Abstract

Type IIA DNA topoisomerases are essential enzymes that use ATP to maintain chromosome supercoiling and remove links between sister chromosomes. In Escherichia coli, the type IIA topoisomerase topo IV rapidly removes positive supercoils and catenanes from DNA but is significantly slower when confronted with negatively supercoiled substrates. The ability of topo IV to discriminate between positively and negatively supercoiled DNA requires the C-terminal domain (CTD) of one of its two subunits, ParC. To determine how the ParC CTD might assist with substrate discrimination, we identified potential DNA interacting residues on the surface of the CTD, mutated these residues, and tested their effect on both topo IV enzymatic activity and DNA binding by the isolated domain. Surprisingly, different regions of the ParC CTD do not bind DNA equivalently, nor contribute equally to the action of topo IV on different types of DNA substrates. Moreover, we find that the CTD contains an autorepressive element that inhibits activity on negatively supercoiled and catenated substrates, as well as a distinct region that aids in bending the DNA duplex that tracks through the enzyme’s nucleolytic center. Our data demonstrate that the CTD is essential for proper engagement of both gate and transfer segment DNAs, reconciling different models to explain how topo IV discriminates between distinct DNAs topologies.

Keywords: type IIA topoisomerase, substrate discrimination, DNA binding, DNA bending, DNA topology

Introduction

DNA topoisomerases are ubiquitous and essential enzymes that maintain the topological homeostasis of chromosomes. Type IIA topoisomerases use ATP to modulate chromosome supercoiling and interlinking (catenation) by binding and cleaving one duplex DNA (termed the gate segment or G-segment), passing another duplex DNA (the transfer segment or T-segment) through the transient opening, and religating the break [1-4]. Since the type IIA topoisomerase catalytic cycle has the potential to create toxic, double-stranded DNA breaks, topoisomerases are highly regulated to ensure proper activity and localization. Regulation can be mediated both intrinsically, through specific physical elements and post-translational modifications, and extrinsically, through direct physical interactions with other proteins (for review, see Ref. [5]). The regulatory programs that define type IIA topoisomerase function on specific substrates or during particular periods of the cell cycle are still emerging.

Most bacteria encode two type IIA topoisomerase paralogs, gyrase and topoisomerase IV (topo IV) [6-8]. Gyrase and topo IV share a common heterotetrameric architecture (GyrA2·GyrB2 or ParE2·ParC2), as well as substantial sequence homology. Despite these similarities, however, gyrase and topo IV perform distinct functions. Gyrase actively introduces negative supercoils into DNA to counteract the introduction of positive supercoils by processes such as replication and transcription [6,9]. By contrast, topo IV preferentially removes positive supercoils and resolves catenanes from DNA formed during DNA replication but is less active on negatively supercoiled substrates [10-15].

The functional differences between gyrase and topo IV have been ascribed (at least in part) to variations in the C-terminal domains (CTDs) of their respective GyrA and ParC subunits. The GyrA and ParC CTD share a common β-pinwheel fold that is formed by a series of repeating Greek key motifs or “blades” (Fig. 1a and b) [18-20]. The GyrA CTD is a DNA binding and wrapping domain composed of six blades [20-22], along with a conserved motif known as the “GyrA-box”, which can latch the first blade of the domain to the last blade [23,24]. Loss of either the GyrA CTD or the GyrA box abolishes the ability of gyrase to supercoil DNA but does not abrogate strand passage [25-27]. ParC CTDs can bind but not wrap DNA substrates, and have a variable number of blades (from three to eight, proteobacterial versions possess five) [18,20,28]. Although the ParC CTD does not contain a canonical GyrA box, degenerate remnants of the motif are found in each of its blades (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1) [28]. Loss of the Escherichia coli ParC CTD does not completely abolish relaxation and decatenation by topo IV but does generally disrupt the ability of the enzyme to distinguish between topologically distinct substrates [20].

Fig. 1.

ParC CTD structure and organization. (a) Primary structure of ParC. The ParC NTD is colored gray and the blades of the ParC CTD are colored according to number. A cartoon schematic of the ParC CTD is on the right (colored spots correspond to positions assayed in this work). (b) Cartoon representation of the E. coli ParC CTD crystal structure [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID: 1ZVT], top and side views. Residues assayed in this work are shown by stick representation. All figures depicting crystal structures were generated in PyMOL [16]. (c) Electrostatic representation of the E. coli ParC CTD crystal structure (PDB ID: 1ZVT) outer surface, top and side views. The outer, curved surface of the domain is rich in positive charges. (d) Sequence conservation of γ-proteobacterial ParC CTD residues residing in remnant GyrA boxes. Sequence logos generated in enoLOGOs [17]. Residues assessed in this work are indicated under each logo. For a more complete sequence alignment, see Supplementary Fig. 1.

How topo IV discriminates positively supercoiled DNAs from negatively supercoiled substrates has been a subject of debate. In one study, multiple DNA molecules were braided at the single-molecule level to simulate crossovers found in positively and negatively supercoiled substrates. These experiments found that topo IV relaxed crossovers found in positively supercoiled substrates more readily than crossovers found in negatively supercoiled DNAs, suggesting that specificity was determined by an ability of the enzyme to sense the chirality of G- and T-segment crossing angles within the topo IV active site [10]. A subsequent single-molecule study set out to test this model by assaying the ability of topo IV to act on a variety of crossover angles between only two DNA duplexes, rather than braids; however, these experiments found that topo IV showed no preference for positive versus negative crossovers [14] and that discrimination instead arose from differences in enzyme processivity on positively and negatively supercoiled substrates [14]. In yet a third effort, structural and biochemical studies of ParC have suggested that the CTD may associate with T-segment DNAs and hence provide a means to influence activity [20].

To better understand how the ParC CTD might aid in topology discrimination by E. coli topo IV, we mutated potential DNA interacting residues on the positively charged outer surface of the domain and tested the effect of these substitutions on enzyme function. Unexpectedly, we found that distinct regions of the ParC CTD contribute differentially to DNA binding affinity and the action of topo IV on specific types of DNA substrates. Some sites appear to actively repress activity on negatively supercoiled and catenated substrates, whereas others are more important for functions such as G-segment bending. Together, these studies indicate that topo IV can indeed sense the juxtaposition of G- and T-segment crossovers but that this discrimination—which acts in part through controlling enzyme processivity—occurs outside the active site where strand passage takes place.

Results

Construction and solution behavior of ParC CTD mutants

Although the CTD of E. coli ParC has been shown to be important in topology discrimination by topo IV [20], the mechanism of this effect has remained unknown. The CTDs of ParC and GyrA have been suggested to bind DNA using the positively charged rim that encircles the domain [18-20,29] (Fig. 1c). To more finely dissect the role of this region, we set out to identify prospective DNA binding residues using multiple-sequence alignments of ParC CTD homologs that contain only five blades. We focused first on residues that are both highly conserved and positively charged (Supplementary Fig. 1) and mapped these residues onto the E. coli ParC CTD crystal structure to find surface-exposed amino acids that did not appear to be required for structural stability. This analysis revealed that many of the most highly conserved positions reside in degenerate GyrA-box motifs that reside on the extended loops that latch adjoining blades together (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1). We also identified a positively charged patch on the fifth blade that contains two arginines previously suggested to interact with the E. coli condensin homolog, MukB (Arg705 and Arg729) [30,31].

