Abstract

Background

Peroxynitrite, the product of the reaction between superoxide radicals and nitric oxide, is an elusive oxidant of short half-life and low steady-state concentration in biological systems; it promotes nitroxidative damage.

Scope of Review

We will consider kinetic and mechanistic aspects that allow rationalizing the biological fate of peroxynitrite from data obtained by a combination of methods that include fast kinetic techniques, electron paramagnetic resonance and kinetic simulations. In addition, we provide a quantitative analysis of peroxynitrite production rates and conceivable state-state levels in living systems.

Major Conclusions

The preferential reactions of peroxynitrite in vivo include those with carbon dioxide, thiols and metalloproteins; its homolysis represents only < 1 % of its fate. To note, carbon dioxide accounts for a significant fraction of peroxynitrite consumption leading to the formation of strong one-electron oxidants, carbonate radicals and nitrogen dioxide. On the other hand, peroxynitrite is rapidly reduced by peroxiredoxins, which represent efficient thiol-based peroxynitrite detoxification systems. Glutathione, present at mM concentration in cells and frequently considered a direct scavenger of peroxynitrite, does not react sufficiently fast with it in vivo; glutathione mainly inhibits peroxynitrite-dependent processes by reactions with secondary radicals. The detection of protein 3-nitrotyrosine, a molecular footprint, can demonstrate peroxynitrite formation in vivo. Basal peroxynitrite formation rates in cells can be estimated in the order of 0.1 to 0.5 μM s−1 and its steady-state concentration ~ 1 nM.

General Significance

The analysis provides a handle to predict the preferential fate and steady-state levels of peroxynitrite in living systems. This is useful to understand pathophysiological aspects and pharmacological prospects connected to peroxynitrite.

Keywords: Free radicals, nitrotyrosine, peroxynitrite, oxidative stress, superoxide radical and nitric oxide

1. PEROXYNITRITE BIOCHEMISTRY

1.1 Peroxynitrite formation pathways

The reaction between the free radicals nitric oxide (•NO) and superoxide (O2•−) leads to the diffusion-controlled formation of peroxynitrite1, a potent oxidizing and nitrating agent formed in vivo [1].

| (1) |

Nitric oxide is a relatively stable and mildly reactive free radical mainly generated enzymatically from L-arginine, NADPH and oxygen in a reaction catalyzed by several isoforms of nitric oxide synthase (NOS). Nitric oxide is a ubiquitous intracellular messenger, which mediates multiple physiological processes, including regulation of blood pressure, neurotransmission, immune response and platelet aggregation [2,3,4]. Its consumption in biological systems is determined by reactions preferentially with other paramagnetic species, such as organic radicals (tyrosyl and peroxyl radicals) or transition metal centers, most remarkably with oxyhemoglobin, which represents an important fate of •NO in the vasculature [5,6]. Another relevant reaction responsible for •NO depletion is with O2•− to yield peroxynitrite [2,4,7,8]. The sources of O2•−, the one electron reduction product of molecular dioxygen, include enzymes such as NAD(P)H oxidase, xanthine oxidase and uncoupled NOS, the electron leakage in the mitochondrial respiratory chain, and through redox cycling of xenobiotics, among other possible mechanisms. O2•− can react with iron sulfur clusters, transition metal centers and thiols but the main route for its consumption in biological systems is the reaction with superoxide dismutases (SOD), which are extremely efficient in catalyzing O2•− dismutation to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and dioxygen (rate constant > 109 M−1 s−1) [9,10,11]. This preferential reaction with SODs, which are abundant (concentration > 10 μM) and ubiquitous enzymes, keeps the concentration of O2•− at a low steady-state level (10−9–10−12 M range) [12,13,14]. However, this value can increase several-fold under conditions of altered cellular homeostasis and during inflammatory processes.

An early evidence of the biological formation of peroxynitrite was obtained in experiments that showed that SOD prolonged the half-life and biological effects of the •NO [15,16]. The rate constant of O2•− reaction with •NO to form peroxynitrite (Eq. 1), has been reported within the range of (4 – 16) × 109 M−1 s−1 [17,18,19,20], which is a higher value than that of the reaction with Mn or Cu,Zn-SOD (1–2 × 109 M−1 s−1 ) [10,11]. Therefore, •NO can be produced at a sufficient concentration and react fast enough to outcompete SOD for its reaction with O2•−. In fact, it can be estimated that in the presence of physiological concentrations of SOD ~10 to 20 μM, •NO produced at micromolar concentrations will be able to outcompete SOD and trap a significant fraction of the O2•− formed.

Nitric oxide is a hydrophobic uncharged radical which can easily permeate cell membranes and diffuse outside the cell, while O2•− is much more short-lived and due to its anionic character (pKa ~ 4.8) has restricted diffusion across biomembranes. For this, peroxynitrite formation, which requires the simultaneous generation of both radicals, will be spatially circumscribed to the sites of O2•− formation. The steady-state concentrations of •NO and O2•− also command the rate of peroxynitrite formation. Considering a cellular scenario where diverse competitive scavenging occur, particularly direct competition between SOD and •NO for the reaction with O2•−, from a combination of experimental values and the known rate constants it was estimated that the maximal rate of peroxynitrite formation in endothelial cell mitochondria under basal metabolic conditions is 0.3 μM s−1 [21,22]. In this sense, from a reported kinetic model that included the effects of multiple cellular targets, it was estimated intracellularly steady-state concentrations of peroxynitrite in the nanomolar range [21,23]. Even though the levels of •NO and O2•− in vivo are regulated efficiently by the scavengers and disposal systems, the concentration could increase several-fold under altered cellular homeostasis and therefore influence the rate of peroxynitrite formation. Thus, peroxynitrite flux can be increased when other scenarios are considered, such as in inflammatory cells, where both •NO and O2•− production rates are largely enhanced. For example, in selected cellular compartments such as the phagosome, fluxes of peroxynitrite produced by immuno-stimulated (i.e. cytokine exposure leading to iNOS expression) and activated (i.e. trigger of the respiratory busrt) macrophage was estimated as ~ 0.83 – 1.66 μM s−1 in the murine cell line J774A.1 [24].

1.2 Physicochemical properties of peroxynitrite

Peroxynitrite is more reactive than its precursors •NO and O2•−. With one- and two-electron reduction potentials of E°′(ONOO−, 2H+/•NO2, H2O) = + 1.4 V and E°′(ONOO−, 2H+/NO2−, H2O) = + 1.2 V, respectively [25,26], peroxynitrite is a relatively strong biological oxidant and nitrating agent able to react with a wide range of biomolecules. The anionic form of peroxynitrite (ONOO−) exists in equilibrium with its conjugated acidic form (ONOOH) (pKa ~ 6.8, Eq. 2). Thus, under biological conditions both species will be present at ratios depending on the local pH. For example, at the physiological pH of 7.4, peroxynitrite anion will be present in proportion of 80%.

| (2) |

The coexistence of the anionic and protonated forms of peroxynitrite is also relevant since they have different reactivity [21] and diffusional [27,28] properties2.

The anionic form of peroxynitrite displays a moderate absorbance in the visible near the ultraviolet region (UV). The absorption spectra in aqueous alkaline solution consists of a single band with a maximum centered at 302 nm, which has been used to quantify peroxynitrite and follow its reactions, using the reported extinction coefficient (ε302 = 1670 M−1 cm−1) [30].

2. KINETICS AND REACTION MECHANISMS OF PEROXYNITRITE

Peroxynitrite biochemistry is dictated by the kinetics of its formation and decay together with its partial limitation to diffuse through biological membranes: most importantly the availability of targets in different cell compartments critically modulate its biological fate. In biological systems, peroxynitrite promotes the oxidative modification of target molecules by different types of reactions involving: a) peroxynitrite-derived radicals from the homolytic cleavage of peroxynitrous acid or secondary to the reaction with carbon dioxide or b) by direct oxidation reactions.

2.1 Peroxynitrite reactivity

2.1.1 Homolytic cleavage of ONOOH

In the absence of direct targets peroxynitrite anion is relatively stable. However, peroxynitrous acid decays rapidly by homolysis of its peroxo bond (k = 0.9 s−1 at 37 °C and 0.26 s−1 at 25 °C and pH 7.4) leading to the formation of nitrogen dioxide (•NO2) and hydroxyl radicals (•OH) in ~30% yield whereas the rest of peroxynitrous acid directly isomerizes to nitrate (NO3−) [31,32,33]. Hydroxyl radical is a much stronger oxidant than •NO2, however it reacts very rapidly with most biomolecules (~109 M−1 s−1) in a non-selective manner, with addition reactions predominating over one-electron abstractions. In contrast, •NO2 reacts at slower rates but represents a more selective one-electron oxidant. Thus, these peroxynitrite-derived radicals (•OH and •NO2) can mediate several reactions that may lead to the oxidation or nitration of different targets, such as tyrosine nitration and lipid peroxidation.

Considering the relative slowness of ONOOH homolysis compared to the reaction of peroxynitrite with multiple cellular targets that react directly with relatively high rate constants (vide infra), it can be estimated that in biological systems, most peroxynitrite formed will be consumed by direct reactions, with < 1 % evolving to •NO2 and •OH, so the homolytic route is just a modest component of peroxynitrite reactivity in the aqueous compartment [34]. However, the homolytic decomposition of ONOOH may be a relevant process in hydrophobic compartments initiating radical-dependent processes such as lipid peroxidation and even protein and lipid nitration [35,36,37,38,39].

