Abstract

In congenital Chuvash polycythemia (CP), VHLR200W homozygosity leads to elevated hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) levels at normoxia. CP is often treated by phlebotomy resulting in iron deficiency, permitting us to examine the separate and synergistic effects of iron deficiency and HIF signaling on gene expression. We compared peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles of eight VHLR200W homozygotes with 17 wildtype individuals with normal iron status and found 812 up-regulated and 2120 down-regulated genes at false discovery rate 0.05. Among differential genes we identified three major gene regulation modules involving induction of innate immune responses, alteration of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, and down-regulation of cell proliferation, stress-induced apoptosis and T-cell activation. These observations suggest molecular mechanisms for previous observations in CP of lower blood sugar without increased insulin and low oncogenic potential. Studies including 16 additional VHLR200W homozygotes with low ferritin indicated that iron deficiency enhanced the induction effect of VHLR200W for 50 genes including hemoglobin synthesis loci but suppressed the effect for 107 genes enriched for HIF-2 targets. This pattern is consistent with potentiation of HIF-1α protein stability by iron deficiency but a trend for down-regulation of HIF-2α translation by iron deficiency overriding an increase in HIF-2α protein stability.

Introduction

Hypoxia [1] and iron [2] modulate many metabolic processes. Chronic and acute hypoxia cause morbidity and mortality associated with pulmonary and brain edema [3], pulmonary hypertension [4] and aberrant metabolism [5; 6; 7]. Hypoxia has multiple effects on the expression of a vast array of genes, but this has been almost entirely investigated in vitro [8] or in experimental animals [9]. Iron deficiency is a common nutritional disorder, and it enhances pathways that are associated with hypoxia as iron is required for optimal activity of prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) that are principal negative regulators of hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs) [10; 11]; iron deficiency also has hypoxia-unrelated metabolism-regulating roles [12; 13; 14; 15; 16]. Investigating the relationship between gene expression and the nutritional environment is important for understanding the complications of genetic disorders and for the development of optimal personalized approaches to medical care [17].

To better understand the pathological processes associated with hypoxia and to develop targeted intervention for disease states associated with hypoxia, we elected to define the hypoxia- and iron-related regulation of genes in humans in vivo by taking advantage of a congenital disorder of up-regulation of the hypoxic response at normoxia. Chuvash polycythemia (CP) is an autosomal recessive form of polycythemia/erythrocytosis that is endemic to the mid-Volga River region in the Russian Federation [18] and is characterized by increased levels of HIFs during normoxia [19]. Furthermore, CP is often accompanied by iron deficiency due to therapeutic phlebotomies, allowing us to weigh the effect of this common nutritional and environmental variable on hypoxic gene expression.

HIF-1 and HIF-2 are transcription factors that serve as master regulators of the hypoxic response. With normal oxygen tension, von Hippel Lindau (VHL) protein binds to HIF-α subunits and labels them for degradation by proteasomes. Proline hydroxylation of HIF-α by PHD enzymes is required for the interaction of HIF-α with VHL protein [20; 21]. Both oxygen and iron are needed for the activity of PHDs. Low oxygen inhibits VHL binding to HIF-α and activates HIF-dependent transcriptional responses, including increased erythropoiesis, angiogenesis, and a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis for ATP generation. HIF-1α and HIF-2α may have complimentary but in some contexts also opposite effects on distinct gene targets depending on tissue- and cell-types [22; 23]. Iron deficiency also has the potential to exacerbate the hypoxic response due to its effect of impairing the activity of PHDs. Consistent with this possibility, iron chelating drugs post-translationally increase the α subunits of HIFs in cultured cells [10; 11], likely via PHD inhibition and apparently overriding a possible confounding effect of lack of iron in decreasing HIF-2α translation by promoting iron response proteins [24].

CP is characterized by a homozygous 598C>T (Arg200Trp or R200W) germline missense mutation in the VHL gene [19; 22], which leads to impaired activity of VHL protein to initiate ubiquitination and ultimately degradation of HIF-1α and HIF-2α. Patients with CP have increased levels of HIF-1 and HIF 2 during normoxia; this leads to altered expression of a large array of HIF-target genes, still not fully defined, and clinical manifestations that have so far been shown to include elevated hematocrit, lower systolic blood pressure (SBP) and enhanced risk of hemorrhage, thrombosis, pulmonary hypertension and other complications [25; 26]. In CP subjects iron deficiency would be predicted to further increase HIF-1α and HIF-2α and augment the increased HIF activity that occurs due to the genetic loss of VHL function [19; 20]; however, the opposite effect on HIF-2α mediated by its 5’ iron responsive element [24] is also possible. The study of CP subjects might further clarify the role of iron deficiency in manifestations of the hypoxic response.

In this study we compared gene expression variation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) between 24 VHLR200W homozygotes and 21 Chuvash VHL wildtype controls. Those VHLR200W homozygotes on a therapeutic phlebotomy are almost universally iron deficient. We therefore selected 17 healthy Chuvash VHL wildtype (WT) and 8 VHLR200W homozygotes matched for serum ferritin concentration, and identified 2932 differentially expressed genes and related biological pathways attributable to the VHLR200W mutation. We found that iron deficiency affected VHLR200W induced gene expression possibly by distinct mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects

The Howard University IRB committee approved the protocol and each participant gave written informed consent. Twenty-one healthy Chuvash VHL wildtype (WT) control individuals and 24 Chuvash VHLR200W homozygotes were recruited. The complete blood count was determined by an automated analyzer (Sysmex XT 2000i, Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Hyogo, Japan), serum ferritin, serum erythropoietin (EPO), and plasma vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) concentrations by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Ramco Laboratories Inc., Stafford, TX and R& D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

RNA Isolation and Expression Profiling

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from EDTA whole blood Ficoll-Hypaque (GE, Pittsburgh, PA) density gradient centrifugation, washed with PBS, re-suspended in Ambion RNAlater (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) solution, frozen at −80°C and shipped in liquid nitrogen from Cheboksary (Chuvashia, Russia) to Howard University. RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, CA) and the quality was assessed using nanodrop (Thermoscientific, Waltham, MA) and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Total RNA was submitted to the University of Chicago Functional Genomics Center for whole transcript sense target labeling assay (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA), hybridization to the Affymetrix GeneChip™ Human Exon 1.0 ST Array, and washing and scanning according to the manufacturer's procedure (Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA).

Microarray data preprocessing

All 25mer probe sequences were aligned to human genome assembly GRCh37 allowing ≤ 2 mismatches [27]. Probes with perfect unique match to the genome were selected. We further removed probes that interrogate multiple gene transcripts and that contain SNPs with ≥ 1% minor allele frequency in dbSNP dataset (v135) [28]. Probe level intensities were log2 transformed, background corrected [29] and quantile normalized [30]. Probe intensity was subtracted by the corresponding probe mean across samples. Gene-level expression intensities were summarized as mean probe intensity within each transcript cluster. In total, 16,642 autosomal transcript clusters (gene-level) were included in this study.

Statistical analysis of clinical data and gene expression variation

Clinical variables were compared between VHL WT individuals and VHLR200W homozygotes with Wilcoxon's rank sum test or Fisher's exact test. For comparison of gene expression, a linear model, gene expression level ~ genotype + error, was tested for each gene. A d-statistic [31] was calculated for the genotype effect. One hundred permutations were performed to estimate the false discovery rate (FDR) associated with the genotype effect [32]. Plasma concentrations of ferritin, EPO and VEGF were log transformed for correlation with gene expression level.

Identification of HIF-2 target genes

Public domain gene expression data for VHL−/− and HIF1A−/− renal clear cell carcinoma cell lines with and without HIF2A knocked down (4 HIF2A siRNA treated A498 cell samples verse 4 control siRNA treated A498 cell samples) [33] were compared. A similar probe signal preprocessing procedure and gene expression comparison approach described above was applied for the expression data using Affymetrix GeneChip™ Human Gene 1.0 ST Array. A total of 525 HIF-2 target genes were detected at FDR of 0.10 which had lower expressed levels in HIF2A siRNA treated A498 cells than in control siRNA treated A498 cells.

Reactome gene interaction

Genes differentially regulated in VHLR200W homozygotes were mapped to Reactome functional interaction database (2012 version) without linker genes. Gene network was constructed and clustered into sub-networks (modules). For each module, genes were ranked by the number of differential genes they interacted with within the module, and hub genes were defined as the top 20% genes.

