Abstract

We compared the distribution of mutations in rpoB that lead to rifampin resistance in strains with differing levels of polymerase IV (Pol IV), including strains with deletions of the Pol IV-encoding dinB gene, strains with a chromosomal copy of dinB, strains with the F′128 plasmid, and strains with plasmid amplification of either the dinB operon (dinB-yafNOP) or the dinB gene alone. This analysis identifies several hot spots specific to Pol IV which are virtually absent from the normal spontaneous spectrum, indicating that Pol IV does not contribute significantly to mutations occurring during exponential growth in liquid culture.

Damage-inducible polymerases (20, 22; for reviews, see references 9 and 16), such as the SOS-induced polymerase IV (Pol IV) and Pol V in Escherichia coli, not only bypass certain noncoding lesions but also increase replication errors across from normal bases (19, 20, 23). Their discovery has led to the suggestion that a significant fraction of spontaneous mutations in growing cells under normal conditions might be due to errors caused by basal levels of error-prone polymerases (18). The dinB-encoded Pol IV is the leading candidate, since the overexpression of dinB on high-copy plasmids leads to increases in base substitutions and frameshifts, particularly −1 frameshifts (11, 12, 23). Moreover, several studies have shown an approximately twofold decrease in spontaneous mutations in strains with an inactivating allele of dinB that also reduces the expression of three genes downstream of dinB-yafNOP (14, 18), although this effect is not present if only dinB is inactivated (14). The expression of dinB and yafNOP is increased after SOS induction by DNA-damaging agents (4), and these four genes have been shown to be part of an operon (14).

We decided to examine the spectra of base substitution mutations in strains with differing levels of dinB expression, since a comparison of detailed genetic fingerprints of these strains might reveal patterns specific to processes involving and not involving Pol IV. We recently characterized a system using mutations in the rpoB gene that yield the rifampin resistance (Rifr) phenotype at 37°C in order to analyze the base substitution profiles of mutagens and mutators (10). We have now characterized 77 mutations in rpoB. Each of the six base substitutions is monitored with a set of 9 to 17 sites. In the study reported here, we looked at cells that carry a single copy of the dinB operon on the chromosome and compared the mutational spectrum of these cells with those of strains with deletions of the dinB gene, strains that carry a second copy of the dinB operon on an F′ plasmid, and strains that carry a multicopy plasmid with an insert containing the dinB operon in one case and just the dinB gene in another case. We showed that some mutational hot spots are specific for the overexpression of the dinB operon and that others are found in the spectrum of wild-type strains but not after the amplification of the dinB operon. A comparison of the different spectra leads us to conclude that spontaneous mutations occurring during exponential growth in the absence of SOS induction or a dinB-overexpressing plasmid do not contain a significant contribution from dinB-Pol IV-induced mutations.

Table 1 shows the strains used in this work. We examined the frequencies of Rifr mutants that result from mutations in rpoB in strains P90C, CC107, EW90, EW99, EW100, and EW101. EW90 carries a deletion of dinB (1) that is nonpolar for the expression of the other genes in the dinB operon, and CC107 (5) is a derivative of P90C (15) that has an F′128 with a mutated lac operon, proAB, and the dinB operon (11). The expression of dinB from the F′ plasmid has been reported to be three times higher than that from the chromosome (11), so CC107 would have four times the dinB level of P90C. EW100 is a CC107 derivative carrying a multicopy plasmid that overexpresses the dinB operon, and EW101 is the same as EW100 except that the plasmid insert contains only the dinB gene. EW99 carries the plasmid without any insert. We did not detect any difference in mutation frequencies among CC107, P90C, or EW90, as shown in Table 2. EW100 and EW101 have six- to sevenfold higher Rifr frequencies than the EW99 control (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

