Abstract

Purpose

Little is known about the association of intimate partner violence (IPV) with specific HIV treatment outcomes, especially among criminal justice (CJ) populations who are disproportionately affected by IPV, HIV, mental and substance use disorders (SUDs) and are at high risk of poor post-release continuity of care.

Design/Methodology/Approach

Mixed methods were used to describe the prevalence, severity, and correlates of lifetime IPV exposure among HIV-infected jail detainees enrolled in a novel jail-release demonstration project in Connecticut. Additionally, the effect of IPV on HIV treatment outcomes and longitudinal healthcare utilization was examined.

Findings

Structured baseline surveys defined 49% of 84 participants as having significant IPV-exposure, which was associated with female gender, longer duration since HIV diagnosis, suicidal ideation, having higher alcohol use severity, having experienced other forms of childhood and adulthood abuse, and homo/bisexual orientation. IPV was not directly correlated with HIV healthcare utilization or treatment outcomes. In-depth qualitative interviews with 20 surveyed participants, however, confirmed that IPV was associated with disengagement from HIV care especially in the context of overlapping vulnerabilities, including transitioning from CJ to community settings, having untreated mental disorders, and actively using drugs or alcohol at the time of incarceration.

Value

Post-release interventions for HIV-infected CJ populations should minimally integrate HIV secondary prevention with violence reduction and treatment for SUDs.

Keywords/key phrases: HIV, intimate partner violence, jail, criminal justice, antiretroviral adherence, women’s health, mental disorders, substance abuse

Background

“He flushed all of my meds down the toilet. He said he wanted me to die faster from AIDS.”

- 30 year-old Latina woman in jail in a long-standing abusive partnership

Intimate partner violence (IPV) can be a major barrier to longitudinal HIV care, including persistence on antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Bae et al. 2011, Schafer et al. 2012). Poor retention in care along the HIV treatment cascade reduces the likelihood of ultimately achieving viral suppression and increases risk of ongoing HIV transmission (Cohen et al. 2011, Andrews et al. 2012, Gardner et al. 2011). Recent mathematical modeling (Granich et al. 2009), empirical community data (Das et al. 2010, Montaner et al. 2010), and randomized controlled trials (Cohen et al. 2011) confirm the importance of sustained engagement in care as central to the HIV “treatment as prevention” paradigm (Montaner 2011). The U.S. National HIV/AIDS Strategy Plan was recently revised to include: [People living] “…with HIV can be at risk for IPV, which can impede adherence and stability in care” (Gay 2010, National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States (page 28) 2010) to highlight the importance of addressing IPV in secondary HIV prevention efforts. On an international level, a recent UNAIDS Global Report made a similar call: “Given that violence is widespread and that there is a clear association between violence against women and the spread of HIV, national HIV responses must include specific interventions to address violence” (UNAIDS 2010). Efforts to address violence are complicated by the intertwined nature of HIV, IPV, and substance use disorders (SUDs) forming the cornerstones of the “SAVA (substance abuse, violence, and HIV/AIDS) Syndemic” (Singer 1994, J Meyer et al. 2011, Johnson et al. 2003). These overlapping epidemics synergize, resulting in exaggerated negative health consequences.

IPV victimization has been associated with increased sex and drug risk-taking behaviors (Collins et al. 2005, Stockman et al. 2010, Walters and Simoni 1999, Wingood and DiClemente 1997, Cohen et al. 2000, El-Bassel et al. 2005). International research and policy has primarily focused on the ways in which IPV exacerbates gender inequalities and thus HIV risk (WHO and AIDS 2005, WHO and UNAIDS 2009, Jewkes et al. 2010, Maman et al. 2000, Dunkle et al. 2004). IPV likely also affects other health-promoting activities, including HIV-related healthcare utilization and ART adherence (J Meyer et al. 2011). Several small studies have correlated IPV with ART non-persistence and reduced adherence (Cohen et al. 2004, Lopez et al. 2010). In one qualitative study of IPV-exposed women with HIV, active drug and alcohol use were identified as key to perpetuating IPV, though not major barriers to persistent HIV care (Lichtenstein 2006). Drug and alcohol use may play a more important role in disrupting care among populations with HIV and comorbid SUDs (Springer et al. 2010, Clements-Nolle et al. 2008, Palepu et al. 2003).

Like HIV and SUDs, an epidemic of violence is highly concentrated among criminal justice (CJ) populations and associated with increased HIV risk behaviors, particularly among women (Ravi et al. 2007). IPV risk is magnified following release from CJ settings (Weir et al. 2008, Wu et al. 2010), and prisoners are at high risk for discontinuous HIV care in the chaotic period following release (Springer et al. 2004, Stephenson et al. 2005). Whereas continuous HIV care is key to improving individual-level and public health outcomes in CJ populations (JP Meyer et al. 2011, Springer et al. 2011, Althoff et al. 2012.), it is critical to understand negative health impacts of IPV and the barriers IPV poses to engagement in HIV care.

This study seeks to understand IPV as a barrier to HIV treatment outcomes among the CJ-involved, using mixed methods to describe the prevalence, severity, and correlates of IPV victimization. Inclusion of men in the study builds on growing awareness that men experience IPV, though it is likely underreported and stigmatized, particularly in global settings where men’s use of aggression against women may be culturally condoned or encouraged (Melton and Sillito 2011, S. C. Swan et al. 2008, UNAIDS 2010).

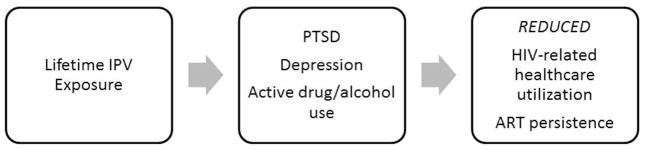

Based on the Behavioral Health Model for vulnerable populations (Gelberg et al. 2000), we hypothesized that the relationship between IPV and HIV treatment outcomes would be mediated by predisposing factors such as mental disorders and SUDs (Figure 1). Study findings have implications for designing multimodal evidence-based interventions that address secondary HIV prevention, IPV, and SUDs.

Figure 1. Hypothesized Model of Intimate Partner Violence as a Barrier to HIV Treatment Outcomes.

IPV=intimate partner violence; PTSD=Post-traumatic stress disorder, ART=antiretroviral therapy

Methods

This is a cross-sectional mixed methods study of IPV among people living with HIV (PLWHA) and recently released from jail in the US. In the US, the CJ system is organized into prisons and jails; the latter houses pre-trial detainees and individuals sentenced to shorter incarceration periods (generally <1 year). Management of HIV in jails is frequently complicated by local bureaucratic control of facilities and rapid population turnover, and is thus a major focus of current interventional research.

Setting and Selection of Participants

Participants were HIV-infected, released jail detainees enrolled in a 10-site Special Project of National Significance described elsewhere (Draine et al. 2011, Chen et al. 2011). Representing the largest cohort of HIV-infected jail detainees (N=1,270), the study addresses homelessness (Chen et al. 2011, Zelenev et al. In Press), SUDs (Chitsaz et al. In Press., Krishnan et al. 2012), recidivism (Fu et al. In Press), mental disorders (Lincoln et al. In Press), new HIV infections (de Voux et al. 2012), retention in HIV care (Althoff et al. 2012.), and women’s service needs (Williams et al. 2013). Data for the current analysis is limited to the Connecticut site, the only one that measured IPV in the survey and where subsequent qualitative interviews were conducted.

