Although loss of CP110 is tolerated in Drosophila, CP110 is important for limiting centriole length, limiting centriolar microtubule length, and suppressing centriole overduplication when duplication proteins are overexpressed.

Abstract

CP110 is a conserved centriole protein implicated in the regulation of cell division, centriole duplication, and centriole length and in the suppression of ciliogenesis. Surprisingly, we report that mutant flies lacking CP110 (CP110Δ) were viable and fertile and had no obvious defects in cell division, centriole duplication, or cilia formation. We show that CP110 has at least three functions in flies. First, it subtly influences centriole length by counteracting the centriole-elongating activity of several centriole duplication proteins. Specifically, we report that centrioles are ∼10% longer than normal in CP110Δ mutants and ∼20% shorter when CP110 is overexpressed. Second, CP110 ensures that the centriolar microtubules do not extend beyond the distal end of the centriole, as some centriolar microtubules can be more than 50 times longer than the centriole in the absence of CP110. Finally, and unexpectedly, CP110 suppresses centriole overduplication induced by the overexpression of centriole duplication proteins. These studies identify novel and surprising functions for CP110 in vivo in flies.

Introduction

Centrioles are complex microtubule (MT)-based structures that guide the formation of two cell organelles—the centrosome and the cilium. These organelles play an important part in various cell processes, and their dysfunction is linked to many human pathologies, including cancer, microcephaly, polycystic kidney disease, and obesity (Nigg and Raff, 2009; Bettencourt-Dias et al., 2011).

CP110 is a conserved centriolar protein (Hodges et al., 2010; Carvalho-Santos et al., 2012) that was first identified as a Cdk substrate essential for centriole duplication (Chen et al., 2002). Subsequently, CP110 has been implicated in mitotic spindle assembly, cytokinesis, and the maintenance of genome stability (Tsang et al., 2006; D’Angiolella et al., 2010). In tissue culture cells, CP110 levels are tightly regulated during the cell cycle. CP110 is a major target of the SCFCyclin F ubiquitin ligase, and perturbing CP110 degradation leads to centrosome and spindle abnormalities and defects in chromosome segregation (D’Angiolella et al., 2010); the USP33 de-ubiquitinase appears to be essential for counteracting the activity of SCF in promoting CP110 destruction (Li et al., 2013).

CP110 is concentrated at the distal end of centrioles (Kleylein-Sohn et al., 2007; Fu and Glover, 2012; Sonnen et al., 2012), where it is required to suppress cilia formation (Spektor et al., 2007). When CP110, or its binding partner Cep97, are depleted from RPE-1 cells, the cells spontaneously form cilia when they would not normally do so, whereas overexpression of CP110 suppresses normal cilia formation. These findings suggest that CP110 normally suppresses cilia formation and that its removal from the distal end of centrioles is a prerequisite for cilia formation. In agreement with this, the conserved micro-RNA miR-129-3p regulates cilia biogenesis in cultured cells, at least in part, by down-regulating CP110 (Cao et al., 2012), while Tau tubulin kinase 2 (TTBK2) initiates cilia formation, at least in part, by promoting the removal of CP110 from centrioles (Goetz et al., 2012).

Recently, however, several groups reported that the depletion of CP110 in certain cultured mammalian cells does not lead to the ectopic formation of cilia, but rather to a dramatic elongation of the centrioles (Kohlmaier et al., 2009; Schmidt et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009). This effect was similar to that seen when the centriole duplication protein CPAP/SAS-4 was overexpressed, suggesting that CP110 might antagonize the ability of CPAP/SAS-4 to promote centriole elongation. A possible explanation for the different results in different cell types is that CP110 suppresses ciliogenesis in cells that have the ability to form cilia (such as RPE-1 cells) and suppresses centriole elongation in cells that do not form cilia (such as U2OS cells).

In human cells that can form cilia, CP110 has been shown to interact with the MT-depolymerizing kinesin Kif24C, and this kinesin can specifically remodel centriolar, but not cytoplasmic, MTs (Kobayashi et al., 2011). An interaction between CP110 and the MT-depolymerizing kinesin Klp10A was also reported in Drosophila S2 cells in culture (Delgehyr et al., 2012). Surprisingly, however, the depletion of CP110 in these cells leads to a shortening of the centrioles, suggesting that the loss of CP110 may have different consequences depending on the species and/or cell type.

Taken together, these observations suggest that CP110 has an important role in controlling the behavior of centrioles, centrosomes, and cilia; several mechanisms ensure the tight regulation of CP110 levels in cells, and there are severe consequences for the cell if this regulation is perturbed. A potential caveat to these studies, however, is that they were performed in cultured cells. Here, we have generated a CP110-null mutation in Drosophila, allowing us, for the first time, to analyze cell behavior in the absence of this protein in vivo.

Results

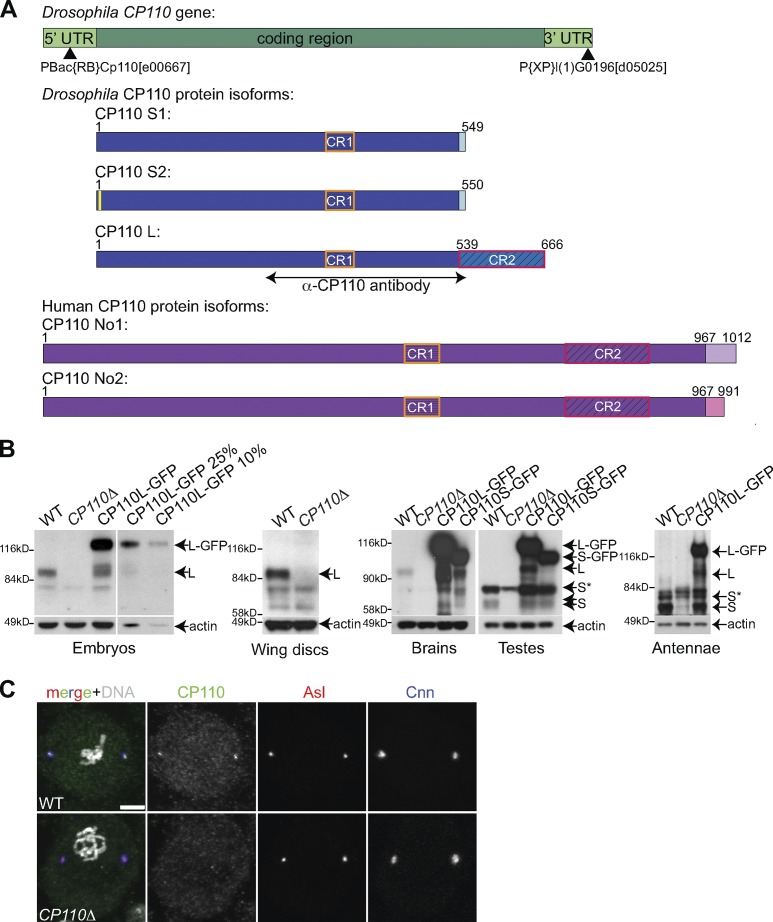

There are two isoforms of Drosophila CP110 that are differentially expressed

There are three annotated splice variants of Drosophila CP110—a long form (CP110L) and two short forms; as the short forms differ in only two amino acids, we will collectively refer to them as CP110S (Fig. 1 A). Both the long and short forms share a short region of 44 aa, which is ∼30% identical to a region in human CP110 (hereafter referred to as conserved region 1, or CR1). The long form has an additional conserved region (CR2) of 127 aa, which is ∼32% identical to a second region in human CP110. We raised and affinity-purified antibodies that would recognize both the long and short forms (Fig. 1 A), and we generated transgenic fly lines expressing GFP fusions of either form under the control of the ubiquitin promoter that is expressed at moderate levels in all tissues. In Western blotting experiments, the affinity-purified antibodies recognized both forms of the endogenous protein, as well as their respective GFP fusions, which were overexpressed by approximately five- to tenfold compared with the endogenous proteins (Fig. 1 B). In embryos, larval wing discs, and larval brains (which all lack cilia or flagella), only the long form of the endogenous protein was detected (Fig. 1 B), whereas in pupal testes and pupal antennae (which contain many ciliated/flagellated cells), only the short form was detected (Fig. 1 B), suggesting that there might be functional differences between the two isoforms.

Figure 1.

Characterization of Drosophila CP110 and generation of a CP110 null mutant. (A) A schematic representation of the Drosophila CP110 gene (green), its three protein isoforms (blue—note that CP110S1 and CP110S2 differ by only 2aa’s—yellow box), and the two annotated human CP110 isoforms (purple). The region of CP110 used for antibody production is highlighted, and the positions of the P-elements, used to generate the CP110Δ deletion, are indicated by black arrowheads (see Fig. S1 for more detail). The two conserved regions are boxed (CR1, orange boxes; CR2, red boxes). (B) Panels show Western blots of Drosophila syncytial embryos, third instar larval wing discs or brains, or pupal testes or antennae from WT, CP110Δ, or either Ubq-CP110L-GFP– or Ubq-CP110S-GFP–expressing lines probed with α-CP110 antibody or α-actin antibody (loading control). Endogenous CP110L (L) is expressed in embryos, wing disc, and brain cells and is missing in CP110Δ tissues. Endogenous CP110S (S) is expressed in testes and antennae and is also missing in the CP110Δ tissue, although this is partially obscured by a co-migrating background band (S*). A serial dilution of the embryo extract overexpressing CP110L-GFP is shown to illustrate how we estimated levels of overexpression. (C) Neuroblasts from WT and CP110Δ third instar larvae were stained for CP110 (green), Asl (red), Cnn (blue), and DNA (Hoechst; white in merge). Bars, 5 µm.