2.1.2 Direct reactions

Peroxynitrite anion or peroxynitrous acid react directly with different biomolecules by one- or two-electron oxidation reactions. For example, low molecular weight or protein thiols, selenium compounds, metal centers and carbon dioxide (CO2), constitute the main reported targets of peroxynitrite in vivo, with second-order rate constants in the range of ~103 to 107 M−1 s−1 [40,41]. Those reactions with endogenous components that modulate peroxynitrite reactivity and its possible fates in a cellular system will be described in detail.

i) Carbon dioxide

One of the most biologically relevant reactions of peroxynitrite is its fast reaction with CO2 (in equilibrium with bicarbonate anion), which is present at relatively high concentrations (≥ 1.3 mM) in biological systems. The nucleophilic addition of ONOO• to CO2, with a second-order rate constant of 4.6 × 104 M−1 s−1 (at pH 7.4 and 37 °C), yields a transient nitroso-peroxocarbonate (ONOOCO2−) which rapidly decomposes homolytically to carbonate radical (CO3•−) and •NO2 in ~ 34% yields, with the remaining yielding carbon dioxide and nitrate [42,43,44,45]. With reduction potentials of E°′(CO3•−, H+/HCO3−) = + 1.78 V and E°′(•NO2/NO2−) = + 0.99 V, CO3•− is a relatively strong one-electron oxidant whereas •NO2 is a more moderate oxidant and also a nitrating agent [46,47,48,49]. Thus, CO2 instead of being a “scavenger” of peroxynitrite, it rather redirects its reactivity promoting the formation of two new strong and short-lived one-electron oxidants that can lead to nitro-oxidative events, targeting mainly towards amino acids in proteins (most notably tryptophan, tyrosine, cysteine, methionine and histidine residues) [50]. Considering the ubiquity of CO2, its reactivity with peroxynitrite and the potentially oxidant character of the products, CO2 can be used as a hinge of peroxynitrite reactivity. Carbon dioxide outcompetes with other biological targets for the direct reaction with peroxynitrite and could inhibit their two-electron oxidation. However, most of the target would be one-electron oxidized by the peroxynitrite-derived radicals. As a consequence, depending on the target concentration and on the second-order rate constant of its reaction with peroxynitrite, CO2 would divert target oxidation from two to one-electron mechanisms particularly at neutral pH. Based on the rate constant (k = 4.6 × 104 M−1 s−1, at pH 7.4 and 37 °C) and CO2 concentrations found in cell compartments ([T] ~ 1.3 mM), the product k[T] ~ 60 s−1 can be used to parameterize the reactivity of peroxynitrite toward CO2 and due its ubiquity, also as a benchmark to assess the relative importance of other biotargets for a peroxynitrite scavenger to be competitive, as will be described later.

ii) Thiols

Thiols are preferential targets of reactive species. The apparent second-order rate constants of peroxynitrite with cysteine, glutathione (GSH), homocysteine and the single thiol group of albumin (Cys34) are ~ 103 M−1 s−1 at pH 7.4 and 37 °C, about three orders of magnitude faster than the corresponding reactions with hydrogen peroxide [8,47,51]. Moreover, rate constants in the order of 106 – 107 M−1 s−1 have been reported for the reaction of peroxynitrite with very reactive thiols in proteins, such as those present in peroxiredoxins (Prx), which constitute an efficient key detoxification system of peroxynitrite [21,52,53,54]

The direct two-electron oxidation of thiols (RSH) by peroxynitrite results in the formation of nitrite and sulfenic acid (RSOH) as intermediate, which reacts with another thiol forming the corresponding disulfide (RSSR). The mechanism involves the nucleophilic attack of the thiolate on one of the peroxidic oxygens of peroxynitrous acid, with nitrite as leaving group [51]. Alternatively, the one-electron oxidation of thiols by the radicals derived from peroxynitrite homolysis in the absence or presence of CO2, results in a sulfur-centered radical (thiyl radical, RS•), which is highly reactive and can recombine to form disulfide bridges (RSSR) or react with a thiolate to yield a disulfide radical anion (RSSR•−) that in the presence of oxygen can promote the formation of disulfide and O2•−. Alternatively, RS• can initiate an oxygen-dependent chain reaction to produce a number of secondary radicals, including thiyl peroxyl radical (RSOO•) and sulfinyl radical (RSO•) that can finally yield sulfenic acid [46,55,56].

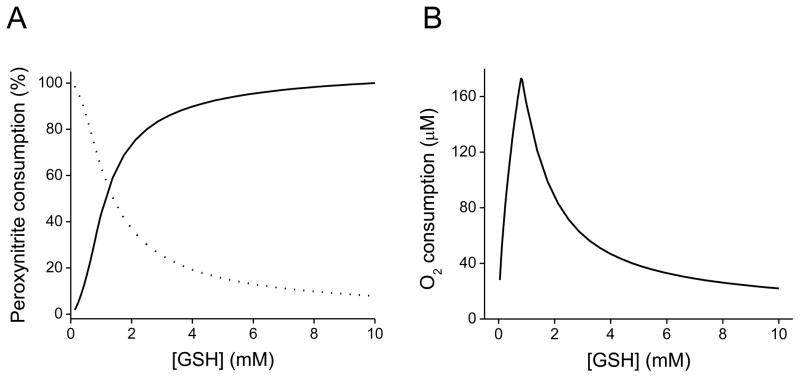

In order to kinetically substantiate these peroxynitrite-mediated direct versus radical pathways, computer-assisted simulations of peroxynitrite reaction with GSH were performed according to the reported rate constants shown in Table 1. As observed in Figure 1A, at low GSH concentrations, the homolysis of peroxynitrite predominates (0.9 s−1, pH 7.4, 37 °C) yielding OH• and •NO2 which can oxidize GSH in a one-electron process, leading to the formation of glutationyl radical (GS•). When the concentration of GSH increases, the direct reaction of peroxynitrite as a two-electron oxidation process becomes more significant. In addition, peroxynitrite-mediated oxidation of low molecular weight thiols is associated with oxygen consumption, in agreement with previous reported observations [46,55,57]. In this sense, from the computer-simulated profiles of the total oxygen consumption versus increasing GSH concentrations, a biphasic profile was obtained (Figure 1B). This oxygen consumption pattern that quantitatively reproduced the reported experimental results obtained from the peroxynitrite-dependent cysteine oxidation, is also consistent with the two competing pathways participating in the oxidation of GSH by peroxynitrite [55]. At low GSH concentrations (≤ 0.8 mM), the total consumption increases since the radicals derived from peroxynitrite homolysis can oxidize GSH in a one-electron process, leading to the formation of GS•, which is capable of reacting with oxygen triggering an oxygen-dependent radical chain reaction that could amplify the one-electron oxidation pathway. Indeed, •OH reacts with GSH leading to GS• with a reported rate constant of 2.3 × 1010 M−1 s−1 [58]. On the other hand, at high GSH concentrations (> 0.8 mM), oxygen consumption decreases due to the preferential direct reaction with peroxynitrite. In fact, the observed decrease in oxygen consumption at high GSH concentrations disappeared when the direct reaction was not included in the simulation. In addition, the simulation also demonstrates that the reaction that most contributes to oxygen consumption is that of GS• with oxygen, given that deletion of this reaction dropped oxygen consumption by one order of magnitude.

Table 1.

Reactions participating in the aerobic oxidation of GSH by peroxynitrite that were used in the simulation of Figure 1.

| Reactiona | Rate constant | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Reactions involved in peroxynitrite decay | ||

| ONOOH → •NO2 + •OH | 0.27 s−1 b | [47] |

| ONOOH → NO3− + H+ | 0.63 s−1 b | [47] |

| •OH + NO2− → •NO2 + OH− | 6 × 109 M−1 s−1 | [58] |

| 2 •NO2 ⇌ N2O4 | 4.5 × 108 M−1 s−1 (f) c; 6.9 × 103 s−1 (r) | [58] |

| N2O4 + H2O → NO2− + NO3− + H+ | 1 × 103 s−1 | [162] |

| •NO2 + O2•− ⇌ O2NOO− | 4.5 × 109 M−1 s−1 (f); 1.1s−1 (r) | [44] [163] |

| O2NOO− → O2 + NO2− | 1.3s−1 | [44] [163] |

| 2 O2•− + 2 H+ → O2 + H2O2 | 2 × 105 M−1 s−1 | [164] |

| ONOO− + CO2 → •NO2 + CO3•− | 1.6 × 104 M−1 s−1 d | [43] |

| ONOO− + CO2 → •NO3− + CO2 | 3.0 × 104 M−1 s−1 d | [43] |

| CO3•− + •NO2 → NO2− + CO2 | 1 × 109 M−1 s−1 | [58] |

| CO3•− + O2•− → CO32− + O2 | 6.5 × 108 M−1 s−1 | [58] |

| Additional reactions in the presence of GSH | ||

| GSH+ ONOOH → GSOH + NO2− | 1.35 × 103 M−1 s−1 | [47,51] |

| GSOH + GSH → GSSG + OH− | 1 × 105 M−1 s−1 | [165] |

| GSH + H2O2 → GSOH + OH− | 0.87 M−1 s−1 | [166] |

| GSH + •NO2 → GS• + NO2− + H+ | 2 × 107 M−1 s−1 | [75] |

| GSH + •OH → GS• + H2O | 2.3 × 1010 M−1 s−1 | [58] |

| GSH + O2•− → GS• + H2O2 | 200 M−1 s−1 f | [167] |

| GSH + CO3•− → GS• + CO32− | 5.3 × 106 M−1 s−1 | [58] |

| GS•+ GS• → GSSG | 7.5 × 108 M−1 s−1 | [168] |

| GS•+ GSH ⇌ GSSG•− | 1 × 108 M−1 s−1 (f); 2.5 × 105 s−1 (r) | [169] |

| GS• + O2 → GSOO• | 2 × 109 M−1 s−1 | [170] |

| GS• + •NO → GSNO | 1 × 109 M−1 s−1 e | [171] |

| GS• + •NO2 → GSNO2 | 3 × 109 M−1 s−1 e | [171] |

| GSSG•− + O2 → GSSG + O2•− | 1.6 × 108 M−1 s−1 | [172] |

| GSOO• + GSH → + GSO• + GSOH | 2 × 106 M−1 s−1 | [173] |

Reactions were considered at neutral pH and 37 °C when data were available.