Connecticut has an integrated correctional system that includes both prisons and jails, comprised of mostly men (94%) who are predominantly non-Hispanic Black (42%) primarily aged 36–45 years old, and includes 17 facilities for men (13 prisons, 4 jails) and a single facility for women (combination prison and jail) (Connecticut Department of Correction 2012). Recruitment and baseline surveys were conducted in 1 male and 1 female jail that housed detainees from New Haven county from January 2008-March 2011. Eligibility included being HIV-infected, ≥18 years old, and intending to transition to New Haven county following release from jail. After release, participants at the Connecticut site were followed for 12 months, during which they received intensive case management and voluntary buprenorphine maintenance treatment for those meeting pre-incarceration criteria for opioid dependence. Of 123 participants recruited, 84 also completed a case management assessment with measurement of IPV and were included in the final analysis (Figure 2). Participants were referred by case managers to participate in qualitative interviews if they were English-speaking and reachable; no one contacted refused participation.

Figure 2.

Study Involvement by Participants

Considerable concerns have been raised when research subjects include prisoners or, in this case, jail detainees. The US Office of Human Research Protection Program (OHRP) has published specific requirements that must be met by any research project involving prisoners. The Yale University Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Connecticut Department of Correction Research Advisory Committee approved this study, which complied with OHRP guidance on research involving prisoners, including having a prisoner representative serve on the IRB. The parent study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT #00841711) and a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health conferred additional protections.

Quantitative Survey Measures

Data were collected at baseline from a structured interview, case management assessment, and jail-based medical chart review. The primary variable of interest, coded dichotomously, was lifetime IPV exposure, measured by the question “Have you ever been a victim of domestic violence?”

Covariates

Demographic information included: age, gender, race/ethnicity, relationship status, and sexual orientation. Social instability included homelessness, as defined previously (Chen et al. 2011a), food insecurity, defined as hunger for ≥2 consecutive days during the 30-day pre-incarceration period, and social support, measured continuously using the validated 31-item Social Support scale (Huba et al. 1996).

HIV health outcomes included chart-extracted last CD4 count (cells/QL) and HIV-1 RNA viral load (VL; copies/mL) prior to jail-release. Data were analyzed continuously and dichotomously (CD4 ≤200 vs. >200 and VL<400 vs. ≥400); maximal viral suppression was dichotomized at a VL>50 or ≤50 (Services 2011). Participants were asked the year of HIV diagnosis and main risk factor for HIV acquisition. Based on a continuum of care model (Gardner et al. 2011), participants were asked: 1) if they had a usual HIV provider in the 30 days pre-incarceration; 2) if they had ever taken ART; 3) if they were taking ART during the week pre-incarceration; and 4) adherence to prescribed ART in the week pre-incarceration, measured continuously using the Visual Analog Scale (Giordano et al. 2004) and dichotomized at ≥95% or <95% adherence.

Mental disorders were assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Instrument (MINI), Version 6.0 (Sheehan and Lecrubier 1990, Sheehan et al. 1998) and responses were dichotomously categorized if they currently met DSM-IV criteria for the following: major depressive episode; suicidality; post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); generalized anxiety disorder; manic episode; panic disorder; social anxiety disorder; mood disorder with psychotic features; or psychotic disorder. Baseline receipt of psychiatric medications and self-report of prior suicide attempts were dichotomous.

Substance use disorders (SUDs) were based on self-report. Composite severity scores for drug and alcohol use during the 30 days pre-incarceration were calculated using the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), fifth edition (McLellan et al. 1992, McLellan et al. 1985). Scores were measured continuously (range 0–1) and were dichotomized at pre-specified cutoffs (≥0.15 for alcohol and ≥0.12 for drugs) (Rikoon et al. 2006). Participants were asked about ever injecting drugs and duration of drug/alcohol use.

Other lifetime abuse was self-reported using a structured IPV assessment: “Have you experienced abuse?” and “Have you ever experienced any of the following as a child or as an adult: physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, removal from childhood home, or been the perpetrator of domestic violence?” Each category was measured dichotomously and not considered mutually exclusive.

Qualitative Measures

In one-hour, semi-structured interviews, participants were asked about IPV in terms of victimization and use of aggression. Using a life story format (Lieblich et al. 1998, Strauss and Corbin 1990), a timeline of important intimate partnerships, drug use, HIV, and CJ history was obtained. All interviews were conducted in private settings by a single trained interviewer (author JPM). Interviews were audio-taped and transcribed with back-checking for integrity.

Analysis

A cross-sectional mixed methods study design of IPV was deployed. Quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed simultaneously (Hesse-Biber 2010). Quantitative analyses were performed using SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago). Descriptive statistics were stratified by self-report of experienced IPV and by gender, using Pearson’s Chi-squared statistics for categorical variables and independent samples t-test for continuous variables. Correlations between all possible covariates and the outcome of interest, experienced IPV, were explored using bivariate regression.

Qualitative interview transcripts were coded using QSR NVivo 10 (QSR International, Australia) by one author (JPM) and checked by a second author (JF) for accuracy. Pre-determined nodes were generated based on the hypothesized model (Figure 1) and the Behavioral Health Model for Vulnerable Populations (Gelberg et al. 2000). As part of a dynamic process, further nodes were added or expanded to accommodate emerging themes. Illustrative quotes were chosen based on clarity and consistency with given theme, regardless of the demographic characteristics of the speaker. Pseudonyms were used for quotations.

Results

Quantitative

The majority of participants were non-Hispanic black single men in their mid-40s, whose jail-based incarceration lasted 122 days (Table 1), a profile representative of the jail-based population in the US and in Connecticut (Connecticut Department of Correction 2012, Maruschak 2009). While nearly all participants reported having a usual HIV care provider in the month prior to incarceration and living with HIV for almost two decades, only 50% were taking ART in the week prior to incarceration and only 15% of the total sample achieved maximal viral suppression. Thirty-seven percent of participants were taking psychiatric medications, despite high prevalence of Axis I DSM-IV psychiatric disorders (Table 2). SUDs were prevalent and severe, consistent with findings from the complete multisite evaluation of 1270 participants (Draine et al. 2011, Chen et al. 2011b, Chitsaz et al. In Press., Krishnan et al. 2012). Women in this sample were significantly more likely than men to report being homo/bisexual (30.4% versus 5.1%) or having diagnosed bipolar disorder (26.1% versus 6.8%) but were similar to men in terms of all other demographic, HIV health outcomes, mental disorders, and substance use indicators (data not shown).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and HIV Health Characteristics of the Study Sample (N=84)

| Characteristics | Total Sample N=841 |

Experienced Intimate Partner Violence

|

P-value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes N=41 |

No N=43 |

|||

|

| ||||

| Mean age (SD), N=82 | 45.4 (8.0) | 44.2 (8.3) | 46.6 (7.7) | 0.18 |

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity, N=80 | 0.88 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 19 (23.8%) | 9 (47.3%) | 10 (52.6%) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 43 (53.8%) | 22 (51.2%) | 21 (48.8%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino(a) | 18 (22.5%) | 8 (44.4%) | 10 (55.6%) | |

|

| ||||

| Gender | 0.005 | |||

| Male | 57 (67.9%) | 21 (36.8%) | 36 (63.2%) | |

| Female | 26 (31%) | 19 (73.0%) | 7 (26.9%) | |

| Transgender (male to female) | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (100%) | 0 | |

|

| ||||

| Sexual orientation | 0.005 | |||

| Heterosexual | 71 (84.5%) | 30 (42.3%) | 41 (57.7%) | |

| Homosexual/bisexual | 13 (15.5%) | 11 (84.6%) | 2 (15.4%) | |

|

| ||||

| In a relationship | 32 (38.1%) | 17 (41.5%) | 15 (34.9%) | 0.54 |

|

| ||||

| Homeless | 28 (33.3%) | 16 (39%) | 12 (27.9%) | 0.28 |

|

| ||||

| Experienced food insecurity, N=83 | 29 (34.9%) | 16 (39%) | 13 (31%) | 0.44 |

|

| ||||

| Mean number of days incarcerated (SD), N=74 | 122.1 (115.3) | 131.3 (119.8) | 113.8 (112.0) | 0.52 |

