Abstract

Dendritic cells (DC) of the CD11c+ myeloid phenotype have been implicated in the spread of scrapie in the host. Previously, we have shown that CD11c+ DC can cause a rapid degradation of proteinase K-resistant prion proteins (PrPSc) in vitro, indicating a possible role of these cells in the clearance of PrPSc. To determine the mechanisms of PrPSc degradation, CD11c+ DC that had been exposed to PrPSc derived from a neuronal cell line (GT1-1) infected with scrapie (ScGT1-1) were treated with a battery of protease inhibitors. Following treatment with the cysteine protease inhibitors (2S,3S)-trans-epoxysuccinyl-l-leucylamido-3-methylbutane (E-64c), its ethyl ester (E-64d), and leupeptin, the degradation of PrPSc was inhibited, while inhibitors of serine and aspartic and metalloproteases (aprotinin, pepstatin, and phosphoramidon) had no effect. An endogenous degradation of PrPSc in ScGT1-1 cells was revealed by inhibiting the expression of cellular PrP (PrPC) by RNA interference, and this degradation could also be inhibited by the cysteine protease inhibitors. Our data show that PrPSc is proteolytically cleaved preferentially by cysteine proteases in both CD11c+ DC and ScGT1-1 cells and that the degradation of PrPSc by proteases is different from that of PrPC. Interference by protease inhibitors with DC-induced processing of PrPSc has the potential to modify prion spread, clearance, and immunization in a host.

Prion diseases are neurodegenerative diseases that affect humans (e.g., Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease) as well as animals (e.g., scrapie, bovine spongiform encephalopathy, and chronic wasting disease). At the biochemical level, these diseases are characterized by the conversion of a normal cellular prion protein (PrPC) into an abnormal isoform that is enriched in β-structures and is partially resistant to proteinase K (PrPSc) (41, 42). Prion-affected tissues show accumulation of PrPSc, and this may be paralleled by neuronal vacuolization and nerve cell death. Although prion diseases are associated with an accumulation of PrPSc in the brain, indirect evidence has recently been obtained that PrPSc can be degraded within an infected cell. Such evidence derives from the treatment of scrapie-infected neuronal cells, the neuroblastoma N2a cell line, with antibodies against PrPC (19, 40). This treatment can cause clearance of PrPSc from the cultured cells, and it is suggested that this is caused by inhibition of the formation of new PrPSc concomitant with degradation of previously formed PrPSc. From in vitro and in vivo studies, there is also indirect evidence that macrophages may be involved in the degradation of PrPSc (2, 6).

We have previously described that CD11c+ dendritic cells (DC) can efficiently degrade PrPSc presented to them by scrapie-infected gonadotropin-releasing cells (GT1-1 cells) in vitro (29). This raises the questions of whether certain proteases in DC are particularly efficient in the degradation of PrPSc and whether these proteases are distinct from those that are involved in degradation of endogenous PrPSc in GT1-1 cells. Using a battery of different protease inhibitors, we found that PrPSc is preferentially degraded by cysteine proteases at an acidic pH in both DC and scrapie-infected GT1-1 (ScGT1-1) cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

GT1-1 cell culture and scrapie infection.

GT1-1 cells, a subtype of immortalized mouse gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons (36), were a generous gift from Pamela Mellon (University of California, San Francisco). The cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (4.5 g of glucose per liter) containing Glutamax I and supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 5% heat-inactivated horse serum (HS), and 50 U of penicillin-streptomycin per ml (all from Gibco-BRL, Paisley, United Kingdom). The GT1-1 cells were infected with mouse-adapted scrapie by incubation with a 0.1% homogenate of mouse brains infected with the Rocky Mountain Laboratory strain of scrapie (the homogenates were obtained as a generous gift from Stanley B. Prusiner, University of California, San Francisco) at 30°C. After 3 days, the medium was changed and the temperature was raised to 37°C. Western blotting confirmed the presence of protease-resistant PrPSc after six passages.

Differentiation and isolation of CD11c+ DC.

Murine bone marrow-derived DC were obtained from the femur and tibia bone marrow of C57BL/6 mice (obtained from the Microbiology and Tumor Biology Center, Karolinska Institutet) essentially as described by Inaba et al. (24). Briefly, after removal of small pieces of bone and debris, the cells were pelleted and resuspended in DMEM (4.5 g of glucose/liter) with Glutamax I, 15% FBS, and 50 U of penicillin-streptomycin per ml to which 10 ng of recombinant murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor per ml and 10 ng of murine interleukin-4 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, N.Y.) per ml were added. The cells were grown in 5% CO2 at 37°C and replated after 7 days. To obtain pure DC, the cells from the bone marrow cultures were affinity purified with magnetic cell separation (MACS) CD11c+ magnetic micro beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Protease inhibitors.

The inhibitors used were leupeptin hydrochloride, (2S,3S)-trans-epoxysuccinyl-l-leucylamido-3-methylbutane (E-64c), (2S,3S)-trans-epoxysuccinyl-l-leucylamido-3-methylbutane ethyl ester (E-64d), aprotinin, and pepstatin A (all from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie, Steinhem, Germany; Sigma catalog numbers L-9783, E-0514, E-8640, A-1153, and P-4265, respectively) and phosphoramidon (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Pepstatin A was diluted in 70% ethanol to a 1.6 mM stock solution and stored at −70°C. All other inhibitors were made up to a stock concentration of 15 mM and stored at −20°C. Leupeptin, aprotinin, and phosphoramidon were all diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). E-64c and E-64d were made up in 50% ethanol.

Treatment of cultures with protease inhibitors.