Calculated considering the rate constant for peroxynitrous acid decay (0.9 s−1 at pH 7.4) [47] and the radical yield (30 %) [32,33].

(f) and (r) represent forward and reverse kinetic constants, respectively.

Calculated considering the rate constant for the reaction of ONOO− with CO2 (k = 4.6 × 104 M−1 s−1) [43] and the radical yields (34 and 66 %) [45,171,174]e. The rate constants for the recombination reaction of GS• with •NO and •NO2 were estimated to be similar to that of the recombination reaction of •NO and •NO2 with tyrosyl radicals respectively, as reported previously [45,171,174].

Figure 1. Computer-assisted simulations of the peroxynitrite-mediated decay in the presence of GSH.

(A) Simulated profile of peroxynitrite (0.5 mM) decay by direct reaction with GSH (0.05–10 mM) (solid line) versus homolysis to free radicals (dotted line). (B) Simulated profile of oxygen consumption against GSH concentration. The initial oxygen concentration was 0.217 mM (oxygen solubility at 37 °C). As the concentration of GSH increases, peroxynitrite decay by the direct two-electron oxidation process becomes more significant, instead of its decay through homolysis, which predominates at low GSH concentrations. Computer-assisted kinetic simulations were performed according to the reactions shown in Table 1 with the software Gepasi [161].

iii) Metal centers

Peroxynitrite can also directly oxidize transition metal centers of proteins, particularly heme and non-heme iron, copper and manganese ions, with higher rate constants ranging from ~104 to 107 M−1 s−1. Depending on the transition metal-containing protein, the interactions with peroxynitrite undergo different mechanisms. In the case of heme proteins, peroxynitrite reacting as a one-electron oxidant yields nitrite (NO2−) while reacting through a two-electron process yields •NO2 in addition with the oxidized metal center (Figure 3). In addition, some metal complexes can catalyze the isomerization of peroxynitrite to nitrate (NO3−). In the case of the hemeproteins myeloperoxidase (MPO) and cytochrome P450, the one-electron reaction with peroxynitrite leads to the formation of •NO2 and ferryl-oxo compounds [59,60,61], which are strong secondary oxidizing species that can be reduced by appropriate reductants such as GSH or ascorbic acid, yielding nitrite and regenerating the metal center, or on the other hand they can react with a critical amino acid nearby and lead to a loss of the protein function. For example, the reaction of peroxynitrite with the Cu,Zn and Mn centers of superoxide dismutase yields the oxidant species oxo-copper and oxo-manganese, in addition with •NO2 that potentially lead to metal-catalyzed histidine oxidation and tyrosine nitration, respectively [14,62,63].

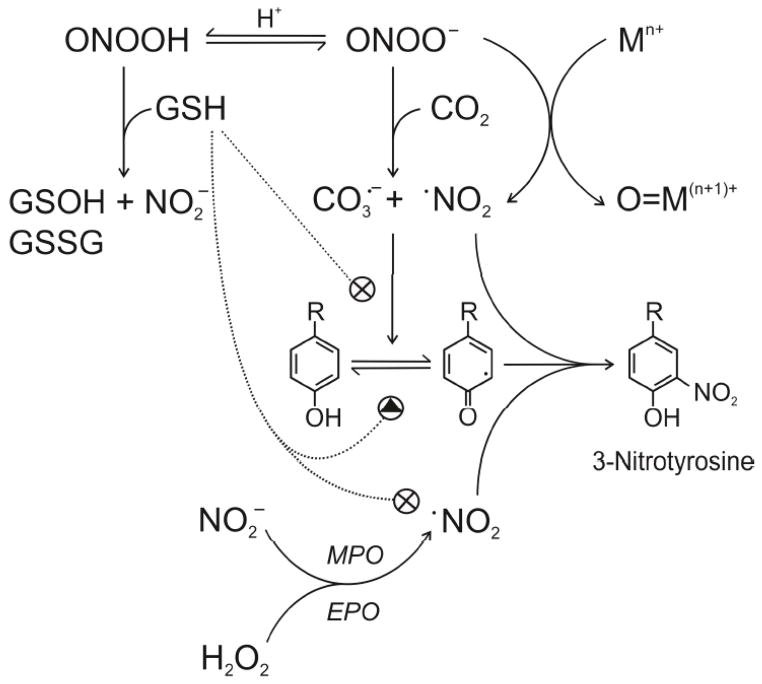

Figure 3. Biochemical mechanisms of peroxynitrite reaction with GSH, CO2 and tyrosine nitration.

Peroxynitrite anion (ONOO•), formed from the diffusion-controlled reaction between •NO and O2•−, is in equilibrium with peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH), which can oxidize glutathione (GSH) to the corresponding sulfenic (GSOH) and disulfide (GSSG) derivatives, yielding also nitrite (NO2−). A fundamental reaction of ONOO• in biological systems is its fast reaction with carbon dioxide (CO2, in equilibrium with physiological levels of bicarbonate anion), which leads to the formation of the one-electron oxidants carbonate (CO3•−) and nitrogen dioxide (•NO2) radicals in ~ 35% yield while the remaining 65% evolves to CO2 and NO3−. Additionally, ONOO• may react with transition metal centers (Mn+), yielding •NO2 and the corresponding oxo-metal complex (O=M(n+1)+). Tyrosine nitration involves the intermediate formation of the tyrosyl-phenoxyl radical (Tyr•) by one-electron oxidation of tyrosine followed by the combination of the phenoxyl radical with •NO2 leading to the formation of 3-nitrotyrosine. Tyr• can be reduced back to tyrosine in the presence of numerous reductants, such as GSH, in competition with the nitration reaction. Additionally, GSH is an excellent scavenger of •NO2. The enzymes myeloperoxidase and eosinophil peroxidase (MPO and EPO, respectively) can promote, in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), the one-electron oxidation of NO2− to •NO2 and participates in a peroxynitrite-independent pathway of tyrosine nitration.

2.2 How to experimentally disclose the preferential reactions of peroxynitrite in living systems

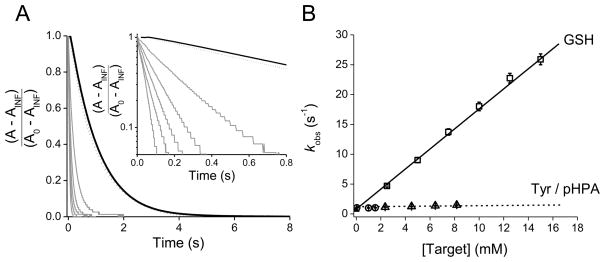

Kinetic studies can enable us to understand and differentiate between the different peroxynitrite-oxidation pathways. For instance, when peroxynitrite reacts directly with a target molecule in an overall second-order process, the reaction mechanism is first order in peroxynitrite and first order in the target so the apparent rate constant of peroxynitrite decomposition increases linearly with target concentration. In order to study the reaction between peroxynitrite and glutathione, the kinetics of peroxynitrite decay can be measured through stopped-flow spectrophotometry at increasing GSH concentrations. As shown in Figure 2, the decay of peroxynitrite at 302 nm followed exponential functions and the observed pseudo-first order rate constants (kobs) increased linearly with GSH concentrations, confirming a direct reaction. From the slope of the plot, the apparent second-order rate constant was determined as (1.65 ± 0.01) × 103 M−1 s−1 at pH 7.35 and 37 °C, similar to the reported value of 1.35 × 103 M−1 s−1 [47,51]. In the other pathway, the target molecule does not react directly with peroxynitrite, but can be modified through species derived from peroxynitrous acid homolysis (•NO2 and •OH). Since the formation of the radicals would be the rate-limiting step (k = 0.9 s−1 at 37 °C), this processes is first order in peroxynitrite and zero order in target. This is the case of the reaction between tyrosine with peroxynitrite, where there is no direct bimolecular reaction, as evidenced form the fact that tyrosine does not increases the rate of peroxynitrite decomposition (Figure 2). Nevertheless, tyrosine can be modified through the intermediate formation of peroxynitrite-derived radicals [64]. It is important to note that plots of the apparent second-order rate constants as a function of pH, as well as oxygen consumption studies and computer-assisted simulation of the reactions involved can also give important information about the reaction mechanisms and product yields.