|

| ||||

| Mean social support score (SD) | 2.54 (1.15) | 2.56 (1.04) | 2.52 (1.26) | 0.90 |

|

| ||||

| HIV Health Outcomes | ||||

|

| ||||

| Mean baseline CD4 count (SD), N=72 | 463.1 (272.2) | 496.1 (293.5) | 431.9 (250.3) | 0.32 |

|

| ||||

| CD4 ≤200, N=72 | 11 (15.3%) | 4 (11.4%) | 7 (18.9%) | 0.38 |

|

| ||||

| Viral suppression (VL<400), N=72 | 39 (54.2%) | 18 (48.6%) | 21 (60%) | 0.33 |

|

| ||||

| Maximal viral suppression (VL<50), N=72 | 11 (15.3%) | 6 (17.1%) | 5 (13.5%) | 0.67 |

|

| ||||

| Mean years since HIV diagnosis (SD) | 14.1 (7.7) | 16.4 (7.1) | 11.9 (7.8) | 0.008 |

|

| ||||

| Mode of HIV acquisition | ||||

| Heterosexual contact | 62 (73.8%) | 30 (48.4%) | 32 (51.6%) | 0.90 |

| Homosexual contact | 12 (14.3%) | 7 (58.3%) | 5 (41.7%) | 0.48 |

| Injection drug use | 33 (39.3%) | 17 (51.5%) | 16 (48.5%) | 0.69 |

|

| ||||

| Usual HIV provider | 62 (73.8%) | 33 (80.5%) | 29 (67.4%) | 0.17 |

|

| ||||

| Ever on ART | 67 (79.8%) | 35 (85.4%) | 32 (74.4%) | 0.21 |

|

| ||||

| On ART past 7 days | 40 (47.6%) | 21 (51.2%) | 19 (44.2%) | 0.52 |

|

| ||||

| ≥95% ART adherence | 25 (29.8%) | 13 (31.7%) | 12 (27.9%) | 0.70 |

IPV=intimate partner violence; ART=antiretroviral therapy; SD=standard deviation; VL=viral load

Table 2.

Baseline Mental Disorders, Substance Use, and Abuse Experiences of the Study Sample (N=84)

| Characteristics | Total Sample N=841 |

Experienced Intimate Partner Violence | P-value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes N=41 |

No N=43 |

|||

| Mental Disorders | ||||

| Current receipt of psychiatric medications, N=83 | 31 (36.9%) | 18 (43.9%) | 13 (31%) | 0.22 |

| Ever attempted suicide, N=83 | 32 (38.6%) | 19 (46.3%) | 13 (31%) | 0.15 |

| Major depressive episode, N=75 | 42 (56%) | 24 (64.9%) | 18 (47.4%) | 0.13 |

| PTSD, N=75 | 15 (20%) | 9 (24.3%) | 6 (15.8%) | 0.36 |

| Suicidal, N=75 | 36 (48%) | 22 (61.1%) | 14 (38.9%) | 0.05 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder, N=75 | 14 (18.7%) | 7 (18.9%) | 7 (18.4%) | 0.96 |

| Manic episode, N=75 | 25 (33.3%) | 13 (35.1%) | 12 (31.6%) | 0.74 |

| Panic disorder, N=75 | 11 (14.7%) | 6 (16.2%) | 5 (13.2%) | 0.71 |

| Social anxiety disorder, N=75 | 13 (17.3%) | 8 (21.6%) | 5 (13.2%) | 0.33 |

| Mood disorder with psychotic features, N=75 | 12 (16%) | 7 (18.9%) | 5 (13.2%) | 0.49 |

| Psychotic disorder, N=75 | 3 (4%) | 1 (2.7%) | 2 (5.3%) | 0.57 |

| Substance Use | ||||

| Ever injected drugs, N=65 | 35 (53.8%) | 15 (50%) | 20 (57.1%) | 0.57 |

| Mean years any drug use (SD) | 19.0 (11.0) | 18.6 (11.8) | 19.5 (10.3) | 0.70 |

| Mean years any alcohol use (SD) | 16.3 (14.0) | 16.4 (13.8) | 16.1 (14.3) | 0.94 |

| Mean ASI, alcohol (SD) | 0.190 (0.280) | 0.266 (0.326) | 0.117 (0.206) | 0.01 |

| ASI alcohol ≥0.15 | 31 (36.9%) | 18 (43.9%) | 13 (30.2%) | 0.19 |

| Mean ASI, drugs (SD), N=78 | 0.163 (0.158) | 0.188 (0.171) | 0.138 (0.142) | 0.16 |

| ASI drugs ≥0.12 | 40 (51.3%) | 23 (59%) | 17 (43.6%) | 0.17 |

| Abuse | ||||

| Childhood physical abuse, N=83 | 30 (36.1%) | 20 (50%) | 10 (23.3%) | 0.01 |

| Childhood sexual abuse | 17 (20.2%) | 11 (26.8%) | 6 (14%) | 0.14 |

| Childhood neglect | 23 (27.4%) | 16 (39%) | 7 (16.3%) | 0.02 |

| Childhood removal from home, N=80 | 12 (15%) | 10 (25%) | 2 (5%) | 0.01 |

| Adulthood physical abuse | 33 (39.3%) | 27 (65.9%) | 6 (14%) | <0.001 |

| Adulthood sexual abuse | 15 (17.9%) | 13 (31.7%) | 2 (4.7%) | 0.001 |

| Domestic violence perpetrator, N=83 | 30 (36.1%) | 24 (60%) | 6 (14%) | <0.001 |

Unless otherwise noted for each variable

For categorical variables, chi-square was used. An independent samples t-test was used for continuous level variables.

IPV=intimate partner violence; PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder; ASI=Addiction Severity Index; ART=antiretroviral therapy

Nearly 93% of respondents reported lifetime experiences of abuse (data not shown) and nearly half identified as IPV-exposed. IPV-exposed participants were more likely to be living with diagnosed HIV for longer, homo/bisexual, suicidal, and have higher alcohol use severity (Table 2). IPV-exposed participants more often experienced other forms of lifetime violence, but did not differ from non-IPV-exposed participants with respect to HIV treatment outcomes or healthcare utilization, in contrast to the hypothesized model.

There were clear gender differences in terms of IPV experiences: 73% of women surveyed reported IPV experiences compared to 37% of men (data not shown). Women and men were equally likely to report using aggression within intimate partnerships (30.4% versus 39.0%, p=0.47) (data not shown). By bivariate logistic regression (Table 3), however, women were three times more likely to report experiencing IPV compared to men. Other significant independent correlates of IPV-exposure included having a current or lifetime diagnosed major depressive episode (OR=2.72; 95% CI 1.11–6.67), experiencing other forms of abuse as a child and adult, and using aggression within intimate partnerships (i.e. being a “domestic violence perpetrator”) (OR=6.19; 95% CI 2.27–16.83).

