Abstract

The heme in cytochromes c undergoes a conserved out-of-plane distortion known as ruffling. For cytochromes c from the bacteria Hydrogenobacter thermophilus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, NMR and EPR spectra have been shown to be sensitive to the extent of heme ruffling and to provide insights into the effect of ruffling on electronic structure. Using mutants of each of these cytochromes that differ in the amount of heme ruffling, NMR characterization of the low-spin (S=1/2) ferric proteins has confirmed and refined the developing understanding of how ruffling influences spin distribution on heme. The chemical shifts of the core heme carbons were obtained through site-specific labeling of the heme via biosynthetic incorporation of 13C-labeled 5-aminolevulinic acid derivatives. Analysis of the contact shifts of these core heme carbons allowed Fermi contact spin densities to be estimated, and changes upon ruffling to be evaluated. The results allow a deconvolution of contributions to heme hyperfine shifts and a test of the influence of heme ruffling on electronic structure and hyperfine shifts. The data indicate that as heme ruffling increases, the spin densities on the β-pyrrole carbons decrease, while the spin densities on the α-pyrrole carbons and meso carbons increase. Furthermore, increased ruffling is associated with stronger bonding to the heme axial His ligand.

Structural characterization of heme proteins has demonstrated that hemes undergo non-planar distortions1 along low-frequency vibrational normal modes that are classified by the symmetry of the normal mode.2 Saddling (B2u), ruffling (B1u), and doming (A2u) are the most frequently observed non-planar distortions in heme proteins, and the type of structural distortion typically is conserved among proteins that carry out the same function.1,3 For example, saddling is conserved in peroxidases,4 ruffling is seen in electron-transferring c-type cytochromes,5,6 and doming is observed in oxygen storage and transport proteins such as myoglobin and hemoglobin.3,7 The functional role of heme non-planar distortions in proteins is not yet fully understood, and has been the subject of recent discussion and research.1,8

Ruffling has been proposed to influence heme function in a number of proteins. In electron-transferring cytochromes c and in NO-carrying nitrophorins, ruffling has been shown to modulate reduction potential.5,9–11 Ruffling also has been suggested to lower affinity for oxygen in nitric oxide/oxygen binding (H-NOX) proteins11 and to influence the NO binding geometry in nitrophorins.10,12 In both nitrophorins and hydroxylamine oxidoreductase, a ruffled heme is proposed to increase the heme affinity for NO.10,13 Ruffling also has been shown to modify heme electronic properties to facilitate enzymatic heme degradation by the enzymes heme oxygenase,14 IsdI,15 and MhuD.16,17 In addition, ruffling is proposed to modulate electronic coupling in a catalytic intermediate of nitrophorin 2, which has been discovered to have peroxidase functionality.18 The heme in some cyano-protoglobins has been found to be highly ruffled, accounting for electronic structure differences with cyano-metmyoglobin.19 The means by which heme ruffling modifies electronic structure to influence function is not yet fully understood. Besides leading to a better understanding of structure-function relationships in heme proteins, understanding the impact of ruffling on metalloporphyrin properties is expected to enhance the development of metalloporphyrin-based catalysts.20–24

Most characterizations of heme conformation have relied on normal-coordinate structural decomposition (NSD) analysis of X-ray crystal structures, yielding the net out-of-plane displacement of porphyrin atoms along each distortion coordinate (i.e. ruffling, saddling, doming),2 but recent efforts have focused on developing methods that reveal effects of heme conformation on electronic structure and function. For example, vibrational spectroscopic methods have been utilized to characterize heme out-of-plane distortions such as ruffling. Approaches include the use of resonance Raman marker frequencies,25 Raman dispersion spectroscopy,26 and femtosecond coherence spectroscopy.27 Magnetic spectroscopic methods such as EPR and NMR are well suited to probe the interplay between heme geometric and electronic structure in paramagnetic heme proteins.28–33 Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) has provided insight into the influence of ruffling on d-orbital energies,34 and heme methyl 1H shifts have been found to be sensitive to heme ruffling.35,36 A recent study used NMR spectroscopy and DFT calculations to investigate the effects of ruffling on heme electronic structure and proposed a mechanism for how ruffling affects heme redox properties.5 Heme core 13C NMR shifts have been used to determine the heme iron oxidation and spin state,37 and are being developed as probes of heme electronic structure.5,38 For heme model complexes, 13C shifts have been used to calculate the distribution of spin density on the porphyrin ring.39 The spin densities determined from NMR provide a means by which to test molecular orbital models of heme electronic structure. Heme core 13C shifts, however, have not yet been fully developed as probes of heme distortion. A goal of the work reported herein is to compare the use of 13C and 1H shifts of heme as probes of heme ruffling.

Cytochrome c has served as an ideal model for testing the influence of ruffling on heme properties.5,6,34,40 The heme in cytochromes c tends to be highly ruffled, with little contribution from other types of out-of-plane distortions.41 Additionally, the degree of ruffling can be modulated by site-directed mutagenesis without significantly disrupting the heme orientation within the protein structure,5,34 because the heme is covalently attached to the protein. Cytochromes c also tend to have a fixed axial histidine orientation,8 simplifying the interpretation of spectroscopic data.28 The present work aims to measure the influence of ruffling on heme electronic structure in cytochromes c by analyzing 1H and 13C hyperfine NMR shifts. In this study, we compare heme 13C and 1H chemical shifts between wild-type and mutant cytochromes c, making use of mutants with established changes in ruffling relative to wild-type. One wild-type/mutant pair is Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytochrome c551 (Pa WT) and its point mutant with a more ruffled heme, Pa F7A. The ruffling of the Pa WT and Pa F7A hemes was previously characterized by X-ray crystallography, which shows that the F7A mutation nearly doubles the extent of ruffling, measured as the total out-of-plane displacement of heme atoms along the ruffling coordinate,2 without significantly changing other out-of-plane deformations.5,42,43 To include additional data points and evaluate another cytochrome c, we also measure and analyze heme 1H and 13C chemical shifts for a series of Hydrogenobacter thermophilus cytochrome c552 variants, Ht M13V, Ht K22M, and Ht M13V/K22M, as well as wild-type (Ht WT). These mutations were previously determined by EPR to increase heme ruffling.34 In addition to the heme resonances, we also include analysis of the His axial ligand chemical shifts. In the present study, the NMR hyperfine shifts are divided into contact and pseudocontact components using a simple model, allowing Fermi contact spin densities to be estimated. The results demonstrate how ruffling influences spin density delocalization on the porphyrin and provide an illustration of the influence of ruffling on heme axial ligands. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the chemical shifts that are the most convenient to measure, the heme methyl 1H shifts, provide the best NMR measure of the extent of ruffling.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

The plasmid pSCH552 containing the gene for cytochrome c552 from Hydrogenobacter thermophilus has previously been described44 along with the mutants Ht M13V, Ht K22M, and Ht M13V/K22M.45 The plasmid pETPA containing the gene to express Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytochrome c551 has also been previously described46 along with the Pa F7A variant.34 Each of the cytochrome c genes were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)star cells (Invitrogen) with the pEC86 plasmid containing the ccmABCDEFGH operon.47 Growth in Luria Bertani (LB) medium provided natural abundance-isotope samples. Carbon-13 isotope enrichment of the core heme carbons was accomplished by expressing protein in minimal medium supplemented with isotope-labeled 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), which is a biological precursor to heme.48 Uniform 15N labeling was accomplished by expression in minimal medium with (15NH4)2SO4 (Sigma-Aldrich) as the sole nitrogen source. The minimal medium recipe used is reported elsewhere.5 The 4-13C and 5-13C isotopically-labeled ALA derivatives were synthesized according to literature methods.49 Ht cytochromes c44 and Pa cytochromes c46 were purified as previously described. Concentrations were determined using extinction coefficients of ε409.5 = 105 mM−1 cm−1 for ferric Ht cytochromes44 and of ε409 = 106.5 mM−1 cm−1 for ferric Pa cytochromes.46,50

NMR spectroscopy

Oxidized (FeIII) protein samples were obtained from purified protein exchanged into 50 mM NaPi buffer at pH 7.0, after which 10% D2O and a 5-fold molar excess of K3Fe(CN)6 (Sigma Aldrich) relative to protein were added. Reduced (FeII) samples were prepared by exchanging purified protein into 50 mM NaPi at pH 7.0, followed by lyophilization. The lyophilized sample was dissolved in 100% D2O or 90% H2O/10% D2O under an argon atmosphere. A 10- to 20-fold excess of Na2S2O4 (Sigma) was then added to reduce the sample, which was transferred to an NMR tube under a nitrogen atmosphere. Mixed oxidation state samples were prepared by partially oxidizing previously reduced samples by brief exposure to air. Final protein concentrations were 1–3 mM.

A 500-MHz Varian Inova spectrometer fitted with a triple-resonance probe was used for all NMR experiments. One-dimensional 1H NMR spectra were recorded using presaturation of the water signal with a saturation delay of 1 s. 1H-13C heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence (HMQC) spectra used to observe the heme methyl resonances were obtained with natural isotope abundance samples using a presaturation delay of 190 ms and a JCH value of 200 Hz. 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra of ferric protein samples were obtained with uniformly 15N-labeled protein samples using a JNH value of 135 Hz; this high JNH value enhances the detection of faster relaxing nuclei.45 A JNH of 94 Hz was used for 1H-15N HSQC spectra of ferrous samples. 2-D TOCSY spectra were collected using a spin-lock time of 90 ms, and 2-D NOESY spectra were collected using a mixing time of 100 ms. A 3-D HSQC-TOCSY spectrum was collected with uniformly 15N-labeled ferrous Ht WT with a spin-lock time of 90 ms and a JNH value of 94 Hz. Two-dimensional exchange spectroscopy (EXSY) was performed with a mixing time of 100 ms on mixed oxidation state samples. 1-D 13C experiments with 1H-decoupling were run on samples with core heme carbon isotope enrichment via labeling with 4-13C ALA or 5-13C ALA. For 1-D 13C experiments on FeIII and FeII samples, recycle times of 120 ms and 2.3 seconds, respectively, were used. Data on Pa WT and Pa F7A were collected at 25 °C to facilitate comparison to published data on these and related proteins. However, data on Ht WT and its variants were collected at 40 °C because significant linebroadening was observed for 13C resonances for this protein at 25 °C, likely as a result of the fluxionality of the axial Met. All spectra were referenced to 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid (DSS) indirectly through the water resonance. One-dimensional spectra were processed with SpinWorks 3.1 beta using a 20 Hz or 30 Hz line-broadening window function for 13C and 1H spectra, respectively. After phasing, peaks were fit to Lorentzian functions using the multi-peak fitting package in Igor Pro 6.12. For two-dimensional HMQC spectra, processing was performed with NMRPipe51 using a previously published macro.5