Given the criteria described above, we next mutated representative basic residues from each of the five blades to aspartate, using charge substitutions to actively disfavor potential electrostatic interactions that might occur with DNA. Full-length ParC mutants were purified to homogeneity and then subjected to size-exclusion chromatography to confirm that the introduced mutations did not cause the proteins to aggregate (Supplementary Fig. 2). Of all the mutations surveyed, only one (Arg721Asp) did not behave as a monodisperse species and so was discarded; interestingly, this locus lies in close proximity to a previously identified ParC temperature-sensitive allele, Gly725Asp [8]. An alternative residue within this region, Arg723Asp, which is nearly as well conserved (Supplementary Fig. 1), was chosen in lieu of Arg721 and found to behave as per the wild-type (WT) protein in solution. To ensure that the CTD mutants were properly folded at the temperatures used in our enzymatic assays, we measured circular dichroism (CD) spectra for each mutant at 25 °C and 37 °C (Supplementary Fig. 2). In each case, the CD spectra for all mutants were similar to that of WT ParC, indicating that the substitutions did not lead to gross perturbations in protein structure (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Conserved, basic amino acids in the ParC CTD are important for positive-supercoil relaxation

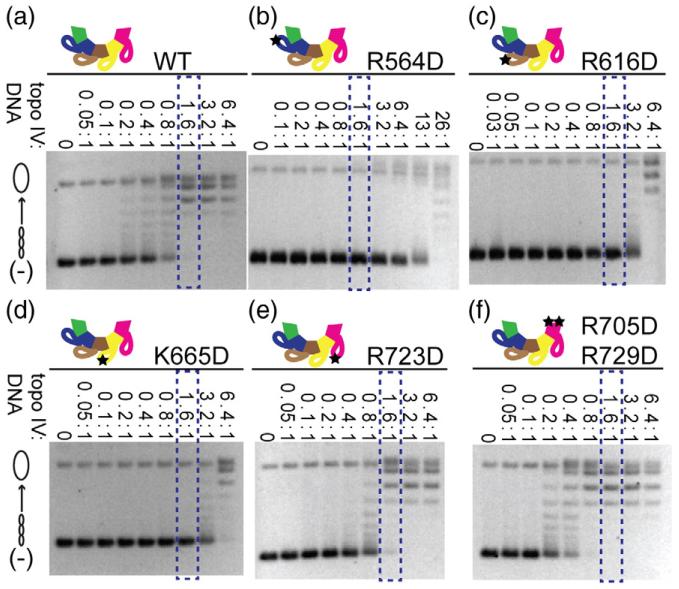

After purifying our CTD mutants, we proceeded to conduct enzyme assays for standard topo IV activities on different types of DNA substrates using native agarose gel electrophoresis. In the absence of a DNA intercalating agent, supercoiled DNA migrates faster than intermediate, relaxed, and nicked topoisomers through the gel matrix. We initially tested the ability of our ParC mutants to relax topo IV’s favored substrate, positively supercoiled DNA. Different concentrations of enzyme were titrated against a fixed concentration of DNA to look for general defects in activity (Fig. 2). We discovered that mutations within the CTD of ParC exhibited a broad range of activity profiles, ranging from essentially WT behavior to severe defects in the efficiency and/or processivity of supercoil relaxation [a detailed explanation of topoisomerase processivity is provided in Supplementary Fig. 3; relative defects in processivity are roughly quantified by comparing the amount of mutant topo IV required to produce a final topoisomer distribution similar to that seen for the WT enzyme (boxed in blue, Fig. 2)]. For example, mutation of positions within blade 5 (Arg705Asp/Arg729Asp) resulted in no change in activity or processivity, whereas mutation of blade 1 (Arg564Asp) significantly impaired both (~10-fold decrease). Other mutations primarily affected enzyme processivity; substitutions to blades 2–4 (Arg616Asp, Lys665Asp, Arg723Asp) led to particularly distributive behavior.

Fig. 2.

General activity of WT and mutant topo IVs on positively supercoiled DNA substrate. The constructs assayed are shown in each panel. Each assay proceeded for 10 min prior to quenching and contained 7.9 nM of a positively supercoiled plasmid and various concentrations of each topo IV construct (0.005–50 nM), with the ratio of topo IV to DNA indicated above each gel. A schematic of the topoisomer distribution is illustrated on the left side of the gels. Blue boxes correspond to the enzyme concentration at which WT topo IV removes all positive supercoils and reaches its final topoisomer distribution and is shown for reference. Asterisks indicate the concentration of protein used for the positive-supercoil relaxation time course (Fig. 3).

To further characterize the effects of ParC CTD mutations on positively supercoiled DNA, we looked at relaxation using a fixed molar excess of DNA compared to topo IV (~50-fold) as a function of time. This regime permitted us to observe differences in rate of relaxation in addition to changes in processivity. Interestingly, all mutations tested actually modestly enhanced the overall rate of positive-supercoil relaxation by topo IV compared to the WT protein, with the exception of Arg564Asp in blade 1, which was severely compromised (Fig. 3). As with the enzyme titration assays, however, defects in processivity were again observed for mutations in blades 2 and 3, and, to a lesser extent, blade 4. Together, these data demonstrate that positively charged amino acids on the CTD of ParC not only influence the activity of topo IV on positively supercoiled DNA but also unexpectedly show that different blades make different contributions to activity.

Fig. 3.

Rate of positive-supercoil relaxation by WT and mutant topo IVs. The constructs assayed are shown in each panel. Assays contained one topo IV holoenzyme for every 50 positively supercoiled plasmid molecules. Samples were quenched at the time points indicated above each gel. The blue box corresponds to the time at which WT topo IV removed all positive supercoils and achieved its final topoisomer distribution and is shown for reference. Topoisomer species are graphically illustrated on the left side of the gels.

Basic residues on the ParC CTD differentially affect decatenation and negative-supercoil relaxation

We next tested the ability of our ParC CTD mutants to act on kinetoplast DNA (kDNA), which forms networks of ~5000 2.5-kb minicircles that are a favored substrate of topo IV [32-35]. When visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis, the kDNA network is too large to pass into the gel matrix and remains trapped in the wells; however, in the presence of topo IV or other topoisomerases, kDNA minicircles are released into the gel matrix [36]. Although the processivity of topo IV on kDNA cannot be evaluated in this assay, the activity of the enzyme can be monitored as an increase in the amount of minicircle produced as a function of either protein concentration or time. We first examined the ability of different quantities of topo IV to decatenate the substrate at a fixed concentration of kDNA (Fig. 4). As with the relaxation of positively supercoiled DNA, mutations in the ParC CTD exhibited a broad range of functional effects. Mutation of blades 2 and 4 had only a modest effect on decatenation. By contrast, mutation of blade 3 markedly reduced enzymatic activity (~10-fold), while the blade 1 substitution almost entirely abrogated minicircle release. Unexpectedly, the blade 5 mutation appeared to increase the activity of topo IV on kDNA nearly 10-fold (as indicated by a need for a lower amount of enzyme to fully unlink the catenated network).

