Abstract

Sts (suppressor of T-cell receptor signalling)-1 and Sts-2 are HPs (histidine phosphatases) that negatively regulate TCR (T-cell receptor) signalling pathways, including those involved in cytokine production. HPs play key roles in such varied biological processes as metabolism, development and intracellular signalling. They differ considerably in their primary sequence and substrate specificity, but possess a catalytic core formed by an invariant quartet of active-site residues. Two histidine and two arginine residues cluster together within the HP active site and are thought to participate in a two-step dephosphorylation reaction. To date there has been little insight into any additional residues that might play an important functional role. In the present study, we identify and characterize an additional residue within the Sts phosphatases (Sts-1 Arg383 or Sts-2 Arg369) that is critical for catalytic activity and intracellular function. Mutation of Sts-1 Arg383 to an alanine residue compromises the enzyme’s activity and renders Sts-1 unable to suppress TCR-induced cytokine induction. Of the multiple amino acids substituted for Arg383, only lysine partially rescues the catalytic activity of Sts-1. Although Sts-1 Arg383 is conserved in all Sts homologues, it is only conserved in one of the two sub-branches of HPs. The results of the present study highlight an essential role for Sts-1 phosphatase activity in regulating T-cell activation and add a new dimension of complexity to our understanding of HP catalytic activity.

Keywords: histidine phosphatase, phosphoglycerate mutase, suppressor of T-cell receptor signalling (Sts), T-cell receptor signalling (TCR signalling)

INTRODUCTION

Within the mammalian immune system, T-cells play a central role in the recognition and elimination of invasive microorganisms [1]. They fight foreign pathogens both directly, by eliminating cells that harbour intracellular microbes, or indirectly, by mobilizing and activating other cellular components of the immune system through the production of numerous cytokines [2]. However, they also pose a potential danger to their host in that many of the properties that make them effective mediators of the immune response can be turned inadvertently against host tissue [3–5]. The potent immunosuppressive properties of T-cells are activated following stimulation of the TCR (T-cell receptor). The TCR activates numerous biochemical pathways within T-cells that can ultimately lead to T-cell proliferation, cytokine secretion and cytolytic activity [6]. Not surprisingly, T-cells have evolved a variety of mechanisms to ensure that the TCR-mediated targeting of foreign microbes occurs with remarkable fidelity and selectivity [7,8]. One such mechanism involves multiple overlapping levels of positive and negative regulation within the biochemical signalling networks downstream of the TCR [9–11]. Disruption of this regulation has been linked to numerous pathologies, ranging from immune-deficiencies to autoimmune disorders [12,13]. Developing targeted therapeutics that can ameliorate immune disorders requires fully understanding the many regulatory mechanisms that underlie the control of T-cell activation thresholds.

Two homologous proteins, Sts (suppressor of T-cell receptor signalling)-1 and Sts-2, have been shown to negatively regulate TCR signalling pathways in a redundant fashion [14]. The importance of the Sts proteins in regulating lymphocyte responses is shown by the fact that mice lacking both Sts-1 and Sts-2 have hyper-reactive T-cells and an increased susceptibility to autoimmunity in a mouse model of the human disease multiple sclerosis [15]. Several genome-wide association studies have also underscored the connection between the Sts proteins and a variety of different autoimmune disorders, such as diabetes, arthritis, vitiligo and coeliac disease [16–19]. Although the exact intracellular mechanism(s) of action of the Sts proteins have yet to be resolved, it has become clear that the Sts proteins are members of a superfamily of enzymes known as HPs (histidine phosphatases) [20]. The Sts phosphatase domain is located in the C-terminal portion of each molecule, with Sts-1 having a significantly higher in vitro phosphatase activity than Sts-2 towards artificial substrates [21,22]. The Sts proteins are distinct among other HPs in having unique protein–protein interaction domains that contribute to their function. The current models of Sts function suggest these domains play key roles in localizing the Sts proteins to specific intracellular regions or in targeting the phosphatase domain to specific intracellular substrates [14,23].

HPs comprise a large superfamily of diverse enzymes whose origins are evolutionarily ancient [20]. The superfamily is divided into two branches, with Branch 1 consisting of PGM (phosphoglycerate mutase)-like enzymes and Branch 2 consisting of enzymes known as AcPs (acid phosphatases) [24]. The Sts proteins themselves are in Branch 1 of the HPs, with such diverse enzymes as PGM (EC 5.4.2.1), fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (EC 3.1.3.46), glucose-1-phosphatase (EC 3.1.3.10), lysophosphatidic AcP (EC 3.1.3.2) and prostatic AcP (EC 3.1.3.48) all being included within the superfamily [20]. Despite large differences in their primary amino acid sequence, overall tertiary structure and substrate specificity, all HPs possess four invariant amino acids. In particular, two histidine and two arginine residues adopt a signature conformation within the phosphatase active site and are required for enzyme activity. One histidine residue serves as the nucleophile during the first step of the reaction, whereas the second histidine and the two invariant arginines cluster together around the nucleophile [25]. Among other functions, the latter three amino acids are thought to play an important role in correctly orientating the substrate for hydrolysis and interacting with water molecules within the active site [26]. To date, studies characterizing the mechanism of HP catalytic activity have focused on the role of these four residues. Indeed, there have been few published studies describing additional amino acids within the phosphatase active site that are essential for catalytic activity and intracellular function. In the present study, we describe an essential role for an additional arginine residue found within the Sts active sites, Sts-1Arg383 and Sts-2 Arg369. This arginine residue is conserved in all Sts homologues and in Branch 2 AcPs, but is absent in the vast majority of Branch 1 enzymes. Interestingly, we find that although mutation of Sts-1 Arg383 reduces, but does not eliminate, in vitro phosphatase activity, the presence of Arg383 is absolutely required for the negative regulatory function of Sts-1 in T-cells. These results provide further insight into the Sts-mediated regulation of the T-cell immune response and add a new dimension to our understanding of HP catalytic activity.

