Abstract Abstract

We use a combination of cytochrome b sequence data and karyological evidence to confirm the presence of Mus indutus and Mus minutoides in Botswana. Our data include sampling from five localities from across the country, including one site in northwestern Botswana where both species were captured in syntopy. Additionally, we find evidence for two mitochondrial lineages of M. minutoides in northwestern Botswana that differ by 5% in sequence variation. Also, we report that M. minutoides in Botswana have the 2n=34 karyotype with the presence of a (X.1) sex-autosome translocation.

Keywords: Africa, rodent, distribution, karyotype, sex-autosome translocation, cytochrome b

Introduction

Delineating geographic distributions of African Mus (subgenus Nannomys Peters, 1876) in Sub-Saharan Africa has been especially challenging due to a combination of incomplete taxon sampling throughout the region as well as uncertainties in species identification resulting from their highly conserved morphology. Despite morphological similarities, African pygmy mice (Nannomys) are characterized by a high degree of chromosomal variation, including chromosomal rearrangements such as Robertsonian translocations, pericentric inversions, heterochromatin additions, and tandem fusions (see summary in Britton-Davidian et al. 2012). Additionally, whole-arm translocations (WARTs) and novel sex-chromosome determination have been documented in populations in South Africa (Veyrunes et al. 2007, 2013).

Britton-Davidian et al. (2012) produced the most complete phylogenetic analysis of Nannomys to date, which included previously published sequences of nine species (Suzuki et al. 2004; Chevret et al. 2005; Veyrunes et al. 2005; Kan Kouassi et al. 2008; Veyrunes et al. 2010; Mboumba et al. 2011; and others). Their phylogeny illuminated the diversity of taxa within this subgenus (including at least one unnamed species from Chad), and clearly indicated that further phylogenetic investigations are necessary to clarify species diversity within Nannomys. Their comprehensive review surmised that there are at least 18 species of African pygmy mice and estimated that eight species occur within southern Africa (Britton-Davidian et al. 2012). In addition, theirstudy highlighted important gaps in both geographic and taxonomic sampling for this subgenus, particularly within southern Africa. Included in this underrepresented southern African group is Mus minutoides, one of the most widespread pygmy mice, with a distribution encompassing most of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Within the southern African country of Botswana, the taxonomy of Mus has never fully been resolved. Early assessments of the regional mammalian fauna (Smithers 1971) concluded that two native forms of Mus exist within Botswana: the widespread Mus minutoides indutus (Thomas, 1910)—which was later elevated to specific status (Petter and Matthey 1975; Musser and Carleton 1993, 2005)—and an arid-adapted form with large ears and a white band of fur near the rump (referred to as Leggada sp. in Smithers 1971) restricted to northwestern Botswana and a single record from Sekhuma Pan in the Jwaneng District of southern Botswana (Petter 1978). This latter species was later described as Mus setzeri Petter, 1978. De Graaff’s (1981) assessment of Nannomys in southern Africa concluded that all records for Botswana conform to Mus minutoides, although he acknowledged that Mus minutoides indutus and the desert form (Mus setzeri) may be distinct species that require further study. More recent evaluations describe allopatric distributions for Mus indutus and Mus minutoides and only acknowledge the former within the boundaries of Botswana (Skinner and Chimimba 2005, Happold and Veyrunes 2013). These recent assessments estimated the geographic range for Mus minutoides as extending from the southwest cape in South Africa through the Zambezian woodlands in the east (Fig. 1a, dark grey). Monadjem (2013a) stated that Mus indutus replaces Mus minutoides in the western part of the Zambezian woodlands and extends throughout Botswana and into neighboring countries (Fig. 1a, light grey). Although Britton-Davidian et al. (2012) proposed that the range of Mus minutoides greatly differs from the map published by Monadjem (2008b), and including the countries of Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, verified records from their study were only presented for South Africa, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe. However, records of Mus minutoides have recently been confirmed for Angola and Namibia (Lamb et al. 2014), providing additional support for the extended range map proposed by Britton-Davidian et al. (2012)

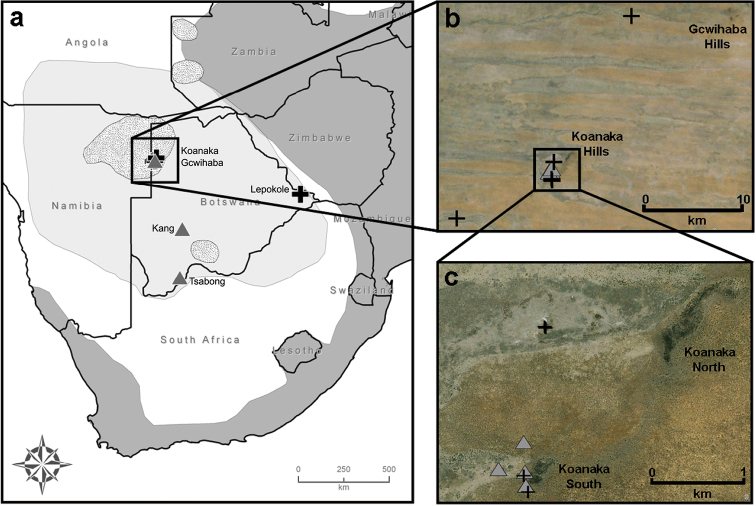

Figure 1.

