Abstract

Background

Patients with hepatic metastases from neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) benefit from an early diagnosis, which is crucial for the optimal therapy and management. Diagnostic procedures include morphological and functional imaging, identification of biomarkers, and biopsy.

Objective

The aim of six systematic reviews discussed in this study is to assess the predictive value of Ki67 index and other biomarkers, to compare the diagnostic accuracy of morphological and functional imaging, and to define the role of biopsy in the diagnosis and prediction of neuroendocrine tumor liver metastases.

Methods

An objective group of librarians will provide an electronic search strategy to examine the following databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE and The Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects). There will be no restriction concerning language and publication date. The qualitative and quantitative synthesis of the systematic review will be conducted with randomized controlled trials (RCT), prospective and retrospective comparative cohort studies, and case-control studies. Case series will be collected in a separate database and only used for descriptive purposes.

Results

This study is ongoing and presents a protocol of six systematic reviews to elucidate the role of histopathological and biochemical markers, biopsies of the primary tumor and the metastases as well as morphological and functional imaging modalities for the diagnosis and prediction of neuroendocrine liver metastases.

Conclusions

These systematic reviews will assess the value and accuracy of several diagnostic modalities in patients with NET liver metastases, and will provide a basis for the development of clinical practice guidelines.

Trial Registration

The systematic reviews have been prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42012002644; http://www.metaxis.com/prospero/full_doc.asp?RecordID=2644 (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6LzCLd5sF), CRD42012002647; http://www.metaxis.com/prospero/full_doc.asp?RecordID=2647 (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6LzCRnZnO), CRD42012002648; http://www.metaxis.com/prospero/full_doc.asp?RecordID=2648 (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6LzCVeuVR), CRD42012002649; http://www.metaxis.com/prospero/full_doc.asp?RecordID=2649 (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6LzCZzZWU), CRD42012002650; http://www.metaxis.com/prospero/full_doc.asp?RecordID=2650 (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6LzDPhGb8), CRD42012002651; http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42012002651#.UrMglPRDuVo (Archived by WebCite at http://www.webcitation.org/6LzClCNff).

Keywords: neuroendocrine tumors (NET), liver metastases, Ki67, mitotic count, genetic signatures, tumor cells, biochemical markers, morphological imaging, functional imaging, systematic review

Introduction

Background

Neuroendocrine Tumors

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) arise from the diffuse neuroendocrine system and therefore appear widespread over the whole body, especially in the gastrointestinal tract and the bronchopulmonary system [1,2]. NETs secreting hormones lead to a symptomatic disease. Nonsecreting NETs may occur initially asymptomatic or with delayed symptoms due to progressive increase in tumor mass [3,4]. Therefore, differences in functional behavior are the basis of a classification system categorizing functioning and nonfunctioning NETs [4]. Other reported classification systems are based on embryological origin or histopathological findings. In 2010, The World Health Organization (WHO) presented a new classification on the basis of tumor grading using histopathological criteria such as Ki67 index, mitotic count, and presence or absence of necrosis [5].

NETs is a relatively rare disease with an incidence of 1-3 per 100,000 [6,7]. The large range of reported incidence might be due to the fact that NETs often present initially asymptomatic and are often found accidentally or in autopsies [4]. Predominantly, NETs emerge sporadically (>90%) and are traditionally assigned to multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), neurofibromatosis-type 1 (NF1), and Von-Hippel-Lindau syndrome [1,4]. The clinical picture of NETs spans over different effects of excessive hormone secretion such as hypergastrinemia in Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome (ZES) with hyperchlorhydria, hyperinsulinemia in insulinoma, flushing and diarrhoea in the serotoninergic carcinoid syndrome. In the case of nonsecreting NETs, symptoms present due to the adverse effects of the growing primary tumor or metastases [8].

Biochemical Markers

Hormones secreted from NETs can be used as specific markers for NETs. Moreover, NETs express, store, and secrete characteristic neuronal proteins such as acid glycoprotein chromogranin A (a component of the membrane neurosecretory granula), neuron-specific-enolase (NSE), and synaptophysin [3,9]. These proteins derived from neuronal structures could serve as markers and are even positive in nonfunctioning NETs [1,3]. Since more than one half of NETs are nonsecreting, these proteins play a crucial role [4]. Assessment of different biochemical markers depends on various parameters, such as threshold cut-off level, detecting method of urine, serum or plasma as well as location of the primary tumor or metastases and extension of the disease. Due to the large variety and number of evaluation parameters, it is difficult to compare the studies [10,11].