Cocultures of DC and ScGT1-1 cells were established by growing ScGT1-1 cells overnight in 10-mm tissue culture dishes (Corning Inc., Corning, N.Y.) to a concentration of 106 cells/dish. CD11c+-sorted DC were then added at a concentration of 106 cells/dish, giving an approximate DC:GT1-1 cell ratio of 1:1. The cells were incubated in AIM-V serum-free medium (Gibco-BRL) to avoid interference with serum proteases, supplemented with 10 ng of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (PeproTech) per ml. To some of these cocultures and to some ScGT1-1 cells, protease inhibitors were added in 2 ml of AIM-V medium to a final concentration of 15 μM, while others were kept as controls. The cells were then incubated for 48 h. The medium was carefully removed, and the adherent cells were lysed in the cell culture dishes with 100 μl of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% Triton X-100) on ice without previous rinsing. Rinsing was avoided in order to retain loosely attached cells in the culture. To collect free-floating DC from the DC-ScGT1-1 coculture, the cell medium was sampled and spun at 400 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were removed. The resulting pellets were added to the corresponding cell lysates in each centrifuge tube, and insoluble debris was removed by centrifugation at 16,000 × g. All the protease inhibitors that had been used to treat the cell cultures were added to the lysis buffer as a cocktail (15 μM each) to correct for any possible inhibition of proteinase K (a serine protease).

Treatment with pentosan polysulfate.

ScGT1-1 cells were seeded in 10-mm cell culture dishes and grown in DMEM (4.5 g of glucose/liter) containing Glutamax I supplemented with 5% FBS, 5% HS, and 50 U of penicillin-streptomycin per ml for 24 h. This medium was exchanged for AIM-V medium containing 5 μg of pentosan polysulfate (Sigma, P-8275) per ml with and without 15 μM leupeptin or 15 μM E-64d, after which the cells were grown for an additional 48 h and then lysed.

Exposure of homogenates of ScGT1-1 cells to living DC.

ScGT1-1 cells were harvested and diluted in sterile water at a concentration of 105 cells/μl, frozen and thawed twice, homogenized with a 27-gauge needle, and spun for 2 min at 400 × g to remove debris; 30 μl of homogenate was added to each dish of DC cultured in AIM-V medium, 1.2 × 106 cells/dish. After incubation for 12 h at 37°C, the medium was removed and spun for 2 min at 400 × g to sample free-floating DC, which were then reintroduced to the dishes. Then 50 μM leupeptin was added to some of the dishes at time zero, while others were kept as controls. At 0 and 48 h, the cell medium was removed and spun at 400 × g for 2 min. Attaching DC were then lysed with the lysis buffer used for Western blotting (see above), and the pellets from the spun cell medium were added. The lysates were then mixed with loading buffer, boiled, and analyzed by Western blotting, as described below.

Incubation of lysates at different pHs.

ScGT1-1 cells and purified DC were harvested, spun at 1,500 × g, diluted in PBS separately at a concentration of 2 × 107 cells/ml, and then frozen at −70°C. The frozen cell homogenates were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100). The ScGT1-1 cell lysates were divided into 12 aliquots, and to eight of these, lysates of DC (ScGT1-1/DC ratio, 1:2) were added. Leupeptin (15 μM) was added to four of the ScGT1-1/DC lysates. Lysis buffer was added to adjust the volume in the ScGT1-1 lysates without DC. The pHs of the lysates were adjusted to 5.5 or 7.8 by adding 10 μl of 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5) or of 1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.8), respectively, to a total of 15 μl of ScGT1-1/DC lysates. All the samples were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After incubation, the samples were mixed with loading buffer and boiled.

Generation of siRNA.

A 21-nucleotide short interfering RNA (siRNA) duplex (sense, UUUAGGAGAGCCAAGCAGAUU) corresponding to positions 123 to 143 (GenBank accession number NM_011170.1) on the mRNA for PrPC, was designed as recommended (18), with uridine residues in the two-nucleotide overhangs. DNA templates for the chosen siRNA, containing a region complementary to the T7 promoter primer (CCTGTCTC) at the 3′ end, were ordered from Invitrogen (Paisley, United Kingdom). siRNAs were synthesized by in vitro transcription with the Silencer siRNA construction kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Ambion, Austin, Tex.). siRNAs were labeled with indocarbocyanine (Cy3) with the Silencer siRNA labeling kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Ambion).

Transfection of cells with siRNA.

ScGT1-1 cells were plated on 35-mm cell culture dishes in regular cell culture medium (described above) without antibiotics. About 24 h after plating, when they had reached 30% confluence, the cells were transfected with siRNA (final concentration, 20 nM; final volume, 1 ml) with Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) (3 μl of reagent/ml of medium) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transfection was carried out under serum-free conditions in Optimem I (Gibco-BRL) without antibiotics. At 4 h after transfection, 500 μl of DMEM with 15% FBS and 15% HS was added to the cell culture dishes (final concentrations, 5% FBS and 5% HS; final volume, 1.5 ml). The cells were analyzed by Western blotting and immunofluorescence with Fab D13, obtained from Stanley B. Prusiner (32, 57), 1 to 10 days after transfection, to determine the presence of PrPC and PrPSc. Cultures analyzed by Western blotting were standardized to the same amount of protein before proteinase K (PK) treatment. Transfection efficiency was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy. Cells transfected with Cy3-labeled siRNA were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma) (final concentration, 5 μg/ml) in PBS for 10 min to visualize cell nuclei. The cells were rinsed twice with PBS, fixed in 10% formalin (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) in PBS, rinsed again in PBS, and finally mounted in glycerol (Merck).

Western immunoblotting.

Before blotting, the protein contents of the lysates were determined with the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad) and spectroscopy (Ultrospec Plus; Pharmacia LKB, Cambridge, United Kingdom) at 595 nm according to the manufacturer's instructions. The lysate was then split into two aliquots. One aliquot was treated with 20 μg of PK (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) per ml at 37°C for 40 min and then incubated with 3 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma) to stop the reaction. The other aliquot was not PK treated. The samples were boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer, loaded on NuPAGE 12% Bis-Tris gels with MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid)-SDS running buffer, and resolved at 200 V according to the manufacturers' instructions (Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to Immobilon-PSQ transfer membranes (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) at 35 V for 3 h, blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma), and incubated with recombinant Fab D13, 1 μg/ml, followed by the secondary goat anti-human F(ab)2-peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) at 0.16 μg/ml. Detection was performed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Plus; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

Immunofluorescence.