EXPERIMENTAL

Cells, cDNA mutants and transfection

HEK (human embryonic kidney)-293 cells were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum), 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. All cDNA mutants were constructed by PCR mutagenesis and sequenced to confirm the presence of only the desired mutation. Expression plasmids were transfected into HEK-293 cells using calcium phosphate-based transfection. Jurkat cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. At least 2 days before transfection, the Jurkat cells were switched to an antibiotic-free high-glucose RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen A10491) containing 4.5 g/l d-glucose, 1.5 g/l sodium bicarbonate, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM Hepes and 300 mg/l l-glutamine, supplemented with 10% FBS, and grown at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells/ml. The Jurkat cells were transfected using the Amaxa Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V (Lonza) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

For immunoprecipitation, transfected HEK-293 cells were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer [50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA and 1% Triton X-100] and cleared by centrifugation for 15 min at 20000 g. Lysates were mixed with an anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) for at least 1 h and Protein A–Sepharose beads for another hour. Beads were washed three times with ice-cold lysis buffer and three times with room temperature (23°C) phosphatase assay buffer. Immunoprecipitates were then used for phosphatase assays using pNPP (p-nitrophenyl phosphate), OMFP (3-O-methylfluorescein phosphate) or a Zap-70 (ζ-associated protein of 70 kDa)-derived phosphopeptide (GSVYESPpYSDPEEL; Celtek Peptides) as substrates. For immunoblotting, lysates or immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS/PAGE (10% gels) and electrotransferred on to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 3% BSA in Tris-buffered saline, the blots were probed with anti-FLAG antibodies followed by infra-red dye-conjugated secondary antibodies. Signals were detected using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR).

In vitro phosphatase assay

FLAG-tagged Sts-1 or Sts-2 proteins transiently expressed in HEK-293 cells were immunoprecipitated and immobilized on Protein A–Sepharose beads. The immunoprecipitates were incubated in a 100 µl reaction mixture containing 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.2), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT (dithiothreitol), 2.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg/ml BSA and 0.5 mM of the substrate (pNPP, OMFP or Zap-70 phosphopeptide) for 15 min (Sts-1) or 2 h (Sts-2) at 37°C. Phosphate hydrolysis of pNPP and OMFP were determined by measuring absorbance at 405 nm and 477 nm respectively. Phosphopeptide hydrolysis was determined using the Malachite Green Phosphatase Assay Kit (Echelon Biosciences) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Continuous assays using a recombinant Sts-1 HP domain (Sts-1HP) fused to MBP (maltose-binding protein) were performed as described previously [22]. The results of the present study are all representative of multiple experiments with two or three replicates per condition per experiment.

Zap-70 dephosphorylation assay

To assess Zap-70 dephosphorylation in vivo, 15 µg of Sts-1 expression constructs were co-transfected with plasmids (also 15 µg each) encoding Lck (lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase), Zap-70 and a CD8-ζ chain chimaera into HEK-293 cells. Zap-70 was immunoprecipitated from the lysates and the level of Zap-70 tyrosine phosphorylation was determined by immunoblotting with the 4G10 antibody (Millipore).

Luciferase assay

Jurkat cells were transfected with Sts-1 expression plasmids, a firefly luciferase expression construct driven by NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T-cells)-binding sequences and a Renilla luciferase construct for normalization. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were stimulated by plating on to OKT3-coated 96-well plates (Biolegend) at a density of 0.2 × 106 cells per well for 8 h, after which luciferase activities were determined using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

T-cell culture, retroviral infection and intracellular cytokine analysis

Naïve peripheral T-cells were obtained from Sts-1/2−/− mice. The mice were housed and bred under specific pathogen-free conditions according to institutional guidelines. The animal work was conducted under guidelines established and approved by the Stony Brook IACUC (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee). To obtain T-cells, dissected spleens were crushed in PBS containing 2% FBS, the red blood cells were lysed by the addition of ACK lysis buffer (pH 7.2) and the debris was removed by straining through a 70 µM filter (Becton Dickinson). Splenocytes were cultured for 24 h in the presence of 1 µg/ml anti-CD3 antibody (145-2C11; BD Biosciences) and 1 unit/ml IL-2 (interleukin 2; Peprotech) and then spin-infected with a retrovirus carrying a bicistronic cassette expressing the gene of interest and GFP (green fluorescent protein) downstream of an IRES (internal ribosome entry site). Infected T-cells were allowed to grow for 48 h in the presence of IL-2, and 1 × 106 cells were plated and then stimulated with the indicated amount of anti-CD3 antibody. Following 4 h of stimulation in the presence of 0.1 µg/ml Brefeldin A cells were processed for intracellular IFNγ (interferon γ) staining using a Cytofix/Cytoperm Fixation/Permeabilization Kit (Becton Dickinson Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. GFP+ cells were analysed for IFNγ expression using a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur flow cytometer.

