Abstract

Sponges are probably the earliest branching animals, and their fossil record dates back to the Precambrian. Identifying their skeletal structure and composition is thus a crucial step in improving our understanding of the early evolution of metazoans. Here, we present the discovery of 505–million-year-old chitin, found in exceptionally well preserved Vauxia gracilenta sponges from the Middle Cambrian Burgess Shale. Our new findings indicate that, given the right fossilization conditions, chitin is stable for much longer than previously suspected. The preservation of chitin in these fossils opens new avenues for research into other ancient fossil groups.

Chitin (C8H13O5N)n is a chain polymer of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, which is one of the most chemically and thermally stable derivatives of glucose. This structural aminopolysaccharide is the main component of the cell walls of fungi, the exoskeletons of insects and arthropods (e.g., lobsters, crabs, and shrimps), the radulas of molluscs, and the beaks of cephalopods (including squid and octopuses). Until recently, the oldest preserved chitin dates to the Oligocene (25,0 ± 0,5 Ma)1 and to the Late Eocene (34–36 Ma)2. Despite reports of exceptional fossil preservation in the middle Cambrian Kaili Formation, Guizhou Province, China via carbonaceous films3, or fossilized fungal hyphae and spores from the Ordovician of Wisconsin (with an age of about 460 million years)4, there is dearth of information about chitin identification in these studies. The oldest chitin-protein molecular signatures were found in a Pennsylvanian (310 Ma) scorpion cuticule and Silurian (417 Ma) eurepterid cuticle by Cody and co-workers5.

Recent work has demonstrated that chitin also occurs within skeletons of recent marine (e.g. hexactinellid Farrea occa6 and “keratose” Verongida7,8,9) as well as freshwater10 sponges. Sponges (Porifera) probably include the earliest branching extant animal groups11 and their fossil record dates back to the Ediacaran12,13. Biomarkers14 suggest an even older origin (>1 billion years), although it is still unknown which sponges form the earliest-branching group, since the fossil record of these “keratose” sponges is poor due to the absence of mineralised spicules. The Vauxiidae15 are among the best-known taxa in the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale in British Columbia, Canada, although their interpretation remains controversial16. Vauxidae sponges exhibit an apparently reticulate, aspiculate fibrous skeleton. Assuming an aspiculate organic skeleton, Rigby16 suggested an affiliation with the modern “Keratosa”; particularly the Verongida. Although this view has been widely adopted, the nature of “Keratosa” and these relationships have not been fully resolved.

The object of the current study was to test the hypothesis that chitin was an essential skeletal component of early sponges assigned to Verongida. For this we have studied the 505 million year old (Middle Cambrian) Burgess Shale Vauxia sponge samples because of the exceptional preservation of these fossils15,17,18,19,20. In the following we demonstrate that chitin is indeed a component of early sponges. We found chitin preserved in Vauxia gracilenta15 from the Burgess Shale, making these sponges the oldest fossils with preserved chitin discovered thus far. This suggests that the Burgess Shale fossils retain more structural, and potentially isotopic, information than previously realized. This is important to the realm of sponge phylogeny, and has impact across the broader world of Cambrian paleontology.

Stringent care was taken in the preparation of our samples and in the analytical protocol to avoid any modern contaminants. These methods are described below.