The cells grown on the cell culture dishes were fixed in 10% formalin (Merck KGaA) for 30 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma, St Louis, Mo.) in PBS for 5 min, and treated with 3 M guanidinium thiocyanate (Merck-Schuchardt, Hohenbrunn, Germany) for detection of PrPSc (53) for 5 min. After blocking with 5% BSA (Sigma) for 40 min, the cells were incubated with the primary antibody (Fab D13 diluted in PBS containing 5% BSA to 3.5 μg/ml) overnight at 4°C, followed by addition of Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-human immunoglobulin G (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, Pa.) at a concentration of 7.5 μg/ml. Double labeling with Fab D13 and a rat monoclonal immunoglobulin G, LAMP-1 (1D4B), 0.2 μg/ml, or a goat polyclonal transferrin receptor antibody (CD71) (both obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.), 4 μg/ml, was performed. Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rat immunoglobulin G (Jackson Immunoresearch), 15 μg/ml, and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated donkey anti-goat immunoglobulin G, 30 μg/ml, respectively, served as secondary antibodies. DC were visualized with an anti-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II antibody purified from the supernatant of the hybridoma M5/114.15.2 (BD Pharmingen), 10 μg/ml, with Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rat immunoglobulin G, 15 μg/ml, as a secondary antibody. The cells were rinsed in PBS with 1% NH4Cl (Sigma) between each treatment and mounted in glycerol with 2.5% diazabicyclanooctane (Sigma).

RESULTS

Effects of protease inhibitors on degradation of PrPSc by DC.

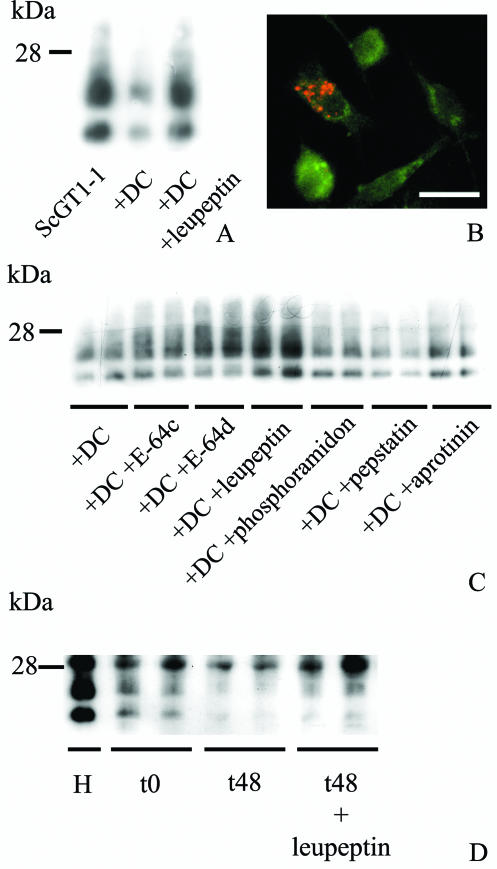

In the first series of experiments, we determined whether DC-mediated degradation of exogenous PrPSc could be blocked by inhibition of proteases. For this experiment we used leupeptin, which is a commonly used protease inhibitor. As described previously (29), when purified CD11c+ DC were added to ScGT1-1 cells and cocultivated for 48 h, the latter were engulfed by the DC, and this was followed by a marked reduction in the intensity of PK-resistant PrP compared to the unexposed ScGT1-1 cells (Fig. 1A). The amount of PK-resistant PrP was also decreased after 48 h in coculture compared to that at time zero (data not shown). When the cocultures of ScGT1-1 and DC were treated with leupeptin, degradation was impeded (Fig. 1A). In such cocultures, the accumulation of PrP-immunopositive material was seen in the cytoplasm of the DC after guanidine thiocyanate treatment (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Effect of protease inhibitors on DC-induced degradation of PrPSc derived from ScGT1-1 cells. (A) Immunoblot showing levels of PK-resistant PrP in ScGT1-1 cells, ScGT1-1 cells after exposure to DC, and DC combined with leupeptin treatment and (B) DC (green) after 24 h of coculture with ScGT1-1 cells in the presence of leupeptin. Note the presence of intracellular PrPSc (red). (C) Levels of PK-resistant PrP from ScGT1-1 cells exposed to DC for 48 h and after treatment of these cocultured cells with E-64c, E-64d, leupeptin, phosphoramidon, pepstatin, and aprotinin for 48 h. (D) Levels of PrPSc after incubation of ScGT1-1 homogenate (H) with DC in the absence and presence of leupeptin at 0 and 48 h. The duplicates represent different cultures.

To determine whether any family of proteases is particularly involved in PrPSc degradation, the cocultures of ScGT1-1 cells and DC were then treated with protease inhibitors that block the catalytic activities of cysteine (E-64c, E-64d, and leupeptin), aspartic (pepstatin), serine (leupeptin and aprotinin), and metalloproteases (phosphoramidon). E-64c, E-64d, and leupeptin prevented the decrease in the intensity of the PK-resistant bands (Fig. 1C). Aprotinin, pepstatin, and phosphoramidon had no effect on the DC-mediated degradation of exogenous PrPSc (Fig. 1C). These experiments show that the DC-mediated degradation of exogenous PrPSc can be impeded by some but not all protease inhibitors. To further show that the inhibitors had a direct effect on DC, homogenates of the ScGT1-1 cells were added to living DC. After 48 h of incubation most of the PK-resistant PrP had disappeared. This degradation could also be inhibited by leupeptin (Fig. 1D).

Effect of pH on DC-mediated degradation of PK-resistant PrP in vitro.

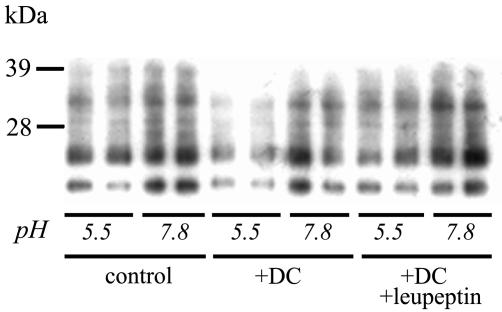

To determine whether the PrPSc-degrading activity of the protease inhibitors is pH dependent, lysates of DC were coincubated with lysates of ScGT1-1 cells at different pHs with and without leupeptin. Since CD11c+ DC in culture do not express PrPC (29), lysates from these cells have no intrinsic PrP that could interfere with the detection of PrP derived from ScGT1-1 cells. During the incubation period, most of the full-length PrP was degraded, but bands corresponding to the size of the PK-resistant PrP remained in lysates of the ScGT1-1 cells (Fig. 2). The intensity of these bands decreased after coincubation with the DC lysates at pH 5.5, and this decreased intensity was inhibited by leupeptin. PrPSc was not degraded at pH 7.8, which implies that degrading proteases in DC require an acidic environment in the cell.

