Abstract

Objective

Atherosclerotic lesions are associated with the accumulation of reactive aldehydes derived from oxidized lipids. Although inhibition of aldehyde metabolism has been shown to exacerbate atherosclerosis and enhance the accumulation of aldehyde-modified proteins in atherosclerotic plaques, no therapeutic interventions have been devised to prevent aldehyde accumulation in atherosclerotic lesions.

Approach and Results

We examined the efficacy of carnosine, a naturally occurring β-alanyl-histidine dipeptide in preventing aldehyde toxicity and atherogenesis in apoE-null mice. In vitro, carnosine reacted rapidly with lipid peroxidation-derived unsaturated aldehydes. Gas chromatography mass-spectrometry analysis showed that carnosine inhibits the formation of free aldehydes - HNE and malonaldialdehyde in Cu2+-oxidized LDL. Preloading bone marrow-derived macrophages with cell-permeable carnosine analogs reduced HNE-induced apoptosis. Oral supplementation with octyl-D-carnosine decreased atherosclerotic lesion formation in aortic valves of apoE-null mice and attenuated the accumulation of protein-acrolein, protein-HHE and protein-HNE adducts in atherosclerotic lesions, while urinary excretion of aldehydes as carnosine conjugates was increased.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that carnosine inhibits atherogenesis by facilitating aldehyde removal from atherosclerotic lesions. Endogenous levels of carnosine may be important determinants of atherosclerotic lesion formation and treatment with carnosine or related peptides could be a useful therapy for the prevention or the treatment of atherosclerosis.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, carnosine, aldehydes, oxidized LDL

It is currently believed that during atherogenesis, arterial lesions develop in response to cumulative injury caused by the retention of lipoproteins within the vessel wall.1 Although specific mechanisms underlying the formation of atherosclerotic lesions remain unclear, it has been suggested that enzymatic and non-enzymatic oxidation of lipoproteins generates immunogenic products that attract leukocytes to the vessel wall.2-4 Phagocytosis of oxidized lipids by macrophages results in the formation of foam cells that give rise to advanced lesions. In agreement with this view, it has been found that products of oxidized lipoproteins accumulate in the atherosclerotic lesions of humans and atherosclerosis-prone animals and that the levels of oxidized lipoproteins in plasma and atherosclerotic lesions is strongly associated with coronary artery disease in human.5-8 Assessments of the contribution of oxidized lipids to atherogenesis in genetically-altered mice have shown that deletion of the lipid-oxidizing enzyme 12/15 lipoxygenase9 decreases atherosclerotic lesion formation. Conversely, deletion of enzymes that promote the removal of lipid peroxidation products, such as paraoxonase, platelet activating factor-acetylhydrolase,10 and aldose reductase11 increases atherogenesis. In addition, some studies suggest that deletion of macrophage receptors that mediate the uptake of oxidized, but not non-oxidized, lipoprotein (e.g., CD36) prevents lesion formation.12 However, the role of these receptors and 12/15 lipoxygenase in atherogenesis remains controversial as other studies have shown that transgenic overexpression of 12/15 lipoxygenase prevents atherosclerotic lesion formation13 and deletion of CD36 does not diminish atherosclerosis in apoE-null mice.14 While such conflicting results could be due to complex gene-diet interactions15 and compensatory changes in gene expression,16 a cause-and-effect relationship, if any, between oxidized lipids and atherogenesis has not been established. Attempts to prevent atherosclerosis by antioxidants such as vitamin E, vitamin C and β-carotene have yielded mixed results in animal models and universally negative results in clinical trials. 17, 18

Inhibition of lipid oxidation at the site of lesion formation is intrinsically problematic. Lipid peroxidation is propagated by highly reactive free radicals that are difficult to quench. Even though naturally occurring antioxidants such as vitamin E efficiently remove secondary free radicals, they do not prevent the initiation of lipid peroxidation by adventitious metal ions. Moreover, for continued quenching, vitamin E and C require recycling by cell constituents, such as reduced glutathione, which are not present in the subintimal space, where most oxidized lipids accumulate. Antioxidant enzymes that detoxify free radicals and oxidants in cells are also not present in this acellular milieu. Furthermore, even in the presence of antioxidants, free radicals that escape quenching generate a host of secondary products that amplify and prolong oxidative injury. Therefore, to be effective, an ideal antioxidant should prevent the initiation of auto-catalytic lipid peroxidation reactions and safely remove secondary products of oxidation without the need for metabolic recycling.

Although most protein antioxidants are enzymes that remove specific reactive oxygen species, dipeptides containing histidine are evolutionary conserved general antioxidants that can prevent the initiation of lipid peroxidation by chelating metals and quenching reactive species. These naturally-occurring dipeptides include carnosine (β-alanyl-histidine), homocarnosine (γ-amino-butyric acid-histidine), anserine (β-alanyl-L1-methylhistidine), balenine (β-alanyl-L3-methylhistidine), and their N-acetylated forms.19 In mammals carnosine is the most abundant and is present in high concentrations in the skeletal muscle, heart and brain.20, 21 Particularly high concentrations of carnosine (5-20 mM) are synthesized in the skeletal muscle, where it is believed to facilitate glycolysis by buffering lactic acid during periods of high metabolic activity.22, 23 Carnosine also quenches singlet oxygen and chelates metals and it has also been shown to form stable adducts with some reactive carbonyl species generated in oxidized lipids. 24, 25 As a result, it could prevent the initiation of lipid oxidation and facilitate the removal of secondary toxic products. The current study was, therefore, designed to examine whether these peptides can inhibit LDL oxidation and inactivate lipid peroxidation products and by doing so decrease atherosclerotic lesion formation in mice. Preliminary results of this study have been previously reported in an abstract form.26

Methods

Detailed Material and Methods are provided in the online-only Supplement at http://atvb.ahajournals.org.

