Abstract

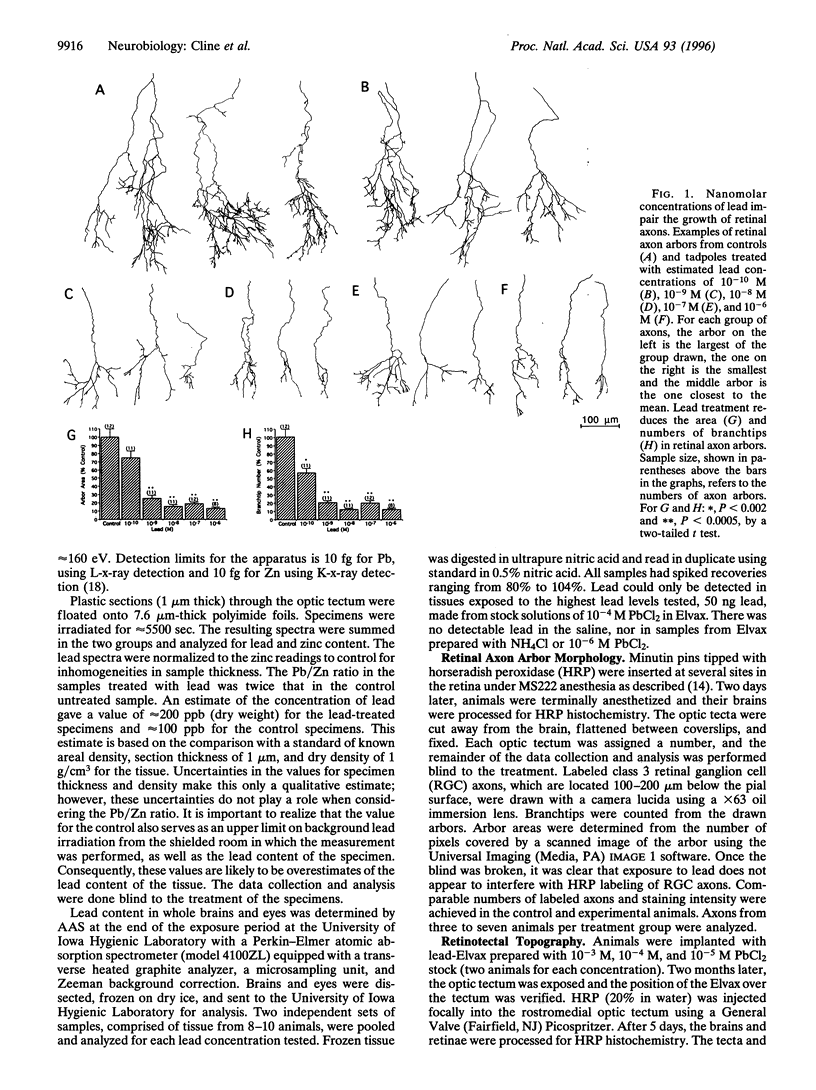

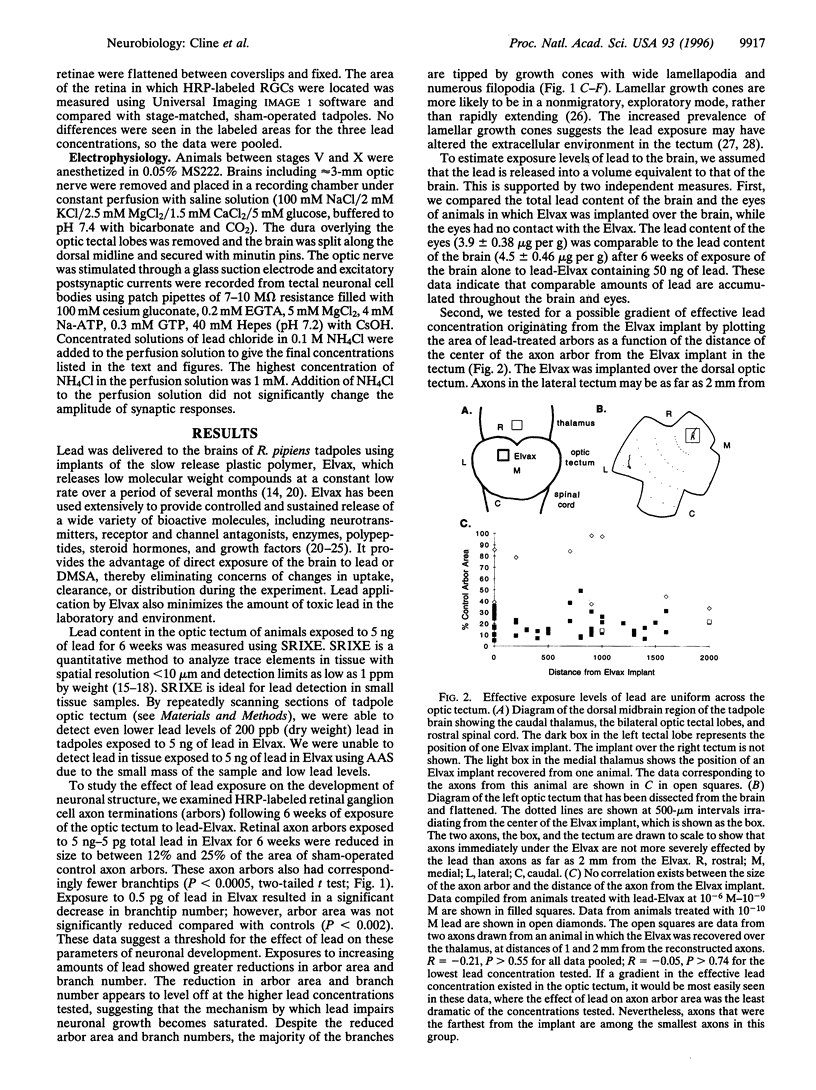

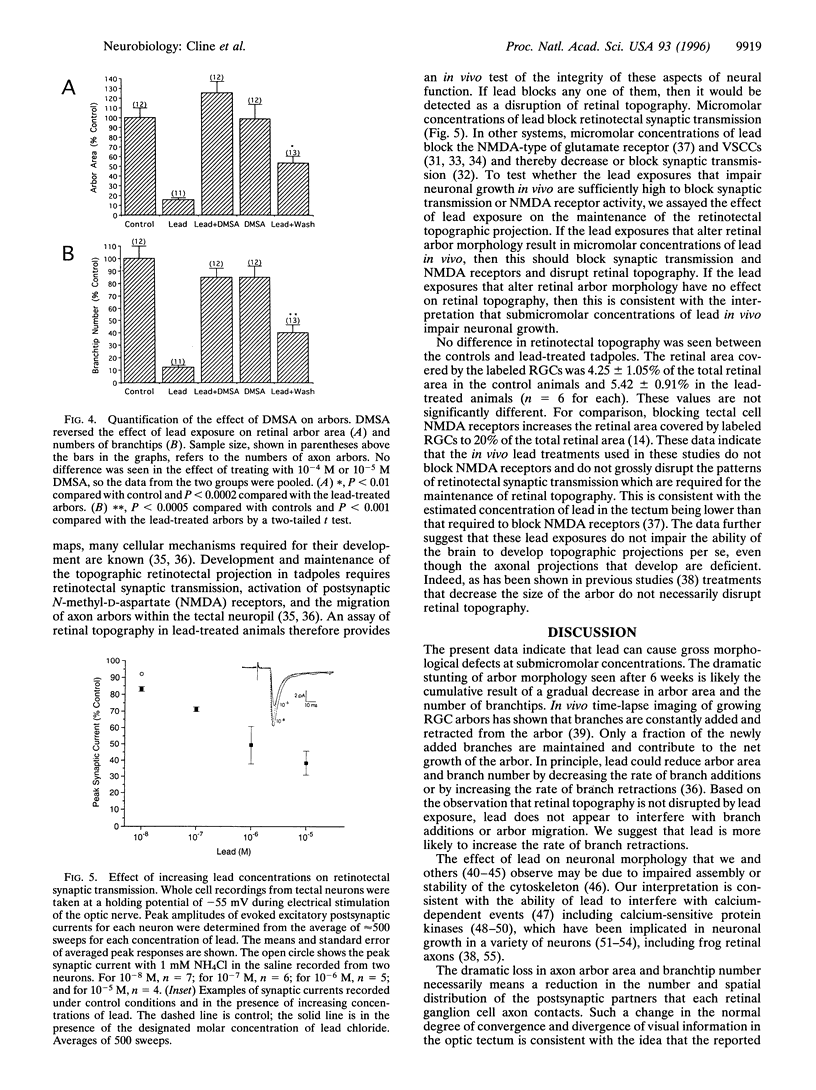

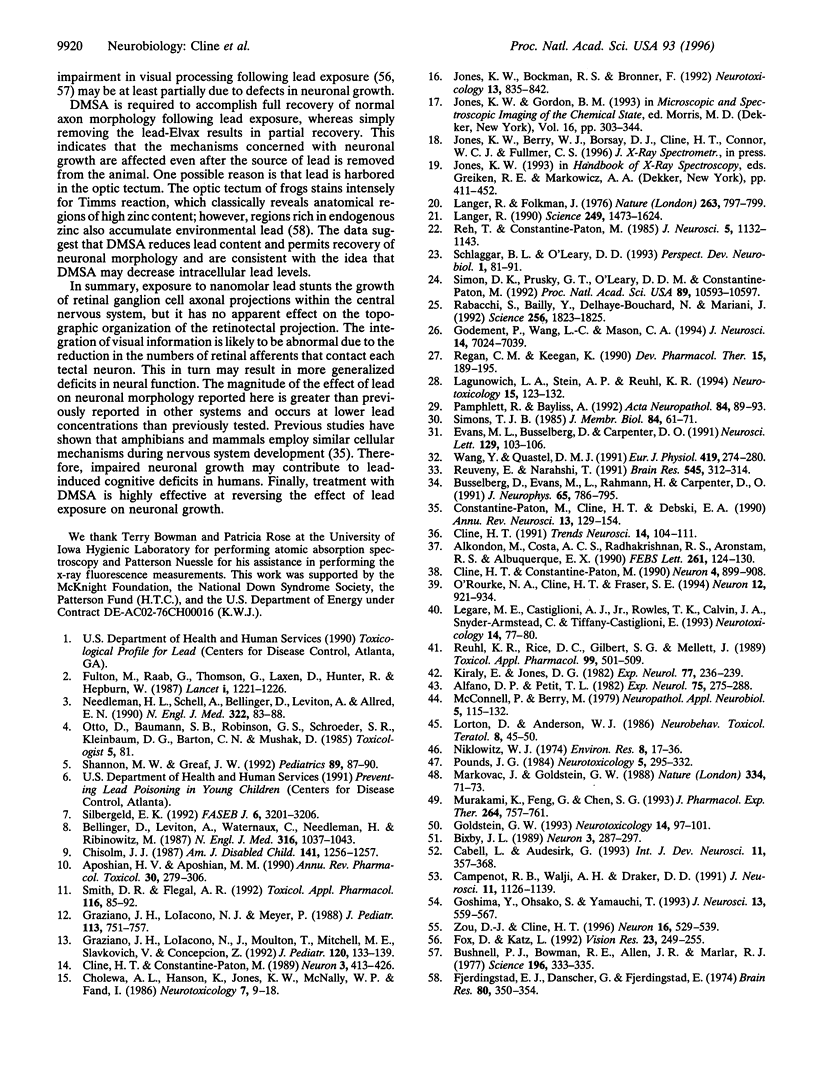

The developing brain is particularly susceptible to lead toxicity; however, the cellular effects of lead on neuronal development are not well understood. The effect of exposure to nanomolar concentrations of lead on several parameters of the developing retinotectal system of frog tadpoles was tested. Lead severely reduced the area and branchtip number of retinal ganglion cell axon arborizations within the optic tectum at submicromolar concentrations. These effects of lead on neuronal growth are more dramatic and occur at lower exposure levels than previously reported. Lead exposure did not interfere with the development of retinotectal topography. The deficient neuronal growth does not appear to be secondary to impaired synaptic transmission, because concentrations of lead that stunted neuronal growth were lower than those required to block synaptic transmission. Subsequent treatment of lead-exposed animals with the chelating agent 2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid completely reversed the effect of lead on neuronal growth. These studies indicate that impaired neuronal growth may be responsible in part for lead-induced cognitive deficits and that chelator treatment counteracts this effect.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alfano D. P., Petit T. L. Neonatal lead exposure alters the dendritic development of hippocampal dentate granule cells. Exp Neurol. 1982 Feb;75(2):275–288. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(82)90160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M., Costa A. C., Radhakrishnan V., Aronstam R. S., Albuquerque E. X. Selective blockade of NMDA-activated channel currents may be implicated in learning deficits caused by lead. FEBS Lett. 1990 Feb 12;261(1):124–130. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80652-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aposhian H. V., Aposhian M. M. meso-2,3-Dimercaptosuccinic acid: chemical, pharmacological and toxicological properties of an orally effective metal chelating agent. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1990;30:279–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.30.040190.001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger D., Leviton A., Waternaux C., Needleman H., Rabinowitz M. Longitudinal analyses of prenatal and postnatal lead exposure and early cognitive development. N Engl J Med. 1987 Apr 23;316(17):1037–1043. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704233161701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixby J. L. Protein kinase C is involved in laminin stimulation of neurite outgrowth. Neuron. 1989 Sep;3(3):287–297. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell P. J., Bowman R. E., Allen J. R., Marlar R. J. Scotopic vision deficits in young monkeys exposed to lead. Science. 