FIG. 2.

Effect of pH on PrPSc degradation. Immunoblot showing levels of PrPSc after incubation of ScGT1-1 lysates at pH 5.5 and 7.8 with the addition of DC lysates and DC lysates combined with leupeptin for 1 h. Note the decrease in PrP intensity at pH 5.5 after incubation with DC lysates, which was not seen when leupeptin was added. The duplicates represent different samples.

Effect of RNA interference on PrP in ScGT1-1 cultures.

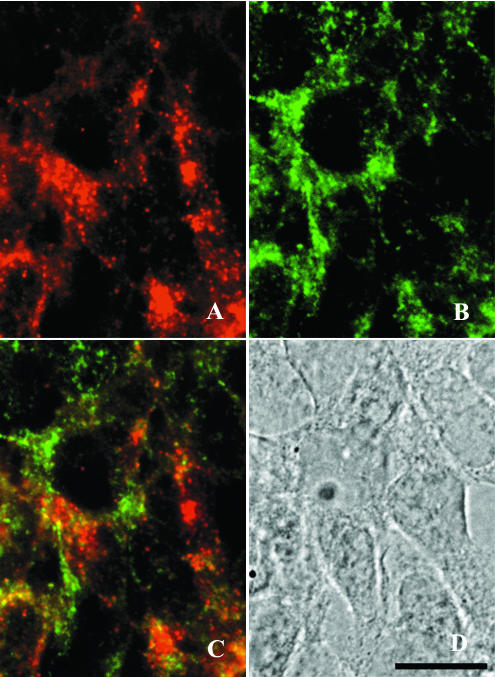

In order to verify that endogenous degradation of PrPSc occurs in ScGT1-1 cells, these cells were treated with an siRNA directed to the mRNA for PrPC (to stop PrP synthesis) and harvested daily for 10 days after siRNA transfection. Transfection efficiency was high, as evaluated by fluorescence microscopy showing that almost all cells contained Cy3-labeled siRNAs (Fig. 3A). Subsequently, treatment with siRNA caused a reduction in PrPC and clearance of PrPSc, as shown by Western blotting (Fig. 3B). Immunofluorescence also showed reduced levels of PrPSc in siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 3D) compared to untreated controls (Fig. 3C). No reduction in PrP expression was seen in mock-transfected cells (data not shown). These data show that there is an endogenous clearance of PrPSc in infected cells, and this result tallies with a recently published observation on N2a and GT1-1 cells treated with chemically synthesized siRNAs (13).

FIG. 3.

Effect of PrPC RNA interference on the occurrence of PrPC and PrPSc in ScGT1-1 cells. (A) ScGT1-1 cells were treated with Cy3-labeled siRNAs (red), showing transfection of the majority of the cells; cell nuclei are shown in blue. (B) Immunoblot showing reduction of PrPC and loss of PK-resistant PrP 7 days after PrPC siRNA treatment of ScGT1-1 cells. a, untreated cells; b, PrPC siRNA-treated cells. −, non-PK-treated samples; +, PK-treated samples. (C and D) PrP immunofluorescence of untreated (C) and PrPC siRNA-treated (D) ScGT1-1 cells. The cells in both panels C and D were treated with guanidine thiocyanate prior to immunostaining to expose PrPSc. Bars, 20 μm.

Effect of protease inhibitors and pentosan polysulfate on PrP in ScGT1-1 and GT1-1 cells.

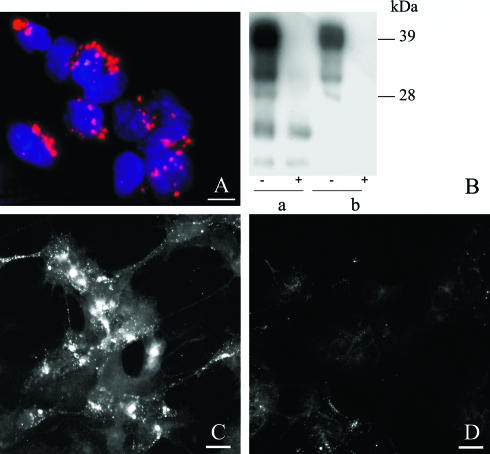

In order to analyze whether the protease inhibitors can affect the level of PrPSc within ScGT1-1 cells, these cells were treated with the different protease inhibitors for 48 h. There were no overt cytopathic or cytostatic effects of the treatment. Lysates from cell cultures exposed to E-64c, E-64d, and leupeptin subjected to Western blotting showed an increased intensity of PK-resistant PrP (Fig. 4A). No increase in PrPSc was seen in ScGT1-1 cells treated with aprotinin, pepstatin, or phosphoramidon.

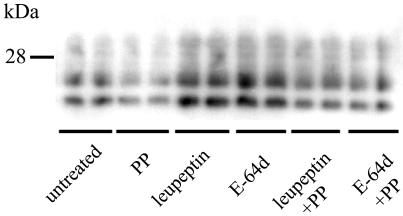

FIG. 4.

Presence of PrPSc in ScGT1-1 cell cultures after treatment with protease inhibitors. (A) Immunoblot showing the presence of PK-resistant PrP in ScGT1-1 cell cultures untreated or treated with E-64c, E-64d, leupeptin, aprotinin, pepstatin, and phosphoramidon for 48 h. (B and C) PrP immunofluorescence with Fab D13 of (B) untreated and (C) leupeptin-treated ScGT1-1 cells. Cells were exposed to guanidine thiocyanate prior to immunostaining. Bars, 20 μm.

