Abstract

Although mucin-type O-glycans are critical for Cryptosporidium infection, the enzymes catalyzing their synthesis have not been studied. Here, we report four UDP N-acetyl-α-d-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferases (ppGalNAc-Ts) from the genomes of C. parvum, C. hominis and C. muris. All are Type II membrane proteins which include a cytoplasmic tail, a transmembrane domain, a stem region, a glycosyltransferase family 2 domain and a C-terminal ricin B lectin domain. All are expressed during C. parvum infection in vitro, with Cp-ppGalNAc-T1 and -T4 expressed at 24 h and Cp-ppGalNAc-T2 and -T3 at 48 and 72 h post-infection, suggesting that their expression may be developmentally regulated. C. parvum sporozoite lysates display ppGalNAc-T enzymatic activity against non-glycosylated and pre-glycosylated peptides suggesting that they contain enzymes capable of glycosylating both types of substrates. The importance of mucin-type O-glycans in Cryptosporidium–host cell interactions raises the possibility that Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts may serve as targets for intervention in cryptosporidiosis.

Keywords: O-glycosylation, Mucin, Mucin-like glycoprotein, Cryptosporidium, UDP GalNAc:polypeptide, N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase

Cryptosporidium species are water-borne apicomplexan parasites, which cause gastrointestinal disease worldwide [1] which can be particularly devastating in immunocompromised individuals, such as untreated AIDS patients or malnourished children in developing countries. Nitazoxanide, the only drug approved for treatment of cryptosporidiosis in immunocompetent individuals by the US Food and Drug Administration is not effective in the immunocompromised.

Mucin-type O-glycosylation is a critical post-translational modification in Cryptosporidium species. Unlike other apicomplexans, Cryptosporidium employs O-glycosylated mucin-like glycoproteins to attach to and infect intestinal epithelial cells [2]. In addition, the Cryptosporidium genomes contain several additional genes which are predicted to encode mucins or mucin-like glycoproteins [3,4].

Previously, we showed that the O-glycans on mucin-like glycoproteins gp900 and gp40 display terminal O-linked glycans GalNAcα1-Ser/Thr and/or Galβ1–3GalNAcα1-Ser/Thr, the Tn and T antigens respectively [5]. Lectins specific for these O-glycans block attachment and irreversibly inhibit infection of host cells in vitro [5,6]. A monoclonal antibody 4E9 directed against these O-glycans inhibits infection in vitro [5] and in vivo (Ward H., unpublished). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that mucin-type O-glycans are crucial for Cryptosporidium species infection. However, the enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of O-glycans in Cryptosporidium have not been studied.

Mucin type O-glycosylation is initiated by UDP N-acetyl-α-d-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferases (ppGalNAc-Ts, EC 2.4.1.41), which transfer αGalNAc from UDP-GalNAc to the hydroxyl group of serine or threonine residues on acceptor proteins [7,8]. Different isoforms of ppGalNAc-Ts display unique, as well as overlapping, substrate specificities with some functioning as “initiating” enzymes that transfer GalNAc to unmodified peptide substrates, whereas others function as “follow-up” enzymes that transfer GalNAc to peptides pre-glycosylated with αGalNAc [7,8]. ppGalNAcTs are evolutionarily conserved and were identified in a wide variety of organisms ranging from mammals to protozoa. Currently, there are 94 distinct ppGalNAc-T gene families [7]. The human genome encodes 20 ppGalNAc-Ts, many of which were functionally characterized [8]. Among protozoa, ppGalNAcTs have thus far only been reported in Toxoplasma gondii [9–11].