Histopathological Prognostic Markers

Ki67 is a monoclonal antibody, which was introduced in 1984 by Gerdes et al [11]. It detects a growth rate depending on the nuclear antigen Ki67 which is only expressed during active cell cycle phases (S, G2, and M-phase). Ki67 is completely absent during the resting phase G0. Therefore, cell proliferation is assessed by the immunohistologic presence of Ki67 positive cells per area in stained tissue blocks [11].

For various human neoplasms such as breast, lung, and solid cancers, Ki67 proliferation index has been successfully established as a predictive marker [12,13]. The higher the cell proliferation, the greater is the probability for metastases resulting in decreased patient survival. The primary location of NETs metastases is the liver [14-17]. The occurrence of hepatic metastases is a prognostic factor which strongly influences the survival of patients suffering from NET [18-20].

Genetic Signatures and the Presence of Circulating Tumor Cells

To stratify outcomes in patients undergoing resection of primary NET, a simple scoring system using tumor size, histological grade, nodal metastases, and resection margin status has been introduced [21]. Nevertheless, current classification systems for NETs other than positron emission tomography (PET) fail to predict the clinical course and the response to treatment [22]. The discrepancy might be explained either by an insufficient accuracy of these classification systems or an adaptive NET behavior [23]. These limitations of the pathologic classifications have led to the investigation of other predictive parameters based on genetic signatures as well as the presence of circulating tumor cells [24,25]. These novel predictive parameters have to be included in the classification systems in order to account for the biological behavior, the likelihood for developing metastases as well as the choice of treatment [25].

Imaging Methods

Imaging methods are used to diagnose neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and their metastases [26]. Beside conventional morphologic imaging methods, functional imaging modalities have been introduced in order to improve accuracy in detecting NETs and liver metastases [27]. Functional imaging methods have their limitations with a great impact on a possible therapeutic strategy, where differentiation between pancreatic foci and neighbouring lymph nodes as well as exact demarcation of a suspicious focus to a liver segment is crucial [28]. Advanced techniques such as contrast-enhanced ultrasound may assist in earlier detection of hepatic metastases, and could therefore offer a wider therapeutic range either surgically, with radiofrequency thermal ablation, or with systemic chemotherapy [29].

Liver Biopsy

The most common site of neuroendocrine tumor (NET) metastases is the liver [30]. The presence of hepatic metastases is a strong prognostic factor for the survival of patients with NETs, regardless of the primary tumor site [31]. Histologic examination is the most sensitive diagnostic method and forms the basis for treatment decisions [32]. However, the value of the biopsy for treatment decision making involving primary NETs and their liver metastases is not well defined [33,34].

Objective

The aim of these six systematic reviews is to assess the predictive value of Ki67 index and other biomarkers, to compare the diagnostic accuracy of morphological and functional imaging, and to define the role of biopsy in the diagnosis and prediction of neuroendocrine tumor liver metastases.

Methods

Systematic Reviews

Our reviews were prospectively registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with the following IDs: CRD42012002644, CRD42012002647, CRD42012002648, CRD42012002649, CRD42012002650, CRD42012002651.

The above six systematic reviews dealing with the diagnosis and prediction of neuroendocrine liver metastases attempt to address the following questions in Table 1.

Table 1.

Scientific questions on diagnosis and prediction of neuroendocrine liver metastases.

| Questions | Sub-questions | |

| Should patients with low Ki67 index be followed up for the detection of liver metastases? | ||

|

|

In patients with a primary NET, what is the predictive value of Ki67 index, mitotic count, or tumor grading, obtained from the primary tumor, in predicting the development of liver metastases? | |

| Should genetic signatures and the presence of circulating tumor cells be used in the prediction of liver metastases and to inform treatment decisions? | ||

|

|

In patients with a primary NET, what is the predictive value of genetic signatures obtained from the primary tumor, in predicting the development of liver metastases? | |

| In patients with a primary NET, what is the predictive value of circulating tumor cells obtained from the primary tumor, in predicting the development of liver metastases? | ||

