteases, protons, nitric oxide (NO), and many others; all of these can be found in the inflamed tissue under various conditions (reviewed i.e. in [114, 115] and elsewhere). Many inflammatory mediators (e.g. bradykinin, histamine, 5-HT) have long been known as endogenous pain-inducing substances or algogens [116] that can directly excite or sensitize the peripheral terminals of nociceptive afferents. The excitatory mechanisms of inflammatory mediators (including their effects on ion channels) are widely discussed and several recent reviews are available [16, 117, 118]. Therefore here we will only discuss known mechanism involving K+ channels (which are few).

When considering inflammatory pain mechanisms, most attention in current research is given to the mechanisms of activation or ‘sensitization’ by inflammatory mediators of various ion channels that can acutely depolarize nociceptors. These include various TRP channels, i.e. TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPV4, TRPA1, TRPM8 (as discussed at lengths in many recent reviews, i.e. [119-122]), ASICs [123-126], P2X receptors [127-132] or tetrodotoxin-resistant voltage-gated Na+ channels Nav1.9 and Nav1.8 [133-137]. However, as schematized in Fig. (1) and exemplified throughout this review, both acute and long-term hyperexcitability and over-sensitivity of afferent fibres can be also produced by inhibition/downregulation of K+ channel activity. The examples of the inflammatory mechanisms where this was clearly demonstrated experimentally are sparse but nevertheless few cases can be made and, again, most of them involve M channels.

Kv7 channels have been named ‘M’ for their sensitivity (inhibition) to muscarinic acetylcholine receptor stimulation [138]. In the three decades that followed the discovery of M current by David Brown and Paul Adams, M channels have become a classical example of an excitatory action of G protein coupled receptors that act via Gq/11 type of Gα subunits (reviewed in [42, 139, 140]). The most studied receptors of this type (at least in relation to M channel regulation) are muscarinic M1 and bradykinin B2 receptors. The signaling cascade triggered by the receptors of this type involves activation of phospholipase C (PLC) which hydrolyzes the plasma membrane phospholipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to produce diacylglycerol (DAG) and releases inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) into the cytosol. DAG can activate protein kinase C or be further metabolized to produce other signaling molecules such as phosphatidic and arachidonic acids, while IP3 can activate IP3 receptors within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and induce Ca2+ release from the ER (reviewed in [141]). M channels are inhibited by both PIP2 depletion [142-144] and ER Ca2+ release [145-148]; moreover, PKC phosphorylation sensitize M channels to PIP2 depletion [149, 150]. As already discussed above, M channels are expressed throughout the peripheral nociceptive fibres and their activity strongly correlates with the excitability of these fibres [8-10, 48, 52-56]. Further-more, injection of XE991 into rat’s hind paw on its own produced spontaneous nocifensive behaviour [10, 52]. Coincidently, receptors of many inflammatory mediators are coupled to the very same Gq/11-PLC signalling pathway as the above mentioned M1 and B2 receptors; many of these receptors are prominent in peripheral nociceptors and are known to be able to excite them. Among those receptors are the B2 receptors themselves [151], histamine H1 receptors [152], protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2) [153], prostaglandin EP1 [154], purinergic P2Y [155] and many other receptors (reviewed in [16]). Accordingly, stimulation of nociceptive neurons by bradykinin (an endogenous peptide that has been called “the most potent endogenous algogenic substance known” [156]) [8, 10] strongly inhibited M current and produced excitability which was mimicked by M channel blocker XE991 and antagonised by M channel enhancer flupirtine. Similarly, M channels in small DRG neurons are inhibited by PAR-2 [52] and MrgD [157] receptor triggering. Recent study demonstrated that M channels in trigeminal nociceptors can also be inhibited by NO via S-nitrosylation at the redox sensitive module within the cytosolic loop between S2 and S3 TMDs [158]. NO-mediated M channel inhibition correlated with increased excitability and CGRP release in nociceptors and was suggested to contribute to excitatory effects of NO in such trigeminal disorders as headache and migraine [158]. Thus, current evidence strongly suggest that acute M channel inhibition by signalling cascades triggered in nociceptive fibres by inflammatory mediators contributes to acute inflammatory nociception and pain.

