Abstract

Transition of Akata Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) from a malignant to nonmalignant phenotype upon loss of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is evidence for a viral contribution to tumorigenesis despite the tight restriction of EBV gene expression in BL. Examination of global cellular gene expression in Akata subclones that retained or lost EBV identified spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase (SAT1), an inducible enzyme whose catabolism of polyamines affects both apoptosis and cell growth, as one of a limited number of cellular genes downregulated upon EBV loss. Re-infection of the EBV-negative Akata clone reduced SAT1 mRNA to a level comparable with the parental EBV-positive Akata. EBV-positive Akata cells demonstrated decreased SAT1 enzyme activity concomitant with altered intracellular polyamine constituents. Reduction of SAT1 in EBV-positive BL was a transcriptional effect. Forced expression of the viral BCL2 homologue, BHRF1, in an EBV-negative Akata clone reduced SAT1 mRNA. Whereas dysregulated c-myc may enhance expression of ornithine decarboxylase elevating polyamine synthesis, EBV repression of polyamine catabolism becomes a complementary alteration favorable to BL lymphomagenesis.

Keywords: EBV, spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase, polyamines, Burkitt's lymphoma, c-myc, Akata

1. Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a prevalent gammaherpesvirus associated with a diverse array of lymphoid and epithelial cell malignancies, one being endemic Burkitt's lymphoma (BL). Common to all BL tumors is a characteristic chromosomal translocation that places c-MYC into the immunoglobulin gene locus (Dalla-Favera et al., 1982; Taub et al., 1982), with the constitutive overexpression of c-MYC being sufficient for oncogenesis. Transgenic mice carrying the c-MYC translocation develop BL-like lymphomas in the absence of EBV (Kovalchuk et al., 2000; Zhu et al., 2005). Similarly, sporadic and AIDS-associated BL are frequently EBV-negative, unlike the endemic form of disease. The virus' contribution to BL pathogenesis has been further obscured by the restricted viral gene expression program (latency I) found in EBV-positive tumors, wherein the EBV-encoded growth promoting genes are downregulated and only EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1), the non-coding EBV encoded RNAs (EBERs) and the BamHI A Rightward Transcripts (BARTs) are expressed (Rowe et al., 1987).

The possibility that EBV may act as cofactor to counter the proapoptotic effects of high c-MYC expression first became apparent from studies of a BL-derived cell line, Akata, initially positive for EBV, but after long-term culture developed subclones that had lost virus (Shimizu et al., 1994). Notably, presence of EBV was necessary to maintain the Akata malignant phenotype, as measured by growth in low serum, colony formation in soft agar, and tumor formation in SCID mice (Chodosh et al., 1998; Komano et al., 1998; Shimizu et al., 1994). EBV-negative subclones were more prone to apoptosis than the parental cells. Re-infection of EBV-negative Akata subclones restored the tumor phenotype, providing further corroboration of a complementary role for EBV in BL development (Komano et al., 1998; Ruf et al., 1999).

Attempts to define the survival advantage that EBV confers on Akata have indicated an upregulation of the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 protein and growth signals through interleukin-10 production (IL-10) (Kitagawa et al., 2000; Ruf et al., 1999). Forced expression of the EBV-encoded RNAs (EBERs), two RNA polymerase III transcripts abundantly expressed in BL, partially restored the tumor phenotype. EBV-negative Akata clones expressing EBERs formed tumors in SCID mice with enhanced IL-10 expression, albeit time to tumor development was longer than in the infected EBV-positive Akata (Komano et al., 1999; Ruf et al., 2000). EBERs have been shown to protect against some apoptotic stimuli such as interferon-α, glucocorticoid, cycloheximide, and hypoxia and may upregulate BCL-2 under some conditions (Komano et al., 1999; Nanbo et al., 2002; Ruf et al., 2000). However, EBERs were unable to restore survival under serum starvation, suggesting that other viral genes may contribute to the EBV-dependent malignant phenotype (Ruf et al., 2000).

In the study presented here we sought to further clarify cellular pathways modulated by the EBV latency I gene expression pattern that contribute to the BL tumor phenotype. We used global transcriptional profiling comparing EBV-positive Akata clones to their EBV-negative counterparts generated not after extensive passage but by treatment with hydroxyurea, an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase that forced rapid loss of EBV episomes (Chodosh et al., 1998). We identified an EBV-dependent downregulation of spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase (SAT1), a rate-limiting enzyme involved in the catabolism of polyamines (Casero and Pegg, 1993). These aliphatic cations, essential for regulation of cell growth and apoptosis, are elevated in a number of cancers including BL (Gerner and Meyskens, 2004). Such a downregulation of the catabolic pathway by EBV identifies a complementary alteration to c-MYC induction of polyamines biosynthesis, highlighting the importance of polyamine metabolism in EBV-associated BL lymphomagenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell culture and reagents

EBV-negative Akata and MutuI cell clones were generated by hydroxyurea treatment as previously described (Chodosh et al., 1998). BL2 is an EBV-negative BL cell line, and an EBV-positive counterpart was generated by infection with the B958 EBV strain. Akata EBV-positive clones (1B4, 1B6, and 4C4) and -negative counterparts (2A8, 3F2, and 2E4) including the BL2 and Mutu derived cell lines and clones were grown in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Low serum media contained 0.1% fetal bovine serum unless otherwise indicated. EBV(-) 2A8 was reinfected with recombinant Akata virus (EBVneor, gift of L. Hutt-Fletcher) (Borza and Hutt-Fletcher, 1998), and selected on G418 (MediaTech). For induction of lytic replication, 5×105 cells/ml were incubated with 10 μg/ml anti-human IgG (Cappel). Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (Moody et al., 2005). Protein lysates were prepared by lysis of equal cell numbers in 4× laemmli buffer. After transfer onto nylon membranes, membranes were hybridized with phosphorylated ERK and pan ERK antibodies (Santa Cruz) at a 1:1000 dilution. For detection of BHRF1, immunoblots were probed with a1:500 dilution of the BHRF1 antibody (Millipore, 5B11). A secondary HRP conjugated antibody was used for detection by standard methods.

2.2. Microarray expression profiling

Logarithmically growing EBV(-) 2A8 and EBV(+) 1B6 cell clones were seeded at 2.5×105 cells/ml and grown overnight in complete media. Since the EBV-induced tumor phenotype is observed in low serum (Chodosh et al., 1998; Komano et al., 1998; Shimizu et al., 1994), cells were exposed to 1% serum for 4 h. RNA was harvested using STAT-60 (Teltest) as per manufacturer's protocol and integrity was monitored on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Double-stranded cDNA was synthesized from 10 μg total RNA using a Superscript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) in combination with a T7-(dT)24 primer. Biotinylated cRNA was transcribed in vitro using the BioArray High Yield RNA Transcript Labeling Kit (ENZO Biochem), purified using the GeneChip Sample Cleanup Module (Affymetrix), and fragmented by incubation in fragmentation buffer (200 mM Tris-acetate, pH 8.1, 500 mM potassium acetate, 150 mM magnesium acetate) at 94°C for 35 min. Fifteen micrograms of fragmented biotin-labeled cRNA was hybridized to the Human Genome U95Av2 Array (Affymetrix), interrogating a total of 12,625 human genes. Arrays were incubated, washed, and stained with 10 μg/ml streptavidin-R phycoerythrin (Vector Laboratories) followed by 3 μg/ml biotinylated goat anti-streptavidin antibody (Vector Laboratories) as per manufacturer's protocol, then read with a GeneChip Scanner 3000. Expression signals were analyzed using Microarray Analysis Suite 5 (Affymetrix). Arrays were globally scaled to a target intensity value of 2500 in order to compare individual experiments. The absolute call, direction of change, and fold change of gene expressions between samples were calculated with Data Mining Tool 3.0 (Affymetrix). Significant genes were identified by filtering data using Spotfire software according to these criteria: 1) signal values had to be statistically significant (p<0.05) as calculated by Spotfire's T-test/Anova algorithm; 2) detection calls had to be present in at least 1 out of 6 samples; 3) the average signal log ratio of the 3 experiments was set at an absolute value ≥ 0.9. Microarray data has been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (Accession#GSE19761).