Drosophila CP110 is not essential for centriole duplication or cell cycle progression

To assess the function of Drosophila CP110, we generated a deletion of the entire CP110 coding region using FLP-induced recombination between two P-element insertions in the CP110 gene (Fig. 1 A; Fig. S1 A). We recovered several independent lines, and PCR analysis confirmed that the CP110 coding region was deleted in all of them (Fig. S1, A and B—hereafter CP110Δ lines). CP110 protein was undetectable by Western blotting (Fig. 1 B) or immunofluorescence (Fig. 1 C), confirming the specificity of the antibodies and that CP110Δ flies lacked detectable CP110. To our surprise, CP110Δ flies were viable and fertile, and we have maintained a number of lines as laboratory stocks for several years.

We quantified centriole numbers and the level of PCM recruitment in CP110Δ larval brain cells. We found no significant difference in these parameters between wild-type (WT) and CP110Δ cells, and we noticed no obvious mitotic defects in these cells (Fig. S1, C and D). We also examined centrosome and spindle behavior in living CP110Δ syncytial embryos: even in these rapidly cycling embryos, we found no obvious defects in centrosome behavior, spindle formation, progression through the cell cycle, or chromosome segregation (a total of >400 centriole duplication and mitotic spindle assembly/disassembly events were observed from 9 different embryos; Fig. S1, E and F; unpublished data).

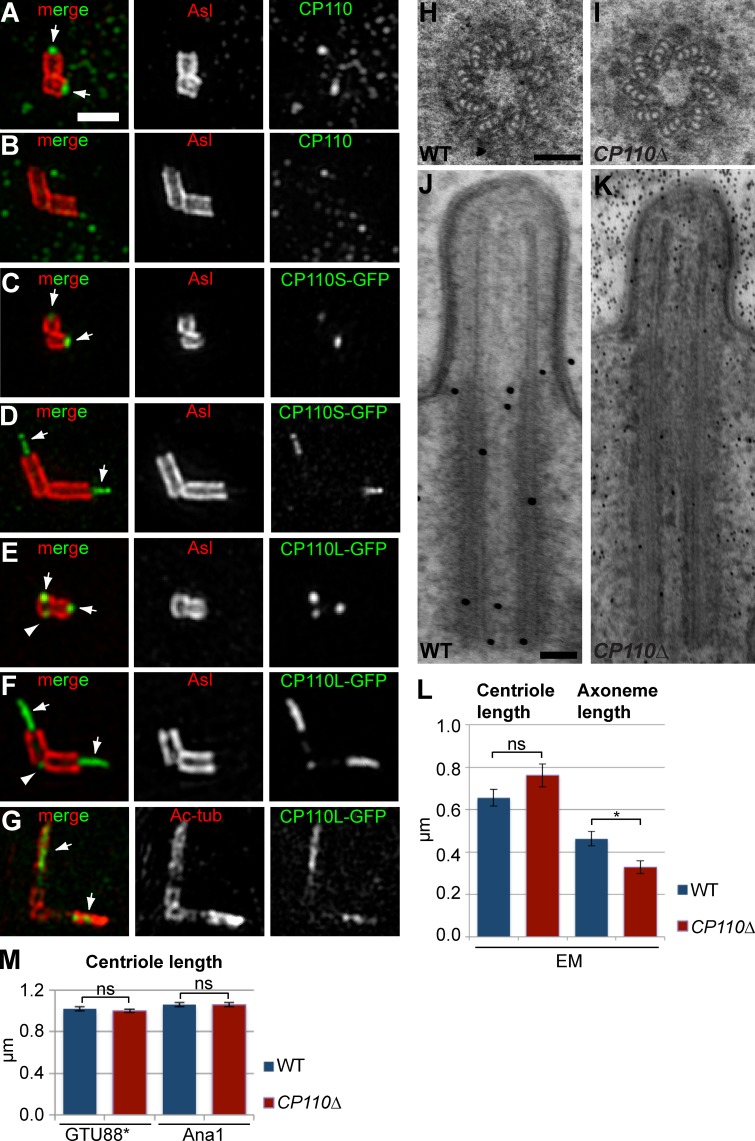

Neither lack of CP110 nor CP110-GFP overexpression dramatically interferes with centriole behavior or cilia/flagella formation in spermatocytes

We compared centriole behavior in WT and CP110Δ spermatocytes. In WT spermatocytes, centrioles normally elongate extensively over several days, initially forming short cilia and ultimately going on to form the sperm flagellum after meiosis is completed (González et al., 1998). In the youngest WT spermatocytes examined by 3D-structured illumination microscopy (3D-SIM), the endogenous CP110 localized to a small dot at the distal end of the mother and daughter centrioles, lying just inside the outer centriole wall (stained by anti-Asl antibodies; Fig. 2 A). As the centrioles started to elongate, CP110 was no longer detectable at the distal ends (Fig. 2 B), consistent with previous reports that CP110 is normally removed from centrioles that form cilia (Spektor et al., 2007; Tsang et al., 2009).

Figure 2.

An analysis of centriole and cilia behavior in WT and CP110Δ primary spermatocytes. (A–G) 3D-SIM images of centrioles in primary spermatocytes stained for endogenous CP110 (A and B) or overexpressed CP110-GFP (C–G, green) and either Asl (A–F) or acetylated tubulin (G, red). (A and B) CP110 is detectable at the distal tips of the short centrioles in very young WT spermatocytes (A, arrows) but is no longer detectable once the centrioles start to elongate in G2 (B). (C–G) Both overexpressed CP110S-GFP (C and D) and CP110L-GFP (E–G) are detected at the distal ends of young centrioles (C and E, arrows), and on fibers that extend from the distal tip of the elongating centrioles (D and F, arrows). CP110-GFP is also sometimes detectable at the proximal end of mother centrioles (E and F, arrowheads). The CP110-GFP fiber appears to be located within the centriolar MTs stained with acetylated tubulin antibodies (G). (H–K) Panels show EM images of centrioles (H and I) and cilia (J and K) in WT (H and J) and CP110Δ (I and K) primary spermatocytes. The centriole appears slightly elongated and the axoneme slightly shortened in the CP110Δ cilium (K). (L) Quantification of centriole and axoneme length by EM in 7 WT (blue) and 5 CP110Δ (red) cilia confirmed this trend, although the difference in centriole length was not statistically significant (perhaps due to the small numbers analyzed). (M) A statistically more robust quantification of centriole length in WT (blue) and CP110Δ (red) mature primary spermatocytes (measured by immunofluorescence with the centriole markers GTU88* and Ana1) revealed no significant difference in centriole length. Total number of centrioles analyzed; total number of spermatocyte cysts analyzed are: 1504;52, 1029;39, 1624;52, and 1090;43, respectively (order as shown in graph). In this and all subsequent bar charts error bars denote SEM and significance testing was conducted using the Mann-Whitney test. P > 0.05 (ns); *, P = 0.01–0.05; **, P = 0.001–0.01; ***, P = 0.0001–0.001; and ****, P < 0.0001. Note that an average centriole length for each spermatocyte cyst was calculated and the number of spermatocyte cysts analyzed was then used as the sample number for statistical analysis. Bars: (A–G) 1 µm; (H–K) 100 nm.

In CP110Δ primary spermatocytes, by contrast, CP110 was not detectable at the tip of the centrioles in the youngest cells (unpublished data), but these centrioles were indistinguishable from those in young WT spermatocytes, and we could detect no evidence of centriole defects (Fig. 2, H and I) or of premature cilia formation (unpublished data) by EM. Interestingly, our EM analysis of cilia in older spermatocytes suggested that the centrioles may be slightly elongated and the axonemes slightly shortened in the absence of CP110 (Fig. 2, J–L), but our numbers were small (only 7 and 5 cilia were in a favorable orientation allowing us to accurately measure centriole and axoneme length in WT and CP110Δ spermatocytes, respectively), so we remain cautious in our conclusions from these data. Indeed, a more robust statistical analysis of centriole length by immunofluorescence with anti-centriole antibodies revealed no dramatic difference in centriole length in mature primary spermatocytes (Fig. 2 M).

There were, however, occasional defects in the ultrastructure of the elongating spermatid axoneme—∼4% of axonemes had one or more MT doublets missing (n > 400) compared with 0% in WT (n > 400; Fig. S2, A–D). The centrioles in CP110Δ spermatocytes also had a slight, but significant, tendency to separate prematurely (often leading to centriole mis-segregation during meiosis; Fig. S2, E, F, and H); this defect was rescued by the transgenic expression of CP110S-GFP (Fig. S2, G and H). Taken together, these data indicate that centriole/cilia behavior is not dramatically perturbed, but is also not completely normal, in spermatocytes that lack CP110.

We also examined centriole and cilia/flagella behavior in testes overexpressing either CP110L-GFP or CP110S-GFP. Like the endogenous CP110, both fusion proteins were detectable at the distal end of mother and daughter centrioles in young spermatocytes (Fig. 2, C and E), but, in addition, both fusion proteins could occasionally also be detected at the proximal end of the mother centriole (Fig. 2 E, arrowhead). This suggests that CP110 can associate with the centriole proximal end, but it has a higher affinity for the distal end. As the spermatocytes matured, both GFP fusion proteins remained concentrated at the distal ends of the elongating centrioles, forming an extended fiber (Fig. 2, D and F; arrows), and they were still occasionally detectable at the proximal end of the mother (Fig. 2 F, arrowhead). The distal fiber of CP110 staining appeared to lie within the ciliary axoneme revealed with anti-acetylated tubulin antibodies (Fig. 2 G), suggesting that it is probably part of the “central tube” that runs through the center of the axoneme (Carvalho-Santos et al., 2012; Roque et al., 2012).

We confirmed that apparently normal centrioles, cilia, and flagella were present in flies overexpressing either CP110L-GFP or CP110S-GFP (unpublished data), and these flies were viable, fertile, and were not noticeably uncoordinated (indicating that functional cilia were present in the ciliated sensory neurons). Thus, the overexpression of CP110L-GFP or CP110S-GFP, at least to the levels we have achieved here (approximately five- to tenfold; Fig. 1 B), does not detectably interfere with centriole elongation or cilia/flagella formation in spermatocytes, even though some CP110 remains associated with the distal region of the centrioles under these conditions.

