Abstract

Free-living amoebae feed on bacteria, fungi, and algae. However, some microorganisms have evolved to become resistant to these protists. These amoeba-resistant microorganisms include established pathogens, such as Cryptococcus neoformans, Legionella spp., Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Mycobacterium avium, Listeria monocytogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Francisella tularensis, and emerging pathogens, such as Bosea spp., Simkania negevensis, Parachlamydia acanthamoebae, and Legionella-like amoebal pathogens. Some of these amoeba-resistant bacteria (ARB) are lytic for their amoebal host, while others are considered endosymbionts, since a stable host-parasite ratio is maintained. Free-living amoebae represent an important reservoir of ARB and may, while encysted, protect the internalized bacteria from chlorine and other biocides. Free-living amoebae may act as a Trojan horse, bringing hidden ARB within the human “Troy,” and may produce vesicles filled with ARB, increasing their transmission potential. Free-living amoebae may also play a role in the selection of virulence traits and in adaptation to survival in macrophages. Thus, intra-amoebal growth was found to enhance virulence, and similar mechanisms seem to be implicated in the survival of ARB in response to both amoebae and macrophages. Moreover, free-living amoebae represent a useful tool for the culture of some intracellular bacteria and new bacterial species that might be potential emerging pathogens.

INTRODUCTION

The interest of microbiologists and clinicians in free-living amoebae has grown during the last decades, as a result of the demonstration of their pathogenicity (12, 164, 166, 171, 233, 242) as well as their role as reservoirs for Legionella pneumophila and other amoeba-resistant microorganisms (37, 246, 247).

Free-living amoebae have at least two developmental stages: the trophozoite, a vegetative feeding form, and the cyst, a resting form (Fig. 1). Some amoebae, such as Naegleria spp., have an additional flagellate stage. Others, such as Mayorella and Amoeba, are non-cyst-forming species (191). The trophozoite, the metabolically active stage, feeds on bacteria and multiplies by binary fission. Cysts generally have two layers, the ectocyst and the endocyst. A third layer, the mesocyst, is present in some species. The structure may explain why cysts are resistant to biocides used for disinfecting bronchoscopes (101) and contact lenses (31, 124, 250) as well as to chlorination and sterilization of hospital water systems (206, 214). Adverse pH, osmotic pressure, and temperature conditions cause amoebae to encyst. Encystment also occurs when food requirements are not fulfilled. Protozoa excyst again when environmental conditions become favorable.

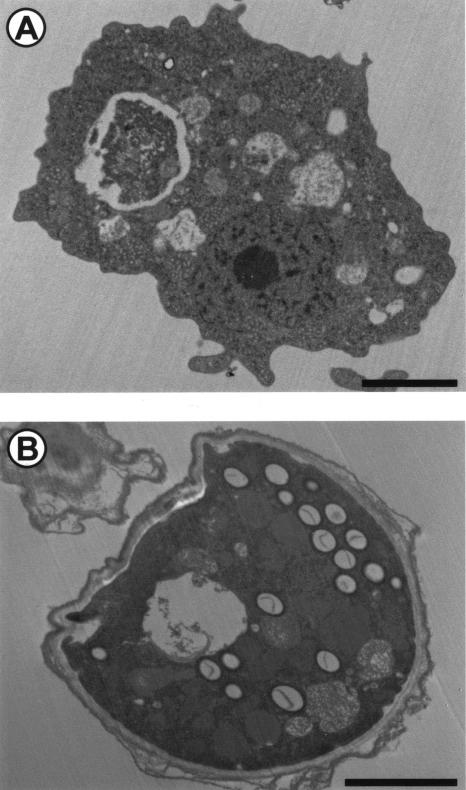

FIG. 1.

The two developmental stages of Hartmanella vermiformis. (A) The trophozoite, a vegetative feeding form; (B) the cyst, a resting form. Bar, 2 μm. Magnifications, ×5,325 (A) and ×6,675 (B).

Free-living amoebae are present worldwide (reviewed in reference 204) and have been isolated from soil (9, 10, 21, 188), water (11, 104, 108, 111, 144, 145), air (138, 202-205), and the nasal mucosa of human volunteers (7, 179). Their abundance and diversity in the environment are strongly dependent on season, temperature, moisture, precipitation, pH, and nutrient availability (9, 21, 204). In soil, free-living amoebae are more abundant at plant-soil interfaces since plants allow the growth of a variety of plant parasites (bacteria and fungi) on which amoebae feed (204). In water, species exhibiting a flagellar stage are able to swim while the others must attach to particulate matter suspended in water in order to feed (204). Thus, free-living amoebae often live on biofilms and at water-soil, water-air, and water-plant interfaces, among others (204). Biofilms such as those found on contact lenses and dental unit water lines can support the growth of free-living amoebae (14, 62). Free-living amoebae such as Hartmanella, Naegleria, and Acanthamoeba have also been recovered from drinking water (111, 181), cooling towers (13), natural thermal water (200, 201), swimming pools (59), hydrotherapy baths (60, 215), and hospital water networks (206). Several free-living amoebae were also recovered from marine water. Some are highly adapted to that saline environment; for example, Platyamoebae pseudovannellida may survive to a salinity grade of 150‰ (108). Acanthamoeba is the only pathogenic species isolated from marine water (11).

Free-living amoebae feed mainly on bacteria, fungi, and algae by phagocytosis, digestion occurs within phagolysosomes. Some microorganisms have evolved to become resistant to protists, since they are not internalized or are able to survive, grow, and exit free-living amoebae after internalization. These “amoeba-resistant microorganisms” (definition given in Table 1) include bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Among the amoeba-resistant bacteria (ARB) (Table 2), some were recovered by amoebal coculture (Bosea spp.) while others were identified within free-living amoebae isolated by amoebal enrichment (Procabacter acanthamoeba). Some are obligate intracellular bacteria (Coxiella burnetii), while others are facultative intracellular bacteria (Listeria monocytogenes) or might even be bacteria without a known eucaryotic-cell association (Burkholderia cepacia and Pseudomonas aeruginosa). Some are established human pathogens (Chlamydophila pneumoniae), while others are emerging pathogens (Simkania negevensis) or nonpathogenic species (Bradyrhizobium japonicum). Among the ARB, some (the Legionella-like amoebal pathogens [LLAP]) were named according to their cytopathogenicity (28) and represent the paradigm of bacteria able to lyse amoebae, while others (such as Parachlamydia acanthamoeba) were considered endosymbionts, since a stable host-parasite ratio was maintained (7). The term “endosymbionts,” defined by Büchner as “a regulated, harmonious cohabitation of two nonrelated partners, in which one of them lives in the body of the other” (38), refers to the intra-amoebal location of the bacteria [endo] and to its close relationship with the amoebae [symbiosis] (Table 1). In the present review, we generally use the term ARB instead of endosymbiont, since many bacteria able to resist destruction by free-living amoebae do not represent true endosymbionts and since even endosymbionts may be endosymbiotic or lytic while in a given amoeba, depending on environmental conditions (96).

TABLE 1.

Definitions

| Expression | Definition |

|---|---|

| Adaptation | Change in an organism resulting from selection pressure. |

| Amoeba-resistant microorganismsa | Microorganisms that have evolved to resist destruction by free-living amoebae, being neither internalized nor killed while within the amoeba. |

| Amoeba-resistant bacteriaa (ARB) | Bacteria that have evolved to resist destruction by free-living amoebae. |

| Character | Phenotypic traits possessed by an organism. |

| Criba | Literally, bed for a newborn baby. Here, it refers to free-living amoebae that act as a reservoir of new ARB and as a potent evolutionary incubator for adaptation to life in human macrophages. |

| Commensalism | Symbiosis in which one organism benefits from the association, with other being neither harmed nor benefited. |

| Endosymbiont | Symbiont that lives within another organism. |

| Endosymbiotic | Nonlytic behavior of an endosymbiont, although this might occur during only a short part of the life history. |

| Lytic | Ability to lyse the host cell, i.e., to rupture the host cell wall. |

| Mutualism | Symbiosis in which both organisms benefit from the association. |

| Parasite | An organism that benefits from the association with another organism while being harmful to the host. |

| Parasitism | Symbiosis in which one organism benefits from the association while the other is harmed. |

| Symbiont | An organism that lives in close contact with another living organism throughout a significant portion of its life history (167). |

| Symbiosis | “A phenomenon in which dissimilar organisms live together,” i.e. association of two organisms throughout a significant portion of their life history (167). |

| Symbiosis island | By analogy to “pathogenicity island,” a cluster of genes that confer symbiotic traits and may be transferred horizontally. |

| Trojan horse | Literally, a strategy used to invade the town of Troy. Here, it refers to the protozoal “horse” that may bring a hidden amoeba-resistant microorganism within the human “Troy,” protecting it from the first line human defenses. |

| Virulence | Degree of pathogenicity. |

| Virulence trait | Character that confers pathogenicity to an otherwise less pathogenic or nonpathogenic strain or organism. |

New expression first defined in the present paper.

TABLE 2.