Distributions for three species of Nannomys in southern Africa. Dark grey indicates distribution for Mus minutoides, light grey for Mus indutus, and stippled pattern for Mus setzeri, adapted from Monadjem (2008a), Monadjem (2008b), and Monadjem and Coetzee (2008), respectively. Five trapping localities in Botswana (a); black crosses indicate captures for Mus minutoides and grey triangles for Mus indutus. Records from northwestern Botswana, Ngamiland District (b). Locality of syntopic records for Mus indutus and Mus minutoides at Koanaka Hills site (c).

Regarding chromosomal rearrangement in southern Africa, Mus minutoides from South Africa exhibit Robertsonian fusions with two major monophyletic groups showing either a diploid number of 2n=18 – where all of the acrocentric chromosomes are fused to produce metacentric elements, or a 2n=34 – where sex-chromosome translocations have been reported (Veyrunes et al. 2010). Additionally, WARTs have been documented in several populations exhibiting the 2n=18 karyotype in South Africa, which has contributed significantly to reported chromosomal variation, with at least four different cytotypes within this clade (Veyrunes et al. 2007). Currently, the geographic distributions of the 2n=18 and 2n=34 forms of Mus minutoides are not known outside of the country of South Africa (Veyrunes et al. 2010).

Our objective was to utilize material from recent collecting efforts and molecular techniques to accurately delimit which species of Nannomys occur within Botswana. Further, we describe karyotypes for individuals from this region and make comparisons with previously published data from South Africa.

Materials and methods

Our mitochondrial phylogeny was generated from combining previously published sequences deposited on GenBank (Appendix) with those derived from sequencing new specimens collected during field trips to Botswana conducted in 2008, 2009, and 2011 (Table 1, Appendix). We collected 16 specimens of Mus from five localities in Botswana including: Gcwihaba Caves (20°00.99'S, 21°15.89'E); Kang (23°32.10'S, 22°32.76'E); Koanaka Hills (20°09.60'S, 21°11.61'E); Lepokole Hills (21°49.59'S, 28°23.94'E); and Tsabong (25°56.57'S, 22°25.44'E) (Fig. 1a–c). Specimens were collected using Sherman live traps, pitfall traps, or Museum Special snap traps. Standard external measurements were recorded in the field (Table 1). Specimens were preserved as skins with complete skeletons (SSPS), skulls only, or as whole bodies in alcohol (alc.) and deposited at the at the Natural Science Research Laboratory (NSRL) at the Museum of Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, USA or the Botswana National Museum, Gaborone, Botswana. Tissue samples were preserved in 95% ethanol, lysis buffer, or flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for future genomic analyses (2011 material) and deposited in the NSRL. Field collecting methods followed taxon specific guidelines for wild mammals (Sikes et al. 2012) as outlined by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists (Gannon et al. 2007; Sikes et al. 2011).

Table 1.

Locality information for 16 specimens of Mus (Nannomys) collected in Botswana during June 2008, July 2009, and August 2011. Verbatim coordinates were recorded in the field using a handheld Garmin GPS Rino 120 unit using the datum WGS84. Elevations given in meters.

| Tissue No. | Genbank No. | Species | District | Specific Locality | Verbatim Coordinates | Verbatim Coordinate System | Verbatim SRS | Verbatim Elevation | Latitude, Longitude | Elev. | Coordinate Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TK170604 | KF184321 | Mus indutus | Kgalagadi | Berry Bush Farm, 8 km N, 2 km E Tsabong (Tshabong) | -25.94283, 22.42405 | Decimal degrees | WGS84 | 971 | 25°56.57'S, 22°25.44'E | 970 | 31.5 m |

| TK172845 | KF184320 | Mus indutus | Kgalagadi | Berry Bush Farms, 8 km N, 2 km E Tsabong (Tshabong) | -25.94283, 22.42405 | Decimal degrees | WGS84 | 971 | 25°56.57'S, 22°25.44'E | 970 | 31.5 m |

| TK172826 | KF184322 | Mus indutus | Kgalagadi | Kalahari Rest, 16 km N, 25 km W Kang | -23.53498, 22.54607 | Decimal degrees | WGS84 | 1158 | 23°32.10'S, 22°32.76'E | 1160 | 31.5 m |

| TK172785 | KF184310 | Mus minutoides | Central | Lepokole Hills, 3.6 km S, 4.9 km E Lepokole Village | -21.82653, 28.39898 | Decimal degrees | WGS84 | 784 | 21°49.59'S, 28°23.94'E | 780 | 31.5 m |

| TK164851 | KF184309 | Mus minutoides | Ngamiland | Koanaka Hills (Ncqumtsa Hills), 150 km W Tsao (Tsau), water hole | 34K 0511309 7767149 | UTM | WGS84 | 1019 | 20°11.58'S, 21°06.49'E | 1020 | 31.5 m |

| TK154612 | KF184311 | Mus minutoides | Ngamiland | Koanaka Hills (Ncqumtsa Hills), 150 km W Tsao (Tsau), main camp | 34K 0520241 7770802 | UTM | WGS84 | 1024 | 20°09.60'S, 21°11.62'E | 1020 | 31.5 m |

| TK164817 | KF184316 | Mus indutus | Ngamiland | " | 34K 0520219 7770803 | UTM | WGS84 | 1021 | 20°09.60'S, 21°11.61'E | 1020 | 31.5 m |

