Abstract

Objective

To validate a Cardiometabolic Disease Staging (CMDS) system for assigning risk level for diabetes, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality.

Design, and Methods

Two large national cohorts, CARDIA and NHANES III, were used to validate CMDS. CMDS: Stage 0: metabolically healthy; Stage 1: 1 or 2 Metabolic Syndrome risk factors (other than IFG); Stage 2: IFG or IGT or Metabolic Syndrome (without IFG); Stage 3: 2 of 3 (IFG, IGT, and/or Metabolic Syndrome); Stage 4: T2DM/CVD.

Results

In the CARDIA study, compared with Stage 0 metabolically healthy subjects, adjusted risk for diabetes exponentially increased from Stage 1 (HR 2.83, 95% CI 1.76–4.55), to Stage 2 (HR 8.06, 95% CI 4.91–13.2), to Stage 3 (HR 23.5, 95% CI 13.7–40.1) (p for trend <0.001). In NHANES III, both cumulative incidence and multivariable adjusted hazard ratios markedly increased for both all-cause and CVD mortality with advancement of the risk stage from Stage 0 to 4. Adjustment for BMI minimally affected the risks for diabetes and all-cause/CVD mortality using CMDS.

Conclusion

CMDS can discriminate a wide range of risk for diabetes, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality independent of BMI, and should be studied as a risk assessment tool to guide interventions that prevent and treat cardiometabolic disease.

Introduction

The spectrum of cardiometabolic disease begins with insulin resistance, a trait that is expressed early in life, and then progresses to the clinically identifiable high-risk states of Metabolic Syndrome and prediabetes, and then to Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and cardiovascular disease (CVD). The consequences of cardiometabolic disease are severe. T2DM, which is epidemic in the United States (1) and worldwide (2), is associated with elevated risk for morbidity and mortality (3) and high social costs (1), and CVD remains the leading cause of death in Western societies. To stem the increasing prevalence of T2DM and to reduce CVD risks, it will be necessary to identify high-risk individuals early in the progression of cardiometabolic disease, and intervene with effective strategies for disease prevention.

Obesity can exacerbate insulin resistance and impel cardiometabolic disease progression. However, the relationship between generalized obesity, as measured by the body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), and cardiometabolic disease is complex. For example, insulin resistance exists largely independent of BMI (4), and BMI is a poor predictor of CVD compared with measures of fat distribution such as waist/hip ratio (5). Also, up to 30% of obese individuals (i.e., BMI ≥ 30) are relatively insulin sensitive, giving rise to the term ‘healthy obese’ (6). Thus, obesity is neither necessary nor sufficient to explain the pathophysiology underlying cardiometabolic disease. Even so, weight loss can be used as a therapeutic tool. Weight loss whether achieved by lifestyle intervention (7), medications (8), or bariatric surgery (9) can prevent progression to T2DM in high risk individuals, ameliorate dyslipidemia, lower blood pressures, and improve glucose tolerance.

Prior to 2012, clinicians employed lifestyle modification and a limited number of modestly effective medications in efforts to combat obesity, with bariatric surgery reserved for more severe or refractory cases (10). In the summer of 2012, the FDA approved two new medications, phentermine plus topiramate extended release (phentermine/topiramate ER) and locaserin, to be used as adjuncts to lifestyle modification in the treatment of overweight and obesity. The availability of these safe and effective weight loss drugs represents a landmark development in obesity pharmacotherapy, and enables an evidenced-based medical model that incorporates more effective and comprehensive application of lifestyle, drug, and surgical treatment options (11).

In developing a medical model for obesity management, it is important to consider that any intervention entails risk, and treatment must be targeted to those patients who will derive the greatest benefits from the intervention to optimally balance benefit and risk. Many treatment algorithms for obesity are based on BMI level, which determines thresholds for indications pertaining to pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery (10,12). For the reasons discussed above, BMI is a poor indicator for use in this context; rather, patients who will benefit most from obesity treatment have obesity-related complications that can be ameliorated by weight loss (10,11,13). Given that medications and surgical procedures have inherent risks for patients and increase the cost of health care delivery, it is important to develop a staging system that identifies patients who can most benefit from weight loss interventions, based on complications rather than BMI per se.

In the current manuscript, we have validated a system for evaluating the stage and severity of cardiometabolic disease. Our studies employed the NHANES III-linked mortality file (14) for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and longitudinal data from the national CARDIA study for incident Type 2 diabetes (15). We have defined distinct categories using readily available clinical information that assess future risk for both T2DM and CVD mortality, and have called this system Cardiometabolic Disease Staging (CMDS). The studies have provided insight regarding risk progression in cardiometabolic disease, and have validated a tool that can be used by clinicians to identify treatment modality and intensity for obesity based on cardiometabolic disease severity. Such an approach may be useful to optimize the benefit/risk ratio for interventions, and achieve the best outcomes by aligning specific therapy with those patients who will derive the greatest benefit.