E. coli K-12 strains used in this study

| Strain | Derivation | Plasmid | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P90C | ara Δ(gpt-lac)5 thi | 15 | ||

| CC107 | F′128 lacIZ proA+B+ | ara Δ(gpt-lac)5 thi | 5 | |

| EW90a | ara ΔdinB61::ble Δ(gpt-lac)5 thi | This work | ||

| EW99b | CC107 | pCR2.1-TOPOcam | ara Δ(gpt-lac)5 thi | This work |

| EW100c | EW99 | dinB-yafNOP | ara Δ(gpt-lac)5 thi | This work |

| EW101d | EW99 | dinB | ara Δ(gpt-lac)5 thi | This work |

| EM90 | ara Δ(gpt-lac)5 mutS::mini-Tn10 thi | This work | ||

| EC90 | ara ΔdinB61::ble Δ(gpt-lac)5 mutS::mini-Tn10 thi | This work |

Contains ΔdinB61::ble, a nonpolar deletion from strain AR30 (1) transferred to a Rifr derivative of P90C by Pat Foster. We converted this strain to a Rifs derivative (EW90) by two P1 transductions, crossing in a Tn10 in argE and then crossing it out selecting for Arg+ and screening for Rifs. The relevant region of the rpoB gene was sequenced for verification.

Contains a plasmid derived from pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) by inserting the cat gene.

Contains a 5.2-kb fragment derived by partial Sau3AI digestion of E. coli DNA and cloned into the BamHI site. This fragment contains mbhA, dinB, yafNOP, and b0235.

Contains a 1.5-kb fragment insert encoding only the dinB gene amplified by PCR with forward primer 5′-GGGGATAAAGTGGTACCGCCGCTGGT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CCGCAACCGGTGGATCCATAAAGTATTTAGC-3′ and subsequently cloned into the KpnI-BamHI site.

TABLE 2.

rpoB frequencies and rates of mutationsa

| Strain | ƒ (10−8)b | μ (10−8)b |

|---|---|---|

| CC107 | 7.6 (5.2-8.8) | 1.5 (1.1-1.7) |

| P90C | 11 (9.1-14) | 1.8 (1.5-2.2) |

| EW90 | 7.1 (4.2-9.8) | 1.3 (0.82-1.7) |

| EW99 | 3.5 (2.0-6.8) | 0.65 (0.41-1.1) |

| EW100 | 22 (14-30) | 3.6 (2.5-4.7) |

| EW101 | 26 (14-44) | 4.3 (2.6-6.8) |

The rpoB mutation frequency (ƒ) per cell was calculated by dividing the median number of mutants by the average number of cells in a series of cultures, and the mutation rate (μ) per replication was calculated from these values by the method of Drake (7).

Mean value with 95% confidence limit (6) in parentheses.

We analyzed mutations by direct DNA sequencing (for the methods used, see reference 10) and in a number of cases supplemented the sequence analysis with oligonucleotide hybridization (3, 17). In the these cases, colonies were spotted onto LB Omnitrays (Nunc, Rochester, N.Y.), grown overnight at 37°C, and transferred to nylon membranes (Hybond N) from Amersham (Piscataway, N.J.). The membranes were placed in denaturing solution (1.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M NaOH) for 7 min and then in neutralizing solution (1.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M Tris-HCl [pH 7.2], 0.001 M EDTA) for 6 min. The membranes were baked at 80°C for 2 h and prehybridized (5× SSPE [1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA {pH 7.7}], 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 5× Denhardt's solution, 100 μg of herring sperm DNA/ml) during shaking at 47°C for 1 h. 32P-end-labeled probes (5 pmol of oligonucleotide strand, 10 U of T4 polynucleotide kinase, 5× T4 polynucleotide kinase buffer, 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP/μl) were denatured at 100°C for 5 min, and 1 μl was added to hybridization solutions for each oligonucleotide tested. Following hybridization overnight at 47°C, membranes were washed twice in 2× SSPE-0.1% SDS at room temperature for 10 min, once in 1× SSPE-0.1% SDS at 47°C for 15 min, and once in 0.1× SSPE-0.1% SDS at 47°C for 10 min. Autoradiography was carried out with a phosphorimaging screen.