ARB identified to datea

| ARB | Hostb | Life-style | Pathogenicity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α proteobacteriad | ||||

| Afipia felis | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Unknown | 157 |

| Afipia broomae | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Unknown | 155 |

| Bosea spp. | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Unknown | 154 |

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Unknown | 155 |

| Caedibacter acanthamoebae | Acanthamoebac | Facultative intracellular | Unknown | 114 |

| Ehrlichia-like organism | Saccamoebac | Obligate intracellular | Unknown | 182 |

| Mezorhizobium amorphae | Acanthamoeba | Extracellular | Unknown | 155 |

| Odyssella thelassonicensis | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Unknown | 27 |

| Paracaedibacter symbiosus | Acanthamoebac | Facultative intracellular | Unknown | 114 |

| Paracaedibacter acanthamoebae | Acanthamoebac | Facultative intracellular | Unknown | 114 |

| “Rasbo bacterium” | Acanthamoeba | Extracellular | Unknown | 150 |

| Rickettsia-like | Acanthamoeba | Obligate intracellular | Potential | 80 |

| β proteobacteriad | ||||

| Burkholderia cepacia | Acanthamoeba | Extracellular | Established | 148, 168 |

| Burkholdereria pseudomallei | Acanthamoeba | Extracellular | Established | 127 |

| Procabacter acanthamoeba | Acanthamoebac | Facultative intracellular | Unknown | 115 |

| Ralstonia pickettii | Acanthamoebac | Extracellular | Potential | 180 |

| γ proteobacteriad | ||||

| Coxiella burnetii | Acanthamoeba | Obligate intracellular | Established | 158 |

| Escherichia coli O157 | Acanthamoeba | Extracellular | Established | 17 |

| Francisella tularensis | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Established | 25 |

| Legionella pneumophila | Many species | Facultative intracellular | Established | 209 |

| Legionella anisa | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Potential | 156 |

| Legionella lytica (formerly Sarcobium lyticum) | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Potential | 66, 67 |

| L. fallonii | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Potential | 5 |

| L. rowbothamii | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Potential | 5 |

| L. drozanskii | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Potential | 5 |

| L. drancourtii | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Potential | 151 |

| Other LLAP | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Potential | 212 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Acanthamoebac | Extracellular | Established | 178 |

| Vibrio cholerae | Acanthamoeba, Naegleria | Extracellular | Established | 237 |

| ɛ proteobacteria | ||||

| Helicobacter pylori | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Established | 248 |

| Chlamydiaed | ||||

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae | Acanthamoeba | Obligate intracellular | Established | 71 |

| Neochlamydia hartmanellae | Hartmanellac | Obligate intracellular | Potential | 118 |

| Parachlamydia acanthamoebae | Acanthamoebac | Obligate intracellular | Potential | 7 |

| Simkania negevensis | Acanthamoeba | Obligate intracellular | Established | 133 |

| Flavobacteria | ||||

| Amoebophilus asiaticus | Acanthamoebac | Obligate intracellular | Unknown | 116 |

| Flavobacterium spp. | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Unknown | 116, 187 |

| Bacilli | ||||

| Listeria monocytogenes | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Established | 163 |

| Actinobacteriad | ||||

| Molibuncus curtisii | Acanthamoeba | Extracellular | Potential | 241 |

| Mycobacterium leprae | Acanthamoeba | Obligate intracellular | Established | 129 |

| Mycobacterium avium | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Established | 45, 141, 224 |

| Mycobacterium marinum | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Established | 45, 141 |

| Mycobacterium ulcerans | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Established | 141 |

| Mycobacterium simiae | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Potential | 141 |

| Mycobacterium phlei | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Potential | 141 |

| Mycobacterium fortuitum | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Potential | 45, 141 |

| Mycobacterium smegmatis | Acanthamoeba | Facultative intracellular | Potential | 141 |

Among the ARB, some are natural hosts of free-living amoebae (identified within free-living amoebae isolated by amoebal enrichment), some were recovered by amoebal coculture (i.e., using as the cell background free-living amoebae), and some were found to be resistant to a given amoebal “host” in vitro. Some are obligate intracellular bacteria, while others are facultative intracellular bacteria or extracellular bacteria. Some are established human pathogens, while other are emerging potential pathogens, or, until now, strictly environmental species. The list does not include Enterobacteriaceae that have been shown to resist destruction by free-living amoebae only under non-physiological conditions, such as chlorination (137).

Natural host, or grown by amoebal coculture.

Natural host.

Class, according to reference 86.

The study of parasites and symbionts of free-living amoebae is relatively new. Indeed, although the term “symbiosis” was already used in the late 18th century, it was only in 1956 that Drozanski described the presence of an intracellular microorganism that lysed amoebae (Table 3). Then, in 1975, Mara Proca-Ciobanu demonstrated the presence of endosymbionts within Acanthamoeba. Serological evidence that environmental endosymbionts of free-living amoebae might be human pathogens increased the interest in studying the interactions between free-living amoebae and amoeba-resistant microorganisms, studies facilitated by the availability of new molecular tools. The comprehension of these interactions should help in better understanding why some microorganisms evolved to become symbionts while others evolved to become pathogens.

TABLE 3.

History of the research on the endosymbionts of free-living amoebae and other amoeba-resistant microorganismsa

| Yr | Hypothesis or discovery | Microorganisms(s) | Author(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1856 | Presence of slender thread in Paramecium caudatum | Paramecium caudatum | Müller et al. |

| 1879 | Concept of symbiosis | Lichen | De Bary |

| 1954 | Lysis of a free-living amoeba due to bacterial infection | Free-living amoeba and bacteria | Drozanski et al. |

| 1975 | Presence of an endosymbiont within Acanthamoeba | Acanthamoeba and bacteria | Proca-Ciobanu et al. |

| 1978 | Role of free-living amoeba as a reservoir of pathogenic facultative intracellular bacteria | Acanthamoeba and mycobacteria | Krishnan-Prasad et al. |

| 1979 | Cryptococcus neoformans may survive within Acanthamoeba | Acanthamoeba and C. neoformans | Bunting |

| 1980 | Role of free-living amoebae in transmission (expelled vesicles) | Acanthamoeba and Legionella | Rowbotham |

| 1981 | Increased viability of enteroviruses adsorbed on Acanthamoeba: carrier role | Acanthamoeba and enteroviruses | Danes et al. |

| 1986 | Role of free-living amoebae in the selection of virulence traits (motility) | Acanthamoba and Legionella | Rowbotham |

| 1988 | Protection of internalized bacteria from chlorination | Enterobacteriaceae and Tetrahymena | King et al. |

| 1992 | Role of free-living amoeba in the susceptibility of the internalized bacteria to biocides | Acanthamoba and Legionella | Barker et al. |

| 1995 | Role of free-living amoeba on the antibiotic susceptibility of the internalized bacteria | Acanthamoba and Legionella | Barker et al. |

| 1996 | Role of free-living amoeba in the adaptation of the internalized bacteria to life within human macrophages | Acanthamoba and Legionella | Bozue et al. |

| 1997 | Environmental endosymbionts of free-living amoebae as emerging human pathogens | Parachlamydia acanthamoebae | Birtles et al. |

| 1998 | Horizontal transfer of clusters of genes contributing to symbiotic life: “symbiosis island” | Mesorhizobium loti | Sullivan |

| 1998 | Mitochondria originated by endosymbiosis: relationship between genomes of Rickettsia prowazekii and mitochondria | Rickettsia prowazekii | Andersson et al. |

| 2000 | First genome of a symbiont (of aphids) | Buchnera aphidicola | Tamas et al. |

| 2003 | Discovery of mimivirus, a giant virus naturally infecting free-living amoebae | Acanthamoba and mimivirus | La Scola et al. |

During the last 5 years, the increased availability of molecular tools and data has led to a better understanding of the relationships between free-living amoebae and amoeba-resistant microorganisms.

We intend to present first the importance of free-living amoebae as a tool for isolation of intracellular microorganisms. We then discuss the ARB identified to date (Table 2), along with other amoeba-resistant microorganisms (Cryptococcus neoformans and mimivirus). Finally, we describe the current knowledge of the roles played by free-living amoebae as reservoirs, as Trojan horses (definition given in Table 1), and in transmission (209, 211), selection of virulence traits (43, 44, 230), and adaptation of the microbes to macrophages (35, 84) (Fig. 2).

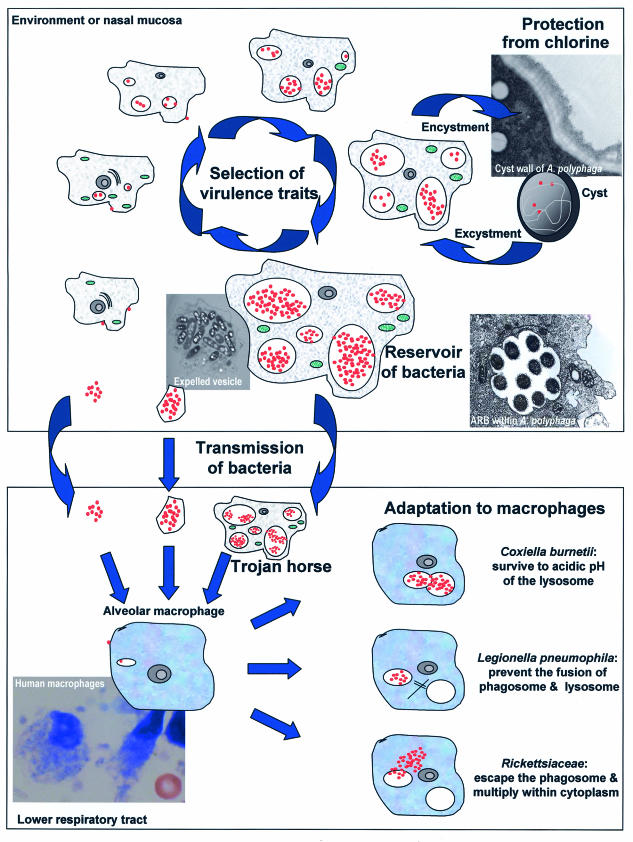

FIG.2.