Figure 2. Kinetics of peroxynitrite reaction with GSH and tyrosine.

(A) Kinetic traces of peroxynitrite decomposition in the presence of glutathione and tyrosine. Peroxynitrite (56 μM) was mixed with phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.35, 0.1 mM DTPA) at 37 °C, alone (black line) and in the presence of 1.5 mM tyrosine (dash line) or in the presence of increasing GSH concentrations (from right to left: 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 and 15 mM, gray lines). Please note that the plot intercept the y-axis at ~ 0.9 s−1, a value corresponding to the peroxynitrite homolysis at 37 °C. Inset: Logarithmic plot of the stopped-flow kinetic traces at 302 nm up to 0.8 s. A is the absorbance at time t, and A0 and AINF are the initial and final values, respectively. (B) The observed rate constants (kobs) determined from the fit of the decay of peroxynitrite at 302 nm to a single exponential function, are shown as a function of target concentrations. In one pathway, peroxynitrite reacts directly with GSH in an overall second-order process (squares). In the other pathway, peroxynitrite first decompose into nitrogen dioxide and hydroxyl radicals, which are the ultimate oxidants, in a process that is zero order in tyrosine (circles). For tyrosine concentrations > 1.5 mM, we utilized the hydrophilic tyrosine analog p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (pHPA) (triangles) due to the limit of solubility of tyrosine in aqueous solution. Each data point represents the mean ± standard deviation of n 7 determinations.

A helpful example to analyze is the case of desferrioxamine, an iron chelating agent capable of inhibiting peroxynitrite-mediated oxidations by mechanisms independent of metal chelation [38,65,66], which has been determined that does not react directly with peroxynitrite, since as was reported previously, did not increase the rate of peroxynitrite decomposition followed at 302 nm by stopped-flow spectrophotometry. The lack of a direct reaction was also supported by the fact that the direct two-electron oxidation of GSH by peroxynitrite was unaffected in the presence of desferrioxamine. Instead, desferrioxamine has been shown to inhibit peroxynitrite-dependent oxidation and nitration by reacting with •NO2 and CO3•− radicals [66]. In fact, in addition to a direct •NO2 scavenging, it has been also reported that desferrioxamine can reduce tyrosyl radical (Tyr•) intermediate and thus inhibits the radical-radical addition step that leads to 3-nitrotyrosine (NT) formation [66,67]. Thus, desferrioxamine can be used to define between the radical and non-radical mechanisms by which peroxynitrite produces oxidative modifications in biochemical systems.

In some cases, molecules that directly react with peroxynitrite (e.g. thiols), can also be oxidized by the radicals derived from peroxynitrite homolysis, •NO2 and •OH. In order to evaluate the incidence of radical species in the oxidative modifications, it is highly recommended the use of radical scavengers that react with peroxynitrite-derived radicals but not directly with peroxynitrite itself. For example, the target molecule can be exposed to peroxynitrite in the presence of mannitol, a known hydroxyl radical scavenger, or to p-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (pHPA), a soluble tyrosine analogue that reacts with both •NO2 and •OH radicals. If mannitol has no effect while pHPA partially protects the target molecule form the oxidative modification, the result will suggest that •NO2 radical may contribute to the observed effect. In addition, EPR spin-trapping can also be used to discriminate between radical and non-radical mechanisms. For instance, the inhibition of products yields in the presence of spin traps can provide evidence for the participation of free radicals in product formation.

In order to rationalize the biological fate of peroxynitrite and its derived radicals, it is necessary to understand the kinetics and characterize the reaction mechanisms with endogenous components. In this regard, in the next sections we review different experimental and computational approaches with illustrative examples taken primarily from our own laboratories, which, in addition to a theoretical analysis, provide information about the biological reactivity of peroxynitrite. The review will also include the analysis the formation of 3-nitrotyrosine in proteins, a key “footprint” of peroxynitrite in vitro and in vivo. Finally, we provide a quantitative estimation of peroxynitrite state-state levels and its modulation in living systems.

3 METHODS TO STUDY THE REACTIVITY OF PEROXYNITRITE

Peroxynitrite is a transient species with a short biological half-life and low steady-state concentration, which makes problematic its direct detection in vivo. Thus, in order to infer the formation of peroxynitrite and its possible fates in biological systems, it is relevant to understand and characterize the kinetics of its reactions with biomolecules. Herein, we briefly summarize different approaches to address the biochemical reactions of peroxynitrite and its derived radicals.

3.1 Stopped-flow rapid mixing

To study the kinetics of peroxynitrite reactions in a time scale of milliseconds, special fast techniques such as stopped-flow spectrophotometry, should be used. Up to date, the rate constant and reaction mechanisms of peroxynitrite reactions with several target biomolecules have been studied through stopped-flow experiments [40,64,68,69]. Two kinds of approaches can be designed: (a) direct studies by following peroxynitrite disappearance using both integral or initial rate approach [8,64]; and (b) indirectly by competition with a reaction of known rate constant.

3.1.1 Direct Measurements

The rate of peroxynitrite decomposition, in the presence or in the absence of the target molecules, can be conveniently followed at 302 nm, where the peroxynitrite anionic form absorbs [8,30]. If the target molecule is a protein, in order to avoid interferences from its absorption, the peroxynitrite decomposition rate can also be determined at 310 nm (ε = 1600 M−1 cm−1) [70]. The usual direct approach is through an integral rate method, under pseudo-first order conditions using 10-fold and increasing concentrations of the target molecule with respect to peroxynitrite. Under these conditions, peroxynitrite decomposition follows an exponential function versus time, and the observed rate constant (kobs) is determined through the fit of the kinetic trace to this function (as shown for example with GSH in Figure 2). The apparent second-order rate constant of the reaction can be obtained from the slope of kobs versus the molecule concentration. In some circumstances it is not possible to achieve pseudo-first order conditions in stopped-flow experiments since the limiting availability of the target molecule does not permit an excess over peroxynitrite concentration and the fact that peroxynitrite concentrations should not be much less than 0.05 mM in order to detect a variation of absorbance ≥ 0.08. In these cases, initial rate kinetic approaches should be more conveniently used with target molecule concentrations similar or lower to those of peroxynitrite. It is recommendable to acquire half of the experimental data points (~200 absorbance measurements) during the initial part of the reaction enough for the fast reaction between peroxynitrite and target molecule to be completed (typically the first 0.2 s), and the other half points should be obtained until more than 99.9 % of the peroxynitrite had decomposed (0.2 – 10 s). The initial slopes (dA/dt) are obtained for the linear decrease in absorbance at 302 nm (0.1 – 0.2 s), and the observed rate constant can be determined as:

| (3) |

where Ao and Af are the initial and final absorbance measurements, as reported previously [14,64]. The second-order rate constant for the reaction can be calculated from the slope of the plot of kobs versus target concentrations. In order to be sure that the initial rates are being measured, it is important to check that the concentration of reagents remains constant (or less than 10 % are consumed) during the time chosen for initial rate measurements. As control, in the absence of the target molecule, the rate constants of peroxynitrite decomposition determined from the initial rate method should compare well with the values determined from the integral rate method.

The reaction of peroxynitrite and the thiol groups of cysteine and bovine serum albumin was the first reaction of peroxynitrite with a biomolecule studied by stopped-flow [8]. Since then many direct reactions of peroxynitrite with different molecules have been addressed kinetically by stopped-flow measurements, with reported rate constants ranging from 102 to 108 M−1 s−1. In addition to follow the peroxinitrite decomposition by the decrease of its absorbance, a fluorimetric approach can also be used. For example, the kinetics of human peroxiredoxin 5 reaction with peroxynitrite has been studied taking advantage of the single tryptophan (Trp84) differential fluorescence emission under the reduced and oxidized forms of the protein [53]. This, has the benefit of being a very sensitive method which allows the measurement of rate constants in the range of ~ 107 M−1 s−1.

3.1.2 Competition approaches

When the reactivity of peroxynitrite with target molecules is too fast to allow determination of the precise rate constants by direct stopped-flow techniques, or if the reaction cannot be monitored directly due to the low sensitivity in the absorbance or fluorescence emission change of the reactants or products, the rate constant can be studied using a simple competition analysis. The competing reactions between a characterized and an unknown reaction can be used to determine the unknown rate constant with peroxynitrite. When reactions with a common reagent yield different products, it can be shown that the ratio of these products will be proportional to the relative rate constants of the reactions [71], as described by the following equations (Eq. 4–5):

| (4) |

| (5) |

Therefore, the ratio of the rate constants can be deduced from the ratio of products formed (Eq. 5). Thus, knowing one of the rate constants in addition to the initial concentration of reactants and the final concentration of at least one product, the value of the second-order rate constant can be obtained. A1 and A2 can be used in 10-fold excess relative to B, thus providing pseudo-first order conditions. In this case, it can be shown that:

| (6) |

where F represents the fraction of P1 formation inhibited in the presence of a competing scavenger [A2]0. Rearranging the equation 6, plots of [F/(1−F)](k1[A1]0) vs. [A2]0 can be drawn to obtain k2 as the slope. Under experimental conditions where no large excess of competitive reactants can be used, the following relationship should be applied (Eq. 7):

| (7) |

When designing the competition experimental proceedings it is advisable to have an estimate of the magnitude of the rate constant and thus choose the competing molecule accordingly. In addition it is important to control that there is no cross-reaction between the product and one of the competing reagents since may alter the results and led to underestimation of the rate constant of interest.