RESULTS

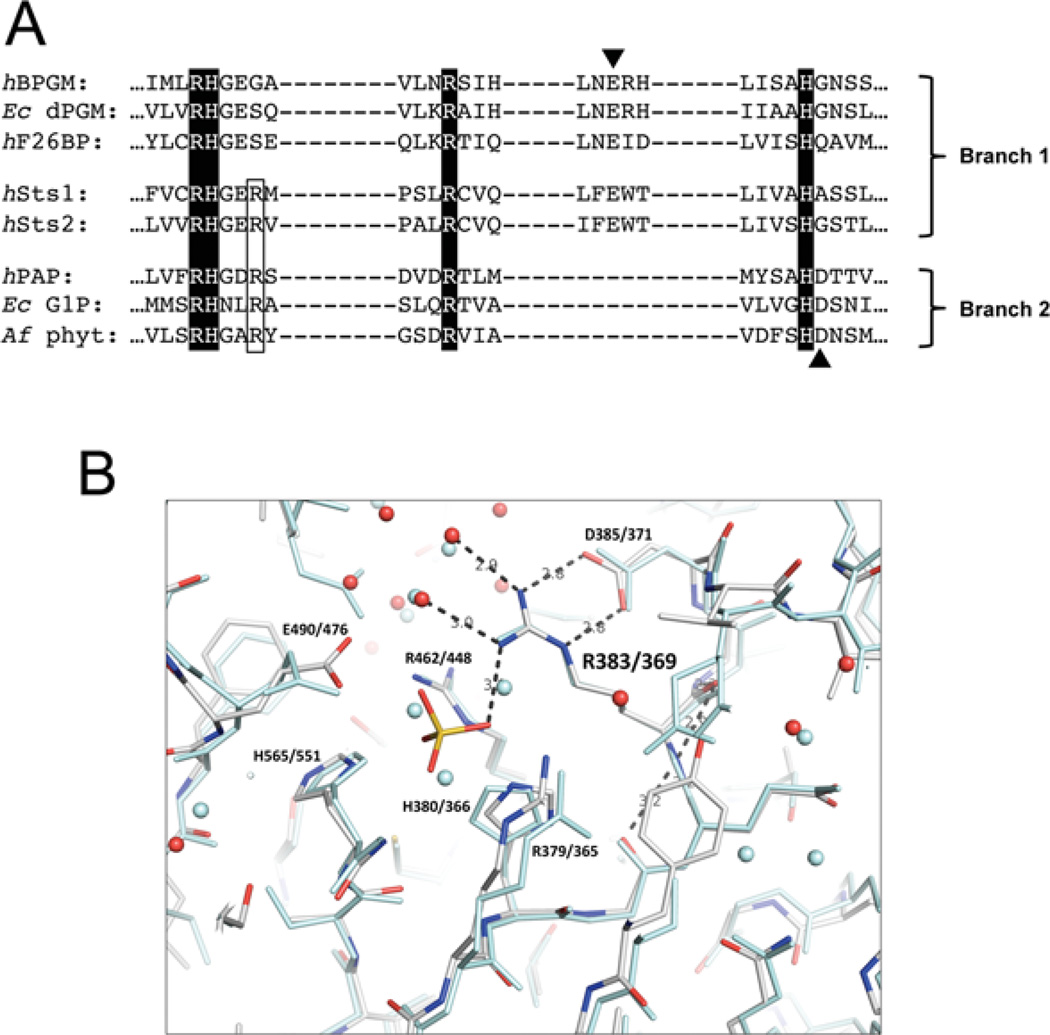

Upon aligning the Sts proteins with different members of the HP superfamily, we noted the presence of a conserved arginine residue that is found in Branch 2 AcPs, but absent in most Branch 1 enzymes (Figure 1A and Supplementary Figure S4 at http://www.biochemj.org/bj/453/bj4530027add.htm) [20]. The conserved arginine residue is adjacent to the invariant RHG motif and occupies position 383 and 369 within Sts-1 and Sts-2 respectively. Inspection of the Sts-1 catalytic pocket reveals the side chain of Arg383 is positioned alongside the well-characterized core catalytic residues Arg379, His380, Arg462 and His565 (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1A at http://www.biochemj.org/bj/453/bj4530027add.htm) [21]. Together, the three arginine residues form a triad of highly electropositive residues with their guanidinium-capped side chains projected directly into the cavity that defines the phosphatase active site. Sts-2 Arg369 is positioned identically, adjacent to Sts-2 Arg365, His380, Arg448 and His551 (Figure 1B) [27]. Structural models of several Branch 2 enzymes indicate that the corresponding arginine residue adopts a similar conformation (Supplementary Figure S1B) [28–30]. The location of this arginine residue within the active site and its high degree of conservation suggest a functional role in Sts catalytic activity, despite the absence of a corresponding residue in the Branch 1 enzymes.

Figure 1. Presence of a conserved arginine residue alongside the catalytic quartet in the Sts-1 active site.

(A) Sts phosphatase domain sequences were aligned with sequences of enzymes representing the PGM and AcP branches of the HP superfamily: human bisphosphoglycerate mutase (hBPGM), Escherichia coli cofactor-dependent PGM (Ec dPGM), human fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (hF26BP), human prostatic acid phosphatase (hPAP), E. coli glucose-1-phosphatase (Ec G1P) and Aspergillus fumigatus phytase (Af phyt). The invariant catalytic quartet residues are highlighted and the acidic residues that are thought to act as proton donors during the second step of the catalytic reaction are indicated with arrowheads. The conserved arginine residue that is the subject of this study is outlined. (B) Superimposition of Sts-1 and Sts-2 active sites, illustrating hydrogen-bond interactions between Arg383/369 (Sts-1/Sts-2) and elements within the catalytic pocket. The phosphate molecule is derived from phosphate buffer in which crystals were soaked. Sts-1 residues are rendered in colour and those of Sts-2 are in pale blue.