2.3. Reverse-transcription PCR

RNA was harvested using STAT-60. DNase-treated RNA was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis (Wagner et al., 2004). For real-time quantitative (RQ) RT-PCR of SAT1 message, primers and TaqMan probe were designed using PrimerExpress and amplification was measured by the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). One hundred nanograms of cDNA were amplified in TaqMan Universal PCR Master mix (Applied Biosystems) with 300 nM of primers and 200 nM of probe. Negative controls included RT-negative and template-negative samples. Serially diluted cDNA was used to validate the RQ-PCR assay relative to endogenous human GAPDH (Applied Biosystems p/n 4310884E). GAPDH served as a normalization control and the ΔΔCT method was used for quantitation (User Bulletin #2, Applied Biosystems). Standard cycling conditions were used setting 60°C as the annealing temperature for SAT1 and GAPDH. Statistical analysis was performed using single factor Anova analysis. RT-PCR detection of SAT1 spliced variant and EBV BHRF1 and BZLF1 was performed using primers as described in Table 1. One hundred nanograms of cDNA was amplified using 500 nM of primers using 1 unit of Go Taq polymerase (Promega). Thermocyling condition following a 94°C 5minute denaturation consisted of 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, annealing temperature in Table 1 for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec and ending with 7 minute extension time. PCR products were visualized after agarose gel electrophoresis by ethidium bromide staining, or by hybridization with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides probes (Table 1) following Southern blotting onto nylon membranes (Southern, 1975).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers and probes used in this study.

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′) | Genomic position/ Accession# | Tm (°C) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RQ-SSAT-F (exon 3) | GGT TGC AGA AGT GCC GAA A | 330-348 / NM_002970 | 60 | |

| RQ-SSAT-R (exon 4) | CCA ATC CAC GGG TCA TAG GT | 422-403 / NM_002970 | 60 | |

| TaqMan SSAT probe (exon 3/4) | FAM-CAC TGG ACT CCG GAA GGA CAC AGC A-TAMRA | 352-376 / NM_002970 | --- | |

| RQ-SSATUN-F (exon 2) | TGG CTA AAT ATG AAT ACA TGG AAG AAC A | 1587-1614 / HSSSPN1AG | 60 | |

| RQ-SSATUN-R (intron 2) | AGG CAC CGA ACG CTT GTC | 1677-1660 / HSSSPN1AG | 60 | |

| RQ-SSATUN-Probe | FAM-AAA AAG GTA ATT CAA CAG TGG CGG GAC G-TAMRA | 1629-1656 / HSSSPN1AG | --- | |

| P1 (SSAT exon 1) | AGC CAC TGC CTC TGA CTG | 7-25 / NM_002970 | 50 | |

| P4 (SSAT exon X) | GAG ACT GTA ACC TTC CGG AG | 214-195 / AY841998 | 50 | |

| P6 (SSAT exon 6) | CTC TTC ACT GGA CAG ATC AG | 621-601 / NM_002970 | 50 | |

| GAPDH-F | GAA GGT GAA GGT CGG AGT | 108-125 / NM_002046 | 50 | |

| GAPDH-R | GAA GAT GGT GAT GGG ATT TC | 333-314 / NM_002046 | 50 | |

| BHRF1-C (CDS) | GTG CAT GGA AAT GGT A | 42142 – 42157/ AJ507799 | 50 | (a) |

| BHRF1- D (CDS) | AAG GCT TGG GTC TCC | 42381 – 42367/ AJ407799 | 50 | (a) |

| BHRF1 W2 | TGG TAA GCG GTT CAC CTT CAG | 33242- 33262/ AJ507799 | 50 | (b) |

| BHRF1 Y2 (Cp / Wp initiated) | TAC GCA TTA GAG ACC ACT TTG AGC C | 35609- 35633/ AJ507799 | 50 | (b) |

| BHRF1 probe | TGC ATC CTG TGT TGG AGC TAG CAG CA | 42161-42186/ AJ507799 | --- | |

| BHRF1 H2 (Hp initiated) | GTC AAG GTT TCG TCT GTG TG | 41542 -41561/ AJ507799 | 50 | (c) |

| BZLF1-F | CTTGGCCCGGCATTTTCT | 90168-90185/ AJ50799 | 60 | |

| BZLF1-R | ACGACGCACACGGAAACC | 90400-90383/ AJ507799 |

2.4. Spermidine acetylation assay

Cells seeded at 2×105 per ml were grown for 24 hrs followed by treatment for 24 hrs with 10 μM N1, N11-di(ethyl)norspermine (DENSPM; Tocris Cookson Inc.). DENSPM-treated cells were resuspended at 2×107 per ml in 5 mM HEPES pH 7.2 containing 1 mM DTT, and sonicated for 5 min at 20% power (W-380 sonicator, Heat Systems Ultrasonic, Inc.). Protein extracts were cleared by high speed microfuge centrifugation at 4°C. SAT1 activity in each cell clone was measured by acetylation of spermidine as previously described (Matsui and Pegg, 1981). Briefly, in a 100 μl reaction, 70 μl of protein extract was incubated with 3 mM spermidine (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 mM Tris-HCL (pH 7.8), and 10 μl [1-14C] acetyl-CoA (4 μCi/ml, MP Biochemicals) for 10 min at 37°C. Reactions were stopped by addition of 1M NH2OH-HCL, and boiled for 3 min. Insoluble proteins were removed by high speed centrifugation. Fifty microliters of reaction mix were spotted onto cellulose phosphate paper disks (Whatmann P81), washed×5 with distilled water, followed by 3 washes with absolute ethanol. Disks were air-dried and scintillation counted. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t-Test.

2.5. Analysis of intracellular polyamine pools

EBV-positive and –negative cell clones were seeded at 2×105 cells/ml in 10% or 0.1% serum growth media and harvested at 72 or 24 hrs, respectively. Intracellular polyamines using a modified dansylation detection method (Kabra et al., 1986). One hundred microliters of 0.2 M perchloric acid containing 125 μM of 1,6 diaminohexamine was added to every 1×106 cells as an internal standard. Cells were sonicated on ice for 2 hrs in a Bransonic 1210 ultrasonic cleaner, and insoluble material was cleared by centrifugation. To each 100 μl of cell extract (1×106 cell equivalents), 350 μl of 5 mg/ml dansyl chloride and 50 μl of 1.8 mg/ml sodium carbonate were added and incubated at 55°C for 2 hrs. Twenty microliters of 100 mg/ml proline was added and vortexed until clear. Dansylated polyamines were extracted with 1 ml tolulene, dried under nitrogen, and reconstituted with 30 μl of acetonitrile. Separation of the dansylated polyamines was performed by reverse-phase HPLC with fluorescence detector (Agilent Technologies) using a C18 column (Agilent hypersil ODS). Columns were eluted with the following 4 stepped linear gradients: 1) 6 min in 20% acetylnitrile with 80% of 1% acetic acid/0.03% triethylamine (HAcTEA), 2) 35 min with 62% acetylnitrile and 38% HAcTEA, 3) 40 min with 65% acetylnitrile and 35% HAcTEA, 4) 45 min with 95% acetylnitrile and 5% HAcTEA. Fluorescent signal emission was detected at 525 nm (excitation at 340 nm). Chromatogram peaks were quantified with Chemstation for liquid chromatography version 9 (Agilent Technologies). For each run, standard curves for putrescine, spermidine, spermine and their acetylated counterparts were performed. Sample values were normalized to the internal standard and reported as pmol per 106 cells. Six independent experiments were performed and statistical analysis was performed using single factor Anova.

2.6. Transfections

A BHRF1 expression construct was created by amplifying the BHRF1 open reading frame from EBV-strain B958 using the Expand Long Template PCR system (Boehringer Mannheim) (forward primer, CGCCGAATTCATCTTGTAGAGCAAGATGGC and reverse primer, GCGCCTCGAGCAATGACCCTGATTCATATA). The PCR product was cloned into the EcoRI and XhoI multiple cloning site of the pLXSN vector and verified by sequencing. The EBV(-)clone 2A8 was transfected using the Amaxa Nucleoporation system (program N-16). Briefly, cells were seeded at 2×105 cells/ml 2 days prior transfection. 1×106 logarithmically growing cells were resuspended in Amaxa V solution and transfected with 2 μg of endotoxin free plasmid DNA. Stably transfected cells were selected with 350 μg/ml G418.

3. Results

3.1. Transcriptional profiling to identify altered cellular gene expression in the Akata EBV-dependent tumor phenotype

Using Affymetrix U95A GeneChips, we examined variations in global gene expression between the EBV-positive (1B6) and EBV-negative (2A8) Akata clones derived from hydroxyurea treatment. Because growth under conditions of serum starvation provides one measure of the Akata tumor phenotype (Chodosh et al., 1998; Ruf et al., 1999; Shimizu et al., 1994), cell clones were serum starved for 4 hours prior to RNA harvest. The short incubation time was intended to minimize cell death and other potential downstream effects of low serum treatment, while at the same time initiating expression changes contributing to the tumorigenic phenotype. Twenty-three genes showed statistically significant (p<0.05) differences of 1.9-fold or greater in the EBV-positive Akata clone compared to its EBV-negative counterpart in three independent experiments (Table 2). The genes were equally split between the upregulated (11 genes) and downregulated (12 genes) groups. The small number of gene expression changes (approximately 0.2% of the some 12,000 queried) attests to both the relatedness of clones rapidly “cured” of EBV by hydroxyurea (Chodosh et al., 1998) to their EBV-positive counterparts. Two independent probesets identified DNA damage-inducible transcript 3 (DDIT3) and spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase (SAT1) being differentially expressed in EBV-positive and –negative Akata BL. We focused our attention on SAT1, as a second alteration in polyamine metabolism dependent on EBV in BL: the first being the c-myc translocation characteristic of BL.