| TK164820 | KF184318 | Mus indutus | Ngamiland | " | 34K 0520219 7770803 | UTM | WGS84 | 1021 | 20°09.60'S, 21°11.61'E | 1020 | 31.5 m |

| TK164753 | KF184319 | Mus indutus | Ngamiland | " | 34K 0520210 7770958 | UTM | WGS84 | 1020 | 20°09.51'S, 21°11.60'E | 1020 | 31.5 m |

| TK164752 | KF184312 | Mus minutoides | Ngamiland | " | 34K 0520198 7770976 | UTM | WGS84 | 1020 | 20°09.51'S, 21°11.60'E | 1020 | 31.5 m |

| TK164751 | KF184315 | Mus indutus | Ngamiland | " | 34K 0519948 7770988 | UTM | WGS84 | 1022 | 20°09.50'S, 21°11.45'E | 1020 | 31.5 m |

| TK164757 | KF184323 | Mus indutus | Ngamiland | " | 34K 0519948 7770988 | UTM | WGS84 | 1022 | 20°09.50'S, 21°11.45'E | 1020 | 31.5 m |

| TK164939 | KF184317 | Mus indutus | Ngamiland | " | 34K 0520201 7771287 | UTM | WGS84 | 1027 | 20°09.34'S, 21°11.60'E | 1030 | 31.5 m |

| TK164768 | KF184313 | Mus minutoides | Ngamiland | " | 34K 0520416 7772600 | UTM | WGS84 | 1026 | 20°08.62'S, 21°11.72'E | 1030 | 31.5 m |

| TK164769 | KF184308 | Mus minutoides | Ngamiland | " | 34K 0520408 7772612 | UTM | WGS84 | 1020 | 20°08.62'S, 21°11.72'E | 1020 | 31.5 m |

| TK164967 | KF184314 | Mus minutoides | Ngamiland | Gcwihaba Caves, 18.8 km N, 114.2 km W Tsao (Tsau) | 34K 0527701 7786660 | UTM | WGS84 | 986 | 20°00.99'S, 21°15.89'E | 990 | 31.5 m |

Genomic DNA was extracted using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, California). The complete cytochrome b gene (cytb, 1140 nucleotides) was amplified following methods outlined in Veyrunes et al. (2010). Cycle sequencing reactions were performed with BigDye terminator version 3.1 and were electrophoresed on an ABI 3100-Avant (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). Sequences were edited and aligned using SEQUENCHER version 4.9 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, Michigan). Novel sequences (GenBank accession nos. KF184308-KF184323) were aligned with previously published sequences deposited on GenBank using only individuals that exhibited unique haplotypes (Appendix). The final alignment was trimmed to exclude regions with large amounts of missing data due to the large number of GenBank sequences in the alignment that were partial cytb sequences. Therefore, a total of 741 base pairs of the cytb gene (the first 7 codons and last 126 codons were removed from the analysis) were used in the final alignment for the phylogenetic analysis including 125 individuals.

Appropriate models of evolution were examined using MEGA version 5 (Tamura et al. 2011). Phylogenetic relationships were estimated using Bayesian inference with the program MRBAYES version 3.2 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001). Four independent Markov chains were run for 50 million generations and trees were logged every 1000th iteration. Log-likelihood values were examined in the program TRACER version 1.5 (Rambaut and Drummond 2007) and the first 5,000 trees were discarded as burn-in. An additional phylogeny was estimated using the Maximum-likelihood method with the program PhyML version 3.0 (Guindon et al. 2010) with a BIONJ starting tree (Gascuel 1997) and 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Kimura 2-parameter genetic distances were calculated using MEGA version 5 (Tamura et al. 2011).

Specimens were karyotyped in the field using bone marrow after 1 h of in vivo incubation with Velban (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri), following the methods described in Baker et al. (2003). Mus indutus males were not karyotyped in this study because both males captured died in snap traps. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) experiments were performed using Star*FISH © biotin-labeled mouse chromosome X paints (Cambio), following the manufacturer’s instructions and using Cy3-conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen) for signal detection.

In order to assess the nature of the X-autosome translocation of the specimens that exhibited the translocation, we compared the X-chromosome of our specimens with those from South Africa using images of inverted DAPI-banding, and G-banding (Seabright 1971). Images were captured using the GENUS SYSTEM version 3.7 (Applied Imaging Systems, San Jose, California) through an Olympus BX51 epi-fluorescence microscope. Cy3 and DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) signals were pseudocolored yellow and red, respectively.