| In patients with a primary NET, should genetic signatures be used in the treatment decision (surgery, locally ablative techniques, liver-directed techniques, peptide receptor radionuclide treatment, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and biotherapy)? | ||

| In patients with a primary NET, should the presence of circulating tumor cells be used in the treatment decision (surgery, locally ablative techniques, liver-directed techniques, peptide receptor radionuclide treatment, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and biotherapy)? | ||

| Which biochemical markers should be used for detection and post treatment follow-up of liver metastases? | ||

|

|

In patients with a primary NET, what is the diagnostic accuracy of the available biochemical markers (eg, chromogranin A and B, Serotonin, neuron-specific-enolase (NSE), tumor specific hormones) in detecting liver metastases? | |

| In patients receiving a liver resection, what is the diagnostic accuracy of the available biochemical markers (eg, chromogranin A and B, serotonin, NSE, tumor specific hormones) obtained during follow-up, in detecting recurrent disease or disease progression? | ||

| Which morphological imaging modality should be used to assess resectability of liver metastases with a curative intent? | ||

|

|

In patients with NET liver metastases, what is the diagnostic accuracy of different morphological imaging modalities (US, CT, MRI) in identifying liver lesions and extrahepatic disease? | |

| In patients with NET liver metastases, what is the diagnostic accuracy of different morphological imaging modalities (US, CT, 3D-CT, MRI) in detecting vascular and biliary invasion, in order to assess resectability (R0/R1)? | ||

| Which functional imaging modality should be used to assess resectability of liver metastases with a curative intent? | ||

|

|

In patients with NET liver metastases, what is the diagnostic accuracy of different functional imaging modalities (octreoscan, DOTA-SSTR-PET/CT, F-18 FDG-PET/CT, DOPA PET, etc) in identifying liver lesions? | |

| In patients with NET liver metastases, what is the diagnostic accuracy of different functional imaging modalities (octreoscan, DOTA-SSTR-PET/CT, F-18 FDG-PET/CT, DOPA PET, other) in detecting extra-hepatic disease? | ||

| Do we need a biopsy of both the primary and liver metastases for the treatment decision of liver metastases? | ||

|

|

In patients with a primary NET and synchronous liver metastases, what is the agreement between the biopsy of the primary and the liver metastases with regards to tumor grading? | |

| In patients with metachronous liver metastases, what is the agreement between the biopsy of the primary and the liver metastases with regards to tumor grading? | ||

| In patients with liver metastases, what is the agreement between single vs multiple liver biopsies with regards to tumor grading? | ||

| In patients with NET liver metastases, do we need additional biopsies from normal parenchyma to detect micrometastases? | ||

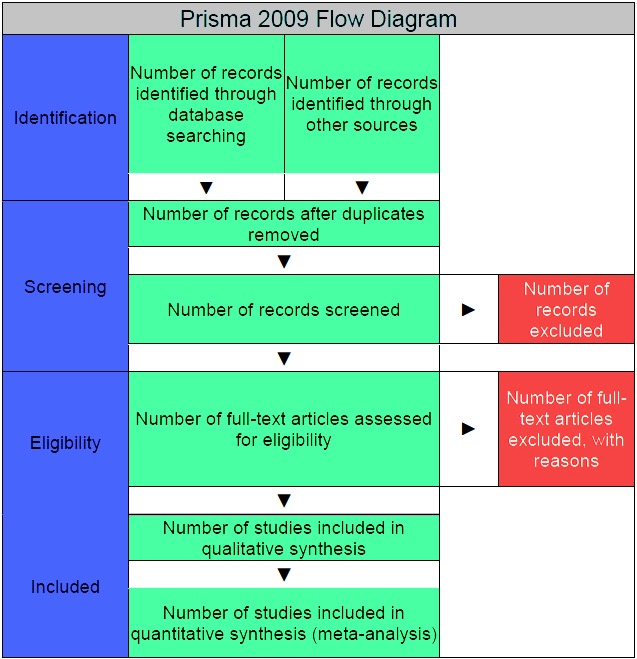

The systematic review inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Tables 2-7. There were no restrictions in the literature search regarding the publication language or by publication date. The following study types were included: randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective and retrospective comparative cohort and case-control studies and case series (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Eligibility criteria for review on Ki67 index.