The role of free-living amoebae as a reservoir of intracellular bacteria, as a Trojan horse, in the transmission of its bacterial host, in the selection of virulence traits, and in the adaptation of the bacteria to macrophages. The bacteria are shown in red, the amoebae are shown in grey, and their mitochondria are shown in green. (Top) Life cycle of amoeba-resistant bacteria within amoebae present in the environment or in the nasal mucosa. (Bottom) Amoeba-resistant microorganisms in the lower respiratory tract. During the cycle of intra-amoebal replication, bacteria select virulence traits. Moreover, amoebal vacuoles represent an important reservoir of bacteria, which may reach alveolar macrophages within amoebae, within expelled vesicles, or free. The strategy of resistance to macrophage microbicidal effectors varies from species to species and might have been acquired following exposure to environmental predators such as free-living amoebae.

FREE-LIVING AMOEBAE AS A TOOL FOR ISOLATION OF AMOEBA-RESISTANT INTRACELLULAR MICROORGANISMS

Several amoeba-resistant microorganisms, such as LLAP, Parachlamydiaceae, and Bradyrhizobiaceae, are fastidious intracellular bacteria and may be emerging pathogens (98, 170). This naturally led us and others to develop and use serological (29, 95, 170) and molecular (52) approaches to detect microbial antigens and nucleic acid sequences. However, the specificity of serological techniques and PCR is impaired by antigenic cross-reactivities and PCR contamination, respectively (61).

Culture remains the ultimate goal of pathogen identification, since it makes a microorganism available for further study (122). Culturing the microorganism is useful to reliably classify it, to test its ability to infect human macrophages, to determine its pathogenicity in animal models, to test its antibiotic susceptibility, to use it as antigen for serological testing, and to produce polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies.

Culture of Amoebae for Detecting ARB

The first approach to growing ARB is to directly inoculate a cell culture system in which cells are replaced by axenically grown free-living amoebae (see below). The second approach has two steps. After an initial enrichment of free-living amoebae present in the clinical samples, endosymbiont or intra-amoebal bacteria, if any, are liberated by lysis from their hosts and axenically grow in coculture with another strain of free-living amoebae. Amoebal lysis, which is one of the mechanisms used by the bacteria to exit the host before infecting another free-living amoeba, generally occurs spontaneously after a few hours (mimivirus) to a few days (Legionella spp.) of incubation. However, depending on different environmental factors, such as the incubation temperature, bacteria may remain trapped within the amoebae and the use of lytic solutions such as 2,3-hydroxy-1,4,-dithiolbutane (156) or dithiothreitol (210) may be needed.

The two-step strategy allowed the identification and culture of several ARB, such as Odyssella thessalonicensis (27), Parachlamydia acanthamoebae (7, 29), and several Legionella-like amoebal pathogens (LLAP) (82, 212). The procedures generally used for growing free-living amoebae were recently extensively reviewed in this journal (217) and are not presented here.

Amoebal coculture appeared useful for the recovery of L. pneumophila (210), L. anisa (156), and numerous α proteobacteria (150, 155). In addition, as amoebae graze on bacteria, amoebal coculture may help in selectively growing new ARB of unknown pathogenicity (150). Amoebal coculture could also be used to clean the samples from other more rapidly growing species that generally overwhelm the agar plates. Thus, using that technique, Rowbotham was able to grow L. pneumophila from human feces (213). Moreover, the amoebal coculture is a cell culture system that may be performed in the absence of antibiotics and is suitable for the recovery of new bacterial species of unknown antibiotic susceptibility. The main limitation of this technique is the decreased viability of amoebae such as Acanthamoeba and their encystment at high incubation temperature, which does not allow the recovery of bacteria requiring a temperature of ≥37°C. Hence, only 45% of A. polyphaga organisms are viable trophozoites after 4 days at 37°C, compared to 65 to 85% at 25 to 32°C (96).

Practical Use of Amoebae for ARB Culture

A species of free-living amoeba, such as A. polyphaga, is grown at 25 to 30°C (this species tends to encyst at 37°C) in cell culture flasks with peptone-yeast extract-glucose broth (PYG) (99, 210). When their concentration reaches about 105 to 106 amoebae per ml (4 to 6 days), the amoebae are harvested and washed twice in Page's modified Neff's amoeba saline (PAS) to remove most nutrients (99, 210). After the last centrifugation, the amoebae are resuspended in PAS at a concentration of about 5 × 105 amoebae per ml. One milliliter of this amoebal suspension is placed in each well of a 12-well microplate a few hours before the inoculation of the investigated sample. The relative numbers of amoebae and of the ARB potentially present are important, since if there are too few amoebae, they may be destroyed before a significant increase in the number of ARB is obtained (210), whereas if there are too many amoebae, they may encyst before the infection spreads to a large number of amoebae (210).

Depending on the nature of the sample and of the bacteria sought, the inoculation may be processed differently. Thus, to apply both the amoebal coculture and the two-step approach to a sample, it is advisable to first centrifuge it at low speed (about 180 × g for 10 min) and to use the supernatant for amoebal coculture and the pellet for amoebal enrichment. However, when using only one approach, it is better to inoculate all of the specimen to increase the sensitivity of the amoebal coculture. To disrupt the amoebal cells present in order to release the intracellular microbes, the samples may be treated with a lytic solution, such as 2,3-hydroxy-1,4,-dithiolbutane or dithiothreitol (156, 210), or with repeated sequential exposure to liquid nitrogen and boiling water, the “hot-ice” procedure. However, the advantages of these lytic procedures in terms of sensitivity have not been evaluated yet. Acid decontamination (210) and addition of both colistin (500 U/ml) and vancomycin (10 μg/ml) (150) may help to selectively grow Legionella spp. After inoculation, centrifugation of the microplates (2,900 × g) may accelerate the contact between the inoculum and the amoebal background and thus increase the sensitivity of the procedure.

The inoculated microplates are incubated at 30 to 35°C in a humidified atmosphere. The humidified atmosphere should prevent amoebal encystment. Too high a temperature will cause early amoebal encystment, whereas too low a temperature will be associated with less bacterial growth. Depending on the encystment rate, subcultures on fresh amoebae should be performed after about 4 to 7 days. Moreover, amoebal cocultures should be examined every day or at least every 2 days for the appearance of amoebal lysis that will suggest the presence of an amoeba-resistant microorganism and will necessitate subculture on fresh amoebae. At the time of subculture, each well should be screened for the presence of intra-amoebal bacteria. This screening is best achieved by gently shaking the microplates to suspend amoebae. Then, about 200 μl of the suspension is cytocentrifuged (147) and slides are stained with Gram, Gimenez (87), or Ziehl-Neelsen strain, depending on the suspected bacteria. We prefer Gimenez staining because most fastidious ARB are Gimenez positive and because fuchsin-stained bacteria are easily seen within the malachite green-stained amoebae (Fig. 3). The slide may also be prepared for immunofluorescence testing with the patients' serum as the primary antibody. The latter approach is valuable for detecting any microorganism against which a given patient has developed antibodies.

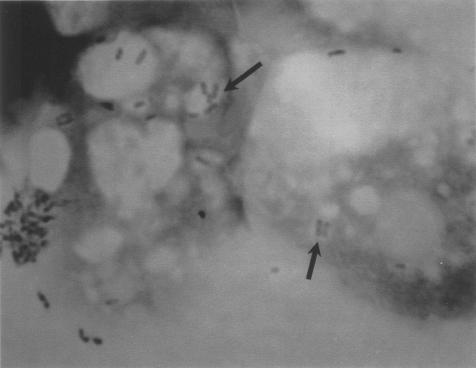

FIG. 3.

Gimenez-stained ARB. B. vestrisii is shown within A. polyphaga in a laboratory infection. Gimenez staining. Magnification, ×750.

When bacteria are seen, the sample is subcultured onto several agar media and onto amoebal microplates with and without antibiotics. The agar media should at least include buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE) agar (Legionella spp. and Francisella tularensis) and sheep blood agar (Mycobacterium spp., Flavobacteriaceae, and α proteobacteria) and should be incubated for prolonged periods. Subcultures on amoebal microplates are performed by inoculation of about 100 to 150 μl of the coculture on 1 ml of a fresh amoebal suspension. Preservation of the remaining sample at −80°C may be useful because some material is still available for additional subculture attempts. Subcultures on other cell lines may also be possible after filtration to eliminate the amoebae.

AMOEBA-RESISTANT MICROORGANISMS

Holosporaceae

Although endosymbionts related to the Rickettsiales had been observed since 1985 (79, 106), their taxonomic placement was only assigned later using 16S rRNA gene cloning, sequencing, and confirmation of the presence of the bacteria in situ by using fluorescent in situ hybridization (114). Thus, the cloning and sequencing of 16S rRNA of three endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba showed their relationship to symbionts of the ciliate Paramecium caudatum (Caedibacter caryophilus, Holospora obtusa, and H. elegans) and of the shrimp Penaeus vannamei (necrotizing hepatopancreatitis bacterium) (114). These symbionts were named Candidatus Caedibacter acanthamoebae, Candidatus Paracaedibacter acanthamoebae, and Candidatus Paracaedibacter symbiosus since they had 93.3, 87.5, and 86.5% 16S rRNA gene sequence homology to their closest relative, C. caryophilus, and only 85.8, 84.5, and 84% homology to H. obtusa (114). C. acanthamoebae, the endosymbiont of Acanthamoeba sp. strain HN-3, was shown to be present in both trophozoites and cysts (106). In trophozoites, it was present directly in the cytoplasm, where it divides by transversal binary fission (106). Attempts to culture the endosymbiont on different agar-based axenic media failed (106), suggesting that it is an obligate intracellular bacterium. Moreover, attempts to culture this bacterium in yolk sacs of embryonated eggs and to remove it from Acanthamoeba sp. strain HN-3 failed, strongly supporting its endosymbiontic nature (106).