1977 Apr 15;196(4287):333–335. doi: 10.1126/science.403610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büsselberg D., Evans M. L., Rahmann H., Carpenter D. O. Lead and zinc block a voltage-activated calcium channel of Aplysia neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1991 Apr;65(4):786–795. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.4.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabell L., Audesirk G. Effects of selective inhibition of protein kinase C, cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase, and Ca(2+)-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase on neurite development in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1993 Jun;11(3):357–368. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(93)90007-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campenot R. B., Walji A. H., Draker D. D. Effects of sphingosine, staurosporine, and phorbol ester on neurites of rat sympathetic neurons growing in compartmented cultures. J Neurosci. 1991 Apr;11(4):1126–1139. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-04-01126.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisolm J. J., Jr Mobilization of lead by calcium disodium edetate. A reappraisal. Am J Dis Child. 1987 Dec;141(12):1256–1257. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1987.04460120018020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholewa M., Hanson A. L., Jones K. W., McNally W. P., Fand I. Regional distribution of lead in the brains of lead-intoxicated adult mice. Neurotoxicology. 1986 Spring;7(1):9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline H. T. Activity-dependent plasticity in the visual systems of frogs and fish. Trends Neurosci. 1991 Mar;14(3):104–111. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline H. T., Constantine-Paton M. NMDA receptor antagonists disrupt the retinotectal topographic map. Neuron. 1989 Oct;3(4):413–426. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline H. T., Constantine-Paton M. The differential influence of protein kinase inhibitors on retinal arbor morphology and eye-specific stripes in the frog retinotectal system. Neuron. 1990 Jun;4(6):899–908. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantine-Paton M., Cline H. T., Debski E. Patterned activity, synaptic convergence, and the NMDA receptor in developing visual pathways. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:129–154. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. L., Büsselberg D., Carpenter D. O. Pb2+ blocks calcium currents of cultured dorsal root ganglion cells. Neurosci Lett. 1991 Aug 5;129(1):103–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90730-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjerdingstad E. J., Danscher G., Fjerdingstad E. Hippocampus: selective concentration of lead in the normal rat brain. Brain Res. 1974 Nov 15;80(2):350–354. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90699-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox D. A., Katz L. M. Developmental lead exposure selectively alters the scotopic ERG component of dark and light adaptation and increases rod calcium content. Vision Res. 1992 Feb;32(2):249–255. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(92)90134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton M., Raab G., Thomson G., Laxen D., Hunter R., Hepburn W. Influence of blood lead on the ability and attainment of children in Edinburgh. Lancet. 1987 May 30;1(8544):1221–1226. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92683-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godement P., Wang L. C., Mason C. A. Retinal axon divergence in the optic chiasm: dynamics of growth cone behavior at the midline. J Neurosci. 1994 Nov;14(11 Pt 2):7024–7039. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-07024.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein G. W. Evidence that lead acts as a calcium substitute in second messenger metabolism. Neurotoxicology. 1993 Summer-Fall;14(2-3):97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshima Y., Ohsako S., Yamauchi T. Overexpression of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in Neuro2a and NG108-15 neuroblastoma cell lines promotes neurite outgrowth and growth cone motility. J Neurosci. 1993 Feb;13(2):559–567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00559.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano J. H., Lolacono N. J., Meyer P. Dose-response study of oral 2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid in children with elevated blood lead concentrations. J Pediatr. 1988 Oct;113(4):751–757. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80396-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano J. H., Lolacono N. J., Moulton T., Mitchell M. E., Slavkovich V., Zarate C. Controlled study of meso-2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid for the management of childhood lead intoxication. J Pediatr. 1992 Jan;120(1):133–139. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80618-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K. W., Bockman R. S., Bronner F. Microdistribution of lead in bone: a new approach. Neurotoxicology. 1992 Winter;13(4):835–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiràly E., Jones D. G. Dendritic spine changes in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells after postnatal lead treatment: a Golgi study. Exp Neurol. 1982 Jul;77(1):236–239. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(82)90158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagunowich L. A., Stein A. P., Reuhl K. R. N-cadherin in normal and abnormal brain development. Neurotoxicology. 1994 Spring;15(1):123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer R., Folkman J. Polymers for the sustained release of proteins and other macromolecules. Nature. 