Methods

Risk staging system

We propose a risk classification system using clinical parameters pertinent to diagnosis of the Metabolic Syndrome from Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) (3), and prediabetes/diabetes using fasting and 2-hour OGTT glucose values according to the American Diabetes Association. The Cardiometabolic Disease Staging (CMDS) system is shown in Table 1, and was based on results from the epidemiological and physiological literature: (i) Stage 0 includes individuals who are relatively insulin sensitive, free of any cardiometabolic disease risk factors, and without increased risk of diabetes or CVD (6), referred to as ‘metabolically healthy obese’ (16); (ii) Stage 1 includes patients who meet only 1 or 2 ATPIII criteria (waist circumference, elevated blood pressure, triglycerides, and HDL-C) but who are still at increased risk of future T2DM and CVD (17,18); (iii) Stage 2 is comprised of patients who meet criteria for either Metabolic Syndrome or impaired fasting glucose (IFG) alone or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) alone; (iv) Stage 3 includes patients with any 2 out of 3 of these conditions (Metabolic Syndrome, IFG, and IGT) who exhibit approximately double the risk for future diabetes compared with those who have either condition alone (18,19); finally, (v) Stage 4 subjects have diagnoses of T2DM and/or CVD since patients with previous myocardial infarction and T2DM patients without a previous myocardial infarction have equal risk of future coronary heart disease mortality (20). Thus, the CMDS staging system was rationally constructed based on multiple published observations. Then, we proceeded to empirically validate the predictive value of CMDS for differential risk of future T2DM and mortality using data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) cohorts.

Table 1.

The Cardiometabolic Disease Staging System (CMDS)

| The Cardiometabolic Disease Staging System (CMDS) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Stage | Descriptor | Criteria |

| Stage 0 | Metabolically Healthy | No risk factors |

| Stage 1 | One or Two Risk Factors | Have one or two of the following risk factors:

|

| Stage 2 | Metabolic Syndrome or Prediabetes | Have only one of the following three conditions in isolation

|

| Stage 3 | Metabolic Syndrome+ Prediabetes | Have any two of the following three conditions:

|

| Stage 4 | T2DM and/or CVD | Have Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) and/or Cardiovascular Disease (CVD):

|

CARDIA study

Data from the CARDIA study was used to validate CMDS against future risk for T2DM. The CARDIA study (15) is a large, ongoing cohort study, which began in 1985–1986. CARDIA recruited 5,115 young black and white adults (46% male) aged 18–30 years from four sites in the U.S., including Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; and Oakland, CA. Oral glucose tolerance tests with measurement of the 2-hour glucose concentration were not initiated until CARDIA year 10, and, for this reason, year 10 served as baseline year for the current study, with follow-up to year 20. The current analyses included 3,315 participants with valid 2-hour glucose measures at year 10 after excluding pregnant women, participants with diabetes or cardiovascular diseases, and participants without enough information for assignment to risk category. Site institutional review committee approval and informed consent were obtained.

Measures

BMI (kg/m2) was computed and standardized blood pressures were obtained by sphygmomanometer. Standing waist circumference was measured at a level laterally that is midway between the iliac crest and the lowest lateral portion of the rib cage and anteriorly midway between the xiphoid process of the sternum and the umbilicus. Serum glucose and plasma lipids were assayed using the fasting blood sample. 75-gram oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT) were performed at the year 10 and year 20 examinations. Each participant was asked to fast for 12 h; however, participants were asked to report the time of their last meal, so the length of the fasting period could be calculated. Incident diabetes was defined as participants reporting a diagnosis of diabetes, or having a documented fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dl, and/or 2-hour glucose ≥200 mg/dl.

NHANES III

Data from NHANES III-linked mortality file was used to validate CMDS against mortality risk. NHANES III is a cross-sectional survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) during 1988–1994, using a complex, stratified, multistage probability sample to represent the civilian, non-institutionalized, US population. The study was approved by the NCHS Institutional Review Board, and all adult participants provided written informed consent. Information on mortality from public-use mortality files was linked to the National Death Index, with follow-up through Dec. 31, 2006. Males and non-pregnant females aged 40–74 years who had been randomized to the morning session of the mobile examination center and completed an oral glucose test were considered eligible. Participants without adequate information to assess risk staging classification were excluded.

Measures

Subjects were grouped into three BMI categories: ≥30 (obese), 25–29.9 (overweight), and <25 (normal). Race/ethnicity was self-reported as Non-Hispanic White (NHW), Non-Hispanic Black (NHB), Mexican American (MEX), other Hispanic, and other. Standardized blood pressures were obtained by sphygmomanometer. Standing waist circumference was measured just above the uppermost lateral border of the ilium. Plasma glucose and serum lipids were measured as delineated in the NHANES Laboratory Procedures Manual (21). The method of probabilistic matching (22) was used to link NHANES III participants with the National Death Index to ascertain vital status and mortality through December 31, 2006. It was found that 96.1% of the deceased participants and 99.4% of the living participants were correctly classified, using identical matching methodology applied to the NHANES I Epidemiological Follow-up Study for validation purposes (22).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute). A 2-sided P <0.05 was determined to be statistically significant. Cox regression models were used to examine risk stage in relation to incident diabetes using CARDIA data. Follow-up time was calculated as the difference between the baseline set at year 10 of the CARDIA study and the year when diabetes was first identified, examination year 20, or the year a participant was censored, whichever came first. Multivariable adjusted Cox model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, race, income, education, current smoker, current alcohol drinker and parent diabetes history. Model 2 was additionally adjusted for BMI.

All analyses for NHANES data took into account differential probabilities of selection and the complex sample design by using sample weights, following NHANES Analytic and Reporting Guidelines. Standard errors were calculated using Taylor series linearization. We analyzed all-cause and CVD mortality using Kaplan-Meier survival curve estimates and Cox regression models. Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, race, income, education, current smoker, and current alcohol drinker. Model 2 was further adjusted for BMI. Sensitivity analysis was conducted after excluding participants with cancer, CVD or hepatitis C in the full multivariable adjusted model.