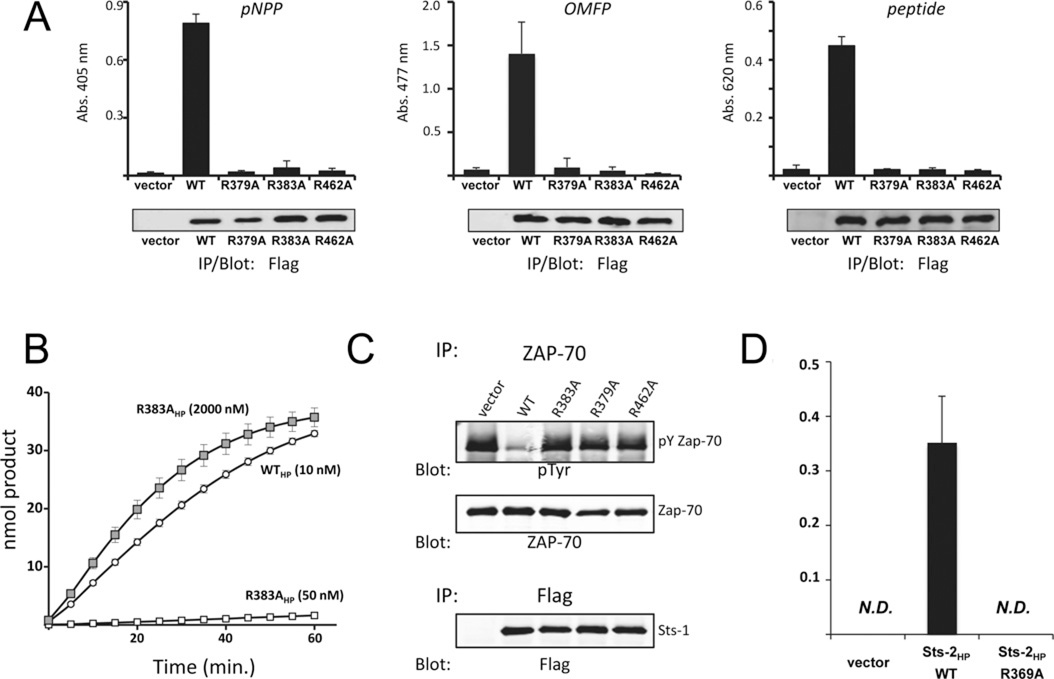

To determine whether Arg383 plays a role in Sts-1 catalytic activity, we generated a mutant Sts-1 in which the alanine residue was substituted for Arg383, and evaluated its phosphatase activity in three separate assays. First, Sts-1 R383A was expressed in HEK-293T cells and evaluated for enzymatic activity in an immune complex phosphatase reaction [21]. In contrast with wild-type Sts-1, but similar to the Sts-1 R379A and R462A mutants, Sts-1 R383A failed to hydrolyse the model substrate pNPP (Figure 2A, left-hand panel). Sts-1 R383A was also inactive towards additional diverse substrates that were hydrolysed readily by wild-type Sts-1. These include the phosphorylated fluorescein derivative OMFP (Figure 2A, middle panel) and a tyrosine phosphorylated peptide derived from a putative Sts-1 intracellular target, the T-cell tyrosine kinase Zap-70 (Figure 2A, right-hand panel). Secondly, we generated recombinant proteins and compared the in vitro activity of the HP domain of wild-type Sts-1 (Sts-1HP, 10 nM) and R383AHP (10 nM–1 µM). Low concentrations of R383AHP displayed minimal hydrolytic activity, but the hydrolytic activity of R383AHP was evident when excessive concentrations (1 µM) of the enzyme were used (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure S2 at http://www.biochemj.org/bj/453/bj4530027add.htm). The Km value for pNPP of R383AHP (1 µM) was determined to be 3.3 mM, in contrast with a value of 1.1 mM for Sts-1HP (Supplementary Figure S2). Finally, to evaluate the role of Sts-1 Arg383 within a cellular context, we utilized a cell-based Zap-70 dephosphorylation assay. Wild-type or mutant Sts-1 was co-expressed with Zap-70 in HEK-293T cells under conditions leading to the latter’s tyrosine phosphorylation [31]. We observed that unlike wild-type Sts-1, but similar to the inactive Sts-1 mutants R379A and R462A, Sts-1 R383A failed to dephosphorylate Zap-70 (Figure 2C). To determine whether conservation of the equivalent arginine residue is required for the catalytic activity of Sts-2, we generated the Sts-2 R369A mutant and evaluated its activity by immune complex phosphatase reaction. The results mirrored those obtained for Sts-1. Specifically, we observed that Arg369 was required for Sts-2 phosphatase activity (Figure 2D). Altogether, the results of the present study demonstrate a requirement for Sts-1 Arg383 and Sts-2 Arg369 for efficient Sts enzymatic activity. Thus, in addition to the well-defined quartet of two histidine and two arginine residues that has heretofore defined the motif required for HP activity, Sts phosphatase activity requires the presence of an additional arginine residue within the active site.

Figure 2. Requirement for Arg383/Arg369 in Sts-1/Sts-2 catalytic activity.

(A) Immune complex phosphatase activity assays of wild-type (WT) Sts-1HP and the indicated mutants using as substrates pNPP (left-hand panel), OMFP (middle panel) or a phospho-tyrosine phosphopeptide (right-hand panel) demonstrate the requirement for Sts-1 Arg383 for catalytic activity. Sts-1 R379A and Sts-1 R462A serve as negative controls. Results are means ± S.D. representative of multiple experiments with two replicates for each condition throughout. Abs., absorbance. (B) Phosphatase activity time course with recombinant wild-type Sts-1HP (WTHP) and Sts-1HP R383A at the indicated concentrations demonstrates impairment of Sts-1HP R383A. The concentration of pNPP was 1 mM. (C) Co-expression of Zap-70 in HEK-293 cells with the indicated Sts-1 constructs indicates Sts-1 R383A is unable to dephosphorylate full-length Zap-70. The levels of Zap-70 phosphorylation were assessed by anti-phospho-tyrosine (pY/pTyr) immunoblotting. The loading controls are indicated. (D) OMFP hydrolysis activity of Sts-2 R369A is impaired relative with wild-type Sts-2, as demonstrated in an immune complex phosphatase assay. Results are means ± S.D. IP, immunoprecipitation; N.D., not determined.

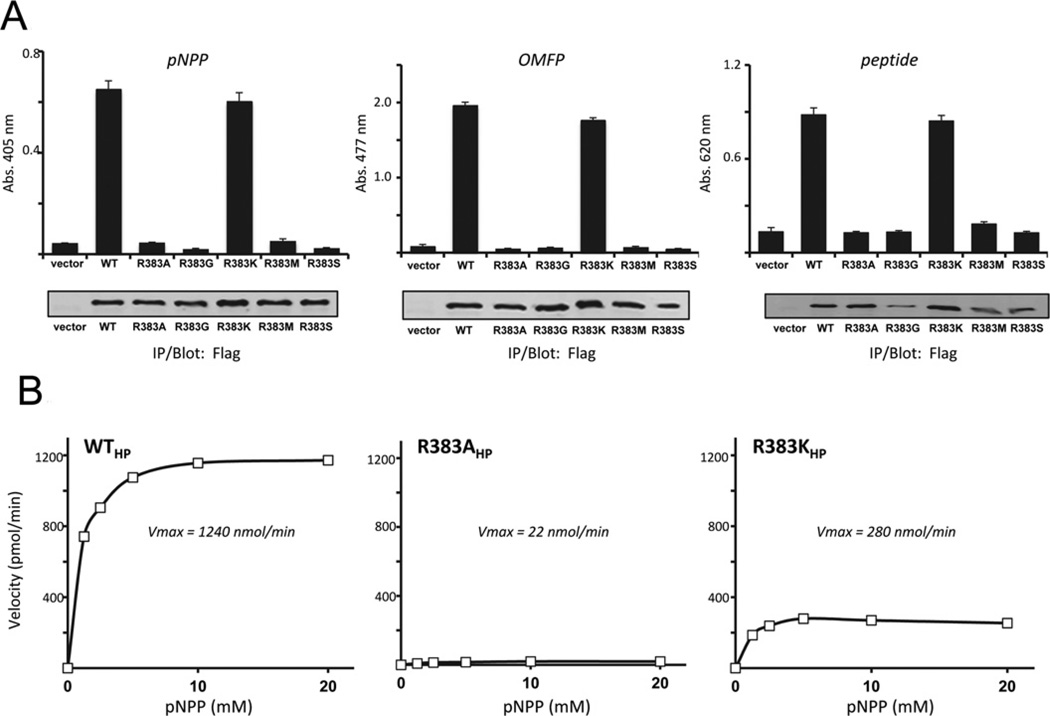

To gain further insight into the characteristics of Sts-1 Arg383 required for enzyme activity, we generated mutant Sts-1 proteins in which Arg383 was replaced with a variety of alternative amino acids. To mimic the active-site configuration of Branch 1 enzymes we generated mutants that replaced Arg383 with the two predominant amino acids found at the equivalent position in Branch 1 enzymes, glycine and serine (see Figure 1A) [20]. We also generated mutants in which lysine and methionine residues were substituted for Arg383, the former to evaluate the need for a basic side chain and the latter to investigate the need for a bulky aliphatic residue. Each mutant was expressed in HEK-293T cells, isolated by immunoprecipitation and evaluated for phosphatase activity relative to wild-type Sts-1. The mutants in which Arg383 was replaced with a glycine, serine or methionine residue displayed little or no activity towards pNPP, OMFP or a phosphopeptide (Figure 3A). In contrast, when lysine was substituted for an arginine residue at position 383, significant in vitro hydrolytic activity toward the three substrates was observed (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Lysine partially rescues Sts-1 R383A activity towards model substrates.