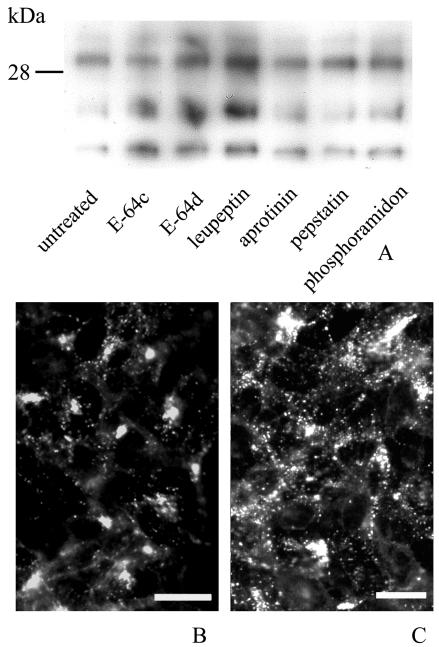

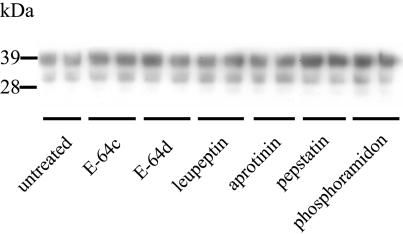

Immunolabeling of guanidine thiocyanate-treated cells with the anti-PrP antibody showed immunopositive punctate structures in more than 80% of the ScGT1-1 cells. These speckled accumulations occurred often as small, distinct clusters in the cytoplasm of the cells (Fig. 4B). After treatment with leupeptin and E-64d, the immunopositive punctate structures were more spread throughout the cytoplasm of the cells (Fig. 4C), which may reflect an increase in the number of these structures and/or increased accumulation of PrPSc within them during their transport in the cell. Previous ultrastructural studies show that scrapie accumulates in lysosomes, residual bodies, and numerous compartments not yet identified (35). In agreement with this result, we found a partial colocalization of D13-positive materials and LAMP-1, a lysosome-associated membrane protein, after treatment with E-64d (Fig. 5). No colocalization was apparent between D13 and the transferrin receptor, which labeled the plasma membranes (data not shown). However, a more detailed immunocytochemical analysis of the compartments for PrP accumulation after treatment with protease inhibitors requires ultrastructural studies.

FIG. 5.

Double immunolabeling of (A) PrP and (B) LAMP-1 in ScGT1-1 cells treated with E-64d. Cells were exposed to guanidine thiocyanate prior to immunolabeling. A merged image of the red and green channels shows partial colocalization of PrP and LAMP-1 (C). A bright-field micrograph of the cells is also shown (D). Bar, 20 μm.

To determine that the levels of PrPSc observed were not caused by increased formation of PrPSc, the cells were incubated with pentosan polysulfate, a polyanion known to inhibit scrapie formation (7, 9). When PrPSc formation was inhibited by this treatment, leupeptin and E-64d still enhanced the intensity of PrPSc (Fig. 6) indicating that no increased synthesis of PrPSc was induced by the protease inhibitors. In addition, to determine that the increase in PrPSc induced by E-64c, E-64d, and leupeptin did not reflect effects on PrPC, uninfected cells were treated with the inhibitors. There was a tendency to an increase in the level of PrPC after treatment with E-64c, E-64d, and leupeptin but, in contrast to the experiments with PrPSc, also after treatment with the other inhibitors (Fig. 7).

FIG. 6.

Immunoblot showing levels of PK-resistant PrP in ScGT1-1 cells after treatment with pentosan polysulfate (PP), leupeptin, or E-64d or combinations of pentosan polysulfate and leupeptin or E-64d. The cultures were treated for 48 h, and the duplicates represent different cultures.

FIG. 7.

Immunoblot showing the effects of protease inhibitors on PrPC in uninfected GT1-1 cells after treatment with protease inhibitors. The cultures were treated for 48 h, and the duplicates represent different cultures.

Taken together, these observations suggest that cysteine proteases are involved in the endogenous proteolytic cleavage of PrPSc in ScGT1-1 cells, similar to the degradation of exogenous PrPSc by DC.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that degradation of PrPSc by CD11c+ DC and ScGT1-1 cells can be interfered with by protease inhibitors and that this degradation requires an acidic environment. It also shows that the effects of protease inhibitors on degradation of PrPSc and PrPC differ.

We have recently shown that CD11c+ DC in culture can degrade exogenous PrPSc derived from phagocytosed ScGT1-1 cells (29). Here we demonstrate that this degradation can be inhibited by treatment with the two cysteine protease inhibitors, E-64c and E-64d, and with leupeptin. Leupeptin inhibits both cysteine and serine proteases (15, 43), but since the serine protease inhibitor aprotinin had no such effect, it is likely that the effect of leupeptin on PrPSc degradation reflects inhibition of cysteine protease activity. The observation that the RNA interference with PrP could clear PrPSc from the cultures demonstrates an endogenous turnover of PrPSc in ScGT1-1 cells, which is in agreement with recent observations of clearance of PrPSc from scrapie-infected N2a cells following treatment with PrP-binding antibodies (19, 40). The half-life of PrPSc is probably much longer than that of PrPC (3), which has a half-life estimated to 3 to 6 h in N2a cells (3, 8) and 1.5 to 2 h in primary splenocyte and cerebellar granule cell cultures (39).

Part of the PrPC bound to cell membranes may be cleaved by serum phospholipases and/or metalloenzymes and released from the cell surface, whereas the rest may be targeted for intracellular degradation (39, 56). Within a cell, PrPC may be degraded in two consecutive steps, with a 17-kDa unglycosylated intermediate (52, 55). In a study of human PrPC degradation with protease inhibitors on lysates from cerebral and cerebellar cortex, the metal-chelating agents EDTA and EGTA and inhibitors of cysteine proteases were effective in inhibiting PrPC degradation (26). In the present study, we found no signs of selective inhibition of PrPC degradation by cysteine proteases. These results therefore indicate that the cleavage sites available for proteolysis of PrPSc, the degradation of which was inhibited only by cysteine protease inhibitors, are more restricted than those available for proteolysis of PrPC.