Another member of the Holosporaceae, Candidatus Odyssella thessalonicensis, has been identified from an amoeba collected from the drip tray of the air conditioning system of a hospital in Greece (27). A recent phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rRNA genes of all these symbionts of Acanthamoeba, of the ciliate Paramecium caudatum (C. caryophilus, H. obtusa, and H. elegans) and of the shrimp Penaeus vannamei (NHP bacterium) showed that Candidatus O. thessalonicensis was phylogenetically close to Candidatus P. acanthamoebae (22). Interestingly, the branching of host and endosymbiont phylogenetic trees was congruent (22, 114, 117). This suggested that the ancestor of the C. caryophilus-related endosymbionts lived within an amoebal progenitor and coevolved with their hosts during the diversification of the different Acanthamoeba sublineages (22). If this is true, C. caryophilus will have only recently transferred to the ciliate Paramecium caudatum. The R-body represents a traditional taxonomic key criterion of the genus Caedibacter, confering killer traits (195, 216). The restricted presence of genetic mobile elements encoding the R-body in C. caryophilus and their absence in the endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba suggest that R-body-encoding genetic elements were acquired by C. caryophilus since it began to live within the ciliate P. caudatum (22).

Candidatus O. thessalonicensis was successfully grown on A. polyphaga, suggesting that amoebae may be an useful tool for culture of amoebal symbionts and for the recovery of new species (see below). The host range of O. thessalonicensis is narrow, being restricted to Acanthamoeba spp. Interestingly, incubation at 37 and 30°C resulted in amoebal lysis after 4 and 7 days, respectively, whereas at 22°C O. thessalonicensis appeared to form a stable host-endosymbiont equilibrium during a 3-week coincubation period (27). This might correspond to a modulation of the virulence at higher temperatures (see below). It is another example of endosymbionts that behave as lytic or symbiotic bacteria depending on environmental conditions (96).

The human pathogenicity of symbionts related to C. caryophilus remains to be determined.

Bradyrhizobiaceae

Afipia felis was the first species of the genus Afipia shown to resist destruction by free-living amoebae. It was first described as the agent of cat scratch disease (36), subsequently shown to be caused by Bartonella henselae and not by Afipia (130). Isolation of A. felis from human lymph nodes might be due to sample contamination with water. Indeed, A. felis is an environmental facultative intracellular bacterium that lives in water and may use the free-living amoebae as a reservoir (157). More importantly, it is protected from chlorination while located within an encysted amoeba (157).

A. broomae, A. massiliensis, and A. birgiae were also shown to resist destruction by free-living amoebae (150, 153, 155). A. massiliensis and A. birgiae were recovered from water by amoebal coculture (153). By analogy to what has been learned from experiments with Legionella, it has been proposed that Afipia spp. may be agents of nosocomial pneumonia (153), especially since they are common in hospital water networks (150). A pathogenic role for Afipia is further suggested by its uptake within murine macrophages in a nonendocytic compartment (162) and by its isolation from a patient with osteomyelitis (36). Although exposure of intensive care unit patients to Afipia spp. has been documented serologically (155), the role of Afipia spp. as etiological agents of nosocomial pneumonia remains to be demonstrated. Indeed, A. clevelandensis may cross-react with Brucella spp. and Yersinia enterolitica (64), demonstrating the low intergenus specificity of immunoflurescence testing for that clade.

The genus Bosea was described by Das et al (57) based on a single isolate, Bosea thiooxydans, recovered from agricultural field soil during a study of chemolithotrophic bacteria (56). Three additional species, B. eneae, B. vestrisii, and B. massiliensis (154), were recovered by amoebal coculture from hospital water supplies (150), demonstrating that some representatives of that genus are ARB commonly present in water. More importantly, they were associated with severe nosocomial pneumonia in ventilated intensive care unit patients (152).

Legionellaceae

Legionella pneumophila.

Inhalation of aerosols or microaspiration of contaminated water has been recognized as a source of legionellosis (227). After the initial description of an outbreak of severe respiratory disease occurring in Pennsylvania, which showed that person-to-person transmission was unlikely (77), subsequent reports of Legionella infections were repeatedly associated with contaminated water in both community-acquired (165, 229) and nosocomial (30, 90, 140, 142, 176) settings. The ecology of L. pneumophila was extensively studied and confirmed empirical observations of its predilection for growth in hot water tanks and its localization in sediment (228). Rowbotham described the ability of L. pneumophila to multiply intracellularly within protozoa (209) and suggested that free-living amoebae could be a reservoir for Legionella species (211). Since amoebae are common inhabitants of natural aquatic environments and water systems (143, 206) and since they have been found to be resistant to extreme temperature, pH, and osmolarity while encysted (reviewed in reference 204), this reservoir is important. It may explain the emergence of the disease after the increased exposure of humans to aerosolized water due to the use of new devices such as air conditioning systems, cooling towers, spas, showerheads, and grocery mist machines (107).

As long ago as 1980, Rowbotham suggested the role of amoebae, not only as a reservoir but also in the propagation and distribution of Legionella spp. in water systems and in the transmission of these bacteria to humans (209). He proposed that humans are infected not by inhaling free legionellae but by inhaling a vesicle or an amoeba filled with Legionella organisms (Fig. 4) (209). These vesicles filled with Legionella (8, 26) might contain as many as 104 bacteria (211). Since then, the relationship between L. pneumophila and free-living amoebae has been extensively studied, and the studies have confirmed that free-living amoebae are necessary for Legionella multiplication in water biofilms, although the bacteria may survive in a latent state in biofilms without amoebae (186).

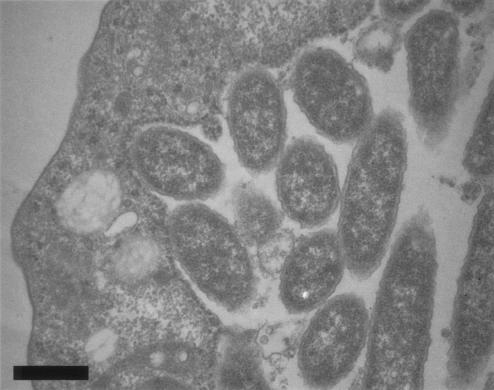

FIG. 4.

L. pneumophila within H. vermiformis in a laboratory infection. Magnification, ×16,500. Bar, 0.5 μm.

Although mature cysts are rarely infected with Legionella (103), with encystment probably being the main mechanism by which amoebae escape infection by Legionella spp. (211), it has been shown that encysted amoebae may protect L. pneumophila from the effect of chlorine (135). Not only do the amoebae protect the bacteria while encysted but also intra-amoebal growth confers resistance to chemical inactivation with 5-chloro-N-methylisothiazolone (16) and modifies the cellular fatty acid content of L. pneumophila, its production of lipopolysaccharide, and its surface protein expression (18). Moreover, vesicles filled with living Legionella organisms may be produced by exposure of Acanthamoeba spp. to biocides (26) and might also somehow protect the Legionella from the action of the biocides. All this may explain why elimination of Legionella from water systems is so difficult (110).

No case of person-to-person transmission of L. pneumophila has been reported, suggesting that genetic variants of Legionella that survived the strong selective pressure exerted by the alveolar macrophages are not maintained (230). Conversely, the virulence traits selected by intra-amoebal life will persist in the “species” genome. These virulence traits include motility (211), resistance to cold (16), invasive phenotype (44), resistance to antibiotics such as erythromycin (19), and resistance to biocides (16). Increased motility is associated with increased spread of the microorganism while extracellular. However, this virulence trait was not expected to be the result of intracellular growth within amoebae since neither motility nor flagella are required for intracellular growth (177, 196). This apparent paradox may be explained by a model of differential phenotypic expression of L. pneumophila depending on growth conditions (39). Thus, when growth conditions are optimal in host cells, L. pneumophila expresses functions to replicate maximally, and when amino acids become limiting, L. pneumophila produces factors to lyse the exhausted host cell, to survive osmotic stress, to spread in the environment, and to evade lysosomal degradation in the new intracellular niche (39).

These virulence traits expressed during the postexponential phase and selected over millions of years of replication within its protozoan host might explain the adaptation of L. pneumophila to life in human macrophages. Indeed, the life cycle of L. pneumophila within macrophages is very similar to that within amoebae (Table 4), and at the molecular level, some identical strategies are used to adhere to, enter, escape from, replicate in, and exit from both (see below).

TABLE 4.

Similarity of the mechanisms involved in the entry, traffic, replication, and exit of L. pneumophila with respect to both amoebae and macrophagesa

| Life cycle stage | Free-living amoebae

|

Macrophages

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Reference | Mechanism | Reference | |

| Entry | Coiling phagocytosis | 35 | Coiling phagocytosis | 120 |

| Traffic | No phagosome-lysosome fusion | 35 | No phagosome-lysosome fusion | 120 |

| Phagosome | Association with rough endoplasmic reticulum | 3 | Association with rough endoplasmic reticulum | 231 |

| Replication | Intraphagosomal | 209 | Intraphagosomal | 121 |

| Exit | Host cell lysis | 209 | Host cell lysis | 121 |

The similarity suggests that the amoebae might have been the “evolutionary crib” that led to the adaptation of L. pneumophila to life within human macrophages.

Legionella anisa and other Legionella spp.

Several other Legionella spp. have been reported to be agents of pneumonia, including L. anisa, L. micdadei, L. bozemanii, L. feeleii, L. jordanis, and L. maceachernii (73, 88, 160, 184, 232, 236, 238). Epidemiological investigations suggested that, as with L. pneumophila, water might be at the source of the outbreaks (32, 74).