We examined the relationship between the risk system and incident diabetes, or mortality, in all study participants and in those subjects who were overweight and obese. The proportional hazards assumption for cox models was assessed using Schoenfeld residuals, and no violation was found.

Results

Incident diabetes

The CARDIA study was used to assess incident diabetes, and baseline characteristics (i.e., CARDIA year 10 examination) are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Participants in CARDIA were relatively young with a median age of 35 years. 29.3% of overweight or obese participants were metabolically healthy (i.e., no risk factors; Stage 0. supplemental Table).

Table 2.

Sample size for the CARDIA study and NHANES-linked mortality file

| number (weighted %) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk level | ||||||

| All | Stage 0 | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | |

| NHANES-linked mortality file | ||||||

| All | 3964 (100.0) | 390 (13.7) | 892 (24.4) | 992 (25.7) | 673 (16.3) | 1017 (20.0) |

| Men | 1952 (49.0) | 191 (6.2) | 379 (10.3) | 528 (13.0) | 326 (8.4) | 528 (11.1) |

| Women | 2012 (51.0) | 199 (7.4) | 513 (14.1) | 464 (12.7) | 347 (7.9) | 489 (8.9) |

| NHW | 1792 (79.8) | 204 (11.3) | 401 (19.5) | 462 (20.6) | 316 (12.9) | 409 (15.5) |

| NHB | 1015 (9.1) | 99 (1.1) | 272 (2.6) | 251 (2.3) | 130 (1.1) | 263 (2.1) |

| MEX | 989 (3.7) | 65 (0.3) | 181 (0.8) | 238 (0.9) | 198 (0.8) | 307 (1.0) |

| Alive | 2952 (79.7) | 337 (12.4) | 734 (21.0) | 781 (21.4) | 499 (12.3) | 601 (12.7) |

| Deceased | 1012 (20.3) | 53 (1.3) | 158 (3.5) | 211 (4.3) | 174 (3.9) | 416 (7.3) |

| No CVD death | 3560 (92.6) | 378 (13.5) | 843 (23.5) | 910 (24.0) | 616 (15.2) | 813 (16.4) |

| CVD death | 404 (7.4) | 12 (0.1) | 49 (1.0) | 82 (1.7) | 57 (1.1) | 204 (3.6) |

| The CARDIA Study | ||||||

| All | 3315 | 1537 | 1364 | 335 | 79 | |

| Men | 1495 | 692 | 584 | 178 | 41 | |

| Women | 1820 | 845 | 780 | 157 | 38 | |

| Blacks | 1530 | 629 | 689 | 168 | 44 | |

| Whites | 1785 | 908 | 675 | 167 | 35 | |

| No events | 3112 | 1509 | 1283 | 274 | 46 | |

| Incident diabetes | 203 | 28 | 81 | 61 | 33 | |

For NHANES III-linked mortality file, participants aged 40 to 74 years with valid 2-hour glucose measures and information for assigning risk category were included. Pregnant women were excluded. Weighted %: sample weights were used to calculated weighted percent.

For the CARDIA study, inclusion is participants with valid 2-hour glucose measures at year 10 and information for assigning risk category. Pregnant women and participants with diabetes or cardiovascular diseases at year 10 were excluded.

NHW: Non-Hispanic White; NHB: Non-Hispanic Black; MEX: Mexican American; CVD: cardiovascular disease.

Table 3.

Characteristics of participants from the CARDIA study and NHANES-linked mortality file

| Mean or % (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|

| CARDIA Study | NHANES | |

| Age (year) | 35.0 (34.9–35.1) | 54.2 (53.8–54.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.1 (26.9–27.3) | 27.4 (27.2–27.7) |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 85.1 (84.6–85.5) | 96.0 (95.3–96.6) |

| SBP (mmHg) | 109.6 (109.2–110.0) | 123.4 (122.6–124.2) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 72.3 (72.0–72.6) | 73.9 (73.5–74.4) |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 50.5 (50.0–51.0) | 50.2 (49.5–50.9) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 177.7 (176.5–178.9) | 216.1 (214.2–218.0) |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 89.7 (87.4–92.1) | 155.5 (148.3–162.7) |

| Higher Education (%) | 72.3 (70.8–73.8) | 40.3 (37.9–42.6) |

| Non Smoker (%) | 59.3 (57.6–61.0) | 39.1 (36.8–41.4) |

| Current Smoker (%) | 23.7 (22.3–25.2) | 24.9 (22.9–26.9) |

| Obesity (%) | 24.2 (22.7–25.6) | 27.5 (25.5–29.6) |

| Elevated Blood Pressure (%) | 13.0 (11.9–14.2) | 48.4 (46.0–50.7) |

| Reduced HDL-Cholesterol (%) | 36.0 (34.4–37.7) | 41.0 (38.7–43.4) |

| Elevated Triglycerides (%) | 11.6 (10.5–12.7) | 39.7 (37.4–42.0) |

| High Waist Circumference (%) | 21.3 (19.9–22.7) | 48.6 (46.3–51.0) |

| Elevated Total Cholesterol (%) | 22.6 (21.2–24.0) | 65.9 (63.7–68.2) |

BMI: body mass index; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HDL: high density lipoprotein; Higher Education: Have completed some college or higher education; Elevated Blood Pressure: (systolic ≥130 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥85 mmHg) or on anti-hypertensive medication; Reduced HDL cholesterol: <1.0 mmol/L or 40 mg/dL in men; <1.3 mmol/L or 50 mg/dL in women; or on medication; high waist circumference: ≥112 cm in men, ≥88 cm in women; Elevated Fasting Serum Triglycerides: ≥1.7 mmol/L or 150 mg/dL; or on medication; Elevated Total Cholesterol: ≥ 180 mg/dL or on medication.