| Study characteristics | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Participants/population | Patients with primary neuroendocrine tumors who were assessed with Ki67 index, mitotic count or tumor grading | Patients over the age of 18 years old |

| Tumor markers | Tumor markers (Ki67 index, mitotic count or tumor grading) must be obtained from the primary tumor | Studies that do not report the predictive value of Ki67 index, mitotic count or tumor grading |

| Study design | Follow-up studies for the development of liver metastases | No follow-up studies for the development of liver metastases |

| Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) | ||

| Prospective and retrospective comparative cohort studies | Case reports | |

| Noncomparative cohort studies | ||

| Case-control studies | Reviews | |

| Case series |

Table 7.

Eligibility criteria for biopsy of primary and liver metastases.

| Study characteristic | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Patient population | Patients with primary neuroendocrine tumors and/or NET liver metastases | Children or adolescents (under the age of 18 years old) |

| Patients who underwent a biopsy of the primary and liver metastasis |

|

|

| Patients who underwent multiple biopsies of the liver metastases and/or healthy parenchyma | ||

| Test of interest | Biopsy of primary NET and/or NET liver metastases | Studies that do not report histo-pathological biopsy results |

| Study design | Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) | Case reports |

| Prospective and retrospective comparative cohort studies | ||

| Noncomparative cohort studies | Case-control studies |

Reviews |

| Case series | ||

| Cross-sectional and/or cohort studies |

Figure 1.

Prisma 2009 Flow Diagram.

Table 3.

Eligibility criteria review on genetic signatures and the presence of circulating tumor cells.

| Study characteristics | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Participants/population | Patients with primary neuroendocrine tumors | Children or adolescents (under the age of 18 years old). |

| Patients whose genetic signatures of the primary tumor have been tested or those who have been tested for presence of circulating tumor cells | Animal studies | |

| Patients with tested genetic signatures only of the metastases | ||

| Patients with 18 years of age or older | ||

| Test of interest | Gene expression testing of the primary tumor | Gene expression testing of the metastases |

| Test for circulating tumor cells | ||

| Reference standard | The reference standard test will be the presence or absence of liver metastases during follow-up (imaging or histopathology) by presence or absence of a genetic signature or circulating tumor cells |

|

| Study design | Cross-sectional studies of any type | Case reports |

| Cohort studies | ||

| Reporting |

|

Studies that do not report any predictive value |

Table 4.

Eligibility criteria for review on biochemical markers.

| Study characteristic | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Participants/population | Patients with primary neuroendocrine tumors and patients who underwent surgery for primary liver tumors with a curative intent and were followed up for the detection of potential liver metastases | Studies that do not report the assessment of resectability (second scientific question) |

| Patients over the age of 18 years old | Children or adolescents (under the age of 18 years) | |

| Studies that do not report the diagnostic accuracy (first scientific question) | ||

| Test of interest | Tests of biochemical markers detecting liver metastases, and for the post treatment follow-up of liver metastases: 1) Chromogranin A 2) Chromogranin B 3) Serotonin 4) Tumor specific hormones (Glucose, Insulin, Proinsulin, C-Peptide, Gastrin, Glucagon, Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide, Somatostatin, Neuron Specific Enolase) |

|

| Reference standard | The different biochemical markers Chromogranin A and B, Serotonin and tumor specific hormones will be compared | |

| Control | The histopathological diagnosis of the resected specimen or a tumor biopsy will be considered as the reference standard | |

| Study design | Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) | |

| Prospective and retrospective comparative cohort studies | ||

| noncomparative cohort studies | ||

| Case-control studies | ||

| Case series | ||

| Primary outcome | Diagnostic accuracy of the different biochemical markers (sensitivity and specificity) | |

| Secondary outcome | Additional diagnostic accuracy measures of the different biochemical markers (accuracy, positive and negative predictive values, positive and negative diagnostic likelihood ratios, etc) |

Table 6.