Mining of the C. parvum genome in CryptoDB (www.cryptodb.org) [12] revealed four genes (gene IDs cgd7_4160, cgd6_1960, cgd5_690 and cgd7_1310) encoding putative ppGalNAc-Ts, which we named C. parvum (Cp)-ppGalNAc-T1, T2, T3 and T4, respectively. Sequences encoding all four genes were PCR-amplified from C. parvum (Iowa isolate, obtained from Bunch Grass Farms, ID) genomic DNA using specific primers (Table S1), cloned into the TOPO pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and their sequences verified. Orthologs of Cp-ppGalNAc-T1, T2, T3 and T4 were identified in the genomes of C. hominis (gene IDs Chro. 70461, Chro. 60231, Chro. 50322 and Chro. 70457 respectively) and C. muris (gene IDs CMU 014290, CMU 007930, CMU 041230 and CMU 014290 respectively) in CryptoDB. The Ch-ppGalNAc-T1 and Cp and Ch-ppGalNAc-T4 genes were incompletely annotated in CryptoDB and lacked the 5′ regions encoding putative transmembrane domains and cytoplasmic tails for Cp and Ch-ppGalNAc-T4 and the 3′ region for Ch-ppGalNAc-T1. These regions were identified from their respective contigs using the correctly annotated C. muris (for Cp and Ch-ppGalNAc-T4) and C. parvum (for Ch-ppGalNAc-T1) genes as templates. The sequences of these regions were confirmed by cloning (into the TOPO pCR2.1 vector) and sequencing them from C. hominis genomic DNA (TU502 isolate, obtained from Dr. Saul Tzipori, Tufts University Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, N. Grafton, MA) for Ch-ppGalNAc-T1 and C. parvum genomic DNA for Cp-ppGalNAc-T4.

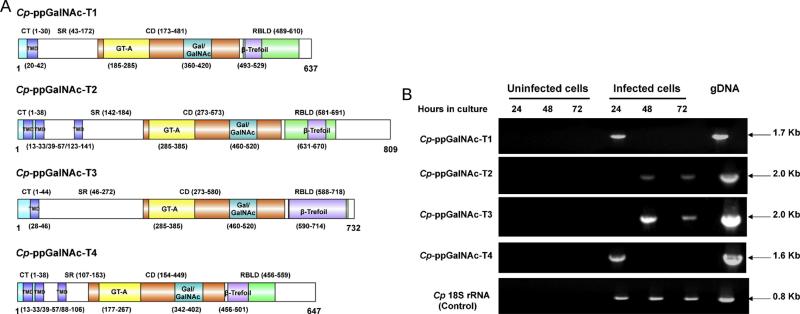

Analysis of the completely annotated sequences from all three species revealed that, like most other Cryptosporidium genes, those encoding ppGalNAcs-T1, 2 and 3 do not contain introns. However, ppGalNAc-T4 from all three species contains a short intron at their 5′ ends. Analysis of the deduced amino sequences indicate that all four ppGalNAc-Ts from each Cryptosporidium species are Type II membrane proteins which display the characteristic domain structure of ppGalNAc-Ts, including a short amino-terminal cytoplasmic tail, one or more N-terminal transmembrane domains, a stem region, a glycosyltransferase family 2 domain and a ricin B lectin domain (schematics depicting the Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts domain structures are shown in Fig. 1A). The first exon of the ppGalNAc-T4s encodes the cytoplasmic tail and first transmembrane domain; the second exon encodes the transmembrane domain, stem region, glycosyltransferase family 2 domain and ricin B lectin domain.

Fig. 1.

(A) Domain structure of Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts. The domain structure of Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts was predicted using the InterProScan server (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/pfa/iprscan/). The presence of a transmembrane domain (TMD) was predicted using InterProScan and TMHMM Server v. 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/). CT, cytoplasmic tail; SR, stem region; CD, catalytic domain; GT-A, glycosyl transferase A domain; RBLD, ricin B lectin domain. The GT-A domain contains a Gal/GalNAc motif, and the RBLD contains a β Trefoil fold. B. Time course of expression of Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts in C. parvum-infected HCT-8 cells. HCT-8 cells were infected with C. parvum oocysts for 24, 48 and 72 h. RT-PCR was performed on total RNA extracted from uninfected and C. parvum-infected HCT-8 cells using the primers listed in Table S1 as described [20]. RNA from uninfected cells was used as a negative control. RT-PCR reactions without added reverse transcriptase were performed to exclude the presence of contaminating DNA. Genomic DNA was used as a positive control and the 18S rRNA gene was used as an internal control.