Results

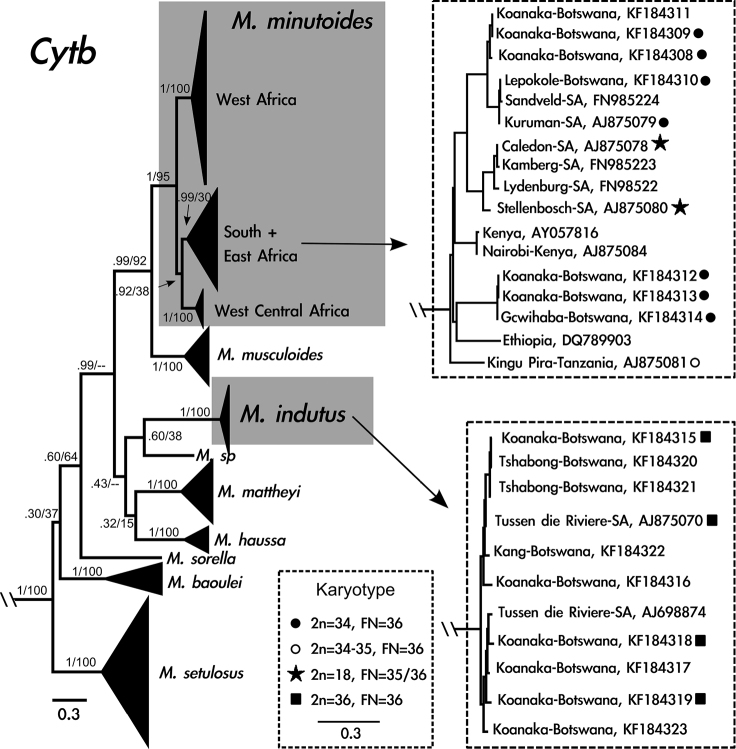

The model with the lowest AICc (Akaike Information Criterion, corrected) and BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) scores was the General Time Reversible (GTR) model using a discrete gamma distribution (+G) and a fraction of invariable sites (+I). Overall, the two methods of phylogenetic analysis resulted in similar tree topologies, except that the Maximum-likelihood analysis recovered weak support for the south + east Mus minutoides clade (Fig. 2). Additionally, the relationship between Mus indutus, Mus sp., Mus mattheyi, Mus haussa, and the portion of the phylogeny that includes Mus minutoides and Mus musculoides was unresolved in the Maximum-likelihood analysis, though it was well-supported using Bayesian inference.

Figure 2.

Cytochrome b gene tree generated from 741 base pairs including 125 taxa using Bayesian inference. Grey boxes indicate species of interest: Mus minutoides and Mus indutus. Clades that include Mus from Botswana are enlarged to the right of the phylogeny. Diploid and fundamental numbers are shown for individuals sampled in this study and Veyrunes et al. (2005). Identification includes GenBank number and general locality. Support values at nodes are Bayesian posterior probabilities followed by Maximum-likelihood bootstrap support; dashes indicate regions of the tree where Maximum-likelihood analysis resulted in a polytomy.

Sixteen cytb sequences were generated from specimens from Botswana, corresponding to two species. Seven individuals are phylogenetically related to Mus minutoides from South Africa and nine individuals cluster with Mus indutus. Five individuals, captured from the same locality in the Koanaka Hills region of northwestern Botswana, represent two clades within Mus minutoides that are 5% different in cytb sequence variation (Fig. 2). Six of the individuals of Mus indutus were collected in the Koanaka Hills alongside both of these lineages of Mus minutoides (Fig. 1c).

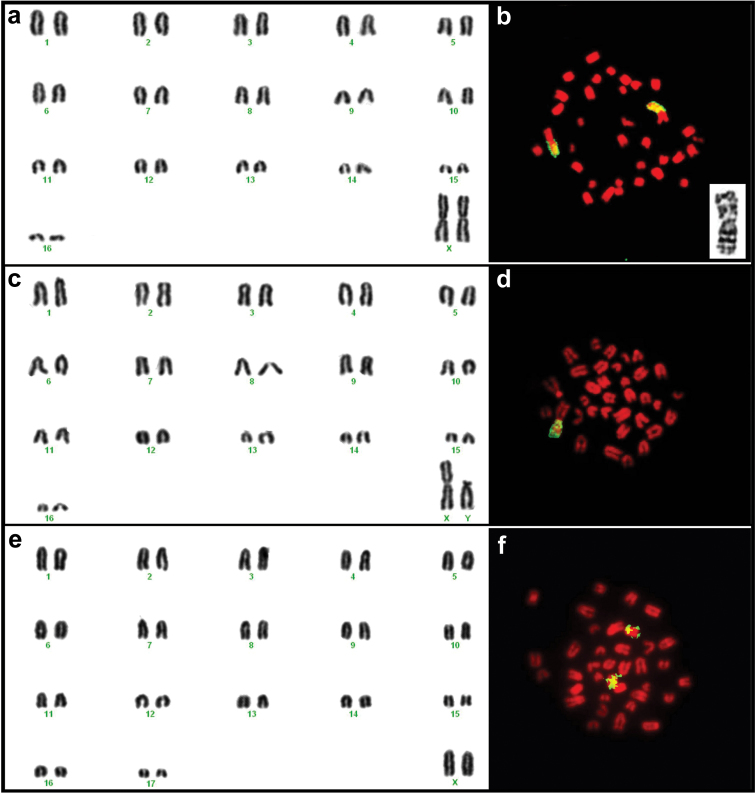

Karyotypes for individuals in the Mus minutoides clade exhibited a diploid number of 34 and fundamental number (as defined by Veyrunes et al. 2004 as the total number of chromosomal arms per diploid genome, instead of number of autosomal arms) of FN=36 (Fig. 3a–d, Table 2). All autosomes were acrocentric in morphology, including the pair 13, which presented a small short arm in some metaphase spreads. The metacentric X chromosome is the largest element of the chromosome complement, followed by the subtelocentric Y chromosome, which is comparable in size with the first autosomal pair. Individuals in the Mus indutus clade exhibited diploid and fundamental numbers of 36 (Fig. 3e–f, Table 2). All chromosomes had an acrocentric morphology. Due to the lack of male karyotyped specimens, the Y chromosome morphology could not be determined. The FISH with Mus X whole chromosome probe allowed the detection of an X-autosome translocation on the karyotypes of Mus minutoides specimens (Fig. 3b, d), but not for individuals of Mus indutus (Fig. 3e). Banding results indicate that individuals of Mus minutoides from Botswana share the same sex-chromosome translocations (X.1) and (Y.1) as Mus minutoides from South Africa, although differential condensation of the South African chromosomes makes direct comparison difficult (Fig. 3a and b).

