Abstract

Kinetoplast DNA, the mitochondrial DNA of the trypanosomatid Crithidia fasciculata, is a remarkable structure containing 5,000 topologically linked DNA minicircles. Their replication is initiated at two conserved sequences, a dodecamer, known as the universal minicircle sequence (UMS), and a hexamer, which are located at the replication origins of the minicircle L- and H-strands, respectively. A UMS-binding protein (UMSBP), binds specifically the conserved origin sequences in their single stranded conformation. The five CCHC-type zinc knuckle motifs, predicted in UMSBP, fold into zinc-dependent structures capable of binding a single-stranded nucleic acid ligand. Zinc knuckles that are involved in the binding of DNA differ from those mediating protein-protein interactions that lead to the dimerization of UMSBP. Both UMSBP DNA binding and its dimerization are sensitive to redox potential. Oxidation of UMSBP results in the protein dimerization, mediated through its N-terminal domain, with a concomitant inhibition of its DNA-binding activity. UMSBP reduction yields monomers that are active in the binding of DNA through the protein C-terminal region. C. fasciculata trypanothione-dependent tryparedoxin activates the binding of UMSBP to UMS DNA in vitro. The possibility that UMSBP binding at the minicircle replication origin is regulated in vivo by a redox potential-based mechanism is discussed.

Kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) is a unique extrachromosomal DNA, found in the single mitochondrion of parasitic flagellated protozoa of the family Trypanosomatidae. In the species Crithidia fasciculata, the kDNA network consists of 5,000 duplex DNA minicircles of 2.5 kbp and 50 maxicircles of 37 kbp that are interlocked topologically to form a DNA network. Maxicircles contain mitochondrial genes, encoding mitochondrial proteins and rRNA. Minicircles encode guide RNAs that function in the process of mRNA editing (19, 49, 53). Minicircles in most trypanosomatid species are heterogeneous in sequence. However, two short sequences that are associated with the process of replication initiation are located 70 to 100 nucleotides apart on the minicircle molecule: the dodecameric sequence GGGGTTGGTGTA, designated the universal minicircle sequence (UMS), and the hexameric sequence ACGCCC. These sequences have been mapped to the sites of the proposed replication origins of the minicircle L-strand and H-strand, respectively (for reviews, see references 36, 41, 47, and 48).

Several of the proteins involved in the replication of the kDNA network have been identified, including the origin-binding protein, designated the UMS-binding protein (UMSBP) (2-4, 61, 62), DNA polymerases (23, 57-59), primase (30), topoisomerase II (31, 32), structure-specific endonuclease 1 (SSE1) (13, 14), RNase H (9, 12, 42), RNA polymerase (20), and structural proteins (73, 74). UMSBP has been purified from C. fasciculata, and its encoding gene and genomic locus have been cloned and analyzed (2, 61-63). The protein binds specifically to the two sequences conserved at the minicircle replication origins on the kDNA minicircle H-strand: the UMS dodecamer and a 14-mer sequence, containing the core hexamer, in their single-stranded conformation (2, 3, 6, 61, 62). The 116-amino-acid long protein contains five tandemly arranged zinc knuckle motifs. This motif forms a compact zinc finger, which contains the core sequence Cys-X2-Cys-X4-His-X4-Cys (where X represents any amino acid). Proteins bearing this motif, such as the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein (22, 64) and several eukaryotic proteins such as the cellular nucleic-acid binding protein (40), bind single-stranded nucleic acids.

The correct folding of the zinc knuckle motif depends on the presence of a metal ion, which serves as a core element inside the folded structure. The metal ion is held in the knuckle via coordinative bonds formed by the three cysteines and the single histidine residue. It has been found that redox potential may affect the capacity of the cysteine residues to bind the zinc ion in the knuckle (8, 24, 70). Regulation through redox potential has been reported for several zinc finger proteins (for a review, see reference 7), including transcription factors and replication proteins such as replication protein A (65, 75), activator protein 1 (71), and glucocorticoid receptor (21). This type of regulation may influence both the DNA-binding properties of the protein and its protein-protein interactions. A few enzymes involved in redox regulation of proteins have been identified, such as thioredoxin (21) and redox factor 1 (71). Recently, the enzyme thioredoxin, known to regulate the redox state of proteins, was localized to the mitochondrial membrane in the rat (44). Redox modulation of the activity of mitochondrial topoisomerase I was recently reported (27). The enzymatic machinery that regulates redox state in trypanosomatids differs from that found in other eukaryotes, in both its main thiol substrate and its enzymes. Most of the glutathione in trypanosomatids is converted to an N′,N8-bis(glutathionyl)spermidine adduct, known as trypanothione [T(SH)2], which is the main low-molecular-weight thiol in the genera Crithidia, Trypanosoma, and Leishmania (15, 16). T(SH)2 reduces a trypanothione-dependent member of the thioredoxin family, the tryparedoxin (TXN), and reduced TXN, in turn, reduces a peroxyredoxin, called TXN peroxidase (reviewed in references 17, 28, 37, and 52). This unique metabolic pathway has been studied in C. fasciculata, and two tryparedoxins, CfTXN I and CfTXN II (33-35, 38), have been found in this trypanosomatid. Classical thioredoxins have also been found in Trypanosoma brucei and Leishmania major (43).

In this study we show that UMSBP binds the conserved UMS sequence at the replication origin of kDNA minicircles as a monomer in a zinc-dependent manner. Zinc knuckles, located at the C-terminal domain of the protein, are involved in DNA binding, while the N-terminal zinc knuckle is involved in protein-protein interactions that lead to UMSBP dimerization. Moreover, we show that both UMSBP DNA-binding activity and its oligomerization are sensitive to redox potential. In vitro coupling of the trypanothione-dependent tryparedoxin reaction to the UMSBP DNA-binding reaction, reconstituted from pure C. fasciculata proteins, revealed the activation of UMSBP binding to the minicircle origin region and suggested that redox potential may regulate UMSBP function at the kDNA replication origin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotides, enzymes, and reagents.

Primers were prepared by Genset SA. Superdex 75 and protein markers for gel filtration were obtained from Amersham. Dithiothreitol (DTT) was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim; NADPH, dimethyl pimelmidate (DMP), N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), diamide (diazene dicarboxylic acid bis[N,N-dimethylamide]), and 1,10-o-phenanthroline were purchased from Sigma. 1,7-Phenanthroline was obtained from Aldrich. T(SH)2 was purchased from Bachem. T. cruzi recombinant T(SH)2 reductase (TcTR) and C. fasciculata recombinant TXNs (CfTXN1H6 and CfTXN2H6) were a generous gift of L. Flohè from the Department of Biochemistry, Technical University of Braunschweig, Germany. Restriction endonucleases, micrococcal nuclease, and polynucleotide kinase were purchased from MBI Fermentas.

Preparation of UMSBP.

The C. fasciculata UMSBP gene open reading frame (2), cloned into a pGEX1 vector (Amersham) (1), was PCR amplified (Turbo Pfu polymerase; Stratagene) with sense primer UU (5′-GTCCCATGGCCGCTGCTGTCACGTGCTAC-3′) and antisense primer UL (5′-AATCTCGAGGTGGCGGTCCGGGCACTC-3′). NcoI and XhoI restriction endonuclease sites are underlined. PCR conditions were as follows: 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 64°C, and 1 min at 72°C followed by 10 min at 72°C. The PCR product (370 bp), containing the entire coding sequence, was purified by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gel (95 V for 30 min), extracted from the gel, cut with NcoI and XhoI, and cloned into the pET22B+ expression vector (Novagen). A sequence encoding six histidine residues at the C terminus of the protein was added in this procedure. The plasmid was introduced by electroporation into Escherichia coli BL21, and protein expression was induced by the addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 5 h at 37°C or 14 h at 15°C. Cells were harvested and resuspended in buffer L (50 mM potassium phosphate [pH 8], 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and lysed by six cycles of maximum-power sonication bursts of 30 s each (Misonic Sonicator XL). Triton was added to a final concentration of 1% (vol/vol); this was followed by a 30-min centrifugation at 10,000 × g and 4°C. The supernatant was added to Ni-nitrilotriacetate (NTA) beads (Qiagen) and incubated with gentle rotation at 4°C for 2 h. The beads were washed once with 10 bed volumes of buffer L, packed in a column (0.8 by 4.0 cm; a 2.0-ml bed volume of Ni-NTA beads was used for a lysate prepared from a 10-liter cell culture), and washed five more times with 10 bed volumes of buffer L. Finally, the protein was eluted from the column using buffer E (50 mM potassium phosphate [pH 8], 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol). The eluted fraction was loaded onto a phenyl-Sepharose (Pharmacia) column (0.8 by 4.0 cm; a 2.0-ml bed volume of phenyl-Sepharose beads was used for an Ni-NTA-eluted fraction prepared from an original lysate of a 10-liter cell culture), equilibrated with buffer A (50 mM phosphate buffer [pH 8], 1.3 M ammonium sulfate, 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol), and washed sequentially with buffer A containing 0.9, 0.6, 0.45, 0.3, and 0 M ammonium sulfate. UMSBP was detected in the fraction eluted with 0.6 and 0.45 M ammonium sulfate. A 1.0-mg amount of purified recombinant UMSBP was obtained from a 1.0-liter cell culture. This recombinant UMSBP preparation was used throughout this work. Gel filtration analysis of the recombinant UMSBP using Superdex 75 fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) (as described below) showed that the majority (96%) of the pure protein preparation is in a monomeric form, as calculated by the integration of the peak areas.