Interestingly, ppGalNAc-T2 and -T4 from all three Cryptosporidium species have three transmembrane helices, as compared to most other known ppGalNAc-Ts, which have a single transmembrane domain. The GT-A motif of all Cryptosporidium ppGalNAc-T catalytic domains contain the conserved, invariant DXH Mn2+ cation binding motif (not shown). Similarly, they all contain the conserved DXXXXXWGXENXE sequence containing invariant D, E and E residues in the Gal/GalNAc-T motif and display the typical α, β and γ repeats in the ricin B lectin domain (not shown).

The deduced amino acid sequences of Cp-ppGalNAc-T1-T4 were aligned with the C. hominis and C. muris orthologs and with human homologs (Tables S2 and S3). Within each Cryptosporidium species, identity among the four different ppGalNAc-Ts ranged from 12 to 36% for C. parvum, 10 to 37% for C. hominis and 13 to 44% for C. muris. However, among these three, the ppGalNAc-T orthologs were more similar to each other (63–99% identity for Cp-ppGalNAc-T1, 44–98% for Cp-ppGalNAc-T2, 51–98% for Cp-ppGalNAc-T3 and 57–97% for Cp-ppGalNAc-T4) than to the other Cp-ppGalNAc-T isoforms within the same species. Identities of Cryptosporidium species ppGalNAc-Ts with human homologs ranged from 12 to 27% (Table S3).

We searched EupathDB (http://eupathdb.org/eupathdb/) [13] for ppGalNAc-Ts in the genomes of other apicomplexan parasites using the Cp-ppGalNAc-T sequences for BLAST comparison. In addition to the previously identified ppGalNAc-Ts from Toxoplasma gondii [9], we identified ppGalNAc-Ts containing the characteristic glycosyltransferase family 2 and ricin B lectin domains in Neospora caninum (gene IDs NCLIV_0272, NCLIV_0277, NCLIV_010830, NCLIV_067480 and NCLIV_029020) and Eimeria tenella (gene IDs ETH_00002780, ETH_00005370, ETH_00029115). Interestingly, among the apicomplexan genomes sequenced to date, ppGalNAc-Ts were only identified in Cryptosporidium, Toxoplasma, Neospora and Eimeria species, all of which form environmentally-resistant oocysts and invade the gastrointestinal tract of humans and other animals. However, these enzymes were not identified in the genomes of other apicomplexans including Plasmodium, Babesia or Theileria, all of which are vector-borne hemoparasites. The findings that O-glycans are present in Cryptosporidium [5,6], Toxoplasma [14] and Eimeria [15], but not in Plasmodium, Babesia or Theileria species are consistent with the lack of ppGalNAc-Ts in the latter three apicomplexans.

The presence of expressed sequence tags (in CryptoDB) for each of the Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts indicated that all four are expressed at the RNA level. To confirm this and to determine their transcriptional profile during infection in vitro, we performed reverse transcription (RT) PCR on RNA extracted from C. parvum-infected-HCT-8 cells at 24, 48 and 72 h post infection using primers specific for each (Table S1). All four Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts were expressed, though at different times during intracellular development. Cp-ppGalNAc-T-1 and 4 were expressed at 24 h post-infection, whereas Cp-ppGalNAc-T2 and T3 were expressed at 48 and 72 h post-infection (Fig. 1B).

Recent data on the transcriptome of intracellular stages of C. parvum (assessed by high throughput real time PCR at varying time points ranging from 2 to 72 h post-infection) [16] indicated that all four ppGalNAcTs are expressed throughout infection in vitro. However, in this study relative expression levels of all four ppGalNAcTs varied considerably at different time points during infection as well as among four different time course experiments. The median time of maximal expression (normalized to that of the 18S rRNA gene) as reported in CryptoDB was 36, 12, 36 and 24 h post-infection for CpppGalNAc-T-1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively. Another recent study which analyzed the C. parvum transcriptome in oocysts using microarray technology [17] indicated that Cp-ppGalNAc-T1 is not expressed in this stage and that Cp-ppGalNAcs-T3 and T4 are in the lowest quartile of those genes expressed in oocysts. Information on expression of Cp-ppGalNAc-T4 in oocysts was not provided.