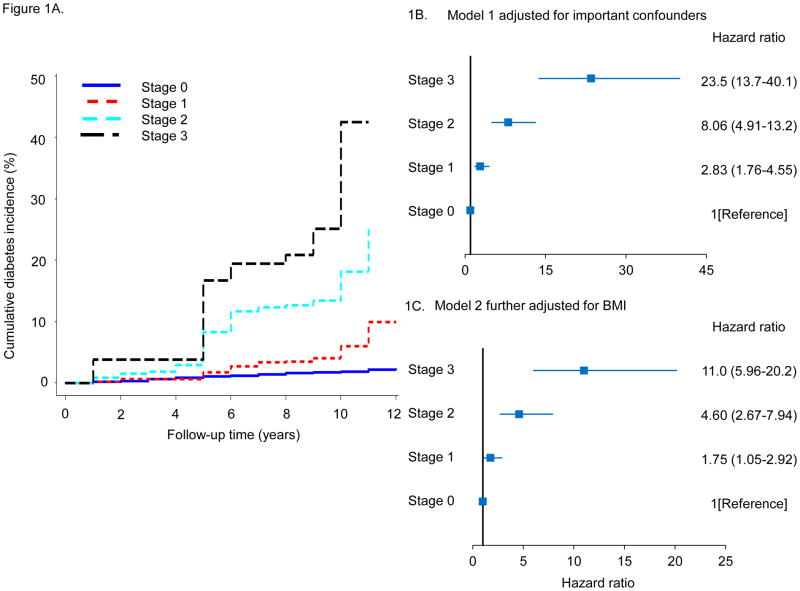

Over the 10-year follow-up period, there were 203 cases of newly-diagnosed diabetes resulting in an overall crude cumulative diabetes incidence of 6.1%. The cumulative diabetes incidence across risk levels Stages 0, 1, 2, and 3 were 1.8%, 5.9%, 18.2%, and 41.8%, respectively, shown in Figure 1A. Among overweight or obese participants, cumulative diabetes incidence was 8.9% overall, and across risk levels Stages 0, 1, 2, and 3 was 2.2%, 7.3%, 19.0%, and 41.0%, respectively (supplemental Figure 2). Clearly, patients categorized in Stage 0 (metabolically healthy) exhibited little tendency to progress to diabetes, while cumulative diabetes incidence rose at progressively higher rates as the risk stage was advanced from Stage 1 to Stage 3. The impact of risk stage on diabetes incidence was similar in both genders and in Whites and Blacks (supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A. Cumulative diabetes incidence according to risk staging system. B, C. Adjusted hazard ratios for incident diabetes. Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, income, education, current smoker, current alcohol drinker and parent diabetes history. Model 2 additionally adjusted for BMI.

In the same manner, multivariable adjusted hazard ratios (HR) for diabetes increased as a function of advancing CMDS as shown in Figure 1B. Compared with Stage 0 metabolically healthy subjects, adjusted risk for diabetes exponentially increased from Stage 1 (HR 2.83, 95% CI 1.76–4.55), to Stage 2 (HR 8.06, 95% CI 4.91–13.2), to Stage 3 (HR 23.5, 95% CI 13.7–40.1) (p for trend <0.001). Even after adjusting for BMI in Figure 1C, hazard ratios increased as a function of risk stage with statistically significant higher risk in Stage 1 (HR 1.75, 95% CI 1.05–2.92), Stage 2 (HR 4.60, 95% CI 2.67–7.94), and Stage 3 (HR 11.0, 95% CI 5.96–20.2), although the magnitude of the risk increments were reduced. Adjusted hazard ratios for incident diabetes also increased with higher stage when only overweight or obese participants were included in the analysis (supplemental Figure 3).

All-Cause and CVD Mortality

NHANES III was used to assess effects on all-cause and CVD mortality, and baseline characteristics are presented in Tables 2 and 3. The NHANES III sample was comprised of 3,964 subjects who reported that they had fasted for at least 8 hours prior to OGTT with sufficient information for risk staging. For the most part, participants were evenly distributed into risk category stages.

Over a median follow up of 173 months, there were 1,012 all-cause mortality cases ascertained, and the cumulative mortality rate was 14.7 per 1,000 person years. The cumulative mortality rates increased progressively with advancing CMDS risk stage (p <0.001 for trend), and were 6.5, 10.1, 11.9, 17.7, and 29.2 per 1,000 person years across risk Stages 0 to 4, respectively. In total, 404 cases of CVD-related deaths were reported. The CVD cumulative mortality rate was 5.4 per 1,000 person years overall, and also increased with risk stage (p <0.001 for trend), with 0.7, 2.8, 4.6, 4.9, and 14.3 per 1,000 person years across risk Stages 0 to 4, respectively.