Results

Histidine dipeptides protect low density lipoprotein (LDL) from oxidation

To determine the effects of histidine dipeptides on processes that contribute to atherosclerosis, we first examined whether these peptides inhibit LDL oxidation. While carnosine is synthesized in cells, it is also present in the plasma 27-29 due to dietary ingestion and inter-organ transport. Hence to study how carnosine affect LDL oxidation, which is believed to be an extracellular event, LDL was oxidized by copper in the presence of the dipeptides. The extent of LDL oxidation was estimated by measuring thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS). We found that the addition of 10 mM carnosine decreased LDL oxidation by ∼ 90%. Anserine was moderately effective (∼ 30% inhibition), whereas homocarnosine led to a small (∼ 35%), but statistically significant increase in LDL oxidation (Figure 1A). Thus, amongst the dipeptides tested, carnosine was the strongest inhibitor of LDL oxidation. In addition, carnosine was also effective in preventing LDL oxidation by bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM). At a concentration of 1 mM, carnosine inhibited BMM-mediated LDL oxidation by ∼ 40%, whereas at 10 mM, it completely prevented LDL oxidation (Figure 1B). Moreover, pre-incubation of BMM with a membrane-permeable analog of carnosine, N-acetyl-carnosine (NacCAR), also significantly reduced LDL oxidation suggesting that carnosine inhibits LDL oxidation by both extracellular and intracellular mechanisms. Taken together these observations indicate that carnosine prevents non-enzymatic as well as cell-mediated LDL oxidation as measured by the formation of TBARS.

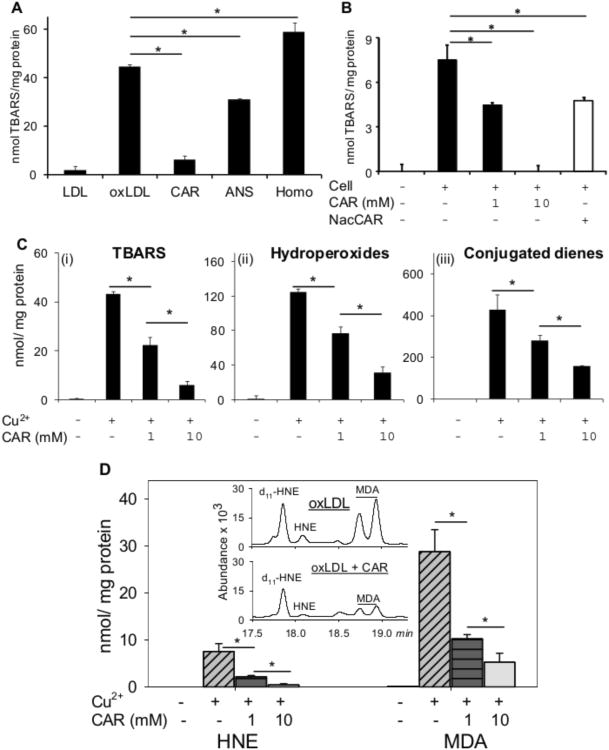

Figure 1. Histidyl dipeptides prevent LDL oxidation.

Oxidation of LDL (measured by the formation of TBARS) in the presence of A, CuSO4 (10 μM) and 10 mM carnosine (CAR), anserine (ANS), or homocarnosine (HOMO) or B, murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM), and carnosine or N-acetyl-carnoine (NAcCAR). For the experiments with N-acetyl-carnosine, BMM were pre-incubated with NacCAR (10 mM) for 24 h and rinsed with PBS prior to the addition of LDL. C, Formation of TBARS (i), hydroperoxides (ii), and conjugated dienes (iii) in LDL oxidized in the presence of Cu2+ and 1 or 10 mM carnosine. D. Inhibition of HNE and MDA formation in Cu2+-oxidized LDL in the presence of carnosine. Inset shows GC-CI/MS identification of MDA and HNE. Values are mean ± SE from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05.

Although measurements of TBARS reflected the generation of lipid-derived carbonyls, these assays provided no information regarding the specific intermediates or end products of lipid oxidation that might be affected by carnosine. Hence, we measured the accumulation of lipid hydroperoxides, generated from peroxyl radicals, conjugated dienes formed by fatty acid fragmentation and free aldehydes malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) which are the major end products of lipid peroxidation. As shown in Figure 1C, similar to TBARS, carnosine prevented the formation of both lipid hydroperoxides and conjugated dienes in Cu2+-oxidized LDL. However, at a concentration of 10 mM, carnosine inhibited the TBARS formation by ∼ 90%, whereas lipid hydroperoxides and conjugated diene formation were prevented by 60-70 %, indicating that carnosine was more effective in preventing the formation of TBARS than hydroperoxides and conjugated dienes. Direct measurements of HNE and MDA by GC/MS showed that carnosine strongly decreased the abundance of these aldehydes in oxidized LDL (Figure 1D). Collectively, these observations suggest that carnosine prevents the initiation of lipid peroxidation, presumably by chelating copper, and that it removes free aldehydes once they are generated.