Results

Clinical features of the study population

The clinical features of the study subjects (24 VHLR200W homozygotes and 21 VHL WT) are summarized in Table 1A. Both age and gender were matched across the two groups. As expected red blood cell count (RBC), hemoglobin concentration (HGB) and hematocrit (HCT) were increased in VHLR200W homozygotes. Nevertheless, the serum ferritin concentration was substantially reduced in 16 VHLR200W patients (P <0.001), reflecting the fact that they had been treated with phlebotomy. Two HIF-regulated biomarkers, EPO and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), were increased in VHLR200W homozygotes (P <0.001 and P = 0.039, respectively), consistent with previous reports [26].

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical variables in VHLR200W homozygotes and VHL wildtype controls. Results in median (interquartile range) were presented unless otherwise indicated. Wilcoxon's rank sum test was applied in all comparisons except gender, which used Fisher's exact test. Subjects with ferritin concentration ≥21 ug/l are presented in B, where ferritin concentration ranged from 24 to 156 μg/l in control individuals and from 23 to 131 μg/l in VHLR200W homozygotes (P=0.4).

| WT | VHLR200W | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median (IQR) | N | Median (IQR) | ||

| A. All subjects | |||||

| Age (years) | 21 | 36 (31, 54) | 24 | 35.5 (26, 52) | 0.4 |

| Female gender n (%) | 21 | 12 (57%) | 24 | 15 (63%) | 0.8 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 21 | 120 (114, 125) | 23 | 112 (105, 122) | 0.1 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 21 | 81 (76, 85) | 23 | 78 (72, 85.5) | 0.6 |

| Pulse pressure (mm Hg) | 21 | 40 (35, 43) | 23 | 39 (30, 43) | 0.2 |

| Red blood cells (1000/ul) | 21 | 4.5 (4.2, 4.9) | 24 | 6.9 (6.4, 7.8) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 21 | 125 (121, 139) | 24 | 183 (155, 191) | <0.001 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 21 | 37.4 (36.5, 41.5) | 24 | 56.2 (50.2, 58.6) | <0.001 |

| Platelet (1000/ul) | 21 | 248 (213, 301) | 23 | 220 (189, 286) | 0.3 |

| Ferritin (ug/l) | 19 | 58 (26, 76) | 24 | 14 (7, 25) | 0.001 |

| Erythropoietin (IU/l) | 19 | 7.4 (5.4, 10.5) | 23 | 48.4 (20, 75.1) | <0.001 |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor (pg/ml) | 16 | 0.2 (0.2, 0.3) | 23 | 0.2 (0.2, 5.7) | 0.039 |

| B. Subset matched for ferritin | |||||

| Age (years) | 17 | 40 (31, 56) | 8 | 48 (34, 53) | 0.9 |

| Female gender n (%) | 17 | 9 (53%) | 8 | 5 (63%) | 1 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 17 | 120 (118, 125) | 8 | 109 (104, 126) | 0.2 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 17 | 82 (78, 85) | 8 | 81 (77, 91) | 0.9 |

| Pulse pressure (mm Hg) | 17 | 40 (35, 47) | 8 | 31 (25, 40) | 0.047 |

| Red blood cells (1000/ul) | 17 | 4.5 (4.2, 5) | 8 | 6.9 (6.2, 7.8) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 17 | 128 (124, 141) | 8 | 187 (160, 191) | <0.001 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 17 | 39.5 (36.5, 42.8) | 8 | 54.5 (50.2, 58.6) | <0.001 |

| Platelet (1000/ul) | 17 | 251 (213, 301) | 8 | 248 (179, 292) | 0.5 |

| Ferritin (ug/l) | 17 | 62 (29, 78) | 8 | 46 (28, 64) | 0.4 |

| Erythropoietin (IU/l) | 17 | 7.2 (5.4, 10.1) | 8 | 50 (18.5, 79.3) | <0.001 |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor (pg/ml) | 12 | 0.2 (0.2, 0.3) | 8 | 4.6 (0.2, 14.4) | 0.025 |

PBMC transcriptional responses to constitutively activated HIF in VHLR200W homozygotes

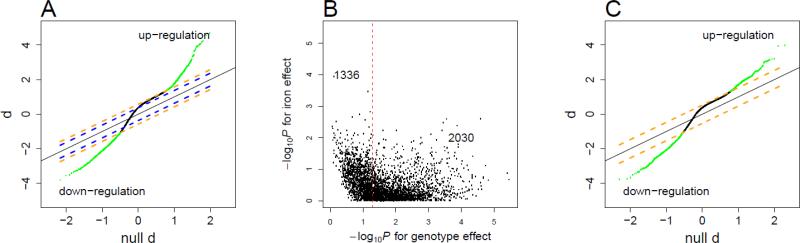

A total of 16,642 genes were analyzed for 24 VHLR200W homozygotes and 21 VHL WT individuals at normoxia. At a genome-wide false discover rate (FDR) of 0.05, almost 10,000 genes exhibited altered regulation in the VHLR200W homozygotes, predominantly a modest up-regulation (Figure 1A). As many VHLR200W homozygotes regularly undergo phlebotomy, serum ferritin concentrations were substantially lower in VHLR200W homozygotes than in WT individuals (Table 1A). Thus the detected expression difference could be attributed to genotype and/or iron variation. To assess the relative contribution of these two effects, we analyzed the expression data for the top 3366 differential genes (0.01 FDR) by a linear model including both genotype and serum ferritin concentration as explanatory variables. With ferritin variation being accounted for, genotype effect was no longer significant for 1336 genes at nominal P=0.05 (Figure 1B), suggesting that iron status, reflected as serum ferritin concentration, confounds genotype effect for a substantial proportion of genes. We thus selected for final analysis 17 control subjects and 8 VHLR200W homozygotes (Table 1B) who were iron sufficient (serum ferritin concentration ≥ 21 μg/L) and matched for age (P=0.9) and gender (P >0.9). At a genome-wide FDR of 0.05, 2932 differential genes were detected (Figure 1C), with 812 genes up regulated (Supplemental Table 1) and 2120 genes down regulated (Supplemental Table 2) in VHLR200W homozygotes. Genes differentially regulated in VHLR200W homozygotes by ≥1.5 fold are listed in Table 2. As a validation of microarray measurements, we regressed plasma VEGF concentrations on expression levels of VEGFA among 24 VHLR200W homozygotes. We found significant correlations between the two measurements (r2=0.18, P=0.04).

Figure 1.

Detection of genes differentially expressed between VHLR200W homozygotes and VHL wildtype control individuals.

A. The quantile-quantile plot for d-statistic of differential expression between 21 WT individuals and 24 VHLR200W homozygotes without controlling for serum ferritin variation. Blue lines represent d-statistic cutoffs for calling genes at FDR 0.05 and orange lines at FDR 0.01. Solid black line represents diagonal. Green points represent significant calls at FDR 0.01. The majority of genes exhibit a modest up-shift relative to the diagonal line at FDR 0.05, implying up-regulation.

B. For genes called at FDR 0.01 in A, expression level was fitted by a linear model including VHL genotype and log (ferritin) as two explanatory variables; for 1336 genes, genotype effect was no longer significant at nominal P =0.05. This indicates that ferritin variation confounded genotype effect.

C. The quantile-quantile plot for d-statistic of differential expression between 17 WT individuals and 8 VHLR200W homozygotes matched for serum ferritin concentration. Orange lines represent d-statistic cutoffs for calling genes at FDR 0.05. Green points represent significant calls at FDR 0.05.

Table 2.