Table 2.

Global transcription profiling of EBV-positive and –negative Akata BL clones.

| ProbeSet ID | Gene Symbol | Description | Fold Δ * | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downregulated | ||||

| 808_at | RAB27B | RAB27B, member RAS oncogene family | -14.6 | 0.0054 |

| 36261_at | SYT17 | synaptotagmin XVII | -4.2 | 0.0003 |

| 41027_at | FOXC1 | forkhead box C1 | -3.2 | 0.0098 |

| 39298_at | ST3GAL6 | ST3 beta-galactoside alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase 6 | -2.3 | 0.0003 |

| 34107_at | PFKFB2 | 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase | -2.7 | 0.0147 |

| 756_at | ITPR2 | inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor, type 2 | -2.7 | 0.0224 |

| 35459_at | RGS13 | regulator of G-protein signaling 13 | -2.5 | 0.0036 |

| 1173_g_at | SAT1 | spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 1 | -2.4 | 0.0002 |

| 38228_g_at | MITF | microphthalmia-associated transcription factor | -2.3 | 0.0089 |

| 34304_s_at | SAT1 | spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 1 | -2.3 | 0.0178 |

| 32916_at | PTPRE | protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, E | -2.1 | 0.0417 |

| 34342_s_at | SPP1 | secreted phosphoprotein 1 | -2.0 | 0.0159 |

| 40024_at | STAC | SH3 and cysteine rich domain | -1.9 | 0.0033 |

| Upregulated | ||||

| 39420_at | DDIT3 | DNA-damage inducible transcript 3 | 1.9 | 0.0273 |

| 39827_at | DDIT4 | DNA-damage-inducible transcript 4 | 2.0 | 0.0048 |

| 35842_at | IL6ST | interleukin 6 signal transducer (gp130, oncostatin M receptor) | 2.0 | 0.0409 |

| 35799_at | DNAJB9 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily B, member 9 | 2.0 | 0.0077 |

| 34777_at | ADM | adrenomedullin | 2.1 | 0.0232 |

| 37044_at | PDIA5 | protein disulfide isomerase family A, member 5 | 2.2 | 0.0195 |

| 442_at | HSP90B1 | heat shock protein 90kDa beta (Grp94), member 1 | 2.4 | 0.0006 |

| 41371_at | GTF2H4 | general transcription factor IIH, polypeptide 4, 52kDa | 2.6 | 0.0461 |

| 39037_at | AFF1 | AF4/FMR2 family, member | 2.6 | 0.0332 |

| 40143_at | FAM53B | family with sequence similarity 53, member B | 2.8 | 0.0072 |

| 40201_at | DDC | dopa decarboxylase | 3.3 | 0.0192 |

| 1842_at | DDIT3 | DNA-damage-inducible transcript 3 | 4.4 | 0.0098 |

Fold Difference was calculated as 2signal log ratio, where the signal log ratio is the intensity value from the EBV-positive Akata clone (1B6) compared to the EBV-negative Akata clone (2A8).

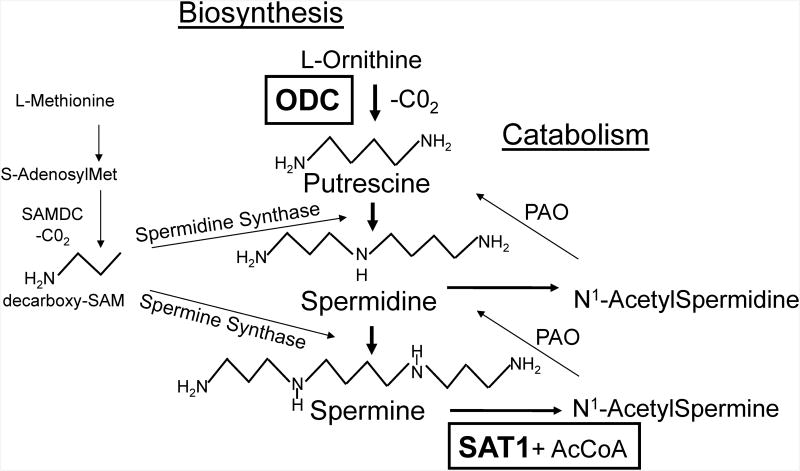

C-myc and its family members are transcription factors that promote cell growth and transformation by regulating the transcription of target genes required for proliferation (Baudino and Cleveland, 2001). Among the c-myc target genes for c-myc is ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), a key regulatory enzyme driving polyamine biosynthesis (Bello-Fernandez et al., 1993) (Fig.1). Elevated ODC activity with resultant higher polyamine levels are detected in rapidly proliferating cells and in various tumors including BL (Bello-Fernandez et al., 1993), implicating the synthetic pathway in tumorigenesis. Polyamines are aliphatic cations (putrescine, spermidine, and spermine) involved in multiple functions that support cell survival and growth. Irreversible inhibitors of ODC, such as difluoromethylornithine (DFMO), act as cytostatic agents that arrest the cell cycle and cell growth (Meyskens and Gerner, 1999). On the other hand, SAT1 is a rate-limiting enzyme that catalyzes the acetylation of spermidine and spermine and with polyamine oxidase (PAO) results in polyamine degradation. Thus, we investigated how EBV manipulated SAT1 expression in the Akata BL cell line.

Figure 1.

Schematic of polyamine synthetic and catabolic pathways. Polyamines are synthesized by the decarboxylation of two amino acids (L-ornithine and L-methionine). Decarboxylation of L-ornithine is catalyzed by ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) to produce the diamine, putrescine. The second aspect of biosynthesis begins with the decarboxylation of L-methionine catalyzed by S-adenosylmethione decarboxylase resulting in aminopropyl groups that are attached to putrescine or spermidine by spermidine synthase and spermine synthase, respectively, to form the longer chained polyamines, spermidine and spermine. Catabolism of polyamines is regulated by SAT1, which can acetylate both spermidine and spermine. The acetylated polyamines are in turn cleaved by polyamine oxidase to generate the shorter chained polyamines. In addition, acetylated polyamines are rapidly removed from the cell to aid in the depletion of polyamines. Thus, the combined action of biosynthesis and catabolism determine the polyamine levels within a cell (adapted from (Gerner and Meyskens, 2004)).

3.2 EBV-dependent repression of SAT1 expression

To define the conditions required for downregulation of SAT1 mRNA in the EBV-positive clone 1B6, real-time quantitative RT-PCR (RQ-RT-PCR) was used to measure the levels of SAT1 mRNA in three EBV-positive and EBV-negative Akata clones under growth conditions of low (0.1%) or normal (10%) serum (Fig. 2A). Using the ΔΔCT method, the relative amount of SAT1 transcripts was normalized to GAPDH and compared to the EBV-positive Akata 1B4 clone (10% serum) as the calibrator. After 48 hours of serum starvation, three EBV-positive Akata clones showed a comparable decrease in SAT1 mRNA relative to EBV-negative counterparts (average of 4.2 ± 0.3 SAT1 transcripts/100ng RNA versus 8.0 ± 1.1 SAT1 transcripts/100ng RNA, respectively; p<0.05) as was shown by microarray. In 10% serum, a reduction in SAT1 mRNA levels was still apparent in EBV-positive clones showing a two-fold reduction in SAT1 mRNA relative to EBV-negative clones (average of 1.2 ± 0.2 SAT1 transcripts/100ng RNA versus 2.8 ± 0.2 SAT1 transcripts/100ng RNA, respectively; p<0.01) (Fig.2A).

Figure 2.

EBV-dependent repression of SAT1 mRNA levels. A) SAT1 mRNA levels in EBV-positive BL clones compared to BL clones “cured” of virus under 0.1% serum starvation (striped bars) and 10% serum (solid bars). The mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) from five independent experiments is shown. Values are reported relative to the EBV-positive 1B4 clone grown in 10% serum. B) SAT1 repression upon re-infection of EBV-negative Akata BL clone. SAT1 mRNA levels in the EBV-negative Akata clone (2A8) infected with a recombinant EBV-Akata strain (BDLF3-, striped bar) was compared to the uninfected EBV-negative 2A8 clone (grey bar) and the EBV-positive 1B6 clone (black bar). The mean and SEM from two independent experiments is shown relative to the re-infected clone. C) Comparison of SAT1 mRNA levels in paired EBV-positive and –negative BL cell lines derived from Akata, MutuI, and BL2. The mean and SEM from 2 independent experiments is shown. Grey boxes denote the EBV-negative BL cell line while black shaded bars denote the EBV-positive BL cell lines.