1976 Oct 28;263(5580):797–800. doi: 10.1038/263797a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legare M. E., Castiglioni A. J., Jr, Rowles T. K., Calvin J. A., Snyder-Armstead C., Tiffany-Castiglioni E. Morphological alterations of neurons and astrocytes in guinea pigs exposed to low levels of inorganic lead. Neurotoxicology. 1993 Spring;14(1):77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorton D., Anderson W. J. Altered pyramidal cell dendritic development in the motor cortex of lead intoxicated neonatal rats. A Golgi study. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1986 Jan-Feb;8(1):45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markovac J., Goldstein G. W. Picomolar concentrations of lead stimulate brain protein kinase C. Nature. 1988 Jul 7;334(6177):71–73. doi: 10.1038/334071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell P., Berry M. The effects of postnatal lead exposure on Purkinje cell dendritic development in the rat. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1979 Mar-Apr;5(2):115–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1979.tb00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K., Feng G., Chen S. G. Inhibition of brain protein kinase C subtypes by lead. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993 Feb;264(2):757–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman H. L., Schell A., Bellinger D., Leviton A., Allred E. N. The long-term effects of exposure to low doses of lead in childhood. An 11-year follow-up report. N Engl J Med. 1990 Jan 11;322(2):83–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199001113220203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niklowitz W. J. Ultrastructural effects of acute tetraethyllead poisoning on nerve cells of the rabbit brain. Environ Res. 1974 Aug;8(1):17–36. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(74)90060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke N. A., Cline H. T., Fraser S. E. Rapid remodeling of retinal arbors in the tectum with and without blockade of synaptic transmission. Neuron. 1994 Apr;12(4):921–934. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamphlett R., Bayliss A. The effect of nerve crush and botulinum toxin on lead uptake in motor axons. Acta Neuropathol. 1992;84(1):89–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00427220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pounds J. G. Effect of lead intoxication on calcium homeostasis and calcium-mediated cell function: a review. Neurotoxicology. 1984 Fall;5(3):295–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabacchi S., Bailly Y., Delhaye-Bouchaud N., Mariani J. Involvement of the N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor in synapse elimination during cerebellar development. Science. 