Dear Editor,

We previously developed a novel paradigm of cell activation and signaling-directed (CASD) lineage conversion for direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into cardiac, neural and endothelial precursor cells. This method is based on the transient overexpression of iPSC factors (cell activation, CA) in conjunction with lineage-specific soluble signals (signaling directed, SD). Such a strategy was used to generate human induced neural stem cells (hiNSCs) with 4 to 6 pluripotency factors, including OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and microRNAs, from cells in human urine1 and fibroblasts2. Using a different strategy, SOX2 was found to induce the generation of hiNSCs, although only from fetal fibroblasts with low efficiency and by a tedious process3.

Our long-term goal is to develop simpler and safer reprogramming methods for cell-based applications and, ultimately, to apply this reprogramming strategy pharmacologically in vivo for tissue regeneration. Thus, we are developing a strategy to identify and combine small molecules to replace genetic factors. To this end, we report here a proof-of-concept study that a cocktail of only small molecules could replace 3 of the 4 reprogramming factors under the CASD lineage-reprogramming paradigm to enable OCT4-only iNSC reprogramming of human neonatal and adult fibroblasts.

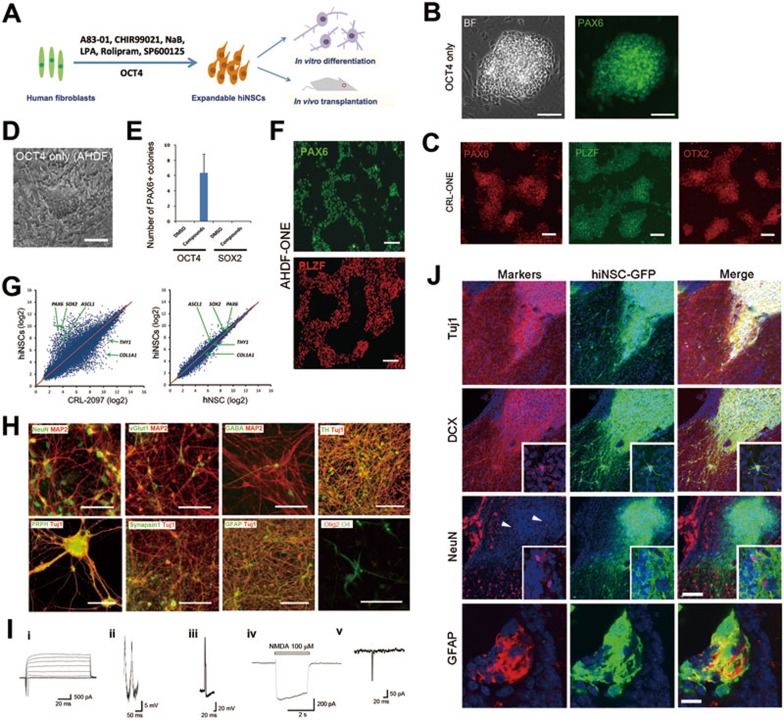

First, we introduced OCT4 and SOX2 (OS) or OCT4 alone into human neonatal fibroblasts (CRL-2097) that lacked neural or pluripotency marker expression (Supplementary information, Figure S1). After 4-5 weeks under reprogramming conditions containing A83-01 (a TGFβ inhibitor) and CHIR99021 (a GSK3β inhibitor), which were similar to human primitive NSC (hNSC) cultures4 (Figure 1A and Supplementary information, Data S1), CRL-2097 transduced with either OS or OCT4 generated colonies (average 10-16 and 1-2 colonies from 6 × 104 CRL-2097 transduced with OS and OCT4, respectively) that were morphologically distinct from background cells and homogeneously expressed hNSC marker PAX6 (Figure 1B and 1C). However, adult dermal fibroblasts (AHDF) transduced with OCT4 alone failed to generate hNSC colonies under the same condition. Through chemical screenings under basal conditions containing A83-01, CHIR99021 and sodium butyrate (NaB, an HDAC inhibitor)5, we found that a combination of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA, a phospolipid derivative), rolipram (a PDE4 inhibitor), and SP600125 (a JNK inhibitor) facilitated the reprogramming of AHDF transduced with OCT4 alone. Thereafter, we formulated a chemical cocktail, containing 0.5 μM A83-01, 3 μM CHIR99021, 0.2 mM NaB, 2 μM LPA, 2 μM rolipram, and 2 μM SP600125, which combined with the ectopic expression of OCT4 could convert AHDF into hiNSC colonies that homogeneously expressed PAX6 (average 6 colonies from 2 × 105AHDF) (Figure 1D and 1E). Interestingly, ectopic expression of SOX2 alone under these conditions failed to generate hiNSC colonies (Figure 1E). After isolation and expansion, the reprogrammed hiNSC colonies continued to homogeneously express PAX6, PLZF and OTX2, supporting their hNSC identity4 (Figure 1C and 1F). We designated these reprogrammed cells as ONE (OCT4 only-induced neuro-epithelium). These hiNSCs expressed the proliferative marker Ki67 and showed growth rate comparable to human embryonic stem cell-derived NSCs (control hNSCs) (Supplementary information, Figure S2). We expanded and maintained these hiNSCs stably for more than 5 months. Additionally, we established hiNSC lines by using an episomal system expressing OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and p53 shRNA6 in combination with the chemical cocktail from both neonatal (average 20-25 colonies from 4 × 105 CRL-2097) and adult fibroblasts (average 8-10 colonies from 4 × 105 AHDF) around 4-5 weeks after electroporation (Supplementary information, Figure S3), confirming that our chemical cocktail efficiently facilitates hiNSC reprogramming.