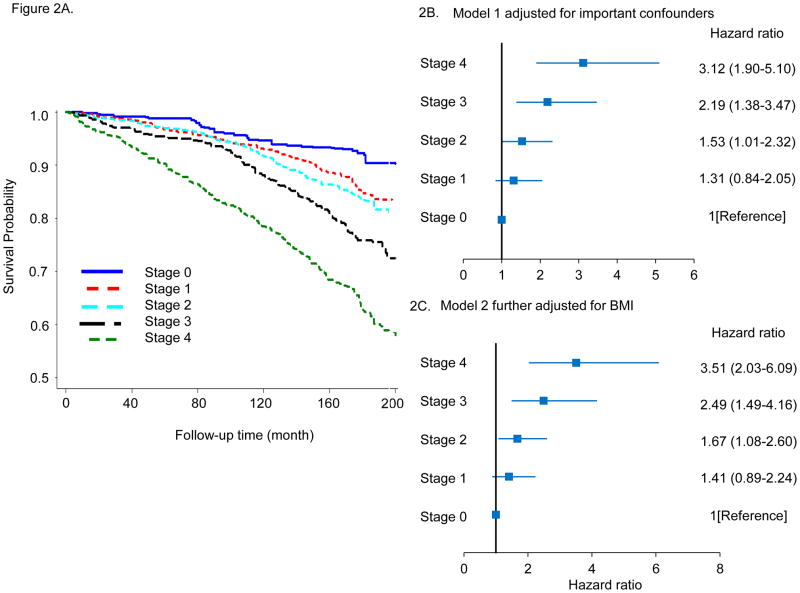

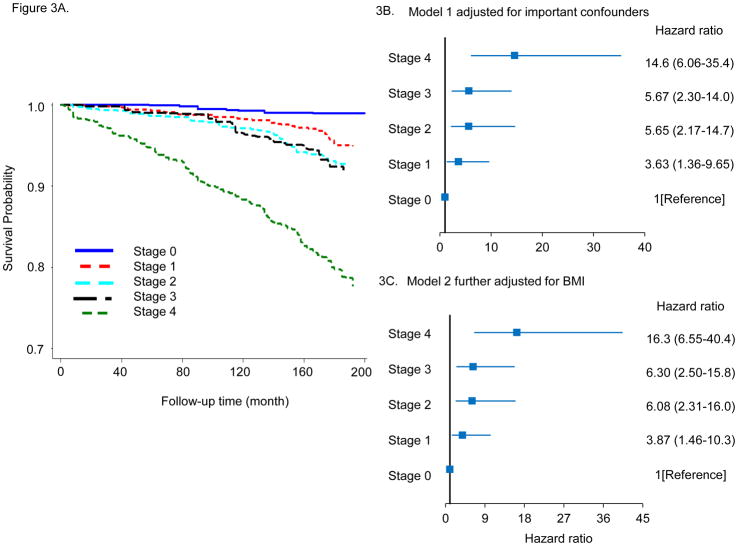

Kaplan–Meier plots for survival probability as a function of CMDS are shown in Figure 2A for all-cause mortality and in Figure 3A for CVD mortality. Both all-cause and CVD mortality increased with advancing risk stage in the entire cohort. This applied to both genders and all ethnic/racial subgroups (supplemental Figures 4 and 7), and when the analyses were confined to only those subjects who were overweight or obese at baseline (supplemental Figures 5 and 8). Similarly, multivariable adjusted hazard ratios (HR) for all-cause mortality are also clearly increased as a function of higher CMDS risk stage. In Figure 2B, with Stage 0 metabolically healthy subjects as the referent group, risk Stage 2 (HR 1.53, 95% CI 1.01–2.32), Stage 3 (HR 2.19, 95% CI 1.38–3.47), and Stage 4 (HR HR 3.12, 95% CI 1.90–5.10) were associated with progressively higher adjusted mortality hazard ratios. These results were similar after adjusting for baseline BMI (Figure 2C), or after excluding participants with CVD, cancer, or hepatitis C at baseline (data not shown). Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality also increased with higher stage in overweight or obese participants (supplemental Figure 6 ). Higher CMDS risk stages also predicted progressively greater risk for CVD mortality. In Figure 3B, Stage 1 (HR 3.63, 95% CI 1.36–9.65), Stage 2 (HR 5.65, 95% CI 2.17–14.7), Stage 3 (HR 5.67, 95% CI 2.30–14.08), and Stage 4 (HR 14.6, 95% CI 6.06–35.4) risk categories were associated with progressively higher adjusted hazard for CVD mortality with the lowest risk category Stage 0 serving as the referent group. We further observed that these results were similar after adjusting for BMI (Figure 3C), or after excluding participants with CVD, cancer or hepatitis C at baseline (data not shown). Adjusted hazard ratios for CVD mortality also increased with higher stage in overweight or obese participants (supplemental Figure 9).

Figure 2.

A. Kaplan-Meier plots for all-cause mortality according to risk staging system. B, C. Adjusted hazard ratios for all-cause mortality for risk staging system. Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, income, education, current smoker, current alcohol drinker, and model 2 additionally adjusted for BMI.

Figure 3.

A. Kaplan-Meier plots for CVD mortality according to risk staging system. B, C. Adjusted hazard ratios for CVD mortality for risk staging system. Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, income, education, current smoker, current alcohol drinker, and model 2 additionally adjusted for BMI.