To determine if the downregulation of SAT1 mRNA observed was dependent on EBV, we quantified SAT1 mRNA in the EBV-negative Akata cell clone 2A8 re-infected with a recombinant Akata EBV strain (EBVneor). Re-infection of EBV-negative Akata cells has previously been shown to restore the tumor phenotype (Komano et al., 1998; Ruf et al., 1999). Indeed, the reinfected 2A8 clone reduced SAT1 mRNA levels by 2.5-fold, comparable to that found in the parental EBV-positive Akata BL cell clones (Fig. 2B). To expand our observations of EBV repressioShn of SAT1 to other EBV-positive and –negative BL cell lines, we quantified SAT1 mRNA levels in paired EBV-negative and-positive BL cell lines (MutuI and BL2). The MutuI EBV-negative clone was cured of EBV episomes by hydroxyurea similar to the EBV-negative Akata clones used in this study. The EBV-negative MutuI clone and BL2 cell lines displayed already reduced SAT1 mRNA levels that were similar or below that measured for the EBV-positive Akata clones. In Mutu and BL2 cells, EBV did not further repress SAT1 mRNA levels (Fig. 2C). One difference between these BL cell lines is that, in contrast to the Akata-derived EBV-negative BL clones, the Mutu-derived EBV-negative clone and the BL2 cell line retain their malignant phenotype despite loss of the viral episome (Chodosh et al., 1998). These results suggest that repression of SAT1 occurs in the BL malignant phenotype.

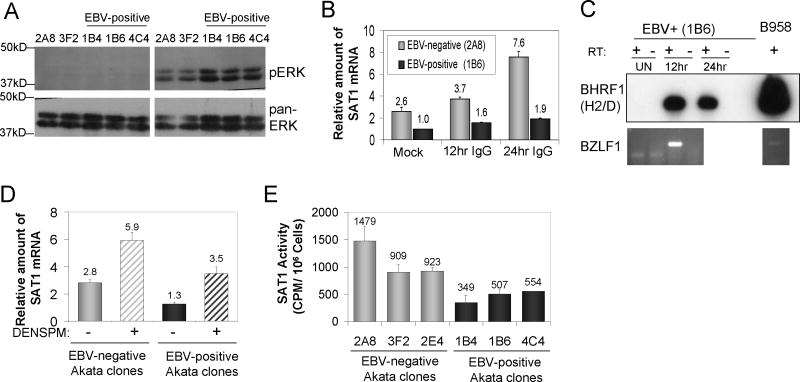

3.3. EBV maintains reduced SAT1 mRNA levels in conditions known to induce SAT1 expression

To determine if experimental activation of SAT1 is capable of overcoming its repression in EBV-positive cells relative to their EBV-negative counterparts, we first examined the effect of B-cell receptor (BCR) crosslinking known to induce SAT1 expression in B cells (Nitta et al., 2001). To ensure that EBV-positive and –negative clones were capable of being similarly activated by IgG crosslinking, phosphorylation of ERK was measured after 30 minutes of stimulation as the downstream readout of BCR activation. As shown in Fig 3A, treatment with IgG resulted in upregulation of phosphorylated ERK 1 and 2 in both the EBV-positive and – negative Akata BL clones. Densitometric analysis of phospho-ERK to pan ERK showed a slightly increased activation in the EBV-positive Akata BL of ∼1.8 fold compared to the EBV-negative Akata clones.

Figure 3.

Maintenance of EBV-dependent repression of SAT1 levels with inducers of SAT1 expression. A) ERK activation following BCR crosslinking. Western blot analysis was performed to detect phosphorlated ERK (pERK) and pan-ERK after 30 minutes of BCR crosslinking. B) Effect of BCR crosslinking on SAT1 mRNA levels. RNA was harvested from cells treated with 10ug/ml anti-human IgG at 12 and 24 hours. Mock samples were harvested at 24 hours. Values are reported relative to the mock-treated, EBV-positive 1B6 clone. The mean and SEM from two independent experiments is shown. C) Top panel: BHRF1 expression after 12 and 24 hours following BCR crosslinking. Shown is a Southern hybridization to RT-PCR amplicons using primers H2/D specific for the lytic form of BHRF1. Bottom panel: BZLF1 expression at 12 hours following BCR crosslinking. Shown is an image from an ethidium bromide stained agarose gel of RT-PCR amplicons using BZLF1 specific primers. D) Effect of polyamine analog treatment on SAT1 mRNA levels in EBV-positive and -negative BL clones. Cells were treated for 24 hours with 10uM diethylnorspermidine (DENSPM) or mock-treated with vehicle control. The average and SEM from four independent experiments is shown relative to the value from the 1B4 clone. E) Comparison of SAT1 activity in DENSPM-treated, EBV-positive and negative BL clones. SAT1 activity was measured using an in vitro spermidine acetylation enzyme assay. Shown is the mean and SEM from 5 independent experiments.

Using the EBV-negative (2A8) and EBV-positive (1B6) clones, SAT1 mRNA levels were measured after treatment with anti-human IgG for 12 and 24 hours. BCR crosslinking produced a time-dependent increase in SAT1 mRNA in the EBV-negative clone 2A8 whereas levels remained largely repressed in the EBV-positive clone (1B6) (Fig. 3B). The initial 2.5 fold difference in mock treated samples increased to a 4-fold difference by 24 hours (Fig. 3B). The two treatments shown to induce SAT1 expression, BCR crosslinking (Fig. 3B) and serum starvation (Fig. 2A), are commonly used to activate EBV lytic replication (Takada et al., 1991). Indeed, expression of lytic BHRF1 was observed in the EBV-positive clone (1B6) at 12 and 24 hours post-IgG stimulation (Fig 3C). Expression of the immediate early gene, BZLF1, mRNA confirmed activation of lytic replication at 12 hours following IgG stimulation. Thus, EBV-dependent repression of SAT1 under both treatment conditions potentially is maintained not only during the restrictive type I latency characteristic of BL cells but during the lytic phase of the EBV life cycle as well.

To more directly manipulate polyamine metabolism in paired Akata cell clones, we used N1, N11 diethylnorspermine (DENSPM), a synthetic polyamine analog that downregulates polyamine biosynthesis and potently induces SAT1 mRNA and activity (Bernacki et al., 1992; Fogel-Petrovic et al., 1993; Fogel-Petrovic et al., 1996). DENSPM induction of SAT1 activity involves increased SAT1 mRNA stability, translation efficiency, and protein stability (Fogel-Petrovic et al., 1993; Fogel-Petrovic et al., 1996; Libby et al., 1989; Parry et al., 1995; Xiao and Casero, 1996). Treatment with DENSPM mimics high polyamine concentrations, activating feedback loops that turn off the biosynthetic pathways and turn on the catabolic pathway regulated by SAT1. The DENSPM polyamine analog does not substitute for the growth stimulating effects of polyamines; instead, DENSPM results in depletion of polyamine pools, growth inhibition, and in some cases apoptosis. Three EBV-positive and EBV-negative Akata BL clones were treated with DENSPM, and the amount of SAT1 mRNA was quantified by RQ-RT-PCR. DENSPM treatment increased SAT1 mRNA levels in all clones regardless of EBV status, but the approximately 2 fold reduction in SAT1 found in untreated EBV-positive clones was maintained (Fig. 3D).

3.4 SAT1 mRNA levels reflect enzymatic catabolic activity

To address whether mRNA levels reflected the biological activity of SAT1, we took advantage of DENSPM's ability to increase SAT1 enzyme activity several orders of magnitude above the mRNA increase (Fogel-Petrovic et al., 1996). Basal SAT1 activity is typically below the limit of detection in acetylation assays, and this proved to be the case with our Akata BL cell clones. Extracts from DENSPM-treated cells were incubated with spermidine and 14C radiolabeled acetylCoA and the amount of 14C labeled spermidine was quantified by scintillation counting as a measure of SAT1 activity (Fig. 3E) (Matsui and Pegg, 1981). Decreased spermidine acetylation was detected in the three EBV-positive as compared to EBV-negative Akata cell clones (mean of 470±62 CPM/106 cells versus 1103±188 CPM/106 cells, respectively; p<0.05). Decreased SAT1 activity in the EBV-positive Akata clones (2.3 fold) correlated with the fold reduction in mRNA level (Fig. 3D) suggesting that EBV regulation of SAT1 primarily occurs at the RNA level.

3.5. EBV reduction of SAT1 affects polyamine levels in Akata BL

Having established a correlation between reduction in SAT1 mRNA and SAT1 enzymatic activity, we next examined the impact on intracellular polyamine levels. SAT1 regulates levels of the long chained polyamines, spermidine and spermine, through acetylation of these substrates, which are either cleaved by polyamine oxidase to generate smaller chained polyamines or excreted from the cell, resulting in polyamine depletion (Fig. 1). To determine if reduced SAT1 mRNA and enzyme activity in the EBV-positive Akata cells resulted in altered intracellular polyamine levels, we performed reverse phase HPLC analysis using extracts from EBV-positive and -negative Akata clones.