The evidence of direct involvement of other K+ channels in inflammatory pain is limited. It is reasonable to hypothesize that another family of K+ channels that can be directly modulated by the inflammatory mechanisms is the K2P channel family as these channels have a very rich profile of regulatory mechanisms, some of which are directly related to inflammation. Thus, TASK channels expressed in DRG neurons are inhibited by acidification [159, 160], which is a common tissue condition produced by inflammation [161]. Moreover, many K2P channels are inhibited by Gq/11 [162-165] or Gs [66, 166] pathways (reviewed in [61]). K2P inhibition by the Gq/11-coupled group I metabotropic glutamate receptors has been shown to produce slow and long-lasting excitation of CNS neurons [164]. Thus, it would be logical to hypothesize that receptor-mediated inhibition of background K+ channels in nociceptors could contribute to the inflammatory pain in a way mechanistically similar to that involving M channels.

In some diseases (i.e. arthritis, chronic infections etc.) inflammation can become chronic, so is the inflammatory pain associated with it. Like in the case of neuropathic pain, chronic inflammation is associated with some remodelling and with long-lasting changes in the gene expression within the afferent fibres innervating the inflamed tissue [167]. The changes in K+ channel expression profile under the conditions of chronic inflammation have not been investigated systematically and only a handful of observations exist. Thus, transcript levels of several K2P channels (see Table 2) and TASK-2 protein were downregulated in DRG of rat in chronic inflammation model (hind paw injection of complete Freund’s adjuvant, CFA) [64]. Forty eight hrs incubation of cultured DRG neurons with a cocktail of inflammatory mediators reduced M current density and Kv7.2 expression (an effect that is likely mediated by REST as it’s expression was stimulated in the same cultures) [100]. Likewise, 48 hrs treatment of cultured DRG with TGFβ induced reduction in A current and downregulation of Kv1.4 transcript and protein level in DRG, a mechanism that was suggested to play a role in the development of pancreatic hyperalgesia in chronic pancreatitis [168].

K+ Channels and Cancer Pain

Pains triggered by tumors are caused by unique combination of inflammatory, neuropathic, ischemic, and compression mechanisms as well as by the cancer cell chemical signalling [169]. As such, cancer pain is a very heterogeneous pathology which is difficult to model in animals. Thus far only few studies testing role of K+ channels in cancer pain were published. Thus, Zheng and co-authors reported strong downregulation of both Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 M channel subunits in DRG neurons 2-4 weeks following the induction of experimental bone cancer pain in rats [47]. This effect was accompanied by marked decrease in the amplitude of M currents recorded from the neurons acutely isolated from the DRG of cancer animals as compared to that of control rats. Importantly, application of retigabine inhibited the bone cancer-induced hyper-excitability of acutely isolated small DRG neurons and alleviated mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in rats with bone cancer. These results are very close to the findings of Rose and colleagues reporting downregulation of Kv7.2 in a neuropathic pain model [45]. Both studies suggest that despite the decreased abundance of M channels in nociceptors affected by a chronic pain condition, the remaining M channels can still be effectively targeted by the pharmacological enhancers in order to reduce nociceptor excitability. Another study that also used rat bone cancer pain model found more complex changes in the K+ channel expression in DRG nociceptors [170]. Thus, A-type K+ current subunits Kv1.4 and Kv4.3 were found upregulated 2-3 weeks after the bone cancer pain induction while Kv3.4 was strongly downregulated. Electrophysiological recordings from the acutely-dissociated DRG neurons demonstrated that the development of the bone cancer pain was associated with the increase in total amplitude of IKA while IKDR declined (the later observation is consistent with the downregulation of the delayed rectifier K+ channels such as M channels). As mentioned above, cancer pain has a very complex etiology; it therefore would not be surprising if functional changes in peripheral afferents observed in cancer pain models would have more complex pattern as compared with that in models of neuropathic or inflammatory pain.