Chemical reactivity of histidine dipeptides with unsaturated aldehydes

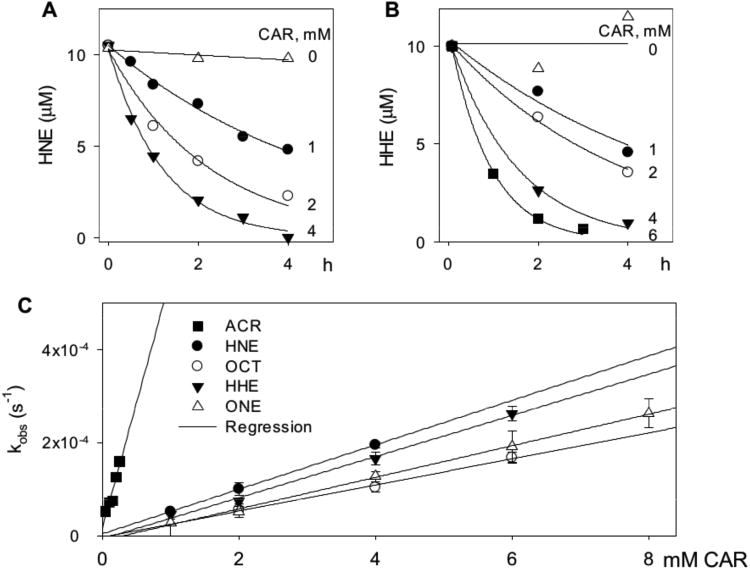

Carnosine can prevent the appearance of lipid-derived free aldehydes such as MDA or HNE by either preventing their formation or by reacting with them once they are formed. To distinguish between these possibilities, we measured the reactivity of carnosine with free aldehydes directly. When we incubated carnosine with the lipid-derived unsaturated aldehydes – acrolein, 4-hydroxyhexenal (HHE), octenal, HNE and 4-oxononenal (ONE), we found that in each case, there was a time-dependent decrease in the concentration of the free aldehyde. The progression of the reaction of carnosine with HNE and HHE is shown in Figure 2 (A, B). The rate of aldehyde loss was best described by a single exponential: At=A0e−kobst; where At is the concentration of aldehyde at time t, A0 is the initial aldehyde concentration and kobs is the apparent rate constant of the reaction. Using this equation, kobs values were calculated at several different concentrations of histidyl dipeptides. The values of kobs displayed a linear dependence on dipeptide concentration (Figure 2C), with a slope equal to the second order rate constant. Such second order rate constants were calculated for the reaction of acrolein and HNE with several histidyl dipeptides. These are listed in Table 1. As shown, we found that all dipeptides that we tested reacted with the aldehydes faster than histidine. The highest rate was observed with anserine, although the reaction of anserine with HNE did not reach completion. The plot of kobs versus [ANS] had a large intercept indicating the formation of dissociable complex with Keq=0.71±0.03 mM that did not lead to the formation of a stable complex. Collectively, these data show that of the series tested, carnosine displayed the most efficient and the most complete reaction with both HNE and acrolein and was therefore used in all subsequent experiments.

Figure 2. Carnosine reacts with oxidized lipids-derived aldehydes.

The rate of disappearance of A, HNE and B, HHE (10 μM each) from a reaction mixture containing indicated concentrations of carnosine in 0.15 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.4. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C and aliquots were removed at indicated times to measure free aldehyde by GC-CI/MS. Data are shown as discrete points and the curves are the best fit of a single exponential equation to the data [y=Ae−kobst]. C, Concentration dependence of kobs. Best fits of the linear dependence were used to calculate the second order rate constants listed in Table 1. ACR indicates acrolein; OCT, octenal; ONE, 4-oxononenal.

Table 1.

Bimolecular rate constants of the reaction of histidine dipeptides with lipid-derived aldehydes.

| Aldehyde | Carnosine (M−1 s−1) | Anserine (M−1 s−1) | Homocarnosine (M−1 s−1) | Histidine (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-HNE | 0.048±0.0025 | 0.087±0.004* | 0.021±0.0022 | 0.0017±0.0002 |

| Acrolein | 0.51±0.03 | 0.58±0.05 | 0.19±0.01 | 0.14±0.01 |

| 4-ONE | 0.034±0.0009 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 4-HHE | 0.044±0.003 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Octenal | 0.028±0.002 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

4-HNE reaction with anserine does not go to completion and reaches an equilibrium with a reverse rate constant of 6.2×10−5±1.5×10−6 s−1, which correspond to Keq= 0.71±0.03 mM. n.d.- Not determined.

Lipid peroxidation generates several aldehydes of diverse structure and variable reactivity. Thus to ensure that the reactivity of carnosine was not limited to only HNE or acrolein, we measured the rate of reaction of carnosine with other alkenals. Second order rate constants of the reaction of carnosine with acrolein, HHE, octenal, HNE and ONE are listed in Table 1. The values of these constants indicate that carnosine reacts with acrolein at a rate 10 times faster than any other aldehyde, whereas it reacts with equal avidity with HNE, HHE, octenal and ONE. The reaction with MDA was inefficient; only 27.5 % of MDA was conjugated after 3 days of incubation with 50 mM carnosine. Chemical identities of carnosine-aldehyde conjugates were established by ESI+-MS/MS analyses (Supplemental Figure I). These analyses showed that carnosine forms Michael adducts with unsaturated aldehydes. Saturated dialdehyde, MDA forms a Schiff base with the terminal amine of the β-alanine residue of carnosine.

Formation of carnosine-aldehyde conjugates in oxLDL

To examine whether in addition to free aldehydes, carnosine also reacts with aldehydes in oxLDL, LDL was oxidized with Cu2+ in the presence of carnosine and carnosine-aldehyde conjugates were resolved by reverse phase HPLC and analyzed on-line by ESI+-MS. Non-oxidized LDL incubated with carnosine served as control. As shown in Supplemental Figure II (i-vi), no carnosine-aldehyde conjugates were detected in native LDL incubated with carnosine. However, several carnosine conjugates (carnosine-MDA, carnosine-acrolein, carnosine-HHE, carnosine-octenal, carnosine-ONE and carnosine-HNE) were detected in LDL oxidized in the presence of carnosine (Supplemental Figure II (vii-xii)). Chemical identities of these carnosine-aldehyde conjugates were established by high resolution mass-spectrometry (Supplemental Figure II (xiii-xviii) and Supplemental Table I). Structural identities of the carnosine-aldehyde conjugates were further confirmed by MS/MS analysis (Supplemental Figure III and Supplemental Table II). Fragmentation patterns of oxLDL-derived carnosine-aldehyde-conjugates were in agreement with reagent standards.