In 10% serum, the EBV-positive Akata clones had a 1.8-fold decrease (p<0.05) in acetylspermidine as compared to the EBV-negative clones (Table 3). Because acetylspermidine is a direct acetylation product of SAT1, decreased acetylspermidine levels demonstrated a functionally relevant change consequent to reduced catabolism of polyamines in EBV-positive clones. There were no signification differences in the levels of intracellular putrescine, spermidine and spermine, possibly reflecting the comparable growth of both sets of clones under serum-rich conditions and/or compensatory mechanisms that modulate polyamine levels. Lack of alterations in polyamine pools have been previously reported even when basal SAT1 was reduced by 80% using siRNA in human melanoma cells, reflecting coordinate regulation of the biosynthetic/catabolic and import/export pathways that maintain polyamine homeostasis (Chen et al., 2003).

Table 3.

Intracellular polyamine pools in EBV-negative and –positive BL clones.

| Sample | Putrescine pmol/106 cells | Acetyl spermidine pmol/106 cells | Spermidine pmol/106 cells | Acetyl spermine pmol/106 cells | Spermine pmol/106 cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBV-negative BL clones (10% FBS) | 2.14±0.25 | 3.98±0.70 | 170.70±7.59 | nd. | 0.50±0.06 |

| EBV-positive BL clones (10% FBS) | 1.70±0.15 | 2.16±0.27* | 175.39±7.41 | nd. | 0.58±0.06 |

| EBV-negative BL clones (0.1% FBS) | 0.65±0.10 | 1.49±0.47 | 177.45±16.82 | nd | 0.47±0.05 |

| EBV-positive BL clones (0.1% FBS) | 0.79±0.14 | 1.09±0.28 | 212.17±17.33 | nd | 0.88±0.15** |

Polyamine amounts are reported as the mean of four clones ± standard error of the mean, nd=none detected

p < 0.05,

p< 0.015

After 24 hours in 0.1% serum where EBV-positive Akata clones demonstrate a growth advantage over EBV-negative Akata clones (Chodosh et al., 1998), there was a statistically significant 2-fold increase in spermine levels in the EBV-positive Akata clones compared to their EBV-negative counterparts (Table 3). Spermine has been shown to function as negative regulator of BCR-mediated apoptosis (Nitta et al., 2001) and as a free radical scavenger (Ha et al., 1998). Spermidine and putrescine were slightly elevated in the EBV-positive Akata clones, suggesting an overall increase in the natural polyamine level in EBV-positive Akata cells. Together, these results confirm that the reduced SAT1 mRNA levels in EBV-positive Akata clones functionally affect polyamine pools, the elevation of which may contribute to the EBV-induced tumor phenotype in Akata BL cells.

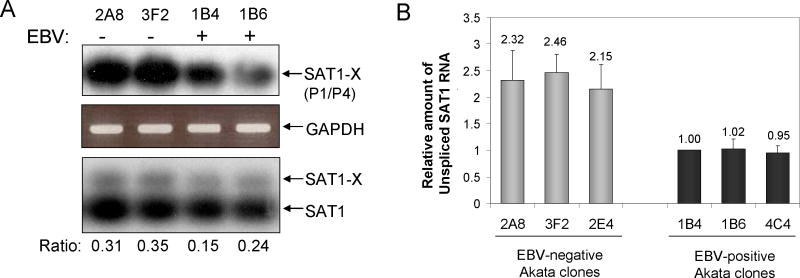

3.6. Transcriptional regulation of SAT1 in EBV-positive Akata

Arboviral and adenoviral infections have previously been shown to induce alternatively spliced, non-functional variants of SAT1, which also occur in response to changes in polyamine concentration, irradiation, and hypoxia (Hyvonen et al., 2006; Nikiforova et al., 2002). One alternatively spliced product, termed SAT1-X, includes an additional 110bp exon X between exons 3 and 4 that results in premature translation termination of SAT1 protein and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (Hyvonen et al., 2006; Nikiforova et al., 2002). A second splice variant deleting exon 4 has also been observed upon infection with the Semliki Forest arbovirus (Nikiforova et al., 2002) (Hyvonen et al., 2006). Since primers for our RQ-RT-PCR assays (Table 1) framed the exon 3:4 junction of SAT1, we examined if increased alternative splicing that interfered with formation of the exon 3:4 junction to decrease in SAT1 mRNA observed in the presence of EBV. First, we examined if alternative spliced variants of SAT1 were generated in Akata clones using primers to SAT1 exon 3 (RQ-SAT1-F) and exon 6 (P6) (Table 1) that would detect all three transcripts. Only two amplicons were detected by Southern blotting, that of standard SAT1 and a larger variant consistent with SAT1-X (data not shown). We confirmed that the larger splice variant was indeed SAT1-X, using RT-PCR primers to exon 1 (P1) coupled with a primer specific for exon X (P4) (Fig. 4A, top panel). The SAT1-X splice variant was detected in both EBV-positive and EBV-negative Akata clones; however, the EBV-positive clones showed decreased SAT1-X comparable to the previously observed reduction in SAT1 mRNA (Fig. 2). To quantify the alternative spliced SAT1-X relative to SAT1, we used the earlier RQ-RT-PCR primers directed to exons 3 and 4 to amplified both SAT1-X and SAT1, determining their relative abundance by Southern hybridization (Fig. 4A, bottom panel). Densitometric analysis of three independent biological replicates showed that the ratio of SAT1-X isoform to SAT1 was slightly lower in EBV-positive clones compared to the EBV-negative clones, excluding the role of alternative splicing in the EBV-dependent reduction in SAT1.

Figure 4.

Mechanism of SAT1 transcriptional repression in EBV-positive and -negative Akata clones. A) Analysis of SAT1 splice variants in EBV-positive and –negative Akata clones. Top panel is RT-PCR using primers P1 and P4 which are specific for exon 1 and exon X amplifying the SAT1-X splice variant. Shown is a Southern hybridization using a random-labeled SAT1 cDNA probe. Middle panel is the ethidium bromide stained gel showing the corresponding loading control showing RT-PCR amplification with primers specific to GAPDH. Bottom panel is a RT-PCR amplification using the real-time primers to SAT1 exon 3 and exon 4. Shown is a Southern hybridization using a random-labeled SAT1 cDNA probe. The ratio of SAT1-X to SAT1 is shown determined from densitometric analysis. B) Analysis of SAT1 pre-mRNA levels in EBV-positive and –negative Akata clones. The levels for SAT1 pre-mRNA was measured by RQ-RT-PCR using primers specific to SAT1 intron 2 and exon 2 and a TaqMan probe. The data was normalized to GAPDH and relative expression was determined using the ΔΔCt method. The mean and SEM from three independent experiments are shown. Relative SAT1 mRNA levels were compared to the value from the 1B4 clone arbitrarily set to 1.

With evidence of two SAT1 transcripts being reduced by EBV, we examined if EBV affected SAT1 at the level of transcription. Using RQ-RT-PCR primers and probes designed to quantify unspliced SAT1 (exon2 and intron 2), EBV-positive clones averaged 1±0.02 SAT1 pre-mRNA transcripts/100ng RNA as compared to 2.3±0.09 SAT1 pre-mRNA transcripts/100ng RNA in their EBV-negative counterparts (Fig. 4B). This 2.3 fold reduction in SAT1 pre-mRNA in EBV-positive Akata BL clones was similar to the reduction observed in spliced transcripts, suggesting regulation by EBV at the level of transcription initiation or pre-mRNA transcript stability.

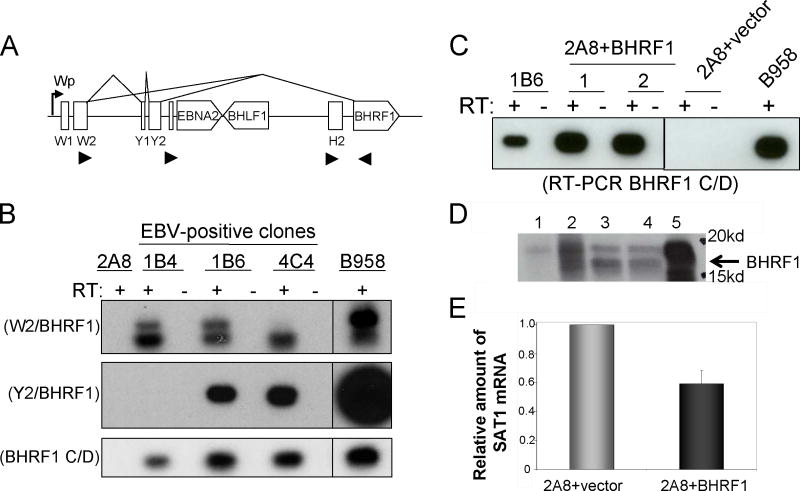

3.7. BHRF1 as a negative modulator of SAT1 expression

To identify the EBV viral gene product responsible for downregulation of SAT1 mRNA levels, EBV-negative Akata cells were transfected with expression vectors carrying EBERs or EBNA1, previously reported to restore the tumorigenic phenotype and enhance survival of the BL cells (Kennedy et al., 2003; Komano et al., 1999; Ruf et al., 2000). In both transient and stable expression of the EBERs or EBNA1 in EBV-negative Akata cells, SAT1 mRNA levels were not altered relative to cells transfected with a vector control (data not shown). Following a hint provided by earlier studies using representation difference analysis of paired Akata clones, BHRF1 mRNA, a viral homolog of the anti-apoptotic factor BCL-2, was detected (unpublished observations, Y. Gan and J. W. Sixbey). Although BHRF1 which could have been produced from a small fraction of Akata BL cells undergoing lytic replication, we examined if a latent form of BHRF1 was expressed in our EBV-positive Akata clones. Latent forms of heterogeneous BHRF1 transcripts that contained spliced leader exons have been reported in a variety of latently-infected B cell lines (Austin et al., 1988; Bodescot and Perricaudet, 1986; Pfitzner et al., 1987). Recently, a Wp promoter linked W/BHRF1-spliced transcript was described that is constitutively expressed as a latent protein in growth-transformed cells and is capable of providing protection against apoptotic stimuli in BL cells (Kelly et al., 2009) (Fig 5A).

