Abstract

We describe a series of new vectors for PCR-based epitope tagging and gene disruption in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, an exceptional model organism for the study of cellular processes. The vectors are designed for amplification of gene-targeting DNA cassettes and integration into specific genetic loci, allowing expression of proteins fused to 12 tandem copies of the Pk (V5) epitope or 5 tandem copies of the FLAG epitope with a glycine linker. These vectors are available with various antibiotic or nutritional markers and are useful for protein studies using biochemical and cell biological methods. We also describe new vectors for fluorescent protein-tagging and gene disruption using ura4MX6, LEU2MX6, and his3MX6 selection markers, allowing researchers in the S. pombe community to disrupt genes and manipulate genomic loci using primer sets already available for the widely used pFA6a-MX6 system. Our new vectors may also be useful for gene manipulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Method Summary

Our 12Pk-tagging vectors for genomic integration significantly improve the sensitivity of protein detection by Western blotting. We also describe genomic 5FLAG-tagging vectors with a glycine linker, which allows flexibility between the epitope and the protein, enhancing immunoprecipitation efficiency. This report also describes vectors for fluorescent-tagging and gene deletion useful in S. pombe.

Keywords: Schizosaccharomyces pombe; Pk epitope tagging; FLAG tagging; glycine linker, fluorescent tagging; gene disruption; pFA6a

The fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe is an excellent model organism for studying a variety of biological processes (1). The pFA6a-MX6 plasmid is a commonly used backbone plasmid for generating epitope tagging vectors (2,3). To facilitate protein detection, many vectors are designed to express proteins with tandem copies of epitopes from their endogenous genomic loci. For example, 13×Myc (13Myc), 5×FLAG (5FLAG), and 3×HA (3HA) epitope tagging vectors are available (2,4). However, a system of tandem Pk epitope tagging vectors for genomic integration has not been reported, although episomal 3×Pk (3Pk)-tagging vectors are available (5).

The Pk epitope, which is also called V5, is a short amino acid epitope with the sequence GKPIPNPLLGLDST from the P and V proteins of the paramyxovirus SV5 (6). Antibodies against the Pk epitope are readily available from commercial sources, and Pk has been widely used for protein purification and detection. In addition, Pk-tagged proteins have successfully been used for chromatin precipitation (ChIP) assay and the related ChIP-seq approach (7). Although some vectors for genomic tagging with the Pk epitope are available in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, they contain only one copy of the epitope (8). Therefore, in order to facilitate Pk-epitope detection, we constructed a series of vectors for genomic tagging with 12 tandem copies of the Pk epitope (12Pk).