Carnosine protects macrophages from HNE-induced apoptosis

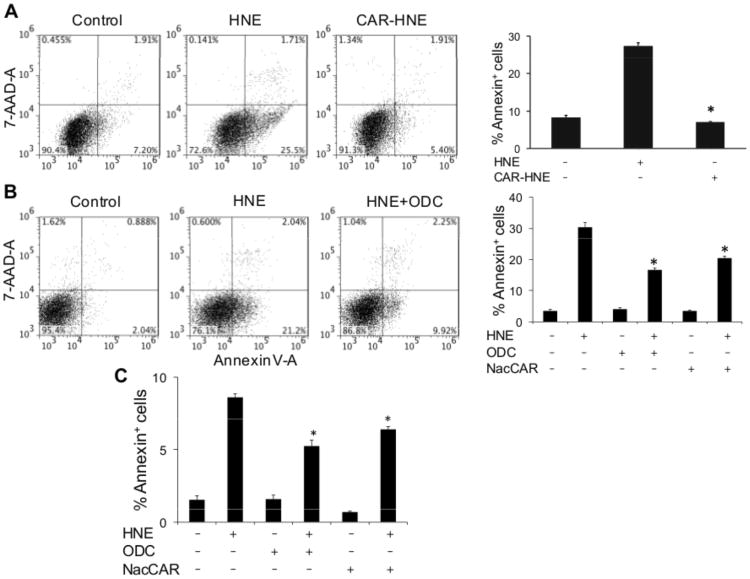

Having found that carnosine reacts with most, if not all, the unsaturated aldehydes generated during lipid peroxidation, we next assessed the biological significance of these reactions by testing whether carnosine decreases biological toxicity of these aldehydes. We found that even though incubation of BMM in HBSS with HNE induced apoptotic cell death, the carnosine-HNE conjugate was not toxic (Figure 3A). These data indicate that conjugation with carnosine significantly diminishes the cytotoxicity of HNE. We also found that BMM pre-loaded with two different cell permeable analogs of carnosine were more resistant to HNE-induced apoptosis than naïve cells in HBSS (Figure 3B). Pre-incubation with carnosine itself also led to a small decrease in HNE-induced cell death, but the decrease was statistically insignificant presumably due to poor permeability. Pre-incubation of BMM with ODC or NacCAR also prevented HNE-induced apoptosis in the cells in the presence of fetal bovine serum (Figure 3C). These observations suggest that carnosine prevents HNE toxicity even in the presence of plasma proteins and are consistent with previous observations showing that carnosine prevents glomerular cell death in vivo.30 Taken together, these observations indicate that carnosine can form conjugates with HNE and therefore, could prevent the toxicity of HNE and related aldehydes.

Figure 3. Carnosine protects macrophages from HNE-induced apoptosis.

Flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow macrophages treated with A, HNE or carnosine-HNE or B, pre-incubated with the cell-permeable carnosine analogs, octyl-D-carnosine (ODC) or N-acetyl-carnosine (NacCAR) for 16h and then incubated for 2h with HBSS or HNE as indicated. Cells were labeled with FITC-Annexin V/7-AAD to monitor apoptosis. The lower right quadrant shows the early apoptotic cells and the upper right quadrant shows the late apoptotic/necrotic cells. Panel C shows the effect of ODC and NacCAR on HNE-induced apoptosis in the presence of 5% fetal bovine serum in RPMI medium. Values are mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments, each conducted in triplicate or quadruplicate. *P<0.01 versus HNE-treated cells.