Fig. 4.

General activity of WT and mutant topo IVs on kDNA. The constructs assayed are shown in each panel. Each assay proceeded for 10 min prior to quenching and contained 9.2 nM of kDNA and various concentrations of each topo IV construct (0.005–50 nM), with the ratio of topo IV to DNA indicated above each gel. On the left of each gel, a schematic of the catenated substrate trapped in the wells and the released minicircles. Blue boxes correspond to the enzyme concentration at which WT topo IV appears to have removed a majority of the catenanes from the kDNA substrate. The asterisk above each gel indicates the concentration at which each topo IV construct was used in time-course experiments (Fig. 5).

Based on the outcome of this study, we proceeded to perform time-course reactions of topo IV on kDNA (Fig. 5). As with the enzyme titrations, topo IV containing a mutation in blade 2 displayed essentially WT activity. An enhanced ability of the blade 4 and 5 mutations in catalyzing minicircle release was also seen. The substitution to blade 3 again impaired minicircle release (~5-fold decrease), while the blade 1 alteration failed to produce virtually any detectable minicircle product. Overall, these data indicate that blade 1 and, to a lesser extent, blade 3 play a critical role in supporting the activity of topo IV on catenated substrates. Moreover, as with our positive-supercoil relaxation study, different positions on the ParC CTD appear to play an unequal part in the enzyme’s decatenation function.

Fig. 5.

Rate of kDNA resolution by WT and mutant topo IVs. The constructs assayed are shown in each panel. Assays contained approximately 1 topo IV holoenzyme for every 5 kDNA minicircles. Samples were quenched at the time points indicated above each gel. The blue box corresponds to the time at which the WT topo IV enzyme appeared to have removed a majority of the catenanes. Illustrated on the left side of each gel is a schematic of the catenated substrate trapped in the wells and the released minicircles.

To round out our analysis, we next tested the ability of our ParC CTD mutants to relax topo IV’s least favored substrate, negatively supercoiled DNA. As with the experiments using positively supercoiled substrates, enzyme titrations were first performed to look at overall catalytic prowess (Fig. 6). Mutations in nearly every blade led to reproducible changes in the relative amount of enzyme required to produce comparable amounts of relaxed product, with the exception of the mutation to blade 4, which displayed essentially WT activity. Interestingly, activity was actually subtly enhanced by the substitutions in blade 5 (~2- to 3-fold) but reduced by the alterations made to blades 2 and 3 (~10-fold). The blade 1 mutation nearly completely abolished activity overall (~20-fold decrease).

Fig. 6.

General activity of WT and mutant topo IVs on negatively supercoiled DNA. The constructs assayed are shown in each panel. Each assay proceeded for 10 min prior to quenching and contained 7.9 nM of a negatively supercoiled plasmid and various concentrations of each topo IV construct (0.4–50 nM). The ratio of topo IV to DNA indicated above each gel. A schematic of the topoisomer distribution is illustrated on the left side of the gels. Blue boxes correspond to the enzyme concentration at which WT topo IV removes all negative supercoils and reaches its final topoisomer distribution.

To examine these functional effects further, we performed time-course assays using a fixed molar ratio of topo IV to DNA (Fig. 7). Since there proved to be a significant difference in general activity between the blade 4 and 5 mutants of ParC compared to the other constructs, we examined activity with two slightly different enzyme concentrations to observe relaxation within a common time frame (a 1.5-fold molar excess of DNA to topo IV for blades 4 and 5, and a 1.3-fold molar excess of topo IV to DNA for blades 1–3). Under these conditions, we again observed an enhanced rate of relaxation by the blade 5 mutant (~2-fold), whereas the blade 4 mutant exhibited WT behavior. By contrast, the blade 2 and 3 mutants removed negative supercoils very slowly (~10-fold less quickly), while the blade 1 mutant was incapable of removing negative supercoils in the time period assayed. These results, as with the other substrates, indicate that the outer surface of the ParC CTD is important for the control of negative-supercoil relaxation but that different blades again do not contribute equivalently to this activity.

Fig. 7.

Rate of negative-supercoil relaxation by WT and mutant topo IVs. The constructs assayed are shown in each panel. (a–c) Five nanomolar of WT or mutant topo IV was incubated with 7.9 nM of negatively supercoiled plasmid. (d–g) Ten nanomolar of WT or mutant topo IV was incubated with 7.9 nM of negatively supercoiled plasmid. Samples were quenched at the time points indicated above each gel. The blue box corresponds to the time at which the WT topo IV enzyme removed all negative supercoils and achieved its final topoisomer distribution. Topoisomer species are graphically illustrated on the left side of the gels.

Different blades on the CTD have a non-equivalent effect on DNA binding

Because the CTD is thought to be a T-segment binding element, the functional disparities between different mutants in our assays suggested that individual substitutions might be affecting the affinity of the domain for DNA. To test this idea, we assessed the ability of different CTD mutants to bind DNA using fluorescence anisotropy. Because full-length ParC and the topo IV holoenzyme both bind DNA, we looked at the isolated CTD to establish the effects of our substitutions on this region alone. In our initial experiments, we found that the isolated CTD (498–752) tended to aggregate over time. Since this domain is well behaved when connected to the N-terminal DNA binding region of ParC, we overcame this poor solution behavior by fusing the CTD to an inert carrier protein, maltose binding protein (MBP). The MBP-CTD construct proved well behaved, showing no observable tendency to aggregate by gel filtration. We then proceeded to examine the properties of each of our various CTD mutants by incubating different concentrations of the MBP fusion with 20 nM of a fluorescein-labeled 20mer duplex oligonucleotide. The mutants exhibited a broad range of DNA binding activity, with the mutations closest to the N-terminal half of the CTD displaying near-WT levels of affinity. By contrast, DNA binding became progressively impaired as substitutions were made to more C-terminal regions of the domain (Fig. 8a). Thus, as with activity assays, different regions of the ParC CTD contributed differently to DNA binding by the domain. Interestingly, however, the mutations that most significantly affected DNA binding did not necessary correlate with substitutions that showed the greatest effect on enzyme activity.

Fig. 8.