Because C. parvum infection in vitro is asynchronous, it is not possible to assign expression to a particular developmental stage at a given time point post-infection. However, O-glycans have been identified in multiple developmental stages suggesting that differential expression may indicate developmental regulation of Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts. Different ppGalNAc-T isoforms in higher eukaryotes, including humans, are also differentially expressed in specific cells or tissues [7]. Clearly, additional studies are required to determine whether expression of Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts is developmentally regulated.

Since Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts are expressed at the RNA level, we then determined if ppGalNAc-T activity could be detected in C. parvum sporozoite lysates. Excysted sporozoites were lysed in 0.5 ml of 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 7.2 containing 1% Triton X-100, 135 mM NaCl, 10 mM MnCl2 containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, IL), and incubated on ice for 2 h. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 9100 × g for 25 min and designated “spropozoite lysate”. The protein content of lysates was measured using a Pierce micro BCA kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Two different assays were used to measure enzyme activity in sporozoite lysates. In the first, activity was measured by quantifying transfer of [14C]-labeled GalNAc to synthetic biotinylated peptides and glycopeptides as described [11]. Because the endogenous C. parvum peptide/glycopeptide acceptors are unknown, we used “standard” peptides/glycopeptides derived from known mucins that have been used to evaluate other ppGalNAc-Ts. As shown in Table 1, C. parvum sporozoite lysates did indeed exhibit ppGalNAc-T activity. Equivalent activity was detected using both peptide (EA2, N or C-terminally biotinylated) and glycopeptide (EA2-2, which is pre-glycosylated with αGalNAc on the second {Thr} residue) acceptors, suggesting the presence of both “initiating” and “follow up” enzyme activity in C. parvum. However, EA2-7 which is pre-glycosylated with αGalNAc on the 7th (Thr) residue was not glycosylated suggesting that Cp-ppGalNAcTs may not display specificity for this substrate. This substrate specificity is different from that of recombinant T. gondii enzymes Tg-ppGalNAc-T1, which did not glycosylate EA2, EA2-2 or EA2-7 [10] and Tg-ppGalNAc-T3 which did not glycosylate EA2 or EA2-2 but did glycosylate EA2-7 [11] using the same assay. Non-glycosylated MUC5AC (N or C-terminally biotinylated) was not glycosylated whereas MU5AC 3, 13 which is pre-glycosylated on the 3rd and 13th residue was glycosylated by the C. parvum sporozoite lysate as well as by recombinant Tg-ppGalNAc-T1 and 3 [10,11]. Interestingly, the non-glycosylated GRA2 peptide derived from the T. gondii GRA2 glycoprotein [18] was robustly glycosylated by the C. parvum sporozoite lysate but not by Tg-ppGalNAc-T1 and 3 [10,11].

Table 1.

ppGalNAc-T activity in C. parvum sporozoite lysates.

| Acceptor name | Acceptor sequence | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Biotin-EA2 | Biotin-PTTDSTTPAPTTK | 198.0 |

| 2. Biotin-EA2-2 | Biotin-PTTDSTTPAPTTK | 179.1 |

| 3. Biotin-EA2-7 | Biotin-PTTDSTTPAPTTK | 13.5 |

| 4. Biotin-MUC5AC | Biotin-GTTPSPVPTTSTTSAP | 18.8 |

| 5. Biotin-MUC5AC-3,13 | Biotin-GTTPSPVPTTSTTSAP | 93.3 |

| 6. MUC5AC-biotin | GTTPSPVPTTSTTSAPK-biotin | 0 |

| 7. EA2-biotin | PTTDSTTPAPTTK-biotin | 177.5 |

| 8. GRA2-biotin | VESDRSTTTTQAPK-biotin | 273.8 |

The transfer of [14C] GalNAc to biotinylated peptides (Alpha Diagnostics International, San Antonio, TX) by ppGalNAc-Ts in sporozoite lysates was quantified, as described previously [11]. The pre-glycosylated peptides (residues in bold and underlined) which were pre-glycosylated with αGalNAc were obtained from Dr. Carolyn Bertozzi (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Enzyme activity was expressed as nmoles of UDP-GalNAc transferred per mg of protein per minute (nmol GalNAc/mg/min).