Figure 1.

hiNSC reprogramming with OCT4 and small molecules. (A) Reprogramming conditions for the generation of hiNSCs. Human fibroblasts were transduced with OCT4 alone and cultured for 28-35 days with small molecules. The details are described in the Supplementary information, Data S1. (B) Representative images of hiNSC colonies reprogrammed from CRL-2097 transduced with OCT4 alone, and immunostained with PAX6. BF, brightfield. Scale bars, 100 μm. (C) Immunostaining of isolated and expanded hiNSC colonies (at passage > 5) reprogrammed from CRL-2097 with OCT4 alone (CRL-ONE). PAX6 (left), PLZF (middle) and OTX2 (right) are expressed homogeneously in all cells. Scale bars, 100 μm. (D) Reprogramming of AHDF. Brightfield image of a hiNSC-like colony. Scale bar, 100 μm. (E) Histogram showing the number of PAX6-positive colonies generated by direct reprogramming of AHDF transduced with OCT4 or SOX2 alone and cultured for 35 days with small molecules (n = 3). (F) Immunostaining of isolated and expanded hiNSC colonies (at passage > 5) reprogrammed from AHDF transduced with OCT4 alone (AHDF-ONE) and cultured for 35 days with the chemical cocktail. PAX6 and PLZF are expressed homogeneously in all cells. Scale bars, 100 μm. (G) Scatter plots comparing the global gene-expression patterns between hiNSCs and human fibroblasts (CRL-2097) or control hNSCs. The positions of the neuro-ectodermal genes PAX6, ASCL1 and SOX2, as well as fibroblast genes COL1A1 and THY1, are indicated by arrows. (H) Representative images of immunostained neuronal and glial cells differentiated from hiNSCs. These differentiated hiNSCs exhibited immunoreactivity to markers of mature neurons, neuronal subtypes, peripheral neurons and glias. Markers are indicated in each image. Scale bars, 100 μm. (I) Electrophysiological properties of hiNSC-derived neurons. (i) Representative trace of fast sodium current evoked by a series of depolarizing pulses. (ii, iii) Representative traces of spontaneous (ii) and evoked (iii) action potentials, as detected by whole-cell recording in current-clamp mode. Action potentials were detected after 5-6 weeks in culture. (iv) Whole-cell NMDA current. (v) sEPSCs recorded at a holding potential of −60 mV, indicating synapse formation. (J) Representative images of hiNSCs transplanted into the lateral ventricle of neonatal (P2 - P3) mice. After 4 weeks, a majority of hiNSCs differentiated into neuronal lineage cells expressing Tuj1 and DCX with extensive arborization, and insets show multiple processes with DCX expression. Some neuronal cells matured into NeuN-expressing neurons within cell clusters (arrowheads), and insets are large magnification views showing NeuN and GFP double-labeled cells. All markers were labeled with red, and nuclei were counter-stained with Hoechst33342 in blue. In some clusters of transplanted hiNSCs, differentiated glial lineage cells expressing GFAP were also found. Scale bars, 50 μm for the upper 3 lanes, 10 μm for the last lane.