DNA binding by the ParC CTD and DNA binding and bending by topo IV. (a) DNA binding by WT and mutant MBP-ParC CTD constructs. MBP-ParC CTD was titrated against 20 nM of a fluorescein-labeled 20mer duplex oligonucleotide, and DNA binding was measured as a function of change in fluorescence anisotropy (ΔFA), as measured in millianisotropy units (mA). Error bars correspond to the standard deviation between three replicates. Since the MBP-ParC CTD never achieves fully saturated binding isotherm, only relative dissociation constants can be obtained from this assay (Kd,app: WT, ~5 μM; R564D, ~13 μM; R616D, ~14 μM; K665D, ~26 μM; R723D, ~113 μM; R705D/R729D, ~56 μM). (b) DNA binding by WT topo IV, Arg564Asp ParC topo IV, and NTD-ParC topo IV. Topo IV was titrated against 20 nM of a fluorescein-labeled 45mer duplex oligonucleotide, and DNA binding was measured as a function of change in fluorescence anisotropy (ΔFA), as measured in millianisotropy units (mA). The Kd,app of WT topo IV is 25 ± 5 nM and that of R564D topo IV is 15 ± 3 nM. (c) DNA bending by WT topo IV, Arg564Asp ParC topo IV, and NTD-ParC topo IV. Topo IV was titrated against 20 nM of a 45mer duplex, labeled with Cy3 and Cy5. Bending of the oligonucleotide is observed as a change in the relative intensity of the emission spectra of Cy5 (545–720 nm) after excitation of the Cy3 label at 530 nm (arrow).

Blade 1 of ParC CTD is required for G-segment bending

Through the course of conducting our DNA relaxation and decatenation assays, it became apparent that one mutant in particular, Arg564Asp in blade 1, showed greatly impaired activity on all substrates (>90–95% decreases, comparable to deletion of the CTD entirely [20]). However, when we assessed this substitution either in the context of the CTD alone or in topo IV holoenzyme, it had one of the least severe effects on DNA binding (Fig. 8a and b). Given this dichotomy, we were curious as to whether the mutation might disrupt not T-segment interactions per se, but rather some other aspect of topo IV function. Type IIA topoisomerases have been shown to bend the G-segment DNA [37-45]; inspection of the structure of full-length ParC shows that Arg564 lies close to the G-segment binding site of the protein, near the point where the bent DNA arms emanate from the active site (Supplementary Fig. 4). This juxtaposition would appear to be sterically incompatible with the binding of Arg564 to a T-segment, as the transport DNA would clash with a bound G-segment.

Based on this structural consideration, we hypothesized that blade 1 might play a role in linking the CTD to a G-segment associated with topo IV. Because the G-segment binding site of type IIA topoisomerases is large and extensive (comprising >2500 Å2 of surface area [38,41-44,46-48], we did not anticipate observing a strong defect in G-segment affinity per se, an expectation borne out by our affinity measurements (Fig. 8b). Instead, the proximity of blade 1 to the bent arms of a prospective G-segment suggested to us that the amino acid might interrogate the geometry of the associated DNA.

To test this idea, we looked to see whether G-segment bending might be affected by the integrity of the CTD using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). In these experiments, we utilized a 45mer duplex oligonucleotide labeled on opposite strands with Cy3 and Cy5 and the topo IV holoenzyme. Bending was observed after exciting Cy3 with 530 nm and observing changes in the emission from 545 to 720 nm. Consistent with earlier studies, WT topo IV gave rise to a strong FRET signal consistent with the introduction of a sharp DNA bend [40,45] (Fig. 8c). By contrast, the Arg564Asp mutant gave rise to no appreciable change in FRET, indicating that DNA bending was severely compromised in this mutant. To confirm this result, we next tested a ParC construct lacking its CTD entirely. As with the Arg564Asp mutation, this construct likewise failed to induce any observable change in FRET, again indicative of a bending deficiency. Together, these data reveal that the CTD plays an unexpected role in the establishment of a stable G-segment bend by topo IV and further suggest that the significant enzymatic defects we observe in the Arg564Asp mutant are due at least in part to this defect.

Discussion

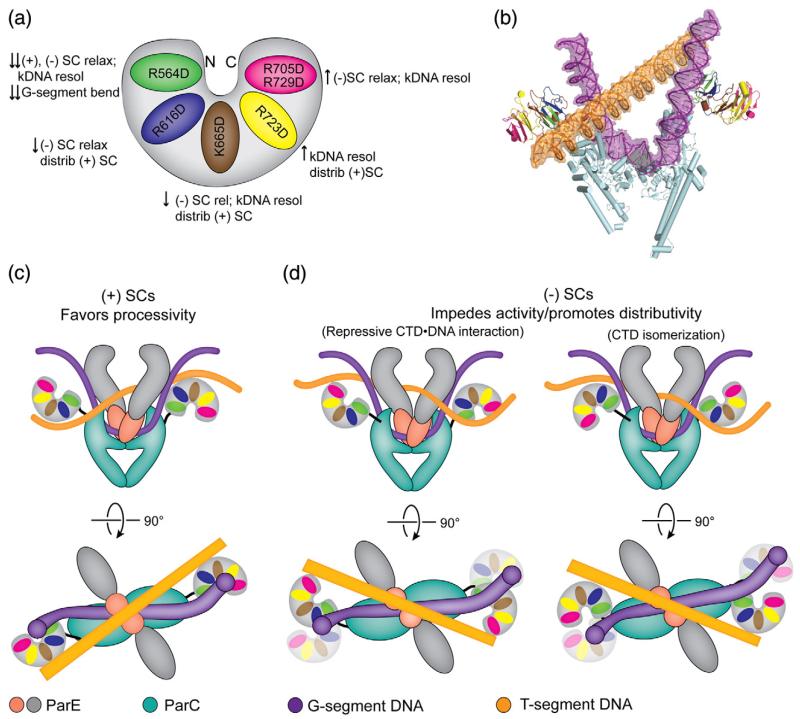

Although all type IIA topoisomerases rely on a generally conserved, ATP-dependent strand passage mechanism for effecting topological changes in DNA, the substrate specificities of different enzyme subfamilies vary significantly. Topo IV discriminates between topologically distinct DNA substrates in a manner that requires the CTD of its ParC subunit [20]; however, the molecular basis for this discrimination has remained ill-defined. It has been postulated that the GyrA and ParC CTDs contribute to substrate discrimination by associating with DNA substrates using their positively charged outer rim[18,26]. To better understand how the ParC CTD might mediate these effects, we identified highly conserved, basic amino acids on CTD surface and mutated these regions to aspartate. We then tested whether these substitutions altered topo IV function on positively supercoiled, catenated, and negatively supercoiled DNA substrates, and whether they altered DNA binding by the isolated domain itself.

Our ParC CTD substitutions reveal an unexpectedly rich pattern of functional contributions emanating from each blade of the domain (Fig. 9). For example, blade 1 is critical for overall topo IV activity on all substrates. By contrast, blade 4 is not essential for general activity on any substrate. Catenane resolution strongly depends on blade 3, while efficient removal of negative supercoils (and to a lesser extent positive supercoils) depends not only on an intact blade 3 but also on blade 2. In addition to modulating general topo IV activity, different substitutions also affected overall processivity, as well as DNA binding by the isolated CTD. Processivity defects were most apparent with blade 2 and 3 substitutions, yet milder defects were also observed upon altering blade 4. We discovered that DNA binding by the isolated domain was strongly perturbed by substitutions to blades 4 and 5, whereas mutations in other blades had a more subtle impact on DNA binding (Fig. 8). Interestingly, the blade 5 mutation actually enhanced the activity of topo IV in relaxing negatively supercoiled DNA and in decatenating kDNA substrates, indicating that the strong DNA binding site associated with blade 5 is actually an auto-inhibitory element that specifically represses negative-supercoil relaxation and catenane resolution. Together, our data show that single mutations made to the positively charged surface of the CTD give rise to specific but differential effects on enzyme activity and processivity depending upon which blade they reside (Fig. 10a).