(A) Substitution of Sts-1 Arg383 with a lysine residue yields a partially active enzyme towards pNPP (left-hand panel), OMFP (middle panel) and a peptide (right-hand panel), unlike substitution with glycine, serine or methionine. Results are means ± S.D. representative of duplicate experiments with two replicates for each condition throughout. Abs. absorbance; IP, immunoprecipitation; WT, wild-type. (B) Substrate saturation analysis with purified recombinant wild-type Sts1HP (WTHP), R383AHP and R383KHP against various concentrations of pNPP (1.25, 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 mM) reveals the contribution of the lysine residue to catalytic activity. Initial velocities were obtained from the slopes of the time course of the hydrolysis reactions and plotted against substrate concentration. Kinetic parameters were calculated using SigmaPlot 11 (Systat Software) using a dynamic curve-fitting function to a one-site saturation ligand-binding equation y = Bmax x/(KD + x).

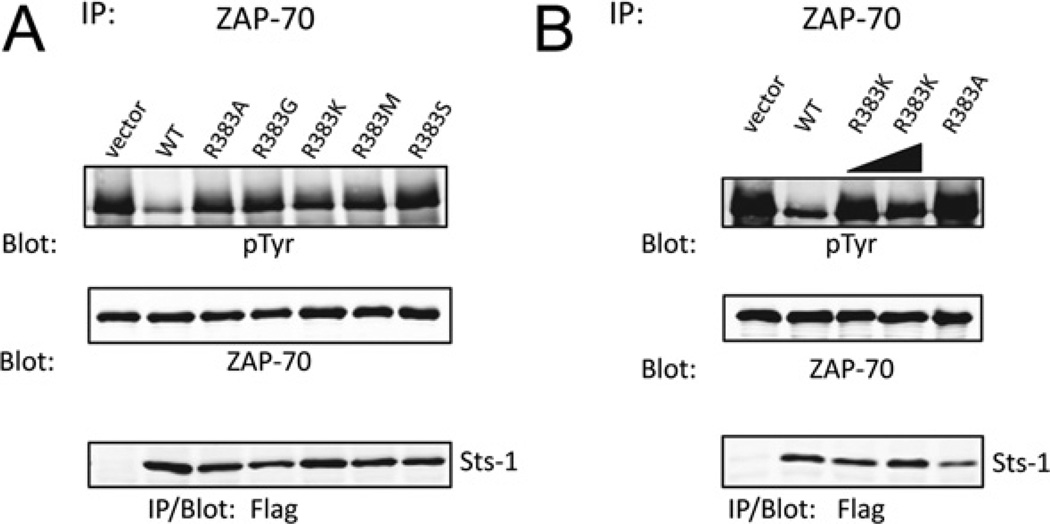

To more precisely define the effects of an arginine compared with a lysine residue at position 383, we utilized recombinant protein and evaluated the rate of the phosphatase reaction at a defined enzyme concentration and different substrate concentrations (1–20 mM). The initial reaction velocities at each substrate concentration were calculated and plotted as a function of the substrate concentration. We observed that the substitution of Arg383 with a lysine residue was not as deleterious as the alanine substitution, with reaction velocities of R383K approximately one quarter of the reaction velocities of wild-type Sts-1HP (Figure 3B). Finally, we addressed the unique requirement for Arg383 for the interaction between Sts-1 and a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein in a cellular context. As in the case with the alanine substitution, replacing Arg383 with glycine, serine or methionine residue rendered Sts-1 unable to target tyrosine-phosphorylated Zap-70 (Figure 4A). However, it was evident that Sts-1 R383K possessed limited protein phosphatase activity. Specifically, we observed a reduction in Zap-70 tyrosine phosphorylation to levels that were intermediate between those observed in the presence of active wild-type Sts-1 and inactive Sts-1 R383A. However, increasing the level of expression of Sts-1 R383K led to more substantial dephosphorylation of Zap-70 (Figure 4). Thus substituting Arg383 with another basic amino acid, albeit one whose side chain has a lower pKa value, is not as deleterious as neutral or acidic amino acid substitutions. Cumulatively, the correlation between the basicity of residue 383 and the apparent enzyme activity of Sts-1HP suggest that one of the primary functions of Sts-1 Arg383 is to provide additional localized positive charge within the active site.

Figure 4. Lysine partially rescues Sts-1 R383A phosphatase activity towards Zap-70.

Substitution of Sts-1 Arg383 with a lysine residue yields a partially active enzyme toward Zap-70, unlike substitution with glycine, serine or methionine. The indicated mutants were co-expressed with Zap-70 in HEK-293 cells (A) and a titration of Sts-1 R383K was evaluated (B). IP, immunoprecipitation; pTyr, phospho-tyrosine; WT, wild-type.