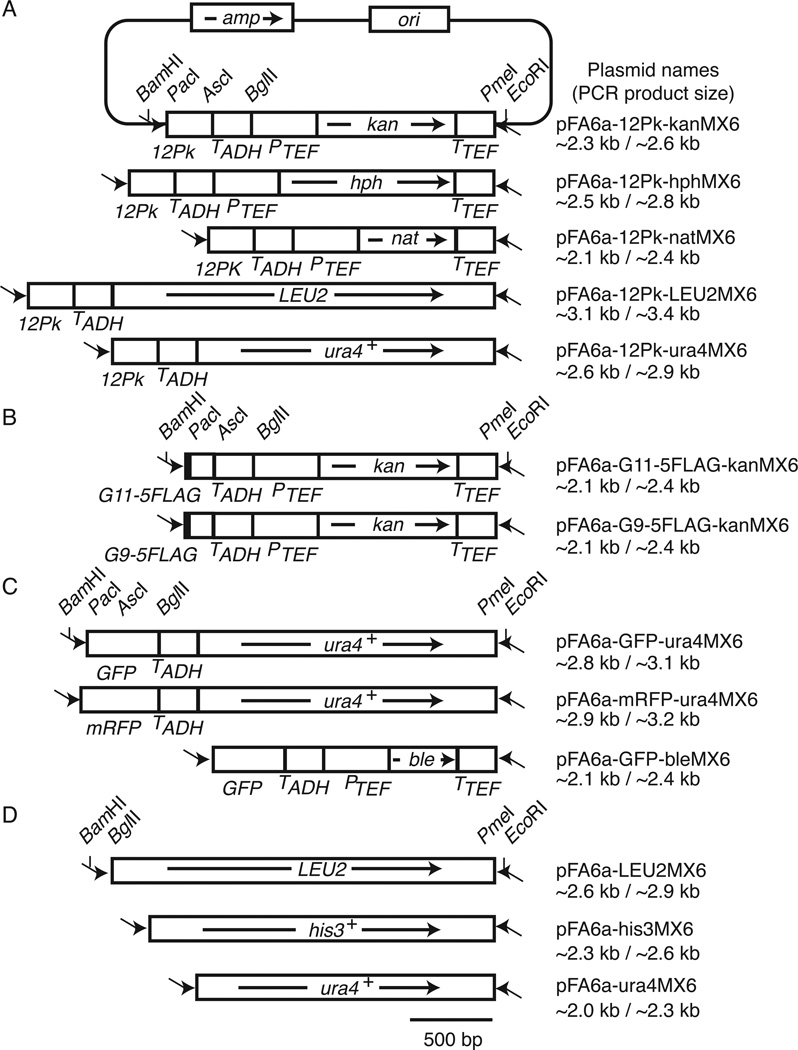

To construct Pk-tagging vectors using the pFA6a-MX6 system, the PacI-AscI 3HA fragment in the pFA6a-3HA-kanMX6 plasmid (2) was replaced with an XhoI adaptor sequence. Six copies of a DNA fragment containing two copies of the Pk sequence were introduced into the XhoI site, resulting in the pFA6a-12Pk-kanMX6 plasmid (Figure 1A). The kanamycin-resistant gene (kanMX6) (3) in this plasmid was then replaced with various selection marker genes, including hphMX6 (hygromycin-resistance gene) (9,10), natMX6 (nourseothricin-resistantce gene) (9,10), LEU2MX6 (S. cerevisiae LEU2 gene complementing S. pombe leu1 mutations), and ura4MX6 (S. pombe ura4+ gene) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Structures of pFA6a derivatives described in this study.

(A) pFA6a-12Pk-MX6 modules used to amplify gene cassettes for C-terminal 12Pk tagging. The pFA6a backbone is only shown for pFA6a-12Pk-kanMX6. Arrows inside the boxes indicate the transcriptional direction of selection marker genes. Primers for the one-step PCR method are shown as arrows outside the boxes (not to scale). (B) pFA6a-G11/9–5FLAG-kanMX6 modules for C-terminal G11/9–5FLAG tagging. (C) pFA6a derivative for C-terminal GFP and mRFP tagging. (D) Vectors for gene deletion using nutritional markers. All of these modules are based on the pFA6a system described by Bähler et al. (2). Plasmid names and PCR product sizes for both one-step and two-step PCR methods are shown. amp, ampicillin resistant gene; ori, replication origin; TADH, ADH1 gene terminator; PTEF, TEF gene promoter.

These vectors have structures similar to those of pFA6a-MX6-related epitope tagging vectors previously developed by Bähler et al. (2). Therefore, the same PCR primers described in their article can be used to perform the one-step PCR to generate gene-targeting DNA cassettes for 12Pk epitope tagging at the C terminus of a protein. The two-step PCR primers described by Krawchuk and Wahls (11) are also compatible with our constructs. Because our vectors are designed to introduce epitope sequences to the 3´ end of an open reading frame at its own genomic locus, tagged proteins are expressed from their endogenous promoter, allowing us to investigate protein function under physiological conditions.