Calculation of the metal-centered pseudocontact shifts for Pa WT and Pa F7A relied on previously determined magnetic axes and anisotropic susceptibility of Pa WT.32 Magnetic susceptibility values used are in Table S1. Hydrogen atoms were added to each crystal structure using MolProbity.52 The crystal structures were then oriented such that the four pyrrole nitrogens of the heme are in the x-y plane, the +z axis points toward the axial methionine, and the iron is at the origin. The molecule was then rotated such that the heme pyrrole II nitrogen was along the +x axis. The metal-centered pseudocontact shifts were then calculated according to literature procedures.53 The orientation and anisotropy of the paramagnetic susceptibility tensor of Ht WT at 40 °C (pH 7.0) were determined herein from measured pseudocontact shifts. Chemical shift assignments for ferric Ht WT at 40 °C (pH 7.0) were made using TOCSY and NOESY spectra and by comparison to previous assignments at 25 °C (pH 5).32 Assignments of ferrous Ht WT at 40 °C (pH 7.0) were made using TOCSY, NOESY, and 3-D HSQC-TOCSY spectra and by comparison to previous assignments both at 25 °C (pH 5)32 and at 23 °C (pH 6).54 Pseudocontact shifts were determined by taking the difference between the shift in the oxidized and reduced states, using nuclei for which contact shift is negligible (i.e., excluding the heme, Cys12, Cys15, His16, and Met61). A total of 51 pseudocontact shifts were used in the fitting along with the resonance assignments in both oxidation states (Table S4). The magnetic axes determination used chain A of the 2.0 Å crystal structure of reduced Ht WT (PDB: 1YNR).55 Proton coordinates were added using MolProbity,52 and the positions of the methyl protons were averaged over one rotation. The coordinate axes were defined as described above for Pa WT and Pa F7A. The fitting used methods and an in-house program previously described.32 After determination of the magnetic axes orientation and magnetic anisotropies for Ht WT, pseudocontact shifts of the heme and axial ligand nuclei were calculated as described above for Pa WT and Pa F7A.

Results and Analysis

NMR assignments

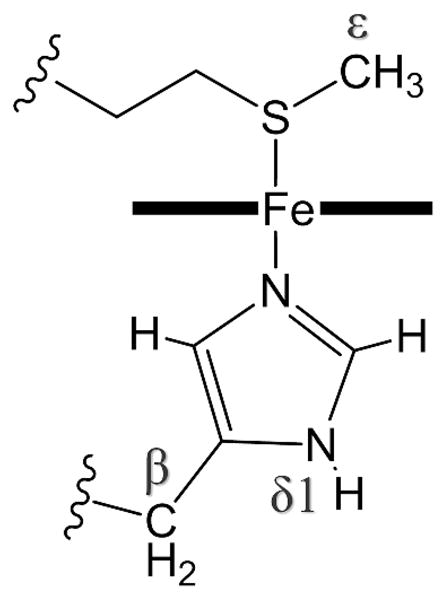

Heme nuclei

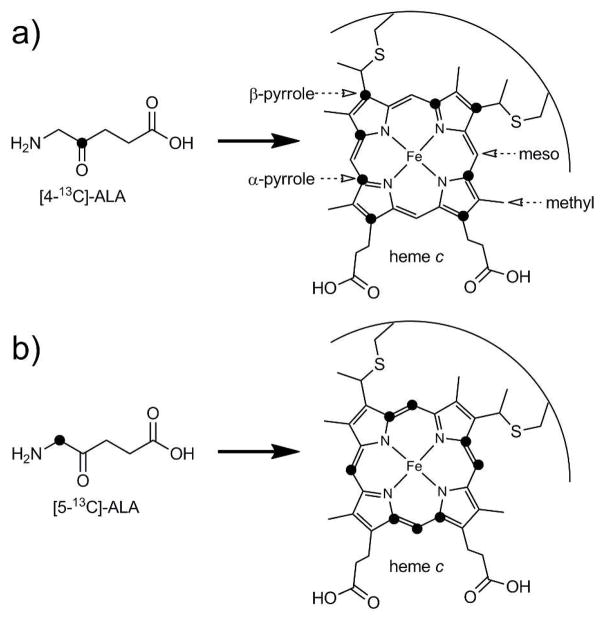

Heme 1H and 13C NMR assignments were made for ferric Pa WT, Pa F7A, Ht WT, Ht M13V, Ht K22M, and Ht M13V/K22M and are found in Tables 1 (Pa variants) and 2 (Ht variants). Heme and selected axial ligand 1H and 13C assignments made for reduced (diamagnetic) Pa WT are shown in Table S2. The heme assignments reported for reduced Pa WT were used as reference diamagnetic shifts throughout. The shifts of the four heme methyl substituents (Figure 1a) for all proteins were obtained via 1-D 1H and 2-D 1H-13C HMQC spectra using samples at natural isotope abundance. In the oxidized proteins, the methyl resonances were identified in the 1-D 1H spectra as the most deshielded signals that integrated to three protons (Figures S1 and S2), consistent with published assignments.56 The methyl 13C shifts were then obtained from cross-peaks in the 1H-13C HMQC spectra and were consistent with published assignments.57 An overlay of HMQC spectra of the Ht series of variants is shown in Figure S3, and an overlay of Pa WT and Pa F7A is shown in Figure S4. The meso 1H and 13C shifts were detected in 1H-13C HMQC spectra as well, using the isotope labeling pattern provided by 5-13C-ALA enrichment (Figure 1b). With this labeling pattern, the four meso carbons are 13C-labeled as well as four of the α-pyrrole carbons. Since the meso carbons are the only isotopically enriched carbons with attached protons, these are the strongest signals in the HMQC spectra. HMQC spectra of 5-13C-ALA-enriched samples are included in Supporting Information (Figures S5 through S7).

Table 1.

Chemical shifts (ppm) for oxidized Pa WT and Pa F7Aa

| Pa WT | Pa F7A | (Pa F7A - Pa WT) | (Ht A7F - Ht WT)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H methyl | 22.10 | 21.35 | −0.75 | +0.17 |

| 13C methyl | −41.0 | −39.8 | +1.2 | −0.9 |

| 1H meso | 2.64 | 2.58 | −0.05 | −0.13 |

| 13C meso | 37.0 | 38.2 | +1.2 | −0.5 |

| α-pyrrole 13C | 29.4 | 29.3 | −0.1 | −4.9d |

| β-pyrrole 13Cc | 141.7 | 140.5 | −1.2 | n.d.e |

| Met61 ε-C1H3 | −16.91 | −16.96 | −0.05 | −1.21 |

| His16 δ1-15N | 169.3 | 165.3 | −4.0 | n.d.e |

| His16 δ1-N1H | 11.9 | 10.6 | −1.30 | n.d.e |

Data at 25 °C. Average chemical shifts are reported for heme nuclei.

Published data at 51 °C.5

Four out of the eight β-pyrrole 13C shifts were averaged, according to the 4-13C-ALA labeling scheme (Figure 1a).

Data for four out of the eight α-pyrrole 13C shifts, according to the 5-13C-ALA labeling scheme (Figure 1b).

Not determined.

Figure 1.

13C isotope labeling pattern obtained from the addition of 4-13C-ALA (a) and 5-13C ALA (b). Heme nuclei are labeled in (a).

The α-pyrrole and β-pyrrole 13C shifts were detectable only with 1-D 13C NMR. The four α-pyrrole carbons labeled with 5-13C ALA were identified in 1-D spectra by eliminating the meso 13C shifts assigned from the HMQC spectra. For Pa WT and Pa F7A, this assignment strategy was followed for both the FeIII and FeII redox states (Figures S8–S12), with the exception that the reduced heme methyl 1H shifts were obtained for Pa WT and Pa F7A by correlation crosspeaks observed in 2-D EXSY spectra of mixed oxidation state samples (Figure S13). Heme chemical shifts for reduced Pa WT are found in Table S2.

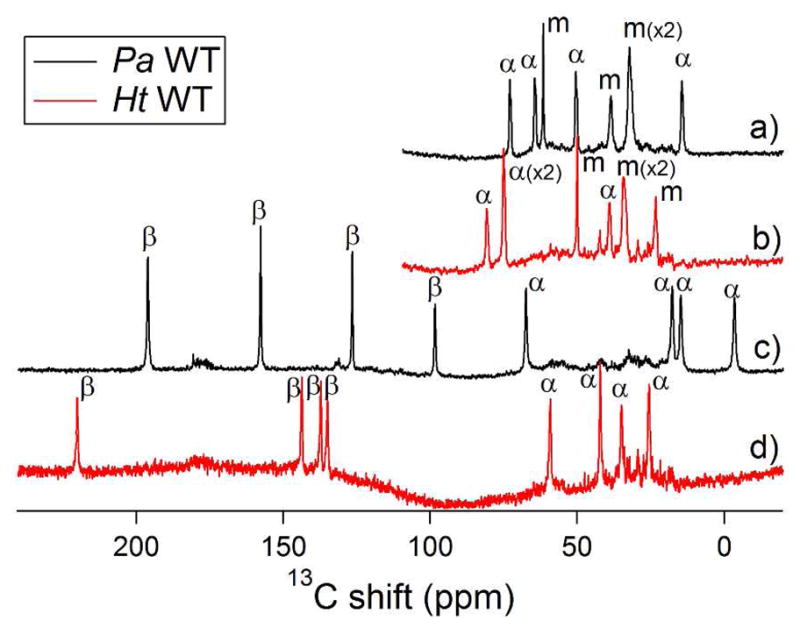

Labeling of samples with 4-13C ALA yielded heme with four α-pyrrole and β-pyrrole carbons enriched with 13C (Figure 1a). Distinguishing the α-pyrrole from the β-pyrrole resonances was made possible by the different labeling schemes and comparison to established chemical shift ranges for these nuclei in low-spin ferric heme.38 A 1-D 13C spectrum of the 4-13C ALA-enriched sample of Ht WT (Figure 2d) shows four peaks between 10 and 70 ppm. These peaks are in the same chemical shift range as the α-pyrrole signals observed in 1-D 13C spectrum of the 5-13C ALA-enriched Ht WT sample (Figure 2b), and were therefore assigned to α-pyrrole carbons. The remaining four peaks had chemical shifts larger than 120 ppm, and thus were assigned to β-pyrrole carbons. This pattern, where α-pyrrole 13C shifts are clustered with lower chemical shifts than the β-pyrrole 13C shifts, has been previously observed in low-spin FeIII heme proteins.38

Figure 2.