Figure 3.

Karyotypes of female TK164752 (a) and male TK164768 (c) Mus minutoides and female TK164753 Mus indutus (e) from Botswana. The chromosome arms identified in yellow on the images to the right of each karyogram correspond to regions of homology to the X chromosome of Mus musculus detected by FISH for female TK164752 (b) and male TK164768 (d) Mus minutoides and female TK164820 Mus indutus (f). Note that in Mus minutoides, a single chromosome arm shows homology to the X chromosome of the house mouse, indicating the presence of an X-autosome translocation, whereas a whole acrocentric chromosome corresponds to the X of Mus indutus. The insert on (b) represents the (1.X) translocation of individual TK164752 Mus minutoides, with the long arm corresponding to the X chromosome.

Table 2.

Individuals of Mus (Nannomys) collected in Botswana including GenBank number, final species identification, gender determined in the field, museum preparation type (Alcoholic=alc; skin, skull, postcranial skeleton=SSPS; or Skull only), collection date, total length (TL), tail length (T), hind foot (HF), ear (E), weight in grams, karyotype, and sex-chromosome.

| Genbank No. | Species | Gender “Field” | Prep. Type | Coll. Date | TL | T | HF | E | Weight (g) | Karyotype | Gender “Lab” |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KF184315 | Mus indutus | Female | SSPS | 16-Jul-09 | 95 | 42 | 13 | 13 | 4,5 | 2n=36, FN=36 | XX |

| KF184316 | Mus indutus | Female | SSPS | 22-Jul-09 | 85 | 40 | 10 | 10 | 2,9 | none | - |

| KF184317 | Mus indutus | Female | SSPS | 27-Jul-09 | 101 | 43 | 14 | 11 | 5,1 | none | - |

| KF184318 | Mus indutus | Female | SSPS | 22-Jul-09 | 14 | 45 | 12 | 10 | 6,3 | 2n=36, FN=36 | XX |

| KF184319 | Mus indutus | Female | SSPS | 15-Jul-09 | 110 | 45 | 13 | 11 | 6,75 | 2n=36, FN=36 | XX |

| KF184320 | Mus indutus | Male | SSPS | 18-Aug-11 | 98 | 45 | 15 | 10 | 4 | none | - |

| KF184321 | Mus indutus | Female | Alc | 25-Aug-11 | 75 | [23] | 14 | 10 | 3 | none | - |

| KF184322 | Mus indutus | Female | Skull Only | 17-Aug-11 | 109 | 40 | 15 | 11 | 5 | none | - |

| KF184323 | Mus indutus | Male | SSPS | 20-Jul-09 | 86 | 42 | 14 | 12 | 4 | none | - |

| KF184308 | Mus minutoides | Female | SSPS | 20-Jul-09 | 107 | 43 | 14 | 12 | 5,5 | 2n=34, FN=36 | XX |

| KF184309 | Mus minutoides | Male | SSPS | 24-Jul-09 | [80] | [23] | 13 | 11 | 4,6 | 2n=34, FN=36 | XY |

| KF184310 | Mus minutoides | Female | SSPS | 16-Aug-11 | 93 | 45 | 13 | 10 | 3,5 | 2n=34, FN=36 | XY |

| KF184311 | Mus minutoides | Male | SSPS | 26-Jun-08 | 102 | 47 | 14 | 12 | 5,8 | none | - |

| KF184312 | Mus minutoides | Female | SSPS | 15-Jul-09 | 111 | 52 | 15 | 11 | 5,5 | 2n=34, FN=36 | XX |

| KF184313 | Mus minutoides | Female | SSPS | 20-Jul-09 | 99 | 44 | 12 | 9 | 4 | 2n=34, FN=36 | XY |

| KF184314 | Mus minutoides | Female | SSPS | 26-Jul-09 | 96 | 47 | 14 | 10 | 3,7 | 2n=34, FN=36 | XY |

Discussion

Efforts to resolve the geographic distributions of African pygmy mice remain in a state of flux. Regional studies involving DNA sequence data and karyotypes, such as presented here, contribute to a broader understanding of this complex genus. Historical (see Schmidt et al. 2008) and recent (Ferguson et al. 2010) bioinventories have resulted in extensive collections of Mus from Botswana, but there has been little consensus as to whether both Mus minutoides and Mus indutus occur in the country.

Mitochondrial sequence and cytogenetic data confirm the presence of both Mus minutoides and Mus indutus in Botswana. These specimens represent the first DNA sequences for these two species in Botswana, which we also made available for use in a recent paper by Lamb et al. (2014). Despite previous suggestions that Mus minutoides and Mus indutus occur in allopatry, our results confirm that these two species occur in sympatry and even syntopy in northwestern Botswana. Interestingly, we also found two lineages of Mus minutoides in northwestern Botswana (Koanaka Hills) that were 5% different in cytb sequence variation. We hypothesize that these two mitochondrial lineages were separated in the past and have now come back together in a region of secondary contact in the arid savannah region near the Kalahari Desert, a hypothesis that should be tested with broader sampling and using additional genetic markers.