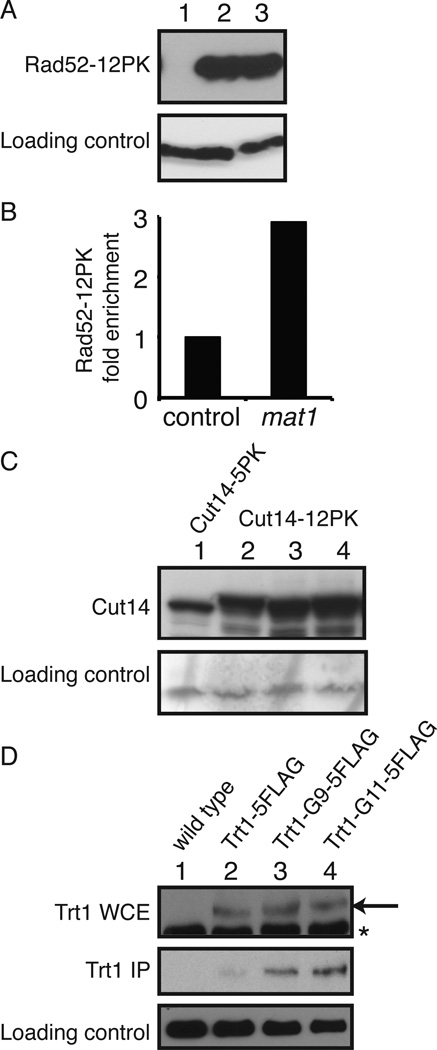

To confirm expression of 12Pk-tagged proteins, we generated a rad52(3´)-12Pk-kanMX6 cassette using the two-step PCR method (11). In this cassette, the 250 bp genomic DNA upstream of the rad52 stop codon is fused to 12Pk-KanMX6. This gene-targeting DNA cassette was integrated into the rad52 locus of wild-type S. pombe cells, and Rad52–12Pk expression was confirmed (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Analyses of tagged proteins. (A) The rad52(3´) -12Pk-kanMX cassette was amplified by the two-step PCR method using pFA6a-12Pk-kanMX, as described (4). The cassette was then integrated into the rad52 locus of wild-type S. pombe cells. Cells were grown in YES growth medium (yeast extract with supplements), and expression of the Rad52–12Pk protein was probed with the anti-Pk antibody. Immunoblotting of tubulin was performed as a loading control. Lane 1, wild-type cells; Lanes 2 and 3, Rad52–12Pk expressing cells. (B) Cells engineered to express Rad52–12Pk were processed for ChIP using the anti-Pk antibody, as described (7,17). Association of Rad52–12Pk with chromatin was monitored at the mat1 locus and a control locus. The relative association value of Rad52–12Pk at the control locus was set to 1. (C) S. pombe cells were engineered to express Cut14–5Pk (Lane 1) or Cut14–12Pk (Lanes 2 to 4), which were detected by Western blotting using the anti-Pk antibody. (D) Protein extracts were prepared from cells expressing the indicated versions of FLAG-tagged Trt1 from the trt1 locus. FLAG-tagged Trt1 was immunoprecipitated by anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich) and detected by anti-FLAG polyclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) (IP, immunoprecipitation). Expression of Trt1 was also confirmed by immunoblotting using the anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) (WCE, whole cell extract). Arrow shows FLAG-tagged Trt1, while asterisk indicates non-specific bands. Lane 1, wild-type cells; Lane 2, Trt1–5FLAG; Lane 3, Trt1-G9–5FLAG; Lane 4, Trt1-G11–5FLAG expressing cells.

Rad52 (previously called Rad22 in S. pombe) is a DNA repair protein and is recruited to DNA damage sites (12). To validate the functionality of the Rad52–12Pk protein, we performed a ChIP assay, showing that Rad52–12Pk associates with the programmed DNA damage site at the mating-type locus in wild-type S. pombe cells (Figure 2B). These results indicate that our vectors are useful for studying the molecular functions of various proteins expressed under physiological conditions.

The number of the Pk epitope-sequence tagged to a protein should influence the sensitivity of protein detection by Western blotting. Indeed, when we constructed cut14–5Pk and cut14–12Pk strains using the method described above, the level of Cut14–12Pk was much higher than that of Cut14–5Pk (Figure 2C), indicating that our 12Pk-tagging vectors improve protein detection sensitivity when compared with previous versions, such as 1Pk and 3Pk-tagging vectors (5,8).

We previously described a system of vectors for C-terminal 5FLAG tagging (4). Others have found that introducing a linker sequence allows flexibility between the epitope and the protein, enhancing antibody-epitope interaction (13). Therefore, to improve our 5FLAG-tagging system, we introduced 11 glycine sequences (G11) immediately before 5FLAG in the pFA6a-5FLAG-kanMX6 plasmid (4), resulting in pFA6a-G11–5FLAG-kanMX6 (Figure 1B). A shorter version with 9 glycine sequences (G9) is also available (pFA6a-G9–5FLAG-kanMX6) (Figure 1B). The reliability of this plasmid was also confirmed by introducing the G9–5FLAG or G11–5FLAG tag into the C terminus of Trt1, the catalytic subunit of the S. pombe telomerase. We also introduced the 5FLAG tag (without a linker) into the Trt1 C terminus as a control.

As shown in Figure 2D, Trt1–5FLAG (no linker), Trt1-G9–5FLAG, and Trt1-G11–5FLAG expressed from the trt1 locus were detected at similar levels in S. pombe whole cell extract (Figure 2D). This is to be expected because all vectors are designed to express proteins with five tandem copies of the FLAG epitope. It is known that Trt1 immunoprecipitation is inefficient when tagged with Myc immediately after the Trt1 C terminus. However, eight glycine sequences (G8) introduced between the Trt1 and Myc epitopes allow for efficient immunoprecipitation (13). Importantly, Trt1-G9–5FLAG was precipitated much more efficiently than Trt1–5FLAG (Figure 2D). In addition, the level of immunoprecipitated Trt1 further increased when the G11 linker was used (Figure 2D). Therefore, our pFA6a-G9–5FLAG-kanMX6 and pFA6a-G11–5FLAG-kanMX6 vectors are suitable for protein studies when direct epitope tagging compromises protein conformation and/or function.