The oligonucleotides were complementary to the mutant and wild-type sequences at the following base mutation sites in E. coli (corresponding base pair mutations from the wild type to the mutant are indicated in boldface type): 437 (T→G), 5′-GTGTTATCGTTTCCCAGCT-3′; 443 (A→T), 5′-ATCGTTTCCCAGCTGCA-3′; 1534 (T→C), 5′-GCCAGCTGTCTCAGTTTAT-3′; 1538 (A→T), 5′-AGCTGTCTCAGTTTATGGA-3′; 1546 (G→A), 5′-TCAGTTTATGGACCAGAA-3′; 1547 (A→G), 5′-GTTTATGGACCAGAACAAC-3′; 1576 (C→A), 5′-CTGAGATTACGCACAAACG-3′; 1576 (C→T), 5′-TGAGATTACGCACAAACG-3′; 1714 (A→C), 5′-TCGGTCTGATCAACTCTCT-3′; 1721 (C→T), 5′-TGATCAACTCTCTGTCCGT-3′.

Table 3 shows the sequence results for 1,057 mutations in rpoB from the strains described above, as well as from EM90 and EC90, mutS (mismatch repair-deficient) derivatives of P90C and EW90, respectively. We can make several comparisons on the basis of Table 3. The sites that are most prominent in the two wild-type spectra, those of CC107 and P90C (with and without F′128, respectively), are well represented in the spectrum of EW90 (which has a deletion of dinB). (Note that the CC107 sample is twice the size of both the P90C and the EW90 samples.) For example, the five most frequent changes in the wild-type (CC107 and P90C) samples are AT→GC at sites 1547 and 1534, GC→AT at site 1576, AT→TA at site 443, and AT→CG at site 1714. The first four of these changes are also prominent in the spectrum of EW90 (which has a deletion of dinB), and the fifth one (AT→CG at site 1714) is still represented in EW90. Therefore, the polymerases operating in the absence of Pol IV are capable of producing the hot spots seen in the wild-type spectra. Only the GC→AT transition at site 1576 is lacking in prominence in the spectrum of P90C (the wild type without the F′128), but this mutation is also very prominent in EW90, the dinB deletion derivative of P90C. Moreover, the distributions of mutations in a mutS background, lacking mismatch repair, are very similar in strains with and without the dinB deletion (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Distribution of mutations in rpoB

| Site (bp) | Amino acid change | Base pair change | No. of occurrences for:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EW100 | CC107 | P90C | EW90 | EM90 | EC90 | |||

| 443 | Q148R | AT→GC | 2 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1522 | S508P | AT→GC | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1532 | L511P | AT→GC | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 1534 | S512P | AT→GC | 13 | 17 | 13 | 11 | 22 | 11 |

| 1538 | Q513R | AT→GC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 1547 | D516G | AT→GC | 46 | 40 | 16 | 27 | 36 | 67 |

| 1552 | N518D | AT→GC | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 1577 | H526R | AT→GC | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| 1598 | L533P | AT→GC | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| 1703a | N568S | AT→GC | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1715 | I572T | AT→GC | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 1520 | G507D | GC→AT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1535 | S512F | GC→AT | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1546 | D516N | GC→AT | 23 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| 1565 | S522F | GC→AT | 4 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1576 | H526Y | GC→AT | 12 | 25 | 2 | 11 | 1 | 0 |

| 1585 | R529C | GC→AT | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1586 | R529H | GC→AT | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1592 | S531F | GC→AT | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1595 | A532V | GC→AT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1600 | G534S | GC→AT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1601 | G534D | GC→AT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 1609 | G537S | GC→AT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1610a | G537D | GC→AT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1691 | P564L | GC→AT | 4 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 1708 | G570S | GC→AT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1721 | S574F | GC→AT | 3 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2060b | R687H | GC→AT | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 443 | Q148L | AT→TA | 4 | 38 | 27 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| 1532 | L511Q | AT→TA | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1538 | Q513L | AT→TA | 2 | 11 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1547 | D516V | AT→TA | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 1568 | E523V | AT→TA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1577 | H526L | AT→TA | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 1598 | L533H | AT→TA | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1714 | I572F | AT→TA | 4 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 1 |