Figure 5.

Identification of a negative viral modulator of SAT1 mRNA expression. A) Schematic of alternatively spliced latent BHRF1 transcripts (Kelly et al., 2009). B) Latent BHRF1 expression in EBV-positive Akata BL. BHRF1 expression in 3 EBV-positive clones was determined by RT-PCR using primers specific for W2, Y2, or BHRF1 exons. Shown are Southern hybridizations to RT-PCR products using the various primer pairs. Images were cropped to remove extraneous lanes. Top Panel represents W2/BHRF1 transcripts. Middle panel represents Y2/BHRF1 transcripts. Bottom panel shows BHRF1 transcripts carrying the coding region. B958 was used a positive control, and the EBV-negative 2A8 clone was used as a negative control. RT-positive and RT-negative lanes are indicated. C) BHRF1 mRNA expression in stably transfected in an EBV-negative Akata cell lines. The EBV-negative clone, 2A8, was transfected with a BHRF1 expression plasmid or vector alone as a control, and stable cell lines were generated. Shown is a Southern blot of RT-PCR amplicons using primers to the BHRF1 coding region. D) Detection of BHRF1 protein in transfected EBV-negative 2A8 Akata BL clone. Shown is an immunoblot using a BHRF1 specific antibody. Lanes are 1: vector control; 2: IgG induced EBV+Akata BL; 3 and 4: 2A8+BHRF1; 5: B958 (latency III) as positive control. E) Reduction of SAT1 mRNA in cells stably expressing BHRF1. SAT1 was determined using RQ-RT-PCR as previously described. Vector control was set arbitrarily to 1. Shown is the mean and SEM determined from duplicate seedings of two independently generated stably expressing cell lines.

To determine if a latent form of BHRF1 was expressed in our EBV-positive Akata clones, we used RT-PCR to amplify W2-BHRF1 or Y2-BHRF1 spliced transcripts in our latently infected EBV-positive Akata clones using previously described primers (Kelly et al., 2009; Oudejans et al., 1995; Speck et al., 1999). As shown in Figure 5B (top and middle panels), W2-BHRF1 spliced transcripts were detected in all three clones, and Y2-BHRF1 spliced transcripts were detected in two of three clones. Spliced forms with and without the Y2 exon have been previously reported (Kelly et al., 2009). An additional primer set that amplified only the BHRF1 open reading frame (primers C/D) corroborated presence of the BHRF1 transcript (Fig. 5B, bottom panel). As support for expression of latent forms of BHRF1, the BZLF1 mRNA expression was absent in the 1B6 clone (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, H2/BHRF1 primers (Lear et al., 1992) that detect transcripts initiating from the lytic promoter located immediately upstream in the H2 exon did not yield a product in the 1B6 EBV-positive clones corroborating expression of a latent from of BHRF1 in the EBV-positive Akata BL clones (Fig 3C). We have been unable to detect latent BHRF1 protein in our EBV-positive Akata clones by immunoblot analysis likely due to low levels of expression. In contrast, we are able to detect BHRF1 protein after IgG stimulation of lytic replication (Fig. 5D).

To determine if BHRF1 was responsible for repression of SAT1 expression, we cloned the BHRF1 coding region into the pLXSN expression vector, excluding the 3′ untranslated region of the transcript to exclude potential contributions from encoded viral BHRF microRNAs. The EBV-negative Akata clone, 2A8, was transfected with the BHRF1-expressing vector or the corresponding vector control. As shown in Figure 5C and D, BHRF1 transfected cells expressed the transgene as detected at the mRNA and protein level. Analysis of two independent stable transfectant expressing BHRF1 demonstrated a 40% reduction in SAT1 mRNA as compared to the vector control (Fig. 5E), implicating BHRF1 as a negative modulator of SAT1 mRNA expression in Akata BL.

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated an EBV-dependent reduction in SAT1 mRNA levels in BL, which impacts SAT1 enzyme activity and polymine levels. Evidence from a reinfected EBV-negative clone and single expression of the BHRF1 viral gene product supported EBV in reducing SAT1 mRNA levels. This EBV-dependent reduction in SAT1 becomes a complementary alteration to the c-myc translocation in BL. Downregulation of the catabolic polyamine metabolism by EBV negates the natural compensatory response triggered by c-MYC induction of polyamine biosynthesis, likely preserving c-MYC enhanced polyamine levels required for cell proliferation while reducing polyamine depletion-induced programmed cell death (Ha et al., 1997). The observation of low levels of SAT1 mRNA in two additional BL cell lines that suggested that reduction of SAT1 mRNA levels was favorable event in tumorigenic BL cell lines in the absence of EBV.

In defining the relationship between the presence of EBV and reduction in SAT1 expression, a consistent repression of SAT1 mRNA levels was observed in infected Akata cells under growth and stimulatory conditions known to increase SAT1 expression (Fig. 2 and 3). In a prior study by Yuan, et al. that also examined gene expression changes between EBV-positive and –negative Akata after BCR crosslinking using microarray analysis, SAT1 was not identified as a candidate gene among nearly 200 changes in gene expression (Yuan et al., 2006). The reason for failed detection of SAT1 in the prior study is unknown; however, in our Akata BL cell lines reduction of SAT1 and its consequence was validated by various methods. Although we were unable to directly measure protein levels, reduction in SAT1 mRNA correlated with decreased enzyme activity (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the observation of a 2-fold reduction in acetyl-spermidine in the EBV-positive Akata BL clones compared to their negative counterparts provided a functional consequence for the EBV-dependent reduction in SAT1 mRNA levels (Table 3). While no significant changes in putrescine, spermidine or spermine were measured when grown in serum rich conditions, the decrease in acetyl-spermidine suggested a slower metabolic turnover of polyamines.

Homeostatic mechanisms likely maintain polyamine levels in the EBV-positive clones such that the growth of the EBV-positive and -negative clones did not differ when cultured in serum rich conditions (Persson, 2009). In contrast, under serum starvation conditions where EBV-positive Akata BL clones demonstrated increased survival compared to their EBV-negative counterparts (Chodosh et al., 1998; Komano et al., 1998; Ruf et al., 1999), EBV-positive clones showed a two-fold increase in spermine levels correlating to the ∼2-fold decrease in SAT1 mRNA levels in these cells. Since exogenous addition of spermine can protect against glucocorticoid and B-cell receptor-mediated apoptosis (Hegardt et al., 2001; Nitta et al., 2001), an increase in spermine levels in the EBV-positive Akata cells may confer the resistance to apoptosis reported for the EBV-positive Akata BL cell line in response to serum deprivation (Ruf et al., 1999). Surprisingly, spermine levels in both EBV-positive and -negative Akata BL cells were extremely low. In most cultured mammalian cell systems, spermine and spermidine constituted the majority of the polyamine pool, and their levels are roughly equivalent. To exclude any biases in our HPLC assay, we examined intracellular polyamine pools in two additional EBV-negative BL cell lines (Ramos and BL2). In Ramos BL the ratio of spermidine/spermine was nearly equivalent; in the BL2 cell line, spermine was only 6 times lower than spermidine (data not shown). Since these BL cell lines did not show the ∼350 fold discrepancy in spermidine/spermine ratio seen in Akata BL, such low spermine levels may be characteristic of the Akata BL cell line.