Genes showing at least a 1.5-fold change in regulation in VHLR200W homozygotes.

| Direction | Affy ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Title | Fold |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| up regulation | 3142967 | CA1 | carbonic anhydrase I | 2.8 |

| 2435005 | SELENBP1 | selenium binding protein 1 | 2.3 | |

| 2571510 | IL1B | interleukin 1, beta | 2.2 | |

| 3759006 | SLC4A1 | solute carrier family 4, anion exchanger, member 1 (erythrocyte membrane protein band 3, Diego blood group) | 2.1 | |

| 3360401 | HBB | hemoglobin, beta | 2.0 | |

| 3657253 | AHSP | alpha hemoglobin stabilizing protein | 2.0 | |

| 3444252 | CSDA | cold shock domain protein A | 2.0 | |

| 2343473 | IFI44L | interferon-induced protein 44-like | 1.9 | |

| 3257204 | IFIT3 | interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 | 1.8 | |

| 3203855 | DCAF12 | DDB1 and CUL4 associated factor 12 | 1.8 | |

| 3090006 | SLC25A37 | solute carrier family 25, member 37 | 1.7 | |

| 3025500 | BPGM | 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate mutase | 1.7 | |

| 3257246 | IFIT1 | interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 | 1.7 | |

| 3360417 | HBD | hemoglobin, delta | 1.7 | |

| 2777714 | SNCA | synuclein, alpha (non A4 component of amyloid precursor) | 1.7 | |

| 3090053 | SLC25A37 | solute carrier family 25, member 37 | 1.7 | |

| 3902489 | BCL2L1 | BCL2-like 1 | 1.7 | |

| 3770345 | CD300E | CD300e molecule | 1.6 | |

| 2772566 | IGJ | immunoglobulin J polypeptide, linker protein for immunoglobulin alpha and mu polypeptides | 1.6 | |

| 3621029 | EPB42 | erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.2 | 1.6 | |

| 2353988 | FAM46C | family with sequence similarity 46, member C | 1.6 | |

| 3809621 | FECH | ferrochelatase | 1.6 | |

| 3945515 | APOBEC3A | apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3A | 1.6 | |

| 3464860 | DUSP6 | dual specificity phosphatase 6 | 1.6 | |

| 3549575 | IFI27 | interferon, alpha-inducible protein 27 | 1.6 | |

| 2731513 | EREG | epiregulin | 1.6 | |

| 2775390 | MOP-1 | MOP-1 | 1.5 | |

| 3922100 | MX1 | myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 1, interferon-inducible protein p78 (mouse) | 1.5 | |

| 2896545 | GMPR | guanosine monophosphate reductase | 1.5 | |

| 3942531 | OSBP2 | oxysterol binding protein 2 | 1.5 | |

| 2773434 | CXCL2 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2 | 1.5 | |

| down regulation | 2496536 | RPL31 | ribosomal protein L31 | 1.8 |

| 3031517 | GIMAP7 | GTPase, IMAP family member 7 | 1.8 | |

| 3617458 | GOLGA8A /8B | golgin A8 family, member A / member B | 1.7 | |

| 2781138 | LEF1 | lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 | 1.7 | |

| 2806468 | IL7R | interleukin 7 receptor | 1.6 | |

| 2821347 | ERAP2 | endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 2 | 1.6 | |

| 2665199 | SATB1 | SATB homeobox 1 | 1.5 | |

| 2809793 | GZMK | granzyme K (granzyme 3; tryptase II) | 1.5 | |

| 2515627 | ITGA6 | integrin, alpha 6 | 1.5 | |

| 2837232 | ITK | IL2-inducible T-cell kinase | 1.5 | |

| 2823880 | CAMK4 | calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV | 1.5 |

The VHLR200W mutation causes constitutive stabilization of both HIF-1 and HIF-2, which play overlapping roles in hypoxia transcription responses, each with certain target preferences [34]. Genes up-regulated in PBMCs of VHLR200W homozygotes were enriched in HIF-1 target genes that were experimentally validated in previous publications (Table S2 in [34]) by 4.8-fold (binomial test P=2×10-8), and in HIF-1 target genes revealed by expression profiling of arterial endothelial cells [8] by 2.0 fold (P=0.007). Genes induced in VHLR200W homozygotes were also enriched in HIF-2 preferred target genes in an expression profiling of human umbilical vein endothelial cells [35] by 2.5-fold (P=0.0001). We further identified 525 genes as HIF-2 targets (FDR 0.10) from the published expression dataset in which HIF2A was knocked down in VHL−/− and HIF1A−/− renal clear cell carcinoma cell lines [33]; genes induced by VHLR200W were enriched in these HIF-2 targets by 1.9-fold (P=2×10−5).

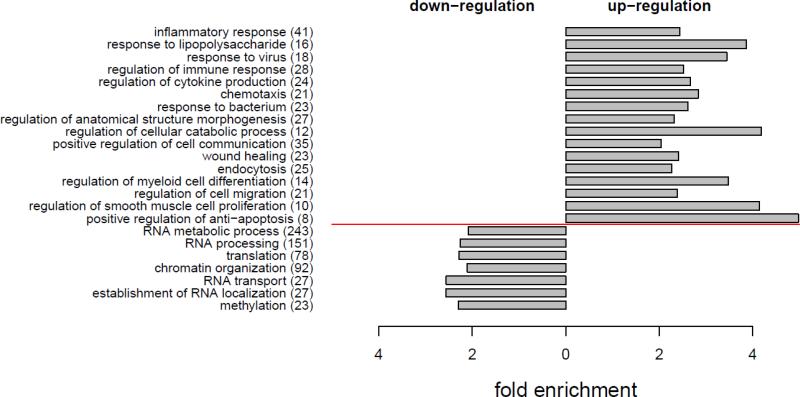

Genes up-regulated in PBMCs of VHLR200W homozygotes were enriched in Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes of inflammatory response, response to lipopolysaccharide, response to bacteria, response to virus, regulation of cytokine production, chemotaxis, regulation of anatomical structure morphogenesis, regulation of cellular catabolic process, positive regulation of cell communication, wound healing, endocytosis, regulation of myeloid cell differentiation, regulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation, and positive regulation of anti-apoptosis (Figure 2). IL6, IL1B, TNF, TLR4, HMOX1, NOD2, IL10, SLC11A1, THBS1 and EREG are involved in many of these biological processes. Genes down-regulated in VHLR200W homozygotes were enriched in GO biological processes of RNA metabolic process, RNA processing, RNA transport, translation, chromatin organization, and methylation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis for the 2932 differential genes detected between 17 VHL WT and 8 VHLR200W homozygote individuals matched for serum ferritin concentration. Genes up-regulated (812) or down-regulated (2120) in VHLR200W homozygote were analyzed for enrichment in GO. On the y-axis, GO biological processes (number of differential genes covered) were ordered by adjusted P [60] from the most to the least significance for up-regulation or down-regulation. GO with Padjusted < 0.05 and fold enrichment >2 are presented.

Gene regulation networks in VHLR200W homozygotes

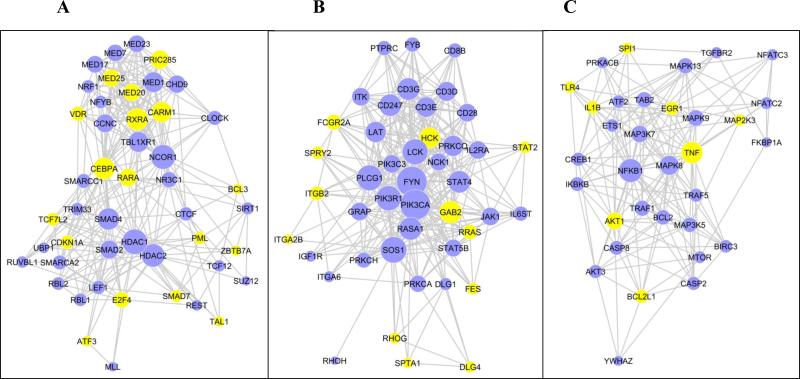

To reveal the gene regulation cascades triggered by homozygous VHLR200W mutation, we mapped the 2932 differentially expressed genes to the REACTOME functional interaction database [36] and identified three major regulatory modules (Supplemental Table 3). We ranked genes by the number of differential genes with which they interacted within the module and defined hub genes as the top 20% genes for each module. Module 1 covers 266 differential genes (Figure 3A). The up-regulated hub genes RXRA, CEBPA, RARA and PRIC285 are involved in transcriptional activation of genes involved in lipid metabolism in liver and adipose tissue [37]. The down-regulation of hub genes SMAD4 and SMAD2 and up-regulation of SMAD7 indicated a suppression of TGF-β signaling, which in turn was related to up-regulation of several cell proliferation suppressors, CDKN1A, E2F4 and PML, as well as up-regulation of TCF7L2 whose genetic variants associate with risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus [38]. Among the hub genes of this module, there was an over-representation of genes that function through epigenetic mechanisms, for instance HDAC2, HDAC1, CTCF, NCOR1 and CARM1.

Figure 3.

Three major gene regulation modules identified from the 2932 differential genes detected between 17 VHL WT and 8 VHLR200W homozygote individuals matched for serum ferritin concentration. Genes were mapped to REACTOME functional interaction database and clustered to three major regulation modules. A-C. Gene regulation modules 1-3, respectively. Only the hub genes, defined as the top 20% of genes with the most interacting genes within module, are presented. Yellow nodes denotes genes up-regulated in VHLR200W homozygotes; blue nodes denote genes down-regulated; size of nodes is proportional to the number of interactions within module.

