Abstract

It is now established that airway smooth muscle (ASM) has roles in determining airway structure and function, well beyond that as the major contractile element. Indeed, changes in ASM function are central to the manifestation of allergic, inflammatory, and fibrotic airway diseases in both children and adults, as well as to airway responses to local and environmental exposures. Emerging evidence points to novel signaling mechanisms within ASM cells of different species that serve to control diverse features, including 1) [Ca2+]i contractility and relaxation, 2) cell proliferation and apoptosis, 3) production and modulation of extracellular components, and 4) release of pro- vs. anti-inflammatory mediators and factors that regulate immunity as well as the function of other airway cell types, such as epithelium, fibroblasts, and nerves. These diverse effects of ASM “activity” result in modulation of bronchoconstriction vs. bronchodilation relevant to airway hyperresponsiveness, airway thickening, and fibrosis that influence compliance. This perspective highlights recent discoveries that reveal the central role of ASM in this regard and helps set the stage for future research toward understanding the pathways regulating ASM and, in turn, the influence of ASM on airway structure and function. Such exploration is key to development of novel therapeutic strategies that influence the pathophysiology of diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and pulmonary fibrosis.

Keywords: lung, asthma, inflammation, calcium, bronchoconstriction, bronchodilation, proliferation, extracellular matrix, development

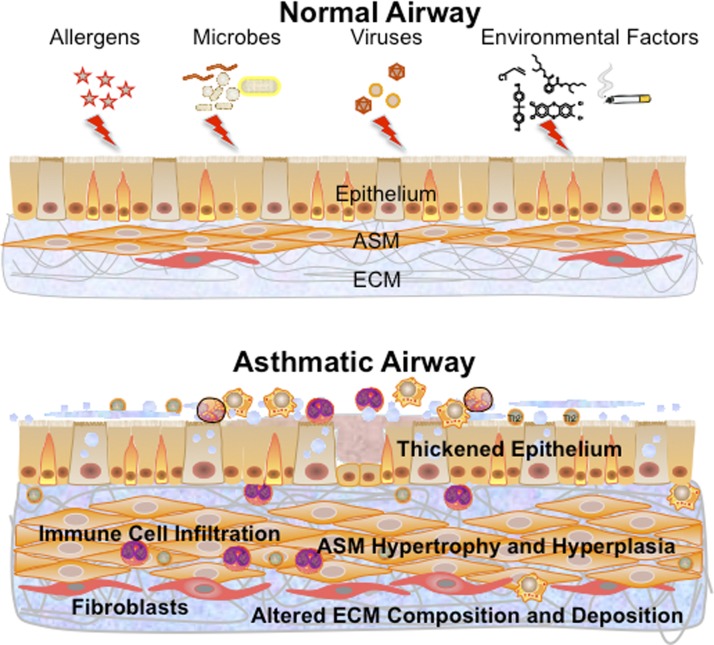

dysfunctional and excessive airway narrowing with impaired relaxation are hallmarks of diseases such as asthma (both in children and adults), bronchitis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Although structural changes to the diseased airway can involve a thickened (and also dysfunctional) epithelial layer, increased thickness of the airway smooth muscle (ASM) layer with varying levels of fibrosis are also key features in diseases of various etiologies, including allergy and infection, environmental exposures (e.g., cigarette smoke, toxins, and pollutants), and developmental abnormalities (Fig. 1). From a functional standpoint, the prime role of ASM is regulation of airway tone via a balance between the extent of contraction vs. dilation in response to local or circulating factors. Accordingly, factors that produce or enhance bronchoconstriction with concomitant impairment of dilatory mechanisms can result in increased airway tone that is typical in diseases such as asthma. Furthermore, structural changes induced by extrinsic factors can result in greater numbers (proliferation and hyperplasia) or size (hypertrophy) of ASM cells, contributing to reduced airway lumen, particularly in the face of ongoing airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR).

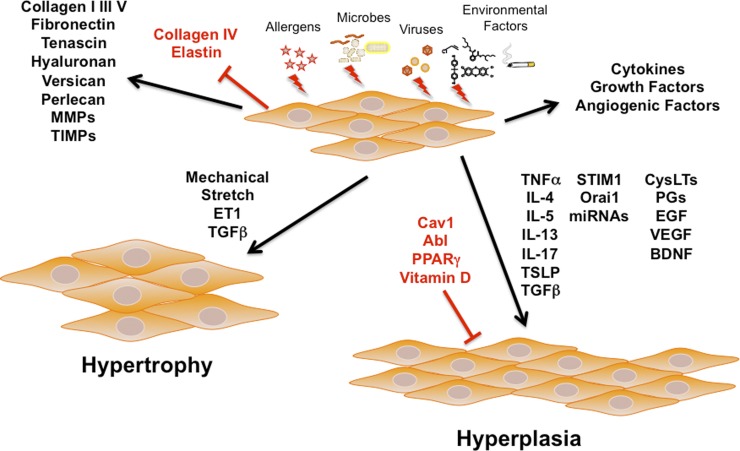

Fig. 1.

Transformations toward the asthmatic airway. Exposure of the normal airway to insults such as allergens, microbes, or viruses or to environmental factors such as pollutants, tobacco smoke, or nanoparticles results in changes throughout the epithelium, airway smooth muscle (ASM), and extracellular matrix (ECM). The asthmatic airway involves infiltration of a variety of immune cells, a thickened epithelium with goblet cell hyperplasia, increased mucus, a thickened, more fibrotic ASM layer with increased cell size (hypertrophy) and numbers (hyperplasia), along with altered ECM composition. Changes within the ASM layer can be a result of processes initiated or modulated by as well as involving ASM cells.

Despite the role of ASM in airway contractility per se being more “well established”, the mechanisms that regulate the “passive” response of ASM to extrinsic stimuli from airway innervation, other airway cell types (epithelium, fibroblasts, and immune cells), and/or circulating mediators are still being discovered, especially in the context of inflammation. It is now increasingly evident that, in diseases such as asthma and COPD and in environmental exposures, ASM are central to the induction and modulation of both structural and functional responses of the airway; i.e., ASM are active participants in airway responses to inflammation, infection, and injury. Here, ASM is now recognized to be a source of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins that drive structural changes, as a producer of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators that modulate the local immune environment and influence other resident cell types and even growth factors that affect cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis. All of these “ASM-derived” factors can, in turn, influence ASM structure and function via a myriad of signaling pathways, as well as other cell types in the airway. Accordingly, it becomes important to understand the mechanisms by which ASM respond to extrinsic stimuli and how ASM reciprocally modulate the extracellular, local environment. Such understanding is critical to the development of novel strategies to target enhanced airway reactivity and structural changes (remodeling) that occur in important diseases such as asthma, COPD, and even fibrosis.

The current perspective highlights some recent discoveries that reveal the central role of ASM in this regard. It is important to emphasize that the work highlighted here is by no means all-encompassing of the substantial body of recent literature by several investigative teams using a wide variety of complementary approaches and a range of species. Indeed, the impressive findings of all of these many studies only underline the importance of ASM in health and disease. By summarizing some of these discoveries, the intent here is to help set the stage for future research toward exploring the pathways regulating ASM and, in turn, the influence of ASM on airway structure and function in the context of understanding disease pathophysiology and treatment.

ASM, [Ca2+]i, and Contractility

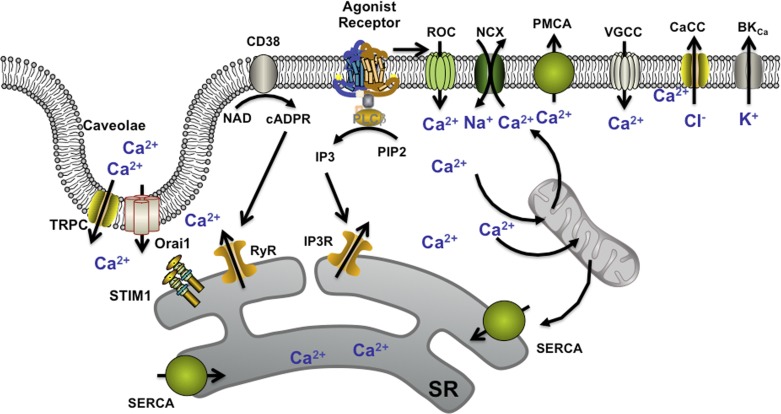

The major mechanisms by which elevation of [Ca2+]i occurs in ASM in response to agonist have been recently reviewed (17, 145, 186, 231, 261, 278, 285, 335). Although there are species differences in the contribution of specific pathways, some common mechanisms are well recognized. Activation of Gq-coupled receptors by a range of bronchoconstrictor agonists as well as a more complex and less-understood role for Gi-coupled receptors have been identified (20, 59, 227, 335). [Ca2+]i elevation involves voltage-gated, receptor-operated, store-operated, and nonspecific Ca2+ influx, as well as sarcoplasmic reticulum release through channels activated by the phospholipase C (PLC)/inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and CD38/cyclic ADP ribose (cADPR) pathways (IP3-sensitive and ryanodine receptor channels). Mechanisms such as the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA), the bidirectional Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), and mitochondrial buffering help limit [Ca2+]i and restore levels following removal of agonist (Fig. 2). Beyond [Ca2+]i, the Ca2+-calmodulin-myosin light chain (MLC) kinase-MLC cascade regulates contractility mediated by actin-myosin interactions. Furthermore, Ca2+ sensitization for contraction involves activation of the RhoA/Rho kinase pathway, which serves to prevent desensitization of the contractile machinery from MLC phosphatases. Although such mechanisms have been extensively studied in different smooth muscle types, more recent work has revealed the complexity in the expression and function of these mechanisms and their finer regulation by plasma membrane, as well as intracellular signaling pathways, many of which are important in inflammatory signaling and in the pathophysiology of airway diseases. Thus the area of [Ca2+]i regulation in ASM continues to be a topic of substantial research interest in the respiratory and lung biology community.