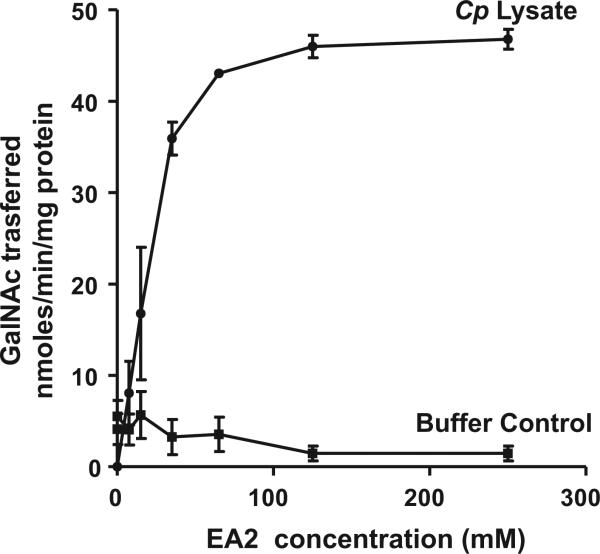

The second assay is an enzyme-linked lectin assay (ELLA), which was developed for high throughput screening of inhibitors of mammalian ppGalNAc-Ts using EA2 as an acceptor peptide [19]. Briefly, increasing concentrations of biotinylated EA2 acceptor peptide and the sugar nucleotide donor UDP-GalNAc were incubated with C. parvum sporozoite lysate and then added to 96-well neutravidin-coated plates. The immobilized glycopeptide product was detected using the αGalNAc-specific lectin, Helix pomatia agglutinin (HPA) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase followed by addition of a chromogenic substrate. As seen in Fig. 2, GalNAc transfer increased with increasing concentrations of the EA2 peptide. Maximum activity was obtained at 100 μM EA2, after which activity plateaued. These data confirm the presence of initiating ppGalNAc-T enzymatic activity with the EA2 peptide in C. parvum sporozoites. However, the specific Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts responsible for this activity and their substrate specificities remain to be determined.

Fig. 2.

ppGalNAc-T enzymatic activity in C. parvum lysates. Enzyme activity in C. parvum sporozoite lysates was measured with increasing concentrations of the EA2 peptide as an acceptor substrate using an enzyme linked lectin assay (ELLA) as described [19]. Assays were performed in duplicate and the data shown are the mean ± SE of two independent assays.

In conclusion, in this study, we identified, cloned and characterized in silico a family of four C. parvum ppGalNAc-Ts and identified orthologs of each of them in C. hominis and C. muris as well as homologs in the related apicomplexan parasites N. caninum and E. tenella. We showed that all four Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts are differentially expressed during infection in vitro and quantified initiating and follow up ppGalNAc-T enzymatic activity in C. parvum. Current efforts are directed at expressing enzymatically active recombinant forms of all four Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts to determine which of them display initiating and/or follow up activity, to identify the native C. parvum peptide and glycopeptide substrates which are O-glycosylated by these enzymes, to determine whether they are developmentally regulated and to elucidate their role in C. parvum-host cell interactions.

Because O-glycans are crucial for C. parvum infection of host cells, Cp-ppGalNAc-Ts may serve as therapeutic targets for drug development against cryptosporidiosis. If so, it may be possible to design specific inhibitors that target parasite, but not host, enzymes. Characterization of the structure and function of these enzymes is essential in order to investigate this possibility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Anne Kane, Tufts Medical Center, for preparation of reagents and for helpful discussions. We also thank Richard Cummings, Emory University School of Medicine, Eric Bennett, University of Copenhagen, Kami Kim and Louis Weiss, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI52786 and R21 AI102813 to HW. MD is supported by NIH T32 AI07077 to Tufts University Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences, Program in Immunology. CC was supported by NIH grant R25HL007785 to Tufts University Building Diversity in Biomedical Sciences Program.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.molbiopara.2013.08.002.