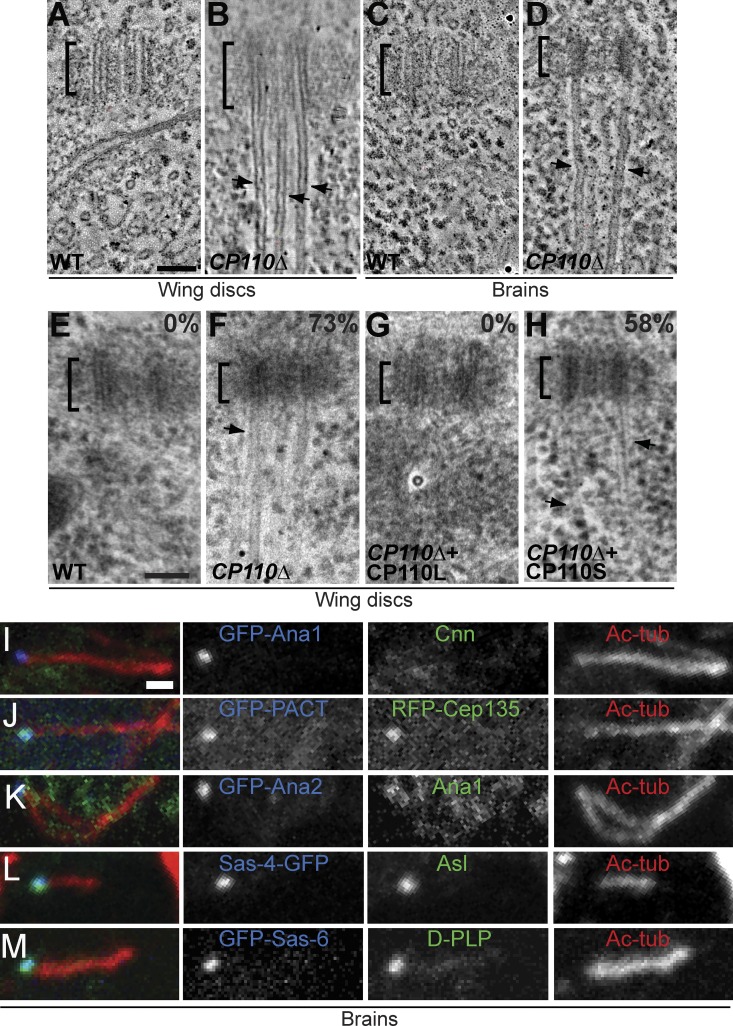

Centriolar MTs are dramatically elongated in somatic cells that lack CP110

As the centrioles in spermatocytes are unusually elongated in flies, we used electron tomography (ET) and EM to examine the centrioles in larval wing disc cells, which contain more “typical” centrioles that do not form cilia. Remarkably, we found that the majority of CP110Δ centrioles in these cells (>70%; n = 163) had extensive MT protrusions emanating from their distal ends (Fig. 3, A, B, E, and F, arrowheads; Video 1). The protrusions were often many times longer than the centrioles themselves—the longest being >5 µm in length, which is ∼50× longer than the centriole. The MT protrusions were not unique to wing disc centrioles, as we also observed them by ET in larval brain cells (Fig. 3, C and D) and in cultured S2 cells that had been depleted of CP110 by RNAi (Fig. S3, A–D; Video 2).

Figure 3.

Centriolar MTs are dramatically elongated in somatic cells that lack CP110. (A–D) Panels show projections of an EM tomogram of a centriole in a WT (A and C) and a CP110Δ (B and D) larval wing disc cell (A and B) or brain cell (C and D). The centriolar MTs extend dramatically (arrows) beyond the centriole (brackets) in CP110Δ cells (see Video 1 for representative tomograms). (E–H) Quantification of the centriolar MT extensions in WT (E), CP110Δ (F), CP110Δ rescued by CP110L-GFP (G), and CP110Δ rescued by CP110S-GFP (H) wing disc cells. Panels show representative EM images, and the percentage of centrioles with clearly elongated centriolar MTs is indicated. n (total centrioles; total wing discs): 134;9 (E), 127;9 (F), 45;4 (G), and 53;3 (H). (I–M) Centrioles in third instar larval brains from CP110Δ flies expressing various centriolar-GFP markers (as indicated) were stained for GFP (blue), for acetylated tubulin (red, to reveal the centriolar MT extensions), and various other centriolar proteins (green, as indicated). Bars: (A–H) 100 nm; (I–M) 1 µm.

The protrusions were not extensions of the entire centriole structure, as there was a clear demarcation between them and the more electron-dense centrioles (highlighted by brackets in Fig. 3, A–F). Moreover, the vast majority of protrusions (86%, n = 28) were composed of singlet MTs (Fig. 3, B and D; Fig. S3 F; Video 1 and Video 3) rather than the doublets (14%, n = 28) found in most fly centrioles and cilia. The protrusions were also labeled by anti-acetylated tubulin antibodies, but not by antibodies raised against several other centriolar components (Asl, Ana1, GFP-Ana2, DSas-4-GFP, GFP-DSas-6, RFP-Cep135, D-PLP, and GFP-PACT; Fig. 3, I–M). We conclude that the protrusions are abnormally extended centriolar MTs rather than elongated centrioles. Importantly, the formation of protrusions was efficiently suppressed by CP110L-GFP but not by CP110S-GFP (Fig. 3, F–H), even though both fusion proteins were overexpressed at similar levels in all tissues (Fig. 1 B; unpublished data), demonstrating a clear functional difference between the two CP110 isoforms.

CP110 levels subtly influence centriole length

To test whether the lack of CP110 also affected centriole length, we measured this in WT, mutant, and rescued mutant wing discs by EM. We examined 3–9 individual wing discs for each genotype and measured, in each disc, 7–21 centrioles that were in a favorable orientation. We measured only the length of the “core” electron-dense centriole, excluding any MT protrusions (Fig. 4, A–D and N). The centrioles in CP110Δ wing discs were slightly (∼10%) but significantly longer than those in a WT control, and this phenotype was rescued by the expression of CP110L-GFP and more weakly by the expression of CP110S-GFP (Fig. 4, A–D and N). We did not notice a dramatic difference in centriole length in S2 cells depleted of CP110 by RNAi, but our number of experimental replicates was very small (Fig. S3 E).

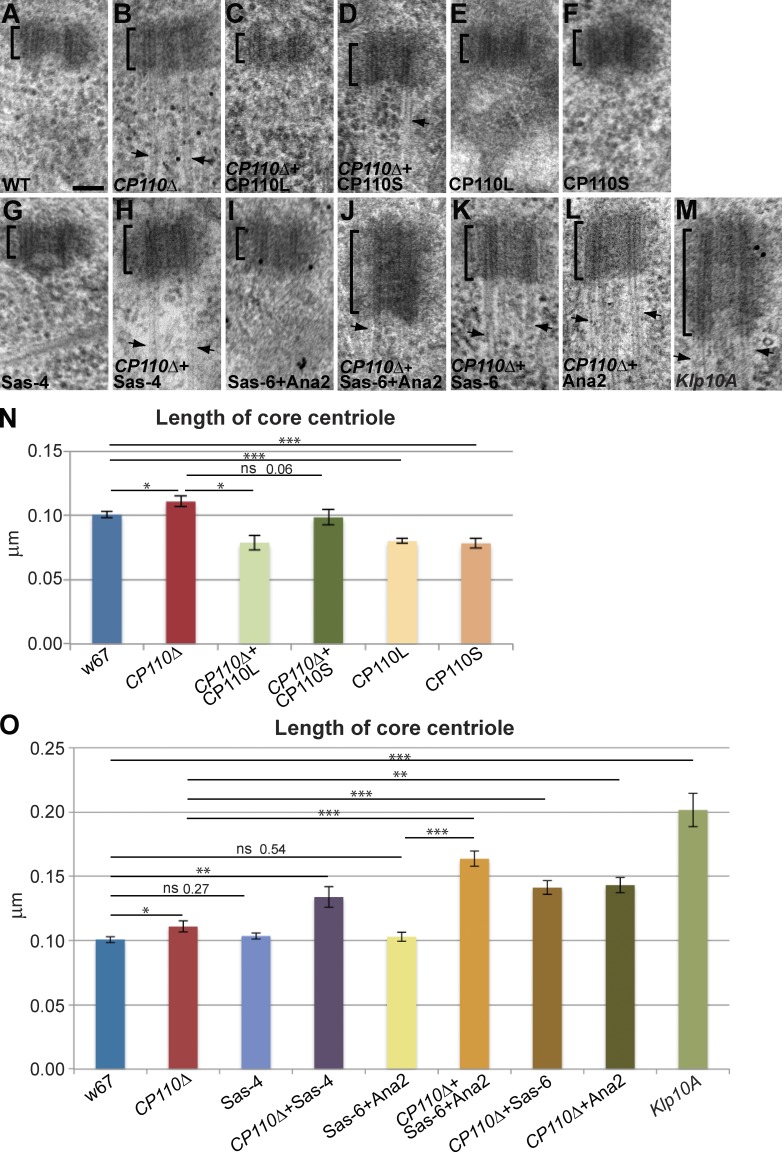

Figure 4.

Cellular CP110 levels influence centriole length. (A–M) Panels show representative EM images of centrioles in larval wing disc cells of various genotypes (as indicated on each panel); n (total centrioles; total wing discs): 134;9 (A), 127;9 (B), 45;4 (C), 53;3 (D), 61;5 (E), 75;5 (F), 109;9 (G), 48;3 (H), 98;8 (I), 87;7 (J), 75;5 (K), 42;4 (L), and 93;7 (M). Arrows highlight MT extensions. (N and O) Bar charts show the quantification of centriole length in these genotypes. Note that the overexpression of CP110S-GFP dramatically shortens centrioles in a WT background, but has a less marked effect in the CP110Δ background (only bordering on the statistically significant). We suspect that this might be because MT extensions are still present in CP110Δ cells overexpressing CP110S-GFP, potentially contributing to the slight lengthening of the centriole. Bar, 100 nm.