Carnosine feeding diminishes atherogenesis

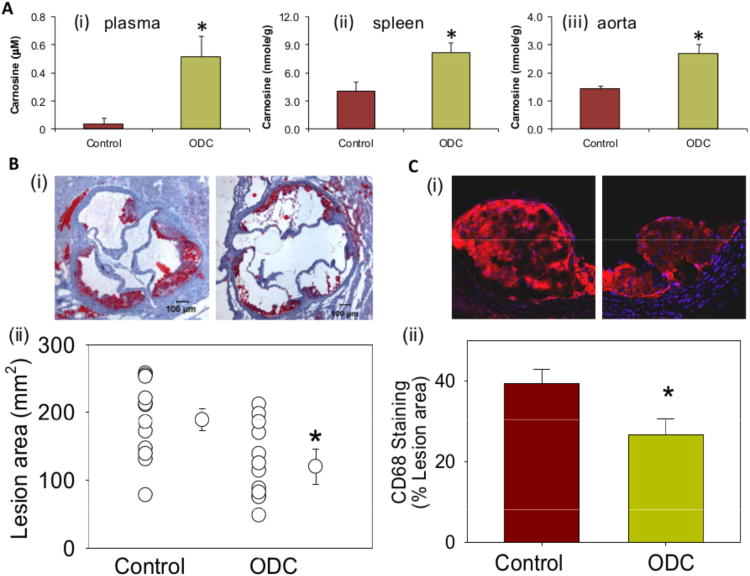

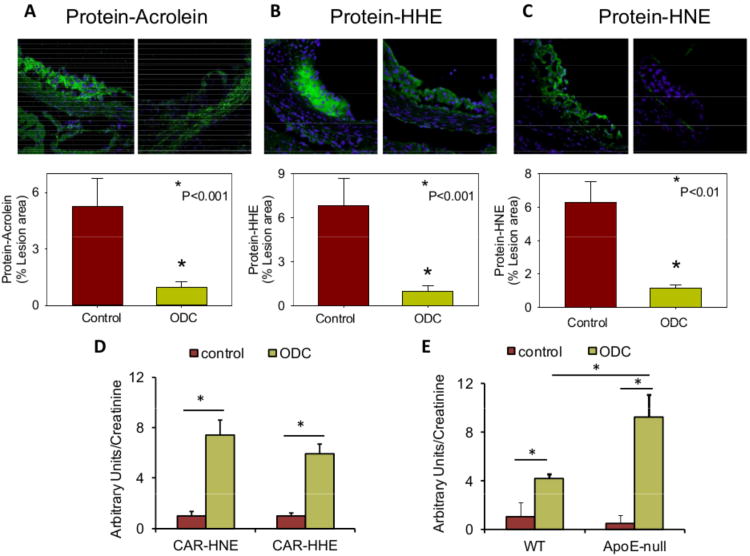

Given our observations that carnosine prevents LDL oxidation, decreases the toxicity of lipid-derived aldehydes and protects cells from aldehyde toxicity, we tested whether treatment with carnosine will prevent atherosclerotic lesions formation. For these experiments, we treated apoE-null mice with a readily bioavailable analog of carnosine, octyl-D-carnosine (ODC) by putting it in their drinking water for 6 weeks. In most mammals, carnosine is cleaved in the plasma by carnosinase, however, because the peptidyl bond in ODC is in the D- rather than L-conformation, this compound is protected from cleavage. Moreover, the use of a cell permeable ester, which has been shown to improve bioavailability of highly hydrophilic compounds such as D-carnosine31, 32 was used to optimize intestinal absorption. The ester is then readily hydrolyzed by tissue or plasma esterases32, 33 generating free carnosine in the plasma. Addition of ODC to the drinking water led to a 13-fold increase in plasma carnosine concentration in these mice (0.04±0.03μM versus 0.52±0.14μM) (Figure 4A(i)) and 2- to 2.5-fold increase in the carnosine content in spleen and aorta (Figure 4A(ii, iii)). Drinking water containing ODC did not affect body weight or plasma cholesterol levels (503±38 mg/dl control vs. 524±30 ODC-fed); however, morphometric analysis of aortic valves recovered from these mice showed that the ODC-treated mice had significantly smaller lesions than untreated mice (Figure 4B). Staining of the aortic valve with anti-CD68 antibody showed a significant decrease in the macrophage content in the lesions of ODC-fed mice as compared with water-fed controls (Figure 4C). Because we found that carnosine reacts with lipid derived aldehydes, we expected to see a significant reduction in aldehyde accumulation in the atherosclerotic lesions of ODC-treated mice. Indeed, our measurements of the protein-adducts of acrolein, HHE and HNE indicated a consistent and robust (70-80%) decrease in the abundance of these adducts in the atherosclerotic lesions of ODC-treated mice (Figure 5A-C). Taken together, these observations indicate that oral intake of ODC prevents the accumulation of protein-aldehyde adducts and macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions and that these changes are accompanied by a decrease in lesion size.

Figure 4. Carnosine-feeding inhibits early phase of atherogenesis and decreases the accumulation of macrophages in lesions.

A, Carnosine level in the plasma (i), spleen (ii) and aorta (iii) of 14-week-old female apoE-null mice maintained on high fat diet and fed ODC (60 mg/kg in drinking water) for 6 weeks starting at 8 weeks of age. Concentration of carnosine was measured by LC/ESI+-MS as described in Methods. B, Lesions in the aortic valve. Lipids were visualized by Oil red O staining. Panels (i) shows the representative photomicrographs of aortic valve of control and ODC-fed mice. Panel (ii) shows the group data. C, Macrophage accumulation in the aortic valve was examined by staining with Alexa 647-conjugated CD-68 antibody. Panels (i) and (ii) shows the representative photomicrographs of aortic valve of control and ODC-fed mice and the group data, respectively. Values are means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus controls.

Figure 5. Carnosine removes aldehydes from atherosclerotic lesions of apoE-null mice.

Photomicrographs of aortic valves stained with A, anti-KLH-acrolein B, anti-KLH-HHE, or C, anti-KLH-HNE antibodies. Mice were treated with ODC as described in Fig. 4. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Values are means ± SEM. #P < 0.01 versus controls. D, Abundance of CAR-HNE and CAR-HHE conjugates in the urine of apoE-null mice, described in panels A-C. Urine was collected 2 days prior to sacrifice. E, Abundance of carnosine-HHE in the urine of 30 week-old female C57BL/6 and apoE-null mice before and after feeding ODC. Control urine was collected for 24 hours. Mice were then fed ODC (60 mg/kg in water by gavage) and urine was collected for an additional 24 hours. MRM traces of the conjugates are shown in Supplemental Figure IV. Values are means ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

Carnosine-aldehyde conjugates in the urine

The decrease in atherosclerotic lesion in apoE-null mice could be due to inhibition of LDL oxidation in the arterial wall. Additionally, as indicated by our preceding experiments, carnosine could also react with lipid oxidation-derived aldehydes and remove them from the lesion. Therefore, we reasoned that if carnosine is removing aldehydes from the lesion, the carnosine-aldehyde conjugates should appear in the urine. To test this possibility, carnosine-aldehyde adducts in urine were quantified by the sensitive multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) technique (Supplemental Figure IV). High levels of carnosine-HNE and carnosine-HHE were observed in the urine of apoE-null mice that were treated with ODC for 6 weeks (Figure 5D) and in which lesion size was decreased. To test whether the urinary levels of the conjugate are associated with lesion formation, we placed wild type (WT) and apoE-null mice on ODC, and measured abundance of carnosine-aldehyde conjugates in the urine. We found that ODC delivered in drinking water appeared in the urine of the mice not only as a free peptide, but also as carnosine-aldehyde conjugates, particularly carnosine-HHE (Figure 5E). Significantly, the level of this conjugate was much higher in the urine of ODC-treated apoE-null than WT mice, indicating that apoE-null mice generate higher levels of lipid peroxidation aldehydes than WT mice and these aldehydes are captured by carnosine and removed in the urine.

Discussion

The major findings of this study are that the endogenous histidyl dipeptide carnosine reacts with a wide range of aldehydes produced by lipid oxidation. Carnosine prevents LDL oxidation and forms stable covalent conjugates with aldehydes generated during LDL oxidation. We also found that carnosine decreases the cytotoxicity of lipid derived aldehydes and that dietary-intake of carnosine prevents early atherosclerotic lesion formation in apoE-null mice. This decrease in atherogenesis was accompanied by decreased accumulation of aldehyde-modified proteins in the lesions and increased appearance of carnosine-aldehyde conjugates in the urine. Taken together, these findings support the notion that dietary intake of carnosine could decrease the formation of atherosclerotic plaques.