Deletion mutations in UMSBP were generated by a PCR mutagenesis method (67), using the above plasmid as a template. The N-terminal deletion, designated d1, and the N-terminal zinc knuckles deletion (d1-2), were constructed using sense primer L1 (5′-AGTTGTAGCACGTGACAGCAGCGGA-3′) and antisense primer F2 (5′-GCGGCCAGACCGGCCACCTG-3′) or F3f (5′-GCGGTTCCACCGAGCACCTG-3′), respectively. The C-terminal deletions (d5 and d4-5), were constructed using either sense primer F4 (5′-GCGGCTCAGGTGGCCGGTCTG-3′) or F3r (5′-GGGACAGGTGCTCGGTGGAACCG-3′), respectively, and antisense primer L6 (5′-GAGTGTGCCCGGACCGCCACTAG-3′).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

Analyses were carried out as described previously (61, 62). Samples of UMSBP, as indicated, were incubated in the 20-μl binding-reaction mixture, containing 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), 2 mM MgCl2, 20% (vol/vol) glycerol, 2 μg of bovine serum albumin, 0.5 μg of poly(dI-dC)-poly(dI-dC), and 12.5 fmol of 5′-32P-labeled UMS DNA (5′-GGGGTTGGTGTA-3′). Unless otherwise stated, the reaction mixture contained 1 mM DTT. Pretreatments of UMSBP were conducted as indicated below. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 30 min or on ice for 60 min, and their products were loaded onto an 8% native polyacrylamide gel (1:29, bisacrylamide/acrylamide) in TAE buffer (6.7 mM Tris acetate, 3.3 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.5]). Electrophoresis was conducted at 2 to 4°C and 16 V/cm for 1.5 h. Protein-DNA complexes were quantified by exposing the dried gels to an imaging plate and analyzing them by phosphorimager analysis. One unit of UMSBP activity is defined as the amount of protein required for the binding of 1 fmol of the UMS DNA (5′-GGGGTTGGTGTA-3′) ligand under the standard binding assay conditions (61, 62).

TXN assay.

The TXN reaction was conducted by published procedures (see, e.g., reference 17), with the modifications indicated below. C. fasciculata UMSBP (92 μg/ml) was dialyzed extensively against 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8) and subsequently oxidized by incubation for 30 min on ice in the presence 0.5 mM diamide. The protein was then diluted in the binding-reaction buffer, with no DTT, prior to its introduction at a final concentration of 30 ng/ml into the tryparedoxin reaction mixture. The reaction was conducted under the standard UMSBP-binding assay conditions in the presence of UMSBP (0.6 ng) and 12.5 fmol of 32P-labeled UMS DNA, as described above, with the following modifications: DTT was omitted and the reaction mixture was supplemented with a trypanosomal TNX system, which included either CfTXN I or CfTXN II, at the indicated concentrations, and 20 mM T(SH)2. For the coupling of a T(SH)2 reductase (TR) system, the reaction mixture was supplemented with 1 unit of TcTR per ml and 150 μM NADPH. Reactions, started by the addition of TXN, proceeded for 10 min at 30°C, and their products were analyzed by EMSA and quantified by phosphorimaging, as described above.

Analysis of proteins by SDS-PAGE.

Protein samples in loading buffer, containing 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 6.85), 4% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 3.5% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 10 mM EDTA, were boiled for 10 min and loaded onto a 16.5% Tris-Tricine SDS-polyacrylamide gel (45), along with protein size markers (“Rainbow” prestained low-molecular-weight marker; Amersham). The upper electrophoresis buffer was 0.1 M Tris-Tricine (pH 8.25) containing 0.1% SDS; the lower buffer was 0.2 M Tris-Cl (pH 8.9). Gels were silver stained (69) or blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes for Western blot analysis, as described below. When nonreducing SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) analyses were conducted, β-mercaptoethanol was omitted.

Gel filtration.

Gel filtration chromatography was conducted using a 100- by 1.6-cm Superdex 75 column (Amersham) in an AKTA purifier FPLC instrument (Amersham-Pharmacia). The running buffer was 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5)-150 mM NaCl. Protein elution was monitored using a UV detector to track the absorbance at 220 nm. Results were analyzed using Unicorn version 4.11 software.

Cross-linking of UMSBP and UMS DNA-UMSBP complexes.

A protein sample (1 μg) was incubated for 1 h at 25°C with 10 mM imidoester dimethyl pimelmidate · 2HCl cross-linker (Sigma) in a 10-μl reaction mixture containing 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM CaCl2, and 20% (vol/vol) glycerol. The reaction was stopped by adjusting the solution to a final concentration of 100 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), and its products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. When cross-linking of nucleoprotein complexes was conducted, the reaction was supplemented with 1.0 ng of 32P-labeled UMS DNA. Radiolabeled DNA was detected by phosphoimager analysis, and protein bands were detected by Western blotting and an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) procedure using anti UMSBP antibodies as described below. In samples treated with microcooccal nuclease (MBI Fermentas), 50 U of the nuclease was added and the reaction mixture was incubated for 15 min at 30°C. The reaction was stopped by addition of EGTA to final concentration of 12.5 mM. The bound UMS DNA was relabeled at the newly generated 5′ termini, using 10 U of polynucleotide kinase (MBI Fermentas) and 15 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham) in a 25-μl reaction mixture as specified by the manufacturer. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Free [γ-32P]ATP was removed using a Sephadex G-50 column.

Western blot analysis.

Protein samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE as described above. Protein bands were transferred onto a Protran BA85 cellulose nitrate membrane (Schleicher & Schuell). The membranes were blocked by incubation for 30 min in 5% dry skim milk (Difco) in phosphate-buffered saline (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4, 1.4 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.4]) containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 and probed for 90 min with anti-UMSBP antibodies that were raised in rabbit and were affinity purified. The membranes were probed for 45 min with a 1:13,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies and subjected to ECL as recommended by the manufacturer (Amersham-Pharmacia).

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis.

Surface plasmon resonance SPR studies were conducted using a BIAcore 3000 at the BIAcore unit, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. A 3′-biotinylated UMS DNA (5′-GGGGTTGGTGTAGTAT-3′) had been immobilized to an SA sensor chip (BIAcore), as recommended by the manufacturer. The DNA-binding activity of the proteins was measured by injection of 0.025 to 2 μM wild-type or mutated UMSBP into the DNA-bound flow channel, using an empty flow channel as the background. Kinetic analysis was performed by automated injection of various protein concentrations (30 μl/min; 3-min association time and 3-min dissociation time) in 10 mM HEPES (pH 8)-150 mM NaCl-5mM DTT-2 mM MgCl2. No mass transfer was detected under these conditions. Binding constants were calculated with the BIAevaluation 3.1 program, using the Langmuir 1:1 binding model.

Atomic absorption spectrophotometry.

Analyses of zinc and other metal ions in UMSBP were conducted with a 300/400 Zeeman instrument as recommended by the manufacturer (Varian). Zn, Mg, Mn, Cu, and Fe were analyzed at the specific wavelengths and using the corresponding standard solutions in triple-distilled water.