Eligibility criteria for review on functional imaging modality.

| Study characteristic | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Patient population | Patients with NET | Children or adolescents (under the age of 18 years) |

| Patients with liver metastases | ||

| Test of interest | SPECTa | |

| SPECT/CTb | ||

| SRSc | ||

| 123I-MIBG-Scintigraphyd | ||

| 18F-FDA-PETe | ||

| 18F-FDG-PETf | ||

| 18F-DOPA PET/CTg | ||

| PET/CTh | ||

| PET/MRIi | ||

| 111In-SRSj | ||

| 123I-SRSk | ||

| Study design | Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) | Case reports |

| Prospective and retrospective comparative cohort studies | ||

| Noncomparative cohort studies | ||

| Case-control studies | ||

| Case series | Reviews | |

| Reporting |

|

Studies that do not report the diagnostic accuracy |

| Studies that do not report the assessment of resectability |

aSingle photon emission computed tomography

bHybrid method of single photon emission computed tomography and computed tomography

cSomatostatin receptor scintigraphy

d(123) Iodine-metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy

e(18) Fluoro-dopamine positron emission tomography

f(18) Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography

g (18) Fluoro-L-dihydroxyphenylalanine positron emission tomography

hHybrid method of positron emission tomography and computed tomography

i Hybrid method of positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging

j(111) Indium-somatostatin receptor scintigraphy

k(123) Iodine-somatostatin receptor scintigraphy

Search

Librarians of the Medical Library Careum, University of Zurich, Switzerland, develop the electronic search strategy to query databases and to identify all potentially relevant articles. The following databases will be searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE and The Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects). The investigators will be provided with an Endnote file containing all identified titles and, if available, the corresponding abstracts. Additional articles will be retrieved through manual search or scanning of reference lists. Titles and/or abstracts of all identified records will be independently screened by two review team members to ascertain their relevance and to identify studies that potentially meet the inclusion criteria outlined in Tables 2-5. The full text of each of these potentially relevant studies will then be assessed for eligibility. Any disagreement will be resolved through discussion with a third review team member. A predefined protocol will be used to extract data from the included studies for assessment of study quality and evidence synthesis.

Table 5.

Eligibility criteria for review on morphological imaging modality.

| Study characteristic | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Patient population | Patients with liver metastases from neuroendocrine tumors | Children or adolescents (under the age of 18 years) |

| Patients who underwent liver transplantation or palliative liver resection or nonsurgical treatment (peptide receptor radionuclide treatment, chemotherapy, biotherapy) |

|

|

| Study design | Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) | Case reports |

| Prospective and retrospective comparative cohort studies | Editorials | |

| Noncomparative cohort studies | Reviews | |

| Case-control studies | ||

| Case series | ||

| Reporting |

|

Studies that do not report the diagnostic accuracy (first scientific question) |

| Studies that do not report the assessment of resectability (second scientific question) | ||

| Test of interest | Computed tomography (CT) |

|

| Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | ||

| Ultrasound scanning |

Data Extraction

The parameters for data extraction will be the following: first author’s name, publication year, answering scientific questions, study design, total number of patients, number of patients in the study group, and number of patients in the comparison group. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) will be used to grade the quality (level) of evidence and the strength of recommendations [35].

A narrative synthesis of the findings from studies included will be provided. A quantitative synthesis will be used for studies that are sufficiently homogenous from a clinical (comparability of populations, interventions and outcomes) and from a statistical perspective (heterogeneity, eg, I2<50%). We anticipate that there will be a limited scope for meta-analysis despite a relatively large number of studies due to the different outcome measurements of the existing trials (ie, since such tumors are rare). However, results from studies using the same type of intervention and comparator, with the same outcome and measurements will be pooled using a random-effects meta-analysis. In addition risk ratios for binary outcomes, 95% confidence intervals and two- sided P values will be calculated for each outcome.

Discussion

There are several modalities for the diagnosis and prediction of neuroendocrine liver metastases; however, there is a lack of consensual data on the subject. The six systematic reviews described in this protocol will elucidate the role and compare histopathological prognostic and biochemical markers, biopsies of the primary neuroendocrine tumor and NET liver metastases, morphological and functional imaging modalities. They will help to define clinical guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Martina Gosteli and her colleagues for their excellent support.

Abbreviations

- CT

computed tomography

- E-AHPBA

European-African Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NET

neuroendocrine tumors

- PET

positron emission tomography

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- US

ultrasound scanning

- WHO

World Health Organization

Multimedia Appendix 1

CONSORT-EHEALTH checklist V1.6.2 [36].