Strikingly, the centrioles in WT wing disc cells that overexpressed CP110L-GFP or CP110S-GFP (Fig. 4, E, F, and N) were significantly shorter (∼20%) than those in WT discs. Thus, the lack CP110 or the overexpression of either isoform of CP110 subtly alters centriole length in wing disc cells, indicating that CP110 normally plays an important, but relatively minor, part in regulating centriole length in these fly cells in vivo. The finding that only CP110L can prevent the overgrowth of the centriolar MTs (Fig. 3, F–H), whereas the overexpression of either isoform can reduce centriole length (Fig. 4 N) suggests that CP110 must “cap” centriolar MTs and influence centriole length by distinct mechanisms: both isoforms can perform the latter function but only CP110L can perform the former function.

CP110 counters the ability of several core centriole duplication proteins to promote centriole elongation

In vertebrate cells, CP110 seems to suppress centriole elongation by opposing the activity of CPAP/SAS-4 (Kohlmaier et al., 2009; Schmidt et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009). Surprisingly, however, the overexpression of Drosophila SAS-4 (DSas-4) by approximately fivefold in WT wing disc cells (Fig. S4) did not increase centriole length (Fig. 4 O); moreover, it did not produce detectable centriolar MT protrusions (Fig. 4 G). In the absence of CP110, however, DSas-4 overexpression led to an increase in centriole length that was more dramatic (∼30%) than that seen in CP110Δ cells alone (∼10%; Fig. 4, H and O). Because the MT protrusions in CP110Δ cells were so long and affected so many centrioles, we were unable to assess whether overexpression of DSas-4 influenced this aspect of the CP110Δ phenotype.

We tested whether overexpression of other core centriole duplication proteins could drive centriole elongation in the absence of CP110. The co-overexpression of the centriolar central cartwheel components GFP-DSas-6 and GFP-Ana2 has previously been shown to induce the formation of very long SAS tubules that resemble the centriole inner cartwheel in structure (Stevens et al., 2010a). The co-overexpression of these proteins did not, however, perturb centriole length in WT wing disc cells; in contrast, it dramatically increased centriole length (by >60%) in CP110Δ cells (Fig. 4, I, J, and O). Overexpression of either GFP-DSas-6 or GFP-Ana2 on their own in CP110Δ cells had a similar, but less dramatic, effect (Fig. 4, K, L, and O). We conclude that CP110 can prevent the centriole elongation induced by the overexpression of several core centriole duplication proteins.

CP110 helps prevent centriole overduplication induced by the overexpression of core centriole duplication proteins

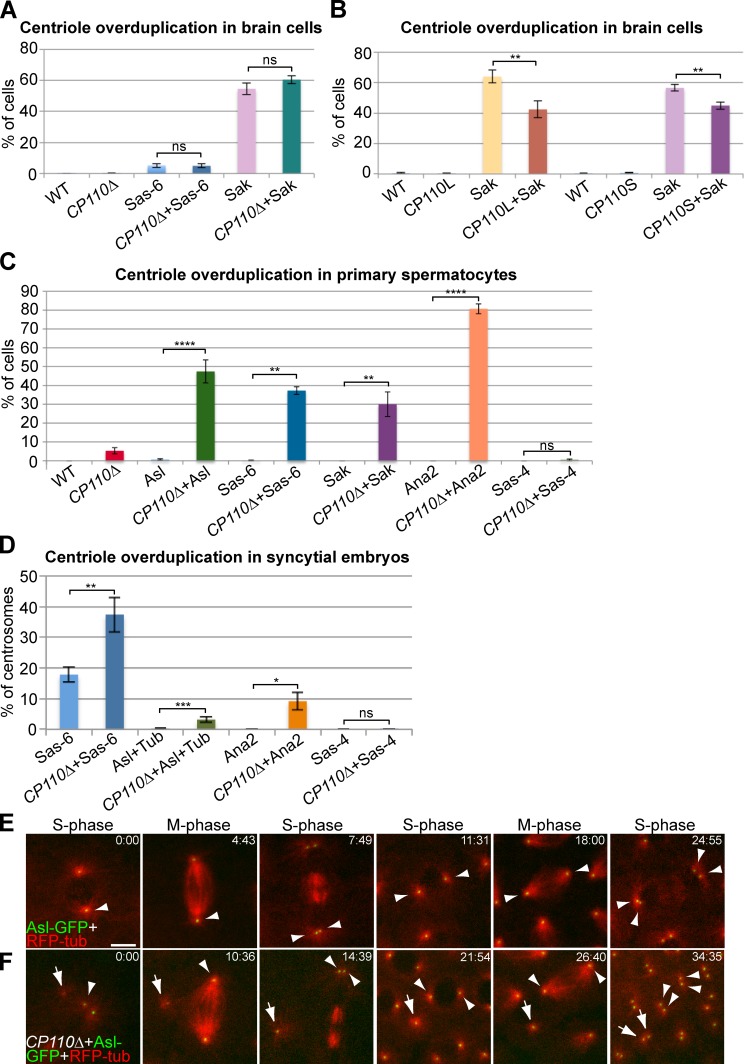

It has previously been shown that CP110 is required for the centriole overduplication that can be induced in some cultured vertebrate cells either by hydroxyurea arrest (Chen et al., 2002) or by Plk4 overexpression (Kleylein-Sohn et al., 2007). In flies, the overexpression of centriole duplication proteins can induce centriole overduplication to different extents in different tissues (Peel et al., 2007; Stevens et al., 2010b). We wanted to test whether CP110 was essential for centriole overduplication in flies. In larval brain cells the overexpression of Sak or DSas-6 leads to high or low levels of centriole overduplication, respectively (Peel et al., 2007; Basto et al., 2008). In contrast to the situation in vertebrate cells, the level of overduplication was not detectably changed in the absence of CP110 (Fig. 5 A). Surprisingly, we noticed that the overexpression of either CP110L-GFP or CP110S-GFP could significantly reduce the centriole overduplication driven by Sak (Fig. 5 B).

Figure 5.

CP110 can suppress centriole overduplication driven by the overexpression of centriole duplication proteins. (A) Quantification of centriole overduplication (percentage of prometaphase cells with >2 Asl-positive centrosomes) in WT and CP110Δ third instar larval brains overexpressing GFP-DSas-6 or GFP-Sak; n (total cells; total brains): 482;15, 742;14, 575;9, 695;12, 472;10, and 695;13, respectively (order as shown in graph). (B) Quantification of centriole overduplication in WT, CP110L-GFP–, or CP110S-GFP–overexpressing third instar larval brain cells with or without GFP-Sak overexpression; n (total cells; total brains): 509;9, 333;6, 374;7, 772;9, 605;11, 527;9, 1440;28, and 1888;29, respectively (order as shown in graph). (C) Quantification of centriole overduplication (percentage of cells with >4 Asl-positive centrioles) in WT and CP110Δ primary spermatocytes overexpressing the centriole duplication proteins Asl-GFP, GFP-DSas-6, GFP-Sak, GFP-Ana2, and DSas-4-GFP (as indicated); n (total cells; total testes): 317;16, 325;16, 534;22, 244;17, 250;6, 500;7, 304;5, 318;11, 506;10, 626;15, 456;11, and 161;5, respectively (order as shown in graph). Note that the apparent overduplication of centrioles in CP110Δ cells is almost certainly due to centriole mis-segregation caused by the premature separation of the centrioles, as we observed an almost equal number of cells with too few centrioles. (D) Quantification of centriole overduplication (percentage of centriole duplication events in which one centrosome divided to form more than two centrosomes) in WT or CP110Δ syncytial embryos expressing either Asl-GFP+RFP-tubulin, GFP-DSas-6, GFP-Ana2, or DSas-4-GFP; n (total centriole duplication events; total centriole duplication cycles): 669;36, 1105;49, 1298;43, 509;23, 311;7, 361;12, 301;5, and 422;13, respectively (order as shown in graph). (E and F) Panels show stills from movies of WT (E) and CP110Δ (F) syncytial embryos expressing Asl-GFP and RFP-tubulin. Time (min:sec) is shown in top right corners. Note how a very small Asl-GFP dot that can organize MTs (arrow) is present in the CP110Δ embryo close to the two centrioles that have just divided (arrowhead; t = 0:00). This dot increases in brightness over time, but does not initially divide when the other centrioles in the embryo divide (t = 14:39). This dot does divide, however, during the next round of division (t = 34:35). Note that an average percentage of centriole overduplication was calculated for each brain (A and B), each testes (C), or embryo (D), and the number of brains, testes, or centriole duplication cycles was then used as the sample number for statistical analysis. Bar: (E and F) 5 µm.

To investigate further whether CP110 might act to suppress centriole overduplication we turned to spermatocytes. The overexpression of Asl-GFP, GFP-DSas-6, GFP-Sak, GFP-Ana2, or DSas-4-GFP did not cause centriole overduplication in WT spermatocytes, but, remarkably, all of them (apart from DSas-4-GFP) could drive centriole overduplication in the absence of CP110: Ana2 overexpression lead predominantly to the formation of rosette-like structures; Asl and Sak overexpression lead predominantly to the formation of detached extra centrioles; DSas-6 overexpression lead to the formation of both types of extra centrioles (Fig. 5 C; Fig. S5). Importantly, Western blotting experiments revealed that the total cellular levels of Asl, DSas-4, and DSas-6 were generally not altered in tissues that lacked CP110 (unpublished data); unfortunately, we were unable to reliably detect endogenous Ana2 or Sak by Western blotting.