Fig. 9.

Schematic of ParC CTD activities according to residue. The ParC CTD surface is painted according to the effect of mutations on various functional parameters (general activity, rate, and processivity) on specific substrates. (a) Positively supercoiled DNA. (b) kDNA. (c) Negatively supercoiled DNA. (d) Representative CTD highlighting the effects of mutations on ParC CTD DNA binding. A color key for each activity is found on the right of each CTD.

Fig. 10.

The ParC CTD is a DNA topology discrimination element. (a) Cartoon summary of the effects resulting from mutating different blades of the ParC CTD. Down arrows indicate that the mutations inhibit (down arrow) topo IV activity on specific substrates; up arrows indicate a stimulating effect. Abbreviations: SC, supercoiled; resol, resolution; distrib, distributive; relax, relaxation; (+), positively; (−), negatively. (b) Crystal structure of the ParC dimer (PDB ID: 1ZVU) with G-segment DNA (purple) (PDB ID: 2RGR) docked into the active site and a T-segment (orange) DNA modeled for perspective. (c) Model for topo IV’s potential interactions with positively supercoiled DNA substrates, front and top views. The ParC CTD and the DNA are colored as in (a) and (b). The ParC NTD is colored cyan. The NTD of ParE is colored gray, and the DNA binding C-terminal TOPRIM domain is colored red. DNA is shown associating with surfaces required for processivity and overall enzyme activity. (d) Model for topo IV’s interactions with negatively supercoiled DNA substrates, front and top views. A nonproductive complex between the fifth blade of the ParC CTD and the T-segment DNA could form on negatively supercoiled substrate (left panel) if the ParC CTDs remain in the same rotational orientation as in (c) (illustrated as washed-out CTDs) but were to shift positionally away from a subdomain on the ParC NTD known as the tower. To engage the T-segment of a negatively supercoiled DNA in a catalytically competent manner (right panel), the ParC CTD would need to rotate by 180° about a flexible linker.

Overall, these findings unexpectedly demonstrate that the ParC CTD is not a uniform, nonspecific DNA binding domain, but rather a complex sensor element that can both interrogate the topological status of DNA and use this information to control topoisomerase response. An additional surprise is the finding that one region of the CTD (blade 1) is required not only for activity on all substrates but also for the bending of G-segment DNA. At present, it is unknown how topo IV associates with DNAs outside of the active site; however, this study clearly indicates that specificity for and activity differences on distinct DNA substrates can be attributed to non-equivalent surfaces of the ParC CTD. It is similarly unclear whether ParC orthologs whose CTD blade number varies compared to that of E. coli ParC are able to discriminate between different DNA topologies.

An additional outcome of these data is their ability to help reconcile a debate insofar as how topo IV discriminates between positively supercoiled and negatively supercoiled DNA segments. Early single-molecule experiments using braided DNA substrates led to the hypothesis that topo IV could discriminate between different DNA topologies by recognizing the chiral juxtaposition between G- and T-segments in the topo IV active site [10]. However, a subsequent single-molecule study using single duplex crossovers indicated that topo IV has no preference for DNA duplex crossing angle and that lowered enzyme processivity on negatively supercoiled DNA was instead responsible for the difference in supercoil relaxation rates between underwound and overwound substrates [14]. Our data suggest that topo IV can indeed read out crossover geometry but that sensing of this geometry occurs outside the active site, where it influences not only strand passage efficiency but also enzyme processivity. In this model, positively supercoiled substrates would interact with blades 2, 3, and 4. Negatively supercoiled DNA would also interact with blades 2 and 3 but could further associate with a strong DNA binding site on blade 5 that impedes strand transport and lowers processivity. Catenated DNAs would preferentially engage blades 3 and 4, but likewise be subject to an interaction with blade 5 that slows enzyme function. Blade 1 would play a role in binding the G-segment as a means to both facilitate the bending of this DNA through the active site and help orient the CTD for appropriate readout of substrate DNA topology.

How might the CTD physically mediate such differential effects? One possible mechanistic model for the action of the ParC CTD can be derived by docking a G-segment from a DNA-bound type IIA topoisomerase into the structure of the full-length ParC dimer and modeling T-segment DNA over the active site (Fig. 10b). Such an exercise indicates that the ParC CTD likely adopts alternate conformations with respect to the N-terminal domains (NTDs) to engage the flanking arms of positive- or negative-handed T-segment DNAs after they exit the active site (Fig. 10c and d). The degenerate GyrA box that resides on the surface of blade 1 would help stabilize G-segment bending, a property we recently have found to be critical for enzyme function [45]. The equivalent motifs in other blades, particularly 2 and 3, would be brought to bear on a T-segment by using distinct CTD orientations to distinguish between different types of DNA topologies; when engaged, these elements would promote processive strand passage events, as has been seen on positively supercoiled DNA [10,11,14]. However, in some instances, particular CTD configurations would allow the strong DNA-binding site on blade 5 to counteract the other blades and actively impede strand transport, possibly by slowing T-segment release and contributing to the lowered processivity seen on negatively supercoiled DNA [14]. Although it is not known at present if the CTDs of topo IV are mobile, precedence for such movement can be found in gyrase, whose related domains appear to transit with a T-segment during strand passage [49-51]. The suggestion that the ParC CTD interacts with both the G- and T-segments also has parallels with gyrase, whose CTDs also are known to engage DNA sufficiently tightly as it exits the nucleolytic active site that they wrap the duplex back through the enzyme to provide the transport strand in cis [27]. A more precise physical model that can account for how an extended DNA segment can writhe spatially to selectively engage specific regions of the CTD, as well as snake through the arms of a second bent DNA, will require future investigation.

Materials and Methods

Cloning and protein expression

Cloning of the full-length coding regions of E. coli ParC (1–752), ParE (1–630), and the ParC NTD (1–482) has been previously described [20]. The ParC CTD (498–752) was amplified from E. coli MG1655 K-12 genomic DNA and cloned into vector pSV272, which possesses an N-terminal hexahistidine (His6) tag followed by an MBP tag and a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavable site. Point mutations were introduced into the full-length ParC or the His6-MBP ParC CTD using QuikChange (Stratagene).

Proteins (except for the ParC NTD) were overexpressed in E. coli BL21codon-plus (DE3) RIL cells (Stratagene) at 37 °C. Protein expression was induced at 37 °C by adding 0.25–0.5 mM IPTG to 2×YT liquid media cultures after cells had grown to OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) = 0.3–0.5. After induction, cells were grown at 37 °C for an additional 3–4 h, centrifuged, resuspended in buffer A800 [10% (v/v) glycerol, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 800 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME), 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)], frozen drop-wise into liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C prior to purification.