Carnosine is an endogenous histidyl dipeptide. In tissues with high metabolic activity - skeletal muscle, heart and brain, carnosine is synthesized from β-alanine and histidine by carnosine synthase. 34, 35 It is also a dietary constituent present in particularly high amounts in meat.36 High levels (10-20 mM) of carnosine in anaerobic white skeletal muscle of birds, horses and pigs are consistent with the view that carnosine prevents tissue acidification by buffering intracellular pH during high glycolytic activity.37, 38 However, carnosine contains highly reactive nucleophilic amines, which are well suited to form covalent conjugates with aldehydes such as those generated in oxidized lipids. Indeed, studies from our laboratory (Figure 2) and others24, 25 show that carnosine reacts avidly with several lipid derived aldehydes. Although these aldehydes can also react with reduced glutathione (GSH) at much higher rates39, 40 that are further accelerated by glutathione S-transferases (GSTs),41, 42 their reaction with carnosine may be a second line of defense under conditions when GSH is depleted. This is consistent with our observation that increasing intracellular carnosine content prevented HNE toxicity, suggesting that despite its slow reactivity, carnosine offers significant protection against aldehyde toxicity even in GSH replete cells and that aldehyde detoxification may be a significant function of endogenous carnosine and related histidyl dipeptides.

The role of carnosine as an aldehyde quencher is supported by our data showing that incubation with carnosine prevented LDL oxidation. At high concentrations (10 mM) carnosine decreased aldehyde generation, without the formation of carnosine-aldehyde conjugates, indicating that at these concentrations carnosine prevents LDL oxidation, presumably by chelating copper. Histidine and histidine containing peptides chelate metals and therefore are quite efficient at preventing free radical generation and lipid peroxidation.43 However, at low concentrations (1 mM), carnosine did not completely prevent lipid oxidation but formed covalent conjugates with aldehydes generated in oxidized lipid. Collectively, these data suggest that carnosine is more efficient at quenching aldehydes than chelating metals and that at physiological levels in tissues other than skeletal muscle (< 1 mM), the aldehyde-quenching effects of carnosine are likely to be more pronounced than its metal chelating abilities. Thus the decrease in atherosclerotic lesion at a steady-state plasma concentration of 0.5-0.6 μM carnosine could be attributed to aldehyde quenching rather than metal chelation.

That carnosine prevents atherogenesis by removing lipid peroxidation-derived aldehydes is further supported by our data showing that oral intake of ODC led to the appearance of HHE and HNE conjugates of carnosine in the urine. These observations suggest that carnosine protects against atherosclerosis by removing reactive aldehydes from the lesions. This view is further supported by the observation that the abundance of protein-aldehyde adducts in the lesions was reduced in the carnosine-fed apoE-null mice. These findings imply that aldehydes such as HHE and HNE are significant contributors to atherosclerotic lesion formation.

Aldehydes such as HNE and ONE are generated from the oxidation of n-6 PUFA and the rate of production of these aldehydes depends upon cell specific expression of 15- or 12-poxygenase.44-46 HHE on the other hand is derived from the oxidation of n-3 PUFAs (α-linolenic acid, eicosapentanoic acid and docosahexanoic acid) and it is generated in humans and rodents at higher concentration than HNE. 47-49 In the present study, we found carnosine-HHE conjugates in WT and ApoE-null mice on a normal chow after a single dose of ODC; however, carnosine-HNE was detected only in mice receiving a high-fat diet suggesting that HHE is the major aldehyde formed during low levels of lipid peroxidation. Moreover, our data showing that HHE is the predominant aldehyde-carnosine conjugate in the urine of ODC-treated apoE-null mice and that its levels in apoE-null mice are higher than in WT mice, indicate that n-3 PUFA are likely to be more readily oxidized in atherosclerotic lesions than n-6 PUFA. However further experiments are required to examine the differential oxidation of n-3 and n-6 PUFAs and the contribution of their products to atherogenesis.

Our observations that dietary carnosine supplementation prevents atherosclerosis lesion formation in apoE-null mice are consistent with the recent work published by Menini et al, 50 who also report that treatment with carnosine prevents atherosclerotic lesion formation. Such concordance of results obtained in two different laboratories strengthens the validity of the observation that carnosine decreases atherosclerosis. Moreover, in addition to revealing the anti-atherogenic role of carnosine, our findings provide a more comprehensive and mechanistic basis of carnosine action by showing that histidyl peptides react directly with lipid peroxidation-derived aldehydes and that carnosine prevents LDL oxidation, aldehyde generation and oxLDL-induced macrophage apoptosis. Collectively, these observations and those of Menini et al, strengthen the rationale for studying the role of endogenous carnosine in atherosclerosis and for testing whether carnosine supplementation in diet could prevent or diminish atherosclerosis in humans. Carnosine is a natural dipeptide, which is present in high concentration in chicken, turkey and beef36, 51 and; therefore, further studies could be designed to determine whether increased consumption of such foods could help prevent or retard atherosclerotic lesion formation. Finally, a decrease in atherosclerosis by carnosine feeding reinforces the view that reactive products of lipid peroxidation play a pivotal role in atherosclerosis.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

This study shows that carnosine, a natural dipeptide, prevents LDL oxidation as well as the cytotoxic effects of reactive aldehydes generated by lipid oxidation. We report that dietary intake of carnosine decreases atherosclerotic lesion formation in mice. These findings suggest that treatment with carnosine or related peptides may be a useful therapy for preventing and decreasing atherosclerotic lesion formation. Carnosine is a dietary supplement and it is well tolerated even at high doses, therefore, its anti-atherogenic effects could be readily tested in humans. Clinical evaluation of carnosine and related peptides could potentially lead to the development of a novel, peptide-based therapy for prevention, treatment and management of atherosclerotic disease.