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: All authors were involved in editing the manuscript and approved the final text of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Modlin IM, Kidd M, Latich I, Zikusoka MN, Shapiro MD. Current status of gastrointestinal carcinoids. Gastroenterology. 2005 May;128(6):1717–51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modlin IM, Kidd M, Pfragner R, Eick GN, Champaneria MC. The functional characterization of normal and neoplastic human enterochromaffin cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Jun;91(6):2340–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0110. http://jcem.endojournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16537680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oberg K. Biochemical diagnosis of neuroendocrine GEP tumor. Yale J Biol Med. 1997;70(5-6):501–8. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/9825477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold C. [Neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract] Praxis (Bern 1994) 2007 Jan 10;96(1-2):19–28. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157.96.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klöppel G, Perren A, Heitz PU. The gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine cell system and its tumors: the WHO classification. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004 Apr;1014:13–27. doi: 10.1196/annals.1294.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taal BG, Visser O. Epidemiology of neuroendocrine tumours. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;80 Suppl 1:3–7. doi: 10.1159/000080731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niederle MB, Hackl M, Kaserer K, Niederle B. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: the current incidence and staging based on the WHO and European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society classification: an analysis based on prospectively collected parameters. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010 Dec;17(4):909–18. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0152. http://erc.endocrinology-journals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=20702725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berna MJ, Hoffmann KM, Serrano J, Gibril F, Jensen RT. Serum gastrin in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome: I. Prospective study of fasting serum gastrin in 309 patients from the National Institutes of Health and comparison with 2229 cases from the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006 Nov;85(6):295–330. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000236956.74128.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexandraki KI, Kaltsas G. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: new insights in the diagnosis and therapy. Endocrine. 2012 Feb;41(1):40–52. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9562-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed A, Turner G, King B, Jones L, Culliford D, McCance D, Ardill J, Johnston BT, Poston G, Rees M, Buxton-Thomas M, Caplin M, Ramage JK. Midgut neuroendocrine tumours with liver metastases: results of the UKINETS study. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009 Sep;16(3):885–94. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0042. http://erc.endocrinology-journals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=19458024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerdes J, Lemke H, Baisch H, Wacker HH, Schwab U, Stein H. Cell cycle analysis of a cell proliferation-associated human nuclear antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. J Immunol. 1984 Oct;133(4):1710–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dabbs DJ. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. pp. 222–582. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown DC, Gatter KC. Ki67 protein: the immaculate deception? Histopathology. 2002 Jan;40(1):2–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SJ, Kim JW, Han SW, Oh DY, Lee SH, Kim DW, Im SA, Kim TY, Seog Heo D, Bang YJ. Biological characteristics and treatment outcomes of metastatic or recurrent neuroendocrine tumors: tumor grade and metastatic site are important for treatment strategy. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:448. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-448. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/10/448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modlin IM, Sandor A. An analysis of 8305 cases of carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 1997 Feb 15;79(4):813–29. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970215)79:4<813::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caplin ME, Buscombe JR, Hilson AJ, Jones AL, Watkinson AF, Burroughs AK. Carcinoid tumour. Lancet. 1998 Sep 5;352(9130):799–805. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)02286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maire F, Sauvanet A, Couvelard A, Rebours V, Vullierme MP, Lebtahi R, Hentic O, Belghiti J, Hammel P, Lévy P, Ruszniewski P. Recurrence after surgical resection of gastrinoma: who, when, where and why? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Apr;24(4):368–74. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328350f816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomassetti P, Campana D, Piscitelli L, Casadei R, Nori F, Brocchi E, Santini D, Pezzilli R, Corinaldesi R. Endocrine tumors of the ileum: factors correlated with survival. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;83(5-6):380–6. doi: 10.1159/000096053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panzuto F, Nasoni S, Falconi M, Corleto VD, Capurso G, Cassetta S, Di Fonzo M, Tornatore V, Milione M, Angeletti S, Cattaruzza MS, Ziparo V, Bordi C, Pederzoli P, Delle Fave G. Prognostic factors and survival in endocrine tumor patients: comparison between gastrointestinal and pancreatic localization. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005 Dec;12(4):1083–92. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01017. http://erc.endocrinology-journals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16322345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norton JA, Alexander HR, Fraker DL, Venzon DJ, Gibril F, Jensen RT. Does the use of routine duodenotomy (DUODX) affect rate of cure, development of liver metastases, or survival in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome? Ann Surg. 2004 May;239(5):617–25; discussion 626. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124290.05524.5e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrone CR, Tang LH, Tomlinson J, Gonen M, Hochwald SN, Brennan MF, Klimstra DS, Allen PJ. Determining prognosis in patients with pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: can the WHO classification system be simplified? J Clin Oncol. 2007 Dec 10;25(35):5609–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephenson J. Human genome studies expected to revolutionize cancer classification. JAMA. 1999 Sep 8;282(10):927–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.10.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halvarsson B, Müller W, Planck M, Benoni AC, Mangell P, Ottosson J, Hallén M, Isinger A, Nilbert M. Phenotypic heterogeneity in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer: identical germline mutations associated with variable tumour morphology and immunohistochemical expression. J Clin Pathol. 2007 Jul;60(7):781–6. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.040402. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/16901974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan MS, Tsigani T, Rashid M, Rabouhans JS, Yu D, Luong TV, Caplin M, Meyer T. Circulating tumor cells and EpCAM expression in neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 Jan 15;17(2):337–45. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1776. http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=21224371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drozdov I, Kidd M, Nadler B, Camp RL, Mane SM, Hauso O, Gustafsson BI, Modlin IM. Predicting neuroendocrine tumor (carcinoid) neoplasia using gene expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Cancer. 2009 Apr 15;115(8):1638–50. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoeffel C, Job L, Ladam-Marcus V, Vitry F, Cadiot G, Marcus C. Detection of hepatic metastases from carcinoid tumor: prospective evaluation of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Dig Dis Sci. 2009 Sep;54(9):2040–6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0570-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donati OF, Hany TF, Reiner CS, von Schulthess GK, Marincek B, Seifert B, Weishaupt D. Value of retrospective fusion of PET and MR images in detection of hepatic metastases: comparison with 18F-FDG PET/CT and Gd-EOB-DTPA-enhanced MRI. J Nucl Med. 2010 May;51(5):692–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.068510. http://jnm.snmjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=20395324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schraml C, Schwenzer NF, Sperling O, Aschoff P, Lichy MP, Müller M, Brendle C, Werner MK, Claussen CD, Pfannenberg C. Staging of neuroendocrine tumours: comparison of [⁶⁸Ga]DOTATOC multiphase PET/CT and whole-body MRI. Cancer Imaging. 2013;13:63–72. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2013.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauditz J, Quinkler M, Beyersdorff D, Wermke W. Improved detection of hepatic metastases of adrenocortical cancer by contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Oncol Rep. 2008 May;19(5):1135–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003 Feb 15;97(4):934–59. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rindi G, D'Adda T, Froio E, Fellegara G, Bordi C. Prognostic factors in gastrointestinal endocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2007;18(3):145–9. doi: 10.1007/s12022-007-0020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pavel M, Baudin E, Couvelard A, Krenning E, Öberg K, Steinmüller T, Anlauf M, Wiedenmann B, Salazar R, Barcelona Consensus Conference participants ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with liver and other distant metastases from neuroendocrine neoplasms of foregut, midgut, hindgut, and unknown primary. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95(2):157–76. doi: 10.1159/000335597. http://www.karger.com?DOI=000335597&typ=pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dhall D, Mertens R, Bresee C, Parakh R, Wang HL, Li M, Dhall G, Colquhoun SD, Ines D, Chung F, Yu R, Nissen NN, Wolin E. Ki-67 proliferative index predicts progression-free survival of patients with well-differentiated ileal neuroendocrine tumors. Hum Pathol. 2012 Apr;43(4):489–95. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukuda M. [A pathological comparison of primary and metastatic lesions as a prognostic indicator for renal cell carcinoma] Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 1995 Apr;86(4):870–7. doi: 10.5980/jpnjurol1989.86.870. http://joi.jlc.jst.go.jp/JST.Journalarchive/jpnjurol1989/86.870?lang=en&from=PubMed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, GRADE Working Group GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008 Apr 26;336(7650):924–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/18436948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eysenbach G, CONSORT-EHEALTH Group CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of Web-based and mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e126. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1923. http://www.jmir.org/2011/4/e126/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]