The interactions between water, free-living amoebae, and Legionella spp. were better understood after the investigation of an outbreak of Pontiac fever. A total of 34 persons attending conferences at a hotel in California presented with Pontiac fever, a disease characterized by acute fever and upper respiratory tract illness (74). They were presumably infected by L. anisa since five of eight subjects exhibited a fourfold rise in antibody titers and since L. anisa and Hartmanella vermiformis were isolated from the decorative fountain in the hotel lobby (74, 75). In contrast to the wide amoebal host range of L. pneumophila (211), that strain of L. anisa grew only within H. vermiformis. It could not be grown within another protist, Tetrahymena pyriformis, or within human mononuclear cells (75). The narrow host range of L. anisa may explain its role as an agent of Pontiac fever (75), a milder disease than legionellosis, and may also explain why it was recognized mainly in immunocompromised patients (156, 235). We also showed the role of L. anisa as an agent of ventilator-acquired pneumonia, causing a cryptic epidemic due to contamination of intensive care unit tap water (152).

Legionella-like amoebal pathogens.

In 1956, Drozanski described an obligate intracellular parasite of free-living amoebae that causes lysis of the amoeba cells (66). Though initially named Sarcobium lyticum (67), this species was reclassified within the genus Legionella as L. lytica (112). In the meantime, Rowbotham reported the isolation of a Legionella-like bacterium, which he named Legionella-like amoebal pathogen 1 (LLAP-1), since, like L. pneumophila, it was able to induce amoebal lysis (211). Although LLAP-1 did not fluoresce with L. pneumophila, L. micdadei, and L. feeleii SG1 antisera and could not be grown on BCYE agar, it exhibited a fatty acid profile suggesting its placement within the genus Legionella (211). Phenotypic and genotypic characterization later allowed its classification as Legionella drozanskii (5). In 1991, another LLAP (LLAP-3) was identified within an amoeba enriched from the sputum of a patient with pneumonia (82). LLAP-3 was later shown to be a member of the species L. lytica (28).

Then, additional LLAP were recovered from environmental sources (28, 181). LLAP-9, LLAP-7FL (fluorescent), and LLAP-7NF (nonfluorescent) were also shown to be members of the species L. lytica (5), while LLAP-6, LLAP-10, and LLAP-12 represented three new species of Legionella: L. rowbothamii, L. fallonii, and L. drancourtii, respectively (5, 151).

Since the recovery of L. lytica (LLAP-3) from a patient with pneumonia who seroconverted against this strain and whose infection improved with macrolide therapy (82), there has been growing evidence that these emerging species of Legionella account for some of the pneumonias of unknown etiology (4, 174, 212; C. E. Benson, W. Drozanski, T. J. Rowbotham, I. Bialkowska, D. Losos, J. C. Butler, H. B. Lipman, J. F. Plouffe, and B. S. Fields, Abstr. 95th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1995, abstr. C-200, p. 35, 1995). Serological evidence of 10 L. lytica infections was obtained from screening more than 5,000 patients (212). More importantly, 4.3% of 255 patients hospitalized for a community-acquired pneumonia were seropositive for L. drancourtii (LLAP-4), compared to 0.4% of 511 healthy controls (p = 0.045).

The dichotomy between LLAP and other Legionella spp. may appear artificial, being based only on the fact that LLAP grow poorly or not at all on BCYE agar (28). However, it has helped to demonstrate that LLAP are emerging agents of pneumonia (4, 170, 212; Benson et al., Abstr. 95th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1995) and that BCYE is not suitable for in vitro cultivation and consequently for the diagnosis of LLAP-related pneumonia. Amoebal coculture is an important tool for diagnosing these emerging infections.

Pseudomonaceae

In vitro, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella aerogenes appeared to be a better nutrient source for amoebae than did Pseudomonas sp. (244), explaining why these species are generally preferred to Pseudomonas spp. for axenic cultures of Acanthamoeba and Naegleria spp. (193, 217). More importantly P. aeruginosa was shown to inhibit the growth of Acanthamoeba castellanii, especially in PYG and/or in the presence of an high bacterium-to-amoeba ratio (243). The presence of toxic pigments possibly explains these observations (243, 244). Qureshi et al. hypothethized that these pigments or amoebicidal enzymes produced by P. aeruginosa might explain the exclusive recovery of either Pseudomonas or Acanthamoeba from patients with keratitis (198). These apparent exclusive occurrences may also be due to amoebae grazing on Pseudomonas in contact lens disinfection solution initially contaminated with both amoebae and Pseudomonas, when Pseudomonas organisms were present in numbers too small to be inhibitory (243). Sometimes, encystment of the amoebae may occur or a fragile balance between Acanthamoeba and Pseudomonas may take place as suggested by the recovery of both species in contact lens system (63).

In nature, free-living amoebae probably also feed on Pseudomonas spp. that are widely distributed in water and that are present at low concentration. Their encounter may be facilitated by the better adherence of Pseudomonas (than of E. coli.) to Acanthamoeba (33). However, some Pseudomonas spp. evolved to become resistant to amoebae, as demonstrated by the isolation of Acanthamoeba naturally infected with P. aeruginosa (178). Hence, free-living amoebae might also play a role as a reservoir for some amoeba-resistant strains of Pseudomonas, similar to what has been shown for Legionella spp. This is important, given the role of P. aeruginosa as an agent of pneumonia (85). Whether there is a correlation between resistance to Acanthamoeba and pathogenicity remains to be determined. Models of virulence are discussed below.

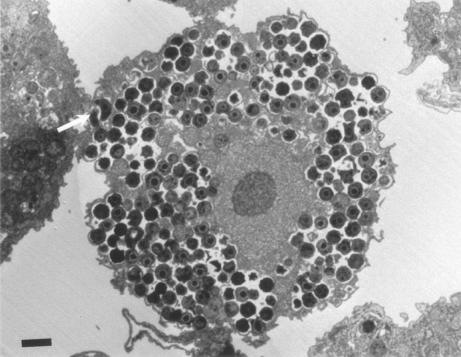

Parachlamydiaceae

The Parachlamydiaceae are small-coccoid bacteria that naturally infect free-living amoebae (Fig. 5). They have a Chlamydia-like cycle of replication, with elementary and reticulate bodies and a third developmental stage, the crescent body (arrow in Fig. 5), found only within that clade (99). Parachlamydiaceae form a sister taxon to the Chlamydiaceae, with 80 to 90% homology of rRNA genes (72). This family is composed of two genera, whose type strains are Parachlamydia acanthamoebae (7) and Neochlamydia hartmanellae (118), respectively.

FIG. 5.

A. polyphaga filled with P. acanthamoebae in a laboratory infection. Crescent bodies may be seen (arrow). Magnification, ×2,625. Bar, 1 μm.

Humans are exposed to Parachlamydiaceae, as demonstrated by the amplification of Parachlamydia DNA from nose and/or throat swabs (52, 190) and by the recovery of two strains of Parachlamydia from an amoeba isolated from nasal mucosa (7, 179).

More importantly, there is a growing body of evidence that Parachlamydia is an emerging pathogen of clinical relevance (98). The first hint was the identification of Parachlamydia sp. strain Hall coccus within an amoeba isolated from the source of an outbreak of humidifier fever in the United States (29) and a related serological study (29). In another serological study, fourfold-increased titers of antibodies against Parachlamydia in 2 of 500 patients with pneumonia was observed (Benson et al., Abstr. 95th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1995). More recently, 8 (2.2%) of 371 patients with community-acquired pneumonia were seropositive (titer, >1/50) for Parachlamydia, compared to 0 of 511 healthy subjects (170). The amplification of DNA of Parachlamydiaceae from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and sputum (50, 52) and from mononuclear cells of a patient with bronchitis (190) provided additional hints of a potential pathogenicity. Our own work provided evidence that Parachlamydia may be an agent of community-acquired pneumonia, at least in human immuno deficiency virus-infected patients with low CD4 counts (94), and may also be an agent of aspiration pneumonia, at least in severely head-injured trauma patients (95). Moreover, Parachlamydia enters and multiplies within human macrophages (97), another point in favor of its pathogenic role. In conclusion, human exposure to Parachlamydia could be a cause of upper respiratory tract infection, bronchitis, aspiration pneumonia, and community-acquired pneumonia.

The possible role of Parachlamydia in the pathogenesis of Kawasaki disease (170), a vasculitis associated with respiratory infections (23, 58), and in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (95, 190) merits further study.

Simkania negevensis is an agent of pneumonia in adults and of bronchiolitis in children (134, 159); it is phylogenetically related to the Chlamydiaceae and to the Parachlamydiaceae (72). Its ability to multiply within A. polyphaga and to survive within cysts has been documented (133), suggesting that free-living amoebae might also act as a reservoir and a selective environment ground for this clade. An extensive review has been recently published (78).

Chlamydophila pneumoniae may survive within Acanthamoeba castelanii but, in contrast to Parachlamydiaceae and Simkaniaceae, does not grow within this species of amoeba (71). The role of free-living amoebae as a reservoir for this established agent of lung infections remains to be tested. Whether additional species of Chlamydiaceae may resist destruction by free-living amoebae also remains to be established.

Mycobacteriaceae

Mycobacterium leprae was the first Mycobacterium sp. shown to survive in free-living amoebae; however, neither bacterial multiplication nor amoebal lysis occurred (129). Subsequently, in vitro experiments also showed that M. avium, M. marinum, M. ulcerans, M. simiae, and M. habane could enter free-living amoebae and that M. smegmatis, M. fortuitum, and M. phlei could be seen in large numbers in the amoebae, eventually inducing lysis (141). The interactions between M. avium and Acanthamoeba were subsequently studied and demonstrated that M. avium grown within amoebae were more virulent than those grown in broth medium. First, growth of M. avium in amoebae resulted in enhanced entry into amoebae, an intestinal epithelial cell line (HT-29), and macrophages (45). Second, growth of M. avium in amoebae enhanced its ability to colonize the intestine in a mouse model of infection and to replicate in the liver and the spleen (45). M. avium was also shown to survive within cyst walls of Acanthamoeba (224). Moreover, M. avium living within amoebae were more resistant to the antimicrobials usually prescribed as prophylaxis for M. avium disease in AIDS patients, including drugs such as rifabutin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin, than were M. avium residing within macrophages (183).