RESULTS

UMSBP binding to UMS is zinc dependent.

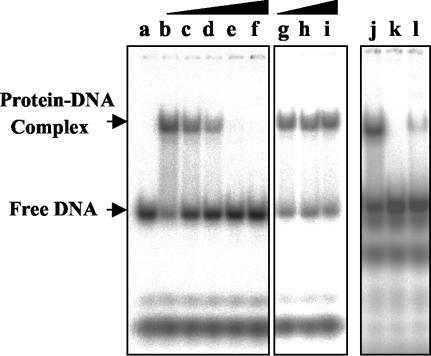

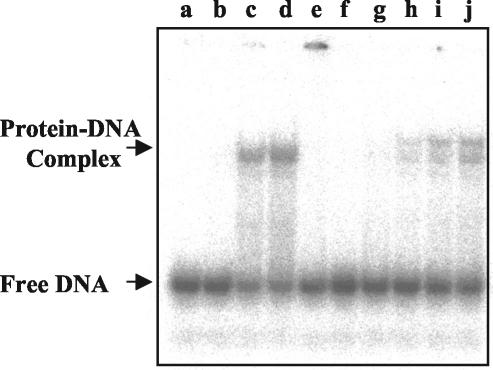

UMSBP contains five putative CCHC, retrovirus-type zinc knuckle domains. Correct folding of such domains has been previously shown to be dependent on the binding of zinc ions (18, 54). The intrinsic association of zinc ions with UMSBP has been determined using an atomic absorption spectrograph. A significant signal above the background level was obtained, which was specific to zinc ions, while the signals obtained in the analyses conducted for detecting other metal ions (e.g., Mn, Mg, Cu, and Fe ions) yielded no signal above background levels (data not shown). To explore the possibility that UMSBP interacts with DNA via a zinc-dependent mechanism, we used EMSA to analyze the binding of a 32P-labeled UMS ligand by UMSBP, which was pretreated with either the zinc chelator 1,10-o-phenanthroline or its nonchelating close analogue 1,7-phenanthroline. Figure 1 shows that whereas the formation of specific protein-DNA complexes is inhibited in the presence of 1,10-o-phenanthroline, yielding 55% inhibition at 50 nM and complete inhibition at 150 nM zinc chelator, its closely related 1,7-phenanthroline nonchelating analogue has no effect on the binding of UMSBP to UMS DNA even at concentrations more than an order of magnitude higher. Moreover, the DNA-binding activity of the o-phenanthroline-treated UMSBP could be partially restored by its incubation in the presence of zinc ions (Fig. 1). These observations indicate that UMSBP-DNA interactions are zinc dependent, implying the requirement for the specific zinc knuckle topology for protein-DNA interactions.

FIG. 1.

UMSBP binding to DNA is zinc dependent. UMSBP was preincubated in the reaction mixture under the standard binding-reaction conditions, as described in Materials and Methods, with increasing concentrations of either 1,10-o-phenanthroline or the nonchelating form, 1,7-phenanthroline. Lanes: a, no UMSBP was added; b, no 1,10-o-phenanthroline was added; c to f, 0.075, 0.1, 0.125, and 0.15 μM 1,10-o-phenanthroline, was added; g to i, 0.275, 1.325, and 2.75 μM 1,7-phenanthroline was added; j, no 1,10-o-phenanthroline was present; k, UMSBP was preincubated with 0.2 μM 1,10-o-phenanthroline; 1, the preincubation with 0.2 μM 1,10-o-phenanthroline was followed by treatment with 2.0 μM ZnCl2. EMSA and its quantification were as described in Materials and Methods.

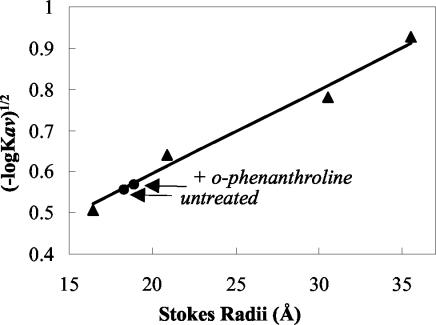

Next, we studied the effect of chelating the zinc ions with 1,10-o-phenanthroline on the structure of UMSBP by gel filtration chromatography using an FPLC Superdex-75 column. Analysis of the untreated native protein yielded a single peak with a retention time of 232.76 ± 0.13 min. Treatment of the native protein with 1,10-o-phenanthroline prior to the gel filtration analysis resulted in a decrease in its retention time to 229.98 ± 0.13 min. The corresponding Stokes radii, calculated based on analyses of UMSBP and protein markers (Fig. 2), were 18.9 and 18.3 Å (Δ = 0.6 ± 0.0034 Å). We suggest that this effect on the pattern of the UMSBP chromatograph may reflect the distortion of the compact folded structure of the zinc knuckle domains in the protein as a result of the removal of the metal ions.

FIG. 2.

Gel filtration of 1,10-o-phenanthroline-treated UMSBP. UMSBP was analyzed by gel filtration chromatography either in its native form or in the presence of 5 mM 1,10-o-phenanthroline, using a 100- by 1.6-cm Amersham Superdex 75 column, as described in Materials and Methods. Protein markers and their Stokes radii were as follows: RNase A, 16.4 Å; chymotrypsinogen A, 20.9 Å; ovalbumin, 30.5 Å; and albumin, 35.5 Å. The arrows mark the calculated Stokes radii for the 1,10-o-phenanthroline-treated and untreated UMSBP. The column Vo and Vt were determined by using Blue Dextran and B12, respectively. All proteins were detected by measuring the absorbance at 220 nm. UMSBP Stokes radii were interpolated from the linear plot of known Stokes radii against the −log Kav1/2 of the protein markers. The difference in the retention time between o-phenanthroline-treated and untreated UMSBP was 2.78 ± 0.13 min, reflecting a 0.6-Å difference in the calculated Stokes radii, and the standard deviation measured in these analyses of UMSBP and protein markers yielded an error of ±0.0034 Å.

Overall, these observations indicate that zinc ions are intrinsically present in UMSBP and that the ability of the protein to bind DNA is zinc dependent, probably through the formation of zinc knuckles, as predicted from its amino acid sequence.

UMSBP binds UMS DNA as a monomer.

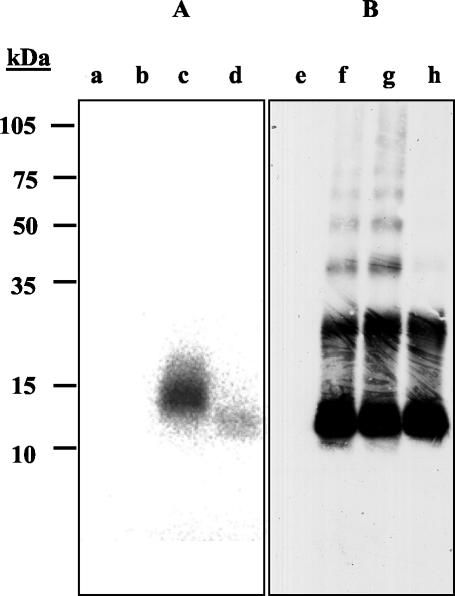

UMSBP was purified from C. fasciculata cell extracts as a protein dimer (61, 62). Stoichiometry analysis, based on the ratio of radioactively labeled UMSBP and UMS DNA in nucleoprotein complexes under native gel electrophoresis conditions, indicated that two protein monomers bind a single DNA molecule (61). However, structural studies have shown that the CCHC-type zinc knuckle in the nucleocapsid protein of retroviruses can bind the nucleic acid ligand as a monomer (11, 46). To study the nature of UMSBP binding, we used a direct in vitro cross-linking approach. UMSBP was incubated with 32P-labeled UMS DNA in the presence of the imidoester cross-linker DMP. The reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under denaturing and reducing conditions. Alternatively, prior to their analysis in the SDS-PAGE gel, the cross-linked protein-DNA complexes were treated with micrococcal endonuclease and the newly generated 5′ termini in the bound DNA were relabeled in a polynucleotide kinase reaction (Fig. 3). 32P-labeled UMS DNA bands were detected by phosphorimaging, and the protein bands, representing UMSBP monomers, dimers, and multimers, were detected by Western blot analysis using anti-UMSBP antibodies. Figure 3 shows that the electrophoretic mobility of bound UMS DNA was slightly lower than that of free UMSBP monomers (Fig. 3, lane c). This is probably due to the contribution of the bound DNA ligand, since the subsequent digestion of the unprotected sequences in the bound ligand yielded, following its relabeling, a radioactively labeled protein-DNA complex with electrophoretic mobility that was virtually identical to that of the UMSBP monomer (lane d). Neither the bands representing UMSBP dimers nor those representing other protein oligomers displayed any [32P]DNA signal, indicating the generation of nucleoprotein complexes exclusively with the monomeric form of UMSBP. No [32P]DNA signal could be detected in the gel when UMSBP was omitted from the binding-reaction mixture. These results suggest that UMSBP is capable of binding UMS DNA in its monomeric form.