Fig. 2.

Mechanisms of [Ca2+]i regulation in ASM. A number of regulatory mechanisms are well recognized, including agonist-induced G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR)-based production of inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and action of the ectoenzyme CD38 in producing the second messenger cyclic ADP ribose (cADPR), leading to sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release from IP3 receptor and ryanodine receptor (RyR) channels, respectively. Additionally, Ca2+ influx can occur through receptor-operated channels (ROC), voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs), and perhaps through the bidirectional Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX). Depletion of SR Ca2+ stores can lead to store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) mediated by the SR Ca2+-sensing protein stromal interacting molecule (STIM1) and the plasma membrane influx channels Orai1 and canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) (both being expressed with caveolae). Elevated [Ca2+]i can be sequestered by the SR via the Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA), by mitochondrial buffering, and plasma membrane efflux mechanisms such as the plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA) or by membrane hyperpolarization due to BKCa and Ca2+-activated chloride channels (CaCC). PLC, phospholipase C; cADPR, cyclic ADP ribose; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate.

GPCRs.

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are a superfamily of plasma membrane proteins that transduce extracellular signals, resulting in intracellular cascades, leading to diverse cellular functions. The importance of GPCRs in the airway lies in the fact that many of the drugs currently in use for management of diseases such as asthma and COPD target these mechanisms, particularly in ASM. Traditional bronchoconstrictor agonist receptors for acetylcholine (ACh), histamine, and endothelin act via the well-studied Gq-coupled pathway, activating the PLC-IP3 pathway in elevating [Ca2+]i. Activation of the Gi-coupled pathway reduces cAMP and thus indirectly promotes contractility. Although much of the previous work in this area has focused on expression and function of different GPCRs (typically Gq, Gi, and Gs) in the context of ASM contractility/relaxation, there is increasing recognition that GPCRs acting alone, or in conjunction with other pathways such as receptor tyrosine kinases (18, 20, 59, 155, 162), can contribute to the “synthetic function” of ASM via cell proliferation/growth and secretion of growth factors and inflammatory mediators, thus influencing airway remodeling and the local inflammatory milieu (e.g., see Refs. 20 and 59 for review). However, it is important to first recognize some recently identified GPCR mechanisms that may help launch new avenues in bronchodilatory therapies and perhaps help target other aspects of ASM dysfunction as well. Furthermore, recent advances in understanding GPCR regulation per se in terms of desensitization, constitutional activation of receptors, and biased agonism (59, 227, 285) may help drive novel approaches to targeting these mechanisms and their downstream targets.

There has been considerable excitement regarding the identification of bitter taste receptors (BTRs) as novel bronchodilators (4, 43, 61, 82, 241, 262, 352). Of the 25 members in this family of GPCRs (type 2, bitter taste receptors, TAS2Rs; Fig. 3) activated by bitter tastants such as chloroquine and saccharin, six are prominently expressed and functional in human ASM, with three dominant TAS2Rs (subtypes 10, 14, and 31) (61). TAS2Rs differ from many other GPCRs in their ability to bind a range of bitter compounds with relatively low specificity and affinity. A fascinating aspect of TAS2Rs is the novel finding that their activation actually results in elevated [Ca2+]i levels in ASM [e.g., via IP3-mediated sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release] but leads to bronchodilation more efficaciously than β-agonists, making TAS2Rs highly appealing targets for enhancing bronchodilation (although their eventual clinical application may be determined by the concentrations required in disease and the problem of desensitization; 256). What is less clear are the mechanisms underlying the unexpected discrepancy between elevated [Ca2+]i and bronchodilation, especially when the dilatory effect does not appear to involve cyclic nucleotides. Alternative mechanisms have been proposed, including membrane hyperpolarization via the iberiotoxin-sensitive Ca2+-activated K (BKCa) channels (61, 241), especially in the context of compartmentalized signaling (superficial barriers). In this regard, recent studies in the guinea pig airway (241) suggest that different bitter tastants may work through differential mechanisms in inducing bronchodilation and may further be differently effective depending on the bronchoconstrictor in play. For example, denatonium (which activates the type 4 and 10 receptors) selectively inhibits constriction induced by muscarinic receptors, whereas chloroquine (which activates type 3 and 10) broadly inhibits contractions evoked by prostaglandin E2, thromboxane receptor activation, leukotriene D4 (LTD4), histamine, and antigen. Here, these TAS2R agonists may also differentially work through BKCa channels. Interestingly, none of PKA, PKC, or PKG appear to be involved. However, given that membrane potential is not as powerful a signal for contractility/relaxation in ASM as it is in vascular smooth muscle (but see below regarding novel findings), but that agonists such as histamine in fact depolarize the plasma membrane, and additional studies indicate a role for voltage-gated L-type channels (352), other pathways for TAS2R effect need to be considered. Certainly, given the variety of [Ca2+]i regulatory mechanisms within ASM (e.g., Fig. 2), a number of possibilities exist. Regardless, of which mechanisms are involved, the discordance between elevated [Ca2+]i and reduced contractility will need to be reconciled. If reduced contractility per se is the final outcome, inhibition of Ca2+ sensitivity and sensitization pathways need to be examined. Although these potential pathways are yet to be examined, the novelty and appeal of TAS2Rs is clear. Recent data showing that TAS2R activity is maintained even when β2 adrenoceptors (β2ARs) are desensitized are particularly interesting (4) because this lack of physiologically relevant cross desensitization may allow for use of bitter tastants as an adjunct or rescue therapy during ongoing β2AR desensitization as a result of chronic use of β2-agonists. Of course, more work is needed to determine the extent of TAS2R desensitization per se because limited data show a modest degree of desensitization (20–30%) in human ASM and monkey bronchus (256), which may be amplified in the diseased airway. Here, it may also be relevant to consider whether “standard” therapies such as glucocorticoids, which are thought to prevent β2AR desensitization, are equally effective in preventing TAS2R desensitization (43). Furthermore, given that a number of agonists and mediators may concurrently act on ASM, it may be helpful to determine whether TAS2Rs interact with other receptors (e.g., via heterodimerization). Finally, it will be important to establish the pattern of changes in TAS2Rs during the development and progression of diseases such as asthma or COPD, so the utility of bitter tastants as therapeutic agents could be further tested.

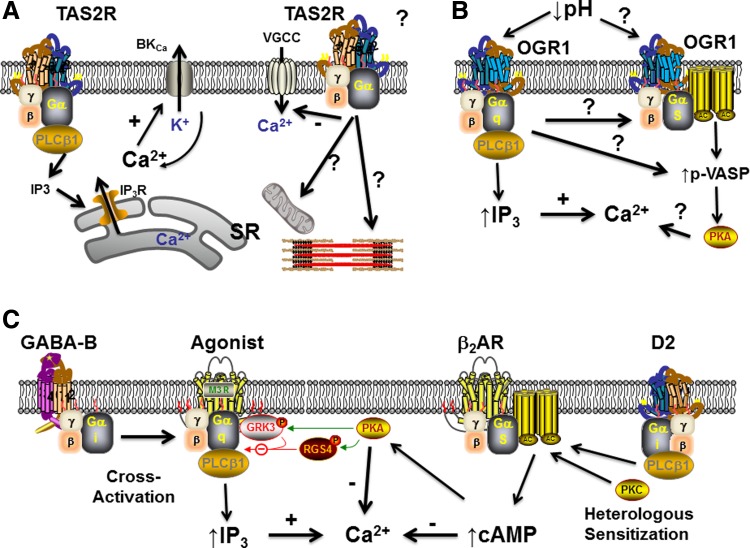

Fig. 3.