Results

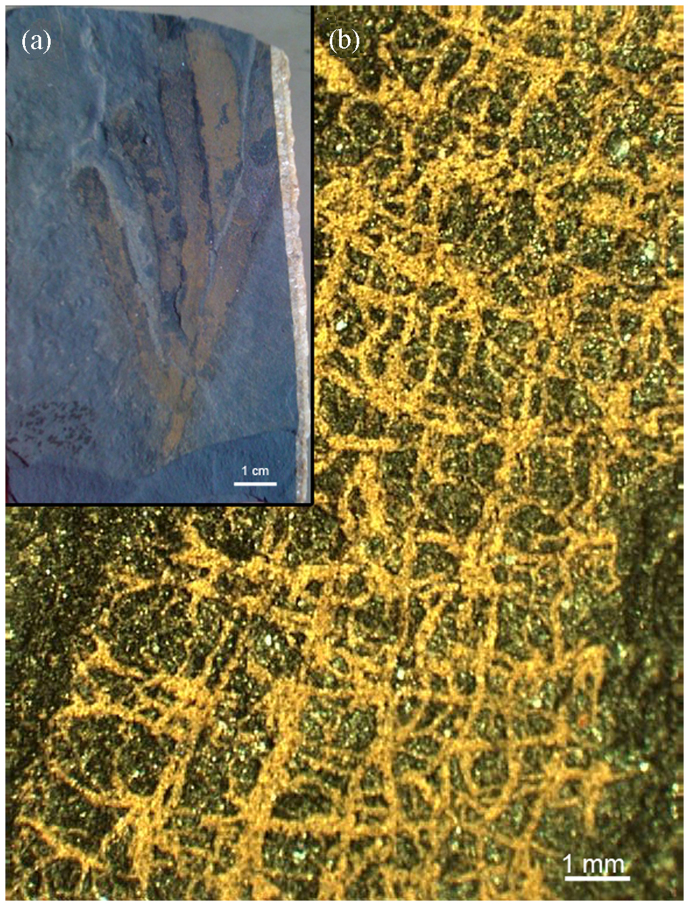

Identification of the polysaccharide-containing remains

The fossilized material consists of brownish anastomosing fibers (diameter ~100 μm) in an arrangement typical of Vauxia (Fig. 1). The dimension of the fibers is characteristic of poriferans. There are no reports of fungi or filamentous bacteria containing any fibers of similar diameter (see for comparison4). In our preparation and analytical protocol, which is described in the following, we tried to avoid any possible problems that may arise from modern contaminants. A 14C analysis only yielded a low fraction of modern 14C of 0.0057, where “modern” is defined as 95% of the radiocarbon concentration (in AD 1950) of NBS Oxalic Acid I (SRM 4990B) normalized to δ13CVPDB = −19 per mil. This confirms that the analysed organic material must contain ancient carbon (see Supplementary Information, text). Raman spectroscopy of the organic material suggests that all investigated samples had the same origin with respect to thermal low-grade metamorphism (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2). The results from the DNA identification study (Supplementary Information, Fig. S21) revealed the absence of DNA in the material isolated from fossilized V. gracilenta. This is a good indicator that there are no modern bacteria or fungi contaminates in the fossils, or in the instrumentation used to investigate them.

Figure 1. Optical micrographs from the studied sample.

Burgess Shale sample with the fossil demosponge V. gracilenta (a) with detail of the exceptionally preserved skeleton (b).

Initially, three samples (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1) were examined under a fluorescence microscope to highlight any polysaccharide-based organic matter using the specific Calcofluor White (CFW) staining. Calcofluor White is a fluorescent marker capable of making hydrogen bonds with β-(1.4)- and β-(1.3)-linked polysaccharides, and shows a high affinity for chitin7,8,9. Recently, it was confirmed experimentally that CFW specifically binds to carbohydrate residues and not to the protein matrix, even when staining glycoproteins21. This method has previously been used successfully at a microscopic scale to identify chitin-containing organisms attached to the surfaces, or embedded within different kind of materials22. If a chitin-containing material is present, the chitin will bind the dye and, upon exposure to light, the chitin-containing material may be visualized and can then be removed for further investigations. We used material from the third fossil sample (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1), which is preserved in remarkable morphological detail (Fig. 1). We selected areas on the surface of sample (Fig. 1b) where the fibrous morphology of the Vauxia skeleton is clearly visible in a binocular microscope, and then stained them with CFW. The skeleton was stained with variable intensity, which is clearly visible using fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2 a, b). We found several fragments (Supplementary Information, Fig. S4a) that were highly stained by CFW and precisely resembled the fibres observed by electron microscopy in size and shape. These preliminary results indicate the presence of polysaccharide material localized within well-preserved fossilized fibers of the sponge skeleton.