FIG. 3.

A UMSBP monomer binds the UMS DNA. 1.0 ng of 32P-labeled UMS DNA (lanes a and e), 1 μg of UMSBP (lanes b and f), and UMSBP with 32P-labeled UMS DNA (lanes c, d, g, and h) were incubated in the presence of 10 mM DMP. In lanes d and h, the nucleoprotein complexes were treated first with micrococcal nuclease and subsequently with [γ-32P]ATP, using polynucleotide kinase, as described in Materials and Methods. The reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide) under denaturing and reducing conditions and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane as described in Materials and Methods. (A) 32P-labeled UMS DNA was detected by exposure to a phosphorimaging plate. (B) The membrane was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-UMSBP antibodies and developed using an ECL protocol, as described in Materials and Methods.

Redox potential significantly affects the binding of UMS DNA by UMSBP.

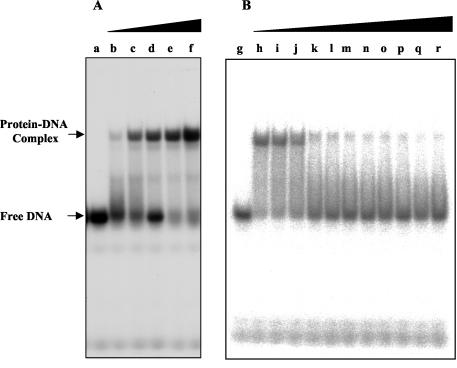

It has been previously reported that zinc ions are held in the CCHC-type zinc knuckle via coordinate bonds, formed by its three cysteine and one histidine residues. Oxidation of cysteines in the zinc finger domain may affect the binding of zinc, thus changing the conformation of the protein. Such changes may result in the formation of intra- or interknuckle S-S bonds and the ejection of the zinc ion (8, 24, 70), affecting the protein DNA-binding activity and protein-protein interactions. It has also been shown that redox potential is regulating the DNA-binding activity of several zinc finger proteins, such as replication protein A (RPA), Sp1, and glucocorticoid receptor (39, 55). To test whether redox potential regulates the DNA-binding activity of UMSBP, the effect of either a reducing agent (DTT) or an oxidizing agent (diamide) on the binding of UMSBP to UMS was studied using EMSA (Fig. 4). In the absence of DTT, almost no DNA-binding activity (<5.5% of the untreated control) could be detected. Raising the concentration of DTT resulted in an increase in the generation of protein-DNA complexes, until saturation was reached at about 20 mM DTT (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, increasing the concentration of the oxidizing agent diamide (in the presence of a constant level of 0.6 mM DTT) resulted in a concomitant decrease in the generation of UMSBP-UMS nucleoprotein complexes (Fig. 4B). Thus, the redox state of UMSBP is found here to critically affect its DNA-binding activity.

FIG. 4.

UMSBP binding is regulated by the redox potential. A 12.5-fmol portion of 32P-labeled UMS DNA was incubated under the standard binding reaction conditions with 0.04 pmol of UMSBP in the presence of increasing concentrations of either DTT (A) or diamide (B). Reaction products were analyzed by EMSA and quantified by phosphorimaging, as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Lanes: a, no protein added; b to f, 0.00, 0.020, 0.20, 2.00, and 20 mM DTT added. (B) Lanes: g, no protein added; h, no diamide added and the reaction mixture contained 5 mM DTT; i to r, 0.00, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, and 1.0 mM diamide added and the reaction mixtures contained 0.6 mM DTT.

It has been previously reported that reversible oxidation of thiol groups in zinc-coordinated cysteines within zinc fingers may mediate the binding of transcription factors as well as replication proteins onto the DNA (39, 66, 70). Considering the observations presented here that binding of DNA by UMSBP was sensitive to oxidation of thiol groups by diamide and their reduction by DTT (Fig. 4), we have examined the sensitivity of the UMSBP DNA-binding reaction to NEM, an agent that alkylates thiol groups. Figure 5 demonstrates the effect of pretreatment of UMSBP with NEM on the binding of 32P-labeled UMS DNA ligand, either in the absence or in the presence of a 10-fold molar excess of DTT in the binding reaction. NEM completely (>99.5%) inhibited the generation of UMSBP-UMS complexes, while addition of DTT following the NEM treatment partially reversed this inhibition. Interestingly, addition of DTT following the NEM treatment resulted in the formation of two distinct protein-DNA complexes. The first corresponded in its electrophoretic mobility to the nucleoprotein complex formed with the untreated UMSBP, whereas the second displayed a lower electrophoretic mobility, which may reflect an additional mass due to the addition of alkyl groups to the protein or other changes in the nucleoprotein structure.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of UMSBP DNA-binding activity by NEM. UMSBP (0.3, 0.5, and 0.7 ng) was treated for 60 min on ice with 2 mM DTT (lanes b to d), 5 mM NEM (lanes e to g), or 5 mM NEM followed by 50 mM DTT (lanes h to j) before being incubated with 32P-labeled UMS DNA. Binding reactions were conducted under the standard binding assay conditions, and their products were analyzed by EMSA and quantified by phosphorimaging, as described in Materials and Methods. In lane a, no UMSBP was added.

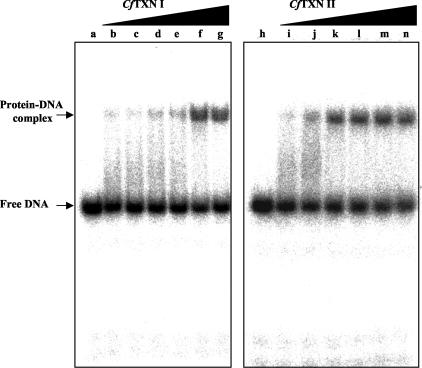

CfTXN I and CfTXN II activate UMSBP binding to DNA.

Thioredoxin is involved in vivo in the regulation of the redox state and DNA-binding activity of proteins (see, e.g., references 21 and 72). A T(SH)2-dependent member of the thioredoxin family, TXN, was found in various trypanosomatid species (reviewed in references 17, 28, 37, and 52) including C. fasciculata, for which the presence of two TXNs, CfTXN I and CfTXN II, has been reported (33-35, 38). To test the physiological significance of the regulation of UMSBP binding to DNA through the protein redox state, we have coupled, in vitro, the UMSBP-binding reaction to the reactions catalyzed by TXN and TR. This coupled reaction, reconstituted from pure trypanosomal proteins, was based on the TXN reaction system (TXN I or TXN II) that uses pure TXN and T(SH)2 and the TR reaction that uses pure TR and NADPH, coupled to a specific DNA-binding reaction that consists of pure (preoxidized) UMSBP and 32P-labeled UMS DNA ligand. The generation of nucleoprotein complexes was analyzed using the EMSA. The results presented in Fig. 6 show clearly the TXN-dependent binding of UMSBP to UMS DNA, similar to the effect observed with the reduction of thiol groups by DTT shown above (Fig. 4). The effect of the TXN reaction on the binding of UMSBP to UMS observed in the in vitro-reconstituted reaction suggests the potential physiological role in vivo for UMSBP redox state control in the regulation of UMSBP binding at the minicircle replication origin.

FIG. 6.