K+ Channels as Prospective Analgesic Drug Targets

As this review emphasizes, multiple K+ channel deficiencies represent general source of overexcitability within the peripheral pain pathways. Moreover, in general sense, activation of a K+ current in most neurons is likely to provide an anti-excitatory effect regardless of the source of overexcitability. Therefore it does not take much to suggest that pharmacological K+ channel enhancement could be utilised as a strategy for management of pain. Indeed, a lot of work, predominantly in industry, has been undertaken in recent years in order to identify and optimize such enhancers (or openers) and to validate their potential in treatment of pain. These programs thus far mostly focused on M channels [171].

Before we briefly outline current literature on M channel openers, let us first consider some important questions about suitability of K+ channels within the peripheral pain pathways as analgesic targets. i) Does targeting of K+ channels offers any benefits comparing to other analgesic drug targets? ii) Is it possible to specifically target peripheral K+ channels without affecting CNS? iii) Can desirable level of selectivity be achieved? In our opinion, the first question can arguably be answered positively. Indeed, in contrast to simply blocking AP firing (i.e. as with voltage-gated sodium channel blockers such as lidocaine) or synaptic transmission from the periphery to CNS (as with voltage-gated Ca2+ channel blockers such as ziconotide), reasonable augmentation of K+ channel activity should not shut down afferent excitability completely but rather ‘reset’ it to a higher threshold. Therefore, targeting peripheral K+ channels can, at least in theory, restore normal sensitivity of overexcitable nociceptive pathways instead of completely blocking them. Potentially, such a strategy should also be less prone to produce motor deficit which often accompany action of local analgesics. Second and third questions are, however, difficult to answer in general terms but these have to be taken into consideration in testing particular ion channel drug targets.

Cloning of Kv7-encoding KCNQ genes [172] and subsequent identification of KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 mutations that underlie a form of epilepsy, human benign familial neonatal convulsions (BFNC) [173-176] has immediately put Kv7 channels on the map of prospective drug targets for the treatment of neuronal hyperexcitability disorders. Initially these included epilepsies; however identification of functional M channels within nociceptive pathways [44] soon added other neuronal hyperexcitability disorders, such as migraine and chronic pains, as other possibilities (reviewed in [171, 177]). In June 2011 an M channel opener retigabine (ezogabine) has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the adjunctive treatment of partial-onset seizures in adults [178].