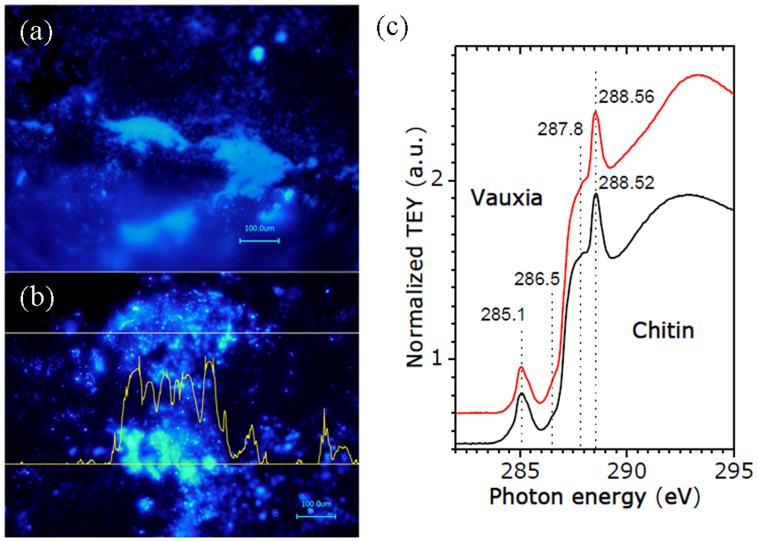

Figure 2. Preliminary identification of chitin.

Calcofluor white staining of the cleaned surface of V. gracilenta with fluorescence, indicating the presence of polysaccharide-based compounds (a, b). Isolated and HF-demineralized fibers were identified as chitin using NEXAFS spectroscopy (c).

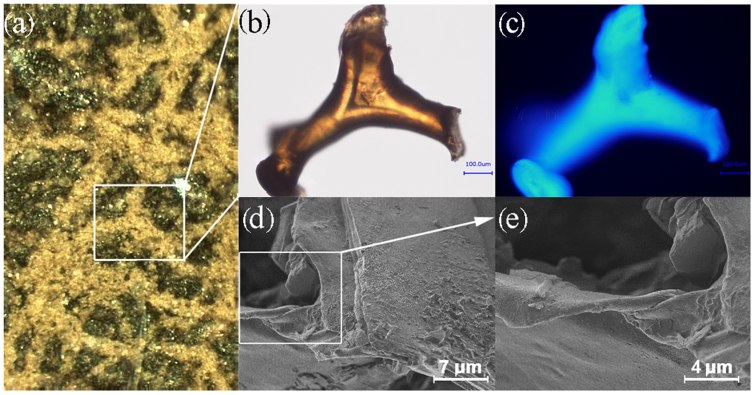

Selected fibers showing the presence of polysaccharides were carefully broken from the host rock using a very sharp steel needle under a stereomicroscope. Some of the fragments obtained in this way and showing a well-preserved fibrous structure (Fig. 3) were investigated as removed using light, fluorescence and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The majority of the fragments were transferred to plastic vessels with 48% HF for 24 h at room temperature to remove aluminosilicates (Supplementary Information, Fig. S4b). Following this, the samples were centrifuged and the insoluble residue was washed five times using deionized water.

Figure 3. Structural features of the fossil sponge skeleton.

A selectively isolated fragment (b) of the aspiculate fibrous skeleton of V. gracilenta (a) shows autofluorescence (c) that is characteristic for chitin. The non-homogenous fluorescence can be explained by the presence of a residual mineral phase observed using SEM (d, e).

The residual material was placed onto glass slides that had been cleaned in acetone. Micro-fibers or micro-particles were excluded from the slide using light and fluorescence microscopy. The 25 slides with residual material were observed using light and fluorescence microscopy, and we isolated fragments possessing fibrillar microstructure. All of these show strong autofluorescence in the region of 470–510 nm, consistent with that of chitin (Supplementary Information, Fig. S5).