In WT syncytial embryos, overexpression of GFP-DSas-6 caused ∼18% of centrioles to overduplicate, and in CP110Δ embryos this increased to ∼37% (Fig. 5 D). Moreover, although overexpression of Asl-GFP or GFP-Ana2 did not induce centriole overduplication in WT embryos, they both did so in CP110Δ embryos (Fig. 5 D). As in spermatocytes, overexpression of DSas-4-GFP did not drive centriole overduplication, even in the absence of CP110 (Fig. 5 D). The extra centrioles observed in these embryos were often first visible as very dim dots that organized MTs (Fig. 5 F, arrow), but they increased in brightness over time, and often ultimately duplicated (Fig. 5 F, arrows) in synchrony with the other centrioles (Fig. 5 F, arrowheads), strongly suggesting that they were bona fide centrioles. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that CP110 is not required for centriole overduplication, but rather it actively functions to suppress centriole overduplication when certain centriole duplication proteins are overexpressed.

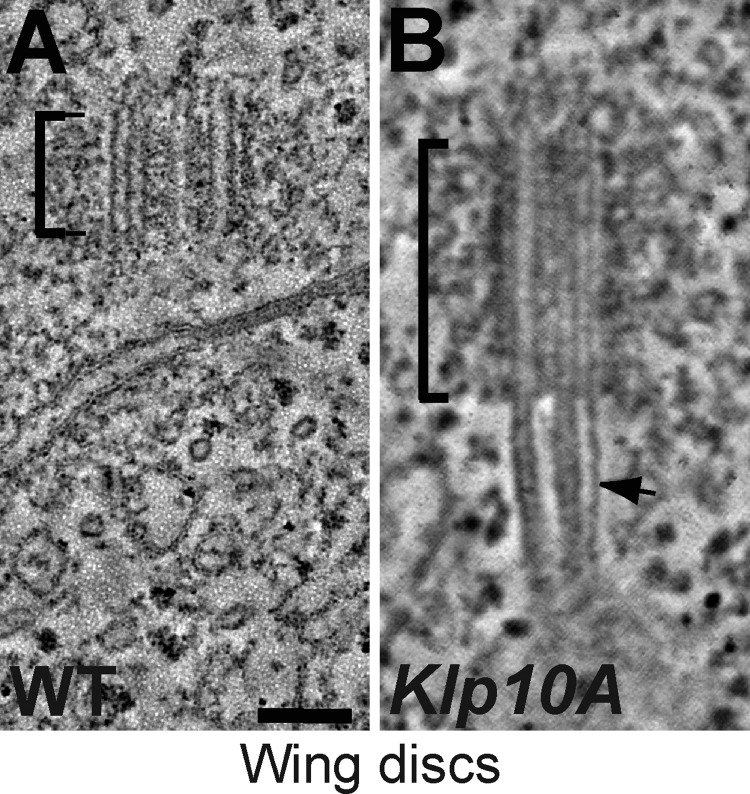

Klp10A mutant cells have elongated centrioles and dramatic centriolar MT protrusions

The MT-depolymerizing kinesins Kif24c and Klp10A interact with CP110 in human and fly cells, respectively (Kobayashi et al., 2011; Delgehyr et al., 2012). We therefore tested whether perturbing Klp10A function in wing disc cells had a similar effect on centrioles as the lack of CP110. As reported previously in spermatocytes and cultured S2 cells (Delgehyr et al., 2012), Klp10A mutant wing discs cells had dramatically elongated centrioles (∼100% longer than WT; Fig. 4, M and O; Fig. 6). In addition, the centrioles had long MT protrusions extending from their distal ends (Fig. 4 M; Fig. 6). As in CP110Δ cells, these protrusions were often many times longer than the centrioles themselves, but, in contrast to those in CP110Δ cells, the majority of these protrusions (∼74%, n = 23) were MT doublets rather than singlets (∼26%, n = 23; Fig. S3, F and G; Video 4). These results raise the possibility that Klp10A might cooperate with CP110 to regulate both centriole length and the length of the centriolar MTs, but they also indicate that Klp10A has some CP110-independent function in these regulatory processes, as both centriole abnormalities appear to be more severe in the Klp10A mutants than in the cells lacking CP110.

Figure 6.

Centrioles and centriolar MTs are elongated in Klp10A mutant wing disc cells. (A and B) Panels show projections of an EM tomogram of a centriole in a WT (A) and a Klp10A mutant (B) larval wing disc cell (note that the WT control shown here is the same as the one shown in Fig. 3 A). In Klp10A mutant cells the centriole is elongated and the centriolar MTs extend dramatically (arrow; normally as doublets) beyond the centriole (brackets; see Video 4). The quantitation of centriole length in Klp10A mutant cells is shown in Fig. 4 O; n (total centrioles/total wing discs) 93:7. Bar, 100 nm.

Discussion

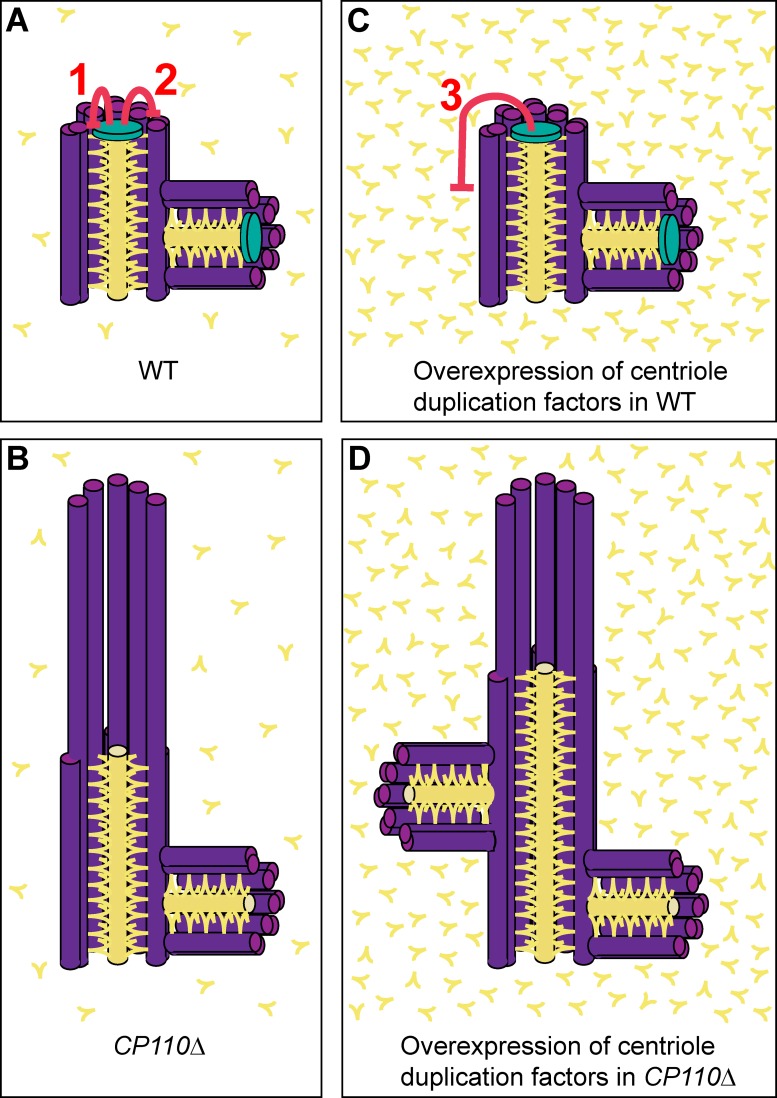

Previous studies in cultured cells have indicated that CP110 has important functions in promoting centriole duplication, cell cycle progression, cell division, regulating centriole length, and inhibiting cilia formation (Chen et al., 2002; Tsang et al., 2006, 2008; Kleylein-Sohn et al., 2007; Spektor et al., 2007; Kohlmaier et al., 2009; Schmidt et al., 2009; D’Angiolella et al., 2010; Li et al., 2013). Multiple mechanisms ensure that CP110 protein levels are tightly regulated in cells (D’Angiolella et al., 2010; Li et al., 2013). It is very surprising, therefore, that flies completely lacking CP110 are viable and fertile and that centriole duplication, cilia formation, cell division, and cell cycle progression are not dramatically perturbed. We show that Drosophila CP110 has at least three important functions in vivo (Fig. 7): (1) it has a role in regulating centriole length although, under normal conditions, this role is subtle as centrioles are only slightly elongated in the absence of CP110, and slightly shortened when CP110 is overexpressed; (2) it has an important and previously undescribed role in ensuring that the centriolar MTs do not extend beyond the distal end of the centriole; and (3) surprisingly, it acts to suppress centriole overduplication when certain centriole duplication proteins are overexpressed.

Figure 7.

A schematic model of CP110 function in Drosophila. (A) In WT cells CP110 (green) performs two important functions: (1) it restricts the ability of core duplication proteins such as DSas-6, Ana2/STIL, and DSas-4/CPAP (shown collectively in yellow) to promote centriole elongation. This function can be performed by either CP110L or CP110S. (2) It prevents the MTs (purple) from extending beyond the distal end of the centriole. This function can only be performed efficiently by CP110L. (B) In the absence of CP110, the core centriole structure is slightly elongated, and the centriolar MTs can dramatically extend beyond the distal end of the centriole. (C) If certain centriole duplication proteins are overexpressed, a third function of CP110 is revealed (3), as it helps to suppress centriole overduplication. (D) If these duplication proteins are overexpressed in the absence of CP110, centriole overduplication is strongly enhanced. The mechanism by which CP110 suppresses this overduplication is unknown, but one possibility is depicted here, where the presence of elongated centrioles itself promotes overduplication by providing a larger platform for daughter centriole assembly.