CfTXNs activate the binding of UMSBP to UMS DNA. UMSBP (0.6 ng), which was preoxidized by diamide as described in Materials and Methods, was used as a substrate. The TXN reaction, conducted as described in Materials and Methods, was performed with either increasing concentrations of CfTXN I (lanes c to g) or CfTXN II (lanes j to n). Binding reactions were conducted under the standard binding assay conditions, except that DTT was omitted, in the presence of 12.5 fmol of 32P-labeled UMS DNA, and their products were analyzed by EMSA and quantified by phosphorimaging, as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes: a and h, no UMSBP and tryparedoxin added; b and i, no TXN added; c to g, 0.01, 0.02, 0.04, 0.06, and 0.1 μM CfTXN I; j to n, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1 μM CfTXN II.

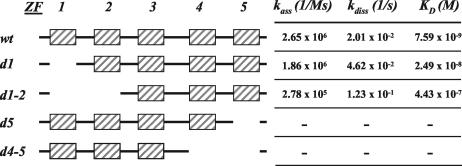

The N-terminal zinc knuckle of UMSBP is not involved in DNA binding.

Zinc fingers are known to participate in both DNA binding and protein-protein interactions (for a review, see reference 7). To further analyze the involvement of UMSBP zinc finger domains in protein-DNA interactions, we constructed a series of truncation mutants of the protein (Fig. 7). Zinc knuckles located at either the N-terminal or the C-terminal domain of the protein were deleted, and the capacity of the truncated proteins to bind UMS DNA was assayed using EMSA (not shown), as well as by the SPR BIAcore technology (Fig. 7), measuring the equilibrium binding constant of the reactions as well as their kinetics parameters. Truncation of the N-terminal knuckle (d1, Fig. 7) had only a limited effect on the binding of UMSBP to UMS DNA. The reaction equilibrium binding constant was only about threefold higher with the mutated protein than that measured with the wild-type UMSBP. A very similar association rate and only an approximately twofold higher dissociation rate, measured with this truncated protein, may suggest some effect of the first N-terminal knuckle on the stability of the nucleoprotein complex. Truncation of both N-terminal knuckles 1 and 2 (d1-2, Fig. 7) resulted in a further increase (∼58-fold relative to the wild-type protein) in the reaction KD, with a decrease of ∼9.5-fold in its association rate and an increase of ∼6-fold in its dissociation rate, relative to the nonmutated protein. EMSAs have revealed the efficient generation of nucleoprotein complexes with both d1 (see Fig. 10) and d1-2 (data not shown) N-terminally truncated UMSBP. On the other hand, truncation of knuckle 5 (d5, Fig. 7) or both knuckles 4 and 5 (d4-5, Fig. 7) at the UMSBP C-terminal domain had a remarkable effect on the capacity of UMSBP to bind the UMS DNA, resulting in no detectable nucleoprotein complexes by EMSA and no measurable such interactions in the BIAcore analysis (Fig. 7). These results indicate that zinc knuckles located at the carboxy-terminal domain of the protein play a major role in the binding of the nucleic acid by UMSBP. Preliminary observations revealed that mutating the single tyrosine residue in zinc finger 2 into an alanine resulted in an approximately fivefold decrease in UMSBP capacity to bind DNA whereas a similar substitution of the tyrosine residue in zinc finger 3 completely inhibited the DNA-binding activity of UMSBP (data not shown). While the involvement of zinc knuckle 2 in the DNA-binding reaction has yet to be further studied, these observations support the lack of contribution of the N-terminal knuckle (zinc finger 1, Fig. 7) to UMSBP-UMS DNA interactions, since its truncation has no significant effect on the affinity of the protein to DNA.

FIG. 7.

UMSBP C-terminal zinc knuckles are involved in DNA binding. A series of truncated mutants of UMSBP were constructed by PCR as described in Materials and Methods. A schematic representation of UMSBP truncation mutants is presented. Deleted amino acid sequences are as follows: in d1, amino acid residues at position 1 to 29, including the N-terminal zinc knuckle; in d1-2, amino acid residues at positions 1 to 51, encompassing the first two N-terminal knuckles; in d5, amino acid residues at positions 90 to 116, including the C-terminal knuckle; and in d4-5, amino acid residues at positions 65 to 116, encompassing the last two C-terminal knuckles. Numbering is as previously described (11). The indicated binding-reaction parameters were obtained from SPR analyses as described in Materials and Methods. Calculated χ2 values were as follows: wt, 4.44; d1, 2.09; d1-2, 6.58. wt, wild type.

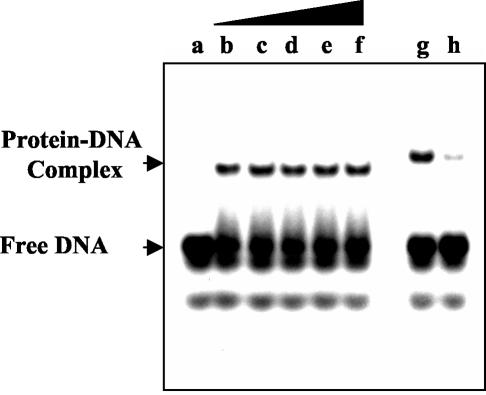

FIG. 10.

DNA binding of an N-terminally truncated UMSBP is insensitive to oxidation. 32P-labeled UMS DNA (12.5 fmol) was incubated under the standard binding reaction conditions with 100 fmol of d1 UMSBP mutant (lanes b to f) or 40 fmol of wild-type UMSBP (lanes g and h) in the absence (lanes b and g) or the presence (lanes c to f and h) of diamide, as indicated below. Reaction products were analyzed by EMSA and quantified by phosphorimaging as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes: a, no protein added; b to f, 0.00, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 1.0 mM diamide; g, no diamide added; h, 1.0 mM diamide.

Multimerization of UMSBP is affected by the redox potential.

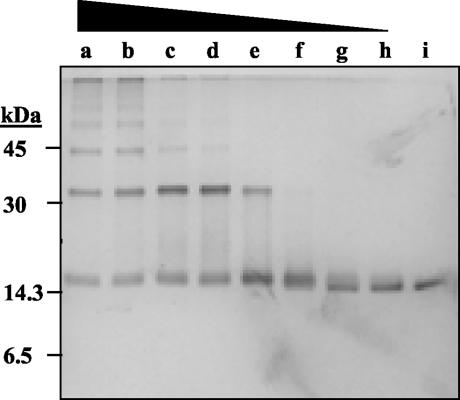

UMSBP was purified from C. fasciculata as a homodimer (61, 62). Furthermore, as shown above (Fig. 3), treatment of UMSBP with a chemical cross-linker resulted in the oligomerization of the protein. Considering the effect of the redox potential on the binding of UMS by a UMSBP monomer reported here (Fig. 3), we tested the possibility that multimerization of UMSBP is mediated through the redox potential of the protein. As shown by SDS-PAGE analysis under nonreducing conditions (Fig. 8), treatment of UMSBP with low levels of the oxidizing agent diamide resulted in the generation of UMSBP dimers, while a further increase in the diamide concentration generated higher UMSBP oligomers such as trimers and tetramers.

FIG. 8.

The redox potential controls UMSBP oligomerization. UMSBP was incubated for 30 min at 25°C with increasing concentrations of diamide and then subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis under nonreducing conditions and silver staining as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes: a to g, reactions were carried out in the presence of 10.00, 5.00, 1.00, 0.50, 0.10, 0.05, and 0.01 mM diamide; h, no diamide was present in the reaction mixture; i, reaction mixture contained 5 mM DTT.

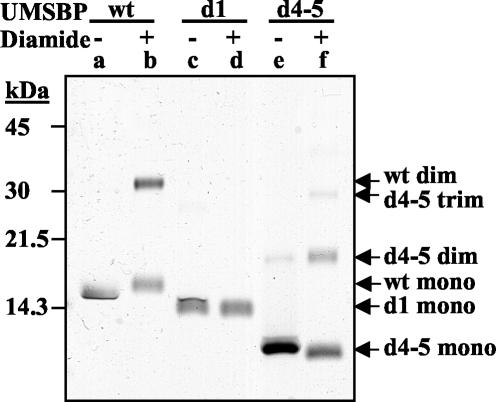

Next, we identified the domain in UMSBP involved in the multimerization of the protein. Analysis of two of the truncation mutants described above (Fig. 7), d1 and d4-5, shows that deletion of the N-terminal zinc knuckle (zinc finger 1) per se was sufficient to prevent UMSBP dimerization in the presence of diamide whereas deletion of the C-terminal knuckle (zinc finger 5) had no inhibitory effect on the protein oligomerization (Fig. 9). In fact, truncation of the C-terminal domain even enhanced protein multimerization compared to the full-length protein (Fig. 9). We noticed slight changes in the electrophoretic mobility of the protein in the presence of diamide. These changes may be due to the formation of intramolecular S-S bonds; however, the nature of these changes has yet to be explored.