The competition approach has been applied several times in the literature. For example, competition with a synthetic MnIIIPorphyrin constitutes the first antecedent in the study of peroxynitrite reaction with peroxiredoxins [70,72]. MnIIIPorphyrins are rapidly oxidized by peroxynitrite to the O=MnIV derivative at rate constants comparable to those of peroxiredoxins (k = 105 to 107 M−1 s−1, at pH 7.4 and 37 °C) in a process that can be conveniently followed at the Soret band as the decay of absorbance in the 450–470 nm region [73]. Additionally, a heme peroxidase such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP) can be used as a competing target for peroxynitrite, as reported to determine the second-order rate constant of the reaction of thioredoxin peroxidases from S. cerevisiae (Tsa1 and Tsa2) with peroxynitrite [74]. HRP reacts fast with peroxynitrite (k = 1.02 × 106 M−1 s−1, at pH 7.4 and 25 °C) [60] to produce compound I, and its spectral change can be followed at 398 nm. It is important to consider that other heme peroxidases such as MPO are known to react with peroxynitrite at higher rate constants producing compound II and •NO2, and this secondary-reactive species may react with one of the competing reagents. For example, •NO2 is known to react fast with thiols, with second-order rate constants reported in the range of 107 M−1 s−1 [75] and thus lead to misinterpretations of the results.

3.2 Pulse radiolysis

Reactions of radicals with target molecules, or radical-radical reactions most often proceed with rate constants > 107 M−1 s−1, which yields half-lives of the reactions < ms. Since these times are considerably shorter than those detectable by rapid-mixing techniques such as stopped-flow spectrophotometry, pulse radiolysis results the more suitable methodology for the direct observation of radicals (e.g. the peroxynitrite-derived •OH, •NO2 and CO3•−), and determination of their fast kinetic rate constants with target molecules [76].

This technique provides the possibility of generation of one of the reacting species (radicals or radical ions), by exposure of the sample to a short pulse of high-energy radiation, which would initiate chemical processes and can be followed by measuring a physical property of either one of the reacting species or products, such as absorbance as a function of time [77]. In this sense, CO3•− can be generated by radiolysis of N2O-saturated solutions containing bicarbonate (HCO3−)/carbonate (CO32−). It should be noted that the reaction of •OH with bicarbonate has a low rate constant compared with carbonate [78], therefore CO3• formation would be favored in alkaline conditions under which most of this type of experiments are carried out. The reaction of CO3•− with target molecules can be monitored directly following its decay at 600 nm (ε = 1850 M−1 cm−1 M−1 cm−1) [79,80]. For example, the reported rate constant of CO3•− reaction with desferrioxamine was measured by fitting first-order exponential decays of CO3•− in the presence of increasing desferrioxamine concentrations, leading to the formation of desferrioxamine nitroxide radical with a second-order rate constant of 1.7 × 109 M−1 s−1 at pH 7.5 [66]. This rate constant is close to the diffusion-controlled limit, 300 and 40 times higher than the corresponding rate constants of CO3•− with glutathione and tyrosine, respectively [81]. The data with desferrioxamine support that in biochemical systems it can inhibit peroxynitrite-mediated oxidative processes by direct scavenging of its derived radicals. When the participating species (radicals or the target molecules) cannot be detected directly by spectrophotometry, the reaction can be monitored using a reporter molecule with an intense absorption spectrum. This reference compound can be used as a competing agent for the determination of the rate constant of a radical with the target molecule. For example, the kinetics of the reaction between •NO2 and GSH, with a reported rate constant of 2 × 107 M−1 s−1 at pH 7.4, was determined using (2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS2−) as a competing compound, whose oxidation leads to the formation of the intense chromophore ABTS•− (ε645nm = 13400 M−1 cm−1) [75].

3.3 Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR)

EPR spectroscopy is a widely used methodology to detect and identify free radicals, with the possibility to unravel oxidative mechanisms, and also to discriminate radical from non-radical mechanisms [82,83]. In addition, in combination with analytical methods allows identify the protein residues that are the target of oxidants. Relevantly, by the use of direct EPR during continuous flow of peroxynitrite to carbonated phosphate buffers, it was unequivocally demonstrated the formation of CO3•− [42]. Since only a few radicals or protein-radicals have been shown to be stable enough to be detectable by direct EPR under aerobic conditions at room temperature, most EPR studies have been performed by rapid freeze-quench EPR and by EPR spin-trapping [83,84]. The spin-trapping approach has been extensively used to study peroxynitrite decomposition pathways and characterize the reactions of its derived radicals with target molecules. For example, the formation of •OH can be detected using the spin trap DMPO (5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide) [31], a cell permeable hydrophilic nitrone, that yield a more stable spin trap-OH adduct [85]. DMPO has also been shown to react with thiyl radicals (e.g. with Cys• and GS•) [46] and with CO3•− [86]; the formation of CO3•− by peroxynitrite in a cellular system consisting of activated/immuno-stimulated macrophages was confirmed by EPR spin trapping [86]. If peroxynitrite-derived radicals react with a protein and generate a protein radical, the EPR signal of the protein-spin trap adduct looks as a broad spectrum, characteristic of relatively immobilized nitroxide. For example, in the study of the copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (Cu,ZnSOD) inactivation by peroxynitrite, the addition of the nitroso spin trap 2-methyl-2-nitrosopropane (MNP) led to the EPR detection of an anisotropic signal typical of an immobilized protein radical adduct. Partial proteolysis by treatment with pronase, which increases the rotational dynamics of free radical adduct and improve its detection, revealed a nearly isotropic signal consistent with the formation of a histidinyl radical in the active site of the enzyme [62]. It must be taken into account that a major problem with several spin traps in biological systems is that the spin adduct (nitroxide derivative) can be oxidized to a nitrone derivative or can also be reduced to the corresponding hydroxylamine, thus decreasing its half-life and precluding EPR detection. Immunospintrapping is a novel alternative based on the association of spin trapping with immunochemical detection. Interestingly, protein Tyr• formation in cells and tissues undergoing nitroxidative stress can be detected using polyclonal antibodies that bind to protein nitrone adduct of the spin trap DMPO [87,88,89,90]. This method has also been applied for western blotting and immunochemistry in vitro and in vivo to assist in the identification of peroxynitrite as a mediator of protein oxidative damage [91].

4. PEROXYNITRITE FOOTPRINTS

4.1 Protein tyrosine nitration

Peroxynitrite promotes oxidative modifications in target biomolecules such as DNA, lipids and proteins and most notably, leads to several modifications in protein amino acids. Herein we will focus on protein tyrosine nitration mediated by peroxynitrite and derived-oxidants [92,93]. Protein tyrosine nitration is a post-translational modification mediated by nitric oxide-derived oxidants such peroxynitrite and represents the substitution of hydrogen by a nitro group (−NO2) in the position 3 of the phenolic ring, yielding 3-nitrotyrosine (NT). Important work performed by Sokolovsky and co-workers in the early sixties demonstrated that tyrosine nitration mediated by nitrating agents such as tetranitromethane (TNM) resulted in dramatic changes either in function and structure of isolated proteins [94]. More recent data confirmed that protein tyrosine nitration leads to functional alterations in a variety or proteins in vivo [95]. Indeed, the biological relevance of protein tyrosine nitration was definitely established in the early nineties, after the recognition of nitric oxide-derived oxidants formation, and the implication of these free radical species in several pathophysiological conditions [7,8,38,96].

Beckman and co-workers, demonstrated for the first time the presence of NT in atherosclerotic plaques of samples from coronary arteries of patients with cardiovascular disease confirming that nitric oxide-derived oxidants, such as peroxynitrite are formed during human atherosclerosis, and may be responsible for the pathogenesis [97]. The detection of NT was made immunochemically using anti-protein 3-nitrotyrosine antibodies, a sensitive method that was improved and extensively used afterwards [98]. In addition, bioanalytical methods have been developed for quantitation of NT levels and have been reviewed recently elsewhere [99].

The increased levels of NT respect the basal levels in normal conditions, have been considered a footprint of nitro-oxidative damage in vivo, being revealed as a strong biomarker and predictor of disease onset and progression [100]. Indeed, protein tyrosine nitration has been established both in vivo and animal models in several diseases such as cardiovascular disease, atherosclerosis, ischemia-reperfusion, and stroke [101,102,103,104]; in neurodegenerative processes such as Parkinson and Alzheimer [105,106,107,108] diabetes and inflammation among others [105,106].

Herein, we will analyze the biochemistry of tyrosine nitration reactions that take place by the action of peroxynitrite and hemeperoxidases, and the physicochemical factors that can modulate these pathways under biological conditions.

Though initially the formation of NT was considered a footprint of peroxynitrite formation, now we know that tyrosine nitration can occur biologically by a variety of routes, mainly, dependent on peroxynitrite and hemeperoxidases such as MPO 3 or eosinophil peroxidase (EPO), however both mechanisms are based in free radical chemistry (Figure 3) (i.e. there is no direct reaction of tyrosine with peroxynitrite [64,109], Figure 2).