To facilitate imaging analyses of proteins in S. pombe, we also constructed vectors for green fluorescent protein (GFP(S65T)) and monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP) genomic tagging. For both fluorescent tags, only antibiotic markers (kan, hph, nat) were available to the S. pombe research community. Therefore, we first replaced the PmeI-BglII kanMX6 fragment of pFA6a-GFP-kanMX6 (2) with ura4MX, resulting in pFA6A-GFP-ura4MX6 (Figure 1C). Then, the PacI-AscI GFP fragment of this vector was replaced with a PCR-amplified mRFP sequence, resulting in pFA6amRFP-ura4MX6 (Figure 1C). We also constructed pFA6A-GFP-bleMX6 (Figure 1C), providing a more flexible marker selection.

Finally, we describe new vectors for gene deletion in S. pombe based on the commonly used pFA6a-MX6-based plasmids, which contain antibiotic-resistance markers (2,9,10). However, these pFA6a-MX6 plasmids do not include nutritional markers. For this reason, the PmeI-BglII kanMX6 fragment of pFA6a-kanMX6 (2) was replaced with PCR-amplified S. cerevisiae LEU2, S. pombe his3+, and ura4+ fragments, generating pFA6a-LEU2MX6, pFA6a-his3MX6, and pFA6a-ura4MX6, respectively (Figure 1D). All of these vectors have structures similar to that of pFA6a-kanMX6, allowing us to conveniently and systematically manipulate genomic loci using primer sets already available for the pFA6a-kanMX system (2,11).

The kan, hph, and nat genes have also been used in S. cerevisiae (14), and similar pFA6a-MX vectors are available for S. cerevisiae research (3,8). Therefore many of the vectors described in this report may also be applicable to gene manipulation in S. cerevisiae. The plasmids constructed in this report (Table 1) and their maps will be available through the Addgene web site (http://www.addgene.org).

Table 1.

Summary of pFA6 derivatives for genomic FLAG- and PK-tagging and gene deletion useful in S. pombe.

| Vector name | Comments | Markers | Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PK-tagging vectors | pFA6a-6×GLY-V5-(marker) | C-terminal G6–1PK(V5)-tagging | KanMX6 | (8) |

| hphMX4 | (8) | |||

| pFA6a-12PK-(maker) | C-terminal 12PK(V5)-tagging | KanMX6 | This study | |

| hphMX6 | This study | |||

| natMX6 | This study | |||

| LEU2MX6 | This study | |||

| ura4MX6 | This study | |||

| FLAG-tagging vectors | pFA6a-5FLAG-(maker) | C-terminal 5FLAG-tagging | KanMX6 | (4) |

| hphMX6 | (4) | |||

| natMX6 | (4) | |||

| bleMX6 | (4) | |||

| pFA6a-6×GLY-FLAG-(maker) | C-terminal G6-FLAG-tagging | KanMX6 | (8) | |

| hphMX4 | (8) | |||

| pFA6a-6×GLY-3FLAG-(maker) | C-terminal G6–3FLAG-tagging | KanMX6 | (8) | |

| hphMX4 | (8) | |||

| pFA6a-(marker)-Pnmt1–3FLAG* | N-terminal 3FLAG-tagging | kanMX6 | (4) | |

| hphMX6 | (4) | |||

| natMX6 | (4) | |||

| bleMX6 | (4) | |||

| his3MX6 | (4) | |||

| pFA6a-(marker)-Purg1–3FLAG** | N-terminal 3FLAG-tagging | kanMX6 | (4) | |

| hphMX6 | (4) | |||

| natMX6 | (4) | |||

| bleMX6 | (4) | |||

| pFA6a-G9/G11–5FLAG-(maker) | C-terminal G9/G11–5FLAG-tagging | kanMX6 | This study | |

| kanMX6 | ||||

| GFP-tagging vectors | pFA6a-GFP(S65T) -(maker) | C-terminal GFP(S65T)-tagging | kanMX6 | (2,15) |

| hphMX6 | (10) | |||

| natMX6 | (10,16) | |||

| bleMX6 | This study | |||

| ura4MX6 | This study | |||

| pFA6a-(marker)-Pnmt1-GFP(S65T)* | N-terminal GFP(S65T)-tagging | kanMX6 | (2) | |