Also of interest is the fact that no Mus setzeri were collected from either the Koanaka Hills or Gcwihaba Caves although their current range – as delimited by Monadjem and Coetzee (2008) and Skinner and Chimimba (2005) – includes this region of Botswana. We compared our specimens with Mus setzeri deposited at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., USA and found no evidence that any of our individuals correspond to this conspicuous form. Our failure to capture Mus setzeri,in spite of concerted trapping efforts in this region (> 2600 Sherman trap nights, > 280 pitfall trap nights during June 2008 and July 2009 seasons), is in agreement with Monadjem (2013b) who pointed to the scarcity of this species in collections as evidence for true ecological rarity. Further sampling is clearly warranted to more accurately delimit the exact geographic boundaries of Nannomys species both within Botswana and throughout the broader Southern African Subregion (Skinner and Chimimba 2005).

Mus minutoides in Botswana exhibit the 2n=34 karyotype with the diagnostic (X.1) and (Y.1) sex-autosome translocations that have also been documented in specimensfrom South Africa (Veyrunes et al. 2010), Zambia, Kenya (Castiglia et al. 2002, 2006), Central African Republic, and Ivory Coast (Jotterand-Bellomo 1984, 1986). Veyrunes et al. (2004) propose that 2n=34 with the 1 sex chromosome translocation is the ancestral karyotype for Mus minutoides and our results provide further support for an early (X.1) translocation before the radiation of Mus minutoides over a large geographic area. Furthermore, the 2n=34 cytotype is reported in several locations in northern South Africa, but not in southern South Africa or in other countries to the north, including Botswana. The fact that our sampling localities included individuals from the easternmost and northwestern regions of Botswana might be an indicator that this is the predominant cytotype in the country, likely extending into the bordering countries of Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Namibia.

We found that three of our gender identifications made in the field (Table 2, “Gender Field”) did not match the identifications made from karyotype assessments (Table 2, “Gender Lab”) indicating the potential for X*Y females. Therefore, we attempted to examine these specimens for the possibility of sex reversal in Mus minutoides, which has been documented in other countries (Veyrunes et al. 2013). Although we have tried to identify the X* chromosome in our samples through X chromosome morphology assessment as well as DAPI banding patterns, the particular high degree of condensation of the chromosomes in our in vivo bone marrow preparations did not allow us to ascertain the nature of the X chromosomes of two of these three specimens. For one of the individuals, both the morphology and banding patterns of the X chromosome do not seem to correspond to those of the derivative X* chromosome (Fig. 3a), indicating that field misidentification of sex might have been the case for that specimen (the reproductive organs can no longer be clearly seen on the prepared skin of this specimen). Additionally, there were no evident X chromosome polymorphisms in the XX female specimens, which would be expected in populations where X*Y females were present. Due to our small sample, and the relative low frequency of the X* found in populations outside South Africa, we were not able to rule out the presence of the X polymorphism in Botswana. Further collecting efforts, together with an in depth sex determination study, including high quality chromosome preparations suitable for G-banding studies, will be needed to shed further light on this issue.

Our data presented here agree with previous molecular phylogenies of Nannomys, with well-defined clades representing Mus minutoides and Mus indutus exhibiting diploid and fundamental numbers consistent with those reported in the literature. Veyrunes et al. (2010) detected a wide range of chromosomal variation for Mus minutoides in South Africa, with one particular clade presenting 2n=34, FN=36. Our Mus minutoides samples display chromosome conservation as well as sequence similarity to the South African clade bearing karyotypic stasis, indicating that these specimens might be part of a widespread group chromosomally and genetically isolated from the karyotypically diverse 2n=18 Mus minutoides clade. Mus indutus on the other hand exhibits a karyotype not very divergent from the proposed ancestral karyotype for Nannomys (2n=36 with all acrocentric chromosomes; Veyrunes et al. 2004), similar to many of the basal lineages included in recent molecular phylogenies (see Britton-Davidian et al. 2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Baker for providing travel funds, laboratory funds, and facilities to conduct the molecular research. For access to specimens and assistance during museum visits, we thank K. Helgen and D. Lunde of the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution and for loan of tissues H. Garner and K. MacDonald of the NSRL, Museum of Texas Tech University Museum. For assisting with trapping locations, we thank J. and D. Thomas of Berry Bush Farms, B. and M. Sieberhagen of Kalahari Rest, and the village development committee chairperson at Lepokole Village. We also thank the Ministry of Youth, Sport, and Culture for assistance with 2008-2009 permits [permit number: CYSC 1/17/21(81)]. For assistance with permits in 2011 we thank Tuelo Nkwane with the Botswana Ministry of Environment, Wildlife, and Tourism [permit number: EWT 8/36/4 XVI (46)]. Specimens were collected under SHSU IACUC issued to MLT (permit number: 08-04-03-1005-3-01). For assistance with field support and logistics during the 2008 and 2009 trips we thank M. Gabadirwe, J. Marenga, B. Mokotedi and for 2011 we thank the Botswana National Museum, including K. Lemson and Jaime Castro Navarro of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. For assistance with logistics, field support, and field supplies for all years we thank J. Marais. We would especially like to thank Mr. N. E. Mosesane of the Botswana National Museum for his support of this work. A RAPID grant award 0910365 from the United States National Science Foundation as well as Faculty Research Grants and Exploratory Grants for Research from Sam Houston State University to MLT and PJL were used to fund 2008–2009 expeditions. An Explorers Club-Exploration Fund Research Grant and Texas Academy of Science Research Grant to MMM provided partial funding for 2011 fieldwork.