Module 2 covers 223 differential genes (Figure 3B). T cell receptor signaling pathways were suppressed as indicated by down-regulation of genes encoding the TCR/CD3 complex subunits CD3D, CD3E, CD3G and CD247, as well as CD28 that encodes a T cell co-stimulator. These observations are consistent with our previous observations of lower peripheral blood concentrations of CD4 positive T-helper cells and lower CD4/CD8 ratio in VHLR200W homozygotes [39]. The down-regulation of PIK3CA and PIK3R1 may also associate with the suppression of T-cell proliferation. The up-regulation of FCGR2A, HCK, GAB2 and ITGB2 suggested up-regulation of phagocytosis, the up-regulation of RHOG, RRAS and FES enhanced cytoskeleton remodeling and cell-cell adhesion, and the up-regulation of STAT2 transcriptional activation of interferon-stimulated genes in this module.

Module 3 covers 187 differential genes (Figure 3C). Genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF and IL1B were up-regulated, as was TLR4, an innate immune regulator. Cell survival was up-regulated, as suggested by up-regulation of AKT1 that mediates survival signaling and BCL2L1 that inhibits cell death by regulating outer mitochondrial membrane channel opening. Consistently, Fas-mediated apoptosis was suppressed as suggested by the down-regulation of CASP8 and CASP2 and the down-regulation of MAP3K7 and MAPK8 that mediate stress-induced apoptosis. There were several additional gene modules with smaller size identified in genes differentially expressed in VHLR200W homozygotes (Supplemental Table 3). Overall these smaller modules suggested suppression of transcription, translation, DNA replication, DNA repair and mitosis in VHLR200W homozygotes.

Iron deficiency modifies the PBMC transcriptional responses to constitutively activated HIF in VHLR200W homozygotes

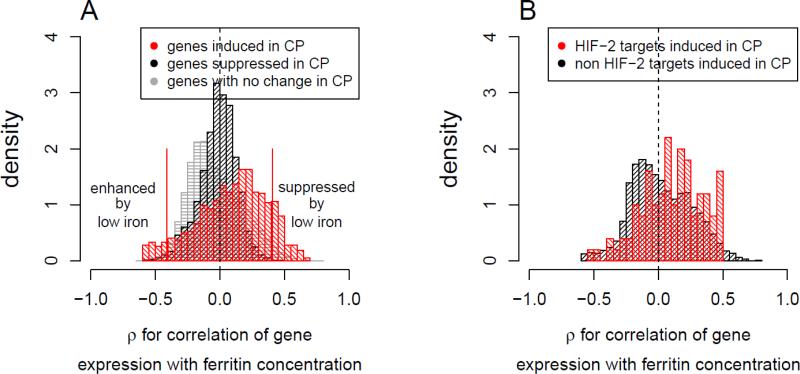

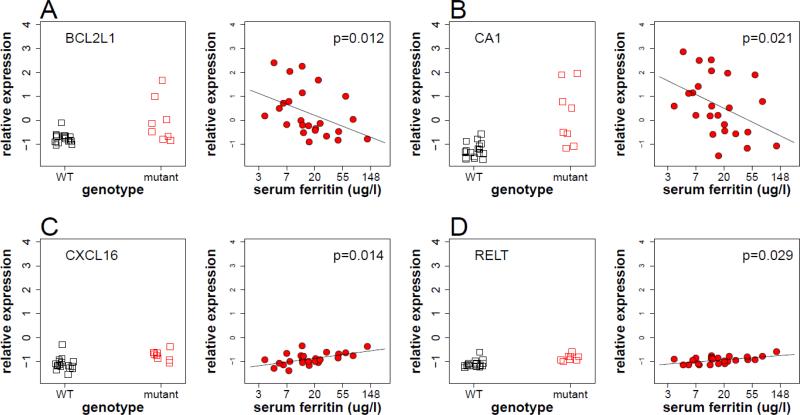

To assess the influence of iron deficiency due to phlebotomy on homozygous VHLR200W-triggered transcriptional responses, we evaluated the effect of serum ferritin concentration variation on those 2931 differential genes detected at FDR 0.05 in 24 VHLR200W homozygotes (8 iron sufficient subjects plus an additional 16 iron deficient subjects). Expression of genes up-regulated in VHLR200W homozygotes was influenced by serum ferritin concentration compared to genes down-regulated or genes with no significant difference (Figure 4A). Specifically, among the 812 up-regulated genes low serum ferritin enhanced the induction effect for 50 genes in VHLR200W homozygotes (Spearman's rank test P <0.05, Table 3). These genes included BCL2L1, BNIP3L, FKBP8 and SNCA that involved in gene module 3 for regulation of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. The low iron enhanced genes also included hemoglobin (HBB, HBD, HBM, HBQ1) and heme synthesis (FECH, SLC25A37, SLC25A39) loci, alpha hemoglobin stabilizing protein (AHSP), genes encoding erythrocyte cytoskeleton and membrane components (SPTB, ANK1, SLC4A1, EPB49, EPB42 and TMOD1), genes involved in carbon dioxide transport in erythrocytes (CA1, SLC4A1), and the hemoglobin oxygen affinity regulator, biphosphate glycerate mutase (BPGM). Previous studies had reported HBB expression in non-erythroid cells including up-regulation by hypoxia [40; 41]. In addition to an inverse correlation with serum ferritin concentration, the expression of these genes positively correlated with serum erythropoietin (EPO) concentration (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 4.

Correlation between iron status as reflected in serum ferritin concentration and expression levels of VHLR200W induced genes, across 24 VHLR200W homozygotes (8 iron sufficient plus 16 iron deficient individuals).

A. The density distribution of Spearman's ρ between expression level and serum ferritin concentration in VHLR200W homozygotes for genes induced (red) or suppressed (black) at FDR 0.05 and genes exhibiting no difference at this FDR (grey) by the VHLR200W mutation. The expression of a proportion of genes up-regulated by VHLR200W homozygosity tended to have a negative correlation with serum ferritin concentration suggesting an up regulation by iron deficiency (enhanced by low iron), while an additional proportion of genes tended to have a positive correlation with serum ferritin , suggesting a down regulation by iron deficiency (suppressed by low iron).

B. The density distribution of Spearman's ρ between gene expression level and serum ferritin concentration for genes induced in VHLR200W homozygotes that were not (black; n =2282) or that were (red, N = 100) HIF-2 targets. HIF-2 targets that were induced in VHLR200W homozygotes tended to have a positive correlation with serum ferritin concentration, suggesting down regulation by iron deficiency. HIF-2 targets were detected at 10% FDR in VHL−/− and HIF1A−/− renal clear cell carcinoma cell lines with and without HIF2A knocked down, using published microarray data [33].

Table 3.

Genes for which induction by the VHLR200W mutation was enhanced by low serum ferritin concentration (P <0.05).

| Affy ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Annotation | Spearman's ρ with ferritin concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2353988 | FAM46C | family with sequence similarity 46, member C | −0.60 |

| 3090006 | SLC25A37 | solute carrier family 25, member 37 | −0.59 |

| 3360401 | HBB | hemoglobin, beta | −0.58 |

| 3809621 | FECH | ferrochelatase | −0.58 |

| 3181240 | TMOD1 | tropomodulin 1 | −0.57 |

| 3090053 | SLC25A37 | solute carrier family 25, member 37 | −0.57 |

| 2778856 | TSPAN5 | tetraspanin 5 | −0.57 |

| 3263624 | MXI1 | MAX interactor 1 | −0.57 |

| 3621029 | EPB42 | erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.2 | −0.56 |

| 3025500 | BPGM | 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate mutase | −0.56 |

| 3203855 | DCAF12 | DDB1 and CUL4 associated factor 12 | −0.56 |

| 2777714 | SNCA | synuclein, alpha (non A4 component of amyloid precursor) | −0.54 |

| 2700828 | SIAH2 | seven in absentia homolog 2 (Drosophila) | −0.54 |

| 3759006 | SLC4A1 | solute carrier family 4, anion exchanger, member 1 (erythrocyte membrane protein band 3, Diego blood group) | −0.54 |