| 1715 | I572N | AT→TA | 1 | 2 | 9 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| 437 | V146G | AT→CG | 17 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 443 | Q148P | AT→CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 1525 | S509R | AT→CG | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 1532 | L511R | AT→CG | 0 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 1534 | S512A | AT→CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1538 | Q513P | AT→CG | 3 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 1547 | D516A | AT→CG | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1577 | H526P | AT→CG | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1598 | L533R | AT→CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1687 | T563P | AT→CG | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 1714 | I572L | AT→CG | 28 | 31 | 8 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| 1715 | I572S | AT→CG | 2 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 436 | V146F | GC→TA | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 442 | Q148K | GC→TA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 444 | Q148H | GC→TA | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1527 | S509R | GC→TA | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1535 | S512Y | GC→TA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1537 | Q513K | GC→TA | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1546 | D516Y | GC→TA | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1565 | S522Y | GC→TA | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1576 | H526N | GC→TA | 62 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1578 | H526Q | GC→TA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1586 | R529L | GC→TA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1592 | S531Y | GC→TA | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1595 | A532E | GC→TA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1600 | G534C | GC→TA | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1601 | G534V | GC→TA | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1708 | G570C | GC→TA | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1721 | S574Y | GC→TA | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1585b | R529S | GC→TA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 444 | Q148H | GC→CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1527 | S509R | GC→CG | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1574 | T525R | GC→CG | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1576 | H526D | GC→CG | 20 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1578 | H526Q | GC→CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1585 | R529G | GC→CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1600 | G534R | GC→CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1601 | G534A | GC→CG | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1691 | P564R | GC→CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1709 | G570A | GC→CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1716 | I572M | GC→CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2059 | R687G | GC→CG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not found | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Totalc | 289 | 298 | 146 | 156 | 88 | 80 | ||

First described in this study.

Shows temperature effects between 30 and 42°C and may not yield Rifr colonies at 37°C.

The results for 77 sites were considered for the total, but the number increases to 79 with the inclusion of sites 2060 and 1585.

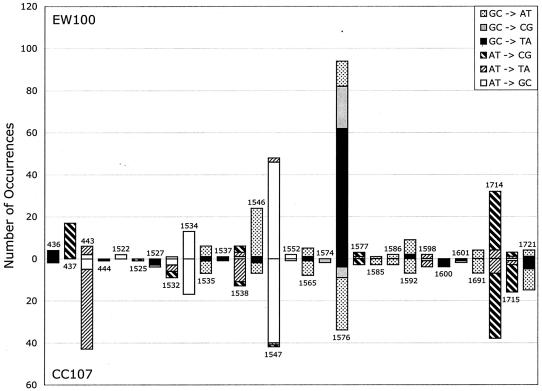

We can also compare the mutational profiles of strains CC107, P90C, and EW90 with that of EW100, the strain carrying pdinB-yafNOP and yielding an elevated level of rpoB mutations (Table 2). (It should be noted that the distribution of mutations in CC107 containing the plasmid without an insert [EW99; data not shown] is the same as that for CC107 alone.) A comparison of CC107 and EW100 (with the same sample size of approximately 300 mutations each) shows that although there are marked similarities with regard to some of the hot spots, there are also several clear differences. Most notably, the GC→TA transversion at site 1576 is the most prominent change for EW100 with 62 occurrences, compared with 4 occurrences for CC107. The other transversion at this site, GC→CG, is also more prominent in EW100 than in CC107. In addition, the AT→CG transversion at position 437 is represented by 17 occurrences in the EW100 sample, but it is absent from the spectra of CC107 and P90C (with a sample size of 146). Thus, there are three hot spots present in the Pol IV-overproducing strain (EW100) that are essentially absent from the wild-type (CC107) strain. On the other hand, the AT→TA transversion at 443 appears to occur frequently in all of the strains that lack the Pol IV-overexpressing plasmid but not in the strain (EW100) with the overexpressing plasmid (38 occurrences in CC107 versus 4 occurrences in EW100 for the same sample size).