1-D 13C NMR spectra of ferric heme resonances of Pa WT (black traces) and of Ht WT (red traces): a) and b) are spectra of 5-13C-ALA labeled samples of Pa WT and Ht WT, respectively; c) and d) are spectra of 4-13C-ALA labeled samples of Pa WT and Ht WT, respectively.

For Pa WT and Pa F7A, this same general assignment strategy was employed to distinguish between the α-pyrrole and β-pyrrole signals of the 4-13C-ALA labeled samples (Figure S11). The four α-pyrrole 13C signals from the 5-13C-ALA labeled sample are between −5 and +75 ppm. For both Pa WT and Pa F7A, there are only four peaks from the 4-13C-ALA labeled samples that appear in this region; these were assigned to the α-pyrrole carbons. The remaining four signals, which have chemical shifts greater than 90 ppm, were then assigned to β-pyrrole carbons. Using this assignment strategy with Pa WT and Pa F7A leaves some doubt in differentiating between α- and β-pyrrole carbons in the 4-13C-ALA-labeled samples. In Pa WT, the chemical shift of the most shielded β-pyrrole is less than 25 ppm higher than the least shielded α-pyrrole carbon. This is in contrast with the more than 65-ppm separation found in the Ht variants. The decreased separation between α- and β-pyrrole carbon shifts in the Pa variants increases the likelihood of an overlap between their chemical shift ranges. For example, in the case of Pa WT, the peaks at 63.9 and 90.9 ppm (25 °C, Figure 2c) have a chance of being assigned incorrectly. To resolve this ambiguity, temperature dependences of the α- and β-pyrrole carbon shifts were measured for Pa WT and Pa F7A. Hyperfine shifts in cytochromes c do not typically exhibit standard Curie behavior due to the presence of a thermally-accessible excited state.33 As a consequence, Curie plots of hyperfine shift have y-intercepts that deviate from the diamagnetic shift values. Since the atypical Curie behavior is well understood for cytochromes c, an analysis of the temperature dependence assists in the assignment of the core heme carbons.

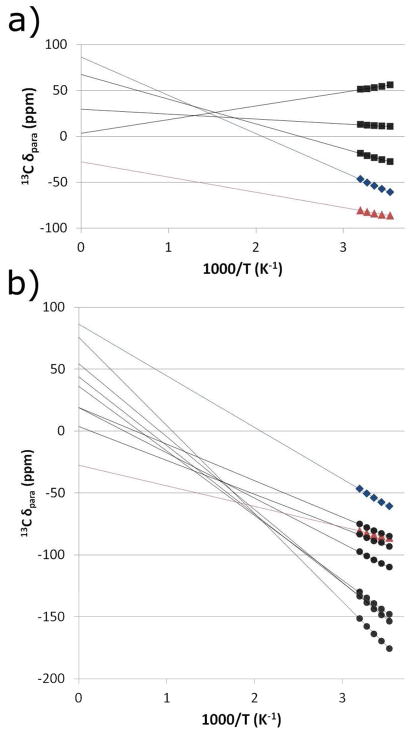

The temperature dependence of the α- and β-pyrrole carbon shifts of Pa WT is shown in Curie plots in Figure 3. The diamagnetic reference shifts were determined via 13C NMR of the 4-13C- and 5-13C-ALA labeled samples of Pa WT in the FeII redox state (Figure S12; Table S2). The average diamagnetic 13C shifts for the α-pyrroles and β-pyrroles were 147.7 ppm and 144.8 ppm, respectively. These values were subtracted from the observed chemical shifts to estimate the hyperfine shifts, which are plotted on the y-axis in Figure 3. A decrease in the magnitude of the hyperfine shift as temperature increases and a y-intercept of zero would thus be standard Curie behavior. As can be seen in Figure 3, the Pa WT peak at 90.9 ppm (25 °C) exhibits hyper-Curie behavior while the peak at 63.9 ppm exhibits hypo-Curie behavior. A pattern in the temperature dependence of cytochrome c methyl 1H and 13C shifts has been previously observed, where the more hyperfine-shifted peaks exhibit hyper-Curie behavior and the less-hyperfine shifted peaks exhibit hypo- or anti-Curie behavior.33 The reason for this behavior is a shift in the Boltzmann population of the low-lying excited state. It is expected that the temperature dependence of the β-pyrrole 13C shifts follow the same pattern as the heme methyl resonances because the paramagnetic shifts of the heme methyl resonances are mostly a result of the polarization of spin density from the β-pyrrole carbons. The temperature dependence of the resonances at 63.9 ppm and 90.9 ppm is consistent with this pattern only if they are assigned as α-pyrrole and β-pyrrole signals, respectively. The same temperature dependence study was used to clarify assignments of Pa F7A and is shown in Figure S14.

Figure 3.

(a) Temperature dependence of the three unambiguously assigned β-pyrrole 13C shifts for Pa WT (black squares) compared to the two peaks with ambiguous assignments (blue diamonds, red triangles). (b) Temperature dependence of the seven unambiguously assigned α-pyrrole 13C shifts for Pa WT (black circles) compared to the two peaks with ambiguous assignments (blue diamonds, red triangles). (a and b) The blue diamonds represent the peak tentatively assigned to a β-pyrrole carbon based on its lower shift and temperature dependence. The red triangles represent the peak tentatively assigned to an α-pyrrole carbon.

Axial ligands

Axial ligand assignments were made by comparison to previous assignments.58 The only significantly hyperfine-shifted resonance in the HSQC spectra of Pa WT and Pa F7A is that of the δ1-NH of the heme axial His16.45 An overlay of the HSQC spectra with the δ1-NH signals evident is shown in Figure S15. The axial methionine ε-CH3 peak can be observed in a 1H-1D spectrum as the only peak with a lower chemical shift lower than −10 ppm that integrates to three protons (Figures S1 and S2). Chemical shift assignments are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 2.

| WT | K22M | M13V | M13V/K22M | (M13V/K22M -WT)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H methyl | 21.65 | 21.53 | 20.91 | 20.59 | −1.06 |

| 13C methyl | −36.7 | −36.7 | −36.4 | −36.5 | +0.2 |

| 1H meso | 3.63 | 3.58 | 3.26 | 3.18 | −0.45 |

| 13C meso | 35.7 | 35.5 | 36.9 | 36.9 | +1.1 |

| α-pyrrole 13C | 53.9 | 54.1 | 44.8 | 41.9 | −12.0 |

| β-pyrrole 13Cd | 158.9 | 157.4 | 151.0 | 146.7 | −12.2 |

| Met61 ε-C1H3 | −15.27 | −15.09 | −17.69 | −18.26 | −2.99 |

| His16 δ1-15Ne | 182.3 | 181.3 | 170.5 | 167.1 | −15 |

| His16 δ1-N1He | 13.2 | 12.6 | 11.8 | 11.2 | −1.6 |

Average chemical shifts are reported for heme nuclei.

Temperature is 40 °C except where noted otherwise.

The change in chemical shift for the most ruffled Ht variant relative to Ht WT.

Four out of the eight β-pyrrole 13C shifts were averaged, according to the 4-13C-ALA labeling scheme (Figure 1a).

Measured at 25 °C, from Michel et al.45

Chemical shift changes with ruffling

Pa cytochrome c551 variants

The heme in Pa F7A has been shown by X-ray crystallography to be more ruffled than the heme in Pa WT.43 The heme 1H and 13C NMR shifts were recorded for both Pa WT and Pa F7A to learn the effect of ruffling on these shifts. In addition, the axial methionine ε-CH3 1H shift was measured along with the axial His δ1-15N and δ1-N1H shifts (Figure 4). Table 1 reports the chemical shifts for Pa F7A compared to Pa WT, and compares the chemical shift differences between Pa F7A and Pa WT to those between Ht A7F and Ht WT, which have previously been published.5 Use of average chemical shift values for each type of heme nucleus minimizes the effect of asymmetric spin density distributions that result from the axial ligand interactions with heme, and allows an analysis despite the lack of atom-specific assignments of heme core carbons.

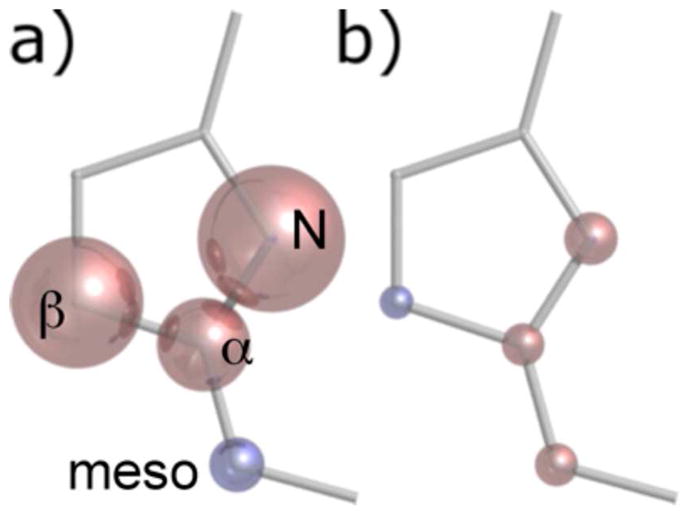

Figure 4.

Diagram of the axial ligands of cytochrome c showing labels for nuclei relevant to this work.