Despite extensive investigation, the role of LDL oxidation in atherogenesis remains unclear. Our studies showing that treatment with carnosine, which prevents LDL oxidation and the cytotoxic effects of lipid peroxidation products, decreases atherosclerosis support the view that oxidation of LDL and the generation of lipid peroxidation products are important events that contribute to the formation of atherosclerotic lesions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Joseph D. Hoetker, James McCracken, Daniel Riggs and Xiao-Ping Li for excellent technical help. The assistance of Ned Smith from the University of Louisville Biomolecular Mass Spectrometry Core Laboratory is gratefully acknowledged.

Sources of Funding: OAB was partly supported by NIH grant GM103492. This work was also supported in part by NIH grants HL-78825, HL-55477, HL-59378 (to A.B.), and HL95593 and ES17260 (to SS).

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Steinberg D, Witztum JL. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:2311–2316. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.179697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsimikas S, Witztum JL. The role of oxidized phospholipids in mediating lipoprotein(a) atherogenicity. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19:369–377. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328308b622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller YI, Choi SH, Wiesner P, et al. Oxidation-specific epitopes are danger-associated molecular patterns recognized by pattern recognition receptors of innate immunity. Circ Res. 2011;108:235–248. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazen SL. Oxidized phospholipids as endogenous pattern recognition ligands in innate immunity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15527–15531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700054200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsimikas S, Kiechl S, Willeit J, Mayr M, Miller ER, Kronenberg F, Xu Q, Bergmark C, Weger S, Oberhollenzer F, Witztum JL. Oxidized phospholipids predict the presence and progression of carotid and femoral atherosclerosis and symptomatic cardiovascular disease: Five-year prospective results from the bruneck study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2219–2228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsimikas S, Witztum JL. Measuring circulating oxidized low-density lipoprotein to evaluate coronary risk. Circulation. 2001;103:1930–1932. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.15.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stocker R, Keaney JF., Jr Role of oxidative modifications in atherosclerosis. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1381–1478. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00047.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berliner JA, Leitinger N, Tsimikas S. The role of oxidized phospholipids in atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2009;50 Suppl:S207–212. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800074-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cyrus T, Pratico D, Zhao L, Witztum JL, Rader DJ, Rokach J, FitzGerald GA, Funk CD. Absence of 12/15-lipoxygenase expression decreases lipid peroxidation and atherogenesis in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Circulation. 2001;103:2277–2282. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.18.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shih DM, Xia YR, Wang XP, Miller E, Castellani LW, Subbanagounder G, Cheroutre H, Faull KF, Berliner JA, Witztum JL, Lusis AJ. Combined serum paraoxonase knockout/apolipoprotein e knockout mice exhibit increased lipoprotein oxidation and atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17527–17535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910376199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srivastava S, Vladykovskaya E, Barski OA, Spite M, Kaiserova K, Petrash JM, Chung SS, Hunt G, Dawn B, Bhatnagar A. Aldose reductase protects against early atherosclerotic lesion formation in apolipoprotein e-null mice. Circ Res. 2009;105:793–802. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.200568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverstein RL, Li W, Park YM, Rahaman SO. Mechanisms of cell signaling by the scavenger receptor cd36: Implications in atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2010;121:206–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen J, Herderick E, Cornhill JF, Zsigmond E, Kim HS, Kuhn H, Guevara NV, Chan L. Macrophage-mediated 15-lipoxygenase expression protects against atherosclerosis development. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2201–2208. doi: 10.1172/JCI119029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore KJ, Kunjathoor VV, Koehn SL, Manning JJ, Tseng AA, Silver JM, McKee M, Freeman MW. Loss of receptor-mediated lipid uptake via scavenger receptor a or cd36 pathways does not ameliorate atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2192–2201. doi: 10.1172/JCI24061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rong S, Cao Q, Liu M, Seo J, Jia L, Boudyguina E, Gebre AK, Colvin PL, Smith TL, Murphy RC, Mishra N, Parks JS. Macrophage 12/15 lipoxygenase expression increases plasma and hepatic lipid levels and exacerbates atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:686–695. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M022723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Witztum JL. You are right too! J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2072–2075. doi: 10.1172/JCI26130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mrc/bhf heart protection study of antioxidant vitamin supplementation in 20,536 high-risk individuals: A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002(360):23–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sesso HD, Buring JE, Christen WG, Kurth T, Belanger C, MacFadyen J, Bubes V, Manson JE, Glynn RJ, Gaziano JM. Vitamins e and c in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: The physicians' health study ii randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2123–2133. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aldini G, Facino RM, Beretta G, Carini M. Carnosine and related dipeptides as quenchers of reactive carbonyl species: From structural studies to therapeutic perspectives. Biofactors. 2005;24:77–87. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520240109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Dowd JJ, Cairns MT, Trainor M, Robins DJ, Miller DJ. Analysis of carnosine, homocarnosine, and other histidyl derivatives in rat brain. J Neurochem. 1990;55:446–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Dowd JJ, Robins DJ, Miller DJ. Detection, characterisation, and quantification of carnosine and other histidyl derivatives in cardiac and skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;967:241–249. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(88)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Damon BM, Hsu AC, Stark HJ, Dawson MJ. The carnosine c-2 proton's chemical shift reports intracellular ph in oxidative and glycolytic muscle fibers. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:233–240. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parkhouse WS, McKenzie DC. Possible contribution of skeletal muscle buffers to enhanced anaerobic performance: A brief review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1984;16:328–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carini M, Aldini G, Beretta G, Arlandini E, Facino RM. Acrolein-sequestering ability of endogenous dipeptides: Characterization of carnosine and homocarnosine/acrolein adducts by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2003;38:996–1006. doi: 10.1002/jms.