Recent updates to the guidelines put forth by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the European Association of Urology for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma are discussed and future areas of research to be explored are outlined.

Keywords: Angiogenesis inhibitor, Evidence-based medicine, Mammalian target of rapamycin, Renal cell carcinoma, Vascular endothelial growth factor

Abstract

In the U.S. and Europe, clinical practice guidelines for metastatic renal cell carcinoma have undergone several revisions as a result of the introduction of molecular-targeted therapies. Recently, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the European Association of Urology (EAU) published updated guidelines to reflect these new treatment approaches that provide greater efficacy and better tolerability than the previous standard of care, cytokine therapy with interleukin-2 or interferon-α. Recommendations are classified by line of therapy, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center risk level for survival, and level of evidence. Although many similarities exist, levels of evidence between the NCCN and EAU guidelines have differing designations and definitions, and timing of updates varies. New research developments, such as identification of effective combinations of targeted agents, optimal regimens for sequential therapy, newly designed targeted agents, benefits in special populations, and identification of additional prognostic factors and biomarkers, will prompt continued updates and refinements of today's clinical practice guidelines, with the goal of providing physicians with the most up-to-date clinical consensus upon which to base treatment decisions. Because clinical trial populations may not represent real-life patient populations, recommendations should serve only as a guide and must be tailored to the needs of each patient.

Introduction

Guidelines for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) are rapidly evolving to incorporate the new molecular-targeted therapies that have been approved recently by the U.S. and European regulatory authorities. Data from the phase III randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated these new agents in patients with advanced RCC or mRCC have enabled new recommendations to be derived from high-quality, evidence-based medicine. This article discusses recent updates to the guidelines put forth by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [1] and the European Association of Urology (EAU) [2] and outlines future areas of research to be explored in mRCC.

Characteristics of NCCN and EAU Guidelines

In general, the clinical practice recommendations made by these oncologic and urologic societies are classified by line of therapy, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) risk level for survival, and level of evidence. Line of therapy is typically summarized as first line (treatment-naïve patients) and second line/subsequent (treatment-refractory patients) and is based on the population of patients evaluated in the pivotal clinical trial. Most clinical trials in mRCC consider patients in terms of the MSKCC risk stratification system [3]; therefore, treatment recommendations reflect these levels of survival risk. MSKCC criteria categorize survival risk in mRCC patients as favorable/good, intermediate, or poor on the basis of five pretreatment risk factors. Factors associated with shorter survival are Karnofsky performance status score <80, absence of prior nephrectomy, hemoglobin less than the lower limit of normal, lactate dehydrogenase >1.5× the upper limit of normal, and corrected serum calcium >10 mg/dl. A patient with zero risk factors has a favorable risk, a patient with one or two risk factors has an intermediate risk, and a patient with three or more risk factors has a poor risk for survival [3]. Similar to the MSKCC criteria, the prognostic criteria proposed by the Cleveland Clinic Foundation (CCF) include a hemoglobin level less than the lower limit of normal, lactate dehydrogenase >1.5× the upper limit of normal, and corrected serum calcium >10 mg/dl. The CCF criteria do not include Karnofsky performance status as a prognostic factor, but identify prior radiotherapy and the presence of hepatic, lung, or retroperitoneal lymph node metastases at two or three sites as prognostic risk factors [4].

Whereas line of therapy and MSKCC risk level are uniformly defined parameters among U.S. and European guidelines, the levels of evidence have differing designations and definitions. The NCCN recommendations are divided into categories [1], and the EAU recommendations are assigned a level and a grade [2]. The highest levels of evidence as defined by the NCCN and EAU are summarized in Table 1. In total, the NCCN levels of evidence are defined as follows: category 1 recommendations are supported by high-level evidence and uniform NCCN consensus, category 2A recommendations are supported by lower-level evidence and uniform NCCN consensus, category 2B recommendations are based on lower-level evidence and nonuniform NCCN consensus (but no major disagreement), and category 3 recommendations are based on any level of evidence but reflect major disagreement [1]. A grade A designation by the EAU represents a recommendation that is consistently supported by clinical studies of good quality, at least one of which is a randomized trial. A grade B designation indicates that the recommendation is based on well-conducted clinical studies but without randomized clinical trials. A grade C designation indicates that the recommendation was made despite the absence of directly applicable clinical studies of good quality [2].

Table 1.

Treatment guidelines for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Definitions of highest level of evidence

Results of Recent Phase III Trials with Targeted Agents Necessitating Guideline Updates

As reviewed in detail in the article in this supplement by Hutson [5], the efficacy of molecular-targeted agents has provided new options for a variety of patients with mRCC; briefly, the new findings are summarized below.