The formation of NT requires the intermediate formation of the transient tyrosyl radical (•Tyr) followed by the diffusion-controlled reaction with •NO2. The one-electron oxidation of tyrosine to •Tyr can be achieved by a number of oxidants such as the peroxynitrite-derived radicals •NO2 (k = 3.2 × 105 M−1 s−1, pH 7.5) [110], •OH (k = 1.3 × 1010 M−1 s−1) [111] and CO3•−, (k = 4.5 × 107 M−1 s−1 ) [81] and the myeloperoxidase-derived compounds I (k = 2.93 × 104 M−1 s−1) [112] or II (k = 1.57 × 104 M−1 s−1) [113].

More recently we have demonstrated that lipid-derived alkoxyl model radicals (LO•) (k = 5×105 M−1 s−1) [114] and peroxyl (LOO•) (k = 4.5 × 103 M−1 s−1) [115] radicals can also promote the one-electron oxidation of tyrosine to •Tyr. This has particular relevance in membranes and lipoproteins, where an important amount of unsaturated fatty acids undergo lipid peroxidation reactions. Peroxynitrite-derived radicals (i.e. •OH) are able to promote the abstraction of hydrogen from an unsaturated fatty acid, in the initial reaction of the lipid peroxidation chain. Once lipid peroxyl radicals are formed, nitration pathways may be fueled in membranes by the oxidation of tyrosine, in a connection reaction between tyrosine nitration and lipid peroxidation defined recently [114,115].

In addition to NT, other products can be formed from •Tyr. 3,3′-dityrosine is formed by the combination of two tyrosyl radicals, or the hydroxylated derivative, 3,4-dihidroxyphenylalanine, (DOPA) by the addition of •OH, [35] and tyrosine hydroperoxide by addition of O2•− [116]. Finally, the reaction between •Tyr and •NO yields 3-nitroso tyrosine, which in the presence of further oxidation reactions can evolve to the intermediate formation of iminoxyl radical and then NT as a final product [92].

Depending on the products that are formed, MPO and peroxynitrite routes could be discriminated. The colocalization of 3-hydroxytyrosine and NT was once considered to be a useful tool to discriminate between peroxynitrite and other nitrating species [117], but it was later on discovered that 3-hydroxytyrosine formation can be also accomplished by hemeperoxidase-dependent reactions [118]. On the other hand, the concomitant presence of 3-chloro or 3-bromotyrosine with NT is indicative of the participation of MPO and EPO, respectively in the nitration process [92,119], which can further complemented by immunochemical detection of the hemeperoxidases.

In addition, peroxynitrite-mediated nitration pathways in cells and animals can be disclosed genetically or pharmacologically by the overexpression of enzymes that catalytically decompose peroxynitrite and O2•− such as peroxiredoxins and SOD (promoting its detoxification), or by using knock-outs of particular enzymes (i.e. MPO). Indeed, in important work by Brennan and coworkers in MPO knock out mice, revealed that NT formation in acute inflammation models is largely MPO-dependent [119], consistent with the influx and degranulation of activated neutrophils in the inflammatory sites. MPO-mediated nitration pathways can be further distinguished, by using specific MPO- inhibitors [120] such as alkyl indole derivatives [121].

4.2 Factors that influence protein tyrosine nitration yields and selectivity: the inhibitory effect of glutathione

Protein tyrosine nitration is found in basal levels in normal tissues or cells, however yields are low, mainly due to competing reactions which may consume the nitrating agents (e.g. glutathione readily consumes •NO2), the action of several enzymes which attenuate oxidant formation (i.e. peroxiredoxins and SOD) or by the repair of •Tyr, either by reductants such as glutathione or ascorbic acid, or by intramolecular electron transfer processes [122,123] (Figure 3). In spite of these considerations, some proteins are preferentially nitrated. Several physicochemical factors control the selectivity of protein tyrosine nitration such as protein abundance and structure, the nitration mechanism and the environment where the tyrosine residue is located [35]. It is clear that within a protein, not all tyrosine residues become nitrated and is not easy to predict which are the conditions required for the preferential reaction. Mapping the nitration sites within a protein may assist to understand the nitration mechanism, and disclose the action of different oxidants [93]. A notable example of this contention, is the case of MnSOD, a critical mitochondrial enzyme, where the Mn-catalyzed nitration of one particular tyrosine residue (out of a total of nine tyrosine residues) by peroxynitrite (Tyr 34) [14] is responsible of its inactivation [63,124]. This site-specificity is indicative of peroxynitrite formation in mitochondria and can be used to discriminate from other nitrating agents [93]. Moreover, it has been recently demonstrated that peroxynitrite promotes tyrosine nitration of up to five (of 24) tyrosine residues in Hsp90; interestingly, among those residues, nitration of a single tyrosine (either Tyr 33 or Tyr 56) on Hsp90 is sufficient to induce motor neuron cell death [125].

Several endogenous agents can modulate protein tyrosine nitration in vivo, and in this sense the role of GSH will be analyzed (Fig. 3). Glutathione, present at intracellular mM levels, is a strong endogenous inhibitor or protein tyrosine nitration. However, the mechanism of inhibition deserves a subtle analysis. First, glutathione reacts directly with peroxynitrite, but this reaction is not very fast (k = 1.35 × 103 M−1 s−1), constituting a modest route of decay biologically (vide infra). Relevantly, GSH is an important scavenger of •NO2 (k = 2 × 107 M−1 s−1), probably being the most relevant reaction in vivo for the inhibition of tyrosine nitration [75]. In addition, GSH also readily reacts with CO3•− and other one-electron oxidants and it can also reduce •Tyr back to tyrosine, as additional contributory mechanisms. By pulse radiolysis experiments, we were able to measure a rate constant for the reaction between •Tyr and GSH (k = 2 × 106 M−1 s−1) [122], however this repair reaction is close to equilibrium (repair equilibrium constant ~ 1), and consequently, an efficient reduction of •Tyr by GSH requires the removal of thiyl radicals, to allow the repair reaction (in cells, other reductants, such as ascorbic acid repair •Tyr radicals faster than GSH [122]). Computer assisted simulations [126] indicate that mM glutathione concentrations inhibit peroxynitrite-dependent tyrosine nitration yields by several orders of magnitude [126]. In spite of this restriction, it was found that for a given GSH concentration, NT levels correlate well with increased peroxynitrite formation rates.

Protein tyrosine nitration would be promoted in compartments where glutathione is scarce (e.g. extracellular), or under conditions of decreased GSH concentrations arising in pathological situations associated with oxidative stress [127]. The critical role of GSH in modulating peroxynitrite reactivity can be evidenced in GSH-depleted cells by treatment with buthionine sulfoximine, which has been shown to increase the detection of intracellular nitration [128,129,130]. In addition, cultured astrocytes and neurons depleted of GSH have enhanced cell susceptibility to peroxynitrite-mediated damage and tyrosine nitration possibly contributing to the development of neurodegenerative diseases such as amyothrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Parkinson’s disease [128,129,130].

5. MODULATION OF THE STEADY STATE CONCENTRATION OF PEROXYNITRITE

The steady state concentration of peroxynitrite in biological compartments is low due to its rapid decay via a variety of processes; these include the reaction with CO2, one- and two-electron oxidations, isomerization and homolysis.

The overall equation rate is given by:

| (8) |

where kf represents the rate constant of peroxynitrite formation, and kH and kT the rate constants of peroxynitrite decay by homolysis or by reaction with target molecules, respectively. The term kT[T] represents the overall rate of peroxynitrite reaction with different cellular components, which is determined by the product of a “global” rate constant and target(s) concentration, and can be used to parameterize and compare theoretically the reactivity in a homogeneous system. Formally, kT[T] is better expressed by:

| (9) |

In the steady state condition:

Then,

| (10) |

Since the proton-catalyzed homolysis of peroxynitrite represents a very minor route of peroxynitrite disappearance (kH[ONOO−] = 0.9 s−1), we can assume that kH ≪ kT[T], thus:

| (11) |

As an example, we can study the situation in the cytosol, where changes in concentration of key endogenous modulators such as CO2, peroxiredoxins, other thiol proteins and some hemeproteins, will significantly modify the rate of peroxynitrite disappearance and thus its steady state concentration. For instance, knowing the bimolecular rate constant values (k) of the different reactions and the concentration of targets ([T]) in the cytosolic compartment, we can estimate a value of k[T] ~ 330 s−14. Considering the intracellular steady-state values of [•NO]ss and [O2•−]ss reported for endothelial cells, a peroxynitrite formation flux under basal metabolic conditions can be estimated as 0.3 μM s−1 and the biological steady state of peroxynitrite would be ~ 1 nM [21,22,23]. Recently, a kinetic model that included the effects of multiple cellular targets estimated an intracellular steady state concentration of peroxynitrite within the same range [21,23].