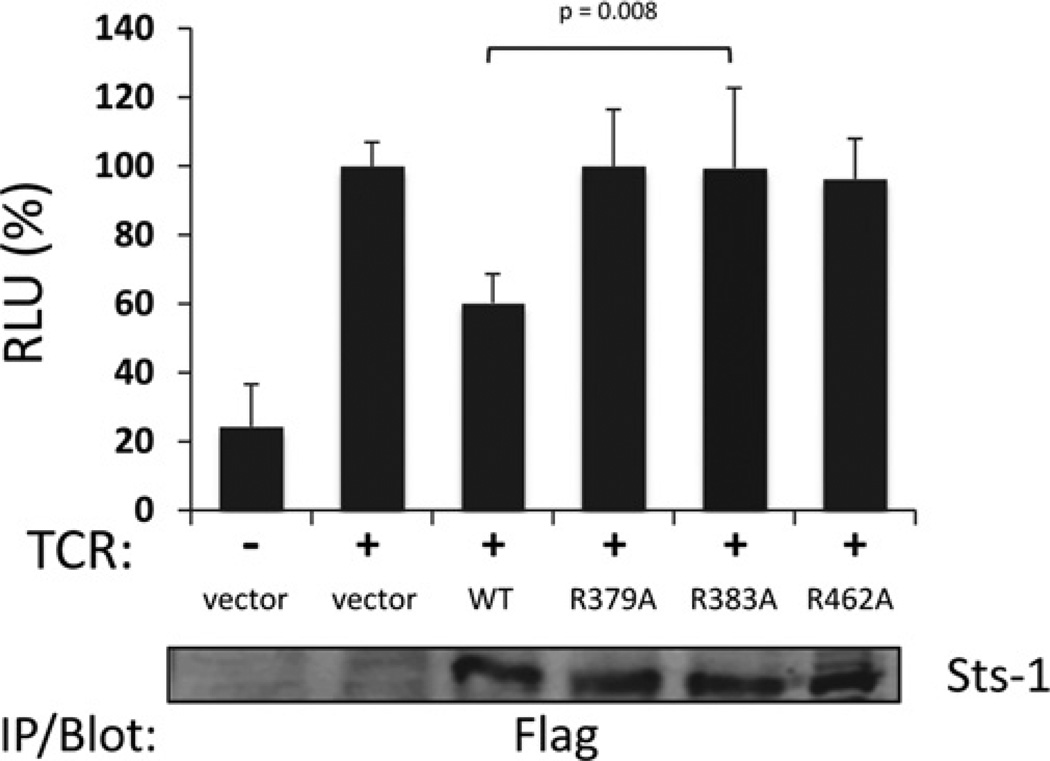

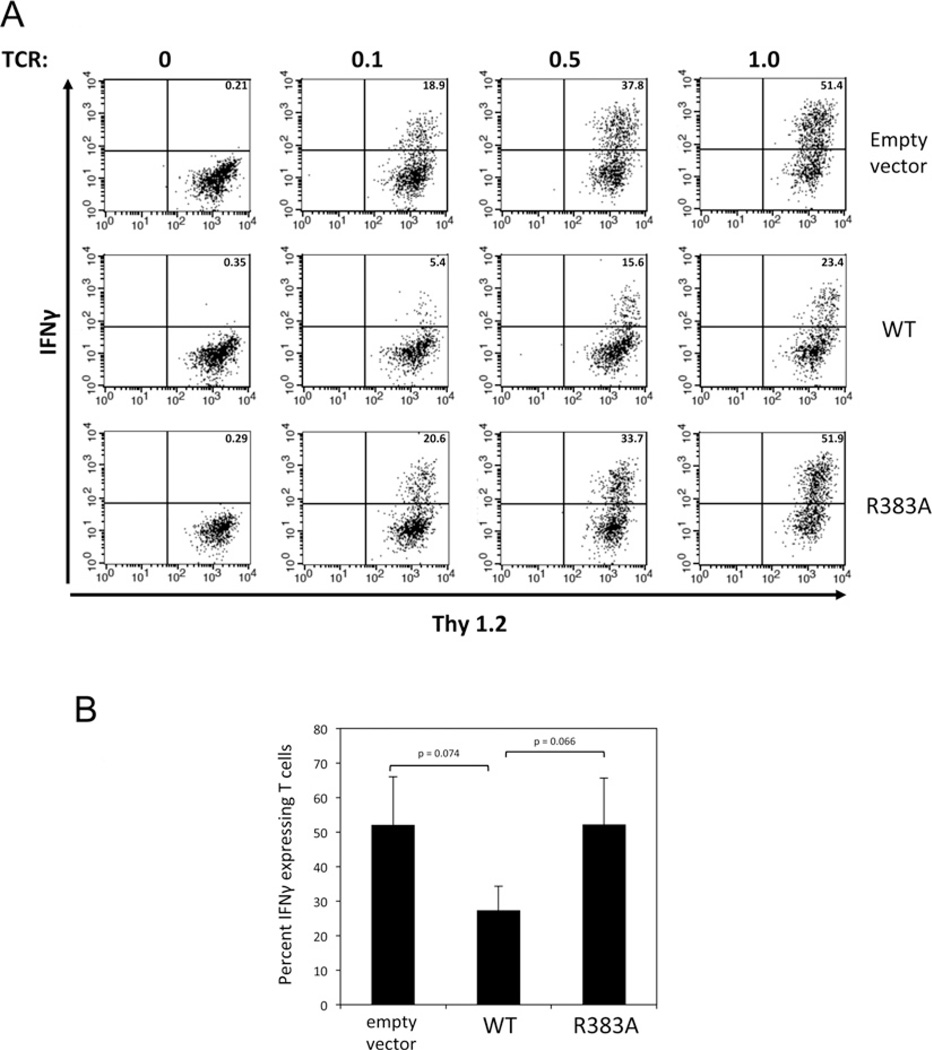

Having established a critical role for Arg383 in Sts-1 in vitro phosphatase activity we then addressed the requirement for Arg383 in Sts-1 signalling functions. Within T-cells the Sts proteins negatively regulate proximal signalling pathways downstream of the TCR [15]. To assess the functional importance of Sts-1 Arg383 in inhibiting TCR signalling, we employed two functional assays. First, we utilized an NFAT-responsive luciferase reporter assay. NFAT is a transcription factor whose level of activation following TCR engagement is critically and directly dependent on the overall strength of activation of signalling pathways downstream of the TCR [32]. Overexpression of wild-type Sts-1 in T-cells leads to a reduced NFAT response following TCR stimulation. In contrast, overexpression of Sts-1 R383A failed to inhibit levels of NFAT activation (Figure 5), suggesting an important role for Arg383 in Sts-1 signalling functions. To assess further the role of Arg383, we employed a T-cell reconstitution assay in which Sts-1 is introduced into primary T-cells derived from Sts-1/2−/− mice. T-cells that lack the Sts proteins hyper-proliferate in response to T-cell stimulation and secrete excessive levels of cytokines, including IFNγ [15]. Reconstitution of mutant T-cells with wild-type Sts-1 suppresses the hyper-responsive phenotype [21]. Therefore the ability of wild-type and Sts-1 R383A to down-regulate IFNγ production was compared. Both proteins were expressed at similar levels in mutant T-cells (Supplementary Figure S3 at http://www.biochemj.org/bj/453/bj4530027add.htm). However, unlike wild-type Sts-1, Sts-1 R383A failed to efficiently suppress IFNγ production (Figure 6). The inability of Sts-1 R383A to suppress IFNγ production by the same amount as wild-type Sts-1 was evident over a wide range of stimulatory antibody concentrations (Figure 6A). These results confirm that the HP activity associated with the C-terminal catalytic domain of Sts-1 plays an essential role in Sts-1 function, and suggest the phosphatase activity of the Sts-1 phosphatase domain requires Arg383 to interact and hydrolyse its in vivo substrate(s).

Figure 5. Requirement for Sts-1 Arg383 in the regulation of TCR signalling pathways.

Sts-1 R383A displays impaired regulation of TCR-induced NFAT activation. Jurkat cells were transfected with a firefly luciferase reporter construct under the control of NFAT binding sequences, a Renilla luciferase reporter construct under a constitutive promoter and plasmids encoding wild-type Sts-1 (WT) or the mutants R379A, R383A and R462A. The cells were then stimulated by placing on anti-TCR-coated plates. The histogram presents luciferase activity relative to TCR-stimulated empty-vector transfections. The illustrated results are combined from three separate experiments, each with three replicates. Error bars are S.D. from the three independent experiments. The P value comparing the wild-type and R383A is illustrated with the P values between the wild-type and other conditions being less than 0.05. IP, immunoprecipitation; RLU, relative luciferase units.

Figure 6. Requirement for Sts-1 Arg383 in the regulation of IFNγ expression in primary T-cells.