| 3855071 | FKBP8 | FK506 binding protein 8, 38kDa | −0.53 |

| 3759077 | SLC25A39 | solute carrier family 25, member 39 | −0.53 |

| 3286921 | MARCH8 | membrane-associated ring finger (C3HC4) 8 | −0.52 |

| 2435005 | SELENBP1 | selenium binding protein 1 | −0.52 |

| 2788003 | GYPA | glycophorin A (MNS blood group) | −0.52 |

| 3568534 | SPTB | spectrin, beta, erythrocytic | −0.51 |

| 2451463 | ADIPOR1 | adiponectin receptor 1 | −0.51 |

| 3902489 | BCL2L1 | BCL2-like 1 | −0.51 |

| 2325274 | C1orf128 | chromosome 1 open reading frame 128 | −0.51 |

| 3076178 | MKRN1 | makorin ring finger protein 1 | −0.50 |

| 3943414 | FBXO7 | F-box protein 7 | −0.50 |

| 3091000 | BNIP3L | BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19kDa interacting protein 3-like | −0.50 |

| 3638590 | MESP1 | mesoderm posterior 1 homolog (mouse) | −0.49 |

| 3676165 | HAGH | hydroxyacylglutathione hydrolase | −0.49 |

| 3434413 | RNF10 | ring finger protein 10 | −0.47 |

| 3657253 | AHSP | alpha hemoglobin stabilizing protein | −0.47 |

| 3142967 | CA1 | carbonic anhydrase I | −0.47 |

| 3550077 | GLRX5 | glutaredoxin 5 | −0.47 |

| 3781654 | RIOK3 | RIO kinase 3 (yeast) | −0.47 |

| 3642654 | HBM | hemoglobin, mu | −0.47 |

| 3089102 | EPB49 | erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.9 (dematin) | −0.46 |

| 3674886 | NPRL3 | nitrogen permease regulator-like 3 (S. cerevisiae) | −0.46 |

| 3846783 | UBXN6 | UBX domain protein 6 | −0.45 |

| 3360417 | HBD | hemoglobin, delta | −0.45 |

| 3132940 | ANK1 | ankyrin 1, erythrocytic | −0.44 |

| 3444252 | CSDA | cold shock domain protein A | −0.44 |

| 2438531 | HDGF | hepatoma-derived growth factor | −0.43 |

| 3642687 | HBQ1 | hemoglobin, theta 1 | −0.43 |

| 2896545 | GMPR | guanosine monophosphate reductase | −0.43 |

| 3217077 | HEMGN | hemogen | −0.42 |

| 3246372 | NCOA4 | nuclear receptor coactivator 4 | −0.42 |

| 2737840 | CISD2 | CDGSH iron sulfur domain 2 | −0.42 |

| 3373487 | OR5M1 | olfactory receptor, family 5, subfamily M, member 1 | −0.42 |

| 3226661 | ZER1 | zer-1 homolog (C. elegans) | −0.42 |

| 3695867 | RANBP10 | RAN binding protein 10 | −0.42 |

| 3890597 | RBM38 | RNA binding motif protein 38 | −0.41 |

Unexpectedly, low serum ferritin concentration was associated with lower expression of 107 genes up-regulated in VHLR200W homozygotes (Table 4). Compared to the strong induction effect of iron deficiency (Supplemental Figure 2), the magnitude of the suppressive effect of iron deficiency on VHLR200W up-regulated genes was generally mild (Supplemental Figure 3). Among these genes were several hub genes of the major gene regulation modules, including RARA, VDR, PML and TCF7L2 in module 1, ITGB2, RHOG and STAT2 in module 2, and AKT1 in module 3. In addition, many VHLR200W up-regulated genes that were suppressed by low iron were involved in the innate immune response and lysozyme activity (see Table 4)).

Table 4.

Genes for which induction by the VHLR200W mutation was repressed by low serum ferritin concentration (P <0.05).

| Affy ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Annotation | Spearman's ρ with ferritin concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3880767 | PYGB | phosphorylase, glycogen; brain | 0.66 |

| 3416651 | PDE1B | phosphodiesterase 1B, calmodulin-dependent | 0.66 |

| 3759849 | PLEKHM1 | pleckstrin homology domain containing, family M (with RUN domain) member 1 | 0.64 |

| 3675935 | CLCN7 | chloride channel 7 | 0.63 |

| 3381241 | ARAP1 | ArfGAP with RhoGAP domain, ankyrin repeat and PH domain 1 | 0.63 |

| 3558071 | RABGGTA | Rab geranylgeranyltransferase, alpha subunit | 0.62 |

| 3579546 | WARS | tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase | 0.61 |

| 3360006 | RHOG | ras homolog gene family, member G (rho G) | 0.61 |

| 3457614 | CS | citrate synthase | 0.61 |

| 3775038 | C17orf62 | chromosome 17 open reading frame 62 | 0.61 |

| 2489172 | MTHFD2 | methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (NADP+ dependent) 2, methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase | 0.59 |

| 3337918 | TPCN2 | two pore segment channel 2 | 0.59 |

| 3449068 | TMTC1 | transmembrane and tetratricopeptide repeat containing 1 | 0.59 |

| 3188180 | OR1N2 | olfactory receptor, family 1, subfamily N, member 2 | 0.58 |

| 3760945 | MRPL10 | mitochondrial ribosomal protein L10 | 0.57 |

| 3854954 | LRRC25 | leucine rich repeat containing 25 | 0.57 |

| 3882069 | MAPRE1 | microtubule-associated protein, RP/EB family, member 1 | 0.57 |

| 3655961 | PPP4C | protein phosphatase 4, catalytic subunit | 0.56 |

| 3581132 | AKT1 | v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 | 0.56 |

| 3009229 | POR | P450 (cytochrome) oxidoreductase | 0.55 |

| 3770345 | CD300E | CD300e molecule | 0.55 |

| 3823583 | HSH2D | hematopoietic SH2 domain containing | 0.55 |

| 3127199 | DOK2 | docking protein 2, 56kDa | 0.55 |

| 3892941 | OGFR | opioid growth factor receptor | 0.55 |

| 3544625 | FLVCR2 | feline leukemia virus subgroup C cellular receptor family, member 2 | 0.52 |

| 2398894 | RCC2 | regulator of chromosome condensation 2 | 0.52 |

| 3849044 | MYO1F | myosin IF | 0.52 |

| 3529649 | RNF31 | ring finger protein 31 | 0.51 |

| 3960930 | CBX6 | chromobox homolog 6 | 0.51 |

| 3350775 | SIDT2 | SID1 transmembrane family, member 2 | 0.51 |

| 3951768 | CECR1 | cat eye syndrome chromosome region, candidate 1 | 0.51 |

| 3695699 | ATP6V0D1 | ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal 38kDa, V0 subunit d1 | 0.51 |

| 3933399 | ZNF295 | zinc finger protein 295 | 0.51 |

| 3841574 | LILRB1 | leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor, subfamily B (with TM and ITIM domains), member 1 | 0.50 |

| 3090294 | ADAMDEC1 | ADAM-like, decysin 1 | 0.50 |

| 3354443 | SLC37A2 | solute carrier family 37 (glycerol-3-phosphate transporter), member 2 | 0.50 |

| 3911767 | CTSZ | cathepsin Z | 0.50 |

| 3389330 | CASP5 | caspase 5, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase | 0.50 |

| 3218528 | ABCA1 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 1 | 0.50 |

| 3742285 | CXCL16 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 16 | 0.49 |

| 3902682 | PLAGL2 | pleiomorphic adenoma gene-like 2 | 0.49 |

| 3577612 | SERPINA1 | serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A (alpha-1 antiproteinase, antitrypsin), member 1 | 0.49 |

| 3337390 | TCIRG1 | T-cell, immune regulator 1, ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V0 subunit A3 | 0.49 |

| 3339423 | INPPL1 | inositol polyphosphate phosphatase-like 1 | 0.49 |

| 2474977 | FOSL2 | FOS-like antigen 2 | 0.49 |

| 3833583 | SHKBP1 | SH3KBP1 binding protein 1 | 0.49 |

| 3453370 | ARF3 | ADP-ribosylation factor 3 | 0.49 |

| 3452818 | VDR | vitamin D (1,25- dihydroxyvitamin D3) receptor | 0.48 |

| 3833443 | PLD3 | phospholipase D family, member 3 | 0.48 |

| 3922037 | MX2 | myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 2 (mouse) | 0.48 |

| 3457752 | STAT2 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 2, 113kDa | 0.48 |

| 3949162 | GRAMD4 | GRAM domain containing 4 | 0.47 |

| 3553531 | TNFAIP2 | tumor necrosis factor, alpha-induced protein 2 | 0.47 |

| 2350880 | AMPD2 | adenosine monophosphate deaminase 2 | 0.47 |

| 3598165 | PLEKHO2 | pleckstrin homology domain containing, family O member 2 | 0.47 |