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlates of Self-Reported Experience with Intimate Partner Violence on Quantitative Assessment

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | Ref | 0.036 |

| Female | 2.94 (1.07–8.02) | |

| Major depressive episode | 2.72 (1.11–6.67) | 0.028 |

| PTSD | 2.67 (0.73–9.69) | 0.136 |

| ASI alcohol ≥0.15 | 1.94 (0.80–4.74) | 0.141 |

| Childhood physical abuse | 3.50 (1.33–9.24) | 0.01 |

| Childhood neglect | 2.94 (1.07–8.02) | 0.036 |

| Childhood removal from home | 4.24 (1.06–17.04) | 0.042 |

| Adulthood physical abuse | 9.71 (3.3–28.57) | <0.001 |

| Adulthood sexual abuse | 17.52 (2.14–143.48) | 0.008 |

| Domestic violence perpetrator | 6.19 (2.27–16.83) | <0.001 |

IPV=intimate partner violence; PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder; ASI=Addiction Severity Index

Qualitative

Quantitative and qualitative IPV measurements were discordant. While 6 of 14 men and 5 of 6 women reported IPV exposure on quantitative instruments, 2 additional men and 1 additional woman identified as IPV-exposed on qualitative interviews. Many participants in the qualitative interview discussed both IPV victimization and their use of aggression; some had faced criminal charges related to these behaviors, including assault, breach of peace, domestic violence, and violation of protective orders. As in quantitative assessments, the majority of qualitative interview participants were black, single, heterosexual men with a mean age of 50 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Table of Attributes of Participants in Qualitative Assessment

| Pseudonym | Age (years)1 | Gender | Race/ethnicity | Sexual Orientation | Marital Status1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mary | 46 | F | Black, Cherokee | homosexual | single |

| Kathy | 42 | F | White | bisexual | separated |

| Nancy | 44 | F | Black | heterosexual | single |

| Sheila | 48 | F | Black | bisexual | single |

| Susan | 45 | F | Black | heterosexual | common law |

| Amy | 56 | F | White | bisexual | divorced |

| Allison | 44 | F | Black | heterosexual | single |

| Chris | 51 | M | Black | heterosexual | common law |

| Bill | 53 | M | Hispanic | heterosexual | single |

| Michael | 52 | M | Hispanic | heterosexual | single |

| Robert | 59 | M | Black | heterosexual | married |

| James | 53 | M | Black | heterosexual | single |

| John | 58 | M | White | heterosexual | unknown |

| Bob | 56 | M | White | heterosexual | single |

| Alex | 54 | M | White | heterosexual | divorced |

| Miguel | 44 | M | Hispanic | heterosexual | divorced |

| Tom | 59 | M | Black | heterosexual | divorced |

| Luis | 53 | M | Hispanic | heterosexual | divorced |

| Brian | 47 | M | Black | heterosexual | single |

| Caleb | 50 | M | Black | heterosexual | single |

| Summary statistics |

mean 50.7 median 51.5 |

65% M 35% F |

55% Black 20% Hispanic 25% White |

80% heterosexual |

50% single 30% divorced or separated |

At time of baseline assessment

F=female; M=male

We first describe the prevalence and severity of IPV in this cohort, focusing on the direct and indirect effects of IPV on health outcomes. We then explore several major identified thematic contexts in which there was both increased risk of IPV exposure and disruptions in HIV care.

IPV Prevalence and Severity

Physical altercations between partners were often described as minor, though several participants described events more consistent with severe physical IPV, suggesting an altered perception of severity of IPV.

Mary: It was crazy, [my boyfriend] shot me…it came in…my temple and it went out the back of my head. And he left me for dead at the hospital.

Kathy: [My boyfriend] round-housed me, he broke my nose …I got this scar here from him from a kick that he landed on the side of my eye, he broke a kitchen table with me…He threw me into the kitchen table.

Nancy: This just recently happened (points to scar on forehead) and this is why we have a full restraining order now…I told [my boyfriend] I didn’t want to be with him I was with somebody else…And he said I been with you 17 years and you ain’t gonna leave me, you my common law wife. And I was like no I ain’t no more….He put me in a headlock. When he put me in a headlock he put me to sleep. A sleep headlock. And when he let me go my head went boom, split all open blood everywhere, oh lord.

IPV Manifested as Sabotage of Health

Several participants detailed how their abusive partners purposefully sabotaged their health and deprived them from seeking medical care. Sheila described being raped by her husband the day of her tubal ligation because she had not obtained his permission for the procedure.

Sheila: My three kids’ father…was mad that I had my tubes tied…he was talking about don’t do it cause you gonna have my kids, you’re the only one I want to have my kids...later [that night] he came from New York and he found out I had it tied and…he laid on me, I said get off my stomach…he forced to have sex with me.

Other women described their isolation, both socially and from medical care, in the context of abusive partnerships:

Nancy: We were staying…in an abandoned building… I went to leave and [my boyfriend] went to twist [my arm], when he went to like twist it all the way I retaliated with him to tell him to get off my arm cause it was hurting but I went to pull like that and the bones went click like that I heard it snap. I thought it was gonna pop right out of my arm….he wouldn’t take me to the hospital right away so it got swollen … But it really didn’t hurt that much as long as I didn’t move it. I caught a fever and then he had no choice.

Kathy: Literally I was just kept upstairs. It was very strange…I don’t think I left that house for probably a good year. [My boyfriend - a drug dealer and pimp,] would just keep feeding me drugs and he’d bring up food if and when I ate…And I never really went outside or anything. [He] definitely kept me isolated. He had me thinking I was actually crazy because I know at one point he threw me down the stairs and I broke my arm and he had me so sure that he was not even in the house when that happened…

Sheila described another past partner who used HIV as a weapon against her and infected her with HIV to maintain control in the relationship. He was a sexual partner and her business partner in a drug trafficking ring. Sheila was aware that he had at least three other sexual partners and injected heroin, but felt powerless to leave or to negotiate using condoms.

Sheila: He was like nobody in this town gonna have you. This is my town…and plus we got a lifetime contract… and then when the lady said that [I was HIV positive] that’s all I could hear. And then I could picture him shooting the needles and his track marks and I was like oh my god…Obviously he had already knew he was HIV positive.

IPV and HIV Treatment Outcomes

Despite abusive deprivation of emergency medical care, many participants described being self-sufficient in terms of HIV care and taking ART. This may have been related to the long time since their HIV diagnosis.

Nancy: No, [my boyfriend] would never stop me from [taking my medication] ‘cause I would never let him do that. You don’t want to take yours but I’m going to take mine…I tell him, you better get with the program. You don’t want to get with the program, you’ll know about it when you turn full blown. It’s too late then.

Interviewer: Does [your wife] help you remember medications?

James: Don’t have to. That’s my job…I mean you want to live or you don’t want to live. I mean I listen to doctors and you don’t want to build up a resistance to the medications, you can’t take ‘em and stop, take ‘em and stop. So that’s what it is, so I take them faithfully.

Not all participants explicitly identified IPV as a barrier to their HIV care. Instead, three primary contexts were repeatedly identified that increased risk of both IPV exposure and disruptions in HIV care: 1) transitioning from jail/prison; 2) having untreated mental disorders; and 3) actively using drugs or alcohol. These contexts were often overlapping and are explored further here.

Transitioning from Jail or Prison

IPV Exposure

Women and men identified experiences of IPV that occurred during extreme vulnerability, primarily following release from CJ settings. During this transition, inequity of resources magnified power imbalance within relationships. Participants described a willingness to tolerate abuse in exchange for basic needs. Physical violence directly impacted health and placed individuals at high risk for relapsing to drugs and alcohol.

Nancy: And [when I got out of jail, my boyfriend] was like my safe link cause he had the money and he had always put a roof over my head. And anything I needed…He gave it to me like that. So I felt like without him I’d be lost. Cause he was the only one that was a part of me like that. But then after again…you can’t let this keep on going. I mean it’s to the point where he had actually choked me in the house by ourselves and [I] couldn’t breathe at all. I mean like a 15 minute choke.