FIG. 9.

The N-terminal zinc-finger is involved in UMSBP oligomerization. The multimerization was conducted as describe in the legend to Fig. 8, in the absence of an oxidizing agent (lanes a, c, and e) or in the presence (lanes b, d, and f) of 0.5 mM diamide. Lanes: a and b, full-length (wild-type [wt]) UMSBP; c and d, N-terminal knuckle truncation mutant (d1); e and f, C-terminal knuckle truncation mutant (d4-5). Mutants are as described in the legend to Fig. 8. The arrows point on the monomers (mono), dimers (dim), and trimers (trim) of the wild-type and mutated UMSBP.

DNA binding of N-terminal deleted UMSBP is insensitive to the redox potential.

Since both UMSBP dimerization and its capacity to bind the nucleic acid are affected by the redox potential, an interesting mechanistic question was whether redox directly affects the C-terminal DNA-binding domain or, alternatively, acts indirectly through its effect on the protein dimerization. To address this question, we have used a UMSBP mutant protein (d1, Fig. 7), in which the N-terminal domain was truncated, interrupting the first zinc finger domain (ZF 1, Fig. 7). As described above, while truncation of the N-terminal zinc finger sequence, per se, was sufficient to prevent the dimerization of UMSBP in the presence of diamide (Fig. 9), it had only a limited effect on protein binding to DNA (Fig. 7). Figure 10 shows the results of binding experiments in which radiolabeled UMS DNA was incubated with either the d1 UMSBP mutant or wild-type UMSBP in the presence of diamide and the reaction products analyzed by EMSA. It demonstrates that whereas diamide inhibited the binding of the wild-type UMSBP to DNA, it had no detectable effect on the DNA-binding capacity of the N-terminally truncated UMSBP mutant (Fig. 10). These observations indicate that redox potential directly affects the N-terminal domain of UMSBP and that this effect results in the changes observed in the capacity of the C-terminal DNA-binding domain to bind the nucleic acid. Based on these data, we suggest that the zinc finger motifs at the protein C-terminal domain, which are essential for the sequence-specific DNA-binding activity of the protein, are not involved in the redox potential-mediated regulation of protein-DNA interactions. Instead, the N-terminal zinc finger domain, which is not involved directly in DNA binding, functions as a regulatory element in UMSBP redox potential-dependent DNA-binding activity.

Based on these results, we suggest that the redox effect observed here on both UMSBP dimerization (Fig. 9) and its capacity to bind the nucleic acid (Fig. 4, 6, and 7) imply that the protein dimerization, via thiol groups oxidation, may participate in a regulatory mechanism that controls UMSBP binding to the minicircle replication origin.

DISCUSSION

UMSBP has been suggested to play a key role in the replication of kDNA minicircles in trypanosomatids. The protein binds specifically to two origin-associated sequences: a conserved 12-mer UMS and the 14-mer sequence containing the conserved hexamer. One set of the two conserved sequences, which were previously implicated in minicircle replication initiation, is found in each of the two copies of the origin region in C. fasciculata. In this study, we analyzed the DNA-binding characteristics and oligomerization of UMSBP. The protein sequence predicts five potential tandemly arranged, CCHC retrovirus-type zinc knuckles. Zinc ions were found to be present in UMSBP that was purified to apparent homogeneity from C. fasciculata and to be essential for its binding to UMS DNA. These data imply that the CCHC knuckles, predicted in silico from the UMSBP coding sequence, may indeed fold into zinc knuckle conformation in the protein. It was further found that the zinc knuckles involved in DNA binding are distinct from those that participate in oligomerization of the protein. While UMSBP C-terminal zinc knuckles are essential for DNA-binding activity, the sequence of the N-terminal Zn knuckle is involved in oligomerization through protein-protein interactions. The observations presented here support the possibility that redox potential controls both DNA binding and dimerization of UMSBP and hence may participate in a mechanism that regulates its function at the replication origin. Furthermore, the data presented here (Fig. 9 and 10) indicate that changes in redox potential affect the protein N-terminal zinc knuckle domain but do not have a direct effect on the capacity of its C-terminal zinc knuckles to interact with DNA. Based on these observations, we suggest that zinc knuckles at the protein C-terminal domain, which are essential for sequence-specific DNA binding, are not involved in the redox potential-mediated regulation of protein-DNA interactions whereas the N-terminal zinc finger domain, which is not involved directly in DNA binding, functions as a regulatory element in the redox potential-dependent binding of UMSBP to DNA.

Our previous analysis of doubly labeled UMSBP-UMS DNA complexes under native conditions suggested a 2:1 stoichiometry of bound UMSBP monomers per UMS site (61). We demonstrate here, by analysis of chemically cross-linked protein-DNA complexes in SDS-PAGE under denaturing and reducing conditions that UMSBP is bound in the nucleoprotein complex as a monomer. Binding of a single site in the protein is also in agreement with our previous observations that when reacted with either of its binding sequences, UMSBP could not bind two such binding sites simultaneously (3, 61). If, indeed, UMSBP was capable of DNA binding as a dimer, one had to assume that UMSBP dimers different from the ones described here were generated, since the redox potential-dependent UMSBP dimers have no DNA-binding activity.

Traditionally, zinc fingers have been associated with binding of nucleic acids. However, a few zinc finger families, such as the GATA, LIM, and RING domains, have also been implicated in protein-protein interactions (for a review, see reference 7). The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein, bearing two CCHC-type zinc knuckles similar to those of UMSBP, interacts with both RNA and the Vpr protein via its C-terminal zinc knuckle domain (5, 11, 50). In UMSBP, different domains are involved in protein-protein interactions and in the binding of the nucleic acid. The N-terminal zinc knuckle, which was found to be involved in UMSBP dimerization, differs from the other knuckles in the protein in its amino acid composition, as well as in its flanking amino acid residues. It may be significant that the UMSBP N-terminal zinc knuckle differs from the rest of the zinc knuckles in the protein in having a methionine residue within the knuckle. Mass spectrometry analysis under denaturing, nonreductive conditions revealed that this methionine residue was oxidized (data not shown). The presence of oxidized methionine residues within zinc fingers that are regulated by redox potential has been previously reported (10, 51).

As an origin-binding protein, UMSBP is expected to act during the initiation of kDNA replication in the recruitment of other replication proteins, such as helicase and primase, to the replication origin through protein-protein interactions. Preliminary observations indicate that such interactions between UMSBP and other replication proteins may indeed take place in C. fasciculata cell extracts (N. Milman-Shtepel and J. Shlomai, unpublished observations). If the N-terminal domain of UMSBP was involved in these protein-protein interactions as well, one could speculate that binding of a UMSBP monomer to the UMS site via its C-terminal domain, as suggested here, would leave the N-terminal domain free to mediate these protein-protein interactions at the replication origin. In such a model, dimerization of UMSBP would not only render it inactive in binding the replication origin but also block its N-terminal domain for interactions with other replication proteins.