| 3771602 | RHBDF2 | rhomboid 5 homolog 2 (Drosophila) | 0.47 |

| 3293762 | PSAP | prosaposin | 0.47 |

| 3722338 | IFI35 | interferon-induced protein 35 | 0.47 |

| 2469213 | KLF11 | Kruppel-like factor 11 /// cystin 1 | 0.47 |

| 3529701 | IRF9 | interferon regulatory factor 9 | 0.46 |

| 3763656 | TRIM25 | tripartite motif-containing 25 | 0.46 |

| 3473727 | WSB2 | WD repeat and SOCS box-containing 2 | 0.46 |

| 3734236 | TTYH2 | tweety homolog 2 (Drosophila) | 0.46 |

| 3934729 | ITGB2 | integrin, beta 2 (complement component 3 receptor 3 and 4 subunit) | 0.46 |

| 3855856 | LPAR2 | lysophosphatidic acid receptor 2 | 0.45 |

| 3708874 | MPDU1 | mannose-P-dolichol utilization defect 1 | 0.45 |

| 2905327 | FGD2 | FYVE, RhoGEF and PH domain containing 2 | 0.45 |

| 3442941 | C3AR1 | complement component 3a receptor 1 | 0.45 |

| 3722917 | GRN | granulin | 0.45 |

| 3677516 | MEFV | Mediterranean fever | 0.45 |

| 3339880 | RELT | RELT tumor necrosis factor receptor | 0.45 |

| 3301914 | PIK3AP1 | phosphoinositide-3-kinase adaptor protein 1 | 0.45 |

| 3023246 | IRF5 | interferon regulatory factor 5 | 0.44 |

| 3386737 | C11orf75 | chromosome 11 open reading frame 75 | 0.44 |

| 3824874 | IFI30 | interferon, gamma-inducible protein 30 | 0.44 |

| 3903836 | EIF6 | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 6 | 0.44 |

| 3404549 | CLEC12B | C-type lectin domain family 12, member B | 0.44 |

| 3720921 | RARA | retinoic acid receptor, alpha | 0.44 |

| 3350830 | TAGLN | transgelin | 0.44 |

| 3738629 | SLC16A3 | solute carrier family 16, member 3 (monocarboxylic acid transporter 4) | 0.43 |

| 3316344 | CD151 | CD151 molecule (Raph blood group) | 0.43 |

| 3957938 | PISD | phosphatidylserine decarboxylase | 0.43 |

| 3866231 | STRN4 | striatin, calmodulin binding protein 4 | 0.43 |

| 3740367 | SLC43A2 | solute carrier family 43, member 2 | 0.43 |

| 3457160 | CD63 | CD63 molecule | 0.43 |

| 3824471 | GLT25D1 | glycosyltransferase 25 domain containing 1 | 0.42 |

| 3862650 | SERTAD3 | SERTA domain containing 3 | 0.42 |

| 3189580 | ZBTB43 | zinc finger and BTB domain containing 43 | 0.42 |

| 3881282 | HM13 | histocompatibility (minor) 13 | 0.42 |

| 3966000 | TYMP | thymidine phosphorylase | 0.42 |

| 3264621 | TCF7L2 | transcription factor 7-like 2 (T-cell specific, HMG-box) | 0.42 |

| 3376529 | PLA2G16 | phospholipase A2, group XVI | 0.42 |

| 3741769 | P2RX1 | purinergic receptor P2X, ligand-gated ion channel, 1 | 0.42 |

| 3660175 | NOD2 | nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2 | 0.42 |

| 3656829 | BCKDK | branched chain ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase | 0.41 |

| 3704270 | CYBA | cytochrome b-245, alpha polypeptide | 0.41 |

| 3708366 | C17orf81 | chromosome 17 open reading frame 81 | 0.41 |

| 3601387 | PML | promyelocytic leukemia | 0.41 |

| 3899173 | RRBP1 | ribosome binding protein 1 homolog 180kDa (dog) | 0.41 |

| 3372097 | ACP2 | acid phosphatase 2, lysosomal | 0.41 |

| 3432438 | OAS1 | 2',5'-oligoadenylate synthetase 1, 40/46kDa | 0.41 |

| 3774906 | SECTM1 | secreted and transmembrane 1 | 0.41 |

| 3709153 | TMEM88 | transmembrane protein 88 | 0.41 |

| 3855011 | ELL | elongation factor RNA polymerase II | 0.41 |

| 3474885 | CAMKK2 | calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 2, beta | 0.41 |

| 3861617 | HNRNPL | heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L | 0.41 |

| 3813840 | ZNF516 | zinc finger protein 516 | 0.41 |

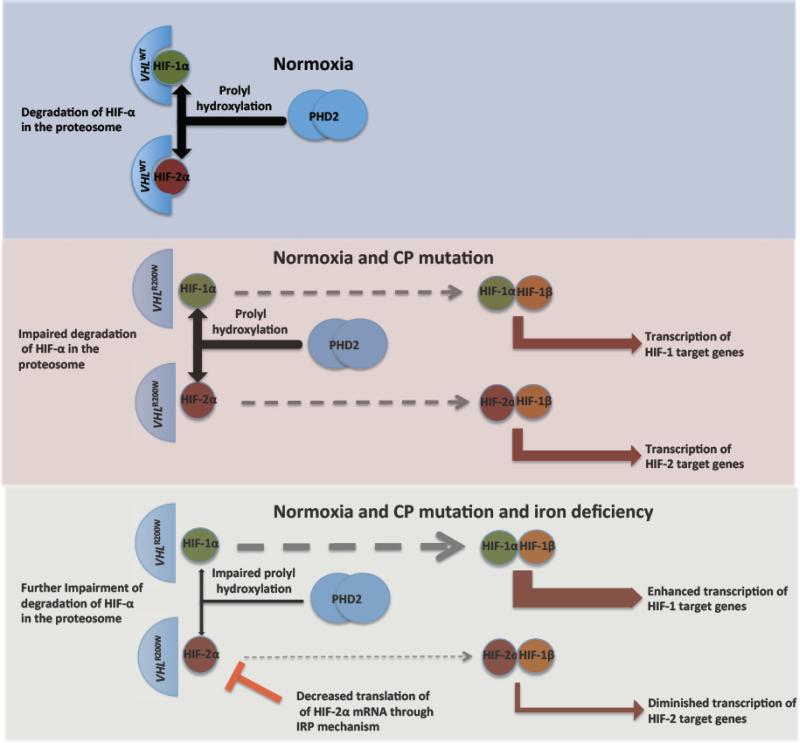

Although iron deficiency is expected to enhance HIF-1α and HIF-2α levels and related transcriptional activity by decreasing prolyl hydroxylase activity [1], it could reduce HIF-2-mediated transcription through IRP-mediated suppression of HIF-2α translation [42]. Consistent with this possible IRP-mediated decrease in HIF-2α mechanism, 100 HIF-2 target genes [33] that exhibited >1.08 fold change in VHLR200W homozygotes had significantly more positive correlations with serum ferritin concentrations than 2282 non-HIF-2 target genes with the same fold induction in VHLR200W homozygotes (one-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test P=0.0002, Figure 4B). Examples of hypoxia-induced genes that were enhanced or suppressed by iron deficiency are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Examples of homozygous VHLR200W-induced genes that were modulated by iron deficiency. Four genes, BCL2L1 (A), CA1 (B), CXCL16 (C) and RELT (D), were induced in VHLR200W homozygotes (left panels), where their expression level was correlated with serum ferritin concentration (right panels). Left panel shows 17 WT individual and 8 VHLR200W homozygotes matched for iron status; right panel shows 24 VHLR200W homozygotes. Black points denote WT individuals and red points denote VHLR200W homozygotes. P-values in right panels denote Spearman's rank test for correlation between gene expression level and log (ferritin) in VHLR200W homozygotes.