Over a 10-year follow-up period in CARDIA, CMDS risk categories (Stage 0 to 3) discriminated ~20 fold differences in both the cumulative incidence (1.8% to 41.8%) and adjusted hazard ratios (1.0 to 23.5) for diabetes. In NHANES, CMDS stages 0 to 4 differentiated cumulative all-cause mortality rates ranging from 6.5 to 29.2 per 1,000 person years and adjusted hazard ratios from 1.0 to 3.12, and CVD mortality rates from 0.7 to 14.3 per 1,000 person years and adjusted hazard ratios from 1.0 to 14.6. Thus, CMDS is a strong predictor of incident diabetes, all-cause mortality, and CVD mortality,

Discussion

Cardiometabolic Disease Staging (CMDS)

We employed two large national cohorts, the CARDIA study for incident diabetes and the NHANES III linked mortality file for all-cause or CVD mortality, to validate a single risk staging system for both metabolic and vascular outcomes in cardiometabolic disease. We established 5 categories (Stages 0 to 4) for predicting increasing risk for future T2DM and CVD mortality using parameters from the physical examination and laboratory measurements that would be immediately available to clinicians. These parameters are relevant to the diagnosis of Metabolic Syndrome using ATPIII guidelines (23) and prediabetes as defined by the American Diabetes Association, and include waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, fasting and 2-hour OGTT blood glucose levels, triglycerides, and HDL-C. Our intention was to establish a clinically useful paradigm that will allow clinicians to identify modalities and intensities of therapy for prevention and treatment of cardiometabolic diseases in a manner that optimally balances benefit and risk. Our analyses clearly established that the 5 stages: (i) define populations at progressively increasing risk of future T2DM and all-cause and CVD mortality; (ii) partition populations with substantial numbers into all the various risk categories; (iii) serve to differentiate individuals over a wide range of disease risk; and (iv) maintain predictive value in both genders and across ethnic/racial subpopulations.

CMDS and the progression of cardiometabolic disease

The staging system that was validated in the current study confirms isolated observations but, moreover, provides an integrated understanding of the progressive nature and spectrum of cardiometabolic disease. For example, our data confirm that a significant proportion of overweight and obese individuals do not have cardiometabolic risk factors (6,24), equivalent to 19% of the CARDIA cohort, and now prospectively demonstrate that these individuals (i.e., Stage 0) also exhibit low rates of future diabetes and all-cause and CVD mortality. Our study also indicates that patients with 1 or 2 risk factors (Stage 1), who do not meet criteria for either Metabolic Syndrome or prediabetes, exhibit increased risk of future diabetes. This is consistent with the idea advanced by us (25) and others (17,18) that these diagnostic categories have high specificity but low sensitivity for identifying insulin resistance and cardiometabolic disease. Nevertheless, as cardiometabolic disease progresses to fulfillment of criteria for Metabolic Syndrome or IFG or IGT (Stage 2), patients are at increased risk for T2DM and CVD, and the risks approximately double when any two out of these three are present (Stage 3). This is consistent with previous data showing patients who meet criteria for both Metabolic Syndrome and prediabetes are at substantially higher risk for T2DM than patients who satisfy criteria for only one of these diagnoses (18–20). Stage 3 is identical to a high-risk state for future diabetes identified in a position statement from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, who recommend consideration of treatment with anti-diabetic drugs in these patients (26). Stage 4 is defined by the presence of overt T2DM and/or CVD, and reflects the high risk conferred by T2DM per se, even in the absence of known CVD, for future CVD events (20). Thus, in single cohorts of patients, our study demonstrates the full continuum of the cardiometabolic disease process, and elucidates the progressive severity of the disease using quantifiable clinical markers and manifestations relevant to both metabolic and vascular components.

BMI was not included in the determination of cardiometabolic disease risk since previous studies have indicated that insulin resistance exists largely independent of generalized adiposity (4,25,27) and that BMI is a poor independent predictor of CVD (28). The current data substantiate that BMI is weak independent predictor of future diabetes as well as all-cause and CVD mortality since adjustment for BMI did not substantially alter risks predicted by CMDS. Also, the predictive value of CMDS was unchanged when lean subjects were omitted and CMDS was applied only to overweight and obese individuals. In contrast, waist circumference is a strong independent predictor of insulin resistance and CVD (28,29), and is incorporated into CMDS. It is also apparent that HbA1c was not employed as a measure of diabetes or prediabetes, and this is because we (30) and others (31) have shown that HbA1c has low sensitivity for these diagnoses, and is responsible for a high false negative rate among patients diagnosed using the gold standard measures of fasting glucose combined with 2-hour glucose values. It is also important to consider that a high proportion of patients with prediabetes on the basis of IGT (i.e., elevated 2-hour OGTT only) will be missed when only fasting glucose and HbA1c are available, and that this proportion of missed diagnoses increases as a function of age (32). Elevated 2-hour glucose is also a strong independent risk factor for CVD (33). These data provide rationale for increased utilization of OGTT in evaluating cardiometabolic disease risk and for the incorporation of 2-hour glucose in CMDS.

Application of CMDS

Thus, we have validated a single staging system for cardiometabolic disease that can be used to estimate risk for both T2DM and all-cause and CVD mortality. CMDS should be studied as a tool to optimize the benefit/risk ratio when selecting interventions with variable safety and efficacy for the prevention or treatment of cardiometabolic diseases risk. While CMDS can be used as a guideline for any intervention, it is the recent advances in treatment of obesity that have impelled this study. The availability of two new effective medications, phentermine/topiramate ER (8) and lorcaserin (34), has enabled a comprehensive evidence-based medical model for effective and balanced utilization of lifestyle modification, drugs, and bariatric surgery (11). It is important to identify which patients will derive the greatest benefit from these interventions since, with ~70% of US adults being overweight or obese (35), it is not desirable or feasible to treat all patients with medical or surgical therapy. Furthermore, available therapies are often unable to achieve optimal cosmetic results but can dramatically improve both the cardiometabolic and mechanical complications of obesity (8,11,12,34). The patients who will benefit most from therapy have obesity-related complications that can be ameliorated by weight loss.