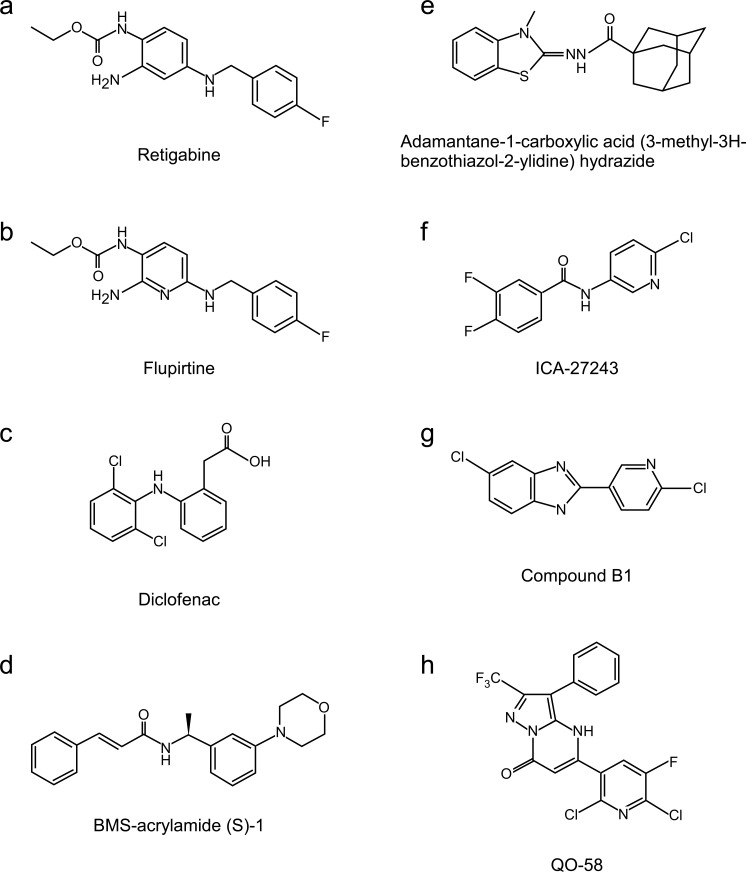

While successful in treatment of epilepsy, the perspectives for retigabine in treatment of pain are still unclear. Thus, results from phase IIa proof-of-concept clinical trial for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia pain were inconclusive [179]. Nevertheless, it is important to point out that long before the cloning of KCNQ channels and elucidation of the anti-excitatory mechanism of retigabine, its very close chemical analogue, flupirtine (branded as Katadolon, Awegal etc. see Fig. 2a, b) has been used as a non-opioid analgesic [171, 180]; it actually became first available in Europe in 1984. Although selectivity of flupirtine is questionable, it is believed that it is mainly its M channel opener activity that underscores analgesic efficacy of flupirtine [181]. Flupirtine effectively reduces postoperative pain, chronic musculoskeletal pain, migraine and neuralgia [180, 181]. As discovered recently, some of the well-known non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as diclofenac (Fig. 2c) [182] and celecoxib [183, 184] also possess strong M channel opener activity, which can be responsible for at least some of their analgesic efficacy. Thus, despite the lack of clarity with the perspectives of retigabine as analgesic, there is obviously a lot of room for the development of M channel opener-based pain therapeutics and indeed new openers show good results in animal models [185]. Another important point to make is that thus far the M channel openers were tried almost exclusively (at least to what is disclosed) as systemically administered small-molecule drugs. Since M channels are abundantly expressed throughout the CNS, there are obvious limitations and safety issues which potentially can be reduced if an opener would not be able to cross the blood-brain barrier and only acted peripherally.

Fig. (2).

Structures of some of M channel openers discussed in this review.

Since identification of retigabine as an M channel opener [186, 187], hundreds if not thousands (study [188] alone reports screening of over 600 unique openers) new M channel openers have been identified or synthesized in a number of large screens conducted by several major companies such as Bristol-Myers Squibb, Icagen (now Neusentis), Abbot Laboratories and NeuroSearch [185, 188-192] and by efforts in academic laboratories [193-195]. Due to large number of compounds produced and limited public disclosure of their properties, we will only briefly outline some key developments in the field. An excellent overview of the development of M channel openers for treatment of pain (as of 2008) can be found in [171].

Triaminopyridines

Triaminopyridines (retigabine and flupirtine, Fig. 2a, b) are relatively non-specific M channel openers that activate all Kv7 subunits except of Kv7.1. Kv7.3 is the most sensitive to their action [186, 196-198]. Retigabine binding site is situated within the S5 TMD of Kv7 channels; it contains a critical residue W236 (in Kv7.2) that is necessary for retigabine effect and that is absent in Kv7.1 [196, 197]. Triaminopyridines induce large negative shift in channel voltage dependence (over -30 mV for retigabine acting at Kv7.2/Kv7.3) and also augment maximal steady-state K+ conductance at saturating voltages [8, 186, 196-198]. Flupirtine injections into neuroma site of neuropathic rats reduced thermal hyperalgesia [45]; likewise, hind-paw injection of retigabine alleviated bradykinin-induced pain [10]. Systemic administration of retigabine also showed analgesic efficacy in various pain models such as temporomandibular joint pain [199], visceral pain [54] and carrageenan-induced hyperalgesia [44].