Sunitinib, Bevacizumab Plus Interferon-α, and Temsirolimus

The efficacy of sunitinib, bevacizumab plus interferon (IFN)-α, and temsirolimus as first-line therapy was compared with that of IFN-α in separate randomized, phase III trials. Results showed that each of these targeted agents was superior to IFN-α in prolonging progression-free survival or overall survival times, or both [6–10]. The majority of the patients in the sunitinib and bevacizumab plus IFN-α trials were in the favorable or intermediate MSKCC risk groups [6–9], and benefits relative to IFN-α were observed across groups [6, 8, 9]. All patients in the temsirolimus trial were classified by similar criteria as having a poor prognosis, which was equivalent to 74% of patients being classified in the MSKCC poor-risk group and 26% of patients being classified in the MSKCC intermediate-risk group [10]. The results of these trials prompted many changes in first-line therapy recommendations.

Everolimus

The efficacy of everolimus in patients who failed treatment with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (VEGFR TKIs) was superior to that of placebo and best supportive care (BSC) in a recent phase III RCT [11, 12]. The majority of patients in that trial were in the MSKCC favorable- and intermediate-risk groups, and benefits of everolimus relative to placebo were observed across all risk groups [11]. Eligible patients could have received one or two prior therapies for mRCC, but no other immediate post-VEGFR TKI therapy besides everolimus. Prior to the availability of these data, VEGFR TKI–refractory patients did not have another proven viable option for effective therapy. Therefore, the results of that trial established a second-line therapy option after VEGFR TKI failure for these patients, adding new information to the treatment guidelines.

Sorafenib

The efficacy of sorafenib in previously treated patients, >80% of whom had failed prior cytokine-based therapy, was superior to that of placebo, establishing a second-line therapy option for these patients [13, 14] that was added to the treatment guidelines. More than 99% of patients in that trial were of MSKCC favorable or intermediate risk, and efficacy of sorafenib superior to that of placebo was noted in both risk groups [13].

Pazopanib

Most recently, the efficacy of pazopanib was shown to be superior to that of placebo in a phase III RCT that contained a patient population comprised of approximately one half treatment-naïve patients and one half cytokine-pretreated patients, providing data for further treatment recommendations [15]. The majority of patients in the total population were in the MSKCC favorable- and intermediate-risk groups, and the efficacy benefit of pazopanib versus placebo was obtained in all risk groups [15].

Recommendations Prompted by Trial Results

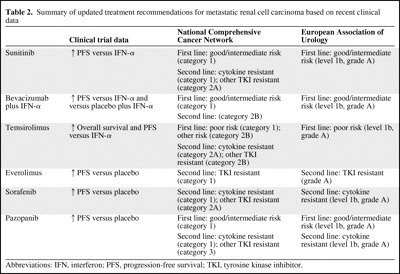

The NCCN guidelines were revised as of October 2009 and published online as version 2.2010 [1]. A full text update to the EAU guidelines occurred in 2007, and a partial update to those became available online in March 2009; these guidelines were most recently updated in April 2010 [2]. Table 2 summarizes the key clinical trial results that led to the current updated recommendations contained in the NCCN and EAU guidelines.

Table 2.

Summary of updated treatment recommendations for metastatic renal cell carcinoma based on recent clinical data

Abbreviations: IFN, interferon; PFS, progression-free survival; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

NCCN

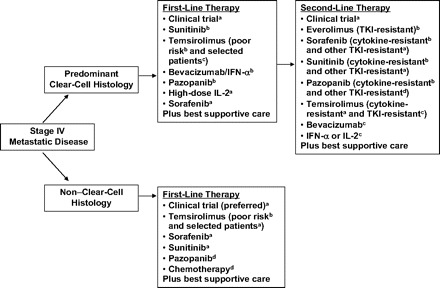

The NCCN guidelines (version 2.2010) recommend a number of options for first- and second-line treatment of mRCC based on evidence from categories 1 to 3 (Fig. 1). For first-line therapy, sunitinib, bevacizumab plus IFN-α, and pazopanib are treatment options for patients with a good or intermediate prognosis; each has a category 1 recommendation. Temsirolimus has a category 1 recommendation for the treatment of patients with poor-prognosis mRCC. In addition, the NCCN also suggests alternative options for selected patients in the first-line setting, such as high-dose interleukin (IL)-2 or sorafenib (both category 2A), temsirolimus (category 2B), and enrollment in a clinical trial (category 2A) [1].

Figure 1.

Summary of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.

aCategory 2A recommendation; bCategory 1 recommendation; cCategory 2B recommendation; dCategory 3 recommendation.