Appendix

Individuals included in the molecular phylogeny representing eleven species with the country of origin, GenBank number and the original citation for the original description. RCA = Central African Republic.

Tables 1, 2, and Appendix

These are the tables (1 and 2) and Appendix.

References

- Baker RJ, Hamilton M, Parish DA. (2003) Preparations of mammalian karyotypes under field conditions. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Texas Tech University 228: i+1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Barome PO. (1998) Phylogéographie du genre Acomys (Rodentia, Muridae) fondée sur l’ADN mitochondrial. PhD thesis Université de Paris Sud; (XI), France. [Google Scholar]

- Britton-Davidian J, Robinson TJ, Veyrunes F. (2012) Systematics and evolution of the African pygmy mice, subgenus Nannomys: a review. Acta Oecologica 42: 41-49. doi: 10.1016/j.actao.2012.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglia R, Gornug E, Corti M. (2002) Cytogenetic analyses of chromosomal rearrangements in Mus minutoides/musculoides from north-west Zambia through mapping of the telomeric sequence (TTAGGG)n and banding techniques. Chromosome Research 10: 399-406. doi: 10.1023/A:1016853719616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castiglia R, Garagna S, Merico V, Oguge N, Corti M. (2006) Cytogenetics of a new cytotype of African Mus (subgenus Nannomys) minutoides (Rodentia, Muridae) from Kenya: C- and G-banding and distribution of (TTAGGG)n telomeric repeats. Chromosome Research 14: 587-594. doi: 10.1007/s10577-006-1054-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevret P, Veyrunes F, Britton-Davidian J. (2005) Molecular phylogeny of the genus Mus (Rodentia: Murinae) based on mitochondrial and nuclear data. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 84: 417-427. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00444.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coulibaly-N’Golo D, Allali B, Kan Kouassi S, Fichet-Calvet E, Becker-Ziaja B, Rieger T, ölschläger S, Dosso H, Denys C, ter Meulen J, Akoua-Koffi C, Günther S. (2011) Novel arenavirus sequences in Hylomyscus sp. and Mus setulosus from Côte d’Ivoire: implications for evolution of arenaviruses in Africa. PLoS ONE 6: e20893 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Graaff G. (1981) The Rodents of Southern Africa. Butterworth & Co (SA) (PTY) LTD, Durban, Republic of South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Dobigny G, Tatard C, Kane M, Gauthier P, Brouat C, Khalilou B, Duplantier JM. (2011) A cytotaxonomic and DNA-based survey of rodents from northern Cameroon and western Chad. Mammalian Biology 76: 417-427. doi: 10.1016/j.mambio.2010.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson AW, McDonough MM, Thies ML, Lewis PJ, Gabadirwe M. (2010) Mammals of the Koanaka Hills (Nqcumtsa Hills) region, Ngamiland, Botswana: a provisional checklist. Botswana Notes and Records 42: 163-171. [Google Scholar]

- Gannon WL, Sikes RS. (2007) Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research. Journal of Mammalogy 88: 809-823. doi: 10.1644/06-MAMM-F-185R1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. (2010) New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Systematic Biology 59: 307-321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascuel O. (1997) BIONJ: An improved version of the NJ algorithm, based on a simple model of sequence data. Molecular Biology and Evolution 14: 685-695. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happold DCD, Veyrunes F. (2013) Genus Mus, Old World mice and pygmy mice. In: Happold DCD. (Ed) Mammals of Africa Vol. 3: Rodentia. Bloomsbury Publishing, London, 473-498. [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. (2001) MrBayes: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics 17: 754-755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jotterand-Bellomo M. (1984) L’ánalyse cytogénétique de deux espèces de Muridae africains, Mus oubanguii et Mus minutoides/musculoides: polymorphisme chromosomique et ébauche d’une phylogénie. Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics 38: 182-188. doi: 10.1159/000132057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jotterand-Bellomo M. (1986) Le genre Mus africain, un exemple d’homogénéité caryotipique: etude cytogénétique de Mus minutoides/musculoides (Côte d’Ivore), de M. setulosus (Republique Centrafricaine), et de M. mattheyi (Burkina Faso). Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics 42: 99–104. doi: 10.1159/000132259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kan Kouassi S, Nicolas V, Aniskine V, Lalis A, Cruaud C, Couloux A, Colyn M, Dosso M, Koivogui L, Verheyen E, Akoua-Koffi C, Denys C. (2008) Taxonomy and biogeography of the African pygmy mice, subgenus Nannomys (Rodentia, Murinae, Mus) in Ivory Coast and Guinea (West Africa). Mammalia 72: 237-252. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb J, Downs S, Eiseb S, Taylor PJ. (2014) Increased geographic sampling reveals considerable new genetic diversity in the morphologically conservative African pygmy mice (genus Mus; subgenus Nannomys). Mammalian Biology 79: 24-35. doi: 10.1016/j.mambio.2013.08.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lundrigan BL, Jansa SA, Tucker PK. (2002) Phylogenetic relationships in the genus Mus, based on paternally, maternally, and biparentally inherited characters. Systematic Biology 51: 410-431. doi: 10.1080/10635150290069878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mboumba JF, Deleporte P, Colyn M, Nicolas V. (2011) Phylogeography of Mus (Nannomys) minutoides (Rodentia, Muridae) in West Central African savannahs: singular vicariance in neighbouring populations. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 49: 77-85. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0469.2010.00579.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monadjem A. (2008a) Mus indutus. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1. www.iucnredlist.org [accessed on 12 September 2013]

