People with mental health problems still experience “some of the most deeply felt stigma” from health care professionals, according to the Mental Health Commission of Canada.

Although “often unintentional,” such discrimination remains a major barrier to quality care, treatment and recovery, the commission reveals in the Opening Minds Interim Report.

Many patients who seek help for mental health problems report feeling “patronized, punished or humiliated” in their dealings with health professionals, the report states. Discrimination can include negativity about a patient’s chance of recovery, misattribution of unrelated complaints to a patient’s mental illness and refusal to treat psychiatric symptoms in a medical setting.

Michael Pietrus, director of the commission’s Opening Minds anti-stigma initiative, cites a case in which emergency physicians initially failed to investigate a patient’s pain symptoms because he had a history of mental illness.

“Eventually, they got him into x-ray and actually found out that he had gallstones, and that’s what was causing the pain.”

Physicians can be particularly tough to reach with anti-stigma messages. According to the report, programs in hospitals or other health care settings to reduce discrimination are not well attended by doctors.

“I just don’t think that doctors have really taken the time to see if, in fact, they are contributing to stigmatization,” says Pietrus. “[They’re] pretty busy people.”

Lack of training may also contribute to physicians being unaware of how their language and actions can be harmful to patients with mental illness, he says. “It could be anything from words that are used, to glances, to overall treatment.”

However, when physicians do participate in anti-stigma programs, there is “strong overall evidence of positive change,” states the report.

In particular, programs that “emphasize social contact with people with lived experience of a mental illness, as well as programs emphasizing skills training for health care providers” have proven effective.

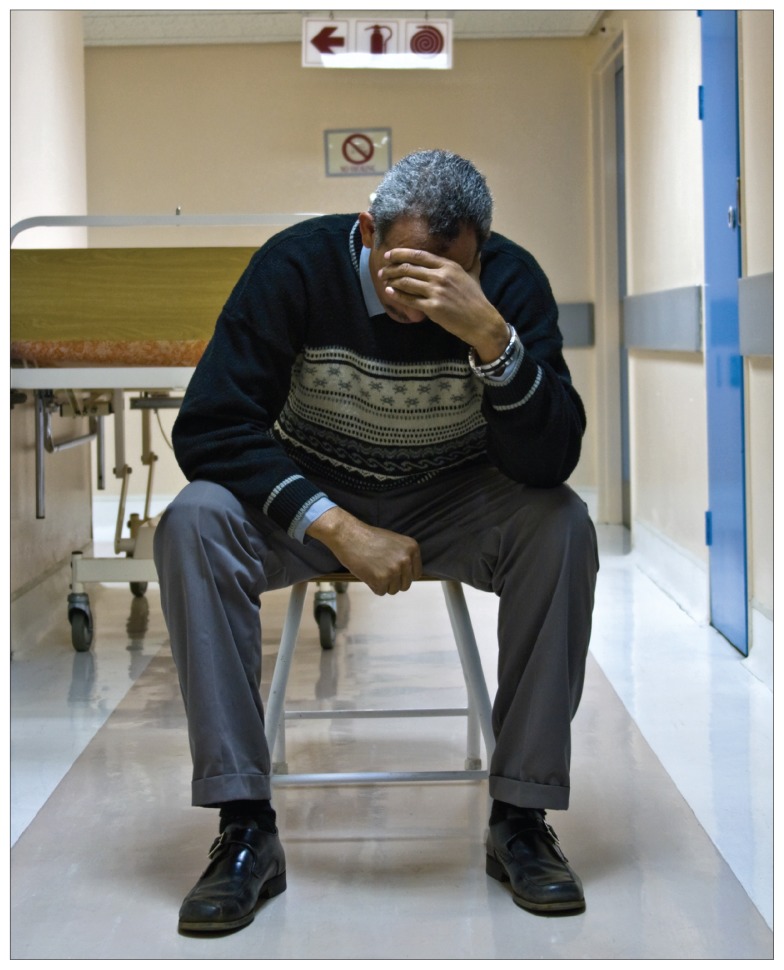

Health care settings can be stressful places for people with mental health problems, some of whom report feeling “patronized, punished or humiliated” by health care professionals.

Image courtesy of © 2014 Thinkstock

Programs may have a greater impact if they focus on a specific illness, the report states. Successful programs also tend to have “some type of incentive or expectation for participation, such as education credited, paid-for time, or position back-filling.”

Pietrus says the result of these initiatives is that doctors are more “confident” dealing with patients with mental illness, allowing them to see the person behind the diagnosis.

Sometimes the most dramatic changes come from “a simple act of kindness,” he adds. It’s “about a health care provider taking the time to talk to an individual and reassuring them that they are important and that their life has meaning.”