Chris was in a recent volatile relationship with a woman he described as an “angry, violent drunk.” He stated, “we had a few uh incidences where, basically she was the aggressor and matter of fact I got a, what do they call it, restraining order against her now.”

Chris: I didn’t have nowhere to go and she had money…she had a place …when I first came out [of jail] the first week or two I was in the shelter and like I didn’t want to be there…well anyway I ended up going back with her…at that time she was willing to support me, gave me a place, bought me a few outfits, so I went back with her. But yeah it got ugly cause we started using together again, same cycle all over again you know back you know same cycle you know, it’s a vicious cycle and it was like the same thing happening over again.

James: I didn’t want to have to go to jail, come out, and stay with somebody again. I like to have my own place. Usually…it’s not my own…I usually live with a female like her… I stayed there [with my girlfriend] and I put up with whatever because I knew that one day I wouldn’t have to put up with it anymore…She calls me a liar and she actually punches me in my face. And if I try to walk away, she grabs on me…

HIV Treatment Outcomes

When participants were asked about their priorities upon release from jail or prison, only two cited HIV care or health as top priorities; the majority responded housing. In reality, even basic subsistence and health needs were deprioritized relative to the demands of addiction.

Kathy: I got out, I called my friend…to pick me up here in New Haven and at that point…it was either a or b. I was either going to stay here and deal with things and go do the right thing or b I was going to see if I could scam [him] out of $100 bucks so I could go get high. Well I was able to scam [him] out of $100 bucks so I went and got high.

Bill: I was locked down for the last 15 years and so much has changed to get back into society, to feel comfortable with myself, I figured the first thing I would do is go back to using just to get rid of the nervousness and the thought of being back out here.

Several participants described improved adherence to ART and engaging in HIV care during their incarceration. These benefits were sometimes lost after release, although individual experiences varied.

Chris: For the most part I was like in denial, it’s like okay I’m positive. You know I like put it in the back of my mind. I was pretty heavily using at the time; I didn’t really think about it you know, drugs and what I was doing so…Mainly the only time…that I dealt with it was when I was incarcerated…In jail I would you know take the meds, in jail and then I get out, start running the streets, I wouldn’t take ‘em.

Interviewer: Did you ever fill prescriptions when you got out?

Chris: Couple of times, couple of times, yeah… [But] it’d fall apart yeah. Runnin’ the street, using drugs and you know just stopped taking him. Or you take ‘em sporadically or whatever.

Interviewer: Did you go to your doctors’ appointments?

Chris: Very seldom.

Bob: I was incarcerated when I started my medication and it was just a routine, same time day after day… So when I got out, there was already this routine I had and I’m sure that it had a big difference in keeping up with my medication every day.

Untreated Mental Disorders

IPV Exposure

Several participants described how untreated mental disorders increased their partners’ physical aggression and were exacerbated by alcohol or drug use.

Interviewer: The other times that it got physical [between you and your boyfriend]…were drugs always involved?

Nancy: Drinking…I can drink and have fun, but him, since he was bipolar, so when he drinks he thinks he’s mighty man, so you can’t tell him nothing…He wants to be in control but he was very jealous at the same time too… you could see like the bipolar coming out of him because the way he’d be.

Interviewer: Was he ever on psych meds?

Nancy: He never took ‘em. They had him on Seroquel...to make him stop hearing things like voices to make him do things, you know. And he never really took the meds.

Susan described how her own untreated depression was paralyzing in the context of an abusive relationship, in which her partner became her coercive pimp.

Susan: The house that I used to get high at and stay at, this base house, [my boyfriend] used to come over there, I want you to do this and I want you to do that [prostitute] so I said okay. I ended up doing what he wanted me to do and he said I’m gonna get you out of this house sooner or later… When I used to get high I just always asked God to help me ‘cause I always wanted to feel better. And I didn’t want to feel better as in getting high every day I wanted to go outside in the morning, not stay at a drug house morning and night getting high. I always wanted to, oh I can walk out the door and I could see the sunlight and not the darkness and not four walls all the time getting high. I wanted to be able to go outside and know I’m gonna be okay today like that.

HIV Treatment Outcomes

Many participants described experiencing depressive symptoms due to isolation from communities, social networks, and healthcare systems. John, who had spent over half of his life incarcerated, had most recently been charged with domestic violence and assault against his wife. Upon release from jail, a restraining order against him triggered an episode of depression, during which he stopped taking all of his ART and other medications.

John: Can I tell you something? I quit taking my meds…Don’t care anymore. I considered it suicide…Don’t care. Haven’t been taking my Diabeta (for diabetes) or my Actos (for diabetes) or my Tricor (for dyslipidemia).

Interviewer: Because you want to die?

John: I don’t know, I don’t care. I don’t care anymore, my life is just…I’m living on…the worst street in the city. Can’t get away from all the drugs around me, I have no job, had to sell my vehicles to pay my rent, I just came from social security administration I’m only able to get 731 dollars a month cause I’ve been locked up so long in my life…my dog died. That’s why I didn’t go to the renal doctor. I don’t want to hear any more bad news. I think it’s gonna push me over, you know, make me want to do something to somebody. Does that make sense? I don’t want to be forced into that. I try to tell people that. I try to tell my doctor that. I don’t need any bad news right now. I can’t take anymore right now.

John’s statement illustrates the association between depressive symptoms and medication non-adherence, which ultimately affects treatment outcomes.

Active Drug or Alcohol Use

IPV Exposure

IPV was consistently described in connection with active drug or alcohol use. Violence occurred in the setting of procuring drugs (“go out and get some or else”) or using drugs (“he took a hit in the car, pushed me out the car and backed up to run me back over”), and was exacerbated by discordance in partners’ drug use.

Kathy: I had gotten arrested for prostitution…and he wanted me to go out and get drugs. I just got arrested for prostitution I can’t go back out there, are you crazy?...And he’s like I don’t care you’re going back out….So anyway I ended up getting money and we got high and it was all fine and then he wanted me to go back out. And at that point I refused, I flat out refused I said no way…And he proceeded to beat the crap out of me.

Bill: I always used [heroin] as [an] escape route. Actually I realized I used to look for excuses just to go and use. Probably looked for an argument just to get away from the house and go use, you know. Look for any little excuse, you know, any little argument just to walk away. So that basically destroyed all my relationships, my drug use.

Michael: Well, mostly, it’s that I’m clean and sober and have been, um, and she’s not. I mean, she doesn’t do drugs but she does drink. When she goes beyond, um, you know drinking too much she’ll start arguing for no reason at all and then starts pushin’ my buttons and gets me going and you know I try to avoid it but sometimes I can’t. And that’s when it’s gotten physical.

Mary was one of the few participants who described IPV exposure and use of aggression within a same-sex intimate partnership. After her last violent heterosexual relationship (see above quotation), she said, “I don’t even date guys no more, I’m a lesbian. I don’t…no…stay away from em. It’s like x-ed out.” Within a same-sex partnership, IPV occurred in the setting of discordant drug use and was precipitated by acknowledgement of her partner’s drug use:

Mary: I was clean but that person wasn’t. She was a pill popper, oxys, vicodin, this-a-din and that-a-din…She was just sleeping, nodding, sleeping, nodding…So I said you remind me of a dope fiend and she wokes up just then and…She said well if you feel that way, you can bounce…What do you mean go out there then it was raining and I have no other way to leave so I had to wait. I slapped her because she already knew I was on parole. And I knew I was going back to jail. So I said well, since I’m going back anyways, pow, might as well get a slap in. Then she fainted to the floor saying that maybe I killed her…she called the cops, told her story, they came. They brought me back to jail.