In agreement with several previous studies in vertebrate cells in culture, our results in vivo show that the depletion of CP110 in Drosophila leads to the inappropriate protrusion of MTs from the distal end of the centrioles. The vertebrate studies, however, concluded that these extensions were either elongated centrioles (Kohlmaier et al., 2009; Schmidt et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009) or cilia (Spektor et al., 2007; Tsang et al., 2009; Kobayashi et al., 2011) because several centriolar and/or ciliary proteins (depending on the cell type examined) were recruited to the protrusions. By contrast, the protrusions in Drosophila wing disc cells are clearly not cilia or elongated centrioles: they are largely composed of singlet MTs rather than the doublets found in most centrioles and cilia in flies, and they lack several proteins that centrioles normally contain. The reason(s) for this difference is unclear. Perhaps it simply reflects species differences: in Drosophila, the centrioles are usually composed of doublet MTs (rather than triplets), the central cartwheel usually extends throughout the length of both mother and daughter centrioles (rather than being largely confined to the proximal end of the daughter centriole), and mother centrioles lack visible distal appendages; thus, the effect of CP110 loss on the distal end of the centriole may be different in flies and vertebrates. Alternatively, perhaps CP110 is required to prevent the overgrowth of the centriolar MTs in flies and vertebrates, but some centriole/cilia proteins can bind to these abnormal MT extensions in vertebrates, but not in flies.

Moreover, in agreement with the vertebrate data, we find that CP110 does play a part in regulating centriole length in flies (Fig. 7, pathway 1), it is just that this role appears to be relatively minor: in wing disc cells lacking CP110, centrioles are only ∼10% longer than those in WT cells, and in cells overexpressing CP110 they are ∼20% shorter. We suspect that multiple mechanisms normally act to regulate centriole length in Drosophila cells in vivo, so perturbing any single mechanism may have only a subtle effect. Importantly, the function of CP110 in setting centriole length does not appear to require the second conserved region of CP110 (CR2), as the overexpression of either CP110S (which lacks CR2) or CP110L leads to centriole shortening. Thus, our data strongly suggest that CP110 has two separable functions in flies: “capping” the length of the centriolar MTs, which only CP110L can perform, and helping to restrict centriole elongation, which can be performed by either CP110L or CP110S.

Our findings suggest some interesting possibilities of how CP110 might perform these functions. It has previously been shown, for example, that CP110 interacts with the MT-depolymerizing kinesins Kif24A and Klp10A in human and fly cells, respectively (Kobayashi et al., 2011; Delgehyr et al., 2012). The idea that CP110 might recruit and/or regulate the MT-depolymerizing activity of Klp10A at the distal tip of centrioles is attractive. Our 3D-SIM data suggest that CP110 is concentrated in a region just inside the distal end of the outer centriole wall. It is tempting to speculate that the interaction with CP110 might allow Klp10A to depolymerize any centriolar MTs that extend beyond the distal end of the centriole. Previous studies have shown that Klp10A can localize to the distal ends of centrioles (Delgehyr et al., 2012). A surprising point to emerge from our studies is that in flies Klp10A appears to play a more important part than CP110 in preventing centriole over-elongation and centriolar MT overgrowth: both of these defects are more pronounced in Klp10A mutant cells than in cells completely lacking CP110 (in the latter case because primarily MT doublets elongate from Klp10A mutant centrioles, whereas primarily MT singlets elongate from CP110Δ centrioles).

Our results demonstrate that CP110 can regulate centriole length in flies by counteracting the length-promoting activity of certain core centriole duplication proteins. It has previously been shown in vertebrate-cultured cells that the overexpression of one such protein, CPAP/SAS-4, promotes centriole elongation in a similar manner to CP110 depletion (Kohlmaier et al., 2009; Schmidt et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2009). We find that, in flies, overexpression of the core centriole duplication proteins DSas-4, DSas-6, or Ana2 can promote centriole elongation, but only if CP110 is absent. Thus, CP110 can counteract the centriole length-promoting activity of these proteins in vivo. Whether and how Klp10A might cooperate with CP110 to do this remains an interesting open question.

Surprisingly, we also find that CP110 can counteract the ability of centriole duplication proteins, when overexpressed, to promote centriole overduplication (Fig. 7, pathway 3). This was most unexpected because in cultured vertebrate cells CP110 is required for centriole overduplication (Chen et al., 2002; Kleylein-Sohn et al., 2007). The reason for this discrepancy is unclear, although we stress that our data demonstrate that CP110 is not normally required to regulate centriole duplication in flies in vivo; it only suppresses centriole overduplication when certain centriole duplication proteins are overexpressed (Fig. 7). It is unclear how CP110 performs this function. One interesting possibility is that CP110 could suppress centriole overduplication in flies simply by preventing centriole over-elongation, as overly long centrioles can promote overduplication when extra daughter centrioles form along the extended centriole length (Fig. 7 D; Kohlmaier et al., 2009). There is some evidence that argues against this idea: overexpressing DSas-4 in wing disc cells lacking CP110, for example, leads to centriole elongation but does not drive centriole overduplication in any of the tissues we examined. An alternative possibility is suggested by the observation that a lack of CP110 leads to low levels of premature centriole separation in spermatocytes, which is often associated with centriole overduplication (Dix and Raff, 2007; Stevens et al., 2009; Barrera et al., 2010). It is interesting to note that the overexpression of different centriole duplication proteins induces centriole overduplication to different extents, and in slightly different ways, in different tissues both in the presence (Peel et al., 2007; Stevens et al., 2010b) or absence of CP110 (Fig. S5). The reason for this is unclear, and more work is clearly required to analyze this phenomenon.

Although the mechanism by which CP110 suppresses centriole overduplication remains unclear, our observation that CP110 can protect cells from the damaging effects of centriole overduplication is potentially important. Although centrosome amplification per se does not seem to dramatically perturb cell physiology, at least in flies (Baumbach et al., 2012), centrosome amplification does predispose fly cells to form tumors (Basto et al., 2008) and is a common feature of many cancer cells (Nigg and Raff, 2009). Our data raise the possibility that the inactivation of CP110 might help promote centrosome amplification if the expression of certain key centriole duplication proteins is dysregulated.

Materials and methods

Fly stocks

The following fly lines were used in this study: w67 flies were used as WT; PBac{RB}Cp110[e00667] and P{XP}l(1)G0196[d05025] (Exelixis); hs-FLP38 (Bloomington, IN); CP110Δ (this study); DSas-4S2214 (Basto et al., 2006); and Klp10A (Delgehyr et al., 2012). The following transgenic lines were used, which all contain GFP or RFP fusions expressed from the Ubq promoter, which drives moderate expression in all tissues (Lee et al., 1988): CP110S-GFP and CP110L-GFP (this study); GFP-Sak, GFP-DSas-6, and DSas-4-GFP (Peel et al., 2007); Asl-GFP and GFP-Ana2 (Stevens et al., 2010b); GFP-Ana1 (Dobbelaere et al., 2008); GFP-PACT (Martinez-Campos et al., 2004); RFP-Cep135 (Roque et al., 2012); RFP-tubulin (Basto et al., 2008); and GFP-Fzr (Raff et al., 2002). Note that the GFP-Ana2 transgenic line used in this study was chosen because it did not, on its own, lead to centriole overduplication in spermatocytes; the line used in our previous study (Stevens et al., 2010b) did drive centriole overduplication in spermatocytes on its own.

RNA interference in S2 cells

RNA interference against GFP (control) and CP110 in S2 cells was performed as described previously (Dobbelaere et al., 2008) by culturing S2 cells in Schneider medium (S0146; Sigma-Aldrich) with 10% FBS (F9665; Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (15070-063; Gibco) at 25°C and seeding 3.5 × 106 cells in 24-well plates. dsRNA was made from PCR products using the Megascript T7 kit (Ambion) and the primers 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGACCAGCAGGATCAGGATACAAAG-3′ and 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTCTATGAGCTGACGCTGCTGATGAT-3′ for CP110-RNAi and 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAAGGTGATGCAACATACGGAAAAC-3′ and 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGTAATGGTTGTCTGGTAAAAGGAC-3′ for GFP-RNAi. RNAi mix (2.0 µg dsRNA, 5 µl Cellfectin [Invitrogen], and 50 µl serum-free medium [SFM]) was incubated for 30 min and then mixed with 450 µl SFM. Serum-containing medium was removed and the new mixture was added to the S2 cells (RNAi mix + SFM). After a 3–4-h incubation, 1 ml Schneider media was added and cells were incubated for 4 d.

Generation of transgenic lines

P element–mediated transformation vectors containing GFP fusions to CP110 were generated by introducing the cDNA GH03511 (DGRC) or the cDNA RE33938 (DGRC) containing the short and long isoform of CP110, respectively, into the Ubq-GFPCT Gateway vectors as described previously (Basto et al., 2008; full cloning details are available upon request). This resulted in a vector containing the pUbq promoter, the CP110 coding sequence (without the stop codon) inserted between the attR1 and attR2 sites, the mGFP6 gene, a KanR gene, and the white gene. Constructs were injected by BestGene.