References

- 1.Collinet-Adler S, Ward HD. Cryptosporidiosis: environmental, therapeutic, and preventive challenges. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:927–35. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0960-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wanyiri J, Ward H. Molecular basis of Cryptosporidium-host cell interactions: recent advances and future prospects. Future Microbiol. 2006;1:201–8. doi: 10.2217/17460913.1.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrahamsen MS, Templeton TJ, Enomoto S, Abrahante JE, Zhu G, Lancto CA, et al. Complete genome sequence of the apicomplexan, Cryptosporidium parvum. Science. 2004;304:441–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1094786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu P, Widmer G, Wang Y, Ozaki LS, Alves JM, Serrano MG, et al. The genome of Cryptosporidium hominis. Nature. 2004;431:1107–12. doi: 10.1038/nature02977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cevallos AM, Bhat N, Verdon R, Hamer DH, Stein B, Tzipori S, et al. Mediation of Cryptosporidium parvum infection in vitro by mucin-like glycoproteins defined by a neutralizing monoclonal antibody. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5167–75. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5167-5175.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gut J, Nelson RG. Cryptosporidium parvum: lectins mediate irreversible inhibition of sporozoite infectivity in vitro. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1999;46:48S–9S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett EP, Mandel U, Clausen H, Gerken TA, Fritz TA, Tabak LA. Control of mucin-type O-glycosylation: a classification of the polypeptide GalNAc-transferase gene family. Glycobiology. 2012;22:736–56. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ten Hagen KG, Fritz TA, Tabak LA. All in the family: the UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases. Glycobiology. 2003;13:1R–6R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stwora-Wojczyk MM, Kissinger JC, Spitalnik SL, Wojczyk BS. O-glycosylation in Toxoplasma gondii: identification and analysis of a family of UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases. Int J Parasitol. 2004;34:309–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wojczyk BS, Stwora-Wojczyk MM, Hagen FK, Striepen B, Hang HC, Bertozzi CR, et al. cDNA cloning and expression of UDP-N-acetyl-d-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase T1 from Toxo-plasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;131:93–107. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(03)00196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stwora-Wojczyk MM, Dzierszinski F, Roos DS, Spitalnik SL, Wojczyk BS. Functional characterization of a novel Toxoplasma gondii glycosyltransferase: UDP-N-acetyl-d-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl-transferase-T3. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;426:231–40. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heiges M, Wang H, Robinson E, Aurrecoechea C, Gao X, Kaluskar N, et al. CryptoDB: a Cryptosporidium bioinformatics resource update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D419–22. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aurrecoechea C, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Fischer S, Gajria B, Gao X, et al. EuPathDB: a portal to eukaryotic pathogen databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D415–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo Q, Upadhya R, Zhang H, Madrid-Aliste C, Nieves E, Kim K, et al. Analysis of the glycoproteome of Toxoplasma gondii using lectin affinity chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:1199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belli SI, Lee M, Thebo P, Wallach MG, Schwartsburd B, Smith NC. Biochemical characterisation of the 56 and 82 kDa immunodominant gametocyte antigens from Eimeria maxima. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:805–16. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mauzy MJ, Enomoto S, Lancto CA, Abrahamsen MS, Rutherford MS. The Cryptosporidium parvum transcriptome during in vitro development. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, Guo F, Zhou H, Zhu G. Transcriptome analysis reveals unique metabolic features in the Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts associated with environmental survival and stresses. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:647. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zinecker CF, Striepen B, Tomavo S, Dubremetz JF, Schwarz RT. The dense granule antigen, GRA2 of Toxoplasma gondii is a glycoprotein containing O-linked oligosaccharides. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;97:241–6. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hang HC, Yu C, Ten Hagen KG, Tian E, Winans KA, Tabak LA, et al. Small molecule inhibitors of mucin-type O-linked glycosylation from a uridine-based library. Chem Biol. 2004;11:337–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhat N, Joe A, Pereiraperrin M, Ward HD. Cryptosporidium p30, a galactose/N-acetylgalactosamine-specific lectin, mediates infection in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.