UMSBP was immunolocalized to two discrete foci, located close to the surface of the kDNA disk, facing the kineto-flagellar zone (4). These protein foci may represent a UMSBP reservoir rather than an active form of the protein. We have previously reported that the immunolocalization and abundance of these UMSBP foci change throughout the cell cycle, with no apparent concomitant changes in either the steady-state levels of UMSBP mRNA or its rate of translation (4). We have found here that UMSBP multimerization (as well as its binding to DNA) is sensitive to the redox potential of the protein. Moreover, TXN, an enzyme of the family of thioredoxins that have previously been shown to function in redox regulation of nuclear proteins, affected the binding of UMSBP to DNA. One could speculate that the UMSBP clusters observed in the kinetoplast before and during the S phase of the cell cycle (4) represent the accumulation of pools of protein in this organelle in preparation for the beginning of kDNA replication. These pools may represent oligomerized UMSBP molecules that are activated prior to the onset of kDNA replication initiation by their reduction and hence by their monomerization. Such a redox potential-based model may also be applied to the regulation of the other kDNA replication proteins, such as those located at the two antipodal foci at the periphery of the kDNA disk. Similarly to UMSBP, the aggregation of these proteins into the foci seen by fluorescence microscopy and the changes in abundance of these foci throughout the cell cycle are not yet understood. In this context, the recent reports of T(SH)2-dependent TXN peroxidase in the mitochondrion of T. cruzi (68) and T. brucei (56) makes this type of proposed regulatory mechanism an attractive model for further investigation. The redox potential controls the conversion of UMSBP monomers into dimers and vice versa. Studies of the eukaryotic green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii chloroplast DNA replication and redox regulation of RPA (65, 75) and mitochondrial topoisomerase I (27) activities suggest that redox potential may be critical for the control of DNA replication in the nucleus as well as in other cell organelles (29). A replication initiation control mechanism, based on the conversion of inactive dimers into active monomers, was reported in the case of TrfA protein that controls the replication of the broad-host-range plasmid RK2 (26, 60). The protein is active as a monomer and inactive as a dimer, and the monomer-dimer ratio in the cell is controlled by the ClpX protein (25). Whether a similar redox potential-controlled mechanism regulates the action of UMSBP at the kDNA replication origin and hence controls kDNA replication initiation has yet to be explored.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported, in part, by grants from the United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF) and the Israel Science Foundation, founded by the Academy of Sciences and Humanities (ISF). I.O was supported by a Yeshaya Horovitz Fellowship.