Acrylamides

Acrylamides known as compounds (S)-1, (S)-2 etc. were synthesized in Bristol-Myers Squibb (Fig. 2d) [190, 191, 200, 201]. These compounds apparently share the same site of action and, therefore, the same specificity profile as retigabine [202]. Acrylamides demonstrated activity in the cortical spreading depression model of migraine [191].

Adamantyl Derivatives

Adamantyl derivatives (Fig. 2e) were recently identified by Icagen as potent (EC50 < 1 µM) activators of Kv7.2/Kv7.3 channels with about 100 fold selectivity against Kv7.1/KCNE1 channel [185]. Several compounds of this family demonstrated efficacy in reducing phase II of formalin-induced pain and also strongly reduced tactile allodynia in spinal nerve ligation model of neuropathic pain [185]. The site and mechanism of action of these compounds as well as selectivity against other members of Kv7 family were not reported.

Benzanilides

ICA-27243 (N-(6-chloro-pyridin-3-yl)-3,4-difluoro-benzamide) is another Kv7.2/Kv7.3 opener developed by Icagen (Fig. 2f). It is orally bioavailable and demonstrates better selectivity for Kv7.2/7.3 channels vs. Kv7.4 or Kv 7.3/7.5 heteromultimers as compared to retigabine [203]. ICA-27243 did not have significant effects on several other ion channels including GABAA and voltage-gated Na+ channels (NaV1.2). This differentiates the compound from retigabine, which was reported to affect GABAA currents [204]. ICA-27243 has its own binding site within Kv7 channels which is distinct from that of triaminopyridines and acrylamides and resides within the voltage-sensor domain of the channel [205]. A series of closely-related compounds (‘ztz series’) was identified in another study [195].

Benzimidazoles

A group of compounds related to ‘compound B1’ (Fig. 2g) has been recently identified by Abbot Laboratories [188]. A striking feature of these compounds is their high selectivity for Kv7.2. Several derivative compounds had EC50 for Kv7.2 around 2-3 µM and slightly higher values for Kv7.2/Kv7.3 but were completely inactive at Kv7.3, Kv7.4 and Kv7.5. Such selectivity is an attractive feature as it may help to avoid possible side effects of activating Kv7.4, which is the main Kv7 channel expressed in the vasculature [206] and also in the auditory pathways [207, 208]. The action of these compounds on Kv7.1 was not reported. Similarly to ICA-27243, benzimidazoles do not require W236 for their action on Kv7 channels [188].

PPO (QO) Series

Several derivatives of pyrazolo 1,5-a pyrimidin-7(4H)-one (PPO) were synthesized by Hailin Zhang’s group and characterized as potent but not very selective Kv7 openers [209-211]. The QO compounds have EC50 values in the range of 2-10 µM and activate Kv7 channels mainly by negative shift of channel voltage dependence; the compounds also significantly slowed channel kinetics. The lead compound QO-58 (Fig. 2h) is probably the most efficacious compound reported to date in terms of its ability to shift Kv7 channel voltage dependence towards more hyperpolarized potentials. Thus, for Kv7.2 and Kv7.4 such shift almost reached a value of -60 mV [211]. QO-58 enhanced currents of all Kv7 subunits except of Kv7.3; it showed highest efficacy at Kv7.4. The site of action of PPO compounds is different from that of retigabine but is similar (but not identical) to that of ztz compounds [195, 211]. QO-58 significantly reduced mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in chronic constriction injury of sciatic nerve model of neuropathic pain [211].