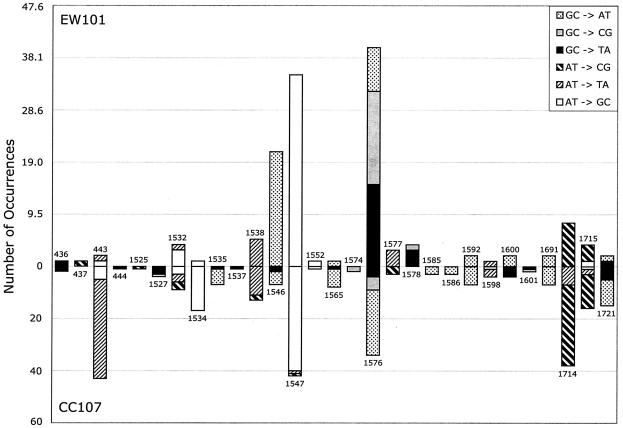

Figure 1 displays the data from Table 3 by position so that different base substitutions at the same site can be visualized together while the mutation type can still be distinguished. It can be seen that position 1576 is the most prominent hot spot in the EW100 (pdinB-yafNOP) spectrum, with the total number of mutations there accounting for 30% of all the base substitutions in the EW100 profile. In contrast to the predominance of GC→TA and GC→CG transversions at site 1576 in the pdinB-yafNOP (EW100) spectrum, mutations at this site in the wild-type (CC107) spectrum are mostly GC→AT transitions. Although there are many similarities between these two spectra, they clearly differ at positions 437 and 443, in addition to the pronounced difference in transversions at 1576. We also found no difference in the distributions of mutations in EW100 (carrying pdinB-yafNOP) and EW101 (carrying pdinB) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Distribution of mutations in rpoB that lead to Rifr in the wild-type strain (CC107) and in a derivative (EW100) carrying dinB-yafNOP on a multicopy plasmid. Similar sample sizes (294 for CC107 and 289 for EW100) were used. Different base substitutions at the same site are indicated by different patterns. The positions of the sites are indicated with numbers above and below (see Table 3) and are not to scale.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of mutations in rpoB that lead to Rifr in the wild-type strain (CC107) and a derivative (EW101) carrying the dinB gene on a multicopy plasmid. Because different sample sizes are used, the peak heights here represent percentages of the sample size (140 for EW101 and 294 for CC107, with the heights of the EW101 peaks being effectively normalized [by multiplying by 2.1] to fit the CC107 sample size). The vertical axis indicates actual numbers, but the scales of the peak heights differ. This approach allows a visual comparison with Fig. 1. Note that the transversions at site 1576 are prominent in EW101, as they are in EW100 (Fig. 1). In EW101, at site 1576, GC→CG transversions occur in 17 of 140 instances, compared with 5 of 294 instances for CC107, and GC→TA transversions occur in 15 of 140 instances, compared with 4 of 294 instances for CC107.

Taken together, the data in Table 3 and Fig. 1 and 2 argue that spontaneous base substitutions in wild-type strains such as P90C and CC107 do not contain significant contributions from the dinB-encoded Pol IV or products of the other dinB operon genes (yafNOP). The underrepresentation of the prominent hot spots in rpoB that are specific to the pdinB-yafNOP-containing strain (EW100) in the spectrum of mutations from CC107 allows us to place an upper limit on the contribution from Pol IV and putative products of the yafNOP genes at no more than 10%. The data also indicate that there is no difference in the base substitution mutational spectra of strains with and without the F′128 plasmid, even though there is a fourfold difference in Pol IV levels. It should be noted that all of these determinations are for mutations occurring in growing cells. For adaptive mutations occurring in the stationary phase (2, 8), a requirement for Pol IV has been reported (13, 21).

Acknowledgments

We thank Roger Woodgate and Pat Foster for bacterial strains.

J.H.M. was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (grant no. ES0110875).

REFERENCES

- 1.Borden, A., P. I. O'Grady, D. Vandewiele, A. R. Fernández de Henestrosa, C. W. Lawrence, and R. Woodgate. 2002. Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III can replicate efficiently past a T-T cis-syn cyclobutane dimer if DNA polymerase V and the 3′ to 5′ exonuclease proofreading function encoded by dnaQ are inactivated. J. Bacteriol. 184:2674-2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cairns, J., and P. L. Foster. 1991. Adaptive reversion of a frameshift mutation in Escherichia coli. Genetics 128:695-701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cebula, T., and W. Koch. 1990. Analysis of spontaneous and psoralen-induced Salmonella typhimurium hisG46 revertants by oligodeoxyribonucleotide colony hybridization: use of psoralens to cross-link probes to target sequences. Mutat. Res. 229:79-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courcelle, J., A. Khodursky, B. Peter, P. O. Brown, and P. C. Hanawalt. 2001. Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics 158:41-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cupples, C. G., M. Cabrera, C. Cruz, and J. H. Miller. 1990. A set of lacZ mutations in Escherichia coli that allow rapid detection of specific frameshift mutations. Genetics 125:275-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon, W. J., and F. J. Massey, Jr. 1969. Introduction to statistical analysis. McGraw-Hill, New York, N.Y.