Discussion

Investigating the relationship between gene expression and environmental factors such as nutritional variables is important for understanding the selection advantages and disadvantages of genetic disorders and for developing personalized approaches to medical care [17]. Chronic hypoxia and acute hypoxia are associated with pulmonary and brain edema [3], pulmonary hypertension [4], aberrant metabolism [5; 6; 7], and increased mortality. Hypoxia has diverse effects on gene expression as investigated in cells in vitro [8], and lack of iron can further enhance pathways that are associated with hypoxia [10; 11]. To better understand the pathological processes associated with hypoxia we evaluated the expression of genes in individuals with CP, VHLR200W homozygotes with increased levels of hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs) during normoxia [19]. Furthermore, VHLR200W homozygotes often have iron deficiency due to therapeutic phlebotomies, allowing us to weigh the effect of this common nutritional and environmental variable on hypoxic gene expression. We found that the chronic hypoxic response in VHLR200W homozygotes under normoxia induced profound expression alterations in PBMCs that affect inflammation, metabolism, cell survival and cell proliferation. Furthermore, iron deficiency augments expression of HIF-1α preferred target genes whereas represses expression of potential HIF-2α preferred targets in VHLR200W homozygotes.

We recently reported that CP is characterized by lower blood glucose concentrations, likely related to decreased hepatic gluconeogenesis and increased skeletal muscle uptake and glycolysis [43]. The gene regulation module 1 revealed in this study provides further insights into the effect of VHLR200W homozygosity on metabolic pathways. Macrophages derived from peripheral blood mononuclear cells have an important role in metabolic pathways in the liver, pancreas and adipose tissue [44], and several up-regulated genes (RXRA, CEBPA, BACH1 and MAFB) are essential for macrophage-associated gene expression[45]. The up-regulation of TCF7L2 may prevent glucose intolerance by suppression of gluconeogenesis in liver [46] and stimulation of glucose up-take by peripheral organs, which is supported by decreased liver expression of Slc2a2 and G6pc but increased skeleton muscle expression of Slc2a1 in CP mice [43]. The up-regulation of RXRA, CEBPA, RARA and PRIC285 in VHLR200W homozygotes suggests a stimulation of peroxisomal beta oxidation mediated by PPARA in liver [47]. Concurrently, the up-regulation of ADIPOR1suggests increased fatty acid oxidation in adipose tissues. Generally increased lipid degradation in liver and adipose tissues may cause elevated serum glycerol and triglyceride concentrations previously observed in CP patients [43].

The lack of increased incidence of cancer in VHLR200W homozygotes is striking because they have reduced activity of the VHL tumor suppressive gene in all cells since birth, along with increased levels of HIFs and VEGF that have been implicated in oncogenesis. The Warburg effect stipulates that cancer cells are highly dependent on glycolysis rather than oxidative phosphorylation for energy production [48], and hypoxia is also associated with a shift to anaerobic glycolysis [49]. Consistently, we found down-regulation of genes involved in aerobic energy production (e.g. SDHD, NDUFA4, COX7A2, ATP5L) and up-regulation of genes involved in glycolysis (e.g. HK3, ALDOA, LDHA) in PBMCs of CP subjects. However the unexpected down-regulation of three known hypoxia-induced genes, PDK1, BNIP3 and ETS1, which in general suppress mitochondrial function and promote anaerobic glycolysis [50; 51; 52], may imply preservation of oxidative phosphorylation in CP and a potential mechanism for protection from cancer [49; 52; 53]. The up-regulation of several tumor suppressor genes (CDKN1A, E2F4, PML), as well as altered expression of markers associated with cancer outcome (SELENBP1 [54] and L DHB [55] may also help explain a cancer-protective effect of VHLR200W homozygosity. Activation of T-cells involves rapid clonal expansion, which is to a certain extent similar to cancer cells in that it depends on glycolysis for both energy and biosynthetic substrates [56]. Therefore, the suppression of T-cell activation could also be related to a metabolic profile less hospitable to oncogenesis.

The up-regulation of inflammatory and innate immune responses in gene regulation module 3 is consistent with our previous report of increased plasma concentrations of Th1 and Th2 cytokines in CP [39]. This regulation module is also likely related to macrophage activation [44], as suggested by the up-regulation of hub gene SPI1 and gene ETS2 which are key regulators of macrophage differentiation [44]. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and innate immune response genes typically derived from macrophages, for instance TNF, IL1B, IL6, IL10, TLR4 and CD14, were up-regulated in this module, as were several macrophage-associated markers MSR1, CD68 and CD163. Therefore both pro-inflammatory (M1) macrophages and anti-inflammatory (M2) macrophages appeared to be activated in CP patients.

Mechanistically, low iron suppresses PHD activity and therefore enhances both HIF-1α and HIF-2α stability. On the other hand, a down regulation of HIF-2α translation could override the activation for HIF-2α preferred target genes [24], as illustrated in Figure 6. Therefore genes enhanced by low iron were potential HIF-1 targets while genes suppressed by low iron were potential HIF-2 targets, which is supported by expression correlations with serum ferritin concentration between empirically defined HIF-2 targets and non HIF-2 targets (Figure 4B). VHLR200W-induced genes exhibited a greater tendency to be influenced by iron fluctuation compared with the suppressed genes (Figure 4A). This is consistent with the conclusion that genes down-regulated by hypoxia are typically not direct HIF target genes [57]. Notably, the VHLR200W-induced genes were biased toward a positive correlation with iron status as reflected in serum ferritin concentration, while genes called as no difference (FDR ≥ 0.05) exhibited a mild negative correlation with iron status (Figure 4A), probably because many of the latter were modestly up-regulated in CP. Overall, these observations suggest that in CP patients genes most strongly induced in PBMCs tend to be HIF-2 preferred targets.

Figure 6.

Proposed mechanism for divergent expression of HIF-target genes according to iron status. Upper panel: With non-mutated VHL and normal iron status in normoxia, the alpha subunits of HIF are degraded in the proteasome after prolyl hydroxylation through the action of PHD2. Middle panel: The homozygous VHLR200W mutation causes impaired recognition of hydroxylated alpha-subunits of HIF, leading to increased levels of the alpha subunits of HIF and increased transcription of HIF target genes under normoxia. Lower panel: The addition of iron deficiency leads to a further increase in HIF-1α through impaired function of PHD2, but a decrease in HIF-2α because of reduced translation of HIF-2α through the interaction of iron responsive protein (IRP) with an iron response element in the 5’ untranslated region of HIF-2α mRNA.

Since the suppressive effects of low iron on HIF-2 targets appeared to result from an equilibrium between PHD related HIF-2 stabilization and IRP related decrease in HIF-2 translation, such effects observed in PBMCs are likely contributed primarily by cells sensitive to iron fluctuation, in particular, monocytes that are the precursors to tissue macrophages, the major iron storage cells of the body. Notably, many of the HIF-1 targets strongly enhanced by low iron status are involved in erythrocyte function. Phlebotomy-associated iron deficiency could influence various aspects of physiology in CP. For instance, iron deficiency suppressed expression of TCF7L2 which potentially modulates the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease [58], but enhanced expression of BCL2L1, a gene inhibiting mitochondria-mediated cell death, suggesting promotion of cell survival [59]. Although optimal delineation of HIF-1 and HIF-2 gene regulation needs cell-specific expression studies, the securing of PBMCs was noninvasive, simple and practical and acceptable to the study subjects as this was virtually risk-free and there was only minimal discomfort.

In conclusion, our findings are consistent with a divergent effect of iron deficiency on expression of genes in PBMCs according to whether the gene is predominantly regulated by HIF-1 versus HIF-2 as depicted in Figure 6, but further research is needed to confirm the molecular basis of this observation. Further research to define the relative risks and benefits of therapeutic phlebotomy for polycythemia is also in order in the light of our gene expression observations. The elucidation of the genomic pathways affecting predisposition to thromboses, pulmonary hypertension, lower SBP and the interaction of augmented hypoxia sensing with iron deficiency in CP should have broad implications for understanding of the pathophysiology of many diseases and the development of targeted therapies of many human maladies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by R01 HL079912-04 (VRG) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), 2 R25-HL03679-08 (VRG) from NHLBI and the Office of Research on Minority Health, Howard University General Clinical Research Grant No. MO1-PR10284, K23HL098454 (RFM), SC1GM082325 (SN), 2G12RR003048 (SN), 8G12MD007597 (SN), and 1P30HL107253 (VRG and SN). RFM is supported by NIH R01HL111656. JTP is supported by NIH-P01CA108671 and VAH and thus his material is based upon work supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development, Clinical Sciences Research and Development including the Cooperative Studies Program, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service, and Health Services Research and Development).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Xu Zhang designed research, contributed vital analytical tools, analyzed and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript; Wei Zhang contributed vital analytical tools, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; Shwu-Fan Ma performed research, collected data, and wrote the manuscript; Galina Miasniakova designed the study and performed the research; Adelina Sergueeva designed the study and performed the research; Tatiana Ammosova performed the research and wrote the manuscript; Min Xu performed the research; Sergei Nekhai performed research and wrote the manuscript; Michael S. Wade performed the research and wrote the manuscript; Josef T. Prchal analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript; Victor R. Gordeuk designed the research, supervised data collection, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; Joe G. N. Garcia designed the research, performed and wrote the manuscript; Roberto F. Machado analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The microarray data has been submitted to Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with accession number GSE40227.