Polyamines play a vital role in the lifecycle of a number of viruses particularly in viral replication. Polyamines (spermidine and spermine) are found within virion preparations from a widespread group of viruses, including influenza (Bachrach et al., 1974), vaccinia (Lanzer and Holowczak, 1975), adenovirus (Shortridge and Stevens, 1973), and herpes simplex (HSV-1) (Gibson and Roizman, 1971). Inhibition of polyamine biosynthesis using the ODC inhibitor, DFMO, diminishes HCMV, vaccinia, and HSV-1 progeny production (Tuomi et al., 1980; Tyms and Williamson, 1982; Williamson, 1985) emphasizing a requirement for polyamines during viral replication. Whereas some viruses enhance polyamine biosynthesis to meet that requirement (Williamson, 1985), a few are known to inhibit polyamine catabolism. Arbovirus and adenovirus family members, for example, induce an alternatively spliced, nonfunctional form of SAT1 mRNA (Hyvonen et al., 2006; Nikiforova et al., 2002). EBV did not induce alternatively spliced variants of SAT1, but repression of SAT1 mRNA was noted at the pre-mRNA level. The mechanism behind this repression is under investigation.

EBV's suppression of SAT1 in face of BCR crosslinking (Fig. 3B) suggested viral regulation of SAT1 as a survival response during EBV lytic replication. Antigenic stimulation is posited as one means for EBV reactivation from latency in vivo. From the standpoint of normal B lymphocyte physiology, signaling through the BCR initiates outcomes that vary from survival, proliferation or apoptosis, depending on activation of co-stimulatory molecules, the maturation state of the B cell, and the antigenic stimulus. BCR-mediated apoptosis involves not only c-MYC, known to be transiently upregulated prior to the onset of apoptosis, but also polyamines, which are reduced after BCR crosslinking (Leider and Melamed, 2003; Nitta et al., 2001). Suppression of SAT1 by EBV after BCR crosslinking would counter this effect to maintain polyamine levels during viral replication. Furthermore, the early lytic gene, BHRF1, and viral BCL2 homolog was identified as a viral mediator potentiating this effect.

BHRF1 is known to enhance survival of BL cells under conditions that otherwise induce cell death by apoptosis (Henderson et al., 1993; Komano and Takada, 2001). Although the mechanism was not addressed here, BHRF1 may act in a similar fashion to BCL-2, where BCL2-overexpression was shown to reduce SAT1 activity to avert polyamine depletion-induced cell death (Holst et al., 2008). Although the authors did not measure the effect of BCL2 overexpression on SAT1 transcripts, they speculated that expression of BCL2 might sequester K-RAS to mitochrondria, limiting its participation with PPAR-gamma to transcriptionally induce SAT1. Whether BHRF1 expression altered K-RAS or PPAR-gamma function is unknown.

Detection of latent forms of BHRF1 in our EBV-positive suggested a role repressing SAT1 not only during lytic replication but also during latency. Although we did not expect to find BHRF1 in latently infected Akata BL cells, the existence of this message in Akata cells was somewhat predicted by detection of BHRF1-derived miRNAs (Pratt et al., 2009). Latent forms of BHRF1 have now been demonstrated to be constitutively expressed in growth transformed lymphocytes where it confers resistance to apoptotic stimuli (Kelly et al., 2009; Kelly et al., 2006). In BL tumors containing an EBNA2-deletion mutant virus, the latent BHRF1 protein was shown to counter the apoptotic effects of c-MYC overexpression and serve as cofactor in BL pathogenesis (Kelly et al., 2009).

In the broader context of how a B-cell transforming human tumor virus complements the cellular genetic alteration represented by translocation of c-myc into an immunoglobulin locus, our results shed light on the significance of perturbations in polyamine metabolism initiated by c-MYC enhancement of ODC. Disruptions of polyamine homeostasis are considered remarkably difficult to achieve, the overexpression of ODC alone typically fails to increase levels of the higher polyamines spermidine and spermine (Janne et al., 2004). What EBV seems to have accomplished by repression of the catabolic activity of SAT1 in the context of ODC overexpression is accumulation of the higher polyamines, as reflected by our detection of elevated levels of spermine in serum deprived Akata cells. Such synchronous alteration of biosynthetic and catabolic arms of polyamine metabolism may be responsible for both the enhanced cell proliferation and the increased protection from apoptosis characteristic of EBV-positive BL.

Highlights.

EBV-positive Akata BL demonstrated reduced SAT1 mRNA levels.

EBV-positive Akata BL showed altered SAT1 enzyme activity and polyamine levels.

Reduction of SAT1 in EBV-positive Akata BL occurred at the level of transcription.