1992 Jun 26;256(5065):1823–1825. doi: 10.1126/science.1352066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan C. M., Keegan K. Neuroteratological consequences of chronic low-level lead exposure. Dev Pharmacol Ther. 1990;15(3-4):189–195. doi: 10.1159/000457645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reh T. A., Constantine-Paton M. Eye-specific segregation requires neural activity in three-eyed Rana pipiens. J Neurosci. 1985 May;5(5):1132–1143. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-05-01132.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuhl K. R., Rice D. C., Gilbert S. G., Mallett J. Effects of chronic developmental lead exposure on monkey neuroanatomy: visual system. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1989 Jul;99(3):501–509. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(89)90157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuveny E., Narahashi T. Potent blocking action of lead on voltage-activated calcium channels in human neuroblastoma cells SH-SY5Y. Brain Res. 1991 Apr 5;545(1-2):312–314. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91304-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaggar B. L., O'Leary D. D. Patterning of the barrel field in somatosensory cortex with implications for the specification of neocortical areas. Perspect Dev Neurobiol. 1993;1(2):81–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon M. W., Graef J. W. Lead intoxication in infancy. Pediatrics. 1992 Jan;89(1):87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbergeld E. K. Mechanisms of lead neurotoxicity, or looking beyond the lamppost. FASEB J. 1992 Oct;6(13):3201–3206. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.13.1397842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D. K., Prusky G. T., O'Leary D. D., Constantine-Paton M. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists disrupt the formation of a mammalian neural map. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Nov 15;89(22):10593–10597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons T. J. Influence of lead ions on cation permeability in human red cell ghosts. J Membr Biol. 1985;84(1):61–71. doi: 10.1007/BF01871648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. R., Flegal A. R. Stable isotopic tracers of lead mobilized by DMSA chelation in low lead-exposed rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992 Sep;116(1):85–91. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90148-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. X., Quastel D. M. Actions of lead on transmitter release at mouse motor nerve terminals. Pflugers Arch. 1991 Oct;419(3-4):274–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00371107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou D. J., Cline H. T. Expression of constitutively active CaMKII in target tissue modifies presynaptic axon arbor growth. Neuron. 1996 Mar;16(3):529–539. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]