Identification of chitin

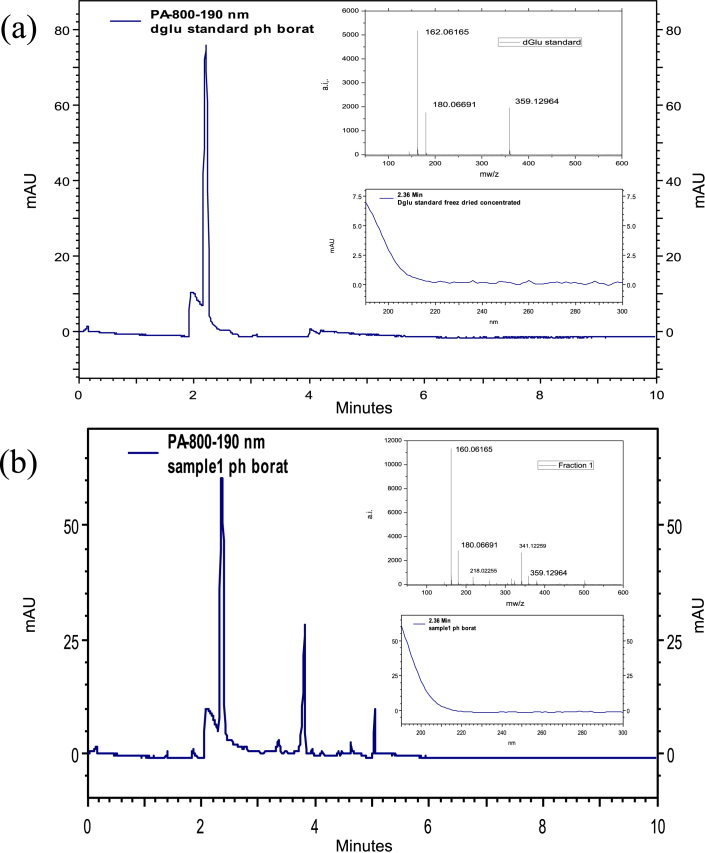

Our criteria for the positive identification of chitin are based on comparative investigations between a chitin standard and selected samples using the highly sensitive analytical techniques shown below; as well as the detection of D-glucosamine and the use of the chitinase test. Thus, selected samples of isolated material were analysed by near-edge X-ray absorption fine structure (NEXAFS) spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Chitin, which may be considered a polymer of 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-CX-D-glucopyranose (N-acetyl-D-glucosamine), yields D-glucosamine on acid hydrolysis. Detection of D-glucosamine is required as the final step in supporting the survival of chitin in the fossil record23. Other samples were therefore hydrolysed to test for the presence of D-glucosamine (DGlcN) using High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), High Performance Size Exclusion Chromatography (HPSEC), High Performance Capillary Electrophoresis (HPCE), and Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS). One fragment was also used for experimental chitinase digestion. In all these experiments the samples from the surrounding rock of the analysed fibers were tested as a negative control. Thus, those modern contaminations capable of surviving the purification techniques we used would be present in both the analysed fibers and the surrounding rock.

NEXAFS spectroscopy was used to explore site-specific electronic properties of isolated fibres (measured on 500 μm × 500 μm areas). The carbon K-edge spectrum of investigated material showed all the typical absorption features of chitin (~288.5 eV)24 (Fig. 2c). We also show that the characteristic C = O absorption peak of chitin is clearly distinguishable from a strong cellulose peak reported at 289.5 eV24.

The results of the structural and spectroscopic analyses performed using NEXAFS (Fig. 2c), FTIR, and CFW staining (Supplementary Information, Fig. S6), and electron diffraction (Supplementary Information, Fig. S7) agreed that the demineralized fibrous material isolated from fossilized V. gracilenta consists in part of α-chitin. The results of our analyses for the investigated fractions of the fibers were fully consistent with those of previous reports on the physicochemical identification of chitin in other organisms7,8,9.