Cysteine proteases represent a class of multifunctional proteolytic enzymes that can function both in lysosomal degradations (cathepsins) and in programmed cell death (caspases) (28). In the present study, we found that the cysteine proteases degraded PrPSc at an acidic pH, which indicates that the PrPSc-degrading activity occurs in endosomal and lysosomal compartments. Thus, the degradation of PrPSc and of PrPC seems to employ similar compartments in the cell (52) and of the N-terminal trimming of PrPSc by acid proteases into a 19-kDa (unglycosylated) fragment that occurs soon after its formation in scrapie-infected N2a and HaB cells (10, 51).

Ultrastructurally, PrPSc has been identified in vesicles and lysosomes in both N2a and hamster brain-derived cells (35, 53). The degradation of bona fide PrPSc, as observed in the present study, therefore seems to occur in compartments distinct from that of the misfolded prion-like PrP species that can accumulate in the cytosol upon treatment with proteasome inhibitors (30, 58) and cyclosporin (11). The mammalian cysteine proteases that are localized to the lysosomal compartments are known as cathepsins, although not all cathepsins are cysteine proteases (for reviews, see references 28 and 34).

Since various cell types differ in their protease contents, the observation that cysteine proteases are selectively involved in PrPSc degradation may be relevant for understanding the susceptibility of particular cell types to prion infections. Thus, a cell's proteolytic enzyme content could be one of the factors that determine the susceptibility of a cell to prion infection (25). It would therefore be of interest to identify the individual lysosomal cysteine protease(s) that is active in PrPSc degradation and to analyze whether cells with various susceptibilities to scrapie infection differ in their content of such enzymes. For instance, differences in catalytic properties may account for the observation of reduced levels of PrPSc in scrapie-infected N2a cells following treatment with leupeptin and E-64 (16) as opposed to the increased levels in GT1-1 cells. Recently, an upregulation of cathepsin B and cathepsin L activities was described in scrapie-infected N2a cells (59). Whether protease inhibitors can be used to improve the susceptibility of cells to prion infection or to stabilize an already established prion infection remains to be seen. One strategy could be to use cathepsin knockout mice (14, 20) and to study their susceptibility to prion infections.

CD11c+ DC have been implicated in facilitating the spread of scrapie to the nervous system from peripheral sites of inoculation (1, 23). These observations may seem paradoxical in view of our finding that this type of DC in culture can efficiently degrade PrPSc. However, proteolytic processing of PrPSc in CD11c+ DC could conceivably generate fragments of PrPSc that are still infectious. The smallest identified infectious PrPSc molecule is a 106-amino-acid prion protein expressed in transgenic mice lacking wild-type PrPC. This is a prion protein with two deletions, an N-terminal truncation and an internal deletion, designated a miniprion, or PrP106 (48). In addition, a subset of residues 89 to 140 spontaneously induce protease resistance in synthetic PrP (49). The minimum PrP peptide size required to induce infectivity in wild-type PrP is not yet known, but should such fragments resist an initial proteolytic cleavage of PrPSc by cysteine proteases, fragments that retain infectivity may be generated. Although it seems unlikely that such fragments could be transmitted to neighboring cells in context with major histocompatibility complex class II molecules, they might be exported to the cell surface by other mechanisms or be released into the environment by so-called exosomes (38, 54). Processing by DC could also increase the infectivity of ingested prions by inducing alterations beyond proteolysis. For instance, endosomal hydrolases could digest glycans such as the N-linked sugars that are attached to PrPSc. The influence of such chemical modifications on prions remains to be determined. Low pH within DC endosomes as well as the hydrolysis by lipases of membranes attached to PrPSc could also encourage conformational alterations of PrPSc or disperse it into smaller aggregates, with a concomitant increase in effective prion infectivity.

Although these cultured CD11c+ DC never showed levels of PrPC comparable to those of GT1-1 cells, they could still express PrPC at levels high enough to support replication of PrPSc in the in vivo situation (5, 21, 47), as has been suggested for the facilitation of prion spread by follicular DC (4, 33, 37). Prion spread to the peripheral nervous system may be facilitated by the fact that CD11c+ DC are in close contact with peripheral nerve fibers in the epithelium (17, 22), which is in contrast to follicular DC, which are of a different origin and have different functions than the CD11c+ DC (12). In fact, in his original study, Langerhans described connections of the new type of cells in dermal epithelium (the DC that were later given his name) to nerve fibers, and he believed that the cells were of neuronal origin (27).