Novel GPCR-based signaling mechanisms in ASM. A: effect of bitter tastants such as chloroquine and saccharin on bitter taste receptor (TAS2R) GPCRs in ASM has been a topic of substantial recent interest. Working through a Gq protein-coupled mechanism (where the α-subunit may represent gustducin, transducin, or α1), TAS2R activation leads to increased SR Ca2+ release via IP3 receptor channels and elevated [Ca2+]i levels but intriguingly results in bronchodilation via mechanisms that remain to be established. Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BKCa) and inhibition of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels are thought to be involved, but pathways such as inhibition of other Ca2+ influx mechanisms, mitochondria, or contractile mechanisms downstream to Ca2+ may also be relevant. B: a novel, intriguing GPCR mechanism recently identified in ASM is an extracellular pH-sensitive pathway, ovarian cancer G protein-coupled receptor 1 (OGR1/GPR68), that on the one hand appears to work via Gq to increase [Ca2+]i via the IP3 mechanism, but on the other hand also activates the protein kinase A cascade either directly through Gq or perhaps through interactions with Gs. VASP, vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein. C: in contrast to the novel TAS2R and OGR1 pathways, there is now increasing evidence that the GABA and dopaminergic systems (well known in neuroscience) also have interesting effects in ASM. Activation of the metabotropic GABA-B receptor results in a Gi-coupled cross activation of Gq-coupled receptors of bronchoconstrictor agonists, leading to increased [Ca2+]i. On the other hand, prolonged dopaminergic signaling via a D2-like, Gi-coupled pathway leads to enhancement of the Gs-coupled β2-adrenoceptor (β2AR) system, thus increasing cAMP and promoting bronchodilation. GRK3, G protein-coupled receptor kinase; RGS4, G-protein signaling 4.

Another intriguing, recently identified signaling mechanism in ASM is the family of proton-sensing GPCRs that can respond to variations in extracellular pH (122, 196, 219, 269). Two of them (GPR4 and T cell death-associated gene 8 or GPR65) are Gs coupled, whereas the ovarian cancer G protein-coupled receptor 1 (OGR1 or GPR68; Fig. 3) is Gq coupled. The appealing aspect of these novel pathways is in the idea that airway reactivity could be modulated directly by extracellular pH beyond airway irritability induced by pH or acid effects on sensory neurons. Although the expression pattern and function of these novel receptors are still under investigation, OGR1 mRNA has been found in human ASM (122, 269) (while airway epithelium expresses multiple of these GPCRs; 269). The role of OGR1 activation has been characterized in vascular smooth muscles (304) and more recently in human ASM (304). Reductions in extracellular pH to 6.3 result in mobilization of [Ca2+]i although the mechanisms by which Ca2+ is elevated remain to be determined. Here, it may be interesting to explore a range of plasma membrane influx mechanisms, based on information from other lung cell types regarding pH or acid effects. For example, proton activation of vanilloid receptor subtype 1 (transient receptor potential vanilloid 1, TRPV1) on sensory neurons can induce membrane depolarization and stimulate local release of kinins (98, 253). In addition to expression in airway neurons (70, 176), there is limited evidence for TRPV1 in nonneuronal airway cells such as epithelium (298) and ASM (354) but considerable data on the expression of kinin receptors in ASM (173, 200, 252, 322). Thus it would be interesting to determine whether OGR1 can indirectly influence these mechanisms. There has been considerable interest in acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) on sensory neurons (98, 99, 172), but the limited evidence in ASM suggests that ASICs may actually contribute to pH-induced ASM relaxation (70). In PC12 cells, changes in extracellular pH can influence store-operated Ca2+ influx that is dependent on the SR Ca2+ protein stromal interacting molecule 1 (STIM1) (299). Given the important role of STIM1/Orai1 in human ASM (80, 137, 225, 264, 292, 357), it is possible that OGR1 could modulate store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) by enhancing STIM1 interactions with Orai1 or other channels that contribute to Ca2+ influx, particularly canonical transient receptor potentials (TRPCs) (80, 338). Furthermore, the limited data in human ASM suggest that OGR1 can further result in p42/44 MAPK phosphorylation (269) and IL-6 production (122) and therefore have more complex effects in the setting of disease. In this regard, an intriguing finding is that OGR1 also promotes phosphorylation of the PKA substrate vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein in response to reduced extracellular pH (269). This effect may reflect a duality of Gq/Gs activation by OGR1 or be independent of the expected Gq activation and thus direct coupling to Gs. Regardless of which mechanisms are at play, the emerging data on proton-sensing GPCRs are of considerable interest from the perspective of reactive airway diseases in several aspects. For example, acid fog is an environmental issue in developing countries and is associated with increased incidence of asthma (74). Gastroesophageal reflux disease and microaspiration of gastric contents can induce and exacerbate asthma (251–253). Even in asthma from other causes, and in COPD, airway inflammation is known to result in reduced local pH (157). Accordingly, developing drugs or other techniques to preferentially activate the Gs aspect of OGR1 signaling (or alternatively inhibiting Gq only) would be highly appealing.

Although concepts such as BTRs and proton-sensing receptors in the context of airway reactivity are emerging, there have been very interesting discoveries in the novel roles for an agonist very well known in the nervous system: γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the mammalian central nervous system. GABA is known to act at both ligand-gated ionotropic GABA-A receptors as well as G protein-linked metabotropic GABA-B receptors, the latter being typically linked to Gi. Both GABA and functional GABA-B receptors have been detected in a range of peripheral tissues (69, 84, 328). Initial clinical findings of worsened airway responses of asthmatics to methacholine in the presence of the GABA-B receptor agonist baclofen (62) raised the possibility of this mechanism within airways. Recent findings suggest the functional expression of GABA-B receptors in airway smooth muscle (221) as well as epithelial (206) cells. The interesting functionality of these receptors in ASM has been recently demonstrated in human and guinea pig ASM (76–78, 205, 207, 350) (Fig. 3). Although acting through Gi (blocked by pertussis toxin), both baclofen and GABA significantly increase the synthesis of IP3 and elevate [Ca2+]i (effects blocked by selective GABA-B antagonists, whereas GABA-A receptor agonists have no effect) (205). This unexpected finding appears to involve a Gβγ-mediated direct effect on PLC-β leading to IP3 production as well as a potentiation of Gq-mediated signaling (e.g., bradykinin), thus contributing to crosstalk between Gi and Gq pathways, leading to contraction. These novel data point to a very intriguing bronchoconstrictor mechanism that could in fact be targeted relatively easily given the availability of specific agonists and antagonists.

Akin to GABA, another atypical signaling pathway that has garnered recent interest is dopaminergic signaling in the airway (32, 208, 209). Dopamine effects are well known in several organ systems. “D1-like” dopamine receptors couple to Gs, whereas “D2-like” receptors (D2, D3, and D4) couple to Gi (204). Clinically, inhaled dopamine induces bronchodilation in patients with asthma, but the underlying mechanisms are not well understood. Indeed, functional expression of dopamine receptor subtypes in ASM have only recently been described (208). Although based on the physiological effects, a D1-like/Gi-linked pattern is to be expected, and the limited data actually suggest an intriguing functionality. In sensory neurons of the airway, a D2-like receptor has been identified (226). In human as well as guinea pig ASM, D2 receptor mRNA and/or protein has been reported (208, 209). Acute activation of D2 receptor (quinpirole) inhibits adenylyl cyclase activity (208), consistent with the classical function of Gi-coupled receptors that inhibit adenylyl cyclase (AC) activity and reduce cAMP (thus preventing bronchodilation). However, in ASM, chronic D2 receptor activation with quinpirole paradoxically enhances AC activity via heterologous sensitization (Fig. 3), which involves PLC and PKC, resulting in bronchodilation. Such sensitization is not unique to dopamine receptors, being observed in adenosine and adrenergic and opioid receptors (329, 330). Nonetheless, the ability of dopamine receptors to induce bronchodilation provides yet another novel avenue to target excessive bronchoconstriction in airway diseases.

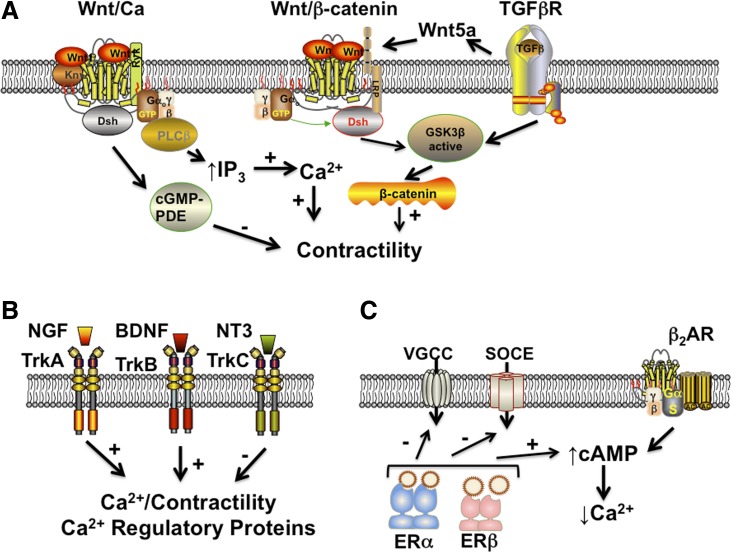

Beyond the usual and even unusual GPCRs, there has been a limited number of studies examining the novel role of Wnt signaling in ASM (8, 163, 325, 347, 358) (Fig. 4). Wnt signaling begins with one of the Wnt proteins binding the extracellular domain of a Frizzled (Fz) family receptor that spans the plasma membrane to constitute a distinct family of GPCRs (184). Such signaling may be facilitated by coreceptors typically of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) family such as lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP)-5/6, Ryk, and ROR2. Thus Wnt represents a transmembrane signaling mechanism that may serve to integrate inputs with pleiotropic intracellular cascades via canonical β-catenin-dependent and -independent pathways and non-canonical Wnt/Ca2+ pathways. The emerging major theme of Wnt signaling in ASM appears to be related to airway remodeling, particularly in the context of TGF-β signaling (see below). However, limited data are now highlighting a role for both TGF-β itself elevating [Ca2+]i in ASM via enhanced Ca2+ influx (79) as well as SR Ca2+ release (154) and importantly the noncanonical Wnt/Ca2+ pathway (163). Here Wnt5A is markedly induced in response to TGF-β and is required for ECM production by ASM (163). However, Wnt5A also engages noncanonical WNT signaling pathways evidenced by lack of TGF-β effects when [Ca2+]i is inhibited (163). Here, the noncanonical Wnt/Ca2+ pathway can enhance SR Ca2+ release via PLC/IP3 or blunt [Ca2+]i via cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase (PDE). Certainly, it is possible that even the canonical Wnt pathways are at least indirectly involved in modulating ASM contractility via mechanisms involving β-catenin (347) (e.g., see below) or as yet unexplored increases in expression of [Ca2+]i or contractility proteins. The appeal of the Wnt signaling pathways lies in the potential for both biased agonism (19, 20, 193) (or antagonism) based on the desired effect of altered airway tone vs. remodeling.