Several participants noted that, in the throes of active drug use, intimate partnerships were impossible to maintain. Sheila described, “You love whatever’s in front of you and whoever’s supplying it.”

HIV Treatment Outcomes

Active drug use was associated with lapses in self-care and HIV care:

Kathy: I didn’t go to my doctor, I stopped going to the pharmacy to get my medicines so I didn’t have them to take, it was just… it was not a priority at the time. Getting high and living that crazy stupid life was a priority.

Robert: [When I got high], I would stop taking the medication. I wouldn’t…Like let’s say I went on a binge right now and I bought an 8 ball or something like that I wouldn’t mess with the medication. I actually don’t think my liver could stand it. I guess you could say I might be too smart for my own good.

Discussion

This is the first evaluation of IPV among people with HIV released from jail. We found a high prevalence and severity of IPV victimization in a population at risk of both IPV and discontinuous HIV care, particularly in the setting of depression and SUDs. We identified a specific period of magnified risk— the period of transition from CJ settings to communities— when limited access to resources may lead people to remain in situations where they are at high risk for IPV.

Although quantitative analyses suggested no effects of lifetime experienced IPV on current HIV outcomes, qualitative findings supported our hypothesized model—that violent and unstable relationships directly related to recidivism, relapse to drugs and alcohol, and disrupted healthcare continuity. Causality could not be established in this relatively small cross-sectional study, but may be irrelevant. For PLWHA, lifetime experiences of incarceration, IPV, SUDs, and mental disorders coexist and synergistically affect health (Sullivan et al. 2012, Cohen et al. 2004). It may be difficult to disentangle IPV from overlapping SUDs, HIV, and mental disorders (Singer and Clair 2003, Singer 1994), particularly in contexts of social and structural instability generated by poverty, homelessness, and transition from the CJ system.

HIV secondary prevention interventions must target IPV along with SUDs as barriers to HIV care continuity. For instance, medication assisted therapy (MAT) for opioid dependence has been found to improve HIV treatment outcomes for opioid dependent released prisoners with HIV (Springer et al. 2010). MAT should be incorporated into IPV interventions that facilitate HIV continuity of care. Recent data that retention on buprenorphine treatment after release from prison was independently correlated with maximal viral suppression, lends support for this approach (Springer et al. 2012). Evidence-based substance abuse treatment may decrease the likelihood that individuals remain in drug use environments or abusive relationships because of needs for subsistence or continued access to drugs. The effectiveness of MAT in maintaining excellent HIV treatment outcomes may, in part, be due to a reduced contribution of drug use to the SAVA syndemic. Empirical research should address structural and behavioral mechanisms through which IPV and SUDs impede care.

Quantitative secondary analysis was limited by available data. Some measures, including IPV, were not collected using validated instruments and may have been under-reported because of social desirability or recall biases. The terms “domestic violence,” “abuse,” “victim,” and “perpetrator” have essentially been abandoned in contemporary violence literature because of their subjectivity, and have been replaced by behavioral-specific measures (Dekeseredy 2000, Gordon 2000). Despite use of these terms in this quantitative survey, these data represent all that was available from the largest study of jail detainees with HIV from the only one of ten sites that measured IPV at all. Qualitative findings may have restricted generalizability to other populations with HIV or to CJ populations in prisons versus jails; we expect, however, that the major identified themes have broader applicability to both US and international settings.

This study is innovative in its inclusion of both women and men. Women in our study were three times more likely than men to report IPV-exposure in quantitative assessments, reflective of the disproportionate burden of violence experienced by women worldwide (Tjaden 1998, WHO 2005). Consistent with existing literature (Archer 2000, Johnson 2006, Johnson MP 2005), women also reported greater severity of physical and sexual IPV despite achieving parity with men in measured HIV treatment outcomes, SUD, and mental disorders. For many of the women in this study, transactional or “survival” sex occurred in the setting of IPV and ongoing drug use. Commercial sex work was, at times, coerced and may have been a mechanism by which partners exerted control and power over women (Karandikar and Próspero 2010). Commercial sex work also put women at risk of other forms of violence, a highly nuanced issue which deserves further targeted research (Decker et al. 2010).

It is critical to note that simply because both men and women experience IPV does not imply that both have the same motives for using IPV (Caldwell et al. 2009, Bair-Merritt et al. 2010) nor does it mean that IPV has similar consequences for men and women (Suzanne C. Swan et al. 2008). In fact, extant literature shows that men’s use of IPV against women is more detrimental in terms of physical and mental health than women’s aggression against men (Whitaker et al. 2007, Carbone-Lopez et al. 2006, Temple et al. 2005, Caldwell et al. 2012). Our findings are consistent with this theme and qualitative data reflects that women’s IPV victimization was associated with feeling fearful, isolated, and disempowered whereas men’s IPV victimization occurred only in the setting of disempowerment.

Although few men reported IPV-exposure on the quantitative survey, most men reported IPV-exposure during qualitative interviews, suggesting that quantitative surveys likely underdiagnose IPV among men. According to a holistic model of IPV, subjective interpretation of behaviors is critical to accurate IPV assessments (Lindhorst and Tajima 2008). Gender asymmetry may have been exaggerated by IPV screening questions that operationalized IPV in terms of legal definitions of crimes, which has specific implications for people who interact with the CJ system. Men’s interpretation of IPV and relative minimization of their IPV experiences likely also related to cultural expectancies, in which it is unacceptable for men to be victimized by women. Furthermore, recognition of IPV was likely influenced by the social construction of IPV, in which men disproportionately perceive IPV as a normative part of drug culture and may not flag IPV as problematic behavior, though it clearly affects decision-making and health outcomes.

Though the sociocultural construction of IPV seemed to affect men and women in different ways overall, individual interpretations of IPV varied, even among participants of the same gender. Interpretation of other trends may have been limited by the study’s relatively small sample size. It is noteworthy that all but one participant described IPV in terms of opposite-gender partnerships, despite some participants identifying as homo/bisexual. Convergence of sexual identity with IPV likely relate to HIV-associated risk-taking, though the topic is beyond the scope of this paper.

Our findings suggest that interventions that aim to improve HIV, SUDs, or mental disorders, must address IPV in gender-specific ways that are tailored to individual contexts. Of 30 interventions listed as effective by the Centers for Disease Control (www.effectiveinterventions.org), only one addresses IPV within a secondary HIV prevention program for women (Wingood et al. 2004). There have been no evidence-based interventions developed to address these issues among men or women within the CJ system, an area that deserves future research.