Heme chemical shifts of Pa F7A show a number of differences from Pa WT. In the more-ruffled Pa F7A, the magnitude of the average heme methyl 13C and 1H shifts decreases relative to Pa WT. Secondly, the average heme meso 13C shift increases while the average heme meso 1H shift decreases slightly. The average of the four measured β-pyrrole shifts decreases slightly, as does the average of all eight α-pyrrole shifts. These changes in average chemical shifts in Pa F7A relative to Pa WT are reported in Table 1. These changes are compared to previously published chemical shift changes observed for Ht A7F, a mutation that slightly decreases the extent of heme ruffling.5 The influence of heme ruffling is predicted to change the chemical shifts of Pa F7A relative to Pa WT in the opposite direction as that observed for Ht A7F relative to Ht WT in published work.5 As expected, the 1H methyl, 13C methyl, and 13C meso chemical shift changes in Pa F7A are in the opposite directions of those previously reported for Ht A7F. However, based on the Ht A7F results, while the average α-pyrrole shift was expected to increase with ruffling for Pa F7A, the average α-pyrrole shift slightly decreases. Likewise, the average 1H meso shift moved in the same direction in Pa F7A as in Ht A7F relative to the wild-type proteins. Finally, the axial ligand chemical shifts were compared between Pa WT and Pa F7A. As can be seen in Table 1, the axial methionine (Met61) ε-C1H3 resonance shifts to lower frequency in Pa F7A relative to Pa WT, but only slightly. On the proximal side of the heme, the axial His (His16) δ1-15N and δ1-N1H resonances shift to lower frequency in Pa F7A (Table 1).

Ht cytochrome c552 variants

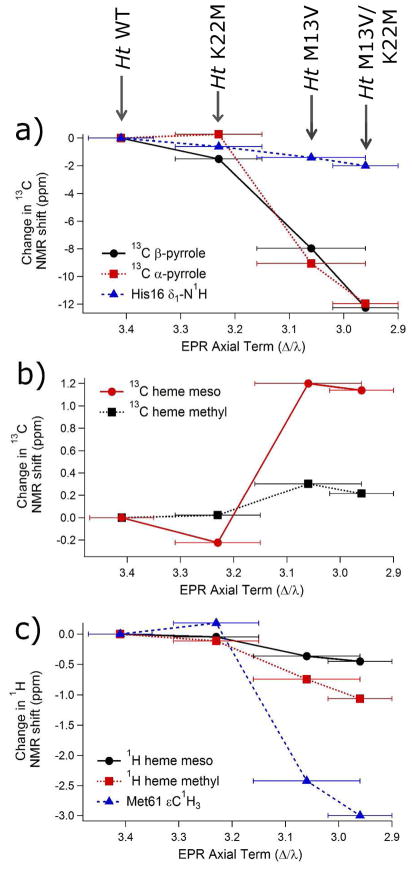

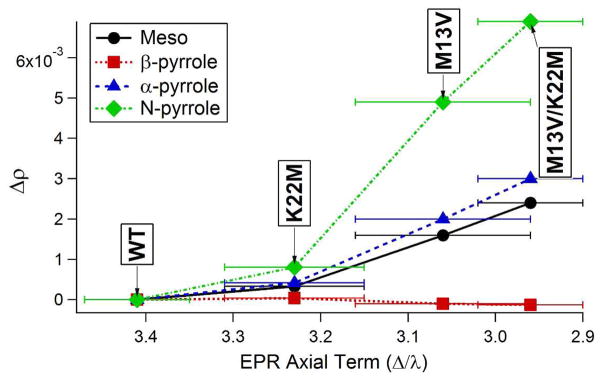

The series of Ht variants studied was chosen based on a previous EPR study showing that heme ruffling increases in the following order: WT < K22M < M13V < M13V/K22M.34 NMR chemical shift data for the heme core 13C meso, α-pyrrole, and β-pyrrole shifts were collected on all four Ht variants. Chemical shifts of selected heme substituents were also measured, including 13C-methyl, 1H methyl and 1H meso chemical shifts. The axial methionine (Met61) ε-C1H3 shift may be influenced by ruffling, as suggested by DFT studies,5 and was measured as well. All of the above mentioned measured chemical shifts are strongly correlated to each other across this series of Ht mutants. As ruffling increases across the series, the 13C meso and 13C methyl nuclei are deshielded, while the 1H meso, 1H methyl, 13C α-pyrrole, 13C β-pyrrole, and Met ε-C1H3 shifts become more shielded. These can be seen in Figure 5, where the difference in the chemical shifts for each of these resonances relative to Ht WT is plotted versus the EPR axial term, Δ/λ, of each variant. Previous work has shown that, as long as other factors that influence ligand-field parameters are not significantly perturbed, the ligand-field parameters for low-spin cytochromes c with His/Met axial ligation correlate well with the amount of ruffling, with the axial term decreasing as ruffling increases.34 The factors expected to change ligand-field parameters the most are the type and orientation of the heme axial ligands,59 which are maintained among these mutants as revealed by the crystal structures of Pa WT42 and Pa F7A,55 as well as NMR data on the Ht variants.45,58 Notably, a similar correlation between ligand-field parameters and heme ruffling has been noted in cyanide-inhibited globins.19 In Figure 5, it is apparent that all changes observed in the chemical shifts of the more-ruffled Ht variants relative to the less-ruffled variants are in the same direction as those observed in the more-ruffled Pa F7A relative to Pa WT. This observation demonstrates consistency in the way in which ruffling influences NMR chemical shifts in these Ht and Pa variants. The chemical shift data for the Ht series of mutants are shown in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Chemical shift differences associated with the Ht K22M, Ht M13V, and Ht M13V/K22M variants relative to WT. Each point represents the value of δ(mutant) − δ(wild-type). Ruffling increases as the EPR axial term decreases (left to right). The His16 β-13C chemical shifts are reported in ref.58 and the EPR parameters and associated errors are reported in ref.34

Analysis of Chemical Shifts

The chemical shift of a nucleus in a paramagnetic species can be expressed as the sum of the diamagnetic shift (δdia), which is the chemical shift in the absence of any influence from the unpaired electron(s), and the paramagnetic shift (δpara), which is a result of the hyperfine interaction between the nucleus and the unpaired electron spin.

| (1) |

For low-spin cytochromes that do not undergo significant redox-triggered structural rearrangements, the diamagnetic shift can be approximated by the chemical shift of the FeII species. The paramagnetic shift can further be described in terms of a through-space metal-centered pseudocontact term , a through-bond Fermi-contact term (δFC), and a through-space ligand-centered pseudocontact term .

| (2) |

The metal-centered pseudocontact shift depends on the nuclear coordinates in the three-dimensional magnetic axes of the metal center, which are largely determined by the orientation of the axial ligands to the heme, and on the magnetic anisotropy.29 The metal-centered pseudocontact shift is described by the following equation:60,61

| (3) |

The terms Δχax and Δχrh are the axial and rhombic paramagnetic anisotropies, and r, θ, and φ are the polar coordinates of the nucleus in the reference frame of the magnetic axes. For nuclei many bonds from the metal center (i.e., excluding the heme and axial ligands), the paramagnetic shift consists solely of a metal-centered pseudocontact component:

| (4) |

The metal-centered pseudocontact shift can then be calculated for any nucleus using δpara values, the protein structure, the magnetic axes, and the values of Δχax, and Δχrh according to Equation 3. For Pa WT and Ht WT, the crystal structures42,55 and the paramagnetic susceptibility tensors32 at 25 °C have been previously determined, allowing for the calculation of the pseudocontact shifts for all heme and axial ligand nuclei. Pseudocontact shifts were calculated for heme nuclei of Pa WT and the results were averaged for each type of heme nucleus (i.e. β-pyrrole 13C, α-pyrrole 13C, meso 1H, etc.; Table 3). This same calculation has been performed previously for the heme methyl nuclei of Ht WT58 and horse cytochrome c.33

Table 3.

Contributions to the paramagnetic chemical shifts (ppm) of the heme and axial ligands of Pa WT and Pa F7A.a

| Pa WT | Pa F7A | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δpara |

|

|

δpara |

|

|

||||

| 1H methyl | 18.55 | −2.87 | 21.42 | 17.86 | −2.73 | 20.59 | |||

| 13C methyl | −55.7 | −4.7 | −50.9 | −54.5 | −4.5 | −50.0 | |||

| 1H meso | −6.91 | −8.41 | 1.50 | −6.97 | −7.60 | 0.63 | |||

| 13C meso | −62.7 | −19.6 | −43.1 | −61.5 | −18.2 | −43.3 | |||

| 13C α-pyrrole | −118.3 | −27.7 | −90.6 | −118.5 | −26.2 | −92.3 | |||

| 13C β-pyrrole | −3.1 | −10.0 | 6.9 | −4.3 | −9.1 | 4.8 | |||

| Met61 ε-C1H3 | −13.99 | 10.04 | −24.03 | −14.04 | 9.78 | −23.82 | |||

| His16 δ1-15N | 48.9 | 19.8 | 29.1 | 44.9 | 19.6 | 25.3 | |||

| His 16 δ1-N1H | 5.17 | 10.0 | −4.85 | 3.87 | 9.7 | −5.87 | |||

Average chemical shifts are reported for heme nuclei

Because the paramagnetic susceptibility tensor of Ht WT had been previously determined at 25 °C,32 the tensor was determined here at 40 °C using experimentally determined pseudocontact shifts for Ht WT (Table S4). A plot of the calculated vs. observed metal-centered pseudocontact shifts is shown in Figure S16. The magnetic axes orientation, given in Table S1, changed minimally from that determined at 25 °C. The anisotropy terms in Table S1 decreased in magnitude relative to those at 25 °C as expected for an increase in temperature. The results of the determination of pseudocontact shifts at 40 °C for the heme and axial ligand nuclei of Ht WT and variants using the magnetic axis parameters are shown in Tables S5 and S6.

The Fermi-contact term is only significant for nuclei of the axial ligands and the heme. For unpaired electron density delocalized in a π-system, the Fermi-contact shift is increased by positive spin density on the measured nucleus, and decreased by positive spin density on adjacent nuclei. The Fermi-contact shift is determined by the following relationship:33,62

| (5) |

The term AH is the hyperfine coupling constant, which can be related to the spin density using empirical proportionality constants that have been determined using organic radicals.63 In heme, the terms used depend on the nucleus as follows:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

In the above equations, ρπmeso, ρπβ, ρπα, and ρπN are the spin densities on the meso carbon, β-pyrrole carbon, α-pyrrole carbon, and pyrrole nitrogen, respectively. The values for the proportionality constants used63 can be found in Table S3. If multiple Fermi-contact shifts of the heme nuclei are known, the above equations (6–10) can be combined with Equation 5 and simultaneously solved to estimate the spin density distribution on the core heme nuclei, as has been performed before for other iron porphyrins.39,64,65 It is important to note that equations (6–10) are derived from simple models, assuming no deviations from the Curie law and only π-delocalization of the unpaired electron onto the porphyrin ligand. Therefore the results should be considered to be qualitative in nature.