Fig. 4.

Novel signaling cascades in ASM. A: activation of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β receptors in ASM leads to increased expression of Wnt5a that can in turn activate either the Wnt/GSK3β/β-catenin system in promoting contractility or alternatively the noncanonical Wnt/Ca system that increases [Ca2+]i via IP3. Conversely, the Wnt/Ca system could modulate contractility by activating cGMP-specific phosphodiesterases (PDE). B: although well recognized in the nervous system, there is now considerable evidence that the receptor tyrosine kinase family of neurotrophic receptors (tropomyosin-related kinases; Trks) are expressed and functional in ASM. The neurotrophin nerve growth factor (NGF) acts via TrkA, whereas brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) acts through TrkB to enhance [Ca2+]i and expression of Ca2+ regulatory proteins to promote contractility. Conversely, neurotrophin-3 (NT3) acts via TrkC to blunt Ca2+ and contractility. C: given sex differences in allergic airway diseases, the mechanisms by which sex steroids such as estrogens can influence ASM are being explored. Limited data suggest that estrogen receptors (ERs) can inhibit VGCC and SOCE to reduce [Ca2+]i while separately increasing cAMP that also aids in bronchodilation, perhaps by potentiating β2AR effects.

With regard to GPCRs as targets for bronchodilation, a limiting issue may be the concept of receptor desensitization, typified by β2ARs, but also present for TAS2R, for example (256). There is now increasing interest in techniques for preventing desensitization to promote and prolong the activity of bronchodilators (19, 21, 227). Here, the focus has been on mechanisms such as the G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRKs) that normally limit GPCR activation and the β-arrestins involved in receptor internalization. For example, inhibiting GRK2/3 or blocking β-arrestin-2 can selectively enhance β2AR signaling in human ASM (60). Here, corticosteroids, a mainstay of asthma therapy, can also help restore β-agonist sensitivity and prevent desensitization although such effects may be specific to particular β-agonist agents (47). With TAS2R, recent but limited data based on prevention of desensitization by dynamin but lack of effect of PKA or PKC antagonists (256) also suggest a role for GRK/β-arrestins. Certainly, much work is needed to identify techniques or complementary drugs to target specific GRK isoforms or β-arrestins to enhance or maintain the functionality of particular bronchodilator therapies, be it β2-agonists or bitter tastants and other novel therapies in the future. Along the lines of GRKs and β-arrestins, is the increasing recognition that regulators of G-protein signaling (RGS) may play a role in airway contractility (as well as remodeling) (49, 64, 289, 290, 340, 343). A specific RGS usually prevents the continued activation of multiple G proteins, and thus upregulation or downregulation of RGS can have broad effects. Here, one study identified increased RGS4 as being inhibitory to ASM contractility in severe, recalcitrant asthma but interestingly promoting a proliferative phenotype of ASM (49). Separately, RGS2, an inhibitor of multiple Gq-coupled receptors expressed in human and murine ASM, is downregulated in ovalbumin-sensitized/challenged mice as well as in the lungs of asthmatic humans (340). These emerging data point to multiple novel strategies to reduce bronchoconstriction while enhancing bronchodilation. Here a key limitation may be the widespread expression and different functions of GRK, β-arrestin, and RGS isoforms within different cell types of the airway, necessitating targeting of the most relevant pathways within ASM per se.

In addition to preventing desensitization of specific receptors, there is increasing interest in identifying ligands with biased agonism toward different GPCRs (19, 20, 193). Certainly, partial vs. full agonists acting at the same receptor are known to produce effects of different magnitude. However, different agonists, or stereoisomers of a single agonist, can work through the same receptor to activate different downstream pathways to different extents, i.e., it is the ligand that determines the direction of signaling, rather than the GPCR, presumably by differential stabilization of the activation state of the receptor. Such biased agonism has been demonstrated in the context of asthma and ASM for β2AR, which can activate Gs to enhance cAMP (and thus be of benefit by enhancing bronchodilation for example) vs. their ability to work via the β-arrestin-mediated MAPK pathway, which may be detrimental in terms of contractility, promoting cell proliferation, and remodeling (60, 326). Thus the potential to direct β2AR signaling toward a beneficial pathway while avoiding activation of detrimental mechanisms is a highly appealing goal for drug development. In this regard, further beneficial cAMP signaling may be produced by better understanding of how cAMP itself is compartmentalized and regulated in ASM cells, especially via A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs). A recent study identified AKAPs in human ASM (118) and found that they regulate compartmentalized cAMP accumulation in response to β2AR stimulation, raising the possibility that the combination of an agonist biased toward greater cAMP signaling with another that promotes local cAMP accumulation to synergetically enhance bronchodilation may be even more beneficial.

Non-GPCR-based mechanisms.

In addition to bronchoconstrictors or bronchodilators that work through GPCR mechanisms, there is now considerable evidence for signaling in ASM that involves nuclear hormone receptors (a classical example being the glucocorticoid receptor), tyrosine kinases, and serine/threonine kinases.

In terms of serine/threonine kinases, there has been much focus on the receptor for TGF-β and its interactions with other receptors (e.g., Wnt as above; Fig. 4) (9, 79, 121, 163, 201, 216, 217, 347). For example, expression of contractile proteins is enhanced in human ASM cells exposed to both methacholine and TGF-β (216, 217). However, it appears that, consistent with its role in other cell types, TGF-β largely affects ASM in the context of remodeling (121, 216, 217, 273) (see below).

Previous work on families of receptor tyrosine kinases such as endothelial growth factor (EGF) receptors (171, 214, 270, 284), insulin receptors (54, 55, 90, 128, 224, 271), or platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptors (123) has shown a role for these receptors in airway contractility and/or remodeling. However, a number of recent studies have found that the Trk family of receptors (RTK class VII; Fig. 4) that are responsive to the neurotrophin family of growth factors (238) has novel, diverse roles in ASM, including enhancing [Ca2+]i and contractility, particularly in the setting of inflammation (120, 200, 223, 236, 239, 248, 268, 344). Neurotrophins such as nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) are well recognized in the nervous system for both long-term genomic effects on neuronal growth, differentiation, and survival (181), as well as nongenomic, rapid effects of enhancing [Ca2+]i and neurotransmitter release (24, 159). There is now convincing and increasing evidence for a number of neurotrophins being expressed in peripheral tissues including lung, with increased expression in asthma, COPD, and even lung cancer (see Refs. 119, 238, 257, and 345 for review). However, the functional role of neurotrophins in the airway are still under investigation. Here, recent data suggest that NGF is released by airway nerves in response to irritants [e.g., ozone (120, 322) or cigarette smoke (336)], allergens (346), and infectious agents (38) contributing to irritability and enhanced contractility. NGF can also be derived from airway epithelial cells, for example following viral or bacterial infections (38, 222). The presumed target of the released NGF is ASM, given expression of the cognate TrkA receptors in ASM (75, 213, 222, 238). However, there are now considerable data that ASM also expresses the TrkB and TrkC receptors for BDNF/neurotrophin 4 and neurotrophin 3, respectively (200, 213, 236, 239, 268, 291, 345). Here, it appears that ASM itself can release BDNF (200, 324) both at baseline and in response to inflammatory stimuli. Importantly, BDNF can nongenomically enhance ASM [Ca2+]i (236) and potentiate the effects of receptors for neurally derived factors such as the neurokinins (200). BDNF further appears to play a role in airway remodeling (5) (see below). The relevance of these novel pathways is the highlighting of ASM as both a source of growth factors and a recipient of such factors secreted by ASM, as well as surrounding cell types, resulting in pleiotropic effects that are also involved in asthma and other airway diseases. Whether this concept is also valid for other secreted growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (or even TGF-β) is not known and is certainly worthy of exploration in the context of establishing ASM as more than a passive recipient in airway structure and function.