Flow cytometry analysis highlighted the close similarity of hiNSCs to control hNSCs (Supplementary information, Figure S4A). Quantitative RT-PCR revealed that hiNSCs expressed PAX6, NESTIN and SOX1 at levels comparable to control hNSCs4 (Supplementary information, Figure S4B). Exogenous OCT4 was silenced and endogenous OCT4 expression was not observed in most established hiNSC lines (Supplementary information, Figure S5A and S5B). Notably, vector integration was not apparent in these episomal vector-driven hiNSCs (Supplementary information, Figure S6). The global gene-expression profile of hiNSCs closely resembled that of control hNSCs (Pearson correlation value: 0.96) and distinctly diverged from human fibroblasts (Pearson correlation value: 0.76) (Figure 1G). Collectively, these results suggest that our hiNSCs are comparable to control hNSCs.

When we examined gene expression changes during hiNSC reprogramming, we found that PAX6 expression became upregulated from day 7 (Supplementary information, Figure S7A). Most importantly, endogenous OCT4 (Supplementary information, Figure S7B) and the pluripotency marker TRA-1-60 (Supplementary information, Figure S7C) were undetectable during the entire process. At epigenetic level, the PAX6 and SOX1 promoters had repressive H3K27me3 marks in the starting fibroblasts (Supplementary information, Figure S8). However, by day 24, the H3K27me3 marks were considerably reduced at these loci, which then showed active H3K4me3 marks similar to control hNSCs. In contrast, the OCT4 promoter was persistently marked by H3K27me3 throughout the conversion process (Supplementary information, Figure S8), suggesting that the epigenetic status of directly reprogrammed hiNSCs are comparable to that of control hNSCs. Therefore, these results indicate a rapid direct conversion to hiNSCs in our reprogramming paradigm.

After 4 weeks of spontaneous or directed neural differentiation (Figure 1H and Supplementary information, Figure S9), these hiNSCs developed into cells expressing the early neuronal marker doublecortin (DCX) (Supplementary information, Figure S9), and subsequently the mature neuronal markers neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN) and microtubule-associated protein-2 (MAP2) (Figure 1H). These hiNSCs could also develop into glutamatergic, GABAergic and dopaminergic neurons (Figure 1H), as well as peripheral neurons. We observed the synaptic protein Synapsin1 expression in these differentiated neurons (Figure 1H and Supplementary information, Figure S9). Moreover, hiNSCs could be differentiated into astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (Figure 1H). These results indicate that these hiNSCs are multipotent.

To evaluate the functional properties of the hiNSC-derived neurons, we performed patch-clamp electrophysiological recordings. Under voltage clamp, the majority of 6-week-differentiated cells (n = 8/10) displayed fast sodium currents (Figure 1Ii), and under current clamp, we recorded spontaneous and evoked action potentials (Figure 1Iii and Iiii). Whole-cell recordings revealed a subset of cells (3/10) displaying N-methyl-𝒟-aspartate (NMDA)-type glutamate receptor currents after NMDA application (Figure Iiv), and a majority (17/29) exhibited an increase in intracellular calcium in response to NMDA, which was sensitive to the specific NMDA receptor antagonist 2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (Supplementary information, Figure S10). We also observed spontaneous excitatory post-synaptic currents in these cultures (Figure 1Iv), indicating the formation of functional synapses. These data suggest that hiNSCs can be differentiated into functional neurons.

Finally, we transplanted EGFP-labeled hiNSCs (∼1 × 105) into the lateral ventricle of neonatal mice. Two weeks after transplantation, we found that most EGFP-expressing hiNSCs migrated and integrated into several areas of the mouse brain, such as the lateral periventricular region, subventricular zone and subcallosal zone (Supplementary information, Figure S11A). A few transplanted cells also migrated into the nearby cerebral cortex and olfactory bulb (Supplementary information, Figure S11B). After 4 weeks, the transplanted hiNSCs formed cell clusters expressing neuronal lineage markers, such as Tuj1, DCX and NeuN (Figure 1J), and a subset of cell clusters contained GFAP-expressing astrocytes (Figure 1J). Importantly, these cell clusters were not labeled by a 2-h pulse of bromodeoxyuridine, and we could not find any sign of tumor formation (data not shown). These results show that the transplanted hiNSCs engraft well in neonatal mouse brains and retain their potential to give rise to neurons and glias in vivo.