Production of CP110 antibody

PCR was used to amplify the DNA encoding aa 301–549 of DCP110L, most of which is also present in CP110S (aa 301–539). The PCR products were subcloned into the pMal vector (New England Biolabs, Inc.). The resulting maltose-binding protein fusion protein was purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions and used to generate antibodies in rabbits. Eurogentec performed the injections and bleeds. The antibodies were affinity purified as described previously (Huang and Raff, 1999) by passing the rabbit antisera from the final bleed 1–2× through a column containing purified MBP fusion proteins covalently coupled to Affigel-15 beads (Bio-Rad Laboratories), until no MBP-specific antibodies remained. Protein-specific antibodies were then purified by passing the supernatant over Affigel beads coupled to the purified MBP-CP110 fusion protein, after which the column was washed with PBS + 0.5 M KCl. The bound CP110 antibody molecules were then eluted using 0.1 M glycine, pH 2.1, and neutralized rapidly with 1 M Tris, pH 8.5. After determining the antibody concentration in the eluted fractions using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories), 1 volume of 100% glycerol was added to the peak fraction (1 ml), which was then stored at −20°C. The remaining antibody-containing side fractions were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Antibodies for immunofluorescence and Western blotting

The following primary antibodies were used for immunofluorescence: rabbit anti-CP110 (this study—raised against amino acids 301–549 of CP110L), rabbit anti-Cnn (Lucas and Raff, 2007), rabbit anti-Asl (Conduit et al., 2010), rat anti-Asl (this study), guinea-pig anti-Asl (Roque et al., 2012), rabbit anti-D-PLP (Martinez-Campos et al., 2004), rabbit anti-Ana1 (Conduit and Raff, 2010), mouse acetylated tubulin (6-11B-1; Sigma-Aldrich), all 1:500; mouse anti-GTU88* (Sigma-Aldrich; Martinez-Campos et al., 2004), mouse anti–α-tubulin (DM1α; Sigma-Aldrich), all 1:1,000. The following secondary antibodies were used: Alexa Fluor 488, 568, 594 (used for SIM), 633, and 647 (Invitrogen), all 1:1,000; GFP-booster_atto488 and RFP-booster_atto594 (ChromoTek), all 1:500. DNA was labeled with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen). Rabbit anti-CP110 (this study) 1:500, rabbit anti–DSas-4 (Basto et al., 2006) 1:500, and rabbit anti–DSas-6 (Peel et al., 2007), rabbit anti-Asl (Conduit et al., 2010), and mouse actin (Sigma-Aldrich), all 1:2,500, were used for Western blotting.

Western blotting

Protein extracts were separated on 4–8% or 4–12% precast NuPAGE polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen). Proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose or Hypobond-P membranes (GE Healthcare) using a Mini Trans-Blot cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Membranes were probed with appropriate primary antibodies, washed, probed with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:7,500; GE Healthcare), incubated with Supersignal chemiluminescent reagent (ECL Advance Western Blot detection reagents [GE Healthcare] or Supersignal Dura [Thermo Fisher Scientific]), and then exposed to x-ray film (GE Healthcare).

PCR

PCRs were performed using standard Taq polymerase and dNTPs (Roche), Phusion PCR mastermix (New England Biolabs, Inc.), or 2× ReddyMix PCR Mastermix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the protocols recommended by the manufacturers. DNA was prepared by mashing 1–2 flies in an Eppendorf tube using a pipette tip filled with 50 µl squishing buffer (10 mM Tris HCl, pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8, 25 mM NaCl, and 200 µm/ml proteinase K). The Eppendorf tube was then incubated at 25°C for 30 min, boiled for 3 min at 95°C, and then stored at 4°C until it was used for PCR (on the same day of preparation). See Table S1 for PCR primer list and Table S2 for PCRs to assess the deletion of CP110 in the CP110Δ mutant stocks.

Immunofluorescence analysis of tissues

Brains, wing discs, and testes from third instar larvae or pupae were dissected in PBS and fixed by incubating them in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min, in 45% acetic acid for 15 s, and in 60% acetic acid on a coverslip for 3 min. The coverslip was then picked up with a microscope slide, put between two pieces of Whatman paper, and the brains were squashed by tapping the slide with a pencil. The slide was then immediately put into liquid nitrogen. When the slides were taken out of the liquid nitrogen, the coverslips were flicked off with a razor blade. The slides were incubated in cold 100% methanol at −20°C for 8 min, washed 4x with PBT (PBS + 0.1% Triton X-100) for 10 min, and incubated in PBT containing the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The slides were then washed 3× with PBT for 5 min and incubated in PBT containing the appropriate secondary antibodies at 25°C for 3–4 h. After three washes with PBT for 15 min, the slides were finally incubated in PBT + Hoechst 33342 (0.5 µg/ml) for 10 min, dried, and mounted in mounting medium. To stain axonemes in testes using an acetylated tubulin antibody, testes were dissected in PBS and then incubated in 100 µM colchicine (in Schneider medium) for 30 min. The fixation and immunostaining was then performed as described above. Samples were imaged at 21°C on a confocal microscope system (Fluoview FV1000 IX81; Olympus) using a 60×/1.4 NA oil objective and FV1000 software (Olympus), or on a microscope (Axioskop II; Carl Zeiss) with a CoolSnapHQ camera using a 60× oil immersion lens with MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices). All images shown are maximum intensity projections and were processed using Volocity (PerkinElmer) and Adobe Photoshop software.

Live analysis of centriole duplication in embryos

1–4-h-old embryos expressing the various GFP and RFP fusion proteins were dechorionated by hand on sticky tape using the tips of forceps and mounted on strips of glue (sticky tape dissolved in heptane) on a glass-bottom dish. The embryos were then covered with Voltalef oil and immediately imaged at 21°C using a spinning disk confocal system (ERS; PerkinElmer) on a microscope (Axiovert 200M; Carl Zeiss) with a 63×/1.4 NA oil objective and a charge-coupled device camera (Orca ER; Hamamatsu Photonics) with Ultraview ERS software (PerkinElmer). Movies and images shown are maximum intensity projections and were processed using Volocity (PerkinElmer) and Adobe Photoshop software.

Transmission electron microscopy and electron tomography

Late pupal testes or wing discs from third instar larvae were dissected in PBS and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) for 2 h at 4°C. RNAi-treated S2 cells attached to concanavalin A–coated microscope slips were washed once with PBS and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 12 min. Testes, wing discs, and S2 cells were then washed in cacodylate buffer and post-fixed in 1% OsO4, followed by several washes in dH2O. Samples were then en-bloc stained with 0.5% uranyl acetate overnight at 4°C, washed in dH2O, dehydrated in an ethanol series, and embedded in Agar 100. Polymerization was at 60°C for 42 h. 150-nm-thick serial sections were cut using an ultramicrotome (Reichert-Jung Ultracut E; Leica) and stained with lead citrate. For EM tomography, colloidal gold particles of 15 nm were applied to both sides of the grid sections. The samples were then imaged using a transmission microscope (TECNAI T12; FEI) at 13,000× with SerialEM (Mastronarde, 2005). For EM tomography, dual-axis tilt series (55°–55°) of centrioles were acquired. Images were aligned and tomograms reconstructed by R-weighted back-projection with the user interface eTomo, and analysis was performed with the software package IMOD (Kremer et al., 1996).

3D-structured illumination microscopy

Preparation, fixation, and staining of squashed late pupal testes for 3D-SIM was similar to the protocol for immunofluorescence analysis with the following minor alterations: testes were dissected in PBS, placed on an 18 × 18-mm coverslip, and cut open using tungsten needles. The coverslip was then picked up with a siliconized 22 × 64-mm coverslip, placed between two pieces of Whatman paper, and gently squashed by tapping the coverslips with a pencil. The coverslips were then immediately put into liquid nitrogen. The squashed testes on the 18 × 18-mm coverslips were then processed further as described in the Immunofluorescence analysis of tissues section. Images were taken at 21°C on a microscope (OMX; Applied Precision) with a 60×/1.35 NA oil objective (Olympus) and were processed using SoftWorx software (Applied Precision). Images shown are maximum intensity projections of several z-slices in the central area of the centrioles that were processed using Volocity (PerkinElmer) and Adobe Photoshop software.

Quantification of centriole length in wing discs by EM and in spermatocytes by immunofluorescence

To measure centriole length in interphase cells from wing discs, images of centrioles in longitudinal orientation (oriented by tilting the EM stage) were taken on a transmission electron microscope. The length of the MT doublets within the electron-dense area was measured using the line tool in Volocity (PerkinElmer). To measure centriole length in primary spermatocytes, Z-stacks (0.5-µm steps, spanning the entire centriole volume) were taken on the Fluoview confocal microscope (Olympus) described above. The length of the centrioles was measured using the line tool in Volocity (PerkinElmer) in the extended focus mode. The average centriole length in wing discs or spermatocytes was calculated for each wing disc or testis, respectively, and these values were then used to calculate an average centriole length. The significance of any difference was tested using the Mann-Whitney test in Prism (GraphPad Software) assuming unequal variance.

Measuring PCM size

To quantify PCM size, Z-stacks (0.2-µm steps, spanning the entire centrosome volume) of WT or CP110Δ brain cells in prometaphase to metaphase stained for Asl, Cnn, and DNA were acquired using the Fluoview confocal microscope (Olympus) described above. The total amount of Cnn fluorescence in each centrosome was measured using the following protocol in Volocity software (PerkinElmer). Objects with an intensity higher than the background (determined by eye) in the Cnn channel were found, then objects were excluded by size (0.4 µm3, to exclude objects that were not centrosomes), then touching objects were separated (0.1 µm3), and finally objects were clipped to the region of interest (the mitotic cell). The sum intensities of Cnn in each centrosome were measured without applying a background correction because there was no significant difference between Cnn background staining in WT and mutant genotypes. The average sum intensity of Cnn in centrosomes was then calculated for each brain separately and these values per brain were finally averaged and shown in a graph. The significance of any difference was tested using the Mann-Whitney test in Prism (GraphPad Software) assuming unequal variance. All error bars shown correspond to the standard error.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that CP110Δ mutants have no obvious defects in centriole duplication, PCM recruitment, or mitotic spindle formation. Fig. S2 shows the defects in axoneme ultrastructure and centriole cohesion in CP110Δ testes. Fig. S3 shows that MT singlets and doublets elongate from CP110Δ and Klp10A centrioles, respectively. Fig. S4 shows the analysis of DSas-4-GFP overexpression in wing discs. Fig. S5 shows that centrioles frequently overduplicate in CP110Δ primary spermatocytes expressing Asl-GFP or GFP-Ana2. Video 1 shows that CP110 regulates the length of the centriolar MTs. Video 2 shows that CP110 regulates the length of centriolar MTs in S2 cells. Video 3 shows that MT singlets elongate from CP110Δ centrioles. Video 4 shows that Klp10A regulates the length of the centriolar MTs. Table S1 shows a list of PCR primers used in this study. Table S2 shows a list of PCRs that were used to assess the deletion of CP110 in the CP110Δ mutant stocks. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201305109/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Raff laboratory for advice and comments on the manuscript.