There is now increasing interest in the role of sex differences and sex steroids in the context of lung diseases, particularly asthma and COPD, given clinical evidence for peripubertal and perimenopausal switches in the incidence of asthma and increased asthma in the elderly male (25, 87, 277, 308, 323). However, understanding of the mechanisms by which sex steroids influence ASM is still very much in its infancy. As nuclear receptors, estrogens, progesterone, and/or testosterone may be expected to alter gene regulation, and the clinical evidence for altered airway reactivity or differences in asthma especially with changing estrogen levels is consistent with this concept. However, recent studies show that, akin to their role in vascular smooth muscle, estrogens can rapidly and nongenomically reduce [Ca2+]i in human ASM, largely via blunting of Ca2+ influx via L-type Ca2+ channels and SOCE (but surprisingly not via the expected BKCa channels) (311) (Fig. 4). Here, estrogens appear to act via ER-α and ER-β to enhance cAMP and potentiate adrenoceptor action (309). Whether ERs also influence SR Ca2+ release in ASM is not entirely clear, but, given that nonnuclear ERs (potentially in the plasma membrane) are involved, estrogen effects on PLC or CD38 may be relevant. Furthermore, estrogens can indirectly influence airway contractility by enhancing epithelial NO release (306, 307). Overall, these interesting data demonstrate that estrogens may play an important role in bronchodilation, and it may be possible to modulate ER signaling in the context of asthma, particularly with an eye on β2-agonist-sparing therapies. What remains to be established is whether estrogens, as steroid receptors of the same family as for glucocorticoids, could potentially also alter the response of ASM to inflammation. Here, the differential roles of ER-α and ER-β in the context of inflammation remain to be elucidated. Furthermore, it is important to consider whether and how progesterone influences ASM, given limited data of its effects on airway function and asthma (104, 109, 126, 295). A similar question can be raised regarding a “protective” effect for testosterone acting via androgen receptors (33, 36, 37, 158).

Ca2+ Regulatory Pathways

Second messengers.

While the importance of the PLC/IP3 and CD38/cADPR pathways in ASM is now well recognized (17, 145, 186, 231, 261, 285), several recent studies have explored how other mechanisms may indirectly regulate either second-messenger pathway, resulting in either elevated [Ca2+]i or in aiding bronchodilation. Certainly, both OGR1 and TAS2R can increase IP3 and consequent SR Ca2+ release. Conversely, quercetin, a naturally occurring PDE4 blocker has been shown to prevent methacholine-induced increases in airway resistance in mice as well as reduce [Ca2+]i in human ASM cells by inhibiting PLC-β and reducing IP3 production (305). Along the line of natural bronchodilators, constituents of ginger such as 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol, or 6-shogaol inhibit PDE4D, whereas 8-gingerol and 6-shogaol also inhibit PLC-β activity, both of which may contribute to reduced IP3 levels (310, 312). In terms of CD38, several previous studies have demonstrated that inflammation can substantially increase CD38 levels and thus enhance cADPR-mediated [Ca2+]i and contractility (101, 125, 141–144, 147, 300, 301), and more recent data show that altered CD38/cADPR signaling contributes to the asthma phenotype (141). Here, cytokines such as TNF-α are thought to produce greater increases in CD38 in asthmatic ASM via increased transcriptional regulation involving ERK and p38 MAPK activation [but not NF-κB or activated protein (AP)-1, which do regulate CD38 in nonasthmatics] (144). Furthermore, in human asthmatic ASM, TNF-α attenuates expression of the microRNA miR-140–3p that targets the CD38 3′-UTR and influences CD38 stability (142). Interestingly, the same miRNA also modulates TNF-α effects on p38 MAPK and NF-κB, both of which are relevant to CD38 regulation. Given the relevance of these pathways to a number of inflammatory cytokines, elevated CD38 in airway inflammation likely plays a large role in the observed increases in contractility in the inflamed/asthmatic airway.

Influx/efflux mechanisms.

Previous studies have established the existence of voltage-gated Ca2+ influx in ASM (145, 231, 261, 285). Indeed, there is recent evidence that P2X-mediated ligand-gated ion channels can enhance influx via L-type Ca2+ channels (102). However, unlike its clear role in cardiac muscle or even vascular smooth muscle, a continuing question is the relative importance of membrane potential and voltage changes in ASM contractility or relaxation (115, 131–133, 179). Here, it may be inappropriate to ignore the contribution of membrane potential because other regulatory mechanisms may be at play that are not completely understood. For example, blockade of K+ channels does cause contraction (131), whereas voltage-gated T-type calcium channels can increase force (115, 132). Additionally, membrane potential can regulate calcium sensitization via Rho kinase activity (179). Furthermore, the role of chloride regulation in ASM is not well understood and may be important in ASM contractility vs. relaxation (130). For example, a recent study showed that GABA, acting via the ionotropic GABA-A receptors can potentiate β2AR-mediated relaxation but in fact causes membrane depolarization involving chloride-mediated currents (78). Although elevated [Ca2+]i can activate very small-conductance Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels, opening of such channels should cause depolarization and thus contraction. For example, recent data in ovalbumin sensitized/challenged mouse airways showed a role for transmembrane protein 16A (TMEM16A) and less so for TMEM16B Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in enhancing airway contractility (351). Furthermore, previous studies have shown that agonists such as ACh can induce repetitive [Ca2+]i oscillations and waves (148, 237), which can be regulated by Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (215). Accordingly, understanding the role of Cl− movement during ASM contraction vs. relaxation may be relevant (130). In terms of bronchodilation, activation of K+ channels to hyperpolarize the membrane may be important as well, as recently demonstrated for Kv7 channels in ASM (29). Furthermore, there is now convincing evidence for the bidirectional NCX in ASM (1, 2, 116, 178, 243, 266). Although the role of NCX as a largely efflux pathway (with variable influx contribution when reversed) is established in cardiac muscle, the conditions under which NCX contributes to [Ca2+]i regulation in ASM are less clear. Certainly, NCX1 expression is robust in ASM of different species (116, 266) and is upregulated with inflammation (266). Both robust efflux and influx modes can be demonstrated, suggesting that elevation of [Ca2+]i may occur under certain conditions (e.g., to act as yet another source for store refilling), whereas removal of [Ca2+]i may contribute to bronchodilation, especially following agonist stimulation (116, 266). The relevance of increased NCX expression in airway inflammation is not clear because it may contribute to increased reactivity, as is thought to be the case for store-operated influx mechanisms, such as Orai1 and STIM1 (178). Overall, these emerging data show that, beyond intracellular Ca2+ release/reuptake, plasma membrane voltage-dependent mechanisms may be important in ASM function, which should generate substantial interest in the idea of developing drugs that target Ca2+ influx/efflux, Cl−, or K+ channels in enhancing bronchodilation.

In ASM, sequestration of elevated [Ca2+]i is largely mediated by SERCA. There is now substantial interest in the idea that reduced SERCA expression/function occurs in the asthmatic ASM and with inflammation (185, 186, 203, 267), allowing for [Ca2+]i to, not only remain elevated, but also contribute to the remodeling process. Surprisingly, there are little to no data on the calmodulin-dependent plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA; a major efflux mechanism in other cell types) beyond its localization to caveolae (52). Unpublished evidence (personal communication, E. E. Strehler) suggests that inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α can downregulate PMCA expression and thus allow for elevated [Ca2+]i. Given the plasma membrane location of this mechanism, PMCA may be a prime target for intervention in diseases such as asthma.

Beyond production of ATP, there is now abundant information regarding the Ca2+ buffering role of mitochondria (6, 46, 255). Indeed, cytosolic Ca2+ serves as a stimulus and regulator for mitochondrial energy production to match demand, and, in turn, mitochondria can regulate Ca2+ mechanisms including the endoplasmic reticulum, influx pathways such as SOCE, and cell proliferation and survival. Emerging novel evidence in ASM demonstrates the existence of such roles for mitochondria (40, 48, 56, 108, 165, 192, 201, 314). For example, depletion of mitochondrial DNA (without reducing energy production) eliminates the plateau phase of the [Ca2+]i responses to bronchoconstrictor agonist in rat ASM cells, an effect involving H2O2 (40). Conversely, TGF-β can enhance mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, leading to altered ASM secretion of cytokines (201). Inflammation has been recently shown to enhance [Ca2+]i via impairment of mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering (56). In addition to ROS generated as part of mitochondrial activity, there appears to be a further role for mitochondrial networks, fission/fusion pathways, and mitochondrial mobility (6). Although there are currently no data on these mechanisms in the context of ASM [Ca2+]i or contractility, in developing ASM cells, mitochondria do respond to altered oxygen levels by becoming more fragmented (108), which could lead to reduced cellular stability and a tendency to proliferate while dismantling the SR/ER network. These data point to a potentially novel avenue for addressing increases in [Ca2+]i or even downstream effects such as ER stress and function, proliferation/migration, and cellular metabolism in the context of ASM structure and function.

Structural aspects.