Currently, BMI is featured predominantly in treatment algorithms that determine therapeutic indications for overweight and obesity, such as that proposed by the NHLBI (12). However, the cardiometabolic and many mechanical complications of obesity exist independent of BMI (4,16,25,28), and may not identify patients who will most benefit from treatment. From this perspective, baseline BMI is less important in targeting patients who will benefit most from weight loss than the existence and severity of complications at baseline (11,13,36). CMDS can be used to identify patients at various degrees of risk for T2DM and CVD mortality, and serve as a guideline for selection of therapeutic modality and intensity. This concept underscores a complications-centric model, as opposed to a BMI-centric model, for obesity management (11,12,23).

Other approaches to risk staging

There are other approaches to risk evaluation for cardiometabolic disease. The clinician should certainly evaluate patients for Metabolic Syndrome and prediabetes, even though Metabolic Syndrome has high specificity but low sensitivity for identifying patients with insulin resistance and cardiometabolic disease (25). Various risk scores also have been constructed using information from the history & physical examination (37) or using clinical laboratory assays (38), and these can be used to stage risk in insulin resistant patients whether or not they meet diagnostic criteria for Metabolic Syndrome or prediabetes. The Edmonton Obesity Staging System has been developed as a valuable guideline for obesity management and incorporates an assessment of both cardiometabolic disease and mechanical complications (13). The Edmonton system features 5 stages (stages 0 to 4), and has been validated to predict only all-cause mortality. Even so, CMDS Stages 1, 2, and 3 would all be included in Edmonton Stage 1. Since we have clearly demonstrated that there was a significant range of differential risk among patients in CMDS Stages 1–3, from this perspective, CMDS provides a more granular dissection of cardiometabolic disease risk.

Study strengths and limitations

Strengths include the use of longitudinal data from two large national cohorts, the CARDIA study and the NHANES III linked mortality file. The studies involved both genders and several racial/ ethnic groups, and this has enabled our findings to be readily applied to the general population. Second, we validated CMDS for predicting risk of incident diabetes, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality over a wide range of BMI. These aspects substantiate the broad application of CMDS for interventions designed to prevent or treat cardiometabolic disease.

This study also has limitations. NHANES, as in any survey, may have sampling and non-sampling errors. Additionally, only a subset of participants received a glucose tolerance test, and some of those participants did not fast over 8 hours, hence they were also excluded from the analysis. The sample size is not large enough to permit extensive subgroup analyses, especially for CVD mortality. Further, mortality follow up was available only till late 2006, and updated follow up information has not yet been released. In the CARDIA study, ascertainment of diabetes in year 15 was made by fasting glucose only, whereas diabetes in year 20 was ascertained by both fasting and 2-hour OGTT glucose. Finally, clinical trials will be needed to determine whether the application of CMDS will enhance outcomes, benefit/risk ratio, safety, and cost-effectiveness of interventions, such as weight loss therapy, to prevent and treat cardiometabolic disease (e.g., T2DM).

Conclusions

CMDS can discriminate a wide range of risk for diabetes, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality independent of BMI, and can be used as a risk assessment tool to guide interventions that prevent and treat cardiometabolic disease. In particular, such a tool can be useful in a complications-centric approach to the treatment of obesity (11,39,40), wherein the goal of weight loss is to ameliorate the complications of obesity, particularly those related to cardiometabolic disease risk. Prospective interventional trials are needed to validate whether that application of CMDS, as a guide to the selection of obesity treatment, will enhance patient outcomes and cost effectiveness of care. The goal is to target treatment intensity, whether involving lifestyle modification, weight loss medication, or bariatric surgery options, to those patients who will derive the greatest benefits from the intervention according to considerations that optimally balance benefit and risk.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about this subject?

Recent approval of new weight loss medications has enabled a pharmaceutical approach for obesity therapy.

However, medical models require an accurate ranking of obesity complications in order to effectively guide the selection of treatment modality and intensity for optimal patient outcomes.

To date, the emphasis has been a BMI centric approach (i.e., NHLBI Guidelines), even though a major portion of cardiometabolic disease risk exists independent of general adiposity.

What does this study add?

We established 5-stages of cardiometabolic disease risk, the Cardiometabolic Disease Staging (CMDS) system, for predicting increasing risk for future T2DM and CVD mortality using parameters from the physical examination and laboratory measurements that would be immediately available to clinicians.

We employed two large national cohorts, the CARDIA study for incident diabetes and the NHANES III linked mortality file for all-cause or CVD mortality, to validate CMDS, and demonstrated the progressive nature of the cardiometabolic disease spectrum.

CMDS can discriminate a wide range of risk for diabetes, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality independent of BMI, and should be studied as a risk assessment tool to guide interventions that prevent and treat cardiometabolic disease for optimal benefit risk ratio.

Acknowledgments

Role of the Sponsors: All data from NHANES used in this study were collected by the National Center for Health Statistics Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data from the CARDIA study is obtained through The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center (BioLINCC).