Chitinase digestion experiments (Supplementary Information, Fig. S8) again confirmed the chitinous nature of the isolated V. gracilenta fibers. Additionally, results obtained using HPLC, HPSEC, HPCE and ESI-MS (Fig. 4) clearly indicate that the sample contains a species that is highly similar in its properties to DGlcN. The presence of D-glucosamine in the exceptionally preserved fibrous matter which is isolated from the rock, but absent in the surrounding rock (Supplementary Information, Fig. S22 and S23), clearly shows its fossil origin.

Figure 4. Identification of D-glucosamine as the final step in supporting the presence of chitin in the fossil V. gracilenta.

HPCE chromatograms as well as ESI-MS results give unambiguous evidence that D-glucosamine is present in the investigated samples (b) when compared with results from a chitin standard (a).

Discussion

Experimental studies from modern organisms suggest that chitin may remain chemically stable enough for paleoecological and paleoclimatic information to be derived from stable isotope analysis25. The thermal stability of chitin depends on the crystalline form, and on the size and perfection of crystallites. The α-chitin (found in arthropods and sponges) is thermally more stable than β-chitins (diatoms, squid)26. Thermogravimetric analysis of purified non-mineralized chitin revealed that this aminopolysaccharide is stable up to 360°C26, as shown in experiments in vitro. We have also confirmed the laboratory stability of sponge chitin for 24 hours at 300°C (see Supplementary Information, text).

Studies of the survival of chitin in fossils have yielded mixed results1,17,23,27,28. Much paleontological literature still refers to fossil material as being chitinous, based primarily on its resistance to chemical attack and the relationship of fossils to modern organisms. It is generally understood, however, that the chitin has probably been converted to a more stable material. Some analyses have suggested the presence of chitin in fossils that date back as far as the early Paleozoic (as evidenced by D-glucosamine)27. Other analyses, however, have failed to find any evidence of its presence in fossils29, except for small amounts of amino sugars in the calcified skeletons of one Cretaceous and one Tertiary decapod crustacean30. Significant quantities of chitin were detected by analytical pyrolysis in Quaternary beetles1 and in fossil insects from Oligocene lacustrine shales of Enspel, Germany1. In all reports, confirmation of the survival of the chitin polymer required the detection of its hydrolysate monomer, D-glucosamine.

Here we have demonstrated that chitin may persist over 505 million years in sediments where suitable paleoenvironmental conditions prevailed. In addition, our results confirm that Vauxia is a “keratose” demosponge rather than a demineralised spicular sponge. Morphological considerations assign the Vauxiidae as likely being in the Verongida, or alternatively to a stem-group of “keratosan” demosponges. Recent molecular work often places the “keratosans” at the base of demosponge phylogeny31, although with uncertain relationships to other taxa. The Vauxiidae are therefore likely to be the most basal definitive demosponge group known, despite the abundance of protomonaxonid “demosponges” in the Cambrian fossil record. In addition, the chitinous character of the Vauxia skeleton would refute previous suggestion32 that a keratose skeleton secondarily and independently arose twice among the demosponges, through the loss of spicules and subsequent development of spongin fibers.

The phenomenon of exceptional fossil preservation, especially the preservation of soft tissues, is one of the most disputable questions in modern paleontology. Different and sometimes controversial modes for this preservation in Burgess Shale fossils have been proposed by N. Butterfield, P. J. Orr, R. Petrovich, W. Powell (see for review33) as well as by D. Briggs, R. Gaines (see for review34). The mechanism of chitin preservation in our case is unknown. It has been suggested that the preservation potential of arthropod cuticle is increased when the chitin is cross-linked in a thick sclerotized cuticle like that of beetles, a phenomenon first demonstrated in laboratory experiments29. This suggests that chitin preservation is the reason for the abundance of arthropod cuticles preserved organically in the fossil record. Recently reported5 preservation of a high-nitrogen-content chitin-protein residue in Paleozoic organic arthropod cuticle likely depends on condensation of cuticle-derived fatty acids onto a structurally modified chitin-protein molecular scaffold, thus preserving the remnant chitin-protein complex and cuticle from degradation by microorganisms.