Beyond [Ca2+]i and Ca2+ sensitivity, there is now interest in the idea that “remodeling” of intracellular and extracellular structures may also contribute to ASM tone. One example is the emerging role of caveolae and their regulatory caveolin and cavin proteins (7, 52, 89, 91, 105, 240, 264, 265, 272, 280). Caveolae in human ASM have been found to harbor agonist receptors, Ca2+ influx channels (TRPC isoforms, Orai1, NCX; Fig. 2), and proteins for Ca2+ sensitization (RhoA) (52, 240). Here, of the three isoforms, caveolin-1 appears to be important in that reduced caveolin-1 expression or function blunts agonist-induced ASM [Ca2+]i and contractile responses (52, 92, 240). Such effects appear to involve reduced [Ca2+]i influx, impaired SR Ca2+ release, as well as blunted Ca2+ sensitivity for force generation via RhoA (91, 240, 264). Here, proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α can enhance caveolin-1 expression and function, and conversely caveolin-1 facilitates enhancement of [Ca2+]i and contractile responses to inflammation (265). In this regard, it appears that caveolae may differentially modulate ASM responses to cytokines such as TNF-α vs. IL-13, at least in part due to caveolar vs. noncaveolar expression of their respective receptors (265). In contrast to these [Ca2+]i/contraction data, reduced caveolin-1 expression has been reported to facilitate ASM proliferation (89, 91, 93). Thus it could be reasoned that caveolin-1 contributes to the balance between contractile vs. proliferative phenotype of ASM in the context of inflammation but in either fashion enhance airway changes in asthma for example. Unfortunately, this distinction may not be as clear cut, as evidenced by a recent report that airways of caveolin-1 knockout mice are actually more responsive to methacholine challenge, a feature exacerbated with ovalbumin sensitization and challenge (7). However, airway thickness as well as markers of cell proliferation are increased in caveolin-1 KO mice, consistent with other in vitro data on cell proliferation. Although the reasons for discrepancies between in vitro [Ca2+]i/contractility and in vivo airway reactivity remain to be determined, the potential contribution of airway epithelial caveolin-1 itself should be considered (7, 103, 161, 281). Certainly, caveolin-1 is associated with endothelial NOS, and, if epithelial NO is important in regulation of airway tone, then dysfunction due to lack of caveolin-1 may be contributory. Alternatively, other epithelial mechanisms such as cyclooxygenase 2 signaling may be altered, as suggested by a recent study (281). In addition to Ca2+/contractility per se, the relevance of caveolae may further lie in the increasing recognition that ASM can modulate ECM production. Here, by virtue of their ability to interact with intracellular cytoskeletal elements, caveolae may form a nexus or tether between intracellular and extracellular structures and facilitate signaling. Overall, these data highlight the importance of plasma membrane mechanisms such as caveolae in regulation of airway structure and function, aspects that could be examined in the context of inflammation, asthma, fibrosis, and other conditions.

Structural aspects of ASM may modulate both passive airway stiffness as well as active responses to agonist stimulation (41, 279, 353). Furthermore, long-term changes in these pathways could contribute to more established structural changes within the airway. The physiological relevance of these parameters lies in the recognition that ASM is extremely “plastic” in that it rapidly adapts and regains its ability for force generation following a decline in force induced by repetitive length changes, as occurs during tidal volume breathing (26, 57). Thus, even in the setting of a range of active forces, passive stiffness can be maintained due to adaptations in the airway. Accordingly, the reduced airway lumen in asthma due to increased contractility and remodeling would cause baseline ASM length to decrease and thus influence the adaptability of ASM. Here, increases in passive stiffness could contribute to increased airway reactivity by attenuating the extent of ASM length fluctuations during tidal breathing (i.e., offer greater passive resistance to stretch and opening of the airway lumen). A recent study showed that such adaptations are enhanced at shorter lengths of ASM cells/tissue, an effect mediated by increased cross-linking of cytoskeletal filaments (but not actin polymerization or contractile actin-myosin interactions reflected by lack of effect of latrunculin B or Rho kinase inhibition) (26). Other cytoskeletal elements such as intermediate filaments or even ECM components may be involved. For example, dense bodies, one of the most prominent structures in smooth muscle cells, can serve as anchors for actin filaments (akin to Z-disks in striated muscle). Such dense bodies and intermediate filaments can form cable-like structures and adjust their cable length according to cell length and tension via connections to the ECM, thus helping to maintain passive stress (353). Furthermore, in vitro studies using dissolution of different ECM proteins suggest that elastase exerts its functional effects by reducing parenchymal tethering, whereas collagenase reduces airway wall stiffness, thus differentially influencing the load on ASM during contraction (153). On the other hand, passive load on ASM can enhance expression of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain and decrease Akt signaling via integrins (58), whereas stretching of ASM results in increased TGF-β expression (mediated via multiple signaling mechanisms) (210) and induces ASM cell hypertrophy (211, 212). Such stretch-induced hypertrophy may be mediated via miRNAs (e.g., miR-26a) (212), but Akt may also be important (183). Separately, the β-catenin signaling cascade appears to be important for stabilizing adherens junctions and thus enhancing cell-cell contacts in ASM, resulting in enhanced contractility (88, 128). Accordingly, ECM-cell or cell-cell mechanotransduction events in ASM become particularly relevant to the idea of detrimental ASM adaptations in the setting of airway diseases and point to novel avenues for targeting excessive airway contractility and remodeling. Furthermore, in the present era of organ bioengineering, understanding the mechanisms that regulate ASM mechanical properties is key to building biocompatible artificial airways (334).

Neural Control

In airway diseases such as asthma and bronchitis, airway hyperresponsiveness can be modulated by increased cholinergic outflow from the parasympathetic nervous system (34, 276, 315). Design for reflex protection of the airway via bidirectional central nervous system (CNS)-airway pathways, repeated exposures to environmental pollutants, inflammatory stimuli, and other noxious agents may modulate afferent airway sensory pathways (150, 315, 316), leading to increased excitability of airway-related vagal preganglionic neurons and airway hyperresponsiveness. The extensive and exquisite neural control of airways has been previously reviewed (150, 177, 317, 318). CNS control of the airway involves integrated networks along the central neural axis, particularly the vagal preganglionic neurons within the medulla, which form the final common pathway from the brain to the airways. Signals are transmitted to intrinsic tracheobronchial ganglia in close proximity to effector systems of the postganglionic axons, which are distributed within the airways. In addition to the cholinergic mechanisms, intrinsic airway neurons release a variety of neuromodulators, such as vasoactive intestinal peptide and nitric oxide (NO) that form the nonadrenergic, noncholinergic system that aids bronchodilation. Vagal afferent fibers of sensory ganglia are present throughout the bronchopulmonary tree and innervate sensory receptors that detect changes in chemical, mechanical, or thermal stimuli. Different sensory receptors and afferent fibers are expressed with different functions. For example, C-fiber receptors contain the neuropeptides such as substance P and neurokinin A that can induce bronchoconstriction and further cause a local, neurogenic inflammation, whereas other mechanosensitive reflex systems control breathing and parasympathetic outflow (and thus airway tone).

The relevance of the complex neural pathways lies in their enhanced contribution in airway diseases, for example in allergen-induced changes in ASM tone and mucous secretion due to increased activation of preganglionic airway parasympathetic nerves (neurogenic asthma) (34, 276, 315), and the fact that commonly used drugs such as ipratropium target cholinergic innervation in preventing excessive bronchoconstriction. However, new mechanisms by which neural control of ASM is dynamically modulated are continuing to be identified, highlighting novel pathways for pharmacological intervention. Furthermore, beyond anatomical and immunohistochemical localization of nerve pathways, their functional aspects are also being explored. For example, one study (331) found that the level of integration by ganglionic parasympathetic neurons in the airway differs between species, an important point to consider when using transgenic and other models that may have a neurogenic component. Separately, in guinea pigs, a subset of esophageal neurons that express calretinin and ACh have been found to provide excitatory input to tracheal cholinergic ganglia and thus indirectly regulate airway tone (197). Finally, the effects of inflammation (321, 332), infection (124), pollutants (252), and other stimuli on airway nerves are being explored, again with the intent of suppressing excessive bronchoconstriction, as well as cough reflexes. Here, an emerging theme is again neurotrophins such as NGF, BDNF, and glial-derived neurotrophic factor that serve to influence airway reactivity (175, 176, 200) as well as enhance immunity and reactivity in the airway following bacterial infections (38), exposure to house dust mite (and important aspect of allergic asthma) (346), allergen challenge (176), or ozone (322). Furthermore, it may be relevant to consider whether novel mechanisms such as TAS2R and OGR1 are present and functional in neural pathways involved in airway tone.