For ferricytochrome c, the ligand-centered pseudocontact shifts are insignificant for most of the protein, since the spin density lies primarily at the iron. However, for nuclei on which there is delocalized spin density, including the porphyrin core nuclei and some of the axial ligand nuclei, the ligand-centered pseudocontact shift can be significant.39 The shift is approximately proportional to the spin density at the measured nucleus. This relationship is expressed using an empirical proportionality constant, D.39,66

| (11) |

The presence of a ligand-centered pseudocontact shift necessitates using an additional term when fitting the 13C meso, 13C α-pyrrole and 13C β-pyrrole shifts, since for these nuclei is significant:

| (12) |

Therefore, to fit spin densities, the equation for the 13C meso shift combines equations 5, 8 and 11, and is shown below (Equation 13). The equations for the 13C α-pyrrole and 13C β-pyrrole shifts (Equations S1 and S2) have analogous modifications to include the ligand-centered pseudocontact term.

| (13) |

Using the above analysis, the spin density on the core heme carbons can be determined using the chemical shifts for the FeIII and FeII states, accounting for the pseudocontact shift components. For the analysis, the four heme methyl 1H shifts were averaged, as well as the four 13C heme methyl shifts, the four 1H and 13C meso shifts, four of the eight β-pyrrole 13C shifts, and the eight α-pyrrole 13C shifts. Averaging the NMR chemical shifts for each atom type minimizes the influence of asymmetric distribution of spin densities around the heme and allows analysis without atom-specific chemical shift assignments. Only four of the eight β-pyrrole 13C shifts were collected and averaged from the sample enriched with 4-13C ALA. The other four β-pyrrole 13C shifts would require a different labeling scheme, using an ALA derivative that was not readily accessible at the time that the measurements were made. Atom-specific assignments, although possible,67 would be difficult and would add unnecessary complexity to the analysis.

The results of this analysis performed for Pa WT are presented in Table 4, where a value for D, the proportionality constant from Equation 11, was determined from the fit to the data set. In addition, the same analysis was performed on the chemical shift changes associated with introducing the mutation to prepare the more ruffled Pa F7A variant, using the same value for D that was determined for Pa WT. The results show the change in spin density associated with the 0.4-Å increase in ruffling of the Pa F7A variant. The results are represented pictorially in Figure 6. The same analysis was also performed for Ht WT while also using a best fit value for D. The resulting spin densities are shown in Table 5 along with spin density changes associated with each of the Ht variants, using the value for D determined from Ht WT. The spin density changes are graphed in Figure 7.

Table 4.

Calculated average spin densities for selected heme nuclei of Pa WT and comparison to Pa F7A

| Pa WT | (F7A–WT) | |

|---|---|---|

| meso 13C | −0.00090 | 4.3 × 10−4 |

| β-pyrrole 13C | 0.012 | −2.1 × 10−4 |

| α-pyrrole 13C | 0.0044 | 4.2 × 10−4 |

| N-pyrrole 13C | 0.017 | 8.1 × 10−4 |

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of predicted average spin densities on the α-pyrrole carbon, β-pyrrole carbon, meso carbon, and pyrrole nitrogen. Red and blue represent positive and negative spin densities, respectively. The volume of the glossy spheres is proportional to a) the empirically calculated spin densities in Pa WT and b) the spin density change associated with the F7A mutation. The pyrrole nitrogen is predicted in other studies to have a mixture of positive and negative spin density, with an excess of negative spin density. See text for discussion.

Table 5.

Calculated average spin densities for selected heme nuclei of Ht WT, as well as the changes in spin density between Ht WT and its variants.

| Ht WT | (K22M–WT) | (M13V–WT) | (M13V/K22M–WT) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| meso 13C | −0.0011 | +3.3 × 10−4 | +16 × 10−4 | +24 × 10−4 |

| β-pyrrole 13C | 0.011 | +0.4 × 10−4 | −1.0 × 10−4 | −1.3 × 10−4 |

| α-pyrrole 13C | 0.0044 | +4.2 × 10−4 | +20 × 10−4 | +30 × 10−4 |

| N-pyrrole 15N | 0.015 | +8.1 × 10−4 | +49 × 10−4 | +69 × 10−4 |

Figure 7.

Calculated average spin density changes (Δρ) relative to wild-type for the variants of Ht cytochrome c552 plotted against the EPR axial term for each of the types core porphyrin nuclei.34

Discussion

Relation to previous studies of ruffled hemes

Heme hyperfine shifts have previously been shown to reflect heme ruffling. In particular, the average heme methyl 1H shift has been shown to decrease as ruffling increases in nitrophorins and cytochromes.35,36 In a study that analyzed the heme chemical shifts in Ht WT relative to a less ruffled variant, Ht A7F,5 several hyperfine shifts for the A7F variant were found to change predictably with the decrease in heme ruffling caused by the mutation, although the effect of the mutation on ruffling was quite small (0.05 – 0.1 Å decrease in the out-of-plane displacement of porphyrin ring atoms along the ruffling coordinate). DFT calculations assisted in the interpretation of the NMR results, providing a molecular orbital interpretation of the effects of heme ruffling on chemical shifts. Overall, the study developed the use of NMR of heme nuclei as a qualitative probe of heme ruffling, and supported the hypothesis that increasing ruffling decreases heme reduction potential.5

In the current study, NMR was performed on four variants of Ht cytochrome c552: WT, K22M, M13V, and M13V/K22M; the three mutants have all been shown by EPR and NMR spectroscopy to have increased heme ruffling compared to WT, although the amount of change has not been determined.34 Secondly, NMR of Pa WT, along with a structurally characterized more ruffled variant, Pa F7A, was performed. The X-ray crystal structure of Pa F7A shows that heme ruffling has a magnitude of 0.86 Å in this mutant, compared to 0.49 Å for wild-type.42,43 Results here are broadly consistent with previous work. Heme methyl and heme meso 1H shifts move to lower frequency with increased ruffling, and heme methyl and heme meso 13C shifts move to higher frequency with increased ruffling (Figure 5, Table 1, Table 2). However, although there is broad agreement, a few shift changes deviate from what was seen in the previous study on the Ht WT/Ht A7F pair. The axial Met ε-C1H3 shift and the α-pyrrole 13C shift were introduced as potential probes of ruffling in the previous study on Ht A7F, and both shifts were observed to increase with an increase in ruffling.5 DFT performed on a heme model reproduced the same increase in chemical shift with ruffling. However, in the current study, the more ruffled variants (the three Ht variants and the Pa F7A variant) display decreased Met ε-C1H3 shift and α-pyrrole 13C shifts. These results suggest that complex factors determine chemical shifts of the Met ε-C1H3 shift and the α-pyrrole 13C shift. Variations in axial ligand strength related to the mutations or to ruffling is a factor that may complicate results.

In order to elucidate the complex relationships between heme NMR shifts and ruffling, it is helpful to factor out components contributing to the hyperfine shift. The separation of metal-centered pseudocontact shifts from the contact and ligand-centered pseudocontact shifts has been performed here and allows a detailed determination of factors influencing changes in spin density when ruffling is changed. The analysis also determines how the spin density components for each type of porphyrin nucleus contribute to the chemical shift. The pseudocontact shifts for the mutants were determined using the variants’ g values reported previously5,34 to scale magnetic axis parameters for the wild-type proteins, which were determined previously for Pa WT32 and herein for Ht WT. Diamagnetic reference shifts are shown in Table S2. Results for Pa WT and F7A are shown in Tables 6 and 7, while results for Ht variants are shown in Tables S7–S10.

Table 6.

Contributions to the sum of the average contact and ligand-centered pseudocontact shifts (ppm) for selected heme nuclei of Pa WTa

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H meso | 1.5 | - | - | - | ||||

| 13C methyl | - | −50.9 | - | - | ||||

| 13C meso | −6.9 | - | −36.2 | - | ||||

| 13C β-pyrrole | - | 25.0 | −18.1 | - | ||||

| 13C α-pyrrole | 3.7 | −50.9 | 27 | −70.4 |

The contributions from the spin density on each of the nuclei are shown independently. The data shown are for Pa WT at 25 °C, in units of ppm.

Table 7.

Contributions to the chemical shift difference (ppm) between Pa F7A and Pa WT, (Pa F7A–WT)a

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H meso | −0.71 | - | - | - | ||||

| 13C methyl | - | 0.87 | - | - | ||||

| 13C meso | 3.26 | - | −3.42 | - | ||||

| 13C β-pyrrole | - | −0.43 | −1.71 | - | ||||

| 13C α-pyrrole | −1.76 | 0.87 | 2.55 | −3.34 |

The values take only the contributions from the contact and ligand-centered pseudocontact shifts for heme 1H and 13C nuclei. The total shift difference (Pa F7A–WT) is divided according to the contributions that arise from spin density on each of the four types of porphyrin core nuclei. The data shown are calculated using the difference in chemical shifts of Pa F7A and Pa WT at 25 °C, in units of ppm.

Porphyrin spin densities

The spin density pattern on the porphyrin macrocycle of Pa WT (Table 4) agrees well with that of Ht WT (Table 5). The spin densities determined here also show broad agreement with analysis of spin density on a meso-substituted, low-spin FeIII-porphyrin with two axial 1-methylimidazole ligands.39 Large and positive spin densities are found on the β-pyrrole carbons, a moderate positive spin density is seen on the α-pyrrole carbons, and a small negative density is seen on the meso carbons for both proteins here (Tables 4 and 5, Figure 6). This agreement, along with the general robustness of the results to potential sources of error (described below), provides confidence in the qualitative interpretation of the values obtained.