There is no information about possible cross-linking agents in sponge chitin similar to those reported for arthropods. However, bromotyrosine-related compounds present in the skeletons of recent verongids are known to be chitinase inhibitors35. We suggest that these compounds were crucial for the survival of vauxiid sponges in the Burgess Shale during early post-burial. Pyrite-like sulphides were also observed on the surface of the fossil (Supplementary Information, Fig. S9). Intriguingly, the novel taphonomic pathway for chitin preservation (low oxygen and Fe2+ as a chitinase inhibitor) recently proposed by Weaver and co-workers2 cannot be excluded as a mechanism in Vauxia fossils.

The ability to isolate and identify chitin from a 505-million-year-old fossil is due to several factors. These include the exceptional preservation conditions of the locality, the stabilizing effects of bromotyrosine-related compounds specific to the Vauxia sponges, and certainly due to the advances in analytical techniques that are routinely available today. Our discovery significantly extends the length of time chitin can survive under geological conditions, considering that the oldest chitin reported previously is 417 million years old5. We hope that our exceptional finding will encourage researchers to search for chitin in other well-preserved ancient fossils.

Methods

Samples

The samples of Vauxia gracilenta (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1) (accession numbers ROM 75-2840, ROM 75-2854, ROM 61-237) were obtained from Department of Natural History, Paleobiology, Toronto, ON, Canada. The whole samples of the rock as collected with fossilized Vauxia (Supplementary Information, Fig. S1) were initially washed in deionized water, followed by applying an EDTA-based Osteosoft (Merck) solution (24 h) to the fossil surface (Supplementary Information, Fig. S2). Then the sample was washed again with deionized water, and finally sonicated in deionized water for 4 h at room temperature. Fossilized material that was still attached to the rock surface after this procedure was investigated by isolating samples for analysis.

Near-edge X-ray absorption fine structure (NEXAFS)

We used NEXAFS spectroscopic methods established at BESSY, Berlin. All images chosen for this paper are representative examples of features observed several times for different samples.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra were recorded on a Kaiser HoloLab Series 2000 microscope (10× magnification) coupled to an f/1.8 Holospec spectrograph (Kaiser Optical Systems, Ann Arbor MI, USA) with a liquid nitrogen cooled CCD camera (Roper Scientific, Trenton NJ, USA). A Toptica XTRA laser (Toptica Photonics AG, Graefelfing, Germany) with an excitation wavelength of 785 nm was used. Laser power on each sample was 15 mW with an exposure time of 30 s. For each sample three spectra were acquired and averaged.

Data was normalized to the maximum in the displayed range of wave numbers. For the plot of the overlaid spectra a multipoint linear baseline correction was applied, with points at 1100, 1200, 1650 and 1800 cm−1. For the lower wave number range a simple linear baseline correction was used with points at 320 and 700 cm−1.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR spectroscopy was carried out using FTIR Bruker IFS 66/s. The spectral resolution was 2 cm−1 and the number of scans was 500. The spectral range investigate was 3900–1000 cm−1. The instrument had an aperture of 1 mm, an MCT Detector and a mirror rate of 40 KHz.

Fluorescence microscopy and spectroscopy

Fluorescence microscopy was performed by using a Zeiss LSM 510 META device at an excitation wavelength of 405 nm and a beam splitter separating excitation from emission (HFT 405/514). The splitter reflects two spectral bands around 405 nm and 514 nm, designed to be used simultaneously with two lasers with wavelength of 405 and 514 nm. Therefore, there is a gap in the emission around 514 nm.

A Plan-Neofluar 10×/0.3 objective was used. The detector was a Zeiss META detector which can detect the emission in user-defined spectral ranges. We used 32 detection channels, all 10.7 nm wide, covering the spectral range between 411.3–753.7 nm.