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aldini G, Granata P, Carini M. Detoxification of cytotoxic alpha,beta-unsaturated aldehydes by carnosine: Characterization of conjugated adducts by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry and detection by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry in rat skeletal muscle. J Mass Spectrom. 2002;37:1219–1228. doi: 10.1002/jms.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barski OA, Baba SP, Xie ZZ, Hoetker JD, Agarwal A, Sithu SD, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava S. The nucleophilic dipeptide carnosine prevents atherogenesis in apoe-null mice [abstract 14073] Circulation. 2011;124:A14073. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamal MA, Jiang H, Hu Y, Keep RF, Smith DE. Influence of genetic knockout of pept2 on the in vivo disposition of endogenous and exogenous carnosine in wild-type and pept2 null mice. American journal of physiology Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2009;296:R986–991. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90744.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Everaert I, Taes Y, De Heer E, Baelde H, Zutinic A, Yard B, Sauerhofer S, Vanhee L, Delanghe J, Aldini G, Derave W. Low plasma carnosinase activity promotes carnosinemia after carnosine ingestion in humans. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F1537–1544. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00084.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aldini G, Orioli M, Rossoni G, Savi F, Braidotti P, Vistoli G, Yeum KJ, Negrisoli G, Carini M. The carbonyl scavenger carnosine ameliorates dyslipidaemia and renal function in zucker obese rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1339–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riedl E, Pfister F, Braunagel M, Brinkkotter P, Sternik P, Deinzer M, Bakker SJ, Henning RH, van den Born J, Kramer BK, Navis G, Hammes HP, Yard B, Koeppel H. Carnosine prevents apoptosis of glomerular cells and podocyte loss in stz diabetic rats. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. 2011;28:279–288. doi: 10.1159/000331740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beaumont K, Webster R, Gardner I, Dack K. Design of ester prodrugs to enhance oral absorption of poorly permeable compounds: Challenges to the discovery scientist. Current drug metabolism. 2003;4:461–485. doi: 10.2174/1389200033489253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orioli M, Vistoli G, Regazzoni L, Pedretti A, Lapolla A, Rossoni G, Canevotti R, Gamberoni L, Previtali M, Carini M, Aldini G. Design, synthesis, adme properties, and pharmacological activities of beta-alanyl-d-histidine (d-carnosine) prodrugs with improved bioavailability. ChemMedChem. 2011;6:1269–1282. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liederer BM, Borchardt RT. Enzymes involved in the bioconversion of ester-based prodrugs. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 2006;95:1177–1195. doi: 10.1002/jps.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drozak J, Veiga-da-Cunha M, Vertommen D, Stroobant V, Van Schaftingen E. Molecular identification of carnosine synthase as atp-grasp domain-containing protein 1 (atpgd1) J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9346–9356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.095505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horinishi H, Grillo M, Margolis FL. Purification and characterization of carnosine synthetase from mouse olfactory bulbs. J Neurochem. 1978;31:909–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1978.tb00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gil-Agusti M, Esteve-Romero J, Carda-Broch S. Anserine and carnosine determination in meat samples by pure micellar liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1189:444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boldyrev AA. Problems and perspectives in studying the biological role of carnosine. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2000;65:751–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hipkiss AR. Energy metabolism, proteotoxic stress and age-related dysfunction - protection by carnosine. Mol Aspects Med. 2011;32:267–278. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doorn JA, Petersen DR. Covalent modification of amino acid nucleophiles by the lipid peroxidation products 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and 4-oxo-2-nonenal. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:1445–1450. doi: 10.1021/tx025590o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.LoPachin RM, Gavin T, Petersen DR, Barber DS. Molecular mechanisms of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and acrolein toxicity: Nucleophilic targets and adduct formation. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:1499–1508. doi: 10.1021/tx900147g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balogh LM, Atkins WM. Interactions of glutathione transferases with 4-hydroxynonenal. Drug Metab Rev. 2011;43:165–178. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2011.558092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellis EM. Reactive carbonyls and oxidative stress: Potential for therapeutic intervention. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;115:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Babizhayev MA, Seguin MC, Gueyne J, Evstigneeva RP, Ageyeva EA, Zheltukhina GA. L-carnosine (beta-alanyl-l-histidine) and carcinine (beta-alanylhistamine) act as natural antioxidants with hydroxyl-radical-scavenging and lipid-peroxidase activities. Biochem J. 1994;304(Pt 2):509–516. doi: 10.1042/bj3040509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guichardant M, Chen P, Liu M, Calzada C, Colas R, Vericel E, Lagarde M. Functional lipidomics of oxidized products from polyunsaturated fatty acids. Chem Phys Lipids. 2011;164:544–548. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guichardant M, Chantegrel B, Deshayes C, Doutheau A, Moliere P, Lagarde M. Specific markers of lipid peroxidation issued from n-3 and n-6 fatty acids. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:139–140. doi: 10.1042/bst0320139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneider C, Porter NA, Brash AR. Routes to 4-hydroxynonenal: Fundamental issues in the mechanisms of lipid peroxidation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15539–15543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Long EK, Murphy TC, Leiphon LJ, Watt J, Morrow JD, Milne GL, Howard JR, Picklo MJ., Sr Trans-4-hydroxy-2-hexenal is a neurotoxic product of docosahexaenoic (22:6; n-3) acid oxidation. J Neurochem. 2008;105:714–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Long EK, Picklo MJ., Sr Trans-4-hydroxy-2-hexenal, a product of n-3 fatty acid peroxidation: Make some room hne. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guichardant M, Bacot S, Moliere P, Lagarde M. Hydroxy-alkenals from the peroxidation of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids and urinary metabolites. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;75:179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Menini S, Iacobini C, Ricci C, Scipioni A, Blasetti Fantauzzi C, Giaccari A, Salomone E, Canevotti R, Lapolla A, Orioli M, Aldini G, Pugliese G. D-carnosine octylester attenuates atherosclerosis and renal disease in apoe null mice fed a western diet through reduction of carbonyl stress and inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:1344–1356. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yeum KJ, Orioli M, Regazzoni L, Carini M, Rasmussen H, Russell RM, Aldini G. Profiling histidine dipeptides in plasma and urine after ingesting beef, chicken or chicken broth in humans. Amino Acids. 2010;38:847–858. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.