For a constant value of peroxynitrite formation rates, the increase or decrease in the kT[T] term of the Eq. 11, will significantly impact on the [ONOO−]ss. In general, endogenous compounds that would influence the [ONOO−]ss should result in kT[T] ≥ 60 s−1 (higher than that of CO2) to have a significant effect. For example, doubling Prx 5 concentration from 1 to 2 μM, represents a kT[T] value of ~280 s−1, which would imply a decrease in the steady-state peroxynitrite concentration to 0.6 nM. Considering certain cell types such as erythrocytes where Prx 2 is also very concentrated (240 μM), with a rate constant of 1.7 × 107 M−1 s−1 at pH 7.4 and 25 °C [131], a kT[T] > 4000 s−1 implies that [ONOO−]ss falls to 36 pM at 37 °C [21]. Oxyhemoglobin, which also has a kT[T] value larger than that of CO2, (340 s−1, from k = 1.7 × 104 M−1 s−1 at pH 7.4, 37 °C and concentration of 20 mM, [90]) will significantly drop the [ONOO−]ss, but its potential activity as a peroxynitrite scavenger, catalyzing its isomerization to nitrite, is restricted by its location in the red blood cells. An interesting lesson learned during the accumulation of kinetic data on peroxynitrite biochemistry, was the modification of an initial idea pointing oxy-hemoglobin as the main peroxynitrite “sink” in the erythrocyte [28]. Indeed, in spite of the high kT[T] value for oxy-hemoglobin, it was more recently found that the Prx 2 reaction is much faster, and the principal decay mechanism of peroxynitrite in red blood cell (340 s−1 vs > 4000 s−1, respectively).

On the other hand, there are a series of endogenous molecules that modulate the biological chemistry of peroxynitrite but that do not significantly alter the kT[T] term of the equation. For example, GSH has a kT[T] value of 7 s−1 (at 37 °C and pH 7.4), representing a minor fraction of peroxynitrite reduction. Thus, even doubling the concentration, GSH is not able to outcompete other targets such as CO2 or Prx and will not directly affect much the [ONOO−]ss. In addition, other low molecular antioxidants, such as ascorbate and uric acid present in cell systems at concentrations of 0.5 and 0.1 mM, respectively, react relatively slowly with peroxynitrite (k ~ 102 M−1 s−1) [132,133], with kT[T] <0.1 s−1. Therefore, GSH and other low molecular weight antioxidants by themselves appear to be inefficient direct peroxynitrite scavengers, although their role on the modulation of peroxynitrite reactivity is increasingly attributed in the scavenging of its secondary-derived radicals, in the repair reactions or in the recycling of appropriate scavengers. For example, most of the protective effects of uric acid against peroxynitrite-mediated toxicity in vitro and in vivo have been attributed to the scavenging of peroxynitrite-derived radicals and the inhibition of tyrosine nitration reactions [133,134,135]. In fact, uric acid reacts fast with •OH and •NO2, with rate constants of 1.0 × 109 M−1 s−1 and 1.8 × 107 M−1 s−1, respectively [136,137] and with CO3•− it has been estimated a value of 2.9 × 108 M−1 s−1 [50].

These general concepts also apply for the pharmacological modulation of the [ONOO−]ss, for example using the synthetic peroxynitrite scavengers metal porphyrins and selenols. Manganese porphyrins (MnPorphyrins), initially conceived as superoxide dismutase-mimics, can readily react with peroxynitrite in the Mn+2 and Mn+3 states to yield nitrite or •NO2, respectively [69,138]. The one-electron oxidation of Mn+3 implies the formation of two strong oxidants manganese (IV) complexes and •NO2, which represents a potentially damaging mechanism. Although MnPorphyrins are typically administered in the +3 state, they can be reduced in vivo by low-molecular weight reductants (glutathione or ascorbate), or enzymatically by a number of flavoenzymes including the electron transport chain complexes, even under physiological oxygen tensions [139,140]. Then Mn+2Porphyrins reduce peroxynitrite anion to nitrite (rate constants ≥ 107 M−1 s−1) in a two-electron oxidation process [141]. Through these mechanisms, MnPorphyrins can catalytically decompose peroxynitrite at the expense of endogenous reducing equivalents and avoids the formation of •NO2. Even though the uptake and subcellular distribution of MnPorphyrins are poorly characterized, they can accumulate to micromolar levels in mitochondria. For example, recent reports indicate that one particular cationic MnPorphyrin can accumulate in mouse heart mitochondria in a concentration of 5.1 μM, 7 h after a single i.p administration at 10 mg kg−1 [21,142]. Thus, a kT[T] value ≥ 51 s−1 would be significant to lower the [ONOO−]ss and site-specifically protect mitochondria from peroxynitrite-mediated damage. Similar considerations may be apply to the synthetic compound ebselen [2-phenyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3-(2H)one], a lipid soluble selenium compound that exhibits glutathione peroxidase-like activity, which reduce peroxynitrite by two-electrons with a significant rate constant of 2 × 106 M−1 s−1[143]. Experimental models after drug administration have determined ebselen plasma concentrations in the range of 5–10 μM, which represents a kT[T] value ~ 10–20 s−1 and could account for the reported protective effects of ebselen in several models of inflammation and reperfusion injury mediated by peroxynitrite [21,144,145,146]. Other organo selenium compounds were also reported to react with peroxynitrite. For instance, diphenyl diselenide (PhSe) protected endothelial cells from peroxynitrite-dependent apoptosis and protein tyrosine nitration [147]5.

There are other synthetic compounds with potential pharmacological applications that not react directly with peroxynitrite. Therefore they do not affect [ONOO−]ss and their protective actions have been attributed to their capacity to scavenge peroxynitrite-derived radicals. For example, tyrosine-containing peptides have been proven to inhibit apoptosis and NT formation in motor neuron cultures exposed to exogenous and endogenous peroxynitrite [149,150]. Other compounds, such as the membrane-permeable nitroxide radical tempol (4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6,tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy), desferrioxamine, mitochondrial-targeted ubiquinol, may also exert part of their antioxidant and cytoprotective effects via scavenging of peroxynitrite-derived radicals [66,151,152].

Under conditions of excess peroxynitrite formation, another alternative is to lower [ONOO−]ss by the decrease of the formation rates k [•NO][O2•−]. This could be accomplished by decreasing •NO and O2•− levels either by inhibiting their formation (e.g. by NOS and NADPH inhibitors [153,154,155], or by enhancing their consumption, for example using •NO scavengers such as phenyl-4,4,5,5,-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl 3-oxide (PTIO) [156], or enhancing O2•− elimination via supplementation with cell-permeable SOD mimics or by overexpression of cytosolic or mitochondrial SOD [157,158,159].

On an opposite scenario, the cytotoxic properties of peroxynitrite can also be used by the immune system to combat microbial invasion [21]. For example, it has been demonstrated that internalization of T. cruzi by immunostimulated macrophages triggers the assembly of the NADPH oxidase complex and together with iNOS-derived •NO, generates intraphagosomal peroxynitrite levels, which mediate microbial killing [160]. Importantly, peroxynitrite-mediated killing in T. cruzi is neutralized in parasite strains containing high peroxiredoxin levels, which readily cope with peroxynitrite. Thus, in some stage of infection processes it may be timely to promote peroxynitrite formation (or decrease its decay) in order to increase [ONOO−]ss as cytotoxic effector.

Therefore, the kinetic analysis provided in this section and summarized in eq. 11 provides a conceptual and quantitative handle to better predict the preferential fate and steady-state levels of peroxynitrite in living systems.

Highlights.

Peroxynitrite is a reactive biological oxidant

Kinetic and mechanistic considerations predict the preferential reactions of peroxynitrite

Carbon dioxide participates in peroxynitrite decay and oxidations

Peroxiredoxins represent efficient thiol-based peroxynitrite detoxification systems

Conceivable biological steady-state concentrations of peroxynitrite are estimated

Acknowledgments

The authors received support from Universidad de la República, Programa de Desarrollo Ciencias Básicas (PEDECIBA) and Agencia Nacional de Investigación e Innovación (ANII). The work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1AI095173), Comisión Sectorial de Investigación Científica (CSIC, Universidad de la República), and ANII (Fondo Clemente Estable, FCE_2486) to RR and ANII (Fondo Clemente Estable, FCE_6605) to SB. We thank Dr. Beatriz Alvarez (Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de la República, Uruguay) for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- ABTS2−

2,2′-azinobis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)

- DTPA

diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid

- DMPO

5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- EPO

eosinophil peroxidase

- NT

3-nitrotyrosine

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- SOD

superoxide dismutases

- GSH

glutathione

- Prx

peroxiredoxins

Footnotes

The term peroxynitrite is used to refer to the sum of peroxynitrite anion (ONOO−) and peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH). IUPAC recommended names are oxoperoxonitrate (1−) and hydrogen oxoperoxonitrate, respectively.

Peroxynitrous acid can cross biological membranes through the lipid bilayer by passive diffusion, whereas the anionic form can penetrate cells through anion channels [27, 28]. Despite the short biological half-life of peroxynitrite at physiological pH (~10 ms, [28]), due to a multiplicity of reactions with biotargets, the ability to cross cell membranes implies that peroxynitrite generated by a cellular source could influence surrounding target cells within one or two cell diameters (~ 5–10 μm) [29]. In fact, considering the peroxynitrite targets in different compartments, it has been estimated that it can traverse a mean distance of 0.5, 3 and 5.5 μm in erythrocytes, mitochondria and blood plasma, respectively, during one half-life [21].

In the case of MPO-catalyzed nitration, the enzyme reacts with hydrogen peroxide, yielding compound I, which in turn can oxidize nitrite (NO2−) to •NO2, and tyrosine to •Tyr radical (Figure 3), and then NT can be formed. Kinetic data indicate that nitrite is oxidized faster than tyrosine by compound I and tyrosine is oxidized faster by compound II [111].