Abbreviations: IFN-α, interferon-α; IL-2, interleukin-2; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

The NCCN guidelines also provide first-line therapy recommendations for patients with non–clear cell mRCC. Temsirolimus has a category 1 recommendation for the treatment of patients with poor-prognosis non–clear cell mRCC and a category 2A recommendation for the treatment of selected patients of other risk groups. NCCN guidelines also recommend sorafenib or sunitinib (both category 2A) and enrollment in a clinical trial (designated as a preferred option). Chemotherapy (gemcitabine, capecitabine, floxuridine, 5-fluorouracil, or doxorubicin [sarcomatoid only]) and pazopanib (both category 3) are also recommended as options.

For second-line therapy, everolimus is the only agent to have an NCCN category 1 recommendation for the treatment of patients who have failed TKIs. Sorafenib, sunitinib, and pazopanib have category 1 recommendations for the treatment of patients after cytokine failure. For the treatment of patients after the failure of other TKIs, sorafenib and sunitinib (category 2A) and pazopanib (category 3) are recommended. Temsirolimus has a category 2A recommendation for the treatment of patients after cytokine failure and a category 2B recommendation for the treatment of patients after TKI failure. Bevacizumab or IFN-α or IL-2 each has a category 2B recommendation, and enrollment in a clinical trial has a category 2A recommendation [1].

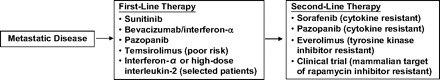

EAU

The EAU guidelines recommend treatment options for patients with mRCC based on levels of evidence 1 to 4 and grades A to C (Fig. 2). For first-line therapy, sunitinib, bevacizumab plus IFN-α, and pazopanib have level 1b, grade A recommendations for the treatment of low- and intermediate-risk patients. For the treatment of high-risk patients, temsirolimus has a level 1b, grade A recommendation [2]. In contrast, IFN-α monotherapy is no longer recommended, a statement that is given a level 1b, grade A evidence rating [2]. However, monotherapy with IFN-α or high-dose bolus IL-2 has a grade A recommendation as a first-line treatment for mRCC in patients with clear cell histology and good prognostic factors [2]. For second-line therapy, everolimus has a grade A recommendation for the treatment of patients after TKI failure; sorafenib and pazopanib each have a level 1b, grade A recommendation for the treatment of patients after cytokine failure; and enrollment in clinical trials is recommended for the treatment of patients after mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor failure, with no level or grade designated [2].

Figure 2.

Summary of the European Association of Urology grade A recommendations.

Cost Considerations

With the increase in the number of approved targeted agents available for the treatment of mRCC at present, compared with only a few years ago, the comparative cost-effectiveness of these therapies in the first- and second-line settings is currently being assessed with respect to life years gained (LYG). Based on data from the phase III Treatment Approaches in Renal Cancer Global Evaluation Trial, the lifetime per-patient costs were $85,571 with sorafenib plus BSC versus $36,634 with BSC alone; thus, the incremental cost of sorafenib was $75,354 per LYG [16]. Similarly, sunitinib had an incremental cost of $67,215 per LYG, compared with IFN-α based on pivotal phase III data [17]. In a recent economic evaluation of sorafenib versus everolimus as second-line therapy for patients who had progressed on sunitinib, everolimus treatment provided an estimated cost advantage of 1.212 LYG over sorafenib use; this translated into an incremental cost of $51,372 per LYG for everolimus [18]. These agents meet the acceptable standards for the cost of care ($50,000–$100,000) [19], but further studies should be done to determine the optimal setting and sequence to improve cost-effectiveness and, most importantly, to improve patient survival outcomes.

Future Directions

New research developments will prompt continued updates and refinements of today's clinical practice guidelines, with the goal of providing physicians with the most up-to-date clinical consensus upon which to base treatment decisions. A number of other targeted agents are currently under investigation for the treatment of mRCC, including axitinib and tivazonib in phase III trials [20–22], and dovitinib in phase I/II trials [23].

Many other areas of research in the treatment of mRCC are also under active investigation. For example, new agents targeting other signaling molecules (e.g., perifosine, which is an alkylphospholipid that inhibits Akt activation), new agents targeting similar signaling molecules in a different way (e.g., VEGF trap, which is a peptide–antibody fusion protein that binds soluble VEGF), and new agents targeting other molecules (e.g., LBH589, which is a histone deacetylase inhibitor that reduces hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression) are in preclinical or early clinical trials. As reviewed in the article in this supplement by Hutson [5], combination therapy with targeted agents is also an active area of investigation in mRCC, and results of a phase II trial of everolimus plus bevacizumab were published recently [24]. In addition, studies are aiming to identify optimal regimens for sequential therapy with targeted agents and optimal therapies for special populations of patients (e.g., elderly patients, patients without prior nephrectomy). Finally, the search for additional prognostic factors and other biomarkers in patients with mRCC remains an area of high interest and activity, because these data may provide clues regarding which patients would respond best to a particular therapy and may help in monitoring the benefits of a particular therapy throughout the treatment course.