For more details on Methods, see the Supplementary Information.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the design and/or execution of experiments and/or analyzed data. H.E. supervised experiments, carried out demineralization experiments, and wrote the manuscript. P.S. and D.K. performed SEM, EDX, TEM and prepared figures. J.K.R., A.P. and J.P.B. identified sponge samples and contributed to writing the manuscript. V.S., D.V.V. and S.L.M. performed NEXAFS experiments and designed figures. M.V.T., R.B., S.H. and M.K. performed FTIR and Raman and prepared figures. P.Sc., V.V.B. and Z.P. performed fluorescence microscopy and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. C.W. and M.V.T. performed HPLC, HPSEC, HPCE and ESI-MS. D.S. performed the thermogravimetric analysis, A.S. performed the 14C analysis and T.G. wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by DFG Grant EH 394/3-1, the Erasmus Mundus External Co-operation Programme of the European Union 2009, the BHMZ Programme of Dr.-Erich-Krüger-Foundation (Germany) at TU Bergakademie Freiberg, BMBF within the project CryPhys Concept (03EK3029A), and the RFBR grant 12-02-00088a and bilateral program of the RGBL at BESSY II. We cordially thank J.-B. Caron, Royal Ontario Museum, Canada, for samples as well as Prof. Eike Brunner for use of the facilities at Institute of Bioanalytical Chemistry, TU Dresden. We are deeply grateful Dr. A. Stelling, O. Trommer and J. Buder for great technical assistance.

References

- Stankiewicz B. A., Briggs D. E. G., Evershed R. P., Flannery M. B. & Wuttke M. Preservation of chitin in 25-millionyear old fossils. Science 276, 1541–1543, 10.1126/science.276.5318.1541 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Weaver P. G. et al. Characterization of Organics Consistent with β-Chitin Preserved in the Late Eocene Cuttlefish Mississaepia mississippiensis. PLoS ONE 6, e28195, 10.1371/journal.pone.0028195 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey T. H. P., Ortega−Hernández J., Lin J.-P., Zhao Y. & Butterfield N. J. Burgess Shale−type microfossils from the middle Cambrian Kaili Formation, Guizhou Province, China. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 57, 423–436 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Redecker D., Robin Kodner R. & Graham L. E. Glomalean Fungi from the Ordovician. Science 289, 1920–1921 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody G. D. et al. Molecular signature of chitin-protein complex in Paleozoic arthropods. Geology 39, 255–258, 10.1130/G31648.1 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich H. et al. First evidence of the presence of chitin in skeletons of marine sponges. Part II. Glass sponges (Hexactinellida: Porifera). J. Exp. Zool. (Mol. Dev. Evol.) 308B, 473–483, 10.1002/jez.b.21174 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich H. et al. First evidence of chitin as a component of the skeletal fibers of marine sponges. Part I. Verongidae (Demospongia: Porifera). J. Exp. Zool. (Mol. Dev. Evol.) 308B, 347–356, 10.1002/jez.b.21156 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich H. et al. Three dimensional chitin-based scaffolds from Verongida sponges (Demospongiae: Porifera). Part I. Isolation and Identification of Chitin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 47, 132–140, 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.05.007 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner E. et al. Chitin-based scaffolds are an integral part of the skeleton of the marine demosponge Ianthella basta. J. Struct. Biol. 168, 539–547, 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.06.018 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich H. et al. Identification and first insights into the structure and biosynthesis of chitin from the freshwater sponge Spongilla lacustris. J. Struct. Biol. 183, 474–483, 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.06.015 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe H. et al. Phylogenomics revives traditional views on deep animal relationships. Curr. Biol. 19, 706–712, 10.2475/ajs.301.8.683 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitner J. & Wörheide G. History of Preservation. In Systema Porifera: A Guide to the Classification of Sponges, (ed. Hooper, J. N. A. & Van Soest, R. W. M.) pp. 52–68. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Sperling E. A., Peterson K. J. & Laflamme M. Rangeomorphs, Thectardis (Porifera?) and dissolved organic carbon in the Ediacaran oceans. Geobiology 9, 24–33, 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2010.00259.x (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love G. D. et al. Fossil steroids record the appearance of Demospongiae during the Cryogenian period. Nature 457, 718–721, 10.1038/nature07673 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walcott C. D. Middle Cambrian spongiae. Cambrian geology and paleontology IV. Smithsonian Misc. Coll. 67, 261–289 (1920). [Google Scholar]