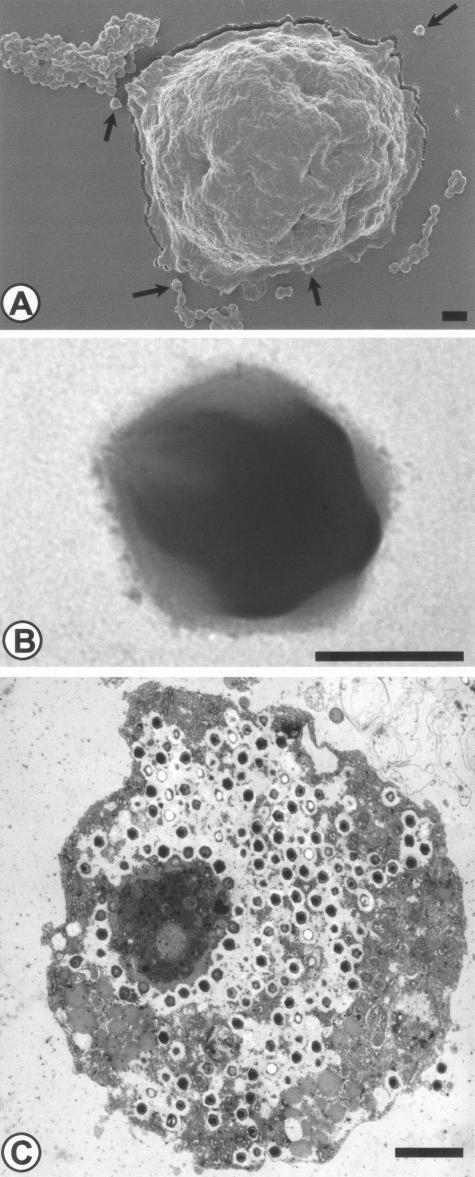

Mimivirus

In 1992, during a investigation of an outbreak of pneumonia, Rowbotham observed a gram-positive microorganism within a free-living amoeba recovered from the water of a cooling water in Bradford (England) by culture on nonnutrient agar (149). This nonfilterable organism was suspected to be a new bacterial endosymbiont. However, 16S rRNA gene amplification failed, despite repeated attempts. The microorganism was in fact a giant double-stranded DNA virus (Fig. 6). It was named mimivirus (for “microbe-mimicking virus”) (149). This virus, the largest virus described to date, consist of particles of 400 nm surrounded by an icosahedral capsid (Fig. 6B) (149). It is related to the Iridoviridae, Phycodnaviridae, and Poxviridae (149). These viruses are all nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses that probably derived from a common ancestor (128). The possible role of mimivirus as a human pathogen is not established yet.

FIG. 6.

Mimivirus, a giant virus naturally infecting free-living amoebae. (A) Mimivirus and A. polyphaga, as seen by scanning electron microscopy. Bar, 1 μm. (B) Mimivirus. Negative coloration, as seen by transmission electron microscopy. Bar, 200 nm. (C) Mimivirus within A. polyphaga in a laboratory infection, as seen by transmission electron microscopy. Bar, 2 μm. Magnifications, ×3,375 (A), ×33,750 (B), and 3,000 (C). Reprinted with permission from B. La Scola (A and C) and N. Aldrovandi (B).

Enterovirus

Enteroviruses are common causes of nonspecific febrile illnesses in children; they cause outbreaks of infection during the summer (54). Meningoencephalitis and aseptic meningitis are frequent (208). Gastrointestinal involvement may also be seen. Transmission from person to person proceeds through the fecal-oral route. These naked picornaviruses are widespread in marine water and may also be acquired by eating contaminated mollusks. Although labile, they may persist in free-flowing estuarine or marine waters for several months and in some cases during the winter months (161). Although their life span in water may be prolonged by the influence of estuarine sediments (147), it has been hypothesized that free-living amoeba may host these viruses. However, the role of amoebae as vectors for enteroviruses has not been confirmed (20, 55), and viruses were found only on amoeba surfaces (55). The adsorbed viruses persisted longer than free viruses, suggesting that amoebae might still play a role as carriers in the survival of enteroviruses (55) and hence explain the prolonged life span of enteroviruses in presence of sediments.

Other Endosymbionts of Free-Living Amoebae

In addition to Parachlamydiaceae and Holosporaceae, other partially characterized bacteria were naturally present within free-living amoebae and were considered endosymbionts. These endosymbionts are briefly described in this section. They include Rickettsia-like organisms, members of the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides phylum, and two species of β proteobacteria shown to naturally infect free-living amoebae. In addition, an Ehrlichia-like organism was discovered within the cytoplasm of one strain of Saccamoeba (182). This bacteria was, however, not characterized using molecular tools and could not be grown. Since Ehrlichia spp. have common epitopes (68, 199), the observed mild serological reactivity of this strain to E. canis antibodies (182) may be due to cross-reactivity. Consequently, although this organism is probably a member of the Rickettsiales, its true identity is unknown.

Rickettsia-like endosymbionts.

The presence of two endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba spp. phylogenetically related to members of the order Rickettsiales was demonstrated in 1999 by Fritsche et al. (80). These two Rickettsia-like strains were closely related, with 99.6% 16S rRNA sequence homology. They were more closely related to Rickettsia sibirica and R. typhi, with sequence similarities of 85.4% (80). Phylogenetic analysis confirmed that they share a common ancestor with Rickettsia spp. However, important sequence divergence was demonstrated by deep branching in the phylograms (80). Given the fact that Rickettsiales symbionts apparently have a narrow host range and that Rickettsia spp. may be considered commensal endosymbionts of ticks, this deep branching may correspond to the time of divergence of the protozoan and arthropods or to the time of their acquisition by ancestral ticks. The human pathogenicity of this Rickettsia-like lineage remains to be defined, as do its host range, prevalence, distribution, and interactions with free-living amoebae.

Members of the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides phylum.

The first member of the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides phylum identified within a free-living amoeba had a fatty acid profile indicating its affiliation with Cytophaga (187). Additional work showed its closer relationship to Flavobacterium succinicans (99% 16S rRNA gene sequence homology) (116). This Flavobacterium sp. and another strain related to Flavobacterium johnsoniae (98% 16S rRNA sequence homology), also identified within an Acanthamoeba organism, were able to grow on sheep blood agar, demonstrating a facultative intracellular lifestyle (116). Whether Flavobacterium spp. use the free-living amoebae as a reservoir and whether these bacteria play a role as human pathogens remains to be defined.

Another member of the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides phylum was identified within an Acanthamoeba organism isolated from lake sediment in Malaysia (116). In contrast to the Flavobacteriaceae, this strain, named Amoebophilus asiaticus, did not grow on agar-based media and was thus considered an obligate intracellular endosymbiont of Acanthamoeba (116). Of note, the host range of that symbiont was restricted to the host Acanthamoeba and attempts to infect other Acanthamoeba spp., Naegleria spp., Hartmanella vermiformis, Vahlkampfia ovis, Balamuthia mandrillaris, Willaertia magna, and Dictyostelium discoideum failed (116). This narrow host range and the fact that A. asiaticus is closely related to another endosymbiont of Acanthamoeba apparently isolated in Hungary (116) and, to a lesser degree, to Ixodes and Encarsia symbionts suggest that their common ancestor acquired or developed adaptative features which allow its descendants to successfully infect different eucaryotic lineages (116). The human pathogenicity of A. asiaticus also remains to be defined.

β proteobacteria naturally infecting free-living amoebae.

Ralstonia pickettii (180) and Procabacter acanthamoeba (115) are the only two species of β proteobacteria shown to naturally infect free-living amoebae. R. pickettii may act as an opportunistic pathogen (249). However, it is mainly incriminated as a contaminant of solutions used either for patient care (39, 146, 169) or for laboratory diagnosis (34), sometimes associated with pseudobacteremia (34).

Procabacter acanthamoeba, named in honor of Proca-Ciobanu, was identified within Acanthamoeba spp. recovered by amoebal enrichment of environmental samples and corneal scrapings (115). Its pathogenic role is largely unknown, but given its obligate intracellular lifestyle, infection may remain undiagnosed if axenic cultures alone are used.

Other Microorganisms Shown In Vitro To Resist Destruction by Free-Living Amoebae

Many microorganims have been reported to resist destruction by free-living amoebae in vitro. They include Burkholdereria cepacia (168), B. pseudomallei (148), Coxiella burnetii (158), Francisella tularensis (2, 25), Vibrio cholerae (237), Listeria monocytogenes (163), Helicobacter pylori (248), Mobiluncus curtisii (241), and Cryptococcus neoformans (223). Although E. coli is a common food source for the amoebae, a strain of E. coli has been reported to resist destruction by free-living amoebae, multiplying in coculture with A. polyphaga (224). Below, we present the available data on the in vitro interactions of these microorganims with free-living amoebae and briefly discuss their potential implications in term of ecology and public health.

Burkholderiaceae.

B. cepacia is associated with severe lung infections, especially in cystic fibrosis patients (76, 234) and, to a lesser extent, in intensive care unit patients. The role of free-living amoebae as a reservoir of B. cepacia has not been demonstrated. However, their role in the transmission of B. cepacia is possible, since expelled vesicles filled with B. cepacia bacteria have been reported (168).