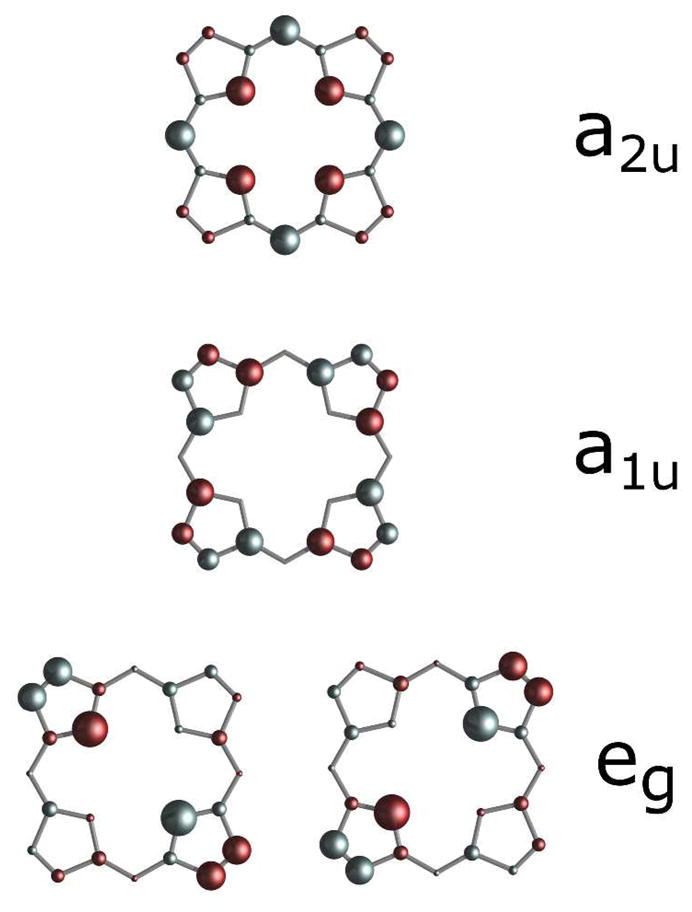

The changes observed for the porphyrin spin densities as a result of increased ruffling were estimated for Pa F7A relative to WT (Table 4), as well as for the series of more ruffled Ht variants (Table 5). The changes are consistent between the two cytochromes, with the only notable difference being that the Ht variants with increased ruffling display greater increases of spin density on the meso carbon, α-pyrrole carbon, and pyrrole nitrogen than is seen for the Pa WT/Pa F7A pair. The trend observed between heme ruffling and empirical spin density changes can be partially understood within the framework of an existing molecular orbital (MO) interpretation of ruffling.5,37,68 In cytochromes c, the unpaired electron primarily lies in one of the iron dπ orbitals (dxz or dyz), with the singly occupied dπ orbital being thermally accessible.33 The iron dπ and porphyrin 3eg orbitals (Figure 8) are the same symmetry, resulting in spin delocalization into the π-system to the porphyrin β-pyrrole carbons. Ruffling of the porphyrin raises the energy of the iron dxy orbital relative to the dπ orbitals and will consequently yield an increase in dxy character of the singly occupied molecular orbital (SOMO), which has been observed by EPR.34,37 The iron dxy and porphyrin 3a2u orbitals (Figure 8) have the same symmetry (b2) in a ruffled (D2d) heme, resulting in a slightly different spin delocalization pattern on the porphyrin for ruffled versus planar hemes. The porphyrin 3eg orbital will have less spin density as ruffling is increased, resulting in a decrease in the β-pyrrole carbon spin density. Also, the 3a2u orbital will have more spin density, resulting in increased meso carbon spin density.

Figure 8.

Graphical representation of porphyrin orbitals showing that eg orbital density is primarily on the β-pyrrole carbons and pyrrole nitrogens, while a2u orbital density is primarily on the meso carbons and pyrrole nitrogens. The area of each circle is proportional to the Hückel coefficients generated with MPORPHW.73

This molecular orbital framework is consistent with the changes observed here in the spin densities of more ruffled variants of both Pa and Ht cytochromes c.. As ruffling is increased, spin densities on the β-pyrrole and meso carbons decrease and increase, respectively, as predicted. The results also indicate that with increased ruffling, the spin densities on the α-pyrrole carbons increase. This experimental result for the α-pyrrole carbons is difficult to predict from MO arguments, since both the 3eg and 3a2u orbitals have small and roughly equal amounts of spin density on the α-pyrrole carbons, which would cause a decrease and increase in spin density, respectively, as ruffling is increased, according to the model described above. The spin density on the pyrrole nitrogens is also predicted here to increase in the more ruffled variants of Pa and Ht cytochrome c, a result that would also be difficult to predict from MO arguments since both the 3eg and 3a2u orbitals have place significant electron density on the pyrrole nitrogens. However, ESEEM (or HYSCORE) studies show a decrease in the hyperfine couplings of the pyrrole nitrogens upon an increase in ruffling, indicating that a different interpretation is needed.19 Indeed, DFT models show a complex spin density on the pyrrole nitrogens with an excess of negative spin density;69 these calculations are consistent with pulsed EPR studies of low-spin ferric porphyrins that indicate negative spin density on the nitrogens.70–72 Thus the simple model applied here cannot provide a reliable prediction of spin densities on the pyrrole nitrogens and how they respond to changes in ruffling.

Contributions to the hyperfine shifts of heme nuclei

Heme methyls

The relationships between ruffling and 1H and 13C NMR shift trends for both Pa F7A and the Ht series of variants are consistent with previous work by Liptak et al.5 (Tables 1 and 2). The methyl carbons attached to the β-pyrroles are outside of the porphryin π-system, and the ligand-centered pseudocontact shift is expected to be small.33 However, the amount of ligand-centered pseudocontact shift should be proportional to and the same sign as the spin density at the β-pyrrole carbons, making it extremely difficult to separate these contributions. Spin polarization occurs due to the large spin density on the β-pyrrole carbon that results from the overlap between the dπ (dxz, dyz) orbitals and the porphyrin 3eg orbital. Therefore, the hyperfine shifts of the 13C methyl resonances are negative. The heme 1H methyls are removed from the porphyrin by a second nucleus and therefore are deshielded via a spin polarization mechanism.37 Upon increased ruffling, spin density on the β-pyrrole carbons decreases and, as a result, the average 13C methyl chemical shift increases and the average 1H methyl shift decreases. This pattern is observed in both Pa F7A and the Ht variants (Tables 1 and 2). In both the Pa and Ht variants, the change in the metal-centered pseudocontact shift has only a small effect, slightly exaggerating the increase in chemical shift of the 13C methyls and slightly moderating the decrease in chemical shift of the 1H methyls upon an increase in ruffling (Table 3, S5, S6).

Heme mesos

In Pa WT 13C mesos are shielded relative to the diamagnetic region due to spin polarization,5,39 and become slightly less shielded in the more ruffled Pa F7A. This same trend in the meso 13C chemical shift is seen in the Ht series of variants, which are more ruffled relative to Ht WT. This may be attributed to an increase in the dxy character of the spin-occupied molecular orbital (SOMO), as shown previously.5,34 Increased dxy character would increase the distribution of spin density in the porphryin a2u orbital, which has electron density primarily on the pyrrole nitrogens and meso carbons.68 However, the results show that an increase in spin density on the meso carbons is only partially responsible for the chemical shift changes (Tables 7, S8–S10). The increase in the meso 13C shift as a result of increased meso carbon spin density is offset by spin polarization from the neighboring α-pyrrole carbons, which have increased spin density with increased ruffling. The two opposing influences are similar in magnitude (Tables 7, S8–S10), and the overall increased 13C meso shift in the more ruffled variants of Pa and Ht cytochromes c is observed only as a result of a decrease in the contribution of the metal-centered pseudocontact shift (Tables 3, S5, and S6).

The 1H meso shift is likewise determined by competing influences that are similar in magnitude, as previously noted.29 In Pa F7A, the pseudocontact shift for the meso positions becomes less negative as a result of increased ruffling, moving the average 1H meso shift to higher frequency. Yet, the increase in meso carbon Fermi contact spin density on the more ruffled Pa F7A causes a more shielded contact shift. The two competing influences are similar in magnitude (Table 7), explaining why the 1H meso shifts do not move predictably with changes in ruffling. Indeed, in both the Ht A7F and the Pa F7A variant, the average 1H meso shift is more shielded relative to WT, despite the fact that Ht A7F decreases and Pa F7A increases heme ruffling. In the Ht series of variants as well as the Pa F7A variant, a decrease in the average 1H meso shift (Tables 1 and 2) demonstrates that as ruffling changes, the change in contact shift tends to slightly dominate relative to the change in pseudocontact shift for these systems.

Core heme carbons

In Pa F7A, a small change of −0.1 ppm relative to Pa WT is observed in the average α-pyrrole shift. Across the Ht series, a large decrease in α-pyrrole shift is observed (−12 ppm) with an increase in ruffling. Moreover, these shift changes occur in the opposite direction as predicted by DFT and measured in Ht A7F.5 Therefore the α-pyrrole 13C shifts do not seem to change predictably with ruffling, indicating complexity in the effect of ruffling on the α-pyrrole 13C shifts, as noted above, and the likelihood that other factors contribute.

This complexity is reflected in the determination of the hyperfine shift components for Pa F7A relative to Pa WT (Table 7) and for the Ht series of variants relative to Ht WT (Tables S8–S10). An increase in the α-pyrrole 13C shift in the Pa F7A variant results from increased spin density on the α-pyrrole carbon, a decrease in spin density on the neighboring β-pyrrole carbon, and a change in the component (Tables 3, 7, S5–S10; Figures 6 and 7). However, the spin densities on both the neighboring meso carbon and pyrrole nitrogen increase in the more ruffled cytochrome variants. Both spin density changes contribute to a decreased α-pyrrole 13C shift. The magnitudes of all chemical shift components are such that small changes in the relative magnitudes of each component could affect the direction and magnitude of how ruffling influences the α-pyrrole 13C shift. This is our proposed basis for the discrepancies between the chemical shift changes observed with ruffling for Ht A7F, Pa F7A, and the Ht series studied in this work. The observed decrease in the average β-pyrrole 13C shifts with increased ruffling was expected due to the decrease in spin delocalization of the porphyrin 3eg orbitals. However, the larger contribution to the decrease in chemical shift was found to be the increased α-pyrrole carbon spin density (Tables 7, S8–S10). The spin density pattern and how spin density responds to heme ruffling are illustrated in Figure 9.