- Rigby J. K. Sponges of the Burgess Shale (Middle Cambrian), British Columbia. Palaeontographica Canadiana 2, 1–105 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Briggs D. E. G., Erwin D. H. & Collier F. J. The Fossils of the Burgess Shale. Smithsonian Institution Press (1994).

- Orr P. J., Briggs D. E. G. & Kearns S. L. Cambrian Burgess Shale animals replicated in clay minerals. Science 281, 1173–1175, 10.1126/science.281.5380.1173 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines R. R., Briggs D. E. G. & Zhao Y. L. Cambrian Burgess Shale-type deposits share a common mode of fossilization. Geology 36, 755–758, 10.1130/G24961A.1 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. P. & Briggs D. E. G. Burgess shale-type preservation: a comparison of Naraoiids (Arthropoda) from three Cambrian localities. PALAIOS 25, 463–467, 10.2110/palo.2009.p09-145r (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Albani J. D. Förster energy-transfer studies between Trp residues of a1-acid glycoprotein (orosomucoid) and the glycosylation site of the protein. Carboh. Res. 338, 2233–2236, 10.1016/S0008-6215(03)00360-4 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Patent 6875421 Method for detecting chitin-containing organisms.

- Flannery M. B., Stott A. W., Briggs D. E. G. & Evershed R. P. Chitin in the fossil record: identification of D-glucosamine. Org. Geochem. 32, 745–754, 10.1130/G20640.1 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Mancosky D. G. et al. Novel vizualization studies of lignocellulosic oxidation chemistry by application of C-near edge X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy. Cellulose 12, 35–41, 10.1023/B:CELL.0000049352.60007.76, (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. F. Chitin Paleoecology. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 19, 401–411 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Stawski D., Rabiej S., Herczynska L. & Draczynski J. Thermogravimetric analysis of chitins of different origin. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 93, 489–494, 10.1007/s10973-007-8691-6 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle D. B. Chitin in a Cambrian fossil. Biochem. J. 90, lc–2c (1964). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. F., Voss-Foucart M. F., Toussaint C. & Jeuniaux C. Chitin preservation in Quaternary Coleoptera: preliminary results. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 103, 133–140 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Baas M., Briggs D. E. G., van Heemst J. D. H., Kear A. J. & de Leeuw J. W. Selective preservation of chitin during the decay of shrimp. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 945–951 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Brumioul D. & Voss-Foucart M. F. Substances organiques dans les carapaces de crustaces fossiles. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 57B, 171–175 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Erpenbeck D. & Wörheide G. On the molecular phylogeny of sponges (Porifera). In: Linnaeus Tercentenary: progress in invertebrate taxonomy, Zootaxa 1668 (eds. Zhang, Z.-Q. & Shear, W. A.), pp. 107–126, Auckland (New Zealand): Magnolia Press (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado M. Embryonic development of verongid demosponges supports the independent acquisition of sponging skeletons as an alternative to the siliceous skeleton of sponges. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 97, 427–447, 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2009.01202.x (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Powell W. Greenschist-facies metamorphism of the Burgess Shale and its implications for models of fossil formation and preservation. Can. J. Earth Sci. 40, 13–25, 10.1139/E02-103 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Schiffbauer J. D., Hua H. & Xiao S. Preservational modes in the Ediacaran Gaojiashan Lagerstätte: Pyritization, aluminosilicification, and carbonaceous compression. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 326–328, 109–117, 10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.02.009 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Tabudravu J. N. et al. Psammaplin A, a chitinase inhibitor isolated from the Fijian marine sponge Aplysinella rhax. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 10, 1123–1128, 10.1016/S0968-0896(01)00372-8 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information