In summary, we developed a novel chemical cocktail that enables the generation of expandable hiNSCs from human fibroblasts transduced with OCT4 alone. We found that SOX2 overexpression combined with the chemical cocktail treatment3 was not sufficient to reprogram adult fibroblasts, suggesting SOX2-mediated hiNSC reprogramming may follow a different reprogramming trajectory from our OCT4-mediated hiNSC reprogramming. These results further highlight the unique ability of the OCT4/CASD strategy and chemical cocktail in hiNSC reprogramming when considering the difficulty of reprogramming adult fibroblasts7. In the OCT4/CASD reprogramming paradigm8, environmental cues were found to be critical for committing cell fates1,9,10. Thus, the novel chemical cocktail we developed in this study can facilitate future investigations into the mechanistic basis of CASD reprogramming. Finally, we also anticipate that discovery of more small molecules and fine-tuning their combinations following the logic and strategy described here may increase the efficiency of hiNSC reprogramming and kinetics of this transition, and ultimately enable hiNSC reprogramming with only small molecules.

Accession Numbers

The accession number for the microarray data reported here is GSE38045.

Acknowledgments

JK, H-SK and YSC were supported by the MEST/Stem Cell Research Program [2010-0020272], Basic Science Research Program (2012R1A1A2043433), KRCF National Agenda Program, and KRIBB Research Initiative Program. SZ was supported by Gladstone CIRM Scholars Program. RA, MT, JDZ, SS-B, EM, SRM, and SAL were supported by P01 ES016738, P01 HD29587, and P30 NS076411. WS and HJK were supported by Basic Science Research Program (2012M3A9C6049933) through Korea NRF. TL, YZ and SD were supported by funding from California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, NICHD, NHLBI, NEI, NIMH/NIH, Prostate Cancer Foundation, and the Gladstone Institute. We thank Jianwei Che at Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation for analyzing the microarray data and Gary Howard at the Gladstone Institute for editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Characterization of starting foreskin fibroblasts.

The proliferative property of hiNSCs.

The NSC marker expression in the hiNSCs derived with the episomal method.

(A) Directly reprogrammed cells express markers similar to hNSCs.

(A) Low expression of residual exogenous OCT4 in directly reprogrammed hiNSCs.

Copy numbers of episomal vectors in each hiNSCs derived through episomal method.

Quantitative expression of marker genes during direct reprogramming using OCT4 alone.

Histone modification during direct reprogramming.

Immunostaining of cells differentiated from other hiNSC lines, CRL-EPI-NE and AHDF-EPI-NE. Scale bars, 100 μm

Representative traces showing 100 μM NMDA-induced calcium responses detected with Fura-2 in 8-week-old neurons derived from hiNSCs.

(A) GFP-expressing cells migrated and integrated into various areas of the mouse brain, including the subventricular zone (SVZ), subcallosal zone (SCZ), and cerebral cortex, 2 weeks after transplantation.

Materials and methods

References

- Wang L, Huang W, Su H, et al. Nat Methods. 2013. pp. 84–89. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lu J, Liu H, Huang CT, et al. Cell Rep. 2013. pp. 1580–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ring KL, Tong LM, Balestra ME, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2012. pp. 100–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li WL, Sun W, Zhang Y, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011. pp. 8299–8304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhu SY, Wei WG, Ding S. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2011. pp. 73–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Okita K, Matsumura Y, Sato Y, et al. Nat Methods. 2011. pp. 409–412. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pang ZP, Yang N, Vierbuchen T, et al. Nature. 2011. pp. 220–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim J, Ambasudhan R, Ding S. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012. pp. 778–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li J, Huang NF, Zou J, et al. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013. pp. 1366–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kurian L, Sancho-Martinez I, Nivet E, et al. Nat Methods. 2013. pp. 77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Characterization of starting foreskin fibroblasts.

The proliferative property of hiNSCs.

The NSC marker expression in the hiNSCs derived with the episomal method.

(A) Directly reprogrammed cells express markers similar to hNSCs.

(A) Low expression of residual exogenous OCT4 in directly reprogrammed hiNSCs.

Copy numbers of episomal vectors in each hiNSCs derived through episomal method.

Quantitative expression of marker genes during direct reprogramming using OCT4 alone.

Histone modification during direct reprogramming.

Immunostaining of cells differentiated from other hiNSC lines, CRL-EPI-NE and AHDF-EPI-NE. Scale bars, 100 μm

Representative traces showing 100 μM NMDA-induced calcium responses detected with Fura-2 in 8-week-old neurons derived from hiNSCs.

(A) GFP-expressing cells migrated and integrated into various areas of the mouse brain, including the subventricular zone (SVZ), subcallosal zone (SCZ), and cerebral cortex, 2 weeks after transplantation.

Materials and methods