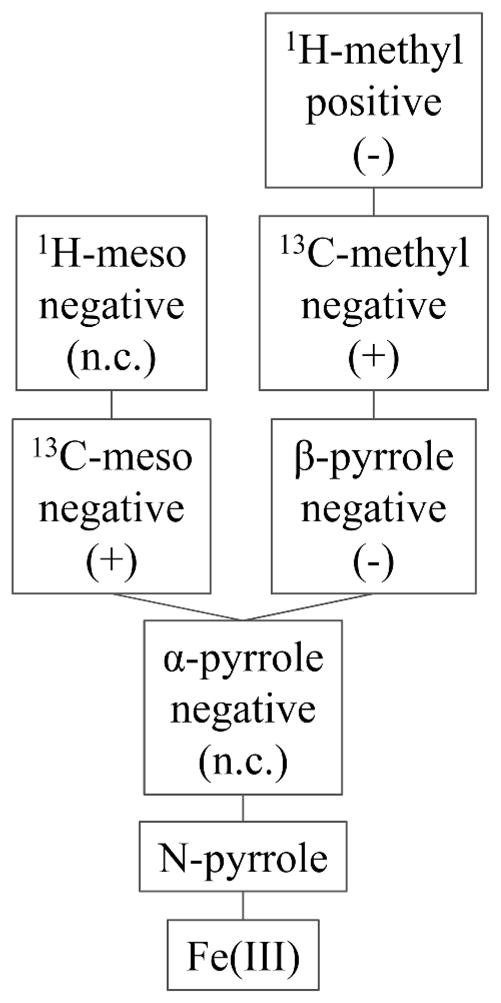

Figure 9.

Spin density pattern and connectivity of heme nuclei. “Positive” and “Negative” indicates the sign of the hyperfine shifts determined from this work, and (+) and (−) indicate an increase (to higher frequency) and a decrease (to lower frequency) in shifts induced by ruffling, respectively. “n.c.” means not consistent; different directions of change of these shifts with increased heme ruffling is observed in different proteins in this study.

Comparison of Ht and Pa variants

The measurement of heme chemical shifts for variants of two different cytochromes c increases confidence in the generalizability of these results. Indeed, the delocalized spin densities on the porphyrin ligand nuclei for Pa WT and Ht WT are similar (Tables 4 and 5). It is possible that the chemical shift changes interpreted in this work are influenced by subtle changes in protein environment or axial ligand interactions, rather than by ruffling. However, the same chemical shift trends as a function of ruffling are observed in both the Pa F7A variant and the Ht series of variants for most nuclei measured. Therefore it is more likely that ruffling is indeed the major factor influencing the observed heme chemical shift changes. However, there exists some discrepancy in the magnitude of the chemical shift changes between the Ht series and Pa F7A. The α- and β-pyrrole 13C shift changes associated with the Ht series of mutants herein are much larger than for the Pa F7A mutation. It is unlikely that this is explained only by a larger increase in ruffling along the Ht series of variants than for Pa F7A, since if the chemical shift change were proportional to the change in ruffling, the Ht M13V/K22M variant would have to be far more ruffled than any cytochrome c previously observed. The larger chemical shift changes seen for the Ht series are caused by larger increases in the pyrrole nitrogen, α-pyrrole carbon, and meso carbon spin densities with ruffling. Since the signs of the chemical shift changes are the same for Pa F7A and the Ht series, spin densities can be expected to change in the same direction. The origin of the different magnitudes of spin density changes is not known, but reveals that heme chemical shift changes may not correlate quantitatively to changes in heme ruffling across different species of proteins, although directions of changes are expected to be predictive of changes in ruffling. Interestingly, changes in the average 1H methyl shift do not perfectly correlate with changes in the average 13C methyl shift, specifically in the comparison of Ht K22M with Ht WT and of Ht M13V with Ht M13V/K22M (Table 2). The heme meso 13C shifts follow the same trend as the heme 13C methyl shift. However, when NMR data from the Pa WT, Pa F7A, the Ht series of variants, and Ht A7F5 are all analyzed, the average 1H heme methyl shift seems to be the best measure of ruffling, providing a consistent general correlation with ruffling in magnitude and direction for all of the variants studied.

Robustness of the results

The value for D, the proportionality constant between the spin density and the ligand-centered pseudocontact shift (Equation 11), was calculated herein to be −2872 ppm per electron spin for Pa WT and −1279 ppm per electron spin for Ht WT. The literature value for a S= ½, FeIII porphyrin in the same electron configuration is −6567 ppm per electron spin.39 A meso-substituted porphyrin was used in the literature determination, contrasting with a β-substituted porphyrin used in this work. This difference in porphryin structure may account for the discrepancy in the literature D value from Goff and those from this work. However, there still exists a large difference in the calculated D value between the Pa and Ht proteins. The difference in the D value determined could be a result of approximations made in this study. The hemes in this study, because of the substituents and the protein environments, are not 4-fold symmetric, yielding different chemical shifts for each nucleus. For the meso protons, meso carbons, and α-pyrrole carbons, the nuclei are related by a 4-fold symmetry axis, so the average term is expected to accurately determine average spin density. However, the heme methyl carbons are distributed asymmetrically around the heme. Therefore, using the four methyl substituents to calculate the average spin density on all eight β-pyrrole carbons will introduce some error. Secondly, an approximation was necessary to calculate the average β-pyrrole 13C shift; only four of the eight β-pyrrole 13C shifts were measured, and the average for these four β-pyrrole carbons was used to approximate the average of all eight β-pyrrole shifts used for the spin density calculations. This approximation was made because measurement of the other four β-pyrrole shifts would require a different labeling scheme and therefore a different synthesis of ALA. Nevertheless, the large difference between the values of D determined here for the two proteins and in previous work by Goff suggests that there are factors that we do not yet know of that influence hyperfine shift.

For the analysis, the calculated value of D was found to be sensitive to changes in the magnitude of the 13C methyl and 13C beta shifts, which may account for some of the difference between the calculated and literature value. However, the overall calculated spin densities were not significantly affected, since spin densities are related primarily to the signs and relative magnitudes of all five nuclear shifts, including the 1H meso, 13C meso, 13C methyl, 13C α-pyrrole and 13C β-pyrrole. The calculated spin densities are not sensitive to changes in shifts of any one nucleus in particular.

Effect of ruffling on pseudocontact shifts

A change in heme ruffling may alter pseudocontact shifts by changing the positions of nuclei within the paramagnetic anisotropy tensor or by changing the magnetic anisotropy. To determine whether the change in heme structure is sufficient to significantly alter pseudocontact shifts of peripheral heme nuclei, the crystal structures reported for Pa WT (PDB: 351C)42 and Pa F7A (PDB: 2EXV)43 were used for calculations of pseudocontact shifts for the nuclei analyzed in this study. The shifts were calculated for each protein using both structures, and the resulting changes in the spin density differences between Pa F7A and Pa WT were reevaluated. It was found that the pseudocontact shifts are not significantly affected by the change in heme structure observed between the crystal structures of Pa WT and Pa F7A, assuming that the magnetic axes and anisotropies remained unaltered.

The orientation of magnetic axes is not be expected to change significantly with ruffling, since this is determined primarily by the orientation of the axial ligands,29 which are the same in the two crystal structures. However, the values for Δχax and Δχrh can be expected to differ, based on the differences in g-values measured by EPR (For example, Pa WT: 3.20, 2.06, 1.23; Pa F7A: 3.15, 2.09, 1.15).34 The differences in Δχax and Δχrh can be estimated based on the g values to provide the best estimate of the effect of the Pa F7A mutation on the metal-centered pseudocontact shift. The magnetic anisotropy terms cannot be calculated directly from the g values, due to a large second-order Zeeman correction.74 However, since the values of Δχax and Δχrh are known for Pa WT, and the g values are known for both Pa WT and Pa F7A, a simple scaling can be performed to estimate Δχax and Δχrh for Pa F7A from the g values. The scaling assumes that the second-order Zeeman correction is proportional to the first-order-Zeeman term, which has been calculated from the g values according to the literature.29 This same estimation of the metal-centered pseudocontact shifts was performed for the Ht variants studied in this work, using the EPR g values from the literature,34 and the resulting estimated anisotropy terms are shown in Table S1. The resulting estimated metal-centered pseudocontact shifts assuming no change in magnetic axes are compared for Pa F7A and Pa WT are in Table 3, and for the Ht variants relative to Ht WT are in Tables S5 and S6. The results show that ruffling has a small effect on the pseudocontact shifts of the heme nuclei relative to the changes in contact and ligand-centered pseudocontact shifts. The changes observed are consistent with an increase in rhombicity in the more ruffled variants.

Ruffling and axial ligand bonding

The axial His chemical shifts have previously been measured and analyzed for the Ht series.45,58 The chemical shifts demonstrate an overall increase in the anionic, or histidinate, character of His16 along the Ht series. This histidinate character is correlated with an increased His16–FeIII bond strength, as revealed by published work.58 In particular, the His16 β-13C shift (Figure 4) of the oxidized protein correlates well with the redox potential and is plotted in Figure 5a versus the EPR axial terms, showing a clear trend where the more ruffled variants have a decreased His16 β-13C shift. Furthermore, as the His16-FeIII interaction strengthens and histidinate character increases, the chemical shifts of the His16 δ15N and δ1H nuclei decrease as predicted.45,75 This observed correlation between ruffling, axial ligand shifts, and heme redox potential provides support for the hypothesis that a change in ruffling modulates the redox potential, and may also influence the axial ligand interactions with the heme iron. For the variants studied here, an increase in ruffling correlates with an increase in the His16–FeIII axial ligand bond strength. For heme proteins that bind exogenous ligands, this may be a part of the mechanism by which ligand binding properties can be modulated by the protein.19 As the axial His becomes a better donor, the iron Zeff decreases, increasing the energies of the Fe orbitals and influencing binding to ligands.76

The mutations made in this work are on the proximal side of the heme, suggesting that the changes to the axial Met61 ε-C1H3 hyperfine shift are indirect as a result of the changes in heme conformation, or a result of a change in the His16–FeIII interaction. The analysis of the values for both Pa WT and Pa F7A demonstrates that the axial Met hyperfine shift change with ruffling is primarily a result of the Fermi-contact contribution. Among the proteins studied here, the Fermi-contact contribution to the axial Met61 ε-C1H3 shift increases with increased ruffling, which is the opposite trend as predicted by an earlier DFT analysis.5 A weakening of the Met61–FeIII bond is expected when considering the trans effect with a stronger His16–FeIII interaction occurring across the series,58 which would decrease the Fermi-contact shift on Met61. The basis for the observed trend is not currently understood.