N-phenilanthranilic Acid Derivatives

Two NSAIDs, meclofenamic acid and diclofenac (Fig. 2c), act as Kv7.2/Kv7.3 openers [182]. Attali group has synthesized several other N-phenilanthranilic acid derivatives which also act as such. Thus, NH6 [212] and NH29 [213] activate Kv7.2 and Kv7.2/Kv7.3 channels with EC50 ~15 µM and do not activate Kv7.1 or Kv7.1/KCNE1 channels. NH6 was also inactive against Kv1.2, Kv1.5, Kv2.1 channels, AMPA and GABAA receptors. NH29 weakly activated Kv7.4. Both compounds, like retigabine, induced hyperpolarizing shift in channel voltage dependence but, unlike retigabine, NH29 did not require W236 for action but acted on the voltage-sensor domain of the channel [213]. NH compounds effectively reduced excitability and synaptic transmission of central (hippocampal) and peripheral (DRG) neurons [212, 213].

Other Chemical Mechanisms of Kv7 Enhancement

Zinc pyrithione (ZnPy) has been reported to strongly potentiate all Kv7 channels except Kv7.3 [193]. The action of ZnPy is independent of W236 [193]. Kv7 channels possess several reactive cysteines that can be chemically modified to induce augmentation of channel activity. Thus, cysteine-modifying agent N-ethylmaleimide, acting at the C-terminal cysteines homologous to position 519 in Kv7.4, strongly augmented currents of Kv7.2, Kv7.4 and Kv7.5 but did not act on Kv7.1 or Kv7.3 [148, 214, 215]. Oxidative modification of triplet of cysteines at positions homologous to 156-158 in Kv7.4 (cytosolic S2-S3 linker) also strongly augments Kv7 currents in the same pattern [194]. Interestingly, the same triplet of cysteines can be S-nitrosylated, which reduces channel activity [158]. In contrast to many other openers, oxidative modification produces relatively small (as compared to retigabine) negative shift of channel voltage dependence but induces large increase of steady-state current at saturating voltages [8, 194]. Recently the reactive oxygen species-mediated augmentation of M current was suggested to contribute to anti-excitatory action of substance P in peripheral nociceptive neurons [9].

Can Other K+ Channels in Nociceptors be Targeted for Analgesic Purposes?

Although most of the work on K+ channels as analgesic drug targets has been carried out with Kv7 channels, mechanistically, other K+ channels which are expressed in nociceptors at sufficient levels can also be targeted (at least theoretically). In support of this hypothesis, recent study has demonstrated that peripheral injections of two KATP channel openers, pinacidil and diazoxide reduced bradykinin-induced pain and hyperalgesia in rats [75]. In addition, some general anesthetics (i.e. chlorophorm and isoflurane, reviewed in [61, 216]) are K2P channel openers and K2P channel enhancement in CNS is believed to contribute to anesthetic action of these drugs. Nevertheless, Kv7 channels do offer some advantages over the other K+ channels. i) As discussed above, biophysical properties of Kv7s are such that these channels are expected to exert a very strong control over the resting membrane potential and firing threshold of nociceptors; ii) in contrast to many other K+ channels (KATP, K2P, some Kvs), Kv7.2, Kv7.3 and Kv7.5 are predominantly (although not exclusively) neuronal. Cardiac and epithelial tissues abundantly express Kv7.1 [217] and Kv7.4 is abundantly expressed in the vasculature [206], nevertheless, as we have discussed, it appears possible to design Kv7 openers that would not activate Kv7.1 and Kv7.4. A potential limitation of the current strategies involving M channel openers is that these exclusively focus on small molecules that can be applied systemically and that cross blood-brain barrier easily. Such a property is certainly a requirement for the use of M channel openers as anti-epileptic drugs, as in the case of epilepsy the source of spurious excitability is in the brain. However, when targeting pain, the source of pathological excitability is often resides within the peripheral nervous system. Thus, central action of an opener may not necessarily be beneficial. Indeed, it seems logical to suggest that an opener that is selective for Kv7.2/Kv7.3 (and maybe Kv7.5) and that penetrates the blood-brain barrier poorly can be relatively safely applied at a dose necessary to dampen peripheral excitability. However such a drug is yet to be found.