Forced expression of the EBV BCL2 homolog, BHRF1 reduced SAT1 mRNA levels.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank P. Polk for processing microarray experiments, T. Su for technical assistance, and J. Sixbey for his mentorship. This project was supported by a COBRE grant, GM103433, from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and grants from the National Cancer Institute, CA-67372, and CA-114416.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Austin PJ, Flemington E, Yandava CN, Strominger JL, Speck SH. Complex transcription of the Epstein-Barr virus BamHI fragment H rightward open reading frame 1 (BHRF1) in latently and lytically infected B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(11):3678–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach U, Don S, Wiener H. Occurrence of polyamines in myxoviruses. J Gen Virol. 1974;22(3):451–4. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-22-3-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudino TA, Cleveland JL. The Max network gone mad. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(3):691–702. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.691-702.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello-Fernandez C, Packham G, Cleveland JL. The ornithine decarboxylase gene is a transcriptional target of c-Myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(16):7804–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernacki RJ, Bergeron RJ, Porter CW. Antitumor activity of N,N′-bis(ethyl)spermine homologues against human MALME-3 melanoma xenografts. Cancer Res. 1992;52(9):2424–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodescot M, Perricaudet M. Epstein-Barr virus mRNAs produced by alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14(17):7103–14. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.17.7103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borza CM, Hutt-Fletcher LM. Epstein-Barr virus recombinant lacking expression of glycoprotein gp150 infects B cells normally but is enhanced for infection of epithelial cells. J Virol. 1998;72(9):7577–82. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7577-7582.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casero RA, Jr, Pegg AE. Spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase--the turning point in polyamine metabolism. Faseb J. 1993;7(8):653–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Kramer DL, Jell J, Vujcic S, Porter CW. Small interfering RNA suppression of polyamine analog-induced spermidine/spermine n1-acetyltransferase. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64(5):1153–9. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.5.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodosh J, Holder VP, Gan YJ, Belgaumi A, Sample J, Sixbey JW. Eradication of latent Epstein-Barr virus by hydroxyurea alters the growth-transformed cell phenotype. J Infect Dis. 1998;177(5):1194–201. doi: 10.1086/515290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalla-Favera R, Bregni M, Erikson J, Patterson D, Gallo RC, Croce CM. Human c-myc onc gene is located on the region of chromosome 8 that is translocated in Burkitt lymphoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79(24):7824–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel-Petrovic M, Shappell NW, Bergeron RJ, Porter CW. Polyamine and polyamine analog regulation of spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase in MALME-3M human melanoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(25):19118–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel-Petrovic M, Vujcic S, Brown PJ, Haddox MK, Porter CW. Effects of polyamines, polyamine analogs, and inhibitors of protein synthesis on spermidine-spermine N1-acetyltransferase gene expression. Biochemistry. 1996;35(45):14436–44. doi: 10.1021/bi9612273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerner EW, Meyskens FL., Jr Polyamines and cancer: old molecules, new understanding. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(10):781–92. doi: 10.1038/nrc1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson W, Roizman B. Compartmentalization of spermine and spermidine in the herpes simplex virion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68(11):2818–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.11.2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha HC, Sirisoma NS, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL, Woster PM, Casero RA., Jr The natural polyamine spermine functions directly as a free radical scavenger. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(19):11140–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha HC, Woster PM, Yager JD, Casero RA., Jr The role of polyamine catabolism in polyamine analogue-induced programmed cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(21):11557–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegardt C, Andersson G, Oredsson SM. Different roles of spermine in glucocorticoid- and Fas-induced apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2001;266(2):333–41. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson S, Huen D, Rowe M, Dawson C, Johnson G, Rickinson A. Epstein-Barr virus-coded BHRF1 protein, a viral homologue of Bcl-2, protects human B cells from programmed cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(18):8479–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst CM, Johansson VM, Alm K, Oredsson SM. Novel anti-apoptotic effect of Bcl-2: prevention of polyamine depletion-induced cell death. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32(1):66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyvonen MT, Uimari A, Keinanen TA, Heikkinen S, Pellinen R, Wahlfors T, Korhonen A, Narvanen A, Wahlfors J, Alhonen L, Janne J. Polyamine-regulated unproductive splicing and translation of spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase. Rna. 2006;12(8):1569–82. doi: 10.1261/rna.39806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janne J, Alhonen L, Pietila M, Keinanen TA. Genetic approaches to the cellular functions of polyamines in mammals. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271(5):877–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabra PM, Lee HK, Lubich WP, Marton LJ. Solid-phase extraction and determination of dansyl derivatives of unconjugated and acetylated polyamines by reversed-phase liquid chromatography: improved separation systems for polyamines in cerebrospinal fluid, urine and tissue. J Chromatogr. 1986;380(1):19–32. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)83621-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly GL, Long HM, Stylianou J, Thomas WA, Leese A, Bell AI, Bornkamm GW, Mautner J, Rickinson AB, Rowe M. An Epstein-Barr virus anti-apoptotic protein constitutively expressed in transformed cells and implicated in burkitt lymphomagenesis: the Wp/BHRF1 link. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(3):e1000341. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly GL, Milner AE, Baldwin GS, Bell AI, Rickinson AB. Three restricted forms of Epstein-Barr virus latency counteracting apoptosis in c-myc-expressing Burkitt lymphoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(40):14935–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509988103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy G, Komano J, Sugden B. Epstein-Barr virus provides a survival factor to Burkitt's lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(24):14269–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336099100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa N, Goto M, Kurozumi K, Maruo S, Fukayama M, Naoe T, Yasukawa M, Hino K, Suzuki T, Todo S, Takada K. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded poly(A)(-) RNA supports Burkitt's lymphoma growth through interleukin-10 induction. Embo J. 2000;19(24):6742–50. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komano J, Maruo S, Kurozumi K, Oda T, Takada K. Oncogenic role of Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNAs in Burkitt's lymphoma cell line Akata. J Virol. 1999;73(12):9827–31. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9827-9831.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komano J, Sugiura M, Takada K. Epstein-Barr virus contributes to the malignant phenotype and to apoptosis resistance in Burkitt's lymphoma cell line Akata. J Virol. 1998;72(11):9150–6. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9150-9156.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komano J, Takada K. Role of bcl-2 in Epstein-Barr virus-induced malignant conversion of Burkitt's lymphoma cell line Akata. J Virol. 2001;75(3):1561–4. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1561-1564.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalchuk AL, Qi CF, Torrey TA, Taddesse-Heath L, Feigenbaum L, Park SS, Gerbitz A, Klobeck G, Hoertnagel K, Polack A, Bornkamm GW, Janz S, Morse HC., 3rd Burkitt lymphoma in the mouse. J Exp Med. 2000;192(8):1183–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.8.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzer W, Holowczak JA. Polyamines in vaccinia virions and polypeptides released from viral cores by acid extraction. J Virol. 1975;16(5):1254–64. doi: 10.1128/jvi.16.5.1254-1264.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lear AL, Rowe M, Kurilla MG, Lee S, Henderson S, Kieff E, Rickinson AB. The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) nuclear antigen 1 BamHI F promoter is activated on entry of EBV-transformed B cells into the lytic cycle. J Virol. 1992;66(12):7461–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7461-7468.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leider N, Melamed D. Differential c-Myc responsiveness to B cell receptor ligation in B cell-negative selection. J Immunol. 2003;171(5):2446–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby PR, Bergeron RJ, Porter CW. Structure-function correlations of polyamine analog-induced increases in spermidine/spermine acetyltransferase activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38(9):1435–42. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui I, Pegg AE. Effect of inhibitors of protein synthesis on rat liver spermidine N-acetyltransferase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;675(3-4):373–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(81)90028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyskens FL, Jr, Gerner EW. Development of difluoromethylornithine (DFMO) as a chemoprevention agent. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(5):945–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody CA, Scott RS, Amirghahari N, Nathan CO, Young LS, Dawson CW, Sixbey JW. Modulation of the cell growth regulator mTOR by Epstein-Barr virus-encoded LMP2A. J Virol. 2005;79(9):5499–506. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5499-5506.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanbo A, Inoue K, Adachi-Takasawa K, Takada K. Epstein-Barr virus RNA confers resistance to interferon-alpha-induced apoptosis in Burkitt's lymphoma. Embo J. 2002;21(5):954–65. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforova NN, Velikodvorskaja TV, Kachko AV, Nikolaev LG, Monastyrskaya GS, Lukyanov SA, Konovalova SN, Protopopova EV, Svyatchenko VA, Kiselev NN, Loktev VB, Sverdlov ED. Induction of alternatively spliced spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase mRNA in the human kidney cells infected by venezuelan equine encephalitis and tick-borne encephalitis viruses. Virology. 2002;297(2):163–71. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta T, Igarashi K, Yamashita A, Yamamoto M, Yamamoto N. Involvement of polyamines in B cell receptor-mediated apoptosis: spermine functions as a negative modulator. Exp Cell Res. 2001;265(1):174–83. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oudejans JJ, van den Brule AJ, Jiwa NM, de Bruin PC, Ossenkoppele GJ, van der Valk P, Walboomers JM, Meijer CJ. BHRF1, the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) homologue of the BCL-2 protooncogene, is transcribed in EBV-associated B-cell lymphomas and in reactive lymphocytes. Blood. 1995;86(5):1893–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry L, Balana Fouce R, Pegg AE. Post-transcriptional regulation of the content of spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase by N1N12-bis(ethyl)spermine. Biochem J. 1995;305(Pt 2):451–8. doi: 10.1042/bj3050451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson L. Polyamine homoeostasis. Essays Biochem. 2009;46:11–24. doi: 10.1042/bse0460002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfitzner AJ, Tsai EC, Strominger JL, Speck SH. Isolation and characterization of cDNA clones corresponding to transcripts from the BamHI H and F regions of the Epstein-Barr virus genome. J Virol. 1987;61(9):2902–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.9.2902-2909.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt ZL, Kuzembayeva M, Sengupta S, Sugden B. The microRNAs of Epstein-Barr Virus are expressed at dramatically differing levels among cell lines. Virology. 2009;386(2):387–97. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe M, Rowe DT, Gregory CD, Young LS, Farrell PJ, Rupani H, Rickinson AB. Differences in B cell growth phenotype reflect novel patterns of Epstein-Barr virus latent gene expression in Burkitt's lymphoma cells. Embo J. 1987;6(9):2743–51. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02568.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf IK, Rhyne PW, Yang C, Cleveland JL, Sample JT. Epstein-Barr virus small RNAs potentiate tumorigenicity of Burkitt lymphoma cells independently of an effect on apoptosis. J Virol. 2000;74(21):10223–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.21.10223-10228.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf IK, Rhyne PW, Yang H, Borza CM, Hutt-Fletcher LM, Cleveland JL, Sample JT. Epstein-barr virus regulates c-MYC, apoptosis, and tumorigenicity in Burkitt lymphoma. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(3):1651–60. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu N, Tanabe-Tochikura A, Kuroiwa Y, Takada K. Isolation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-negative cell clones from the EBV-positive Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) line Akata: malignant phenotypes of BL cells are dependent on EBV. J Virol. 1994;68(9):6069–73. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6069-6073.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortridge KF, Stevens L. Spermine and spermidine--polyamine components of human type 5 adenovirions. Microbios. 1973;7(25):61–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern EM. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98(3):503–17. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speck P, Kline KA, Cheresh P, Longnecker R. Epstein-Barr virus lacking latent membrane protein 2 immortalizes B cells with efficiency indistinguishable from that of wild-type virus. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(Pt 8):2193–203. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-8-2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada K, Horinouchi K, Ono Y, Aya T, Osato T, Takahashi M, Hayasaka S. An Epstein-Barr virus-producer line Akata: establishment of the cell line and analysis of viral DNA. Virus Genes. 1991;5(2):147–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00571929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub R, Kirsch I, Morton C, Lenoir G, Swan D, Tronick S, Aaronson S, Leder P. Translocation of the c-myc gene into the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus in human Burkitt lymphoma and murine plasmacytoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79(24):7837–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomi K, Mantyjarvi R, Raina A. Inhibition of Semliki Forest and herpes simplex virus production in alpha-difluoromethylornithine-treated cells: reversal by polyamines. FEBS Lett. 1980;121(2):292–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)80365-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyms AS, Williamson JD. Inhibitors of polyamine biosynthesis block human cytomegalovirus replication. Nature. 1982;297(5868):690–1. doi: 10.1038/297690a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner HJ, Scott RS, Buchwald D, Sixbey JW. Peripheral blood lymphocytes express recombination-activating genes 1 and 2 during Epstein-Barr virus-induced infectious mononucleosis. J Infect Dis. 2004;190(5):979–84. doi: 10.1086/423211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson JD. Polyamine metabolism and virus replication. Biochem Soc Trans. 1985;13(2):331–2. doi: 10.1042/bst0130331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Casero RA., Jr Differential transcription of the human spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase (SSAT) gene in human lung carcinoma cells. Biochem J. 1996;313(Pt 2):691–6. doi: 10.1042/bj3130691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Cahir-McFarland E, Zhao B, Kieff E. Virus and cell RNAs expressed during Epstein-Barr virus replication. J Virol. 2006;80(5):2548–65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2548-2565.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D, Qi CF, Morse HC, 3rd, Janz S, Stevenson FK. Deregulated expression of the Myc cellular oncogene drives development of mouse “Burkitt-like” lymphomas from naive B cells. Blood. 2005;105(5):2135–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]