Primary T-cells were infected with retrovirus expressing empty vector, wild-type Sts-1 (WT) or Sts-1 R383A. Following stimulation with the indicated concentrations of anti-TCR stimulatory antibody, reconstituted T-cells were stained with fluorochrome-labelled antibodies to Thy1.2 (T-cell marker) and IFNγ to assess the levels of IFNγ expression. Cells were analysed by flow cytometry. Cytokine-expressing T-cells are visible in the upper right-hand quadrant with the percentage of cells indicated. Illustrated are representative data (A) for the average of three independent experiments ± S.D. (B) with 1 µg/ml stimulation. The P values between relevant datasets are indicated.

DISCUSSION

The Sts proteins belong to the superfamily of HPs by virtue of a C-terminal catalytic domain. All HPs possess an evolutionarily conserved quartet of two arginine and two histidine residues that are required for catalytic activity, and the Sts proteins are no exception [20]. Arg379, His380, Arg462 and His565 of Sts-1 adopt a signature conformation within the active site, with His380 being the nucleophile. Mutation of any of these residues yields an inactive or severely impaired enzyme [21]. To date, there have been few attempts to characterize additional residues that are important for HP catalytic activity. However, in the present study we identify and characterize an additional arginine residue that plays a critical role in Sts phosphatase activity. Located at position 383 in Sts-1, the arginine residue clusters together with Arg379 and Arg462 in the active site of Sts-1. The results of the present study demonstrate that Sts-1 Arg383 is required for both the in vitro catalytic activity toward model substrates and intracellular catalytic activity. In addition, we demonstrate that Arg383 is essential for Sts-1 to function as a negative regulator of TCR signalling pathways.

Sts-1 Arg383 is noteworthy for several reasons. First, it is conserved in all Sts orthologues. Indeed, the corresponding residue of Sts-2 (Arg369) is also required for Sts-2 activity (Figure 2D). Secondly, Sts-1 Arg383 closely neighbours the nucleophilic histidine residue and its side chain projects prominently into the cavity that defines the active site. Structural data indicate that it could make hydrogen bonds directly with the phosphate moiety of the incoming substrate, as do the two other active-site arginine residues, Arg379 and Arg462 (Figure 1B) [21,27,33]. As the two latter residues are thought to stabilize the interaction between the enzyme and substrate, Sts-1 Arg383 could likewise support the formation of an enzyme–substrate complex. However, we also cannot discount the hypothesis that it stabilizes an enzyme–phosphate-leaving group structure. Alternatively, because Sts-2 Arg369 has been shown to be involved directly in the interaction between phosphorylated His366 and a vanadate moiety, in a complex that mimics the transition state structure for phospho-transfer reactions [33], Arg383 could facilitate the formation of a transition state structure by neutralizing build-up of negative charges on the substrate. These roles are also consistent with our biochemical data. Interestingly, a homologous arginine residue within an AcP has also been proposed to function within the second step of the proposed HP catalytic reaction. Namely, Arg62 of Aspergillus phytase has been hypothesized to be involved in guiding the release of inorganic phosphate from the active site following substrate hydrolysis [34]. In addition to interacting with the incoming phosphorylated substrate or phosphate-leaving product, Sts Arg383/369 also likely forms ionic interactions and/or hydrogen bonds with neighbouring side chains or backbone atoms, thereby helping to maintain the requisite conformation of the active-site residues. Indeed, structural data indicate an interaction via hydrogen bonding between Arg383/369 and Asp385/371 (see Figure 1B). Finally, structural data also indicate hydrogen-bond interactions between Arg383 and active site water molecules. Thus Sts-1 Arg383 probably contributes to the myriad of ionic interactions that occur within the active site while also being directly involved in the Sts-1 catalytic reaction.

By clustering together with Arg379/365 and Arg462/448 to form a trio of tight-knit arginine residues that together form a ring around His380/366, Arg383/369 contributes to the remarkably electropositive nature of the Sts active site. We surmise that its presence is intimately connected with both the nature of Sts substrates and the manner in which the Sts proteins interact with their substrates. Currently, there is circumstantial evidence that they may target tyrosine kinases, such as Zap-70 and Syk (spleen tyrosine kinase), that participate in signalling pathways downstream of antigen receptors [21,35,36]. However, the bona fide Sts in vivo substrates have not been established definitively. Undoubtedly, definitive identification will probably enhance our understanding of Arg383/369 function in the context of the Sts catalytic reaction.

Curiously, an arginine residue corresponding to Sts Arg383/369 is conserved within the AcP branch of the HPs, but is absent within the vast majority of Branch 1 enzymes [20,24]. This dichotomy suggests that there might be significant underlying differences between the reactions catalysed by the two individual sub-branches, despite the presence of the same core catalytic residues in each sub-branch. This notion is strengthened by the observation that Branch 1 enzymes rely on a conserved glutamate residue to serve as a general acid during the catalytic reaction, whereas in AcP enzymes a conserved aspartate that is positioned entirely differently is thought to fulfil the same function [20,24]. Interestingly, the Sts proteins possess both the invariant glutamate residue found in all Branch 1 enzymes and the extra active site arginine that uniquely characterizes all Branch 2 enzymes. To our knowledge, the only other Branch 1 enzymes that possess an Arg383/369 equivalent are found in various species of cyanobacteria (both filamentous and unicellular), some plant fungi and an anaerobic parasitic protozoan (Entamoeba histolytica) (see Supplementary Figure S4). It is currently unclear why both the Sts phosphatases and a number of putative enzymes found in evolutionarily ancient organisms simultaneously possess two features which otherwise individually help define the separate and unique branches of the HPs. It is probable that further investigation into the underlying requirement for Arg383/369 in Sts enzyme activity and intracellular function could reveal the answer to this question. In turn, it could also yield insights into the mechanism by which the Sts proteins regulate the threshold of activation of T lymphocytes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Laurie Levine for assistance with animal care and both Todd Rueb and Rebecca Connor in the Stony Brook University Flow Cytometry Facility for assistance with cell sorting. We also thank Jorge Benach for unfailing support, and Professor Nancy Reich and Professor Michael Hayman for helpful discussions.

FUNDING

This work was supported by Stony Brook University, the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute [grant number CA115611-01 (to N.N.)], the Arthritis Foundation [grant number LI07 (to N.C.)] and the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease [grant numbers R21AI075176 and R01AI080892 (to N.C.)].