Conclusions, Perspectives

Research in many laboratories worldwide established several key facts regarding the expression, function and role in pain of major K+ channels subunits. These include i) basic characterization of K+ currents and subunits expressed in nociceptors; ii) establishment of downregulation of K+ current density/ K+ channel expression as a general phenomenon that is commonly observed with the development of chronic pain; iii) discovery of the analgesic activity of K+ channel openers. These conceptual findings laid out a foundation for the hypothesis that considers ‘potassium channelopathy’ as a core feature of many types of pain. However there is still some way to go before this hypothesis is generally proven and acted upon. Firstly, the down-regulation of K+ channel expression and functional activity detected at the cell bodies of nociceptive neurons has to be extensively tested at the level of peripheral fibres and terminals. Secondly, the heterogeneity of nociceptors makes it difficult to establish any general rules and more research is needed to elucidate patterns of K+ channel expression in various subpopulations of nociceptors. Thirdly, we are still only starting to discover mechanisms that control K+ channel abundance (epigenetic regulation, trafficking, posttranslational modifications etc.) in healthy and diseased nociceptive afferents. The latter consideration is particularly important for meaningful targeting of K+ channels in therapeutic purposes. Indeed, if a given K+ channel is downregulated in a chronic pain state, then its pharmacological opener is unlikely to be very efficacious even though it shows great results in the expression system or acute pain tests. May be in such cases a more fruitful approach would be to try to prevent or revert K+ channel downregulation in the first place. Finally, up until now the attempts to use K+ channel targeting drugs in treatment of pain can be characterized more or less as a ‘shotgun approach’ whereby multiple K+ channel subunits in CNS and PNS are targeted with systemically applied drugs. Clearly, more selective targeting is required (and the proliferation of M channel openers suggests that such approaches could indeed be developed). We hope that better understanding of the mechanisms of peripheral excitability and the roles that K+ channels play in it will help to develop smarter analgesics in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Professor Hailin Zhang for helpful comments. Research in our laboratories is supported by MRC, (G0700966, G1002183) and NSFC (30500112).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Raouf R, Quick K, Wood JN. Pain as a channelopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:3745–3752. doi: 10.1172/JCI43158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathie A. Ion channels as novel therapeutic targets in the treatment of pain. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2010;62:1089–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2010.01131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peier AM, Moqrich A, Hergarden AC, Reeve AJ, Andersson DA, Story GM, Earley TJ, Dragoni I, McIntyre P, Bevan S, Patapoutian A. A TRP channel that senses cold stimuli and menthol. Cell. 2002;108:705–715. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor a heat activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coste B, Mathur J, Schmidt M, Earley TJ, Ranade S, Petrus MJ, Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science. 2010;330:55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1193270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sindrup SH, Graf A, Sfikas N. The NK1-receptor antagonist TKA731 in painful diabetic neuropathy a randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Pain. 2006;10:567–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sapunar D, Ljubkovic M, Lirk P, McCallum JB, Hogan QH. Distinct membrane effects of spinal nerve ligation on injured and adjacent dorsal root ganglion neurons in rats. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:360–376. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200508000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linley JE, Pettinger L, Huang D, Gamper N. M channel enhancers and physiological M channel block. J. Physiol. 2012;590:793–807. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.223404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linley JE, Ooi L, Pettinger L, Kirton H, Boyle JP, Peers C, Gamper N. Reactive oxygen species are second messengers of neurokinin signaling in peripheral sensory neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E1578–E1586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201544109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu B, Linley JE, Du X, Zhang X, Ooi L, Zhang H, Gamper N. The acute nociceptive signals induced by bradykinin in rat sensory neurons are mediated by inhibition of M-type K+ channels and activation of Ca2+-activated Cl- channels. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:1240–1252. doi: 10.1172/JCI41084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]