Purification of E. coli ParE and ParC

For purification, cells were thawed, lysed by sonication, and centrifuged. Clarified lysates were applied to 5-mL HiTrap Ni2+ columns (GE), and the columns were washed extensively with buffer A800. The columns were washed further with A400 [10% (v/v) glycerol, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 400 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, 2 mM BME, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 mM PMSF]. Proteins were eluted in B400 [10% (v/v) glycerol, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 400 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, 2 mM BME, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 mM PMSF] and concentrated by centrifugation (Millipore Amicon Ultra 30). To remove His6 tags, we dialyzed the proteins overnight in Slide-A-Lyzer cassettes (Thermo Scientific, 10K MWCO), at 4 °C against A400 in the presence of 1 mg of His6 TEV protease (MacroLab, University of California, Berkeley). Following TEV cleavage, the proteins were run over HiTrap Ni2+ columns equilibrated in A400 to isolate tagless proteins and remove the TEV protease. All proteins were concentrated by centrifugation (Millipore Amicon Ultra 30) and applied to an S-300 gel-filtration column (GE) equilibrated and run in SE buffer [10% (v/v) glyercol, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 400 mM KCl, 2 mM BME, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 mM PMSF]. Peak fractions were collected and concentrated by centrifugation (Millipore Amicon Ultra 30). Protein purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE/Coomassie staining, and protein concentration was measured by absorbance at 280 nm. Proteins were flash frozen in a final buffer containing 30% (v/v) glycerol, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 400 mM KCl, and 2 mM BME, and stored at −80 °C.

Purification of His6-MBP ParC CTD

Cells suspended and frozen in buffer A800 were thawed, sonicated, and centrifuged. Clarified lysate was applied to a 5-mL HiTrap Ni2+ column (GE) equilibrated in buffer A800. The column was washed in buffer A800 followed by buffer A400. Protein was eluted from the Ni2+ column directly onto a 10-mL amylose column in B400 (New England Biolabs). The amylose column was then washed in buffer C [10% (v/v) glycerol, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.9, 400 mM NaCl, 2 mM BME, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 mM PMSF] and proteins were eluted from the amylose column in buffer D [10% (v/v) glycerol, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.9, 400 mM NaCl, 2 mM BME, 100 mM maltose, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 mM PMSF]. Peak fractions were collected and concentrated by centrifugal filtration (Millipore Amicon Ultra 30). Protein was then run over an S-300 size-exclusion column equilibrated and run in SE buffer. Peak fractions were collected, concentrated by centrifugation (Millipore Amicon Ultra 30), flash frozen, and stored at −80 °C. The protein was stored in a final buffer containing 30% (v/v) glycerol, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 400 mM KCl, and 2 mM BME. Protein purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE/Coomassie staining, and protein concentration was measured by absorbance at 280 nm.

Expression and purification of the ParC NTD

The ParC NTD was overexpressed in E. coli BL21codon-plus (DE3) RIL cells (Stratagene) from a fresh transformation. Protein expression was induced at 30 °C by adding 0.3 mM IPTG to 1-L 2×YT liquid media cultures after cells had grown to OD600 = 0.3–0.5. Cells were grown for six more hours, resuspended in A800, drop frozen, and stored at −80 °C.

For purification of the ParC NTD, cells were thawed, lysed by sonication, and centrifuged. The clarified lysate was applied to a 5-mL HiTrap Ni2+ column (GE), and the column was washed extensively with a buffer containing 800 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM BME, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 mM PMSF. The column was then washed in buffer A200 [200 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM BME, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 mM PMSF]. The protein was eluted in a buffer containing 200 mM NaCl, 400 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM BME, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 mM PMSF and concentrated by centrifugation (Millipore Amicon Ultra 30). To remove the His6 tag, we dialyzed the protein overnight in Slide-A-Lyzer cassettes (Thermo Scientific, 10K MWCO), at 4 °C against A200 in the presence of 1 mg of His6 TEV protease. Following TEV cleavage, the protein was run over a HiTrap Ni2+ column equilibrated in A200 to isolate tagless proteins and remove the tagged TEV protease. The protein was concentrated by centrifugation (Millipore Amicon Ultra 30) and then applied to an S-300 gel filtration column (GE) equilibrated and run in a buffer containing 800 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM BME, 1 μg/mL pepstatin A, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, and 1 mM PMSF. Peak fractions were collected and concentrated by centrifugation (Millipore Amicon Ultra 30). The ParC NTD was flash frozen in a final buffer containing 30% (v/v) glycerol, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 400 mM KCl, and 2 mM BME, and stored at −80 °C. Protein purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE/Coomassie staining, and protein concentration was measured by absorbance at 280 nm.

Circular dichroism

Aliquots of full-length WT and mutant ParCs were thawed and dialyzed overnight at 4 °C against a buffer containing 200 mM KCl and 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9. After dialysis, the proteins were diluted to a final concentration of 0.25 mg/mL. CD spectra were taken at 25 °C and 37 °C with an Aviv model 410 Circular Dichroism Spectrophotometer in a 1-cm pathlength cuvette. Data were obtained from 250 to 200 nm, at 1-nm intervals. Each point is averaged over 5 s and each read was performed three times.

Preparation of supercoiled plasmid substrates and kDNA

Negatively supercoiled pSG483 (2927 bp), a pBlue-script SK derivative, was prepared from E. coli using a maxiprep kit (Machery-Nagel). To produce positively supercoiled pSG483, we treated negatively supercoiled pSG483 with Archaeoglobus fulgidus reverse gyrase following the method of Rodriguez [52]. kDNA from Crithidia fasciculata was purified as described by Shapiro et al. [53].

DNA supercoil relaxation assays and decatenation assays

The topo IV holoenzyme was formed on ice by incubating equimolar amounts of ParE and ParC (tetramer final concentration ~20–40 μM) for 10 min. Topo IV was then serially diluted in protein dilution buffer [2- to 3-fold steps in 150 mM potassium glutamate, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 6 mM MgCl2] and mixed with supercoiled DNA (7.9 nM final concentration) or kDNA (9.2 nM). The final reaction (20 μL) contained 30 mM potassium glutamate, 1% (v/v) glycerol, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM spermidine, 10 μg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 6 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM ATP, pH 7.5. For enzyme titration experiments, samples were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min after addition of ATP. The reactions were quenched by the addition of 2% (w/v) SDS and 20 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), pH 8.0 (final concentrations). Sucrose loading dye was added to the samples, which were then run on 1% (w/v) TAE agarose gels (40 mM sodium acetate, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) for 6–15 h at 2–2.5 V/cm. For visualization, gels were stained with 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide in 1% TAE buffer for 20 min and then destained in 1% TAE buffer for 30 min and exposed to UV transillumination. For time-course experiments, the reaction volume was increased to 180 μL. After the addition of ATP, samples were incubated at 37 °C. For each time point, 18 μL of the sample was removed and quenched by the addition of 2% (w/v) SDS and 20 mM EDTA, pH 8.0 (final concentrations). All other experimental parameters are identical to those utilized in the enzyme titration experiments. All gel-based experiments were performed at least three times with at least two different protein preparations for each ParC construct.