References

- 1.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell. 2012;148:399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bothwell T, Charlton RW, Cook JD, Finch CA. Iron Metabolism in Man. Blackwell Scientific Publications; Oxford: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richalet JP, Larmignat P, Poitrine E, Letournel M, Canoui-Poitrine F. Physiological risk factors for severe high-altitude illness: a prospective cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:192–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1396OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith TG, Balanos GM, Croft QP, et al. The increase in pulmonary arterial pressure caused by hypoxia depends on iron status. J Physiol. 2008;586:5999–6005. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey DM, Bartsch P, Knauth M, Baumgartner RW. Emerging concepts in acute mountain sickness and high-altitude cerebral edema: from the molecular to the morphological. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3583–94. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin DS, Ince C, Goedhart P, Levett DZ, Grocott MP. Abnormal blood flow in the sublingual microcirculation at high altitude. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:473–8. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1023-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scrase E, Laverty A, Gavlak JC, et al. The Young Everest Study: effects of hypoxia at high altitude on cardiorespiratory function and general well-being in healthy children. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:621–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.150516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manalo DJ, Rowan A, Lavoie T, et al. Transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial cell responses to hypoxia by HIF-1. Blood. 2005;105:659–69. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan G, Khan SA, Luo W, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 mediates increased expression of NADPH oxidase-2 in response to intermittent hypoxia. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:2925–33. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan DA, Sutphin PD, Denko NC, Giaccia AJ. Role of prolyl hydroxylation in oncogenically stabilized hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40112–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park SS, Bae I, Lee YJ. Flavonoids-induced accumulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha/2alpha is mediated through chelation of iron. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:1989–98. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins JF, Franck CA, Kowdley KV, Ghishan FK. Identification of differentially expressed genes in response to dietary iron deprivation in rat duodenum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G964–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00489.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fry MM, Kirk CA, Liggett JL, et al. Changes in hepatic gene expression in dogs with experimentally induced nutritional iron deficiency. Vet Clin Pathol. 2009;38:13–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165X.2008.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu CJ, Wang LY, Chodosh LA, Keith B, Simon MC. Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in hypoxic gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:9361–74. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9361-9374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karlovich C, Duchateau-Nguyen G, Johnson A, et al. A longitudinal study of gene expression in healthy individuals. BMC Med Genomics. 2009;2:33. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Rourke JA, Nelson RT, Grant D, et al. Integrating microarray analysis and the soybean genome to understand the soybeans iron deficiency response. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:376. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaput J, Rodriguez RL. Nutritional genomics: the next frontier in the postgenomic era. Physiol Genomics. 2004;16:166–77. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00107.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polyakova L. Familial erythrocytosis among inhabitants of the Chuvash ASSR. Problemi Gematologii I perelivaniya Krovi. 1974;10:30–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ang SO, Chen H, Hirota K, et al. Disruption of oxygen homeostasis underlies congenital Chuvash polycythemia. Nat Genet. 2002;32:614–21. doi: 10.1038/ng1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaelin WG, Jr., Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell. 2008;30:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minamishima YA, Kaelin WG., Jr. Reactivation of hepatic EPO synthesis in mice after PHD loss. Science. 2010;329:407. doi: 10.1126/science.1192811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hickey MM, Lam JC, Bezman NA, Rathmell WK, Simon MC. von Hippel-Lindau mutation in mice recapitulates Chuvash polycythemia via hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha signaling and splenic erythropoiesis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3879–89. doi: 10.1172/JCI32614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rankin EB, Rha J, Unger TL, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2 regulates vascular tumorigenesis in mice. Oncogene. 2008;27:5354–8. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez M, Galy B, Muckenthaler MU, Hentze MW. Iron-regulatory proteins limit hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha expression in iron deficiency. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:420–6. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bushuev VI, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, et al. Endothelin-1, vascular endothelial growth factor and systolic pulmonary artery pressure in patients with Chuvash polycythemia. Haematologica. 2006;91:744–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordeuk VR, Sergueeva AI, Miasnikova GY, et al. Congenital disorder of oxygen sensing: association of the homozygous Chuvash polycythemia VHL mutation with thrombosis and vascular abnormalities but not tumors. Blood. 2004;103:3924–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–11. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borevitz JO, Liang D, Plouffe D, et al. Large-scale identification of single-feature polymorphisms in complex genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:513–23. doi: 10.1101/gr.541303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–64. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5116–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson M. Permutation tests for univariate or multivariate analysis of variance and regression. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 2001;58:626–39. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bertout JA, Majmundar AJ, Gordan JD, et al. HIF2alpha inhibition promotes p53 pathway activity, tumor cell death, and radiation responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14391–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907357106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benita Y, Kikuchi H, Smith AD, et al. An integrative genomics approach identifies Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1)-target genes that form the core response to hypoxia. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4587–602. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagao K, Oka K. HIF-2 directly activates CD82 gene expression in endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;407:260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vastrik I, D'Eustachio P, Schmidt E, et al. Reactome: a knowledge base of biologic pathways and processes. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R39. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-3-r39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keller H, Dreyer C, Medin J, et al. Fatty acids and retinoids control lipid metabolism through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor- retinoid X receptor heterodimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2160–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grant SF, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I, et al. Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2006;38:320–3. doi: 10.1038/ng1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niu X, Miasnikova GY, Sergueeva AI, et al. Altered cytokine profiles in patients with Chuvash polycythemia. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:74–8. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu L, Zeng M, Stamler JS. Hemoglobin induction in mouse macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6643–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grek CL, Newton DA, Spyropoulos DD, Baatz JE. Hypoxia up-regulates expression of hemoglobin in alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:439–47. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0307OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zimmer M, Lamb J, Ebert BL, et al. The connectivity map links iron regulatory protein-1-mediated inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor-2a translation to the anti- inflammatory 15-deoxy-delta12,14-prostaglandin J2. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3071–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McClain DA, Abuelgasim KA, Nouraie M, et al. Decreased serum glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin levels in patients with Chuvash polycythemia: a role for HIF in glucose metabolism. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013;91:59–67. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0961-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wynn TA, Chawla A, Pollard JW. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496:445–55. doi: 10.1038/nature12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gautier EL, Shay T, Miller J, et al. Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1118–28. doi: 10.1038/ni.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vaquero AR, Ferreira NE, Omae SV, et al. Using gene-network landscape to dissect genotype effects of TCF7L2 genetic variant on diabetes and cardiovascular risk. Physiol Genomics. 2012;44:903–14. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00030.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pinaire JA, Reifel-Miller A. Therapeutic potential of retinoid x receptor modulators for the treatment of the metabolic syndrome. PPAR Res. 2007;2007:94156. doi: 10.1155/2007/94156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–14. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Semenza GL. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:12–6. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab. 2006;3:177–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Regula KM, Ens K, Kirshenbaum LA. Inducible expression of BNIP3 provokes mitochondrial defects and hypoxia-mediated cell death of ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2002;91:226–31. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000029232.42227.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verschoor ML, Wilson LA, Verschoor CP, Singh G. Ets-1 regulates energy metabolism in cancer cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hitosugi T, Fan J, Chung TW, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation of mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 is important for cancer metabolism. Mol Cell. 2011;44:864–77. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen G, Wang H, Miller CT, et al. Reduced selenium-binding protein 1 expression is associated with poor outcome in lung adenocarcinomas. J Pathol. 2004;202:321–9. doi: 10.1002/path.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zha X, Wang F, Wang Y, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase B is critical for hyperactive mTOR-mediated tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:13–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang R, Green DR. Metabolic checkpoints in activated T cells. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:907–15. doi: 10.1038/ni.2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mole DR, Blancher C, Copley RR, et al. Genome-wide association of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha and HIF-2alpha DNA binding with expression profiling of hypoxia-inducible transcripts. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16767–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901790200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grundy SM, Barlow CE, Farrell SW, Vega GL, Haskell WL. Cardiorespiratory fitness and metabolic risk. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:988–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lenihan CR, Taylor CT. The impact of hypoxia on cell death pathways. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:657–63. doi: 10.1042/BST20120345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B. 1995:289–300. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.