Conclusions

Guidelines for the management of mRCC are evolving to incorporate the results of recent phase III clinical trials with molecular-targeted agents; these agents provide efficacy superior to that of previously recommended cytokine therapy or placebo plus BSC, and are generally better tolerated than cytokine therapy. Clinical practice recommendations are classified by line of therapy, MSKCC risk level, and level of evidence.

It is important to note that clinical trial populations may not represent real-life populations of patients, because trial inclusion and exclusion criteria often eliminate numerous patients from study. Therefore, recommendations should serve only as a guide and must be adapted and tailored to the needs of each individual patient. Future directions in mRCC research that may prompt further guideline updates include investigations of new targeted agents, combination therapy with existing targeted agents, optimal sequential therapy with targeted agents, special populations of patients with mRCC, and new prognostic factors and biomarkers.

Acknowledgments

The authors take full responsibility for the content of the paper but thank Stephanie Leinbach, Ph.D., and Amy Zannikos, Pharm.D., supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, for their assistance in manuscript writing and editing.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Ana Molina, Robert Motzer

Manuscript writing: Ana Molina, Robert Motzer

Final approval of manuscript: Ana M. Molina, Robert J. Motzer

References

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Kidney Cancer. V. 2.2010. [accessed March 26, 2010]. Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/kidney.pdf.

- 2.Ljungberg B, Cowan N, Hanbury DC, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma. 2010. [accessed June 21, 2010]. Available at http://www.uroweb.org/gls/pdf/Renal%20Cell%20Carcinoma%202010.pdf.

- 3.Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J, et al. Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2530–2540. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mekhail TM, Abou-Jawde RM, Boumerhi G, et al. Validation and extension of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering prognostic factors model for survival in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:832–841. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutson TE. Targeted therapies for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Clinical evidence. The Oncologist. 2011;16(suppl 2):14–22. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-S2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3584–3590. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Escudier B, Pluzanska A, Koralewski P, et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A randomised, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet. 2007;370:2103–2111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61904-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rini BI, Halabi S, Rosenberg JE, et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa compared with interferon alfa monotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: CALGB 90206. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5422–5428. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.9847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Phase 3 trial of everolimus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Final results and analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer. 2010;116:4256–4265. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib for treatment of renal cell carcinoma: Final efficacy and safety results of the phase III Treatment Approaches in Renal Cancer Global Evaluation Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3312–3318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.5511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1061–1068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao X, Reddy P, Dhanda R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of sorafenib versus best supportive care in advanced renal cell carcinoma [abstract 4604] J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:242s. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Remàk E, Charbonneau C, Négrier S, et al. Economic evaluation of sunitinib malate for the first-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3995–4000. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casciano R, Chulikavit M, Di Lorenzo G, et al. Economic evaluation of everolimus versus sorafenib for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma after failure on treatment with sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 8) doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.04.008. Abstract 941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laupacis A, Feeny D, Detsky AS, et al. How attractive does a new technology have to be to warrant adoption and utilization? Tentative guidelines for using clinical and economic evaluations. CMAJ. 1992;146:473–481. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ClinicalTrials.gov. Axitinib (AG 013736) as Second Line Therapy for Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer [Identifier NCT00678392] [accessed July 21, 2010]. Available at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00678392?term=NCT00678392&rank=1.

- 21.ClinicalTrials.gov. Axitinib (AG-013736) for the Treatment of Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer [Identifier NCT00920816] [accessed July 21, 2010]. Available at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00920816?term=NCT00920816&rank=1.

- 22.ClinicalTrials.gov. A Study to Compare Tivozanib (AV-951) to Sorafenib in Subjects With Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma (TIVO-1) [Identifier NCT1030783] [accessed October 28, 2010]. Available at http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01030783?term=renal+cell+carcinoma+av-951&phase=2&rank=1.

- 23.ClinicalTrials.gov. A Phase I/II Study to Assess the Safety and Efficacy of TKI258 for the Treatment of Refractory Advanced/Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer [Identifier NCT00715182] [accessed July 21, 2010]. Available at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00715182?term=NCT00715182&rank=1.

- 24.Hainsworth JD, Spigel DR, Burris HA, 3rd, et al. Phase II trial of bevacizumab and everolimus in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2131–2136. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]