Summary

Among released jail detainees with HIV, IPV was prevalent and severe. Risks of IPV exposure and disrupted HIV treatment were magnified in contexts of untreated mental disorders and SUDs. IPV occurred during periods of dependence on partners, particularly in transition from jail or prison, during which IPV is a key component of social instability.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments and Funding

Primary funding for this research was provided by the Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (H97HA08541). The authors would also like to acknowledge career development funding from the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (T32 AI007517 for JPM), the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH020031 for JPM) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K24 DA017072 for FLA; K23 DA019561 and R01 DA031275 for TPS; K02 DA032322 for SAS; and K23 DA033858 for JPM). The funding sources played no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Contributor Information

Jaimie P. Meyer, Department: Medicine, University/Institution: Yale University School of Medicine, Town/City: New Haven, State (US only): Connecticut, Country: USA. Department: Chronic Disease Epidemiology, University/Institution: Yale University School of Public Health, Town/City: New Haven, State (US only): Connecticut, Country: USA

Jeffrey A. Wickersham, Department: Medicine, University/Institution: Yale University School of Medicine, Town/City: New Haven, State (US only): Connecticut, Country: USA

Jeannia J. Fu, Department: Medicine, University/Institution: Yale University School of Medicine, Town/City: New Haven, State (US only): Connecticut, Country: USA. Department: Chronic Disease Epidemiology, University/Institution: Yale University School of Public Health, Town/City: New Haven, State (US only): Connecticut, Country: USA

Shan-Estelle Brown, Department: Medicine, University/Institution: Yale University School of Medicine, Town/City: New Haven, State (US only): Connecticut, Country: USA

Tami P. Sullivan, Department: Psychiatry, University/Institution: Yale University School of Medicine, Town/City: New Haven, State (US only): Connecticut, Country: USA

Sandra A. Springer, Department: Medicine, University/Institution: Yale University School of Medicine, Town/City: New Haven, State (US only): Connecticut, Country: USA

Frederick L. Altice, Department: Medicine, University/Institution: Yale University School of Medicine, Town/City: New Haven, State (US only): Connecticut, Country: USA. Department: Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases. University/Institution: Yale University School of Public Health, Town/City: New Haven, State (US only): Connecticut, Country: USA. Department: Centre of Excellence on Research in AIDS, University/Institution: University of Malaya, Town/City: Kuala Lumpur, State (US only):, Country: Malaysia

References

- Althoff A, Zelenev A, Meyer J, Fu J, Brown S, Vagenas P, et al. Correlates of Retention in HIV Care after Release from Jail: Results from a Multisite Study. AIDS and Behavior. 2012 Nov 18; doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0372-1. (Epub) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JR, Wood R, Bekker LG, Middelkoop K, Walensky RP. Projecting the benefits of antiretroviral therapy for HIV prevention: the impact of population mobility and linkage to care. J Infect Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2000;126(5):651–80. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae JW, Guyer W, Grimm K, Altice FL. Medication persistence in the treatment of HIV infection: a review of the literature and implications for future clinical care and research. AIDS. 2011;25(3):279–90. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328340feb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair-Merritt MH, Shea Crowne S, Thompson DA, Sibinga E, Trent M, Campbell J. Why Do Women Use Intimate Partner Violence?. A Systematic Review of Women’s Motivations’. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2010;11(4):178–189. doi: 10.1177/1524838010379003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JE, Swan SC, Allen CT, Sullivan TP, Snow DL. Why I Hit Him: Women’s Reasons for Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2009;18(7):672–697. doi: 10.1080/10926770903231783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JE, Swan SC, Woodbrown VD. Gender differences in intimate partner violence outcomes. Psychology of Violence; Psychology of Violence. 2012;2(1):42. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone-Lopez K, Kruttschnitt C, Macmillan R. Patterns of Intimate Partner Violence and Their Associations with Physical Health, Psychological Distress, and Substance Use. Public Health Reports (1974-) 2006;121(4):382–392. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen NE, Meyer JP, Avery AK, Draine J, Flanigan TP, Lincoln T, Spaulding AC, Springer SA, Altice FL. Adherence to HIV Treatment and Care Among Previously Homeless Jail Detainees. AIDS Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0080-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitsaz E, Meyer J, Krishnan A, Springer S, Marcus R, Zaller N, et al. Contribution of Substance Use Disorders on HIV Treatment Outcomes and Antiretroviral Medication Adherence Among HIV-infected Persons Entering Jail. AIDS and Behavior. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0506-0. (In Press.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Pendo M, Loughran E, Estes M, Katz M. Highly active antiretroviral therapy use and HIV transmission risk behaviors among individuals who are HIV infected and were recently released from jail. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(4):661–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.112656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Cook J, Grey D, Young M, Hanau L, Tien P, Levine A, Wilson T. Medically eligible women who do not use HAART: the importance of abuse, drug use, and race. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1147–51. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Deamant C, Barkan S, Richardson J, Young M, Holman S, Anastos K, Cohen J, Melnick S. Domestic violence and childhood sexual abuse in HIV-infected women and women at risk for HIV. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(4):560–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Hakim JG, Kumwenda J, Grinsztejn B, Pilotto JH, Godbole SV, Mehendale S, Chariyalertsak S, Santos BR, Mayer KH, Hoffman IF, Eshleman SH, Piwowar-Manning E, Wang L, Makhema J, Mills LA, de Bruyn G, Sanne I, Eron J, Gallant J, Havlir D, Swindells S, Ribaudo H, Elharrar V, Burns D, Taha TE, Nielsen-Saines K, Celentano D, Essex M, Fleming TR, Team HS. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R, Ellickson P, Orlando M, Klein D. Isolating the nexus of substance use, violence and sexual risk for HIV infection among young adults in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2005;9(1):73–87. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1683-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connecticut Department of Correction. July 1, 2012: Population Statistics. 2012 [online], available: http://www.ct.gov/doc/cwp/view.asp?a=1505&q=506086 [accessed.

- Das M, Chu PL, Santos GM, Scheer S, Vittinghoff E, McFarland W, Colfax GN. Decreases in community viral load are accompanied by reductions in new HIV infections in San Francisco. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Voux A, Spaulding AC, Beckwith C, Avery A, Williams C, Messina LC, Ball S, Altice FL. Early Identification of HIV: Empirical Support for Jail-Based Screening. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MR, McCauley HL, Phuengsamran D, Janyam S, Seage GR, Silverman JG. Violence victimisation, sexual risk and sexually transmitted infection symptoms among female sex workers in Thailand. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(3):236–40. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.037846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekeseredy W. Current Controversies on Defining Nonlethal Violence Against Women in Intimate Heterosexual Relationships: Empirical Implications. Violence Against Women. 2000;6:728–746. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health, Human Services. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1 Infected Adults and Adolescents 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Draine J, Ahuja D, Altice FL, Arriola KJ, Avery AK, Beckwith CG, Booker CA, Ferguson A, Figueroa H, Lincoln T, Ouellet LJ, Porterfield J, Spaulding AC, Tinsley MJ. Strategies to enhance linkages between care for HIV/AIDS in jail and community settings. AIDS Care. 2011;23(3):366–77. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.507738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004;363(9419):1415–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Wu E, Go H, Hill J. HIV and intimate partner violence among methadone-maintained women in New York City. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(1):171–83. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Herme M, Wickersham J, Zelenev A, Althoff A, Zaller N, Bazazi A, Avery A, Porterfield J, Jordan A, Simon-Levine D, Lyman M, Altice F. Understanding the Revolving Door: Individual and Structural-Level Predictors of Recidivism Among HIV-infected Jail Detainees. AIDS and Behavior. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0590-1. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The Spectrum of Engagement in HIV Care and its Relevance to Test-and-Treat Strategies for Prevention of HIV Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay J, Hardee K, Croce-Galis M, Kowalski S, Gutari C, Wingfield C. What Works for Women and Girls: Evidence for HIV/AIDS Interventions 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Gelberg L, Andersen R, Leake B. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1273–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano TP, Guzman D, Clark R, Charlebois ED, Bangsberg DR. Measuring adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a diverse population using a visual analogue scale. HIV Clin Trials. 2004;5(2):74–9. doi: 10.1310/JFXH-G3X2-EYM6-D6UG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M. Definitional Issues in Violence Against Women: Surveillance and Research from a Violence Research Perspective. Violence Against Women. 2000;6:747–783. [Google Scholar]

- Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse-Biber S. Qualitative Approaches to Mixed Methods Practice. Qualitative Inquiry. 2010;16(6):455–468. [Google Scholar]