DNA binding experiments with the isolated His6-MBP ParC CTD

A randomly generated, 20-bp annealed duplex oligonucleotide was purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) and resuspended in water (50% G/C content, Tm = 50 °C, 5′-|56-FAM|-TTAGGCGTAAACCTCCATGC-3′ and 5′-GCATCCGCATTTACGCCTAA-3′, where |56-FAM| indicates the position of a carboxyfluorescein dye used for analysis). A short DNA was chosen to prevent binding of the multiple CTDs to a single duplex. All proteins were diluted on ice in protein dilution buffer A [150 mM potassium glutamate, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 50 μg/mL BSA]. The assay (80 μL) contained 16 μL of the diluted His6-MBP ParC CTD protein and 20 nM of the fluorescently labeled 20mer oligonucleotide. DNA and proteins were initially incubated on ice in the dark for 10 min, after which they were diluted to the final assay volume and kept at room temperature in the dark for 10–15 min [final assay conditions: 2.4 mM DTT, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM MgCl2, 50 μg/mL BSA, and 30 mM potassium glutamate]. Measurements were made with a Perkin Elmer Victor 3V 1420 multilabel plate reader at 535 nm. Data points are the average of three independent experiments and all points are normalized to wells where protein is absent. Data were plotted in GraphPad Prism Version 5 using the following single-site binding model equation:

where Bmax is the maximum specific binding, [L] is the DNA concentration, [P] is the concentration of the His6-MBP ParC CTD, and Kd,app is the apparent dissociation constant for His6-MBP ParC CTD and DNA [54,55].

DNA binding experiments with the topo IV holoenzyme

The topo IV holoenzyme was reconstituted as described for the DNA relaxation and decatenation assays. A 45-bp annealed duplex DNA with a strong topoisomerase II binding site was obtained from IDT and resuspended in water [56]. The sequences for the two strands were 5′-GCCTATCCGAGGATGACGATGCGCGCATCGTCATA-CAGCGAATGG-3′ and 5′-|56-FAM|-CCATTCGCTGTAT-GACGATGCGCGCATCGTCATCCTCGGATAGGC-3′.

A longer DNA was chosen for this study because the central DNA binding and cleavage core of type IIA topoisomerases footprints an ~34-bp span of the duplex [57]; the DNA was extended slightly further to match the oligo used for obtaining a robust FRET signal in our recent DNA bending studies [45]. To conduct the assay, we titrated topo IV on ice and mixed it with DNA (20 nM final) for 10 min prior to further dilution. The final reaction (80 μL) contained 25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 20 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 100 μg/mL BSA. Reactions were incubated at room temperature for 15 min prior to taking measurements. Measurements were made with a Perkin Elmer Victor 3V 1420 multilabel plate reader at 535 nm. Data were plotted in Prism GraphPad Version 5 and fit to the single-site binding model described earlier.

FRET-based DNA bending experiments

A 45mer duplex DNA of identical sequence to that employed for the binding assays was used to conduct the bending experiments. One strand contained a 5′-Cy5 dye (5′-GCCTATCCGAGGATGACGATGCGCGCATCGTCA-TACAGCGAATGG-3′) while the other bore a 5′-Cy3 label (5′-CCATTCGCTGTATGACGATGCGCGCATCGT-CATCCTCGGATAGGC-3′).

For the assay, 0–1000 nM topo IV was titrated against 100 nM labeled DNA in 14-μL reactions containing 25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 20 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 100 μg/mL BSA. Emission spectra of Cy5 (545–720 nm) were measured after excitation of Cy3 by 530 nm using a Fluoromax fluorometer 4 (HORIBA Jobin Yvon, Edison, NJ, USA). The loss of emission signal with topo IV constructs containing either the blade 1 ParC mutant or the ParC NTD alone reflects a loss of the ability of the enzyme to bend DNA [40,45].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank past and present Berger Lab members for insightful discussions and advice. We also thank Katie Hart and the Marqusee Lab (University of California, Berkeley) for assistance with CD experiments. This work was supported by a National Science Foundation Predoctoral Fellowship to S.M.V. and the National Cancer Institute (CA077373) to J.M.B.