- 7.Drake, J. W. 1991. A constant rate of spontaneous mutation in DNA-based microbes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:7160-7164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster, P. L. 1999. Mechanism of stationary phase mutation: a decade of adaptive mutation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 33:57-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedberg, E. C., R. Wagner, and M. Radman. 2002. Specialized DNA polymerases, cellular survival, and the genesis of mutation. Science 296:1627-1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garibyan, L., T. Huang, M. Kim, E. Wolff, A. Nguyen, T. Nguyen, A. Diep, K. Hu, A. Iverson, H. Yang, and J. H. Miller. 2003. Use of the rpoB gene to determine the specificity of base substitution mutations on the Escherichia coli chromosome. DNA Repair 2:593-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, S.-R., K. Matsui, M. Yamada, P. Gruz, and T. Nohmi. 2001. Roles of chromosomal and episomal dinB genes encoding DNA pol IV in targeted and untargeted mutagenesis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:207-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim, S.-R., G. Maenhaut-Michel, M. Yamada, Y. Yamamoto, K. Matsui, T. Sofuni, T. Nohmi, and H. Ohmori. 1997. Multiple pathways for SOS-induced mutagenesis in Escherichia coli: an SOS gene product (DinB/P) enhances frameshift mutations in the absence of any exogenous agents that damage DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:13792-13797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKenzie, G. J., P. L. Lee, M.-J. Lombardo, P. J. Hastings, and S. M. Rosenberg. 2001. SOS mutator DNA polymerase IV functions in adaptive mutation and not adaptive amplification. Mol. Cell 7:571-579. (Erratum, 7:1119.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKenzie, G. J., D. B. Magner, P. L. Lee, and S. M. Rosenberg. 2003. The dinB operon and spontaneous mutation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:3972-3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller, J. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 16.Ohmori, H., E. C. Friedberg, R. P. P. Fuchs, M. F. Goodman, F. Hanaoka, D. Hinkle, T. A. Kunkel, C. W. Lawrence, Z. Livneh, T. Nohmi, L. Prakash, S. Prakash, T. Todo, G. C. Walker, Z. Wang, and R. Woodgate. 2001. The Y-family of DNA polymerases. Mol. Cell 8:7-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rangarajan, S., G. Gudmundsson, Z. Qiu, P. Foster, and M. Goodman. 1997. Escherichia coli DNA polymerase II catalyzes chromosomal and episomal DNA synthesis in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:946-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strauss, B. S., R. Roberts, L. Francis, and P. Pouryazdanparast. 2000. Role of the dinB gene product in spontaneous mutation in Escherichia coli with an impaired replicative polymerase. J. Bacteriol. 182:6742-6750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang, M., P. Pham, X. Shen, J. S. Taylor, M. O'Donnell, R. Woodgate, and M. F. Goodman. 2000. Roles of E. coli DNA polymerase IV and V in lesion-targeted and untargeted SOS mutagenesis. Nature 404:1014-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang, M., X. Shen, E. G. Frank, M. O'Donnell, R. Woodgate, and M. F. Goodman. 1999. UmuD′(2)C is an error-prone DNA polymerase, Escherichia coli pol V. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8919-8924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tompkins, J. D., J. L. Nelson, J. C. Hazel, S. L. Leugers, J. D. Stumpf, and P. L. Foster. 2003. Error-prone polymerase, DNA polymerase IV, is responsible for transient hypermutation during adaptive mutation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:3469-3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagner, J., P. Gruz, S. R. Kim, M. Yamada, K. Matsui, R. P. P. Fuchs, and T. Nohmi. 1999. The dinB gene encodes a novel E. coli DNA polymerase, DNA pol IV, involved in mutagenesis. Mol. Cell 4:281-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner, J., and T. Nohmi. 2000. Escherichia coli DNA polymerase IV mutator activity: genetic requirements and mutational specificity. J. Bacteriol. 182:4587-4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]