Primary Funding Source: The Merit Review program of the Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health (DK-038765 and DK-083562), and the UAB Diabetes Research Center (P60-DK079626).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Dr. Garvey and Dr. Guo conceived the study and analysed data. Dr. Moellering reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Center for Health Statistics, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Garvey is an advisor for Alkermes, Plc., Daiichi-Sankyo, Inc., LipoScience, VIVUS, Inc., Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Tethys; is a speaker for Merck; and is a stockholder for Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Isis/Genzyme, Merck, Pfizer, Inc., Eli Lilly and Company, and VIVUS, Inc. He has received research support from Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Merck & Co., and Weight Watchers International, Inc.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. 2013;36:1033–1046. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2. 7 million participants. Lancet. 2011;378:31–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60679-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleeman JI, Grundy SM, Becker D, et al. Executive summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lara-Castro C, Garvey WT. Diet, insulin resistance, and obesity: zoning in on data for Atkins dieters living in South Beach. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4197–4205. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Welborn TA, Dhaliwal SS, Bennett SA. Waist-hip ratio is the dominant risk factor predicting cardiovascular death in Australia. Med J Aust. 2003;179:580–585. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wildman RP, Muntner P, Reynolds K, et al. The obese without cardiometabolic risk factor clustering and the normal weight with cardiometabolic risk factor clustering: prevalence and correlates of 2 phenotypes among the US population (NHANES 1999–2004) Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1617–1624. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knowler WC, Fowler SE, et al. Diabetes Prevention Program Research G. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009;374:1677–1686. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garvey WT, Ryan DH, Look M, et al. Two-year sustained weight loss and metabolic benefits with controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in obese and overweight adults (SEQUEL): a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 extension study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:297–308. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.024927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Brien PE, Macdonald L, Anderson M, Brennan L, Brown WA. Long-term outcomes after bariatric surgery: fifteen-year follow-up of adjustable gastric banding and a systematic review of the bariatric surgical literature. Ann Surg. 2013;257:87–94. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827b6c02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Nutritional, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery Patient - 2013 Update: Cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Endocr Pract. 2013:e1–e36. doi: 10.4158/EP12437.GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garvey WT. Phentermine and Topiramate Extended-Release: A New Treatment for Obesity and Its Role in a Complications-Centric Approach to Obesity Medical Management. Expert Opin Investigational Drugs. 2013 doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.806481. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6 (Suppl 2):51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Padwal RS, Pajewski NM, Allison DB, Sharma AM. Using the Edmonton obesity staging system to predict mortality in a population-representative cohort of people with overweight and obesity. CMAJ. 2011;183:E1059–1066. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. [Accessed March 15, 2013.];NHANES III linked mortality file. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/data_linkage/mortality/nhanes3_linkage.htm.

- 15.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bluher M. Are there still healthy obese patients? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2012;19:341–346. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e328357f0a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meigs JB, Wilson PW, Fox CS, et al. Body mass index, metabolic syndrome, and risk of type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2906–2912. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Parise H, Sullivan L, Meigs JB. Metabolic syndrome as a precursor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2005;112:3066–3072. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.539528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, et al. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA. 2002;288:2709–2716. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.21.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:229–234. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. [Accessed December 5, 2012.];The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) 1988–94, Laboratory Data File Documentation. ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/nhanes/nhanes3/1A/lab-acc.pdf.

- 22. [Accessed March 30, 2013.];The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) Linked Mortality File: Mortality follow-up through 2006 Matching Methodology. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/datalinkage/matching_methodology_nhanes3_final.pdf.

- 23.Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogorodnikova AD, Kim M, McGinn AP, et al. Incident cardiovascular disease events in metabolically benign obese individuals. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:651–659. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao Y, Kwon S, Shaughnessy S, et al. Critical evaluation of adult treatment panel III criteria in identifying insulin resistance with dyslipidemia. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:978–983. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.4.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Einhorn D, et al. Diagnosis and management of prediabetes in the continuum of hyperglycemia: when do the risks of diabetes begin? A consensus statement from the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Endocr Pract. 2008;14:933–946. doi: 10.4158/EP.14.7.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingram KH, Lara-Castro C, Gower BA, et al. Intramyocellular lipid and insulin resistance: differential relationships in European and African Americans. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:1469–1475. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kip KE, Marroquin OC, Kelley DE, et al. Clinical importance of obesity versus the metabolic syndrome in cardiovascular risk in women: a report from the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. Circulation. 2004;109:706–713. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115514.44135.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rexrode KM, Carey VJ, Hennekens CH, et al. Abdominal adiposity and coronary heart disease in women. JAMA. 1998;280:1843–1848. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.21.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo F, Zhang W, Garvey WT. Differentially segmented association between HbA1c and CHD risks and FPG across ethnicities. Later breaking poster; The 72nd Scientific Session of American Diabetes Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elizabeth S, Michael WS, Edward G, Frederick LB, Josef C. Performance of A1C for the classification and prediction of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:84–89. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qiao Q, Tuomilehto J, Balkau B, et al. Are insulin resistance, impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance all equally strongly related to age? Diabet Med. 2005;22:1476–1481. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Decode Study Group the European Diabetes Epidemiology Group. Glucose tolerance and cardiovascular mortality: comparison of fasting and 2-hour diagnostic criteria. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:397–405. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith SR, Weissman NJ, Anderson CM, et al. Multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of lorcaserin for weight management. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:245–256. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korn EL, Graubard BI, Midthune D. Time-to-event analysis of longitudinal follow-up of a survey: choice of the time-scale. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:72–80. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D’Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shafizadeh TB, Moler EJ, Kolberg JA, et al. Comparison of accuracy of diabetes risk score and components of the metabolic syndrome in assessing risk of incident type 2 diabetes in Inter99 cohort. PloS one. 2011;6:e22863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindstrom J, Tuomilehto J. The diabetes risk score: a practical tool to predict type 2 diabetes risk. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:725–731. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al. AACE Comprehensive Diabetes Management Algorithm 2013. Endocr Pract. 2013;19:327–336. doi: 10.4158/endp.19.2.a38267720403k242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.