B. pseudomallei causes melioidosis, an infection that may present as a fatal acute septicemia (239) or as subacute or chronic relapsing form (41). The fact that B. pseudomallei is resistant to amoebae (127) may explain its association with water (126) and its ability to survive within macrophages (132).

Coxiella burnetii

C. burnetii, an obligate intracellular bacterium, is the agent of Q fever. Phylogenetically related to Legionella spp. (245), it was also reported to resist destruction by free-living amoebae (158). Human infection occurs mainly by inhalation of infected aerosols in areas of livestock breeding, as demonstrated by the increased prevalence of Q fever in populations living downwind from breeding areas (240). The knowledge that C. burnetii is able to survive within free-living amoebae may shed some light on the epidemiology of that fastidious organism, suggesting that the bacteria expelled into the environment might persist for months within amoebae and might use them for transmission. It may also explain the resistance of C. burnetii to biocides (219) and its adaptation to life within phagolysosomes at acidic pH (172, 175).

Francisella tularensis.

Tularemia is a zoonotic disease caused by F. tularensis. It may be acquired by exposure to various mammals such as ground squirrels, rabbits, hares, voles, muskrats, and water rats or to ticks, flies, and mosquitos (70). There is evidence that F. tularensis can persist in water courses. Beavers and other water mammals, including lemming carcasses, might play the role of reservoir for the bacteria in water. However, the fact that free-living amoebae filled with F. tularensis can be observed, including subsequent lysis of the amoebae (2, 25), suggests that the protists might be an important water reservoir.

Enterobacteriaceae.

Enterobacteriaceae and several nonfermentative gram-negative bacteria (such as Stenotrophomonas maltophilia) are among the preferred nutrient sources of free-living amoebae. Thus, E. coli, E. aerogenes, and S. maltophilia appear to be better nutrient sources for amoebae than are Staphylococcus epidermidis, Serratia marcescens, and Pseudomonas spp. (243, 244). This explains why Enterobacter spp., Klebsiella spp., and E. coli are preferred for amoebal enrichment procedures (193, 217). Interestingly, viable E. coli organisms provide a higher yield of trophozoites than do nonviable ones (131). Conversely, E. coli is able to multiply in the presence of Acanthamoeba (224). However, unlike Legionella, which multiplies within the trophozoites, growth of E. coli is also possible when the bacteria are separated from Acanthamoeba by a semipermeable membrane (224). Although at the population or species level Enterobacteriaceae and Acanthamoeba spp. may be seen as mutualists, at the individual level the amoebae are better considered to be predators of the Enterobacteriaceae. The fact that the predator does not completely eliminate its prey is a generally accepted concept that may occur as a result of a variety of mechanisms (6). These mechanisms include interactions among predators (interference with their grazing activity), genetic feedback (mutants arise that are resistant to the predator or parasite), physical refuge (the presence of small pores of soil), switching to another prey, density dependence of attack by the predator, and increased replication of the prey that compensates for killing (6). Whether Enterobacteriaceae should be added to the growing list of ARB remains to be determined. Indeed, the amoeba-bacterium ratio and the viability and fitness of the amoebae should also be taken into account to validly determine the resistance of these species to free-living amoebae. Probably, some strains or some clones have a resistant phenotype, which may prove to be transient or persistent. Thus, the Vero cytotoxin-producing E. coli strains clearly represent ARB, since their population increased significantly in coculture (17).

Vibrionaceae.

Vibrio cholerae is a member of the Vibrionaceae that is reported to survive and multiply within A. polyphaga and N. gruberi (237). Its survival within cysts of N. gruber i suggests that free-living amoebae may protect the bacteria while encysted.

Listeria monocytogenes.

Since Listeria has been isolated from soil samples, sewage, and wastewater and since it resists destruction in human macrophages, Ly and Müller supposed that Listeria might be resistant to free-living amoebae (163). They confirmed their hypothesis by showing that L. monocytogenes multiplies within Acanthamoeba (163). However, after 1 month, most amoebal cells were encysted, preventing further Listeria survival (163).

Helicobacter pylori.

H. pylori may be present in water (113, 125, 173, 192), suggesting that free-living amoebae could play the role of reservoir for these fastidious microorganisms. This hypothesis is sustained by the demonstration that H. pylori is able to grow when cocultured with A. castellanii (248). More important, the viability of H. pylori could be maintained for up to 8 weeks in coculture with A. castellanii in the absence of microaerobic conditions (248). Additional studies are needed to determine the role played in vivo by free-living amoebae in the transmission of H. pylori.

Mobiluncus curtisii.

Only one species of anaerobe (Mobiluncus curtisii) has been reported to resist destruction by free-living amoebae (241). This obligate nonsporeforming anaerobic bacterium, causing vaginosis (218) and, more rarely, abcesseses (69) and bacteremia (91, 109), persisted for up to 4 to 6 weeks under aerobic conditions as a result of its internalization in Acanthamoeaba (241). Like H. pylori, M. curtisii may multiply aerobically when cocultured with free-living amoebae, while it requires otherwise strict atmospheric conditions for in vitro culture. This suggests that some strictly anaerobic bacteria are able to find refuge within amoebae. Further work is needed to determine the role of free-living amoebae as reservoirs of anaerobes. In particular, it may be interesting in the future to determine whether the vagina is colonized with free-living amoebae and whether such colonization may be associated with gynecological infections. The pathogenicity of M. curtisii, which is a commensal inhabitant of the vaginal flora and an established agent of vaginoses (218), might be due to a disequilibrium in the ratio of bacteria to amoebae.

Cryptococcus neoformans.

Cryptococcus neoformans is a soil fungus that causes life-threatening meningitis in immunocompromised patients. It is one of the best examples of common adaptations to both amoebae and human macrophages (see below), suggesting that certain aspects of cryptococcal human pathogenesis are derived from mechanisms used by fungi to survive within environmental amoebae (223). Indeed, nonvirulent, nonencapsulated strains do not survive in amoebae whereas virulent strains do.

Microorganisms Recovered Using Amoebal Coculture

Several other bacterial species were isolated by amoebal coculture, including Rhodobacter massiliensis, Azorhizobium spp., Bradyrhizobium japonicum, and Mezorhizobium amorphae (27, 100, 150, 155), showing that several clades have evolved to resist destruction by amoebae. These species are apparently nonpathogenic for humans.

FREE-LIVING AMOEBAE AS A RESERVOIR OF AMOEBA-RESISTANT MICROORGANISMS

The presence of amoebal vacuoles filled with thousands of Legionella organisms suggested that free-living amoebae may act as a reservoir for the internalized bacteria (211). A role of reservoir for other ARB such as Mycobacterium spp., L. monocytogenes, and F. tularensis was also proposed (25, 129, 141, 163), potentially explaining their presence in water (Francisella, nontuberculous mycobacteria) and the discrepancies between their fastidious nature and their widespread presence in the environment (Mycobacterium spp.). Indeed, free-living amoebae are widespread inhabitants of water, soil, and air (204).

By definition, a microorganism able to resist free-living amoebae is able to enter, multiply within, and exit its amoebal host (Fig. 2); thus, free-living amoebae may be considered to be reservoirs of any amoeba-resistant microorganism (246). The implications of such a reservoir in terms of ecology, epidemiology, and public health remain to be better defined.