Abbreviations used

- Topo IV

topoisomerase IV

- G-segment

gate segment

- T-segment

transfer segment

- CTD

C-terminal domain

- NTD

N-terminal domain

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- kDNA

kinetoplast DNA

- BME

β-mercaptoethanol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- 56-FAM

carboxyfluorescein

- His6

hexahistidine

- MBP

maltose binding protein

- TEV

tobacco etch virus

- WT

wild type

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

Footnotes

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2013.04.033

References

- 1.Roca J, Wang JC. The capture of a DNA double helix by an ATP-dependent protein clamp: a key step in DNA transport by type II DNA topoisomerases. Cell. 1992;71:833–40. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90558-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roca J, Wang JC. DNA transport by a type II DNA topoisomerase: evidence in favor of a two-gate mechanism. Cell. 1994;77:609–16. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown PO, Cozzarelli NR. A sign inversion mechanism for enzymatic supercoiling of DNA. Science. 1979;206:1081–3. doi: 10.1126/science.227059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu L, Liu C. Type II DNA topoisomerases: enzymes that can unknot a topologically knotted DNA molecule via a reversible double-strand break. Cell. 1980;19:697–707. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(80)80046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vos SM, Tretter EM, Schmidt BH, Berger JM. All tangled up: how cells direct, manage and exploit topoisomerase function. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:827–41. doi: 10.1038/nrm3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gellert M, Mizuuchi K, O’Dea MH, Nash HA. DNA gyrase: an enzyme that introduces superhelical turns into DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3872–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gadelle D, Filée J, Buhler C, Forterre P. Phylogenomics of type II DNA topoisomerases. BioEssays. 2003;25:232–42. doi: 10.1002/bies.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato J, Nishimura Y, Imamura R, Niki H, Hiraga S, Suzuki H. New topoisomerase essential for chromosome segregation in E. coli. Cell. 1990;63:393–404. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90172-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zechiedrich EL, Khodursky AB, Bachellier S, Schneider R, Chen D, Lilley DM, et al. Roles of topoisomerases in maintaining steady-state DNA supercoiling in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8103–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone MD, Bryant Z, Crisona NJ, Smith SB, Vologodskii A, Bustamante C, et al. Chirality sensing by Escherichia coli topoisomerase IV and the mechanism of type II topoisomerases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8654–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133178100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crisona NJ, Strick TR, Bensimon D, Croquette V, Cozzarelli NR. Preferential relaxation of positively supercoiled DNA by E. coli topoisomerase IV in single-molecule and ensemble measurements. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2881–92. doi: 10.1101/gad.838900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ullsperger C, Cozzarelli NR. Contrasting enzymatic activities of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31549–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charvin G, Bensimon D, Croquette V. Single-molecule study of DNA unlinking by eukaryotic and prokaryotic type-II topoisomerases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9820–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1631550100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neuman KC, Charvin G, Bensimon D, Croquette V. Mechanisms of chiral discrimination by topoisomerase IV. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6986–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900574106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zechiedrich E, Cozzarelli N. Roles of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase in DNA unlinking during replication in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2859. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Lano W, editor. PyMOL. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Workman CT, Yin Y, Corcoran DL, Ideker T, Stormo GD, Benos PV. enoLOGOS: a versatile web tool for energy normalized sequence logos. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W389–92. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corbett KD, Shultzaberger RK, Berger JM. The C-terminal domain of DNA gyrase A adopts a DNA-bending beta-pinwheel fold. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7293–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401595101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh TJ, Farh L, Huang WM, Chan NL. Structure of the topoisomerase IV C-terminal domain: a broken beta-propeller implies a role as geometry facilitator in catalysis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55587–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corbett KD, Schoeffler AJ, Thomsen ND, Berger JM. The structural basis for substrate specificity in DNA topoisomerase IV. J Mol Biol. 2005;351:545–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reece RJ, Maxwell A. The C-terminal domain of the Escherichia coli DNA gyrase A subunit is a DNA-binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1399–405. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.7.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tretter EM, Berger JM. Mechanisms for defining supercoiling set point of DNA gyrase orthologs: I. A nonconserved acidic C-terminal tail modulates Escherichia coli gyrase activity. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:18636–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.345678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh TJ, Yen TJ, Lin TS, Chang HT, Huang SY, Hsu CH, et al. Twisting of the DNA-binding surface by a beta-strand-bearing proline modulates DNA gyrase activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:4173–81. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward D, Newton A. Requirement of topoisomerase IV parC and parE genes for cell cycle progression and developmental regulation in Caulobacter crescentus. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:897–910. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6242005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lanz MA, Klostermeier D. The GyrA-box determines the geometry of DNA bound to gyrase and couples DNA binding to the nucleotide cycle. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:10893–903. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kramlinger VM, Hiasa H. The “GyrA-box” is required for the ability of DNA gyrase to wrap DNA and catalyze the supercoiling reaction. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3738–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kampranis SC, Maxwell A. Conversion of DNA gyrase into a conventional type II topoisomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14416–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tretter EM, Lerman JC, Berger JM. A naturally chimeric type IIA topoisomerase in Aquifex aeolicus highlights an evolutionary path for the emergence of functional paralogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:22055–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012938107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruthenburg AJ, Graybosch DM, Huetsch JC, Verdine GL. A superhelical spiral in the Escherichia coli DNA gyrase A C-terminal domain imparts unidirectional supercoiling bias. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:26177–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayama R, Marians KJ. Physical and functional interaction between the condensin MukB and the decatenase topoisomerase IV in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18826–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008140107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayama R, Bahng S, Karasu ME, Marians KJ. The MukB-ParC interaction affects intramolecular, not intermolecular, activities of topoisomerase IV. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:7653–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.418087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugisaki H, Ray DS. DNA sequence of Crithidia fasciculata kinetoplast minicircles. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1987;23:253–63. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(87)90032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng H, Marians KJ. Escherichia coli topoisomerase IV. Purification, characterization, subunit structure, and subunit interactions. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24481–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nurse P, Bahng S, Mossessova E, Marians KJ. Mutational analysis of Escherichia coli topoisomerase IV. II. ATPase negative mutants of parE induce hyper-DNA cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4104–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson VE, Gootz T, Osheroff N. Topoisomerase IV catalysis and the mechanism of quinolone action. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17879–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marini JC, Miller KG, Englund PT. Decatenation of kinetoplast DNA by topoisomerases. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:4976–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vologodskii AV, Zhang W, Rybenkov VV, Podtelezhnikov AA, Subramanian D, Griffith JD, et al. Mechanism of topology simplification by type II DNA topoisomerases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061029098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dong KC, Berger JM. Structural basis for gate-DNA recognition and bending by type IIA topoisomerases. Nature. 2007;450:1201–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee S, Jung SR, Heo K, Byl JA, Deweese JE, Osheroff N, et al. DNA cleavage and opening reactions of human topoisomerase IIalpha are regulated via Mg2+-mediated dynamic bending of gate-DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2925–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115704109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hardin AH, Sarkar SK, Seol Y, Liou GF, Osheroff N, Neuman KC. Direct measurement of DNA bending by type IIA topoisomerases: implications for non-equilibrium topology simplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:5729–43. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wohlkonig A, Chan PF, Fosberry AP, Homes P, Huang J, Kranz M, et al. Structural basis of quinolone inhibition of type IIA topoisomerases and target-mediated resistance. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1152–3. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wendorff TJ, Schmidt BH, Heslop P, Austin CA, Berger JM. The structure of DNA-bound human topoisomerase II alpha: conformational mechanisms for coordinating inter-subunit interactions with DNA cleavage. J Mol Biol. 2012;424:109–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt B, Burgin A, Deweese J, Osheroff N, Berger J. A novel and unified two-metal mechanism for DNA cleavage by type II and IA topoisomerases. Nature. 2010;465:641–4. doi: 10.1038/nature08974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laponogov I, Pan XS, Veselkov DA, McAuley KE, Fisher LM, Sanderson MR. Structural basis of gate-DNA breakage and resealing by type II topoisomerases. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee I, Dong KC, Berger JM. The role of DNA bending in type IIA topoisomerase function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:5444–56. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt BH, Osheroff N, Berger JM. Structure of a topoisomerase II-DNA-nucleotide complex reveals a new control mechanism for ATPase activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:1147–54. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bax BD, Chan PF, Eggleston DS, Fosberry A, Gentry DR, Gorrec F, et al. Type IIA topoisomerase inhibition by a new class of antibacterial agents. Nature. 2010;466:935–40. doi: 10.1038/nature09197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu CC, Li TK, Farh L, Lin LY, Lin TS, Yu YJ, et al. Structural basis of type II topoisomerase inhibition by the anticancer drug etoposide. Science. 2011;333:459–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1204117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baker NM, Weigand S, Maar-Mathias S, Mondragon A. Solution structures of DNA-bound gyrase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:755–66. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Costenaro L, Grossmann JG, Ebel C, Maxwell A. Small-angle X-ray scattering reveals the solution structure of the full-length DNA gyrase a subunit. Structure. 2005;13:287–96. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirchhausen T, Wang JC, Harrison SC. DNA gyrase and its complexes with DNA: direct observation by electron microscopy. Cell. 1985;41:933–43. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodriguez AC. Studies of a positive supercoiling machine. Nucleotide hydrolysis and a multifunctional “latch” in the mechanism of reverse gyrase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29865–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202853200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shapiro TA, Klein VA, Englund PT. Isolation of kinetoplast DNA. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;94:61–7. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-259-7:61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heyduk T, Lee JC. Application of fluorescence energy transfer and polarization to monitor Escherichia coli cAMP receptor protein and lac promoter interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1744–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Datta K, LiCata VJ. Thermodynamics of the binding of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase to primed-template DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5590–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mueller-Planitz F, Herschlag D. DNA topoisomerase II selects DNA cleavage sites based on reactivity rather than binding affinity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3764–73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peng H, Marians KJ. The interaction of Escherichia coli topoisomerase IV with DNA. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25286–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.25286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.