We are grateful to L. Flohè from the Department of Biochemistry, Technical University of Braunschweig, Germany, for his generous gift of T. cruzi trypanothione reductase, C. fasciculata tryparedoxins, and T. brucei tryparedoxin. We thank O. Moshel from the Faculty of Medicine, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, for her help and advice with the MS analysis, and S. Shochat from the Institute of Life Sciences, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, for her help and advice with the BIAcore analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abeliovich, H., and J. Shlomai. 1995. Reversible oxidative aggregation obstructs specific proteolytic cleavage of glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins. Anal. Biochem. 228:351-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abeliovich, H., Y. Tzfati, and J. Shlomai. 1993. A trypanosomal CCHC-type zinc finger protein which binds the conserved universal sequence of kinetoplast DNA minicircles: isolation and analysis of the complete cDNA from Crithidia fasciculata. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:7766-7773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu-Elneel, K., I. Kapeller, and J. Shlomai. 1999. Universal minicircle sequence-binding protein, a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein that recognizes the two replication origins of the kinetoplast DNA minicircle. J. Biol. Chem. 274:13419-13426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu-Elneel, K., D. R. Robinson, M. E. Drew, P. T. Englund, and J. Shlomai. 2001. Intramitochondrial localization of universal minicircle sequence-binding protein, a trypanosomatid protein that binds kinetoplast minicircle replication origins. J. Cell Biol. 153:725-734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amarasinghe, G. K., R. N. De Guzman, R. B. Turner, and M. F. Summers. 2000. NMR structure of stem-loop SL2 of the HIV-1 psi RNA packaging signal reveals a novel A-U-A base-triple platform. J. Mol. Biol. 299:145-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avrahami, D., Y. Tzfati, and J. Shlomai. 1995. A single-stranded DNA binding protein binds the origin of replication of the duplex kinetoplast DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:10511-10515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldwin, M. A., and C. C. Benz. 2002. Redox control of zinc finger proteins. Methods Enzymol. 353:54-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg, J. M., and Y. Shi. 1996. The galvanization of biology: a growing appreciation for the roles of zinc. Science 271:1081-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell, A. G., and D. S. Ray. 1993. Functional complementation of an Escherichia coli ribonuclease H mutation by a cloned genomic fragment from the trypanosomatid Crithidia fasciculata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9350-9354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis, D. A., F. M. Newcomb, J. Moskovitz, P. T. Wingfield, S. J. Stahl, J. Kaufman, H. M. Fales, R. L. Levine, and R. Yarchoan. 2000. HIV-2 protease is inactivated after oxidation at the dimer interface and activity can be partly restored with methionine sulphoxide reductase. Biochem. J. 346:305-311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Guzman, R. N., Z. R. Wu, C. C. Stalling, L. Pappalardo, P. N. Borer, and M. F. Summers. 1998. Structure of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein bound to the SL3 psi-RNA recognition element. Science 279:384-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engel, M. L., J. C. Hines, and D. S. Ray. 2001. The Crithidia fasciculata RNH1 gene encodes both nuclear and mitochondrial isoforms of RNase H. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:725-731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engel, M. L., and D. S. Ray. 1999. The kinetoplast structure-specific endonuclease I is related to the 5′ exo/endonuclease domain of bacterial DNA polymerase I and colocalizes with the kinetoplast topoisomerase II and DNA polymerase beta during replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8455-8460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engel, M. L., and D. S. Ray. 1998. A structure-specific DNA endonuclease is enriched in kinetoplasts purified from Crithidia fasciculata. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:4733-4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fairlamb, A. H., P. Blackburn, P. Ulrich, B. T. Chait, and A. Cerami. 1985. Trypanothione: a novel bis(glutathionyl)spermidine cofactor for glutathione reductase in trypanosomatids. Science 227:1485-1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fairlamb, A. H., and A. Cerami. 1985. Identification of a novel, thiol-containing co-factor essential for glutathione reductase enzyme activity in trypanosomatids. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 14:187-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flohe, L., P. Steinert, H. J. Hecht, and B. Hofmann. 2002. Tryparedoxin and tryparedoxin peroxidase. Methods Enzymol. 347:244-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao, Y., K. Kaluarachchi, and D. P. Giedroc. 1998. Solution structure and backbone dynamics of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus (MPMV) nucleocapsid protein. Protein Sci. 7:2265-2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gott, J. M., and R. B. Emeson. 2000. Functions and mechanisms of RNA editing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 34:499-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grams, J., J. C. Morris, M. E. Drew, Z. Wang, P. T. Englund, and S. L. Hajduk. 2002. A trypanosome mitochondrial RNA polymerase is required for transcription and replication. J. Biol. Chem. 277:16952-16959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grippo, J. F., A. Holmgren, and W. B. Pratt. 1985. Proof that the endogenous, heat-stable glucocorticoid receptor-activating factor is thioredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 260:93-97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz, R. A., and J. E. Jentoft. 1989. What is the role of the cys-his motif in retroviral nucleocapsid (NC) proteins? Bioessays 11:176-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klingbeil, M. M., S. A. Motyka, and P. T. Englund. 2002. Multiple mitochondrial DNA polymerases in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Cell 10:175-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klug, A., and J. W. Schwabe. 1995. Protein motifs. 5. Zinc fingers. FASEB J. 9:597-604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konieczny, I., K. S. Doran, D. R. Helinski, and A. Blasina. 1997. Role of TrfA and DnaA proteins in origin opening during initiation of DNA replication of the broad host range plasmid RK2. J. Biol. Chem. 272:20173-20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konieczny, I., and D. R. Helinski. 1997. The replication initiation protein of the broad-host-range plasmid RK2 is activated by the ClpX chaperone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14378-14382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konstantinov, Y., V. I. Tarasenko, and I. B. Rogozin. 2001. Redox modulation of the activity of DNA topoisomerase I from carrot (Daucus carota) mitochondria. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 377:82-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krauth-Siegel, R. L., and G. H. Coombs. 1999. Enzymes of parasite thiol metabolism as drug targets. Parasitol. Today 15:404-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lau, K. W., J. Ren, and M. Wu. 2000. Redox modulation of chloroplast DNA replication in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2:529-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, C., and P. T. Englund. 1997. A mitochondrial DNA primase from the trypanosomatid Crithidia fasciculata. J. Biol. Chem. 272:20787-20792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melendy, T., and D. S. Ray. 1989. Novobiocin affinity purification of a mitochondrial type II topoisomerase from the trypanosomatid Crithidia fasciculata. J. Biol. Chem. 264:1870-1876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melendy, T., C. Sheline, and D. S. Ray. 1988. Localization of a type II DNA topoisomerase to two sites at the periphery of the kinetoplast DNA of Crithidia fasciculata. Cell 55:1083-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montemartini, M., H. M. Kalisz, M. Kiess, E. Nogoceke, M. Singh, P. Steinert, and L. Flohe. 1998. Sequence, heterologous expression and functional characterization of a novel tryparedoxin from Crithidia fasciculata. Biol. Chem. 379:1137-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montemartini, M., E. Nogoceke, M. Singh, P. Steinert, L. Flohe, and H. M. Kalisz. 1998. Sequence analysis of the tryparedoxin peroxidase gene from Crithidia fasciculata and its functional expression in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 273:4864-4871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montemartini, M., P. Steinert, M. Singh, L. Flohe, and H. M. Kalisz. 2000. Tryparedoxin II from Crithidia fasciculata. Biofactors 11:65-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris, J. C., M. E. Drew, M. M. Klingbeil, S. A. Motyka, T. T. Saxowsky, Z. Wang, and P. T. Englund. 2001. Replication of kinetoplast DNA: an update for the new millennium. Int. J. Parasitol. 31:453-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muller, S., E. Liebau, R. D. Walter, and R. L. Krauth-Siegel. 2003. Thiol-based redox metabolism of protozoan parasites. Trends Parasitol. 19:320-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nogoceke, E., D. U. Gommel, M. Kiess, H. M. Kalisz, and L. Flohe. 1997. A unique cascade of oxidoreductases catalyses trypanothione-mediated peroxide metabolism in Crithidia fasciculata. Biol. Chem. 378:827-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park, J. S., M. Wang, S. J. Park, and S. H. Lee. 1999. Zinc finger of replication protein A, a non-DNA binding element, regulates its DNA binding activity through redox. J. Biol. Chem. 274:29075-29080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajavashisth, T. B., A. K. Taylor, A. Andalibi, K. L. Svenson, and A. J. Lusis. 1989. Identification of a zinc finger protein that binds to the sterol regulatory element. Science 245:640-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ray, D. S. 1987. Kinetoplast DNA minicircles: high-copy-number mitochondrial plasmids. Plasmid 17:177-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ray, D. S., and J. C. Hines. 1995. Disruption of the Crithidia fasciculata RNH1 gene results in the loss of two active forms of ribonuclease H. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:2526-2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reckenfelderbaumer, N., H. Ludemann, H. Schmidt, D. Steverding, and R. L. Krauth-Siegel. 2000. Identification and functional characterization of thioredoxin from Trypanosoma brucei brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 275:7547-7552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rigobello, M. P., M. T. Callegaro, E. Barzon, M. Benetti, and A. Bindoli. 1998. Purification of mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase and its involvement in the redox regulation of membrane permeability. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 24:370-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schagger, H., and G. Von Jagow. 1987. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166:368-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schuler, W., C. Dong, K. Wecker, and B. P. Roques. 1999. NMR structure of the complex between the zinc finger protein NCp10 of Moloney murine leukemia virus and the single-stranded pentanucleotide d(ACGCC): comparison with HIV-NCp7 complexes. Biochemistry 38:12984-12994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shapiro, T. A., and P. T. Englund. 1995. The structure and replication of kinetoplast DNA. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:117-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shlomai, J. 1994. The assembly of kinetoplast DNA. Parasitol. Today 10:341-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simpson, L., O. H. Thiemann, N. J. Savill, J. D. Alfonzo, and D. A. Maslov. 2000. Evolution of RNA editing in trypanosome mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6986-6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.South, T. L., and M. F. Summers. 1993. Zinc- and sequence-dependent binding to nucleic acids by the N-terminal zinc finger of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein: NMR structure of the complex with the Psi-site analog, dACGCC. Protein Sci. 2:3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stadtman, E. R., J. Moskovitz, B. S. Berlett, and R. L. Levine. 2002. Cyclic oxidation and reduction of protein methionine residues is an important antioxidant mechanism. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 234-235:3-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steenkamp, D. J. 2002. Trypanosomal antioxidants and emerging aspects of redox regulation in the trypanosomatids. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 4:105-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stuart, K., T. E. Allen, S. Heidmann, and S. D. Seiwert. 1997. RNA editing in kinetoplastid protozoa. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:105-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Summers, M. F., L. E. Henderson, M. R. Chance, J. W. Bess, Jr., T. L. South, P. R. Blake, I. Sagi, G. Perez-Alvarado, R. C. Sowder, D. R. Hare, et al. 1992. Nucleocapsid zinc fingers detected in retroviruses: EXAFS studies of intact viruses and the solution-state structure of the nucleocapsid protein from HIV-1. Protein Sci. 1:563-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun, Y., and L. W. Oberley. 1996. Redox regulation of transcriptional activators. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 21:335-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tetaud, E., C. Giroud, A. R. Prescott, D. W. Parkin, D. Baltz, N. Biteau, T. Baltz, and A. H. Fairlamb. 2001. Molecular characterisation of mitochondrial and cytosolic trypanothione-dependent tryparedoxin peroxidases in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 116:171-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Torri, A. F., and P. T. Englund. 1995. A DNA polymerase beta in the mitochondrion of the trypanosomatid Crithidia fasciculata. J. Biol. Chem. 270:3495-3497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Torri, A. F., and P. T. Englund. 1992. Purification of a mitochondrial DNA polymerase from Crithidia fasciculata. J. Biol. Chem. 267:4786-4792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Torri, A. F., T. A. Kunkel, and P. T. Englund. 1994. A beta-like DNA polymerase from the mitochondrion of the trypanosomatid Crithidia fasciculata. J. Biol. Chem. 269:8165-8171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Toukdarian, A. E., and D. R. Helinski. 1998. TrfA dimers play a role in copy-number control of RK2 replication. Gene 223:205-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tzfati, Y., H. Abeliovich, D. Avrahami, and J. Shlomai. 1995. Universal minicircle sequence binding protein, a CCHC-type zinc finger protein that binds the universal minicircle sequence of trypanosomatids. Purification and characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 270:21339-21345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tzfati, Y., H. Abeliovich, I. Kapeller, and J. Shlomai. 1992. A single-stranded DNA-binding protein from Crithidia fasciculata recognizes the nucleotide sequence at the origin of replication of kinetoplast DNA minicircles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6891-6895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tzfati, Y., and J. Shlomai. 1998. Genomic organization and expression of the gene encoding the universal minicircle sequence binding protein. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 94:137-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Urbaneja, M. A., B. P. Kane, D. G. Johnson, R. J. Gorelick, L. E. Henderson, and J. R. Casas-Finet. 1999. Binding properties of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein p7 to a model RNA: elucidation of the structural determinants for function. J. Mol. Biol. 287:59-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang, M., J. S. You, and S. H. Lee. 2001. Role of zinc-finger motif in redox regulation of human replication protein A. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 3:657-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Webster, K. A., H. Prentice, and N. H. Bishopric. 2001. Oxidation of zinc finger transcription factors: physiological consequences. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 3:535-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weiner, M. P., and G. L. Costa. 1994. Rapid PCR site-directed mutagenesis. PCR Methods Appl. 4:S131-S136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilkinson, S. R., N. J. Temperton, A. Mondragon, and J. M. Kelly. 2000. Distinct mitochondrial and cytosolic enzymes mediate trypanothione-dependent peroxide metabolism in Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Biol. Chem. 275:8220-8225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wray, W., T. Boulikas, V. P. Wray, and R. Hancock. 1981. Silver staining of proteins in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 118:197-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu, X., N. H. Bishopric, D. J. Discher, B. J. Murphy, and K. A. Webster. 1996. Physical and functional sensitivity of zinc finger transcription factors to redox change. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1035-1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xanthoudakis, S., and T. Curran. 1992. Identification and characterization of Ref-1, a nuclear protein that facilitates AP-1 DNA-binding activity. EMBO J. 11:653-665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xanthoudakis, S., G. Miao, F. Wang, Y. C. Pan, and T. Curran. 1992. Redox activation of Fos-Jun DNA binding activity is mediated by a DNA repair enzyme. EMBO J. 11:3323-3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu, C., and D. S. Ray. 1993. Isolation of proteins associated with kinetoplast DNA networks in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:1786-1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu, C. W., J. C. Hines, M. L. Engel, D. G. Russell, and D. S. Ray. 1996. Nucleus-encoded histone H1-like proteins are associated with kinetoplast DNA in the trypanosomatid Crithidia fasciculata. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:564-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.You, J. S., M. Wang, and S. H. Lee. 2000. Functional characterization of zinc-finger motif in redox regulation of RPA-ssDNA interaction. Biochemistry 39:12953-12958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]