The foregoing observation of efficient cysteine protease-dependent degradation of PrPSc by DC may relate to recent studies on the effect of prion peptide immunization on PK-resistant PrP (46). Immunization with peptides predicted to fit the major histocompatibility complex class II binding motif causes a marked reduction in the level of PK-resistant PrP in scrapie-infected tumors transplanted into mice without affecting PrPC or tumor growth. One possible explanation for this is that degradation of PrPSc occurs in vivo and that this degradation can be increased by immunization. Immunization with recombinant PrP delays the onset of prion disease in mice (45), and stimulation of innate immunity prolongs the survival of scrapie-infected mice even as a postexposure treatment (31, 44, 50). Knowledge of the mechanisms involved in proteolytic cleavage of PrPSc serves as a foundation for therapies employing immune modulation of prion diseases or the design of specific protease activators for the degradation of PrPSc.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council 04480, EC QLRT-2001-01628, and Stiftelsen Sigurd och Elsa Goljes Minne.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aucouturier, P., F. Geissmann, D. Damotte, G. P. Saborio, H. C. Meeker, R. Kascsak, R. I. Carp, and T. Wisniewski. 2001. Infected splenic dendritic cells are sufficient for prion transmission to the CNS in mouse scrapie. J. Clin. Investig. 108:703-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beringue, V., M. Demoy, C. I. Lasmezas, B. Gouritin, C. Weingarten, J. P. Deslys, J. P. Andreux, P. Couvreur, and D. Dormont. 2000. Role of spleen macrophages in the clearance of scrapie agent early in pathogenesis. J. Pathol. 190:495-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borchelt, D. R., M. Scott, A. Taraboulos, N. Stahl, and S. B. Prusiner. 1990. Scrapie and cellular prion proteins differ in their kinetics of synthesis and topology in cultured cells. J. Cell Biol. 110:743-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, K. L., K. Stewart, D. L. Ritchie, N. A. Mabbott, A. Williams, H. Fraser, W. I. Morrison, and M. E. Bruce. 1999. Scrapie replication in lymphoid tissues depends on prion protein-expressing follicular dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 5:1308-1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burthem, J., B. Urban, A. Pain, and D. J. Roberts. 2001. The normal cellular prion protein is strongly expressed by myeloid dendritic cells. Blood 98:3733-3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carp, R. I., and S. M. Callahan. 1982. Effect of mouse peritoneal macrophages on scrapie infectivity during extended in vitro incubation. Intervirology 17:201-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caughey, B., K. Brown, G. J. Raymond, G. E. Katzenstein, and W. Thresher. 1994. Binding of the protease-sensitive form of PrP (prion protein) to sulfated glycosaminoglycan and Congo red. J. Virol. 68:2135-2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caughey, B., R. E. Race, D. Ernst, M. J. Buchmeier, and B. Chesebro. 1989. Prion protein biosynthesis in scrapie-infected and uninfected neuroblastoma cells. J. Virol. 63:175-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caughey, B., and G. J. Raymond. 1993. Sulfated polyanion inhibition of scrapie-associated PrP accumulation in cultured cells. J. Virol. 67:643-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caughey, B., G. J. Raymond, D. Ernst, and R. E. Race. 1991. N-terminal truncation of the scrapie-associated form of PrP by lysosomal protease(s): implications regarding the site of conversion of PrP to the protease-resistant state. J. Virol. 65:6597-6603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen, E., and A. Taraboulos. 2003. Scrapie-like prion protein accumulates in aggresomes of cyclosporin A-treated cells. EMBO J. 22:404-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cyster, J. G., K. M. Ansel, K. Reif, E. H. Ekland, P. L. Hyman, H. L. Tang, S. A. Luther, and V. N. Ngo. 2000. Follicular stromal cells and lymphocyte homing to follicles. Immunol Rev. 176:181-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daude, N., M. Marella, and J. Chabry. 2003. Specific inhibition of pathological prion protein accumulation by small interfering RNAs. J. Cell Sci. 116:2775-2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deussing, J., W. Roth, P. Saftig, C. Peters, H. L. Ploegh, and J. A. Villadangos. 1998. Cathepsins B and D are dispensable for major histocompatibility complex class II-mediated antigen presentation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:4516-4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deutscher, M. P. 1990. Maintaining protein stability. Methods Enzymol. 182:83-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doh-Ura, K., T. Iwaki, and B. Caughey. 2000. Lysosomotropic agents and cysteine protease inhibitors inhibit scrapie-associated prion protein accumulation. J. Virol. 74:4894-4897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egan, C. L., M. J. Viglione-Schneck, L. J. Walsh, B. Green, J. Q. Trojanowski, D. Whitaker-Menezes, and G. F. Murphy. 1998. Characterization of unmyelinated axons uniting epidermal and dermal immune cells in primate and murine skin. J. Cutan. Pathol. 25:20-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elbashir, S. M., J. Harborth, K. Weber, and T. Tuschl. 2002. Analysis of gene function in somatic mammalian cells using small interfering RNAs. Methods 26:199-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enari, M., E. Flechsig, and C. Weissmann. 2001. Scrapie prion protein accumulation by scrapie-infected neuroblastoma cells abrogated by exposure to a prion protein antibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:9295-9299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felbor, U., B. Kessler, W. Mothes, H. H. Goebel, H. L. Ploegh, R. T. Bronson, and B. R. Olsen. 2002. Neuronal loss and brain atrophy in mice lacking cathepsins B and L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7883-7888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford, M. J., L. J. Burton, R. J. Morris, and S. M. Hall. 2002. Selective expression of prion protein in peripheral tissues of the adult mouse. Neuroscienc 113:177-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosoi, J., G. F. Murphy, C. L. Egan, E. A. Lerner, S. Grabbe, A. Asahina, and R. D. Granstein. 1993. Regulation of Langerhans cell function by nerves containing calcitonin gene-related peptide. Nature 363:159-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang, F. P., C. F. Farquhar, N. A. Mabbott, M. E. Bruce, and G. G. MacPherson. 2002. Migrating intestinal dendritic cells transport PrP(Sc) from the gut. J. Gen. Virol. 83:267-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inaba, K., M. Inaba, N. Romani, H. Aya, M. Deguchi, S. Ikehara, S. Muramatsu, and R. M. Steinman. 1992. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J. Exp. Med. 176:1693-1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeffrey, M., S. Martin, and L. Gonzalez. 2003. Cell-associated variants of disease-specific prion protein immunolabelling are found in different sources of sheep transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. J. Gen. Virol. 84:1033-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jimenez-Huete, A., P. M. Lievens, R. Vidal, P. Piccardo, B. Ghetti, F. Tagliavini, B. Frangione, and F. Prelli. 1998. Endogenous proteolytic cleavage of normal and disease-associated isoforms of the human prion protein in neural and non-neural tissues. Am. J. Pathol. 153:1561-1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langerhans, P. 1868. Ueber die nerven der menschlichen haut. Virchows Arch. Pathol. Anat. Physiol. 44:325-337. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leung-Toung, R., W. Li, T. F. Tam, and K. Karimian. 2002. Thiol-dependent enzymes and their inhibitors: a review. Curr. Med. Chem. 9:979-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luhr, K. M., R. P. Wallin, H. G. Ljunggren, P. Low, A. Taraboulos, and K. Kristensson. 