The research was funded by a Wellcome Trust PhD studentship (to A. Franz); a European Molecular Biology Organization fellowship, a Human Frontier Science Program fellowship, a Lise-Meitner Fellowship and the MFPL Vienna International PostDoctoral Program for Molecular Life Sciences (to J. Dobbelaere); and a Cancer Research UK program grant (C5395/A10530; to H. Roque, S. Saurya, and J.W. Raff). Microscopy work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award (091911) to the Micron Oxford Advanced Bioimaging Unit.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- 3D-SIM

- 3D-structured illumination microscopy

- CR

- conserved region

- DSas-4

- Drosophila SAS-4

- ET

- electron tomography

- MT

- microtubule

- WT

- wild type

References

- Barrera J.A., Kao L.-R., Hammer R.E., Seemann J., Fuchs J.L., Megraw T.L. 2010. CDK5RAP2 regulates centriole engagement and cohesion in mice. Dev. Cell. 18:913–926 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basto R., Lau J., Vinogradova T., Gardiol A., Woods C.G., Khodjakov A., Raff J.W. 2006. Flies without centrioles. Cell. 125:1375–1386 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basto R., Brunk K., Vinadogrova T., Peel N., Franz A., Khodjakov A., Raff J.W. 2008. Centrosome amplification can initiate tumorigenesis in flies. Cell. 133:1032–1042 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumbach J., Levesque M.P., Raff J.W. 2012. Centrosome loss or amplification does not dramatically perturb global gene expression in Drosophila. Biol. Open. 1:983–993 10.1242/bio.20122238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt-Dias M., Hildebrandt F., Pellman D., Woods G., Godinho S.A. 2011. Centrosomes and cilia in human disease. Trends Genet. 27:307–315 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Shen Y., Zhu L., Xu Y., Zhou Y., Wu Z., Li Y., Yan X., Zhu X. 2012. miR-129-3p controls cilia assembly by regulating CP110 and actin dynamics. Nat. Cell Biol. 14:697–706 10.1038/ncb2512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho-Santos Z.Z., Machado P.P., Alvarez-Martins I.I., Gouveia S.M.S., Jana S.C.S., Duarte P.P., Amado T.T., Branco P.P., Freitas M.C.M., Silva S.T.N.S., et al. 2012. BLD10/CEP135 is a microtubule-associated protein that controls the formation of the flagellum central microtubule pair. Dev. Cell. 23:412–424 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Indjeian V.B., McManus M., Wang L., Dynlacht B.D. 2002. CP110, a cell cycle-dependent CDK substrate, regulates centrosome duplication in human cells. Dev. Cell. 3:339–350 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00258-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduit P.T., Raff J.W. 2010. Cnn dynamics drive centrosome size asymmetry to ensure daughter centriole retention in Drosophila neuroblasts. Curr. Biol. 20:2187–2192 10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduit P.T., Brunk K., Dobbelaere J., Dix C.I., Lucas E.P., Raff J.W. 2010. Centrioles regulate centrosome size by controlling the rate of Cnn incorporation into the PCM. Curr. Biol. 20:2178–2186 10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angiolella V., Donato V., Vijayakumar S., Saraf A., Florens L., Washburn M.P., Dynlacht B., Pagano M. 2010. SCF(Cyclin F) controls centrosome homeostasis and mitotic fidelity through CP110 degradation. Nature. 466:138–142 10.1038/nature09140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgehyr N., Rangone H., Fu J., Mao G., Tom B., Riparbelli M.G., Callaini G., Glover D.M. 2012. Klp10A, a microtubule-depolymerizing kinesin-13, cooperates with CP110 to control Drosophila centriole length. Curr. Biol. 22:502–509 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix C.I., Raff J.W. 2007. Drosophila Spd-2 recruits PCM to the sperm centriole, but is dispensable for centriole duplication. Curr. Biol. 17:1759–1764 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbelaere J., Josué F., Suijkerbuijk S., Baum B., Tapon N., Raff J. 2008. A genome-wide RNAi screen to dissect centriole duplication and centrosome maturation in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 6:e224 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J., Glover D.M. 2012. Structured illumination of the interface between centriole and peri-centriolar material. Open Biol. 2:120104 10.1098/rsob.120104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz S.C., Liem K.F., Jr, Anderson K.V. 2012. The spinocerebellar ataxia-associated gene Tau tubulin kinase 2 controls the initiation of ciliogenesis. Cell. 151:847–858 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González C., Tavosanis G., Mollinari C. 1998. Centrosomes and microtubule organisation during Drosophila development. J. Cell Sci. 111:2697–2706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges M.E., Scheumann N., Wickstead B., Langdale J.A., Gull K. 2010. Reconstructing the evolutionary history of the centriole from protein components. J. Cell Sci. 123:1407–1413 10.1242/jcs.064873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Raff J.W. 1999. The disappearance of cyclin B at the end of mitosis is regulated spatially in Drosophila cells. EMBO J. 18:2184–2195 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleylein-Sohn J., Westendorf J., Le Clech M., Habedanck R., Stierhof Y.-D., Nigg E.A. 2007. Plk4-induced centriole biogenesis in human cells. Dev. Cell. 13:190–202 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Tsang W.Y., Li J., Lane W., Dynlacht B.D. 2011. Centriolar kinesin Kif24 interacts with CP110 to remodel microtubules and regulate ciliogenesis. Cell. 145:914–925 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmaier G., Loncarek J., Meng X., McEwen B.F., Mogensen M.M., Spektor A., Dynlacht B.D., Khodjakov A., Gönczy P. 2009. Overly long centrioles and defective cell division upon excess of the SAS-4-related protein CPAP. Curr. Biol. 19:1012–1018 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer J.R.J., Mastronarde D.N.D., McIntosh J.R.J. 1996. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 116:71–76 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.S., Simon J.A., Lis J.T. 1988. Structure and expression of ubiquitin genes of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:4727–4735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., D’Angiolella V., Seeley E.S., Kim S., Kobayashi T., Fu W., Campos E.I., Pagano M., Dynlacht B.D. 2013. USP33 regulates centrosome biogenesis via deubiquitination of the centriolar protein CP110. Nature. 495:255–259 10.1038/nature11941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas E.P., Raff J.W. 2007. Maintaining the proper connection between the centrioles and the pericentriolar matrix requires Drosophila centrosomin. J. Cell Biol. 178:725–732 10.1083/jcb.200704081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Campos M., Basto R., Baker J., Kernan M., Raff J.W. 2004. The Drosophila pericentrin-like protein is essential for cilia/flagella function, but appears to be dispensable for mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 165:673–683 10.1083/jcb.200402130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde D.N. 2005. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol. 152:36–51 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg E.A., Raff J.W. 2009. Centrioles, centrosomes, and cilia in health and disease. Cell. 139:663–678 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel N., Stevens N.R., Basto R., Raff J.W. 2007. Overexpressing centriole-replication proteins in vivo induces centriole overduplication and de novo formation. Curr. Biol. 17:834–843 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff J.W., Jeffers K., Huang J.-Y. 2002. The roles of Fzy/Cdc20 and Fzr/Cdh1 in regulating the destruction of cyclin B in space and time. J. Cell Biol. 157:1139–1149 10.1083/jcb.200203035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roque H., Wainman A., Richens J., Kozyrska K., Franz A., Raff J.W. 2012. Drosophila Cep135/Bld10 maintains proper centriole structure but is dispensable for cartwheel formation. J. Cell Sci. 125:5881–5886 10.1242/jcs.113506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T.I., Kleylein-Sohn J., Westendorf J., Le Clech M., Lavoie S.B., Stierhof Y.-D., Nigg E.A. 2009. Control of centriole length by CPAP and CP110. Curr. Biol. 19:1005–1011 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnen K.F., Schermelleh L., Leonhardt H., Nigg E.A. 2012. 3D-structured illumination microscopy provides novel insight into architecture of human centrosomes. Biol. Open. 1:965–976 10.1242/bio.20122337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spektor A., Tsang W.Y., Khoo D., Dynlacht B.D. 2007. Cep97 and CP110 suppress a cilia assembly program. Cell. 130:678–690 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens N.R., Dobbelaere J., Wainman A., Gergely F., Raff J.W. 2009. Ana3 is a conserved protein required for the structural integrity of centrioles and basal bodies. J. Cell Biol. 187:355–363 10.1083/jcb.200905031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens N.R., Roque H., Raff J.W. 2010a. DSas-6 and Ana2 coassemble into tubules to promote centriole duplication and engagement. Dev. Cell. 19:913–919 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens N.R., Dobbelaere J., Brunk K., Franz A., Raff J.W. 2010b. Drosophila Ana2 is a conserved centriole duplication factor. J. Cell Biol. 188:313–323 10.1083/jcb.200910016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.-J.C., Fu R.-H., Wu K.-S., Hsu W.-B., Tang T.K. 2009. CPAP is a cell-cycle regulated protein that controls centriole length. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:825–831 10.1038/ncb1889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang W.Y., Spektor A., Luciano D.J., Indjeian V.B., Chen Z., Salisbury J.L., Sánchez I., Dynlacht B.D. 2006. CP110 cooperates with two calcium-binding proteins to regulate cytokinesis and genome stability. Mol. Biol. Cell. 17:3423–3434 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang W.Y., Bossard C., Khanna H., Peränen J., Swaroop A., Malhotra V., Dynlacht B.D. 2008. CP110 suppresses primary cilia formation through its interaction with CEP290, a protein deficient in human ciliary disease. Dev. Cell. 15:187–197 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang W.Y., Spektor A., Vijayakumar S., Bista B.R., Li J., Sánchez I., Duensing S., Dynlacht B.D. 2009. Cep76, a centrosomal protein that specifically restrains centriole reduplication. Dev. Cell. 16:649–660 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.