It has been proposed that the redox potential is lowered by increased heme ruffling.5,9,10 This correlation is observed for the variants studied in this work. Pa F7A, Ht K22M, Ht M13V, and Ht M13V/K22M have been previously determined to have lower redox potentials relative to their respective WT proteins, and among the Ht series of mutants, potential decreases as ruffling increases.45,77 The results here support a general trend between increased ruffling and decreased redox potential.

Conclusions

Heme chemical shifts of variants of two different bacterial cytochromes c demonstrate that ruffling influences low-spin Fe(III) heme hyperfine NMR shifts in a way that is predictable and well-understood for most heme nuclei. An analysis of the metal-centered pseudocontact, ligand-centered pseudocontact and Fermi-contact shifts shows how ruffling influences each of these components for heme nuclei. The paramagnetic shifts were analyzed to evaluate delocalized spin densities on the porphyrin ring, demonstrating that an increase in ruffling decreases the spin density on the β-pyrrole carbons, while increasing the spin densities on the meso carbons and α-pyrrole carbons. In addition, heme ruffling correlates with the axial histidine chemical shifts such that an increase in ruffling correlates with an increase in the axial His–FeIII bond strength. This provides further evidence that heme ruffling may influence axial ligand bonding properties that are important for the function of many heme proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from NIH GM63170 for funding, and thank Linda Thöny-Meyer for the gift of pEC86.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information. NMR spectra (14 figures), and data plots (2 figures), two equations, and 14 tables, including complete lists of individual chemical shifts used. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Shelnutt JA, Song XZ, Ma JG, Jia SL, Jentzen W, Medforth CJ. Chem Soc Rev. 1998;27:31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jentzen W, Song XZ, Shelnutt JA. J Phys Chem B. 1997;101:1684–1699. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jentzen W, Ma JG, Shelnutt JA. Biophys J. 1998;74:753–763. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74000-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howes BD, Brissett NC, Doyle WA, Smith AT, Smulevich G. FEBS J. 2005;272:5514–5521. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liptak MD, Wen X, Bren KL. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9753–9763. doi: 10.1021/ja102098p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagarman A, Duitch L, Schweitzer-Stenner R. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9667–9677. doi: 10.1021/bi800729w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gruia F, Kubo M, Ye X, Ionascu D, Lu C, Poole RK, Yeh SR, Champion PM. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5231–5244. doi: 10.1021/ja7104027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowman SEJ, Bren KL. Nat Prod Rep. 2008;25:1118–1130. doi: 10.1039/b717196j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shokhireva TK, Berry RE, Uno E, Balfour CA, Zhang HJ, Walker FA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3778–3783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0536641100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts SA, Weichsel A, Qiu Y, Shelnutt JA, Walker FA, Montfort WR. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11327–11337. doi: 10.1021/bi0109257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olea C, Boon EM, Pellicena P, Kuriyan J, Marletta MA. ACS Chem Biol. 2008;3:703–710. doi: 10.1021/cb800185h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maes EM, Roberts SA, Weichsel A, Montfort WR. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12690–12699. doi: 10.1021/bi0506573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez ML, Estrin DA, Bari SE. J Inorg Biochem. 2008;102:1523–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caignan GA, Deshmukh R, Zeng YH, Wilks A, Bunce RA, Rivera M. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11842–11852. doi: 10.1021/ja036147i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ukpabi G, Takayama S-iJ, Mauk AG, Murphy MEP. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:34179–34188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.393249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nambu S, Matsui T, Goulding CW, Takahashi S, Ikeda-Saito M. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:10101–10109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.448399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsui T, Nambu S, Ono Y, Goulding CW, Tsurnoto K, Ikeda-Saito M. Biochemistry. 2013;52:3025–3027. doi: 10.1021/bi400382p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh R, Berry RE, Yang F, Zhang HJ, Walker FA, Ivancich A. Biochemistry. 2010;49:8857–8872. doi: 10.1021/bi100499a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Doorslaer S, Tilleman L, Verrept B, Desmet F, Maurelli S, Trandafir F, Moens L, Dewilde S. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:8834–8841. doi: 10.1021/ic3007074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu H, Zhang XP. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:1899–1909. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00070a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Honda T, Kojima T, Fukuzumi S. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:4196–4206. doi: 10.1021/ja209978q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caselli A, Gallo E, Ragaini F, Ricatto F, Abbiati G, Cenini S. Inorg Chim Acta. 2006;359:2924–2932. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gazeau S, Pecaut J, Haddad R, Shelnutt JA, Marchon JC. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2002:2956–2960. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grinstaff MW, Hill MG, Birnbaum ER, Schaefer WP, Labinger JA, Gray HB. Inorg Chem. 1995;34:4896–4902. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li XY, Czernuszewicz RS, Kincaid JR, Spiro TG. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:7012–7023. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schweitzer-Stenner R. J Porphyr Phthalocya. 2001;5:198–224. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu LY, Zhong G, Unno M, Sligar SG, Champion PM. Biospectroscopy. 1996;2:301–309. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shokhireva TK, Weichsel A, Smith KM, Berry RE, Shokhirev NV, Balfour CA, Zhang H, Montfort WR, Walker FA. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:2041–2056. doi: 10.1021/ic061408l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shokhirev NV, Walker FA. J Biol Inorg Chem. 1998;3:581–594. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shokhireva TK, Shokhirev NV, Walker FA. Biochemistry. 2003;42:679–693. doi: 10.1021/bi026765w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker FA. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:391–397. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhong L, Wen X, Rabinowitz TM, Russell BS, Karan EF, Bren KL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8637–8642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402033101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banci L, Bertini I, Luchinat C, Pierattelli R, Shokhirev NV, Walker FA. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:8472–8479. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Can M, Zoppellaro G, Andersson KK, Bren KL. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:12018–12024. doi: 10.1021/ic201479q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shokhireva TK, Shokhirev NV, Berry RE, Zhang HJ, Walker FA. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:941–959. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zoppellaro G, Harbitz E, Kaur R, Ensign AA, Bren KL, Andersson KK. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:15348–15360. doi: 10.1021/ja8033312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker FA. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:4526–4544. doi: 10.1021/ic026245p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rivera M, Caignan GA. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2004;378:1464–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goff HM. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:3714–3722. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang W, Ye X, Demidov AA, Rosca F, Sjodin T, Cao WX, Sheeran M, Champion PM. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:10789–10801. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hobbs JD, Shelnutt JA. J Protein Chem. 1995;14:19–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01902840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsuura Y, Takano T, Dickerson RE. J Mol Biol. 1982;156:389–409. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borgia A, Bonivento D, Travaglini-Allocatelli C, Di Matteo A, Brunori M. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9331–9336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512127200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karan EF, Russell BS, Bren KL. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2002;7:260–272. doi: 10.1007/s007750100292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michel LV, Ye T, Bowman SEJ, Levin BD, Hahn MA, Russell BS, Elliott SJ, Bren KL. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11753–11760. doi: 10.1021/bi701177j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Russell BS, Zhong L, Bigotti MG, Cutruzzolà F, Bren KL. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2003;8:156–166. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0401-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arslan E, Schulz H, Zufferey R, Kunzler P, Thöny-Meyer L. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:744–747. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rivera M, Walker FA. Anal Biochem. 1995;230:295–302. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang JJ, Scott AI. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:739–740. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horio T, Higashi T, Sasagawa M, Kusai K, Nakai M, Okunuki K. Biochem J. 1960;77:194–201. doi: 10.1042/bj0770194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen VB, Arendall WB, III, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Acta Crystallogr Sect D-Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Emerson SD, La Mar GN. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1556–1566. doi: 10.1021/bi00458a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takayama SJ, Takahashi Y, Mikami S, Irie K, Kawano S, Yamamoto Y, Hemmi H, Kitahara R, Yokoyama S, Akasaka K. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9215–9224. doi: 10.1021/bi7000714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Travaglini-Allocatelli C, Gianni S, Dubey VK, Borgia A, Di Matteo A, Bonivento D, Cutruzzolà F, Bren KL, Brunori M. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25729–25734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502628200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Timkovich R, Cai ML, Zhang BL, Arciero DM, Hooper AB. Eur J Biochem. 1994;226:159–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb20037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Timkovich R. Inorg Chem. 1991;30:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bowman SEJ, Bren KL. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:7890–7897. doi: 10.1021/ic100899k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walker FA. Coord Chem Rev. 1999;186:471–534. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kurland RJ, McGarvey BR. J Mag Res. 1970;2:286–301. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jesson JP. In: NMR of Paramagnetic Molecules. La Mar GN, Horrocks WD Jr, Holm RH, editors. Academic Press; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Turner DL. Eur J Biochem. 1993;211:563–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karplus M, Fraenkel GK. J Chem Phys. 1961;35:1312. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ikeue T, Ohgo Y, Saitoh T, Nakamura M, Fujii H, Yokoyama M. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4068–4076. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Niibori Y, Ikezaki A, Nakamura M. Inorg Chem Commun. 2011;14:1469–1474. [Google Scholar]

- 66.It is important to note that D here is not zero-field splitting, which also is typically designed as “D.”

- 67.Rivera M, Qiu F, Bunce RA, Stark RE. J Biol Inorg Chem. 1999;4:87–98. doi: 10.1007/s007750050292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakamura M. Coord Chem Rev. 2006;250:2271–2294. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Johansson MP, Sundholm D, Gerfen G, Wikstrom M. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11771–11780. doi: 10.1021/ja026523j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scholes CP, Falkowski KM, Chen S, Bank J. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:1660–1671. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Magliozzo RS, Peisach J. Biochemistry. 1992;31:189–199. doi: 10.1021/bi00116a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garcia-Rubio I, Mitrikas G. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2010;15:929–941. doi: 10.1007/s00775-010-0655-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shokhirev NV. 2009 Downloaded from www.shokhirev.com.

- 74.Horrocks WD, Greenberg ES. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;322:38–44. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(73)90172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Banci L, Bertini I, Turano P, Tien M, Kirk TK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6956–6960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.6956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Das PK, Chatterjee S, Samanta S, Dey A. Inorg Chem. 2012;51:10704–10714. doi: 10.1021/ic3016035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Takayama SJ, Irie K, Tai HL, Kawahara T, Hirota S, Takabe T, Alcaraz LA, Donaire A, Yamamoto Y. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2009;14:821–828. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0494-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.