ASM in Airway Remodeling

It is now well established that there is extensive airway remodeling that occurs in diseases such as asthma (11, 22, 113, 169, 190, 285, 302, 333, 337, 348). Such remodeling is characterized by structural changes including a thickened abnormal epithelium with mucus gland hypertrophy, subepithelial membrane thickening, and fibrosis with altered ECM composition and deposition, angiogenesis, and importantly increased ASM mass (Fig. 1). Indeed, increased ASM mass may be a key feature of airway remodeling, being associated with severe asthma and decreased lung function (228) and likely contributing to enhanced airway contractility and a narrowed lumen. In this regard, the mechanisms by which increased ASM mass occurs are still under investigation, with the key question of whether ASM cell hyperplasia or hypertrophy is more contributory (11, 13–15, 66, 127). It is possible that such changes are not homogeneous in different sized airways, wherein large bronchi demonstrate hyperplasia in some cases, but not others, whereas hypertrophy is present in different parts of the airway (13, 66). Certainly, the increased deposition of ECM proteins and associated fibrosis is also likely to be contributory. Regardless, the mechanisms underlying hypertrophy have been examined to a certain extent (e.g., see Ref. 15 for review; Fig. 5). For example, as mentioned above, mechanical stretch can induce hypertrophy, potentially via miRNA, glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β, or Akt (14, 183, 212). Activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) can also induce hypertrophy via multiple pathways (356), and this pathway may be stimulated by factors such as TGF-β or endothelin (85, 199, 355). In asthmatic ASM, hypertrophy is associated with increased myosin light chain kinase (13).

Fig. 5.

Role of ASM in remodeling. Besides its role in modulating contractility, there is now substantial evidence that insults such as allergens, infection, and environmental factors can modulate the “synthetic” aspects of ASM. Here, ASM can produce a range of ECM proteins including collagen, fibronectin, the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs), as well as a number of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, growth factors (e.g., BDNF), and angiogenic factors (e.g., vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF). Furthermore, in response to insults, autocrine/paracrine effects of locally produced factors (e.g., cytokines and growth factors) and intracellular mechanisms (e.g., STIM1, Orai1, miRNAs), ASM cells can increase in size (hypertrophy) or number (hyperplasia), thus contributing to increased ASM mass noted in asthma. PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin; ET1, endothelin 1; PGs, prostaglandins.

There are now a number of studies on ASM hyperplasia and the mechanisms that regulate it in the context of airway remodeling (11, 16, 22, 113, 160, 188, 190, 259, 285, 333, 348). In general, an upregulation of proproliferative pathways or, alternatively, blunting of endogenous mechanisms to prevent proliferation as well of apoptotic pathways have been described. Furthermore, some studies have reported that ASM cells of asthmatic patients have greater proliferation at baseline (140, 314) although the underlying mechanisms are not completely understood (the role of increased mitochondria biogenesis and impaired Ca2+ reuptake have been proposed) (314). However, it should also be emphasized that the evidence for such increased ASM proliferation in asthmatics is not conclusive with some ex vivo studies (140, 314) showing proliferation but others showing little (149, 327). Nonetheless, a plethora of signaling pathways has been found to be involved in enhancing ASM proliferation, including p38 and p42/44 MAP kinases, PI3/Akt, NF-κB, and TGF-β-associated kinase-1 (5, 39, 49, 92, 229, 230). Conversely, antiproliferative mechanisms such as the transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-α have been found to be downregulated (258).

In terms of “stimuli” for enhanced ASM proliferation, several proinflammatory mediators are thought to be important (Fig. 5), including TNF-α, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 (but see Ref, 254), TGF-β, thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), and those of the Th17 family (11, 39, 152, 190, 232, 245, 246). However, there is also some suggestion that “normal” stimuli such as bronchoconstrictor agonists (114, 233, 341) and other locally produced factors (5, 53, 75) could trigger increased proliferation under certain conditions, leading to the asthmatic phenotype. In this regard, interactions between GPCRs and RTKs may be important (18, 67, 68, 155, 162, 303). For example, M2 muscarinic receptors can potentiate TGF-β-induced enhancement of proliferation (216). EGF receptor signaling (particularly that from epithelium) is thought to be a potent player in airway remodeling in models of chronic allergic asthma (171, 284) and can in turn mediate the effects of cysteinyl leukotrienes (cysLTs; LTC4, LTD 4), which are synthesized from arachidonic acid and can themselves increase ASM mass (198, 296). However, one study found that prostaglandins are more effective in inducing ASM remodeling compared with leukotrienes (319). Mechanical stress in airways can also induce EGF release from epithelial cells and thus contribute to remodeling (283). Emerging data suggest a role for the nonreceptor tyrosine kinase Abl, which appears to inhibit ERK1 phosphorylation, modulate actin dynamics, and further prevent the mitogenic effects of factors such as endothelin-1 and PDGF (138, 139), the latter well known to be mitogenic in ASM (286). Other growth factors such as VEGF (187) and even the neurotrophin BDNF (5) can enhance ASM proliferation. These latter data highlight the ability of local factors to modulate ASM and the need to target such mechanisms beyond inflammation. In addition to these factors, within ASM cells, microRNAs are also thought to play a role in orchestrating proliferative and migratory responses (45, 168), a theme better examined in pulmonary artery (95, 96, 263, 342) but an emerging topic in ASM. Finally, consistent with the idea that sex steroids could influence airway structure and function (308), it is important to consider whether estrogens could potentially influence ASM proliferation, particularly given their mitogenic role in breast cancer and other malignancies. Here, the data are not as clear cut in that estrogens may in fact be antiproliferative in the airway in some settings (308). Nonetheless, estrogen signaling in the airway be further relevant to the fascinating but rare progressive disease of young women, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) (110), which involves smooth muscle-like LAM cells within the lung. LAM may represent abnormal ASM or vascular smooth muscle, and exacerbation of this disease during pregnancy would suggest a role for sex steroids. For example, interference with estrogen signaling appears to potentiate the effects of inhibitors of mTOR in alleviating LAM (100).

Overall, the information to date points to multiple, potentially interacting mechanisms that can contribute to airway remodeling represented by ASM proliferation or migration. Although increased cell proliferation can occur in the presence of inflammation via different pathways, there are less data on what prevents or blunts ongoing proliferation from continuing indefinitely. One study suggests that ASM modifies the extracellular environment (e.g., collagen fibril density), resulting in limited proliferation (274). Furthermore, signaling mechanisms within ASM itself could be involved. For example, caveolin-1 can inhibit proliferation (7, 89, 92), whereas the SOCE mechanisms STIM1 and Orai1 can enhance TGF-β1-induced proliferation (79) (Fig. 5). Certainly, therapeutic agents such as corticosteroids and even β2-agonists can reduce proliferation (19, 86). Furthermore, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ ligands can blunt ASM proliferation, migration, and ECM formation (63, 72, 73, 250, 293), and this mechanism may be of interest, given its emerging role in lung development and injury (180, 220, 247, 260). Finally, there is increasing interest in atypical anti-inflammatory stimuli such as vitamin D (44, 50). These emerging and exciting data point to novel avenues by which airway remodeling could be curtailed if not reversed.

Overall increases in ASM cell numbers in the context of remodeling could reflect both increased cell proliferation as well as reduced apoptosis. Although it is commonly assumed that the two processes reflect opposite sides of the same coin, their regulatory mechanisms are known to be substantially different and are not just inhibition or reduction in specific pathways that result in proliferation vs. apoptosis. Here, in contrast to the substantial data on increased ASM cell proliferation, there is much less information on apoptosis per se. Some studies have reported reduced rates of ASM apoptosis following exposure to Th17-associated cytokines (39), IL-8, eotaxin, and monocyte inflammatory protein-1a (107), as well as with TRPV1 agonist (354), extracellular laminin (313), and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase-1 (GGT1) antagonism (83). However, several other studies have found that mechanisms such as phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (182), PPAR-γ (73), collagens (274), and vitamin D (50) modulate ASM cell proliferation but do not influence apoptosis. Much of the data in favor of or against apoptosis are derived from in vitro work in cultured ASM cells. Furthermore, it remains to be determined whether there are temporal patterns, dose responsiveness, and other modulatory factors that influence the extent of proliferation vs. apoptosis following inflammatory or other insults, particularly in vivo.

Regardless of whether significant apoptosis is a key element of ASM, an emerging topic in the area of airway biology is the concept of autophagy (or autophagocytosis), which is now recognized to be necessary for cellular homeostasis and assurance of cell survival during times of stress or altered cellular energy levels. Autophagy can be seen as an adaptive response to survival but could also promote cell death in the context of disease. There is presently limited information regarding how autophagy may play a role in asthma, or of the cell types involved. Because autophagy plays a major role in the immune responses to various pathogens relevant to asthma induction or exacerbation (particularly viruses), it is possible that autophagic responses in airway epithelia or smooth muscle occur in the setting of infection or alternatively contribute to worsening of inflammatory effects when infection is also present (146). Whether autophagy in ASM is important has been examined only to a limited extent. For example, pharmacological inhibition of GGT1 induces p53-dependent autophagy in human ASM cells (83). Furthermore, excessive ROS, as may occur in airway inflammation, could induce autophagy and thus contribute to asthma pathophysiology (234).

In addition to increased proliferation, given the “synthetic” aspect of ASM, there is now much interest in the concept of ASM-generated factors that can have autocrine/paracrine effects in terms of remodeling. Here, generation of ECM proteins by ASM (23, 31, 53) (in addition to the well-known role of fibroblasts) is particularly important and relevant, considering the fact that the fractional area of the matrix is increased in smooth muscle layers in fatal asthma (10). In this regard, ASM cells derived from asthmatics may produce a different profile of ECM proteins or respond differently to the inflammatory milieu. The importance of the ECM composition further lies in responsiveness of the airway to therapy (particularly resistance to corticosteroids and β2AR agonists; Refs. 27, 274) and the very question of whether airway remodeling is reversible or controlled by current therapies.