| natMX6 | (16) | |||

| pFA6a-mRFP-(maker) | C-terminal mRFP-tagging | kanMX6 | (10) | |

| hphMX6 | (10) | |||

| natMX6 | (10) | |||

| uraMX6 | This study | |||

| Disruption plasmids | pFA6a-(maker) | For gene deletion | kanMX6 | (2) |

| hphMX6 | (9,10) | |||

| natMX6 | (9,10) | |||

| bleMX6 | (9,10) | |||

| ura4MX6 | This study | |||

| his3MX6 | This study | |||

| LEU2MX6 | This study | |||

Expressed under the control of the nmt1 promoter; P3nmt1 and its weaker derivatives P41nmt1 and P81nmt1 are available.

Expressed under the control of the urg1 promoter.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jürg Bähler for generously donating plasmids, and Jordan Asam, Mukund Das, and Rochelle Vollmerding for technical assistance. We also express special thanks to Roger Y. Tsien for generous permission to use the mRFP containing plasmid. This study was supported by NIH (R01GM077604 to E.N. and DP2-OD004348 to K.N.) and the G. Harold & Leila Y. Mathers Foundation (to K.N). This paper is subject to the NIH public Access Policy.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: MCG, OI, KN, EN. Performed the experiments: MCG, OI, CN. Analyzed the data: MCG, OI, KN, EN. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: MCG, OI, CN, KN, EN. Wrote the paper: MCG, EN.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Wood V, Gwilliam R, Rajandream MA, Lyne M, Lyne R, Stewart A, Sgouros J, Peat N, et al. The genome sequence of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nature. 2002;415:871–880. doi: 10.1038/nature724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bähler J, Wu JQ, Longtine MS, Shah NG, McKenzie A, 3rd, Steever AB, Wach A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;14:943–951. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wach A, Brachat A, Pohlmann R, Philippsen P. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:1793–1808. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noguchi C, Garabedian MV, Malik M, Noguchi E. A vector system for genomic FLAG epitope tagging in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biotechnol. J. 2008;3:1280–1285. doi: 10.1002/biot.200800140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craven RA, Griffiths DJ, Sheldrick KS, Randall RE, Hagan IM, Carr AM. Vectors for the expression of tagged proteins in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Gene. 1998;221:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00434-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Southern JA, Young DF, Heaney F, Baumgartner WK, Randall RE. Identification of an epitope on the P and V proteins of simian virus 5 that distinguishes between two isolates with different biological characteristics. J. Gen. Virol. 1991;72:1551–1557. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-7-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka A, Tanizawa H, Sriswasdi S, Iwasaki O, Chatterjee AG, Speicher DW, Levin HL, Noguchi E, Noma K. Epigenetic regulation of condensin-mediated genome organization during the cell cycle and upon DNA damage through histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation. Mol. Cell. 2012;48:532–546. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Funakoshi M, Hochstrasser M. Small epitope-linker modules for PCR-based C-terminal tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2009;26:185–192. doi: 10.1002/yea.1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hentges P, Van Driessche B, Tafforeau L, Vandenhaute J, Carr AM. Three novel antibiotic marker cassettes for gene disruption and marker switching in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 2005;22:1013–1019. doi: 10.1002/yea.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato M, Dhut S, Toda T. New drug-resistant cassettes for gene disruption and epitope tagging in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 2005;22:583–591. doi: 10.1002/yea.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krawchuk MD, Wahls WP. High-efficiency gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe using a modular, PCR-based approach with long tracts of flanking homology. Yeast. 1999;15:1419–1427. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19990930)15:13<1419::AID-YEA466>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lisby M, Rothstein R, Mortensen UH. Rad52 forms DNA repair and recombination centers during S phase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:8276–8282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121006298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webb CJ, Zakian VA. Identification and characterization of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe TER1 telomerase RNA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:34–42. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein AL, McCusker JH. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1999;15:1541–1553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199910)15:14<1541::AID-YEA476>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longtine MS, McKenzie A, 3rd, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Driessche B, Tafforeau L, Hentges P, Carr AM, Vandenhaute J. Additional vectors for PCR-based gene tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe using nourseothricin resistance. Yeast. 2005;22:1061–1068. doi: 10.1002/yea.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noguchi C, Rapp JB, Skorobogatko YV, Bailey LD, Noguchi E. Swi1 associates with chromatin through the DDT domain and recruits Swi3 to preserve genomic integrity. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]