- Monadjem A. (2008b) Mus minutoides. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1. www.iucnredlist.org [accessed on 12 September 2013]

- Monadjem A, Coetzee N. (2008) Mus setzeri. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1. www.iucnredlist.org [accessed on 12 September 2013]

- Monadjem A. (2013a) Mus minutoides. In: Happold DCD. (Ed) Mammals of Africa Vol. 3: Rodentia. Bloomsbury Publishing, London, 484-486. [Google Scholar]

- Monadjem A. (2013b) Mus setzeri. In: Happold DCD. (Ed) Mammals of Africa Vol. 3: Rodentia. Bloomsbury Publishing, London, 493-494. [Google Scholar]

- Musser GG, Carleton MD. (1993) Family Muridae. In: Wilson DE, Reeder DM. (Eds) Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference, second edition. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., 501-755. [Google Scholar]

- Musser GG, Carleton MD. (2005) Family Muridae. In: Wilson DE, Reeder DM. (Eds) Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference, third edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 894-1531. [Google Scholar]

- Petter F. (1978) Une souris nouvelle du sud de l’Afrique: Mus setzeri sp. nov. Mammalia 42: 377-379. [Google Scholar]

- Petter F, Matthey R. (1975) Genus Mus Part 6.7. In: Meester J, Setzer HW. (Eds) The mammals of Africa: An identification manual. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C., 1-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. (2007) Tracer v.1.5. http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer

- Schmidt DF, Ludwig CA, Carleton MD. (2008) The Smithsonian Institution African Mammal Project (1961–1972): an annotated gazetteer of collecting localities and summary of its taxonomic and geographic scope. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 628: 1-320. doi: 10.5479/si.00810282.628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwan TG, Anderson JM, Lopez JE, Fischer RJ, Raffel SJ, McCoy BN, Safronetz D, Sogoba N, Maïga O, Traoré SF. (2012) Endemic foci of the tick-borne relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia crocidurae in Mali, West Africa, and the potential for human infection. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 6: e1924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seabright M. (1971) A rapid banding technique for human chromosomes. Lancet 2: 971-972. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(71)90287-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikes RS, Gannon WL, and the Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists. (2011) Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research. Journal of Mammalogy 92: 235-253. doi: 10.1644/10-MAMM-F-355.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikes RS, Paul E, Beaupre SJ. (2012) Standards for wildlife research: taxon-specific guidelines versus US Public Health Service Policy. BioScience 62: 830-834. doi: 10.1525/bio.2012.62.9.9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner JD, Chimimba CT. (2005) The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion. Third edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107340992 [DOI]

- Smithers RHN. (1971) The Mammals of Botswana. Museum Memoirs No. 4, The Trustees of the National Museum of Rhodesia, Salisbury, Rhodesia. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Shimada T, Terashima M, Tsuchiya K, Aplin K. (2004) Temporal, spatial, and ecological modes of evolution of Eurasian Mus based on mitochondrial and nuclear gene sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 33: 626-646. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. (2011) MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular Biology and Evolution 28: 2731-2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyrunes F, Britton-Davidian J, Robinson TJ, Calvet E, Denys C, Chevret P. (2005) Molecular phylogeny of the African pygmy mice, subgenus Nannomys (Rodentia, Murinae, Mus): implications for chromosomal evolution. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 36: 358-369. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyrunes F, Catalan J, Sicard B, Robinson TJ, Duplantier JM, Granjon L, Dobigni G, Britton-Davidian J. (2004) Autosome and sex chromosome diversity among the African pygmy mice, subgenus Nannomys (Murinae, Mus). Chromosome Research 12: 369-382. doi: 10.1023/B:CHRO.0000034098.09885.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyrunes F, Catalan J, Tatard C, Cellier-Holzem E, Watson J, Chevret P, Robinson TJ, Britton-Davidian J. (2010) Mitochondrial and chromosomal insights into karyotypic evolution of the pygmy mouse, Mus minutoides, in South Africa. Chromosome Research 18: 563-574. doi: 10.1007/s10577-010-9144-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyrunes F, Perez J, Paintsil SNC, Fichet-Calvet E, Britton-Davidian J. (2013) Insights into the evolutionary history of the X-linked sex reversal mutation in Mus minutoides: clues from sequence analyses of the Y-linked Sry gene. Sexual Development 7: 244-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyrunes F, Watson J, Robinson TJ, Britton-Davidian J. (2007) Accumulation of rare sex chromosome rearrangements in the African pygmy mouse, Mus (Nannomys) minutoides: a whole-arm reciprocal translocation (WART) involving a X-autosome fusion. Chromosome Research 15: 223-230. doi: 10.1007/s10577-006-1116-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

These are the tables (1 and 2) and Appendix.