In the airway, a network of collagenous and noncollagenous ECM protein structures surrounds cells, and thus the density and composition of the ECM influence cellular behaviors such as proliferation, migration, differentiation, and survival. Particularly relevant ECM elements include collagens and fibronectin (30, 117) and members of the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family (MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-12) as well as their tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase, (TIMP)-1 and TIMP-2 (42, 151, 160, 167, 218, 294) (Fig. 5). Furthermore, signaling moieties on ECM proteins can in turn regulate epithelial, ASM, and other cells. Here, ECM can itself regulate formation and release of growth factors and MMPs (which cleave a number of extracellular proteins), thus creating a complex network that can regulate the extent of remodeling. Alterations in ECM in the asthmatic airway include enhanced deposition of collagens I, III, and V, fibronectin, tenascin, hyaluronan, versican, and perlecan but a decrease in other proteins such as collagen IV and elastin (30). Altered ECM production can be modulated by inflammatory mediators produced by surrounding cells as well as growth factors. Here, a number of signaling cascades have been identified (30, 160), and new ones are frequently reported. Conversely novel mechanisms that blunt ASM-derived ECM production are also identified. For example, IL-1β alone or in combination with TNF-α increases ASM production of MMP-12 (339), as well as MMP-9 (174), which, by degrading elastin, collagen, etc., can promote cell migration, tissue repair, and remodeling. Noncanonical Wnt5a and β-catenin regulate TGF-β effects on ASM production of ECM proteins (9, 160), whereas TGF-β alone can enhance deposition of perlecan in ASM from patients with COPD (121). Loss of caveolin-1 enhances ECM levels in chronic inflammation within the airway (7), whereas Rho kinase inhibition prevents ECM remodeling (235). Decorin, an ECM proteoglycan, can bind TGF-β and blunt ECM production within airways (191). Even infections can alter ECM production by ASM, exemplified by rhinovirus-induced increases in fibronectin and perlecan, particularly in asthmatic ASM (164). These data, by no means comprehensive, underline the complex involvement of ASM in matrix remodeling. Here, it is important to emphasize that the effects of the matrix per se on ASM structure and function form an even more complex layer that is yet to be well established.

Like many other cell types within the airway, ASM not only respond to inflammatory mediators but are themselves a source of a wide variety of pro- and anti-inflammatory factors, granting ASM an immunomodulatory function as well. Indeed, such an immunomodulatory function itself can be triggered by inflammation, infection, and microbial products (160). For example, anti-CD3-stimulated peripheral blood T cells as well as bronchoalveolar lavage-derived T-cells from challenged atopic donors can adhere to ASM, upregulating intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression and inducing ASM surface expression of MHC class II (170). The relevance of such interesting functions of ASM lies in the ability of secreted factors to have both autocrine effects on ASM responses to inflammation as well as in the recruitment of other cell types in the inflammatory response of the airway. For example, exposure of ASM cells can present bacterial superantigen to CD4+ T cells via such MHC class II to enhance production of proasthmatic cytokine such as IL-13 (320). Indeed, IL-13 is just one of the many factors produced by ASM, with the list ever increasing (160, 287). Examples include IL-1β, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-17, PDGF, and TGF-β although their autocrine/paracrine function within the airway in the context of preexisting inflammation is still being explored. For example, IL-6, a pleiotropic cytokine that can induce ASM hyperplasia and modulate immune cell function, is secreted by ASM cells when they are stimulated by other cytokines such as IL-1β or TNF-α. Furthermore, TNF-α can mediate its effects on ASM by enhancing IFN-β secretion (195) or via other receptors [including those for microbes such as Toll-like receptor 2 (189)]. Similarly, TGF-β can regulate IL-6 release from ASM cells (201). Recent data also demonstrate that ASM is a source as well as target of the early cytokine TSLP that can recruit dendritic cells and mediate a host of airway responses (244, 245, 288). The mechanisms by which regulation of cytokine release by ASM occurs are plentiful and include recognized players in inflammation such as NF-κB and AP-1, but new pathways such as Nox4, ROS (201), GSK-3β (9) are being identified. There is also emerging evidence that ASM may be a major source of chemokines such as RANTES, eotaxin, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and CXCL10 (51). The mechanisms by which such release occurs are also under investigation and include players such as MAPK, JAK/Stat, JNK, and even [Ca2+]i (3, 297). Although it is not clear whether ASM-derived chemokines serve any other function beyond the expected recruitment of inflammatory cells, it is nonetheless clear that ASM per se plays an important role in the inflamed airway. In addition to these typical inflammatory factors, there is also emerging evidence that growth factors such as VEGF and BDNF can be secreted by ASM cells (5, 160, 200, 324), which may have autocrine effects in terms of cell proliferation as well as contractility. The overall relevance of ASM-derived factors from a clinical perspective lies in the ability of therapies such as glucocorticoids in blunting the secretion of these factors and thus inflammation and its effects as a whole. Here, limited data suggest that the profile of ASM-derived factors may drive steroid insensitivity and limit the ability of this line of therapy in blunting airway inflammation.

Airway Development

Although much of the above discussion has focused on the importance of ASM in adult airways and diseases such as asthma or COPD, it is also increasingly evident that factors that detrimentally influence airway development in both the fetal and early postnatal periods can have longstanding effects through childhood and beyond (12, 65, 282). Certainly, our understanding of the processes that regulate embryonic lung development is now vastly advanced with the introduction of lineage studies, transgenic animals, and a variety of sophisticated imaging techniques. Unlike alveoli that continue to form and grow postnatally for several years, the number of airways is fixed at birth. Accordingly, disruption of airway branching, elongation, and growth in the late fetal period can have substantial postnatal effects. Added to this is the frequent complication of premature birth requiring exposure of immature airways to high levels of oxygen with or without mechanical ventilation in the neonatal intensive care unit. A well-recognized sequelae is bronchopulmonary dysplasia, represented by alveolar simplification and vascular dysmorphogenesis. However, a cardinal feature of survivors of the premature period is wheezing and asthma that extends into childhood and sometimes adulthood (194, 249, 345). Further complications may occur due to environmental exposures in the neonate such as second-hand cigarette smoke and respiratory infections. What is not well established is what role the developing ASM plays in these scenarios and what effects insults such as hyperoxia (or even hypoxia) and environmental triggers play in altering airway structure and function.

One relevant issue during fetal development is the role of mechanical stretch and the concept of airway peristalsis (134, 135) and cyclical Ca2+ waves within fetal ASM cells that can promote airway branching and elongation. Such spontaneous peristaltic Ca2+ waves and contractions appear to be coupled and arise from specific “pacemaker”-like ASM cells and intercellular communications via gap junctions (71, 136). Although the mechanisms underlying these waves are still under investigation, membrane potential, L-type Ca2+ channels, and chloride currents appear to play a role (which makes the developing ASM different from the adult). Given the reemergence of chloride pathways in ASM (see above), it may be relevant to examine this issue as well as the role of membrane potential pathways in the developing ASM in the context of potential intervention in the face of lung or airway hypoplasia as occurs with diseases such as congenital diaphragmatic hernia or diaphragm paralysis, intrauterine growth retardation, infection, etc. Regardless, these novel findings have helped identify ASM as being more than a vestigial cell type and an active player in airway development. Indeed, it would be important to imagine the immature ASM with a high proliferative rate as being akin to the synthetic, proliferative ASM of in adult asthma where intracellular Ca2+ regulatory structures are deconstructed, making the cells more dependent on influx pathways. Conversely, the concept of pacemakers and their interruption as being key to dysfunctional airway growth (136) could be leveraged toward understanding why emerging technologies such as focal bronchial thermoplasty are effective in blunting airway remodeling in asthma. Furthermore, the emerging role of stretch in modulating expression of genes and proteins in adult tissues should serve as a model to examine how mechanical forces within the developing airway induced by ASM cells could influence airway and lung growth. The relevance of stretch may conversely lie in determining how injurious mechanical forces, especially in the setting of prematurity could influence lung development (111, 112).

As with other lung regions, a number of growth factors and transcription factors are being identified as being important for ASM development per se, and their upregulation or downregulation with insults may affect overall airway development as well as postnatal responses to insults and their sequelae. However, given the complex and coordinated processes that define lung development, it is difficult to target specific, single mechanisms that may be alleviating. Nonetheless, some targets such as fibroblast growth factor 10 (94, 135, 275), the neurotrophins [particularly BDNF/TrkB; (81, 242, 291, 344, 345)], and Runt-related transcription factors (106) are being examined. Changes in airway development and growth following inflammation/injury (28, 35, 111, 112, 166), diaphragm paralysis (349), oxygen exposure (97, 108, 156), and cigarette smoke (106) are also now being characterized. Further development in this area is dependent on appropriate in vitro and in vivo models that reflect human lung development and growth, not an easy task to accomplish given differences between immature and adult ASM (108). Furthermore, from a practical perspective, it is important to consider whether and how pharmacological or other interventions targeting ASM influence other cell types in the growing lung.

What Have We Learned?