- Huba G, Melchior L Group, S. o. t. M. and HRSA/HAB’s SPNS Cooperative Agreement Steering Committee. Module 46: Social Support Form. 1996. Nov 12, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):41–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. Conflict and control: gender symmetry and asymmetry in domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2006;12(11):1003–18. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. Domestic violence: it’s not about gender- or is it? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1126–30. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Cunningham-Williams R, Cottler L. A tripartite of HIV-risk for African American women: the intersection of drug use, violence, and depression. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70(2):169–75. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00345-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karandikar S, Próspero M. From client to pimp: male violence against female sex workers. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25(2):257–73. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A, Wickersham JA, Chitsaz E, Springer SA, Jordan AO, Zaller N, Altice FL. Post-Release Substance Abuse Outcomes Among HIV-Infected Jail Detainees: Results from a Multisite Study. AIDS Behav. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0362-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein B. Domestic violence in barriers to health care for HIV-positive women. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20(2):122–32. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieblich A, Tuval-Mashiach R, Zilber T. Narrative Research: Reading, Analysis, and Interpretation, Applied Social Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln T, Simon-Levine D, Smith J, Donenberg G, Springer S, Zaller N, Altice F, Moore K, Jordan A, Draine J, Desabrain M. Prevalence and Predictors of Psychiatric Distress Among HIV+ Jail Detainees at Enrollment in an Observational Study. AIDS and Behavior. doi: 10.1177/1078345815574566. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhorst T, Tajima E. Reconceptualizing and operationalizing context in survey research on intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(3):362–88. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez EJ, Jones DL, Villar-Loubet OM, Arheart KL, Weiss SM. Violence, coping, and consistent medication adherence in HIV-positive couples. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22(1):61–8. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Campbell J, Sweat M, Gielen A. The intersections of HIV and violence: directions for future research and interventions. 2000;50:459–478. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak L. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin: HIV in Prisons, 2007–2008. 2009 [online], available: http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail& [accessed.

- McLellan A, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr H, O’Brien C. New data from the Addiction Severity Index. Reliability and validity in three centers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173(7):412–23. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton HC, Sillito CL. The Role of Gender in Officially Reported Intimate Partner Abuse. J Interpers Violence. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0886260511424498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J, Chen N, Springer S. HIV Treatment in the Criminal Justice System: Critical Knowledge and Intervention Gaps. AIDS Research and Treatment. 2011;2011(680617) doi: 10.1155/2011/680617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J, Springer S, Altice F. Substance Abuse, Violence, and HIV in Women: A Literature Review of the SAVA Syndemic. Journal of Women’s Health. 2011;20(7):991–1006. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner JS. Treatment as prevention--a double hat-trick. Lancet. 2011;378(9787):208–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60821-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner JS, Lima VD, Barrios R, Yip B, Wood E, Kerr T, Shannon K, Harrigan PR, Hogg RS, Daly P, Kendall P. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based study. Lancet. 2010;376(9740):532–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60936-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States. 2010 (page 28) ‘ http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/strategy/pdf/nhas.pdf’, [online]

- Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Li K, Yip B, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT, Montaner JS, Hogg RS. Alcohol use and incarceration adversely affect HIV-1 RNA suppression among injection drug users starting antiretroviral therapy. J Urban Health. 2003;80(4):667–75. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi A, Blankenship K, Altice F. The association between history of violence and HIV risk: a cross-sectional study of HIV-negative incarcerated women in Connecticut. Womens Health Issues. 2007;17(4):210–6. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikoon SH, Cacciola JS, Carise D, Alterman AI, McLellan AT. Predicting DSM-IV dependence diagnoses from Addiction Severity Index composite scores. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer KR, Brant J, Gupta S, Thorpe J, Winstead-Derlega C, Pinkerton R, Laughon K, Ingersoll K, Dillingham R. Intimate partner violence: a predictor of worse HIV outcomes and engagement in care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(6):356–65. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y. Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, version 6.0. 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. AIDS and the health crisis of the U.S. urban poor; the perspective of critical medical anthropology. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(7):931–48. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17(4):423–41. doi: 10.1525/maq.2003.17.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer S, Chen S, Altice F. Improved HIV and substance abuse treatment outcomes for released HIV-infected prisoners: the impact of buprenorphine treatment. J Urban Health. 2010;87(4):592–602. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9438-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer S, Pesanti E, Hodges J, Macura T, Doros G, Altice F. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release to the community. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(12):1754–60. doi: 10.1086/421392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Qiu J, Saber-Tehrani AS, Altice FL. Retention on Buprenorphine Is Associated with High Levels of Maximal Viral Suppression among HIV-Infected Opioid Dependent Released Prisoners. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e38335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Spaulding AC, Meyer JP, Altice FL. Public health implications for adequate transitional care for HIV-infected prisoners: five essential components. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(5):469–79. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson B, Wohl D, Golin C, Tien H, Stewart P, Kaplan A. Effect of release from prison and re-incarceration on the viral loads of HIV-infected individuals. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(1):84–8. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman J, Campbell J, Celentano D. Sexual violence and HIV risk behaviors among a nationally representative sample of heterosexual American women: the importance of sexual coercion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(1):136–43. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b3a8cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basic of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory, Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Ashare RL, Jaquier V, Tennen H. Risk factors for alcohol-related problems among victims of partner violence. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47(6):673–85. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.658132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan SC, Gambone LJ, Caldwell JE, Sullivan TP, Snow DL. A review of research on women’s use of violence with male intimate partners. Violence Vict. 2008;23(3):301–14. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.3.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple JR, Weston R, Marshall LL. Physical and mental health outcomes of women in nonviolent, unilaterally violent, and mutually violent relationships. Violence & Victims. 2005;20(3):335–59. doi: 10.1891/vivi.20.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. National Institute of Justice, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1998 [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS Global Report on the AIDS Epidemic. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Walters K, Simoni J. Trauma, Substance Use, and HIV Risk Among American Indian Women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 1999;5(3):236–248. [Google Scholar]

- Weir B, O’Brien K, Bard R, Casciato C, Maher J, Dent C, Dougherty J, Stark M. Reducing HIV and Partner Violence Risk Among Women with Criminal Justice System Involvement: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Two Motivational Interviewing-based Interventions. AIDS Behav. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9422-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Haileyesus T, Swahn M, Saltzman LS. Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(5):941–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CT, Kim S, Meyer J, Spaulding A, Teixeira P, Avery A, Moore K, Altice F, Murphy-Swallow D, Simon D, Wickersham J, Ouellet LJ. Gender Differences in Baseline Health, Needs at Release, and Predictors of Care Engagement Among HIV-Positive Clients Leaving Jail. AIDS Behav. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0391-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood G, DiClemente R. The effects of an abusive primary partner on the condom use and sexual negotiation practices of African-American women. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(6):1016–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Mikhail I, Lang DL, McCree DH, Davies SL, Hardin JW, Hook EW, Saag M. A randomized controlled trial to reduce HIV transmission risk behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases among women living with HIV: The WiLLOW Program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(Suppl 2):S58–67. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140603.57478.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization and AIDS, T. G. C. o. W. a. Violence Against Women and HIV/AIDS: Critical Intersections. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization and UNAIDS. Addressing Violence Against Women and HIV/AIDS: What Works? 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Summary Report: WHO Multicountry study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wu E, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Sarfo B, Seewald R. Criminal Justice Involvement and Service Need among Men on Methadone who Have Perpetrated Intimate Partner Violence. J Crim Justice. 2010;38(4):835–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelenev A, Marcus R, Cruzado-Quinones J, Spaulding A, Desabrais M, Lincoln T, et al. Patterns of Homelessness and Implications for HIV Health after Release from Jail. AIDS and Behavior. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0472-6. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]