2002. Processing and degradation of exogenous prion protein by CD11c+ myeloid dendritic cells in vitro. J. Virol. 76:12259-12264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma, J., R. Wollmann, and S. Lindquist. 2002. Neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration when PrP accumulates in the cytosol. Science 298:1781-1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manuelidis, L., and Z. Y. Lu. 2003. Virus-like interference in the latency and prevention of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:5360-5365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsunaga, Y., D. Peretz, A. Williamson, D. Burton, I. Mehlhorn, D. Groth, F. E. Cohen, S. B. Prusiner, and M. A. Baldwin. 2001. Cryptic epitopes in N-terminally truncated prion protein are exposed in the full-length molecule: dependence of conformation on pH. Proteins 44:110-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McBride, P. A., P. Eikelenboom, G. Kraal, H. Fraser, and M. E. Bruce. 1992. PrP protein is associated with follicular dendritic cells of spleens and lymph nodes in uninfected and scrapie-infected mice. J. Pathol. 168:413-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGrath, M. E. 1999. The lysosomal cysteine proteases. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 28:181-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKinley, M. P., A. Taraboulos, L. Kenaga, D. Serban, A. Stieber, S. J. DeArmond, S. B. Prusiner, and N. Gonatas. 1991. Ultrastructural localization of scrapie prion proteins in cytoplasmic vesicles of infected cultured cells. Lab. Investig. 65:622-630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mellon, P. L., J. J. Windle, P. C. Goldsmith, C. A. Padula, J. L. Roberts, and R. I. Weiner. 1990. Immortalization of hypothalamic GnRH neurons by genetically targeted tumorigenesis. Neuron 5:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montrasio, F., R. Frigg, M. Glatzel, M. A. Klein, F. Mackay, A. Aguzzi, and C. Weissmann. 2000. Impaired prion replication in spleens of mice lacking functional follicular dendritic cells. Science 288:1257-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murk, J. L., W. Stoorvogel, M. J. Kleijmeer, and H. J. Geuze. 2002. The plasticity of multivesicular bodies and the regulation of antigen presentation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:303-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parizek, P., C. Roeckl, J. Weber, E. Flechsig, A. Aguzzi, and A. J. Raeber. 2001. Similar turnover and shedding of the cellular prion protein in primary lymphoid and neuronal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276:44627-44632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peretz, D., R. A. Williamson, K. Kaneko, J. Vergara, E. Leclerc, G. Schmitt-Ulms, I. R. Mehlhorn, G. Legname, M. R. Wormald, P. M. Rudd, R. A. Dwek, D. R. Burton, and S. B. Prusiner. 2001. Antibodies inhibit prion propagation and clear cell cultures of prion infectivity. Nature 412:739-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prusiner, S. B. 1998. Prions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:13363-13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prusiner, S. B., M. R. Scott, S. J. DeArmond, and F. E. Cohen. 1998. Prion protein biology. Cell 93:337-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saino, T., T. Someno, H. Miyazaki, and S. Ishii. 1982. Semisynthesis of 14C-labelled leupeptin. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 30:2319-2325. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sethi, S., G. Lipford, H. Wagner, and H. Kretzschmar. 2002. Postexposure prophylaxis against prion disease with a stimulator of innate immunity. Lancet 360:229-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sigurdsson, E. M., D. R. Brown, M. Daniels, R. J. Kascsak, R. Kascsak, R. Carp, H. C. Meeker, B. Frangione, and T. Wisniewski. 2002. Immunization delays the onset of prion disease in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 161:13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Souan, L., Y. Tal, Y. Felling, I. R. Cohen, A. Taraboulos, and F. Mor. 2001. Modulation of proteinase-K resistant prion protein by prion peptide immunization. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:2338-2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sugaya, M., K. Nakamura, T. Watanabe, A. Asahina, N. Yasaka, Y. Koyama, M. Kusubata, Y. Ushiki, K. Kimura, A. Morooka, S. Irie, T. Yokoyama, K. Inoue, S. Itohara, and K. Tamaki. 2002. Expression of cellular prion-related protein by murine Langerhans cells and keratinocytes. J. Dermatol. Sci. 28:126-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Supattapone, S., P. Bosque, T. Muramoto, H. Wille, C. Aagaard, D. Peretz, H. O. Nguyen, C. Heinrich, M. Torchia, J. Safar, F. E. Cohen, S. J. DeArmond, S. B. Prusiner, and M. Scott. 1999. Prion protein of 106 residues creates an artifical transmission barrier for prion replication in transgenic mice. Cell 96:869-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Supattapone, S., E. Bouzamondo, H. L. Ball, H. Wille, H. O. Nguyen, F. E. Cohen, S. J. DeArmond, S. B. Prusiner, and M. Scott. 2001. A protease-resistant 61-residue prion peptide causes neurodegeneration in transgenic mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:2608-2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tal, Y., L. Souan, I. R. Cohen, Z. Meiner, A. Taraboulos, and F. Mor. 2003. Complete Freund's adjuvant immunization prolongs survival in experimental prion disease in mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 71:286-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taraboulos, A., A. J. Raeber, D. R. Borchelt, D. Serban, and S. B. Prusiner. 1992. Synthesis and trafficking of prion proteins in cultured cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 3:851-863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taraboulos, A., M. Scott, A. Semenov, D. Avrahami, L. Laszlo, S. B. Prusiner, and D. Avraham. 1995. Cholesterol depletion and modification of COOH-terminal targeting sequence of the prion protein inhibit formation of the scrapie isoform. J. Cell Biol. 129:121-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taraboulos, A., D. Serban, and S. B. Prusiner. 1990. Scrapie prion proteins accumulate in the cytoplasm of persistently infected cultured cells. J. Cell Biol. 110:2117-2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thery, C., L. Zitvogel, and S. Amigorena. 2002. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:569-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vey, M., S. Pilkuhn, H. Wille, R. Nixon, S. J. DeArmond, E. J. Smart, R. G. Anderson, A. Taraboulos, and S. B. Prusiner. 1996. Subcellular colocalization of the cellular and scrapie prion proteins in caveolae-like membranous domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:14945-14949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vincent, B., E. Paitel, Y. Frobert, S. Lehmann, J. Grassi, and F. Checler. 2000. Phorbol ester-regulated cleavage of normal prion protein in HEK293 human cells and murine neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 275:35612-35616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williamson, R. A., D. Peretz, C. Pinilla, H. Ball, R. B. Bastidas, R. Rozenshteyn, R. A. Houghten, S. B. Prusiner, and D. R. Burton. 1998. Mapping the prion protein using recombinant antibodies. J. Virol. 72:9413-9418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yedidia, Y., L. Horonchik, S. Tzaban, A. Yanai, and A. Taraboulos. 2001. Proteasomes and ubiquitin are involved in the turnover of the wild-type prion protein. EMBO J. 20:5383-5391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang, Y., E. Spiess, M. H. Groschup, and A. Burkle. 2003. Up-regulation of cathepsin B and cathepsin L activities in scrapie-infected mouse Neuro2a cells. J. Gen. Virol. 84:2279-2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]