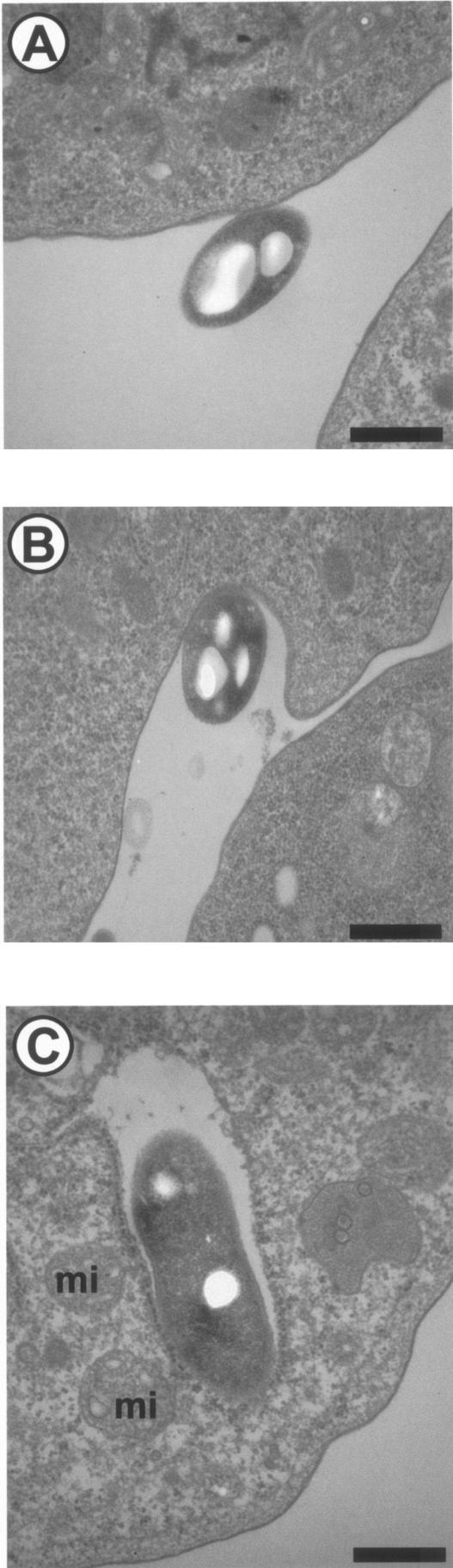

Since amoebae graze on bacteria, the entry of the bacteria by phagocytosis (Fig. 7) may be relatively easy, potentially being a passive process from the point of view of the ARB. This hypothesis is sustained by the fact that, in contrast to entry into macrophages, the entry of Legionella into amoebae is not inhibited by cytochalasin D (136). The intra-amoebal environment then favors the multiplication of a large variety of microorganisms (see above). Finally, exit from the amoebae may occur as expelled vesicles or by amoebal lysis (99, 211). Amoebal lysis is associated with the liberation of large numbers of bacteria. The mechanism of lysis has only been partially elucidated for L. pneumophila. Osmotic lysis of macrophages infected with L. pneumophila was shown to be mediated by the insertion of a pore into the plasma membrane (139). Gao and Abu Kwaik showed that this pore-forming activity of L. pneumophila was involved in the lysis of A. polyphaga (83). Thus, the wild-type bacterial strain was shown to cause the lysis of all the A. polyphaga cells within 48 h after infection, and all the intracellular bacteria are released into the culture medium (83). In contrast, all cells infected by the mutants remain intact, and the intracellular bacteria are “trapped” within A. polyphaga after the termination of intracellular replication (83). The icmT gene was shown to be essential for this pore formation-mediated lysis (185). For other ARB, the mechanism of lysis is unknown. Interestingly, the lysis was shown to be dependent on environmental conditions such as temperature. Indeed, we recently showed that Parachlamydia acanthamoebae is lytic for A. polyphaga at 32 to 37°C and endosymbiotic at 25 to 30°C (96). This suggests that A. polyphaga may serve as a reservoir for ARB at lower temperatures (for instance, when colonizing the nasal mucosa) and is liberated by lysis at higher temperatures (for instance when reaching the human lower respiratory tract) (Fig. 2). The role of free-living amoebae in resuscitating viable but nonculturable microorganisms should be further defined. Indeed, starvation conditions such as those present in low-nutrient-containing water or other stress such as exposure to antibiotics may induce some gram-negative bacteria to enter a viable but nonculturable state (40, 48, 49, 65). Up to now, a role for free-living amoeba in resuscitating viable but nonculturable bacteria has been demonstrated only for L. pneumophila (225).

FIG.7.

Phagocytosis of L. pneumophila by H. vermiformis in a laboratory infection. (A) Adherence; (B) uptake; (C) internalized bacteria. mi, mitochondria. Magnification, ×22,000. Bar, 0.5 μm.

Amoebae generally encyst to resist harsh or extreme conditions. They may also encyst to escape infection by the ARB (211); conversely, encystment of infected amoebae may be impaired (99). These observations explain why internalized bacteria are seen mainly within amoebae in the process of being encysted (8, 99). Furthermore, they might also explain the location of the bacteria within cysts walls (133, 224).

Cysts are highly resistant to extreme conditions of temperature, pH, and osmolarity (204). The survival of ARB within cysts has been especially well documented for Mycobacterium avium (224) and Simkania negevensis (133). After 79 days at 4°C, the infectivity of S. negevensis was still greater than 50% of the initial infectivity for Acanthamoeba, while in the absence of amoebal cysts and trophozoites, the bacteria did not survive for 12 days at 4°C (133). Hence, for the internalized microorganism, the cyst may represent more than a protection: it may play a role in the persistence of the microorganism in the environment.

Moreover, Acanthamoeba spp. cysts are highly resistant to biocides used for contact lens disinfection (31, 207, 250). Consequently, when encysted, free-living amoeba could protect the internalized bacteria (137). This could explain the observed increased resistance to chlorine of A. felis (157) and L. pneumophila (135) within A. polyphaga.

TRANSMISSION OF AMOEBA-RESISTANT MICROORGANISMS

Aerosolized water is probably one of the predominant vehicles for transmission of ARB. Thus, it is only when aerosolized water was produced by new devices such as air-conditioning system, showers, clinical respiration devices, and whirlpool baths that Legionella became a recognized human pathogen during large outbreaks. However, protozoa have probably hosted Legionella spp. for millions of years. The role of free-living amoebae in the transmission of Legionella and other bacteria to humans is not restricted to that of a ubiquitous reservoir. Indeed, free-living amoebae may increase transmission by acting as a vehicle carrying huge numbers of microorganisms. This carrier role is particularly obvious for enteroviruses (see above), which, although not entering the amoebal cells, may persist by adsorption onto free-living amoebae and spread by these vehicles (55). However, free-living amoebae may be more than simple vehicles; in addition, they may be “Trojan horses” for their host (15). Thus, the protozoal “horse” may bring a hidden amoeba-resistant microorganism within the human “Troy,” protecting it from the first line of human defenses (Table 1). Cirillo et al. definitively confirmed this hypothesis by demonstrating an increased colonization of the intestines of mice when viable amoebae were inoculated with M. avium (45), suggesting that the ability of M. avium to cross the intestinal epithelium was increased in presence of amoebae. The “Trojan horse” is also thought to protect the internalized bacteria from the first line of cell defenses in the respiratory tract (15).

Free-living amoebae may also increase the transmission of ARB by producing vesicles filled with bacteria (8, 26, 99, 168, 211). These vesicles, first described for L. pneumophila (8, 26, 211), may increase the transmission potential of Legionella spp. and may lead to underestimation of the risk by colony plate count methods (26). Vesicles have also been reported to contain Burkholderia cepacia (168) and Parachlamydia acanthamoebae (99).

FREE-LIVING AMOEBAE AS AN EVOLUTIONARY CRIB

Induction of Virulence Traits

The fact that free-living amoebae graze on bacteria has (i) ecological implications, explaining their diversity, number, and importance in biofilms, and (ii) diagnostic implications, allowing relatively easy recovery by culture on nonnutrient agar seeded with Enterobacter aerogenes or E. coli. Moreover, the fact that free-living amoebae graze on bacteria has had major evolutionary consequences, allowing some species to adapt to life in protozoa. These genetic adaptative changes include evolution by duplication of nonessential genes (123) and by the lateral acquisition of genes (189), that led to the expression of symbiotic or pathogenic phenotypes according to their impact on the host cell. Thus, amoebae represent a potent evolutionary crib and an important genetic reservoir for its internalized microbes (89). These reciprocal adaptive genetic changes took place over millions of years, leading the predator to refine its microbicidal machinery and leading the prey to develop a strategy enabling survival in amoebae. These strategies include increased size (that prevented engulfment) (92), increased multiplication rate (that prevented extinction of the species), colonization of new ecological niches, and, for the ARB, resistance to the microbicidal effectors of the amoebae. Due to the similarities of amoebal and macrophage microbicidal machinery, some strategies developed by ARB for resisting amoebae also helped them to survive in human macrophages when later, by chance, they encountered a human host (see above [Fig. 2]). Thus, selective pressures placed by amoebae on amoeba-resistant microorganisms such as C. neoformans appear to be critical in the maintenance of virulence (223). Hence, virulent capsular strains were phagocytozed by and replicated in A. castellanii, leading to amoebal death, while the nonvirulent acapsular strains were killed (223). The fact that free-living amoebae may promote the expression of virulence traits was also well demonstrated for L. pneumophila (44, 211) and M. avium (45) (see above).

The effect of amoebae on the virulence determinants of the amoeba-resistant microorganisms is not restricted to a selection of traits and a potent site for evolutionary change. In fact, the observed increased resistance to rifabutin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin of M. avium living within Acanthamoeba over that of strains residing within macrophages (183) may also be due to decreased uptake of antibiotics into amoebae, to an inactivation of the compound within amoebae, or to a change in the bacterial phenotype. The same may be true for the increased resistance observed in L. pneumophila grown within free-living amoebae to antibiotics such as erythromycin (19) and to biocides (16).

Models for testing virulence were developed by using Dictyostelium discoideum as a host (53, 105, 197, 221, 222). The model developed by Solomon et al. helps in studying the host factors that influence virulence of Legionella. Thus, mutants were examined for their effect on growth of L. pneumophila. The D. discoideum myo A/B double myosin I mutant, which shows a defect in amoebal mobility, and the coronin mutant, which shows defects in pinocytosis, phagocytosis, and amoebal mobility, were both more permissive than wild-type strains for intracellular growth of L. pneumophila (222). The validity of this model is supported by the fact that bacteria grew in D. discoideum within membrane-bound vesicles associated with rough endoplasmic reticulum (222), similar to what happens in macrophages (231), and that L. pneumophila dot/icm mutants unable to grow in macrophages and amoebae also did not grow in D. discoideum (222).

The virulence of P. aeruginosa was also tested by using amoebae. First, a plate assay was developed, in which D. discoideum was killed by virulent P. aeruginosa (197). If a mutation caused a particular strain of P. aeruginosa to be avirulent toward D. discoideum, then the amoeba fed on the avirulent strain and formed lysis plaques that were readily apparent after a few days. The avirulent mutants were impaired in two conserved virulence pathways: quorum-sensing-mediated virulence and type III secretion of cytotoxins (197). The second assay is similar, but Klebsiella was used as a marker of phagocytosis (53). When D. discoideum was added to the Klebsiella lawn, it fed on the bacteria, creating lysis plaques. The addition of a virulent P. aeruginosa strain inhibited the growth of D. discoideum, preventing the occurrence of plaques (53). P. aeruginosa mutants were tested for their ability to inhibit the growth of D. discoideum, showing that factors controlled by the rhl quorum-sensing system play a central role (53).

Adaptation to Macrophages

The selection of virulence traits may explain the observed adaptation to macrophages of most microbes able to survive and grow intracellularly in free-living amoebae, including such species as Legionella spp., L. monocytogenes, C. pneumoniae, M. avium, and C. burnetii. The adaptation of Legionella has been especially well studied, at both the cellular and molecular levels.