Apparent rate constant for the reaction between peroxynitrite and cytosolic targets at pH 7.4 and 37 °C. Concentrations and rate constants were assumed, respectively: carbon dioxide: 1.3 mM, k = 4.6 × 104 M−1 s−1 (60 s−1); Peroxiredoxin 5: 1 μM, k = 7 × 107 M−1 s−1 at 25 °C assuming twice at 37 °C (140 s−1); glutathione: 5 mM, k = 1.35 × 103 M−1 s−1 (7 s−1); other proteins: 15 mM, k = 5 × 103 M−1 s−1 (75 s−1); metal and selenium-containing proteins: 0.5 mM, k = 1 × 105 M−1 s−1 (50 s−1) [107].

Kinetic considerations are essential to develop and test novel probes for peroxynitrite detection in biological systems. In particular, boronate-based compounds readily react with peroxynitrite (k > 106 M−1 s−1) and are being successfully used for its detection and quantitation [148].

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Szabo C, Ischiropoulos H, Radi R. Peroxynitrite: biochemistry, pathophysiology and development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:662–680. doi: 10.1038/nrd2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ignarro LJ. Endothelium-derived nitric oxide: actions and properties. FASEB J. 1989;3:31–36. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.1.2642868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ignarro LJ. Biosynthesis and metabolism of endothelium-derived nitric oxide. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1990;30:535–560. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.30.040190.002535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moncada S, Palmer RM, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu X, Miller MJ, Joshi MS, Sadowska-Krowicka H, Clark DA, Lancaster JR., Jr Diffusion-limited reaction of free nitric oxide with erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18709–18713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsoukias NM, Kavdia M, Popel AS. A theoretical model of nitric oxide transport in arterioles: frequency- vs. amplitude-dependent control of cGMP formation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1043–1056. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00525.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, Marshall PA, Freeman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radi R, Beckman JS, Bush KM, Freeman BA. Peroxynitrite oxidation of sulfhydryls. The cytotoxic potential of superoxide and nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4244–4250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fielden EM, Roberts PB, Bray RC, Lowe DJ, Mautner GN, Rotilio G, Calabrese L. Mechanism of action of superoxide dismutase from pulse radiolysis and electron paramagnetic resonance. Evidence that only half the active sites function in catalysis. Biochem J. 1974;139:49–60. doi: 10.1042/bj1390049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu JL, Hsieh Y, Tu C, O’Connor D, Nick HS, Silverman DN. Catalytic properties of human manganese superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17687–17691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klug-Roth D, Fridovich I, Rabani J. Pulse radiolytic investigations of superoxide catalyzed disproportionation. Mechanism for bovine superoxide dismutase. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:2786–2790. doi: 10.1021/ja00790a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halliwell B, Gutteridge J. Free radicals in Biology and medicine. Oxford; 1999. Antioxidant Defences. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang LY, Slot JW, Geuze HJ, Crapo JD. Molecular immunocytochemistry of the CuZn superoxide dismutase in rat hepatocytes. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:2169–2179. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quijano C, Hernandez-Saavedra D, Castro L, McCord JM, Freeman BA, Radi R. Reaction of peroxynitrite with Mn-superoxide dismutase. Role of the metal center in decomposition kinetics and nitration. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11631–11638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gryglewski RJ, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Superoxide anion is involved in the breakdown of endothelium-derived vascular relaxing factor. Nature. 1986;320:454–456. doi: 10.1038/320454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubanyi GM, Vanhoutte PM. Superoxide anions and hyperoxia inactivate endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:H822–827. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.250.5.H822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein S, Czapski G. The reaction of NO. with O2.- and HO2.: a pulse radiolysis study. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19:505–510. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00034-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huie RE, Padmaja S. The reaction of no with superoxide. Free Radic Res Commun. 1993;18:195–199. doi: 10.3109/10715769309145868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kissner R, Nauser T, Bugnon P, Lye PG, Koppenol WH. Formation and properties of peroxynitrite as studied by laser flash photolysis, high-pressure stopped-flow technique, and pulse radiolysis. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:1285–1292. doi: 10.1021/tx970160x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Botti H, Moller MN, Steinmann D, Nauser T, Koppenol WH, Denicola A, Radi R. Distance-dependent diffusion-controlled reaction of •NO and O2•− at chemical equilibrium with ONOO. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:16584–16593. doi: 10.1021/jp105606b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrer-Sueta G, Radi R. Chemical biology of peroxynitrite: kinetics, diffusion, and radicals. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:161–177. doi: 10.1021/cb800279q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quijano C, Castro L, Peluffo G, Valez V, Radi R. Enhanced mitochondrial superoxide in hyperglycemic endothelial cells: direct measurements and formation of hydrogen peroxide and peroxynitrite. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3404–3414. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00761.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim CH, Dedon PC, Deen WM. Kinetic analysis of intracellular concentrations of reactive nitrogen species. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:2134–2147. doi: 10.1021/tx800213b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alvarez MN, Trujillo M, Radi R. Peroxynitrite formation from biochemical and cellular fluxes of nitric oxide and superoxide. Methods Enzymol. 2002;359:353–366. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)59198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koppenol WH, Kissner R. Can O=NOOH undergo homolysis? Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:87–90. doi: 10.1021/tx970200x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merenyi G, Lind J. Free radical formation in the peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH)/peroxynitrite (ONOO-) system. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:243–246. doi: 10.1021/tx980026s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marla SS, Lee J, Groves JT. Peroxynitrite rapidly permeates phospholipid membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14243–14248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denicola A, Souza JM, Radi R. Diffusion of peroxynitrite across erythrocyte membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3566–3571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romero N, Denicola A, Souza JM, Radi R. Diffusion of peroxynitrite in the presence of carbon dioxide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;368:23–30. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes MN, Nicklin HG. The chemistry of pernitrites. Part I. Kinetics of decomposition of pernitrous acid. J Chem Soc A. 1968:450–456. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Augusto O, Gatti RM, Radi R. Spin-trapping studies of peroxynitrite decomposition and of 3- morpholinosydnonimine N-ethylcarbamide autooxidation: direct evidence for metal-independent formation of free radical intermediates. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;310:118–125. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerasimov OV, Lymar SV. The Yield of Hydroxyl Radical from the Decomposition of Peroxynitrous Acid. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:4317–4321. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldstein S, Czapski G. Direct and Indirect Oxidations by Peroxynitrite. Inorg Chem. 1995;34:4041–4048. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radi R. Peroxynitrite reactions and diffusion in biology. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:720–721. doi: 10.1021/tx980096z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartesaghi S, Ferrer-Sueta G, Peluffo G, Valez V, Zhang H, Kalyanaraman B, Radi R. Protein tyrosine nitration in hydrophilic and hydrophobic environments. Amino Acids. 2007;32:501–515. doi: 10.1007/s00726-006-0425-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartesaghi S, Valez V, Trujillo M, Peluffo G, Romero N, Zhang H, Kalyanaraman B, Radi R. Mechanistic Studies of Peroxynitrite-Mediated Tyrosine Nitration in Membranes Using the Hydrophobic Probe N-t-BOC-L-tyrosine tert-Butyl Ester. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6813–6825. doi: 10.1021/bi060363x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Donnell VB, Eiserich JP, Bloodsworth A, Chumley PH, Kirk M, Barnes S, Darley-Usmar VM, Freeman BA. Nitration of unsaturated fatty acids by nitric oxide-derived reactive species. Methods Enzymol. 1999;301:454–470. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)01109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radi R, Beckman JS, Bush KM, Freeman BA. Peroxynitrite-induced membrane lipid peroxidation: the cytotoxic potential of superoxide and nitric oxide. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;288:481–487. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubbo H, Trostchansky A, O’Donnell VB. Peroxynitrite-mediated lipid oxidation and nitration: mechanisms and consequences. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;484:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radi R, Denicola A, Alvarez B, Ferrer G, Rubbo H. The Biological Chemistry of Peroxynitrite. In: Ignarro LJ, editor. Nitric Oxide Biology and Pathobiology. Academic Press; San Diego: 2000. pp. 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trujillo M, Alvarez B, Souza JM, Romero N, Castro L, Thomson L, Radi R. Mechanisms and Biological Consequences of Peroxynitrite-Dependent Protein Oxidation and Nitration. In: Ignarro JL, editor. Nitric Oxide Biology and Pathobiology. Academic Press; San Diego: 2010. pp. 61–102. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonini MG, Radi R, Ferrer-Sueta G, Ferreira AM, Augusto O. Direct EPR detection of the carbonate radical anion produced from peroxynitrite and carbon dioxide. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10802–10806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Denicola A, Freeman BA, Trujillo M, Radi R. Peroxynitrite reaction with carbon dioxide/bicarbonate: kinetics and influence on peroxynitrite-mediated oxidations. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;333:49–58. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldstein S, Czapski G. The Effect of Bicarbonate on Oxidation by Peroxynitrite: Implication for Its Biological Activity. Inorg Chem. 1997;36:5113–5117. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lymar SV, Hurst JK. CO2-Catalyzed one-electron oxidations by peroxynitrite: Properties of the reactive intermediate. Inorg Chem. 1998;37:294–301. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonini MG, Augusto O. Carbon dioxide stimulates the production of thiyl, sulfinil and disulfide radical anion from tiol oxidation by peroxynitrite. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9749–9754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008456200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]