Abbreviations used

- AcP

acid phosphatase

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- HP

histidine phosphatase

- IFNγ

interferon γ

- IL-2

interleukin 2

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T-cells

- OMFP

3-O-methylfluorescein phosphate

- PGM

phosphoglycerate mutase

- pNPP

p-nitrophenyl phosphate

- Sts

suppressor of T-cell receptor signalling

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- Zap-70

ζ-associated protein of 70 kDa

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Boris San Luis and Nick Carpino performed the experiments, Nicolas Nassar provided purified proteins for the enzyme assays and contributed to paper preparation, and Nick Carpino wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nossal GJ. Current concepts: immunology. The basic components of the immune system. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987;316:1320–1325. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198705213162107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam R, Gorska M. Lymphocytes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003;111:S476–S485. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohashi PS, DeFranco AL. Making and breaking tolerance. Current Opin. Immunol. 2002;14:744–759. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller DL. Mechanisms maintaining peripheral tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:21–27. doi: 10.1038/ni.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh RP, Waldron RT, Hahn BH. Genes, tolerance and systemic autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 2012;11:664–669. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith-Garvin JE, Koretzky GA, Jordan MS. T cell activation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009;27:591–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nurieva RI, Liu X, Dong C. Molecular mechanisms of T-cell tolerance. Immunol. Rev. 2011;241:133–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01012.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris GP, Allen PM. How the TCR balances sensitivity and specificity for the recognition of self and pathogens. Nat. Immunol. 2012;19:121–128. doi: 10.1038/ni.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mustelin T, Tasken K. Positive and negative regulation of T-cell activation through kinases and phosphatases. Biochem. J. 2003;371:15–27. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saito T, Yamasaki S. Negative feedback of T cell activation through inhibitory adapters and costimulatory receptors. Immunol. Rev. 2003;192:143–160. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jang IK, Gu H. Negative regulation of TCR signaling and T-cell activation by selective protein degradation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2003;15:315–320. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilkinson B, Downey JS, Rudd CE. T-cell signaling and immune system disorders. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2005;7:1–29. doi: 10.1017/S1462399405010264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohashi PS. T-cell signaling and autoimmunity: molecular mechanisms of disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:427–438. doi: 10.1038/nri822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsygankov AY. TULA-family proteins: a new class of cellular regulators. J. Cell. Physiol. 2013;228:43–49. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpino N, Turner S, Mekala D, Takahashi Y, Zang H, Geiger TL, Doherty P, Ihle JN. Regulation of Zap-70 activation and TCR signaling by two related proteins, Sts-1 and Sts-2. Immunity. 2004;20:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00351-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Concannon P, Onengut-Gumuscu S, Todd JA, Smyth DJ, Pociot F, Bergholdt R, Akolkar B, Erlich HA, Hilner JE, Julier C, et al. A human Type 1 diabetes susceptibility locus maps to chromosome 21q22.3. Diabetes. 2008;57:2858–2861. doi: 10.2337/db08-0753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhernakova A, Stahl EA, Trunka G, Raychaudhuri S, Festen EA, Franke L, Westra HJ, Fehrmann RS, Kurreeman FA, Thomson B, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in celiac disease and rheumatoid arthritis identifies fourteen non-HLA shared loci. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fei Y, Webb R, Cobb BL, Direskeneli H, Saruhan-Direskeneli G, Sawalha AH. Identification of novel genetic susceptibility loci for Behcet’s disease using a genome-wide association study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009;11:R66. doi: 10.1186/ar2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin Y, Birlea SA, Fain PR, Gowan K, Riccardi SL, Holland PJ, Mailloux CM, Sufit AJ, Hutton SM, Amad-Myers A, et al. Variant of TYR and autoimmunity susceptibility loci in generalized vitiligo. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:1686–1697. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rigden DJ. The histidine phosphatase superfamily: structure and function. Biochem. J. 2008;409:333–348. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikhailik A, Ford B, Keller J, Chen Y, Nassar N, Carpino N. A phosphatase activity of Sts-1 contributes to the suppression of TCR signaling. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:486–497. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.San Luis B, Sondgeroth B, Nassar N, Carpino N. Sts-2 is a phosphatase that negatively regulates Zeta-associated protein (Zap)-70 and T cell receptor signaling pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:15943–15954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.177634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsygankov AY. TULA-family proteins: an odd couple. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009;66:2949–2952. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0071-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jedrzejas MJ. Structure, function, and evolution of phosphoglycerate mutases: comparison with fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase, acid phosphatase, and alkaline phosphatase. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2000;73:263–287. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(00)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bond CS, White MF, Hunter WN. High resolution structure of the phosphohistidine-activated form of Escherichia coli cofactor-dependent phosphoglycerate mutase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:3247–3253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bond CS, White MF, Hunter WN. Mechanistic implications for Eschericia coli cofactor-dependent phosphoglycerate mutase based on high-resolution crystal structure of a vanadate complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;316:1071–1081. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Jakoncic J, Carpino N, Nassar N. Structural and functional characterization of the 2H-phosphatase domain of Sts-2 reveals an acid-dependent phosphatase activity. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1681–1690. doi: 10.1021/bi802219n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider G, Lindqvist Y, Vihko P. Three dimensional structure of rat acid phosphatase. EMBO J. 1993;12:2609–2615. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05921.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kostrewa D, Gruninger-Leitch F, D’Arcy A, Broger C, Mitchell D, van Loon APGM. Crystal structure of phytase from Aspergillus ficuum at 2.5 Å resolution. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1997;4:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nsb0397-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasemann CA, Istvan ES, Uyeda K, Deisenhofer J. The crystal structural of the bifunctional enzyme 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase reveals distinct domain homologies. Structure. 1996;15:1017–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brdicka T, Kadlecek TA, Roose JP, Pastuszak AW, Weiss A. Intramolecular regulatory switch in Zap-70: analogy with receptor tyrosine kinases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:4924–4933. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.4924-4933.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macian F. NFAT proteins: key regulators of T-cell development and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005;5:472–484. doi: 10.1038/nri1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Y, Jakoncic J, Parker K, Carpino N, Nassar N. Structures of the phosphorylated and VO3-bound 2H-phosphatase domain of Sts-2. Biochemistry. 2009;48:8129–8135. doi: 10.1021/bi9008648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Q, Huang Q, Lei XG, Hao Q. Crystallographic snapshots of Aspergillus fumigatus phytase, revealing its enzymatic dynamics. Structure. 2004;12:1575–1583. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen X, Ren L, Carpino N, Daniel JL, Kunapuli SP, Tsygankov AY, Pei D. Determination of the substrate specificity of protein-tyrosine phosphatase TULA-2 and identification of Syk as a TULA-2 substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:31268–31276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.114181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomas DH, Getz TM, Newman TN, Dangelmaier CA, Carpino N, Kunapuli SP, Tsygankov AY, Daniel JL. A novel histidine tyrosine phosphatase, TULA-2, associates with Syk and negatively regulates GPVI signaling in platelets. Blood. 2010;116:2570–2578. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-268136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.